Abstract

Consider that inflammatory factors are associated with short-term mortality in patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI). In this retrospective analysis of 2,784 AMI patients from the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care-IV database, we evaluated the impact of inflammatory markers on in-hospital mortality and predicted 30-day and 90-day outcomes. Patients were divided into groups based on in-hospital survival (n = 2,364) and mortality (n = 420). Analysis of initial hospital admission laboratory data, including inflammatory factors, revealed these factors as independent predictors of in-hospital mortality (Q4 of RDW: OR 1.96, NLR: OR 1.63, SII: OR 1.85, and SIRI: OR 2.23, all P < 0.05). Cox proportional hazards models confirmed their significance for predicting 30-day (Q4 of NLR: OR 1.83, SII: OR 1.86, and SIRI: OR 2.01, all P < 0.05) and 90-day mortality (Q4 of RDW: OR 1.46, NLR: OR 1.69, SII: OR 1.73, and SIRI: OR 1.72, all P < 0.05). Increasing levels of inflammatory markers correlated with higher odds and hazard ratios, as illustrated by Restricted Cubic Spline curves. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis showed better survival rates with lower inflammatory marker levels. Receiver operating characteristic curves demonstrated good predictive performance of individual inflammatory factors, with a new composite marker showing the highest predictive ability (AUC = 0.720). This study underscores the association of inflammatory factors with both hospital and short-term mortality in AMI patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Acute myocardial infarction (AMI), including ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), is a critical cardiac emergency associated with high morbidity and mortality1. Patients with AMI have a high hospital mortality rate, reported to be about 7–10%2,3,4, so it is necessary to explore the risk factors associated with mortality.

The pathophysiology of AMI involves myocardial necrosis due to prolonged ischemia, triggering an inflammatory response that exacerbates tissue damage and impairs cardiac function5. Inflammatory cytokines, such as Interleukin-1 beta and Tumor Necrosis Factor alpha, further contribute to myocardial injury and adverse outcomes6,7,8. In addition, the formation and rupture of coronary atherosclerotic plaque is itself is related to the inflammatory response. During myocardial infarction, persistent or excessive inflammatory responses can promote ventricular remodeling, leading to ventricular dilatation and cardiac function impairment9. Therefore, inflammatory reaction is an important pathophysiological link in the occurrence and development of myocardial infarction, and it has an important relationship with the course and prognosis of myocardial infarction.

Inflammatory markers such as the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), and monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio (MLR) have been widely studied for their association with cardiovascular outcomes10. Red blood cell distribution width (RDW) has also been identified as an independent predictor of in-hospital and long-term mortality in STEMI patients, with elevated RDW significantly increasing cardiovascular disease risk11,12. Additionally, the red cell distribution width-to-platelet ratio (RPR) reflects blood rheological status, with elevated RPR indicating increased red blood cell aggregation and viscosity, potentially leading to microcirculation disorders and adverse cardiovascular events13. In patients with coronary heart disease in the intensive care unit (ICU), several markers of inflammation were identified as independent predictors of mortality in the ICU14. A prospective cohort study conducted in Tangshan, Hebei Province, China, demonstrated the correlation between systemic immune inflammation index (SII), systemic inflammatory response index, and the risk of cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality. Furthermore, Xiao et al. observed a U-shaped relationship between SII and all-cause mortality in patients with cardiovascular disease (CVD)15. With advances in emergency and intensive care technology, hospital mortality from AMI has decreased, but is still at higher levels.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the relationship between inflammatory markers such as RDW, NLR, PLR, MLR, RPR, SII and SIRI and all-cause in-hospital mortality in AMI and its predictive analysis of short-term (30-day, 90-day) mortality.

Methods

Data source

The population data utilized in this retrospective study were sourced from the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care-IV (MIMIC-IV) database (version 2.2). This comprehensive database, developed and maintained by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Computational Physiology Laboratory, encompasses extensive medical records of patients admitted to the intensive care units of the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. Access to the database and the requisite certifications (ID 57121385) were secured by one of the authors (Zhenkun Yang). This research project complies with the ethical principles set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the Institutional Review Boards of both the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. Given the standardized nature of the database and the anonymity of participant data, additional ethical approval was deemed unnecessary.

