Abstract

Our study aims to evaluate the prevalence of elevated cardiac biomarkers, as well as their associations with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and long-term risk of mortality (all-cause and cardiovascular) in the US individuals without known cardiovascular disease. The study population was derived from individuals aged ≥ 20 years in NHANES 1999 to 2004. We calculated the prevalence of elevated cardiac biomarkers in both CKD and non-CKD populations and used multivariable logistic regression to assess the relationships between each cardiac biomarker and CKD. We also used multivariable Cox proportional hazards models and competing risk models to evaluate the adjusted associations between elevated cardiac biomarkers and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. The crude prevalence of CKD in the overall population was 14.71%. Among CKD individuals, the age-standardized prevalence of elevated NT-ProBNP (≥ 125 pg/mL), hs-cTnT (≥ 6 ng/L), and hs-cTnI (M ≥ 6 ng/L and F ≥ 4 ng/L) were 26.43%, 47.44%, and 19.23%, respectively. After adjusting for cardiovascular and renal risk factors, significant correlations were observed between elevated cardiac biomarkers with CKD. Analysis of follow-up data revealed elevated cardiac biomarkers were independently associated with cumulative occurrence of all-cause mortality (CKD: adjusted hazard ratio [HR]: NT-proBNP: 2.00 [95% CI, 1.56–2.56]; hs-cTnT: 2.89 [95% CI, 1.96–4.26]; hs-cTnI: 1.92 [95% CI, 1.50–2.44]) and cardiovascular mortality (CKD: adjusted hazard ratio [HR]: NT-proBNP: 2.38 [95% CI, 1.61–3.51]; hs-cTnT: 2.70 [95% CI, 1.35–5.40]; hs-cTnI: 2.11 [95% CI, 1.46–3.04]). Additionally, different detection methodologies (Abbott, Siemens, Ortho) do not significantly affect the correlation between hs-cTnI and CKD, with a consistent positive correlation observed. Our research evaluated the substantial burden of elevated cardiac biomarkers in CKD individuals and provided crucial prognostic information regarding the long-term risk of mortality. These findings will offer significant guidance for risk stratification and the formulation of tailored prevention strategies across diverse populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) has gradually increased in health burden in recent years1,2, particularly among the elderly3, affecting approximately 10% of the adult population worldwide4,5. Compared to the general population, individuals diagnosed with CKD experience a considerably reduced life expectancy and an elevated rate of mortality. Notably, approximately half of all deaths are attributed to cardiovascular complications6,7. In view of the independent risk contribution of CVD, it is imperative that cardiovascular risk factors be precisely identified in CKD individuals and that their control be strengthened.

As widely recognized cardiac biomarkers, a growing body of evidence recommends the use of N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T (hs-cTnT), and high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I (hs-cTnI) for the identification of cardiovascular risk factors in patients with CKD8,9,10,11. Existing clinical research has indicated an increased risk of myocardial infarction and heart failure among individuals with CKD12. Moreover, CKD individuals have also displayed elevated concentrations of NT-proBNP and hs-cTnT/I, particularly in cases of unconventional acute myocardial injury and heart failure13. Therefore, the interpretation of elevated cardiac biomarkers in CKD individuals has become intricate and challenging. Generally, elevated cardiac biomarkers are commonly considered to have limited clinical significance in CKD individuals, primarily due to impaired renal clearance14,15. However, the elevated cardiac biomarkers primarily reflect cardiovascular risk, rather than solely being a result of decreased renal clearance16,17.

Our study aims to assess the prevalence of elevated cardiac biomarkers (NT-proBNP, hs-cTnT, hs-cTnI) in individuals without known cardiovascular disease, as well as their associations with CKD. Additionally, we investigate the associations between elevated cardiac biomarkers and the risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality across different groups.

