Abstract

There are reports on resistance to metals by the Microbacteriaceae family, although few studies have focused on the Microbacterium genus. The present work is one of the first studies related to arsenic (As) resistance and removal by Microbacterium hydrocarbonoxydans. Growth curves were performed simultaneously as follows: (1) growth kinetics without As, and (2) growth kinetics added with As(III). Incubation conditions were at 30 °C and 120 rpm for 168 h, with an inoculation of bacterial culture, 107 (CFU)/ml. Absorbance was measured at 600 nm in an ultraviolet (UV)–vis spectrophotometer. The As surface adsorption and uptake into bacterial cells, exposed to As(III), were confirmed through SEM, EDX, and FTIR analyses. It was observed that the cellular morphology of M. hydrocarbonoxydans through TEM was deformed when exposed to high concentrations of arsenite. Bacterial cells growing in a rich medium with As(III) were able to oxidize 98% As(III), and the inactivated biomass of the bacterium exhibited a high removal capacity. Likewise, M. hydrocarbonoxydans was employed to test its ability to remove other toxic heavy metals such as lead, cadmium, and chromium. The order of resistance of each metal was as follows: Cr VI (2.08 gL−1) > Pb (1.24 gL−1) > Cd (0.169 gL−1). This work demonstrated that the strain M. hydrocarbonoxydans has high arsenic resistance and removal capacity, as well as significant As(III) oxidation potential, rendering it a promising candidate for biotechnological application in the development of affordable systems for the removal of metals/metalloids from contaminated sites.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Arsenic (As) in water is one of the major global environmental health problems, due to its wide distribution in the natural environment and its ability to reach harmful concentrations in various regions of the world1. In addition to its toxicity, As is considered a potential carcinogen, which further aggravates the severity of its impact on public health. The presence of As particularly affects developing countries such as those in Southeast Asia and Latin America. In the Latin-American region, As affects an estimated 14 million inhabitants, with Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and Mexico the most affected countries2. In the field of As removal treatments, the application of biotechnology has attracted significant interest due to the implementation of process systems that are sustainable and affordable for As removal in contaminated areas3,4. For example, the combination of biological mechanisms, such as the bacterial oxidation of arsenite As(III) into As(V), and chemical processes with natural materials, could constitute a decentralized water-treatment system for As removal5,6. Microorganisms present in As-contaminated sites have developed different metabolic activities to resist and somewhat adapt to the toxic effects of this metalloid7,8. Previous work has shown that the redox transformation of As is mainly regulated by microorganisms. These reactions are carried out by the ars and aox genes. which generally co-exist in aerobic environments and code for the enzyme’s arsenate reductase and arsenite oxidase, respectively6,9,10.

Bacteria belonging to the phylum Actinobacteria have played a crucial role in the removal and elimination of As species in aqueous media. Within this phylum, we find the Microbacteriaceae Family, to which the genus Microbacterium belongs11,12. To our knowledge, there has been scarce work on the biotechnological applications of Microbacterium sp. in the resistance of heavy metals and metalloids in aqueous media6,13,14. However, recent studies have demonstrated the remarkable ability of the genus Microbacterium sp. to remove As6. One study demonstrated that Microbacterium sp. 1S1 has a chemoautotrophic metabolism that allows it to accept electrons from As(III) for energy production13. Another study observed that the production of biogenic manganese oxides (BMOx) by Microbacterium sp. CsA40 contributed to the removal of As(III) from water, due to its ability to oxidize and adsorb As15. One work determined the tolerance and toxicity on increasing doses of fluoride, either individually or in combination with As by the bacterium Microbacterium paraoxydans strain IR-116. The minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) and the mean maximal inhibitory concentration (MIC50) values for fluoride increased from 9 to 11 gL−1 and from 5.91 ± 0.1 to 6.32 ± 0.028 gL−1, respectively, in the combination group (F + As). Statistical comparison of the observed and expected additive toxicities, Regarding the difference in toxicity units (TU), using the Student t test, it was found to be highly significant (p < 0.001). This suggested the antagonistic effect of As on fluoride toxicity for strain IR-1. Another study revealed that oxidation of As(III) in groundwater by a column immobilized with Microbacterium lacticum, followed by its removal by activated carbon, could be an effective method for the treatment of As(III)-contaminated groundwater6. Therefore, studies of Microbacterium species are of great importance in the biotechnological application for bioremediation proposals in As-contaminated sites.

Currently, to our knowledge, there is no published work on the removal efficiency, resistance and biotransformation of As(III) by Microbacterium hydrocarbonoxydans. As a background to the follow-up of this work, the authors published that M. hydrocarbonoxydans, under analysis with other bacteria, presented a high capacity to remove As(III) in aqueous media of 79.9 ± 1.3%7.

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the resistance and removal of As(III) by M. hydrocarbonoxydans using Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR), Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDX), Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) and Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM), as well as molecular techniques to verify the biotransformation of As through the presence of the genes encoding the enzyme arsenite oxidase.

