Abstract

This paper investigates the performance mechanisms of system bolts in China’s first four-track high-speed railway (HSR) tunnels, specifically the XBS tunnels, with spans ranging from 25.93 to 27.12 m and depths of 7 to 53 m. First, a theoretical framework, referred to as the deformation pressure theory arch, is introduced to elucidate the role of bolts throughout the sequential construction phases of four-track HSR tunnels. Subsequently, the effectiveness of system bolts is examined through an eight-month field investigation, and the relative functional partitioning for the tunnels is established. Three optimization schemes are then proposed, and their effects are analyzed using numerical simulations. The results indicate that the tunnel with a depth ranging from αh1c to αh2c represents a transition from deep-buried, small cross-sectional pilot tunnels to shallow-buried, super-large-span cavities. The function of system bolts can be categorized into stitching and anchoring based on the deformation pressure arch. The mechanisms of rock bolts in shallow four-track HSR tunnels can be summarized as ‘anchor first, then stitch; anchor in deep state while stitch in shallow state’. The implementation of the long-short combined scheme reduces the axial force and deformation in Class V rock conditions by 74.15% to 80.04% and 41.91%, respectively. Scheme 3 is recommended for Class V rock, while Scheme 1 is proposed for alternative scenarios.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As a central pillar of contemporary transportation infrastructure, the construction velocity and scope of high-speed rail (HSR) systems persistently escalate1. Tunnels, as a fundamental element of high-speed rail (HSR) corridors, encounter a myriad of technical challenges during their construction, serving as an irreplaceable constituent of the overall HSR framework2. In comparison to conventional high-speed rail (HSR) tunnels, shallow four-track HSR tunnels pose significantly greater design challenges and construction complexities3. Serving as a pivotal component of the support structure, the system bolts are instrumental in safeguarding the integrity and safety of the tunnel. Consequently, conducting research on the mechanisms underlying the bolt system and its optimization design is not only pivotal for enhancing the safety of tunnel structures but also crucial for improving the overall reliability and performance of HSR lines.

As of now, the application of rock bolts in mountainous tunnels remains a subject of considerable debate. On one hand, certain scholars have proposed the removal of system bolts from mountainous tunnels, citing their limited effectiveness. For example, Chen et al.4 performed field tests in the Baojiashan Tunnel and found that the removal of system bolts did not significantly affect tunnel safety. Furthermore, Tan et al.5 indicated that tunnel deformation remained unaffected in deeply buried tunnels following the application of rock bolts. In diluvial clay tunnels, Yang et al.6 observed that rock pressure, vault settlement, and horizontal convergence exhibited minimal variations following the application of system bolts, concluding that the removal of anchor bolts would not jeopardize the structural integrity of the tunnel. Conversely, a growing body of research has been dedicated to validating the efficacy of rock bolts in mountainous tunnels. LeeInMo and Shin7 investigated the seepage forces on grouted bolts and observed that grouted bolts are more advantageous under seepage conditions. Using the ANSYS method, Muya et al.8 demonstrated that stress concentrations could be mitigated with the application of rock bolts, particularly under high ground stress conditions. In loess tunnels, Yan et al.9 suggested that rock bolts offer resistance to expansion forces, thereby enhancing tunnel stability upon their application.

