Abstract

Access to healthcare services is an important aspect in providing health care, but there is little information about the perception level of people who have come to healthcare centers about access to services in Herat, Afghanistan. The aim of this study was to investigate the perception level of people referred to healthcare centers in Herat in 2024. The study was a cross -sectional study and participants (n = 420) included individuals aged 18–65 to Herat healthcare centers. The cluster sampling method was that each of the 31 service centers was considered. Modified Penchansky and Thomas’s (2015) Theory of Access questionnaire was used to collect data from a sample of people referred to medical centers in Herat. The results demonstrated that the perception level of clients significantly varied across different variables such as age, gender, economic conditions, job status, education level, and marital status. The mean scores for the perception level of various variables including accessibility, acceptability, affordability, accommodation, awareness, and availability were reported as 65.86, 30.48, 52.48, 64.05, 73.11, and 63.31, respectively. The results indicated that perception level was the highest for awareness and after it accessibility, and affordability, respectively. Moreover, education level and job status had a statistically significant effect on perception level (P-value < 0.05). This study revealed the importance of considering demographic characteristics when assessing the level of peoples’ perceptions of access to health care services. Improving access to health care services requires a comprehensive understanding of the various factors that influence levels of perception. Addressing these factors can help to increase the quality and effectiveness of providing health services in Herat city.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Access to health centers is essential for people to receive timely and appropriate medical care. Unfortunately, not all societies have equal access to health care centers and lead to inequality in health care results. Factors such as geographical location, socioeconomic status and insurance coverage can affect a person’s ability to access these services1.

Access to health care centers in Asian countries varies greatly depending on the country and the region. In some countries, especially in urban areas, there are equipped hospitals and well -equipped health clinics that are easily accessible to the population2. However, in rural and remote areas, access to health care due to factors such as long distances, lack of transportation and inadequate health care infrastructure can be limited. In countries such as Japan and South Korea, access to health care centers is generally good, with a well -developed health care system and a high proportion of health care professionals to the population3. In contrast, countries such as Afghanistan and Myanmar are struggling with limited access to health care, especially in rural areas where there is a lack of health care facilities and trained staff4.

According to the WHO, in Afghanistan, only 57% of the population has access to basic health care services and the quality of health care services remains worrying5. The Afghanistan Ministry of Public Health has also recognized the importance of improving access to healthcare services6.

The health system in Afghanistan has evolved significantly over time, influenced by cultural, political, and socio-economic factors. Traditionally, the Afghan people relied on herbal medicines and community practices for health care7. Modern health care began to develop in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, but was severely disrupted by conflicts, including the Soviet invasion, civil wars, and the rise of the Taliban, which led to declining health indicators and high rates of maternal and infant mortality8,9. Since 2001, the international community has attempted to rebuild the health care system by building facilities, training professionals, and implementing health programs10. Despite these efforts, ongoing conflict, political instability, economic challenges, and cultural barriers continue to hinder the delivery of health care11. The return of the Taliban in 2021 has raised concerns about access to healthcare and the rights of women and marginalized groups, underscoring the importance of understanding the historical context to navigate current challenges and inform future health policies12,13.

Access to health care centers in Afghanistan and its districts can vary depending on location and security. In urban areas such as Kabul, there are hospitals and clinics that offer a wide range of health care, including emergency care, surgery and specialized medical treatment14,15. However, in rural or remote areas, access to health care can be limited or existing. Many people in these areas may travel long distances to reach the nearest health care center, which can be challenging especially for those who are sick or injured. In addition, continuous conflict and insecurity in Afghanistan can also create obstacles to access to health care. Violence and attacks on health centers and workers have been reported, which makes people seek medical help16,17.

Efforts have been made to expand healthcare facilities and make services more accessible to the population. However, the challenges continue in many areas, including Herat14. There are several medical centers in Herat that provide health care services to the population. However, the level of perception of those who have referred to these medical centers on access to services is unknown18.

The level of perception of people who have referred to medical centers on access to services can vary based on various factors, including a specific medical center, individual experiences with health care and ease of income and services19. The level of perception in Afghanistan varies depending on a variety of factors, including geographical location, financial status and quality of health facilities20. People’s perception level in Herat varies depending on the specific center and the area in which they live. In general, many people believe that access to health care services in Herat is limited due to lack of resources, infrastructure and trained medical professionals21. It is often reported that crowded medical centers are deficient and lacking medication and equipment. This leads to long waiting time, poor quality care and general dissatisfaction with the health care system. However, there are some medical centers in Herat that are understood for better access to services, with shorter waiting time, better quality care and more resources available22.

