Abstract

Stroke is a leading cause of global morbidity and mortality, with risk factors like visceral adiposity and inflammation playing significant roles. This study introduces the Visceral Adiposity Inflammatory Index (VAII), combining the Visceral Adiposity Index (VAI) and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (CRP), to better predict stroke risk. Analyzing data from 8415 participants in the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study over 9 years, the study found that higher VAII levels were strongly associated with increased stroke incidence, with a hazard ratio of 1.91 for the highest quartile. VAII outperformed VAI and CRP alone in predictive accuracy, enhancing traditional risk models as shown by improved Net Reclassification Index and Integrated Discrimination Improvement Index. Furthermore, blood pressure and the triglyceride-glucose index were identified as mediators in the VAII-stroke relationship. These findings underscore VAII as a promising tool for stroke risk assessment, suggesting that public health interventions targeting VAII reduction could help mitigate stroke risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Stroke represents a critical public health challenge, accounting for a substantial burden of morbidity and mortality globally1,2. Despite advances in understanding its pathophysiology, effective prevention strategies remain a critical challenge. Identifying novel and modifiable risk factors for stroke is essential to improve early detection, risk stratification, and intervention3,4.

Visceral adiposity, characterized by an excessive accumulation of visceral fat, is recognized as a pivotal contributor to metabolic dysregulation and systemic inflammation, both of which are established precursors to stroke5,6,7. The Visceral Adiposity Index (VAI), a widely recognized surrogate marker for visceral fat dysfunction, and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (CRP), a robust indicator of systemic inflammation, likely interact through interconnected biological pathways to influence stroke risk. Visceral adipose tissue actively secretes pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), inducing a state of chronic low-grade inflammation and stimulating hepatic CRP production8. Additionally, visceral fat contributes to metabolic abnormalities, including insulin resistance and dyslipidemia9,10, These metabolic disturbances contribute to the development and progression of atherosclerosis11,12. CRP exacerbates vascular injury by promoting endothelial dysfunction, reducing nitric oxide bioavailability, and increasing oxidative stress. These processes enhance the infiltration of inflammatory cells and lipids into arterial walls, accelerating the progression of atherosclerosis13,14. Together, elevated levels of VAI and CRP may synergistically intensify vascular inflammation, endothelial damage, and lipid deposition, thereby amplifying the risk of stroke. Although the individual roles of VAI and CRP in stroke risk are well-documented15,16,17,18, their combined and cumulative effects remain underexplored. Further research is essential to elucidate the mechanisms linking visceral adiposity and inflammation to cerebrovascular events and to develop targeted strategies for stroke prevention.

To comprehensively assess visceral obesity and low-grade inflammation, we developed the Visceral Obesity Inflammation Index (VAII), derived from the VAI and CRP. In this study, we evaluated the stroke predictive ability of the VAII by analyzing baseline, cumulative levels, and changes in VAII in relation to stroke risk, utilizing data from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) from 2011 to 202018. Our findings elucidate the effects and potential mediating mechanisms of the combined impact of visceral obesity and inflammation on stroke risk, emphasizing the role of the VAII in stroke risk assessment.

Methods

Study participants

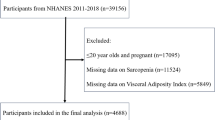

Our study utilized data from the China CHARLS, a nationally representative longitudinal survey targeting individuals aged 45 and above. CHARLS, organized by the National School of Development at Peking University, has been conducted in five waves between 2011 and 202019. For this analysis, we selected participants from the 2011 baseline survey (n = 17,708) and tracked them through four subsequent waves (2013, 2015, 2018, and 2020). Data were collected using standardized questionnaires and face-to-face interviews conducted by trained personnel, covering socio-demographic factors, lifestyle behaviors, and health-related indicators. After excluding individuals missing baseline blood test data, or follow-up participation, those younger than 45 years, and participants with a history of stroke at baseline, our final sample included 8,415 respondents (Fig. 1). The CHARLS protocol received ethical approval from the Biomedical Ethics Review Board of Peking University (IRB00001052-11,015), and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. All procedures adhered to the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Assessment of visceral adiposity inflammatory index (VAII), visceral adiposity index (VAI) and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (CRP)

