Abstract

With the deteriorating global environment, the increasing demand for energy sources, humanity urgently need to explore clean and renewable energy to replace coal fuel resources in the field of tobacco curing. Biomass, a more environment-friendly energy source, is widely used but shows inconsistent results for many types of biomass combustion equipment in China. To provide basis for the clean curing, quality enhancement and curing efficiency improvement of tobacco leaves, the effect of five different types of biomass combustion equipment bulk curing barn (T1, a built-in biomass bulk curing barn with a special hearth for burning through a smoke pipe; T2, an external biomass bulk curing barn with a flame pipe through a smoke pipe; T3, a biomass semi-gasification combustion heating furnace bulk curing barn with a built-in hearth; T4, a type I built-in biomass bulk curing barn with integrated heat supply and heat exchange; T5, a type II built-in biomass bulk curing barn with integrated heat supply and heat exchange) on curing performance, biomass combustion efficiency, pollutant emissions, curing cost, economic characters, chemical composition content, aroma substance content and sensory quality of flue-cured tobacco leaves were compared and analyzed. Our results showed that the curing effect of the T4 and T5 treatments was better, the T2 treatment was worse, while the other treatments were moderate. In our data, the T4 and T5 treatments exhibited good curing temperature -rise performance and stable temperature performance with smaller temperature deviations. In addition, the T4 and T5 treatments resulted in lower curing costs, exhibited better economic characteristics, achieved more favorable coordination of chemical composition, offered superior sensory quality, and had a higher content of aroma substances in the flue-cured tobacco leaves compared to the other treatments. The curing effect of the built-in biomass bulk curing barn with integrated heating and heat exchange is superior, providing an important basis for the current low-carbon clean energy curing practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The predominant consumption of fossil fuels, which is the primary cause of the global greenhouse effect and ecological environmental issues, has heightened the need for CO neutrality1,2,3. Key pollutants like SO2 and nitrogen oxides are significant in China, prompting an increased focus on environmental protection and green development4,5,6,7. Biomass energy, a low-carbon, clean, and renewable resource derived from green plants converting solar energy into chemical energy, offers a promising alternative8,9,10. It encompasses solid materials such as wood and straw, liquid substances like biofuels, and gaseous forms like biogas10,11,12,13. Biomass combustion efficiency significantly affects emissions, with biomass pellets not emitting more metals than raw biomass14. Processes like biomass pyrolysis and gasification can reduce NOx and SO2 emissions, making biomass a sustainable option compared to fossil fuels15,16,17. China, with its vast straw resources, has the potential to utilize biomass energy more extensively, especially in tobacco curing, where biomass energy can save costs and reduce CO2 emissions while maintaining tobacco quality, thus becoming a focal point for clean energy development9,10,18,19. The various types of biomass energy and their respective effects on the curing process are detailed in Table 1.

With the continuous development of bulk curing barn equipment, the thermal efficiency of the curing barn system has improved, ranging from 14 kg of dry wood consumption to 4.5 kg wood fuel, and further to 1.2 kg of biomass briquettes for obtaining 1 kg of cured tobacco22,29,30. The efficiency of the bio-fuel system using tobacco stems briquetting ranges from 43.5% to 54.0%, whereas the efficiency of traditional fuel system with honeycomb briquette is 51.5%31. However, the combustion performance of biomass briquettes is equivalent to that of coal, with superior performance during the high-temperature solidification stage23. The energy efficiency of biomass briquettes is 39.0%–42.0%, which is higher than that of coal by 36.0%.

An automatic feeding, heating, and ash cleaning device for flue-cured tobacco curing based on a biomass briquette fuel burner has been developed using modern computer technology, which realizes the precise control of barn temperature and humidity24,32. At the beginning of this century, biomass pellet fuels developed rapidly in Europe, North America and other countries33,34. The application effect of a biomass pellet combustion furnace in the original bulk curing barn equipped with the corresponding heat exchanger is superior, followed by the direct docking of metal heating equipment, with the direct connection of non-metal heating equipment being less effective35. Compared to the bulk curing barn with coal-fired heating, biomass bulk curing barn offers significant energy savings, emission reduction, cost reduction, quality improvement and efficiency improvement, and has a promising prospect for popularization and application22,32,35. Additionally, different energy curing methods can affect the quality and style characteristics of cured tobacco leaves36.

Biomass energy plays an important role as an energy source in the tobacco leaf curing process 1,9,10,21. Currently, although extensive research has been conducted on the curing effect of energy curing barns such as solar energy, heat pumps, biomass, gas and alcohol-based fuels9,10,22,28,35, little attention has been given to the curing effect of different types of biomass combustion equipment bulk curing barns. In terms of biomass combustion equipment for bulk curing barns, there have been reports on the curing costs, CO2 emissions, system thermal efficiency, energy efficiency, and economic characteristics of the flue-cured tobacco leaves3,9,22,23,29,30,31. However, there is a lack of systematic evaluation of the curing effects of different types of biomass combustion equipment in bulk curing barns, especially in terms of pollutant emissions from the barns during the curing process and the intrinsic quality of the flue-cured tobacco leaves. In short, the optimal biomass combustion system for bulk curing barns was identified through a comparative analysis of various aspects, including curing performance, biomass combustion efficiency, pollutant emissions, curing expenses, economic characteristics, chemical composition, aroma content, and sensory evaluation of flue-cured tobacco leaves across different biomass-burning barns. Our work will enable evidence-based selection of biomass combustion technologies, promote sustainable agricultural practices, and accelerate the transition from experimental research to industrial adoption. This research aims to support the green production and sustainable growth of the agricultural and economic crops.

Materials and methods

Materials

The experiment was carried out in Maotian Curing Workshop, Maotian Town, Wuchuan County, Zunyi City, and the tested flue-cured tobacco variety was Yunyan 87, the main local flue-cured tobacco variety. A total of 825 hectares of flue-cured tobacco were planted in Maotian Town every year. The transplanting work was completed on April 25, 2024, according to the well-cellar transplanting technology, and the cultivation management was carried out according to the production regulations of high-quality tobacco leaves in Guizhou, with the upper tobacco leaves (the 16th to 17th leaf position, from bottom to top of the tobacco plant) with basically the same maturity and leaf size as the test materials.

