Abstract

During crisis periods, understanding the impact of sleep quality on self-rated health becomes crucial. However, the role of anxiety and depression as potential mediators in this relationship remains insufficiently explored. Therefore, this study aimed to assess the association of sleep quality with self-rated health, and mediation by anxiety and depression. This cross-sectional, population-based study was conducted with 1762 adults from October to December 2020 in the Iron Quadrilateral region of Brazil. The exposure variable was poor sleep quality, as measured by the PSQI. The outcome was self-rated health. The mediators tested were anxiety and depression, which were evaluated using symptoms, medical diagnoses, and the use of drugs. To test the mediators’ factors, the Karlson–Holm–Breen method was used. The direct acyclic graph was used to select a minimal set of adjustments in multivariate analysis. There were 22.6% of people who rated their health as poor, 52.5% were poor sleepers, 35.1% had symptoms of anxiety and 24.7% had symptoms of depression. According to the multivariate analysis, individuals with poor sleep quality were 2.82 times more likely to self-assess their health as poor. The presence of symptoms of anxiety and depression explained 16.57% and 5.99% of the association between poor sleep quality and poor self-rated health, respectively, in the mediation analysis. During the COVID-19 pandemic, individuals who had poor sleep quality had lower self-rated health. Furthermore, symptoms of anxiety and depression explained a portion of the association. Our study emphasizes the importance of evaluating individuals’ sleep quality and mental health during a crisis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

One of the biggest health and social issues of the twenty-first century is the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic has led to a wide range of health impacts, encompassing biological, social, and behavioral aspects, in addition to the direct consequences of the illness1,2,3. Sleep quality, mental health, and self-rated health emerge as critical psychosocial factors, deeply affected by global changes1,4.

COVID-19 has altered different aspects of life, including sleep4. Sleep quality is intrinsically relevant to health and can influence people’s physical and mental well-being5. The consequences of lack of sleep are tiredness and fatigue, memory and attention failures, a drop in immunity, sadness and irritability, high blood pressure, and hormonal changes6,7. These effects can affect not only the objective aspects of health, such as the functioning of organs and systems but also the subjective aspects, such as the individual’s perception of themselves8. However, a critical gap remains in understanding the broader health implications of sleep quality during this period, especially in populations such as Brazil, where studies are limited.

The COVID-19 pandemic represents a critical period for examining these associations due to the profound disruption in daily life and heightened emotional stress experienced globally2. In Brazil, the pandemic exacerbated pre-existing inequalities, creating a unique environment for studying health determinants9. However, there is a significant gap in research addressing sleep quality and self-rated health in this context, particularly in countries with high social disparities, such as Brazil. Understanding these relationships during the pandemic can provide insights not only into the immediate impacts of this global crisis but also into the long-term implications for population health.

Poor sleep can interfere with an individual’s ability to take care of themselves, making it difficult for them to adopt healthy habits that could improve their health10,11. In addition, poor sleep quality can damage an individual’s self-esteem, confidence, and motivation, leading them to self-assess their health as poor12. Self-rated health is a subjective measure that reflects people’s perception of their general state of health, considering physical, emotional, and social aspects13. Previous studies have shown that individuals with poor sleep quality tend to rate their health as poor and that this association is independent of other sociodemographic and clinical factors8,14,15.

Given the limited research during the pandemic period, this study aims to examine the association between sleep quality and self-rated health during the COVID-19 pandemic, while exploring anxiety and depression as potential mediators. Using a population-based, face-to-face approach, conducted when vaccines were not yet available.

Methods

Study design

We made use of information from the Federal University of Ouro Preto’s (UFOP) population-based serological survey, “COVID-Inconfidentes: Epidemiological surveillance of COVID-19 in the region of Inconfidentes/MG.” The analyzed data was collected in two medium-sized towns in the south-central region of Minas Gerais, Brazil, which is one of the country’s major iron ore-producing regions, between October and December 2021.

