Abstract

Superb microvascular flow signals in joints are important indicators for evaluating inflammation in arthritis diagnosis. Super Microvascular Imaging (SMI), a musculoskeletal ultrasound technique, captures microvascular signals with enhanced resolution, enabling improved quantitative analysis of joint superb microvascular flow. However, existing musculoskeletal ultrasound imaging predominantly relies on static observations for analyzing these signals, which are heavily influenced by subjective factors, thereby limiting diagnostic accuracy for arthritis. This study introduces a novel quantitative and automated grading method utilizing dynamic analysis through an optical flow model. Real-time dynamic quantification of superb microvascular flow signals is achieved via motion estimation and skeleton extraction based on the optical flow model. The Kappa consistency test evaluates the agreement between the automated grading system and physician assessments, with differences between the two methods analyzed. A total of 47 patient samples were included, comprising 20 males and 27 females (p = 0.307 > 0.05, χ2=1.042). The agreement between the automated grading system and physician assessments reached 70.2%, with a Kappa value of 0.627 (p < 0.001), indicating good consistency. Nonetheless, the system displayed a tendency to high-grade cases of moderate inflammation. The proposed quantitative and automated grading method for superb microvascular flow, based on dynamic analysis through an optical flow model, improves the objectivity and consistency of superb microvascular flow grading and demonstrates significant clinical potential. The method shows strong anti-interference performance in noisy signal environments, representing a promising advancement for non-invasive arthritis diagnosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Superb Microvascular Imaging (SMI), a novel ultrasound imaging technique, enhances tissue motion detection by effectively minimizing image artifacts arising from weak blood flow signals and motion interference. This advancement enables the clear visualization of microvascular flow in ultrasound images1,2. In comparison to traditional blood flow imaging methods such as color Doppler and power Doppler, SMI provides superior detection of low-velocity blood flow with enhanced spatial and temporal resolution, particularly for visualizing blood flow within microvessels3,4. Synovial blood flow signals serve as critical markers for diagnosing joint inflammation, and SMI-based microvascular flow analysis delivers more precise quantitative assessments than traditional methods5. Research has established the superiority of SMI over power Doppler in detecting low-grade synovial inflammation, with significant correlations observed between SMI findings, radiographic features, and MRI findings6,7. This capability has proven particularly valuable in diagnosing rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, and other inflammatory arthropathies, where SMI demonstrates high clinical value8,9.

Despite these advancements, challenges persist in the application of traditional microvascular imaging techniques, especially in quantitative analysis and automated grading of blood flow signals. Current quantification methods frequently utilize semi-quantitative grading systems, such as the Szkudlarek semi-quantitative grading system10. This approach classifies microvascular flow signals into grades 0 to 3, predominantly based on subjective assessments by physicians, introducing variability and reducing consistency and reproducibility in the results11,12. Additionally, the dynamic variations in joint microvascular flow, often influenced by arterial and venous pulsations, are challenging to capture through static image analysis, potentially compromising the accuracy of flow quantification13,14.

To address these limitations, dynamic blood flow quantification methods utilizing motion estimation and optical flow analysis have gained significant attention in recent years. Optical flow models, which are motion estimation techniques based on image sequences, effectively capture temporal changes in blood flow over time15,16. By calculating the optical flow field within images, these methods extract motion information from blood flow, enabling real-time dynamic quantification of microvascular flow signals17,18. Optical flow analysis enhances flow quantification accuracy and mitigates noise and artifact interference, particularly in low signal-to-noise ratio conditions, demonstrating excellent anti-interference capabilities19,20. While machine learning and deep learning techniques have made strides in automated grading of osteoarthritis by integrating ultrasound imaging features with clinical data21,22, traditional optical flow models remain indispensable for motion estimation and dynamic blood flow analysis23. These models provide precise measurements of microvascular flow dynamics and generate quantitative indicators crucial for inflammation grading. Additionally, metrics such as elasticity and motion, derived from optical flow analysis, remain underexplored in current research24,25. Compared to machine learning approaches, traditional optical flow models exhibit significant advantages in noise suppression, processing efficiency, stability, and real-time performance, making them particularly suitable for clinical settings26,27.

This study proposes a dynamic analysis method that integrates optical flow models for estimating optical flow fields, quantifying motion, and extracting skeleton structures from microvascular flow signals. The method facilitates real-time tracking of dynamic blood flow changes and automated grading. By comparing with expert ratings and validating the consistency between the automated grading system and manual assessments using the Kappa statistic, the proposed method demonstrates high agreement28,29. Furthermore, the dynamic analysis based on optical flow enhances the precision of blood flow quantification and reduces operator and reviewer subjectivity, offering a reliable and objective tool for the non-invasive diagnosis of osteoarthritis and other joint inflammatory diseases30,31.

Data and methods

Data collection

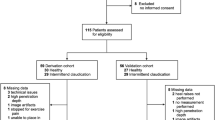

Ultrasound microvascular imaging data were collected from patients with joint pain who attended the hospital between June and September 2024. Inclusion criteria included patients who experienced joint pain for at least one day within the preceding month and exhibited visible blood flow signals under ultrasound microvascular imaging mode. Patients with a history of joint replacement surgery were excluded from the study. A total of 47 patients were included, comprising 20 males and 27 females.