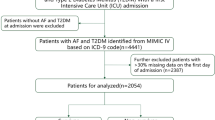

Study population

Patients admitted with a diagnosis of AMI, as defined by the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) 9th and 10th editions, were included in the study (Supplementary Table S1). The exclusion criteria comprised the following: (1) age at first admission < 18 years; (2) hospital stay duration < 24 h; (3) patients with duplicate hospitalization records; and (4) incomplete data for neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, platelets, or RDW. Ultimately, 2,784 patients who met the inclusion criteria were enrolled in the statistical analysis, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

Data extration

Data extraction was performed using Navicat Premium (version 16.1.15) software through the execution of Structured Query Language (SQL). The extracted data encompassed demographic characteristics (age, gender, weight, hight, and race), vital signs (heart rate and blood oxygen saturation), comorbidities (hypertension, type 2 diabetes, atrial fibrillation, congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD], cerebrovascular disease, kidney disease, liver disease, peripheral vascular disease, and malignant tumors), laboratory tests (red blood cell counts [RBC], white blood cell counts [WBC], hemoglobin, platelets, blood creatinine, blood urea nitrogen [BUN], sodium, potassium, calcium, glucose, total bilirubin, plasma prothrombin time [PT], and activated partial prothrombin time [APTT]), and disease severity scores at admission (Acute Physiology Score III [APSIII], Oxford Acute Severity Score [OASIS], Sepsis-Related Organ Failure Assessment Score [SOFA], and Systemic Inflammatory Response System [SIRS]). Intervention and surgical procedures, including percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), were also considered (compliance with ICD-10 is detailed in Supplementary Table S1). Pharmacological treatments, such as aspirin, statins, heparin, β-blockers (BBs), angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers (ACEI/ARBs), calcium channel blockers (CCBs), and nitrates, were also included. For patients with multiple admissions, the initial admission record was selected, and the corresponding measurement indicators were extracted from the first time point post-admission.

The computational formulas for systemic immune-inflammation index (SII) and systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) were defined as follows: SII = neutrophil count × platelet count / lymphocyte count; SIRI = neutrophil count × monocyte count/lymphocyte count. Body mass index was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height squared (m2).

Mortality outcomes

The primary outcomes of our study were hospital mortality, 30-day mortality, and 90-day mortality in patients with acute myocardial infarction.

Statistical analysis

For continuous variables, the mean ± standard deviation or the median and interquartile range (IQR) were reported, depending on the data distribution. Group differences were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance or Kruskal-Wallis tests, as appropriate. Differences in categorical variables among groups were assessed using Fisher’s exact test or Chi-squared test, and results were expressed as counts and percentages.

Baseline characteristics of the study cohort were stratified based on the occurrence of in-hospital mortality. To investigate the independent association between inflammatory markers and the primary endpoint, logistic regression analysis was employed to assess factors influencing in-hospital mortality, while 30-day and 90-day mortality were evaluated using Cox proportional hazards models. The cohort was categorized into four quartiles based on the 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles of inflammatory markers. The first quartile (Q1), representing the lowest values, was designated as the reference group. Adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for in-hospital, 30-day, and 90-day mortality in the other quartiles relative to Q1. Variables demonstrating statistical significance (P < 0.05) in univariate analysis were incorporated as confounders in the multivariable models. Model I: Unadjusted. Model II: Adjusted for age, sex, heart rate, and oxygen saturation. Model III: Model II with additional adjustments for comorbidities, laboratory parameters, clinical severity scores, CABG, and pharmacological treatments. Restricted cubic spline functions with four knots were utilized to examine potential nonlinear relationships between inflammatory markers and the three outcomes. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were constructed to compare the 90-day survival distributions across quartiles of inflammatory markers, and log-rank tests were employed to assess statistical differences. Additionally, the area under the curve (AUC) derived from receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was utilized to evaluate the predictive performance of each inflammatory marker for in-hospital mortality. Simultaneously, the efficacy of combining RDW, NLR, PLR, MLR, RPR, SII, and SIRI to generate a novel predictive marker for in-hospital mortality was assessed.

Furthermore, we conducted a sensitivity analysis to assess the robustness of our findings: (i) Given the significant impact of sepsis and autoimmune diseases on mortality and inflammatory markers, we adjusted for these conditions as confounders to verify the robustness of the primary results; (ii) To avoid potential reverse causality, we excluded patients with a history of malignancy or renal disease and re-evaluated the association between inflammatory markers and mortality outcomes; (iii) Considering the high proportion of patients with comorbid COPD, we excluded these patients from the analysis to further assess the robustness of the results.

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (version 27), StataMP-64, and R (version 4.3.2). A two-tailed P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 2,784 patients with AMI in the MIMIC-IV database were included in this study. The baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. Stratified by hospital mortality, 420 patients experienced hospital mortality, while 2,364 survived the hospitalization. The median age of the cohort was 69 years, and 63% were male. Patients who died in the hospital were older, less likely to be male, and had higher risk scores compared to those who survived. They also had a more burden of comorbidities and more abnormal lab results. Levels of studied parameters including RDW, NLR, MLR, RPR, SII and SIRI were significantly higher in the hospital mortality group compared to the survivor group. However, PLR did not show a statistically significant difference between the two groups (P = 0.085).

