Abstract

We investigate the mid-infrared chiroptical response of plasmonic nanostructures based on Al-doped ZnO and layers of an aqueous solution of Ladarixin, a chiral pharmaceutical currently under clinical trial for the treatment of type 1 diabetes. We explore the possibilities offered by localised surface plasmon resonances (LSPRs) for the enhancement of vibrational circular dichroism (VCD) of the considered chiral drug solution. Focusing on diverse plasmonic nanoshell geometries, we find that LSPRs provide an amplification factor of VCD differential absorption cross-section ranging from \(\simeq 3\) to \(\simeq 20\) thanks to near-field intensity enhancement produced by LSPRs. Our results indicate that nanoshell LSPRs are promising for probing molecular chirality at the nanoscale.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Enantiomers - mirror-image realizations of chiral molecules with opposite handedness - are important in pharmaceutics since they affect drug functionality/toxicity1. For this reason, chiral sensing is one of the cornerstones underpinning drug discovery, affecting its timescale and efficacy. Moreover, chiral sensing is pervasive in nanomedicine, which promises advanced platforms to optimise penetration of chiral drugs, contrast agents, detection markers, and biosensors2. Several diverse chiral sensing techniques3,4,5,6,7 enable accurate assessment of enantiomeric imbalance of solvated mixtures with volumes \(>1\) ml yet, in spite of their precision, they are not suitable for real-time analysis, lab-on-a-chip integration, and wider nanomedicine applications.

Optical sensing techniques, e.g., polarimetry8 and vibrational circular dichroism (VCD)9, offer the advantage of real-time analysis capabilities and potential lab-on-a-chip integration, and currently they are able to assess the enantiomeric excess of dilute chiral drug solutions with ml volume. Nanophotonics amplifies chiroptical sensitivity to reduced sample volumes by nanodevices10,11,12,13,14 embedded in advanced chiral spectroscopy schemes that enhance optical activity and circular dichroism (CD) thanks to engineered superchiral fields15,16. Metal-based nanostructures enable plasmon-enhanced CD spectroscopy17, which has been predicted for isolated molecules18 and adopted to characterise chirality transfer in plasmonic systems embedding chiral molecules19 and also chiral nanoparticles20,21,22. More recent predictions indicate that surface plasmon polaritons (SPPs) at the interface between a solvated chiral drug sample and a noble metal enhance electronic CD to attain sensitivity to drug nanolitres23. However, subwavelength nanostructures based on noble metals, e.g., gold or silver, display dipolar surface plasmon resonances in the visible spectrum that are far detuned from mid-IR vibrational resonances of molecules. In principle, wavelength-sized plasmonic structures based on such plasmonic materials24, e.g., silver-based nanorods, can display Mie resonances in the infrared spectral range with scaling properties and particle size dependence. However, such plasmonic excitations are multipolar and in turn their excitation by impinging plane waves is much less efficient than for electrostatic dipolar excitations. In turn, to attain plasmon-mediated sensitivity enhancement over VCD, it is necessary to employ materials displaying surface plasmon resonance in the mid-infrared (mid-IR) part of the spectrum, e.g., graphene25,26,27, oxides or nitrides28,29,30,31. While plasmon-enhanced VCD by macroscopic plasmonic structures with chiral geometrical shape in the mid-IR spectral range indicates promising functionality32,33,34,35, possibilities offered by such materials for nanophotonics-enabled chiral sensing of drug molecules are hitherto marginally explored.

Here, we investigate the potential of Al-doped ZnO (AZO) for plasmon-enhanced VCD of chiral drugs. In particular, we focus on two distinct AZO-based spherical nanoshell geometries, see Figs. 1(a,b), embedding nanometer-sized molecular layers of solvated Ladarixin, a dual allosteric inhibitor of CXCL8 (IL- 8) receptors, CXCR1 and CXCR2, currently in phase 2 and 3 trials for the treatment of diabetes36,37. We calculate the bi-anisotropic optical constants of such a chiral drug solution by a combination of Molecular Dynamics (MD), Essential Dynamics (ED), Quantum-Chemical (QC) calculations, Perturbed Matrix Method (PMM), and Time-Dependent Density Functional Theory (TD-DFT)23. We model localised surface plasmon resonances (LSPRs) of such chiral nanostructures by an electrostatic approach that we validate by electromagnetic wave frequency domain (EWFD) calculations through commercial software38. Based on the semi-analytical electrostatic approach, the selected configurations enable the derivation of intuitive and physically meaningful insights into the capabilities of AZO-based nanoshells to enhance the VCD response of chiral molecules. Such geometries enable the systematic investigation of the optical response modulation dependence over the molecular spatial distribution relative to the plasmonic structure. Because the VCD Differential Absorption (VCDDA) cross-section \(\Delta \sigma _{\textrm{abs}} = \sigma _{\textrm{R}} - \sigma _{\textrm{L}}\) by right/left circular polarisation excitation is proportional to the enantiomeric excess density \(\Delta n_{\textrm{mol}} = n_{\textrm{mol}}^{\mathrm{(S)}} - n_{\textrm{mol}}^{\mathrm{(R)}}\), by measuring VCDDA one can retrieve \(\Delta n_{\textrm{mol}}\). We observe a plasmon-induced VCDDA enhancement factor \(f_{\textrm{VCD}}\) ranging from \(\simeq 3\) to \(\simeq 20\), indicating that AZO-based plasmonic devices are promising for ultrasensitive probing of molecular chirality at the nanoscale. Moreover, the conduction electron density in AZO can be controlled by adjusting the concentration of Al doping, producing a modulation of LSPRs from near-IR to mid-IR. Depending on the doping levels, the typical LSPRs of AZO-based nanostructures lie in the \(1-10\) \(\mu\)m range, thus enabling the fine tuning of hybrid plasmon-molecular resonances amplifying VCD, as illustrated below.

Methods

(a) Schematic of the vibronic structure of Ladarixin and the considered electronic/vibrational transitions upon laser field excitation in the electric/magnetic dipole approximation. (b) Schematic illustration of the considered vibrational mode of the Ladarixin molecule dominated by the \(\mathrm{C=O}\) stretching, indicated by red circle. The blue arrows and \((^*)\) indicate the displacement vectors and chiral center of the Ladarixin molecule, respectively. (c) Conformational basins of pure R-Ladarixin enantiomer dissolved in water as obtained by projecting the MD-generated cartesian coordinates of aqueous Ladarixin onto the first two eigenvectors of the all-atom covariance matrix, calculated at temperature \(T = 298\) K. Note the presence of two distinct relevant conformation state basins in equilibrium, denoted as \(b_{\textrm{k}}\), where \(\textrm{k} =1,2\). (d) Temporal evolution of electric/magnetic transition dipole moment moduli \(|\textbf{d}_{12}|\), \(|\textbf{m}_{12}|\) and the chiral projection \(|\textbf{d}_{12} \cdot \textbf{m}_{12}|\) of a single Ladarixin molecule in the \(b_1\) conformation state calculated at each frame (expressed in nanoseconds) of MD simulations complemented with PMM calculations. A cubic simulation box with a volume of 27 \(\textrm{nm}^3\) was employed in the numerical MD simulations.