The Canon Aplio i800, a high-resolution ultrasound imaging system, was employed for this study due to its advanced real-time dynamic imaging capabilities, particularly for microvascular and vascular imaging. The SMI technology incorporated in the Canon Aplio i800 enhances the detection of microvascular signals, rendering it highly suitable for assessing arthritis and synovial lesions.

All ultrasound examinations were conducted using the Canon Aplio i800 system with an L15-3WU linear probe operating at a frequency of 15 MHz. Patients were positioned based on the site of pain, either seated or with the affected limb placed on a foam pad to ensure optimal exposure of the examination area. A conventional ultrasound scan of the affected joint was initially performed to observe general characteristics. For patients presenting with multiple lesions, the largest lesion was selected for detailed examination.

When the most vascularized plane of inflammatory blood flow signals was identified using the color Doppler flow imaging mode, the system was switched to the color superb microvascular imaging mode. The settings were configured with a blood flow velocity scale of 3 cm/s, a color frequency of 4 MHz, and a frame rate of 30 Hz. Gain adjustments were performed to achieve optimal imaging quality, and both static images and dynamic videos were recorded.

To enhance the sensitivity of blood flow measurements, the region of interest (ROI) was minimized while ensuring it encompassed the area of interest. All imaging data were stored for subsequent dynamic evaluations of microvascular flow. To maintain consistency in baseline flow measurements during quantification, ROIs with identical areas were selected for analysis throughout the study.

Methods

Overall framework

This study presents a systematic approach based on the dynamic analysis of microvascular flow signals for quantifying and evaluating joint microvascular flow. The proposed framework includes four key components: microvascular morphology extraction, dynamic analysis of microvascular flow, development of blood flow signal evaluation metrics, and clinical validation.

Initially, regions of interest (ROIs) are extracted from preprocessed microvascular imaging sequences to improve signal quality and measurement accuracy. Subsequently, dynamic analysis of microvascular flow within the ROIs is conducted, which includes microvascular flow quantification, optical flow field estimation, and the integration of microvascular morphological features. Based on the outcomes of the dynamic analysis, two primary metrics are introduced and quantified: motion density of microvascular flow and elasticity density of microvascular structures. These metrics serve as essential parameters for evaluating blood flow signals and facilitating automated grading. Finally, the method undergoes clinical validation, and an automated grading system is developed using imaging features. The overall technical framework of the proposed method is depicted in Fig. 1.

Framework of this paper for the quantification and evaluation of joint microvascular flow signals. The framework comprises four key modules: (1) Extraction of microvascular morphology from preprocessed regions of interest (ROIs); (2) Dynamic analysis of microvascular flow, including flow quantification and optical flow field estimation; (3) Construction of evaluation metrics for microvascular motion density and elasticity density; and (4) Clinical validation and development of an automated grading system.

Microvascular morphology extraction

The collected ultrasound microvascular imaging data served as raw input, decoded into image sequences using frame rate recording and preprocessed to ensure sufficient quality for subsequent analysis. The process begins with the original image sequence, which is then subjected to moderate enhancement to improve the quality of the visual features. Subsequently, grayscale thresholds are adjusted to optimize contrast, and finally, the image is binarized to facilitate further analysis (Fig. 2).

Segmentation and clustering optimization techniques were applied to the binarized images to enhance image coherence and accurately represent blood flow features. These techniques effectively removed weak, noise-induced blood flow signals, which might otherwise interfere with the analysis, ensuring that only significant and reliable flow data were retained for further assessment (Fig. 3).

Morphological characteristics of microvascular structures were further refined through the application of edge detection and skeleton extraction methods across consecutive frames, with vessel continuity improved using curve fitting techniques (Fig. 4). This approach facilitates the precise representation of both morphological and dynamic microvascular features, providing a robust foundation for calculating elasticity-related metrics using the optical flow model. The area of boundary detection will be incorporated into the measurements of motion density and elastic density. The direction of the skeleton will be considered in relation to the motion direction.

Blood flow signal segmentation and clustering

The process of blood flow region segmentation and clustering is detailed in Tables 1 and 2. Initially, segmentation of blood flow regions is performed using Algorithm 1, which functions by iteratively analyzing each pixel in the image. Pixels with a value of 1 are identified as targets and added to a queue. The Breadth-First Search (BFS) algorithm is subsequently applied to examine the 8-neighborhood pixels surrounding each target pixel. Neighboring pixels with a value of 1 that have not yet been marked are also added to the queue. This neighborhood segmentation search method is depicted in Fig. 5.

The algorithm continues until the queue is empty, ensuring that all connected pixels are grouped and stored as distinct blood flow regions. This segmentation process is repeated across the entire image until all target pixels are identified and classified into unique blood flow regions. The step-by-step algorithm is detailed in Table 1.

