Abstract

Mammary gland development is a complex process involving dynamic interaction between the epithelial and stromal components at different critical stages, particularly around puberty. While epithelial tissue changes are well-documented, stromal mechanisms are less understood. To address this gap, this study employed histology, lipidomic, and transcriptomic analyses to investigate molecular and cellular dynamics in the mammary gland during pre-puberty (Post Natal Day (PND21)), peri-puberty (PND46), and adulthood (PND90) in rats. The epithelial area was significantly smaller at PND21 than at PND46 and PND90, with a higher complexity at PND21 compared to PND46. Significant differences in adipocyte number and size were observed between PND21, PND46, and PND90. Transcriptomic analysis revealed that 1563 genes changed significantly between PND21 and PND46, with only 14 genes altered between PND46 and PND90. Enrichment analyses indicated dynamic regulation of pathways related to proliferation, differentiation, lipid metabolism, and immune responses. In lipidomic analysis, 29/43 and 7/43 fatty acids differed significantly between PND21 - PND46 and PND46 - PND90, respectively. These results suggest that mammary gland development involves complex interactions between metabolic demands, hormonal regulation, and immune responses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The development of the mammary gland spans from fetal stages to post-lactation involution and menopause-associated involution1. Morphologically, the mature secretory gland consists of branched tubuloalveolar structures composed of bilayered ramified ducts made mainly of luminal and myoepithelial cells. These structures end in secretory alveoli containing the lactocytes, specialized milk-secreting luminal cells2. This epithelium is encompassed within a stromal tissue (also known as the fat pad), comprising predominantly adipocytes, immune cells, fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and extracellular matrix (ECM)3. The stroma serves a paracrine function pivotal in metabolism, fibroblast differentiation, immune responses, endothelial cell formation of the vascular network, and ECM dynamics4,5.

From birth to adulthood, there is an elevation in sex-steroid hormones, including estrogen, progesterone, prolactin, androgens, and other hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian hormones, collectively driving mammary gland transformation6,7. These changes induce plasticity in mammary cells regulated by hormonal and molecular events affecting the machinery. Adipocytes contribute to mammary gland development and function by secreting various adipokines such as leptins, hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), adiponectin, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), that together regulate the epithelial tissue growth and differentiation8. Additionally, adipocytes act as a lipid depot that influences the glandular microenvironments and provides milk lipids9,10. Lipids play crucial roles in regulating cell proliferation and differentiation, maintaining cellular membrane integrity, and acting as signals for modulating immune responses and protection against oxidative stress11. During mammary gland development, lipid accumulation in adipocytes is essential as it provides a rapid source of fatty acids, supports tissue thermoregulation, and enhances de novo lipogenesis during epithelial tissue development12. The presence of white adipocytes, composing white adipose tissue (WAT), is crucial for energy conservation, hormone secretion, and energy balance10, while brown adipocytes contribute to the formation of brown adipose tissue (BAT), playing a role in the thermal regulation of mammary tissue13.

During mammary gland development, integration between the stroma and the immune cell compartment also dynamically alters mammary structure and function. Although less studied, in animal models, macrophages, eosinophils, mast cells, and lymphocytes have been associated with regulating branching morphogenesis, promoting terminal bud formation (TEBs), and post-lactation regression3.

These processes are influenced by transcriptional regulations contributing to mammary tissue cell plasticity. Previous studies have utilized approaches like flow cytometry to identify cellular markers and better understand the role of different cellular lineages in mammary tissue differentiation and development7,14. Advanced techniques such as single-cell RNA sequencing have expanded our understanding of transcriptional profiles of individual cells, including adipocytes and other stromal and epithelial populations comprising the gland15,16,17. Despite these advances in understanding the processes involved in mammary gland development, there remains a lack of comprehension regarding the role of stromal tissue in this process and how the physiological functions of the tissue depend on interactions between its cellular and molecular components18. Doria et al. reported that 68 genes involved in lipid metabolism differed when the mammary epithelial cells were differentiated compared with undifferentiated or proliferative cells, which resulted in increased levels of C16:1 (Palmitelaidic acid), C18:1 (Oleic acid), C20:3 (Dihomo-γ-linolenic acid), and C20:4 (Arachidonic acid) fatty acids (FAs) and more phospholipids (PLs) in these cells19. These studies indicated a clear relation between the transcriptional regulation and the lipid compositions of the mammary gland, which could affect its development.

In this study, we utilized whole mammary tissue to compare morphological and physiological parameters from pre-puberty to adulthood, identifying differences in gene expression profiles using RNA sequencing. Furthermore, we evaluated changes in fatty acid composition using lipidomics, exploring how lipid dynamics in adipocytes impact mammary gland development and function. This integration of lipidomic and transcriptomic analyses provides a deeper understanding of the underlying mechanisms regulating mammary gland development and function, emphasizing the crucial role of adipocytes, lipids, and immune cells in these complex biological processes.

Results

Mammary epithelial and stroma undergo morphological changes across the development

To first study the development of the rat mammary gland from pre-puberty to adulthood, a total of 19 rats were used for the study: 7 rats in the pre-pubertal group (Postnatal day (PND21)), 7 in the peri-pubertal group (PND46), and 5 in the adult group (PND90) (Fig. 1A). As expected, significant differences were found in body and mammary gland weights between the PND21 and PND46 groups, and the PND21 and PND90 groups (Fig. 1B), resulting in mammary gland over body weight ratios that were smaller in PND46 and PND90 animals compared with PDN21 (Fig. 1B).

We then confirmed that those stages were reflective of major changes in the epithelium using whole-mount. As expected, the total epithelial area was found to increase during development, from an average of 0.6 cm2 for PND21 rats, to 2.6 cm2 for PND46 rats and 7.2 cm2 for PND90 rats, with significant differences among all groups (Fig. 1C–D). While the epithelial area increased, the complexity of the epithelial tissue, as measured using the number of intersections per cm2, was found to be greater in PND21 rats compared to PND46 and PND90 rats (Fig. 1D). Altogether, these results show that while the epithelial area is increasing from PND21 to PND90, the number of ramifications is maximal at PND21 and remains stable between PND46 and PND90.

Morphologic characteristics of mammary gland sampled from rats during pre-puberty (PND21), peri-puberty (PND46), and adulthood (PND90). (A) Representative diagram of mammary gland sampling. (B) Average body weight, mammary gland weight, and mammary gland weight normalized to total rat weight per group. (C) Left: representative images of whole mount for each group (scale bar 1 cm). Right: graphic representation of the skeletonized epithelium of the mammary gland obtained from those images using ImageJ. (D) Average epithelial area and epithelial complexity) for each group, obtained using whole-mount images. Graphs represent the average of the group with SD (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001).

Transcriptional dynamics and differential expression gene analysis in mammary development

To understand the composition of mammary tissue and gene expression dynamics, RNA-seq profiles were generated from mammary glands across the three developmental stages (PND21, PND46, and PND90). After quality control, a principal component analysis (PCA) was conducted to visualize the variations in gene distribution across the groups, revealing a clear separation between the PND21 group and the PND46 and PND90 groups (Fig. 2A). While pre-puberty glands were distinct, mature/adult glands exhibited a similar transcriptional profile. During the transition from PND21 to PND46, 1,582 genes were differentially expressed, as identified using DESeq2 (662 downregulated and 924 upregulated) (Fig. 2B). In contrast, only 14 genes were significantly modulated during the transition from PND46 to PND90 (1 downregulated and 13 upregulated) (Fig. 2C).