Biomass pellet fuel represents an innovative, clean-burning energy source, crafted from agricultural and forestry by-products. It is produced through a series of processing steps including crushing, blending, extrusion, and dehydration, to make it ready for direct combustion. Offered by Chongqing New Energy Technology Co., Ltd., located in the Bishan District, Chongqing, this fuel has a moisture content of 2.55% and a low heating value of 17.29 MJ/kg, meeting the specifications required for the curing test. Biomass combustion conditions and control variables as follow: 6/8 mm diameter of biomass pellet, bulk density of formed fuel ≥ 600 kg/m³, low calorific value ≥ 12 MJ/kg, moisture content ≤ 12%, ash content ≤ 15%, ash fusion temperature ≥ 1100 °C, length of biomass pellet ≤ 4 times the diameter, breakage rate ≤ 2%.

Test treatment

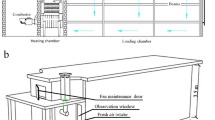

Five standard airflow descending bulk curing barns (a type of equipment used for curing tobacco leaves, characterized by the flow of hot air moving from top to bottom, which passes through the layers of tobacco leaves arranged inside the barn) with the same specifications (8.0 m × 2.7 m × 3.5 m, with a circulating fan 2.2 kW) were tested. These barns were seamlessly connected with biomass combustion equipment. The built-in biomass bulk curing barn refers to a heating device where biomass fuel from the storage box is pushed into the heating chamber of the bulk curing barn for combustion through means such as a screw conveyor. The external biomass bulk curing barn is a combustion device that uses biomass as fuel and burns it outside the heating chamber of the curing barn, with the heat being supplied to the furnace through a firing pipe. The biomass semi-gasification combustion heating furnace bulk curing barn is a type of curing barn that utilizes biomass energy for semi-gasification combustion to provide heat. The design of bulk curing barns with different types of biomass combustion equipment was as follows:

T1, a built-in biomass bulk curing barn combined with a heating chamber, featuring a special hearth for burning that supplies heat through a smoke pipe.

T2, an external biomass bulk curing barn combined with a heating chamber, equipped with a flame pipe connected to a smoke pipe.

T3, a biomass semi-gasification combustion heating furnace bulk curing barn with a built-in hearth, connected to a heating chamber.

T4, a heat supply and heat exchange integrated built-in biomass bulk curing barn type I, featuring a butt joint with the heating chamber, spiral feeding, and a U-shaped burning plate, where the feeding and burner are not separated.

T5, a heat supply and heat exchange integrated built-in biomass bulk curing barn type II, featuring a butt joint with the heating chamber, spiral feeding, and a V-shaped burning plate, where the feeding and burner are separated.

The bulk curing barn is arranged with tobacco in three distinct layers, each layer holding 120 rods of tobacco leaves, for a total of 360 rods per curing barn. Representative samples of tobacco leaves were hung in the lower, middle, and upper layers of each curing barn, positioned 2 m, 4 m, and 6 m from the door of the tobacco loading room, respectively. Each layer contained 6 rods, totaling 18 rods per curing barn, and across 5 biomass curing barns, there were a total of 90 rods. The curing schedule was carried out according to a flue-cured tobacco bulk curing process based on biomass energy in Guizhou. During the curing process, the temperature rise and stability of the bulk curing barn and the emission of pollutants were measured. After curing, the curing cost, economic traits and sensory quality of the cured tobacco leaves were evaluated, and the contents of conventional chemical components and aroma substances in the cured tobacco leaves were detected. All tests were repeated three times.

Measurement items and methods

Determination of the temperature-rise performance of bulk curing barn

The temperature-rise performance is expressed by the deviation between the actual dry-bulb temperature and the set dry-bulb temperature of the curing barn at different temperature-rise stages during the curing process of tobacco leaves, and 36℃–38℃, 38℃–40℃, 40℃–42℃, 42℃–45℃, 45℃–48℃, 48℃–54℃, 54℃–60℃ and 60℃–68℃ were taken as the key stages for the detection of the temperature -rise performance of the curing barn. The yellowing stage is 36℃–42℃, the color-fixing period is 42℃–54℃, and the stem-drying stage is 54℃–68℃. The set heating rate was set at 1℃ per 1–3 h and the difference between the actual dry bulb temperature and the set dry bulb temperature was recorded every 30 min for three consecutive times, and the average value was taken. If the deviation of dry bulb temperature is within ± 0.5℃, it is considered that the temperature -rise performance of the curing barn is good; if the deviation is within ±(0.5℃–1.0℃), it is considered that the temperature -rise performance of the curing barn is qualified; if the deviation is more than 1.0℃ or less than − 1.0℃, then it is regarded as unqualified.

Determination of stable temperature performance of bulk curing barn

The stable temperature performance is expressed by the deviation between the actual dry bulb temperature of the curing barn and the set dry bulb temperature at different stable temperature stages during the curing process of tobacco leaves, and 36℃, 38℃, 40℃, 42℃, 45℃, 48℃, 54℃, 60℃ and 68℃ during the curing process were taken as the key stable temperature points for detecting the stable temperature performance of the curing barn. The difference between the actual dry bulb temperature and the set dry bulb temperature of the curing barn was recorded every 30 min for three consecutive times, and the average value was taken. If the dry bulb temperature deviation is within ± 0.5℃, it is considered that the temperature stability performance of the curing barn is good; if the temperature deviation is within ± (0.5℃–1.0℃), it is considered that the temperature stability performance of the curing barn is qualified; if the deviation is more than 1.0℃ or less than − 1.0℃, it will be regarded as that the stability of the drying barn is not qualified.

