Abstract

Crossbreeding is a cornerstone of modern livestock improvement, combining desirable traits to enhance productivity and environmental resilience. This study conducts the first comprehensive genomic analysis of Red Angus × Chinese Red Steppe (RACS) crossbred cattle, evaluating their genetic architecture, diversity, and selection signatures relative to founder breeds (Red Angus and Chinese Red Steppe) and global populations. A total of 119 cattle, comprising 104 RACS crossbreds and 15 Chinese Red Steppes cattle, were genotyped using the GGP Bovine 100k SNP array. Additionally, the public available genotypic data generated using the BovineSNP50 chip from 550 animals across eight beef breeds (Angus, Hereford, Limousin, Charolais, Mongolian, Shorthorn, Red Angus, and Simmental) and one dairy breed (Holstein) were incorporated into the analysis. We aimed to (1) define the population structure of RACS cattle, (2) quantify their genomic diversity and inbreeding levels, and (3) pinpoint regions under selection linked to adaptive and economic traits. We employed runs of homozygosity (ROH) and population differentiation (Fst) analyses to detect selection signals. The results revealed that the crossbred (RACS), Angus, and Red Angus breeds exhibited similar clustering patterns in principal component analysis (PCA), but the crossbred population showed the highest nucleotide diversity and lowest inbreeding coefficients compared to other breeds. Notably, candidate regions associated with immune response, cold adaptation, and carcass traits were identified within the RACS population. These findings enhance our understanding of the genetic makeup of crossbred beef cattle and highlight their potential for genetic improvement, informing future selection and breeding strategies aimed at optimizing beef production in challenging environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The enhancement of quantitative traits in beef cattle can be achieved through two primary genetic methods: selection within breeds and crossbreeding between breeds. Traits critical to beef production, such as calf survivability, reproductive efficiency, and environmental adaptability, often exhibit low heritability1,2. In such cases, crossbreeding emerges as a more effective approach, leveraging heterosis (hybrid vigor) to amplify productivity. crossbreeding programs can enhance productivity traits by up to 26% compared to purebred systems, a benefit attributed to the synergistic combination of complementary alleles from divergent parent breeds3. Genetic research has consistently highlighted the advantages of crossbreeding in enhancing desirable traits such as growth rate, feed efficiency, and meat quality4,5. For example, Brahman × Angus hybrids exhibit pronounced hybrid vigor, improving growth, carcass quality, disease resistance, and thermotolerance6. Advances in genomic tools now enable deeper insights: whole-genome resequencing of Heilongjiang Crossbred cattle identified functional genes linked to meat quality and reproduction7, while analyses of the Purun composite breed revealed genetic ties among founder breeds and loci governing heat-tolerance, growth and meat quality traits8.

However, crossbreeding outcomes are context-dependent, shaped by ecological and economic priorities. Crossbreeding indigenous cattle with commercial breeds in China, is a prevalent strategy to enhance productivity while preserving their unique adaptive traits9,10. The country’s rich genetic diversity, spanning over 53 native cattle breeds, provides valuable insights into genes associated with adaptation to varying climates11,12,13. Among these, Mongolian cattle stand out for their hardiness in extreme environments14,15, while Chinese Red Steppe (CRS) cattle, developed by crossing Mongolian cows with Shorthorn bulls16, are valued for their disease resistance, stress tolerance, cold climate adaptation, high-quality meat and milk production9,17. To further improve the meat quality and growth rate of CRS, breeders initiated a program crossing CRS with Red Angus (RACS), a well-known commercial breed for marbling and rapid growth traits, creating the Red Angus × Chinese Red Steppe (RACS) hybrid. This hybrid uniquely merges commercial productivity (Red Angus) with indigenous resilience (CRS), making RACS an ideal model to study how divergent genetic lineages interact. By analyzing RACS’s genomic architecture, our study explores how strategic crossbreeding can balance productivity and adaptation, a critical consideration for sustainable livestock systems.

Advances in WGS (whole genome sequencing) technology and genotyping platforms, decreasing the cost of sequencing, along with the appearance of a variety of statistical methods, have effectively helped to trace genomic regions and genes that were subject to selection in indigenous18, commercial and composite19 beef cattle. Different analytical methods have been developed based on the signal or pattern they capture. For instance, Fst and ROH are two widely used statistics that detect genetic signatures through allelic frequencies and haplotypes, respectively20,21,22,23. Fst is effective for identifying selection signatures between populations with unequal sample sizes24. In the other hand, ROH are consecutive homozygous segments across the genome, which are inherited from both parents to the offspring’s genome25. Shared regions of homozygosity (ROH islands) that occur with greater frequency in a population may indicate signs of selection associated with adaptability and economically important traits22,26. Additionally, the characteristics and abundance of ROH across chromosomes have extensively been investigated in farm animals to figure out the demographic history and estimate the genome-wide inbreeding27,28,29.

While crossbreeding in cattle has been extensively researched, the genetic architecture underlying the Red Angus × Chinese Red Steppe (RACS) hybrid remains poorly characterized. Although hybrid vigor and beneficial phenotypic traits in other crossbred populations are well-documented4,5, genomic mechanisms specific to RACS, particularly those driving its unique adaptability and productivity, have yet to be explored. This study investigates the genetic foundations of the RACS crossbreed to elucidate the functional outcomes of hybridization and identify genomic regions under selection. Using population genomics approaches, we map patterns of genetic divergence, assess diversity metrics, and pinpoint loci linked to critical traits such as disease resistance, environmental resilience, growth, and carcass quality. By addressing these knowledge gaps, our findings aim to advance precision breeding frameworks that optimize both productivity and sustainability in livestock systems, offering actionable insights for agricultural adaptation in diverse ecological contexts.

Results

Population genetic structure

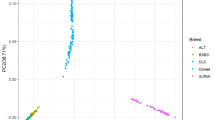

Figure1 illustrates the genetic differentiation between the cattle populations. The first PC1 accounted for 5.74% of the variation and distinguished the dairy commercial breed (Holstein) from the other cattle breeds. The RACS crossbred population constituted a cluster in the left corner of the graph that overlapped with ANG and RAN, and situated near SHO and explained 4.55% of the total variation. The CRS and MON populations grouped together in the center, while SIM (Simmental), CHL (Charolais), HFD (Herford) and LMS (Limousine) were positioned in proximate clusters.

The results of population admixture analysis using different values of K (1 to 11) and cross-validation error plot are presented in Fig. 1. In the current study, the CV errors decreased with increasing k value, hence it is not easy to determine the appropriate number of the assumed ancestral population. However, the scrutiny of the plots of PCA, admixture and CV errors demonstrates that the most likely partition for populations is at k = 7. The RACS crossbred was mixed with its parents ANG, RAN, CRS and MON when K = 7. From k = 5 to k = 10, the SHO population was separated from the others.

Genomic diversity

Runs of homozygosity

As shown in Fig. 2 (A), the CRS and then RACS crossbred populations harbored the lowest average number (36 and 88, respectively) and coverage of ROH per animal (101.098 and 265.813 Mb, respectively). The highest average number (214) and coverage (731.519 Mb) of ROH were indicated in the SHO breed. The frequency of ROH segments with a length of 1–2 Mb was higher than other length categories in all studied populations. The MON population followed by the CRS population exhibited the highest percentage of short ROHs (between 1 and 2 Mb) at 81.5% and 78%, respectively, while the SHO population had the lowest percentage at 43.4%. The RACS crossbred population showed a median proportion of shortest ROHs. The longest segments of ROH (> 16 Mb) had the lowest frequency in all breeds. The highest proportion of ROHs longer than 16 Mb belonged to CRS (2.9%) followed by HFD (2.2), HOL (1.6), and RACS (1.5) (Table 1; Fig. 2A).