Subsequently, Algorithm 2 is utilized to perform clustering on the segmented blood flow regions which is detailed in Table 2. The algorithm starts by calculating the distance between each pair of regions and evaluates whether adjacent regions meet the criteria for merging, based on a predefined distance threshold. Regions satisfying the distance criterion are merged into a single cluster. This iterative process continues until no additional regions meet the merging criteria, resulting in a final set of clustered blood flow regions prepared for subsequent analysis.

The clustering combination process integrates clustering results from two consecutive frames, as the optical flow method requires sequential image pairs for analysis. This step involves identifying similar regions between the clustered results of the two frames and grouping them into the same cluster, facilitating optical flow computation.

Skeleton extraction

The skeleton extraction algorithm isolates the core structure of the image through edge detection and erosion operations, capturing essential skeleton features suitable for curve fitting. The process begins with initializing the input image I and determining its dimensions m × n. The algorithm iteratively examines each pixel in the image. When a pixel with a value of 1 is detected, a variable sum is initialized to 0. The algorithm then evaluates the 8-neighborhood of the pixel, summing the values of the neighboring pixels. If sum = 8, indicating that the pixel is completely surrounded, the pixel value is set to 0 (erosion). This erosion process is repeated iteratively across the image until only the skeleton structure remains.

The resulting skeleton image I retains the primary morphological features of blood flow, making it suitable for subsequent curve fitting analysis. The step-by-step algorithm is detailed in Table 3.

Motion estimation based on optical flow

Given the low quality of ultrasound images and the inherent characteristics of microvascular flow dynamics, this study applies the optical flow method for motion estimation, enabling the extraction of dynamic vessel features and facilitating high-resolution computation of the motion field. Optical flow is a visual analysis method32 that represents the relative motion velocity of pixels corresponding to a moving object within the imaging plane. It utilizes temporal variations in image intensity to establish the relationship between object motion and scene structure33.

To reduce noise in ultrasound images and enhance the accuracy of motion estimation, the motion field reconstruction model incorporates assumptions regarding dynamic intensity changes, gradient stability, and optical flow field smoothness, supplemented by multiresolution analysis techniques20. Based on these assumptions—constant intensity, constant gradient, and optical flow field smoothness—a deviation penalty function is formulated to derive the optical flow energy function.

The energy functions for intensity and gradient are directly associated with the image data and are classified as data terms within the total energy function. Additionally, the assumption of optical flow field smoothness introduces a corresponding smoothness term. Consequently, the total energy function consists of both data terms and a smoothness term for the optical flow field, as expressed in Eq. (1).

Here, α is the regularization parameter, and EData and ESmooth represent the data term and smoothness term, respectively, as expressed in Eq. (2):

where I represents the image sequence; X = (x,y) denotes the coordinate vector; w = (u,v) is the displacement vector at X; \(\nabla = \left( {\partial x,\partial y} \right)\) is the spatial gradient operator; γ indicates the weight between the intensity assumption and the gradient assumption; \(\psi \left( {s^{2} } \right) = \sqrt {s^{2} + \varepsilon^{2} }\) is a concave function, which enhances the penalty on outliers by implementing quadratic strengthening and improves the robustness of the algorithm. ε is a constant used in numerical computations.

Based on the coverage domain of the binary image and the optical flow method, the influence of noise background is removed, and the optical flow of blood flow is determined. The model extracts vascular elasticity based on SMI blood flow signals. The optical flow model captures both the motion changes and direction of blood flow, thereby augmenting traditional blood flow signals with directional movement and unit flow quantification. Through matrix calculations, we further quantify the relaxation direction (elasticity) of vascular signals and their motion density characteristics.

The directional blood flow optical flow obtained through the optical flow method, combined with vascular morphological features from skeleton extraction, was divided into Microvascular Elastic Density and Microvascular Flow Motion Density.

Dynamic analysis metrics for microvascular flow

The dynamic analysis metrics for microvascular flow, referred to as Superb Microvascular Imaging Dynamic Parameters (SMI-DP), include the blood flow motion density metric and the vascular elasticity density metric.

-

(1)

Microvascular Flow Motion Density

The motion density of microvascular flow, termed SMI Motion Density (SMI-MD), is defined as the ratio of the optical flow motion of all pixels along the skeleton of the blood flow signal between two consecutive frames to the total microvascular flow. This metric is computed for each frame, and a fluctuation curve of SMI-MD over time is generated. SMI-MD reflects the overall dynamic characteristics of blood flow by measuring motion distribution density along the vascular skeleton across adjacent frames. It accounts for blood flow velocity, direction, and motion consistency within the blood flow region, providing a quantitative measure of microvascular motion density. The specific formulation is expressed in Eq. (3).

where \(\phi_{i}^{\parallel }\) represents the motion distribution of pixel \(i{(}x,y{)}\) along the vascular skeleton in consecutive frames, and it is typically calculated using the optical flow method. \(N_{{{\text{vessel}}}}\) denotes the total number of pixels in the vascular region (i.e., the number of pixels within the region of interest) and is used to normalize the dynamic intensity for cumulative analysis.