At present, the primary point of contention surrounding rock bolts in shallow mountainous tunnels lies in whether the bolt length can effectively penetrate the loosened zone. Proponents of removing system bolts contend that, following tunnel excavation, a loosened zone forms in the surrounding rock, causing the tunnel support to bear loosening pressure, thereby hindering the penetration of system bolts into this zone, as illustrated in Fig. 1a. However, with the advancements in tunnel construction technologies—particularly the use of rock bolts, shotcrete, large-scale mechanized construction, and monitoring equipment—the disturbances during tunnel construction have been significantly minimized and controlled within acceptable limits10,11. In modern mountainous tunnels, rock pressure has shifted from loosening pressure to deformation pressure, as depicted in Fig. 1b. Scholars, including Wang et.al12 and Wang13, have indicated that tunnels constructed with modern technologies bear the load resulting from the deformation of the surrounding rock, known as deformation pressure. A central objective of contemporary tunnel technology is to effectively manage the load borne during the deformation pressure phase14. Consequently, the alteration in the type of surrounding rock pressure borne by the tunnel implies a corresponding shift in the mechanism of rock bolt action. However, despite Chinese mountain tunnels adhering to the New Austrian Tunneling Method (NATM)15, tunnel support design continues to be predominantly based on the loosening pressure theory. Engineering analogies remain the most frequently employed approach in tunnel design5. Greater emphasis must be placed on deformation pressure theory in tunnel design, particularly in the design of rock bolts. However, few studies have explored the relationship between bolt effectiveness and deformation pressure theory, with existing research predominantly relying on the loosening pressure model. Furthermore, research on rock bolts in shallow-buried, four-track high-speed rail (HSR) tunnels remains limited; both the pressure-type theory and the performance and effectiveness of rock bolts in such tunnels remain largely unexplored.

This paper thus investigates the mechanism of system bolts in shallow-buried, four-track high-speed rail (HSR) tunnels, grounded in the deformation pressure theory. First, a theoretical framework for rock bolts, grounded in deformation pressure theory, was developed. Subsequently, the effectiveness of rock bolts was validated through an eight-month field monitoring campaign conducted in the XBS tunnels. Following this, the functional partitioning of rock bolts in shallow four-track HSR tunnels was proposed. Finally, the optimization effects of various schemes were proposed and assessed through numerical simulations. The findings of this study provide valuable insights that can serve as a key reference for the design and construction of four-track HSR tunnels.

Engineering background

China’s first four-track HSR tunnel

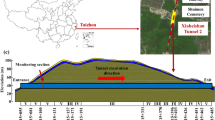

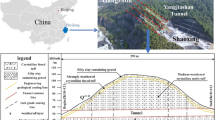

The XBS Tunnels of the Hangzhou-Shaoxing-Taizhou (HST) HSR are situated to the north of the Jiaojiang Bridge and in close proximity to Taizhou Railway Station to the south, as depicted in Fig. 2a. Given the convergence of train lines near the station, the tunnels were designed as a single-arch, four-track structure—representing the first of its kind for an HSR tunnel in China. The two central tracks are dedicated to the HSR lines, while the outer tracks are reserved for passenger-dedicated services. Designed to accommodate a maximum operational speed of 350 km/h, the XBS tunnel comprises of Tunnel No. 1 and Tunnel No. 2, with respective lengths of 166 and 430 m. Featuring a span ranging from 25.93 to 27.12 m and a burial depth of 7 to 53 m, encompasses an excavation area of 338.60 to 360 m2. Its span substantially exceeds the range defined by Chinese tunnel standards16, classifying it as a rare example of a super-large-span tunnel, as illustrated in Fig. 2b.

Drawing from established standards and analogous cases, a composite lining system with dual-layer primary support and a secondary lining was employed for the XBS tunnel: (1) The first layer of primary support is composed of C30 shotcrete reinforced with 4.0 kg/m3 of fiber, along with prestressed I32 self-drilling anchors. Additionally, it incorporates I18, I20b, and I22b steel frames, along with I6 steel mesh. (2) The second layer of primary support consists of C30 steel-fiber shotcrete, reinforced steel grids, and I6 steel mesh. (3) The secondary lining is composed of C40 reinforced concrete with HRB300/HRB400 steel reinforcement. The design parameters of system bolts for the XBS tunnels are detailed in Table 1.

Given the considerable volume of excavation, ensuring construction safety and stability while adhering to the project schedule was of utmost importance. Furthermore, the tunnel construction was strategically planned to accommodate subsequent work on the Jiaojiang Bridge. To meet these objectives, the tunnel employed the double side-drift method, with an ‘outside first, center later’ excavation sequence. The scheme for one section of the tunnel is illustrated in Fig. 2c. Considering the oversized cross-section of the four-track HSR tunnel, different parts within the cross-section have been named, as illustrated in Fig. 3.