Determination of biomass combustion efficiency and pollutant emissions from the bulk curing barn

The determination of biomass combustion efficiency and pollutant emissions from the curing barn was carried out at the dry-bulb temperature stabilization points of 36℃, 38℃, 40℃, 42℃, 45℃, 48℃, 54℃, 60℃ and 68℃ during the curing process, respectively. It is important to point out that biomass combustion efficiency refers to the efficiency of converting biomass fuel into thermal energy during the combustion process; that is, what proportion of the energy contained in the fuel is effectively utilized and converted into heat energy. It is usually expressed as a percentage, and the calculation formula is as follows: Combustion efficiency (%) = (Actual heat released / Theoretical heat released by complete combustion of the fuel) × 100%. Select the middle plane of the chimney for detection, the flue area was 0.04 m2, each point is measured 3 times, and the average value was taken. According to the Air Pollutant Emission Standards (GB16297–1996), Laoying 3012 H automatic smoke and dust gas tester (YQX–107) was used to detect biomass combustion efficiency, smoke and dust particles, as well as the concentration of pollutant gases SO2, CO, and NOx using electrochemical sensors. Among them, isokinetic sampling and gravimetric analysis are used for the determination of soot particles, and the fixed-point electrolysis method is used for the determination of SO2, CO, and NOx emissions. In these methods, isokinetic sampling combined with gravimetric analysis is employed for the measurement of soot particles, in accordance with China’s National Standard HJ836–2017. Additionally, the fixed-point electrolysis technique is utilized for the quantification of emissions such as SO2, following China’s National Standard HJ57–2017, CO adhering to China’s National Standard HJ973–2018, and NOx in line with China’s National Standard HJ693–2014.

Curing cost analysis

The biomass consumption, power consumption and labor consumption of different types of biomass burning equipment bulk curing barns were counted, and the curing cost reported as CNY· kg⁻¹ (dry tobacco) of different types of biomass burning equipment bulk curing barns was analyzed. Hereafter, curing cost is on a tobacco dry-weight basis (CNY·kg⁻¹)

Evaluation of economic traits of tobacco leaves

According to the national standard GB 2635 − 1992 “Flue-cured Tobacco” grading standard, the grade structure of flue-cured tobacco leaves was evaluated. The orange tobacco rate, superior tobacco rate, middle-class tobacco rate, and average price were counted.

Determination of chemical components of tobacco leaves

The cured C3F tobacco leaf samples were dried at 45℃, crushed, and sieved through a 60-mesh sieve. The contents of water-soluble total sugar, reducing sugar, nicotine, potassium, and chlorine were detected using an AUTOAnalyer 3 continuous flow analyzer, and the total nitrogen content was detected by a Furura II continuous flow analyzer (YC/T 159–162–2002, YC∕T 217–2007). The starch and protein content of tobacco leaves was determined using the Tobacco and Tobacco Products-Determination of Starch-Continuous Flow Method (YC/T 216–2007, YC/T 216–2013). The harmony of the chemical composition was assessed based on the ratios of total nitrogen to nicotine, reducing sugar to nicotine, reducing sugar to total sugar, and the potassium-to-chlorine ratio, respectively.

Determination of aroma substances in tobacco leaves

The content of aroma substances in C3F tobacco leaves, subjected to different treatments, was determined using a combination of distillation and extraction followed by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) with a 7890B/5977B GC-MS system. The obtained chromatograms was qualitatively analyzed using the computer atlas library (NIST14). The relative content of aroma components in tobacco leaves was calculated by internal standard method.

The detailed chromatographic conditions are as follows: HP-5MS (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm) capillary column; carrier gas helium with a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min; injection temperature of 260℃; injection volume of 1 µL, split injection with a split ratio of 20:1; programmed temperature rise: the initial temperature was maintained at 50℃ for 1 min, then increased from 50℃ to 160℃ at the rate of 8℃/min, held for 2 min, followed by an increase from 160℃ to 280℃ at a rate of 8℃/min, held for 15 min. The total run time was 45 min. MS conditions: solvent delay of 3 min; ionization voltage of 70 eV; ion source temperature of 230℃; transmission line temperature of 280℃; ion scanning range from 35 to 450 amu; MS scanning mode: SCAN. Forty-eight kinds of aroma substances were detected and classified into 7 groups: carotenoid degradation products (including linalool, etc., total of 14), chlorophyll degradation products (neophytadiene), Maillard reaction products (including hexanal, etc., total of 15), aromatic amino acid degradation products (including benzyl alcohol, etc., total of 5). Each category was counted separately.

Evaluation of sensory quality of tobacco leaves

The sensory quality of tobacco leaves was assessed by seven domestic smoking experts, following the sensory evaluation method for tobacco and tobacco products (YC/T 138–1998). Thirty pieces of C3F tobacco leaves, subjected to different treatments, were evaluated for smoking evaluation quality based on the fundamental requirements for the smoking evaluation of single-material tobacco. The higher the score, the better the curing quality of the tobacco leaves was deemed, with evaluations conducted across various aspects including aroma quality, aroma quantity, offensive taste, irritancy, aftertaste, combustibility, smoke softness, taste, and ash color. The scoring is as follows: 18 points for aroma quality and impurity quantity, 12 points for aroma quantity and irritancy, 10 points for aftertaste and mouthfeel, 8 points for smoke softness and combustibility, 4 points for ash content, with a total possible score of 100. The evaluation of industrial usability is categorized into four grades: good (A), better (B), general (C), and poor (D). The formula suitability evaluation is divided into five grades: good (I), better (II), general (III), poor (IV), and worse (V).

Data analysis

The data collected from the experimental study on the various biomass combustion equipment for curing tobacco leaves were processed and analyzed using a combination of Microsoft Excel 2021 and SPSS version 18.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). To ascertain the significance of the differences observed among the treatments, a one-way ANOVA with Duncan’s multiple range test was employed, with a significance level set at 5%.