There have been numerous studies on access to health services in Afghanistan, focusing on various aspects such as the quality of care, accessibility of services and access barriers20,23. However, there is a gap in research that specifically examines the understanding of people referred to medical centers in Herat on access to services. Existing studies are primarily focused on health care providers instead of understanding those looking for health care services.

With regard to the importance of access to health care services for overall well -being and quality of life, it is necessary to examine the understanding of people referred to medical centers in Herat. Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate the perception of people referred to medical centers in Herat on access to health care services.

Methods

Study design

This study followed a cross-sectional design, where data was collected at a single point in time. The study was conducted in medical centers in Herat, Afghanistan, as well as in the surrounding districts in 2024. Participants will be individuals who have been referred to these medical centers for treatment.

Study setting

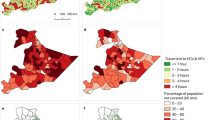

The present study was conducted in various health centers located in urban and rural areas of Herat province. The research included a mix of public and private medical centers. Public centers were mainly government-funded institutions, while private centers provided health care services for a fee. Focusing on both types of facilities provided a comprehensive overview of access issues across different socioeconomic settings. The study included primary, secondary, and tertiary care centers. Primary care centers typically managed general health issues and served as the first point of contact for patients. Secondary care included more specialized medical services that often required referral from primary care providers. Tertiary care included highly specialized care, often provided by larger hospitals equipped with advanced technology and specialized physicians. Of the 31 service centers included in the study, a significant proportion was located in urban areas of Herat city, the provincial capital, which has a greater concentration of medical resources. A significant number of centers were located in rural districts surrounding Herat city, aiming to provide access to healthcare to people in less densely populated areas. This rural-urban distribution allowed for a broader understanding of the access challenges faced by different communities.

Participants

The participants in this study included men and women with an age range of 18 to 65 years referring to the medical center of Herat and its surrounding areas.

Sample size

The sample size for this study was determined using a power analysis based on the population size of individuals referred to medical centers in Herat. A confidence level of 95% and a margin of error of 5% were used to determine the sample size needed for this study. Considering the test power of 90% and the number of independent variables of the model equal to 10, the sample size was obtained 420. The G-Power software was used to calculate the sample size.

Sampling

The sampling method in this study was cluster sampling. Initially, each of the 31 service centers was considered as the class (because the status of each of these centers is different from the others). Then, according to the population covered by each of the centers, they attempted to sample available from clients.

Data collection

Data was collected using the modified Penchansky and Thomas’s (2015) Theory of Access questionnaire. The initial version of the Perception of Access to Health care Services Questionnaire was developed based on the deductive method with a wide range of contents, definitions, and features of the concept of access as well as the perception of access and related questionnaires24. The initial questionnaire was developed according to the five dimensions, which were introduced in Penchansky and Thomas’ model of access (1981), and the 6 dimension, which was introduced in Saurman’s (2015) study24,25. The questionnaire identifies 5 dimensions that influence an individual’s ability to access health services. This theory has been widely used in health care research to understand and improve access to care for people from diverse backgrounds. This questionnaire includes 30 items that record various aspects of access to health care services and allows the assessment of the level of access and possible barriers of people. This questionnaire is divided into five sections of availability, accessibility, accommodation, affordability, and acceptability. The participants were asked to rate their agreement with statements related to each dimension on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Furthermore, the questionnaire covered demographic information (age, gender, marital situation, economic status, job situation, and education level), the frequency of use of medical service centers, and perceived challenges in access.

The key indicators of economic status were categorizing into four groups of good, moderate, weak and poor. Good included the individuals with high incomes, stable jobs, good living conditions, and access to financial services and assets. Moderate contained those with reasonable incomes and jobs but facing challenges related to living conditions and service access. Poor was the individuals with low incomes or unemployment, limited access to basic services, and poor living conditions. Very poor was the individuals who are unemployed or severely underemployed, with minimal access to essential services and basic living conditions.

The questionnaire was administered to participants either in person or electronically, depending on their preference. The data collection was also performed through interviews to ensure comprehension and accuracy of the questions.