Geological conditions

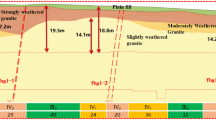

Figure 4 depicts the geological conditions of the XBS tunnels. The mountain is predominantly covered by a 2–4 m thick layer of silty clay residual soil. The surrounding rock of the XBS tunnels comprises relatively stable, weathered tuff layers. No unstable geological structures, such as folds or fault zones, have been identified within the rock layers. Groundwater primarily consists of bedrock fissure water, predominantly distributed within the joints, structural fracture zones, and weathered fissures of the tuff. The fissure water exhibits poor interconnection and is primarily unevenly distributed. Atmospheric precipitation primarily drains from the area via surface runoff, rendering it a region with relatively limited groundwater resources. The entrance of the XBS Tunnels traverses silty clay and tuff, which are characterized by well-developed joints and fissures, resulting in highly fragmented rock masses classified as Class V rock. The main tunnel body predominantly passes through tuff, with the rock primarily classified as Classes III, IV, and V16, as shown in Fig. 4b–d. The physical and mechanical parameters17,18,19 of rocks and supports were obtained through field sampling and laboratory testing, as illustrated in Fig. 5 and detailed in Table 2.

Rock bolt functions based on the deformation pressure theory

Deformation pressure arch

In this paper, the ratio of deformation pressure qd to the total rock pressure qall is defined as the deformation pressure coefficient kd, as presented in Eq. (1). In loosening pressure theory, ql is considered equal to qall, thereby enabling kd to be expressed as the ratio of qd to ql.

M.M, Protodyakonov’s theory20 suggests that the disturbance caused by excavation exerts a limited effect on the surrounding rock. The progressive failure model tests (as illustrated in Fig. 6) and the composite rock theory proposed by Zhang and Chen21 have substantiated this phenomenon. Furthermore, the implementation of support structures effectively confines the disturbed rock to a defined zone around the tunnel. Therefore, it is assumed that the deformation pressure is influenced exclusively by the rock within this specific disturbed zone. A virtual arch is assumed to bear the pressure from the rock beyond the disturbance range, while the deformation pressure value reflects solely the self-weight of the rock within the disturbed zone. As illustrated in Fig. 7, this virtual arch is referred to as the deformation arch, and its height can be derived from the deformation pressure coefficient kd, expressed as:

Stress characteristics of four-track HSR tunnels construction

Firstly, the sequential construction of four-track HSR tunnels, with a depth ranging from αh1c to αh2c, involves a transition from deep-buried, small cross-sectional pilot tunnels to shallow-buried, super-large-span cavities, as illustrated in Figs. 8 and 9. Moreover, the quality requirements for HSR tunnels are considerably more stringent than those for conventional mountain tunnel. Liu et al.22 suggested that, during the construction phase, the primary support bears the rock load of four-track HSR tunnels, whereas the secondary lining functions as a safety reserve. It is conceivable that the rock load borne by shallow-buried four-track HSR tunnels has transitioned to deformation pressure.

Functional analysis of bolt based on deformation pressure theory

According to rock bearing load theory, the mechanism of rock bolts can be described as follows: (1) the anchoring effect; (2) the stitching effect. Let La represent the bolt length, Hli denote the height of the loosened pressure arch at step i, and Hdi signify the height of the virtual deformation pressure arch at step i. The index i corresponds to the four construction states: i = 1, 2, 3, 4 for the construction of left pilot tunnel, right side tunnel, central tunnel, and the removal of temporary supports, as depicted in Fig. 10.

