Abstract

The study focuses on the VRAC channel and its significant roles in cancer development. It addresses a research gap by conducting a pan-cancer analysis with multi-omics bioinformatics tools, integrating data from the Human Protein Atlas (HPA) and Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) datasets to examine mRNA expression patterns of its Leucine Rich Repeat Containing 8 (LRRC8) subunits in various tissues and cancers. The study links variations in LRRC8s expression with patient outcomes and includes analyses of DNA and RNA methylation. The study reveals significant correlations between LRRC8s expression and immune cell infiltration, as well as a positive association with cancer-associated fibroblasts and key immune regulators such as major histocompatibility complex (MHCs) and chemokines. Furthermore, the research suggests that LRRC8s are involved in cancer-signalling pathways, which may offer new therapeutic targets. Additionally, a drug sensitivity analysis shows that LRRC8 subunits affect drug responses differently, supporting the use of personalized therapeutic strategies. In conclusion, the study emphasizes the significance of VRAC subunits in cancer biology and suggests their potential as biomarkers and targets in cancer immunotherapy and personalized medicine.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cancer remains a leading cause of death globally, characterized by its rapid evolution and complexity, involving significant genetic and epigenetic changes1,2,3. These alterations lead to varied phenotypic and molecular manifestations of the disease, complicating its pathogenesis through complex interactions among multiple signalling pathways and genes. The increasing incidence of cancer is attributed to longer lifespans and changing risk factors, despite advances in various therapeutic approaches including surgery, chemoradiotherapy, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy. Unfortunately, the effectiveness of these treatments is often undermined by drug resistance and adverse reactions, underscoring the urgent need for novel pan-cancer biomarkers and therapeutic targets to improve patient outcomes4,5.

The use of bioinformatics and extensive public cancer datasets presents a viable approach for investigating the mechanisms behind oncogene activation and tumor suppressor gene dysregulation across various cancers6,7,8,9,10. These techniques hold promise for identifying broad-based therapeutic targets.

In recent decades, ion channels have gained recognition as critical membrane proteins that are variably expressed across different cancer types11,12. Their aberrant expression or dysfunction is linked to increased tumor aggressiveness and a spectrum of malignant behaviors, including enhanced proliferation, migration, invasion, and metastasis, which ultimately result in poor patient prognoses13,14,15,16,17,18. Ion channels play pivotal roles in numerous cellular functions, including osmolarity regulation, membrane potential stabilization, cellular motility via cytoskeletal interactions, invasion facilitation, signal transduction, transcription modulation, and cell cycle control19. Furthermore, they regulate critical tumor microenvironment factors such as pH, oxygen levels and nutrient availability, which are crucial for cancer progression16,20,21,22,23,24,25.

Chloride (Cl-) is the most abundant extracellular anion and is vital for numerous physiological functions, including cell proliferation, migration, apoptosis, and maintaining cell volume and electrolyte balance26,27. Among the key channels involved in these processes is the volume-regulated anion channel (VRAC), which has recently been linked to cancer-related activities. VRAC was first identified in human lymphocytes in the 1980s, where it was activated by cell swelling or reduced ionic strength, leading to chloride efflux28. Since then, it has been detected in nearly all vertebrate cell types, including epithelial cells, with its defining features being broad anion permeability and the generation of outwardly rectifying currents29,30,31.

Several studies utilizing pharmacological VRAC blockers have revealed its involvement in the cell cycle. Specifically, inhibiting VRAC activity in various cancers, such as ovarian32, small-cell lung33, cervical34, esophageal35 are arrested in the G0/G1 phase, suggesting that VRAC is necessary to pass the G1/S transition phase. However, the lack of a clear molecular identity for VRAC initially limited deeper explorations of its physiological and pathological roles. This changed in 2014 with breakthrough research that identified the genes responsible for VRAC through genome-wide RNA silencing and high-throughput fluorescence assays36,37. Deletion of LRRC8A in both HEK293 and HCT116 cells significantly reduced swelling-activated VRAC chloride currents, while reintroduction of LRRC8A into LRRC8A−/−cells restored these currents36,37. In contrast, deletion of other LRRC8 subunits (B-E) did not diminish the VRAC chloride current as profoundly as LRRC8A deletion36,37 also observed strong suppression of VRAC chloride currents after LRRC8A knockdown in HEK293, HeLa cells, and CD4+T lymphocytes, findings that Okada and colleagues later confirmed in C127 cells38. Similarly, LRRC8A silencing via siRNA in cortical rat astrocytes reduced VRAC-mediated release of taurine and excitatory amino acids (glutamate and aspartate) under hypotonic conditions39 Collectively, these results underscore the indispensable role of LRRC8A in VRAC function. Intriguingly, LRRC8A overexpression did not enhance VRAC conductance but instead decreased the swelling-activated chloride current, likely due to an imbalance in subunit stoichiometry that disrupts proper channel function36,37.The other LRRC8 subunits (B-E) modulate specific properties of VRAC, such as ion selectivity and conductance40. For example, in HEK293 cells, overexpression of LRRC8B was shown to reduce ER-mediated Ca2+release, while LRRC8B-knockout cells displayed slower depletion of calcium stores in the ER41. It is suggested that, in the absence of LRRC8A, LRRC8B homomers may form leaky Cl-channels in the ER, which could indirectly influence Ca2+homeostasis. However, when co-expressed with LRRC8A, LRRC8B localizes to the plasma membrane, alongside at least one other LRRC8 paralog, to form functional VRAC channels41. In heteromeric complexes with LRRC8A and LRRC8E, LRRC8C functions as a widely expressed transporter for 2′3′-cyclic-GMP-AMP (cGAMP)42. cGAMP, an immunotransmitter, is released by diseased cells and absorbed by host cells to trigger the STING immune response43. Additionally, LRRC8C forms a complex with LRRC8A to interact with NADPH oxidase 1 (Nox1), regulating superoxide production and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα) activation, thereby amplifying inflammatory responses44. These findings suggest that LRRC8C-containing VRAC plays a crucial role in modulating various immune processes. VRAC complexes containing LRRC8D inhibit the transport of cGAMP42. However, LRRC8D is essential for the uptake of the antibiotic blasticidin S, and its presence alongside LRRC8A facilitates 50% of the absorption of the anti-cancer drug cisplatin45. This underscores the importance of LRRC8D-containing VRAC in mediating the bidirectional transport of therapeutic compounds. While VRAC is primarily associated with anion efflux, VRAC channels that include LRRC8D are also permeable to neutral and positively charged molecules such as myo-inositol, taurine, GABA, and lysine46. In the kidneys, LRRC8D is mainly expressed in the proximal tubule, and its constitutive deletion leads to proximal tubular damage, increased diuresis, and symptoms resembling Fanconi syndrome47. This suggests that LRRC8D, in combination with LRRC8A, forms channels responsible for the transport of various metabolites, with LRRC8D disruption leading to the buildup of inflammatory molecules. Finally, as previously noted, LRRC8E forms heteromeric complexes with LRRC8A and LRRC8C to transport cGAMP, thereby triggering immune responses42. Additionally, when LRRC8A/E heteromers are exposed to oxidative agents like chloramine-T or tert-butyl hydroperoxide, their activity increases more than tenfold, whereas LRRC8A/C and LRRC8A/D heteromers are inhibited by reactive oxygen species (ROS). This suggests that VRAC complexes containing LRRC8E play a role in mediating ROS-induced pathologies48. Notably, VRAC channels incorporating LRRC8E exhibit higher permeability to negatively charged molecules such as aspartate46.

This modular structure allows VRAC to adapt to varying physiological conditions and cellular environments, contributing to its involvement in cancer cell behavior. Extensive research has highlighted the significance of these genes as potential biomarkers and therapeutic targets in cancer treatment. Since the discovery of LRRC8A as a key component of the volume-regulated anion channel (VRAC), numerous studies have shown that inhibiting VRAC activity—especially by downregulating or suppressing LRRC8A—significantly influences cancer progression by regulating processes commonly involved in tumor development. In pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PAAD), the most aggressive form of gastrointestinal cancer, downregulation or inhibition of LRRC8A via DCPIB (4-(2-Butyl-6,7-dichloro-2-cyclopentyl-indan-1-on-5-yl) oxobutyric acid), a specific VRAC blocker, has been shown to suppress the proliferation, migration, and invasion of PAAD cells49. Similarly, in glioblastoma cell lines, treatment with DCPIB inhibits proliferation and migration by blocking the PI3K/AKT (Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Protein Kinase B) signaling pathway50. In patients with gastric hepatocarcinoma (HHC), significantly elevated LRRC8A expression compared to non-tumorous gastric tissue is linked to poorer prognosis, indicating that higher LRRC8A levels may promote tumor aggressiveness51. The authors of this study demonstrated that overexpression of LRRC8A enhances cell proliferation and migration in vitro, while its inhibition reduces tumor size and metastasis in vivo. In gastric cancer (GC), LRRC8A modulates cancer cell growth by regulating p53-associated signaling pathways. Specifically, downregulation of LRRC8A lowers intracellular chloride levels in GC cells, suppressing proliferation and upregulating p53, which promotes cell cycle arrest and apoptosis52.