Validation of the tool

Validity

The content of the questionnaire was analyzed in both quantitative and qualitative ways. Ten members of the expert panel were selected using the accessible method for qualitative content validity assessment. The opinion presented by the panel of experts in the field of access to health, research and psychometric services was obtained in terms of grammar, use of appropriate items and expressions, appropriate position of questionnaire items and scoring method. Also, a questionnaire was sent to 15 experts for quantitative content validity analysis, and content validity ratio (CVR) and content validity index (CVI) were determined. In order to calculate CVR and after explaining the objectives of the questionnaire and providing the operational definitions related to the content of the questions, the experts were asked to rate each question based on a 3-point Likert scale, “The item is necessary”, “The item is useful but unnecessary”, and “The item is unnecessary”. Then, the content validity ratio (CVR) was calculated using the formula.1 In examining the Content Validity Index (CVI), the experts were asked to determine the degree of relatedness based on a four-point scale: (1) not relevant, (2) somewhat relevant, (3) quite relevant, (4) highly relevant. The number of experts who chose options 3 and 4 was divided by the total number of experts afterward. The CVR and CVI of the considered questionnaire were confirmed by a panel of specialists and participants. The CVR and CVI were > 0.78 and > 0.79 respectively.

Reliability

Reliability refers to the degree to which individuals maintain their position on a sample of repeated dimensions. To assess it, the Intraclass Correlation Index (ICC) value was measured using the two-week test-retest approach for a group of 10 people from the Southern Health Centers. In this study, the minimum ICC rate was considered 0.7525. Internal consistency indicates whether the items in an instrument are conceptually compatible or not. Internal consistency was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha. The internal consistency of the questionnaire was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha, which showed a high level of agreement among patients referred to health centers. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was larger than 0.7, although it was 0.86 for the entire questionnaire. Moreover, the ICC value obtained from the questionnaire was 0.94 (CI95%: 0.78, 0.98), which was calculated using the two-way mixed absolute agreement method.

Statistical analysis

Data collected through the questionnaire was analyzed using statistical methods, including descriptive statistics to summarize the data and inferential statistics to test hypotheses related to access to medical services in Herat. The Kolmogorov-Smironov test was used to check the normality of data distribution. Moreover, Chi-square test and independent t-tests, Mann-Whitney test, and two-way ANOVA were used to examine relationships between variables and determine factors that influence access to services. Besides, for determining the factors associated with the perception score the multiple linear regression models was used. The data analysis was then performed using SPSS version 26 software and a significance level of 0.05 was considered.

Results

The study included 440 participants, with a demographic breakdown showing 33.6% under 30 years, 35.2% aged 30–45, 21.6% aged 45–60, and 9.5% over 60. Of the participants, 62.7% were women and 37.0% were men. Marital status revealed 57.3% were married, 23.9% single, and 18.9% divorced. In terms of economic conditions, 40.5% reported good, 53.9% moderate, 33.4% weak, and 8% poor economic conditions (Table 1).

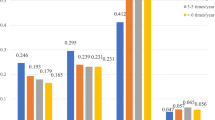

The results also presented data on job status and education levels among a group of individuals. Specifically, 19.3% had specific jobs, 26.8% had free jobs, and 52.7% were unemployed. Regarding education, 17% were illiterate, 15.5% had basic literacy, 35.2% had primary education, 22% had diplomas, and 10.2% held university degrees. Additionally, it provides average scores for various factors related to understanding: accessibility (65.86), acceptability (30.48), affordability (52.48), accommodation (64.05), awareness (73.11), and availability (63.31) (Table 2).

The average scores for various variables related to different economic statuses (good, moderate, poor, very poor) were also provided. For accessibility, the scores were 64.0, 67.51, 64.22, and 63.05. Acceptability scores were 31.45, 31.02, 29.65, and 29.60. Affordability scores are 54.33, 53.10, 50.97, and 52.53. Moreover, accommodation scores were 69.62, 65.76, 60.82, and 62.35. Awareness scores were 78.60, 74.15, 71.94, and 67.52. Availability scores were also 64.0, 67.51, 64.22, and 63.04 (Table 2).

The study found statistically significant differences in the average scores of perception regarding economic conditions across various variables, including accessibility, acceptability, accommodation, awareness, and availability. Notably, the scores for acceptability, accommodation, and awareness were higher than those for other variables, indicating that clients had a more favorable perception of treatment centers in relation to these three aspects. The P-values for these findings were 0.040, 0.009, 0.0001, 0.0001, and 0.040 (Table 3).