Identification of differentially expressed genes using RNA-sequencing analysis between PND21 to PND46, and PND90. (A) Principal component analysis showing the normal distribution of the groups PND21, PND46, and PND90. (B) Volcano plot illustrating the significantly upregulated (red), downregulated (blue), and not significant (not sig (grey)) genes in the transition between PND21 and PND46 of rat’s mammary gland (p-adj < 0.05, Log2FC 1.5, n = 4). (C) Volcano plot illustrating the significantly upregulated and downregulated genes in the transition between PND46 and PND90 of rat’s mammary gland (p-adj < 0.05, Log2FC ≥ 1.5, n = 4). (D) Gene Ontology enrichment analysis of biological processes for upregulated and downregulated genes during the transition between PND21 and PND46.

Gene Ontology (GO) analyses of genes differentially expressed during the transition from PND21 to PND46 revealed associations with biological processes such as fatty acid metabolism, adaptive immune response, regulation of cell-cell adhesion, and T-cell activation (Fig. 2D). Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analyses indicated that upregulated genes were enriched for chemokine signaling pathways (map04062 20–22) (Fig. S1), cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction, the transcriptional factor NF-κB, cell adhesion molecules, natural killer cell-mediated cytotoxicity, Th1 and Th2 differentiation, and B cell receptors (map04060 and map04662 20–22) (Fig. S2 A-B). To validate these RNA-seq results, we performed qPCR of specific genes. Genes associated with the immune response, which were increased over time in RNA-seq analyses (Fig. 2B), including Tnfrsf11a (TNF receptor superfamily member 11a), Irf7 (interferon regulatory factor 7), Traf1 (TNF receptor associated factor 1), and Cd3e (CD3 epsilon subunit of T-cell receptor complex), showed increased expression during the transition from PND21 to PND46 and PND90 by qPCR (Fig. S3A). These results suggest increased transcriptional activation of genes/gene networks implicated in the activity of the immune compartment.

Conversely, downregulated genes were enriched in pathways related to fatty acid biosynthesis, the TCA cycle, fatty acid elongation, pyruvate metabolism, AMPK signaling, and Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) signaling (map04923 and map03320 20–22) (Fig. S4 A-B). The AMPK signaling pathway is the guardian of metabolic health, playing a pivotal role in regulating fatty acid beta-oxidation and lipogenesis in cells, while PPAR is crucial for adipocyte differentiation23. Again, we performed qPCR validation of key target genes, including Fabp4 (fatty acid binding protein 4), Pparg (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ), and Scd (stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1). As observed in RNA-seq (Fig. 2B), all three genes were significantly lower in PND46 and PND90 compared to PND21 (Fig. S3B). These results suggest that after pre-puberty, an important metabolic reprogramming occurs, notably affecting lipid metabolism at the transcriptional level.

Relative gene expression patterns differ between developmental stages

To further understand the processes involved in mammary gland development, k-means clustering analyses were performed. Four clusters were defined based on the relative expression levels of genes in the samples, with most transcriptional signatures differentiating PND21 specifically from PND46 and PND90, which exhibited a similar profile (Fig. 3A). This result aligns with DESeq2 analyses (Fig. 2), with an overlap observed in the transcriptional profiles of the PND46 and PND90 stages. Interestingly, genes from clusters 1 and 2 generally showed a higher expression at PND21 compared with PND46 and PND90, while genes from clusters 3 and 4 showed an opposite pattern.

Pathway enrichment analyses of the clusters revealed associations with mammary gland development terms such as cellular and differentiation dynamics (Cluster 1). Genes highly expressed in cluster 1 were mainly enriched in terms of signaling pathways related to extracellular matrix reorganization, response to growth factors, cellular homeostasis, and vascular development, among others (Fig. 3B). These gene signatures are consistent with the reorganization of the gland, a process that requires epithelial tissue growth, formation and elongation of new branching through the formation of TEBs24.

Hierarchical cluster analysis by K-Means from the PND21, PND46, and PND90 groups. (A). Heatmap showing k-mean gene expression. Rows represent genes clustered using K-means clustering, and columns represent samples (n = 4) from PND21, PND46, and PND90. Metascape enrichment network visualizations of the most common genes (B) in cluster 1 related to cellular growth and differentiation dynamics, (C) in cluster 2 related to metabolic and proliferative regulation, (D) in cluster 3 related to hormonal regulation and stress response, and (E) in cluster 4 related to immune response and cellular signaling dynamics, in the mammary gland tissue from PND21, PND46, and PND90 rats. Black arrows point to the specific pathways in each cluster that relate to mammary gland development.

Cluster 2, related to metabolic and proliferative regulation, involved processes such as cell cycle regulation, oxidative phosphorylation, the tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA cycle), acyl-CoA metabolic process, and pyruvate metabolism, among other cellular metabolic processes (Fig. 3C). Changes in metabolic gene expression during development suggest an important metabolic reprogramming throughout the mammary gland evolution, notably between pre-puberty and peri-puberty/adulthood.

Cluster 3, associated with hormonal regulation and stress response, involves processes such as cell junction organization, cell morphogenesis, response to steroid hormones, reproductive structure development, and regulation of epithelial cell proliferation, supporting processes like epithelial-mesenchymal transition and proliferation of luminal and myoepithelial cells (Fig. 3D).

Finally, cluster 4 is associated with immune response and cellular signaling dynamics, including positive regulation of immune response, cytokine production, programmed cell death, leukocyte activation, and JAK-STAT signaling pathways, among others (Fig. S1). This calls our attention to the known importance of immune cells in the remodeling of mammary gland development24. Given our interest in the role of the stromal compartment, we decided to focus on clusters 2 and 4, as they are more closely related to functions generally attributed to the stroma, such as lipid metabolism and immune functions.

Metabolic and proliferative regulation across developmental stages

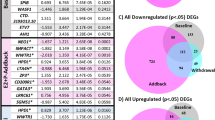

The relative gene expression data showing that cluster 2 was associated with metabolic reprogramming and with differentially expressed gene analyses suggested that metabolic pathways were affected during the PND21 to PND46 transition. An overlap analysis was thus conducted to uncover the molecular mechanisms related to metabolism and proliferative processes. This analysis compared genes in cluster 2 with genes upregulated and downregulated in the differentially expressed gene analysis. Specifically, only downregulated genes identified in differential expression analysis were part of cluster 2, with 197 genes, while no upregulated genes overlapped with this cluster (Fig. 4A). These results further emphasized that an important metabolic reprogramming at the transcriptional level during the transition from pre-puberty to peri-puberty. Downregulated genes included some related to de novo synthesis of fatty acids, such as Acetyl-CoA carboxylase-a (Acaca), Diacylglycerol O-acyltransferase 1 (Dgat1), Monoacylglycerol O-acyltransferase 2 (Mogat2), Perilipin 1 (Plin1), and Fatty acid desaturase 3 (Fads3) (Fig. S4A). Enrichment pathway analysis confirmed this relationship between downregulated genes and lipid metabolism, with enrichment of processes like acyl-CoA, adipogenesis, lipid droplet organization, and long-chain fatty acid metabolic processes that were downregulated (Fig. 3B).