Methods

Culture media

Nutrient Broth (NB) medium contains 5 gL−1 peptone, 3 gL−1 beef extract, and the pH value was adjusted to 8.0. NA plates were prepared with NB medium with 20 gL−1 Bacto-Agar.

Terrific Broth (TB) medium contains 24 gL−1 yeast extract,20 gL−1 tryptone, and 5.04 gL−1 glycerol; the pH value was adjusted to 8.0. This mixture was stirred until the solutes were dissolved in 900 ml of deionized water and sterilized by autoclaving for 15 min at 15 psi (1.05 kgcm−2). The solution was allowed to become cool to ∼55 °C, and 100 mL of sterile phosphate buffer was added.

Peptone, Yeast Extract and Tryptone (PYT) medium contains 0.4 gL−1 of peptone, 0.4 gL−1 of yeast extract, 0.4 mg L−1 of tryptone, 1 gL−1 of KNO₃, and 10 ml L−1 of glucose (1 M).

Phosphate buffer contains 0.17 M KH2PO4 and 0.72 M K2HPO4.

Minimum Salt Medium (MSM) contains 2.27 gL−1 K2HPO4, 0.95 gL−1 KH2PO4, 0.67 gL−1 (NH₄) ₂SO₄, and 2 ml L−1 metals solution (Na2EDTA.2H2O, ZnSO4.7H2O, CaCl2.2H2O, FeSO4.7H2O, NaMoO4.2H2O, CuSO4.5H2O, CoCl2.6H2O, MnSO4.H2O, and MgSO4.7H2O).

Müller Hinton Agar (MH) medium contains 300 gL−1 beef infusion solids, 17.5 gL−1 hydrolyzed casein peptone,1.5 gL−1 starch, and 17.0 gL−1 agar. The pH value was adjusted to 7.0.

Bacterial strain

The M. hydrocarbonoxydans strain was isolated from Xichu River, Guanajuato State. Mexico. This river is contaminated with several heavy metals and metalloids, including As. This strain was molecularly identified by previous work7. Regarding sufficient biomass production, the bacterial strain was inoculated in TB medium pH 8.0; the incubation conditions were 37 °C at 120 rpm for 48 h8.

Determination of the minimal inhibitory concentration of arsenic

The minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) is the lowest concentration of both inorganic As species that completely inhibit growth. MIC for the bacterial strain was determined in Nutrient broth (NB) that contained different concentrations of As(III). These concentrations ranged from 1 to 20 mm. The medium was inoculated with cell suspensions taken from fresh cultures in the logarithmic phase and incubated at 30 °C for 96 h at 120 rpm (Themo Scientific Max q 4000, USA). The following experiments were subsequently prepared: (i) NB culture medium inoculated with bacteria only; (ii) NB culture medium inoculated with bacteria in the presence of arsenite (AsIII), and (iii) NB culture medium inoculated with bacteria in the presence of arsenate (AsV); two controls were prepared for each experiment. The optical density (OD) of the cell cultures was taken at 24 h intervals for 96 h to determine bacterial-growth responses at different concentrations of As(III) and As(V). Bacterial growth was measured by determining OD at 600 nm (OD600) in a UV–Vis Spectrophotometer (DR 3900, Hach, USA). Assays were carried out in triplicate.

Metal cross-resistance

The M. hydrocarbonoxydans strain was selected for its capability to resist other toxic metal ions such as cadmium (Cd), chromium (Cr), and lead (Pb). For this purpose, Luria–Bertani (LB)-agar pH 8.0 was employed, and it was supplemented with various concentrations (0.1–2.5 gL−1) of Cd, Cr, and Pb. These plaques were inoculated with M. hydrocarbonoxydans and then incubated at 37 °C during 24–48 h13. The bacteria were subsequently transferred into liquid media PYT pH 8 at incubation conditions of 37 °C at 120 rpm during 48 h.

Arsenite oxidation determination

The As transforming potential was evaluated using the qualitative assessment of the AgNO3 method. First, a fresh culture in TB medium in stationary phase was obtained, which was centrifuged and washed twice with minimal salt medium (MSM). The obtained pellet was reinoculated in MSM containing 1.8 gL−1 glucose and 0.075 gL−1 As(III). Bacterium suspension (OD600 = 0.3) was incubated at 30 °C for 72 h. Then, the culture was re-centrifuged and a total of 100 µl of supernatant was added to 100 µl of 1 M AgNO3. After the reaction, the light brown chemical sediment indicated the formation of silver arsenate (Ag3AsO4) and the presence of As(V). The light yellow sediment indicated the formation of silver arsenite (Ag3AsO3) and the presence of As(III)17.

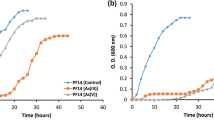

Growth curves in the presence of As(III)

This assay was carried out simultaneously with the As(III) removal assay. Growth kinetics were planned for 30 ml of M9 medium, with an aliquot culture taken every 24 h. The experiments were carried out as follows: (1) growth kinetics without As, and (2) growth kinetics in M9 added with As(III). The concentration of As was defined according to the result obtained by the MIC. Incubation conditions in polypropylene tubes included inoculate of bacterial culture (cell density of 107 CFU/ml) at 30 °C and 120 rpm for 168 h. Absorbance was measured at 600 nm in a UV–Vis Spectrophotometer (DR 3900, Hach, USA).