Another critical process tied to VRAC function is apoptosis. VRAC plays a role in regulating cell volume during apoptotic shrinkage, known as apoptotic volume decrease (AVD), an early hallmark of apoptosis53. Inhibiting VRAC can disrupt apoptosis by preventing the efflux of ions such as chloride and potassium, which are necessary for cell shrinkage. VRAC is also involved in the transport of chemotherapeutic drugs like cisplatin and carboplatin. This transport depends on the essential LRRC8A subunit and is enhanced by the accessory LRRC8D subunit, which alters the channel’s selectivity and permeability to these drugs45. Numerous studies have shown that inhibiting or downregulating VRAC is associated with the development of multidrug resistance, both in vitro in human ovarian and colon cancer cell lines50,54, and in vivo in Lrrc8d−/+ mice and patients with Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma (HNSCC), where lower expression of LRRC8A/D subunits has been observed55.

Despite these findings, a comprehensive understanding of VRAC’s biological functions and its precise role in cancer progression remains limited, highlighting the need for further research into the LRRC8 family. Our study focuses on exploring the distinct contributions of LRRC8A-E subunits to cancer biology, particularly their roles in cancer progression, immune responses, and treatment resistance. By understanding the unique functions of each subunit, we aim to uncover their prognostic potential and inform the development of targeted cancer therapies.

To address these knowledge gaps, our research utilizes advanced bioinformatics resources to analyze VRAC subunit expression, regulation, and interaction patterns across different cancers. We assess their diagnostic and prognostic potential, genetic anomalies, methylation profiles, immune interactions, and functional dynamics. Our findings underscore the critical role of VRAC genes in oncology, offering potential pathways for developing new diagnostic markers and therapeutic strategies.

Materials and methods

Study design and search strategy and meta-analysis

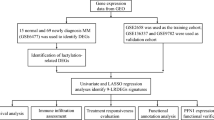

A systematic search of PubMed was conducted to review the literature on VRAC (Volume Regulated Anion Channel) expression and its correlation with cancer prognosis (Fig. 1a). Two methods were employed: PubMed searches using Biopython and web scraping using BeautifulSoup. The search utilized two sets of keywords: The search terms included “Volume Regulated Anion Channel,” “VRAC,” “LRRC8A,” “LRRC8B,” “LRRC8C,” “LRRC8D,” “LRRC8E,” and “SWELL1,” as well as “cancer,” “carcinoma,” “neoplasm,” “prognosis,” “outcome,” “survival,” and “tumor.” The search period spanned from 1 January 2010 to 20 February 2024. Studies were selected according to the following criteria: (i) relevance to human cancers, (ii) studies evaluating the association between VRAC expression and either cancer predisposition or pathological features and (iii) studies investigating the association of VRAC with mutations, metastasis, and overall cancer progression. The following criteria were excluded from the analysis: (i) redundant publications, ongoing trials, correspondence, case reports, conference abstracts, editorials, and literature reviews, (ii) studies with insufficient data for in-depth analysis, (iii) studies that focused primarily on the molecular characteristics or functions of VRAC, (iv) publications not written in English (Fig. 1a).

The RNA-seq data concernin the genes LRRC8A, LRRC8B, LRRC8C, LRRC8D, and LRRC8E were retrieved from the TCGA database using the PythonMeta Python package (Deng H., PythonMeta, Available at: https://pypi.org/project/PythonMeta/. Accessed on 22 April 2024). Gene expression profiles for these genes were extracted for individual patients. A meta-analysis was then conducted to compare the risk ratios between patient groups who survived and those who did not, focusing on variations in gene expression levels (both upregulation and downregulation). This analysis further included stratification by gender and survival outcomes.

Gene expression analysis of LRRC8s in pan-cancer

Analysis of LRRC8 mRNA expression was conducted across 33 different cancer types and normal tissues using the Tumor Immune Estimation Resource (TIMER2.0) database (http://timer.cistrome.org/, accessed on Feb. 15, 2024)56,57,58. Wilcoxon test is used to calculate statistical significance in TIMER2.0 database (*: p-value < 0.05; **: p-value < 0.01; ***: p-value < 0.001). For cancer types that are not matched to normal tissues in the TIMER2.0 database, we assessed the differential expression of LRRC8 genes using the Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis (GEPIA2) database (http://gepia2.cancer-pku.cn, accessed on Feb. 15, 2024)59 based on The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx). The abbreviations of tumors are shown in Table 1. For GEPIA2 analysis it has been used ANOVA test to calculate the p-value. For normalization of the gene expression data, TPM (Transcripts per million) method was used. Additionally, in GEPIA2, we explored the genes whose expression was significantly linked to survival in the pathological stage-specific pattern. Furthermore, we conducted protein expression analysis of LRRC8s in six cancer tissues using the Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis Consortium (CPTAC) dataset, which was accessed from the University of Alabama at Birmingham Cancer (UALCAN) database (http://ualcan.path.uab.edu/analysis-prot.html, accessed on Feb. 15, 2024)60,61. Welch’s T-test is applied to calculate the differences in expression levels between normal and primary tumors by UALCAN.

Immunohistochemical staining

The study examined immunohistochemical images of tumors using the Human Protein Atlas (HPA) database (https://www.proteinatlas.org/, accessed 15 February 2024)62,63, which is a comprehensive resource that integrates proteomic, transcriptomic, and systems biology data for mapping tissues, cells, and organs. We evaluated differences in LRRC8s protein expression levels.

Prognostic analysis of LRRC8s

Survival data for cancer patients with differentially expressed LRRC8s were obtained using the Survival Genie database (https://bbisr.shinyapps.winship.emory.edu/SurvivalGenie/, accessed 15 February 2024)64. Survival Genie is a web-based tool that facilitates survival analyses on single-cell RNA-seq data and other molecular inputs, such as gene sets and gene ratios. Survival Genie provides a comprehensive survival assessment by utilizing 53 datasets that represent 27 distinct malignancies from 11 different cancer programs, covering both adult and pediatric cancers. The tool furnishes comprehensive findings, including box plots that depict low and high-risk cohorts, as well as Kaplan–Meier plots that employ a univariate Cox proportional hazards model. Survival Genie’s source code is implemented in R, with an interactive web application built on the R Shiny framework.

In addition, we used the GEPIA2 database (http://gepia2.cancer-pku.cn, accessed on Feb. 15, 2024)59 to analyze the association between LRRC8 protein expression and pathological stage in cancers that correlate with poor or good survival.

Relationship between LRRC8s and clinicopathologic features

In this study, to achieve a comprehensive and accurate analysis of the relationship between LRRC8 subunits and clinicopathological features, we employed a combination of methods, including statistical analyses (ROC analysis, ANOVA test and Mann–Kendall trend test ), gene analysis platforms (https://guolab.wchscu.cn/GSCA/#/), and visualization techniques (ROC curve graph, Bubble plots, Heatmaps). This multi-faceted approach enabled us to more effectively investigate the clinical and pathological associations and assess the diagnostic potential of these genes.

TGCAplot R package (version 7.0.1) (github.com/tjhwangxiong/TCGAplot/blob/main/vignettes/TCGAplot.Rmd).

Tumours from the TCGA database with a sufficient number of normal samples were selected for Area Under the Curve (AUC) analysis, grouped by the expression levels of LRRC8 subunits. The pROC R package (v1.18.5) was used to assess the diagnostic potential of LRRC8 subunits in differentiating tumours from normal samples. The ROC curve was plotted, and the AUC along with the 95% confidence interval was reported.

We also employed the Gene Set Cancer Analysis (GSCA) platform to evaluate gene expression and cancer stage data across a range of cancer types (https://guolab.wchscu.cn/GSCA/#/). mRNA expression data were integrated with clinical stage information for each sample, linked via sample barcodes. To ensure the robustness of the statistical analysis, stage subgroups were composed of a minimum of five samples. The clinical stages were categorized as Stage I, Stage II, Stage III, and Stage IV based on both clinical and pathological data. In the case of testicular germ cell tumors (TGCT), the IGCCCG (International Germ Cell Cancer Collaborative Group) classification was employed, with samples divided into three prognostic groups: good, intermediate, and poor.

Gene expression data, including mRNA levels, were normalized using log2-transformed RSEM (RNA-Seq by Expectation Maximization) values to ensure comparability across samples. To statistically analyze the expression differences between cancer stages, the Wilcoxon test was employed for comparisons between two stages, while ANOVA was used for comparisons across more than two stages. To analyze the trends in gene expression across stages, the Mann–Kendall trend test was employed. Given the limited number of stages (n = 4), the P-value of the trend test served as a reference indicator, with values around 0.09 indicating the presence of a potential trend in gene expression across stages.

