Abstract

Symbiotic bacteria play a crucial role in the survival, development, and adaptation of aphids to environmental conditions. Buchnera aphidicola (Enterobacterales: Erwiniaceae), the obligate endosymbiont of aphids, is essential for their fitness, while facultative symbionts may provide additional ecological advantages under specific conditions. A comprehensive understanding of how these symbiotic relationships respond to different climatic environments is essential for assessing aphid adaptability and potential implications for biological control. The present study investigates the vital interactions between the obligate bacterial endosymbiont, Buchnera aphidicola, and four facultative bacterial endosymbionts (Arsenophonus sp., Hamiltonella defensa, Serratia symbiotica, and Regiella insecticola), in black cowpea aphid (BCA), in the context of different climate conditions. The BCA specimens were obtained from the leaves of the host plant, alfalfa, cultivated in three distinct climates: cold semi-arid, hot desert, and humid subtropical climates. The findings, as anticipated, indicated a pervasive prevalence of B. aphidicola in BCAs infesting alfalfa crops across all three climate types. In contrast, the BCAs of each climate type exhibited a distinct array of facultative symbionts. The highest number of facultative endosymbionts was exhibited by BCAs from the humid subtropical climate, followed by BCAs from the cold semi-arid climate, whereas none of them were detected in BCAs from the hot desert climate. Rigiella insecticola was not detected molecularly in any of the BCAs from the three climates. Following the eradication of the obligate symbiont Buchnera aphidicola by the antibiotic rifampicin in BCAs, the effects on three categories of parameters were assessed, including life cycle stages, reproductive traits, and external morphological characteristics of adults. The most significant adverse effects were observed in BCAs inhabiting hot desert followed by those inhabiting cold semi-arid climate; detrimental effects in BCAs of the humid subtropical climate were considerably less pronounced. The observed discrepancies in the parameters of BCAs from the humid subtropical climate can be attributed to the presence of a greater number of facultative symbionts, especially the presence of Serratia symbiotica (Enterobacterales: Yersiniaceae). Following the eradication of B. aphidicola, this facultative symbiont continues to complement the functions of B. aphidicola in the host’s survival. Conversely, the low presence of facultative symbionts in cold semi-arid climate or even their absence in hot desert climate exacerbates the negative effects of obligate symbiont eradication. These findings highlight the crucial role of symbionts in aphid biology across a spectrum of climatic conditions, and suggest that shifts in symbiotic relationships may modulate aphid fitness, which could have implications for biological control programs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

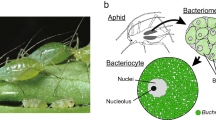

The majority of insects and other eukaryotic organisms are hosts to symbiotic bacteria1. These bacteria reside within the host organism and establish mutualistic relationships by providing essential nutrients and facilitating digestion. Obligate symbionts are indispensable for host survival and are transmitted from mother to offspring. The obligate endosymbiont, Buchnera aphidicola (Enterobacterales: Erwiniaceae), is a member of the γ-proteobacteria2. This obligate endosymbiont bacterium is capable of providing essential nutrients, vitamins, and other compounds that its hosts are unable to produce themselves, or even facilitating improvements in food intake3. In contrast, facultative γ-proteobacterial or facultative symbionts are not indispensable for every host and can exert a range of effects, including positive, negative, or neutral4. In general, they are not essential for the development and reproduction of their host5. Facultative symbionts facilitate the transfer of essential host ecological traits through horizontal gene transfer (HGT), including protection against parasitism6, heat tolerance7,8, and resistance to fungal pathogens9,10. In addition, they have been observed to manipulate reproduction11, transform body coloration12, and propagate asexual lineages13.

Aphids are frequently infected by one or more facultative symbiont species, with a low infection rate in natural populations14. The black cowpea aphid is host to several species of symbiotic bacteria, which contribute to its status as an extraordinary aphid15. The functions of facultative symbionts remain incompletely understood. The impact of these symbionts on their hosts’ performance can be observed in their capacity to alter roles in response to varying conditions16. The endosymbiotic relationship between symbiotic bacteria such as Hamiltonella sp., Arsenophonus sp., and Regiella insecticola and aphids provides an illustrative example of the intricate web of interactions that exist within the natural world. Several studies have indicated that these bacteria may function as a defensive mechanism, protecting their aphid hosts against natural enemies such as parasitoid wasps and fungal pathogens17,18,19,20.

In certain aphid species, B. aphidicola is unable to synthesize essential amino acids that are necessary for survival, thereby constraining its metabolic capabilities. To compensate for this deficiency, aphids also rely on facultative symbionts, particularly Serratia symbiotica, which helps to complement the functions of Buchnera. Collectively, B. aphidicola and S. symbiotica create a more resilient and adaptable symbiotic system that allows the host aphids to thrive in various environments21.