Figs. 1(a,b) illustrate the considered plasmonic nanostructures, composed of AZO-based nanosphere surrounded by a nanolayer of aqueous Ladarixin, and (b) spherical nanoshell surrounded by air and embedding aqueous Ladarixin at its core. In all cases, R and \(R+h\) indicate the inner (R) and outer (\(R+h\)) sphere radii, h is the nanoshell thickness, and the chiral sample is aqueous Ladarixin (\(\mathrm H_2O + C_{11}H_{12}F_{3}NO_{6}S_2\)). The monochromatic linear electromagnetic response of such nanostructures is accounted by bi-anisotropic constitutive relations (BACRs) linking the displacement vector \(\textbf{D}(\textbf{r},t) = \textrm{Re} [\textbf{D}_0(\textbf{r})e^{-i\omega t}]\) and the induction magnetic field \(\textbf{B}(\textbf{r},t) = \textrm{Re} [\textbf{B}_0(\textbf{r})e^{-i\omega t}]\) to the electric \(\textbf{E}(\textbf{r},t) = \textrm{Re} [\textbf{E}_0(\textbf{r})e^{-i\omega t}]\) and magnetic \(\textbf{H}(\textbf{r},t) = \textrm{Re} [\textbf{H}_0(\textbf{r})e^{-i\omega t}]\) fields with angular frequency \(\omega = 2\pi c/\lambda\), where \(\textbf{r}\) indicates the position vector of a reference frame placed at the sphere center, c is the speed of light in vacuum and \(\lambda\) is the vacuum wavelength. Explicitly, such BACRs provide

linking the monochromatic complex vector fields through complex position/wavelength-dependent effective optical profiles

where \(\epsilon _{1,2,3}(\lambda )\) are the relative dielectric permittivities (RDPs), \(\mu _{1,2,3}(\lambda )\) are the relative magnetic permeabilities (RMPs), and \(\kappa _{1,2,3}(\lambda )\) are the chiral parameters (CPs) of media 1 (nanosphere core), 2 (spherical nanoshell) and 3 (background), see Fig. 1, \(\Theta _1(r) = \Theta (R-r)\), \(\Theta _2(r) = \Theta (R+h-r)-\Theta _1(r)\), \(\Theta _3(r) = \Theta (r-R-h)\), and \(\Theta (x)\) indicates the Heaviside step-function. The two distinct nanostructures (a,b) considered in our calculations are attained by setting

where \(\epsilon _{\textrm{AZO}}(\lambda )\)is the complex RDP of AZO39, see Fig. 2(a), where we illustrate its dependence over the vacuum wavelength, \(\epsilon _\textrm{cs}(\lambda )=\epsilon _{\mathrm{H_2O}}(\lambda ) + \Delta \epsilon _\textrm{cs}(\lambda )\), \(\mu _{\textrm{cs}}(\lambda )\), and \(\kappa _\textrm{cs}(\lambda )\) are the RDP, RMP, and CP of the considered chiral sample (aqueous Ladarixin), and \(\epsilon _{\mathrm{H_2O}}(\lambda )\)is the water RDP45, whose wavelength dependence is illustrated in Fig. 2(b). To calculate the chiral sample BACR effective optical constants, we adopt a previously reported approach23 evaluating over time quantum molecular observables (QMOs) of the solvated drug, i.e., electric/magnetic dipole moments, and electronic/vibrational excitation energies and relaxation rates, schematically illustrated in Fig. 3(a). Such QMOs are taken as quantum expectation values statistically averaged over a large amount of Ladarixin-water conformations. This is accomplished by a combination of computational approaches encompassing semi-classical MD simulations to sample Ladarixin-water conformations, QC and PMM40,41,42 to obtain ensemble averages of the considered QMOs that account for semiclassical atomic-molecular motion of Ladarixin and water23. In this work, because we are interested in the mid-IR response, we calculate the highest energetic vibrational peak by the quantum chemistry approach illustrated above. Such a peak in Ladarixin arises from the C=O stretching, as illustrated in Fig. 3(b). The eigenvector of the mass-weighted Hessian used for evaluating the vibrational resonance frequency is dominated by the C=O stretching whose chirality can be estimated by the angle between the associated electric and magnetic transition dipoles equal to \(86^{\circ }\) (achiral modes display an angle exactly equal to \(90^{\circ }\)). Hence, the selected vibrational mode is inherently chiral owing to the Ladarixin chiral center depicted in Fig. 3(b). From such a complex combination of computational approaches, we observe two high probability Ladarixin-water conformation states that are representative of free-energy minima basins, see Fig. 3(c) for the case of Ladarixin R enantiomer, obtained by MD simulations and ED analysis. Fig. 3(d) illustrates the temporal evolution of Ladarixin electric (\(\textbf{d}_{12}\)) and magnetic (\(\textbf{m}_{12}\)) transition dipole moments of the lowest-energy electronic transition from the ground state to the first excited electronic state, along with the temporal evolution of the (chirally sensitive) pseudoscalar chiral projection (\(\textbf{d}_{12}\cdot \textbf{m}_{12}\)) for the initial 5 ns of the 10 ns long MD simulations. We emphasize that for flexible aqueous molecules such as Ladarixin in aqueous solution, vibronic transitions do not affect the UV spectral shape, dominated by chromophore-solvent conformational transitions. We emphasize that, thanks to selection rules, we consider only the most energetic vibrational transition producing resonant mid-IR response. The vibrational energies and transition dipole moments are taken as independent over the Ladarixin conformational state because we find that the nature of the vibrational modes coincides in the two conformational states. We model radiation-matter interaction by density matrix equations in the electric/magnetic dipole approximation, which we solve perturbatively to obtain expectation values of the induced electric/magnetic dipole moments produced by the external radiation23. Such results for the induced electric/magnetic dipoles are ensemble-averaged through weighted time-averages of the QMOs over the \(\simeq\)ns MD timescale by adopting the ergodic assumption. Thus, in the evaluation of the BACR optical constants, we account for the temporal evolution of Ladarixin over distinct conformational states produced by the interaction with the solvent (water). Finally, owing to the random molecular orientation, we average the induced electric/magnetic dipole moments over arbitrary rotations through the Euler rotation matrix approach43,44 and calculate the macroscopic polarisation and magnetisation fields of the effective Ladarixin-water medium23, leading to Eqs. (1a,1b) [see supplementary information, where we report a MATLAB script for the calculation of \(\epsilon _\textrm{cs},\mu _{\textrm{cs}}\) and \(\kappa _{\textrm{cs}}\) for any vacuum wavelength \(\lambda\), Ladarixin total number density \(n_{\textrm{mol}}\) and enantiomeric imbalance number density \(\Delta n_{\textrm{mol}} = n_\textrm{mol}^{\mathrm{(S)}} - n_{\textrm{mol}}^{\mathrm{(R)}}\) (\(n_{\textrm{mol}}^{\mathrm{(S,R)}}\)indicates the number density of S,R enantiomers, respectively), which should be complemented with tabulated water refractive indexes and extinction coefficients, e.g., see Ref.45. While \(\epsilon _{\textrm{cs}}(\lambda )\) and \(\mu _{\textrm{cs}}(\lambda )\) do not depend over the enantiomeric imbalance number density \(\Delta n_\textrm{mol}\), the CP is proportional to \(\Delta n_{\textrm{mol}}\). Indeed, optical activity and CD disappear for racemic mixtures where \(\Delta n_{\textrm{mol}} = 0\). In the achiral case \(\kappa _1=\kappa _2=\kappa _3 = 0\) and \(\mu _1=\mu _2=\mu _3 = 1\), the nanoshell polarisability can be calculated in the electrostatic approximation by matching scalar potential solutions of the Laplace equation at the nanoshell interfaces46, providing