Nucleotide diversity and inbreeding coefficients

The RACS and CRS populations demonstrated the highest average nucleotide diversity (0.436 ± 0.024 and 0.418 ± 0.017, respectively), while that of the HFD and SHO breeds had the lowest values (0.367 ± 0.048 and 0.369 ± 0.023, respectively) (Fig. 2B).

Genomic inbreeding values (mean, lowest, and highest) estimated using four different approaches are shown in Table 2. The RACS population exhibited the lowest inbreeding coefficients across all ten beef and one dairy cattle breeds using three methods (FGRM, FHOM, and FUNI), However, when using the FROH method, the CRS population exhibited the lowest inbreeding coefficient, followed by RACS. In RACS, FGRM (average of -0.047), FHOM (average of -0.047), and FUNI (average of -0.047) values ranged from 0.019 to 0.232, -0.203-0.268, -0.143-0.081, and − 0.133–0.169, respectively. Since different estimators have different characteristics, the estimated value of the inbreeding coefficient based on FROH is between 0 and 1, and FUNI, FGRM, and FHOM estimators can take negative30,31. In the estimates based on FGRM, FHOM, and FUNI, the highest inbreeding value (0.088) was observed in the HFD breed, and for FROH, the SHO breed was indicated to be the highest (0.292). While FGRM and FUNI inbreeding coefficients exhibited a strong positive correlation in most breeds (Table S2), FROH generally showed weak, often negative, correlations with other methods. In RACS, the highest and lowest correlation was computed between FGRM and FUNI (0.953), and FHOM and FROH (0.048), respectively.

Linkage disequilibrium and effective population size

Across all populations, the LD decay analysis revealed a decrease in the average r2 values as the distance between SNPs increased (Fig. 2C). On average, the estimated LD values ranged from 0.39 (MON) to 1 (SHO) at a distance of 1000 bp between markers. The RACS crossbred represented a decreasing trend almost similar to HOL. Notably, the CRS population exhibited a sharp decline in LD values as the SNP distance increased up to 40 kb (0.188). Overall, CRS and MON displayed the lowest LD values, while RACS showed moderate values, with r2 values of 0.75 and 0.13 at 1 and 200 kb, respectively.

All breeds exhibited a declining trend in effective population size (Ne) over generations, as depicted in Fig. 2D. Notably, the MON breed, initially displaying the highest Ne, experienced a sharp decline in recent generations. Over the past 15 generations, RACS crossbreds showed higher Ne than RAN and CRS. While CRS initially had a higher Ne than RACS, its Ne has decreased more rapidly.

The distribution of the average ROH number in different length categories, the colors represent the ROH lengths in Mb (A). A display of the nucleotide diversity per breed, a horizontal line drawn in the box denotes the median (B), genome-wide average LD decay estimated from each breed (C), the effective size of eleven populations over past generations (D).

Signatures of selection

We defined an ROH as an island when the SNPs within a run were observed in more than 45% of the population (Fig. 3). As shown in Table S3, the highest and lowest ROH islands numbers belonged to SHO (189 islands), and MON (one island), respectively. The SHO breed exhibited the longest ROH island, spanning 16 Mb on Bos Taurus Autosome (BTA) 3, and also contained the highest number of SNPs within ROH islands, with 105 SNPs on this chromosome. There were 8 ROH islands on BTA 2, 5, 9, 10, 13, 15, 20, and 21 in the RACS breed, which largest ROH island was on BTA5 between 75,585,421 and 76,993,652 kb (39 SNP). This region contains SYT10, ELFN2, MFNG, CARD10, USP18, ALG10, C1QTNF6, SSTR3, RAC2, CYTH4 genes. Two ROH islands were identified in the CRS breed, located on BTA 7 and 21. These islands harbor genes such as NDN, MAGEL2, and MKRN3.

A list of candidate genes identified in ROH islands is depicted in Table S4. Of the 259 ROH islands identified in all breeds, only 79 islands spanning a minimum number of 15 markers were taken into account to detect candidate genes (Table S4). In summary, 2150 genes were identified in ROH regions, including 1710 protein-coding genes and 441 genes of the other types (lncRNA, miRNA, misc_RNA, pseudogene, snoRNA, and snRNA). These genes participated in 52 GO terms (21 biological processes, and 31 molecular functions) across all breeds (Table S5).

Of the 101 genes identified in RACS, 5 biological processes (BP) and 11 molecular functions (MF) were enriched. These included peptidyl-arginine modification (GO:0018195), granulocyte chemotaxis (GO:0071621), and folic acid receptor activity (GO:0061714).

Tables S6 and S7 list the genes and GO terms identified within the candidate selection regions, as determined by the Fst analysis. A total of 508 protein-coding genes and 16 GO terms (BP = 24, MF = 25, CC = 14) were detected in the Fst analysis of RACS vs. SRS, MON, ANG, RAN, SHO. Some terms contained defense response to protozoan (GO:0042832), defense response to Gram-positive bacterium ( GO:0050830), chemokine-mediated signaling pathway (GO:0070098) and glucose 6-phosphate metabolic process (GO:0051156). The Fst analysis revealed a strong signal on bovine chromosome 13 (BTA13) in the RAN breeds (mFst = 0.80), encompassing the ASXL1 gene (Fig. 4). This signal was also observed in ANG and SHO breeds. Furthermore, the NOL4L and NFIA genes were identified in the analysis comparing RACS to ANG, SHO, and RAN. In the genetic differentiation analysis between RACS and MON, SHO, and CRS, we identified three genes of interest: NPAS3, SEMA3E, and FUT9.

Discussion

Exotic breeds have been utilized in crossbreeding programs to enhance the productive traits of indigenous breeds. This approach not only boosts the productivity of native livestock but also helps preserve their unique characteristics, such as disease resistance and adaptability to harsh environmental conditions10. In other words, high-yielding and well-adapted synthetic breeds can be developed through crossbreeding. The current study is the first to investigate the genomic characteristics of the RACS crossbreds. Admixture analysis revealed substructures among RAN, ANG, CRS, and MON within the RACS cluster at K = 7. Overall, the population structure analysis indicated that the RACS crossbred has a closer genetic relationship with RAN than with CRS as the parent breeds. This aligns with the fact that since 1997, the CRS breed has been continuously crossed with RAN, resulting in a significant genetic contribution from RAN in the crossbreds. Additionally, because of the involvement of the SHO and MON breeds in the crossing program of the CRS, they are genetically closer to the RACS compared to other breeds.