Conglomerate carried out the sample design in three phases: household, resident, and census sector. The National Household Sample Survey (PNAD)16, the Family Budget Survey (FBS)17, the “Saúde em Beagá” survey18, and National Health Survey (NHS)19 served as the foundation for this design. As a result, the census sectors were used as the main sampling units in the study design. They were chosen with a probability proportionate to the number of households, and the number of households was taken as a measure of size from the summary of the 2010 population census by census sectors. In order to minimize the possibility of selecting a sample from non-representative sectors (primary units), prior stratification was carried out before selecting the primary units, taking into account the average income, based on data from the 2010 demographic census of the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE). Consequently, the final sample was guaranteed to be representative of the three socioeconomic strata (wages less than one, wages between one and three, and wages greater than four).

The updated list of current household units in the primary sampling units (selected census sectors) was used to select the households that made up the secondary sampling units in a methodical manner. Both private homes and housing units in communal residences with occupants make up the household units. Following the census sectors’ selection, the household selection interval (k) for the systematic sampling was computed using the following formula: k = Ni/(xi/ni), where Ni is the total number of households in the census sector, xi is the sample size, and ni is the number of households to be selected. This method covered the entire geographic area and produced a proportionate number of homes per sector. Following the selection of the first home in the census sector based on IBGE indications, the next household was systematically sampled in accordance with the household selection interval (k).

The individuals who were chosen through a basic random sampling process constituted the tertiary sampling units. A list of every adult resident in the chosen home was created, and one resident was chosen at random to take part in the study. A previous publication provides further details regarding data collection20.

In-person interviews were conducted with the adult residents (≥ 18 years) in their homes using an electronic form. Living habits, general health status, and sleep quality were characterized by thematic components of the questionnaire. Information assessed was collected using scales built and validated in Brazil. An instrument designed for this survey was used to ask specific questions about societal and financial traits, among other things. The previously published scales are explained in the method below, and we’ve also included the complete survey instrument with all the questions as additional information.

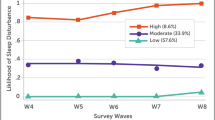

Exposure: poor sleep quality

To assess the quality of sleep, the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index was used. With an overall reliability coefficient of 0.82, the Brazilian version of the PSQI demonstrated high internal consistency. This test consists of 19 questions divided into 7 components, each with a score ranging from 0 to 3: subjective quality of sleep (C1), sleep latency (C2), duration of sleep (C3), habitual efficiency of sleep (C4), and sleep disturbances (C5) The overall score is calculated by adding up the scores, with the highest score indicating the lowest quality of sleep21. Sleep was the two categories used in this study: good quality (PSQI score ≤ 5) and poor quality (PSQI score > 5) sleep.

Outcome: self-rated health

The outcome variable, self-rated health, was assessed by asking, “In general, how do you rate your health?”13. Very poor, poor, regular, good, and very good were the options for the response. Following that, this variable was split into two categories: good (which included the very good and good categories) and poor (which included the very poor, poor, and regular categories).

Mediators: mental health

The presence of depression or anxiety was evaluated as one of the mediation factors. We used medication use, self-report of medical diagnosis, and symptoms to assess these factors. We classified participants with anxiety or depression if they met at least one of these requirements.

The generalized anxiety disorder scale (GAD-7) and the patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9) scales, both translated and validated in Portuguese, were used for the symptom criterion22,23. The GAD-7 is a seven-item, four-point Likert scale with a maximum score of 21 points24. Nine questions make up the PHQ-9, a four-point Likert scale with a score range of 0 to 27 points25. Scores of 10 or higher on both scales were regarded as suggestive of symptoms of anxiety and depression, respectively24,25.

The self-report criterion was asked if the participants had ever been given a medical diagnosis of anxiety or depression.

We inquired about every medication that each participant took and categorized them using the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) code of the World Health Organization. We took into account drugs with codes N03 (antiepileptics), N05 (psycholéptics), N06 (psychoanaleptics) and N07 (other medications in the nervous system)26.

Covariates

In the study, the assessment of multiple covariates was included. There were categories for men and women. 18–34 years, 35–59 years, and 60 years and older were the three age groups established. Black, brown, indigenous and yellow skin color were classified in same category. Marital status was different between married and single people. The educational attainment of participants was categorized based on the number of years of formal education they completed: 0–8 years, 9–11 years, and 12 or more years. The three categories of family income were 2 to 4 MW, 4 MW, and 2 minimum wage. Two categories for employment status were yes and no. There were two categories of smoking behavior. Drinking alcohol was categorized as either yes or no, according to the survey.

