Abstract

Sepsis-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is a heterogeneous disease with high morbidity and mortality. Lactylation plays a crucial role in sepsis and sepsis-induced lung injury. This study aimed to identify distinct lactylation-based phenotypes in patients with sepsis-associated ARDS and determine relevant molecular biomarkers. We analyzed blood transcriptome and clinical data from patients with sepsis-associated ARDS and calculated the lactylation activity. KEGG pathway analysis, drug sensitivity prediction, and immune cell infiltration analysis were performed. Candidate molecular biomarkers were identified by intersecting the feature genes extracted from four machine learning models. Lactylation activity showed significant heterogeneity among patients with sepsis-associated ARDS, which enabled the classification into low- and high-lactylation activity phenotypes. Patients with high-lactylation experienced longer hospital stays and higher mortality rates, as well as distinct signaling pathways, drug responses, and circulating immune cell abundances. Six key markers (ALDOB, CCT5, EP300, PFKP, PPIA, and SIRT1) were identified to differentiate the two lactylation activity phenotypes, all significantly correlated with circulating immune cell populations. This study revealed significant heterogeneity in lactylation activity phenotypes among patients with sepsis-associated ARDS and identified potential biomarkers to facilitate the application of these phenotypes in clinical practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sepsis is a critical condition resulting from a systemic inflammatory response to infection and is characterized by multiorgan dysfunction and high mortality rates1,2. Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is a serious complication that occurs when inflammation leads to increased vascular permeability and impaired gas exchange in the lungs3,4. A large prospective cohort study showed that sepsis was the underlying cause of ARDS in approximately 75% of patients5. The mortality rate among patients with sepsis-associated ARDS is notably higher than that associated with other causes of ARDS, reaching approximately 30–40%5,6. ARDS and sepsis have long been considered highly heterogeneous, with many clinical, physiological, and biological phenotypes. The failure of clinical trials of pharmacological treatments is partly due to such heterogeneity7,8,9,10. Two molecular phenotypes of ARDS (hyperinflammation and hypoinflammation) have been proposed, each associated with distinct clinical outcomes and varying responses to specific therapies10,11. Although recent advances have been made, there remains a significant need to identify novel homogeneous molecular phenotypes and biomarkers that can enhance disease stratification and improve diagnostics and personalized treatment approaches for patients with sepsis-associated ARDS.

Lactate, traditionally viewed as a metabolic by-product, is now recognized as a key player in the inflammatory response and a predictive biomarker for sepsis12. Numerous studies have demonstrated that elevated serum lactate levels serve as biomarkers for sepsis, with higher lactate levels correlating with higher mortality rates13,14. Another function of lactate known as lysine lactylation has also been identified15. Lactylation is a posttranslational modification similar to acetylation that occurs when lactate attaches to lysine residues on proteins, catalyzed by two types of enzymes (lactylase and delactylase), thereby regulating gene transcription, metabolism, and inflammation, and participating in various pathological and physiological processes, including cancer development, macrophage polarization, and Alzheimer’s disease16,17,18,19,20. Recent studies have explored the role of lactylation in sepsis and sepsis-induced lung injury21,22,23. Li et al.21 identified specific lactylation-related genes, such as S100A11 and CCNA2, that are strongly associated with sepsis and could serve as valuable diagnostic and prognostic markers. All the evidence indicates that lactylation serves as a promising novel biomarker for stratifying sepsis-associated ARDS and guiding potential therapeutic interventions.

Despite growing interest in lactylation, few studies have investigated the specific patterns of lactylation that distinguish between different clinical phenotypes in sepsis-associated ARDS. Therefore, we hypothesize that lactylation-based phenotypes could offer a novel approach to understanding the heterogeneity of sepsis-associated ARDS. In the present study, we categorized patients with sepsis-associated ARDS into low- and high-lactylation activity phenotypes and identified associated molecular biomarkers. Our findings enhance the understanding of the distinct biological mechanisms underlying these lactylation-based phenotypes and contribute to the development of personalized therapeutic strategies for managing sepsis-associated ARDS.

Materials and methods

Data collection and preprocessing

First, whole blood samples from 31 patients with sepsis-associated ARDS were selected from the GSE32707 dataset24 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE32707). We further analyzed the transcriptome data of blood specimens obtained from patients with sepsis-associated ARDS on the day of admission (day 0; n = 18) and 7 days later (day 7; n = 13). The patient information is presented in Supplementary Table S1. Raw microarray data were was preprocessed using the robust multiarray Average (RMA) method implemented in the R package Affy (version 1.44)25 using the default parameters, including quantile normalizion and log2 transformation. The arrays were normalized separately and the same gene corresponded to probe intensity was combined afterwards to obtain gene expression data matrix in each sample. In addition, 332 lactylation-related genes were obtained from the literature (Supplementary Table S2)22,26.