Results

Temperature -rise performance of bulk curing barn

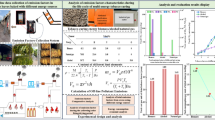

The heating performance of curing barn is closely related to the dry bulb temperature of flue-cured tobacco, and the appearance characteristics of flue-cured tobacco under different treatments showed some differences (Fig. 1). The variation of dry bulb temperature of flue-cured tobacco under different combustion conditions was investigated to clarify the temperature -rise performance of different types of biomass combustion equipment in bulk curing barns (Table 2). The deviation of dry bulb temperature during the yellowing stage (± 0.4℃) was small, whereas it was large during the color-fixing stage (± 0.8℃) and the stem-drying stage (± 0.9℃) in the heating process. The maximum and minimum deviation values of dry bulb temperature at different heating stages for various treatments were significantly different. The order of dry bulb temperature deviation across the heating stages for different treatments was: T4 > T5 > T3 > T1 > T2. The results showed that the T4 and T5 treatments had good temperature -rise performance, with the smaller temperature deviation of (± 0.3℃) and (± 0.4℃), respectively.

Temperature stability of bulk curing barn

The effects of different types of biomass combustion equipment on the temperature stability of the bulk curing barn were evaluated. The deviations of the dry bulb temperature during the temperature stabilization stage of the yellowing stage (± 0.5℃) were small, whereas the deviations of the dry bulb temperature during the temperature stabilization stage of the color-fixing period (± 0.7℃) and the stem-drying stage (± 0.6℃) were large. The maximum and minimum deviation values of different treatments at various temperature stabilization stages were significantly different (Table 3). The order of dry-bulb temperature deviation among different treatments was T4 > T5 > T2 > T1 > T3. The results indicated that the temperature stability of the T4, T5, and T2 treatments was good, with the smaller temperature deviation of (± 0.4℃), (± 0.5℃) and (± 0.5℃), respectively.

Biomass combustion efficiency and pollutant emission of bulk curing barn

Green and low carbon is an important environmental evaluation index in the development of tobacco industry. We assessed the biomass combustion efficiency and pollutant emissions during the curing process in bulk curing barns equipped with different types of biomass combustion equipment (Table 4). Excluding individual measurements with particularly large errors, the order of biomass combustion efficiency at different dry bulb temperature stable points and across different treatments in the curing process was essentially as follows: T4 > T5 > T3 > T1 > T2. The biomass combustion efficiency of the T4 treatment during curing ranged from 90.16% to 99.69%, while that of the T5 treatment ranged from 90.32% to 99.17%. Both were much higher than the efficiency of the T2 treatment, which ranged from 80.39% to 94.63%. The order of average concentration of dust particles, SO2, NOX, and CO was T2 > T1 > T3 > T5 > T4, and there were significant differences in the maximum and minimum values of different dry-bulb temperatures under various treatments. Among them, the average emission concentrations of dust particles, SO2, NOX, and CO during the curing process for T2 treatment were 27.06 mg/m³, 22.80 mg/m³, 264.72 mg/m³, and 0.13 mg/m³, respectively; for T4 treatment, they were 20.20 mg/m³, 17.61 mg/m³, 210.08 mg/m³, and 0.04 mg/m³, respectively; and for T5 treatment, they were 22.33 mg/m³, 18.15 mg/m³, 213.56 mg/m³, and 0.05 mg/m³, respectively. Compared to the T2 treatment, the T4 and T5 treatments reduced pollutant emissions by an average of 26.94% and 23.86%, respectively, during the curing process. Biomass combustion efficiency, as well as particulate matter, SO2, and NOX concentrations, showed an increasing trend (peaking at 48℃ or 54℃) during the yellowing stage and color-fixing period, with a slight decrease in the early stem-drying stage, followed by another increasing trend. However, the CO concentration in different treatments exhibited an increasing trend during the yellowing stage, reaching its peak at 45 °C during the color-fixing period, and subsequently showed a gradual decline. The results revealed that the parameters for biomass combustion efficiency and emission amounts of dust particles, SO2, NOX, and CO pollutants in different types of bulk curing barns exhibited a trend of “increase-decrease-increase”, with the average values (87.75%, 18.13 mg/m³, 15.53 mg/m³, 201.92 mg/m³, 0.06 mg/m³) being the smaller during the yellowing stage and the larger (95.57%, 30.34 mg/m³, 25.69 mg/m³, 255.98 mg/m³, 0.10 mg/m³) during the color-fixing period. The T4 and T5 treatments were superior to other treatments in terms of biomass combustion efficiency and pollutant emissions, offering significant advantages in fuel savings and environmental protection.

Curing cost analysis

Cost control is an important economic indicator that must be concerned in the development of the flue-cured tobacco industry. We systematically analyzed the curing cost of different types of biomass burning equipment bulk curing barns (Table 5). The biomass consumption of the T2 treatment was significantly higher than that of the other treatments, while the T3 treatment was significantly higher than that of the T1, T4, and T5 treatments. The power consumption of the T2 treatment was the highest, significantly higher than that of the T4 treatment, with no significant difference observed among the other treatments. The Labor consumption in the T4 and T5 treatments was significantly higher than the other treatments. The curing cost of the T2 treatment was significantly higher than the other four treatments. Meanwhile, the curing cost of the T1 and T3 treatments was significantly higher than that of the T4 and T5 treatments. Compared with the T2, the T4 and T5 reduced curing costs by 0.51 and 0.45 CNY·kg⁻¹, respectively. Overall, the T4 and T5 treatments had a lower curing cost for biomass burning equipment in bulk curing barns.

Economic characters of tobacco leaves

The economic properties of flue-cured tobacco leaves using different types of biomass burning equipment in bulk curing barns were shown in Table 6. The order of orange tobacco leaf rate, superior tobacco leaf rate, and average price for each treatment was T4 > T2 > T5 > T1 > T3. The orange tobacco leaf rate in the T4 treatment was significantly higher than that in the T1, T3, and T5 treatments, while the T2 treatment had a significantly higher rate than the T3 treatment. The superior tobacco leaf rate in the T4 treatment was significantly higher than that in the T1 and T3 treatments. The middle class tobacco leaf rate was highest in the T4 treatment, significantly exceeding that in the T3 treatment, with no significant difference observed among the other treatments. The average price of the T4 treatment was significantly higher than that of the other treatments, whereas the T3 treatment had the lowest average price. Compared with the T3 treatment, the average price of the T4 treatment increased by 5.76 CNY·kg-1. Overall, the T4 treatment was the most favorable, followed by the T2 and T5 treatments, with the T1 and T3 treatments being the least favorable (Table 6).