Sedentary and physical activity behaviors were among the movement behaviors evaluated for movement behaviors. The World Health Organization established guidelines for evaluating physical activity, which stated that a person was deemed physically inactive if they performed less than 150 min of moderate-intensity physical activity or less than 75 min of vigorous-intensity physical activity per week27. The total amount of time spent sitting was used to classify sedentary behavior; values ≥ 9 h were considered elevated28.

A self-reported medical diagnosis assessment was included in the study to evaluate comorbidities. The chronic diseases included cancer, heart disease, diabetes, asthma, lung disease, thyroid issues, hypertension, and chronic kidney disease. Participants were categorized as either having no comorbidities (no) or at least one comorbidity (yes) based on their self-reported medical history.

Statistical analysis

To adjust the natural weights of the design and address issues brought on by the lack of response or refusal to provide information, the sample weight of each chosen unit (census sector, household, and individual) was first determined independently for each city. To calibrate the natural expansion factors, new weights for every sample member must be estimated. The ratio of the number of census sectors in the sample that were chosen from the city “i” to the number of census sectors in the hole city “i” is denoted by “Ni” and represents the probability of selecting a census sector in each city in the sample. The formula dij/Dij, where “dij” is the number of sampled households in sector “j” of the city “i” and “Dij” is the number of households in sector “j” of the city “i,” was used to determine the probability that the household in census sector “j” of municipality “i” would be selected. The likelihood of each person living in the chosen household is calculated as 1/(the number of household members who are 18 years of age or older)29.

Stata software version 15.1 (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas) was used for the analyses, and the command “svy”—which takes into account a complex sample design—was employed. To evaluate the effects of the complex sampling design on our results, we calculated the design effect (DEFF) and coefficient of variation (CV) for key estimates. The DEFF, which compares the variance under the complex design to that expected under simple random sampling (SRS), remained consistently low, with values near or below 3. This indicates a minimal inflation of variance due to the design. Additionally, the CV, which measures relative variability, was generally below 10–15%, reflecting the robustness and precision of the estimates obtained. These metrics affirm the reliability of our findings while underscoring the representativeness and statistical rigor of the data analysis.

Percentages and confidence intervals (CI95%) are used to display the data. A significance level of 0.05 was chosen. Utilizing logistic regression analysis, the relationship between sleep quality and self-rated health was estimated. The multivariate model included additional variables as covariates, with sleep quality being the primary independent variable. We used the directed acyclic graph (DAG), a graphical tool that shows the causal relationships between the variables of interest, to choose the covariates (Fig. 1). Without confounding, collision, or collinearity biases, the DAG can be used to determine which variables should be changed to estimate the association of sleep quality with self-rated health. Any variables that were linked to self-rated health and sleep quality but weren’t mediators, colliders, or offspring of the exposure or result were considered potential confounding variables. The minimum set of confounding variables was chosen using the backdoor criterion to prevent erroneous associations and adjustments30. The minimal and sufficient set of variables—age, sex, family income, use of alcohol and tobacco, and chronic illnesses—were added to the model. These factors may have varying effects on self-rated health and the quality of sleep. The theoretical model created for this study is shown visually in Supplementary Table 1, “Health-related pathways overview illustrated in the directed acyclic graph (DAG)”.

Directed acyclic graph (DAG) on sleep quality and self-rated health in adults during the COVID-19 pandemic (COVID-Inconfidentes Study). Legend: The variable in green and with the “ > ” symbol inside the rectangle was the exposure variable; those in blue and with the letter “I” inside the rectangle were the response variables; variables in blue are the antecedents of the outcome variable, and those in red are antecedents of the outcome and exposure variables.

