Abstract

The refrigeration performance of semiconductor refrigeration devices is limited by, among other things, the thermal conductivity of the materials. Optimisation of ceramic materials for semiconductor packaging offers the possibility of improving system performance. In this paper, a mathematical model of the semiconductor refrigeration process is established using the cooling capacity and the cooling coefficient as evaluation indexes. It investigates the effects of current, cold end temperature and hot end temperature on the cooling performance. A simulation model of laminated encapsulated materials is proposed to investigate the influence of the structure of encapsulated ceramic materials on the condensation effect. The results show that a small increase in current significantly increases the cooling capacity at low cold-end temperatures, while this effect diminishes at higher cold-end temperatures. An increase in the hot end temperature decreases the cooling capacity and coefficient, with the decrease being more pronounced at higher currents. In addition, as the thermal conductivity of the encapsulated ceramic material decreases along the direction perpendicular to the ceramic structure, heat transfer is directed more effectively, resulting in improved cooling efficiency and condensation. These findings provide new insights into the design of ceramic materials and optimisation of the efficiency of semiconductor cooling systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Semiconductor refrigeration technology, as a solid-state refrigeration method based on the Peltier effect, has been widely used in consumer electronics, communication equipment, laser temperature control, refrigeration and dehumidification in recent years1,2,3. It has become a powerful complement to traditional compressor refrigeration and adsorption refrigeration because of its frictionless, refrigerant-contamination-free, gas-emission-free, small mass-volume, and precise temperature control characteristics4. However, the refrigeration efficiency and performance of semiconductor refrigeration discs are affected by various factors, especially the thermophysical properties of the structural materials are crucial to the overall refrigeration effect5,6.

Materials can be classified into internal thermoelectric materials and external encapsulated materials. Thermoelectric materials possess high thermoelectricity, low thermal conductivity, and excellent mechanical stability, enabling efficient cooling and power generation functions under the thermoelectric effect5,7,8. Packaging materials are usually selected from ceramics, whose coefficient of thermal expansion should match that of the semiconductor material to reduce the failure of the cooling structure due to differences in thermal stress9. In addition, the electrical insulation properties of ceramic materials can effectively prevent short-circuit or current leakage, and mechanical protection properties to help resist external physical impact or environmental factors. More critically, the excellent thermal conductivity of ceramics facilitates the efficient transfer of heat, thereby improving the overall cooling efficiency of the system10,11. there have been a few studies to improve the cooling performance by optimizing thermoelectric materials12,13, including design, doping and structural optimization of the materials, especially to reduce the thermal conductivity and to increase the electrical conductivity and Seebeck coefficient14,15,16.

Dong, Zirui et al.17 investigated the thermoelectric properties of TiRu1−xSb (0.15 < x < 1.0) alloys and found that the thermoelectric properties of the materials were optimized by varying the ratio of Ti and Ru. TiRu₁0.8Sb alloys have a low lattice thermal conductivity at low temperatures, which makes it suitable for the application of for thermoelectric converters, Bing sheng et al.18 introduced Ni nanoparticles into Bi₂Te₂. ₇Se₀. ₃ material significantly improved its electrical conductivity and thermoelectric properties. The optimum addition of 0.4 mol % resulted in a ZT value of 0.66. Kong, Shuang et al.19 significantly improved the thermoelectric properties of MoS₂ by introducing MoO₂ nanoparticles into the material. The doped MoO₂ was able to increase the electrical conductivity and Seebeck coefficient of the material, while effectively suppressing the increase in lattice thermal conductivity, thus optimizing the cooling performance. For SnTe thermoelectric material, Liu, Zhi-Yuan et al.12 successfully reduced the lattice thermal conductivity of SnTe by doping Mg3.2Sb0.6Bi1.4 alloy nanoparticles while enhancing the electrical conductivity, which led to the optimization of its thermoelectric properties at high temperature. Mohammad, Ubaid et al.20, on the other hand, further improved the electron mobility and thermal conductivity of SnTe by doping multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs), which effectively enhanced the thermoelectric conversion efficiency and provided new ideas and directions for the design of high-efficiency thermoelectric materials.