In addition, the various perception level scores related to education levels across five variables of accessibility, acceptability, affordability, accommodation, and awareness were obtained. The scores for accessibility ranged from 62 to 68, while acceptability ranged 30.38 to 30.89. Affordability scores were lower, averaging between 50.65 and 56.44, and accommodation scores ranged from 60.90 to 67.72. Awareness scores were the highest, increasing from 68.85 to 78.09. Notably, the perception levels for affordability, accommodation, and awareness demonstrated statistically significant differences, with P-values of 0.0001, 0.029, and 0.0001, respectively (Table 4).

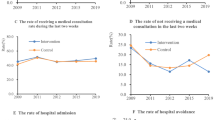

The study reported average scores for various variables (accessibility, acceptability, affordability, accommodation, awareness, and availability) across different job positions (employed, freelance, unemployed) and marital statuses (married, single, divorced). For job positions, accessibility scores were 72.39, 63.50, and 64.70, while acceptability scores were 32.05, 30.35, and 29.94. Affordability scores were relatively similar across job levels, averaging around 51.68 to 52.67. Accommodation scores were 67.59, 65.55, and 61.95, and awareness scores were 74.37 and 70.96. All differences in average scores for the variables were statistically significant, except for affordability, with p-values below 0.001 for most variables. Regarding marital status, accessibility scores were 66.08, 65.57, and 65.54 for married, single, and divorced individuals, respectively, while acceptability scores were lower. The affordability scores varied more widely, and awareness scores were 73.09, 74.04, and 72.04 (Table 5).

The study found that the average scores for the availability variable were 66.08, 65.83, and 63.20 (Table 6). A statistically significant difference based on marital status was noted only for the accommodation variable (P = 0.043). Gender differences in perception levels showed that women’s average scores for accessibility, acceptability, affordability, accommodation, awareness, and availability were 65.76, 30.18, 52.12, 62.37, 72.27, and 65.97, respectively, while men’s scores were 35.97, 30.98, 53.08, 66.97, 74.55, and 65.97. Statistically significant differences were found in awareness (P = 0.0001) and availability (P = 0.033), with awareness showing a more pronounced difference (Table 7).

Discussion

This study included 440 patients from medical centers in Herat, Afghanistan. The results showed that the demographic characteristics of the participants are different in terms of age, gender, marital status, economic conditions, and employment status and education level. In addition, overall mean scores were obtained for the level of understanding of various variables related to accessibility, acceptability, affordability, accommodation, awareness, and availability.

The participants were mostly between 30 and 45 years old and were mostly women and married people. The participants had different economic conditions, job status and education level. The average scores of the studied variables of accessibility, acceptability, affordability, accommodation, awareness and availability were obtained as 65.86, 30.48, 52.48, 64.05, 73.11 and 63.31, respectively. The perception levels were different based on economic conditions, education level, employment status and marital status.

This study found a statistically significant difference in perception levels for all variables except affordability based on economic conditions, for affordability, residence and awareness based on education level, for all variables except affordability based on job status and for accommodation based on Marital status showed. The difference in perception levels was more significant for the variables of acceptability, compatibility and awareness than other variables. Moreover, the results demonstrated that gender had an effect on perception levels, with women scoring higher on awareness and men scoring higher on availability.

The comparison of the mean scores of perception level in terms of economic conditions among the studied variables showed that the difference in scores for the variables of access, acceptability, accommodation, awareness and availability is statistically significant. The scores of variables of acceptability, accommodation and awareness were higher than other variables, which show that the level of perception of clients towards medical centers is higher in relation to these three variables.

Additionally, the comparison of the mean scores of the level of perception in terms of education level showed that the scores of variables of affordability, accommodation and awareness are statistically significant compared to other groups. Similar results were found for occupational status, where the difference in scores was statistically significant for all variables except for the affordability variable. Also, the results based on marital status showed that the difference in mean scores is significant only for the residence variable.

The analysis based on gender showed that the mean scores for the variables of awareness and availability have statistically significant differences and this difference is greater in the variable of awareness. This study indicated the importance of considering different demographic characteristics when assessing the level of people’s perception of medical services, as various factors can influence their perceptions of access, acceptability, affordability, and accommodation affect the awareness and availability of services.

