Abstract

This study examines healthcare utilization patterns among Japan’s older population (aged 75 and above) during a prolonged public health emergency, focusing on the later phase of the COVID-19 pandemic (November 2021–September 2022). This period was characterized by the Omicron variant, widespread vaccination coverage, and adapted public health measures. Using a comprehensive dataset of 189,841,257 medical claims linked with income tax records, we analyze how healthcare utilization correlates with public health measures, pandemic severity, and income levels. Our findings reveal distinct utilization patterns: moderate decreases in healthcare visits during periods of public health measures, with the association between pandemic severity and healthcare use varying based on whether these measures are in place. Despite fluctuations in visit frequency, healthcare costs remain stable, indicating consistent service intensity. While income-related differences in general healthcare access are modest, dental care shows more pronounced socioeconomic variations. These patterns suggest a transition from initial widespread healthcare avoidance to more stable healthcare engagement, indicating adaptation to prolonged crisis conditions. Our findings provide insights for maintaining healthcare access during extended public health emergencies, particularly in aging societies where balancing healthcare needs with public health measures is crucial.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Public health crises, from infectious disease outbreaks to natural disasters, can profoundly disrupt healthcare systems and alter how people access healthcare. These disruptions often disproportionately affect vulnerable populations, particularly older population who typically require regular medical attention yet may be most hesitant to seek care during emergencies. The COVID-19 pandemic, with its unprecedented duration and global reach1,2,3, offers a unique opportunity to examine how healthcare systems and vulnerable populations adapt to prolonged public health emergencies.

Initial responses to the pandemic are well-documented, revealing widespread healthcare avoidance4,5,6. Studies highlight significant declines in hospital admissions at the pandemic onset, alongside decreases in both urgent/emergency and routine care7,8,9. This global trend of reduced healthcare utilization, coupled with increased mortality rates from non-COVID conditions, highlighted the severe consequences of delayed medical care during crises4,10. Although these studies effectively capture immediate responses to an acute crisis, less is known about long-term adaptation in healthcare-seeking patterns, particularly among vulnerable populations who must balance ongoing healthcare needs with crisis-related risk11,12.

For understanding these long-term adaptation patterns, Japan’s experience during the pandemic offers particularly valuable insights. As the world’s most aged society with a universal healthcare system13, Japan represents an important case study of how healthcare systems can balance sustained access with public health risk management. The lessons from Japan’s experience may become increasingly relevant as other countries also face demographic aging and the growing challenge of protecting healthcare access for older population during emergencies11,12,14.

This study examines healthcare utilization patterns among Japan’s oldest-old population (i.e., aged 75 and above) during the later phase of COVID-19 pandemic. Using a comprehensive dataset linking medical claim records with income tax information, we analyze how healthcare utilization correlates with public health measures, crisis severity, and socioeconomic status. We observe moderate decreases in healthcare visits during periods with public health measures, with the relationship between pandemic severity and healthcare utilization varying by the presence of these measures. Despite fluctuations in visit frequency, overall healthcare costs remain stable, suggesting adaptations in how care is accessed rather than reductions in necessary treatment. We also find that while income-related differences in general healthcare access are modest, dental care show pronounced socioeconomic variations, indicating differential adaptation patterns across healthcare services.

These findings contribute to our understanding of healthcare system resilience during public health emergencies. By examining how vulnerable populations modify healthcare access during a prolonged crisis, our study provides insights that may help inform efforts to maintain essential healthcare access during future emergencies, particularly in aging societies.

Methods

Study context

Japan reported its first COVID-19 case on January 16, 2020, marking the beginning of unprecedented challenges to the nation’s public health infrastructure15. Over the next three years, Japan experienced eight distinct infection surges, each prompting evolving governmental and public health responses.

Figure 1 illustrates Japan’s COVID-19 case trends and emergency responses from January 2020 through May 2023. The early waves (I-V) were characterized by the original SARS-CoV-2 strain and its Alpha and Delta variants16. During this period, Japan implemented rigorous measures at the prefecture level, including States of Emergency (SoE) and States of Precautionary Emergency (SoPE). SoE involved stringent but non-binding regulations to curb public gatherings and reinforce social distancing, while SoPE aimed to control the virus’s spread through less severe public health measures17. Notably, unlike many countries that imposed mandatory lockdowns, these measures represented strong recommendations rather than legally enforced restrictions, reflecting Japan’s distinctive strategy of encouraging voluntary behavioral changes rather than imposing strict lockdowns. The later waves (VI-VIII) were primarily driven by the Omicron variant, which, despite its high transmissibility, was typically associated with milder clinical outcomes18. This shift was reflected in Japan’s public health response, with the government implementing less stringent measures SoPE and eventually lifting all emergency declarations after Wave VI.