-

(2)

Microvascular Elastic Density

Given the extremely small cross-sectional area of microvessels, this study uses the variation in the width of microvascular flow in the cross-section to characterize the elastic properties of blood vessels. The microvascular elastic density, referred to as SMI Elastic Density (SMI-ED), for a given frame is defined as the ratio of the motion magnitude of the optical flow components perpendicular to the blood flow signal skeleton across all pixels in two consecutive frames to the total microvascular flow. A fluctuation curve of SMI-ED over time can be plotted based on these calculations. This metric describes the distribution of vascular elastic density during dynamic blood flow changes, providing a quantitative characterization of the dynamic elastic properties of blood flow signals. The specific formulation is expressed in Eq. (4).

where \(\phi_{i}^{ \bot }\) represents the optical flow component perpendicular to the blood flow skeleton at the \(i\)-th pixel. The elasticity of the blood vessels is derived from the contraction and calculation of the blood flow signals in the vertical motion direction.The measurement of volume and the extent of vascular contraction indirectly reflect changes in vascular elasticity, specifically characterized by optical flow changes in the vertical direction of the skeletal orientation.These parameters provide critical support for subsequent pathological diagnosis and the evaluation of joint inflammation.

Automatic grading standard

An automated grading method for joint microvascular flow signals is proposed based on the dynamic analysis of musculoskeletal ultrasound microvascular imaging (SMI-DP). This method employs motion density (SMI-MD) and elasticity density (SMI-ED) as primary metrics to quantify the dynamic properties of blood flow signals, facilitating a multidimensional and precise evaluation and grading of microvascular flow within joint regions.

In this approach, Vave represents the average value of the fluctuation curve, while Vmax indicates its maximum value. Ranges for these metrics are defined to establish a grading system based on dynamic characteristics. During automated grading, both metrics must strictly conform to the specified standards for each grade. The grading criteria are outlined as follows:

Grade 0: No significant fluctuations in microvascular flow signals, with consistently low motion and elasticity density. Grade 1: Mild fluctuations in blood flow signals, with slight increases in motion and elasticity density. Grade 2: Significant fluctuations in blood flow signals, with moderate levels of motion and elasticity density. Grade 3: Highly significant fluctuations in blood flow signals, with both motion and elasticity density reaching high levels.

If inconsistencies arise between the grades of the two metrics, the higher grade is adopted as the final result to enhance sensitivity to abnormalities in blood flow signals. The specific grading criteria are detailed in Table 4.

Statistical methods

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 26.0. Descriptive statistics and the Chi-square test were employed to determine p-values. The primary method for assessing the consistency between automated grading of synovial joints and physician evaluations was the Kappa consistency test.

The methodology involved calculating observed agreement (OA) and expected agreement (EA). Observed agreement was derived from the sum of the diagonal elements in the confusion matrix, while expected agreement was estimated using the marginal totals of the rows and columns. The formula for computing the Kappa value is presented in Eq. (5).

where \(p_{o}\) represents the observed agreement, and \(p_{e}\) represents the expected agreement. The Kappa value ranges between –1 and 1, with higher values approaching 1 signifying stronger agreement. Typically, a Kappa value exceeding 0.6 indicates good agreement, while values below 0 imply substantial disagreement. The statistical significance of the p-value associated with the Kappa test was also computed to confirm the reliability of the consistency between grading levels.

Results

Description of joint microvascular flow grading

Figure 6 displays ultrasound images (A–E) of five patients with varying pathological conditions, with green rectangular boxes identifying the target regions. These images highlight the distribution of blood flow across different anatomical sites and their pathological features. Grading was performed based on blood flow signal density, synovial characteristics, joint effusion, and the severity of soft tissue lesions, revealing a progressive trend from mild to severe (A as grade 0, B as grade 1, C as grade 2, and D and E as grade 3).

Blood Flow Signal Grading in Patients with Different Pathological Conditions (A) Ultrasound image of a patient graded as SMI level 0; (B) Ultrasound image of a patient graded as SMI level 1; (C) Ultrasound image of a patient graded as SMI level 2; (D and E) Ultrasound images of patients graded as SMI level 3.

Figure 6A illustrates effusion within the suprapatellar bursa and medial and lateral joint spaces of the left knee (measuring 2.33 × 0.48 cm, 1.66 × 0.38 cm, and 1.36 × 0.38 cm, respectively). Synovial thickening and reduced echogenicity suggest mild inflammatory changes in the synovium. The absence of significant blood flow signals indicates minimal vascular proliferation and mild osteoarthritis. Furthermore, thickening of the lateral collateral ligament with blurred fibrous structures suggests potential ligament injury. This case is classified as grade 0.

Figure 6B reveals effusion within the suprapatellar bursa (0.61 × 0.17 cm) and medial (0.84 × 0.30 cm) and lateral (0.58 × 0.34 cm) joint spaces of the left knee, along with synovial thickening and heterogeneous echogenicity, indicative of inflammatory changes. The presence of minimal blood flow signals suggests early active inflammation, with a noticeable increase in vascular activity compared to Fig. 6A. This case is assigned a grade of 1.