There are limited studies that specifically focus on the level of perception of medical center visitors regarding access to services in Afghanistan. However, a study by Mensah et al. in Ghana found that accessibility to healthcare services was positively associated with patient satisfaction and perceived quality of care26. Similarly, a study by Yadav et al. in Nepal found that improving access to healthcare services led to increased utilization and satisfaction among patients27. In contrast, a study by Nishtar et al. in Pakistan reported the barriers to access to healthcare services, including geographical disparities and financial constraints28. Another study by Mburu et al. in Kenya indicated that long waiting times and inadequate infrastructure were significant challenges to accessing healthcare services in rural areas29.

Comparing the results of the present study with other studies on the perception level of people regarding access to medical services, it can be seen that the level of perception in Herat is relatively high. Specifically, the average scores for accessibility, acceptability, accommodation, awareness, and availability were higher in this study compared to previous studies. This indicates that the people in Herat City have a better understanding and perception of the services provided in medical centers.

Access to health care services is a critical component of health systems and directly affects the health outcomes of individuals and communities. In Afghanistan, a country that has been involved in conflict and instability for years, access to quality health services is of particular importance17,30. In the city of Herat, which is the third largest city in Afghanistan and the largest urban center in the western region of the country, access to health services is a significant concern for its residents31. The level of perception of medical center visitors regarding access to services in Afghanistan can be very different depending on a range of factors including geographic location, socio-economic status, education level and previous experiences with the health care system32. In urban areas, where medical facilities are more common and better equipped, people may have a relatively positive perception of access to services. They may feel that they can easily access medical care when needed and receive timely and quality treatment33. On the other hand, in rural and remote areas where health care facilities are limited and resources are scarce, people may have a more negative perception of access to services34. They may have to travel long distances to reach a medical facility, face long wait times, and receive substandard care due to a lack of medical equipment and qualified health care providers35.

The perception of access to services in Afghanistan’s medical centers is likely to be influenced by the many challenges facing the country’s healthcare system, including a lack of infrastructure, shortages of medical staff and supplies, and ongoing security concerns11. Efforts to improve access to healthcare services, such as increasing funding for healthcare, training more healthcare workers, and expanding healthcare facilities to underserved areas, will be crucial in changing perceptions and ultimately improving the health outcomes of the Afghan population20.

Study limitations

While this study provides valuable insights into the perceptions of individuals who accessed healthcare centers in Herat city, it is important to note that the findings may not be generalizable to the entire population. By focusing on individuals who actively sought care, the study may overestimate perceptions of access, as those with lower awareness of available services or significant barriers to access (e.g., economic constraints, geographic isolation, or cultural factors) were likely underrepresented. This limitation highlights the need for caution when interpreting the results, as they reflect the experiences of a specific subset of the population rather than the broader community. Future studies should aim to include individuals who do not utilize formal healthcare services, such as those relying on traditional medicine or facing systemic barriers to access. This would provide a more comprehensive understanding of healthcare access perceptions and inform targeted interventions to reach underserved populations.

In general, the perception of medical center visitors regarding access to services in Herat and its districts may be influenced by various factors such as geographic location, infrastructure, and financial cons.

Also, while this study examined the independent effects of demographic characteristics such as gender, economic status, and education on perceptions of healthcare access, it did not explore the intersectional interactions between these factors. Intersectional perspectives, which consider how multiple social identities (e.g., gender, economic status, and education) combine to shape experiences, could provide deeper insights into the barriers and facilitators of healthcare access. For example, the combined effects of being a woman with low economic status and limited education may create unique challenges that are not fully captured by analyzing these factors in isolation.

Future studies

To build on these findings, future research should focus on the following areas:

-

Adopting an intersectional approach to better understand how overlapping demographic characteristics influence perceptions of healthcare access and to inform more targeted and inclusive interventions.

-

Conducting longitudinal studies to track changes in perceptions over time and assess the impact of policy interventions.

-

Using qualitative methods to explore the cultural and social barriers underlying disparities in access perceptions.

-

Evaluating the effectiveness of targeted interventions, such as subsidized healthcare programs and gender-sensitive services, in improving access.

-

Comparing perceptions across different regions of Afghanistan to identify context-specific challenges.

-

Investigating the role of healthcare provider behavior and patient-provider interactions in shaping access perceptions.

-

Exploring the potential of telemedicine and digital health solutions to bridge gaps in access for underserved populations.

By addressing these research gaps, future studies can provide a more comprehensive understanding of healthcare access disparities and inform evidence-based strategies to improve health outcomes in Herat city and beyond.