Furthermore, a mediation analysis was carried out using the Karlson Holm Breen (KHB) method. This approach, which is mediated by anxiety and depression, calculates the overall, direct, and indirect effects of sleep quality on self-rated health. It assesses the statistical significance of the mediation and breaks down the logistic regression coefficients into total, direct, and indirect effects31. We examined a few prerequisites, including the theoretical causal structure, the path analysis, and the interaction, before performing the mediation analysis. Based on theory and research, we established the causal structure, which shows that anxiety and depression have a direct and indirect impact on self-rated health due to poor sleep quality. To confirm whether there was a significant relationship between the variables involved in the mediation, we carried out a path analysis. To determine the influence of the mediators on the variation in the effect of sleep quality on self-rated health, we conducted an interaction analysis. In the logistic regression model, we accounted for interactions between anxiety and depressive symptoms and sleep quality. We predicted that the interaction would not be significant, which would mean that for all mediator levels, the effect of sleep quality on self-rated health would remain constant. This is exactly what we discovered (Supplementary Table 2).

Results

The self-rated health of 1,762 adults aged 18 years or older was assessed in this study. The distribution of self-assessed health among the participants is presented in Fig. 2. We found that 77.4% of people rated their health as good (including both “very good” and “good”), while 22.6% rated their health as poor.

The study population’s characteristics and their association with self-rated health are presented in Table 1. There were 51% women and 46% people between the ages of 35 and 59. The majority of them self-reported their skin color as black, brown, indigenous or yellow. More than half of them were married and had more than eight years of education. About 41.1% of households reported a family income of less than or equal to twice the minimum wage. They were active workers when it came to their occupational status. Concerning their behavior, they currently consume alcohol at 58.2% and smoke at 17% Furthermore, 69.2% of respondents displayed inactivity, and 15.3% engaged in sedentary activities. 52.5% of participants had poor sleep, while 23.4% and 15.8% had symptoms of anxiety and depression, respectively.

The self-rated health was significantly different according to sex, age, education, working status, alcohol consumption, physical activity, sleep quality, and symptoms of anxiety and depression.

Figure 3 shows the result of the path diagram with the mediation analysis, using the Karlson Holm Breen (KHB) method. The odds ratio (OR) for regular, poor, or very poor self-rated health among those with poor sleep quality was 2.82 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.83–4.32; p < 0.001), compared to those with good sleep quality (Fig. 3). Therefore, the β of the total effect of poor sleep quality on lower self-rated health was 1.035 (95% CI 0.610–1.470; p < 0.001), which was decomposed into a direct effect β of 0.802 (95% CI 0.359–1.244; p < 0.001) and an indirect effect β of 0.233 (95% CI 0.077–0.390; p < 0.001). The indirect effect was partially mediated by anxiety symptoms (β: 0.172; p = 0.006) and depression symptoms (β: 0.062; p = 0.010). The proportion of mediation was 16.57% for anxiety and 5.99% for depression, indicating that anxiety and depression symptoms explained about one-fifth of the association between poor sleep quality and lower self-rated health.

Path diagram of the mediation analysis of the role of sleep quality in self-rated health using depression symptoms and anxiety disorders symptoms (COVID-Inconfidentes Study). Path analysis based on multivariate logistic regressions, adjusted for the minimum and sufficient set of variables: sex, age, family income, alcohol and tobacco consumption, and chronic diseases. Total, direct, and indirect effects were assessed using the Karlson-Holm-Breen method. a1 indicates the total effect of sleep quality on self-rated health; b1 represents the effect of sleep on anxiety; c1 represents the effect of sleep on depression; b2 represents the effect of anxiety on self-rated health; c2 represents the effect of depression on self-rated health; a2 indicates the direct effect of sleep on self-rated health; a3 indicates the indirect effect of sleep on self-rated health.

Discussion

The self-rated health of adults living in urban areas in Brazil during the COVID-19 pandemic was evaluated in this study. Sleep quality was associated with self-rated health, and anxiety and depression partially mediated this association, explaining about one-fifth of the effect of sleep on self-esteem. Mental disorders may act as mechanisms through which sleep affects health during the COVID-19 pandemic, according to these findings.

Our results are from previous studies that have shown a negative association between sleep quality and self-rated health in different populations15. The COVID-19 pandemic may have exacerbated this relationship, with changes in people’s sleep habits and routines1,32. Sleep quality can influence self-rated health through various physiological, psychological, and social mechanisms. As previously described, lack of sleep affects various aspects of health, including immunity, metabolism, and mental well-being. This can lead to chronic diseases, affect mood and cognition, and impair social relationships. Therefore, our findings underscore the importance of addressing sleep quality for overall health and well-being12,33.