When the length of the rock bolt, La, exceeds the height of the deformation pressure arch, Hdi, the bolt performs both anchoring and stitching functions. Conversely, when the length of the rock bolt is shorter than the height of the deformation pressure arch, it primarily provides stitching support. Therefore, the function of rock bolts in shallow-buried four-track HSR tunnels, with a depth ranging from αh1c to αh2c, can be summarized as follows: In states 1 to 3, the construction of four-track HSR tunnels is characterized as deeply buried tunnels, i.e., La > Hdi > Hli, where both anchoring and stitching functions of rock bolts are performed. In state 4, when the super-large-span tunnel is deeply buried, i.e., La > Hdi > Hli, both anchoring and stitching function of rock bolts are performed; conversely, when the super-large span tunnel is shallowly buried, only the stitching functions of rock bolts are performed. Furthermore, if both a fault and a loosening zone appear at shallow depths (less than αh1c), the tunnel will experience loosening pressure. In such cases, the approach presented in this study may not suffice. More robust support measures would be necessary to constrain rock deformation, such as increasing the shotcrete thickness or reinforcing the arch support structure.

Effectiveness validation of rock bolts in four-track HSR tunnels

Monitoring systems and schemes

A comprehensive on-site testing campaign spanning eight months was conducted to assess the axial forces acting on the rock bolts within the XBS Tunnel. The axial forces were measured by using a rock bolt load cell (XYJ-2 Vibrating String Stress Meter) possessing a measurement range of 100 kN and an accuracy of ± 0.1% of the full scale (F.S.). Prior to shipment, the sensor underwent calibration, and the corresponding calibration table was provided for reference. Six measurement points were strategically positioned along each individual rock bolt, with a spacing of 1.2 m, as depicted in Fig. 11a and b. Seven measurement lines, labeled MG-1 through MG-7, were established within each testing section, as shown in Fig. 11c. The on-site installation process of the rock bolts within the XBS Tunnel is depicted in Fig. 11d. During on-site monitoring, the stress variations of the anchor bolts are measured periodically based on the stability of the surrounding rock. The axial force of the anchor bolts is then obtained by multiplying the bolt’s cross-sectional area by the measured stress.

Bolt axial forces analysis of field tests

The distribution of rock bolt axial force a shallow-buried four-track HSR tunnel is analyzed, as shown in Fig. 12, using the mileage of DK215 + 105 as an example. Positive values indicate tension, while negative values indicate compression. Generally, the axial forces of the rock bolts increase as construction process. In state 1, for instance, the axial forces at MG-1 are in compression, reaching a minimum value of − 0.31 kN, while at MG-2, the axial forces are in tension, with a maximum value of 3.42 kN. As construction advances, the axial forces at MG-1 and MG-2 increase to − 0.87 and 10.20 kN, respectively, in state 2. Meanwhile, the maximum axial forces at MG-3 and MG-4 are recorded at 12.70 kN and − 1.24 kN, respectively. In state 3, the axial forces at MG-1, MG-2, MG-3, and MG-4 increase to − 1.82 kN, 10.65 kN, − 2.10 kN, and 15.64 kN, respectively. The axial forces at MG-5, MG-6, and MG-7 are all positive, with maximum values of 7.36 kN, 3.00 kN, and 2.65 kN, respectively. In the final state, the axial forces in the rock bolts stabilize, with the distribution of maximum axial forces as follows: arch waist > vault > wall waist.

Moreover, no significant deformation occurred in the rock mass (the tunnels with a depth ranging from αh1c to αh2c), and no incidents of block detachment or collapse were observed during the construction. The rock mass exhibited no discernible signs of loosening, with only minimal deformation occurring. Based on the test results of rock bolt axial forces, it can be concluded that, the XBS tunnel with a depth ranging from αh1c to αh2c is subjected to deformation pressure rather than loosening pressure under the current support. However, should faults and loosened zones occur simultaneously at shallow depths (less than αh1c), the tunnel would experience loosening pressure. In such cases, the proposed solutions in this study may prove insufficient to ensure structural stability. Enhanced support measures would be required to mitigate the deformation of the surrounding rock, such as increasing the thickness of the shotcrete or strengthening the arch framework.