Effect of inflammatory markers on in-hospital mortality in AMI

The inflammatory factors were then divided into four groups according to the quartile: RDW: Q1:11.9–13.2; Q2: 13.2–14.2; Q3: 14.2–15.8; Q4: 15.8–23.3; NLR: Q1: 0.51–3.69; Q2: 3.69–6.59; Q3: 6.59-12.00; Q4: 12.00-79.50; PLR: Q1: 0.53–53.39; Q2: 53.39–117.80; Q3: 117.80-213.17; Q4: 213.17-1166.67; MLR: Q1:0.05–0.29; Q2:0.29–0.50;Q3: 0.50–0.92; Q4: 0.92–4.59; RPR: Q1: 0.03–0.06; Q2: 0.06–0.07; Q3: 0.07–0.10; Q4: 0.10–0.55; SII: Q1:41.00-766.53; Q2: 766.53-1295.12; Q3: 1295.12-2568.27; Q4: 2568.27-17736.67; SIRI: Q1: 0.19-0.2.41; Q2: 2.41–6.62; Q3: 6.62–28.69; Q4: 28.69-1837.44.

In a multivariate Logistic regression model adjusted for confounders (Model III), continuous RDW (OR 1.07, P = 0.025), NLR (OR 1.01, P = 0.024), RPR (OR 9.02, P = 0.002), and SII (OR 1.04, P = 0.042) were risk factors for in-hospital mortality. Relative to the Q1, the Q4 of RDW (OR = 1.96, 95% CI: 1.21–3.17, P = 0.006), NLR (OR = 1.63, 95% CI: 1.08–2.47, P = 0.019), SII (OR = 1.85, 95% CI: 1.21–2.85, P = 0.005), and SIRI (OR = 2.23, 95% CI: 1.42–3.50, P < 0.001) were identified as independent risk factors for in-hospital mortality among AMI patients. Furthermore, as RDW and SIRI values increased, the risk of in-hospital mortality also escalated. Trends for PLR were statistically significant (P = 0.028). However, no significant association was found between MLR, RPR, and in-hospital mortality (Table 2).

RCS visualized the relationship between inflammatory markers and in-hospital mortality. In Fig. 2A, the in-hospital mortality of patients with AMI exhibited a non-linear relationship with inflammatory markers (P < 0.001). PLR and SII showed U-shaped associations, with the lowest risk at PLR = 117.92 and SII = 1389.61, followed by a gradual increase that plateaued.

Restricted cubic spline function between inflammation indicators and in-hospital mortality (A). Restricted cubic spline function between inflammation indicators and hospital 30-day mortality (B). Restricted cubic spline function between inflammation indicators and hospital 90-day mortality (C). RDW, red blood cell distribution width; NLR, neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio; PLR, platelet to lymphocyte ratio; MLR, monocyte to lymphocyte ratio; RPR, red blood cell volume distribution width to platelet ratio; SII, systemic immune inflammation index; SIRI, systemic inflammatory response index; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

Effect of inflammatory markers on 30-day mortality in AMI

In multivariate Cox proportional hazards models, adjusted for confounders (Model III), Continuous NLR (HR 1.01, P < 0.001), SII (HR 1.00, P < 0.001), and SIRI (HR 1.00, P = 0.021) were risk factors for 30-day mortality. Relative to the Q1, the Q4 of NLR (OR = 1.83, 95% CI: 1.36–2.46, P < 0.001), SII (OR = 1.86, 95% CI: 1.39–2.50, P < 0.001), and SIRI (OR = 2.01, 95% CI: 1.47–2.76, P < 0.001) were identified as independent risk factors for 30-day mortality among AMI patients. Furthermore, as the values of NLR and SIRI increased, the risk of 30-day mortality also escalated. The trends for PLR were statistically significant (P = 0.039). However, no significant association was observed between RDW, MLR, RPR, and 30-day mortality (Table 3).

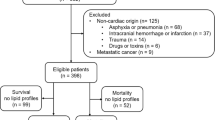

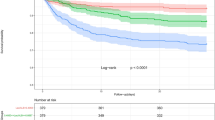

RCS curves showed a nonlinear relationship between 30-day mortality and inflammatory markers in AMI patients (P < 0.001). The risk of death increased with elevated inflammatory markers (Fig. 2B). Kaplan-Meier survival curves were generated based on quartiles of the inflammatory markers (Fig. 3). The curves illustrate a decrease in the 30-day survival probability of patients as the quartiles of inflammatory markers increased (P < 0.001).