For the structural design of thermoelectric materials, scholars Han, Young Shang21 designed soft-structured thermoelectric devices with high stretchability (up to 230%) using 3D printing technology. The design combines functional composites with self-healing liquid metal conductors, which are suitable for efficient thermoelectric conversion in complex environments and optimizes the cooling performance. Spann, Bryan T22 found that quantum effects (e.g., electron tunnelling and confinement effects) can significantly reduce the irreversible energy loss due to electron transport by introducing in homogeneously doped nanomaterials; this discovery contributes to the improvement of thermoelectric cooling efficiency of chillers and promotes the application of quantum effects in thermoelectric.

In summary, the research on thermoelectric materials in improving semiconductor cooling efficiency is relatively mature, and the optimization of traditional thermoelectric materials has reached a high level. Therefore, the improvement of refrigeration efficiency purely from the perspective of thermoelectric materials has appeared to be very limited8,23,24. The thermal conductivity of semiconductor ceramic materials determines the efficiency of heat transfer, and the reasonable selection of ceramic materials and their arrangement can effectively regulate the heat flow path and reduce the thermal resistance, thus improving the performance of semiconductor refrigeration, so the role of thermal management of ceramic materials should not be ignored25,26,27. Currently, the study of the effect of encapsulated ceramic materials on the condensation effect in the semiconductor refrigeration process is still a key problem to be solved28,29.

This paper establishes a mathematical model of the semiconductor refrigeration system, takes the refrigeration capacity and refrigeration performance as the evaluation index, and studies the influence of current, cold end temperature and hot end temperature on the refrigeration performance. On this basis, three ceramic materials are selected, six different laminated ceramic material structures are designed, and the refrigeration effect of these laminated materials under different current and temperature conditions is analyzed by numerical simulation to obtain the optimal laminated structure ceramic materials. It is hoped to provide theoretical support for optimizing the efficiency of semiconductor refrigeration as well as shortening the development cycle of semiconductor refrigeration systems.

Semiconductor refrigeration theory model and refrigeration parameter impact analysis

Peltier effect and refrigeration mechanism in semiconductor thermoelectric materials

The principle of semiconductor refrigeration is based on the Peltier effect, the core mechanism of which is the change of electron energy levels30. Figure 1a demonstrates the absorption and release of energy in the process of electron leaps; when an electron leaps from a high energy level to a low energy level, it releases energy, leading to an increase in the temperature of the surrounding environment; conversely, when an electron leaps from a low energy level to a high energy level, it absorbs the external energy, leading to a decrease in the temperature of the environment; Fig. 1b further illustrates the process of the energy level change of the electrons in the connection of different thermoelectric materials. Based on this phenomenon, semiconductor refrigeration technology was born31,32,33. Figure 1c then demonstrates the basic working principal structure of semiconductor refrigeration.

However, the refrigeration power of a single semiconductor material is small, so multiple semiconductors are usually used in parallel to form a refrigeration wafer to achieve greater refrigeration power34,35,36, as shown in Fig. 1d. In addition to the Peltier effect, the temperature difference in the refrigeration process leads to the thermoelectric effect, which is manifested as the See Beck effect, i.e., the formation of electric potential between conductors of different temperatures. In addition, Joule heat is generated when a current passes through a conductor due to electrical resistance; as well as additional heat-absorbing or exothermic Thomson effect due to Fourier heat flow in the conductor caused by temperature gradients32,37,38.

Theoretical modelling

Figure 2 shows the theoretical modelling object of the semiconductor refrigeration system studied in this paper, where Fig. 2a represents the basic principle of the refrigeration process and Fig. 2b shows the schematic structure of the thermoelectric material. In addition, the Thomson effect as a secondary effect will not be considered in this study.

From the literature39,40 the energy released or absorbed by the Peltier effect Calculation formula can be expressed as:

where \(\tau_{12}\) is the relative Peltier coefficient of the two thermoelectric materials; \(I\) is the current flowing through the semiconductor.

According to the Kelvin relation there is:

where, \(\alpha_{12} = \alpha_{1} - \alpha_{2}\) is the relative Seebeck coefficient; \(T_{*}\) is the contact point temperature.