The VAI, an indicator of visceral fat dysfunction20, serves as a reliable measure of visceral adiposity21. The VAI is calculated using the following formulas: [WC (cm)/(39.68 + 1.88 × BMI (kg/m2))] × (TG (mmol/L)/1.03) × (1.31/HDL (mmol/L)) = VAI for men and [WC (cm)/(36.58 + 1.89 × BMI (kg/m2))] × (TG (mmol/L)/0.81) × (1.52/HDL (mmol/L)) = VAI for females22. Here, WC represents waist circumference, BMI is body mass index, TG is triglycerides, and HDL refers to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. The VAII was calculated using a modification of the method proposed by Chen, J., et al. for the Remnant Cholesterol Inflammatory Index (RCII)23. Specifically, the VAII was calculated by multiplying the VAI by CRP: VAII = VAI × CRP. The cumulative VAII (CumVAII) was derived using the formula: CumVAII = [(VAII2012 + VAII2015) / 2] × (2015—2012). Similarly, cumulative VAI (CumVAI) and cumulative CRP (CumCRP) were computed using the same approach: CumVAI = [(VAI2012 + VAI2015) / 2] × (2015—2012) and CumCRP = [(hs-CRP2012 + hs-CRP2015) / 2] × (2015—2012). Here, VAII combines the effects of visceral adiposity and inflammation, while CumVAII, CumVAI, and CumCRP quantify their cumulative exposure over the study period. Using cluster analytical techniques in our prospective cohort study, we identified distinct temporal patterns of VAII evolution spanning two observational intervals (wave1 and wave3).

Outcome

The primary outcome of this study was the incidence of stroke. Consistent with prior research, stroke events were identified through the standardized question: "Did your doctor tell you that you were diagnosed with a stroke?". The timing of stroke events was determined as occurring within the interval between the date of the most recent interview and the date of the interview in which the stroke was first reported.

Covariates

The covariates included in this study were gender, baseline age, marital status (classified as ‘married’ or ‘other’), and educational attainment, categorized into three levels: 'Less than upper secondary education,' 'Upper secondary,' and 'Tertiary education,' based on years of schooling. Residential status was defined as ‘urban’ or 'rural.' Lifestyle factors such as current smoking, alcohol consumption, and exercise habits were dichotomized as ‘yes’ or 'no.' Health-related variables included loneliness, diagnosed history of hypertension, diabetes, heart disease, dyslipidemia, depression and the use of antihypertensive or antidiabetic medications. The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) (mL/min/1.73 m2), a measure of kidney function, was calculated using baseline creatinine levels and the 2021 CKD-EPI formula24.

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics across the different VAII groups were analyzed using statistical methods tailored to the data distribution, including analysis of variance (ANOVA), chi-square tests, or the Kruskal–Wallis rank-sum test. Continuous variables are presented as means with standard deviations, while categorical variables are reported as percentages for each of the four VAII categories. To handle missing data, we performed multiple imputation using mice package to ensure the robustness and reliability of the analyses. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were employed to assess the cumulative incidence of stroke among the groups over the study period.

Stroke risk was estimated using multivariable Cox proportional hazards models, which provided hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for VAII, VAI, and CRP. Univariate analyses were conducted without adjustments, while adjusted models included all covariates. The proportional hazards assumption was evaluated using Schoenfeld residuals, with the `cox.zph()` function employed to test both individual covariates and the global model. The results indicated no significant violations of the proportional hazards assumption (all P-values > 0.05), confirming that the model assumptions were appropriately satisfied.