Figure 6C shows a hypoechoic region at the proximal attachment of the right gastrocnemius muscle, accompanied by a substantial presence of blood flow signals, indicative of localized strain. Blurred fibrous structures suggest mechanical damage coupled with localized inflammatory responses. The pronounced increase in blood flow signals reflects heightened dynamic inflammatory activity. Despite the localized nature of the lesion, the significant enhancement of blood flow signals justifies a grade of 2.

Figure 6D depicts effusion in the joint cavity and medial and lateral joint spaces of the left knee (0.98 × 0.23 cm, 0.81 × 0.38 cm, and 2.86 × 0.59 cm, respectively). Marked synovial thickening and reduced echogenicity are evident, indicative of osteoarthritic inflammatory changes. Edema in the soft tissue beneath the patellar edge, coupled with abundant and blurred blood flow signals, suggests notable alterations in synovial and soft tissue vascular supply. The extensive nature of the lesion and the active inflammatory response are consistent with a grade of 3.

Figure 6E demonstrates thickening and hypoechoic areas (3.03 × 0.88 cm) in the prepatellar fat layer of the right knee, accompanied by abundant blood flow signals. Effusion is observed in the suprapatellar bursa and medial and lateral joint spaces (1.76 × 0.32 cm, 1.23 × 0.28 cm, and 0.74 × 0.28 cm, respectively). The dense distribution of blood flow signals indicates pronounced inflammatory changes in the synovium and soft tissues, as well as joint cavity effusion, showing activity levels comparable to those in Fig. 6D. This case is classified as grade 3.

Dynamic analysis metrics for microvascular flow

Microvascular flow motion density

Figure 7 illustrates the fluctuation curves of microvascular flow motion density (SMI-MD) over time, divided into five subplots (A–E). Each subplot includes four curves representing distinct thresholds (0.75, 0.80, 0.85, and 0.90). The threshold values are denoted by different colors: gray (0.75), blue (0.80), pink (0.85), and cyan (0.90). The legend located in the bottom-right corner clarifies the corresponding threshold for each curve.

These curves represent the dynamic variations in SMI-MD over time under various threshold conditions. At lower thresholds, such as 0.75, the curves exhibit greater fluctuation amplitudes, indicating more pronounced temporal changes. Conversely, at higher thresholds, such as 0.90, the fluctuations are smaller, and the curves appear smoother and more stable. The distinct fluctuation patterns observed across subplots emphasize the variability in SMI-MD under different temporal and threshold conditions.

Microvascular elastic density

Figure 8 displays five subplots (A-E) showing the fluctuation curves of microvascular elastic density (SMI-ED) over time. Each subplot includes SMI-ED curves corresponding to four thresholds (0.75, 0.80, 0.85, and 0.90). The thresholds are represented by the following colors: gray (0.75), blue (0.80), pink (0.85), and cyan (0.90), with a legend in the bottom-right corner providing identification for each threshold.

These curves illustrate the dynamic trends of SMI-ED over time. Larger fluctuations are observed at lower thresholds, such as 0.75, reflecting a higher sensitivity to temporal changes. In contrast, higher thresholds, such as 0.90, result in smoother curves with reduced fluctuation amplitudes. The distinct patterns observed under different thresholds highlight the variability of microvascular elastic density over time and across varying threshold conditions.

Differences, similarities, and severity assessment

All cases depicted in Fig. 6 display osteoarthritic characteristics, including synovial thickening, reduced echogenicity, and joint effusion, with varying degrees of enhanced blood flow signals correlating to different levels of inflammatory activity. Soft tissue abnormalities are also evident, such as ligament thickening in Fig. 6A, strain in Fig. 6C, and edema beneath the patellar margin in Fig. 6D, underscoring the link between osteoarthritis and soft tissue lesions. The primary variations are observed in the distribution and density of blood flow signals: Grade 0 (Fig. 6A) exhibits no detectable blood flow signals, indicating minimal inflammatory response; Grade 1 (Fig. 6B) reveals sparse blood flow signals, signifying early active inflammation; Grade 2 (Fig. 6C) shows localized but abundant blood flow signals; and Grade 3 (Fig. 6D and E) demonstrates densely concentrated blood flow signals, reflecting extensive active inflammation. Progression from Fig. 6A to Fig. 6E reveals a marked escalation in lesion severity, with synovial thickening expanding from localized to widespread areas, blood flow signal density increasing significantly, and inflammatory activity intensifying from mild to severe. Grade 0 represents static synovial inflammation, Grades 1 and 2 indicate progressively active inflammatory states, and Grade 3 corresponds to the most advanced inflammatory phase, characterized by significant vascular proliferation and associated tissue changes. This grading system effectively illustrates the dynamic progression of osteoarthritis, providing a robust framework for quantifying blood flow and advancing automated grading methodologies based on the optical flow model. Additionally, as blood flow signal grades increase, the patterns of SMI Motion Density (SMI-MD) and SMI Elastic Density (SMI-ED) curves become more distinct and exhibit consistent trends, further validating the grading system’s reliability.