Newly confirmed COVID-19 cases and governmental emergency responses. Notes: COVID-19 case data were obtained from the official governmental website19. The data collection ended on May 7, 2023, due to the reclassification of COVID-19 to a Category V Infectious Disease. Information regarding the enforcement of SoE and SoPE policies was gathered from the official website of the Cabinet Agency for Infectious Diseases Crisis Management20. The gray shaded area in both graphs denotes the study period.

In the early stages of the pandemic, widespread uncertainty and fear dominated. Public health messages urging people to shelter in place17, combined with the fear of contracting the virus in healthcare setting21, led to significant healthcare avoidance, especially among the older population. As the pandemic progressed, several factors may have influenced their healthcare utilization patterns, including widespread vaccine distribution22, enhanced infection control measures in healthcare facilities23, and more targeted public health messages24. These factors suggest that healthcare utilization patterns among Japan’s older population may have undergone a significant shift, moving from widespread avoidance in the pandemic’s early stages to more stable engagement later. Understanding these evolving patterns is valuable for developing effective healthcare strategies and policies for this vulnerable population during prolonged health crises.

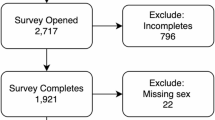

Data sources and sample construction

Our primary data source is the Medical Claims Data with Income Tax Information for the Oldest-Old in Japan (MCD-Tx), a comprehensive dataset of Japan’s Latter-Stage Elderly Healthcare System (LSEH) collected by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW). The LSEH is Japan’s universal healthcare system for the 75+ population, and as of September 2022, it covered 18.52 million individuals, comprising 98.6% of Japan’s 75 + population.

The MCD-Tx, spanning from November 2021 to November 2022, captures all LSEH enrollees, regardless of their healthcare service utilization. For each individual, the dataset provides detailed monthly healthcare utilization and cost information from medical claims, linked with individual demographic and socioeconomic data including income information. This dataset represents the first instance in Japan where income information is integrated with medical claims data. Informed consent was waived by the Ethics Review Committee for Research Involving Human Subjects at Waseda University (Approval No.: 2022-HN038). As this study used anonymized secondary data, the requirement for informed consent was waived by the ethics committee. Furthermore, all methods used in this study were conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations regarding using data of human participants.

To complement the MCD-Tx, we incorporated three additional datasets. The first tracks daily new COVID-19 cases at the secondary medical region (SMR) level—administrative units organized around specialized healthcare facilities that provide more granular geographical resolution than prefectures—from the onset of Japan’s first reported case until September 2022. The second dataset provides biweekly records of hospital beds designated for COVID-19 patients and actual admissions at the SMR level, from December 2021 to April 2023. The third dataset covers the daily implementation status of SoE and SoPE at the prefecture level, from March 2020 to September 2022.

In constructing our sample, we first convert these three supplementary datasets to a monthly format. We then link them with the MCD-Tx claim records based on the SMR or prefecture of residence of the oldest-old (detailed linkage procedures are described in Appendix A). The final sample covers an 11-month period from November 2021 to September 2022, capturing the later phase of the pandemic (Waves VI and VII). This sample includes 1,769,537 individuals aged 75+ and 189,841,257 associated health insurance claim records.

Measurements

Our analysis examines both extensive and intensive margins of healthcare utilization. For the extensive margin, we construct four binary indicators associated with different healthcare services: overall healthcare utilization, hospital admission, outpatient visits, and dental care. Each indicator takes a value of one if an individual use the respective service within a given month, and zero otherwise. As shown in Table 1 and 84.2% of our sample access some form of healthcare during the study period, with outpatient visits being the most common (78.5%), followed by dental services (20%), while hospital admissions are less frequent (5.4%).

For the intensive margin, we analyze four variables representing monthly medical costs: total costs, inpatient costs, outpatient costs, and dental costs (measured in 10,000 Japanese Yen, JPY). Among those who utilize services, average monthly inpatient care costs (651,320 JPY) are substantially higher than outpatient care (43,370 JPY) and dental care costs (14,630 JPY).

To measure pandemic conditions, we construct two variables. The first captures pandemic severity through the monthly aggregated number of new COVID-19 cases per million people within each SMR, averaging 0.013 during our study period. The second indicates the presence of SoPE measures, taking a value of one for months with active measures in the resident’s prefecture (present in 26% of our study period). Notably, no prefecture implemented SoE measures during our study timeframe.