Chemical composition of tobacco leaves

Understanding the chemical composition of flue-cured tobacco leaves is helpful for fully evaluating the quality traits of flue-cured tobacco. We evaluated the changes of chemical components of flue-cured tobacco leaves in different types of biomass burning equipment bulk curing barns (Table 7). The nicotine content in the T1 treatment was significantly higher than that in the other treatments. The T1 and T3 treatments had significantly higher than that in the T2 and T5 treatments, and the T2 treatment had a significantly higher than that in the T5 treatment. There is no significant difference in total sugar and chlorine content among the different treatments. The reducing sugar content in the T4 treatment was significantly higher than that in the T2 and T3 treatments. The total nitrogen content in the T1 treatment was significantly higher than that in the other treatments, with no significant difference observed among the remaining treatments. The starch content in the T3 treatment was significantly higher than that in the T2, T4, and T5 treatments, and the starch content in the T1 treatment was significantly higher than that in the T4 and T5 treatments. The protein content in the T4 treatment was significantly lower than that in the other treatments. Potassium content in the T4 treatment was significantly higher than that in the T2, T3 and T5 treatments, and the potassium content in the T1 and T2 treatments was significantly higher than that in the T3 treatment. From the perspective of the ratio between nitrogen and nicotine (total nitrogen/nicotine), both the T4 and T5 treatments fell within the suitable range of 0.8–0.9. The ratio of sugar to nicotine (reducing sugar/nicotine) in the T4 treatment was the best, at 9.87 (generally, a ratio of 6–10 is desired, with closer to 10 being better). The ratio of reducing sugar to total sugar, which is generally considered better when higher, ranged from 0 to 1. In the T4 and T5 treatments, this ratio was greater than or equal to 0.7. Additionally, the ratio of potassium to chlorine, which is generally believed to be optimal when greater than 4, was greater than 5 in these treatments, indicating a more appropriate balance. In general, the chemical components of flue-cured tobacco leaves in the T4 and T5 treatments were relatively well-coordinated, with the T4 treatment being the best.

Aroma substances in tobacco leaves

As shown in Table 8, the content of carotenoid degradation products in the T4 treatment was significantly higher than that in the T1, T3, and T5 treatments, while the content in the T2 treatment was significantly higher than that in the T3 treatment. The content of chlorophyll degradation products in the T4 treatment was the highest, which was significantly higher than that in the T2 treatment, but no significant differences were observed among the other different treatments. The content of Maillard reaction products in the T4 treatment was significantly higher than that in the other treatments, and in the T5 treatment, it was significantly higher than that in the T1 and T3 treatments. The content of aromatic amino acid degradation products in the T4 treatment was significantly higher than that in the T1 and T3 treatments. The T5 treatment had a significantly higher content of cembranoids degradation products compared to the T1, T2, and T3 treatments, while the T4 treatment had a significantly higher content than the T1 and T3 treatments. The content of fatty acids in the T4 treatment was significantly higher than that in the other treatments, and in the T5 treatment, it was significantly higher than that in the T1 and T3 treatments. Considering the above factors, the contents of aroma components in flue-cured tobacco leaves under the T4 and T5 treatments were relatively higher, with the T4 treatment having the highest content among them.

Sensory quality of tobacco leaves

The sensory quality of tobacco leaves is a crucial aspect of flue-cured tobacco. We systematically evaluated the sensory quality of flue-cured tobacco leaves in bulk curing barns using different types of biomass burning equipment (Table 9). The T4 treatment achieved the highest scores in aroma quality, irritancy, combustibility, and ash color, significantly outperforming the other treatments in these categories. For aroma quantity, the T4 treatment scored significantly higher than the other treatments, while the T5 treatment scored significantly higher than the T1 and T3 treatments. In terms of offensive taste, the T4 treatment had the highest score, significantly higher than that of the T1 treatment. For aftertaste, the T2, T4, and T5 treatments scored significantly higher than the T1 and T3 treatments. The T4 treatment also achieved the highest taste score, significantly higher than that of the T1, T3, and T5 treatments. Regarding smoke softness, the T2 and T4 treatments received the highest scores, significantly outperforming the T3 treatment. In terms of industrial availability, the T4 treatment was the best, and the T4 and T5 treatments were most suitable for formulation. The T4 treatment had the highest total score, significantly surpassing the other treatments, followed by the T5 and T2 treatments, with the T1 and T3 treatments scoring the lowest. The sensory quality of flue-cured tobacco leaves under the T4 treatment was the best, followed by the T5 and T2 treatments.

Discussion

The performance of biomass combustion equipment affects the normal operation and the curing performance of bulk curing barn32,35. Biomass moulding fuel, including biomass briquette fuel and biomass pellet fuel, the bulk curing barn using biomass moulding fuel significantly outperforms coal in terms of performance24,25. For the heating equipment using alcohol-based fuel, the accuracy of the target dry bulb temperature curve reached 93.4%28. Our results showed that the dry bulb temperature deviation of different types of biomass burning equipment bulk curing barns was small in the heating stage and the stable temperature stage during the yellowing stage (± 0.4℃, ± 0.5℃), but large during the color-fixing period (± 0.8℃, ± 0.7℃) and the stem-drying stage (± 0.9℃, ± 0.6℃). The T4 and T5 treatments demonstrated good performance in terms of curing temperature rise and stable temperature maintenance. Additionally, the T4 treatment exhibited the smallest deviation in curing temperature rise (± 0.3℃) and stable temperature maintenance (± 0.4℃) of dry bulb temperature and the best curing performance. Compared with the external biomass bulk curing barn, the built-in biomass bulk curing barn had better heating performance, and the temperature stability of different types of bulk curing barns had no obvious regularity. From the perspective of the curing performance of bulk curing barn, the built-in biomass bulk curing barn is one of the best choices for bulk curing at present and for some time in the future.