Clinical validation

The consistency between the automated grading of synovial blood flow and physician ratings was assessed using the Kappa consistency test. Based on the confusion matrix (Table 5), the study included 47 participants, consisting of 20 males and 27 females (p = 0.307 > 0.05, χ2 = 1.042), indicating no statistically significant difference in gender distribution. The participants’ ages ranged from 30 to 65 years, with a mean age of 45.3 years, reflecting the primary high-risk demographic for osteoarthritis. The observed agreement between automated grading and physician ratings was 70.2%, demonstrating substantial consistency. The calculated Kappa value of 0.627 indicates good agreement (Kappa > 0.6), while a Kappa value below 0 would denote significant disagreement. Additionally, the observed agreement (70.2%) was notably higher than the expected agreement (51.2%). The statistical significance test revealed p < 0.001, providing strong evidence for the reliability and robustness of the consistency between the automated and physician-assessed grading results.

Further analysis found that the automatic rating system was more inclined to give higher grade results when the physician rating was level 2, which may be related to the noise in the blood flow signal or the threshold setting of the middle grade by the blood flow signal classification algorithm.These findings suggest that the automated system requires further optimization to enhance its accuracy in identifying moderate cases of osteoarthritis. Nonetheless, the results validate the overall effectiveness of the automated grading system for osteoarthritis classification while emphasizing the need for algorithmic refinement in specific contexts.

Discussion

This study successfully implemented automated grading of joint superb microvascular flow signals through dynamic analysis using the optical flow model, demonstrating the potential of dynamic blood flow evaluation for the quantitative assessment of osteoarthritis. The findings showed substantial consistency between the automated grading system and physician ratings, as evidenced by a Kappa value of 0.627 (p < 0.001), with observed agreement significantly exceeding expected agreement (70.2% vs. 51.2%). These results affirm the efficacy of the proposed method for the quantitative analysis of superb microvascular flow signals, highlighting its promise in supporting clinical evaluation and grading of osteoarthritis.

Compared to traditional grading methods for osteoarthritis, the proposed approach offers substantial advantages in analytical depth and objectivity of results. Traditional methods, such as the semi-quantitative grading system introduced by Szkudlarek et al.34, rely on subjective evaluation of static ultrasound images, which is highly influenced by operator expertise, equipment parameters, and image quality, leading to inconsistent outcomes. Recent advancements in deep-learning-based automated grading methods have improved accuracy and consistency by extracting features from static images35,36. Traditional methods, such as Singular Value Decomposition (SVD), are effective in distinguishing tissue from blood flow. The SVD enables the separation of blood flow and tissue in each frame, it does not account for the directionality of blood flow37,38. However, these approaches are limited by their inability to capture the dynamic characteristics of blood flow signals. Our approach addresses this limitation by incorporating directional information for each blood flow pixel. Compared to SVD, our model more accurately reflects the movement of blood flow, as it operates within the framework of dynamic analysis. By utilizing dynamic analysis through the optical flow model, this study is the first to quantify changes in superb microvascular flow signals over time, significantly enhancing the objectivity and clinical relevance of grading results.

This study also revealed a consistent tendency for the automated grading system to underestimate ratings when physician evaluations were at Grade 2. This challenge may be linked to the intricate dynamic behavior of blood flow signals in cases of moderate inflammation, where characteristics of both low-grade and high-grade inflammation are present, complicating classification. Moreover, the threshold parameters for motion characteristics in the optical flow algorithm may require refinement to improve the differentiation of intermediate-grade osteoarthritis. Similarly, prior research has noted that machine learning-based grading methods often exhibit reduced performance for intermediate levels compared to clearly defined lower or higher-grade lesions39. These findings underscore the importance of further optimizing the algorithm to address the complexities of moderate osteoarthritis classification.

While this study highlights the potential of an optical flow model-based dynamic analysis system for quantitative osteoarthritis grading, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the relatively small sample size may constrain the generalizability of the algorithm across a broader spectrum of lesion ranges and severity levels. Second, the study focused solely on osteoarthritis, leaving its applicability to other joint pathologies, such as rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthropathy, unexplored. Furthermore, the algorithm’s adaptability in complex clinical scenarios, such as synovitis combined with soft tissue injuries or multiple lesions, has not been fully assessed. Ultrasound propagation in blood or tissue can be influenced by factors such as motion, posture, and noise, which may affect the accuracy of flow measurements. To mitigate the uncertainty caused by high-frequency signals, we employed an optical flow model for dynamic analysis and motion estimation, allowing for more accurate tracking of blood flow changes and improved measurement stability. During image processing, we used distance-based clustering to remove incidental weak signals. However, occasional misclassification of strong signals remains. Additionally, discontinuities in edge detection and skeleton extraction may introduce uncertainty in the quantification process. To address this, we excluded smaller discontinuous flow signals during clustering using a predefined threshold. However, determining the exact size of discontinuous signals remains an area for future research. In dynamic analysis, signal discontinuities or missing segments may introduce uncertainty in quantification, particularly when dealing with complex or subtle inflammatory cases. Noise interference can cause significant fluctuations in blood flow signals, but we have mitigated this effect using smoothing techniques. Despite this, the optical flow model is capable of compensating for some of these missing signals, reducing their impact on diagnostic results.