Lactylation activity estimation

Single-sample gene set variation analysis (ssGSVA) is a statistical method used to assess the enrichment of predefined gene sets in individual samples, rather than in a whole dataset. Based on the expression profiles of lactylation-related genes, ssGSVA within gene set variation analysis (GSVA) package in the R was used enrichment analysis. Subsequently, we estimated the lactylation activity score for each sample, providing a quantitative measure of lactylation levels.

Clustering analysis

The subtypes were determined by the k-means clustering algorithm and the NbClust in the R package factoextra (version 1.0.5). The k-means clustering was utilized to cluster samples according to their lactylation activity, while Nbclust analysis was conducted to identify the most stable number of clusters. Based on the average silhouette width obtained from the clustering results, two clusters were determined to be optimal. The samples were classified into low- and high-lactylation activity groups. To identify the normative cut-off values, the single minimum value of the higher cluster is chosen to be the best estimate27. Principal component analysis (PCA) was utilized to assess the reliability of the groupings and to facilitate visualization by selecting the two primary dimensions.

Differential expression analysis

Differentially expressed genes between the low- and high-lactate activity groups were selected according to the criteria of |log2 fold change (FC)| > 1 and adjusted p ≤ 0.05. The analysis was performed using the limma package28, which is a widely used tool in R for identifying differentially expressed genes in microarray and RNA-seq studies.

Gene set variation analysis

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) gene sets were obtained from the Molecular Signature Database29. The GSVA package in R30 was employed to score the activities of these KEGG pathways for each sample, transforming gene expression data into a format that facilitates the assessment of pathway activity at the individual sample level. Pathway analysis was conducted using the KEGG database31,32,33, following the citation guidelines provided at http://www.kegg.jp/kegg/kegg1.html.

Drug sensitivity prediction

For drug sensitivity prediction, we used expression profiling and drug sensitivity data sourced from the Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer database34. Clinical drug responses in patients with sepsis-associated ARDS were predicted using the OncoPredict package35, an R tool that estimates drug sensitivity based on gene expression profiles and a reference database of cancer cell line responses.

Immune infiltration analysis

The abundance levels of 22 immune cell populations were estimated using the CIBERSORT package36. CIBERSORT employs a deconvolution algorithm that utilizes gene expression data to infer the proportions of various immune cell types within a mixed cell population. In addition to estimating immune cell abundances, the relationships between distinct immune cell types were also calculated. Furthermore, differences in the abundance of immune cell populations between the groups were analyzed. Correlation analysis was also conducted on the expression of specific genes and abundance levels of immune cell populations.

Machine learning

Genes with high expression correlations were identified and eliminated using the findCorrelation function in the Caret package. This streamlined the gene set and retained only the most informative genes for analysis, thereby enhancing the performance and interpretability of subsequent machine learning models. Subsequently, the recursive feature elimination (rfe) function was employed to determine the genes that contributed most significantly to the grouping. The samples were then divided into training and test sets in a ratio of 7:3 using the CreateDataPartition function. For model training, four classification algorithms–Logit Boost, Random Forest, Support Vector Machine (SVM), and Naïve Bayes–were selected to predict the function and generate classification results37. The pROC package was used for receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis38.

Identification of candidate biomarkers

Feature genes were extracted from the four classification models and intersected. The obtained genes were regarded as candidate biomarkers for classification. ROC analysis was performed to evaluate the performance of the candidate biomarkers in classification prediction.

Statistical analysis

All the analyses were conducted using R Studio (version 4.0.2; http://www.R-project.org) and GraphPad Prism (version 9.0.9; GraphPad Software Inc.). For normally distributed data, results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and analyzed using the independent samples t-test. Non-normally distributed data were expressed as median (interquartile range, IQR) and analyzed with the Mann–Whitney test. Categorical variables were analyzed using the chi-square or Fisher’s exact test and expressed as numbers and percentages. Correlation analysis was performed using Pearson or Spearman correlation tests. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Landscape of lactylation activity across blood samples from patients with sepsis-associated ARDS

The present study gathered transcriptome data from blood samples of 31 patients with sepsis-associated ARDS. After data normalization (Supplementary Fig. S1A, B), we calculated the lactylation activity score for each sample based on the expression of lactylation-related genes. The results showed that lactylation activity was notably heterogeneous among the sepsis-associated ARDS blood samples (Fig. 1A). By assessing the average silhouette width from our clustering analysis, we found that 2 was the optimal and stable number of clusters (Supplementary Fig. S2). Using an optimal cutoff value of 0.8757, we classified all samples into low (n = 13) and high (n = 18) lactylation activity phenotypes (Supplementary Table S3). PCA demonstrated transcriptional differences between the two phenotypes (Fig. 1B). Differential expression analysis was conducted to determine transcriptional heterogeneity between the two phenotypes. As a result, 1449 up- and 368 down-regulated genes (|log2FC| > 1 and adjusted p ≤ 0.05) were determined in high- versus low-lactylation activity phenotypes (Fig. 1C–E), which might be related to lactylation modification in the progression of sepsis-associated ARDS.