The connection between sleep quality and self-assessed health could be attributed to mental well-being. The rhythms of the night control hormones, neurotransmitters, and cytokines that affect mood, cognition, and stress. The risk of anxiety and depression can be increased by lack of or poor quality sleep34. In addition, anxiety and depression can decrease self-esteem, self-efficacy, motivation, and hope, as well as increase pessimism, social isolation, and psychological distress, leading to a negative perception of health35. This hypothesis about the possible mechanisms underlying the connection between sleep quality and self-assessed health was confirmed by the mediation analysis. The indirect effect of sleep quality on self-rated health was mediated by symptoms of anxiety and depression. The sleep hygiene hypothesis suggests that good sleep quality promotes emotional well-being and prevents the development of mental disorders36. Conversely, poor sleep can negatively affect people’s mood, cognition, and daily functioning, increasing the risk of anxiety and depression37. These mental disorders, in turn, can damage self-rated health, causing psychological distress, low self-esteem, social isolation, and worsening physical health38,39.

There is a gap in the literature that seeks to understand the mediation of mental health in this association, which is why the results are innovative. In a study by Zhu et al. (2023), they assessed the association between sleep quality and self-rated health and examined whether depressive and anxious symptoms can explain/mediate this association. This study found evidence that symptoms of anxiety and depression partially mediated the effect of the association between poor sleep quality and self-rated health40. Several other studies have also shown that individuals with psychological health disorders tend to report a worse state of health13,41,42.

The COVID-19 pandemic may have influenced the relationships observed between sleep quality, mental health, and self-rated health. The pandemic caused a series of stressors for people, such as fear of contagion, social isolation, loss of income, bereavement, uncertainty, and changes in routine43. These stressors can negatively affect sleep quality, increasing difficulty falling asleep or staying asleep, reducing total sleep time, or altering circadian rhythms44. These stressors can also negatively affect mental health, increasing levels of anxiety and depression in the population45. In addition, the pandemic may have negatively affected self-rated health, reducing people’s perception of physical and emotional well-being9. It is therefore possible that the pandemic has exacerbated the impact of poor sleep on mental health and, consequently, on self-rated health. However, we cannot say that the pandemic is the only cause of these associations, as other factors can influence them. For example, genetic, environmental, behavioral, and social factors can affect sleep as well as mental health and self-rated health46,47.

Our findings hold significance for public health interventions and clinical practice, particularly in the context of pandemic response and recovery. Our findings indicate that it is imperative to acknowledge the correlation between sleep quality, mental health, and self-rated health when devising targeted interventions. Sleep quality improvement can have benefits for people’s mental health and self-rated health. Therefore, we recommend implementing strategies to improve the population’s sleep habits, such as maintaining a regular sleep routine, avoiding the use of alcohol, caffeine, and nicotine before bedtime, reducing exposure to artificial light at night, creating a comfortable and quiet environment for sleep, and seeking professional help in case of chronic sleep problems. Some examples of treatments that can enhance sleep quality and mental health include cognitive-behavioral therapy, sleep hygiene, meditation, physical exercise, pharmacotherapy, and psychotherapy.

Despite the methodological efforts made to guarantee the validity and reliability of our results, we recognize some limitations of our study, which should be taken into account when interpreting the findings. Initially, the cross-sectional design does not permit us to establish causal relationships between variables but rather establish associations. Therefore, we cannot claim that sleep quality causes self-rated health, nor that anxiety and depression are the only mediators of this relationship. It is plausible that additional factors exert an impact on both sleep and self-rated health, or that there exists a reversible or bidirectional correlation between the two. To clarify these issues, it is imperative to conduct longitudinal studies that follow participants over time and evaluate changes in sleep quality, self-rated health, and symptoms of anxiety and depression. It is important to consider the possibility of information bias arising from the use of self-administered questionnaires. Participants may have answered the questions based on their memories, perceptions, or expectations, which may have led to errors or distortions in the measurements of the variables. Furthermore, the questionnaire may not capture all the nuances and complexities of sleep quality, self-rated health, and symptoms of anxiety and depression.