The predictive performance of various indices was evaluated using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves. The significance of incremental predictive values between groups was assessed using the Net Reclassification Index (NRI) and the Integrated Discriminant Improvement Index (IDI). To quantify the contribution of VAII, VAI, or CRP in predicting stroke, we analyzed their relative importance alongside traditional risk factors by calculating the R2 values of the Cox models25. Additionally, the explainable log-likelihood attributed to each risk factor was computed to ensure consistency in the results25.

For multiplicative interactions, a product term combining VAI and CRP indicators was included in the Cox model, with the HR and corresponding 95% CI of the product term used to evaluate significance. For additive interactions, three metrics were calculated using the delta method: the relative excess risk due to interaction (RERI); the attributable proportion (AP); and the synergy index (S)26.

To evaluate the mediating effects of VAII, VAI and CRP, we dichotomized VAI and CRP at their median values. Regression models were then used to assess the direct and indirect effects of high VAI and high CRP on stroke risk26. The natural direct effect (NDE) represents the direct influence of the primary variable on stroke risk, while the natural indirect effect (NIE) quantifies the portion of stroke risk mediated by the primary variable. To determine the relative contribution of the mediating variable, the mediation ratio was calculated as: NIE / (NIE + NDE)26.

We determined the optimal cut-off values for CumVAII, CumVAI, and CumCRP to classify participants into high- and low-exposure groups. K-means clustering was employed to evaluate the change in VAII from wave 1 to wave 3. The optimal number of clusters was identified as 2 based on the elbow method and the silhouette coefficient approach. Furthermore, a cross-lagged panel model was constructed using Mplus software to investigate the temporal relationship between VAI and CRP, providing insights into the potential bidirectional associations between these variables over time.

To ensure the robustness of our results and to explore potential differences, we performed several sensitivity analyses: (1) The Chinese Visceral Adiposity Inflammation Index (CVAII) was utilized to assess stroke risk in place of the VAI. This substitution allowed for a more comprehensive evaluation of the combined effects of visceral adiposity and inflammation on stroke risk. (2) We conducted our analyses using datasets with complete covariates to ensure a robust and comprehensive evaluation of the associations. (3) Stratified analyses were conducted by sex (male and female), age group (< 60 and ≥ 60 years) and the presence of diabetes, hypertension, and heart disease. (4) Additionally, a 3-node restricted cubic spline (RCS) was utilized to explore the dose–response relationship and the linear association of stroke risk with VAII, VAI, and CRP. (5) E-values were calculated to evaluate the potential impact of unmeasured confounders on the observed associations in this observational study.

All statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 4.2.2) and Mplus software (Version 8.11 URL: https://www.statmodel.com). We also performed multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni correction. Multiple imputation of missing data was performed using mice package to address incomplete cases and enhance the reliability of the analyses. Mediation analyses were conducted using the mets package, and Cox regression analyses were conducted using the survival package, while both additive and multiplicative interactions were calculated using the interactionR package. We determined the optimal truncation value using the survminer package, the cluster package is used for cluster analysis. RCS curves were plotted using the rcssci package. ROC curves were calculated using the rms package, and NRI and IDI were calculated using the survIDINRI package.

Results

Population characteristics

A total of 8415 participants in CHARLS from 2011 to 2020 were included in the final analyses. During a median follow-up of 9.0 years, 796 participants (9.46%) experienced a stroke. The baseline characteristics of these participants, categorized by stroke status, were detailed in Table S 1. Table 1 presents a summary of the baseline characteristics of participants, categorized according to quartiles of the VAII. The mean (SD) age was 59.12 (9.19) years, a higher proportion of females, rising from 43.71% to 62.68% (p < 0.001). Renal function, indicated by eGFR, declined significantly with higher VAII (p < 0.001). Metabolic and cardiovascular conditions, including diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, heart disease, and stroke, showed a clear upward trend with increasing VAII levels (all p < 0.001). These findings suggest that higher VAII is closely linked to adverse health outcomes.