Landscape of lactylation activity across blood samples from patients with sepsis-associated ARDS. (A) Heatmap of lactylation activity in blood samples from patients with sepsis-associated ARDS on the day of admission (day 0) (n = 18) and 7 days later (day 7) (n = 13). The lactylation activity score gradually increases from blue to red. (B) PCA demonstrating transcriptional differences in the low- and high-lactylation activity phenotypes. (C, D) Volcano plot displaying the up- and down-regulated genes (|log2FC| > 1 and adjusted p ≤ 0.05) in high- versus low-lactylation activity phenotypes. (E) Heatmap displaying the top 20 up- and down-regulated genes in the two phenotypes.

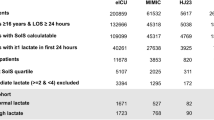

Clinical features and outcomes of high- versus low- lactylation activity phenotypes in sepsis-associated ARDS

As shown in Table 1, no significant differences were found in gender, age and race between the two lactylation subtypes. Although the average age was slightly higher in the high-lactylation group (57.2 ± 15.1) compared to the low-lactylation group (48.6 ± 10.3), this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.074). The patient cohort was predominantly White (87.1%), which suggested a relatively homogeneous ethnic background. We found that patients with high lactylation activity had significantly longer hospital stays (36.0 days, IQR 11.0-49.5) compared to those with low-lactylation activity (11.0 days, IQR 8.0–20.0; p = 0.028). The high-lactylation group also had a significantly higher APACHE II score (42.6 ± 14.1) compared to the low-lactylation group (31.0 ± 10.0; p = 0.017), further indicating a poorer prognosis for those with higher lactylation activity. Moreover, the high-lactylation group exhibited a significantly higher 28-day mortality rate (55.6% vs. 15.4%; p = 0.032) and an increased one-year mortality rate (66.7% vs. 23.1%; p = 0.029) compared to the low-lactylation group. Although the in-hospital mortality rate was higher in the high-lactylation group, this difference did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.129). Collectively, these findings suggest that lactylation activity phenotypes are probably associated with critical illness severity and patient outcomes in sepsis-associated ARDS and have the potential to identify patients at higher risk of poor prognoses.

Heterogeneous signaling pathways and drug responses between the two lactylation activity phenotypes

In our KEGG pathway analysis, we identified significant differences in activity between the high- and low-lactylation activity phenotypes in patients with sepsis-associated ARDS. Notably, the TGF-β signaling pathway, primary bile acid biosynthesis, cocaine addiction, arginine biosynthesis, steroid hormone biosynthesis, Hippo signaling pathway, complement and coagulation cascades, synthesis and degradation of ketone bodies, and arginine and proline metabolism were significantly more active in the high-lactylation activity phenotype. Conversely, pathways associated with neurodegeneration-multiple diseases, the GnRH signaling pathway, central carbon metabolism in cancer, valine, leucine, and isoleucine biosynthesis, 2-oxocarboxylic acid metabolism, thiamine metabolism, protein export, protein processing in the endoplasmic reticulum, autophagy other, mitophagy animal, thyroid cancer, and glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchor biosynthesis exhibited significantly higher activity in the low-lactylation activity phenotype (Fig. 2A, B). These findings suggested that distinct molecular signatures and potential therapeutic targets are associated with lactylation in sepsis-associated ARDS.

Heterogeneous signaling pathways and drug responses between the two lactylation activity phenotypes. (A) Bar graph showing the differential GSVA scores in KEGG pathways between the low- and high-lactylation activity phenotypes. (B) Heatmap of the GSVA score in KEGG pathways with p ≤ 0.1 and |t| ≥ 2 across blood samples. (C) Box plot showing the differential IC50 values of drugs between the two phenotypes. The KEGG images were constructed as per the citation guidelines: www.kegg.jp/kegg/kegg1.html.

We observed that the low-lactylation activity phenotype displayed a lower half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) for AZD6482, rapamycin, sorafenib, MG-132, OSI-027, ruxolitinib, bortezomib, GSK1904529A, lapatinib, and dasatinib. Conversely, the high-lactylation activity phenotype displayed a lower IC50 for MK-2206, vinblastine, docetaxel, RO-3306, AZD8055, KU-55,933, vinorelbine, vorinostat, camptothecin, cytarabine, gemcitabine, navitoclax, axitinib, temozolomide, cisplatin, olaparib, gefitinib, AZD7762, XAV939, and 5-fluorouracil (Fig. 2C). These results indicate heterogeneity in drug responses between the two lactylation activity phenotypes.