The maximum axial forces of system bolts in Class IV and V rocks are summarized in Fig. 13. Overall, the MG-1 and MG-3 bolts are all in compression, while those in other parts are in tension. During the pilot tunnel construction, rock removal causes deformation of the rock toward the tunnel centerline, particularly in the upper part, which may loosen open joints and lead to signs of loosening and deformation in unopened joints and cause signs of loosening and deformation in unopened joints, as shown in Fig. 14a. In this scenario, rock bolts, in conjunction with shotcrete, help anchor the rock mass exhibiting deformation tendencies, thereby contributing to the tunnel’s stability. However, the anchoring behavior of rock bolts is less evident at the vault of the shallow four-track HSR tunnel, which is why the axial forces at MG-5, MG-6, and MG-7 are lower than those at MG-2 and MG-4. This phenomenon occurs because the rock mass subsidence occurs during the middle pilot tunnel construction, as depicted in Fig. 14b, the rock length La is lower than the rock deformation range Lr. Although deformation differences between the head and end of rock bolts may generate rock force, the axial forces at the vault are much lower than those at the arch. In this state, rock bolts could perform its stitching function to loosen rocks, thereby promote the formation of bearing arch, and finally result in the stability of tunnel structures. Additionally, all rock bolts of MG-1 and MG-3 are in compression, with a maximum axial force of -5.32 and − 4.32 kN in class IV and V rocks, respectively. A tendency for the tunnel cavity to flatten has consistently been observed during the construction of super-large-span tunnels, indicating that the rocks at the wall waist and wall foot are in compression. This phenomenon is the primary cause of the negative axial forces recorded at the MG-1 and MG-3 rock bolts.

It is also noteworthy that, although MG-5 and MG-7 are symmetrically positioned, there is a significant difference in the axial forces on their respective rock bolts. This discrepancy primarily stems from the construction sequence and the corresponding disturbances. Specifically, MG-5 was installed before MG-7 during tunnel construction, meaning it began to experience deformation alongside the surrounding rock earlier than MG-7. Consequently, the amount of deformation restrained by MG-5 was greater than that experienced by MG-7. As a result, despite the bolts being symmetrically positioned, the axial force in MG-5 is substantially higher than that in MG-7. Furthermore, the distribution of axial force in the bolts is influenced by various factors, including geological conditions, on-site construction practices, the quality of fieldwork, and the temporary removal of support structures, all of which are not perfectly symmetrical. As a result, construction disturbances in the left and right pilot tunnels were not perfectly symmetrical, leading to significant differences in the axial forces recorded for bolts MG-5 and MG-7.

Bolt functional partitioning

Based on field investigations of the XBS tunnels, three action zones for rock bolts in shallow four-track HSR tunnels are defined: the anchoring zone, stitching zone, and ineffective zone (compressed zone), as shown in Fig. 14. Considering the construction characteristics of shallow four-track HSR tunnels, rock bolts initially function an anchoring function in the pilot tunnel state (i.e., deep tunnel state), and then exhibit stitching functions in the super-large-span tunnel state (i.e., shallow tunnel state). In the ineffective zones, rock bolts exhibit limited effectiveness for anchoring or stitching rocks, and it is recommended to eliminate the use of bolts in these areas. In summary, the mechanism response of rock bolts in shallow four-track HSR tunnels can be described as: ‘anchor first, then stitch; anchor in the deep stage, stitch in the shallow stage.’

Optimization of rock bolts in four-track HSR Tunnels

Optimization schemes

Three specific optimization schemes have been developed for the XBS tunnels (Fig. 15), as follows:

-

(1)

Scheme 1: Eliminate system bolts in the ineffective zones;

-

(2)

Scheme 2: Eliminate system bolts in the ineffective zones and replace bolts with cables in the stitching zones;

-

(3)

Scheme 3: Eliminate system bolts in the ineffective zones and adopt a combined layout of cables and bolts in the stitching zones, with alternating spacing between bolts and cables, referred to as the long-short combined scheme.