Methods

Study design and participants

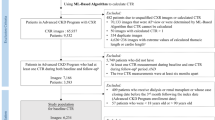

The data for this study were sourced from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), a nationally representative cross-sectional survey conducted on the non-institutionalized civilian population of the U.S. All individuals obtained written informed consent after receiving approval from both the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). The sample consists of adult individuals (age ≥ 20 years) who took part in the NHANES from 1999 to 2004. Individuals with known cardiovascular diseases, defined as self-reported coronary artery disease, heart attack, angina, stroke, or heart failure (n = 17,772), were excluded. Additionally, those with incomplete data regarding blood, urine creatinine or albuminuria (n = 1,823), cardiac biomarkers, and other covariates (n = 1,522) were also excluded. A total of 10,009 individuals were included in the final analysis. The study design and exclusion details are shown in the flowchart (Fig. 1).

Elevated cardiac biomarkers

During the period from 2018 to 2020, researchers conducted cardiac biomarker measurements in stored serum samples at the University of Maryland School of Medicine. The Roche Cobas e601 automated analyzer was used to measure the levels of NT-proBNP in serum. The lower limit of detection was 5 pg/mL, and the upper limit was 35,000 pg/mL, with coefficients of variation (CV) of 3.1% (low, 46 pg/mL) and 2.7% (high, 32,805 pg/mL). The measurement of hs-cTnT in serum was performed using the Roche Cobas e601 analyzer with Elecsys reagents. The detection limit was 3 ng/L, and CV: 3.1% [26.12–31.28 ng/L] and 2.0% [2004.5–2215 ng/L]. The measurement of hs-cTnI in serum was conducted using the Abbott ARCHITECT i2000SR analyzer, with a LoD of 1.7 ng/L and CV: 6.4% (8.12–16.01 ng/L), CV: 4.5% (27.69–55.38 ng/L), CV: 3.5% (169.1–314.1 ng/L), and CV: 6.7% (2758–4444 ng/L).

In the main analysis, we referred to other research findings and stratified the levels of NT-proBNP, hs-cTnT, and hs-cTnI (Abbott) according to established clinical reference ranges for cardiovascular biomarkers18,19,20. The cutoff ranges were as follows: NT-proBNP: < 125 pg/mL, 125- < 300 pg/mL, 300- < 450 pg/mL, and ≥ 450 pg/mL; hs-cTnT: < 6 ng/L, 6- < 14 ng/L, and ≥ 14 ng/L; hs-cTnI (Abbott): males < 6 ng/L, females < 4 ng/L; males 6–12 ng/L, females 4–10 ng/L; and males > 12 ng/L, females > 10 ng/L. Elevated cardiac biomarkers are defined as increased levels of NT-proBNP (≥ 125 pg/mL), hs-cTnT (≥ 6 ng/L), or hs-cTnI (males ≥ 6 ng/L, females ≥ 4 ng/L).

Chronic kidney disease

The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of the individuals was calculated using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation (CKD-EPI)21,22. The urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR) was calculated by dividing the urinary microalbumin level (mg/L) by the urinary creatinine level (g/L)23. In accordance with prevailing criteria, CKD is defined as an eGFR of < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 or a UACR of ≥ 30 mg/g24,25.

Mortality

Follow-up was conducted from the beginning of the investigation (1999–2004) until December 31, 2019. Mortality data for individuals were obtained by linking their personal identification codes with death certificate records from the National Death Index (NDI). Death certificates record the precise cause of death based on International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10) codes. In this study, cardiovascular mortality was defined as any death caused by heart or cerebrovascular diseases with ICD codes I00-I99.

Other baseline information

The trained interviewers collected sociodemographic information such as age, gender, race, and education level of individuals during family interview questionnaires. Blood pressure was measured three consecutive times on the right arm, with a 30 s interval between every measurement. Hypertension was defined as an average systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mmHg or an average diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mmHg, or self-reported history of hypertension diagnosed by a physician. Smoking status was assessed using a detailed questionnaire and categorized as never, current, or former smoking. Individuals were required to fast for at least 8.5 h before providing a fasting venous blood sample for the purpose of analyzing levels of total cholesterol, triglycerides, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, uric acid, creatinine, urea, glycated hemoglobin, and fasting glucose. Albuminuria was detected using a solid-phase fluorescent immunoassay. Diabetes was defined as self-reported history of diabetes diagnosed by a physician or HbA1c ≥ 6.5%. Random urine samples were collected and subsequently subjected to analysis to determine the levels of urinary creatinine and the urinary albumin. Medication use was obtained from prescription records of medications used in the past month, including angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARB) and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI).