Dependence of (a,d) RDP correction \(\Delta \epsilon _{\textrm{r}}\), (b,e) RMP correction \(\Delta \mu _{\textrm{r}} -1\), and (c,f) CP \(\kappa\) of pure R enantiomers of solvated Ladarixin over (a-c) the vacuum wavelength \(\lambda\) for fixed molecular number density \(n_{\textrm{mol}}=10^{-2} \textrm{nm}^{-3}\), and (d-f) \(n_{\textrm{mol}}\) for fixed \(\lambda = 5.4\) \(\mathrm{\mu m}\).

where \(\alpha _0 = 3\epsilon _0\epsilon _3\tau _{>}\), \(\tau _{>} = (4/3)\pi (R+h)^3\), \(\tau _{<} = (4/3)\pi R^3\), and \(f = \tau _{<}/\tau _{>}\). In order to model the mid-IR plasmonic nanoshell VCD in the chiral case, we extend this electrostatic approach starting from Maxwell’s equations in a generic bulk chiral medium with BACR optical constants \(\epsilon (\lambda ),\mu (\lambda ),\kappa (\lambda )\) and arbitrary monochromatic radiation sources \(\rho (\textbf{r},t) = \textrm{Re}[\rho _0(\textbf{r})e^{-i\omega t}]\) (charge density) and \(\textbf{J}(\textbf{r},t) = \textrm{Re}[\textbf{J}_0(\textbf{r})e^{-i\omega t}]\) (current density). In such a generic isotropic chiral bulk medium, the monochromatic fields radiated by inhomogeneous sources can be calculated through the Green function approach, providing the analytical expressions

where \(\beta _s = (\omega /c)(\sqrt{\epsilon \mu } + s\kappa )\) are the dispersion relations of right (\(s=+1\))/left (\(s=-1\)) circularly-polarised plane waves in isotropic chiral media with polarisation index \(s=\pm 1\). In the electrostatic/magnetostatic approximation \(\omega R / c, \omega h / c<< 1\), we neglect multipoles beyond point-like electric \(\textbf{d}(\textbf{r},t) = \textrm{Re} [\textbf{d}_0e^{-i\omega t}]\) and magnetic \(\textbf{m}(\textbf{r},t) = \textrm{Re} [\textbf{m}_0e^{-i\omega t}]\) oscillating dipoles. In turn, by inserting their associated charge density \(\rho _0(\textbf{r})= - \textbf{d}_0\cdot \nabla \delta (\textbf{r})\) and current density \(\textbf{J}_0( \textbf{r})= -i\omega \textbf{d}_0 \delta (\textbf{r})-\textbf{m}_0 \times \nabla \delta (\textbf{r})\) in the expressions above, where \(\delta (\textbf{r})\) is the three-dimensional Dirac delta-function, and by taking the electrostatic approximation, one gets \(\bar{\textbf{E}}_0(\textbf{r}) = [3(\textbf{d}_0\cdot \hat{\textbf{e}}_r)\hat{\textbf{e}}_r-\textbf{d}_0]/4\pi \epsilon _0\epsilon r^3\) and \(\bar{\textbf{H}}_0(\textbf{r}) = [3(\textbf{m}_0\cdot \hat{\textbf{e}}_r)\hat{\textbf{e}}_r-\textbf{m}_0]/4\pi r^3 -i\kappa \epsilon _0 c \bar{\textbf{E}}_0(\textbf{r}) / \mu\), where \(\hat{\textbf{e}}_r = \textbf{r}/r\) is the radial unit vector. In such assumptions, the scattering of plasmonic nanoshells by an impinging circularly-polarised plane-wave with wave-vector \(\textbf{k}_0\) and vectorial amplitude \(\textbf{A}_0\) (such that \(\textbf{k}_0\cdot \textbf{A}_0=0\)) is solved by multipole expansion truncated to electric/magnetic dipole terms, obtaining the electrostatic/magnetostatic solutions \(\textbf{E}_0(\textbf{r}) = [\alpha _1 \Theta _1(r) + \alpha _2 \Theta _2(r) + e^{i\mathbf{k_0}\cdot \textbf{r}}\Theta _3(r)] \textbf{A}_0 + [\gamma _2 \Theta _2(r) + \gamma _3 \Theta _3(r)] \textbf{F}(\textbf{r})\), \(\textbf{H}_0(\textbf{r}) = [\beta _1 \Theta _1(r) + \beta _2 \Theta _2(r) -is\sqrt{\epsilon _3/\mu _3} e^{i\mathbf{k_0}\cdot \textbf{r}}\Theta _3(r)] \textbf{A}_0 /\mu _0c + [ (\delta _2 - i \kappa _2\gamma _2/\mu _2) \Theta _2(r) + (\delta _3 - i \kappa _3\gamma _3/\mu _3) \Theta _3(r)] \textbf{F}(\textbf{r})/\mu _0c\), where \(\textbf{F}(\textbf{r}) = 3(\textbf{A}_0\cdot \hat{\textbf{e}}_r)\hat{\textbf{e}}_r-\textbf{A}_0] R^3/4\pi r^3\) and \(\alpha _{1,2}\), \(\beta _{1,2}\), \(\gamma _{2,3}\), and \(\delta _{2,3}\) are field amplitudes yet to be determined. Owing to spherical symmetry, without any loss of generality one can set \(\textbf{k}_0 = k_0 \hat{\textbf{e}}_z\) and \(\textbf{A}_0 = (A_0/\sqrt{2})(\hat{\textbf{e}}_x+is\hat{\textbf{e}}_y)\), where s is the right (\(s=+1\)) or left (\(s=-1\)) circular polarisation index introduced before. The associated position-dependent displacement vectors and induction magnetic fields can be obtained from Eqs. (1a,1b). By applying boundary conditions (BCs) for the continuity of \(\textbf{D}_0(\textbf{r})\cdot \hat{\textbf{e}}_r\), \(\textbf{B}_0(\textbf{r})\cdot \hat{\textbf{e}}_r\), \(\textbf{E}_0(\textbf{r}) - [\textbf{E}_0(\textbf{r})\cdot \hat{\textbf{e}}_r]\hat{\textbf{e}}_r\) and \(\textbf{H}_0(\textbf{r}) - [\textbf{H}_0(\textbf{r})\cdot \hat{\textbf{e}}_r]\hat{\textbf{e}}_r\) at the interfaces \(\textbf{r} = R\hat{\textbf{e}}_r, (R+h)\hat{\textbf{e}}_r\), we get an \(8\times 8\) inhomogeneous algebraic system of equations (reduced from \(12\times 8\) thanks to redundancy of Maxwell’s equations, manifesting also in BCs), reported in Sec. 1 of the supplementary information, which we invert numerically to obtain all the field amplitudes \(\alpha _{1,2},\beta _{1,2},\gamma _{2,3},\delta _{2,3}\). Such semi-analytical results are compared with EWFD calculations through commercial software38.