Our models include several control variables to account for individual characteristics and healthcare capacity. Individual-level controls comprise age quintiles (ranging from mean age 75.56 years in Q1 to 92.25 years in Q5), income quintiles (from mean 37.42 million JPY in Q1 to 554.22 million JPY in Q5), and gender (39.8% male). We also include indicators for non-COVID-19 main diagnoses in both inpatient and outpatient care, with cardiac conditions being most prevalent (22.1% of hospitalizations and 26.7% of outpatient visits). Healthcare capacity is measured through COVID-19 hospital bed occupancy quintiles, ranging from 5.0 to 68.6%, reflecting regional variations in healthcare system strain during the pandemic.

Analytical approach

We use two complementary models to examine healthcare utilization patterns. Our first model analyzes the association between SoPE measures and healthcare utilization:

Here, \({Y}_{ijt}\) represents healthcare utilization and costs for individual \(i\) in SMR \(j\) at time \(t\). \(SoP{E}_{jt}\) is the indicator of SoPE measures, our primary variable of interest. We anticipate healthcare utilization to be negatively associated with SoPE implementation, consistent with documented healthcare avoidance patterns. The relationship between medical costs and SoPE measures may be more complex, potentially showing either negative associations due to fewer visits or positive associations if delayed care leads to more intensive treatment needs. \(f\left(COVI{D}_{jt}\right)\) represents a quadratic polynomial function of new COVID-19 cases. The quadratic specification captures potential non-linear patterns in the relationship between case numbers and healthcare utilization, allowing for diminishing marginal correlations at higher case levels. \({X}_{ijt}\) represents individual characteristics and healthcare capacity controls. The model incorporates year-month fixed effects \({\delta}_{t}\), geographic fixed effects at the SMR level \({\eta}_{j}\), and geographic linear trends \({\tau}_{j}t\) to control for unobserved temporal and regional variations. \({\varepsilon}_{ijt}\) denotes the error term, with standard errors clustered at the SMR level.

Our second model examines how the association between healthcare utilization and pandemic severity varies with public health measures:

This model fully interacts the SoPE indicator with the quadratic function of case numbers, allowing us to examine whether the relationship between pandemic severity and healthcare utilization differs during periods with and without public health measures. To interpret these relationships, we calculate average marginal effects of changes in case numbers at different pandemic severity levels, ranging from low (below 0.04 cases per million) to high (above 0.14 cases per million).

To assess the robustness of our approaches, we conduct additional analyses (see Appendix B). We estimate models with a linear specification of pandemic severity as an alternative to our quadratic specification. We also perform subgroup analyses by age groups (75–84 and 85+) and gender to examine potential heterogeneity in patterns. These analyses reveal patterns consistent with our main findings, suggesting that the observed relationships between healthcare utilization, public health measures, and pandemic severity are robust across specifications and subpopulations.

Results

Healthcare utilization during the sope period

We first examine patterns in healthcare service utilization among Japan’s oldest-old during periods with and without SoPE measures. Table 2 presents four models based on Eq. (1) with increasing complexity, from basic controls in Model 1 to a full consideration of the pandemic’s nonlinear patterns, individual attributes, and healthcare system capacity in Model 4. The observed relationships remain consistent across all models in both direction and magnitude. We focus our discussion on the most comprehensive Model 4.

During SoPE periods, we observe lower overall healthcare engagement by 0.73% points (0.86% below the mean). Similar patterns emerge for outpatient visits and dental care, which are lower by 0.77 and 0.16% points respectively (0.98% and 0.77% below their respective means). For healthcare costs, outpatient costs during SoPE periods are lower by 2170 JPY (0.50% below the mean). Notably, we find no systematic differences in inpatient and dental costs during SoPE periods, suggesting that while fewer people may seek these services, the intensity of care among those who do remains stable.

Pandemic severity and healthcare utilization

Figure 2 illustrates how healthcare utilization patterns relate to pandemic severity based on Eq. (2), revealing distinct patterns during periods with and without SoPE measures. For overall healthcare utilization, periods without SoPE show a negative relationship with rising COVID-19 cases, with an average marginal effect (AME) of − 2.5% points (2.97% below the mean). In contrast, during SoPE periods, we observe a positive relationship with an AME of 4.2% points (4.99% above the mean).

