Abstract

This study investigated the baseline systemic features that predict rapid thinning of the retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) in patients with primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG). A database drawn from electronic medical records (EMRs) was searched for patients diagnosed with POAG between 2009 and 2016 who had been followed up for > 5 years with the annual evaluation of global RNFL thickness using spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. The rate of change in global RNFL thickness for each eye was determined by linear regression analysis over time. Systemic data obtained within 6 months from the time of glaucoma diagnosis were extracted from the EMRs and incorporated into a model to predict the rate of progressive RNFL thinning. The predictive model was trained and tested using a random forest (RF) method and interpreted using Shapley additive explanation plots (SHAP). The features able to explain the rate of progressive RNFL thinning were identified and interpreted. Data from 1256 eyes of 696 patients and 1107 eyes of 607 patients were included in the training and test sets, respectively. The R2 value for the RF model was 0.88 and mean absolute error of the model was 0.205 μm/year. The prediction model identified higher serum levels of aspartate aminotransferase, lower blood glucose, lower systolic blood pressure, and higher high-density lipoprotein as the four most important systemic features predicting rapid RNFL thinning over 5 years. Among the ophthalmic features, a higher global RNFL thickness and a higher intraocular pressure were the most important factors predicting rapid RNFL thinning. The study revealed baseline systemic features from the EMRs that were of predictive value for progression rate of POAG patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Glaucoma is a multifactorial disease characterized by progressive optic nerve damage and visual field loss, often leading to irreversible blindness if left untreated1. Among the various factors contributing to glaucoma progression, intraocular pressure (IOP) is the most important modifiable risk factor. However, some glaucoma patients experience disease progression even when their IOP is maintained at relatively low levels2.

Beyond IOP, there is growing recognition of the role of systemic factors in glaucoma, including advanced age, low blood pressure, and vascular dysregulation, all of which may contribute to the deterioration of visual function in glaucomatous eyes3,4,5,6. Recent analyses that have taken advantage of big data have identified a role for systemic factors in glaucomatous optic nerve damage7,8,9. However, such research mainly relies on diagnostic codes and thus is of limited accuracy for disease diagnosis. In addition, it usually does not provide objective information on disease progression and therefore is often inappropriate for predictive modeling.

Understanding the systemic risk factors for glaucoma can empower clinicians to provide more targeted and effective care beyond IOP control for patients at risk of vision loss. Our institute has a large systemic database containing the EMRs of glaucoma patients as well as a spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) database that has been compiled since 2009. These two sources of data were combined with a machine learning approach to determine the baseline systemic characteristics that predict the rapid thinning of the retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) in patients diagnosed with primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG).

Results

We initially enrolled 6643 POAG eyes of 3686 patients, with 74 explanatory variables identified from the EMRs. Eighteen explanatory variables were selected for further analysis using the stepwise elimination method. After the exclusion of 4280 eyes due to missing data, 2363 eyes of 1303 patients comprised the final study sample. The detailed information regarding the exclusion was described in Supplementary Table 1. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the included patients are summarized in Table 1. The mean follow-up period was 9.6 ± 1.4 years (range: 5.3–11.4).

Data from 1256 eyes of 696 patients and 1107 eyes of 607 patients were included in the training and test sets, respectively. Table 1 also shows the comparison of the variables in the training and test sets. The random forest (RF) prediction model had an R2 value of 0.88 and mean absolute error (MAE) of 0.205 μm/year. The R2 value for linear mixed effect model was only 0.038. The results of linear mixed model with random effect are shown in Supplementary Table 2.