Future research could address these limitations by incorporating larger, multicenter datasets to improve the algorithm’s ability to extract features, especially for intermediate-grade classifications. The integration of deep learning techniques with optical flow model dynamic analysis may allow for the identification of more nuanced blood flow signal characteristics, enhancing the accuracy and robustness of grading. These advancements could establish the proposed method as a valuable tool for non-invasive diagnosis and dynamic monitoring of synovial lesions. Such improvements would facilitate comprehensive support for early diagnosis, treatment evaluation, and disease management of arthritis, broadening its clinical utility.

Conclusion

This study successfully implemented an automated grading system for joint superb microvascular flow signals using dynamic analysis based on the optical flow model, demonstrating its effectiveness in the quantitative evaluation of osteoarthritis. The findings showed substantial consistency between the automated system and physician ratings, with agreement levels significantly exceeding expectations. These results underscore the method’s ability to minimize subjective influence and improve grading Aobjectivity. By incorporating dynamic analysis, the study quantified motion characteristics of blood flow signals, addressing the limitations of traditional static image-based grading methods. This novel technical approach offers a promising tool for non-invasive diagnosis and dynamic monitoring of osteoarthritis, while providing a foundation for the further refinement of algorithm performance and the exploration of broader clinical applications.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions and institutional policies. However, anonymized data can be made available from the corresponding author on reasonable request and with approval from the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Fourth Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine.

References

Lal, C. & Leahy, M. J. An updated review of methods and advancements in microvascular blood flow imaging. Microcirculation 23, 345–363 (2019).

Yu, H. et al. Improving microvascular sensitivity of color doppler using phase mask based flow recycling algorithm. Phys. Med. Biol. 69, 215010–215010 (2024).

Katharina, G. et al. Microvessel ultrasound of neonatal brain parenchyma: Feasibility, reproducibility, and normal imaging features by superb microvascular imaging (SMI). Eur. Radiol. 29, 2127–2136 (2019).

Seskute, G., Jasionyte, G., Rugiene, R. & Butrimiene, I. The use of superb microvascular imaging in evaluating rheumatic diseases: A systematic review. Medicina 59, 1641 (2023).

Amin, M. A., Fox, D. A. & Ruth, J. H. Synovial cellular and molecular markers in rheumatoid arthritis. Semin. Immunopathol. 39, 385–393 (2017).

Lim, A. K. P., Satchithananda, K., Dick, E. A., Abraham, S. & Cosgrove, D. O. Microflow imaging: New Doppler technology to detect low-grade inflammation in patients with arthritis. Eur. Radiol. 28, 1046–1053 (2018).

Sarbu, N. et al. White matter diseases with radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics 36, 1426–1447 (2016).

Coates, A. S. et al. Tailoring therapies—Improving the management of early breast cancer: St Gallen International Expert Consensus on the Primary Therapy of Early Breast Cancer 2015. Ann. Oncol. 26, 1533–1546 (2015).

Qureshi, M. M. et al. Advances in laser speckle imaging: From qualitative to quantitative hemodynamic assessment. J. Biophotonics 17, e202300126 (2024).

Jakubaszek, M., Płaza, M. & Kwiatkowska, B. Color fraction as a useful method of imaging synovium vascularization in patients with high activity of rheumatoid arthritis. Reumatol./Rheumatol. 58, 42–47 (2020).

Cutolo, M. & Smith, V. Detection of microvascular changes in systemic sclerosis and other rheumatic diseases. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 17, 665–677 (2021).

Usui, T., Macleod, M. R., McCann, S. K., Senior, A. M. & Nakagawa, S. Meta-analysis of variation suggests that embracing variability improves both replicability and generalizability in preclinical research. PLoS Biol. 19, e3001009 (2021).

Lei, L., Ding, W., Huang, L., Zhuang, X., & Grau, V. Multi-modality cardiac image computing: A survey. Med. Image Anal. 88102869 (2023).

Yang, A. C. et al. Sparse reconstruction techniques in magnetic resonance imaging: Methods, applications, and challenges to clinical adoption. Investig. Radiol. 51, 349–364 (2016).

Li, L. & Yang, Y. Optical flow estimation for a periodic image sequence. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 19, 1–10 (2009).

Zherebtsov, E., et al. Enhancing transcranial blood flow visualization with dynamic light scattering technologies: Advances in quantitative analysis. Laser Photonics Rev. 2401016 (2024).

Kuliga, K. Z. et al. Dynamics of microvascular blood flow and oxygenation measured simultaneously in human skin. Microcirculation 21, 562–573 (2014).

Chen, M. B. et al. On-chip human microvasculature assay for visualization and quantification of tumor cell extravasation dynamics. Nat. Protoc. 12, 865–880 (2017).

Dong, C.-Z., Celik, O., Catbas, F. N., O’Brien, E. J. & Taylor, S. Structural displacement monitoring using deep learning-based full field optical flow methods. Struct. Infrastruct. Eng. 16, 51–71 (2020).

Boquet-Pujadas, A. & Olivo-Marin, J. C. Reformulating optical flow to solve image-based inverse problems and quantify uncertainty. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 45, 6125–6141 (2022).