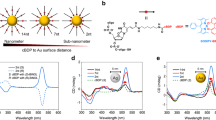

(a,b) Dependence of the absorption cross-section \(\sigma _{\textrm{abs}}(\lambda )\), upon right circular polarisation excitation [\(\sigma _{\textrm{abs}}^{(s=+1)}(\lambda )\)], over the vacuum wavelength \(\lambda\) of (a) Type-1, see Fig. 1(a), and (b) Type-2, see Fig. 1(b), plasmonic nanoshells/nanospheres embedding/embedded in pure R aqueous Ladarixin for fixed thickness \(h = 20\) nm and molecular number density \(n_{\textrm{mol}}^{(\mathrm R)}=10^{-2} \textrm{nm}^{-3}\), and several distinct radii \(R=100,200,300\) nm. (c,d) Dependence of the relative VCDDA \(\Delta \sigma _{\textrm{abs}}/\sigma _{\textrm{abs}}^\mathrm{(av)}\), where \(\Delta \sigma _{\textrm{abs}} = [\sigma _\textrm{abs}^{(s=+1)}-\sigma _{\textrm{abs}}^{(s=-1)}]\) and \(\sigma _{\textrm{abs}}^{\mathrm{(av)}} = \frac{1}{2} [\sigma _{\textrm{abs}}^{(s=+1)}+\sigma _{\textrm{abs}}^{(s=-1)}]\) over \(\lambda\) and relative enantiomeric imbalance \(\Delta n_{\textrm{mol}}/ n_{\textrm{mol}}\), where \(\Delta n_{\textrm{mol}} = n_{\textrm{mol}}^{\mathrm{(S)}}- n_{\textrm{mol}}^{\mathrm{(R)}}\) and \(n_{\textrm{mol}} = n_{\textrm{mol}}^{\mathrm{(S)}} + n_{\textrm{mol}}^{\mathrm{(R)}}\) for (c) Type-1, see Fig. 1(a), and (d) Type-2, see Fig. 1(b), plasmonic nanoshells/nanospheres embedding/embedded in pure R aqueous Ladarixin with fixed radius \(R = 100\) nm and thickness \(h=20\) nm. Black circles indicate SP-resonances of the considered AZO-based nanostructures.

Results and discussion

In Figs. 4(a-f) we illustrate the dependence of (a,d) \(\Delta \epsilon _{\textrm{cs}} = \epsilon _{\textrm{cs}} - \epsilon _{\textrm{H2O}}\), where \(\epsilon _{\textrm{H2O}}\)is the water RDP45, (b,e) \(\mu _{\textrm{cs}}-1\), and (c,f) \(\kappa _{\textrm{cs}}\) over (a-c) the vacuum wavelength \(\lambda\) for fixed \(n^{\mathrm{(R)}}_{\textrm{mol}} = n_{\textrm{mol}} = 10^{-2}\) \(\textrm{nm}^{-3}\) and (d-f) \(n^{\mathrm{(R)}}_{\textrm{mol}} = n_\textrm{mol}\) for fixed vacuum wavelength \(\lambda = 5.4\) \(\mu\)m. All plots refer to a pure R-Ladarixin dissolved in water. Note that the chiroptical response of Ladarixin is influenced by both electronic contributions (resonant at \(\lambda \simeq 236\) nm) and vibrational transitions (resonant at \(\lambda \simeq 5.4\) \(\mu\)m). The real part of \(\epsilon _{\textrm{cs}}(\lambda )\) is dominated by \(\epsilon _\textrm{H2O}(\lambda )\) due to the dilute molecular number densities considered in our calculations \(10^{-3}\) \(\hbox {nm}^{-3}< n_{\textrm{mol}} < 10^{-1}\) \(\hbox {nm}^{-3}\), see Figs. 4(a,d). Similarly, also the imaginary part of \(\epsilon _{\textrm{cs}}(\lambda )\) is dominated by the absorption of water, particularly efficient in the mid-IR. The relative magnetic permeability \(\mu _{\textrm{cs}}(\lambda )\) arises only from the Ladarixin magnetic response but (i) is chirally insensitive and (ii) provides only a minor correction to the chiral sample refractive index, see Figs. 4(b,e). Conversely, the (polarisation sensitive) CP \(\kappa _{\textrm{cs}}(\lambda )\) produces rotatory power (\(\propto \textrm{Re} [ \kappa _{\textrm{cs}}(\lambda ) ]\)) and efficient VCD (\(\propto \textrm{Im} [ \kappa _{\textrm{cs}}(\lambda ) ]\)) at the vibrational resonance of Ladarixin \(\lambda \simeq 5.4\) \(\mu \textrm{m}\), see Figs. 4(c,f), which is the focus of our investigation. Plasmon-enhanced VCDDA in the considered nanoscale environment is assessed by the absorption cross-section

where \(I_0 = (1/2)\epsilon _0c\textrm{Re}[\sqrt{\epsilon _3/\mu _3}]|\mathbf{A_0}|^2\) is the intensity of the impinging wave, \(\textbf{J}(\textbf{r},t)\) is the induced current density in the near field, and \(\langle ...\rangle _T\) indicates the time average over the single cycle \(T=2\pi /\omega\). Explicitly, \(\sigma _{\textrm{abs}} (\lambda )\) is given by

where the amplitudes \(\alpha _{1,2},\beta _{1,2},\gamma _{2,3},\delta _{2,3}\) are obtained by the numerical inversion of the \(8\times 8\) inhomogeneous algebraic system reported in Sec. 1 of the supplementary information. Results are reported in Figs. 5(a,b) for (a) Type-1, and (b) Type-2 plasmonic nanoshells/nanospheres embedding/embedded in aqueous R-Ladarixin, illustrating the dependence of \(\sigma _\textrm{abs}=\sigma _{\textrm{abs}}^{(s=+1)}\) over the vacuum wavelength \(\lambda\) for fixed nanoshell thickness \(h=20\) nm and right circular polarisation of the impinging field, and several distinct inner radii \(R=100,200,300\) nm. Full lines indicate results obtained by Eq. (6), while dashed lines indicate results obtained by EWFD calculations through commercial software38. Note that the electrostatic/magnetostatic approximation adopted in our semi-analytical approach nicely fits EWFD calculations for Type-1, see Fig. 5(a), and Type-2, see Fig. 5(b), plasmonic nanostructures with \(R\lesssim 100\) nm radius, while for larger radii retardation effects become appreciable. For Type-1 configuration we observe maximised absorption cross-section at the water-AZO LSPR wavelength \(\lambda _{\textrm{LSPR}}^{\mathrm{W-AZO}}\simeq 2.3\) \(\mu\)m, such that \(\textrm{Re}[\epsilon _{\textrm{AZO}}(\lambda _\textrm{LSPR}^{\mathrm{W-AZO}})+2\epsilon _{\textrm{cs}}(\lambda _{\textrm{LSPR}}^\mathrm{W-AZO})] = 0\), indicated by the black circles in Figs. 5(a,b). Conversely, in Type-2 configuration the absorption cross-section is maximised at hybridized water-AZO/air-AZO LSPRs that heavily depend over the inner radius R and the AZO thickness h, see black circles in Fig. 5(b). Moreover, in both configurations other absorption peaks are observed at vibrational resonances of water \(\lambda _{\mathrm{H_2O}}\simeq 3\) \(\mu\)m. Note that Ladarixin vibrational resonance is not visible in the absorption cross-section owing to the dilute molecular number density \(n_\textrm{mol} = 10^{-2}\) \(\hbox {nm}^{-3}\).