Conclusions

This study revealed that the level of perception of individuals accessing health centers in Herat city, Afghanistan, varied significantly based on demographic characteristics such as age, gender, marital status, economic status, employment status, and education level. The average overall scores for variables including access, acceptability, affordability, accommodation, awareness, and availability were calculated, with awareness receiving the highest average score. The findings demonstrated statistically significant differences in perception levels based on economic conditions for variables such as accessibility, acceptability, accommodation, awareness, and availability. Additionally, education level and employment status significantly influenced perception levels across these variables. Marital status and gender also played a role in shaping perceptions.

These findings highlight the critical role of demographic characteristics in influencing perceptions of access to healthcare services in Herat city. To address these disparities, the following concrete actions are recommended:

Targeted awareness campaigns: Develop and implement educational programs tailored to different demographic groups, particularly those with lower education levels or economic status, to improve awareness of available healthcare services.

Subsidized healthcare programs: Introduce subsidized or free healthcare services for low-income populations to improve affordability and accessibility.

Gender-sensitive services: Design healthcare services that address the specific needs of women and men, considering cultural and social norms in the region.

Community outreach programs: Establish mobile clinics or community health workers to reach underserved populations, particularly in rural or economically disadvantaged areas.

Employment-based health initiatives: Collaborate with employers to provide health insurance or healthcare access for workers, especially in informal sectors.

Policy reforms: Advocate for policy changes that prioritize equitable access to healthcare, ensuring that interventions are inclusive and address the needs of vulnerable populations.

By implementing these evidence-based strategies, policymakers and healthcare providers can work toward reducing disparities and improving access to healthcare services in Herat city, ultimately enhancing the overall health outcomes of the population.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study may be available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Blazer, D. G. et al. Hearing health care services: Improving access and quality. Hearing Health Care for Adults: Priorities for Improving Access and Affordability (2016).

UN ESCAP. The impact of ageing on accessibility, affordability and availability of healthcare services in Asia and the Pacific (2022).

Iglehart, J. K. Japan’s medical care system. In Health Care Systems and their Patients 147–168 (Routledge, 2019).

Miller, N. P. et al. Community health workers in humanitarian settings: Scoping review. J. Glob. Health 10(2) (2020).

Kovess-Masfety, V. et al. A National survey on depressive and anxiety disorders in Afghanistan: A highly traumatized population. BMC Psychiatry 21(1), 314 (2021).

Lange, I. L. et al. The development of Afghanistan’s integrated package of essential health services: Evidence, expertise and ethics in a priority setting process. Soc. Sci. Med. 305, 115010 (2022).

Kazmi, S. B. et al. Changing dynamics of terrorism in Afghanistan and its impact on Socio-Political and economic milieu: A critical analysis. Dialogue Social Sci. Rev. DSSR 2(5), 572–584 (2024).

Khan, I. G. Afghanistan: Human cost of armed conflict since the Soviet invasion. PERCEPTIONS: J. Int. Affairs 17(4), 209–224 (2012).

Tawfiq, E. et al. Quality of antenatal care services in Afghanistan: Findings from the National survey 2022–2023. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 25(1), 71 (2025).

Stanikzai, M. H. et al. Contents of antenatal care services in Afghanistan: Findings from the National health survey 2018. BMC Public Health 23(1), 2469 (2023).

Frost, A. et al. An assessment of the barriers to accessing the basic package of health services (BPHS) in Afghanistan: Was the BPHS a success? Glob. Health 12(1), 1–11 (2016).

Anderson, A. The human right to health and medicine: What does this look like for Taliban-Controlled Afghanistan? Immigration Hum. Rights Law Rev. 6(1), 3 (2025).

Tawfiq, E. et al. Factors influencing early postnatal care use among postpartum women in Afghanistan. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 31300 (2024).

Newbrander, W. et al. Afghanistan’s basic package of health services: Its development and effects on rebuilding the health system. Glob. Public Health 9(sup1), S6–S28 (2014).

Newbrander, W. et al. Barriers to appropriate care for mothers and infants during the perinatal period in rural Afghanistan: A qualitative assessment. Glob. Public Health 9(sup1), S93–S109 (2014).

Nic Carthaigh, N. et al. Patients struggle to access effective health care due to ongoing violence, distance, costs and health service performance in Afghanistan. Int. Health 7(3), 169–175 (2015).