Bubble plots were employed for the visualization of data, with the size and color of bubbles indicating the significance of findings in accordance with the False Discovery Rate (FDR). Bubbles of a larger and darker color corresponded to more significant results. Heatmaps were generated to display log2 RSEM expression levels across the different cancer stages, and trend plots were used to illustrate gene expression changes from Stage I to Stage IV. In the trend plots, color-coded lines were used to indicate the direction of the trends, with blue lines representing a decrease and red lines representing an increase.

Gene mutation analysis of LRRC8s

The cBioPortal for Cancer Genomics (https://www.cbioportal.org, accessed 17 February 2024) provides a web platform for exploring, visualizing, and analyzing multidimensional cancer genomics data65. We performed the pan-cancer mutation frequency analysis of LRRC8s using this database by Wilcoxon rank-sum test. The mutation alterations included mutation, amplification, and deep deletion.

Promoter methylation analysis of LRRC8s

Using UALCAN portal we evaluated the epigenetic regulation of promoter methylation of LRRC8s in normal and primary tumor tissues (http://ualcan.path.uab.edu/analysis-prot.html, accessed on Feb. 18, 2024)60,61. The methylation data were normalized using beta-value transformation to ensure comparability across samples. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05 using Welch’s T-test.

DNA and RNA methylation analysis of LRRC8s

We searched the UALCAN database (http://ualcan.path.uab.edu/, accessed on 25 February 2024) to explore LRRC8s promoter DNA methylation levels in certain cancers to determine the differences between tumors and normal tissues. Shiny Methylation Analysis Resource Tool (SMART, http://www.bioinfo-zs.com/smartapp/, accessed on 27 February 2024) was applied to discuss the distribution of methylation probes in chromosomes32. MethSurv (https://Biit.cs.ut.ee/MethSurv/, accessed on 27 February 2024) is an online server for analyzing DNA methylation mode survival66. DNA methylation data are normalized using beta-value and M-value transformations to ensure comparability across samples.

RNA methylation plays a crucial role as an epigenetic regulatory mechanism and contributes significantly to tumor initiation, progression, and prognosis34. RNA methylation includes 6-methyladenosine(m6A), 5-methylcytidine(m5C), and 1-methyladenosine(m1A). We explored the correlation between VRAC subunits and regulatory proteins using RMBase v3.0 (https://rna.sysu.edu.cn/rmbase3/, accessed on 20 March 2024)67. For RNA methylation, data normalization uses TPM (Transcripts Per Million) to adjust for sequencing depth variability, with log2 transformation applied to mitigate outliers and ensure a more normal data distribution.

Immune infiltration analysis of LRRC8s

Various algorithms, such as EPIC, CIBERSORT, CIBERSORT-ABS, MCPCOUNTER, QUANTISEQ, TIMER and XCELL were applied to analyze the relationship between LRRC8s expression and immune infiltration levels across all TCGA cancers, using TIMER2.0 tool (http://timer.cistrome.org/, accessed on 25 February 2024)56,57,58. And we also investigated the correlations between LRRC8s expression and immunodulators, major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules, chemokines, and chemokine receptors in pan-cancer from the Tumor-Immune System Interactions And Drug Bank (TISIDB) database (http://cis.hku.hk/TISIDB/index.php , accessed on 27 February 2024)68. For the association analysis, partial Spearman’s correlation is employed. Notably, in methods such as EPIC and quanTIseq, which report cell fractions in relation to total cells, there is an inherent negative correlation between tumor purity and immune infiltration. As a result, no adjustment for tumor purity is required when using EPIC and quanTIseq estimations in the analysis.

Single-cell functional analysis of LRRC8s

Cancer Single-Cell States Atlas (CancerSEA) was used to investigate the single-cell functional analysis of LRRC8s69 by ANOVA test. CancerSEA (http://biocc.hrbmu.edu.cn/CancerSEA/, accessed on 25 February 2024) is the first dedicated database that aims to comprehensively decode distinct functional states of cancer cells at single-cell resolution70. It provides a cancer single-cell functional state atlas, involving 14 functional states of 41,900 cancer single cells from 25 cancer types. The association analysis is performed via the partial Spearman’s correlation by TIMER2.0. The single-cell data from CancerSEA were normalized using UMI counts or TPM (Transcripts Per Million) values to ensure comparability across different cells. The data were then log2-transformed with an offset of 1 to reduce the impact of extreme values and better normalize the distribution. Additionally, quality control measures were applied, where non-malignant cells and cells with low-quality expression (fewer than 1000 genes expressed or low housekeeping gene expression) were removed to enhance the accuracy of the analysis.

Drug sensitivity analysis

Gene Set Cancer Analysis (GSCA, http://bioinfo.life.hust.edu.cn/GSCA/#/, accessed on 28 February 2024) is an integrated platform for genomic, pharmacogenomic, and immunogenomic gene set cancer analysis. Gene Set Cancer Analysis (GSCA, http://bioinfo.life.hust.edu.cn/GSCA/#/, accessed on 28 February 2024) is an integrated platform for genomic, pharmacogenomic, and immunogenomic gene set cancer analysis69,71.The mRNA expression data were normalized using RSEM (RNA-Seq by Expectation Maximization) to ensure accurate quantification across different cell lines and genes. Drug sensitivity data (IC50 values) for both the Cancer Therapeutics Response Portal (CTRP) and the Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer (GDSC) were standardized using Z-score normalization to allow for consistent comparisons between different drugs and cell lines. Additionally, log2 transformation was applied to further normalize the data. Pearson correlation analysis was then performed to assess the correlation between gene mRNA expression and drug IC50, with P-values adjusted using FDR correction to account for multiple comparisons.

Protein–protein interaction (PPI) analysis and functional enrichment analysis of LRRC8s

Biological General Repository for Interaction Datasets (BioGRID) was used to investigate potential protein interactions involving LRRC8s72. The “Network” feature of BioGRID (available at https://thebiogrid.org/) was used to construct an LRRC8s-protein interaction network. The network was organized using the “Concentric Circles” layout configuration, with layers arranged in circles. Layers closer to the center have higher connectivity.

Using GEPIA2.059, we collected the top 100 genes that are correlated with LRRC8s across all TCGA cancer and normal tissues. We then conducted pairwise gene–gene Pearson correlation analysis between LRRC8s and the identified genes. A heatmap was used to display the expression profiles of the selected genes, including partial correlation coefficients and corresponding p-values. ShinyGO 0.80 (http://bioinformatics.sdstate.edu/go/) was used to enrich Gene Ontology (GO) molecular functions73.

Results

Figure 1 outlines our research methodology, which combines meta-analysis with integrative bioinformatics analysis to examine the impact of gene expression on patient outcomes.

In meta-analysis approach, to further examine the overall impact of VRAC expression on cancer survival, we performed a meta-analysis based on current reports with clinical information. Unfortunately, we could not find a logical connection in terms of the five interested genes (LRRC8A-E) expression and survival rate of patients with cancer between the 39 articles we found, because the methods of the study were different. Therefore, we decided to perform a meta-analysis based on the TCGA database to estimate the relationship between the five genes of interest (LRRC8A-E) expression and overall survival (OS) in cancer. We classified patients into two groups based on their gene expression levels—those with increased expression and those with decreased expression. This classification aimed to assess whether gene expression correlated with life expectancy and could serve as a biomarker for disease progression or regression. By evaluating these changes, we hoped to uncover the underlying biological mechanisms that influence disease progression and identify potential therapeutic targets. Increased gene expression may indicate increased disease aggressiveness and thus have a prognostic role, whereas decreased expression may indicate effective disease management or treatment response. In the meta-analysis, the expression of the studied genes in various cancers (Table 1) is different and has a distinct relationship with the patient’s survival, in the overall cancers study we could only find that the expression of the LRRC8D gene can be of great importance (as indicated by the 95% confidence) Supplementary Table 1.

To deepen our understanding, we performed an integrative bioinformatics analysis, examining different bio-datasets to integrate data at multiple levels, including mRNA, protein expression and patient clinical data. This comprehensive approach allows us to cross-validate the findings of the meta-analysis and uncover broader insights that may be obscured when data sources are examined in isolation.

Overall, this combined methodology not only sheds light on gene expression as a diagnostic and prognostic tool, but also highlights the importance of study design and size in producing reliable, actionable data in clinical research. These findings are critical to advancing personalized medicine and improving patient outcomes.

VRAC subunits expression in human organs/tissues and pan-cancer

The mRNA and protein expression patterns of LRRC8s were investigated across various organs and tissues. Analysis of a consolidated dataset derived from the integration of Human Protein Atlas (HPA) and GTEx transcriptomics datasets revealed distinct mRNA expression profiles for LRRC8A, LRRC8B, LRRC8C, LRRC8D, and LRRC8E. LRRC8A mRNA was predominantly expressed in the esophagus, cerebral cortex, and cerebellum, while LRRC8B mRNA was primarily detected in the cerebral cortex, testis, and adrenal gland. The mRNA expression of LRRC8C was prominent in smooth muscle, adipose tissue, and lymph nodes, while LRRC8D was mainly expressed in the spinal cord, thymus, and adrenal gland. LRRC8E, on the other hand, showed high expression levels in the skin, salivary gland, and pancreas (Fig. S1a–e).