Pandemic severity and healthcare utilization patterns. Notes: The figure presents eight regression analyses based on Eq. (2), examining healthcare utilization and costs. Each graph displays two key elements: the estimated marginal effects across different pandemic severity levels shown by the trend lines with confidence bands, and the Average Marginal Effects (AME) both with and without SoPE shown at the bottom of each panel along with their standard errors in parentheses. The AMEs are displayed as dashed lines, with red lines corresponding to estimates with SoPE and blue lines representing estimates without SoPE. In addition to the AME, marginal effects by the severity of the pandemic are presented with shaded confidence intervals at 90% for the inner band and 95% for the outer band. The x-axis measures pandemic severity in cases per million people, with values ranging from 0 to 0.18. The difference in slopes between red and blue lines indicates how the SoPE policy moderated the relationship between case numbers and healthcare outcomes.

As pandemic severity increases, we observe an upward trend in healthcare utilization on the extensive margin regardless of SoPE measures, while the intensive margin generally trends downward. Two exceptions are hospital admission and outpatient costs. Hospital admissions show a positive relationship with case numbers at lower severity levels during SoPE periods, transitioning to negative at higher severity levels. Similarly, outpatient costs show an initial negative correlation with case numbers that shifts to positive as severity increases.

Socioeconomic patterns in healthcare utilization

Our analyses of income-stratified samples based on Eq. (1) reveal modest differences in healthcare utilization patterns across income levels. Specifically, Fig. 3 shows similar moderate decreases in healthcare utilization across all income quintiles during SoPE periods. We observe consistent patterns where healthcare utilization shows negative correlations with rising COVID-19 cases during non-SoPE periods and positive correlations during SoPE periods, regardless of income levels.

Income-related disparities in healthcare utilization patterns. Notes: Each graph in Fig. 3 is divided into three panels: “SoPE,” “Cases w/o SoPE,” and “Cases w/ SoPE.” The “SoPE” panel illustrates the marginal effect of SoPE measures as described in Eq. (1). The panels “Cases w/o SoPE” and “Cases w/ SoPE” represent the marginal effects of changes in COVID-19 case numbers without and with SoPE measures, respectively, following the specification of Eq. (2). Point estimate is presented for each marker, accompanied by bars depicting confidence intervals: the thicker bar indicates a 95% confidence interval, and the thinner white line indicates a 90% confidence interval.

Distinctive patterns in dental care

Dental care exhibits notably different patterns compared to other healthcare services. Figure 2 shows that rising COVID-19 cases associates with larger decreases in dental care utilization—18.3% points (87.98% below the mean) during the non-SoPE periods. These decreases substantially exceed those observed in other healthcare services. Figure 3 further reveals income-related variations unique to dental care: utilization decreases by 21.7% points (104.33% below the mean) in the lowest income quintile compared to 14% points (67.31% below the mean) in the highest income quintile.

Discussion

This study examines healthcare utilization patterns among Japan’s oldest-old during the later phase of the COVID-19 pandemic, providing insights into how healthcare systems and vulnerable populations adapt to prolonged public health crises.

Our analysis reveals a correlation between SoPE measures and moderate reductions in healthcare service utilization, particularly in outpatient care. This pattern differs from the sharp decreases documented in earlier pandemic stages, potentially reflecting adaptation in the later phase of the crisis25. Notably, while healthcare visit frequency shows modest decreases, healthcare costs remain relatively stable, suggesting that elderly people who continue seeking care maintain similar levels of service intensity. This pattern of adaptation—from acute avoidance to more stable utilization patterns—may represent a broader phenomenon in how healthcare systems and populations adjust to extended emergency conditions.

Healthcare utilization patterns show distinct relationships with pandemic severity during periods with and without SoPE measures. During periods without SoPE measures, higher COVID-19 cases correlate with decreased healthcare utilization. However, this pattern reverses during SoPE periods, possibly reflecting factors such as enhanced safety protocols24 or increased public confidence in healthcare facilities26. These patterns point to the dynamic nature of healthcare utilization during crises27, though we note that our approach cannot establish clear causal relationships between these factors.

The relatively modest differences in healthcare utilization patterns across income levels among Japan’s oldest-old contrast with more pronounced income-based disparities reported in other countries during the pandemic28. This observation aligns with the role of Japan’s universal health insurance in maintaining healthcare access, suggesting that structural features of health systems may significantly influence their resilience during prolonged emergencies.