Mirzazada, S. et al. Impact of conflict on maternal and child health service delivery: A country case study of Afghanistan. Confl. Health 14, 1–13 (2020).

Rouhanizadeh, B. & Kermanshachi, S. Barriers to an effective post-recovery process: A comparative analysis of the public’s and experts’ perspectives. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 57, 102181 (2021).

Levesque, J. F., Harris, M. F. & Russell, G. Patient-centred access to health care: Conceptualising access at the interface of health systems and populations. Int. J. Equity Health 12, 1–9 (2013).

Rahmani, Z. & Brekke, M. Antenatal and obstetric care in Afghanistan–a qualitative study among health care receivers and health care providers. BMC Health Serv. Res. 13(1), 1–9 (2013).

Hanif, A. et al. Participation in practice in community-driven development projects in Afghanistan: A case study of Herat City. Global Social Welfare 1–13 (2023).

Kasahara, N. Assessing the Availability, Service Quality, and Price of Essential Medicines in Private Pharmacies in Afghanistan (2015).

Mumtaz, S., Bahk, J. & Khang, Y. H. Current status and determinants of maternal healthcare utilization in Afghanistan: Analysis from Afghanistan Demographic and Health Survey 2015. PloS One 14(6), e0217827 (2019).

Penchansky, R. & Thomas, J. W. The concept of access: Definition and relationship to consumer satisfaction. Med. Care 19(2), 127–140 (1981).

Saurman, E. Improving access: Modifying Penchansky and Thomas’s theory of access. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 21(1), 36–39 (2016).

Mensah, J. K. et al. The policy and practice of local economic development In Ghana. In Urban Forum (Springer, 2019).

Yadav, A. K. & Jena, P. K. Explaining changing patterns and inequalities in maternal healthcare services utilization in India. J. Public Affairs 22(3), e2570 (2022).

Nishtar, S. et al. Protecting the poor against health impoverishment in Pakistan: Proof of concept of the potential within innovative web and mobile phone technologies. World Health Rep. 55 (2010).

Mburu, S. & Oboko, R. A model for predicting utilization of mHealth interventions in low-resource settings: Case of maternal and newborn care in Kenya. BMC Med. Inf. Decis. Mak. 18, 1–16 (2018).

Sacks, E. et al. Beyond the Building blocks: Integrating community roles into health systems frameworks to achieve health for all. BMJ Glob. Health 3(Suppl 3), e001384 (2019).

Hirose, A. et al. Difficulties leaving home: A cross-sectional study of delays in seeking emergency obstetric care in Herat, Afghanistan. Soc. Sci. Med. 73(7), 1003–1013 (2011).

Safi, F. A. & Doneys, P. Exploring the influence of family level and socio-demographic factors on women’s decision-making ability over access to reproductive health care services in Balkh Province, Afghanistan. Health Care Women Int. 41(7), 833–852 (2020).

Arnold, R. E. Afghan Women and the Culture of Care in a Kabul Maternity Hospital (Bournemouth University, 2015).

Essar, M. Y., Siddiqui, A. & Head, M. G. Infectious diseases in Afghanistan: Strategies for health system improvement. Health Sci. Rep. 6(12), e1775 (2023).

Lamberti-Castronuovo, A. et al. Exploring barriers to access to care following the 2021 socio-political changes in Afghanistan: A qualitative study. Confl. Health 18(1), 36 (2024).

Funding

This study has been approved and funded by Mashhad University of Medical Sciences.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.M. and S.S.T. designed the study. J.M. and L.S. prepared the questionnaire. L.S. gathered data. V.Gh. analyzed data. J.M. and L.S. wrote the main manuscript text. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This research has been approved by Mashhad University of Medical Sciences (MUMS), Iran. The project ethics code is IR.MUMS.FHMPM.REC.1402.157. Participants were free to fill out the questionnaire and the informed consent for participation in the study was verbally acquired and each of the participants was assured that their responses would be kept confidential. The ethics committee of MUMS was responsible for issuing the code of ethics and checking the compliance of all ethical considerations in the research, including obtaining informed consent to participate in the study and final approval of the study process. We confirm that all methods were performed according to the relevant guidelines and regulations in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Satarzadeh, L., Tabatabaee, S.S., Ghavami, V. et al. Understanding patient perceptions of access to healthcare centers in one of the major cities of Afghanistan. Sci Rep 15, 13500 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98678-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98678-6