Arsenite removal assay

To determine the cellular As accumulation in M. hydrocarbonoxydans, a fresh culture suspension was inoculated into M9 pH 8.0, supplemented with 100, 200, and 500 mgL−1 of As(III) (NaAsO2) and incubated at 28 °C and 120 rpm during 144 h on a rotary18. At this point, it is noteworthy that each aliquot taken every 24 h was centrifuged and washed with deionized water. Bacterial-cell pellets and the supernatant were acid-digested followed by the quantification of total As using an atomic absorption spectrometer (AAS-HG, Pinnacle 900, Perkin Elmer). A control without bacterial inoculation was maintained to monitor the artifacts resulting from the abiotic chelation of As(III). The removal (bioaccumulation) of As(III) in percentage was computed by using Eq. (1) as follows18:

FTIR analysis

Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) was employed to analyze the functional groups on arsenic-free bacterial biomass (control) and bacterial biomass with As (treated). The FTIR samples were prepared using the bacterial pellet resuspended in MSM with 0.62 and 1.24 gL−1 of sodium arsenite. The incubation conditions were 37 °C at 120 rpm during 72 h. The bacterial biomass samples were prepared by the centrifugation of the bacterial cells and drying at 37 °C. Spectral analysis was carried out within the range of 450–4,000 cm−1 by utilizing Spectrum Two IR Spectrometer PerkinElmer. The signals above 650 cm−1 were the only signals considered due to that an ATR (Attenuated Total Reflectance) was implemented18,19,20.

SEM, TEM, and EDX analyses

To study the effect of As(III) on cell-surface characteristics and to detect changes in cell morphology under stress conditions, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) were performed. In summary, bacteria were grown in As(III)-free BSM broth and in medium supplemented with 1.5 gL−1 As(III). Cells were harvested after 48 h of incubation by centrifugation at 6,000 rpm (Sher et al., 2022). Bacterial cultures were washed twice with PBS buffer; then the cells were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde for 4 h followed by 3–4 washing steps with PBS. Finally, the samples were dehydrated with increasing ethanol concentrations (10–100%), after which the dried samples were mounted on an SEM bracket and coated with gold. The samples were then taken for chemical microanalysis by energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX). A JEOL/JSM-6010 PLUS/LA scanning electron microscope (operated at 15 kV, under vacuum) was employed. To confirm the intracellular accumulation of As(III), arsenite-free cells and cells treated with arsenite were analyzed by TEM (ZEISS LIBRA 120 with energy filter). It should be noted that in the samples for TEM, the bacteria were grown and harvested as previously described for SEM sample preparation21.

Antibiotic resistance

Müller-Hinton Agar (MH) is a medium used to verify the susceptibility of bacteria to antimicrobial agents by the method of diffusion (Kirby-Bauer method) or by dilution in agar22,23. The diluted samples are seeded directly onto the surface of the MH-agar plate, spreading these with the aid of a stainless-steel bacterial cell spreader. The cell suspension is left on the surface for 5 min to allow its absorption into the agar, and then a sensitive disk (Multibac Combined PT36 I.D.®) is placed on each inoculated plate. The sensitive disk consists of 12 combined antimicrobials for Gram + and Gram-; 30 μg AK (Amikacin); 30 μg AM (Ampicillin); 30 μg CF (Cephalothin); 30 μg CFX (Cefotaxime); 1 μg DC (Dicloxacillin); 30 μg CTX (Ceftriaxone); 30 μg CL (Chloramphenicol); 10 μg GE (Gentamicin); 30 μg NET (Netylmycin); 300 μg NF (Nitrofurantoin); 10 U PE (Penicillin), and 25 μg STX (Sulfamethoxazole/Trimethoprim). After incubation (35ºC for 18 h), the diameter of the inhibition zone surrounding each disk is measured, each microorganism‒antibiotic combination has different diameters that imply whether it is sensitive (S) or resistant (R).

Characterization of the arsenite oxidation gene (aox AB)

The DNA of M. hydrocarbonoxydans was extracted based on the technique with cetyl trimethyl ammonium bromide (CTAB)/NaCl24,25. Subsequently, the extraction was verified by electrophoresis in 1.0% agarose gel to certify the concentration and quality of the genomic DNA. This DNA was used as a template for the detection of aox (arsenite oxidase) AB through PCR amplification with the following primers: aoxA (5′-TTCGCTGCTTTTTCATTTTG-3′) and aox B (5′-TGTGATCTCCACAGCATACG-3′)9. The amplification program was set to the following conditions. First, the initial denaturation temperature was 94 °C/3 min (1 cycle). The temperature was then cycled to 94 °C/30 s, to 60 °C/40 s, and to 72 °C/1 min. This process was repeated for 30 cycles, followed by a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. Finally, the amplification was displayed in a 1.0% agarose gel stained with EtBr7.