The HPA dataset indicated that LRRC8B protein was mainly expressed in the cerebellum, cerebral cortex, and hippocampus, while LRRC8C protein was primarily expressed in the cerebellum, thyroid gland, and parathyroid (Fig. S2a,b).

However, the dataset did not provide information on protein expression levels for LRRC8A, LRRC8D, and LRRC8E. To understand the role of VRAC components genes in cancer, we examined the expression levels of LRRC8 genes for all 33 tumor types in the TCGA database. The overall expression levels of five members of the LRRC8 gene family are shown in Fig. 2a. We used TIMER2.0 to conduct a comprehensive analysis of LRRC8s gene levels to explore potential differences in VRAC subunit expression between cancerous and normal tissues (Fig. 2a). To validate the variance in LRRC8s expression between tumors and their corresponding normal tissues, we merged the GTEx and TCGA datasets due to the unavailability of certain normal tissues in TCGA (Fig. 2b). Additionally, we assessed LRRC8s expression at the protein level using the CPTAC from UALCAN tool (Fig. 3a). The expression patterns of LRRC8s show distinct trends across various cancer types. LRRC8A was found to be heightened in CHOL, COAD, ESCA, HNSC, KIRC, LIHC, LUSC, STAD, and THCA compared to their corresponding control groups. Conversely, reduced LRRC8A expression was observed in BLCA, BRCA, KICH, KIRP, LUAD, PRAD, and UCEC (Fig. 2a). Further analysis using the GEPIA-GTEx dataset revealed distinct expression patterns in DLBC, LGG, THYM, and UCS tumor tissues (Fig. 2b). On the other hand, LRRC8B displayed significantly higher expression in 12 cancers, including BLCA, CESC, CHOL, COAD, ESCA, HNSC, HNSC-HPV+, LUAD, LUSC, PRAD, STAD, and UCEC, while lower expression was observed in GBM, KICH, KIRC, KIRP, PCPG, SKCM, and THCA. No significant changes were noted in BRCA, LIHC, PRAD, and READ (Fig. 2a). The GTEx dataset revealed differential expression patterns in TGCT (Fig. 2b). Moreover, LRRC8C exhibited increased expression in CHOL, ESCA, HNSC, KIRC, and STAD, while downregulation was observed in BLCA, BRCA, COAD, GBM, KICH, KIRP, LUAD, LUSC, PAAD, PRAD, READ, and UCEC. No significant changes were found in CESC, HNSC-HPV+/−, LIHC, and THCA (Fig. 2a). Distinctive expression patterns were discovered in LAML, TGCT, and UCS upon further examination using the GTEx dataset (Fig. 2b). Additionally, LRRC8D levels were upregulated in BLCA, CESC, CHOL, ESCA, HNSC, LIHC, LUAD, LUSC, and SKCM metastasis, but downregulated in COAD, KICH, KIRC, KIRP, PAAD, PCPG, and THCA. No significant changes were found in BRCA, GBM, HNSC-HPV+/−, and READ (Fig. 2a). Distinctive expression patterns were discovered in DLBC, LGG, OV, and THYM. Lastly, LRRC8E showed upregulation in several cancers, including BLCA, BRCA, CESC, CHOL, COAD, ESCA, GBM, HNSC, KIRP, LIHC, LUAD, LUSC, PRAD, READ, STAD, and THCA, while lower levels were observed in KICH, KIRC, and PCPG. PAAD did not show significant changes. In HNSC-HPV, SKCM tumors showed increased LRRC8E expression level compared to SKCM metastases (Fig. 2a). GTEx analyses indicated heightened expression levels in OV and UCS, while a significantly level was observed in acute LAML (Fig. 2b).

Illustration of the expression patterns of LRRC8s across various cancer types. (a) TIMER2.0 analysis shows LRRC8s expression levels in TCGA cancers compared to normal tissues, with significance denoted as ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05. (b) GEPIA2.0 analysis showcases LRRC8s expression in tumor versus normal tissues.

UALCAN and HPA analyses reveal upregulated expression of LRRC8B and LRRC8C in tumor tissues. (a) UALCAN analysis results provide insights into LRRC8s expression. (b) LRRC8B expression is upregulated in numerous tumor tissues, including colon and liver. Similarly, LRRC8C showed increased expression in colon samples compared to normal samples, a finding supported by HPA. IHC results are provided by the HPA dataset.

Finally, we investigated the protein expression levels of LRRC8s in different types of cancer by using the National Cancer Institute’s CPTAC dataset and the immunohistochemistry (IHC) results available from the HPA dataset. Protein levels of LRRC8A, LRRC8C, LRRC8D, and LRRC8E were significantly elevated in head and neck cancer tissues, as shown in Fig. 3a LRRC8A, LRRC8D, and LRRC8E were overexpressed in UCEC cancer, while clear cell RCC and PAAD showed a notable rise in LRRC8A and LRRC8C levels. LRRC8A was also overexpressed in colon and liver cancer, and LRRC8D levels were heightened in OV tissues. The analysis showed a downregulation of LRRC8A, LRRC8C, and LRRC8D proteins in lung cancer and glioblastoma. Additionally, colon and UCEC cancer exhibited reduced LRRC8C expression, and clear cell RCC showed decreased LRRC8D levels. The UALCAN database does not provide protein expression data for LRRC8B.

The IHC representations of healthy and tumor specimens retrieved from the HPA database were analyzed. The findings confirmed a significant increase in LRRC8B protein levels in individuals with colon and liver malignancies compared to normal tissue (Fig. 3b). The HPA analysis also established a significant overexpression of LRRC8C protein in colon cancer. However, data for LRRC8A, LRRC8D, and LRRC8E subunits are currently lacking to support our investigation.

Examination of the VRAC components revealed a remarkable diversity in the expression levels of different genes within the same tumor, as well as variations in the expression of the same gene in different tumors. This highlights the need to comprehensively study each gene as a cohesive unit.

VRAC subunits expression on patients’ prognosis

Using the recent SurvivalGenie database64 and Kaplan–Meier analysis, we classified samples into high and low LRRC8s expression groups based on quartile LRRC8 mRNA levels. As detailed in a previous study74,75, a significant correlation was found between LRRC8A expression levels and patient prognosis across six different cancer types. Elevated LRRC8A levels were associated with poorer prognosis in COAD, HNSC and PAAD. Conversely, cases of KIRC, LGG and SARC showed favorable outcomes. Our analysis revealed significant prognostic implications for LRRC8B in various cancers, including ACC, COAD, and MESO. Elevated levels of LRRC8B in ACC (p = 0.041) and COAD (p = 0.0069) were significantly associated with favorable overall survival (OS). Conversely, high LRRC8B levels in MESO correlated with a poor OS (p = 0.0015) (Fig. 4a,c). Similarly, high LRRC8C expression in KIRC (p = 0.0011), SARC (p = 0.044) and LUAD (p = 0.0095) was linked to a positive OS, while elevated LRRC8C levels in MESO (p = 0.011), LGG (p = 0.0015), and UCEC (p = 0.044) were associated with an adverse OS (Fig. 4b,d). Moreover, LRRC8D levels were found to be associated with favorable OS in CHOL (p = 0.026) and KIRC (p = 0.046) but linked to unfavorable OS in LIHC (p = 0.023), SARC (p = 0.002), UCEC (p = 0.00073), and LGG (p = 0.045) (Fig. 4e,g). Additionally, heightened LRRC8E expression in ACC (p = 0.0031) correlated with a positive OS, while elevated LRRC8E levels in MESO (p = 0.0016) and PAAD (p = 0.00052) were associated with an unfavorable OS (Fig. 4f,h). A comprehensive summary of these findings is provided in Table 2.

Association of LRRC8s expression with patient prognosis across various cancer types. (a–h) Kaplan–Meier survival curves illustrating overall survival (OS) disparities between high and low LRRC8s expression levels in various cancer types. A forest plot presenting the results of multivariate regression analysis for LRRC8s in tumors as detailed in Figs. A–D. (i) Exploration of the correlation between mRNA expression levels of specific LRRC8s family members and individual cancer stages among patients with COAD, KIRC, and PAAD, utilizing GEPIA.

The GEPIA2 tool was used in our investigation to explore LRRC8 genes and their correlation with survival outcomes. We evaluated the expression patterns of these genes across various pathological stages, as shown in Fig. 4i. Our findings indicate a clear relationship between LRRC8A expression and the stages of COAD and KICH patients, as demonstrated in Fig. S3. LRRC8B gene expression was found to be associated with the pathological stage of COAD, LRRC8C expression correlated with the pathological stage of KIRC, while LRRC8E gene expression exhibited a noteworthy positive correlation with pathological stage in PAAD patients. No data were available for LRRC8D, and no apparent association was observed between LRRC8A/B/C/E expression and the stages of other reported tumors.