The Seebeck coefficient can be given by Eq. (3):

where \(\Delta T\) is the temperature difference between the hot and cold ends; \(\Delta U\) is the potential difference between the thermoelectric materials.

According to formula (3) can be tested and calculated respectively N-type semiconductors, P-type semiconductors and copper Seebeck coefficient, \(\alpha_{N}\), \(\alpha_{P}\) and \(\alpha_{{C{\text{u}}}}\); Copper is a metallic material with a negligible Seebeck coefficient.

Joule heat for the current through the resistance when the heat generated, that is:

where \(R\) is the resistance; can be found from Eq. (5).

\(\sigma\) is the resistivity; \(L\) is the length of the thermoelectric material; \(A\) is the cross-sectional area; the semiconductor length and area are shown schematically in Fig. 2b.

Joining Eqs. (4) and (5) gives:

Fourier heat Can be given according to Eq. (7):

\(T_{h}\), \(T_{c}\) are the hot-end and cold-end temperatures of the semiconductor, respectively; \(\lambda\) is the thermal conductivity; and \(K_{h} = \frac{\lambda A}{L}\) is the thermal conductivity.

When the current flows as shown in Fig. 2a, the top side of the semiconductor absorbs heat for cooling and the bottom side dissipates heat. And when the thermoelectric is in equilibrium, half of the Joule heat will flow into the cold side31,41. According to the first law of thermodynamics, the temperature of the hot end \(T_{h}\), the amount of heat released \(Q_{h}\), the temperature of the cool end \(T_{c}\), the amount of heat absorbed \(Q_{c}\), the power consumed by the semiconductor \(P\), and the current in the circuit \(I\) are related as follows:

Joining the above equations gives:

where \(R_{o}\) is the total thermal resistance; \(K_{o}\) is the total thermal conductance; respectively:

From the above, the semiconductor power \(P\) can be obtained:

Refrigeration coefficient \(\varepsilon_{c}\) (the coefficient of cooling(COP))is the key index for evaluating the refrigeration performance, which can be known according to the above formula and relevant definition:

Parameter influence analysis

To investigate the influence of key parameters such as current, cold end temperature and hot end temperature on the refrigeration performance, the physical model of semiconductor refrigeration in Fig. 3 is used as a research object. Figure 3a is a cross-section of the semiconductor refrigeration structure, Fig. 3b is the principal diagram of the semiconductor refrigeration system, and Fig. 3c is the schematic diagram of the overall structure of semiconductor refrigeration. The thermoelectric material parameters of the PN-type semiconductor in the model are given by Table 1.

Effect of current on semiconductor cooling performance

At a temperature difference of 10 K, Fig. 4 gives the changing law of semiconductor cooling capacity and cooling coefficient with current at different cold end temperatures.

From Fig. 4, the cooling capacity of the semiconductor increases linearly at different cold-end temperatures as the current increases. However, for lower cold end temperatures, the rate of increase in cooling capacity is significantly greater than that for higher cold end temperatures, which indicates that the increase in current has a more significant effect on the cooling capacity at lower cold end temperatures.

On the other hand, the refrigeration coefficient shows a tendency to increase and then decrease with increasing current. Specifically, the refrigeration coefficient first rises rapidly when the current is increased and reaches its maximum value at about 1.8A current, and then gradually decreases. This phenomenon indicates that although increasing the current can effectively increase the cooling capacity, the cooling coefficient starts to decrease when the current is greater than a certain threshold, resulting in a decrease in the cooling efficiency and an increase in the energy consumption of the system. Therefore, when optimizing the cooling capacity, it is necessary to consider the changes in the refrigeration coefficient in order to avoid a decrease in system efficiency due to too high a current.

Effect of cold end temperature on semiconductor refrigeration performance

When the hot end temperature is 303 K, Fig. 5 gives the change rule of semiconductor refrigeration capacity and refrigeration coefficient with the cold end temperature under the action of different currents.

As can be seen from Fig. 5, when the current is kept constant, the semiconductor refrigeration capacity increases linearly with the cold end temperature. Under different current conditions, the cooling capacity increases with the cold end temperature, and the higher the current, the higher the cooling capacity, which is in line with the law that the cooling capacity changes with the current. In addition, the increase of the cooling capacity under different currents is small and the rate of increase is similar, which indicates that the effect of the cold end temperature on the cooling capacity is relatively weak.