On the other hand, climate change, particularly global warming, poses significant challenges to these aphids and their symbiont interactions. Elevated temperatures can disrupt the delicate balance of these relationships, leading to potential declines in aphid fitness and survival. Heat stress has been shown to negatively impact the density and functionality of essential symbionts22. In aphid populations, heat stress can also lead to the loss of facultative symbionts like H. defensa, which provides protection against parasitoids. This loss renders aphids more susceptible to natural enemies under elevated temperatures23.

Alfalfa (Medicago sativa L., Fabales: Fabaceae) is a perennial legume that has been cultivated for over 4,000 years. It is widely grown as a forage crop for pasture, hay, silage, and green chop, and it is renowned for its high nutritional value. Alfalfa plays a pivotal role in livestock feeding programs24. Alfalfa fields provide habitat for a variety of arthropods, some of which are innocuous, while others have the capacity to inflict substantial economic losses25.

The black cowpea aphid (BCA) — Aphis craccivora Koch, Hemiptera: Aphididae — is a highly destructive and globally widespread pest that causes significant damage to a wide range of crops and ornamental plants26. It infests a variety of plants, including alfalfa and flowering ornamentals. A number of studies have identified the obligate symbiont, B. aphidicola, as well as several genera of facultative symbionts in this particular aphid species15. Nevertheless, the role of facultative symbionts still remains poorly understood. The results of insect-symbiont interactions may have implications for the efficacy of biological control programs and the performance of insect hosts. Recent studies have shown that aphid fitness can be affected by infection with various facultative symbionts14 and it is plausible that these infections are not inherently beneficial to their hosts. A comprehensive understanding of the impact of climate change on the symbiotic relationship between aphids and their associated bacteria is imperative for the accurate prediction of future aphid population trends and the development of effective pest managements strategies. The use of antibiotics that selectively target these critical bacteria in aphids presents a safer and more precise alternative to broad-spectrum chemical pesticides. As global temperatures continue to rise, it is of paramount importance to thoroughly examine the intricate interactions between aphids and their symbionts to mitigate potential adverse effects on agriculture and ecosystems.

To date, no previous molecular detection has revealed the presence of B. aphicola in the populations of BCAs across alfalfa sampling stations in the northwest, northeast, and northwest regions of Iran. The present study evaluated the status of obligate and facultative infections in BCAs feeding on alfalfa fields. Additionally, the objective was to ascertain whether the fitness and biological parameters of BCA are influenced by facultative symbionts in the presence and absence of its obligate symbiont, and whether this influence varies in different climate types.

Results

Prevalence of obligate and facultative bacterial symbionts in BCAs

As expected, the obligate symbiont B. aphidicola was confirmed in the first-instar nymphs of BCAs from all three distinct climate types. In contrast, the presence of the three facultative symbionts demonstrated variability across different climatic conditions. Thus, in the humid subtropical (HS) climate, three facultative symbionts were identified: Arsenophonus sp., H. defensa, and S. symbiotica. In the cold semi-arid (CS) climate, only one facultative symbiont, Arsenophonus sp., was detected. Finally, no symbionts were detected molecularly in the hot desert (HD) climate. It is noteworthy that the symbiont Rigiella insecticola was not recorded in any of the three climates under study.

Effects of Buchnera-reduced (BR) infection on the life cycle stages of BCAs

BCAs of a cold semi-arid (CS) climate (Fig. 1A–D)

Effects of Buchnera-reduced (BR) infection on the duration (in days) of the life cycles stages in black cowpea aphids (BCAs). Specimens of BCA were collected from alfalfa crops cultivated under (A–D) cold semi-arid (CS) climate, (E–H) humid subtropical (HS) climate, and (I–L) hot desert (HD) climate. The flag levels of significance (NS, **, and ***) indicate significant differences (t-test, ** P < 0.05).

The reduction of the symbiotic bacterium, B. aphidicola, affected the duration of different stages of BCAs obtained from a CS climate. The duration of the lifespan of nymphal stage 1 (t = 6.99, df = 78, P < 0.001), nymphal stage 2 (t = 3.568, df = 78, P = 0.001), and total nymphal period (t = -5.815, df = 78, P < 0.001) showed a significant increase, meaning that these stages were longer in duration than those of the control. Conversely, both the adult lifespan (t = 23.724, df = 78, P < 0.001) and the total lifespan (t = -6.952, df = 78, P < 0.001), showed a significant decrease, indicating that the duration of these stages was reduced in BCAs under Buchnera-reduced (BR) infection compared with to BCAs naturally infected with Buchnera. However, no significant differences were observed for either nymphal stage 3 (t = -1.676, df = 78, P = 0.98) or nymphal stage 4 (t = -1.641, df = 78, P = 0.181).