Identification of lipid metabolic reprogramming pathways and adipogenesis in the transition between PND21 and PND46 via transcriptome analysis. (A) Venn diagram for overlapping significant genes downregulated and upregulated and cluster 2 during the transition between PND21 and PND46. (B) Enrichment pathway analysis using overlapping genes. (C) and (D) Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) plots for biological pathways enriched in the transition between PND21 to PND46 and PND90. Hallmarks gene sets are shown for (C) adipogenesis and (D) fatty acid metabolism during the transition between PND21 to PND46 and PND46 to PND90. NES; Normalized enrichment score. The red color indicates higher expression in heatmaps, and the blue color indicates lower expression. (E) Graphic representation of total fatty acid across developmental stages. Error bars represent SD, (***p < 0.001).

A Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) was then performed using normalized sequencing data to compare PND21 to PND46 and PND46 to PND90 rats. GSEA confirmed a significant decrease in adipogenesis and fatty acid metabolism gene sets across all stages, with normalized enrichment scores (NES) of 3.19 to 2.64 and 2.84 to 2.10 in the transition from PND21 to PND46 and from PND46 to PND90, respectively (Fig. 3C, D). Among the downregulated genes related to adipogenesis, we found Pparγ, Leptin (Lep), Adiponectin (Adipoq), CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein-a (Cebpa), and Fabp4, and genes involved in fatty acid synthesis like Fatty acid synthase (Fasn), Scd, Fabp4, Acaca, and Glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase 1 (Gpd1) (Fig. S4B), and the expression level were reduced in PND46 and PND90 compared to PND21 as validated by qPCR for specific genes (Fig. S3).

Together, these data suggest that during these developmental transitions, especially from pre-puberty to peri-puberty (PND21 to PND46), the rapid division of epithelial cells leading to the growth and elongation of epithelial tissue requires significant energy, ECM reorganization, stromal tissue, and materials like lipids, which form various cellular membranes. To further support these findings, the concentrations of fatty acids in mammary tissue were determined using gas chromatography analysis. A significant decrease in total fatty acid concentration was observed during the transition from PND21 to PND46, while no significant differences were observed during the transition from PND46 to PND90 (Fig. 3E; Table 1).

Lipid expression patterns across developmental stages

Given the changes in the transcriptional profiles during mammary gland development, we hypothesized that lipid metabolism might play a central role in mammary gland development, especially during the transition from pre-puberty to peri-puberty (PND21 to PND46). To investigate whether the differential expression of lipid metabolism genes was reflected in differential lipid abundance, we performed a lipidomic analysis and quantitatively compared the lipid profiles between the three stages of development. In our study, 43 fatty acids were quantified and classified into 15 groups based on their characteristics (Table 1). Of these, 29/43 fatty acids and 10/15 groups differed significantly between PND21 and PND46, while only 7/43 fatty acids and 0/15 groups showed differences between PND46 and PND90. Together with transcriptional analyses (Figs. 2, 3 and 4), these results highlight the profound changes in lipid metabolism that notably occur between pre-puberty and peri-puberty.

To visualize the distribution of fatty acids, we conducted PCA and found that short and medium-chain saturated fatty acids were more concentrated in the PND21 group compared to the PND46 and PND90 groups, indicating a clear separation between the lipid profile in PND21 compared to PND46 and PND90 (Fig. 5A). PND46 and PND90 exhibited a similar lipid profile (Fig. 5A). Heatmap clustering, considering fatty acid concentrations, confirmed the presence of Lipid-cluster 2 and Lipid-cluster 3, which are associated with higher concentrations of short-chain and medium-chain saturated lipids, respectively in the PND21 stage compared to PND46 and PND90 (Fig. 5B). To understand the fatty acid distribution, we performed a correlation analysis among fatty acids for each stage and compared the results between the groups (Fig. 5C). We observed an increase in positive correlation among saturated and unsaturated medium- and long-chain fatty acids during the transition from PND21 to PND46. Conversely, during the transition from PND46 to PND90, there was a strong positive correlation among fatty acids in the PND90 stage, indicating co-regulation of fatty acids and the establishment of metabolic patterns during mammary gland development in adult stages (Fig. 5C). However, we found that some lipids in PND21, such as C16:0 DMA (1,1-dimethoxyhexadecane), in PND46, such as C16:0 DMA, 13c16c19c-22:3 n3 (docosadienoic acid), and in PND90, such as C8:0 (caprylic acid), C16:0 DMA, and 9t12c-18:2 n6 (linoleic acid (trans, cis isomer)) exhibited negative correlations with the other fatty acids (Fig. 5C).

The changes of fatty acids composition across developmental stages of the mammary gland. (A) Principal component analysis showing the differential distribution of the fatty acids across the groups. (B) In the heatmap of 41 fatty acids across developmental stages, the concentration of the lipids was clustered and represented in the rows, while the samples are represented in the columns from PND21, PND46, and PND90. (C) Correlation of fatty acids showing the different lipid profiles at PND21, PND46, and PND90 groups; the red color indicates a negative correlation in the interaction between lipids and the blue color indicates a positive correlation. (D) Histogram representation of all categories of fatty acids such as saturated fatty acids, total cis fatty acids, total omega-6 fatty acids, total omega-3 fatty acids, and ratio of omega-3 to omega-6 fatty acids. Error bars represent SD (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01).

Various biological processes, such as cell growth, proliferation, and development, require the formation of new cellular components with energy and lipid demands25. Our results indicate that during the transition from PND21 to PND46, different groups of fatty acids significantly decrease in concentration within the tissue, including saturated fatty acids, total cis fatty acids, total omega-6 and omega-3, and the ratio of omega-3 to omega-6 (Fig. 5D). These fatty acids are involved in cell membrane structure, energy production, membrane fluidity, and cellular signaling, which are vital during developmental processes26. In addition, total omega-6 and omega-3 are related to inflammatory processes, acting as precursors to pro-inflammatory eicosanoids and being essential for cell growth, membrane integrity, and immune signaling pathways (Fig. 5D). In contrast, during the transition from PND46 to PND90, there was no significant alteration in the categories of fatty acids. Current data suggest modulation at the transcriptional and relative expression level as well as from alterations in lipid levels.

The fatty acids were then studied individually to determine which ones were deregulated during the different stages of mammary development. Significant changes were observed in the concentrations of saturated fatty acids, such as palmitic acid, which decreased during the transition from PND21 to PND46 but did not show significant deregulation between the transition from PND46 to PND90 (Fig. S5A). Palmitic acid is one of the main components of the cell membrane, responding to the increased proliferation of epithelial cells during the formation of TEBs27. A similar pattern was observed when investigating unsaturated fatty acids. Linoleic, oleic, arachidonic, vaccenic, adrenic, dihomo-gamma-linolenic, and eicosadienoic acids were downregulated during the transition from pre-puberty to peri-puberty only (Fig. S5B). These unsaturated fatty acids are involved in cell growth, cell membrane structure, membrane fluidity, cell signaling, and immune response28.

For other saturated fatty acids, such as caprylic, capric, lauric, myristic, and stearic acids, we observed a significant decrease during the transition from PND21 to PND46 and again from PND46 to PND90 (Fig. S5A). These fatty acids participate in processes that provide energy for rapidly growing mammary tissue cells, transport proteins, tissue maintenance, and repair29. In contrast, eicosapentaenoic acid and clupanodonic acid were upregulated during the transition from PND46 to PND90 (Fig. S5C), indicating the promotion of anti-inflammatory processes and modulation of the immune response30.