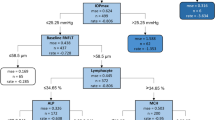

The systemic variables identified as important were analyzed based on their Shapley additive explanations (SHAP) values. Figure 1 shows the mean SHAP values (in decreasing order) and their relationship (positive or negative). The four most important systemic variables were aspartate aminotransferase (AST) level, glucose level, systolic blood pressure (SBP), and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL) level. The red dots represent greater feature values, while the blue dots represent smaller values. Positive SHAP values indicate positive contributions to the model’s prediction of global RNFL thinning, and negative values indicate negative contributions. For example, the red dots for AST level, which represent higher values, have negative SHAP values, meaning that higher AST values have the marginal impact on the higher rate of global RNFL thinning. The partial dependence plots for these variables are shown in Fig. 2. Elevated AST levels, a reduced blood glucose, a lower SBP, and higher HDL levels were associated with long-term higher rate of global RNFL thinning. The effect of a reduced glucose level had a sharp cutoff value (~ 100 mg/dL), with a faster higher rate of global RNFL thinning below the cutoff and a plateau effect above it. The influence of SBP also had a sharp cutoff value (~ 120 mmHg), with lower values associated with accelerated global RNFL thinning. Among the ophthalmic features considered, two emerged as particularly influential in predicting rapid global RNFL thinning: a higher global RNFL thickness and an increased IOP.

Model interpretation using Shapley additive explanations (SHAP), calculated with the test dataset. The SHAP value, which represents the average impact on the model’s output for each feature, is shown on the left, and the distribution of the SHAP values is given on the right. The red dots represent greater feature values, while the blue dots represent smaller values. Positive SHAP values indicate positive contributions to the model’s prediction of RNFL thinning, and negative values indicate negative contributions. RNFLT, retinal nerve fiber layer thickness; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; IOP, intraocular pressure; SBP, systolic blood pressure; HDL, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; LDL, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; BMI, body mass index; TG, triglyceride; Hb, hemoglobin.

Partial dependence plots showing the marginal effect of the features on the predictions of the model: (A) serum level of aspartate aminotransferase (AST), (B) blood level of glucose, (C) systolic blood pressure (SBP), (D) serum level of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol. Note that the SHAP value for RNFL thinning decreases toward negative values as the AST level increases (A), blood glucose level decreases (B), SBP decreases (C), and HDL increases (D). The effect of a reduced glucose level (B) and influence of SBP (C) had sharp cutoff values (~ 100 mg/dL and ~ 120 mmHg, respectively; dotted lines), with lower values associated with accelerated RNFL thinning.

Discussion

The present study was based on a large database in the EMR of POAG patients with a follow-up period of longer than 5 years. The database encompassed a wide range of potential systemic predictor variables for glaucoma progression, for which the effect on the rate of progressive global RNFL thinning and thus on glaucoma progression was quantified in a machine learning model. In addition to the well-acknowledged ophthalmic factors, the model identified several systemic factors that potentially influence the rate of RNFL thinning. The results demonstrate the predictive power of systemic data of POAG patients obtained from their EMRs.

The RF model revealed baseline systemic features related to future rapid global RNFL thinning as well as their deterministic power. Higher AST, lower blood glucose, lower SBP, and higher HDL were the four most important systemic features predicting future rapid global RNFL thinning. To the best of our knowledge, this study was the first to use a machine learning model to investigate the systemic variables associated with the rate of structural thinning of RNFL in glaucoma, and the contributions of those variables to the disease process.

Traditional regression models assume that all relationships are linear, which limits their ability to consider complex interactions between variables. By contrast, machine learning models incorporate nonlinear relationships, which improves their predictive capabilities. However, the complexity of machine learning models makes their outcomes difficult to interpret. The SHAP method offers a means to interpret the outcomes of machine learning models and thereby facilitates the exploration of variable importance and dependence.

The AST values in the study fell within the normal (~ 40 IU) to mildly elevated range. The most common causes of a mild elevation in AST values are non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and alcoholic liver disease (ALD)10. While we did not investigate the presence of NAFLD or ALD in the study population, their prevalence according to a large cohort study in South Korea is 20.9% and 4.0%, respectively11. It is therefore reasonable to assume that a significant number of the included patients had either NAFLD or ALD, and both are associated with an elevated IOP12,13. A dose–response relationship between elevated IOP and the severity of fatty liver has been reported as well12. High saturated fatty acid, cholesterol, or chronic alcohol consumption lead to an increase in pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β, IL-18, and TNF-α14, which are involved in the development of atherosclerosis. The resulting vascular dysregulation leads to an increase in IOP15. Lee et al. reported that the systemic risk factors associated with a large vertical cup-to-disk ratio include a higher AST/ALT ratio16, thus linking a higher AST value to an increased risk for glaucoma. In support of previous cross-sectional studies, the study results showed that elevated AST levels are associated with glaucoma progression. However, as only a few cases showed elevated AST levels, extrapolation of the study results to highly elevated AST levels should be made with caution.