Panwar, P., Chaurasia, S., Gangrade, J., Bilandi, A. & Pruthviraja, D. Optimizing knee osteoarthritis severity prediction on MRI images using deep stacking ensemble technique. Sci. Rep. 14, 26835 (2024).

Alzubaidi, L., et al. Comprehensive review of deep learning in orthopaedics: Applications, challenges, trustworthiness, and fusion. Artif. Intell. Med. 102935 (2024).

Fortun, D., Bouthemy, P. & Kervrann, C. Optical flow modeling and computation: A survey. Comput. Vis. Image Underst. 134, 1–21 (2015).

Carpenter, H. J., Ghayesh, M. H., Zander, A. C. & Psaltis, P. J. On the nonlinear relationship between wall shear stress topology and multi-directionality in coronary atherosclerosis. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 231, 107418 (2023).

Cortes, D. R. E. et al. Modeling normal mouse uterine contraction and placental perfusion with non-invasive longitudinal dynamic contrast enhancement MRI. PLoS ONE 19, e0303957 (2024).

Zuo, C. et al. Deep learning in optical metrology: A review. Light Sci. Appl. 11, 1–54 (2022).

Ben Yedder, H., Cardoen, B. & Hamarneh, G. Deep learning for biomedical image reconstruction: A survey. Artif. Intell. Rev. 54, 215–251 (2021).

Chen, C. L. & Wang, R. K. Optical coherence tomography based angiography. Biomed. Opt. Express 8, 1056–1082 (2017).

Glandorf, L. et al. Bessel beam optical coherence microscopy enables multiscale assessment of cerebrovascular network morphology and function. Light Sci. Appl. 13, 307 (2024).

de Sousa, R. N. et al. Metabolic and molecular imaging in inflammatory arthritis. RMD Open 10, e003880 (2024).

Minopoulou, I. et al. Imaging in inflammatory arthritis: Progress towards precision medicine. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 19, 650–665 (2023).

Sun, D., Roth, S. & Black, M. J. A quantitative analysis of current practices in optical flow estimation and the principles behind them. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 106, 115–137 (2014).

Kirbas, C. & Quek, F. A review of vessel extraction techniques and algorithms. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 36, 81–121 (2004).

Ellegaard, K. et al. Comparison of discrimination and prognostic value of two US Doppler scoring systems in rheumatoid arthritis patients: A prospective cohort study. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 32, 495–500 (2014).

Zheng, H. D. et al. Deep learning-based high-accuracy quantitation for lumbar intervertebral disc degeneration from MRI. Nat. Commun. 13, 841 (2022).

Lu, W. et al. Deep learning-based automated classification of multi-categorical abnormalities from optical coherence tomography images. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 7, 41 (2018).

Ikeda, H. et al. Singular value decomposition of received ultrasound signal to separate tissue, blood flow, and cavitation signals. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 57(7S1), 07LF04 (2018).

Lok, U.-W. et al. Real time SVD-based clutter filtering using randomized singular value decomposition and spatial downsampling for micro-vessel imaging on a Verasonics ultrasound system. Ultrasonics 107, 106163 (2020).

Humphries, S. M. et al. Deep learning enables automatic classification of emphysema pattern at CT. Radiology 294, 434–444 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the medical staff in the Department of Ultrasound in Medicine for their support in providing information about patients. This research was supported by Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (Grant No.LGF22H180006); General Research Projects of Zhejiang Provincial Department of Education(Grant No.Y202353881); the Zhejiang Provincial Department of Science and Technology 2024 Pointman Programme(Grant No.2024C03270).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, S. N. L. and B. S. ; Data curation, S. N. L. , B. S. and Z. H. Z. ; Formal analysis, Z. H. Z. and C. J. W.; Funding acquisition, S. N. L. , X. J. Z. and Q. L. Z. ; Investigation, B. S. and Y. H. D.; Methodology, S. N. L. and B. S.; Project administration, Y. Q. S. and X. J. Z. ; Resources, Q. L. Z. , Y. Q. S. and X. J. Z. ; Supervision, Y. Q. S. and X. J. Z. ; Validation, J. L. Y. ; Visualization, S. N. L. and B. S. ; Writing – original draft, S. N. L. and B. S. ; Writing – review & editing, S. N. L. and X. J. Z.. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethics approval for this retrospective study was obtained from the Fourth Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine Human Research Ethics Committee (approval number: K2024220). The data used in this study were extracted from a pre-existing database established in 2023. Although the original database contained case records, all personal identifiers, including medical record numbers, were removed prior to analysis to ensure anonymity. As such, informed consent was waived by the Fourth Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine Human Research Ethics Committee. The images presented in this manuscript do not contain any identifiable personal details. All individuals depicted in the images have been anonymized, and no information is provided that could lead to the identification of any person. This study was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki and all applicable ethical guidelines.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, S., Shang, B., Yan, J. et al. A method for quantifying and automatic grading of musculoskeletal ultrasound superb microvascular imaging based on dynamic analysis of optical flow model. Sci Rep 15, 13369 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97924-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97924-1