The comprehensive thermal efficiency and energy efficiency of biomass-fired bulk curing barns for curing is higher than that of coal-fired bulk curing barns3,23. Moreover, thermal efficiency of alcohol‑based fuel was higher than coal and biomass briquettes fuel28. Our research indicated that the order of biomass combustion efficiency at different dry-bulb temperature stable points was T4 > T5 > T3 > T1 > T2, suggesting that the T4 treatment (90.16%–99.69%) and the T5 treatment (90.32%–99.17%) had the highest efficiency, compared to the T2 treatment (80.39%–94.63%), which was the least efficient during the curing process. In addition, the results showed that the biomass combustion efficiency in various types of bulk curing barns showed an “increase-decrease-increase” trend, in which the biomass combustion efficiency was lower at 36℃ with an average value of 86.70% during the yellowing stage, and was higher at 54℃ with an average value of 98.03% during the color-fixing period. Furthermore, there are some differences in different experimental designs in the study of comprehensive thermal efficiency of biomass bulk curing barn, which needs to be further explored and analyzed3,32.

Nowadays, the global ecological and environmental problems are still prominent. The research, development and application of new biomass energy equipment and technology is an important way to solve the existing ecological and environmental problems, and an important prerequisite for achieving the goal of “carbon peak and carbon neutrality” in low-carbon economic development37,38,39,40. The results indicated that the emission parameters of pollutants in various types of bulk curing barns also showed an “increase-decrease-increase” trend, in which the dust particles, SO2, NOX and CO concentrations were lower at 36℃ during the yellowing stage, with average values of 15.87 mg/m3, 13.26 mg/m3, 161.06 mg/m3, 0.01 mg/m3, respectively. In contrast, they were higher at 54℃, 54℃, 48℃, 45℃ during the color-fixing period, with average values of 34.64 mg/m³, 30.00 mg/m³, 272.34 mg/m³, and 0.12 mg/m³, respectively. This is closely related to the composition of biomass fuel and the execution of the curing process, suggesting that the color-fixing period is the key stage for reducing pollutant emissions and achieving low-carbon clean curing in the future3,41.

Compared with coal and other non-renewable energies, the application of biomass renewable energy sources (such as biomass briquette fuel, biomass pellet fuel, alcohol‑based fuel, biogas) can effectively reduce the emission of CO, NO, NO2, SO2 and H2S air pollutants10,21,22,25,28. It is worth noting that the emission amounts of dust particles, SO2, NOX and CO at different dry bulb temperature stable set points during the curing process were basically in the order of T2 > T1 > T3 > T5 > T4, indicating that the T4 and T5 treatments had the lowest emissions of pollutants in the built-in biomass bulk curing barn with integrated heat supply and heat exchange. The average emission concentrations of dust particles, SO2, NOX, and CO during the curing process for T4 treatment were 20.20 mg/m³, 17.61 mg/m³, 210.08 mg/m³, and 0.04 mg/m³, respectively; and for T5 treatment, they were 22.33 mg/m³, 18.15 mg/m³, 213.56 mg/m³, and 0.05 mg/m³, respectively. Compared with the external biomass bulk curing barn in the T2 treatment, the emissions of pollutants from the T4 and T5 treatments in the built-in biomass bulk curing barn were reduced by an average of 26.94% and 23.86%, respectively, during the curing period. In general, the T4 and T5 treatments excelled over other treatments in terms of pollutant emissions, and providing great advantages in energy conservation and environmental protection. The consumption of non-renewable energy is the fundamental cause of ecological and environmental problems, and the produced SO2 and NOX are the main air pollutants in China4,5. Notably, the average emission concentration of SO2 was higher during the color-fixing period, while NOX was higher during both the color-fixing period and the stem-drying stage. Moreover, the SO2 and NOX emissions of pollutants from the T4 and T5 treatments in the built-in biomass bulk curing barn were significantly lower than those of the external biomass bulk curing barn in the T2 treatment. These suggested that the T4 and T5 treatments were more beneficial for reducing pollutant emissions, with the color-fixing period and the stem-drying stage being the key monitoring periods.

Biomass energy is a renewable energy source with abundant reserves, and the biomass automatic feeding device, along with other automatic configurations significantly reduces labor and costs, while improving the quality and increasing efficiency of tobacco curing in the biomass bulk curing barn22,24,32. The biomass with the lowest consumption was pellets, followed by firewood and sawdust26,27; the drying costs of biomass briquette fuel and biomass pellet fuel were reduced by 19.80% and 15.90% respectively compared to coal25. Our results showed that T4 treatment had the lowest curing cost, followed by the T5 treatment, with the T2 treatment having the highest cost. Compared with the T2 treatment, the T4 and T5 treatments reduced curing costs by 0.51 and 0.45 CNY·kg-1, respectively. This indicates that the built-in biomass bulk curing barn is significantly more cost-effective than the external biomass bulk curing barn. Additionally, the economic properties of flue-cured tobacco leaves were best in the T4 treatment, followed by the T2 and T5 treatments, whereas the T3 treatment had the worst economic properties. Compared with the T3 treatment, the average price of the T4 treatment increased by 5.76 CNY··kg-1. These results indicated that the economic properties of flue-cured tobacco leaves cured in the built-in biomass bulk curing barn were significantly superior to those cured in the external biomass bulk curing barn.

The internal quality of flue-cured tobacco leaves is closely related to the combustion equipment and energy type of bulk curing barns24,30,32. Our research shows that the chemical composition of flue-cured tobacco leaves in the T4 and T5 treatments using different types of biomass burning equipment in bulk curing barns was relatively more coordinated. In terms of the content of aroma substances in flue-cured tobacco leaves, the T4 and T5 treatments had relatively higher contents, while the T4 treatment scored the highest in sensory quality evaluation, followed by the T5 and T2 treatments. This indicates that the sensory quality of flue-cured tobacco leaves cured in the built-in biomass bulk curing barn was superior. Based on the comprehensive evaluation of the coordination of chemical components, the content of aroma substances, and the sensory quality of flue-cured tobacco leaves, the T4 treatment ranked the highest, followed by the T5 treatment. This may be closely related to the T4 and T5 treatments in the built-in biomass bulk curing barn, which are characterized by more precise feeding, complete fuel combustion, precise temperature control, and stable temperature maintenance3,24,25.