Statistical analysis

In the study, we examined the characteristics of sociodemographic, cardiovascular and renal risk factors among individuals based on CKD status. In individuals with or without CKD, we firstly evaluated the crude prevalence of elevated levels of cardiac biomarkers. Following the recommendations for data analysis, we subsequently age-standardized the prevalence using the age distribution of the US adult population in 2000 as the reference26.

In the main analysis, we employed multivariable logistic regression models to evaluate the relationships between CKD and elevated cardiac biomarkers. Trend tests were conducted, and these biomarkers were modeled using clinical cutoff points. Model 1 was non-adjusted; Model 2 was adjusted for age, gender, race, and education level; and Model 3 was further adjusted for smoking, BMI, hypertension, TC, TG, HDL-C, Ua, FBG, HbA1c, hs-CRP, albuminuria, eGFR, diabetes, and medication use. Additionally, in the supplementary analysis, we also conducted adjustments for other cardiac biomarkers.

In order to visually characterize the continuous association between cardiac biomarkers and CKD, we utilized restricted cubic splines to model each biomarker, with 4 knots located at the 5th, 35th, 65th, and 95th percentiles. In the subgroups analysis, we examined the relationships between cardiac biomarkers and CKD in different subgroups based on age, gender, BMI, hypertension, diabetes, and medication use, while interaction tests were also performed to assess the consistency with the overall population results. In addition, to minimize the interference of low renal filtration function on the correlation between elevated cardiac biomarkers and CKD, we further conducted a sensitivity analysis. In this analysis, individuals with an eGFR of < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 were excluded, and CKD was defined as a UACR of ≥ 30 mg/g. (participants: n = 9,385).

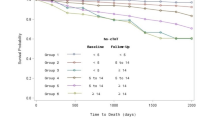

In individuals with or without CKD, we employed multivariable Cox proportional hazards models and Kaplan–Meier curves to evaluate the associations between elevated cardiac biomarkers and all-cause mortality. We also used competing risk models and the Cumulative Incidence Function (CIF) to assess the associations between elevated cardiac biomarkers and cardiovascular mortality. Moreover, we also compared the relationship between hs-cTnI detected by different methods (Abbott Laboratories, Siemens Diagnostics, and Ortho Clinical Diagnostics) and CKD, as well as all-cause and cardiovascular mortality.

All analyses incorporated the recommended sampling survey weights to obtain unbiased estimates of the results. All analyses were performed using the statistical package R (http://www.r-project.org; version 4.2.3), with a P-value of < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

Between 1999 and 2004, about 14.71% of individuals in the US without known cardiovascular disease had CKD. Examining the sociodemographic characteristics shows that those with CKD were typically older and had lower education levels. Regarding cardiovascular and renal risk factors, individuals with CKD were more likely to have comorbidities such as hypertension and diabetes, as well as higher smoking rates, BMI, TC, TG, HbA1c, FBG, urea, Ua, hs-CRP, albuminuria, cardiac biomarkers, and medication use (Table 1).

In individuals with CKD, the crude prevalence of elevated NT-ProBNP, hs-cTnT, and hs-cTnI was 41.0%, 63.4%, and 25.1%, respectively (Table 2, Fig. 2A), which reduced to 26.43%, 47.44%, and 19.23% after age standardization (Table 2, Fig. 2B). Furthermore, the prevalence of elevated cardiac biomarkers in the CKD group was significantly higher compared to the non-CKD group.