We also identified an association between a lower baseline glucose level and a progression of glaucoma. The role of diabetes in glaucomatous optic neuropathy remains controversial. In a previous meta-analysis, high fasting blood glucose levels and diabetes were associated with a higher IOP and an increased risk for glaucoma17, whereas a recent Mendelian randomization study found no evidence of a causal association between fasting glucose/HbA1c levels and POAG18. Interestingly, in this study, glucose levels > 100 mg/dL had neither a protective nor an adverse impact on the rate of global RNFL thinning, although patients with glucose < 100 mg/dL showed higher rate of progression. The mechanisms relating diabetes to an increased risk for glaucoma include vascular damage, endothelial cell injury and dysfunction, and hypoxic damage of the optic nerve head and of the RNFL17. However, a blood level of glucose < 100 mg/dL is considered well-controlled diabetes or not diabetes, such that it might not be high enough to induce vascular damage. Instead, the association between a lower-normal blood glucose level and higher rate of global RNFL thinning detected in this study may involve hypoglycemic nerve damage, in which the decreased blood flow induced by hypoglycemia causes neural damage, as suggested in previous studies19,20. On the other hand, it should also be noted that hypoglycemic medications can also be associated with RNFL changes. For example, metformin can reduce systemic inflammation and oxidative stress and activate adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase, which is associated with neuroprotection and mitochondrial function in nerve cells21. Prospective studies incorporating hypoglycemic medications are needed to investigate the role of hypoglycemia in glaucoma progression.

A lower SBP (< 120 mmHg) was another important factor associated with higher rate of global RNFL thinning in POAG patients. Previous studies have reported an association between both systemic hypertension and hypotension and glaucoma. SBP is strongly associated with an elevated IOP22,23,24. High blood pressure increases the production of aqueous humor and decreases aqueous outflow, by elevating ciliary blood flow and episcleral venous pressure, respectively24,25. A prospective study found that a 10 mmHg increase in SBP and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) accounts for a 0.21 mmHg and 0.43 mmHg increase in IOP, respectively22. Conversely, low blood pressure, resulting in decreased ocular perfusion, is a well-established risk factor for glaucoma26. The Early Manifest Glaucoma Trial showed that a lower SBP and thus a lower baseline IOP were associated with faster OAG progression3. The role of low BP has been particularly emphasized in patients with normal-tension glaucoma (NTG), given that the vascular dysregulation associated with a low BP27,28,29, a nocturnal BP dip30,31, or BP fluctuation32,33 can have a significant impact on ocular ischemia. The patients had a relatively low IOP (mean maximum of 16.6 mmHg), suggesting a significant impact of low perfusion on progressive global RNFL thinning. The absence of an effect of SBP > 120 mmHg on the rate of global RNFL thinning was surprising. However, machine learning models may reveal more complex correlations than linear regression models. Complex interactions between BP, IOP, and other factors may therefore have caused the differential effect of SBP on the rate of global RNFL thinning. This will need to be investigated in further research. Another important thing to consider is the use of anti-hypertensive medication, such as calcium channel blockers, which may affect ocular perfusion pressure and subsequent RNFL change34.

An additional finding of this study was the association between a higher HDL level and a negative SHAP value, but only for a HDL level < 70 mg/dL. At higher levels, the relationship became irregular. Previous studies also obtained inconsistent results regarding the relationship between HDL and glaucoma, leading some authors to argue that HDL-cholesterol levels do not have a significant relationship with glaucoma35,36. However, in Kim et al.37 a low HDL was significantly associated with POAG in patients with a normal baseline IOP. Cui et al.38 recently reported a significant association between a higher IOP and lower HDL levels, but this finding was contradicted by studies reporting an association between an increased HDL and a higher IOP39,40. The influence of HDL level on the rate of global RNFL thinning is unclear, but it may be related to an elevated IOP, as previously reported. Because a lower HDL implies a higher low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL) level, glaucoma patients with a low HDL level may have benefited from statin use and its potential neuroprotective effects41,42,43. However, statin effect on the glaucoma progression could not be determined in this study due to the retrospective nature. It is also possible that the antioxidant properties of HDL have a neuroprotective role44, such that a higher level (> 70 mg/dL) decelerates progressive global RNFL thinning. As in the case of the SBP, the differential effects of HDL level on the rate of global RNFL thinning is likely to reflect complex interactions among multiple factors that remain to be elucidated.