Regarding the refrigeration coefficient, the refrigeration coefficient gradually increases as the temperature of the cold end increases, and the refrigeration coefficient is higher in the higher current condition than in the lower current condition. This may be since the current range is at a stage where the refrigeration coefficient increases with increasing current. In addition, when the cold end temperature reaches about 305 K, there is a sharp reversal of the cooling coefficient from a positive value to a negative value. This indicates that the cold end temperature may have exceeded the hot end temperature, i.e., the direction of the current has reversed, causing the cold end to become a heat source and the hot end to become a cold source.

Effect of hot end temperature on semiconductor refrigeration performance

When the cold end temperature is 275 K, Fig. 6 gives the semiconductor refrigeration capacity and refrigeration coefficient change rule with the hot end under the action of different currents.

It can be seen from Fig. 6, the cooling capacity increases as the current increases, in line with the positive correlation between the current and the cooling capacity. However, under the condition of constant current, the cooling capacity decreases linearly with the increase of temperature at the hot end. This indicates that when the temperature of the hot end increases due to insufficient heat dissipation, it leads to a decrease in the cooling capacity of the semiconductor.

On the other hand, the cooling coefficient decreases more significantly with increasing hot end temperature, and the higher the current, the faster the cooling coefficient decreases. This indicates that a higher hot end temperature will lead to a significant reduction in the thermoelectric conversion efficiency, resulting in a waste of power in the system. Therefore, in the design and operation of semiconductor refrigeration systems, measures should be taken to control the hot end temperature to avoid the high temperature leading to system performance degradation and energy consumption increase.

Encapsulated ceramic material structure combination mode on the impact of refrigeration performance research

Encapsulated ceramic laminated material structure

Figure 7 shows a semiconductor refrigeration model with an encapsulated ceramic structure partially divided into three layers, each layer being a different ceramic material. Three ceramic materials, beryllium oxide, 99% alumina and aluminum nitride, were selected as the matrix materials and their respective parameters are shown in Table 2. For the convenience of the study A, B and C are used to represent BeO, Al₂O₃ and AlN, and there are six kinds of laminated ceramic refrigeration structures composed, which are denoted by a, b, c, d, e and f, respectively. The simulations in this study were performed in the steady state thermal module under ANSYS WORKBENCH 2022R1.

Model validation

Accuracy and correctness are the key indicators to assess the accuracy and reliability of the simulation model. For this reason, grid independence validation and correctness validation are carried out for this model respectively. For accuracy, this paper takes the minimum temperature of the refrigeration structure and the maximum temperature of the condenser cooler as the evaluation index and uses three sets of grid systems to verify the model accuracy, and the results are shown in Table 3. The results are shown in Table 3. As shown in Table 3, the relative errors of the minimum temperature of the refrigeration structure are 0.037% and 0.48%, and the relative errors of the maximum temperature of the condenser cooler are 0.016% and 0.11%, which are not more than 1%, and the accuracy of the model is in accordance with the requirements.

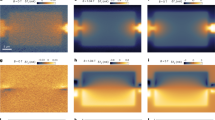

To ensure the accuracy of the model, this study investigates temperature distribution as the primary evaluation metric. Through theoretical calculations and simulations under identical settings, we systematically analyze the thermal behavior of a copper alloy with constant thermal conductivity, as well as aluminum alloy, Inconel718, and AlSi10Mg, whose thermal conductivities vary with temperature. The temperature variations at different positions are examined under boundary conditions of 500 °C and 30 °C. Figure 8a–d compare theoretical and simulation results for a material length of 1 m. The findings indicate that for materials with constant thermal conductivity, temperature distributions are nearly identical across positions. In contrast, for materials with temperature-dependent thermal conductivity, slight discrepancies exist between theoretical and simulated values, with a maximum error of only 0.72% (AlSi10Mg; position: 0.005 m; theoretical value: 498.89 °C; simulated value: 497.59 °C).