Therefore, variations in LRRC8 family expression at different TNM (Tumor, Node, Metastasis) stages serve as a potential indicator for predicting cancer progression during clinical treatment.

Diagnostic value of VRAC subunits in pan-cancer

Figures 5 and S4 illustrate the results of receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analyses for the genetic variants LRRC8A, LRRC8B, LRRC8C, LRRC8D, and LRRC8E, assessed based on gene expression across various cancer types. These analyses were conducted using a pan-cancer approach, with data sourced from the TCGA database and processed using bioinformatics tools in RStudio. Insufficient data from healthy samples precluded the generation of ROC curves for TGCT, OV, and SKCM. The diagnostic efficacy of the LRRC8 subunits was evaluated through the calculation of Area Under the Curve (AUC) values, which provide a measure of diagnostic accuracy. An AUC value of 0.90 or above is indicative of excellent diagnostic performance in specific cancers.

ROC curves for various TCGA cancer types. ROC curves for several cancer types within the TCGA database. The curves demonstrate the performance of different models, with the AUC scores indicating the diagnostic ability of the models to distinguish between the presence and absence of the specific cancer type based on genomic data. AUC values > 0.7.

The analysis identified seven tumor types with an AUC value exceeding 0.90, indicating a strong diagnostic performance. These include CESC (LRRC8B), KICH (LRRC8D), STAD (LRRC8B, LRRC8D), READ (LRRC8E), COAD (LRRC8E), LUSC (LRRC8D), and LUAD (LRRC8C), as illustrated in Fig. 5.

Furthermore, the LRRC8 subunits demonstrated considerable diagnostic potential in 17 additional cancer types, with AUC values exceeding 0.7, thereby reinforcing their status as promising diagnostic biomarkers. These cancers include breast (LRRC8C, LRRC8E), pancreas (LRRC8C), brain (LRRC8B, LRRC8C), thyroid (LRRC8D), lung (LRRC8B, LRRC8C, LLRC8D), colon (LRRC8B), rectum (LRRC8C), and head and neck (LRRC8A, LRRC8C). The elevated expression levels of these subunits, which correlate with cancer progression, suggest their potential utility not only for diagnostic purposes but also for monitoring treatment responses and predicting disease outcomes. This highlights the potential of VRAC subunits as integral components in a broader diagnostic framework, particularly when used in combination with other established biomarkers to enhance diagnostic accuracy across a variety of cancers.

Nevertheless, the diagnostic efficacy of the LRRC8 subunits was not uniform across all cancer types. In certain instances, the AUC values were less than 0.6, Specifically, this included cancers such as KIRP (LRRC8A, LRRC8B, LRRC8D, LRRC8E), LIHC (LRRC8B), READ (LRRC8A, LRRC8B), COAD (LRRC8D), LUAD (LRRC8E), and GBM (LRRC8A, LRRC8B). In these cases, the subunits demonstrated an insufficient diagnostic capacity, thereby suggesting that they may not be reliable standalone biomarkers in the context of these specific cancer types (see Fig. S4).While an AUC value above 0.5 indicates some level of diagnostic potential, biomarkers with values approaching this threshold warrant further investigation to ascertain their clinical relevance. The observed variability in diagnostic performance underscores the necessity for a combination of LRRC8 subunits or integration with other biomarkers to enhance diagnostic accuracy. It is recommended that future research focus on such combinatorial approaches, which seek to leverage the complementary strengths of multiple biomarkers to enhance predictive performance across a wider range of cancers.

This analysis was based on data from the TCGA database, which is a comprehensive, multi-dimensional resource that provides gene expression profiles across a broad spectrum of cancers. By employing a pan-cancer methodology, we were able to conduct a comprehensive evaluation of the LRRC8 subunits, identifying consistent expression patterns and diagnostic capabilities across diverse tissue types. These findings underscore the importance of VRAC subunits in the early detection and monitoring of cancer progression, particularly in the context of personalized medicine. While the high AUC values in several cancer types highlight the diagnostic potential of these subunits, the variability in performance (with some AUC values below 0.6) underscores the necessity of biomarker combinations to achieve optimal diagnostic accuracy in certain cancers.

Genetic alteration and analysis of the methylation level of VRAC subunits in pan-cancer

The connection between gene expression and its influence on cancer patient survival (OS) is multifaceted. While alterations in gene expression offer crucial insights into tumor biology, they represent just one facet influencing survival outcomes. Various factors intricately interact with gene expression to shape clinical outcomes in cancer. Acknowledging the substantial impact of abnormal genomic alterations on malignancies, we conducted a comparative analysis of LRRC8s via the cBioPortal database to elucidate genomic mutations across all subunits in different cancer types. As previously documented74,75, our analysis reveals a predominance of missense mutations or truncating, in-frame alterations in LRRC8 genes, with amplifications, multiple alterations, or deep deletions occurring less frequently, particularly homozygous deletions in non-aneuploidy cases. Figure 6a provides a detailed overview of the specific genetic modifications of individual LRRC8 genes. Our investigation further highlights the highest incidence of mutations in UCEC across all VRAC subunits. Specifically, LRRC8A, LRRC8B, LRRC8C, and LRRC8D demonstrate the highest mutation rates within UCEC, while LRRC8E exhibits the highest incidence of deep deletions. LRRC8A and LRRC8B mutations are commonly identified in STAD, whereas LRRC8C and LRRC8D mutations predominate in SKCM. Additionally, the highest incidence of amplification is observed in SARC for LRRC8B, LRRC8C, LRRC8D, and LRRC8E (Fig. 6a). Figure 6b emphasizes the potential contributions of R92Q/* to cancer pathogenesis in LRRC8B, along with A484V and R671H/C for LRRC8C and LRRC8D, respectively. Additionally, Fig. 6b depicts the implication of a frame shift deletion (P454Rfs*33/L456Afs*156) in the development of UCEC, STAD, and COAD cancers associated with LRRC8E.

Mutation and methylation analyses conducted for LRRC8s across diverse tumors sourced from TCGA, using both the cBioPortal and UALCAN tools. (a, b) The analysis conducted using cBioPortal revealed the mutation type, frequency, and sites of LRRC8s across various cancer types. (c) The UALCAN tool was used to examine beta values, which indicate the promoter methylation level among different LRRC8s family members in specific carcinomas, and to compare normal and tumor tissues.

DNA methylation is a common form of epigenetic modification. Aberrant DNA methylation may exist in tumor cells. In this study, we used the UALCAN database to compare the methylation levels of LRRC8s in normal and cancerous tissues. Our findings, as illustrated in Fig. 6c, we found that the promoter methylation level of LRRC8A decreased in most cancers, including HNSC, PAAD, and KIRC. In contrast, a notable increase of the promoter methylation level of LRRC8C and LRRC8D was observed in KIRC samples. Also, the DNA methylation level of LRRC8D promoter was markedly increased in LIHC tissues.

MethSurv was used to analyze the DNA methylation levels and survival rates for each CpG site of LRRC8s. Supplementary Tables 2–6 shows that LRRC8A, LRRC8B, LRRC8C, LRRC8D, and LRRC8E had 17, 17, 25, 31, and 16 methylation probes, respectively.

RNA methylation is a crucial in many biological functions, and its aberrant regulation is associated with cancer progression. N6-Methyladenosine (m6A), 5-Methylcytosine (m5C), N1-methyladenosine (m1A) are common modifications of RNA methylation. We explored the number of modification sites in VRAC genes, using RMBase v3.0 (Table 3).

Correlation between VRAC subunit and immune cell infiltration in pan-cancer

The tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) is a critical factor that affects the clinical prognosis of cancer patients. It consists of various immune cell populations, including innate and adaptive cells such as myeloid cells and lymphocytes, and significantly influences cancer progression. Therefore, our study aims to investigate the correlation between VRAC subunit expression and specific immune cell types in the TIME. To achieve the goal of analyzing the correlation between LRRC8s gene expression and the infiltration of distinct immune cell populations, we utilized various algorithms, including TIMER, EPIC, and QUANTISEQ. The immune cell populations analyzed included adaptive immune cells (CD8+T cells, CD4+T cells, B cells), innate immune cells (neutrophils and macrophages) and cancer associated fibroblasts (CAFs) (Fig. 7a–c).

The interplay between immune cell dynamics and LRRC8 genes expression in TCGA cancer profiles. Correlation between the expression of LRRC8 gene family members and the presence of different immune cell types (neutrophils (a), macrophages/monocytes (b), T cells CD8+ (c), and cancer-associated fibroblasts (d)) in multiple cancer datasets from TCGA is presented. Each cell in the heatmap represents the partial correlation coefficient between gene expression and immune cell abundance. The color intensity indicates the strength and direction of the correlation, with red representing a positive correlation and blue representing a negative correlation. The color saturation represents the statistical significance of the correlation.