Significant correlations were found between elevated cardiac biomarkers and CKD after adjusting for age, gender, race, and education level in multivariable logistic regression models (Table 3). Further adjustment for cardiovascular and renal risk factors weakened the association but remained statistically significant. Additionally, noticeable differences in grades on the same cardiac biomarker were observed across different clinical categories (Table 3, NT-proBNP: 125- < 300 pg/mL vs ≥ 450 pg/mL: 1.65 vs 3.00). The association between NT-proBNP, hs-cTnT, and CKD persisted even after further adjustment for other cardiac biomarkers, while the correlation between hs-cTnI and CKD was no longer statistically significant (Table S1).

Restricted cubic spline plots were employed to visually represent the association between cardiac biomarkers and CKD on a continuous scale. After excluding extreme values, our findings demonstrated a significant correlation between NT-proBNP, hs-cTnT, hs-cTnI, and CKD (Fig. 3A-3C). It was observed that as the levels of cardiac biomarkers increased, the risk of CKD gradually increased. Significantly, these visualizations were consistent with the results of the multivariable regression analysis.

(A-C). Restricted cubic splines models demonstrating continuous association of cardiac biomarkers with CKD, NHANES 1999 to 2004. Models were adjusted for age, gender, race, education level, smoking, BMI, hypertension, TC, TG, HDL-C, urea, Ua, FBG, HbA1c, hs-CRP, eGFR, albuminuria, diabetes, and medication use.

The subgroups analysis indicated a positive correlation between elevated NT-proBNP and hs-cTnI and CKD in almost all subgroups (Fig. 4A, Fig. 4C). Moreover, significant differences were observed in different genders (hs-cTnI: P = 0.009 for interaction). Conversely, no significant association was found between hs-cTnT and CKD in some subgroups (Fig. 4B), with significant differences observed between younger and older individuals (P = 0.009 for interaction). Furthermore, the sensitivity analysis indicated a significant association between elevated cardiac biomarkers and CKD, which is consistent with the results of the multivariate regression analysis in the main analysis (Table S2).

Based on the follow-up data, the cumulative mortality rate was 16.5% in the non-CKD group, compared to 54.1% in the CKD group. Elevated cardiac biomarkers (Table 4, Fig. 5A-5F) were found to be linked to higher all-cause mortality risk in both groups. Competing risk models and cumulative incidence function analysis highlighted a positive association between elevated cardiac biomarkers (Table 4, Fig. 6A-6F, except for hs-cTnT: 6– < 14 ng/L; hs-cTnI: male, 6–12 ng/L; female, 4–10 ng/L) and increased cardiovascular mortality in individuals with CKD.

In addition, we compared the relationship between elevated hs-cTnI detected by three different methodologies and CKD. The results showed that the detection methods did not significantly affect the correlation between elevated hs-cTnI and CKD. Additionally, Additionally, patients with CKD showed an increased cumulative incidence of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality associated with elevated hs-cTnI levels detected by different methods (except for hs-cTnI (Ortho)) (Table S3, Table S4).

Discussion

Among US adults without known cardiovascular disease, individuals with CKD exhibited a higher prevalence of elevated cardiac biomarkers compared to those without CKD. Specifically, after age standardization, the prevalence rates for elevated NT-proBNP, hs-cTnI (Abbott), and hs-cTnT were found to be 26.43%, 19.23%, and 47.44%, respectively. We believe that this finding may be attributed to the fact that the myocardial injury threshold values specified by the manufacturers for hs-cTnT are not applicable across the entire age range of the primary prevention population. Theoretically, the threshold defining elevated hs-cTnT is based on the 99th percentile concentration from healthy reference samples; however, the myocardial injury thresholds recommended by manufacturers may not be generalizable to the entire primary prevention population. According to the NHANES website, the lower detection limit for hs-cTnT (Roche) is 3 ng/L, while for hs-cTnI (Abbott), it is 1.7 ng/L. The higher detection limit for hs-cTnT may lead to a larger proportion of the population being identified as at risk, which may explain the significantly higher prevalence of elevated hs-cTnT compared to NT-proBNP or hs-cTnI.