Furthermore, Fig. 8e–h illustrate the comparison between theoretical and simulated values at the microscale (millimeter level). The results show that when the thermal conductivity remains constant, theoretical calculations and simulations yield identical results. For materials with temperature-dependent thermal conductivity, the maximum discrepancy remains at 0.72% (AlSi10Mg; position: 0.005 mm; theoretical value: 498.89 °C; simulated value: 497.59 °C). This demonstrates that, regardless of whether at the macroscale or microscale, the discrepancies between theoretical and simulation results for all materials are minimal, with a maximum relative error of only 0.72% (AlSi10Mg). This further confirms the high degree of agreement between simulation and theoretical results.

Additionally, for the same material at different lengths (1 m and 1 mm), the theoretical and simulated values exhibit negligible differences, indicating that material length has an insignificant effect on the simulation results. Consequently, it can be concluded that the adopted simulation method possesses high accuracy and reliability.

Results and discussion

To study the influence of the structure of the encapsulated ceramic material on the refrigeration effect, the surface temperature of the condensing structure is used as an evaluation index. Figure 9 shows the distribution of the surface temperature of the condensing structure corresponding to six different laminated ceramic material structures when the cooling capacity is 44.5 W. The lowest temperature is in the connection area with the thermoelectric material, and the temperature is gradually radiated outwards from this point. The lowest temperature is in the connection area with the thermoelectric material, and with this point as the center, the temperature gradually increases radially outwards.

Figure 10 shows the values of the minimum temperature (Min T), the maximum temperature (Max T) and the temperature difference (TD) on the surface of the condensing structure under different laminating modes at a cooling capacity of 44.5 W. From Fig. 10, it can be seen that when the ceramic structural materials are laminated in mode b, the surface temperature of the condensing structure reaches the maximum temperature, the minimum temperature and the maximum temperature difference, with the maximum temperature of − 1.8 °C, the minimum temperature of − 4.6 °C and the maximum temperature difference was 2.8 °C, indicating that the combination of encapsulated ceramics in manner b enables the condensing structure to achieve the best cooling effect at the same cooling capacity.

Using the minimum temperature as a judgement indicator, the condensing efficiency of mode b is improved by 6.8 per cent, 5.1 per cent, 4.9 per cent, 7 per cent and 6 per cent compared with modes a, c, d, e and f, respectively, and its overall cooling effect is b > d > c > f > e > a.

Using the temperature difference as a judgement indicator, the refrigeration effect is b > e > c > f > a > e. However, although the minimum temperature of mode a differs from mode e by only 0.2%, the difference in temperature is 0.46%, and the effect of the temperature difference on the refrigeration efficiency is much more significant. As a result, the laminated structure of mode a is the worst in terms of condensation effect, while mode b performs the best.

Compared to composites a, c, d, e, and f, the thermal conductivity of composite b gradually increases along the direction perpendicular to the laminate structure, i.e., the thermal resistance ‘damping’ gets smaller and smaller as the heat ‘slides’ along the direction perpendicular to the laminate structure, which might be the the reason why composite b is more effective. This may be the reason why composite b is more effective.

The opposite order of composite structure b is composite structure d, but d does not show a similar or opposite behaviour to that of b. The thermal conductivity of composite b is not the reason for the more significant effect of composite b. It is assumed that the thermal conductivity is not the only factor affecting the efficiency of heat transfer, but it may be related to the effect of temperature on the thermal conductivity as well as the coefficient of thermal expansion of the material.

In summary, combining the thermal conductivity characteristics of the three ceramic materials, it can be inferred that when the thermal conductivity of the encapsulated ceramic material shows a gradual decrease in the nonlinear performance along the structural direction, its enhancement effect on the semiconductor condensation performance is better than that of the other encapsulated ceramic materials that show different nonlinear changes along the structural direction. The results make it clear that heat transfer can be guided more effectively when the thermal conductivity shows a gradually decreasing nonlinear variation along the structural direction.