As shown in Fig. 16, the optimization effects of three rock bolts schemes were explored using the Finite Element Method (FEM) in this study. Abaqus (version 2022) was employed as the primary numerical simulation software. The accuracy of the numerical model has been validated in reference23. The bolts are modeled using wire elements. It is assumed that the rock mass adheres to the Mohr–Coulomb (MC) constitutive model, and the primary support and secondary lining are simulated by elastic models using solid elements. The bolt parameters are derived from actual site data, as presented in Table 3. The main assumptions made in the numerical model are as follows:

-

(1)

The materials in the model are assumed to be homogeneous and isotropic.

-

(2)

The surface soil layer is excluded from the model, focusing solely on the tuff.

-

(3)

The model omits the mountain terrain, simplifying the complex boundary conditions into a cubic representation.

Optimization effect analysis of rock bolts

Axial force analysis

Figure 17 presents the axial forces of bolts (and cables) after application of the optimization schemes, using State 4 as an example. In general, for the original scheme and Schemes 1 and 2, the maximum axial forces of rock bolts in Class III and IV rocks were observed at the vault. However, for Class V rock, these forces found at the arch waist. In Scheme 3 (i.e., the long-short combined scheme), the maximum axial force at the vault for Class III and IV rocks remains consistent with the other schemes. However, for Class V rock, the maximum axial force shift to the vault in Scheme 3, unlike in the other schemes.

Figure 18 presents the maximum axial forces on rock bolts for different design schemes, with the reductions achieved by the optimization schemes compared to the original scheme listed in Table 4. For Class III rocks, the values are relatively consistent: 24.29 kN for the original scheme, 24.30 kN for Scheme 1, and 24.27 kN for Scheme 3. Similarly, Class IV rocks show minimal variations, with the original scheme at 41.85 kN, Scheme 1 at 41.86 kN, Scheme 2 at 41.94 kN, and Scheme 3 at 41.91 kN. These results suggest that the modifications in Schemes 1 and 3 have negligible impact on axial force performance for Classes III and IV rocks. In contrast, Class V rock shows a significant difference, particularly in Scheme 3, where the maximum axial force is only 40.45 kN, making an 80.04% reduction compared to 202.7 kN in the original scheme. In summary, the results of Scheme 1 indicate that removing bolts in ineffective zone has little impact on axial force performance. Scheme 2, which involves simply increasing the length of bolts in the stitching zone, does not lead to noticeable changes in axial forces. However, the long-short combined scheme (Scheme 3) demonstrates that a combination of long and short anchors effectively optimizes rock loading, improving the overall performance of the anchoring system.

Tunnel deformation analysis

Figure 19 illustrates the tunnel deformation of shallow four-track tunnels after applying optimization schemes, using State 4 as an example. Figure 20 presents the maximum tunnel deformation across different rock grades and design schemes, with the reductions achieved by the optimization schemes compared to the original scheme listed in Table 5. For Class III and IV rocks, the maximum deformations remain relatively consistent across all schemes, suggesting that the design changes have minimal impact in these cases. Specifically, the deformation values for Class III rocks range from 9.08 mm to 9.099 mm, and for Class IV rocks, from 17.06 mm to 17.14 mm. However, Class V rocks show significant variation, especially with Scheme 3, which results a markedly lower maximum deformation of 25.78 mm, representing a 41.91% reduction compared to the original scheme (44.38 mm). This indicates that the long-short combined scheme (Scheme 3) may be more effective in managing tunnel deformation in weak rock conditions. Overall, the results from Scheme 1 suggests that the removing bolts in the ineffective zone is a feasible approach. In Scheme 2, merely increasing the length of bolts in the stitching zone does not result in noticeable changes in tunnel deformations. Conversely, Scheme 3 (the long-short combined scheme) demonstrates that using a combination of long and short anchors in Class V rocks effectively optimizes rock loading, thereby reducing tunnel deformations.