The choice of energy for tobacco curing in different countries and regions depends on the availability, cost and relative efficiency of local energy raw materials3,21,41. According to the current situation in our country and the development trend of curing energy, the popularization and application of biomass curing barns should comprehensively consider factors such as fuel costs and supporting facilities3,9,10. According to the differences of curing performance, biomass combustion efficiency, pollutant emissions, curing cost, economic traits, chemical composition content, aroma content and sensory quality of cured tobacco leaves among different types of biomass combustion barns, the T4 treatment, which involves a built-in biomass curing barn with integrated heat supply and heat exchange integration, was classified as type I (docking with the heating chamber and spiral feeding). However, the number of ash cleanings required by the burner was higher than that for the other two treatments. The overall curing effect of the T5 treatment was slightly inferior to that of the T4 treatment in the biomass bulk curing barn with a built-in heat supply and heat exchange system (type II), which is connected to the heating chamber with spiral feeding and is separated from the burner (type V). This work is similar to what has been previously reported35. The built-in biomass bulk curing barn, which uses biomass pellets as fuel, adopts fuzzy control technology, PID control technology, secondary combustion technology, and four-stage air distribution technology22,24,25,28. This significantly improves the precision of bulk curing barn control, solving the problems of time-varying and lagging temperature control in coal-fired bulk curing barns. Therefore, the overall application effect of the built-in biomass bulk curing barn with integrated heating and heat exchange was superior, making it one of the key types to replace the coal-fired bulk curing barn. Consequently, it should be promoted and applied in tobacco-growing areas where biomass fuel raw materials are both inexpensive and abundant, and where comprehensive supporting facilities are in place.

Conclusion

Our results indicated that the T4 and T5 treatments exhibited good curing temperature -rise performance and stable temperature performance. Notably, the T4 treatment had the smallest dry bulb temperature deviation and the best curing performance. Throughout the curing process, the efficiency of biomass combustion and pollutant emissions exhibited a trend of “increase-decrease-increase” with the lowest values observed at 36℃ during the yellowing stage and the highest at either 45℃, 48℃, or 54℃ during the color-fixing stage. The built-in biomass bulk curing barn (T4 and T5 treatments), equipped with an integrated heating and heat exchange system, demonstrated superior curing performance and biomass combustion efficiency, as well as reduced curing costs compared to other methods. It also resulted in decreased pollutant emissions during the curing process. The tobacco leaves cured in this barn showed improved economic characteristics, better chemical composition coordination, enhanced sensory quality, and a higher content of aromatic substances. In contrast, the external biomass bulk curing barn (T2 treatment), which used a flamethrower for heat supply, was less effective. Essentially, the built-in biomass bulk curing barn with its integrated heating and heat exchange system achieved favorable curing outcomes and is suitable for widespread adoption in tobacco-growing regions where biomass fuel raw materials are abundant and affordable, and where comprehensive supporting facilities are available. This system lays a crucial foundation for the low-carbon and clean curing of biomass.

Data availability

The author confirms that all data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article. Furthermore, primary and secondary sources and data supporting the findings of this study were all publicly available at the time of submission.

References

Wu, S. J. et al. Advancements in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L.) seed oils for biodiesel production. Front. Chem. 9 https://doi.org/10.3389/fchem.2021.834936 (2021).

Torres Castillo, N. E. et al. Enzyme mimics in-focus: redefining the catalytic attributes of artificial enzymes for renewable energy production. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 179, 80–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.03.002 (2021).

Wang, J. et al. Integrated furnace for combustion/gasification of biomass fuel for tobacco curing. Waste Biomass Valoriz. 10, 2037–2044. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12649-018-0205-1 (2019).

Meng, Q. C. et al. Collaborative emission reduction model based on multi-objective optimization for greenhouse gases and air pollutants. PloS One. 11, e0152057. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0152057 (2016).

Du, K. et al. Integrated lipid production, CO2 fixation, and removal of SO2 and NO from simulated flue gas by oleaginous Chlorella pyrenoidosa. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. Int. 26, 16195–16209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-019-04983-9 (2019).

Hou, H. & Yang, S. Clean energy, economic development and healthy energy intensity: an empirical analysis based on China’s inter-provincial panel data. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. Int. 29, 80366–80382. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-022-21322-7 (2022).

Zhu, X. et al. Life-cycle assessment of pyrolysis processes for sustainable production of biochar from agro-residues. Bioresour. Technol. 360, 127601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2022.127601 (2022).

Gonzalez, J. et al. Combustion optimisation of biomass residue pellets for domestic heating with a mural boiler. Biomass Bioenergy - BIOMASS BIOENERG. 27, 145–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biombioe.2004.01.004 (2004).

Bortolini, M. et al. Greening the tobacco flue-curing process using biomass energy: a feasibility study for the flue-cured Virginia type in Italy. Int. J. Green Energy. 16, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/15435075.2019.1671397 (2019).

Wu, S. J. et al. Change of times and development trend of Flue-cured tobacco curing energy. J. Jiangxi Agric. 34, 134–142. https://doi.org/10.19386/j.cnki.jxnyxb.2022.01.019 (2022).

Hu, B. B. & Zhu, M. Reconstitution of cellulosome: research progress and its application in biorefinery. Biotechnol. Appl. Chem. 66 https://doi.org/10.1002/bab.1804 (2019).

Gairola, S. et al. Thermal stability of extracted lignin from novel millet husk crop residue. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 242, 124725. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.124725 (2023).

Sanni, A. et al. Sustainability analysis of bioethanol production from grain and tuber starchy feedstocks. Sci. Rep. 12, 20971. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-24854-7 (2022).

Zhang, W. et al. Emission of metals from pelletized and uncompressed biomass fuels combustion in rural household stoves in China. Sci. Rep. 4, 5611. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep05611 (2014).

Pisupati, S. & Bhalla, S. Influence of calcium content of biomass-based materials on simultaneous NOX and SO2 reduction. Environ. Sci. Technol. 42, 2509–2514. https://doi.org/10.1021/es0719430 (2008).

Grisan, S. et al. Alternative use of tobacco as a sustainable crop for seed oil, biofuel, and biomass. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 36 https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-016-0395-5 (2016).