The analysis showed that in BLCA, LRRC8A and LRRC8B levels were positively associated with neutrophil infiltration. Similarly, LRRC8B showed a positive correlation with neutrophil infiltration in THCA. LRRC8C also showed a positive correlation with neutrophil infiltration in both COAD and PAAD (Fig. 7a). Moreover, LRRC8C expression levels were positively associated with macrophage/monocyte infiltration in SKCM and STAD (Fig. 7b). In contrast, LRRC8E levels exhibited a negative correlation with macrophage/monocyte infiltration, specifically in PAAD (Fig. 7b). Furthermore, there was a negative correlation between LRRC8E expression and T-cell CD8+infiltration, especially in LUSC (Fig. 7c).

The analysis showed that LRRC8(A-D) levels were positively correlated with CAFs infiltration in various tumors (Fig. 7d). Specifically, LRRC8A levels were positively linked to BRCA, BRCA-LumA, COAD, READ, and STAD. LRRC8B levels exhibited a positive association with TGCT. LRRC8C levels demonstrated a positive association with several tumors, including BRCA, BRCA-LumA, COAD, ESCA, LIHC, LUAD, LUSC, PAAD, PRAD, READ, STAD, TGCT, and THYM. Lastly, LRRC8D levels were positively associated with PAAD.

Additionally, our study suggests that all LRRC8 subunits are correlated with various immune inhibitors and stimulators in diverse cancer types (Figs. S5–S9). LRRC8A is positively associated with most major histocompatibility complexes (MHCs) in BLCA and UCS, LRRC8B in ACC, KIRCH, and UCS, LRRC8C across all cancer types, especially TGCT, LRRC8D in KIRCH, KIRP, SARC, and UCS, and LRRC8E in ACC, GBM, KICH, and UCS (Figs. S5–S9). Additionally, our analysis indicates that LRRC8s correlate with most chemokines in pan-cancer, with exceptions including CCL1, CCL16, CCL24, and CCL27 (Figs. S5–S9). In contrast, LRRC8A, LRRC8B, LRRC8D, and LRRC8E show a negative correlation with most chemokine receptors in various malignant tumors. This is particularly evident in ESCA and LUSC for LRRC8A, COAD, ESCA, and LUSC for LRRC8D, and PAAD and BRCA for LRRC8E (Figs. S5, S8 and S9).

Functional states analysis of VRAC subunits at the single-cell level across various cancers

The expression distribution of LRRC8 subunits in pan-cancer was investigated using the CancerSEA database. The findings reveal significant involvement of LRRC8s in numerous tumor-related signaling pathways across multiple cancer types (Fig. 8a–e).

LRRC8A is positively correlated with quiescence and apoptosis in ALL, metastasis and stemness in BRCA, angiogenesis in PC, hypoxia in ODG, metastasis, and angiogenesis in LUAD, and differentiation, angiogenesis, and inflammation in RB. Conversely, LRRC8A shows a negative correlation with inflammation in BRCA, invasion in OV, DNA repair, DNA damage, and the cell cycle in RB, as well as DNA repair, DNA damage, and apoptosis in UM (Figs. 8a and S10a). LRRC8B shows a positive correlation with stemness in ALL, angiogenesis in RCC, and differentiation, inflammation, and angiogenesis in RB. On the other hand, LRRC8B exhibits a negative correlation with invasion in OV, apoptosis in CRC, DNA repair, DNA damage, and the cell cycle in RB, and UM (Figs. 8b and S10b). LRRC8C demonstrates a positive correlation with DNA damage in AML and ALL, metastasis in MEL, quiescence in RCC and PC, and inflammation, differentiation, and angiogenesis in RB. In contrast, LRRC8C shows a negative correlation with DNA repair in PC, invasion in OV, DNA repair, DNA damage, and the cell cycle in RB, as well as DNA repair, DNA damage, apoptosis, invasion, and metastasis in UM (Figs. 8c and S11a).LRRC8D is correlated positively with differentiation in ALL and the cell cycle in LUAD, angiogenesis in RB, and negatively with invasion in ALL and OV, differentiation, quiescence, inflammation, and hypoxia in LUAD, epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in CRC, DNA repair, DNA damage, apoptosis, and invasion in UM (Figs. 8d and S11b). LRRC8E shows a positive correlation with DNA repair and the cell cycle in PC. However, it shows a negative correlation with invasion and apoptosis in LUAD, the cell cycle in RCC, quiescence in PC, DNA repair, DNA damage, and the cell cycle in RB, as well as DNA repair, DNA damage, and apoptosis in UM (Figs. 8e and S12).

Drug sensitivity analysis of VRAC subunits

The drug sensitivity analysis of VRAC subunits was conducted using GSCA. In tumor samples, LRRC8A and LRRC8E expression levels were found to be negatively correlated with the 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) values of Docetaxel. Conversely, LRRC8B expression exhibited a positive correlation (Fig. 9 and Supplementary Table 7). No significant correlation was observed for LRRC8D and LRRC8C. In addition, the expression of LRRC8A and LRRC8E showed a positive correlation with the IC50 values of several drugs, such as BHG712, BIX02189, Vorinostat, Methotrexate, and Navitoclax. On the other hand, LRRC8B, LRRC8C, and LRRC8D expression exhibited a negative correlation with all the drugs reported (Fig. 9 and Supplementary Table 8).

Expression difference between LRRC8 subunits and clinicopathologic features

The analysis of LRRC8 gene family expression across different cancer stages, performed using GSCA, provides valuable insights into the correlation between these genes and cancer progression and invasion. The observed differences in expression between the early stages (I and II) and the advanced stages (III and IV) indicate that certain LRRC8 subunits may serve as valuable prognostic biomarkers for various cancers (Fig. 10).

In BRCA, the expression of LRRC8A remains relatively stable during the early stages (I and II), but there is a significant upregulation in stages III and IV (p-value = 0.02) (Fig. 10a, Supplementary Table 9). This pronounced elevation in expression, particularly in advanced clinical and pathological stages (Fig. 10b,c), suggests that LRRC8A plays a pivotal role in facilitating more aggressive tumor behavior. Similarly, LRRC8B demonstrates significantly elevated expression in stages III and IV (p-value = 0.01) (Fig. 10a, Supplementary Table 9), whereas its expression in the earlier stages is less pronounced (Fig. 10b,c). These findings indicate that both LRRC8A and LRRC8B are associated with tumor invasion and progression in the later stages of breast cancer and may serve as prognostic markers for more aggressive disease.

In COAD, LRRC8A expression does not exhibit notable changes in the early stages (p-value > 0.05) (Fig. 10a, Supplementary Table 9). However, a significant increase is observed in stage IV (p-value = 0.04) (Fig. 10b,c). Similarly, LRRC8B is significantly overexpressed in stages III and IV (p-value = 0.003), thereby corroborating the notion that both genes are actively involved in tumor progression and invasion during the advanced stages of colorectal cancer. The elevated expression at both clinical and pathological stages lends further support to the potential of these genes as markers for predicting disease advancement.

In LUAD, LRRC8D exhibits minimal expression in stages I and II, but a significant increase is observed in stage IV (p-value = 0.0017) (Fig. 10). This pattern identifies LRRC8D as a potential prognostic biomarker for advanced lung cancer, where its upregulation is particularly pronounced in the later stages of the disease, indicating its involvement in more aggressive tumor growth and progression.

In SKCM, LRRC8E shows no significant changes in expression in the early stages (I and II) (p-value > 0.05). However, there is a notable upregulation in stages III and IV (p-value = 0.047) (Fig. 10a, Supplementary Table 9). This indicates that LRRC8E plays a pivotal role in melanoma progression and invasion at more advanced stages, thereby making it a promising candidate for prognostic assessment in this cancer type.

In THCA, LRRC8E expression remains unaltered in the early stages (I and II) (p-value > 0.05) (Fig. 10a, Supplementary Table 9), but there is a notable increase in stage IV (p-value = 0.05). This suggests that alterations in LRRC8E expression are predominantly evident in advanced pathological stages and may be less discernible in the initial clinical stages. This finding suggests that LRRC8E may be a more relevant biomarker for advanced disease than for early detection.

These findings collectively underscore the potential of LRRC8 subunits as prognostic biomarkers for predicting cancer progression, particularly in the advanced stages of several cancer types. The consistent upregulation of LRRC8A, LRRC8B, LRRC8D, and LRRC8E in late-stage cancers reinforces their importance in tumor invasion and metastasis. Importantly, the variation in expression across early and late stages highlights the relevance of these genes as potential markers for disease severity and outcome prediction.

Future research should focus on validating these biomarkers in clinical settings and exploring their mechanistic roles in tumor biology. The combination of LRRC8 subunits with other molecular markers has the potential to enhance their predictive power and facilitate the development of personalized treatment strategies for a diverse range of cancers.