Optimization effect analysis

Based on the analysis of bolt axial forces and tunnel deformation, the optimization effects of Schemes 1 and 2 for the four-track HSR tunnel are limited across Class III, IV, and V rock masses. However, the long-short combined scheme (Scheme 3) shows only marginal benefits in Class III and IV rocks but demonstrates significant improvements in Class V rock. Specifically, Scheme 3 leads to a more uniform distribution of axial forces, with notable reductions in both maximum axial force and vault settlement. Therefore, for Class V rock, Scheme 3 (the long-short combined approach) is recommended, which involves removing bolts in ineffective zones and using a combination of cable bolts and conventional bolts in stitching zones. For all other cases, Scheme 1 is recommended.

Mechanism of long-short combined bolting system

As illustrated in Fig. 21, the mechanism of the long-short combined bolting system24,25 in the four-track HSR tunnel can be summarized as follows:

-

(1)

Long bolts/cables can penetrate the entire deformation zone, anchoring the loosened rock mass to the deeper rock layers. This enables the bolting system in the stitching zone to provide both stitching and anchoring functions, effectively controlling rock mass deformation and preventing damage.

-

(2)

Long bolts/cables extend the load-bearing arch deeper into the surrounding rock, preserving and utilizing the load-bearing capacity of the deep rock mass. Alternatively, they can collaborate with the shallow load-bearing arch, creating both shallow and deep load-bearing arches. In the event of shallow load-bearing arch failure, the deep load-bearing arch can anchor the loosened rock mass, ensuring the stability of the rock mass.

-

(3)

Long bolts/cables can transfer the rock pressure from the shallow load-bearing arch to the deeper rock, thereby reducing the pressure on both the shallow load-bearing arch and the support structure. Additionally, the long bolts/cables function as radial supports for the primary lining, effectively reducing the span of the structure, and improving the stress distribution.

Conclusion

This study investigates the mechanisms and optimization of system bolts in shallow four-track HSR. By integrating deformation pressure theory, field data, and numerical simulations, the research identifies critical design considerations and practical solutions for enhancing tunnel stability and performance. The key conclusions are as follows:

-

(1)

The transition from deep-buried, small cross-sectional pilot tunnels to shallow-buried, super-large-span tunnels presents unique challenges for shallow four-track tunnels with a depth ranging from αh1c to αh2c. The functions of system bolts can be classified into two categories—stitching and anchoring—based on the deformation pressure arch.

-

(2)

Three action zones for rock bolts are defined for shallow four-track HSR tunnels: the anchoring zone, stitching zone, and ineffective zone. The rock bolt mechanism in shallow four-track tunnels can be summarized as ‘anchor first, then stitch; anchor in the deep state, and stitch in the shallow state.’

-

(3)

The long-short combined scheme demonstrates a reduction of up to 80.04% in axial force and a 41.91% decrease in deformation under Class V rock conditions, highlighting its effectiveness in stabilizing shallow four-track tunnels.

-

(4)

This research provides valuable insights into the support design of shallow-buried tunnels and presents effective solutions to improve tunnel stability. Future work should focus on refining deformation pressure models and exploring materials and techniques for enhanced tunnel support.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Hanley, D., Li, J. & Wu, M. High-speed railways and collaborative innovation. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 93, 103717 (2022).

Gong, J. et al. Statistics of China′s railway tunnels by the end of 2023 and overview of tunnels of key new projects in 2023. Tunnel Const. 44(2), 377–392 (2024).

Ma, J. et al. Research and optimization of tunnel construction scheme for super-large span high-speed railway tunnel in poor tuff strata. Appl. Rheol. https://doi.org/10.1515/arh-2023-0101 (2023).

Chen, J. et al. Field test research on elimination of systematic rock bolts in weak rock tunnel. Rock Soil Mech. 32(1), 15–20 (2011).