Heterogeneous circulating immune cells between the two lactylation activity phenotypes

The abundance of immune cell populations was examined in each sepsis-associated ARDS blood sample (Fig. 3A). Circulating immune cell populations exhibited intricate interactions in sepsis-associated ARDS (Fig. 3B). Among the circulating immune cell populations, M1 macrophages and T follicular helper cells were more abundant in the low-lactylation activity phenotype, whereas naïve CD4+ T cells were more abundant in the high-lactylation activity phenotype (Fig. 3C, D), reflecting the heterogeneity in the circulating immune cell populations between the two lactylation activity phenotypes.

Heterogeneous circulating immune cells between the two lactylation activity phenotypes. (A) Stacked bar chart showing the relative abundance of immune cell populations across blood samples from patients with sepsis-associated ARDS. (B) Heatmap showing the relationships between the immune cell populations. (C, D) Heatmap and box plot showing the differential abundance of immune cell populations between the two lactylation activity phenotypes.

Establishment of classification models for differentiating the two lactylation activity phenotypes

Next, we established four classification models to better differentiate the two lactylation activity phenotypes. The feature genes were selected using the four machine learning models (Fig. 4A, C, E, G), and they were presented in Table 2. ROC analysis confirmed the high discriminatory accuracy of the LogitBoost, NaïveBayes, RandomForest, and SVM classification models in distinguishing between the two lactylation activity phenotypes, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 1.000, 0.944, 1.000, and 1.000 in the training set; 0.833, 0.944, 0.861, and 1.000 in the test set; and 0.923, 0.944, 0.934, and 1.000 in the total set, respectively (Fig. 4B, D, F, H). By intersecting the feature genes identified from the four classification models, six candidate molecular biomarkers were identified: aldolase B (ALDOB), chaperonin containing TCP1 subunit 5 (CCT5), E1A binding protein P300 (EP300), phosphofructokinase-1 platelet type (PFKP), peptidylprolyl isomerase A (PPIA), and sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) (Fig. 4I).

Establishment of classification models for differentiating the two lactylation activity phenotypes. (A–H) Feature gene selection using four classification algorithms: (A) LogitBoost, (C) NaïveBayes, (E) RandomForest, and (G) SVM, and ROC analysis to evaluate the performance of the (B) LogitBoost, (D) NaïveBayes, (F) RandomForest, and (H) SVM models in differentiating the two lactylation activity phenotypes in the training, test, and total sets. (I) Venn diagram displaying the intersection of the feature genes (ALDOB, CCT5, EP300, PFKP, PPIA, and SIRT1) extracted from the four classification models.

Identification of candidate biomarkers enabling differentiation of the two lactylation activity phenotypes

The six candidate molecular biomarkers, ALDOB, CCT5, EP300, PFKP, PPIA, and SIRT1, showed notably higher expression in the high- versus low-lactylation activity phenotypes (Fig. 5A). In addition, ROC analysis demonstrated that they enabled the accurate differentiation of the two lactylation activity phenotypes, with AUC values of 0.863, 0.906, 0.872, 0.915, 0.940, and 0.923, respectively (Fig. 5B).

Candidate biomarkers enabling differentiation of the two lactylation activity phenotypes. (A) Box plot showing the differential expression of the candidate biomarkers, ALDOB, CCT5, EP300, PFKP, PPIA, and SIRT1 in the two lactylation activity phenotypes. (B) ROC analysis to evaluate the performance of the candidate biomarkers in differentiating the two lactylation activity phenotypes.

Correlations between the candidate biomarkers and Circulating immune cells

Further analysis demonstrated that the expression of ALDOB, CCT5, EP300, PFKP, PPIA, and SIRT1 was strongly associated with the abundance of circulating immune cells in patients with sepsis-associated ARDS (Fig. 6A–F). In particular, all biomarkers showed negative relationships with M1 macrophages and T follicular helper cells and exhibited positive relationships with naïve CD4+ T cells. These findings indicate the potential roles of these six biomarkers in the modulation of systemic inflammatory responses in sepsis-associated ARDS.

Correlation analysis between candidate biomarkers and circulating immune cells in sepsis-associated ARDS blood samples. (A–F) Lollipop chart visualizing the correlations between the expression of (A) ALDOB, (B) CCT5, (C) EP300, (D) PFKP, (E) PPIA, and (F) SIRT1 and the abundance of immune cell populations.

Discussion

The present study categorized sepsis-associated ARDS into two phenotypes, low- and high-lactylation, each characterized by distinct transcriptional patterns, signaling pathways, drug sensitivity, and immune infiltration. Additionally, using machine learning algorithms, six molecular biomarkers (ALDOB, CCT5, EP300, PFKP, PPIA, and SIRT1) were identified to differentiate between the two lactylation-based phenotypes. These findings provide insights into targeted therapeutic strategies and improve patient stratification for the management of sepsis-associated ARDS.