Dental care utilization shows notably different patterns, marked by significant declines irrespective of whether SoPE measures are implemented. This trend likely reflects multiple factors, including the perceived high-risk nature of dental procedures during the pandemic29. The observed income-related variations in dental care utilization, even within Japan’s universal health insurance system, suggest that socioeconomic factors may influence oral health decisions during crises. These patterns raise concerns about potential long-term health implications, given the established connections between oral health and various systemic conditions among older population30,31.

This study has several limitations. First, our sample faces selection bias as it necessarily includes only individuals who survived through the study period. Those who did not survive may have had different healthcare utilization patterns, potentially leading to underestimation of crisis-related healthcare challenges. Additionally, our analysis does not account for unobserved factors that might influence healthcare decisions, such as individual risk perceptions. The absence of data on specific health outcomes also limits our ability to assess the broader health implications of the observed utilization patterns. Future research could address these limitations by incorporating mortality data, examining specific health outcomes associated with utilization changes, and applying quasi-experimental designs.

The patterns observed among Japan’s older population under the universal healthcare system during this prolonged crisis suggest several considerations for maintaining healthcare access during emergencies. Healthcare systems might benefit from developing integrated monitoring mechanisms to identify emerging care gaps, particularly in essential preventive services such as dental care. Combining enhanced safety protocols with flexible delivery models, including mobile services and remote care options, could help maintain service accessibility. Early warning systems to track utilization patterns among vulnerable groups, coupled with targeted support for high-risk but essential services, may help maintain healthcare access during various types of extended emergencies. These considerations may become increasingly relevant as healthcare systems worldwide address challenges from aging populations and various forms of public health crises.

Concluding remarks

This study examines healthcare utilization patterns during a prolonged public health emergency, with particular focus on vulnerable older populations. While our observational study design precludes causal conclusions, the documented patterns contribute to our understanding of healthcare system resilience beyond the specific context of COVID-19. The findings reveal how healthcare utilization evolves during extended crises, showing both successes and challenges in maintaining access to healthcare services. As populations age globally, and healthcare systems face various challenges—from infectious disease outbreaks to natural disasters—these insights into healthcare adaptation patterns may inform efforts to protect vulnerable populations during future prolonged emergencies.

Data availability

This study used anonymized individual data from the ‘Medical Claims Data with Income Tax Information for the Oldest-Old in Japan (MCD-Tx),’ collected and maintained by the Research Division of the Health Insurance Bureau, MHLW. The data can be obtained by applying to the MHLW (https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/sonota/chousahyo.html).

References

Cutler, D. M. & Summers, L. H. The COVID-19 pandemic and the $16 trillion virus. JAMA 324, 1495–1496 (2020).

Nicola, M. et al. The socio-economic implications of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19): A review. Int. J. Surg. 78, 185–193 (2020).

Wang, C., Horby, P. W., Hayden, F. G. & Gao, G. F. A novel coronavirus outbreak of global health concern. Lancet 395, 470–473 (2020).

Bodilsen, J. et al. Hospital admission and mortality rates for non-covid diseases in Denmark during COVID-19 pandemic: Nationwide population based cohort study. BMJ 373, (2021).

Cassell, K., Zipfel, C. M., Bansal, S. & Weinberger, D. M. Trends in non-COVID-19 hospitalizations prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic period, United States, 2017–2021. Nat. Commun. 13, 1–8 (2022).

Ziedan, E., Simon, K. I. & Wing, C. Effects of state COVID-19 closure policy on non-COVID-19 health care utilization. https://doi.org/10.3386/W27621 (2020).

Ahn, S. N., Kim, S. & Koh, K. Associations of the COVID-19 pandemic with older individuals’ healthcare utilization and self-reported health status: A longitudinal analysis from Singapore. BMC Health Serv. Res. 22, 1–8 (2022).

Czeisler, M. É. et al. Delay or avoidance of medical care because of COVID-19–related concerns—United States, June 2020. Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 69, 1250 (2020).

Dupraz, J., Le Pogam, M. A. & Peytremann-Bridevaux, I. Early impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on in-person outpatient care utilisation: A rapid review. BMJ Open. 12, e056086 (2022).

Santi, L. et al. Non-COVID-19 patients in times of pandemic: Emergency department visits, hospitalizations and cause-specific mortality in Northern Italy. PLoS One. 16, e0248995 (2021).

Powell, T., Bellin, E. & Ehrlich, A. R. Older adults and COVID-19: The most vulnerable, the hardest hit. Hastings Cent. Rep. 50, 61–63 (2020).

Shahid, Z. et al. COVID-19 and older adults: What we know. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 68, 926–929 (2020).