BCAs of a humid subtropical (HS) climate (Fig. 1E–H)

The reduction of the symbiotic bacterium, B. aphidicola, did not result in a discernible effect on the duration of the different stages of the life cycle of BCAs obtained in a HS climate. No statistically significant differences were observed in any of the life cycle parameters under investigation: nymphal stage 1 (t = 2.519, df = 78, P = 0.14), nymphal stage 2 (t = 0.00, df = 78, P = 1), nymphal stage 3 (t = 0.194, df = 78, P = 0.847), nymphal stage 4 (t = -3.161, df = 78, P = 0.719), total nymphal period (t = 0.793, df = 78, P = 0.430), adult lifespan (t = 0.169, df = 78, P = 0.491), and total lifespan (t = 0.90, df = 78, P = 0.929).

BCAs of a hot desert (HD) climate (Fig. 1I–L)

The reduction of the symbiotic bacterium, B. aphidicola, resulted in a notable prolongation of the duration of the majority of the lifecycle stages of BCAs obtained in a HD climate. A statistically significant difference was observed in the duration of nymphal stage 1 (t = 10.002, df = 78, P < 0.001), nymphal stage 2 (t = 13.193, df = 78, P < 0.001), nymphal stage 3 (t = 3.250, df = 78, P = 0.002), nymphal stage 4 (t = 15.947, df = 78, P < 0.001), total nymphal period (t = 15.819, df = 78, P < 0.001), and total lifespan (t = 3.472, df = 78, P = 0.001). Notably, the only parameter to demonstrate a statistically significant decrease in duration was that of the adult lifespan (t = -11.257, df = 78, P < 0.001).

In summary, BCAs from cold semi-arid and hot desert climates exhibited a tendency to spend more time in the nymphal stage. However, in the cold semi-arid climate, the delay was observed to be limited to the first two nymphal instars, while in the hot desert, it was evident in all nymphal instars. The adult stage was found to be shortened in BCAs from both climates. The duration of the life cycle was shortened by BCAS in the cold semi-arid climate, but lengthened in the hot desert climate. In the humid subtropical climate, symbiont eradication had no effect on any of the evaluated life cycle parameters.

Effects of Buchnera-reduced (BR) infection on reproductive parameters of BCAs

As for BCAs of cold semi-arid (CS) climate, the reduced infection of the symbiotic bacterium, B. aphidicola, led to a significant extension in the duration of the pre-nymph (t = -6.33, df = 78, P < 0.001), the post-nymphing (t = 42.197, df = 78, P < 0.001), and the first nymphal age (t = -6.676, df = 78, P < 0.001) (Fig. 2A, C, D). Conversely, the remaining reproductive parameters exhibited an inverse pattern. The reduction of the obligate symbiotic bacterium resulted in a significant decrease in the duration of the nymphing (t = 82.986, df = 78, P < 0.001, Fig. 2B), the daily fertility (t = 4.724, df = 78, P < 0.001; Fig. 3A), and the rate of nymphal production (t = -17.361, df = 78, P < 0.001; Fig, 3B).

Effects of Buchnera-reduced (BR) infection on the duration (in days) of reproductive parameters in black cowpea aphids. Specimens of BCA were collected from alfalfa crops cultivated under (A–D) cold semi-arid (CS) climate, (E–H) humid subtropical (HS) climate, and (I–L) hot desert (HD) climate. The flag levels of significance (NS, **, and ***) indicate significant differences (t-test, NS P > 0.05; *** P < 0.05).

Effects of Buchnera-reduced (BR) infection on daily fertility and nymph production of black cowpea aphids (BCAs). Specimens of BCA were collected from alfalfa crops cultivated under (A–B) cold semi-arid (CS) climate, (C–D) humid subtropical (HS) climate, and (E–F) hot desert (HD) climate. The flag levels of significance (NS, **, and ***) indicate significant differences (t-test, NS P > 0.05; *** P < 0.001).

As for BCAs of humid subtropical (HS) climate, the impact of the reduced infection of the symbiotic bacterium, B. aphidicola on the duration of the most of the reproductive parameters was not significant. This was evidenced by the absence of a statically significant difference in the pre-nymphing (t = -1.778, df = 78, P = 0.079) (Fig. 2E), the nymphing (t = 0.853, df = 78, P = 0.396) (Fig. 2F)., the first nymphal age (t = -0.704, df = 78, P = 0.484) (Fig. 2H)., daily fertility (t = -2.527, df = 78, P = 0.677; Fig. 3C), and the nymph production (t = -17.361, df = 78, P = 0.14; Fig, 3D). Notably, the period of post-nymphing was the only reproductive parameter that was zero for both CG and BR treatments (Fig. 2G).

As for BCAs of hot desert (HD) climate, the reduced infection of the symbiotic bacterium, B. aphidicola, shown to exert a substantial eleterious effect on all six reproductive parameters measured: the pre-nymph (t = -14.559, df = 78, P < 0.001); the nymphing (t = -21.952, df = 78, P < 0.001); the post-nymphing (t = -2.479, df = 78, P = 0.015), the first nymphal age (t = -44.620, df = 78, P < 0.001) (Fig. 2I–L); daily fertility (t = -35.906, df = 78, P < 0.001; Fig. 3E), and the amount of nymph production (t = -17.595, df = 78, P < 0.001; Fig. 3D).