Sepsis-associated ARDS is a highly heterogeneous syndrome, which contributes to the challenges faced in clinical trials of pharmacological treatment7,8,9,10. Recognizing the distinct phenotypes in heterogeneous patients is crucial for the clinical management of sepsis-associated ARDS. Lactylation has emerged as a significant factor in sepsis and its associated lung injury21,22,23, making it a potential biomarker for distinguishing between different clinical phenotypes of ARDS. Lactate regulates gene transcription via lactylation, influencing N6-methyladenosine levels by enhancing p300-mediated H3K18ac binding to the METTL3 promoter, thereby affecting ACSL4 and promoting ferroptosis, a cell death mechanism linked to sepsis-induced lung injury23. In the present study, we calculated the lactylation activity scores based on the transcriptomic profiles of lactylation-related genes and classified the samples into low- and high-lactylation activity phenotypes using a cutoff value of 0.8757. As indicated in Table 1, patients in the high-lactylation group experienced worse clinical outcomes, including longer hospital stays and higher mortality rates. In addition, we observed significant heterogeneity in signaling pathway enrichment and drug responses between these phenotypes in patients with sepsis-associated ARDS. This heterogeneity suggests that lactylation provides valuable insights into understanding both patient variability and the underlying mechanisms of sepsis-associated ARDS. Overall, our findings suggest that lactylation serves as a promising biomarker for distinguishing ARDS phenotypes and is probably associated with patient outcomes. It may reflect disease severity and assist in guiding treatment strategies, thereby paving the way for more personalized interventions based on individual lactylation activity profiles.

Next, we investigated the landscape of immune cell infiltration across different lactylation phenotypes in the context of sepsis-associated ARDS. Lactate, the end product of anaerobic glycolysis, is produced in high amounts by innate immune cells during inflammatory activation and acts as a metabolic mediator influencing the fate and function of immune cells. In the present study, we observed that M1 macrophages and T follicular helper cells were predominant in the low-lactylation phenotype, whereas naïve CD4+ T cells were more prevalent in the high-lactylation phenotype. This heterogeneity likely reflects the diverse metabolic states and functional capacities of immune cells in response to lactate levels. Immune cells, particularly macrophages and T cells, play crucial roles in lactate production and subsequent lactylation39,40. Macrophage-derived lactate has been shown to influence various lactylation processes, including HMGB1 lactylation and histone lactylation during sepsis15,22. Conversely, lactylation regulates immune cell phenotypes and functions through epigenetic mechanisms, such as influencing gene expression patterns. For example, M1 macrophages exhibit elevated histone lactylation during the late phase of polarization in sepsis15,39. Collectively, these findings indicate that the relationship between immune cells and lactylation phenotypes is complex and likely bidirectional. Immune cell activation enhances lactate production and lactylation levels, while lactylation influences immune cell phenotypes and functions. This bidirectional relationship highlights the potential for therapeutic strategies targeting both immune cell dynamics and metabolic pathways. Treatments such as dexmedetomidine, curcumin, IL-35, and HMGB1 inhibition have shown promise in promoting the differentiation of naïve CD4+ T cells into regulatory T cells, thereby reducing ARDS severity41,42,43,44. Future research should explore the intricate mechanisms underlying this relationship to develop more effective therapeutic strategies for sepsis-associated ARDS.

To overcome the limitations of transcriptome sequencing and bioinformatics analysis in clinical settings, we employed four classification algorithms (LogitBoost, RandomForest, SVM, and NaiveBayes) to identify ALDOB, CCT5, EP300, PFKP, PPIA, and SIRT1 as key biomarkers distinguishing two lactylation activity phenotypes. These biomarkers are significantly associated with circulating immune cells in patients with sepsis-associated ARDS. ALDOB, a glycolytic enzyme, plays a crucial role in regulating lactylation in cancers45,46. CCT5 is involved in cancer progression and resistance47 and serves as a biomarker for liver metastasis in lung cancer48. EP300, a histone acetyltransferase and a critical lactyltransferase, catalyzes lactylation and is found to be elevated in ARDS, correlating with IL-17 levels and survival outcomes49,50. PFKP lactylation in colon cancer cells directly reduces enzyme activity, creating a negative feedback loop with lactate production51. SIRT1, a deacetylase, facilitates the deacetylation of HMGB1, thereby mitigating acute kidney injury associated with sepsis52. The identification of these biomarkers paves the way for developing targeted therapies and diagnostic tools. Modulating their expression or activity could potentially control inflammatory responses and enhance patient outcomes in sepsis-associated ARDS. Furthermore, these biomarkers could serve as indicators of treatment efficacy and disease progression, supporting personalized medicine approaches.