The strengths of this study were its inclusion of a large population, the numerous systemic variables extracted from EMRs, as well as a long-term follow-up, including reliable structural information obtained by SD-OCT. However, this study also had several limitations. First, it had a retrospective design and was conducted at a single tertiary center in South Korea. The prevalence of NTG in South Korean population is much higher than in other populations45. Generalizing these results to the entire POAG spectrum, patients at other centers or of other ethnicities needs to be studied. Second, systemic variables can be affected by medications and presence of systemic diseases could have biased results. However, because the analysis was based on laboratory data, we were not able to distinguish the effect of medications and to verify the underlying systemic diseases. Third, the lack of functional data could also have biased results. Further research integrating visual field data might have promising results. Fourth, as the results do not explain the causal relationship between systemic variables and glaucoma progression, they cannot serve as guidelines for the management of systemic variables in POAG patients. The results only represent the association between systemic variables and glaucoma progression. Further prospective research is needed to prove causal relationship.

In conclusion, the predictive model constructed in this study was based on systemic features, with the aim of identifying patients at risk for future rapid glaucoma progression. Notably, higher serum AST levels, lower blood levels of glucose, decreased SBP, and higher HDL levels were the four most influential systemic factors associated with a heightened risk for rapid global RNFL thinning over 5 years, in addition to well-established ocular factors, such as a thicker baseline global RNFL and a higher IOP. The study results provide support for a comprehensive approach to the care of glaucoma patients, one that considers both systemic and ocular factors.

Methods

Participants and ophthalmic evaluation

This study included retrospective data from the EMRs of patients diagnosed with POAG between 2009 and 2016 at the Glaucoma Clinic of Seoul National University Bundang Hospital. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University Bundang Hospital (B-2401-874-105) and adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was waived by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University Bundang Hospital because of the retrospective design of the study and the use of deidentified patient information.

Patients whose EMRs included systemic test results obtained within 6 months from the time of the first OCT examinations, who were followed up in the glaucoma clinic for > 5 years, and who underwent annual SD-OCT examinations to measure circumpapillary global RNFL thickness were included in the study. A diagnosis of POAG was based on gonioscopy showing an open iridocorneal angle and signs of glaucomatous optic nerve damage (e.g., neuroretinal rim thinning, notching, or an RNFL defect) with consistent glaucomatous visual field defects. The latter was determined from standard automated perimetry findings (Humphrey Field Analyzer II 750; 24–2 Swedish interactive threshold algorithm, Carl Zeiss Meditec, Dublin, CA, USA), defined as (1) outside the normal limits in glaucoma hemifield tests, (2) a cluster of three or more non-edge points on a pattern deviation plot with a probability < 5%, with one with a probability < 1%, and/or (3) a < 5% probability of pattern standard deviation confirmed on two consecutive reliable tests, with fixation loss rates ≤ 20% and false-positive and false-negative error rates ≤ 25%. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) best corrected visual acuity worse than 20/40; a spherical equivalent ≤ − 8.0 D or ≥ 3.0 D; astigmatism ≥ 3.0 D; a history of intraocular surgery, except for uneventful cataract surgery; or a retinal (e.g., diabetic retinopathy, retinal vessel occlusion, or retinoschisis) or neurological (e.g., pituitary tumor) disease.

Determination of the rate of OCT RNFL thinning

Circumpapillary global RNFL thickness was measured using the circular scan protocol of the Spectralis OCT system (Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany). Measurements at baseline were obtained by placing a circle with a diameter of 3.5 mm concentric with the optic disc. Follow-up scans were obtained using a built-in realignment procedure. The rate of change in global RNFL thickness (expressed as microns per year) for each patient was determined by linear regression analysis over time.

Only images whose quality in Spectralis Q (signal strength) was > 15 were included. Images with motion artifacts, missing data, and/or centration errors were excluded. The accuracy of the segmentation of the RNFL was reviewed, and segmentation errors were manually corrected.