In summary, BCAs from the humid subtropical climate demonstrated resilience to the eradication of B. aphidicola. Notably, the flat horizontal lines in Fig. 3G indicate that all data points are identical, with no variation observed within or between the BR and CG treatments. Conversely, BCAs from hot desert climates exerted a deleterious effect on all reproductive parameters. BCAs from the cold semi-arid climate exhibited a divergent effect, characterized by a decline in both the number of offspring produced during nymphing (nymph production), and the number of offspring produced by the females each day (daily fertility). In contrast, the duration of time spent by nymphs in the developmental phase before aphids reach adulthood and begin producing nymph (pre-nymphing) and the phase after aphids produce their final nymphs, during which they lose reproductive ability until death (post-nymphing), as well as the age at which an aphid produces its first nymph (first nymphing age), exhibited an increase in duration.

Effects of Buchnera-reduced (BR) infection on BCAs external morphological characteristics

The effects of eradication of the facultative symbiont B. aphidicola (BR treatment) were significant in all external morphological characteristics evaluated. A decrease in total body length, width, and weight of BCAs from all three climate types was observed (Table 1; Fig. 4A–I). It is worth noting that the reduction in weight and size was most pronounced in the hot desert climate, followed by the cold semi-arid climate and, to a lesser extent, the humid subtropical climate.

Effects of Buchnera-reduced (BR) infection on morphological characteristics of adults (in mm and mg) including length, width, and weight in adults of black cowpea aphids. Specimens of BCA were collected from alfalfa crops cultivated under (A–C) cold semi-arid (CS) climate, (D–F) humid subtropical (HS) climate, and (G–I) hot desert (HD) climate. The flag levels of significance (NS, **, and ***) indicate significant differences (t-test, NS P > 0.05; ** P < 0.05; *** P < 0.001).

Discussion

The microbiome provides a number of services to its insect hosts, including facilitating nutrition and adaptation to the environment27. Climate variability exerts a profound influence on the distribution, function, and stability of aphid symbiotic associations, shaping both obligate and facultative bacterial infections28. The bacterial diversity in aphids is closely related to the climate and geographical location15,29. The symbionts in aphid has been found to correlate with climatic variables30. The findings of this study provide further evidence that the obligate nutrient-provisioning symbiont B. aphidicola is essential for the normal life cycle and reproductive functions of the BCAs, particularly in cold semi-arid and hot desert climates. In the absence of B. aphidicola, a medium alteration of these biological parameters was observed in BCAs from cold semi-arid climates and severe alterations in BCAs from hot desert climates. Conversely, the absence of significant changes on life cycle and reproductive parameters in the humid subtropical climates suggests that other factors, such as the presence of specific facultative symbionts, may compensate for the eradication of B. aphidicola in these environments.

It has been demonstrated that aphids carry one or more facultative symbionts. These symbionts, although not essential for survival or reproduction, have been shown to provide protection against entomopathogenic fungi and parasitoid wasps6,7,8,9,10, to ameliorate the detrimental effects of heat, and to influence host plant suitability. As expected, the removal of B. aphidicola via antibiotic treatments had a considerable negative impact on BCAs fitness31. However, BCAs that carried at least one facultative symbiont, such as Arsenophonus sp. in cold semi-arid regions, exhibited less detrimental effects on reproductive parameters following the removal of the obligate symbiotic bacterium B. aphidicola compared to those in hot desert climates that lacked facultative symbionts. In addition to Arsenophonus sp., two other facultative symbionts, H. defensa, and S. symbiotica, were detected molecularly in BCAs from the humid subtropical climate. The exclusive presence of S. symbiotica in this type of climate could be play a pivotal role in supporting the aphids’ survival32 particularly in this more humid environment. It has been reported that S. symbiotica contributes to the aphid’s stress tolerance and adaptability in different environments33, thereby helping to protect against thermal stress, improving the aphid’s resistance to pathogens, and compensating for deficiencies in the host’s obligate symbiont, Buchnera34.