The hypoinflammatory and hyperinflammatory subphenotypes of ARDS, as defined by Calfee et al.8. , have been validated across multiple trial cohorts11,53,54. However, the relationship between lactylation-based and inflammation-based subphenotypes in ARDS remains unclear. Inflammatory responses, particularly in hyperinflammatory states, can enhance lactate production, leading to increased lactylation36,37. Hyperlactylation may indicate elevated circulating lactate levels, probably associated with hyperinflammatory states. Immune cells, especially macrophages, exhibit distinct lactylation patterns that influence their polarization (M1 vs. M2) and function15,36,37. Lactylation can modulate inflammatory responses by altering the activity of key proteins, such as histones and transcription factors, affecting pro-inflammatory cytokine expression15,21,22,36. These findings directly link lactylation to inflammatory subtypes. Further investigation is needed to explore the interplay between lactylation and inflammation in patients with sepsis-associated ARDS.

Although our study provides valuable insights into the role of lactylation phenotypes in sepsis-associated ARDS, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the small sample size limits the applicability of our findings and may lead to overfitting in the analysis. This increases the risk of over-interpreting clinical outcomes, such as mortality rates and hospital stays, in high-lactylation phenotypes. Therefore, validation in larger cohorts is essential to support these findings. Second, variability in gene expression across different cohorts challenges the generalizability of our model, requiring external validation and more accessible testing methodologies. Third, the measurement of the six molecular biomarkers identified is not yet feasible at the bedside, impeding rapid clinical decision-making. Additional research is needed to translate these findings into actionable clinical tools. Furthermore, this study did not capture essential clinical information, including key prognostic indicators (PaO2/FiO2 ratio, organ failure, and ventilation-free days) and predictive factors (responses to PEEP, fluid, and statins)55, limiting a comprehensive understanding of lactylation subphenotypes and their prognostic implications. Finally, we could not obtain additional plasma samples to measure key biomarkers such as IL-6, IL-8 and soluble TNF receptor-155,56, restricting our ability to explore the interactions between lactylation and inflammatory subtypes. Future prospective studies measuring these biomarkers are essential to elucidate the overlap between lactylation and inflammation in ARDS subphenotypes.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our transcriptomic analysis revealed notable heterogeneity in the lactylation activity among patients with sepsis-associated ARDS. Six molecular biomarkers (ALDOB, CCT5, EP300, PFKP, PPIA, and SIRT1) were identified with potential implications for the translation of lactylation activity phenotypes into clinical practice for patients with sepsis-associated ARDS. These findings can enhance patient stratification, unveil new therapeutic targets, and provide more effective treatments in this challenging clinical landscape.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed in this study are available in the GEO database (GSE32707, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE32707), MsigDB (http://www.gseamsigdb.org/gsea/index.jsp) and Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer database (https://www.cancerrxgene.org/).

References

Singer, M. et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). Jama 315, 801–810. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.0287 (2016).

Chiu, C. & Legrand, M. Epidemiology of sepsis and septic shock. Curr. Opin. Anaesthesiol. 34, 71–76. https://doi.org/10.1097/aco.0000000000000958 (2021).

Qadir, N. et al. An update on management of adult patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome: an official American thoracic society clinical practice guideline. Am. J. Respir. Crit Care Med. 209, 24–36. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.202311-2011ST (2024).

Bos, L. D. J. & Ware, L. B. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: causes, pathophy- siology, and phenotypes. Lancet (Lond. Engl.) 400(22), 1145–1156. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736 (2022).

Bellani, G. et al. Epidemiology, patterns of care, and mortality for patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome in intensive care units in 50 countries. Jama 315, 788–800. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.0291 (2016).

Stapleton, R. D. et al. Causes and timing of death in patients with ARDS. Chest 128, 525–532. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.128.2.525 (2005).

Sinha, P., Meyer, N. J. & Calfee, C. S. Biological phenotyping in sepsis and acute respiratory distress syndrome. Annu. Rev. Med. 74, 457–471. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-med-043021-014005 (2023).

Calfee, C. S. et al. Subphenotypes in acute respiratory distress syndrome: latent class analysis of data from two randomised controlled trials. Lancet Respir. Med. 2, 611–620. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70097-9 (2014).

Cao, S. et al. Identification of genetic profile and biomarkers involved in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Intensive Care Med. 50, 46–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-023-07248-9 (2024).

Sinha, P. et al. Identifying molecular phenotypes in sepsis: an analysis of two prospective observational cohorts and secondary analysis of two randomised controlled trials. Lancet Respir. Med. 11, 965–974. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2213-2600(23)00237-0 (2023).

Famous, K. R. et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome subphenotypes respond differently to randomized fluid management strategy. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 195, 331–338. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201603-0645OC (2017).

Nolt, B. et al. Lactate and immunosuppression in sepsis. Shock (Augusta Ga). 49, 120–125. https://doi.org/10.1097/shk.0000000000000958 (2018).

Mikkelsen, M. E. et al. Serum lactate is associated with mortality in severe sepsis independent of organ failure and shock. Crit. Care Med. 37, 1670–1677. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e31819fcf68 (2009).

Liu, Z. et al. Prognostic accuracy of the serum lactate level, the SOFA score and the qSOFA score for mortality among adults with sepsis. Scand. J. Trauma Resusc. Emerg. Med. 27, 236. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13049-019-0609-3 (2019).