All studied populations exhibited a steep decline in effective population size in recent generations. Over the past 15 generations, however, the RACS crossbred population maintained a moderately higher Ne than its founder breeds, RAN and CRS. Despite this advantage, the Ne observed in RACS remains lower than that of the Purunã composite breed, a population with a longer history of inbreeding and genetic management8. Notably, RACS also displayed a smaller Ne compared to several purebred breeds studied, consistent with trends observed in other composite populations32. While hybridization initially boosted diversity, the RACS population likely originated from a limited number of founding individuals, creating a bottleneck that restricted the effective contribution of parental genomes. Over generations, artificial selection for traits such as growth, marbling, and environmental resilience may have further narrowed the genetic pool by favoring specific alleles, reducing the number of reproductively influential individuals. Additionally, continuous backcrossing with RAN since 1997 skewed genetic contributions toward one parent breed, diminishing the effective input from CRS and ancestral populations like Mongolian cattle. Although nucleotide diversity captures the broad genetic variation inherited from divergent founder breeds, Ne is more sensitive to recent demographic events, such as selection pressures and breeding strategies, which amplify homozygosity and linkage disequilibrium (LD)33,34. Despite this, RACS exceeded the FAO’s Ne threshold (≥ 50) to mitigate inbreeding risks35. Consistent with Ne trends, RACS exhibited significantly lower LD and higher heterozygosity than its founder breed RAN, indicating enhanced genetic diversity and recombination efficiency. This contrasts with Xia’nan crossbred cattle, where hybrids displayed higher LD than their parental Charolais breed36. Reduced LD in RACS mitigates inbreeding risks and amplifies heterosis potential by diminishing haplotype fixation.

The extent and length of continuous homozygous segments over the genome (i.e., ROH) depend on various factors including, demographic events, selection pressures, population effective size, and inbreeding37,38. In other words, ROH distribution is non-random on the genome and is more prevalent in regions with low recombination and higher LD29. Most of the detected ROHs (43–81%) across populations were short segments (1–2 Mb). A similar pattern was observed in previous studies in cattle22,39,40. This likely reflects ancestral relationships and more ancient inbreeding41,42.

In composite populations, a low ROH count is crucial as the level of heterosis diminishes with a rise in ROH occurrence43. Notably, RACS crossbred cattle exhibited the lowest average ROH quantities per animal compared to purebreds, aligning with trends in composite populations44,45. Admixed populations, due to their divergent ancestry across multiple lineages, inherently accumulate fewer ROH than their parental populations29. This trend was evident in RACS, where we observed a reduced proportion of ROH especially short ROH (1–4 Mb) segments relative to their founder breeds (CRS and RAN). Short ROHs are less likely to harbor severe recessive deleterious alleles due to the historical purging of highly harmful variants through selection46. However, these segments may retain mildly deleterious or neutral alleles. The low frequency of short ROH in RACS minimizes cumulative genetic load, enhancing overall fitness and productivity, while preserving adaptive potential through retained heterozygosity.

Inbreeding and its detrimental consequences, including the inbreeding depression for reproductive traits and fitness and a loss of genetic diversity, have underscored the importance of accurate inbreeding estimation in livestock47,48. Genomic inbreeding coefficients, particularly those based on runs of homozygosity (FROH), provide a more precise measure of autozygosity than pedigree-based methods30,49, which often fail to capture cryptic relatedness50. Unlike FGRM (derived from genomic relationship matrices), FHOM (measuring excess homozygosity), and FUNI (correlation of uniting gametes), FROH directly quantifies contiguous homozygous segments and is unaffected by allele frequency biases or population structure51. Additionally, FGRM, FUNI, and FROH can yield negative values and function more like correlation coefficients31, while FROH confined to a range of 0 to 1 and directly reflects autozygosity52. These methodological differences explain the observed discrepancies between FROH and other estimators. Notably, correlations among inbreeding estimators varied significantly. Consistent with previous studies8,48,51, FGRM and FUNI exhibited the strongest correlation, likely due to their shared emphasis on rare alleles in quantifying inbreeding30. Divergence in population-specific allele frequencies may further explain the variable correlations observed between FGRM, FUNI, and FHOM51. FROH displayed low or negative correlations with other estimators, aligning with recent reports53,54. This finding contrasts with studies that have documented moderate to high correlations in other populations55,56. These discrepancies highlight methodological dependencies; FROH is unaffected by allele frequencies but sensitive to the marker density and ROH detection parameters51. it has been shown that longer ROH segments are linked to stronger correlations between FROH and other inbreeding coefficients56,57, suggesting methodological considerations significantly influence outcomes. The observed negative correlations may reflect population-specific dynamics: elevated FROH values coupled with low inbreeding estimates from other metrics could signal localized selection pressures driving homozygosity at trait-associated loci without genome-wide increases in relatedness. In contrast, for example, FGRM’s reliance on allele frequencies enables it to capture shifts in genetic diversity across the entire genome, including variation unrelated to homozygosity (e.g., allele frequency drift)51.

Compared to purebred populations, RACS crossbred cattle showed the lowest inbreeding coefficients, reflecting their recent hybrid origin. This is supported by their higher nucleotide diversity than other populations studied. Moreover, their inbreeding coefficients were lower than those previously reported for Heilongjiang crossbred cattle7. The low inbreeding levels observed in the RACS population suggest a high level of genetic diversity, which is advantageous for maintaining population health and adaptability. This diversity can enhance traits such as fertility and disease resistance, contributing to the overall performance and sustainability of the cattle population. The crossbreeding strategy employed in RACS appears to be effective in introducing new genetic variations and reducing the likelihood of homozygosity for deleterious alleles, thereby minimizing inbreeding depression. Thus, while RACS cattle currently exhibit low inbreeding, continuous genomic monitoring is essential to maintain genetic health and sustainability. Future efforts should prioritize whole-genome sequencing and expanded datasets for crossbred populations. Refining ROH detection parameters and disentangling selection from drift will improve the inbreeding estimation accuracy, enabling nuanced assessments of genetic health in managed populations. Such advancements are essential to balance productivity and sustainability in modern breeding programs.

A key advantage of crossbreeding is breed complementarity, which involves combining desirable traits from founder breeds to create crossbred or composite animals with enhanced characteristics58. In the case of the RACS crossbred population, comparing it to its founder breeds, RAN (known for marbling and growth) and (CRS, valued for cold adaptation and disease resistance), offers critical insights. This comparison helps elucidate how crossbreeding reshapes genomic architecture to achieve a balance between productivity and environmental resilience, addressing a fundamental challenge in livestock breeding.

In recent years, scrutiny of the ROH region to identify footprints of selection has extensively been of interest to researchers21,27,59. While a significant correlation exists between contiguous homozygous stretches and candidate regions under selection60, interpreting ROH regions as definitive signatures of selection requires caution. Other evolutionary processes, such as genetic drift, population structure, and recombination rate, can also contribute to ROH patterns37,61,62.

In exploring ROH islands in the RACS breed, a 1.4 Mb island on BTA5, encompassing the highest SNP density, was identified. Within this region, ten candidate genes linked to marbling traits were discovered, including ELFN2, MFNG, CARD10, USP18, ALG10, and SYT1063, . This trait may have originated from the RAN parent breed. Genomic association studies indicate that the SYT10 and ALG10 genes are linked to longevity and stability traits across various cattle breeds. SYT10 is particularly important for the release of insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1), implying its contribution to longevity by influencing growth and reproductive efficiency64,65. The ROH island also includes immune-related genes critical for disease resistance. USP18 is crucial for the innate immune response and plays a significant role in defending against viral infections66,67. RAC2, encoding a Rho-family GTPase, enhances B-cell signaling and microbial phagocytosis in Holsteins68 and parasite resistance in sheep69,70. Similarly, the IL2RB, gene is known as a key immune factor in cattle71. IL2RB, essential for T-cell-mediated immunity and immune homeostasis, has been associated with disease progression in various species72,73. On BTA15, the IL18BP gene was identified, another gene associated with immune traits. IL-18 binding protein (IL-18BP) acts as a natural regulator of the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-18. Its role in immune modulation74 highlights applications in veterinary medicine. The identification of these genes suggests enhanced disease resilience in RACS cattle, likely inherited from the CRS parent9, aligning with their robust herd health and productivity.