Statistical analysis

Initially, the determination of normality (Shapiro–Wilk test), homogeneity (Barlett test), and the independence of the data was carried out (Durbin-Watson test)26,27. The experiments in this study were performed in triplicate (n = 3). The values of growth kinetics are given as mean + standard deviation (SD) using Microsoft Excel version 2010 software. Data obtained from the factorial design were analyzed by the 2-way analysis of variance test (ANOVA) to test the significance of bacterial growth in the presence of As(III) and As(V). Tukey multiple range test was performed to identify the strains with the highest potential for interaction with As(III) and As(V) and their optimal growth times. The significance of the differences was defined as p > 0.005, with a 95% confidence interval (95% CI), using Minitab version 19 software28.

Results

Morphological characteristics of the strain

M. hydrocarbonoxydans is Gram-positive12and its colonies are circular, smooth, translucent, and yellow-pigmented (Figure S1).

Determination of the minimal inhibitory concentration of arsenic (MIC)

Tolerance of the strain to As(III) was tested by determining its minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC). As in previous works, M. hydrocarbonoxydans demonstrated favorable growth in Nutrient Broth (NB) added with 0.75 gL−1 As(III). The order of resistance at the different concentrations-under-study were 0.0750, 0.375, and 0.748 gL−1. These exhibited an average growth of 89.2 ± 5.22, 84.83 ± 2.20, and 63.82 ± 1.41%, respectively (Fig. 1). Bacterial growth decreased in media enriched with 0.897 and 1.5 gL−1 As. This implies growth rates of 12.7 ± 0.99% and 6.38 ± 1.1%, respectively. In both concentrations, the growth was nearly flat. The percentage analysis was in relation to the growth of the control group. Previous work has reported that the genus of this species is highly resistant to As18. It is important to highlight that, to our knowledge, there are few works referring to the study of the resistance of M. hydrocarbonoxydans to culture media added with As7.

Growth kinetics of M. hydrocarbonoxydans in NB medium added with different concentrations of As (III): 1 mM (orange line), 5 mM (gray line), 10 mM (yellow line), 12 mM (light blue line) y 20 mM (green line). A control without arsenite is also included (dark blue top line). Three separate assays were performed. Error bars represent standard deviation.

Metal cross-resistance

Regarding the evaluation of the resistance of M. hydrocarbonoxydans in heavy metals (Fig. 2) such as chromium, lead, and cadmium (Cr, Pb, and Cd, respectively), the results obtained indicate that this bacterium has a greater resistance to chromium (Cr). The order of resistance of each metal was as follows: Cr VI (2.08 gL−1) > Pb (1.24 gL−1) > Cd (0.169 gL−1). These results agree with those reported by previous studies carried out on this genus of bacteria14.

Bacterial resistance to three different metals in nutrient agar (NA). The bacterium corresponding to this study, M. hydrocarbonoxydans, showed a higher resistance to chromium (2.08 gL−1), followed by lead (1.24 gL−1) and a higher sensitivity to cadmium (0.17 gL−1). The assay was performed in triplicate. The standard deviation is indicated by the error bars.

Determination of arsenite oxidation

To test the oxidizing capacity of M. hydrocarbonoxydans of arsenite (AsIII) into arsenate (AsV), the colorimetric Assay of AgNO3 was utilized (Figure S2). This culture plate shows the oxidation test of arsenite to arsenate with the bacterium M. hydrocarbonoxydans. In the corresponding well, a light brown precipitate is clearly observed, indicating that M. hydrocarbonoxidans carried out the As oxidation process.

Arsenite removal assay

The removal capacity of 100, 200 and 500 mgL-1 in terms of the bacterium was analyzed. The pH used was 8.5, in that this is the present average pH in the contaminated areas7,8. M. hydrocarbonoxydans exhibited a high removal capacity at all three concentrations, with an average of the maximal removals of 89.2 ± 6.53% in 72 h. However, the following should be considered (Fig. 3). For the removal of the 100 and 200 mgL−1 at 72 h, the concentrations in the aqueous medium decreased to 6.0 ± 0.1 and 8.1 ± 0.4 mgL−1. This previously mentioned information complies with Mexican and World Health Organization (WHO) standards for permissible limits (25 and 10 mgL−1, respectively). However, for 500 mgL−1 at 96 h, there is efficient removal (88 ± 2.4%). The concentration (59.9 ± 1.34 mgL−1) in the aqueous medium does not comply with the values of the permissible limits established in the regulations. In comparison with previous works21,29, the results obtained fell within the reported range, ranging from values above 48.43 to 90%.