Adipocyte changes across developmental stages in the stroma

To investigate whether changes in the differential expression of fatty acid metabolism genes and differential fatty acid patterns across developmental stages are reflected in morphological changes in the adipocytes present in the stromal tissue, we compared the distribution of adipocytes in terms of number and size within the tissue. During the transition between PND21 to PND46, the number of adipocytes increased, but they were smaller in size (Fig. 6A). In contrast, during the transition between PND46 and PND90, the number of adipocytes was decreased, but they were bigger in size (Fig. 5B). This could indicate a decrease in fatty acid deposits within the adipocytes, resulting in a rise in the number of adipocytes per cm2 but a reduction in the size of each adipocyte compared to the PND21 and PND90 stages.

Adipocyte analysis across developmental stages. (A) Representative image of Masson’s Trichrome stained adipose tissue from PND21, PND46, and PND90 rats and of the analysis of adipocytes using the Adiposoft plugin from ImageJ. Magnification 10x, scale bar 100 μm. (B) Histogram representing the number of adipocytes per cm2 per group and adipocyte size in µm2. Error bars represent SD (*p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001).

Immune response and cellular signaling dynamic across developmental stages

Another interesting finding from the transcriptomic analysis was the cluster demonstrating changes in the molecular mechanisms related to immune response and cellular signaling (Cluster 4, Fig. 2A). To further investigate the immune response, we performed a GSEA that confirmed a strong enrichment in the interferon-alpha response gene set from PND21 to PND46 with a NES of -2.35 (Fig. 7A). However, during the transition from PND46 to PND90, there was no significant variation of this gene set (NES value of -0.82). We then performed an overlap analysis of cluster 4, related to immune response and cellular signaling dynamics, with the upregulated and downregulated genes in the differentially expressed gene analysis. We found that 629 genes upregulated in the transition from PND21 to PND46 were related to cluster 4. These genes included IRF7, involved in the interferon pathway; Tnfrsf11a, Traf1, and Tnfip3 (TNF Alpha-Induced Protein 3), associated with the activation of the NF-κB pathway; Ccl4 (C-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 4) and Ccl21 (C-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 21), chemokines related to immune cell migration and activation; and Lag3 (Lymphocyte Activating 3), Cd53, Cd84, Cd244, and Cd69, which participate in immune cell activation (Fig. 7B). The increases expression levels during this transition were confirmed by RT-qPCR in genes including Tnfrsf11a, Irf7, Traf1, and Cd3e (Fig. S3B).

RNA-seq analyses indicate significant enrichment for immune response. (A) Hallmarks gene sets are shown for an interferon-a response during the transition between PND21 to PND46 and PND46 to PND90. NES; Normalized enrichment score. The red color indicates higher expression in heatmaps, and the blue color indicates lower expression. (B) Venn diagram for overlapping significant genes upregulated, downregulated, and cluster 4 during the transition between PND21 and PND46. (C) Metascape enrichment network visualization of the 629 overlapping genes notably for immune response activation. (D) Gene Ontology enrichment analysis of molecular function for upregulated and downregulated genes during the transition between PND21 and PND46.

These genes were then analyzed using Metascape, which revealed, in the enrichment pathways analysis, that processes such as lymphocyte activation, B cell activation, regulation of leukocyte activation, positive regulation of immune response, adaptive immune response, leukocyte proliferation, among others, were upregulated (Fig. 7C). Additionally, in the differential gene expression analysis, GO analysis showed that molecular functions related to amide, antigen, peptide binding, and immune receptor activity were upregulated (Fig. 7D). In addition, we performed a GSEA M8 - cell type signature gene analysis, which predicts the enrichment of specific cell types. These results confirmed a strong enrichment of immune cell gene signatures, such as those linked to CD4-positive T-cells, monocytes, dendritic cells, natural killer cells, and B cells in PND46 compared to PND21 (Fig. S6A). In PND90, cell types such as antigen-presenting cells, stromal cells, CD4 T-cells, and B cells were enriched as well, maintaining the immune response between PND46 and PND90 (Fig. S6B). These results indicated that the transition from pre-pubertal to peri-pubertal stages is characterized by alterations in transcriptional signatures associated with the aforementioned biological functions.

Discussion

The development of the mammary gland has been extensively studied in various animal models, mainly focusing on epithelial tissue development, ductal branching elongation, and TEB formation13. Both animal and human mammary gland development follow the same sequence of events. After birth, the mammary gland experiences successive transitional stages: pre-puberty, peri-puberty, adulthood, pregnancy, lactation, post-lactational involution, and natural involution (menopause). In this study, we measured the gene expression of rat mammary glands across three development stages and its relationship with epithelial development, the lipidomic profile, and changes in mammary adipocytes. To our knowledge, the combination of transcriptomic and lipidomic profiling during mammary gland development has not been reported. Although one of the limitations of our study is the fact that whole tissue homogenates were used, thus encompassing both epithelial and stromal tissues, transcriptomic signatures suggested that important modifications were happening in the stroma.

After birth, mammary gland development remains relatively quiescent, growing at the same pace as the body, until the onset of peri-puberty31. During the transition from pre-puberty to peri-puberty, there is an increase in ovarian hormones such as estrogen and progesterone, as well as pituitary hormones like growth factor, which together trigger cellular proliferation, matrix remodeling, and the development of proliferative structures known as TEBs13. Our RNA-seq analysis revealed that during the transition between pre-puberty to peri-puberty, the gene expression patterns showed that higher expression of genes in cluster 1 was related to ECM organization, growth factor response, enzyme-linked receptor proteins signaling, and vasculature development. Using whole gland homogenates, we showed downregulation of ECM-related genes, including Col12a1, Col5a3, Lum, Dpt, Eln, Plin1, Cd44, Fab, and Itgb1bp2 during the transition between pre-puberty to peri-puberty. These findings are consistent with a reduction in stromal cells from 55 to 18% during the transition between young and aged mammary glands18. Interestingly, Li et al. have demonstrated through single-cell RNA-seq that myoepithelial and luminal cells from aged mice (13–14 months old) exhibited lower expression of ECM genes such as Dcn, Col4a1, Col4a2, Serpinh1, Sparc, Emid1, Dag, and Spon2 compared to younger glands (3–4 months old), while stromal cells in aged glands showed higher ECM gene expression18. This suggest that expression of ECM genes is not restricted to the stroma, but that can also fluctuate within epithelial cells throughout development. While the changes in ECM-related observed in our study could be explained by the proportional changes in epithelial and stromal cells during development, with the growing epithelium within the stroma leading to an overall decrease in ECM gene expression and ductal branching formation32, it cannot be excluded that it also reflect a change in transcriptional regulation in epithelial cells. Further studies are needed to verify this hypothesis.

During puberty, rats typically reach their maximum TEB count between days 21 and 28 33. From days 21 to 84, alveolar buds show a notable increase due to the action of estrogen and progesterone and their influence on transcriptional factors and signaling pathways mentioned before2. The epithelial proliferation will continue until the ducts reach the edge of the fat pad, leading to changes in the stromal tissue4. The cellular proliferation of epithelial cells is mediated by the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase and phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K)-Akt pathways, which are activated by fibroblast growth factors and their receptors2,34. In our analysis, adult mammary glands showed higher expression of genes related to hormonal regulation and stress responses, particularly those involved in growth factor signaling (Fgf2, Fgf7, Igf2bp2, Igf2, Ghr, and Fgfrl1), epithelial cell regulation and differentiation (Gata3, Traf1, Elf3, Ovol2, Gadd45b, and Sox9), reproductive structure development (Pgr, Areg, and Socs3), and cell morphogenesis (Gata3, Sox9, and Ovol2). These results underscore the critical role of hormonal regulation in mammary gland development, especially in response to steroid hormones that support epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in epithelial cells35. In rodents, growth hormone acts directly on adipocytes, upregulating the transcription of insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF−1), which in turn stimulates epithelial cell proliferation, resulting in ductal elongation and TEB formation36. In parallel, the interaction between IGF-1 and the RhoGTPase activating (Rho-GAP) family and insulin receptor substrate-1/2 (IRS) allows for EMT37. This active proliferation requires energy and building materials. In rodents, the fat pad is mainly composed of adipocytes and immune cells, which are known to have endocrine and secretion functions10. Our study found that adipocyte size decreased from pre-puberty to peri-puberty but increased as the gland transitioned to adulthood, supporting the premise that epithelial proliferation is linked with a high demand for lipids during the phase of ductal elongation, followed by the accumulation of lipids within adipocytes once the growth of the epithelium stabilizes.