Tan, Z.-S. et al. Experimental study on bolt effect on large section shallow depth loess tunnels. Yantu Lixue/Rock Soil Mech. 29(2), 491–495 (2008).

Yang, Y. et al. Research on the effect of systematic bolts in diluvial clay of estern extra-long highway tunnel. Tumu Gongcheng Xuebao/China Civ. Eng. J. 50, 127–133 (2017).

Mo, L. & Shin, J.-H. Behavior of grouted bolts in consider of seepage forces. J. Korean Tunnel. Underground Space Assoc. 7(3), 209–218 (2005).

Muya, M. S. et al. Effects of rock bolting on stress distribution around tunnel using the elastoplastic model. J. China Univ. Geosci. 17(4), 337 (2006).

Yan, Q. et al. Analytical solution for bolted tunnels in expansive loess using the convergence-confinement method. Int. J. Geomech. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)GM.1943-5622.0000989 (2018).

Wu, K. et al. Analytical approach to estimating the influence of shotcrete hardening property on tunnel response. J. Eng. Mech. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)EM.1943-7889.0002052 (2022).

Liu, C. et al. Interaction analysis between composite supports and rheological rock considering progressive hardening characteristic of shotcrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 374, 130876 (2023).

Wang, M.-N. et al. Method for calculating deformation pressure of surrounding rock of deep-buried tunnels. Yantu Gongcheng Xuebao/Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 42(1), 81–90 (2020).

Wang, J. Innovative concepts in conventional tunnelling (China Communications Press Co., Ltd., 2021).

Wang, M. et al. Calculation method of deformation load of deep-buried tunnel under influence of excavation method. J. Southwest Jiaotong Univ. 56(5), 1116–1124 (2021).

Rabcewicz, L. V. The new Austrian tunnelling method. Water Power 17, 453–457 (1964).

China, R.T.S.o.t.P.s.R.o., Code for design of railway tunnel: TB 10003—2016. 2017, Beijing China Railway Publishing House.

Sonmez, H. & Ulusay, R. Modifications to the geological strength index (GSI) and their applicability to stability of slopes. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 36(6), 743–760 (1999).

Hoek, E. & Brown, E. T. Practical estimates of rock mass strength. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 34(8), 1165–1186 (1997).

Cai, M. et al. Estimation of rock mass deformation modulus and strength of jointed hard rock masses using the GSI system. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 41(1), 3–19 (2004).

Hu, J. et al. Improved protodyakonov’s method of the tunnel surrounding rock pressure under the seepage condition of weak interlayer. Geofluids 2022, 1–14 (2022).

Zhang, D. & Chen, L. Compound structural characteristics and load effect of tunnel surrounding rock. Yanshilixue Yu Gongcheng Xuebao/Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 35(3), 456–469 (2016).

Liu, X. et al. Mechanical characteristics of primary support system at construction phase in shallow-buried super-large-span four-line high-speed railway tunnel. Zhongguo Tiedao Kexue/China Railway Sci. 42(6), 90–102 (2021).

He, S. et al. Mechanical behavior of anchor bolts for shallow super-large-span tunnels in weak rock mass. Materials 16(17), 5862 (2023).

Luo, J. et al. Analytical study on pretensioned bolt-cable combined support of large cross-section tunnel. Sci. China-Technol. Sci. 63(9), 1808–1823 (2020).

Luo, J. et al. Numerical modelling and field monitoring study on large-span tunnelling using pretensioned bolt-cable combined support system. Tunnell. Underground Space Technol. 132, 104911 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The author thanks the financial support from the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities + 2024YJS043.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

*Shaohui He:Methodology, Data curation, Visualization, Writing—original draft,Funding acquisition. Jianfei Ma: Writing—review and editing, Supervision, Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition. Jiaxin He: Methodology, Field test. Xiabing Liu: Investigation, Field test.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ma, J., He, S., Liu, X. et al. Mechanisms and optimization of system bolts in shallow four-track HSR tunnels based on deformation pressure theory. Sci Rep 15, 13650 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98108-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98108-7