Furthermore, while our study focuses on understanding how anxiety and depression explain the relationship between sleep and self-rated health, we acknowledge the possibility that sleep itself could mediate the association between socioeconomic factors and self-rated health, as suggested by recent studies. Exploring this hypothesis was beyond the scope of the current research but represents an important avenue for future work. Another limitation of our study is the use of logistic regression in a cross-sectional design with a highly prevalent outcome, which could overestimate the strength of the associations. To mitigate this, we conducted complementary Poisson regression analyses, the results of which are provided as supplementary materials for further reference.

A representative random sample of the resident population from different socioeconomic strata, assessment through a household survey, and face-to-face interviews during the COVID-19 pandemic are some strengths that should be mentioned. To support the assumptions of the analysis, the hypotheses were carefully defined according to current scientific literature and articulated in counterfactual terms. In this sense, we acknowledge that incorporating broader causal pathways, including the potential mediating role of sleep between socioeconomic factors and self-rated health, could enhance the robustness and comprehensiveness of future studies. In this sense, the inclusion of directed graphical models is of great importance and provides robustness to the study. In this sense, the incorporation of directed graphical models is of great importance and provides robustness to the study.

Conclusion

Sleep quality was strongly associated with people’s self-rated health during the COVID-19 pandemic, and this association was mediated by symptoms of anxiety and depression. These findings highlight critical areas for intervention. Public health strategies and clinical practices should prioritize improving sleep hygiene through educational campaigns, workplace adjustments, and community support initiatives. Simultaneously, addressing mental health through the assessment, prevention, and treatment of anxiety and depression disorders is essential for holistic health promotion. Such integrated approaches could mitigate the adverse health effects observed during the pandemic and beyond.

Furthermore, this study offers valuable insights for clinicians and researchers. Clinicians can utilize these findings to adopt holistic diagnostic and therapeutic strategies, focusing on sleep and mental health as key components of overall well-being. For researchers, our results highlight the need for further studies to elucidate the mechanisms linking sleep quality, mental health, and self-rated health, while providing a foundation for designing innovative, interdisciplinary research approaches. By addressing these interconnected issues, both clinical and research efforts can contribute significantly to improving population health.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed as part of the current study are not publicly available because of confidentiality agreements with subjects. However, they can be made available solely for review and not for publication by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Pedrosa, A. L. et al. Emotional, behavioral, and psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychol. 11, 566212 (2020).

Park, K. H., Kim, A. R., Yang, M. A., Lim, S. J. & Park, J. H. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the lifestyle, mental health, and quality of life of adults in South Korea. PLoS ONE 16(2 February), e0247970. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0247970 (2021).

Yamada, Y. et al. Regional difference in the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on domain-specific physical activity, sedentary behavior, sleeping time, and step count: Web-based cross-sectional nationwide survey and accelerometer-based observational study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 9(1), e39992 (2023).

Yuksel, D. et al. Sleeping when the world locks down: Correlates of sleep health during the COVID-19 pandemic across 59 countries. Sleep Health 7(2), 134–142 (2021).

Hale, L., Troxel, W. & Buysse, D. J. Sleep health: An opportunity for public health to address health equity. Annu. Rev. Public Health 41, 81–99. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040119-094412 (2020).

Van Cauter, E., Spiegel, K., Tasali, E. & Leproult, R. Metabolic consequences of sleep and sleep loss. Sleep Med. 9(Suppl 1), S23–S28 (2008).

Medic, G., Wille, M. & Hemels, M. E. H. Short- and long-term health consequences of sleep disruption. Nat. Sci. Sleep 9, 151 (2017).

Shankar, A., Sabanayagam, C. & Kalidindi, S. Sleep duration and self-rated health: The National Health Interview Survey 2008. Sleep 34(9), 1173–1177 (2011).

Szwarcwald, C. L. et al. Factors affecting Brazilians’ self-rated health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Cad Saude Publica 37(3), e00182720 (2021).

Wendt, A., Flores, T. R., Silva, I. C. M. & Wehrmeister, F. C. Association of physical activity with sleep health: A systematic review. Revista Brasileira de Atividade Física & Saúde 23, 1–26 (2019).

Hepsomali, P. & Groeger, J. A. Diet, sleep, and mental health: Insights from the uk biobank study. Nutrients 13(8), 2573 (2021).