We evaluate plasmon-enhanced VCDDA by the differential absorption cross-section \(\Delta \sigma _{\textrm{abs}} = \sigma _{\textrm{abs}}^{(s = +1)} - \sigma _{\textrm{abs}}^{(s = -1)}\) obtained as the difference upon right (\(s=+1\)) and left (\(s=-1\)) circular polarisation of the incoming far-field. Results are reported in Figs. 5(c,d), illustrating the relative VCDDA \(\Delta \sigma _{\textrm{abs}} / \sigma _{\textrm{abs}}^{\textrm{av}}\) calculated by our semi-analytical approach, where \(\sigma _{\textrm{abs}}^{\textrm{av}} = (1/2)[\sigma _\textrm{abs}^{(s = +1)} + \sigma _{\textrm{abs}}^{(s = -1)}]\) is the average VCD absorption cross section, as a function of the vacuum wavelength \(\lambda\) and the relative enantiomeric imbalance \(\Delta n_\textrm{mol}/n_{\textrm{mol}}\) for (c) Type-1 and (d) Type-2 plasmonic nanoshells with inner radius \(R = 100\) nm and thickness \(h = 20\) nm embedding aqueous Ladarixin with mixed enantiomer content. Because water and AZO are not optically active, the observed VCDDA only arises from Ladarixin enantiomeric imbalance. Note that, owing to the small CP amplitude \(|\kappa _{\textrm{cs}}|\lesssim 10^{-6}\) of the aqueous Ladarixin chiral mixture, also the relative VCDDA \(\Delta \sigma _{\textrm{abs}} / \sigma _{\textrm{abs}}^{\textrm{av}}\lesssim 10^{-6}\) assumes similar values at the Ladarixin vibrational resonance \(\lambda _{\textrm{Lad}}\simeq 5.4\) \(\mu \textrm{m}\). For this reason, EWFD calculations provide noisy results, which we do not report here, due to the insufficient numerical precision required to simulate this effect. Conversely, our semi-analytical approach enables the accurate evaluation of \(\Delta \sigma _{\textrm{abs}} / \sigma _\textrm{abs}^{\textrm{av}}\) in the electrostatic/magnetostatic regime \(R\lesssim 100\) nm. Note that, when the relative enantiomeric imbalance vanishes \(\Delta n_{\textrm{mol}}/n_{\textrm{mol}} = 0\) also the relative VCDDA vanishes accordingly \(\Delta \sigma _{\textrm{abs}} / \sigma _\textrm{abs}^{\textrm{av}}=0\) owing to the CP proportionality to enantiomeric imbalance \(\kappa _{\textrm{cs}} \propto \Delta n_{\textrm{mol}}\), which produces a sign flip of \(\Delta \sigma _{\textrm{abs}} / \sigma _\textrm{abs}^{\textrm{av}}\) for opposite enantiomeric imbalance, see Figs. 5(c,d). Note also that for Type-1 configuration the observed single peak arises from the resonant CP imaginary part \(\textrm{Im}[\kappa _{\textrm{cs}}(\lambda )]\), see Fig. 5(c), in Type-2 configuration this peak splits into two opposite peaks owing to the chirality-induced LSPR shift accounted by \(\textrm{Re}[\kappa _{\textrm{cs}}(\lambda )]\), see Fig. 5(d).

In Type-1 plasmonic nanostrutures, the aqueous shell of molecules around an AZO nanoparticle facilitates the investigation of enhancement effects arising from the near-field influence at the nanoparticle surface. Although achieving an ideal aqueous shell around a single nanoparticle is experimentally challenging, an analogous system can be attained by various techniques, e.g., by dispersing nanoparticles in the molecular solution, thin-film formation on top of nanoparticles, and chemically attaching the coating of the solution onto the nanoparticle surface. Indeed, the Type-1 nanoshell results provide also insights into plasmon-enhanced VCD of plasmonic nanoparticles dispersed in solution when the aqueous layer thickness becomes larger. We focus on the nanoshell geometry because a formal derivation of the absorption cross-section of a nanoparticle surrounded by an infinite absorbing medium is ill-posed and we maintain the whole structure to be subwavelength in order to keep within the validity limits of the electrostatic approximation. Type-2 core-shell arrangement serves the purpose of sensing applications employing plasmonic nanocavities. Fabricating a completely sealed AZO shell is experimentally unfeasible, but a physical approximation of such geometry could be achievable in the form of porous hollow nanoshells allowing for diffusion of the chiral molecular solution within the nanostructure. Furthermore, advanced fabrication techniques have been developed to design hollow micro/nano-structures embedding drugs for biomedical applications47,48. These strategies include hard-templating, soft-templating and self-templating synthesis to produce core-shell arrangements based on sacrificial template approaches49. Future experimental developments could employ analogous methods for AZO-based nanostructures.

(a) Dependence of the VCD enhancement factors \(f_{\textrm{VCD}}(\lambda )\) of the distinct AZO-based nanostructures [Type-1,2, see Figs. 1(a,b)] over the vacuum wavelength \(\lambda\) for aqueous R-Ladarixin with fixed molecular number density \(n_{\textrm{mol}} = n_{\textrm{mol}}^{\mathrm{(R)}} = 10^{-2}\) \(\hbox {nm}^{-3}\) and plasmonic nanoshells with fixed inner radius \(R=100\) nm and thickness \(h = 20\) nm. The blue/red curve indicates \(f_\textrm{VCD}(\lambda )\) of Type-1/Type-2 AZO-based plasmonic nanoshells, respectively. (b,c) Dependence of the absolute value of VCDDA in the presence (\(|\Delta \sigma _{\textrm{abs}}|\)) and absence (\(|\Delta \Sigma _{\textrm{abs}}|\)) of AZO-based nanostructures over \(\lambda\) for (b) Type-1, see Fig. 1(a), and (c) Type-2, see Fig. 1(b), plasmonic nanoshells/nanospheres for \(R = 100\) nm and \(h=20\) nm.

To assess the performance of the distinct nanostructures for plasmon-enhanced VCD, we introduce the enhancement factor \(f_\textrm{VCD}(\lambda ) = \Delta \sigma _{\textrm{abs}}/\Delta \Sigma _{\textrm{abs}}\), where \(\Delta \Sigma _{\textrm{abs}}\) indicates the VCDDA in the absence of the AZO-based nanostructure, i.e., by replacing \(\epsilon _\textrm{AZO}(\lambda )\) with 1 in the expressions above. In Fig. 6(a) we compare the VCD enhancement factors of the distinct AZO-based nanostructures in the considered mid-IR wavelength range for aqueous R-Ladarixin with fixed molecular number density \(n_{\textrm{mol}} = n_{\textrm{mol}}^{\mathrm{(R)}} = 10^{-2}\) \(\hbox {nm}^{-3}\) and plasmonic nanoshells with fixed inner radius \(R=100\) nm and thickness \(h = 20\) nm. Note that both Type-1 and Type-2 plasmonic nanoshells enhance VCD at the LSPR by a factor \(\simeq 3\) for Type-1 and \(\simeq 20\) for Type-2. In turn, LSPRs of AZO-based plasmonic nanostructures provide plasmon-enhanced CD with enhancement factor comparable with noble metals23. However, Type-2 nanostructures are not well suited for plasmonic sensing because the chiral sample is placed within the nanoshell core. Conversely, Type-1 plasmonic nanostructures are more suitable for plasmon-enhanced VCD because the chiral sample is placed on the surface of the AZO-based nanosphere, but the enhancement factor is limited. Such a limitation arises from the large absorption of both AZO, see Fig. 2(a), and water, see Fig. 2(b), in the considered wavelength range. In principle, water absorption can get bypassed by the adsorption of chiral molecules on the nanosphere surface and subsequent water removal. However, molecular adsorption might depend over the enantiomeric form, thus affecting the sensing functionality.