A possible explanation for the As(III) removal capacity of M. hydrocarbonoxydans observed in this study is that it may present systems capable of reducing and oxidizing As. The transformation reactions are affected by the bacterial functional enzymes, but also by the reduction/oxidation potential of the medium. The medium is strongly influenced by the presence of microbial communities. Information is available on the redox cycling of As by microorganisms and plays an important role in controlling As speciation and mobility in high As environments7,18.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM), EDX, TEM, and FTIR analyses

FTIR analysis

In Table 1, the signals of different functional groups that interact with As(III) in the cellular membrane are observed. As a Gram-positive bacterium, the presences of peptidoglycan in membrane affords a plus to the adsorption process to the acid-to-acid technique. This process contains several functional groups18. Signals in the FTIR analysis were observed for the M. hydrocarbonoxydans biomass without As (control) and in the presence of As(III) (Fig. 4) (Table 1). In the biomass without As, signals were observed at 3,459.24 cm−1 corresponding to the hydroxyl (–OH) or amino (–NH) groups. Once the biomasses were treated with As(III), the signal practically disappeared. The observed peaks were 3,300.59, 3,207.19, and 2,922.56 cm−1, which are also attributed to hydroxyl groups and to the stretching bonds of the (–CH) group. According to the signals among the 1,645.24, 1,536.14, and 1,445.34 cm peaks, which correspond to the functional groups involved, to the stretching bonds of the carboxyl group (–C=O), and to the amino groups (-NH). The signals observed at 1,234.44, 1,099.12, and 1,052.62 cm−1 indicate the presence of single bonds such as the C–O bonds of alcohols, carboxylic acids, esters, and ethers, as well as the C–N bonds of an aliphatic amine. At 974.95, 913.52, 805.87, 696.69, and 494.37 cm−1 peaks, corresponding to the fingerprint region, single bonds such as C–C, C–N, and C–O are found. The most noticeable signal changes occur in the functional group region, indicating the involvement of hydroxyl, carboxyl, and amino groups mainly in the biosorption of As(III).

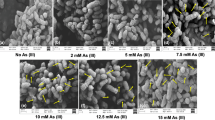

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)-EDS

The surface morphological changes of M. hydrocarbonoxydans with and without As(III) were observed with the aid of SEM–EDS. Figure 5 presents SEM micrographs of the bacteria grown in the absence (control) and the presence of As(III), respectively. The cells present a defined bacillary shape in the case of control conditions (Fig. 5a). These cells exhibited a distorted agglomerated morphology with undefined shapes and boundaries for the As(III)-treated cells (Fig. 5b). There is a notable presence of a biofilm on their surface in the arsenic-treated cells. It is probable that this is a form of defense of the microorganism against high concentrations of 1.5 gL−1 As(III). EDS spectral analysis confirmed the presence of As(III) in the bacteria.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

The bioaccumulation process was confirmed by AAS-HG, FTIR, and SEM and was corroborated by TEM analysis. It showed the accumulation of As(III) inside the cell (Fig. 6). The intracellular structural analysis of M. hydrocarbonoxydans by TEM clearly revealed that As(III) caused the disruption of the plasma membrane, condensation of the cytoplasm, and the presence of electron-dense deposits throughout the periplasm. The distinguishable alteration in cell morphology upon exposure to high concentrations of sodium arsenite (3.72 gL−1) can also be observed. It is noteworthy that this is, to our knowledge, the first time that this analysis has been performed on bacteria of the genus Microbacterium.

Antibiotic resistance

In the antibiogram test, M. hydrocarbonoxydans was mainly antibiotic-sensitive and only showed resistance to two antibiotics: NF (Nitrofurantoin) 300 μg and PE (Penicillin) 10 U, but it was sensitive to the following antibiotics: AK (Amikacin) 30 μg; AM (Ampicillin) 30 μg; CF (Cephalothin) 30 μg; CFX (Ciprofloxacin) 30 μg; DC (Dicloxacillin) 1 μg; CTX (Ceftriaxone) 30 μg; CL (Chloramphenicol) 30 μg; GE (Gentamicin) 10 μg; NET (Netylmycin) 30 μg, and STX (Sulfamethoxazole/Trimethoprim 25 μg (Figure S3) (Table 2).

There is strong evidence between As(III) resistance and antibiotic resistance by bacteria through the co-selection process. Metal-driven antibiotic-resistant determinants evolved in bacteria and present on same mobile genetic elements are horizontally transferred to distantly related bacterial human pathogens. It is interesting that the abundance of antibiotic-resistant genes is directly linked to the prevalence of metal concentration in the environment30. The proliferation of heavy metal-resistant bacteria can be a potential health problem due to horizontal gene transfer, causing a simultaneous tolerance that increases the potential risk in only one vector, that is, the water30,31.

Characterization of the arsenite oxidation gene (aox AB)

DNA purity was measured by reading a 260/280 ratio using a Beckman DU 640 spectrophotometer. All extracted DNA demonstrated an absorbance ratio (260 nm/280 nm) ranging from 1.8 to 2.0. The quality of the extraction of the M. hydrocarbonoxydans genomic DNA is depicted in Fig. 7, where it can be observed that the samples are clean and free of protein, salts, and Ribonucleases (RNases).

The presence of the aox AB gene within the chromosome of M. hydrocarbonoxydans was evaluated using PCR, and the lines that revealed genes are shown in the electrophoresis-gel patterns (Fig. 8).