Crossbreeding and combining the favorable genes of exotic and indigenous breeds leads to adapted cattle with better meat quality and production efficiency3,10. The CAMK1D gene was the only one identified as common between the ROH analysis of RACS and the Fst analysis comparing RACS and CRS. This gene plays a crucial role in various physiological processes that are vital for the development and productivity of cattle, including muscle and development growth75, heifer early calving until 30 months, and stayability76. This gene also influences immune system responses, enhancing the animal’s ability to cope with infections and diseases77,78. A recent study has shown that CAMK1D regulates feed consumption and obesity development in mice79, suggesting its potential role in optimizing feed efficiency in cattle, which is crucial for sustainable beef production.

Additionally, identified on BTA29 through Fst analysis of RACS vs. RAN, exhibited strong selection signals. It has been reported that this gene could be associated with body height in Holstein cows80. A recent study in cetaceans identified this gene as a contributor to tall stature and overgrowth81. The association of AIP with stature indicates its potential role in growth-related traits, which can affect the overall productivity and adaptability of RACS cattle.

Several genes were commonly observed in genetic differentiation analysis between the RACS crossbred and its founder breeds. Notably, a strong selection signal on BTA13 (detected via Fst analysis comparing RACS with RAN, ANG, and SHO) encompassed the ASXL1 gene. ASXL1 regulates gene expression through epigenetic mechanisms, potentially influencing immune cell development and function82,83. The same chromosomal region (BTA13) also harbored the ADA gene, which exhibited differentiation in comparisons between RACS with MON and CRS cattle. ADA is essential for lymphocyte development, particularly T-cell proliferation and differentiation, and contributes to macrophage maturation84. Its critical role in immune function is underscored by studies linking ADA deficiency to lymphopenia and progressive immune dysfunction85. In cattle, ADA activity has been proposed as a biomarker for bovine tuberculosis86, inflammation, and immune activation87, highlighting its diagnostic utility in the RACS crossbred cattle.

SEMA3E, detected in RACS vs. SHO, MON, and CRS comparisons, coordinates immune responses against bacterial infections. SEMA3E, a secreted semaphorin protein, influences cell proliferation, migration, inflammatory responses, and host defense against infections. Research demonstrates that SEMA3E is critical for protective immunity against Chlamydia muridarum lung infection in mice, coordinating the functions of T cells and dendritic cells (DCs)88,89. As MON cattle (adapted to extreme environments) contributed to RACS ancestry, ADA and SEMA3E likely originate from CRS (MON × SHO), enhancing disease resistance and adaptability.

Four genes, SNTG1, KCTD8, ADAMTS2, and NRAP were commonly detected in genetic differentiation analyses of RACS vs. ANG and RAN. Genome-wide association studies suggest that SNTG1 influences body length and longevity in cattle65,90. It has been reported that KCTD8 is associated with carcass traits in composite beef breeds91 and milk production in dairy cattle92. KCTD8 also emerges as a potential selection signature in Maremmana cattle93. This gene encodes subunits for potassium channels linked to prolactin regulation94. ADAMTS2, a procollagen N-proteinase, processes procollagens into collagen95, impacting fat deposition in muscle96, postnatal skeletal muscle development, and meat quality in cattle97. Its role in post-weaning growth is further supported by GWAS in sheep98. Collectively, ADAMTS2, SNTG1, and KCTD8 may enhance meat quality, growth performance, and carcass traits in RACS cattle, fostering economically favorable outcomes for beef production.

The NRAP gene, encoding a highly conserved actin-binding protein critical for muscle function, is strongly associated with cold adaptation in mammals. Primarily expressed in skeletal and cardiac muscles, NRAP facilitates myofibrillar assembly and force transmission, which is particularly vital for cardiac efficiency during cold stress99. A Yakut cattle-specific mutation in NRAP, shared with 16 other cold-adapted species, exemplifies convergent evolution, where distinct lineages independently evolved the same genetic adaptation to enhance heart function in frigid environments100 This mutation likely supports efficient blood circulation during hibernation or extreme cold, underscoring NRAP’s central role in cold resilience. Northern Chinese cattle breeds, including Mongolian (MON) cattle, descendants of taurine ancestry, are exceptionally well-adapted to cold climates100. Given MON’s contribution to the RACS lineage, the NRAP gene likely originated from the CRS parent breed. These findings position NRAP as a key genetic driver of cold adaptation in RACS cattle.

Our study established a genomic baseline for the RACS crossbred population, identifying candidate genes critical for resilience, productivity, and adaptability. These findings provide a foundation to explore their functional roles, enhancing our understanding of the genetic architecture driving these traits. To maximize benefits, we recommend continuing the crossbreeding strategy between Red Angus and Chinese Red Steppe cattle to preserve genetic diversity and heterosis, a proven method to reduce inbreeding and amplify desirable traits like disease resistance, marbling efficiency, and environmental resilience. Simultaneously, regular genomic monitoring of inbreeding levels should be implemented to safeguard diversity and preemptively mitigate inbreeding depression risks.

Integrating genomic selection, particularly through genomic estimated breeding values (GEBVs), will accelerate genetic gains by enabling precise identification and propagation of superior alleles linked to key traits. Collectively, these strategies, strategic crossbreeding, vigilant inbreeding management, and advanced genomic tools, will foster sustainable, high-performing cattle populations capable of thriving in challenging environments while meeting demands for efficient, ethical beef production.

However, while this genomic foundation is vital, we emphasize that phenotypic correlation remains a critical next step. Our study lays the groundwork for future research, in which pairing genomic insights with performance or resilience data will inform targeted breeding strategies. Bridging genomic potential with real-world utility through such integration is essential, and we prioritize this in subsequent investigations to maximize the practical impact of crossbred optimization efforts.

Materials and methods

Data resources and quality control

This study utilized blood samples collected from cattle during routine veterinary procedures on private farms in Xilingol and Ordos, located in Inner Mongolia, China. The sampling process adhered strictly to standard agricultural practices, ensuring no additional interventions were introduced for research purposes.The genotyping analysis conducted on these samples is a common and accepted practice in animal science, often employed for breed improvement and health screening. Importantly, this research did not involve any direct experimentation on live animals, which would typically necessitate a more rigorous ethical review. All sample collection procedures followed established protocols for animal handling and welfare in agricultural settings. The use of these samples for genotyping falls within the regulatory framework for agricultural animal research. While formal ethics committee approval is not required for this type of study, we confirm that all procedures were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations of Inner Mongolia Academy of Agricultural & Animal Husbandry Sciences. Additionally, our experimental protocol was reviewed and approved by the appropriate internal review process at Inner Mongolia Academy of Agricultural & Animal Husbandry Sciences to ensure compliance with institutional standards. We also affirm that our methods comply with the ARRIVE guidelines (https://arriveguidelines.org). This approach ensures minimal invasiveness and no additional harm to the animals while contributing valuable data to the field of animal science. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards set forth by the Inner Mongolia Academy of Agricultural and Animal Husbandry Sciences, which oversees animal research practices in this context. A total of 119 cattle, comprising 104 Red Angus × Chinese Red Steppes (RACS) crosses and 15 Chinese Red Steppes cattle (Mongolian × Shorthorn), were genotyped using the GGP Bovine 100k SNP array and the ARS-UCD1.2 genome reference. The genotypes of eight beef cattle breeds (Angus, Herford, Limousine, Charolais, Mongolian, Shorthorn, Red Angus, and Simmental) and one dairy breed (Holstein) were provided from the WIDDE database101. The information associated with the 669 animals used in the current study is represented in Table S1. All the genotype data were filtered based on the following quality control criteria: (1) individuals and SNPs with a call rate less than 0.95, (2) SNPs with an HWE (Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium) test below the \(\:{10}^{-6}\), (3) SNPs with a minor allele frequency lower than 10%, (4) SNPs unmapped to autosomal chromosomes, were excluded from downstream analyses.