Association between CRP, VAI and VAII and incident stroke

Participants in the highest quartiles of VAII exhibited significantly higher cumulative hazards compared to those in the lowest quartiles (Fig. 2). Figure 3 illustrates the associations of VAII, VAI, and CRP with the risk of stroke. After adjusting for potential confounders, the results showed significant associations. Participants in the highest quartile of VAII (Q4) had a significantly higher risk of stroke compared to the lowest quartile (Q1), with an adjusted HR of 1.91 (95% CI: 1.53–2.38, p < 0.001). A similar trend was observed for VAI, where the adjusted HR for Q4 versus Q1 was 1.74 (95% CI: 1.38–2.19, p < 0.001). For CRP, participants in Q4 also had an increased stroke risk with an adjusted HR of 1.52 (95% CI: 1.23–1.87, p < 0.001).

Associations of VAII, VAI and CRP with the risk of stroke. Adjusted Model included Age, eGFR (Cystatin C), Depression, Gender, Marital Status, Education Level, Rural Area, Smoking Status, Diabetes, Hypertension, Antidiabetic Medication, Antihypertensive Medication, Drinking Status, Dyslipidemia, Loneliness, Exercise Status, and Heart Disease.

Notably, the association between CRP, VAI and stroke risk was weaker compared to VAII in the highest quartiles. These findings suggest that VAII maybe a stronger predictors of stroke risk compared to CRP and VAI, highlighting the importance of visceral adiposity and related inflammation in cerebrovascular disease.

Predictive value of CRP, VAI and VAII in incident stroke

Figure 4A, B demonstrates the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves and the relative importance of VAII, VAI, and CRP in predicting stroke. The Area Under the Curve (AUC) values indicate that VAII has the highest predictive power among the three indices. For individual models, VAII achieved an AUC of 0.648 (95% CI: 60.51–69.1), followed by CRP (AUC = 0.637, 95% CI: 59.21–68.19) and VAI (AUC = 0.588, 95% CI: 54.05–63.51). When combined with the base model, the AUC further improved to 0.764 (95% CI: 72.73–79.98), highlighting the added discriminatory value of VAII.

ROC curve and relative importance of VAII, VAI and CRP for predicting stroke. (A) Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves for VAII, VAI, and CRP were used independently to evaluate their discriminatory ability by calculating the Area Under the Curve (AUC). (B) The base model included the following variables: Age, eGFR (Cystatin C), Depression, Gender, Marital Status, Education Level, Rural Area, Smoking Status, Diabetes, Hypertension, Antidiabetic Medication, Antihypertensive Medication, Drinking Status, Dyslipidemia, Loneliness, Exercise Status, and Heart Disease. Combine VAII, VAI and CRP with the basic model in that order. (C) Relative importance of risk factors for predicting stroke.

The incremental predictive value of VAII, VAI, and CRP for stroke is summarized in Table 2. When added to the base model, which included traditional risk factors, each marker significantly improved the model’s predictive ability. The integrated discrimination improvement (IDI) and net reclassification improvement (NRI) metrics highlight VAII as the strongest contributor. Specifically, adding VAII to the base model resulted in an IDI of 0.006 (95% CI: 0.001–0.012, p < 0.001) and an NRI of 0.169 (95% CI: 0.028–0.244, p < 0.001), outperforming CRP (IDI = 0.004, NRI = 0.138) and VAI (IDI = 0.002, NRI = 0.120). When each index was utilized individually for stroke prediction, the VAII had improved predictive ability compared with both CRP and VAI (Table S2).

The relative importance analysis (Fig. 4C) further underscores the significant role of VAII in predicting stroke, ranking higher in importance compared to CRP and VAI. VAII consistently ranked as the most important marker compared to traditional risk factors such as hypertension, dyslipidemia, and heart disease. To validate our findings, we also examined the relative strengths of these risk factors for stroke using explained log-likelihood (Figure S1) and found that the ranking of VAII, VAI, CRP was consistent with that observed using explained relative risk (R2) model. These findings collectively underscore the predictive strength of VAII as a marker for stroke and its superiority over VAI and CRP. The integration of VAII into clinical models may improve risk stratification for cerebrovascular events.