NT-proBNP, hs-cTnT and hs-cTnI are well-established biomarkers in CVD used for early detection and diagnosis of adverse events like heart failure and myocardial infarction. The presence of CKD significantly raises the risk of cardiovascular complications when compared to individuals without CKD27,28,29. CKD patients often have multiple CVD risk factors such as hypertension, dyslipidemia, and endothelial dysfunction30,31,32, along with disruptions in water-electrolyte balance and calcium-phosphate metabolism inherent to CKD33, further increasing cardiovascular risk. Elevated cardiac biomarkers were linked to higher long-term all-cause and cardiovascular mortality rates in the study, highlighting the need for accurate risk assessment and preventive strategies because of the substantial differences in mortality risks between CKD and non-CKD groups.

After adjusting for cardiovascular and renal risk factors, notable associations were observed between elevated NT-proBNP with CKD, aligning with previous research outcomes34,35. Multiple studies have indicated that elevated NT-proBNP levels in the CKD population are linked to cardiovascular risks, including heart failure and atrial fibrillation, and are independently correlated with increased risks of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality5,12. It is generally believed that a decrease in renal clearance may potentially lead to an increase in NT-proBNP levels, which may not accurately reflect actual acute heart failure events in CKD individuals. However, our study also examined the relationship between NT-proBNP and mortality risk in individuals without CKD, which were in line with those observed in the CKD group. These conclusions support previous research and suggest that monitoring for cardiac biomarkers may be beneficial in predicting adverse outcomes.

We observed strong associations between hs-cTnT, hs-cTnI with long-term mortality risk in individuals with CKD, even after considering other cardiac biomarkers. Previous research has reported an increased risk of mortality in CKD individuals associated with longitudinally measured hs-cTn36,37, which aligned with our findings. However, it is important to note that most of these studies focused on individuals with a known history of cardiovascular disease29,38,39. In contrast, we examined the relationships between cardiac biomarkers and mortality risk in a large sample population without known cardiovascular disease, which is a significant strength of our study. The pathological and physiological mechanisms underlying the elevated hs-cTn in CKD remain unclear. Nevertheless, implementing more robust intervention strategies for managing risk factors could be beneficial. Recent findings from randomized clinical trials40 have substantiated a notable elevation in hs-cTn concentrations as kidney function declines, and this observation is largely independent of acute myocardial infarction occurrences.

Furthermore, we observed that the prevalence of elevated hs-cTnT was higher than hs-cTnI in both the populations with CKD and without CKD, consistent with previous studies in individuals with diabetes or peripheral artery disease19,20. To detect hs-cTnI, we employed three distinct assay kits provided by Abbott, Ortho, and Roche. The criterion for diagnosing elevated hs-cTnI was established as concentrations exceeding the 99th percentile in a healthy population, as recommended by each assay’s manufacturers. Despite variations in the thresholds for elevated hs-cTnI, our study findings remained unaffected.

Moreover, we recognize that both hs-cTnT and hs-cTnI are utilized for the rapid diagnosis and screening of clinical cardiovascular events. However, it is important to note that the predictive value of these two cardiac biomarkers provides complementary risk information rather than redundant risk information41. Early studies have shown that hs-cTnT is associated with all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality, particularly demonstrating a strong correlation with progressive heart failure and cardiac structural abnormalities42, while its association with coronary atherosclerotic burden is significant but relatively weaker43. In contrast, hs-cTnI exhibits a more pronounced association with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease44. Furthermore, in supplementary studies, even after adjusting for different hs-cTn, we observed significant associations between both hs-cTn and all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality risks across different populations (Table S4). Therefore, we believe that hs-cTnT reflects the risk of structural changes in the heart, while hs-cTnI may represent the burden of atherosclerosis. Nevertheless, despite the significant differences in their positive prevalence rates, both cardiac biomarkers provide additional independent information regarding the risks of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality in the general adult population, aiding in more accurate risk stratification of high-risk groups during clinical assessment.