Note that, for the considered Al doping of AZO39, the LSPRs of both Type-1 and Type-2 nanospheres/nanoshells are far detuned from the vibrational molecular resonance of Ladarixin, see Figs. 6(b,c) where we depict the wavelength dependence of the VCDDA modulus for (b) Type-1 and (c) Type-2 nanoshells. Indeed, while the considered plasmonic structures amplify the absorption cross-section at the LSPRs indicated by the dashed-black circles, they do not contribute to enhance the VCDDA at the Ladarixin vibrational resonance. However, AZO has recently emerged as a promising plasmonic material in the mid-IR displaying significant advantages (e.g., as compared to noble metals) including low-loss and particularly high-tunability of plasmonic resonances50,51. In turn, one could adjust the Al-doping level of the AZO-based nanostructure to match the vibrational resonance of Ladarixin. In order to account for the modulation produced by modified Al-doping, we fit the AZO complex RDP illustrated in Fig. 2(a) with the Drude analytical expression \(\epsilon _{\textrm{AZO}} = \epsilon _{\textrm{b}} - \omega _\textrm{P}^2/\omega (\omega +i\gamma _{\textrm{AZO}})\). Thus, by keeping fixed the background permittivity \(\epsilon _{\textrm{b}} = 3.45\), we modulate \(\omega _{\textrm{P}}\) and \(\gamma _{\textrm{AZO}} = {{\bar{\gamma }}}_\textrm{AZO}\omega _{\textrm{P}}/{{\bar{\omega }}}_{\textrm{P}}\), where \({{\bar{\gamma }}}_\textrm{AZO} = 2.56 \times 10^{14}\) \(\hbox {s}^{-1}\) and \({{\bar{\omega }}}_\textrm{P}=1.94\times 10^{15}\) rad/s are the fitted values to reproduce Fig. 2(a), to model the effect of Al-doping. In Fig. 7(a) we illustrate the dependence of \(\epsilon _{\textrm{AZO}}\) over \(\lambda\) and \(\lambda _{\textrm{P}} = 2\pi c/\omega _{\textrm{P}}\). Owing to such a RDP modulation, the absorption cross-sections of Type- 1 and Type-2 nanoshells display LSPRs shifting with the plasma wavelength, see Figs. 7(b,c) where we depict the dependence of \(\sigma _{\textrm{abs}}^{(s=+1)}\) upon right circular polarisation (\(s=+1\)) for (b) Type-1 and (c) Type-2 nanoshells with fixed \(R=100\) nm, \(h=20\) nm, and \(n_{\textrm{mol}}=n_{\textrm{mol}}^{(\mathrm R)} =10^{-2}\) \(\hbox {nm}^{-3}\). Note that for (b) \(\lambda _{\textrm{P}}\simeq 2\) \(\mu\)m and (c) \(\lambda _{\textrm{P}}\simeq 1.5\) \(\mu\)m, the considered nanostructures display plasmon-enhanced VCD resonant with the molecular vibration of Ladarixin at \(\lambda \simeq 5.4\) \(\mu\)m. Besides its appealing doping modulation properties, AZO is also compatible with Complementary Metal-Oxide-Semiconductor (CMOS) integration schemes52, thus fostering experimental and technological applications to design compact chip-based sensors. Moreover, other mid-IR plasmonic materials might be adopted to replace AZO-based nanostructures. Indium tin oxide (ITO) possesses similar optical properties to AZO53, and thus also ITO-based nanoshells provide similar (but reduced) VCD enhancement factors. Graphene plasmons are known to exhibit lower absorption thanks to the reduced number density of conduction electrons26,54, thus constituting a promising platform for plasmon-enhanced VCD. However, owing to the reduced dimensionality of graphene, our electrostatic/magnetostatic approach is not suited to provide insights on this platform and we need to extend it for future investigations.

(a) Dependence of the \(\textrm{Re}[\epsilon _{\textrm{AZO}}]\) over \(\lambda\) and plasma wavelength \(\lambda _{\textrm{P}}\)calculated from fitting RDP of AZO39 by the Drude model. (b,c) Dependence of the absorption cross-section upon right circular polarisation excitation \([\sigma _{\textrm{abs}}^{(s=+1)}(\lambda , \lambda _{\textrm{P}})]\) over \(\lambda\) and \(\lambda _{\textrm{P}}\) for (b) Type-1, see Fig. 1(a), and (c) Type-2, see Fig. 1(b), plasmonic nanoshells/nanospheres with fixed radius \(R = 100\) nm and thickness \(h=20\) nm embedding/embedded in pure R aqueous Ladarixin with molecular density \(n_{\textrm{mol}}=n_{\textrm{mol}}^{(\mathrm R)} =10^{-2}\) \(\hbox {nm}^{-3}\).

Dependence of the differential (a) electric \(\Delta \alpha _{\textrm{E}}(\lambda )\) and (a) magnetic \(\Delta \alpha _{\textrm{M}}(\lambda )\) polarisability upon right (\(s=+1\)) and left (\(s=-1\)) circular polarisation of the impinging wave with wavelength \(\lambda\). Calculations are done for Type-2 plasmonic nanoshells, see Fig. 1(b), with several radii \(R=100,200,300\) nm and thickness \(h=20\) nm, embedding pure R aqueous Ladarixin with molecular density \(n_{\textrm{mol}}=n_{\textrm{mol}}^{(\mathrm R)} =10^{-2}\) \(\hbox {nm}^{-3}\) in their core and water in background.