Discussion

M. hydrocarbonoxydans presented high resistance to As(III). This was corroborated by multiple factors as follows: analysis of its growth kinetics in the presence or absence of As(III), and ANOVA statistical analysis and Tukey multiple comparisons analysis, predicting that there is no significant difference between bacterial growth in the presence or absence of As(III). This means that arsenite (As III) at a concentration of 200 µg L−1 does not significantly inhibit bacterial growth. As depicted in Fig. 1 with regard to its growth kinetics, M. hydrocarbonoxydans exhibited a practically non-existent adaptation phase (p < 0.05), followed by an exponential phase ranging from 0 to 24 h (p > 0.05), and that it entered its stationary phase within a time range of 24–120 h (p < 0.05).

Likewise, it was observed that M. hydrocarbonoxydans was able to perform a high removal of As (89% ± 0.56) in 24 h. This removal occurred in the lag-growth phase during which the adsorption and bioaccumulation processes of the metalloid take place. Due to that the bacterium possesses a membrane with anionic radicals such as (OH–), (C=O–), and (NH–), the bacterium could initiate As bioaccumulation through a passive process where As(III) was attracted and captured by these anionic radicals, and could continue with the active bioaccumulation process32. In parallel, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analyses were performed to detect the damage caused by As(III) in the bacteria at the cellular level. By means of this microscopy, it was possible to detect clearly the interaction that As(III) entertained with the bacterial cell. Figure 5b depicts the cells in contact with 2.24 gL−1 of As(III), identifying structural damage on the cell surface and demonstrating evident changes in the cells’ morphology.

According to previous reports, this strain of M. hydrocarbonoxydans is known to grow in the form of a biofilm at high concentrations of As(III)11. This type of microbial growth may occur in response to the interaction of the bacteria with As(III), which theoretically allows the bacteria to defend themselves against xenobiotic agents such as heavy metals and metalloids33,34. Bacterial biofilms are formed by extra-polymeric substances where various enzymatic activities can also take place35,36.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) detected the presence of As(III) in both the cell membrane (periplasm) and in the cytoplasm. This corroborated that M. hydrocarbonoxydans is able to bioaccumulate As(III), beginning with sorption at the cell membrane through the functional groups previously described, followed by an active process in which As(III) enters the cell through the Pit(III) channels18. This organism is able to oxidize As(III) in the membrane, while in the cytoplasm it accumulates it until it reaches a concentration that causes cell death. M. hydrocarbonoxydans is responsible for reducing As(V) inside the cell and then expelling it by means of the Ars A protein, which comprises an As(III) extrusion pump18.

Previous work has indicated that a microorganism’s resistance to metals and its sensitivity to antibiotics are related. Some of these metal or metalloid resistance mechanisms have also been demonstrated to confer resistance to antibiotics35,37,38. For example, ejector pumps, which remove metals from the cell, can also remove antibiotics from the cell39. In order to analyze the latter, in the present work, M. hydrocarbonoxydans was found to be sensitive to 10 of the 12 antibiotics used.

It is noteworthy that the sensitivity of a bacterium to an antibiotic depends not only on the nature of the antibiotic, but also on the concentration employed40. Some bacteria are naturally more sensitive to antibiotic concentrations than others, due to differences in their metabolism or to the presence of intrinsic resistance mechanisms to certain antibiotics, especially those with which they have not interacted37,40.

Compared to strains isolated from urban environments37,40,41, it is important to note that M. hydrocarbonoxydans is native to and originates from mining areas in marginalized populations7. Thus, it is possible that it engages in less interaction with a wide range of antibiotics and has only developed resistance to the most used antibiotics, such as Penicillin. M. hydrocarbonoxydans exhibited resistance to the following two antibiotics, Nitrofurantoin (NF) and Penicillin (PE), and may have developed genes conferring resistance to metals and antibiotics that are often found in the same mobile genetic elements (MGE), such as plasmids, transposons, integrons, chromosomes, and bacteriophages42.

Conclusion

This work has shown that the bacterial strain M. hydrocarbonoxydans, on interacting with As(III), possesses high resistance to As species and an efficient biotechnological capacity to remove As from water. SEM–EDS and TEM results revealed the presence of As in the cell membrane and in the cytoplasm of M. hydrocarbonoxydans. The appearance of brown precipitation upon interaction with AgNO₃ confirmed its ability to oxidize arsenite, which was further confirmed by the presence of aox genes encoding the enzyme arsenite oxidase. The presence of oxidative genes and their potential to biotransform As render this bacterium a possible candidate for the efficient removal of As from contaminated water. Therefore, this research is a valuable contribution to the knowledge of little-known strains and their possible use in the development of affordable technologies for decentralized contaminated water-treatment systems, as well as opening a wide field in the role of bacteria in the interaction of mobile genetic elements with metals, metalloids, and antibiotics, which may entertain significant implications for environmental health.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and in its Supplementary Information files].