Kaplan-Mill survival analysis curves of all-cause mortality in patients with hospital 90-day mortality. RDW, red blood cell distribution width; NLR, neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio; PLR, platelet to lymphocyte ratio; MLR, monocyte to lymphocyte ratio; RPR, red blood cell volume distribution width to platelet ratio; SII, systemic immune inflammation index; SIRI, systemic inflammatory response index.

Effect of inflammatory markers on 90-day mortality in AMI

In a multivariate analysis, continuous RDW (HR 1.04, P = 0.028), NLR (HR 1.01, P < 0.001), MLR (HR 1.08, P = 0.015), RPR (HR 2.15, P = 0.034), SII (HR 1.00, P = 0.002), SIRI (HR 1.00, P = 0.019) were risk factors for 90-day mortality. Relative to the Q1, the Q4 of RDW (OR = 1.46, 95% CI: 1.09–1.96, P = 0.010), NLR (OR = 1.69, 95% CI: 1.32–2.17, P < 0.001), SII (OR = 1.73, 95% CI: 1.34–2.22, P < 0.001), and SIRI (OR = 1.72, 95% CI: 1.32–2.23, P < 0.001) were identified as independent risk factors for 90-day mortality among AMI patients. Furthermore, as NLR and SIRI values increased, the risk of 90-day mortality also escalated. However, no significant association was observed between PLR, MLR, RPR, and 90-day mortality (Table 4).

RCS curves showed a nonlinear relationship between 90-day mortality and inflammatory markers in AMI patients (P < 0.001). The risk of death increased with elevated inflammatory markers (Fig. 2C). Kaplan-Meier survival curves (Fig. 3) illustrated a decrease in the 90-day survival probability of patients as the quartiles of inflammatory markers increased (P < 0.001). Among them, the differences in predicting patient mortality rates after about 90 days gradually diminished between Q3 and Q4 of the inflammatory marker SIRI.

Efficacy of inflammatory markers to predict in-hospital death

ROC analysis demonstrated that the AUC for predicting in-hospital mortality AMI was significantly higher for the novel combined marker than for other inflammatory markers (New marker: Z = 16.712, P < 0.001; RDW: Z = 11.117, P < 0.001; NLR: Z = 10.555, P < 0.001; PLR: Z = 1.563, P = 0.118; MLR: Z = 9.811, P < 0.001; RPR: Z = 4.726, P < 0.001; SII: Z = 7.461, P < 0.001; SIRI: Z = 10.243, P < 0.001). The AUC for the novel marker was 0.720, with a sensitivity of 72.62% and a specificity of 60.19% (Fig. 4). Except for PLR, all other markers exhibited significant predictive value for in-hospital mortality in AMI (P < 0.001).

The receiver operator characteristic curves for inflammation indicators as well as a combined new marker for predicting in-hospital mortality respectively. AUC, area under the curve; RDW, red blood cell distribution width; NLR, neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio; PLR, platelet to lymphocyte ratio; MLR, monocyte to lymphocyte ratio; RPR, red blood cell volume distribution width to platelet ratio; SII, systemic immune inflammation index; SIRI, systemic inflammatory response index.

Correlation analysis between inflammatory markers and CRP

After removing patients with missing CRP markers, we did Spearman’s correlation analysis of inflammatory markers and CRP in 242 AMI patients, which showed that CRP was positively correlated with NLR (r = 0.18, P = 0.004), PLR (r = 0.19, P = 0.003), MLR (r = 0.19, P = 0.003), and SII (r = 0.18, P = 0.004) were positively correlated.

Sensitivity analysis

To evaluate the potential impact of sepsis and autoimmune diseases on the study results, we included patients with a history of these comorbidities (sepsis, n = 457; autoimmune disease, n = 20) and re-analyzed the data (Supplementary Table S2). Compared to Q1, Q4 of RDW was an independent risk factor for 90-day mortality among AMI patients (HR 1.42, P = 0.048). Compared to Q1, Q4 of NLR were independent risk factors for in-hospital mortality (OR 1.90, P = 0.022), 30-day mortality (HR 2.03, P < 0.001), and 90-day mortality (HR 1.81, P < 0.001). Compared to Q1, Q4 of SII were independent risk factors for in-hospital mortality (OR 2.04, P = 0.012), 30-day mortality (HR 2.02, P < 0.001), and 90-day mortality (HR 1.76, P < 0.001). Compared to Q1, Q4 of SIRI were independent risk factors for in-hospital mortality (OR 1.97, P = 0.021), 30-day mortality (HR 2.17, P < 0.001), and 90-day mortality (HR 1.59, P = 0.005).