In other words, the findings indicated that in the absence of the obligate symbiotic bacterium B. aphidicola, the facultative symbiont bacteria are a prerequisite for aphid survival32. In this study, the total body size and weight of adults of BCAs from all three climate types decreased significantly. Additionally, in the absence of facultative symbionts such as in BCAs from the hot desert climate, the removal of the obligate symbiotic bacterium renders the aphid unable to rely on any assistance system to support its survival35. It is evident that facultative symbiotic bacteria, in exchange for the benefits they provide to their host, play a crucial and compensatory role in the survival of the host in diverse environmental conditions36,37. The presence of a greater number of facultative symbionts, for example, Arsenophonus sp., H. defensa, and S. symbiotica in of BCAs infesting alfalfa crops cultivated in a humid subtropical climate, provides compelling evidence that particularly the presence of S. symbiotica plays a pivotal supportive role, particularly during life cycle stages and reproductive function, as observed in this type of climate. This facultative symbiont assists its aphid hosts in tolerating diverse environmental stresses, functioning as a co-obligate symbiont38, a trait not commonly ascribed to other facultative bacterial endosymbionts to date. In contrast, the facultative bacteria Arsenophonus and H. defensa have been demonstrated to promote the suppression of parasitoids and pathogens, thereby enabling its hosts to enhance their survival prospects within their respective environments. However, some research findings have indicated that the interaction between aphids infected with Arsenophonus or H. defensa does not invariably result in the prevention of parasitism39.

The findings support the hypothesis that the diversity and the functional quality of facultative bacterial symbionts in BCAs significantly influence the duration of developmental stages, reproductive parameters, and external morphological characteristics in adults, which significantly influences their survival in absence of its obligate symbiont B. aphidicola. Additionally, parameters as biological traits and defense against natural enemies has been reported highly climate-dependent14,40. In a humid subtropical climate, which provides optimal conditions for the growth of both the BCAs and its host plant alfalfa, the BCAs possess a set of three facultative symbionts that enhance their hosts’ resilience against stresses caused by the loss of its obligate symbiont. In cold semi-arid climates, BCAs exhibited a low diversity of symbionts (with only Arsenophonus sp. detected), which resulted in a diminished capacity to assist its aphid host in surviving compared to those in humid subtropical climates. In a hot desert climate, the arid and elevated temperature appear to impede the selection of BCAs as a potential host for facultative symbiotic bacteria.

The findings indicated that the structure devised in this study was sufficient to facilitate a logical progression from baseline observations to experimental outcomes. This progression encompassed two aspects: an examination of the the prevalence of a distinct set of symbionts across various climate types, and an assessment of the effects on parameters subsequent to the eradication of the obligate symbiont. The variability in aphid responses observed across different climates underscores the significance of environmental context in shaping aphid-symbiont interactions.

Conclusions

As is widely recognized, the relationship between aphids and their symbionts is characterized by a high degree of intricacy and multifaceted complexity. In this study, the interplay between climate, symbionts, and host biology suggested that symbiont composition plays a significant role in aphids’ adaptability, particularly in extreme climates, such as the hot desert climate. The findings have significant implications for pest management strategies. The disruption of symbiotic relationships has the potential to induce alterations in aphid fitness, thereby possibly paving the way for the facilitation of biological control efforts.

A more profound comprehension of these microbial associations is imperative, as it may offer novel strategies for managing aphid populations in agricultural settings, particularly in regions where climate-driven symbiont variation exists. Furthermore, the role of facultative symbionts such as S. symbiotica in mitigating the adverse effects after the eradication of B. aphidicola under certain climates (e.g., humid subtropical) highlights a new dimension in understanding host-symbiont dynamics. This, in turn, opens avenues for targeted interventions in ecological contexts. These findings underscore the importance of integrating symbiont biology into pest control frameworks, offering more sustainable and climate-resilient approaches to managing aphid outbreaks.

Material and methods

Sampling sites

Sampling was conducted during the typical alfalfa growth period in the northern, northeastern, and southeastern regions of Iran, in accordance with standard practice. This period extends from mid-March to mid-October 2021. The BCAs were collected from alfalfa farms situated in three discrete climatic regions (Table S1). The farms were situated in Mashhad (Razavi Khorasan province, located in the northeastern region), which has a cold semi-arid (CS) climate; Rasht (Guilan province, located in the northwest region), which has a humid subtropical (HS) climate; and Zabol (Sistan and Baluchestan province, located in the southeastern region), which has a hot desert (HD) climate. The classification of these climate types is in accordance with the Köppen climate classification scheme41.

Rearing specimens

A total of 27 BCA colonies were established from specimens collected from alfalfa leaves selected at random. Thus, colonies I-IX were derived from the Rasht site, colonies X-XVIII from the Mashhad site, and colonies XIX and XXVII from the Zabol site. To initiate the female lines, young female foundresses were released individually onto alfalfa pots in a growth chamber and reared at a temperature of 21˚C, with a relative humidity (RH) of 60%, and a photoperiod of 16L:8D. To prevent overcrowding and alate production, asexual wingless females were transferred to new alfalfa plants as needed (approximately monthly). All BCAs were maintained under identical conditions from the time of colony establishment until the experiments were conducted. The experimental alfalfa plants in pots were housed in mesh-covered cylindrical cages (35*20 cm; height*diameter). The BCA clones were procured from established colonies and those specimens were utilized then in all the experiments.