Many results from our study could be attributed to metabolic regulation influenced by differential gene expression at each developmental stage. Cluster 2 genes, which were enriched for processes such as oxidative phosphorylation Ndufc1, Ndufb6, and Uqcrb), cell cycle (Cdk1, Cenpf, and Bub1), acyl-CoA metabolic process (Acaca, Acss2, and Acsl1), pyruvate metabolism, and the TCA cycle (Pdk1, Pck1, Mdh1, Pdhb, and Acly), showed higher expression in the pre-puberty mammary gland. Additionally, 662 genes were downregulated during the transition from pre-puberty to peri-puberty, including those involved in the PPAR signaling pathway (Pparg, Scd, Acaca, Dgat1, Acsl1, and Dgat2), fatty acid metabolism (Scd, Fasn, Acaca, Acsl1, Acsm2, and Gpam), lipid transport and metabolism (Apoc3, Cav1, Lep, Lpl, Apoa1, and Fabp4), and triglyceride biosynthesis (Dgat1, Dgat2, Gpam, and Cidea). Those changes in expression are consistent with findings by Fan et al., who used single-cell RNA-seq to identify key genes regulating lipid metabolism (Zfp36l1, Foxo1, Lpin1, Lpl, and Abca1) in adipocytes across five mammary gland developmental stages12.

Metabolic regulation is vital during mammary development, as cells require energy and metabolic precursors to proliferate and differentiate. Suburu et al. found that FASN knockout mice exhibited a significant decrease in total fatty acid concentration, particularly in myristic acid (C14:0), myristoleic acid (C14:1), palmitic acid (C16:0), stearic acid (C18:0), and linoleic acid (C18:2)26. Similarly, in our study, FASN was downregulated from pre-puberty to puberty, and a similar decrease was observed in total fatty acid concentration, as well as in those specific fatty acids. Conversely, increasing the expression of PPARα-regulated genes led to a rise in total fatty acids like C16:0, C16:1, and C18:1 in female Fatp2−/− mice38. PPAR signaling was decreased from pre-puberty to puberty, but only oleic acid levels were affected, suggesting a more complex regulation. However, globally, these findings indicated that there is a significant downregulation of genes involved in lipid synthesis and metabolic processes during the transition from pre-puberty to peri-puberty.

In our lipidomic analysis, we observed a notable decrease in total fatty acid concentration during the transition from pre-puberty to peri-puberty, likely due to the downregulation of lipid metabolism genes such as Fasn. The data is consistent with the regulation of Acaca, Fasn, and Scd expression changes during pregnancy, lactation, and involution periods, correlating with fatty acid contents (C14:1, C18:2, gamma-linolenic acid (C18.3), and arachidonic acid (20:4))39. Additionally, our lipidomic analysis revealed significant differences in 29 out of 43 quantified fatty acids between pre-puberty and peri-puberty. Notably, there was a decrease in saturated fatty acids and omega-6/omega-3 concentrations, which are essential for cell membrane integrity and signaling40. Stabilizing lipid profiles from peri-puberty to adulthood suggests a metabolic balance once development is complete. These findings correlate with studies showing that C16:0, C16:1, C18:0, and C18:1 fatty acids become more homogeneous during adipocyte differentiation. However, at the onset of adipogenesis, there is an increase in lauric acid (C12:0) and a decrease in long-chain fatty acids such as behenic acid (C22:0), erucic acid (C22:1), and docosadienoic acid (C22:2)41. Our findings highlight the dynamic changes in lipid metabolism during mammary gland development, emphasizing the critical role of adipocytes in tissue remodeling and homeostasis. The observed shifts in fatty acid profiles and adipocyte morphology underscore the intricate balance between lipid synthesis, redistribution, and epithelial expansion necessary for proper mammary gland maturation.

The mammary fat pad is home to a complex immune microenvironment, which plays a critical role in tissue development and remodeling. Our analysis identified that cluster 4, representing a specific gene expression pattern, was notably enriched for genes associated with leukocyte activation (Socs3, Faslg, Tlr9, and Cd69) and cytokines (Ccl4 and Cxcr5). In our study, the upregulation of genes involved in lymphocyte activation and adaptive immune responses (Socs3, Irf7, Traf1, Tnfrsf11a, Sigirr, Tnfaip3, Bcl2l14, Btk, Cd244, Ctla4, and Icoslg) underscores the critical role of immune signaling in mammary tissue remodeling. Previous studies have highlighted the importance of cytokines and genes involved in their signaling, such as IL4, IL13, IL5, and Stat6, produced by Th2 cells, in promoting luminal epithelial cell differentiation and maturation42.

Our data also reveal increased expression of genes associated with various immune cells, including T-cells (Cd3e, Tnfrs18, Cd8a, Cd8b, Foxp3), NK cells (Klrd1 [CD94], Klrc1), and B-cells (Cd19, Pax5, Cd79a, Cd79b). It has been demonstrated that the presence of macrophages, derived from circulating monocytes, is crucial in shaping mammary immunity and plays a significant role in the transition from puberty to adulthood43. Factors such as colony-stimulating factor-1 (CSF-1, known as macrophage colony-stimulating factor – M-CSF) and its receptor influence macrophage activity44. Lin et al. demonstrated that a lack of macrophages in TEBs leads to altered TEB morphology and poor collagen degradation in CSF-1 null mutant mice45,46. In our analysis, we found an increased expression of genes associated with the presence of macrophages in the transition between pre-puberty to peri-puberty as a (Itgam [CD11B], Fcer2 [CD23], Csf1r)7,44, dendritic cells (Cd74, Tnfrsf14 [HVEM]), and myeloid cells (Cd14, Csf3r)15,17. Similarly, in aged mammary glands, a decrease in myeloid cells coupled with an expansion of lymphoid cells was noted, reflecting age-related immune changes44,47. Key immune cells involved in mammary gland development include macrophages, which assist in matrix reorganization and ductal elongation; mast cells, which are crucial for local immune responses; and eosinophils, which contribute to the remodeling of the ECM44,47. Additionally, deficits in mast cells have been shown to alter TEB numbers at various postnatal weeks, supporting the roles of mast cells in mammary tissue restructuring, maintenance, and repair47,48,49. The significant enrichment of immune response genes during the transition from pre-puberty to peri-puberty highlights the essential role of immune signaling in mammary gland remodeling and development. The complex interplay between cytokines, immune cells, and regulatory genes underscores the intricate balance of immune processes necessary for effective mammary tissue maturation and development during critical transitional periods.

In conclusion, this study provides a comprehensive view of the morphological, transcriptional, and metabolic changes in the mammary gland during pre-puberty, peri-puberty, and adulthood. The results highlight the complexity of mammary development and underscore the importance of metabolic and proliferative regulation, cellular signaling, and immune response in these processes. The integration of morphological, transcriptional, and lipidomic analyses offers a robust platform for future research to understand the underlying mechanisms of mammary development, which may also have implications for studying diseases related to the mammary gland, such as breast cancer.