Functional enrichment analysis of VRAC subunits in pan-cancer

The interaction between VRAC and certain genes significantly influences the initiation and progression of various cancers. In a recent study, we utilized biotin proximity-dependent identification analysis to uncover associations between ion channels, including LRRC8/VRAC, and various cellular processes relevant to cancer18,74,75. Here, we present a PPIs network involving LRRC8B, LRRC8C, LRRC8D, and LRRC8E, accompanied by functional annotations through Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analyses76. The numbers of interacting molecules retrieved for LRRC8B, LRRC8C, LRRC8D, and LRRC8E were 34, 35, 37, and 121, respectively, sourced from the BioGRID web service (Fig. 11). The LRRC8B network depicts various proteins in terms of their interactions, with a focus on transporter activities, including volume-sensitive anion channels and nucleobase-containing compound transporters, as shown in Fig. 11a. The network surrounding LRRC8C delineates connections predominantly involving receptor activities, with a focus on G protein-coupled receptors, receptors involved in the immune response and those involved in chemotactic processes, as shown in Fig. 11b. The network diagram for LRRC8D emphasizes neurotransmitter-gated ion channels, showing functions such as dolichyl-diphosphooligosaccharide-protein glycotransferase activity and GTPase activity, shown in Fig. 11c. For LRRC8E, the network visualization highlights proteins associated with ATP-dependent protein folding and ion channel activities. A central node indicates protein folding chaperones, surrounded by proteins involved in cation and gated channel activities, among others, as shown in Fig. 11d.

Comprehensive functional mapping of LRRC8 protein interactions and activities using BioGRID and ShinyGO 0.80 analyses. (a) The interaction network of LRRC8B highlights its role in various protein transport activities, with particular emphasis on the regulation of volume-sensitive anion channels and the transport of nucleobase-containing compounds. (b) The network of LRRC8C highlights its involvement in receptor-mediated processes, with an enriched presence of G protein-coupled receptors and those integral to immune responses and chemotactic signalling. (c) The network of LRRC8D showing its involvement in neurotransmitter-gated ion channels, along with related enzymatic activities, including dolichyl-diphosphooligosaccharide protein glycotransferase and GTPase. (d) The network associated with LRRC8E shows its connectivity within protein folding mechanisms and ion channel regulation, with a central node representing protein folding chaperones and their associated cation and gated channels.

Discussion

As recently discovered, the LRRC8A is the main molecular determinant of VRAC channel36,37. For physiological function, LRRC8A must heteromerize with at least one other LRRC8 member (LRCC8B-E). VRAC is ubiquitously expressed and is involved in the volume setting, however recent studies have shown that VRAC participates in the pathogenesis and progression of various tumors, such as glioblastoma, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, ovarian cancer, cervical cancer, small-cell lung cancer, glioma, hepatocellular carcinoma, osteosarcoma, lung adenocarcinoma, alveolar carcinoma colorectal cancer77. Recent research has highlighted the crucial role of LRRC8A in coordinating multiple signaling pathways essential for metastasis, particularly in CRC78. Targeting LRRC8A proteins presents a promising biomarker-driven therapeutic strategy for CRC patients, given their expression in hematogenous metastases of human CRC samples. LRRC8A overexpression impedes proliferation while promoting migration both in vitro and in vivo. Elevated LRRC8A levels upregulate focal adhesion, Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), and chemokine signaling pathways through phosphorylation and dephosphorylation mechanisms. Inhibition of LRRC8A suppresses the Tumor Necrosis Factor-α (TNF-α) signaling cascade and TNF-α-induced migration. LRRC8A’s interaction with PIP5K1B (phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate 5-kinase type 1 beta) regulates PIP2 (Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate) formation, serving as a platform for LRRC8A-mediated cell signaling. Notably, LRRC8A autoregulates its transcription through the NF-κB1 and NF-κB2 (Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells 1/2) pathways, with an upregulated NIK/NF-κB2/LRRC8A axis detrimentally affecting colon cancer patients78. Moreover, LRRC8A influences PAAD prognosis, correlating with cell proliferation, migration, drug resistance, and immune infiltration, particularly through the regulation of CD8+T cell immune infiltration49. LRRC8A is also implicated in cisplatin sensitivity and specificity in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSC), suggesting its potential as a drug target and personalized prognostic biomarker in HNSC treatment55. Furthermore, co-expression of LRRC8A with other LRRC8 proteins results in VRACs with varying functional characteristics79. The LRRC8A/D isomer primarily facilitates the expulsion of substances such as GABA (Gamma-aminobutyric acid), taurine, and inositol from cells46,80. In contrast, the LRRC8A/E isomer is activated by intracellular oxidation, while LRRC8A/C and LRRC8A/D isomers are inhibited by oxidation48. Additionally, the LRRC8A/E isomer’s activity is significantly suppressed by a positive membrane potential compared to LRRC8A/C and LRRC8A/D isomers39.

LRRC8A- and LRRC8D-mediated uptake of cisplatin and carboplatin is essential for effectively targeting platinum (Pt) drug-sensitive tumors45,55. These LRRC8 proteins play a significant role in facilitating the transport of cisplatin and carboplatin into tumor cells, where these platinum-based drugs exert their cytotoxic effects. The efficient uptake of cisplatin and carboplatin mediated by LRRC8A and LRRC8D contributes to the efficacy of Pt-based chemotherapy in treating tumors sensitive to these drugs. Therefore, the presence and proper functioning of LRRC8A and LRRC8D are crucial for maximizing the therapeutic benefits of cisplatin and carboplatin in the treatment of Pt drug-sensitive tumors. Low gene expression levels of LRRC8A or LRRC8D in ovarian cancer and HNSC tumors reduce the benefit of Pt-based chemotherapy55. Thus, the absence of LRRC8A or LRRC8D in tumor cells may serve as a helpful marker to avoid the use of cisplatin or carboplatin. LRRC8B protein regulates the substrate specificity of the channel and contributes to intracellular calcium homeostasis by functioning as an endoplasmic reticulum leakage channel41,46. Additionally, LRRC8B mediates cell death signaling pathways induced by drugs and promotes apoptosis triggered by anticancer agents such as cisplatin through apoptotic volume decrease81. LRRC8B is also involved in Alzheimer’s disease pathology and lung transplantation complications, suggesting its potential as a therapeutic target82,83.Finally, LRRC8C plays a critical role in the VRAC within T cells84. Its absence abolishes VRAC currents and regulatory volume decrease (RVD). T cells lacking LRRC8C exhibit accelerated progression through the cell cycle, heightened proliferation and survival rates, increased influx of calcium ions, and elevated cytokine production, associated with suppressed p53 signaling84. Functionally, LRRC8C facilitates the transport of 2′3’cGAMP (2′3’ cyclic GMP-AMP) in T cells, triggering STING (Stimulator of interferon genes) and p53 activation. Inhibiting STING reproduces the effects observed in LRRC8C-deficient T cells, while overexpression of p53 impedes their enhanced T cell activity. Additionally, Lrrc8c−/−mice show improved T cell-mediated immune responses, including enhanced immunity against influenza A virus infection and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, underscoring the importance of LRRC8C-mediated cGAMP uptake in activating the STING-p53 signaling cascade and influencing adaptive immunity84.

These findings highlight the complexity of VRAC regulation by LRRC8 subunits and suggest potential differences in their roles under various cellular and physiological conditions. Further research into the mechanisms underlying LRRC8-mediated VRAC activity is crucial for a comprehensive understanding of their functions in cellular physiology and pathophysiology.

Our objective in this study was to explore the potential of using gene expression as a biomarker for predicting patient life expectancy and disease progression. We assessed the significance of the relationship between gene expression and disease progression based on the area under the ROC curve across various cancers and genes.

Our findings were investigated through meta-analysis, with the data showing consistent patterns. In this meta-analysis helped us determine whether changes in gene expression correlate with patient survival and could potentially serve as markers for either the progression or amelioration of the disease. Also, this analysis showed us that although gene expression changes can play a critical role in cancer, it always does not have a significant role in mortality. In addition, it showed that the reduction or expression of a gene has different effects in various carcinogenesis processes. For example, increasing LRRC8A gene expression plays an important role in COAD-TCGA, as seen in a high percentage of patients who died (95%CI 1.42 [1.17, 1.71]). However, in the USCE-TCGA group, the decrease in the expression of this gene is associated with the risk of cancer, making it a significant prognostic indicator. These findings help clinicians to stratify patients and tailor treatment approaches, highlighting the potential of gene expression levels as a prognostic tool. By meta-analysis, the differential expression of these genes had shown a significant effect on various kinds of cancer groups.