Population genetic structure

To figure out the genetic structure of eleven cattle breeds, principal component analysis (PCA) was carried out and plotted using the SNPRelate and ggplot2 packages in R software102,103, respectively. Moreover, we applied ADMIXTURE v1.3.0 for the estimation of individual ancestries104. An optimum value of K (number of assumed ancestral populations) was inferred with a cross-validation (CV) procedure. We analyzed populations admixture with k = 2 to k = 11 along with 2000 bootstrap replicates. Before investigating population structure, the merged SNPs of 10 breeds were pruned for high pairwise LD by PLINK v1.9 105 with the parameter “indep-pairwise 50 10 0.1”.

Genetic diversity

Inbreeding coefficients were investigated using four measures of inbreeding,\(\:{\text{F}}_{\text{G}\text{R}\text{M}}\:106,\:{\text{F}}_{\text{H}\text{O}\text{M}},\:\:{\text{F}}_{\text{U}\text{N}\text{I}\:}106\), and \(\:{\text{F}}_{\text{R}\text{O}\text{H}}106\) which are based on genotype additive variance, homozygous genotype, the correlation between uniting gametes and run of homozygosis, respectively. The inbreeding coefficient values were derived from the following formula:

In the above three equations, \(\:{\text{x}}_{\text{i}}\) is the number of reference allele copies for the \(\:{\text{i}}^{\text{t}\text{h}}\) SNP, and\(\:{\text{p}}_{\text{i}}\)is the observed fraction of the reference allele at locus \(\:\text{i}\:\)and\(\:{\text{h}}_{\text{i}}=2{\text{p}}_{\text{i}}\left(1-{\text{p}}_{\text{i}}\right)\).

where\(\:{\:\text{L}}_{\text{R}\text{O}\text{H}}\) is the length of ROH regions in an individual’s genome, while \(\:{\text{L}}_{\text{a}\text{u}\text{t}\text{o}}\) denotes the total genome size that is covered by markers.

Pearson’s correlation coefficients between different estimators of inbreeding coefficients were computed using cor and cor.test functions in the R software (http://www.r-project.org/).

Nucleotide diversity, within each breed, was calculated using the --het option in VCFtools v0.1.15 software106. It investigates diversity from the filtered SNP dataset based on observed heterozygosity. Linkage disequilibrium decay (LDD) and the population recombination history was assessed using PopLDdecay v3.42 software107. The mean\(\:{\:r}^{2}\) values were calculated for markers with physical distances less than 200 kb.

The effective population size (Ne) for each breed was calculated using a multithreaded tool, SNeP108. This software estimates the population demography through LD and the formula presented by Corbin, et al.109:

where\(\:{N}_{T\left(t\right)}\) is defined as the effective population size in\(\:t\:\)generation ago, \(\:{c}_{t}\) is the recombination rate between markers with a specific physical distance,\(\:{r}_{adj}^{2}\) is the Linkage disequilibrium (\(\:{r}_{ad}^{2}={r}^{2}-{\left(\beta\:n\right)}^{-1},\:\:n=\:\text{t}\text{h}\text{e}\:\text{n}\text{u}\text{m}\text{b}\text{e}\text{r}\:\text{o}\text{f}\:\text{i}\text{n}\text{d}\text{i}\text{v}\text{i}\text{d}\text{u}\text{a}\text{l}\text{s}\:\text{a}\text{n}\text{d}\:\beta\:=1\:or\:2\)), \(\:\alpha\:\) is a correction for the occurrence of mutations (\(\:\alpha\:=1,\:2\:or\:2.2\)).

To identify and investigate ROH across the beef cattle genome, we employed the “consecutive runs” method in the detectRUNS software110. The minimum number of consecutive SNPs required for a run adjusted to 15. To mitigate the risk of underestimating the length of long ROH regions and to account for potential genotyping errors, we permitted up to two missing genotypes and two opposing genotypes within each run. Additionally, both the maximum allowed gap between consecutive homozygous SNPs (bp) and the minimum length (bp) for recognized ROH were designated at 1 M. Mean ROH length (Mb), percentage of genomic coverage, and the mean ROH number were separately calculated for five ROH length categories 1–2, 2–4, 4–8, 8–16, and > 16 for each breed.

Signatures of selection

Putative signatures of selection between populations were evaluated using Fst statistics in VCFtools software106. The locus-specific Fst values were estimated in the sliding windows of 100 Kb by a step size of 50 Kb. The top 1% of the Fst values was considered as the candidate regions of selection. To trace selection sweeps in the ROH regions, the proportion of times a given SNP presented within a run in each individual was computed and then the detected SNP position was plotted across all autosomal chromosomes. The 45% ROH occurrence threshold in each breed was determined to define the putative ROH islands40. It is important to note that to identify the common selection candidate regions of RACS with their parents and other commercial breeds, ROH analysis was conducted in each breed, along with Fst analysis comparing the RACS crossbred breed to CRS (Cross Red Steppes), RAN (Red Angus), ANG (Angus), SHO (Shorthorn) and MON (Mongolian).

Gene enrichment analysis

Bioinformatic analyses for potential regions under selection were done in two ways: first, the genes placed in candidate regions were detected via the Variant Effect Predictor tool111, second, the gene ontology (GO) terms, molecular functions and biological processes associated with the identified genes were obtained through the Database for Annotation Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID)112. The defined p-values were adjusted to the Fisher exact statistics (P < 0.05).

Conclusions

Our comprehensive genomic analysis of the RACS crossbred reveals valuable insights into the genetic architecture underlying adaptation and productivity. The observed clustering of RACS with Angus and Red Angus in PCA, coupled with its high nucleotide diversity and low inbreeding coefficients, highlights the successful integration of genetic resources from both founder breeds. Our detection of candidate regions associated with immune response, cold adaptation, and carcass traits within the RACS population supports its potential for resilience in challenging environments. Furthermore, the analysis of Runs of Homozygosity (ROH) indicated that the RACS crossbred population harbored the lowest average number and coverage of ROH per animal after CRS, suggesting a broad genetic base. The higher effective population size (Ne) in RACS compared to its parental breeds (RAN and CRS) over the past 15 generations indicates a promising trajectory for maintaining genetic diversity in this crossbred. By providing a detailed characterization of the RACS genome, including population structure, diversity metrics, and signatures of selection, our study contributes a valuable resource for informing future breeding strategies aimed at optimizing beef production in diverse ecological contexts.