EMR data source

Systemic data obtained within 6 months from the first OCT examination were extracted from the EMRs and included the results of regular health screenings, tests from other departments, or preoperative checkups. The evaluated factors included sex, age, global RNFL thickness, maximum IOP, SBP, DBP, body mass index, blood levels of glucose and urea nitrogen, and serum levels of AST, alanine aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, creatinine, HDL, LDL, triglycerides, and hemoglobin.

Data processing and model development

All records in the data source were thoroughly organized and indexed. For the development of a machine learning model, the whole dataset was split at a 1:1 ratio to obtain training and test datasets. Both were constructed exclusively with respect to the patient and the eye, to ensure that the same eye did not belong to both the training set and the test set. For the training dataset, a random forest (RF) regressor46 with five-fold cross-validation was used for the prediction model. Because machine learning models are difficult to interpret, due to their complexity, the results of the models were interpreted using the Shapley additive explanations (SHAP) method47, a type of explainable artificial intelligence. Features with positive (negative) signs represent positive (negative) contributions to the prediction of activity. A partial dependence plot, which shows the marginal effect of one or two features on the predicted outcome of a machine learning model, was constructed as well.

Random forest

RF is a tree-based ensemble learning method for classification and regression46. During the learning phase, RF constructs multiple decision trees and reduces the risk of overfitting (a weakness of regression trees) by using the average of these trees as the final prediction. Since a random feature selection technique is employed during the generation of decision trees, diverse decision trees are created. In this study, the number of decision trees for RF learning was set at 300, with five-fold cross-validation subsequently showing that the optimal number of features for each node was three. As the performance of RF can be influenced by hyperparameters, this study conducted five-fold cross-validation and grid search over various hyperparameter values. For grid search, hyperparameter ranges were set as follows: max_features [3, 4, 5, 6, 7], max_depth: [None, 15], min_samples_split: [2, 5, 10], min_impurity_decrease: [0.0, 0.05, 0.1], ccp_alpha: [0.0, 0.1, 0.2].

Shapley additive explanations (SHAP) feature importance

The SHAP method was developed to explain the output of any machine learning model. Based on the output of a particular model, SHAP values can indicate a fair or reasonable allocation of feature importance. After the construction of a model with several features, the SHAP value is calculated by determining the average change relative to the presence or absence of any individual feature. The SHAP value of each feature is an indicator of the strength of that feature in terms of the positive or negative prediction of the model, with a larger absolute SHAP value indicating a greater impact of the feature on the model’s prediction. In this study, SHAP values were calculated to determine the contribution of each variable and its correlation with the rate of global RNFL thinning. In addition to the feature importance plot, the SHAP values were used to draw partial dependence plots depicting the marginal effects of strong systemic variables on the rate of global RNFL thinning.

Linear mixed effect model

Linear mixed effects model was developed for comparison with the machine learning models, with random effects applied at the eye level. Linear mixed models estimate the average rate of global RNFL thickness change in an outcome variable using a linear function of subject- and eye-specific deviations from this average rate are introduced by random slopes.

Data analysis

Unless stated otherwise, the data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. All statistical and machine learning analyses were performed using Python v3.11.3, with the scikit-learn package v1.0 used for regression analysis and decision tree construction, and the shap package v0.42.0 for SHAP analysis.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Kwon, Y. H., Fingert, J. H., Kuehn, M. H. & Alward, W. L. M. Primary open-angle glaucoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 360, 1113–1124 (2009).

Musch, D. C. et al. Intraocular pressure control and long-term visual field loss in the collaborative initial glaucoma treatment study. Ophthalmology 118, 1766–1773 (2011).

Leske, M. C. et al. Predictors of long-term progression in the early manifest glaucoma trial. Ophthalmology 114, 1965–1972 (2007).

Kaiser, H. J., Flammer, J., Graf, T. & Stümpfig, D. Systemic blood pressure in glaucoma patients. Graefe’s Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 231, 677–680 (1993).

Flammer, J. et al. The impact of ocular blood flow in glaucoma. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 21, 359–393 (2002).

Gherghel, D., Orgül, S., Gugleta, K., Gekkieva, M. & Flammer, J. Relationship between ocular perfusion pressure and retrobulbar blood flow in patients with glaucoma with progressive damage. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 130, 597–605 (2000).