BCAs naturally infected with Buchnera (Control Group, CG)

The presence of the obligate symbiont B. aphidicola, as well as four facultative symbionts (Arsenophonus sp., Hamiltonella defensa, S. symbiotica, and Regiella insecticola) in BCA clones was evaluated. Consequently, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis with specific primers (Table S2) was conducted on ten first-instar nymphs from each alfalfa crop cultivated in three distinct climatic zones (CS, HS, and HD). Following the confirmation of the presence of B. aphidicola in the BCA clones, the process of eradicating this obligate symbiont was initiated.

Buchnera-reduced (BR) infection, (experimental group)

The second-instar nymphs of the BCA clones were reared on their natural alfalfa hosts and fed an artificial diet containing rifampicin, a common antibiotic (McLean, pers. comm.). Rifampicin was employed as a means of targeting B. aphidocola. The alfalfa leaves were placed within Eppendorf tubes containing a solution of rifampicin (100 mg/mL) (Research Products International, IL, USA). Subsequently, the excised alfalfa leaf stalks were immersed in the rifampicin solution, and the interstitial space between the stalks and the Eppendorf tube edges was sealed with parafilm to prevent the solution from spilling. Then, second-instar nymphs of aphids were then permitted to feed on the treated alfalfa leaves for a period of three to four days in a controlled environment room at 14˚C. In order to ensure the eradication of the target bacterium, the aphids were re-treated with the antibiotic solution following a two-day period of rest and recuperation from the initial infection. Subsequently, the BCAs were placed on individual treated alfalfa leaves and monitored for survival. A total of 30 first-instar nymphs (10 from SC, 10 from HS, and 10 from HD) produced by these mature females were subjected to DNA extraction in order to estimate the effectiveness of this method in removing obligate symbiotic bacteria. These diagnostic PCR tests (standard PCR) were conducted to ascertain whether the antibiotic had any effect on the status of the natural B. aphidocola infection in aphids. The presence or absence of the obligate and facultative symbionts was tested before and after antibiotic use. This was done in independent diagnostic PCR experiments using positive and negative controls, as well as PCR products, all of which were amplified with specific primers (Table S2). The positive control includes the target DNA sequence. In the negative control, the template DNA is missing and no band is visible in the gel. The PCR amplifications were conducted in accordance with the following conditions: initial denaturation at 93 °C for 3 min, 30 cycles of denaturation at 93 °C for 30 s, annealing at 50 °C to 52 °C (depending on the primers) for 30 s, extension at 72 °C for 1 min, and a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. In summary, three treatments were devised, comprising BCA clones subjected to the annihilation of B. aphidicola (Buchnera-reduced infection), which were derived from the three climatic zones (HD, HS, and CS).

Parameters evaluated on BCAs

Quantification of parameters was conducted for forty first instar nymphs derived from each Buchnera-reduced (BR) infection, as well as for a control group of aphids (BCA clones of the established colonies). The first instar nymphs were transferred individually into the experimental units, which consisted of opaque plastic containers (15 cm × 13 cm × 5 cm). Ten adult black cowpea aphids were randomly selected from each treatment and control group for measurement. Subsequent to the daily monitoring of each experimental unit, parameters of the BCAs were assessed.

The parameters comprised three distinct categories: life cycle stages (7), reproductive traits (6), and external morphological characteristics of adults (3). The life cycle stages, measured in days, included lifespan of nymphal stage 1 to nymphal stage 4, lifespan of adult stage, and total lifespan. The reproductive parameters included pre-nymph (duration of pre-nymph production period), nymphing (duration of nymphal production period), post-nymphing (period after completion of nymphal production), first nymphing age (duration of first age of onset of nymphal production), daily fertility (number of offspring produced by the females each day), and nymph production (rate of nymphal generation or number of offspring produced in the lifespan). Finally, the external morphological characteristics of adults comprised length (mm), width (mm), and weight (mg). The total number of parameters measured for each replicate was sixteen. The body size of adult aphids was measured using a Leica S APO stereomicroscope (Leica® Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) at 12.6 × magnification (precision: ± 0.01 mm), while body weight was determined by employing an analytical high-precision electronic balance with a resolution of 1/100,000 (Sartorius® Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

Statistical analysis

In order to ascertain whether there were significant differences in fitness of the all sixteen parameters between BCAs naturally infected with Buchnera (CG) and those exhibiting a Buchnera-reduced (BR) infection, a parametric Student’s t-test (P < 0.05) was performed for each of the three sampling locations, assuming independence, normal distribution, and homogeneity of variance. The data were analyzed using the R software42. The t-tests were performed with the “nlme” package, while independent t-tests were conducted with the “tidyverse” package. Data visualization was performed using Matplotlib v3.9.243 and Python v3.1344.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Hrček, J., McLean, A. H. & Godfray, H. C. J. Symbionts modify interactions between insects and natural enemies in the field. J. Anim. Ecol. 85(6), 1605–1612. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.12586 (2016).

Bright, M. & Bulgheresi, S. A. complex journey: Transmission of microbial symbionts. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8(3), 218–230. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro2262 (2010).