Materials and methods

Animals

All experiments involving rats were performed following the guidelines set out by the Canadian Council of Animal Care (CCAC) and the ARRIVE guideline. This research was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the INRS (Protocols 2202-02). Nulliparous female Sprague-Dawley rats were kindly donated by Geraldine Delbès50. Rats were weighed and euthanized by CO2 followed by cervical dislocation at different time points: pre-puberty (PND21), peri-puberty (PND46), and adulthood (PND90). For each time point, between 5 and 7 animals were sacrificed, and two pairs of mammary glands (thoracic and inguinal) were taken and weighed.

Whole-mount staining and analysis

Sample preparation

The right inguinal mammary gland was processed as described previously51,52. Briefly, it was dissected, placed on glass slides, and fixed in Carnoy`s solution (6:3:1 of 100% ethanol, chloroform, and glacial acetic acid) overnight at room temperature (RT). Samples were rehydrated again through serial ethanol gradient from 70 to 0% in water and stained in carmine alum (2% carmine, 5% potassium aluminum sulfate in water) overnight at RT. Samples were dehydrated through serial ethanol baths and cleared in xylene. Finally, samples were mounted with Permount (FisherChemical, Ontario, Canada, no. SP15-500). Images were captured using a Canon PowerShot G9x digital camera on a transilluminator (Henning Graphics LR299343), and a measurement scale was used to compare sample sizes.

Epithelial area and branching complexity measurement

The epithelial area analysis was quantified for all animals (n = 5–7) using whole-mount. The scale was set for all images, and the area was measured in cm2 and analyzed using the skeletonize tool of ImageJ software (https://imagej.net/Fiji/Downloads). The skeletonized image was used for the branching complexity, and between 3 and 5 representative sections were taken. The number of intersections (N) per cm2 was analyzed using the Sholl analysis plugin from ImageJ53,54.

RNA extraction

Four randomly chosen samples per group were used to extract the RNA using the Aurum total RNA fatty and fibrous tissue kit (Bio-Rad, Ontario, Canada, no. 7326830) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (between 50 and 100 mg of the left inguinal mammary gland for each animal). RNA integrity number (RIN) was verified using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer instrument and the Agilent RNA 6000 Nano Kit; all samples showed RIN > 8 and could thus be used for sequencing analysis. RNA concentration and purity were measured using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific). Extracted RNA samples were sent for RNA sequencing to the Genomic Centre of the Centre de recherche du CHU de Québec – Université Laval for RNA-seq analysis using a HiSeq 2500 (125 bp paired-end sequencing), as previously described55.

Sequencing data analyses

The raw sequencing data quality was checked using FastQC v0.12.0 before being trimmed using TrimGalore v0.6.10. The quality was then reverified with FastQC and aggregated with MultiQC v1.2. The trimmed RNA sequences with high-quality reads were aligned to the Rattus norvegicus Rnor_6.0 reference transcriptome (https://may2021.archive.ensembl.org/Rattus_norvegicus) using Kallisto v0.46.1 pseudo-aligner, sequencing data were deposited in NCBI under the accession number PRJNA1157723.

The differential gene expression analysis was performed using the R-Package DESeq2 v1.42.1. To determine each group’s molecular signatures and the average gene expression, k-means for gene clustering algorithms were used. To determine differentially expressed genes, a threshold of Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rates (FDR) p-adj < 0.05 and absolute log2FC (fold change) 1.5 was used. To study the biological pathways regulated in the transition between developmental groups, Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) was used. Gene analyses were conducted using Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment tools20,21,22, facilitated by the SRplot package (http://www.bioinformatics.com.cn) and R software environment. To identify biological pathways enriched in gene clusters and visualize the similarities of enriched terms, we used Metascape (https://metascape.org/) and Enrichr (https://maayanlab.cloud/Enrichr/).

Gene expression analysis by RT-qPCR

After purification, RNA was used to synthesized cDNA. To this end, the reverse transcription reaction was performed using the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Biorad, no. 1708891, CA, USA) following the manufacturer´s protocol. Then, qPCR analyses were performed on a CFX96 Touch Real-Time PCR Detection System. Oligonucleotide primers (Cd3e, Traf1, Irf7, and Tnfrsf11a) were designed using Primer Blast (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast/; last accessed Jan 13, 2025), and Scd, Fabp4, Pparγ, Actb, Rpl13a, G6pd, Gapdh, Eef1a1, and Hprt primers were validated in a previous study52. qPCR assays were performed with the SsoAdvanced SYBR green Supermix (Biorad, no. 1725274), and results were analyzed using the CFX Maestro Sofware (Biorad). The efficiency and the specificity of each qPCR reaction were done for each pair of primers by the standard curve and dissociation curves analysis of the PCR products, respectively56,57. We used 6 reference genes, and Actb, Rpl13a, and Eef1a1 were selected based on their stability throughout the developmental stages using the geNorm algorithm58. Amplification curves were next analyzed using the comparative cycle threshold method (ΔΔCt method).

Cryosection and Masson’s trichrome analysis

For each animal, the right thoracic mammary glands were dissected and immediately embedded in cyromatrix (OCT Cryomatrix, Fisher Scientific, Cat. 23-730-571) on dry ice and stored at -80ºC. Frozen tissues were cut using a cryostat into 5 μm sections, fixed in 10% formalin overnight at RT, and stained using Masson Trichrome. Briefly, sections were immersed in Weigert’s iron hematoxylin for 10 min, Biebrich scarlet-acid fuchsin for 15 min, phosphomolybdic-phosphotungstic acid for 20 min, and aniline blue for 5 min, washing with water after each step. Finally, the samples were immersed in 1% acetic acid for 5 min. The sections were then dehydrated by immersion in 95% and 100% ethanol for 5 min each and cleared in xylene for 5 min. Samples were mounted using coverslips and Permount. Images were captured using a confocal microscope Nikon A1R + equipped with a digital camera (Nikon) and analyzed using ImageJ. The area of the adipocyte with an intact structure was measured using the drawing tool; for each image, the complete adipose tissue was measured, and the number of adipocytes and area was determined using the plugins from ImageJ called Adiposoft59.

Lipids quantification

A lipidomic profile was performed from snap-frozen thoracic mammary glands. After being crushed in liquid nitrogen on dry ice and weighted, the samples were homogenized in saline 9%. Then, homogenates were spiked with the internal standard phosphatidylcholine C21:0 (Sigma Aldrich), and the lipids were extracted with chloroform\methanol solution (2:1 v/v) according to a modified Folch method60. After centrifugation, the lipid phases were collected and dried under a nitrogen flow. All the samples were resuspended in 2 ml of methanol/benzene (4:1 v/v) and methylated with acetyl chloride61. The fatty acids profile was realized by capillary gas chromatography using a temperature gradient on an HP5890 gas chromatograph (Hewlett Packard, Toronto, Canada) equipped with an HP-88 capillary column (100 m x 0.25 mm i.d. x 0.20 μm film thickness; Agilent Technologies) coupled with a flame ionization detector (FID). Helium was used as carrier gas (split ratio 1:50).