Conclusion

In this paper, the influence of key parameters such as current, cold end temperature and hot end temperature on the efficiency of semiconductor refrigeration is firstly analyzed through theoretical models; subsequently, a numerical simulation model of semiconductor refrigeration is constructed to study the influence of the structural lamination of its encapsulated ceramic materials on the condensation effect, and the conclusions are as follows:

-

(1)

When the temperature of the cold end is low, a small increase in the current can significantly enhance the cooling capacity; while in the case of high temperature of the cold end, the enhancement effect of increasing the current on the cooling capacity tends to weaken.

-

(2)

As the hot end temperature increases, the cooling capacity gradually decreases; at the same time, the coefficient of cooling (COP) decreases more obviously, and the larger the current is, the faster the COP decreases. It shows that optimizing the heat dissipation design to reduce the hot end temperature is crucial for improving the cooling efficiency.

-

(3)

When the thermal conductivity of the encapsulated ceramic material is gradually reduced from the inside out along the structural direction, the heat transfer can be guided more efficiently, thus significantly improving the cooling efficiency and condensation effect.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Liu, Y. et al. Experimental research on the cooling effect of a novel two-phase closed thermosyphon with semiconductor refrigeration in permafrost regions. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csite.2023.103935 (2024).

Liu, Y. et al. Experimental research on a semiconductor freezer utilizing two-stage thermoelectric modules. Energy Convers. Manag. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2022.116471 (2022).

Wang, Y. et al. Performance of a fresh-food storage box based on semiconductor refrigeration. Sustain. Cities Soc. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2019.101599 (2019).

He, Y. et al. Investigations on coupling between performance and external operational conditions for a semiconductor refrigeration system. Int. J. Refrig. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrefrig.2019.09.021 (2020).

Mao, J., Chen, G. & Ren, Z. Thermoelectric cooling materials. Nat. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41563-020-00852-w (2020).

Qiu, P., Shi, X. & Chen, L. Cu-based thermoelectric materials. Energy Storage Mater. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ensm.2016.01.009 (2016).

Qiu, P. et al. Plastic inorganic thermoelectric materials. Joule https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joule.2023.12.020 (2024).

Yang, X. et al. Progress in measurement of thermoelectric properties of micro/nano thermoelectric materials: A critical review. Nano Energy https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nanoen.2022.107553 (2022).

Roy, S., Nagel, A. & Weidenmann, K. A. Anisotropic thermal expansion behavior of an interpenetrating metal/ceramic composite. Thermochim. Acta https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tca.2019.178488 (2020).

Lakhdar, Y. et al. Additive manufacturing of advanced ceramic materials. Prog. Mater. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmatsci.2020.100736 (2021).

Li, K. et al. Normalized evaluation of thermal shock resistance for ceramic materials. J. Adv. Ceram. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40145-014-0118-9 (2014).

Liu, Z.-Y. et al. A review of CoSb 3 -based skutterudite thermoelectric materials. J. Adv. Ceram. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40145-020-0407-4 (2020).

Shakouri, A. Recent developments in semiconductor thermoelectric physics and materials. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-matsci-062910-100445 (2011).

Abbasi, M. S. et al. Contemporary advances in organic thermoelectric materials: Fundamentals, properties, optimization strategies, and applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2024.114579 (2024).

Ponnusamy, P. et al. Efficiency as a performance metric for material optimization in thermoelectric generators. J. Phys. Energy https://doi.org/10.1088/2515-7655/ac293e (2021).

Zhu, W. et al. Enhanced thermoelectric performance through optimizing structure of anionic framework in AgCuTe-based materials. Chem. Eng. J. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2019.123917 (2019).

Dong, Z. et al. Half-Heusler-like compounds with wide continuous compositions and tunable p- to n-type semiconducting thermoelectrics. Nat. Commun. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-27795-3 (2022).

Du, B. et al. Spark plasma sintered bulk nanocomposites of Bi2Te2.7Se0.3 nanoplates incorporated Ni nanoparticles with enhanced thermoelectric performance. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.9b08392 (2019).

Kong, S. et al. Dramatically enhanced thermoelectric performance of MoS2 by introducing MoO2 nanoinclusions†. J. Mater. Chem. A https://doi.org/10.1039/c6ta10219k (2016).

Mohammad, U. et al. Antibonding valence states induce low lattice thermal conductivity in metal halide semiconductors. Appl. Phys. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0227080 (2024).