Our analyses demonstrated also that the LRRC8A subunit shows satisfactory diagnostic efficacy across various human cancers, with AUC values consistently exceeding 0.7. Further analyses confirmed that changes in LRRC8A expression correlate with patient survival, establishing it as a potential marker for both cancer progression and therapeutic outcomes. Specifically, LRRC8A was identified as a key biomarker in cancers such as KIRC, LIHC, UCEC, and BRCA. ROC curve analysis for LRRC8A highlights its high diagnostic accuracy in these cancers, with AUC values consistently above 0.7, underlining its significance in predicting patient outcomes. Additionally, the high expression of LRRC8A in advanced cancer stages correlates with disease progression and resistance to conventional therapies, including chemotherapy and immunotherapy. This makes LRRC8A not only a predictive biomarker but also a potential therapeutic target. Moreover, LRRC8A is strongly correlated with immune checkpoint genes, including PDCD1 (PD-1), CTLA4, and LAG3, which are known to play roles in immune evasion mechanisms. Tumors with elevated LRRC8A expression may suppress immune responses, contributing to resistance against immune checkpoint inhibitors like Pembrolizumab and Ipilimumab. Targeting LRRC8A could potentially enhance immune activity, improving patient responses to immunotherapy. LRRC8A is also associated with chemokine receptors, such as CXCR3 and CCR5, which are important for immune cell migration into the tumor microenvironment. High LRRC8A expression may block immune infiltration, further contributing to immune resistance in cancers. Targeting LRRC8A, particularly in advanced stages, could promote immune infiltration and enhance the efficacy of immunotherapies.

In terms of drug sensitivity, LRRC8A has also been linked to responsiveness to specific chemotherapeutic agents. Data from the GDSC dataset show a positive correlation between LRRC8A expression and sensitivity to drugs like BHG712, CP466722, and TL-85. Similarly, in the CTRP dataset, chemotherapy drugs such as doxorubicin, etoposide, and vincristine are positively correlated with LRRC8A expression. Given its elevated expression in cancers like BRCA, COAD, and LUAD, targeting LRRC8A in advanced cancer stages could offer a promising therapeutic approach.

The LRRC8B gene exhibits a similar expression pattern to LRRC8A in cancers such as BLCA, BRCA, and COAD. ROC curve analyses for LRRC8B in these cancers indicate high predictive power, with AUC values exceeding 0.7, suggesting its potential as a prognostic biomarker in advanced stages. LRRC8B also correlates with immune-suppressive genes like PDCD1 and LAG3, further implicating it in immune resistance mechanisms. However, unlike LRRC8A, LRRC8B shows a weaker association with drug sensitivity. Only a few drugs, such as QL-XII-59 and BIX01294, exhibit correlations, indicating that LRRC8B may play a less prominent role in current therapeutic strategies. Nevertheless, LRRC8B remains important, particularly in advanced bladder and breast cancers, where it shows high ROC scores for predicting metastasis and drug resistance.

The LRRC8C gene is highly expressed in cancers such as LUAD and SKCM, where it plays a critical role in both early detection and tumor progression. ROC curve analyses for LRRC8C indicate high accuracy, with AUC values supporting its potential as a diagnostic biomarker for early-stage cancers. As cancers progress to more advanced stages, LRRC8C becomes associated with drug resistance, particularly to agents like sorafenib and cisplatin. Data from the GDSC dataset show a negative correlation with several drugs, suggesting that increased LRRC8C expression may contribute to drug resistance. In this context, targeting LRRC8C could help to overcome resistance in lung and skin cancers, especially in advanced stages.

LRRC8D is predominantly expressed in advanced clinical stages of cancers such as COAD and STAD. ROC curve analyses for LRRC8D reveal moderate to high diagnostic accuracy in these cancers, particularly in stages T3 and T4 and in metastatic tumors. LRRC8D is also linked to resistance to oxaliplatin, a chemotherapy agent commonly used in colorectal cancer treatment. Targeting LRRC8D in advanced stages could reduce tumor progression and improve chemotherapy efficacy. Moreover, LRRC8D shows strong negative correlations with drugs like FK866, GSK1070916, and docetaxel, suggesting that tumors with high LRRC8D expression may exhibit increased resistance to these therapies.

Finally, the LRRC8E gene shows high expression in advanced stages of cancers such as STAD and READ. ROC analyses demonstrate high diagnostic accuracy for LRRC8E, indicating its potential as a biomarker for advanced cancers. LRRC8E is associated with immune evasion, particularly through its interaction with MHC molecules such as HLA-DQA1 and HLA-DRB1, implicating it in antigen presentation and immune response suppression. Additionally, LRRC8E correlates with resistance to chemotherapy agents like oxaliplatin and doxorubicin, further validating its role in predicting resistance and making it a potential therapeutic target for overcoming chemotherapy resistance.

The integration of datasets from HPA and GTEx transcriptomics datasets has provided valuable insights into the mRNA expression profiles of LRRC8A, LRRC8B, LRRC8C, LRRC8D, and LRRC8E. Distinct expression patterns were observed across various tissues and cancer types, highlighting the diverse roles of LRRC8 genes in different physiological and pathological contexts. Additionally, protein expression analysis using the CPTAC dataset and immunohistochemistry results from the HPA dataset revealed significant elevations in LRRC8 expression levels in head and neck cancer tissues, underscoring their potential as diagnostic and prognostic markers in specific cancer types. Furthermore, survival analysis using SurvivalGenie and Kaplan–Meier analysis unveiled significant associations between LRRC8 gene expression levels and patient prognosis in diverse cancer types. Elevated expression of certain LRRC8 genes was linked to either favorable or unfavorable overall survival outcomes, indicating their potential utility as prognostic indicators in clinical settings. Additionally, GEPIA2 analysis highlighted correlations between LRRC8 gene expression and survival outcomes across various pathological stages, suggesting their potential role in predicting cancer progression and guiding therapeutic decisions.

Moreover, genomic analysis using the cBioPortal database revealed a predominance of missense mutations or truncating alterations in LRRC8 genes across different cancer types, implicating their involvement in tumorigenesis. Specific mutations identified in LRRC8 genes further emphasized their potential contributions to cancer pathogenesis, highlighting the importance of understanding genomic alterations in cancer biology. Additionally, investigation into DNA methylation patterns using the UALCAN database revealed distinct methylation profiles of LRRC8s in normal and cancerous tissues, providing further insights into their regulatory mechanisms. Methylation analysis using MethSurv unveiled intricate methylation patterns across different LRRC8 subunits, suggesting potential regulatory roles in cancer progression and patient outcomes.

Our study also elucidates the intricate relationship between VRAC subunit expression and the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME), emphasizing their crucial roles in cancer progression and clinical outcomes. Employing various algorithms such as TIMER, EPIC, and QUANTISEQ, we identified significant correlations between LRRC8 gene expression and specific immune cell types within the TIME. We observed positive associations between LRRC8A and LRRC8B levels and neutrophil infiltration in BLCA and THCA, while LRRC8C exhibited similar correlations in COAD and PAAD. Additionally, LRRC8C levels showed a positive association with macrophage/monocyte infiltration in SKCM and STAD, whereas LRRC8E levels demonstrated a negative correlation with macrophage/monocyte infiltration, particularly in PAAD. Furthermore, LRRC8E expression showed a negative correlation with CD8+T-cell infiltration, especially in LUSC. Moreover, our study highlighted positive correlations between LRRC8 levels and cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) infiltration across various tumors, suggesting their potential role in modulating the tumor stroma. Additionally, we identified correlations between LRRC8 subunits and immune regulators such as major histocompatibility complexes (MHCs) and chemokines across diverse cancer types, indicating their complex interactions within the tumor microenvironment.

Using the CancerSEA database, we explored the expression distribution of LRRC8 subunits across various cancer types, revealing their significant involvement in numerous tumor-related signaling pathways. Our findings provide insights into the multifaceted roles of LRRC8 subunits in tumor-related signaling pathways across different cancer types, emphasizing their potential as targets for therapeutic intervention and prognostic assessment.

Our drug sensitivity analysis using GSCA has provided valuable insights into the development of more effective, personalized cancer therapies. By investigating the expression patterns of key LRRC8 gene family members—LRRC8A, LRRC8B, LRRC8C, LRRC8D, and LRRC8E—and their correlations with a range of chemotherapeutic and targeted drugs, we have deepened our understanding of their potential as therapeutic targets. Notably, LRRC8E and LRRC8A emerged as strong candidates for drug sensitivity, particularly in advanced-stage cancers such as melanoma, thyroid cancer (THCA), and breast cancer. The elevated expression of these genes in advanced malignancies highlights their potential as valuable targets for precision therapies, offering hope for improved outcomes in patients with aggressive cancers. This suggests that targeting LRRC8E and LRRC8A in these cancers could enhance the effectiveness of treatments, potentially improving the prognosis for patients in late-stage disease. In contrast, LRRC8C and LRRC8D exhibited stronger associations with drug resistance, indicating that cancers with high expression of these genes may require alternative or combination therapies to overcome treatment resistance. This finding emphasizes the need to customize therapeutic strategies based on the unique genetic profile of the patient’s tumor, as cancers with elevated LRRC8C and LRRC8D levels may not respond well to conventional treatments.

In conclusion, the LRRC8 gene family plays a pivotal role across a spectrum of cancer types, serving as key biomarkers for both disease progression and treatment response. The insights gained from this analysis provide a foundation for the development of more personalized and effective cancer therapies, tailored to target specific genetic vulnerabilities. By integrating these findings into clinical practice, we can make significant strides in improving patient outcomes and advancing the precision of cancer treatment strategies.