To evaluate the potential impact of malignant cancer and renal disease on the study results, we excluded patients with a history of these conditions (n = 1068) and re-analyzed the data (Supplementary Table S3). Compared to Q1, Q4 of NLR were independent risk factors for in-hospital mortality, 30-day and 90-day mortality (OR 1.85, P = 0.023; HR 1.76, P = 0.016; HR 1.92, P = 0.001). Compared to Q1, Q4 of SII were independent risk factors for in-hospital mortality, 30-day and 90-day mortality (OR 1.88, P = 0.040; HR 1.54, P = 0.040; HR 1.69, P = 0.008). Compared to Q1, Q4 of SIRI were independent risk factors for hospital mortality, 30-day and 90-day mortality (OR 2.28, P = 0.019; HR 1.64, P = 0.032; HR 1.51, P = 0.036).

To evaluate the potential impact of COPD on the study results, we excluded patients with a history of COPD (n = 665) and re-analyzed the data (Supplementary Table S4). Compared to Q1, Q4 of RDW (OR 2.37, P = 0.003) and SIRI (OR 1.74, P = 0.036) were independent risk factors for in-hospital mortality; compared to Q1, Q4 of RDW (HR 1.51, P = 0.041), SII (HR 1.80, P = 0.001) and SIRI (HR 1.65, P = 0.008) were independent risk factors for 30-day mortality; compared to Q1, Q4 of SII (HR 1.76, P < 0.001) and SIRI (HR 1.59, P = 0.005) were independent risk factors for 90-day mortality.

Discussion

Study assessed associations between hematological inflammatory indices (RDW, NLR, PLR, MLR, RPR, SII, SIRI) and mortality in acute myocardial infarction (AMI) patients. Consistent with prior evidence, elevated RDW, NLR, SII, and SIRI were independently associated with increased all-cause mortality in AMI2,16. Immune cells, including lymphocytes, neutrophils, and monocytes, play critical roles in coronary atherosclerosis progression. Although inflammatory responses are increasingly linked to coronary heart disease, the prognostic significance of specific inflammatory markers in AMI remains underexplored. Persistent proinflammatory states may exacerbate post-MI left ventricular remodeling, highlighting inflammation as a potential therapeutic target for improving AMI outcomes.

Previously, studies have utilized inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein, white blood cell counts, Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha, interleukins, and hs-CRP to assess inflammation in myocardial infarction, which is closely associated with cardiovascular event risk, disease severity, and prognosis17. Routine blood tests, which are cost-effective and widely accessible, have gained increasing attention for evaluating inflammatory markers in peripheral blood and their relationship with cardiovascular mortality18. While traditionally used in diagnosing anemia, RDW has been linked to various conditions, including heart failure, atrial fibrillation, stroke, and dyslipidemia. The Malmö Diet and Cancer Study found that individuals in the highest RDW quartile had an elevated risk of fatal acute coronary events over a 14-year follow-up19. Similarly, a study of 312 STEMI patients undergoing thrombolysis demonstrated that baseline RDW independently predicted ST-segment regression and MACE20. This association may stem from reduced erythrocyte deformability and impaired microvascular perfusion, exacerbating microcirculatory dysfunction in AMI21.

Elevated neutrophil levels are associated with increased risks of ischemic events and AMI mortality22. Núñez et al. study demonstrated that post-hospitalization NLR independently predicts 1-year reinfarction and mortality in AMI patients with diabetes23. Consistent with these findings, our study identified NLR as an independent risk factor for in-hospital, 30-day and 90-day mortality in AMI, with higher values correlating with increased mortality risk, likely due to neutrophils exacerbating inflammatory responses during myocardial repair and left ventricular remodeling24. Meta-analyses suggest that elevated PLR levels are associated with increased risks of MACE, including cardiovascular mortality, MI, and ischemic stroke, in ACS populations25. Previous studies have shown heterogeneity in PLR’s predictive value and cutoff thresholds26, and while its relationship with ACS severity and prognosis exists, its independent predictive role requires further validation.