Interactive effects of VAI and CRP on incident stroke

The interactive effects of VAI and CRP on incident stroke are presented in Table 3. For additive effects, the relative excess risk due to interaction (RERI) was − 0.01 (95% CI: − 0.43 to 0.4), the attributable proportion (AP) was − 0.01 (95% CI: − 0.23 to 0.21), and the synergy index (SI) was 0.98 (95% CI: 0.62 to 1.56). For multiplicative interactions, the interaction term (INTM) was 0.9 (95% CI: 0.67 to 1.2). These findings indicate that there was no statistically significant interaction between VAI and CRP in the risk of stroke, either on an additive or multiplicative scale.

Mediation analyses of stroke risk factors

Figure 5 illustrates the mediation analyses of stroke risk factors. For the VAII-stroke pathway, the analysis reveals that systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) serve as significant mediators. The triglyceride-glucose index (TyG) emerges as another critical mediator in this pathway, exhibiting an total HR of 1.433 (95% CI: 1.239–1.657) and an indirect HR of 1.069 (95% CI: 1.002–1.114), which accounts for 18.5% of the mediation effect. This emphasizes the significance of metabolic dysfunction in linking VAII to increased stroke risk. Fasting blood glucose (FBG) also demonstrates mediation effects.

Mediation analyses of stroke risk factors. Adjusted for Age, eGFR (Cystatin C), Depression, Gender, Marital Status, Education Level, Rural Area, Smoking Status, Diabetes (with the exception of the FBG model), Hypertension (with the exception of the SBP and DBP models), Antidiabetic Medication, Antihypertensive Medication, Drinking Status, Dyslipidemia, Loneliness, Exercise Status, and Heart Disease. VAII, VAI and CRP were categorized into two groups based on the 50% cut-off. Abbreviations: VAI, visceral adiposity index; CRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; FBG, fasting blood glucose; TyG, triglyceride-glucose index.

Figure 5 summarizes the mutual mediating effects linking VAI and CRP to stroke events. High CRP significantly mediated 16.2% (P < 0.001) of the association between a high VAI and stroke events, while VAI simultaneously mediated 9.0% (P < 0.001) of the association between high CRP and stroke risk in the fully adjusted model. These analyses reveal significant mediation effects, highlighting the interrelationship between systemic inflammation and visceral adiposity in stroke risk.

Association between cumulative VAII, VAI and CRP and incident stroke

Figure S2 identifies the optimal cut-off values for cumulative indices of visceral adiposity (CumVAI), inflammation (CumCRP), and visceral adiposity inflammatory index (CumVAII): 5.48 for CumVAI, 4 for CumCRP, and 6.29 for CumVAII, stratifying individuals into high- and low-level groups. Using these cut-offs, Kaplan–Meier plots in Figure S3 demonstrate that high levels of cumulative indices are associated with significantly greater cumulative stroke risk over time.

Further quantification in Fig. 6 reveals that each index independently predicts stroke risk after adjustment for confounding factors. Higher levels of CumVAII (HR = 1.41, 95% CI: 1.15–1.71), CumVAI (HR = 1.32, 95% CI: 1.09–1.59), and CumCRP (HR = 1.36, 95% CI: 1.12–1.65) are significantly associated with increased stroke incidence. Moreover, Figure S4highlights the combined effects of CumVAI and CumCRP, showing that individuals with elevated levels of both markers experience the highest stroke risk (HR = 1.7, 95% CI: 1.31–2.19). The change in VAII was categorized into two groups based on clustering analysis of wave 1 and wave 3 VAII (Figure S5). After multivariate adjustment, the high-VAII cluster was not significantly associated with stroke risk (HR: 1.35, 95% CI: 0.97–1.87, P = 0.076) (Fig. 6).