References

Osuna-Martínez, C. C., Armienta, M. A., Bergés-Tiznado, M. E. & Páez-Osuna, F. Arsenic in waters, soils, sediments, and biota from Mexico: An environmental review. Sci. Total Environ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142062 (2021).

Bundschuh, J. et al. Arsenic in latin America: New findings on source, mobilization and mobility in human environments in 20 countries based on decadal research 2010–2020. Critic. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51(16), 1727–865 (2021).

Liu, Y., Ng, W. S. & Chen, M. Optimization of arsenic fixation in the pressure oxidation of arsenopyrite using response surface methodology. Mineral Process. Extract. Metall. Rev. 45, 101 (2024).

Di Caprio, F., Altimari, P., Astolfi, M. L. & Pagnanelli, F. Optimization of two-phase synthesis of Fe-hydrochar for arsenic removal from drinking water: Effect of temperature and Fe concentration. J. Environ. Manage. 351, 119834 (2024).

Xue, Y. et al. Arsenic bioremediation in mining wastewater by controllable genetically modified bacteria with biochar. Environ. Technol. Innov. 33, 103514 (2024).

Mokashi, S. A. & Paknikar, K. M. Arsenic (III) oxidizing Microbacterium lacticum and its use in the treatment of arsenic contaminated groundwater. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 34, 258 (2002).

Rodríguez-Castrejón, U. E., Serafin-Muñoz, A. H., Alvarez-Vargas, A., Cruz-Jímenez, G. & Noriega-Luna, B. Isolation and molecular identification of native As-resistant bacteria: As(III) and As(V) removal capacity and possible mechanism of detoxification. Arch. Microbiol. 204, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00203-022-02794-0 (2022).

Rodríguez Castrejón, U. E., Serafín Muñoz, A. H., Cano Canchola, C. & Álvarez Vargas, A. Microbial study related with the arsenic hydrogeochemistry of the Xichú River in Guanajuato, Mexico. in Environmental Arsenic in a ChangingWorld - 7th International Congress and Exhibition Arsenic in the Environment, 2018 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1201/9781351046633-54.

Muller, D., Lièvremont, D., Simeonova, D. D., Hubert, J. C. & Lett, M. C. Arsenite oxidase aox genes from a metal-resistant β-proteobacterium. J. Bacteriol. 185, 135 (2003).

Mohsin, H., Shafique, M., Zaid, M. & Rehman, Y. Microbial biochemical pathways of arsenic biotransformation and their application for bioremediation. Folia Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12223-023-01068-6 (2023).

Lee, S. D., Yang, H. L. & Kim, I. S. Four new Microbacterium species isolated from seaweeds and reclassification of five Microbacterium species with a proposal of Paramicrobacterium gen. nov. under a genome-based framework of the genus Microbacterium. Front. Microbiol. 18(14), 1299950 (2023).

Schippers, A., Bosecker, K., Spröer, C. & Schumann, P. Microbacterium oleivorans sp. Nov. and Microbacterium hydrocarbonoxydans sp. nov., novel crude-oil-degrading Gram-positive bacteria. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 55, 655–660 (2005).

Sher, S., Hussain, S. Z., Cheema, M. T., Hussain, A. & Rehman, A. Efficient removal potential of Microbacterium sp. strain 1S1 against arsenite isolated from polluted environment. J. King Saud. Univ. Sci. 34, 102066 (2022).

Corretto, E. et al. Comparative genomics of Microbacterium species to reveal diversity, potential for secondary metabolites and heavy metal resistance. Front. Microbiol. 11, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.01869 (2020).

Liang, G., Yang, Y., Wu, S., Jiang, Y. & Xu, Y. The generation of biogenic manganese oxides and its application in the removal of As(III) in groundwater. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 24, 17935–17944 (2017).

Mathur, M. et al. Effect of arsenic on fluoride tolerance in Microbacterium paraoxydans strain IR-1. Toxics 11, 945 (2023).

Jebelli, M. A. et al. Isolation and identification of the native population bacteria for bioremediation of high levels of arsenic from water resources. J. Environ. Manage 212, 39–45 (2018).

Kumari, N., Rana, A. & Jagadevan, S. Arsenite biotransformation by Rhodococcus sp.: Characterization, optimization using response surface methodology and mechanistic studies. Sci. Total Environ. 687, 577–589 (2019).

Mujawar, S. Y., Shamim, K., Vaigankar, D. C. & Dubey, S. K. Arsenite biotransformation and bioaccumulation by Klebsiella pneumoniae strain SSSW7 possessing arsenite oxidase (aioA) gene. Biometals 32, 65–76 (2018).

Thomas, P., Mujawar, M. M., Sekhar, A. C. & Upreti, R. Physical impaction injury effects on bacterial cells during spread plating influenced by cell characteristics of the organisms. J. Appl. Microbiol. 116, 911 (2014).

Pandey, N. & Bhatt, R. Arsenic resistance and accumulation by two bacteria isolated from a natural arsenic contaminated site. J Basic Microbiol 55, 1275–1286 (2015).