A positive association between elevated MLR and increased mortality risk in the general population, with MLR serving as a strong independent predictor of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality27. The RPR is associated with inflammatory responses and disease severity, particularly in systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and sepsis13. Wu et al. reported that elevated RPR was significantly associated with sepsis and increased mortality in acute kidney injury patients28. However, our study RPR have not shown that this index would be predictive of hospital mortality in AMI, this discrepancy may be attributed to differences in the baseline characteristics, comorbidities, or disease severity of our study population compared to previous studies. Additionally, RPR is a dynamic marker that can fluctuate rapidly in response to acute physiological changes. In our study, RPR was measured only at the time of admission, which may have influenced its association with outcomes. SII and SIRI are novel inflammatory markers that reflect both local and systemic immune responses29,30. SII is positively correlated with myocardial injury markers and accurately predicts short- and long-term major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) in ACS patients31. 20-year cohort study of 42,875 US adults demonstrated that an SII level > 655.56 was associated with higher cardiovascular mortality (HR = 1.33; 95% CI: 1.11–1.59) compared to an SII level < 335.3632. Similarly, SIRI, a marker of systemic inflammation, indicated that adults with SIRI > 1.43 had a higher risk of cardiovascular mortality (HR = 1.39; 95% CI: 1.14–1.68) than those with SIRI < 0.6832. Both SII and SIRI have significant clinical implications for AMI prognosis, although the underlying mechanisms require further investigation. Our study, excluding sepsis and immune diseases, confirms that these inflammatory factors remain independent risk factors for in-hospital and short-term AMI mortality.

Inflammation plays a key role in arrhythmic events and higher short-term mortality in AMI patients33. Cytokines like IL-6, TNF-α, and CRP disrupt cardiac function, increase oxidative stress, and promote fibrosis, heightening arrhythmia risk. Inflammation also worsens ischemia-reperfusion injury, further destabilizing the myocardium34. This link may explain the higher mortality in AMI patients, as arrhythmias are a major cause of death35. Targeting inflammatory pathways could reduce arrhythmic events and improve outcomes in AMI36. Future research should focus on targeting inflammatory pathways to reduce arrhythmic events and improve AMI outcomes. Furthermore, lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)] has been increasingly recognized as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease, including AMI. Elevated Lp(a) levels are associated with atherosclerosis progression and adverse cardiovascular outcomes, as highlighted by DiFusco et al. Lp(a) promotes inflammation, thrombosis, and plaque instability, contributing to the pathogenesis of AMI37.

Our study helps clinicians identify high-risk populations for in-hospital mortality, enabling timely interventions to improve prognosis. However, it has several limitations. First, as a retrospective analysis, it relied on pre-existing data, which may introduce biases such as incomplete records, missing information, or inconsistencies in data collection. The lack of control over variables and the inability to establish causality are inherent challenges in retrospective designs. Second, although we adjusted for multiple confounding factors, unmeasured variables and traditional inflammatory markers not evaluated due to data limitations may still influence in-hospital mortality. Third, we only included patients diagnosed with AMI during hospitalization, excluding initial admission diagnoses. We did not analyze STEMI and NSTEMI subgroups separately or assess the impact of left ventricular function, Killip class, or cardiogenic shock, which are limitations of the MIMIC-IV database. Future large-scale prospective trials should incorporate these clinical characteristics for further analysis. Finally, although our novel biomarker has demonstrated good predictive ability for in-hospital mortality, direct comparisons with validated clinical scores such as GRACE and TIMI were not performed due to limitations of our database. Future prospective studies should be conducted to evaluate its additive and comparative performance against these established risk stratification tools.

Conclusion

RDW, NLR, SII, and SIRI were independent risk factors for in-hospital, 30-day, and 90-day mortality in AMI patients. Elevated levels of these indicators highlight the role of inflammation in AMI prognosis. Monitoring them could improve risk assessment and patient management.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AMI:

-

Acute myocardial infarction

- AUC:

-

Area under the curve

- STEMI:

-

ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction

- USTEMI:

-

Non ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction

- NLR:

-

Neutrophil count to lymphocyte count ratio

- PLR:

-

Platelet count to lymphocyte count ratio

- MLR:

-

Monocyte count to lymphocyte count ratio

- RDW:

-

Red blood cell distribution width

- RPR:

-

Red blood cell volume distribution width to platelet count

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- SII:

-

Systemic immune inflammation index

- SIRI:

-

Systemic inflammatory response index

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular disease

- MIMIC-IV:

-

Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care-IV

- ICD:

-

International Classification of Diseases

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- COPD:

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- RBC:

-

Red blood cell counts

- WBC:

-

White blood cell counts

- BUN:

-

Blood urea nitrogen

- PT:

-

Plasma prothrombin time

- APTT:

-

Activated partial prothrombin time

- APSIII:

-

Acute Physiology Score III

- OASIS:

-

Oxford Acute Severity Score

- SOFA:

-

Sepsis-Related Organ Failure Assessment Score

- SIRS:

-

Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome

- PCI:

-

Percutaneous coronary intervention

- CABG:

-

Coronary artery bypass grafting

- BBs:

-

β-Blockers

- ACEI/ARBs:

-

Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers

- CCB:

-

Calcium channel blockers

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

- Hs-CRP:

-

High-sensitivity C-reactive protein

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- MCV:

-

Mean red blood cell counts cell volume

- MACE:

-

Major adverse cardiac events

References

Anderson, J. L. & Morrow, D. A. Acute myocardial infarction. N. Engl. J. Med. 376(21), 2053–2064 (2017).

Anderson, J. L., Campion, E. W. & Morrow, D. A. Acute myocardial infarction. N. Engl. J. Med. 376(21), 2053–2064 (2017).

Sandoval, Y. & Jaffe, A. S. Type 2 myocardial infarction: JACC review topic of the week. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 73(14), 1846–1860 (2019).

Thygesen, K. et al. Fourth universal definition of myocardial infarction (2018). Circulation 138(20), e618–e651 (2018).

Liu, J., Wang, H. & Li, J. Inflammation and inflammatory cells in myocardial infarction and reperfusion injury: A Double-Edged sword. Clin. Med. Insights Cardiol. 10, 79–84 (2016).

Schmitz, T. et al. Inflammatory plasma proteins predict short-term mortality in patients with an acute myocardial infarction. J. Transl. Med. 20(1), 457 (2022).

Zhao, Y. et al. Disruption of circadian rhythms by shift work exacerbates reperfusion injury in myocardial infarction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 79(21), 2097–2115 (2022).

Frangogiannis, N. G. The immune system and cardiac repair. Pharmacol. Res. 58(2), 88–111 (2008).

Li, H. et al. Inflammatory biomarkers of coronary heart disease. Front. Biosci. 10(1), 185–196 (2018).

Dentali, F. et al. Impact of neutrophils to lymphocytes ratio on major clinical outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndromes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. Int. J. Cardiol. 266, 31–37 (2018).

Salvagno, G. L., Sanchis-Gomar, F., Picanza, A. & Lippi, G. Red blood cell distribution width: A simple parameter with multiple clinical applications. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 52(2), 86–105 (2015).

Tonelli, M. et al. Relation between red blood cell distribution width and cardiovascular event rate in people with coronary disease. Circulation 117(2), 163–168 (2008).

Tong, L. et al. Relationship between the red cell distribution width-to-platelet ratio and in-hospital mortality among critically ill patients with acute myocardial infarction: A retrospective analysis of the MIMIC-IV database. BMJ Open 12 (9), e062384 (2022).

Cheng, Y. et al. Association of inflammatory indicators with intensive care unit mortality in critically ill patients with coronary heart disease. Front. Immunol. 14, 1295377 (2023).

Xiao, S. et al. Association of systemic immune inflammation index with all-cause, cardiovascular disease, and cancer-related mortality in patients with cardiovascular disease: A cross-sectional study. J. Inflamm. Res. 16, 941–961 (2023).

Collet, J. P. et al. 2020 ESC guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation. Eur. Heart J. 42(14), 1289–1367 (2021).

Abbate, A. et al. Interleukin-1 and the inflammasome as therapeutic targets in cardiovascular disease. Circ. Res. 126(9), 1260–1280 (2020).

Zhang, C. et al. The predictive value of potential hematological biomarkers in acute coronary syndrome. Clin. Lab. 65(10) (2019).

Borné, Y., Smith, J. G., Melander, O. & Engström, G. Red cell distribution width in relation to incidence of coronary events and case fatality rates: A population-based cohort study. Heart 100(14), 1119–1124 (2014).

Ghaffari, S. et al. Red cell distribution width is a predictor of ST resolution and clinical outcome following thrombolysis in acute ST elevation myocardial infarction. Thromb. Res. 140, 1–6 (2016).

Arbel, Y. et al. Red blood cell distribution width and 3-year outcome in patients undergoing cardiac catheterization. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis. 37(4), 469–474 (2014).

Caimi, G., Lo Presti, R., Canino, B., Ferrera, E. & Hopps, E. Behaviour of the neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio in young subjects with acute myocardial infarction. Clin. Hemorheol. Microcirc. 62(3), 239–247 (2016).

Núñez, J. et al. Usefulness of the neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio in predicting long-term mortality in ST segment elevation myocardial infarction. Am. J. Cardiol. 101(6), 747–752 (2008).