Lemola, S., Räikkönen, K., Gomez, V. & Allemand, M. Optimism and self-esteem are related to sleep. Results from a large community-based sample. Int. J. Behav. Med. 20(4), 567–571. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-012-9272-z (2013).

Cislaghi, B. & Cislaghi, C. Self-rated health as a valid indicator for health-equity analyses: Evidence from the Italian health interview survey. BMC Public Health 19(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6839-5 (2019).

Andreasson, A., Axelsson, J., Bosch, J. A. & Balter, L. J. T. Poor sleep quality is associated with worse self-rated health in long sleep duration but not short sleep duration. Sleep Med. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2021.10.028 (2021).

Štefan, L., Sporiš, G. & Krističević, T. The associations between sleep duration and sleep quality with self-rated health in young adults: a population-based study. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health https://doi.org/10.1515/ijamh-2018-0007/html (2020).

Silva, P. L. D. N., Pessoa, D. G. C. & Lila, M. F. Análise estatística de dados da PNAD: incorporando a estrutura do plano amostral. Cien Saude Colet 7(4), 659–670 (2002).

Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Pesquisa de Orçamentos Familiares 2017–2018: Análise de consumo alimentar pessoal no Brasil (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística, 2020). http://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&btnG=Search&q=intitle:Pesquisa+de+Or?amentos+Familiares#0

Meireles, A. L., Xavier, C. C., Proietti, F. A. & Caiaffa, W. T. Influence of individual and socio-environmental factors on self-rated health in adolescents. Rev. Bras. Epidemiol. 18(3), 538–551 (2015).

Szwarcwald, C. L. et al. Pesquisa Nacional de Saúde no Brasil: concepção e metodologia de aplicação. Cien Saude Colet 19(2), 333–342 (2014).

Meireles, A. L., Machado-Coelho, G. L. L., Lourenção, L. G., Júnior, L. A. A. D. M. & Coletro, H. N. COVID-inconfidentes—SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence in two Brazilian urban areas during the pandemic first wave: Study protocol and initial results. Poblac Salud Mesoam (2023).

Buysse, D. J., Reynolds, C. F., Monk, T. H., Berman, S. R. & Kupfer, D. J. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 28(2), 193–213 (1989).

Sousa, T. V. et al. Reliability and validity of the Portuguese version of the generalized anxiety disorder (GAD-7) scale. Health Qual Life Outcomes 13(1), 1–8 (2015).

Santos, I. S. et al. Sensibilidade e especificidade do patient health questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) entre adultos da população geral. Cad Saude Publica 29(8), 1533–1543 (2013).

Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B. W. & Löwe, B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 166(10), 1092–1097 (2006).

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L. & Williams, J. B. W. The PHQ-9. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 16(9), 606–613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x (2001).

WHO. ATC/DDD classification (temporary) (WHO, 2019).

WHO. WHO Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour (World Health Organization, 2020).

Ku, P. W., Steptoe, A., Liao, Y., Hsueh, M. C. & Chen, L. J. A cut-off of daily sedentary time and all-cause mortality in adults: A meta-regression analysis involving more than 1 million participants. BMC Med. 16(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-018-1062-2 (2018).

Szwarcwald, C. L. & Damacena, G. N. Amostras complexas em inquéritos populacionais: planejamento e implicações na análise estatística dos dados. Rev. Bras. Epidemiol. 11(suppl 1), 38–45 (2008).

Cortes, T. R., Faerstein, E. & Struchiner, C. J. Use of causal diagrams in epidemiology: Application to a situation with confounding. Cad Saude Publica. 32(8), e00103115 (2016).

Breen, R., Karlson, K. B. & Holm, A. Total, direct, and indirect effects in logit and probit models. Sociol. Methods Res. 42(2), 164–191 (2013).

de Souza, L. F. F. et al. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic in the quality of sleep by Pittsburgh sleep quality index: A systematic review. Cien Saude Colet. 26(4), 1457–1466 (2021).

Asif, N., Iqbal, R. & Nazir, C. F. Human immune system during sleep. Am. J. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 6(6), 92–96 (2017).

Sun, X. et al. Sleep disturbance and psychiatric disorders: A bidirectional Mendelian randomisation study. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 31, e26 (2022).