Zhang, D. et al. Metabolic regulation of gene expression by histone lactylation. Nature 574, 575–580. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1678-1 (2019).

Xin, Q. et al. Lactylation: a passing fad or the future of posttranslational modification. Inflammation 45, 1419–1429. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10753-022-01637-w (2022).

Wang, J. et al. Lactylation of PKM2 suppresses inflammatory metabolic adaptation in Pro-inflammatory macrophages. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 18, 6210–6225. https://doi.org/10.7150/ijbs.75434 (2022).

Wang, T. et al. Lactate-induced protein lactylation: a Bridge between epigenetics and metabolic reprogramming in cancer. Cell Prolif. 56, e13478. https://doi.org/10.1111/cpr.13478 (2023).

An, S. et al. PDHA1 hyperacetylation-mediated lactate overproduction promotes sepsis-induced acute kidney injury via Fis1 lactylation. Cell Death Dis. 14, 123. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-023-05952-4 (2023).

Wei, L. et al. H3K18 lactylation of senescent microglia potentiates brain aging and Alzheimer’s disease through the NFκB signaling pathway. J. Neuroinflamm. 20, 639. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12974-023-02879-7 (2023).

Li, S. et al. Exploring the prognostic and diagnostic value of lactylation-related genes in sepsis. Sci. Rep. 14, 23130. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74040-0 (2024).

Yang, K. et al. Lactate promotes macrophage HMGB1 lactylation, acetylation, and Exosomal release in polymicrobial sepsis. Cell Death Differ. 29, 133–146. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41418-021-00841-9 (2022).

Wu, D., Spencer, C. B., Ortoga, L., Zhang, H. & Miao, C. Histone lactylation-regulated METTL3 promotes ferroptosis via m6A-modification on ACSL4 in sepsis-associated lung injury. Redox Biol. 74, 103194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2024.103194 (2024).

Dolinay, T. et al. Inflammasome-regulated cytokines are critical mediators of acute lung injury. Am. J. Respir. Crit Care Med. 185, 1225–1234. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201201-0003OC (2012).

Gautier, L., Cope, L., Bolstad, B. M. & Irizarry, R. A. Affy–analysis of affymetrix genechip data at the probe level. Bioinf. (Oxf. Engl.) 20, 307–315. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btg405 (2004).

Cheng, Z. et al. Lactylation-Related gene signature effectively predicts prognosis and treatment responsiveness in hepatocellular carcinoma. Pharmaceut. (Basel Switzerl) 16, 236. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph16050644 (2023).

Kaufman, L. & Rousseeuw, P. J. Finding Groups in Data: An Introduction to Cluster Analysis. https://doi.org/10.2307/2532178 (Wiley, 2009).

Ritchie, M. E. et al. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, e47. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkv007 (2015).

Liberzon, A. et al. The molecular signatures database (MSigDB) hallmark gene set collection. Cell. Syst. 1, 417–425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cels.2015.12.004 (2015).

Hänzelmann, S., Castelo, R. & Guinney, J. GSVA: gene set variation analysis for microarray and RNA-seq data. BMC Bioinform. 14, 523. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-14-7 (2013).

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Matsuura, Y. & Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG: biological systems database as a model of the real world. Nucleic Acids Res. 53, D672–d677. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkae909 (2025).

Kanehisa, M. Toward Understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Protein Sci.: Publ. Protein Soc. 28, 1947–1951. https://doi.org/10.1002/pro.3715 (2019).

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 27–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/28.1.27 (2000).

Yang, W. et al. Genomics of drug sensitivity in cancer (GDSC): a resource for therapeutic biomarker discovery in cancer cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D955–D961. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gks1111 (2013).

Maeser, D., Gruener, R. F. & Huang, R. S. OncoPredict: an R package for predicting in vivo or cancer patient drug response and biomarkers from cell line screening data. Brief. Bioinform. 22, 236. https://doi.org/10.1093/bib/bbab260 (2021).

Chen, B., Khodadoust, M. S., Liu, C. L., Newman, A. M. & Alizadeh, A. A. Profiling tumor infiltrating immune cells with CIBERSORT. Methods Mol. Biol. (Clifton N J) 1711, 243–259. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-7493-1_12 (2018).

Deist, T. M. et al. Machine learning algorithms for outcome prediction in (chemo)radiotherapy: an empirical comparison of classifiers. Med. Phys. 45, 3449–3459. https://doi.org/10.1002/mp.12967 (2018).

Robin, X. et al. pROC: an open-source package for R and S + to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC Bioinform. 12, 77. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-12-77 (2011).

Wei, Y., Guo, H., Chen, S. & Tang, X. X. Regulation of macrophage activation by lactylation in lung disease. Front. Immunol. 15, 427739. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2024.1427739 (2024).