Yoon, J. S., Kim, Y.-E., Lee, E. J., Kim, H. & Kim, T.-W. Systemic factors associated with 10-year glaucoma progression in South Korean population: A single center study based on electronic medical records. Sci. Rep. 13, 530 (2023).

Kreft, D., Doblhammer, G., Guthoff, R. F. & Frech, S. Prevalence, incidence, and risk factors of primary open-angle glaucoma—A cohort study based on longitudinal data from a German public health insurance. BMC Public Health 19, 851 (2019).

Wändell, P., Carlsson, A. C. & Ljunggren, G. Systemic diseases and their association with open-angle glaucoma in the population of Stockholm. Int. Ophthalmol. 42, 1481–1489 (2022).

Oh, R. C., Hustead, T. R., Ali, S. M. & Pantsari, M. W. Mildly elevated liver transaminase levels: Causes and evaluation. Am. Fam. Physician 96, 709–715 (2017).

Chang, Y. et al. Alcoholic and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and liver-related mortality: A cohort study. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 114, 620–629 (2019).

Lee, J.-H. et al. Fatty liver is an independent risk factor for elevated intraocular pressure. Nutrients 14, 4455 (2022).

Kwon, Y.-J., Kim, J.-H. & Jung, D.-H. Association between nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and intraocular pressure in Korean adults. J. Glaucoma 27, 1099–1104 (2018).

Fatkhullina, A. R., Peshkova, I. O. & Koltsova, E. K. The Role of cytokines in the development of atherosclerosis. Biochemistry. (Mosc) 81, 1358–1370 (2016).

Flammer, J., Haefliger, I. O., Orgül, S. & Resink, T. Vascular dysregulation: A principal risk factor for glaucomatous damage?. J. Glaucoma 8, 212–219 (1999).

Lee, M. H., Kim, H. K. & Kim, S. S. Risk factors associated with a large vertical cup-to-disc ratio: Korean national health and nutritional examination survey. J. Glaucoma 32, 221–226 (2023).

Zhao, D., Cho, J., Kim, M. H., Friedman, D. S. & Guallar, E. Diabetes, fasting glucose, and the risk of glaucoma: A meta-analysis. Ophthalmology 122, 72–78 (2015).

Hu, Z., Zhou, F., Kaminga, A. C. & Xu, H. Type 2 diabetes, fasting glucose, hemoglobin A1c levels and risk of primary open-angle glaucoma: A Mendelian randomization study. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 63, 37 (2022).

Guo, C. et al. HIF-1α accumulation in response to transient hypoglycemia may worsen diabetic eye disease. Cell Rep. 42, 111976 (2023).

Jingi, A. M., Tankeu, A. T., Ateba, N. A. & Noubiap, J. J. Mechanism of worsening diabetic retinopathy with rapid lowering of blood glucose: The synergistic hypothesis. BMC Endocr. Disord. 17, 63 (2017).

Rotermund, C., Machetanz, G. & Fitzgerald, J. C. The therapeutic potential of metformin in neurodegenerative diseases. Front. Endocrinol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2018.00400 (2018).

Klein, B. E. K., Klein, R. & Knudtson, M. D. Intraocular pressure and systemic blood pressure: Longitudinal perspective: The beaver dam eye study. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 89, 284–287 (2005).

Reddy, A. et al. The association of intraocular pressure with obesity and cardiometabolic risk in a young farmworker population. J. Glaucoma 30, 24–31 (2021).

Zhao, D., Cho, J., Kim, M. H. & Guallar, E. The association of blood pressure and primary open-angle glaucoma: A meta-analysis. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 158, 615–27.e9 (2014).

Levine, R. M., Yang, A., Brahma, V. & Martone, J. F. Management of blood pressure in patients with glaucoma. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 19, 109 (2017).

Leske, M. C. Ocular perfusion pressure and glaucoma: Clinical trial and epidemiologic findings. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 20, 73–78 (2009).

Binggeli, T., Schoetzau, A. & Konieczka, K. In glaucoma patients, low blood pressure is accompanied by vascular dysregulation. EPMA J. 9, 387–391 (2018).

Jammal, A. A. et al. Blood pressure and glaucomatous progression in a large clinical population. Ophthalmology 129, 161–170 (2022).