Smith, K. J. & Victor, C. Typologies of loneliness, living alone and social isolation, and their associations with physical and mental health. Ageing Soc. 39(8), 1709–1730 (2019).

Baranwal, N., Yu, P. K. & Siegel, N. S. Sleep physiology, pathophysiology, and sleep hygiene. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 77, 59–69 (2023).

Fang, H., Tu, S., Sheng, J. & Shao, A. Depression in sleep disturbance: A review on a bidirectional relationship, mechanisms and treatment. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 23(4), 2324 (2019).

Oftedal, S. et al. Associations of health-behavior patterns, mental health and self-rated health. Prev. Med. 118, 295–303 (2019).

Carolina, B. et al. Age, skin color, self-rated health, and depression associated with co-occurrence of obesogenic behaviors in university students: A cross-sectional study. Sao Paulo Med. J. (2022). http://www.scielo.br/j/spmj/a/zr8MXWfCcbXdcmsTWjSNbRw/?lang=en

Zhu, Y. et al. Depression and anxiety mediate the association between sleep quality and self-rated health in healthcare students. Behav. Sci. 13(2), 82 (2023).

Östberg, D. & Nordin, S. Three-year prediction of depression and anxiety with a single self-rated health item. J. Ment. Health 31(3), 402–409. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2021.2022610 (2022).

McCarthy, E., DeViva, J. C., Southwick, S. M. & Pietrzak, R. H. Self-rated sleep quality predicts incident suicide ideation in US military veterans: Results from a 7-year, nationally representative, prospective cohort study. J. Sleep Res. 31(1), e13447. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsr.13447 (2022).

Miyah, Y., Benjelloun, M., Lairini, S. & Lahrichi, A. COVID-19 impact on public health, environment, human psychology, global socioeconomy, and education. Sci. World J. 2022, 5578284 (2022).

Kalmbach, D. A., Anderson, J. R. & Drake, C. L. The impact of stress on sleep: Pathogenic sleep reactivity as a vulnerability to insomnia and circadian disorders. J. Sleep Res. 27(6), e12710 (2018).

Davis, M. T., Holmes, S. E., Pietrzak, R. H. & Esterlis, I. Neurobiology of chronic stress-related psychiatric disorders: Evidence from molecular imaging studies. Chronic Stress 1, 2470547017710916 (2017).

Philippens, N., Janssen, E., Kremers, S. & Crutzen, R. Determinants of natural adult sleep: An umbrella review. PLoS ONE 17(11), e0277323 (2022).

Meyer, O. L., Castro-Schilo, L. & Aguilar-Gaxiola, S. Determinants of mental health and self-rated health: A model of socioeconomic status, neighborhood safety, and physical activity. Am. J. Public Health 104(9), 1734 (2014).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the support of the Federal University of Ouro Preto (UFOP) and the Research and Education Group in Nutrition and Collective Health (GPENSC) for their support and incentive, and also, the support of the Municipal Health Secretariats of the municipalities.

Funding

This study was supported by the Brazilian Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq), and Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel-Brazil (CAPES) 9/2020; nº88887.504994/2020e00] with finance code 001 for Ph.D. student scholarship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Luiz Antônio Alves de Menezes-Júnior—data collection, conception, and study design; analysis and interpretation of data; writing the manuscript, critical review, and final approval. Samara Silva de Moura—data collection, writing the manuscript, critical review, and final approval. George L. L. Machado-Coelho—conception and coordination of data collection, management of financial, critical review, supervision, and final approval. Adriana L. Meireles—conception and coordination of data collection, management of financial resources, interpretation of data, critical review, and final approval.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

All procedures were performed according to the Brazilian guidelines and standards for research involving human beings of the Declaration of Helsinki and were approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Federal University of Minas Gerais (Ethics Submission Certificate no. 32815620.0.1001.5149). This study followed reported guidelines dictated by the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE). Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants. For more details on data collection, see Meireles et al.20.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

de Menezes-Júnior, L.A.A., de Moura, S.S., Machado-Coelho, G.L.L. et al. How anxiety and depression mediate the link between sleep quality and health perception during crisis periods. Sci Rep 15, 12952 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98004-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98004-0