Xu, B., Liu, Y., Li, N. & Geng, Q. Lactate and lactylation in macrophage metabolic reprogramming: current progress and outstanding issues. Front. Immunol. 15, 1395786. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2024.1395786 (2024).

Zhang, Z. T. et al. Dexmedetomidine alleviates acute lung injury by promoting Tregs differentiation via activation of AMPK/SIRT1 pathway. Inflammopharmacology 31, 423–438. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10787-022-01117-5 (2023).

Chai, Y. S. et al. Curcumin regulates the differentiation of Naïve CD4 + T cells and activates IL-10 immune modulation against acute lung injury in mice. Biomed. Pharmacother. 125, 109946. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2020.109946 (2020).

Wang, C., Xie, K., Li, K., Lin, S. & Xu, F. Potential therapeutic effects of interleukin-35 on the differentiation of Naïve T cells into Helios(+)Foxp3(+) Tregs in clinical and experimental acute respiratory distress syndrome. Mol. Immunol. 132, 236–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molimm.2021.01.009 (2021).

Xie, K. et al. HMGB1 suppress the expression of IL-35 by regulating Naïve CD4 + T cell differentiation and aggravating Caspase-11-dependent pyroptosis in acute lung injury. Int. Immunopharmacol. 91, 107295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2020.107295 (2021).

Liu, C. et al. Identification of a glycolysis- and lactate-related gene signature for predicting prognosis, immune microenvironment, and drug candidates in colon adenocarcinoma. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 10, 145. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2022.971992 (2022).

Aldolase, B. & lactagenesis CEACAM6 activation promote cell renewal and chemoresistance in colorectal cancer through the Warburg effect. Cell Death Dis. 14, 412. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-023-06187-z (2023).

Li, Y. et al. CCT5 induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition to promote gastric cancer lymph node metastasis by activating the Wnt/β-catenin signalling pathway. Br. J. Cancer 126, 1684–1694. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-022-01747-0 (2022).

Li, S. et al. Comparative proteomic profiling of plasma exosomes in lung cancer cases of liver and brain metastasis. Cell. Bioscie. 13, 639. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13578-023-01112-5 (2023).

Huang, H. et al. Lactate enhances NMNAT1 lactylation to sustain nuclear NAD(+) salvage pathway and promote survival of pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells under glucose-deprived conditions. Cancer Lett. 588, 216806. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2024.216806 (2024).

Chen, Y., Huang, B., Zhao, Y., Qi, D. & Wang, D. Increased p300/CBP expression in acute respiratory distress syndrome is associated with interleukin-17 and prognosis. Clin. Respir. J. 14, 791–799. https://doi.org/10.1111/crj.13197 (2020).

Cheng, Z., Huang, H., Li, M. & Chen, Y. Proteomic analysis identifies PFKP lactylation in SW480 colon cancer cells. iScience 27, 108645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2023.108645 (2024).

Wei, S. et al. SIRT1-mediated HMGB1 deacetylation suppresses sepsis-associated acute kidney injury. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 316, F20–F31. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajprenal.00119.2018 (2019).

Sinha, P. et al. Prevalence of phenotypes of acute respiratory distress syndrome in critically ill patients with COVID-19: a prospective observational study. Lancet Respir. Med. 8, 1209–1218. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30366-0 (2020).

Dahmer, M. K. et al. Pediatric acute lung injury and sepsis investigators (PALISI) network. Identification of phenotypes in paediatric patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome: a latent class analysis. Lancet Respir. Med. 10, 289–297. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00382-9 (2022).

Wilson, J. G. & Calfee, C. S. ARDS subphenotypes: understanding a heterogeneous syndrome. Critical care. Critical care (Lond. Engl.) 24, 102. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-020-2778-x (2020).

Spadaro, S. et al. Biomarkers for acute respiratory distress syndrome and prospects for personalised medicine. J. Inflamm. (Lond.) 16, 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12950-018-0202-y (2019).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Professor Tamás Dolinay for his invaluable guidance and kindly assistance with the clinical data for our study. We would also like to thank Editage (www.editage.cn) for English language editing.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province, China (2024JJ5354; 2023JJ40585), Scientific and Technology Research Projects of Health Commission of Hunan Province (W20243167), and Scientific Research Project of Hunan Provincial Education (21C0300).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.W.: Writing–original draft, Supervision, Visualization, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization, Writing–review and editing. A.W.: Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation. Z.S.: Visualization, Methodology, Software. Y.S.: Visualization, Software, Data Curation. X.L: Data Curation. L.H.: Writing–original draft, Supervision, Visualization, Methodology, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Writing–review and editing. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Wei, A., Su, Z. et al. Characterization of lactylation-based phenotypes and molecular biomarkers in sepsis-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome. Sci Rep 15, 13831 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96969-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96969-6

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Genetic Evidence Linking Lactylation-Related Gene Expression To Dementia Risk

NeuroMolecular Medicine (2025)