The findings of our study hold several significant clinical implications. The observed links between elevated cardiac biomarkers and CKD in individuals without known cardiovascular diseases may provide new guidance for risk stratification of adverse outcomes in clinical CKD individuals and offer recommendations for the development of preventive strategies. The associations between elevated cardiac biomarkers and long-term mortality risk in both the general population and those with CKD further strengthen the case for regular screening and monitoring of cardiac biomarkers, as well as the effectiveness and necessity of treating elevated cardiac biomarkers. Additionally, the significant elevation of cardiac biomarkers in CKD individuals suggests the need for further exploration of the potential key biological mechanisms between the two, and future prospective studies and randomized experiments are needed to validate our findings.

Our study has several strengths. Firstly, we utilized nationally representative and racially diverse data samples from NHANES for the first time. Secondly, through long-term follow-up and adjustment for confounding factors, we identified the associations between elevated cardiac biomarkers and the risk of CKD and the risk of long-term mortality. These observations carry significant clinical implications as they support the timely identification of individuals at high risk and foster the development of intervention strategies that employ cardiac biomarkers. Undoubtedly, this represents a remarkable strength of our study.

Certain limitations should be acknowledged in our study. Firstly, due to the observational nature of our research, we are unable to establish causality for the relationships we have identified. Further investigation is necessary to confirm these findings. Secondly, the history of cardiovascular disease in adults is often based on self-reported diagnoses, which may introduce errors because of the subjective biases of the participants and result in misclassification. Lastly, despite our efforts to minimize confounding factors through the use of multivariable regression models, there is a possibility of residual confounding that may persist.

In conclusion, the results of this study indicate that elevated cardiac biomarkers provide significant prognostic values for individuals without known cardiovascular disease, including those with and without CKD. This highlights the importance of strengthening the risk stratification strategies across diverse populations. Particularly, elevated cardiac biomarkers may serve as crucial risk indicators in the general population. Therefore, cardiac biomarkers holds potential for early risk identification and prognostic assessment.

Data availability

The data supporting the study findings are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Snyder, J. J., Foley, R. N. & Collins, A. J. Prevalence of CKD in the United States: a sensitivity analysis using the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999–2004. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 53(2), 218–228. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.07.034 (2009).

Ricardo, A. C. et al. Prevalence and Correlates of CKD in Hispanics/Latinos in the United States. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 10(10), 1757–1766. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.02020215 (2015).

Chu, N. M. et al. Chronic kidney disease, physical activity and cognitive function in older adults-results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2011–2014). Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 37(11), 2180–2189. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfab338 (2022).

Park, M. et al. Associations between kidney function and subclinical cardiac abnormalities in CKD. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 23(10), 1725–1734. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2012020145 (2012).

Go, A. S. et al. Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. N. Engl. J. Med. 351(13), 1296–1305. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa041031 (2004).

Li, W. J. et al. Cardiac troponin and C-reactive protein for predicting all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease: A meta-analysis. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 70(4), 301–311. https://doi.org/10.6061/clinics/2015(04)14 (2015).

Tonelli, M. et al. Chronic kidney disease and mortality risk: A systematic review. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 17(7), 2034–2047. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2005101085 (2006).

Stacy, S. R. et al. Role of troponin in patients with chronic kidney disease and suspected acute coronary syndrome: A systematic review. Ann. Intern. Med. 161(7), 502–512. https://doi.org/10.7326/M14-0746 (2014).

Bansal, N. et al. High-sensitivity troponin T and N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) and risk of incident heart failure in patients with CKD: The Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 26(4), 946–956. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2014010108 (2015).

Spanaus, K. S. et al. B-type natriuretic peptide concentrations predict the progression of nondiabetic chronic kidney disease: The Mild-to-Moderate Kidney Disease Study. Clin. Chem. 53(7), 1264–1272. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2006.083170 (2007).

Matsushita, K. et al. Cardiac and kidney markers for cardiovascular prediction in individuals with chronic kidney disease: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 34(8), 1770–1777. https://doi.org/10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.303465 (2014).

Bansal, N. et al. Change in Cardiac Biomarkers and Risk of Incident Heart Failure and Atrial Fibrillation in CKD: The Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 77(6), 907–919. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2020.09.021 (2021).