Antipenko, S. et al. Neutrophils are indispensable for adverse cardiac remodeling in heart failure. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 189, 1–11 (2024).

Li, X. T. et al. Association of platelet to lymphocyte ratio with in-hospital major adverse cardiovascular events and the severity of coronary artery disease assessed by the Gensini score in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Chin. Med. J. 133(4), 415–423 (2020).

Li, H., Zhou, Y., Ma, Y., Han, S. & Zhou, L. The prognostic value of the platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio in acute coronary syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Kardiol. Pol. 75(7), 666–673 (2017).

Hua, Y., Sun, J. Y., Lou, Y. X., Sun, W. & Kong, X. Q. Monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio predicts mortality and cardiovascular mortality in the general population. Int. J. Cardiol. 379, 118–126 (2023).

Wu, J. et al. Red Cell Distribution Width to Platelet Ratio Is Associated with Increasing In-Hospital Mortality in Critically Ill Patients with Acute Kidney Injury. Dis. Mark. 2022, 4802702 (2022).

Ma, R. et al. Association between systemic immune inflammation index, systemic inflammation response index and adult psoriasis: Evidence from NHANES. Front. Immunol. 15, 1323174 (2024).

Wang, R. H. et al. The clinical value of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), systemic immune-inflammation index (SII), platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) and systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) for predicting the occurrence and severity of pneumonia in patients with intracerebral hemorrhage. Front. Immunol. 14, 1115031 (2023).

Karadeniz, F., Karadeniz, Y. & Altuntaş, E. Systemic immune-inflammation index, and neutrophilto-lymphocyte and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratios can predict clinical outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Cardiovasc. J. Afr. 34, 1–7 (2023).

Xia, Y. et al. Systemic immune inflammation index (SII), system inflammation response index (SIRI) and risk of All-Cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality: A 20-Year Follow-Up cohort study of 42,875 US adults. J. Clin. Med. 12(3) (2023).

Yang, X. et al. Systemic inflammation indicators and risk of incident arrhythmias in 478,524 individuals: Evidence from the UK biobank cohort. BMC Med. 21 (1), 76 (2023).

Grune, J., Yamazoe, M. & Nahrendorf, M. Electroimmunology and cardiac arrhythmia. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 18(8), 547–564 (2021).

Kalarus, Z. et al. Cardiac arrhythmias in the emergency settings of acute coronary syndrome and revascularization: An European heart rhythm association (EHRA) consensus document, endorsed by the European association of percutaneous cardiovascular interventions (EAPCI), and European acute cardiovascular care association (ACCA). Europace: European Pacing, Arrhythmias, and Cardiac Electrophysiology: Journal of the Working Groups on Cardiac Pacing, Arrhythmias, and Cardiac Cellular Electrophysiology of the European Society of Cardiology 21(10), 1603–1604. (2019).

Manning, J. R. et al. Rad GTPase deletion attenuates post-ischemic cardiac dysfunction and remodeling. JACC Basic Transl. Sci. 3(1), 83–96 (2018).

Di Fusco, S. A. et al. Inflammation, and atherosclerosis. J. Clin. Med. 12(7) (2023).

Funding

This research did not receive any specific funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.K.Y.: Data curation, Software, Visualization, Writing - original draft; Y.J.L.: Data curation, Software, Visualization; T.P.G.: Data curation, Software, Visualization; M.J.Y.: Visualization, Investigation; Y.C.: Data curation; Y.X.G.: Supervision, Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The use of this database was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. The project adhered to the Helsinki Declaration, and given the retrospective nature of the study and the anonymity of participants and the standardization of data in the database, the Institutional Review Board of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology has waived informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, Z., Li, Y., Guo, T. et al. The effect of inflammatory markers on mortality in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Sci Rep 15, 14514 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98408-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98408-y

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Preoperative LDL-C and mortality after cardiac valve surgery: a retrospective cohort study on the mediating role of inflammatory risk

Lipids in Health and Disease (2026)

-

Dual-pathway model of IL-6 and HSP22/HSP27 dynamics predicts post-PCI MACE in STEMI patients

BMC Cardiovascular Disorders (2025)

-

Early blood pressure response index and mortality risk in cardiogenic shock: evidence from two critical care cohorts

BMC Cardiovascular Disorders (2025)

-

Stress hyperglycemia ratio and mortality in critically ill patients with heart failure: a retrospective cohort study from the MIMIC-IV database

BMC Cardiovascular Disorders (2025)

-

Emerging trends in cardiovascular diseases: the impact of ferroptosis and cuproptosis on cardiomyocyte death

Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry (2025)