Han, Y., Tetik, H. & Malakooti, M. H. 3D soft architectures for stretchable thermoelectric wearables with electrical self-healing and damage tolerance. Adv. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202407073 (2024).

Spann, B. T. et al. Semiconductor thermal and electrical properties decoupled by localized phonon resonances. Adv. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202209779 (2023).

Giulia, P. Thermoelectric materials: The power of pores. Nat. Rev. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1038/natrevmats.2017.6 (2017).

Liu, W. & Bai, S. Thermoelectric interface materials: A perspective to the challenge of thermoelectric power generation module. J. Materiomics https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmat.2019.04.004 (2019).

Chalamala, B. Prolog to the section on advanced materials for electronics, photonics, and energy storage. Proc. IEEE https://doi.org/10.1109/jproc.2012.2190685 (2012).

Mailman, A. et al. The power of packing: Metallization of an organic semiconductor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.6b12814 (2017).

Mukhopadhyay, A. et al. Laser-tuned surface wettability modification and incorporation of aluminum nitride (AlN) ceramics in thermal management devices. Adv. Funct. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202313141 (2024).

Nuñez Lobato, C. et al. How efficient are thermoelectric materials?—An assessment of state-of-the-art individual and segmented thermoelectric materials. Mater. Today Energy https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtener.2024.101564 (2024).

Zhang, A. & Wang, B. Temperature and electric potential fields of an interface crack in a layered thermoelectric or metal/thermoelectric material. Int. J. Therm. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijthermalsci.2016.01.023 (2016).

Grocholski, B. Thrifty thermoelectric cooling. Science https://doi.org/10.1126/science.365.6452.458-b (2019).

Flipse, J. et al. Direct observation of the spin-dependent Peltier effect. Nat. Nanotechnol. https://doi.org/10.1038/nnano.2012.2 (2012).

Uchida, K.-I. et al. Observation of anisotropic magneto-Peltier effect in nickel. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0143-x (2018).

Zhou, H. et al. Direct conversion of phase-transition entropy into electrochemical thermopower and the Peltier effect. Adv. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202303341 (2023).

Alam, N. et al. Experimental investigation and analysis of cooling performance of solar thermoelectric refrigerator. Sol. Energy https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2023.111892 (2023).

Dino, G. E. et al. Experimental characterization of an innovative hybrid thermal-electric chiller for industrial cooling and refrigeration application. Appl. Energy https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2020.116098 (2020).

Su, Y. et al. Free-standing planar thermoelectric microrefrigerators based on nano-grained SiGe thin films for on-chip refrigeration. Nano Energy https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nanoen.2018.03.054 (2018).

Cui, L. et al. Peltier cooling in molecular junctions. Nat. Nanotechnol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41565-017-0020-z (2017).

Hao, J. et al. Optimal flow layout and current allocation for improving the thermoelectric refrigeration system based on heat current method. Int. J. Energy Res. https://doi.org/10.1002/er.7347 (2021).

Brestovič, T. et al. Measuring of thermal characteristics for Peltier thermopile using calorimetric method. Measurement https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2014.03.021 (2014).

Wang, L. et al. Ultra-efficient and thermally-controlled atmospheric structure deicing strategy based on the Peltier effect. Appl. Therm. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2024.123162 (2024).

Amagai, Y. et al. Precision ratiometric technique for measuring the Peltier coefficient. Measurement https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2023.114002 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Key Research and Development Program of Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region (2023BCF01047), ‘Optimal Design and Demonstration of Key Technologies for Large-scale, Low-energy-consuming Agricultural Facilities on Non-cultivated Land’ (2023-2025).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.Y. contributed to the conceptualization, methodology, software development, and writing of the original draft. Q.Z. conducted the investigation. F.W. performed the formal analysis. Y.B. was responsible for validation. T.L. worked on visualization. W.G. provided supervision, managed data curation, and secured funding. C.Z. contributed to reviewing and editing the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yan, S., Zhao, Q., Wang, F. et al. Optimization mechanism of laminated ceramic package structure on the regulation of semiconductor cooling performance. Sci Rep 15, 14634 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98104-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98104-x