Data and code availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available in the Dryad repository, provisional DOI: 10.5061/dryad.t76hdr85m and can be accessed via https://datadryad.org/stash/share/AqZVyGhh02jyLBfveltrds525sAwX4VNRC7lWbHO6hc.

References

Strandén, I. et al. Genomic selection strategies for breeding adaptation and production in dairy cattle under climate change. Heredity 123, 307–317 (2019).

Du, B. et al. Estimation of genetic parameters of Holstein calf survival. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 56, 44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11250-023-03874-z (2024).

Mekonnen, T., Tadesse, Y. & Meseret, S. Genetic improvement strategy of Indigenous cattle breeds: effect of cattle crossbreeding program in production performances. J. Appl. Life Sci. Int. 23, 23–40 (2020).

Mendonça, F. S. et al. Crossbreeding effects on growth and efficiency in beef cow-calf systems: evaluation of Angus, Caracu, Hereford and Nelore breed direct, maternal and heterosis effects. Translational Anim. Sci. 3, 1286–1295. https://doi.org/10.1093/tas/txz096 (2019).

Nisa, F. U. et al. Assessment of genomic diversity and selective pressures in crossbred dairy cattle of Pakistan. Biochem. Genet. 62, 4137–4156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10528-024-10809-2 (2024).

Goszczynski, D. E. et al. Evidence of positive selection towards Zebuine haplotypes in the BoLA region of Brangus cattle. Animal: Int. J. Anim. Bioscience. 12, 215–223. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1751731117001380 (2018).

Li, S. et al. Identification of Heilongjiang crossbred beef cattle pedigrees and reveals functional genes related to economic traits based on whole-genome SNP data. Front. Genet. 15, 1435793 (2024).

Mulim, H. A. et al. Genetic and genomic characterization of a new beef cattle composite breed (Purunã) developed for production in Pasture-Based systems. Front. Genet. 13, 858970. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2022.858970 (2022).

Hu, M. et al. Assessing genomic diversity and signatures of selection in Chinese red steppe cattle using High-Density SNP array. Animals 13, 1717 (2023).

Tian, R. et al. Genomic adaptation to extreme climate conditions in beef cattle as a consequence of cross-breeding program. BMC Genom. 24, 186. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-023-09235-2 (2023).

Wang, L. et al. In China National commission of animal genetic resources. Anim. Genetic Resour. (Chinese Agricultural Press, China Beijing, 2011).

Zhang, W. et al. Genome-wide assessment of genetic diversity and population structure insights into admixture and introgression in Chinese Indigenous cattle. BMC Genet. 19, 114. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12863-018-0705-9 (2018).

Gao, Y. et al. Species composition and environmental adaptation of Indigenous Chinese cattle. Sci. Rep. 7, 1–14 (2017).

Fedotova, G., Slozhenkina, M., Natyrov, A. & Erendzhenova, M. in IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 082076 (IOP Publishing).

Liang, Z. et al. Age-dependent changes of hindgut microbiota succession and metabolic function of Mongolian cattle in the semi-arid rangelands. Front. Microbiol., 13, 2678 (2022).

Li, X., Zhang, J., Zhao, Y. & Hu, C. Study on Polymorphisms of Red Steppe Cattle by Microsatellites. China Herbiv. Sci. Available online: (2004). https://caod.oriprobe.com/articles/20274162/Study_on_Polymorphisms_of_Red_Steppe_Cattle_by_Mic.htm

Liu, L. et al. The effect of Acot2 overexpression or downregulation on the preadipocyte differentiation in Chinese red steppe cattle. Adipocyte 9, 279–289 (2020).

Dlamini, N. M., Dzomba, E. F., Magawana, M., Ngcamu, S. & Muchadeyi, F. C. Linkage Disequilibrium, Haplotype Block Structures, Effective Population Size and Genome-Wide Signatures of Selection of Two Conservation Herds of the South African Nguni Cattle. Animals 12, 2133 (2022).

Duarte, I. N. H. et al. Cross-population selection signatures in canchim composite beef cattle. Plos One. 17, e0264279 (2022).

Signer-Hasler, H., Burren, A., Ammann, P., Drögemüller, C. & Flury, C. Runs of homozygosity and signatures of selection: a comparison among eight local Swiss sheep breeds. Anim. Genet. 50, 512–525 (2019).

Rostamzadeh Mahdabi, E., Esmailizadeh, A. & Ayatollahi Mehrgardi, A. Asadi Fozi, M. A genome-wide scan to identify signatures of selection in two Iranian Indigenous chicken ecotypes. Genet. Sel. Evol. 53, 1–16 (2021).

Szmatoła, T. et al. A comprehensive analysis of runs of homozygosity of eleven cattle breeds representing different production types. Animals 9, 1024 (2019).

Bahbahani, H. et al. Signatures of positive selection in East African shorthorn Zebu: A genome-wide single nucleotide polymorphism analysis. Sci. Rep. 5, 11729 (2015).

Spolaore, E. & Wacziarg, R. The diffusion of development**. Q. J. Econ. 124, 469–529. https://doi.org/10.1162/qjec.2009.124.2.469 (2009).

Gibson, J., Morton, N. E. & Collins, A. Extended tracts of homozygosity in outbred human populations. Hum. Mol. Genet. 15, 789–795 (2006).

Xu, L. et al. Genomic patterns of homozygosity in Chinese local cattle. Sci. Rep. 9, 16977 (2019).

Beishova, I. et al. Distribution of homozygosity regions in the genome of Kazakh cattle breeds. Diversity 14, 279 (2022).

Deniskova, T., Dotsev, A., Selionova, M., Brem, G. & Zinovieva, N. Biodiversity of Russian local sheep breeds based on pattern of runs of homozygosity. Diversity 13, 360 (2021).

Ceballos, F. C., Joshi, P. K., Clark, D. W., Ramsay, M. & Wilson, J. F. Runs of homozygosity: windows into population history and trait architecture. Nat. Rev. Genet. 19, 220–234 (2018).

Alemu, S. W. et al. An evaluation of inbreeding measures using a whole-genome sequenced cattle pedigree. Heredity 126, 410–423 (2021).

Wang, J. Marker-based estimates of relatedness and inbreeding coefficients: an assessment of current methods. J. Evol. Biol. 27, 518–530 (2014).

Deng, T. et al. Genome-wide SNP data revealed the extent of linkage disequilibrium, persistence of phase and effective population size in purebred and crossbred Buffalo populations. Front. Genet. 9, 688 (2019).

Nadachowska-Brzyska, K., Konczal, M. & Babik, W. Navigating the Temporal continuum of effective population size. Methods Ecol. Evol. 13, 22–41 (2022).

Charlesworth, B. Effective population size and patterns of molecular evolution and variation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 10, 195–205 (2009).

Sørensen, A. C., Sørensen, M. K. & Berg, P. Inbreeding in Danish dairy cattle breeds. J. Dairy Sci. 88, 1865–1872 (2005).

Song, X. et al. Whole-genome sequencing reveals genomic diversity and selection signatures in Xia’nan cattle. BMC Genom. 25, 559 (2024).

Purfield, D. C., McParland, S., Wall, E. & Berry, D. P. The distribution of runs of homozygosity and selection signatures in six commercial meat sheep breeds. PLoS One. 12, e0176780. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0176780 (2017).

Peripolli, E. et al. Runs of homozygosity: current knowledge and applications in livestock. Anim. Genet. 48, 255–271 (2017).