DIfco, B. B. L. "Muller Hinton Agar." Difco & BBL Manual https://fsl.nmsu.edu/documents/difcobblmanual_2nded_lowres.pdf (2020).

Serrano, H. D. A. et al. Antimicrobial resistance of three common molecularly identified pathogenic bacteria to Allium aqueous extracts. Microb. Pathog. 142, 104028 (2020).

Naveed, M. et al. Identification of bacterial strains and development of anmRNA-based vaccine to combat antibiotic resistance in staphylococcus aureus via in vitro and in silico approaches. Biomedicines 11, 1093 (2023).

Wilson, K. Preparation of genomic DNA from bacteria. Curr. Protoc. Mol. Biol. 56, https://doi.org/10.1002/0471142727.mb0204s56 (2001).

Khatun, N. Applications of normality test in statistical analysis. Open J. Stat. 11, https://doi.org/10.4236/ojs.2021.111006 (2021).

Kenton, Will. "Durbin Watson statistic definition." Corporate Finance & Accounting. https://www.investopedia.com/terms/d/durbin-watson-statistic.asp (2019).

Sebaa, S., Baroudi, D. & Hakem, A. Prevalence of Salmonella Typhi, Staphylococcus aureus and intestinal parasites among male food handlers in Laghouat Province, Algeria. Afr. J. Clin. Exp. Microbiol. 23, 248 (2022).

Singh, R., Singh, S., Parihar, P., Singh, V. P. & Prasad, S. M. Arsenic contamination, consequences and remediation techniques: A review. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 112, 247–270 (2015).

Imran, M., Das, K. R. & Naik, M. M. Co-selection of multi-antibiotic resistance in bacterial pathogens in metal and microplastic contaminated environments: An emerging health threat. Chemosphere 215, 846–857 (2019).

Wu, J. et al. A novel calcium-based magnetic biochar is effective in stabilization of arsenic and cadmium co-contamination in aerobic soils. J. Hazard. Mater. 387, 122010 (2020).

Kao, A. C., Chu, Y. J., Hsu, F. L. & Liao, V. H. C. Removal of arsenic from groundwater by using a native isolated arsenite-oxidizing bacterium. J. Contam. Hydrol. 155, 1–8 (2013).

Atanaskovic, M. et al. Inhibition of Salmonella Enteritidis adhesion and biofilm formation by β-glucosidase B from Microbacterium sp. BG28. Food Biosci. 57, 103543 (2024).

Cui, Y. et al. Identification of acetaminophen degrading microorganisms in mixed microbial communities using 13C-DNA stable isotope probing. Chem. Eng. J. 487, 150656 (2024).

Learman, D. R. et al. Comparative genomics of 16 Microbacterium spp. that tolerate multiple heavy metals and antibiotics. PeerJ 2019, 6258 (2019).

Su, R., Zhang, S., Zhang, X., Wang, S. & Zhang, W. Neglected skin-associated microbial communities: A unique immune defense strategy of Bufo raddei under environmental heavy metal pollution. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30, 22330 (2023).

Perelomov, L. et al. Antibiotic resistance in metal-tolerant microorganisms from treatment facilities. Antibiotics 12, 1678 (2023).

Massaro, M. et al. Cyclodextrin-grafted-hectorite based nanomaterial for antibiotics and metal ions adsorption. Appl. Clay Sci. 250, 107271 (2024).

Nguyen, T. H. T. et al. Efflux pump inhibitors in controlling antibiotic resistance: Outlook under a heavy metal contamination context. Molecules https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28072912 (2023).

Sun, F., Xu, Z. & Fan, L. Response of heavy metal and antibiotic resistance genes and related microorganisms to different heavy metals in activated sludge. J. Environ. Manag. 300, 113754 (2021).

Zhang, M. et al. Co-selection and stability of bacterial antibiotic resistance by arsenic pollution accidents in source water. Environ. Int. 135, 105351 (2020).

Jeon, J. H., Jang, K. M., Lee, J. H., Kang, L. W. & Lee, S. H. Transmission of antibiotic resistance genes through mobile genetic elements in Acinetobacter baumannii and gene-transfer prevention. Sci. Total Environ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.159497 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Consejo Nacional de Humanidades, Ciencia y Tecnología (CONAHCYT) de Mexico for their valuable support, as well as the authorities of our alma mater, Universidad de Guanajuato.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

U.E. Rodriguez, A.H. Serafin Muñoz, A. Alvarez Vargas, and M.C. Cano wrote the main text of the manuscript, prepared all the figures, and carried out the experimental part of the research. G. Cruz Jimenez and N.L. Gutierrez Ortega analyzed the samples by FTIR. U.E. Rodríguez and R. Miranda Aviles analyzed the samples by transmission electron microscopy and scanning electron microscopy. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rodríguez-Castrejón, U.E., Serafín-Muñoz, A.H., Álvarez-Vargas, A. et al. Assessment of arsenite removal efficiency, resistance, and biotransformation by Microbacterium hydroxycarbonoxydans isolated from contaminated sites. Sci Rep 15, 18494 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98622-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98622-8