Association between cumulative and change in VAII, VAI and CRP and incident stroke. Adjusted Model included Age, eGFR (Cystatin C), Depression, Gender, Marital Status, Education Level, Rural Area, Smoking Status, Diabetes, Hypertension, Antidiabetic Medication, Antihypertensive Medication, Drinking Status, Dyslipidemia, Loneliness, Exercise Status, and Heart Disease.

Figure S6 shows the cross-lagged panel model of the relationship between VAI and CRP. Cross-lagged effects indicate that baseline VAI predicts future CRP (β = 0.22), while baseline CRP has a effect on future VAI (β = 0.07). These results suggest the temporal correlation and chronic interplay observed between VAI and CRP.

Subgroup and sensitivity analysis

Figure S7 demonstrates the associations of Chinese Visceral Adiposity Inflammatory Index (CVAII) and Chinese Visceral Adiposity Index (CVAI) with stroke risk. In Figure S7, higher quartiles of both CVAII and CVAI are significantly associated with an increased risk of stroke. The dataset incorporating the full set of covariates further validates these associations (Figure S8). Specifically, VAII, VAI, CRP, as well as cumulative VAII, VAI, and CRP, were consistently and strongly positively associated with stroke risk. Subgroup analyses in Figures S9 and S10 reveal that the associations between VAII (both baseline and cumulative) and stroke are consistent across various demographic and clinical subgroups, including age, gender, and comorbidity status. Figures S11 to S13 highlight the nonlinear relationships between baseline and cumulative measures of VAII, VAI, and CRP with stroke risk. Table S3 presents E-values, providing sensitivity analysis for unmeasured confounding. The high E-values for the upper quartiles of VAII (3.23), VAI (2.87), and CRP (2.41) demonstrate that the observed associations with stroke risk are unlikely to be entirely explained by unmeasured confounders.

Discussion

Stroke is a significant global health concern, being one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide1,2. As the prevalence of stroke continues to rise, understanding its risk factors and mechanisms becomes increasingly vital. While traditional risk factors, such as hypertension, diabetes, and smoking, have been extensively studied27, there remains a critical need to identify additional biomarkers and novel risk factors to enhance prevention and treatment strategies.

Abdominal obesity is linked to a range of metabolic abnormalities, including insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and inflammation9,10,28. These metabolic disturbances play a significant role in the onset and advancement of atherosclerosis, which is a major factor in the occurrence of stroke29. Atherosclerosis is a chronic inflammatory condition. The interaction between lipid metabolism and vascular inflammation plays a pivotal role in the development of atherosclerotic plaques11,12. VAI, an index reflecting visceral fat dysfunction, and CRP, a marker of systemic inflammation, likely interact through multiple interconnected biological pathways to influence stroke risk. Visceral adipose tissue is metabolically active, secreting a variety of pro-inflammatory cytokines, which contribute to a state of chronic low-grade inflammation. The individual contributions of VAI and CRP to stroke risk are well-documented15,16,17,18. These findings underscore the importance of simultaneously assessing VAI and CRP to enhance stroke risk prediction. In our study, we introduced the VAII, a novel and comprehensive metric designed to evaluate the interaction between visceral adiposity and inflammatory pathways in the pathogenesis of stroke. The combined and cumulative effects of these factors may involve a more complex interplay of metabolic and inflammatory pathways. Our findings revealed that VAII is significantly associated with stroke risk and outperforms traditional markers such as VAI and CRP in predictive accuracy. This is demonstrated by its superior AUC values and enhanced performance in incremental predictive metrics, including IDI and NRI, as well as in relative importance analyses. By integrating VAII into clinical models, we observed a marked improvement in stroke risk stratification, highlighting its potential as a novel and robust biomarker. This method offers a practical approach for identifying high-risk patients, enabling clinicians to perform more precise risk assessments and implement targeted interventions aimed at reducing stroke incidence. These results support the clinical utility of VAII as an innovative tool for improving patient outcomes.