Fabbri, M. C. et al. Genetic diversity and population history of eight Italian beef cattle breeds using measures of autozygosity. PloS One. 16, e0248087 (2021).

Peripolli, E. et al. Assessment of runs of homozygosity Islands and estimates of genomic inbreeding in Gyr (Bos indicus) dairy cattle. BMC Genom. 19, 1–13 (2018).

Curik, I., Ferenčaković, M. & Sölkner, J. Inbreeding and runs of homozygosity: a possible solution to an old problem. Livest. Sci. 166, 26–34 (2014).

Howrigan, D. P., Simonson, M. A. & Keller, M. C. Detecting autozygosity through runs of homozygosity: a comparison of three autozygosity detection algorithms. BMC Genom. 12, 1–15 (2011).

Peripolli, E. et al. Genome-wide scan for runs of homozygosity in the composite Montana Tropical® beef cattle. J. Anim. Breed. Genet. 137, 155–165 (2020).

Hay, E. H. et al. Genetic architecture of a composite beef cattle population. J. Anim. Sci. 100 https://doi.org/10.1093/jas/skac230 (2022).

Xia, X. et al. Assessing genomic diversity and signatures of selection in Jiaxian red cattle using whole-genome sequencing data. BMC Genom. 22, 1–11 (2021).

Doekes, H. P. et al. Inbreeding depression due to recent and ancient inbreeding in Dutch Holstein–Friesian dairy cattle. Genet. Selection Evol. 51, 1–16 (2019).

Goszczynski, D. et al. Runs of homozygosity in a selected cattle population with extremely inbred bulls: descriptive and functional analyses revealed highly variable patterns. PLoS One. 13, e0200069 (2018).

Gebregiwergis, G. T. Management of genomic inbreeding in breeding schemes. (2019).

Rebelato, A. B. & Caetano, A. R. Runs of homozygosity for autozygosity Estimation and genomic analysis in production animals. Pesqui Agropecu Bras. 53, 975–984 (2018).

Liu, H., Sørensen, A. C., Meuwissen, T. H. & Berg, P. Allele frequency changes due to hitch-hiking in genomic selection programs. Genet. Sel. Evol. 46, 1–14 (2014).

Zhang, Q., Calus, M. P., Guldbrandtsen, B., Lund, M. S. & Sahana, G. Estimation of inbreeding using pedigree, 50k SNP chip genotypes and full sequence data in three cattle breeds. BMC Genet. 16, 1–11 (2015).

McQuillan, R. et al. Runs of homozygosity in European populations. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 83, 359–372 (2008).

Macharia, J. K. et al. Characterisation of runs of homozygosity and inbreeding coefficients in the red-brown Korean native chickens. Anim. Bioscience. 37, 1355 (2024).

Akinsola, O. M. et al. Genomic insights into adaptation and inbreeding among Sub-Saharan African cattle from pastoral and agropastoral systems. Front. Genet. 15, 1430291 (2024).

Mastrangelo, S. et al. Genomic inbreeding Estimation in small populations: evaluation of runs of homozygosity in three local dairy cattle breeds. Animal 10, 746–754 (2016).

Cortes-Hernández, J., García-Ruiz, A., Vásquez-Peláez, C. G. & Ruiz-Lopez, F. d. J. Correlation of genomic and pedigree inbreeding coefficients in small cattle populations. Animals 11, 3234 (2021).

Liu, S., Ma, X., Hassan, F., Gao, T. & Deng, T. -x. Genome-wide analysis of runs of homozygosity in Italian mediterranean Buffalo. J. Dairy Sci. 105, 4324–4334 (2022).

Weaber, B. Crossbreeding for commercial beef production. National Beef Cattle Evaluation Consortium, 2, 50–57 (2010).

Rodríguez-Ramilo, S., Reverter, A. & Legarra, A. Islands of runs of homozygosity indicate selection signatures in Ovis Aries 6 (OAR6) of French dairy sheep. JDS Commun. 2, 132–136 (2021).

Zhang, Q., Guldbrandtsen, B., Bosse, M., Lund, M. S. & Sahana, G. Runs of homozygosity and distribution of functional variants in the cattle genome. BMC Genom. 16, 1–16 (2015).

Ferenčaković, M. et al. Estimates of autozygosity derived from runs of homozygosity: empirical evidence from selected cattle populations. J. Anim. Breed. Genet. 130, 286–293 (2013).

Mastrangelo, S. et al. Genome-wide scan for runs of homozygosity identifies potential candidate genes associated with local adaptation in Valle Del Belice sheep. Genet. Sel. Evol. 49, 1–10 (2017).

Magalhaes, A. F. et al. Genome-wide association study of meat quality traits in Nellore cattle. PLoS One. 11, e0157845 (2016).

Barreto, A. et al. Genomic analysis of stayability in Nellore cattle. PLoS One. 12, e0179076 (2017).

Mészáros, G., Eaglen, S. & Waldmann, P. A genome wide association study for longevity in cattle. Open. J. Genet. 4, 46–55 (2014).

Ye, H. et al. USP18 mediates interferon resistance of dengue virus infection. Front. Microbiol. 12, 682380 (2021).

Honke, N., Shaabani, N., Zhang, D. E., Hardt, C. & Lang, K. S. Multiple functions of USP18. Cell. Death Dis. 7, e2444–e2444 (2016).

Cheng, Z. et al. Transcriptomic analysis of Circulating leukocytes obtained during the recovery from clinical mastitis caused by Escherichia coli in Holstein dairy cows. Animals 12, 2146 (2022).

Berton, M. P. et al. Genomic regions and pathways associated with Gastrointestinal parasites resistance in Santa Inês breed adapted to tropical climate. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 8, 1–16 (2017).

Williams, M. J., Ando, I. & Hultmark, D. Drosophila melanogaster Rac2 is necessary for a proper cellular immune response. Genes Cells. 10, 813–823 (2005).

Kelly, C. J., Chitko-McKown, C. G. & Chuong, E. B. Ruminant-specific retrotransposons shape regulatory evolution of bovine immunity. Genome Res. 32, 1474–1486 (2022).

Bouzid, D. et al. Polymorphisms in the IL2RA and IL2RB genes in inflammatory bowel disease risk. Genetic Test. Mol. Biomarkers. 17, 833–839 (2013).

Cavanillas, M. L. et al. Polymorphisms in the IL2, IL2RA and IL2RB genes in multiple sclerosis risk. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 18, 794–799 (2010).

Wang, F. Interleukin–18 binding protein: biological properties and roles in human and animal immune regulation. Biomed. Rep. 20, 1–10 (2024).

Lindholm-Perry, A. K. et al. 325 Genes in skeletal muscle associated with gain and intake identified in a multiseason study of crossbred beef steers. J. Anim. Sci. 95, 161–161. https://doi.org/10.2527/asasann.2017.325 (2017).

Sbardella, A. P. et al. Genome-wide association study provides insights into important genes for reproductive traits in Nelore cattle. Animals 11, 1386 (2021).

Jin, Q. et al. CAMK1D inhibits glioma through the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway. Front. Oncol. 12 https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2022.845036 (2022).

Saelao, P. et al. Genetics and genomic regions affecting response to Newcastle disease virus infection under heat stress in layer chickens. Genes (Basel). 10 https://doi.org/10.3390/genes10010061 (2019).