Salem, H. & Kaltenpoth, M. Beetle–bacterial symbioses: endless forms most functional. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 67(1), 201–219. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ento-061421-063433 (2022).

Guo, J. et al. Nine facultative endosymbionts in aphids. A review. J. Asia Pac. Entomol. 20(3), 794–801. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aspen.2017.03.025 (2017).

Douglas, A. E. Multiorganismal insects: Diversity and function of resident microorganisms. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 60(1), 17–34. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ento-010814-020822 (2015).

Oliver, K. M., Russell, J. A., Moran, N. A. & Hunter, M. S. Facultative bacterial symbionts in aphids confer resistance to parasitic wasps. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 100(4), 1803–1807. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0335320100 (2003).

Montllor, C. B., Maxmen, A. & Purcell, A. H. Facultative bacterial endosymbionts benefit pea aphids Acyrthosiphon pisum under heat stress. Ecol. Entomol. 27(2), 189–195. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2311.2002.00393.x (2002).

Russell, J. A. & Moran, N. A. Costs and benefits of symbiont infection in aphids: Variation among symbionts and across temperatures. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 273(1586), 603–610. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2005.3348 (2006).

Scarborough, C. L., Ferrari, J. & Godfray, H. C. J. Aphid protected from pathogen by endosymbiont. Science 310(5755), 1781–1781. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1120180 (2005).

Łukasik, P. et al. Horizontal transfer of facultative endosymbionts is limited by host relatedness. Evolution 69(10), 2757–2766. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.12767 (2015).

Simon, J. C. et al. Facultative symbiont infections affect aphid reproduction. PLoS ONE 6(7), e21831. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0021831 (2011).

Tsuchida, T. et al. Symbiotic bacterium modifies aphid body color. Sci. 330(6007), 1102–1104. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1195463 (2010).

Augustinos, A. A. et al. Detection and characterization of Wolbachia infections in natural populations of aphids: Is the hidden diversity fully unraveled?. PLoS ONE 6(12), e28695. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0028695 (2011).

Oliver, K. M., Degnan, P. H., Burke, G. R. & Moran, N. A. Facultative symbionts in aphids and the horizontal transfer of ecologically important traits. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 55(1), 247–266. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ento-112408-085305 (2010).

Brady, C. M. et al. Worldwide populations of the aphid Aphis craccivora are infected with diverse facultative bacterial symbionts. Microb. Ecol. 67, 195–204. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00248-013-0314-0 (2014).

Mestre, A., Poulin, R. & Hortal, J. A niche perspective on the range expansion of symbionts. Biol. Rev. 95(2), 491–516. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12574 (2020).

Vorburger, C., Gehrer, L. & Rodriguez, P. A. Strain of the bacterial symbiont Regiella insecticola protects aphids against parasitoids. Biol. Lett. 6(1), 109–111 (2010).

Oliver, K. M., Smith, A. H. & Russell, J. A. Defensive symbiosis in the real world–advancing ecological studies of heritable, protective bacteria in aphids and beyond. Funct. Ecol. 28, 341–355. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.12133 (2014).

Doremus, M. R., Stouthamer, C. M., Kelly, S. E., Schmitz-Esser, S. & Hunter, M. S. Cardinium localization during its parasitoid wasp host’s development provides insights into cytoplasmic incompatibility. Front. Microbiol. 11, 606399. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.606399 (2020).

Gimmi, E. & Vorburger, C. High specificity of symbiont-conferred resistance in an aphid-parasitoid field community. J. Evol. Biol. 37(2), 162–170. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeb/voad013 (2024).

Renoz, F. et al. Compartmentalized into bacteriocytes but highly invasive: the puzzling case of the co-obligate symbiont Serratia symbiotica in the aphid Periphyllus lyropictus. Microbiol. Spectr. 10(3), e00457-e522. https://doi.org/10.1128/spectrum.00457-22 (2022).

Kikuchi, Y. et al. Collapse of insect gut symbiosis under simulated climate change. MBio 7(5), 10–1128. https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.01578-16 (2016).

Jeffs, C. T. & Lewis, O. T. Effects of climate warming on host–parasitoid interactions. Ecol. Entomol. 38(3), 209–218. https://doi.org/10.1111/een.12026 (2013).

Tucak, M. et al. Variation of phytoestrogen content and major agronomic traits in alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) populations. Agronomy 10(1), 87–11. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy10010087 (2020).

Summers, C. G. Integrated pest management in forage alfalfa. IPM Rev. 3(3), 127–154. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009654901994 (1998).

Brady, C. M. & White, J. A. Cowpea aphid (Aphis craccivora) associated with different host plants has different facultative endosymbionts. Ecol. Entomol. 38(4), 433–437. https://doi.org/10.1111/een.12020 (2013).