Fatty acids were identified according to their retention time, using the following standard mixtures as a basis for absolute quantification: the FAME 37 mix (Supelco Inc., Bellefonte, PA), the GLC-411 fatty acid mix (NuChek Prep Inc, Elysian, MN), the methylated fatty acids C22:5 w6 (Larodan AB, Malmö, Sweden), the methylated fatty acids C22:5 w3 (Supelco Inc., Bellefonte, PA), a mixture of trans-FA containing: C18:2 w6 cis/trans (Supelco Inc Bellefonte, PA), a mixture of cis/trans C18:3 w3 (Supelco Inc Bellefonte, PA), and the following Nucheck fatty acids: C14:1 trans-9, C16:1 trans-9, and finally isoforms of C18:1 (cis-6, trans-6, cis-11, trans-11: Nucheck, and cis-12, cis-13: Supelco Inc.). Results were expressed as percent of total fatty acids and mgFA/g of mammary gland tissues.

Bioinformatic and statistical analysis

All the statistical analyses were done using GraphPad Prism 9 and the R-Studio environment. Descriptive analysis of the data, such as mean, median, and standard deviation, was performed. The normality of the distribution was verified using Shapiro-Wills or Kolmogorov-Smirnov normality test. Data that satisfied assumptions of normality and homoscedasticity were analyzed using Anova and student’s t-test. Otherwise, Kruskal-Wallis and Mann-Whitney U-test non-parametric tests were used. Pearson’s correlation was used to measure the degree of relationship between variables. For the differential gene expression, p-adj < 0.05, and changes of Log2 fold of 1.5 were considered significant. For other analyses, p-value < 0.05 was considered as a significant difference.

Visualization techniques such as volcano plots, complex heatmaps, principal component analysis (PCA), boxplots, bar plots, and Dot plots were performed using an R environment. Venn diagrams were generated with the jvenn tool (available; https://jvenn.toulouse.inrae.fr/app/index.html).

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary materials. Raw data that support the findings have been deposited in Sequenced Read Archive (SRA) under accession number PRJNA1157723. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=PRJNA1157723.

References

Musumeci, G. et al. Mammary gland: From embryogenesis to adult life. Acta Histochem. 117, 379–385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acthis.2015.02.013 (2015).

Biswas, S. K., Banerjee, S., Baker, G. W., Kuo, C. Y. & Chowdhury, I. The mammary gland: Basic structure and molecular signaling during development. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 3883 (2022).

Hitchcock, J., Hughes, K., Harris, O. & Watson, C. Dynamic architectural interplay between leucocytes and mammary epithelial cells. FEBS J. 287, 250–266 (2020).

Inman, J. L., Robertson, C., Mott, J. D. & Bissell, M. J. Mammary gland development: Cell fate specification, stem cells and the microenvironment. Development 142, 1028–1042. https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.087643 (2015).

Dziegelewska-Sokolowska, Z., Majewska, A., Prostek, A. & Gajewska, M. Adipocyte-Derived paracrine factors regulate the in vitro development of bovine mammary epithelial cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms241713348 (2023).

Li, S. et al. Immunocytochemical localization of sex steroid hormone receptors in normal human mammary gland. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 58, 509–515. https://doi.org/10.1369/jhc.2009.954644 (2010).

Henry, S. et al. Characterization of gene expression signatures for the identification of cellular heterogeneity in the developing mammary gland. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia. 26, 43–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10911-021-09486-3 (2021).

Colleluori, G., Perugini, J., Barbatelli, G. & Cinti, S. Mammary gland adipocytes in lactation cycle, obesity and breast cancer. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 22, 241–255. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11154-021-09633-5 (2021).

Wang, Q. A. et al. Reversible De-differentiation of Mature White Adipocytes into Preadipocyte-like Precursors during Lactation. Cell Metab. 28, 282–288 e283 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2018.05.022

Hovey, R. C. & Aimo, L. Diverse and active roles for adipocytes during mammary gland growth and function. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia 15, 279–290 (2010).

Ganeshalingam, M. et al. Role of lipidomics in assessing the functional lipid composition in breast milk. Front. Nutr. 9, 899401. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2022.899401 (2022).

Fan, Y. et al. A cell transcriptomic profile provides insights into adipocytes of Porcine mammary gland across development. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 14, 126. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40104-023-00926-0 (2023).

Geiger, A. J. & Hovey, R. C. Development of the mammary glands and its regulation: How not all species are equal. Anim. Front. 13, 51–61. https://doi.org/10.1093/af/vfad029 (2023).

Dos Santos, C. O. et al. Molecular hierarchy of mammary differentiation yields refined markers of mammary stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 7123–7130. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1303919110 (2013).

Bach, K. et al. Differentiation dynamics of mammary epithelial cells revealed by single-cell RNA sequencing. Nat. Commun. 8, 2128. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-02001-5 (2017).

Wu, S. Z. et al. Stromal cell diversity associated with immune evasion in human triple-negative breast cancer. EMBO J. 39, e104063. https://doi.org/10.15252/embj.2019104063 (2020).

Pal, B. et al. Construction of developmental lineage relationships in the mouse mammary gland by single-cell RNA profiling. Nat. Commun. 8, 1627. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-01560-x (2017).

Li, C. M. et al. Aging-Associated alterations in mammary epithelia and stroma revealed by single-cell RNA sequencing. Cell. Rep. 33, 108566. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108566 (2020).

Doria, M. L. et al. Fatty acid and phospholipid biosynthetic pathways are regulated throughout mammary epithelial cell differentiation and correlate to breast cancer survival. FASEB J. 28, 4247–4264. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.14-249672 (2014).

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Matsuura, Y. & Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG: Biological systems database as a model of the real world. Nucleic Acids Res. 53, D672–D677 (2025).

Kanehisa, M. Toward understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Protein Sci. 28, 1947–1951 (2019).

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 27–30 (2000).

Aguilar-Recarte, D. et al. GDF15 mediates the metabolic effects of PPARbeta/delta by activating AMPK. Cell. Rep. 36, 109501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109501 (2021).

Avagliano, A. et al. Influence of fibroblasts on mammary gland development, breast cancer microenvironment remodeling, and cancer cell dissemination. Cancers (Basel). 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12061697 (2020).

Zhu, J. & Thompson, C. B. Metabolic regulation of cell growth and proliferation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 436–450. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41580-019-0123-5 (2019).

Suburu, J. et al. Fatty acid synthase is required for mammary gland development and milk production during lactation. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 306, E1132–1143. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpendo.00514.2013 (2014).

Furstova, V., Kopska, T., James, R. F. & Kovar, J. Comparison of the effect of individual saturated and unsaturated fatty acids on cell growth and death induction in the human pancreatic beta-cell line NES2Y. Life Sci. 82, 684–691. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2007.12.023 (2008).

Reiss, K., Cornelsen, I., Husmann, M., Gimpl, G. & Bhakdi, S. Unsaturated fatty acids drive disintegrin and metalloproteinase (ADAM)-dependent cell adhesion, proliferation, and migration by modulating membrane fluidity. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 26931–26942. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M111.243485 (2011).

Samovski, D. & Jacome-Sosa, M. Fatty acid transport and signaling: Mechanisms and physiological implications. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 85, 317–337. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-physiol-032122-030352 (2023).

Augimeri, G. et al. A conjugate of dopamine and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), exerts Anti-inflammatory properties in mouse and human macrophages. Nutrients 11, 2247. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11092247 (2019). N-Eicosapentaenoyl Dopamine.

Nerger, B. A. & Nelson, C. M. 3D culture models for studying branching morphogenesis in the mammary gland and mammalian lung. Biomaterials 198, 135–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.08.043 (2019).