Vivot, K. et al. CaMK1D signalling in AgRP neurons promotes ghrelin-mediated food intake. Nat. Metab. 5, 1045–1058 (2023).

Abdalla, I. M. et al. Identification of candidate genes and functional pathways associated with body size traits in Chinese Holstein cattle based on GWAS analysis. Animals 13, 992 (2023).

Sun, Y. et al. Insights into body size variation in cetaceans from the evolution of body-size-related genes. BMC Evol. Biol. 19, 1–11 (2019).

Gelsi-Boyer, V. et al. Mutations in ASXL1 are associated with poor prognosis across the spectrum of malignant myeloid diseases. J. Hematol. Oncol. 5 https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-8722-5-12 (2012).

Lin, I. et al. Multiomics of Bohring-Opitz syndrome truncating ASXL1 mutations identify canonical and noncanonical Wnt signaling dysregulation. JCI Insight. 8 https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.167744 (2023).

Barua, R. & Hossain, M. Adenosine deaminase in diagnosis of tuberculosis: a review. Anwer Khan Mod. Med. Coll. J. 5, 43–48 (2014).

Sauer, A. V., Brigida, I., Carriglio, N. & Aiuti, A. Autoimmune dysregulation and purine metabolism in adenosine deaminase deficiency. Front. Immunol. 3, 265 (2012).

Dhaliwal, N. K., Narang, D., Chandra, M., Filia, G. & Singh, S. T. Evaluation of adenosine deaminase activity in serum of cattle and buffaloes in the diagnosis of bovine tuberculosis. Vet. World. 13, 110–113. https://doi.org/10.14202/vetworld.2020.110-113 (2020).

Contreras-Aguilar, M. D. et al. Characterization of total adenosine deaminase activity (ADA) and its isoenzymes in saliva and serum in health and inflammatory conditions in four different species: an analytical and clinical validation pilot study. BMC Vet. Res. 16, 384. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-020-02574-2 (2020).

Thomas, R. et al. Exogenous semaphorin 3E treatment protects against chlamydial lung infection in mice. Front. Immunol. 13, 882412. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.882412 (2022).

Thomas, R. et al. Semaphorin 3E protects against chlamydial infection by modulating dendritic cell functions. J. Immun. 206, 1251–1265 (2021).

An, B. et al. Genome-wide association study reveals candidate genes associated with body measurement traits in Chinese Wagyu beef cattle. Anim. Genet. 50, 386–390. https://doi.org/10.1111/age.12805 (2019).

Roberts, A. Genome-wide association study for carcass traits in a composite beef cattle breed. Livest. Sci. 213, 35–43 (2018).

Hayes, B. J. et al. The origin of selection signatures on bovine chromosome 6. Anim. Genet. 39, 105–111 (2008).

Ben-Jemaa, S. et al. Genome-Wide analysis reveals selection signatures involved in meat traits and local adaptation in Semi-Feral maremmana cattle. Front. Genet. 12, 675569. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2021.675569 (2021).

Czarnecki, A., Dufy-Barbe, L., Huet, S. & Odessa, M. F. Bresson-Bepoldin, L. Potassium channel expression level is dependent on the proliferation state in the GH3 pituitary cell line. Am. J. Physiol. Cell. Physiol. 284, C1054–C1064 (2003).

Wang, W. M. et al. Transforming growth factor-β induces secretion of activated ADAMTS-2: a Procollagen III N-proteinase. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 19549–19557 (2003).

Lee, S. H. et al. Use of a bovine genome array to identify new biological pathways for beef marbling in Hanwoo (Korean Cattle). BMC Genom. 11, 1–11 (2010).

Liao, H. et al. The relationships of collagen and ADAMTS2 expression levels with meat quality traits in cattle. Indian J. Anim. Res. 52, 167–172 (2018).

Zhang, L. et al. Genome-wide association studies for growth and meat production traits in sheep. PLoS One. 8, e66569. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0066569 (2013).

Truszkowska, G. T. et al. Homozygous truncating mutation in NRAP gene identified by whole exome sequencing in a patient with dilated cardiomyopathy. Sci. Rep. 7, 3362. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-03189-8 (2017).

Buggiotti, L. et al. Demographic history, adaptation, and NRAP convergent evolution at amino acid residue 100 in the world northernmost cattle from Siberia. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38, 3093–3110 (2021).

Sempéré, G. et al. WIDDE: a Web-Interfaced next generation database for genetic diversity exploration, with a first application in cattle. BMC Genom. 16, 1–8 (2015).

Zheng, X. et al. A high-performance computing toolset for relatedness and principal component analysis of SNP data. Bioinformatics 28, 3326–3328 (2012).

Wickham, H. Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. 2nd Edition, Springer, New York. (2009).

Alexander, D. H., Novembre, J. & Lange, K. Fast model-based Estimation of ancestry in unrelated individuals. Genome Res. 19, 1655–1664 (2009).

Purcell, S. et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 81, 559–575 (2007).

Danecek, P. et al. The variant call format and vcftools. Bioinformatics 27, 2156–2158 (2011).

Zhang, C., Dong, S. S., Xu, J. Y., He, W. M. & Yang, T. L. PopLDdecay: a fast and effective tool for linkage disequilibrium decay analysis based on variant call format files. Bioinformatics 35, 1786–1788 (2019).

Barbato, M., Orozco-terWengel, P., Tapio, M. & Bruford, M. W. SNeP: a tool to estimate trends in recent effective population size trajectories using genome-wide SNP data. Front. Genet. 6, 109 (2015).

Corbin, L. J., Liu, A., Bishop, S. & Woolliams, J. Estimation of historical effective population size using linkage disequilibria with marker data. J. Anim. Breed. Genet. 129, 257–270 (2012).

Biscarini, F., Cozzi, P., Gaspa, G. & Marras, G. Detect runs of homozygosity and runs of heterozygosity in diploid genomes. (2019).

McLaren, W. et al. The ensembl variant effect predictor. Genome Biol. 17, 1–14 (2016).

Huang, D., Sherman, B. & Lempicki, R. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat. Protoc. 4, 44–57 (2009).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the farmers for their participation and cooperation in the sampling of the cattle.

Funding

This project was funded by Scientific and Technological Innovation 2030–Major Project (2023ZD0404803-01), Inner Mongolia major science and technology program (2021ZD0009), Inner Mongolia Agriculture and Animal Husbandry Innovation Fund(2023CXJJM01), National Natural Science Foundation of China (32060731), Foreign young talents program (QN2023005001L), Inner Mongolia key technologies R&D And Achievement Transformation program (2022YFYZ0011).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, A.E., and R.T.; methodology, E.R.M.; software, E.R.M.; validation, J.T., and H.A.N.,; formal analysis, E.R.M.; investigation, A.E.; resources, X.W., M.Z.; data curation, R.T., H.L., B.D., Y.S., W.G., Y.L., and H.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, E.R.M.; writing—review and editing, J.T., H.A.N., X.W., M.Z., H.L., B.D., Y.S., W.G., Y.L., H.Z. and A.E.; supervision, A.E., and R.T.; project ad-ministration, Y.L.; funding acquisition, R.T. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rostamzadeh Mahdabi, E., Tian, R., Tian, J. et al. Uncovering genomic diversity and signatures of selection in red Angus × Chinese red steppe crossbred cattle population. Sci Rep 15, 12977 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98346-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98346-9