Chabanol, E. & Gendrin, M. Insects and microbes: Best friends from the nursery. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cois.2024.101270 (2024).

Iltis, C., Tougeron, K., Hance, T., Louâpre, P. & Foray, V. A perspective on insect–microbe holobionts facing thermal fluctuations in a climate-change context. Environ. Microbiol. 24(1), 18–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/1462-2920.15826 (2022).

Zhao, Y. et al. Bacterial communities of the cotton aphid Aphis gossypii associated with Bt cotton in northern China. Sci. Rep. 6(1), 22958. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep22958 (2016).

Tsuchida, T., Koga, R., Shibao, H., Matsumoto, T. & Fukatsu, T. Diversity and geographic distribution of secondary endosymbiotic bacteria in natural populations of the pea aphid, Acyrthosiphon pisum. Mol. Ecol. 11(10), 2123–2135. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-294x.2002.01606.x (2002).

Liu, S. et al. Effects of host plants on aphid feeding behavior, fitness, and Buchnera aphidicola titer. Insect Sci. https://doi.org/10.1111/1744-7917.13428 (2024).

Lamelas, A. et al. Serratia symbiotica from the aphid Cinara cedri: a missing link from facultative to obligate insect endosymbiont. PLoS Genet. 7(11), e1002357. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1002357 (2011).

Wang, Z. W. et al. The endosymbiont Serratia symbiotica improves aphid fitness by disrupting the predation strategy of ladybeetle larvae. Insect Sci. https://doi.org/10.1111/1744-7917.13315 (2024).

Zhou, X. et al. Serratia symbiotica enhances fatty acid metabolism of pea aphid to promote host development. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22(11), 5951. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22115951 (2021).

Koga, R., Tsuchida, T. & Fukatsu, T. Changing partners in an obligate symbiosis: A facultative endosymbiont can replace a primary endosymbiont in an aphid. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 270(1533), 2543–2550 (2003).

Douglas, A. E. Nutritional interactions in insect-microbial symbioses: Aphids and their symbiotic bacteria Buchnera. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 43, 17–37. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ento.43.1.17 (1998).

Oliver, K. M., Moran, N. A. & Hunter, M. S. Costs and benefits of a superinfection of facultative symbionts in aphids. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 273(1591), 1273–1280 (2006).

Pons, I., Renoz, F. & Hance, T. Fitness costs of the cultivable symbiont Serratia symbiotica and its phenotypic consequences to aphids in presence of environmental stressors. Evol. Ecol. 33, 825–838. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10682-019-10012-5 (2019).

Heidari Latibari, M. et al. Arsenophonus: A double-edged sword of aphid defense against Parasitoids. Insects 14, 763–776. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects14090763 (2023).

Csorba, A. B. et al. Aphid adaptation in a changing environment through their bacterial endosymbionts: An overview, including a new major cereal pest (Rhopalosiphum maidis (Fitch) scenario. Symbiosis 93(2), 139–152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13199-024-00999-z (2024).

Köppen, W. Köppen-Geiger climate classification system. Köppen climate classification—Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/K%C3%B6ppen_climate_classification Accessed 21 July 2024 (2024).

R Core Team R: A language and environment for statistical computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2024). https://www.R-project.org/.

Hunter, J. D. Matplotlib: A 2D graphics environment. Comput. Sci. Eng. 9(3), 90–95 (2007).

Python Software Foundation. Python 3.13 Documentation. Retrieved from https://docs.python.org/3.13/ (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their sincerest gratitude to Jan Hrček and Anna Macova (Biology Centre CAS, Czech Republic), Kerry Oliver (University of Georgia, USA), Ailsa McLean (University of Oxford, UK), Christoph Vorburger (ETH Zürich, Switzerland), Jennifer A. White (University of Kentucky, USA), Julia Ferrari (University of York, UK), Olivier Duron (FNCS, France), and Donald L. J. Quicke (Chulalongkorn University, Thailand) for their invaluable contribution in the form of advice and insights. We would also like to express our gratitude to the editor, Michael E. Loik, and the anonymous reviewers whose constructive feedback significantly improved our manuscript.

Funding

MHL was financed by the Second Century Fund (C2F), Chulalongkorn University, Thailand. BAB is financed by Thailand Science Research and Innovation Fund, Chulalongkorn University (BCG_FF_68_178_2300_039).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.H.L. conceived of the presented idea, developed the theory, and performed the fieldwork and laboratory activities. B.A.B. and M.G.M. verified the methods, analysis, and results. MHL took the lead in writing the manuscript with support from B.A.B., D.C.A.P. and M.G.M. All authors discussed the interpretation of the results, provided critical feedback, and contributed to the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Heidari Latibari, M., Carolina Arias-Penna, D., Ghafouri Moghaddam, M. et al. Bacterial symbiont as game changers for Aphis craccivora Koch’s fitness and survival across distinct climate types. Sci Rep 15, 14208 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98690-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98690-w