Sasaki, S., Kurokawa, H. & Ohtake, F. Effective but fragile? Responses to repeated nudge-based messages for preventing the spread of COVID-19 infection. Jpn. Econ. Rev. 72, 371–408 (2021).

Aung, M. N. et al. Sustainable health promotion for the seniors during COVID-19 outbreak: A lesson from Tokyo. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 14, 328–331 (2020).

Moriguchi, T. et al. A first case of meningitis/encephalitis associated with SARS-Coronavirus-2. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 94, 55–58 (2020).

Matsunaga, N. et al. Clinical characteristics of the first three waves of hospitalised patients with COVID-19 in Japan prior to the widespread use of vaccination: A nationwide observational study. Lancet Reg. Health West. Pac. 22, (2022).

Sawakami, T., Karako, K., Song, P., Sugiura, W. & Kokudo, N. Infectious disease activity during the COVID-19 epidemic in Japan: Lessons learned from prevention and control measures. Biosci. Trends. 15, 257–261 (2021).

Song, P. & Karako, T. The strategy behind Japan’s response to COVID-19 from 2020–2021 and future challenges posed by the uncertainty of the Omicron variant in 2022. Biosci. Trends. 15, 350–352 (2021).

MHLW. Visualizing the data: Information on COVID-19 infections (2023). https://covid19.mhlw.go.jp/extensions/public/en/index.html

Cabinet Agency for Infectious Diseases Crisis Management. COVID-19 Countermeasures (2023). https://corona.go.jp/emergency/

Karako, K., Song, P., Chen, Y. & Karako, T. COVID-19 in Japan during 2020–2022: Characteristics, responses, and implications for the health care system. J. Glob. Health 12, (2022).

Mattiuzzi, C. & Lippi, G. Efficacy of COVID-19 vaccine booster doses in older people. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 13, 275 (2022).

Gautier, L. et al. Hospital governance during the COVID-19 pandemic: A multiple-country case study. Health Syst. Reform. 9, (2023).

Okada, H., Okuhara, T., Goto, E. & Kiuchi, T. Association between trust in COVID-19 information sources and engaging in infection prevention behaviors in Japan: A longitudinal study. Patient Educ. Couns. 111, 107686 (2023).

Muto, K., Yamamoto, I., Nagasu, M., Tanaka, M. & Wada, K. Japanese citizens’ behavioral changes and preparedness against COVID-19: An online survey during the early phase of the pandemic. PLoS One. 15, e0234292 (2020).

Gai, R. & Tobe, M. Managing healthcare delivery system to fight the COVID-19 epidemic: Experience in Japan. Glob. Health Res. Policy. 5, 1–4 (2020).

Fridman, I., Lucas, N., Henke, D. & Zigler, C. K. Association between public knowledge about COVID-19, trust in information sources, and adherence to social distancing: Cross-sectional survey. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 6, e22060 (2020).

Patel, J. A. et al. Poverty, inequality and COVID-19: The forgotten vulnerable. Public. Health. 183, 110 (2020).

Jiang, Y., Tang, T., Mei, L. & Li, H. COVID-19 affected patients’ utilization of dental care service. Oral Dis. 28, 916 (2022).

Daly, B. et al. Evidence summary: The relationship between oral health and dementia. Br. Dent. J. 223, 846–853 (2017).

Petersen, P. E. & Yamamoto, T. Improving the oral health of older people: The approach of the WHO global oral health programme. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 33, 81–92 (2005).

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to Hidetake Endou, Kenji Suzuki, Kousuke Kashimura, and Takashi Ninishioka in the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare for their valuable feedback. This research received support from the Health Labour Sciences Research Grant (Research on Policy Planning and Evaluation) provided by the MHLW under Grant Number 22AA1002, with Haruko Noguchi serving as the Principal Investigator.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.F. conceived the study, conducted the analysis, and drafted the manuscript. S.L. assisted with data colletcion. M.O. contributed to the study design and interpretation of results. H.N. supervised the project and provided critical revisions. A.K. contributed to the interpretation of results and manuscript revision. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and informed consent

The study was reviewed and deemed exempt from ethical review by the Ethics Review Committee for Research Involving Human Subjects at Waseda University (Approval No.: 2022-HN038; Approval Date: November 25, 2022, please see the website: https://www.waseda.jp/inst/ore/procedures/). The data provided contains no personally identifiable information.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fu, R., Liu, S., Oikawa, M. et al. Healthcare utilization among Japanese older adults during later stage of prolonged pandemic. Sci Rep 15, 13813 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98908-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98908-x