Molino, A. et al. Biomass gasification technology: the state of the art overview. J. Energy Chem. 25, 10–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jechem.2015.11.005 (2016).

Antoni, D. et al. Biofuels from microbes. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 77, 23–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-007-1163-x (2007).

Liu, M. et al. Driving and influencing factors of biomass energy utilization from the perspective of farmers. Int. J. Heat Technol. 39, 269–274. https://doi.org/10.18280/ijht.390130 (2021).

Siddiqui, K. M. & Rajabu, H. Energy efficiency in current tobacco-curing practice in Tanzania and its consequences. Energy 21, 141–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/0360-5442(95)00090-9 (1996).

Tippayawong, N. et al. Use of rice husk and corncob as renewable energy sources for tobacco-curing. Energy. Sustain. Dev. 10, 68–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0973-0826(08)60546-3 (2006).

Ren, T. et al. Application of biomass moulding fuel to automatic flue-cured tobacco furnaces: efficiency and cost-effectiveness. Therm. Sci. 23, 156–156. https://doi.org/10.2298/TSCI181202156R (2019).

Xiao, X. et al. Industrial experiments of biomass briquettes as fuels for bulk curing barns. Int. J. Green Energy. 12, 1061–1065. https://doi.org/10.1080/15435075.2014.891119 (2015).

Song, Z. et al. Application of automatic control furnace for combustion of biomass briquette fuel for tobacco curing. Therm. Sci. 25, 148–148. https://doi.org/10.2298/TSCI191115148S (2020).

Ren, T. et al. Biomass moulding fuel for zero-emission agricultural waste management: A case study of tobacco curing in China. J. Environ. Manage. 377, 124612. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2025.124612 (2025).

Dessbesell, L. et al. Complementing firewood with alternative energy sources in Rio Pardo watershed, Brazil. Ciência Rural. 47 https://doi.org/10.1590/0103-8478cr20151216(2017).

Welter, C. A. et al. Consumption and characterization of forestry biomass used in tobacco cure process. FLORAM. 26, e20180438 https://doi.org/10.1590/2179-8087.043818 (2019).

Ren, K. et al. Assessing the thermal efficiency and emission reduction potential of alcohol-based fuel curing equipment in tobacco-curing. Sci. Rep. 13, 13301. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-40015-w (2023).

Siddiqui, K. M. Analysis of a Malakisi barn used for tobacco curing in East and Southern Africa. Energy. Conv. Manag. 42, 483–490. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0196-8904(00)00066-2 (2001).

Munanga, W. et al. Development of a low cost and energy efficient tobacco curing barn in Zimbabwe. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 12, 2704–2712. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJAR2017.12413 (2017).

Wang X F, et al. Application of tobacco stems briquetting in tobacco flue-curing in rural area of China. Int J Agric & Biol Eng. 8(6), 84–88 https://doi: 10.3965/j.ijabe.20150806.1842(2015).

He, F. et al. Performance of an intelligent biomass fuel burner as an alternative to coal-fired heating for tobacco curing. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 30, 131–140. https://doi.org/10.15244/pjoes/122164 (2020).

Purohit, P. et al. Energetics of coal substitution by briquettes of agricultural residues. Energy 31, 1321–1331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2005.06.004 (2006).

Loo, S. & Koppejan, J. The Handbook of Biomass Combustion & Co-Firing. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781849773041 (2012).

Jiang, D. Z. et al. Application of biomass pellet burner in bulk curing barn. J. Agron. 7, 82–86 https://doi: 10.11923/j.issn.2095-4050.cjas17020009(2017).

Chen, J. et al. Influences of different curing methods on chemical compositions in different types of tobaccos. Ind. Crops Prod. 167, 113534. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2021.113534 (2021).

Hussain, M. et al. Greenhouse gas emissions from production chain of a cigarette manufacturing industry in Pakistan. Environ. Res. 134, 81–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2014.06.015 (2014).

Wang, H. et al. Research on sulfur oxides and nitric oxides released from coal-fired flue gas and vehicle exhaust: a bibliometric analysis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 26, 17821–17833. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-019-05066-5 (2019).

Jin, D. S. et al. Simultaneous removal of SO2 and NO by wet scrubbing using aqueous chlorine dioxide solution. J. Hazard. Mater. 135, 412–417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2005.12.001 (2006).

Chu, H. et al. Simultaneous absorption of SO2 and NO from flue gas with KMnO4/NaOH solutions. Sci. Total Environ. 275, 127–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0048-9697(00)00860-3 (2001).

Lee, K. et al. Manage and mitigate punitive regulatory measures, enhance the corporate image, influence public policy’: industry efforts to shape Understanding of tobacco-attributable deforestation. Globalization Health. 12, 55. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-016-0192-6 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Yonggao Tu, Kesu Wei, Delun Li, and Jun Jiang for their assistance in sample collection and laboratory experiment.

Funding

This work was supported by the Science and Technology Program of Science and Technology Department of Guizhou Province (QKHJC-ZK[2022]YB288); the Science and Technology Project of Guizhou Provincial Company, CNTC (2023XM22, 201717); the Science and Technology Project of Zunyi City of Guizhou Provincial Tobacco Company (2023XM06); the Natural science fund project of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (2022D01A10); the Tianjin Municipal Education Commission Scientific Research Plan Project (2021KJ106); the Science and Technology Project of Henan Provincial Company, CNTC (2018410000270097); the Science and Technology Project of Bijie City of Guizhou Provincial Tobacco Company (2021520500240228); and the Science and Technology Project of Guizhou Academy of Tobacco Science (GZYKY2022-02).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.S., J.M. and G.C. conceptualized and designed the research; S.W., C.S. and Q.X carried out the experiments; Y.L., X.J., and J.W. collected the samples; J.G., C.Z. and S.J. analyzed the data; S.W., J.M. and G.C. wrote and edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, S., Xu, Q., Gou, J. et al. Analysis of curing effect of bulk curing barns with different types of biomass combustion equipment. Sci Rep 15, 40908 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98971-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98971-4