Hemmert, K. C. & Sun, B. C. High-Sensitivity Cardiac Troponin Assay in Patients With Kidney Impairment: A Challenge to Clinical Implementation. JAMA Intern. Med. 181(9), 1239–1241. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.1194 (2021).

Filippi, C. R. & Herzog, C. A. Interpreting Cardiac Biomarkers in the Setting of Chronic Kidney Disease. Clin. Chem. 63(1), 59–65. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2016.254748 (2017) (Epub 2016 Nov 3 PMID: 27811207).

Han, X. et al. Cardiac biomarkers of heart failure in chronic kidney disease. Clin. Chim. Acta. 510, 298–310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2020.07.040 (2020).

Skalsky, K., Shiyovich, A., Steinmetz, T. & Kornowski, R. Chronic Renal Failure and Cardiovascular Disease: A Comprehensive Appraisal. J. Clin. Med. 11(5), 1335. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11051335 (2022).

Gallacher, P. J. et al. High-sensitivity cardiac troponin and the diagnosis of myocardial infarction in patients with kidney impairment. Kidney Int. 102(1), 149–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2022.02.019 (2022).

McEvoy, J. W. et al. High-sensitivity troponins and mortality in the general population. Eur. Heart J. 44(28), 2595–2605. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehad328 (2023).

Fang, M. et al. Subclinical Cardiovascular Disease in US Adults With and Without Diabetes. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 12(11), e029083. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.122.029083 (2023).

Hicks, C. W. et al. Associations of Cardiac Biomarkers With Peripheral Artery Disease and Peripheral Neuropathy in US Adults Without Prevalent Cardiovascular Disease. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 43(8), 1583–1591. https://doi.org/10.1161/ATVBAHA.122.318774 (2023).

Inker, L. A. et al. CKD-EPI and EKFC GFR Estimating Equations: Performance and Other Considerations for Selecting Equations for Implementation in Adults. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.0000000000000227 (2023).

Genzen, J. R. et al. An Update on Reported Adoption of 2021 CKD-EPI Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate Equations. Clin. Chem. 69(10), 1197–1199. https://doi.org/10.1093/clinchem/hvad116 (2023).

Barzilay, J. I. et al. Hospitalization Rates in Older Adults With Albuminuria: The Cardiovascular Health Study. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 75(12), 2426–2433. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glaa020 (2020).

Ricardo, A. C. et al. Association of Sleep Duration, Symptoms, and Disorders with Mortality in Adults with Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int. Rep. 2(5), 866–873. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ekir.2017.05.002 (2017).

Tuttle, K. R. et al. Incidence of Chronic Kidney Disease among Adults with Diabetes, 2015–2020. N. Engl. J. Med. 387(15), 1430–1431. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc2207018 (2022).

Johnson CL, Paulose-Ram R, Ogden CL, et al. National health and nutrition examination survey: analytic guidelines, 1999–2010. Vital Health Stat 2. (161):1–24 (2013)

Wang, K. et al. Cardiac Biomarkers and Risk of Mortality in CKD (the CRIC Study). Kidney Int. Rep. 5(11), 2002–2012. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ekir.2020.08.028 (2020).

Untersteller, K. et al. NT-proBNP and Echocardiographic Parameters for Prediction of Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients with CKD Stages G2–G4. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 11(11), 1978–1988. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.01660216 (2016).

Miller-Hodges, E. et al. High-Sensitivity Cardiac Troponin and the Risk Stratification of Patients With Renal Impairment Presenting With Suspected Acute Coronary Syndrome. Circulation 137(5), 425–435. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.030320 (2018).

Georgianos, P. I. & Agarwal, R. Hypertension in Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD): Diagnosis, Classification, and Therapeutic Targets. Am. J. Hypertens. 34(4), 318–326. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajh/hpaa209 (2021).

Suh, S. H. & Kim, S. W. Dyslipidemia in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease: An Updated Overview. Diabetes Metab. J. 47(5), 612–629. https://doi.org/10.4093/dmj.2023.0067 (2023).