Hassiotou, F. & Geddes, D. Anatomy of the human mammary gland: Current status of knowledge. Clin. Anat. 26, 29–48. https://doi.org/10.1002/ca.22165 (2013).

Peters, A., Ingman, W., Tilley, W. D. & Butler, L. Differential effects of exogenous androgen and an androgen receptor antagonist in the peri-and postpubertal murine mammary gland. Endocrinology 152, 3728–3737 (2011).

Martin, F., Stein, T. & Howlin, J. Mammary gland development. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Dev. Biology. 1501, 358. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-6475-8 (2017).

Hannan, F. M., Elajnaf, T., Vandenberg, L. N., Kennedy, S. H. & Thakker, R. V. Hormonal regulation of mammary gland development and lactation. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 19, 46–61. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41574-022-00742-y (2023).

Kleinberg, D. L., Ruan, W. & IGF-I GH, and sex steroid effects in normal mammary gland development. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia. 13, 353–360. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10911-008-9103-7 (2008).

Heckman, B. M. et al. Crosstalk between the p190-B RhoGAP and IGF signaling pathways is required for embryonic mammary bud development. Dev. Biol. 309, 137–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.07.002 (2007).

Perez, V. M. et al. Deletion of fatty acid transport protein 2 (FATP2) in the mouse liver changes the metabolic landscape by increasing the expression of PPARalpha-regulated genes. J. Biol. Chem. 295, 5737–5750. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.RA120.012730 (2020).

Kęsek-Woźniak, M. et al. ACACA, FASN and SCD gene expression in somatic cells throughout lactation and its relation to fatty acid profile in cow milk. Anim. Sci. Pap Rep. 41, 17–26 (2023).

Mukerjee, S., Saeedan, A. S., Ansari, M. N. & Singh, M. Polyunsaturated fatty acids mediated regulation of membrane biochemistry and tumor cell membrane integrity. Membr. (Basel) 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes11070479 (2021).

Miehle, F. et al. Lipidomic phenotyping reveals extensive lipid remodeling during adipogenesis in human adipocytes. Metabolites 10 https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo10060217 (2020).

Khaled, W. T. et al. The IL-4/IL-13/Stat6 signalling pathway promotes luminal mammary epithelial cell development. Development 134, 2739–2750. https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.003194 (2007).

Mosser, D. M. & Edwards, J. P. Exploring the full spectrum of macrophage activation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 8, 958–969 (2008).

Beaudry, K. L., Parsons, C. L., Ellis, S. E. & Akers, R. M. Localization and quantitation of macrophages, mast cells, and eosinophils in the developing bovine mammary gland. J. Dairy. Sci. 99, 796–804. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2015-9972 (2016).

Sternlicht, M. D. Key stages in mammary gland development: The cues that regulate ductal branching morphogenesis. Breast Cancer Res. 8, 1–11 (2005).

Lin, E. Y., Gouon-Evans, V., Nguyen, A. V. & Pollard, J. W. The macrophage growth factor CSF-1 in mammary gland development and tumor progression. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia 7, 147–162. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1020399802795 (2002).

Need, E. F., Atashgaran, V., Ingman, W. V. & Dasari, P. Hormonal regulation of the immune microenvironment in the mammary gland. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia 19, 229–239. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10911-014-9324-x (2014).

Lilla, J. N. & Werb, Z. Mast cells contribute to the stromal microenvironment in mammary gland branching morphogenesis. Dev. Biol. 337, 124–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.10.021 (2010).

Aupperlee, M. D. et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling is a key mediator of Hormone-Induced leukocyte infiltration in the pubertal female mammary gland. Endocrinology 155, 2301–2313. https://doi.org/10.1210/en.2013-1933 (2014).

Lecante, L. L., Gaye, B. & Delbes, G. Impact of in utero rat exposure to 17Alpha-Ethinylestradiol or genistein on testicular development and germ cell gene expression. Front. Toxicol. 4, 893050. https://doi.org/10.3389/ftox.2022.893050 (2022).

Gouesse, R. J. et al. Gestational and lactational exposure to an environmentally relevant mixture of brominated flame retardants downregulates junctional proteins, thyroid hormone receptor alpha1 expression, and the Proliferation-Apoptosis balance in mammary glands post puberty. Toxicol. Sci. 171, 13–31. https://doi.org/10.1093/toxsci/kfz147 (2019).

Crobeddu, B. et al. Gestational and lactational exposure to the emergent alternative plasticizer 1,2-Cyclohexane Dicarboxylic acid diisononyl ester (DINCH) impairs lipid metabolism to a greater extent than the commonly used Di(2-Ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) in the adult rat mammary gland. Toxicol. Sci. 189, 268–286. https://doi.org/10.1093/toxsci/kfac076 (2022).

Stanko, J. P., Easterling, M. R. & Fenton, S. E. Application of Sholl analysis to quantify changes in growth and development in rat mammary gland whole mounts. Reprod. Toxicol. 54, 129–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reprotox.2014.11.004 (2015).

Stanko, J. P. & Fenton, S. E. Quantifying branching density in rat mammary gland Whole-mounts using the Sholl analysis method. J. Vis. Exp. 124, e55789. https://doi.org/10.3791/55789 (2017).

Germain, L. et al. Alternative splicing regulation by the androgen receptor in prostate cancer cells. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 202, 105710. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsbmb.2020.105710 (2020).

Taylor, S. C. et al. The ultimate qPCR experiment: Producing publication quality, reproducible data the first time. Trends Biotechnol. 37, 761–774. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibtech.2018.12.002 (2019).

Taylor, S. C. & Mrkusich, E. M. The state of RT-quantitative PCR: Firsthand observations of implementation of minimum information for the publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments (MIQE). J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 24, 46–52. https://doi.org/10.1159/000356189 (2014).

Vandesompele, J. et al. Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol. 3, RESEARCH0034. https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2002-3-7-research0034 (2002).

Galarraga, M. et al. Adiposoft: Automated software for the analysis of white adipose tissue cellularity in histological sections. J. Lipid Res. 53, 2791–2796. https://doi.org/10.1194/jlr.D023788 (2012).

Shaikh, N. A. & Downar, E. Time course of changes in Porcine myocardial phospholipid levels during ischemia. A reassessment of the lysolipid hypothesis. Circ. Res. 49, 316–325. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.res.49.2.316 (1981).

Lepage, G. & Roy, C. C. Direct transesterification of all classes of lipids in a one-step reaction. J. Lipid Res. 27, 114–120 (1986).

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to Fabien Joao and Rhizlane ElOmri for their technical support.

Funding

This work was supported by funding to IP, MP, and EAW from the National Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC; RGPIN-2020-05726, RGPIN-2023-0523 and RGPIN-2019-04740, respectively). DT is supported by scholarships from the Réseau Québecois en reproduction and Fondation Armand-Frappier.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.T.P., Conceptualization, methodology, software, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing - original draft, writing - review & editing, and visualization. A.M., Conceptualization, methodology, investigation. M.J., Conceptualization and methodology. J.C., Conceptualization and methodology. M.S.S., software and formal analysis. L.B., Methodology. G.D. Conceptualization and methodology. M.P., Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, supervision, project administration, and funding acquisition. E.A.W., Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, supervision, project administration, and funding acquisition. I.P., Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, supervision, project administration, and funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tovar-Parra, D., McDermott, A., Juarez, M.N. et al. The rat mammary gland undergoes dynamic transcriptomic and lipidomic modifications from pre-puberty to adulthood. Sci Rep 15, 12222 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97532-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97532-z