It is worth emphasizing that, in practical applications, Type-2 nanoshells are typically immersed in a solvent, e.g., water. However, the formal derivation of the absorption cross-section for a nanoparticle surrounded by an infinite absorbing medium like water is ill-posed. In turn, in order to evaluate the effect of the surrounding aqueous medium on the Type-2 nanoshell functionality, we consider \(\epsilon _3(\omega )=\epsilon _{\mathrm{H_2O}}(\omega )\) and evaluate the induced electric \(\textbf{d}(\textbf{r},t) = \textrm{Re}[\textbf{d}_0(\lambda ) e^{-i\omega t}]\) and magnetic \(\textbf{m}(\textbf{r},t) = \textrm{Re}[\textbf{m}_0(\lambda ) e^{-i\omega t}]\) dipole moments, obtaining \(\textbf{d}_0(\lambda )=\epsilon _0\alpha _\textrm{E}^{(s)}(\lambda )\textbf{A}_0\) and \(\textbf{m}_0(\lambda )=\alpha _\textrm{M}^{(s)}(\lambda ) (\textbf{k} \times \textbf{A}_0/\omega \mu _0)\), where \(\alpha _{\textrm{E,M}}^{(s)}(\lambda )\) are electric [\(\alpha _\textrm{E}^{(s)}(\lambda ) = \epsilon _3\gamma _3 R^3\)] and magnetic [\(\alpha _{\textrm{M}}^{(s)}(\lambda )= i s \delta _3 R^3\sqrt{\mu _3/\epsilon _3}\)] polarisabilities dependent over the impinging circular polarisation index \(s=\pm 1\), and other quantities are defined in the text above. In Fig. 8, we illustrate the dependence of the differential polarisabilities \(\Delta \alpha _{\textrm{E,M}}(\lambda ) = \alpha _{\textrm{E,M}}^{(+1)}(\lambda ) - \alpha _{\textrm{E,M}}^{(-1)}(\lambda )\) over the impinging vacuum wavelength for Type-2 plasmonic nanoshells, see Fig. 1(b), with distinct radii \(R=100,200,300\) nm and fixed thickness \(h=20\) nm, embedding pure R aqueous Ladarixin with molecular density \(n_{\textrm{mol}}=n_{\textrm{mol}}^{(\mathrm R)} =10^{-2}\) \(\hbox {nm}^{-3}\) in their core. Note that, owing to the water external background, the LSPR is blueshifted, see Fig. 5(b) for comparison. However, owing to water absorption, the LSPR quality factor is reduced and the adoption of transparent solvents in the considered spectral range is desirable in order to attain optimal functionalities. Moreover, in practical applications, the choice of specific transparent solvents can be engineered to produce LSPR shifts leading to overlapped LSPR-vibrational hybrid resonances of the specific molecule under consideration, thus enhancing the VCDDA signal.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we have investigated the potential of AZO-based plasmonic nanoshells for plasmon-enhanced VCD of chiral drug solutions. Our calculations have focused on a realistic chiral drug, aqueous Ladarixin, a dual allosteric inhibitor of CXCL8 (IL- 8) receptors, CXCR1 and CXCR2, currently in phase 2 and 3 trials for the treatment of diabetes36,37. By adopting a combination of MD, TD-DFT and PMM simulations based on a previously reported approach23, we calculated the macroscopic optical parameters of the isotropic chiral mixture. Moreover, we developed a semi-analytical electrostatic/magnetostatic approach enabling the evaluation of the absorption cross-section of plasmonic nanoshells. We corroborate our model by comparing semi-analytical results with EWFD calculations based on commercial software38, obtaining excellent agreement for nanoshells with radius \(\lesssim 100\) nm. We find that AZO-based plasmonic nanoshells produce VCDDA with a maximum enhancement factor ranging from 3 to 20 depending over the particular nanoshell geometry. Our results shed light on the opportunities offered by AZO-based plasmonic nanostructures for VCD nanospectroscopy of chiral drugs and advanced nanodevices for drugs characterization.

Data availibility

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Nguyen, L. A., He, H. & Pham-Huy, C. Chiral drugs: an overview. Int J Biomed Sci. 2, 85–100 (2006).

Tran, S., DeGiovanni, P.-J., Piel, B. & Rai, P. Cancer nanomedicine: a review of recent success in drug delivery. Clinical and Translational Medicine 6, 44 (2017).

Shundo, A., Labuta, J., Hill, J. P., Ishihara, S. & Ariga, K. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Signaling of Molecular Chiral Information Using an Achiral Reagent. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 9494–9495 (2009).

Deschamps, J. R. X-ray crystallography of chemical compounds. Life Sci. 86, 585–589 (2010).

Manoli, K., Magliulo, M. & Torsi, L. Chiral sensor devices for differentiation of enantiomers. Top Curr Chem. 341, 133–176 (2013).

Yu, R. B. & Quirino, J. P. Chiral Selectors in Capillary Electrophoresis: Trends during 2017–2018. Molecules 24, 1135 (2019).

Okamoto, Y. & Ikai, T. Chiral HPLC for efficient resolution of enantiomers. Chem. Soc. Rev. 37, 2593–2608 (2008).

Müller, T., Wiberg, K. B. & Vaccaro, P. H. Cavity Ring-Down Polarimetry (CRDP): A New Scheme for Probing Circular Birefringence and Circular Dichroism in the Gas Phase. J. Phys. Chem. A 104, 5959–5968 (2000).

Wesolowski, S. S. & Pivonka, D. E. A rapid alternative to X-ray crystallography for chiral determination: Case studies of vibrational circular dichroism (VCD) to advance drug discovery projects. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters 23, 4019–4025 (2013).

Mohammadi, E. et al. Nanophotonic Platforms for Enhanced Chiral Sensing. ACS Photonics 5, 2669–2675 (2018).

Pellegrini, G., Finazzi, M., Celebrano, M., Duó, L. & Biagioni, P. Surface-enhanced chiroptical spectroscopy with superchiral surface waves. Chirality 30, 993–889 (2018).

Gilroy, C. et al. Roles of Superchirality and Interference in Chiral Plasmonic Biodetection. J. Phys. Chem. C 123, 15195–15203 (2019).

Mohammadi, E. et al. Accessible Superchiral Near-Fields Driven by Tailored Electric and Magnetic Resonances in All-Dielectric Nanostructures. ACS Photonics 6, 1939–1946 (2019).

Mohammadi, E., Tittl, A., Tsakmakidis, K. L., Raziman, T. V. & Curto, A. G. Dual Nanoresonators for Ultrasensitive Chiral Detection. ACS Photonics 8, 1754–1762 (2021).

Tang, Y. & Cohen, A. E. Optical Chirality and Its Interaction with Matter. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 163901 (2010).

Tang, Y. & Cohen, A. E. Enhanced enantioselectivity in excitation of chiral molecules by superchiral light. Science 332, 333–336 (2011).

Nesterov, M. L., Yin, X., Schaferling, M., Giessen, H. & Weiss, T. The Role of Plasmon-Generated Near Fields for Enhanced Circular Dichroism Spectroscopy. ACS Photonics 3, 578–583 (2016).

Govorov, A. O. Plasmon-Induced Circular Dichroism of a Chiral Molecule in the Vicinity of Metal Nanocrystals. Application to Various Geometries. J. Phys. Chem. C 115, 7914–7923 (2011).

Govorov, A. O. & Fan, Z. Theory of Chiral Plasmonic Nanostructures Comprising Metal Nanocrystals and Chiral Molecular Media. ChemPhysChem 13, 2551–2560 (2012).

Fan, Z. & Govorov, A. O. Plasmonic Circular Dichroism of Chiral Metal Nanoparticle Assemblies. Nano Lett. 10, 2580–2587 (2010).

Slocik, J. M., Govorov, A. O. & Naik, R. R. Plasmonic Circular Dichroism of Peptide-Functionalized Gold Nanoparticles. Nano Lett. 11, 701–705 (2011).

Hu, Z. et al. Plasmonic Circular Dichroism of Gold Nanoparticle Based Nanostructures. Ad. Opt. Mater. 7, 1801590 (2019).

Venturi, M. et al. Plasmon-enhanced circular dichroism spectroscopy of chiral drug solutions. J. Chem. Phys. 159, 154703 (2023).