Lee, K. et al. Risk factors associated with structural progression in normal-tension glaucoma: Intraocular pressure, systemic blood pressure, and myopia. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 61, 35 (2020).

Shin, J. W., Jo, Y. H., Song, M. K., Won, H. J. & Kook, M. S. Nocturnal blood pressure dip and parapapillary choroidal microvasculature dropout in normal-tension glaucoma. Sci. Rep. 11, 206 (2021).

Melgarejo, J. D. et al. Glaucomatous optic neuropathy associated with nocturnal dip in blood pressure: Findings from the maracaibo aging study. Ophthalmology 125, 807–814 (2018).

Kocatürk, T. et al. Diurnal blood pressure parameters in normal tension glaucoma, primary open angle glaucoma, and healthy subjects. Anatol. J. Cardiol. 18, 62–67 (2017).

Lee, N. Y., Jung, Y., Han, K. & Park, C. K. Fluctuation in systolic blood pressure is a major systemic risk factor for development of primary open-angle glaucoma. Sci. Rep. 7, 43734 (2017).

Costa, V. P. et al. Ocular perfusion pressure in glaucoma. Acta Ophthalmol. https://doi.org/10.1111/aos.12298 (2014).

Xu, M. et al. Plasma lipid levels and risk of primary open angle glaucoma: A genetic study using Mendelian randomization. BMC Ophthalmol. 20, 390 (2020).

Shon, K. & Sung, K. R. Dyslipidemia, dyslipidemia treatment, and open-angle glaucoma in the Korean national health and nutrition examination survey. J. Glaucoma 28, 550–556 (2019).

Kim, M. J., Kim, M. J., Kim, H. S., Jeoung, J. W. & Park, K. H. Risk factors for open-angle glaucoma with normal baseline intraocular pressure in a young population: The Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Clin. Experiment. Ophthalmol. 42, 825–832 (2014).

Cui, Y. et al. Intraocular pressure in general and diabetic populations from southern china: the Dongguan eye study. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 60, 761–769 (2019).

Yokomichi, H. et al. Evaluation of the associations between changes in intraocular pressure and metabolic syndrome parameters: A retrospective cohort study in Japan. BMJ Open 6, e010360 (2016).

Kim, Y. J. et al. Association of IOP with systemic factors in a Korean cohort. Optom. Vis. Sci. 92, 1182–1188 (2015).

McCann, P., Hogg, R. E., Fallis, R. & Azuara-Blanco, A. The effect of statins on intraocular pressure and on the incidence and progression of glaucoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 57, 2729–2748 (2016).

Yuan, Y. et al. Associations of statin use with the onset and progression of open-angle glaucoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine 46, 101364 (2022).

van der Most, P. J., Dolga, A. M., Nijholt, I. M., Luiten, P. G. M. & Eisel, U. L. M. Statins: Mechanisms of neuroprotection. Prog. Neurobiol. 88, 64–75 (2009).

Denimal, D. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory functions of high-density lipoprotein in type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Antioxidants 13, 57 (2023).

Kim, C., Seong, G. J., Lee, N., Song, K., Namil Study Group, K. G. S. Prevalence of primary open-angle glaucoma in central South Korea the Namil study. Ophthalmology 118, 1024–1030 (2011).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 45, 5–32 (2001).

Lundberg, S. & Lee, S.-I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. (2017).

Funding

None of the authors have proprietary or commercial interest in any of the materials discussed in this article. This work was supported by a grant of the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Korea government (Ministry of Science and ICT) (Grant No. RS-2023-00251928), the Patient-Centered Clinical Research Coordinating Center, funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (Grant No. HC19C0276), and by the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology (No. 2016R1D1A1B02011696). The funding organizations had no role in the design or conduct of this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RO analyzed the data, drafted the initial manuscript and revised the manuscript. HK developed model, analyzed the data, and critically reviewed the manuscript. TK acquired data, conceptualized and designed the study. EJL conceptualized and designed the study, coordinated and supervised data collection, analyzed the data, critically reviewed the manuscript, and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University Bundang Hospital (B-2401–874-105) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was waived because of the retrospective design of the study and the use of deidentified patient information.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Oh, R., Kim, H., Kim, TW. et al. Predictive modeling of rapid glaucoma progression based on systemic data from electronic medical records. Sci Rep 15, 13101 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97344-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97344-1