Su, H. et al. LncRNA ANRIL mediates endothelial dysfunction through BDNF downregulation in chronic kidney disease. Cell Death Dis. 13(7), 661. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-022-05068-1 (2022).

Nakanishi, T., Nanami, M. & Kuragano, T. The pathogenesis of CKD complications; Attack of dysregulated iron and phosphate metabolism. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 157, 55–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2020.01.024 (2020).

Bansal, N. et al. Upper Reference Limits for High-Sensitivity Cardiac Troponin T and N-Terminal Fragment of the Prohormone Brain Natriuretic Peptide in Patients With CKD. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 79(3), 383–392. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2021.06.017 (2022).

Park, M. et al. Associations of N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide with kidney function decline in persons without clinical heart failure in the Heart and Soul Study. Am. Heart J. 168(6), 931–9.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2014.09.008 (2014).

Chesnaye, N. C. et al. Association of Longitudinal High-Sensitivity Troponin T With Mortality in Patients With Chronic Kidney Disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 79(4), 327–336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2021.11.023 (2022).

Chesnaye, N. C. et al. Association Between Renal Function and Troponin T Over Time in Stable Chronic Kidney Disease Patients. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 8(21), e013091. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.119.013091 (2019).

Sandesara, P. B. et al. Comparison of the Association Between High-Sensitivity Troponin I and Adverse Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients With Versus Without Chronic Kidney Disease. Am. J. Cardiol. 121(12), 1461–1466. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2018.02.039 (2018).

Janus, S. E., Hajjari, J. & Al-Kindi, S. G. High Sensitivity Troponin and Risk of Incident Peripheral Arterial Disease in Chronic Kidney Disease (from the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort [CRIC] Study). Am. J. Cardiol. 125(4), 630–635. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2019.11.019 (2020).

Gallacher, P. J. et al. Use of High-Sensitivity Cardiac Troponin in Patients With Kidney Impairment: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern. Med. 181(9), 1237–1239. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.1184 (2021).

de Lemos, J. A. & Berry, J. D. Comparisons of multiple troponin assays for detecting chronic myocardial injury in the general population: Redundant or complementary?. Eur. Heart J. 44(28), 2606–2608. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehad414 (2023).

Latini, R. et al. Prognostic value of very low plasma concentrations of troponin T in patients with stable chronic heart failure. Circulation 116(11), 1242–1249. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.655076 (2007).

de Lemos, J. A. et al. Association of troponin T detected with a highly sensitive assay and cardiac structure and mortality risk in the general population. JAMA 304(22), 2503–2512. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2010.1768 (2010).

Jia, X. et al. High-Sensitivity Troponin I and Incident Coronary Events, Stroke, Heart Failure Hospitalization, and Mortality in the ARIC Study. Circulation 139(23), 2642–2653. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.038772 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We extend our gratitude to the researchers from Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, for their invaluable contribution to cardiac biomarkers testing.

Funding

National Natural Science Foundation of China,81973824,Jiangsu Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine,k2021j17-2,Jiangsu Province Hospital of Chinese Medicine,y2021rc06.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HTX, SW and LQ contributed to the data collection, analysis and designed of this study; PY and XHC organized and supervised this study; HTX, SW and LQ were responsible for the statistical analysis and for writing the report. LS, SHT are the correspondent authors of this report. All authors contributed to the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data. HTX, SW and LQ drafted the manuscript. All authors revised the report and approved the final version before submission. HTX, SW and LQ contributed equally to this work and should be considered as co-first authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

NHANES was approved by the National Center for Health Statistics Ethics Review Board. This study used previously collected deidentified data, which is deemed exempt from review by the Ethics Committee at Jiangsu Province Hospital of Chinese Medicine.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xie, H., Wang, S., Qian, L. et al. Associations of cardiac biomarkers with chronic kidney disease and mortality in US individuals without prevalent cardiovascular disease. Sci Rep 15, 15001 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98506-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98506-x

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Enhancing cardiac disease detection via a fusion of machine learning and medical imaging

Scientific Reports (2025)