Khlebtsov, B. N. & Khlebtsov, N. G. Multipole Plasmons in Metal Nanorods: Scaling Properties and Dependence on Particle Size, Shape, Orientation, and Dielectric Environment. J. Phys. Chem. C 111, 11516–11527 (2007).

Bonaccorso, F., Sun, Z., Hasan, T. & Ferrari, A. C. Graphene photonics and optoelectronics. Nat. Photon. 4, 611622 (2010).

García de Abajo, F. J. Graphene Plasmonics: Challenges and Opportunities. ACS Photon. 1, 135–152 (2014).

Kong, X. T., Zhao, R., Wang, Z. & Govorov, A. O. Mid-infrared plasmonic circular dichroism generated by graphene nanodisk assemblies. Nano letters 17, 5099–5105 (2017).

Naik, G. V., Kim, J. & Boltasseva, A. Oxides and nitrides as alternative plasmonic materials in the optical range. Opt. Mater. Express 1, 1090–1099 (2011).

Kim, J. et al. Optical Properties of Gallium-Doped Zinc Oxide - A Low-Loss Plasmonic Material: First-Principles Theory and Experiment. Phys. Rev. X 3, 041037 (2013).

Naik, G. V., Shalaev, V. M. & Boltasseva, A. Alternative Plasmonic Materials: Beyond Gold and Silver. Adv. Mater. 25, 3264–3294 (2013).

Kinsey, N., DeVault, C., Boltasseva, A. & Shalaev, V. M. Near-zero-index materials for photonics. Nat. Rev. Mater. 4, 742–760 (2019).

Knipper, R., Mayerhöfer, T. G., Kopecky, V. Jr., Huebner, U. & Popp, J. Observation of giant infrared circular dichroism in plasmonic 2D-metamaterial arrays. Acs Photon. 5, 1176–1180 (2018).

Mattioli, F. et al. Plasmonic superchiral lattice resonances in the mid-infrared. Acs Photon. 7, 2676–2681 (2020).

Xu, C. et al. Expanding chiral metamaterials for retrieving fingerprints via vibrational circular dichroism. Light: Science and Applications 12, 154 (2023).

Morren, A., Ballance, A. T., Elliott, F. K. & Shumaker-Parry, J. S. Plasmon-Induced Vibrational Circular Dichroism Bands of Achiral Molecules on Gold Nanostructures with Tunable Extrinsic Chiroptical Responses. J. Phys. Chem. C 128, 15091–15102 (2024).

Castelli, V. et al. CXCR1/2 Inhibitor Ladarixin Ameliorates the Insulin Resistance of 3T3-L1 Adipocytes by Inhibiting Inflammation and Improving Insulin Signaling. Cells 10, 2324 (2021).

Piemonti, L. et al. Ladarixin, an inhibitor of the interleukin-8 receptors CXCR1 and CXCR2, in new-onset type 1 diabetes: A multicentre, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 24, 1840–1849 (2022).

Finite-element frequency domain calculations of spherical nanoshells’ absorption cross-sections have been carried out using COMSOL Multiphysics® www.comsol.com COMSOL AB, Stockholm, Sweden.

Shkondin, E. et al. Large-scale high aspect ratio Al-doped ZnO nanopillars arrays as anisotropic metamaterials. Opt. Mater. Express 7, 1606–1627 (2017).

Aschi, M., Spezia, R., Di Nola, A. & Amadei, A. A first-principles method to model perturbed electronic wavefunctions: the effect of an external homogeneous electric field. Chem. Phys. Lett. 344, 374–380 (2001).

Amadei, A., D’Alessandro, M., D’Abramo, M. & Aschi, M. Theoretical characterization of electronic states in interacting chemical systems. J. Chem. Phys. 130, 084109 (2009).

Carrillo-Parramon, O. et al. Flexible and Comprehensive Implementation of MD-PMM Approach in a General and Robust Code. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 13, 5506–5514 (2017).

Andrews, S. S. Using Rotational Averaging To Calculate the Bulk Response of Isotropic and Anisotropic Samples from Molecular Parameters. J. Chem. Educ. 81, 877–885 (2004).

Ohnoutek, L. et al. Third-harmonic Mie scattering from semiconductor nanohelices. Nature Photon. 16, 126–133 (2022).

Hale, G. M. & Querry, M. R. Optical constants of water in the 200-nm to 200-\(\mu\)m wavelength region. Appl. Opt. 12, 555–563 (1973).

Bohren, C. F., & Huffman, D. R. Absorption and Scattering of Light by Small Particles. Print ISBN 9780471293408, Online ISBN 9783527618156, https://doi.org/10.1002/9783527618156, Copyright 1998 WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, First published on 23 April 1998.

Ghosh Chaudhuri, R. & Paria, S. Core/shell nanoparticles: classes, properties, synthesis mechanisms, characterization, and applications. Chemical reviews 112, 2373–2433 (2012).

Koya, A. N. et al. Nanoporous metals: From plasmonic properties to applications in enhanced spectroscopy and photocatalysis. ACS nano 15, 6038–6060 (2021).

Wang, X., Feng, J. I., Bai, Y., Zhang, Q. & Yin, Y. Synthesis, properties, and applications of hollow micro-/nanostructures. Chemical reviews 116, 10983–11060 (2016).

Pradhan, A. K., Mundle, R. M., Santiago, K., Skuza, J. R., Xiao, B., Song, K. D., ... & Hopkins, P. E. Extreme tunability in aluminum doped zinc oxide plasmonic materials for near-infrared applications. Scientific reports 4, 6415 (2014).

Zhai, C. H., Zhang, R. J., Chen, X., Zheng, Y. X., Wang, S. Y., Liu, J., ... & Chen, L. Y. Effects of Al doping on the properties of ZnO thin films deposited by atomic layer deposition. Nanoscale research letters 11, 1-8 (2016).

Morea, M., Zang, K., Kamins, T. I., Brongersma, M. L. & Harris, J. S. Electrically tunable, CMOS-compatible metamaterial based on semiconductor nanopillars. Acs Photonics 5, 4702–4709 (2018).

Alam, M. Z., De Leon, I. & Boyd, R. W. Large optical nonlinearity of indium tin oxide in its epsilon-near-zero region. Science 352, 795–797 (2016).

Marini, A., Silveiro, I. & García de Abajo, F. J. Molecular sensing with tunable graphene plasmons. ACS Photonics 2, 876–882 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This work has been partially funded by the European Union - NextGenerationEU under the Italian Ministry of University and Research (MUR) National Innovation Ecosystem grant ECS00000041 - VITALITY - CUP E13 C22001060006. This work has been supported by the European Union under grant agreement No 101046424. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Innovation Council. Neither the European Union nor the European Innovation Council can be held responsible for them. The authors acknowledge fruitful discussions with Jens Biegert, Francesco Tani, Patrice Genevet, Samira Khadir, Remi Colom, Michele Dipalo, Giovanni Melle, Sotirios Christodoulou, and Anna Maria Cimini.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.M., R.A., and A.S. conceived the idea and worked out the theory. R.A., M.V., and G.S. performed numerical calculations. A.M. and C.F. supervised the research. All the authors discussed the results and wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Adhikary, R., Venturi, M., Salvitti, G. et al. Vibrational circular dichroism of plasmonic nanostructures embedding chiral drugs. Sci Rep 15, 13116 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97383-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97383-8