Our study also explored the potential interaction between VAI and CRP in relation to stroke risk. Contrary to our initial hypothesis, the findings indicate no significant synergistic or interactive effect between these two factors. While both VAI and CRP independently contribute to stroke risk15,16,17,18, their combined impact does not appear to exceed the sum of their individual effects. This observation adds a layer of complexity to our understanding of how these markers collectively influence stroke risk. Stroke is a multifactorial condition driven by a complex interplay of diverse risk factors, including hypertension, smoking, diet, genetics, and metabolic health30,31. These underlying factors may modulate or overshadow the interaction between VAI and CRP, potentially explaining the absence of a pronounced synergistic effect. These results underscore the importance of considering the broader context of stroke pathophysiology and highlight the need for further research to elucidate the mechanisms underlying the relationship between metabolic and inflammatory markers in stroke risk prediction.

While our study did not reveal a synergistic interaction between VAI and the CRP, it did underscore the importance of considering these factors jointly in stroke risk assessment. Our findings suggest that the combination of both VAI and the CRP may provide greater efficacy in predicting stroke risk than either factor alone. However, the exact physiological mechanisms connecting VAI and the CRP to the onset of stroke are still unclear. In this study, we employed mediation analysis to investigate the mediating roles of VAI and the CRP in stroke development. We found that elevated levels of VAI significantly mediated 9.0% of the relationship between CRP and stroke risk, while increased CRP, in turn, mediated 16.2% of the association between VAI and stroke, highlighting the reciprocal mediating relationship between these two biomarkers. Moreover, mediation analyses revealed that the association between VAII and stroke is partially mediated through systemic inflammation and metabolic dysfunction, as reflected by elevated systolic and diastolic blood pressure, TyG, and fasting blood glucose. Cross-lagged analyses also indicate a bidirectional relationship between VAI and CRP, supporting the hypothesis that visceral fat perpetuates a pro-inflammatory state.

By evaluating the combined long-term effects of the VAI and CRP through the cumulative VAII, we identified a strong and significant association between elevated cumulative VAII levels and increased stroke risk. This novel index provides a more comprehensive assessment by integrating the chronic interplay between VAI and CRP over time, thereby reflecting the sustained influence of metabolic and inflammatory factors on stroke risk. The introduction of the cumulative VAII concept offers a valuable tool for evaluating long-term stroke risk and deepens our understanding of the role that prolonged elevations in VAI and CRP play in stroke development. These findings underscore the importance of considering cumulative exposures to metabolic and inflammatory markers in stroke risk assessment and suggest that VAII could serve as a clinically relevant biomarker for identifying high-risk individuals and guiding early interventions.

This study has several strengths, including its large sample size, long follow-up duration, and comprehensive adjustment for potential confounders. By examining both baseline and cumulative measures, we captured the dynamic and long-term impacts of visceral adiposity and inflammation on stroke risk. Advanced statistical approaches, such as mediation and interaction analyses, further enhance the robustness of our findings.

However, certain limitations should be acknowledged. First, the observational design of this study restricts our ability to establish causal relationships between VAII and stroke incidence. Residual confounding cannot be entirely excluded despite rigorous adjustments. Second, reliance on self-reported stroke diagnosis may introduce misclassification bias, although validation studies in similar settings suggest high reliability. Lastly, the study population, predominantly middle-aged and older Chinese adults, may limit the generalizability of findings to other ethnic groups or younger populations. Future studies should aim to address these limitations through more rigorous validation methodologies and diverse cohorts.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study underscores the significant association between VAII and stroke risk, emphasizing the critical roles of visceral adiposity and systemic inflammation in cerebrovascular events. Our findings demonstrate the superior predictive performance of VAII compared to traditional biomarkers, highlighting its potential as a clinical tool for enhanced risk stratification and prevention strategies. As stroke remains a critical public health challenge, further research is essential to validate these results and elucidate the underlying mechanisms linking visceral fat dysfunction to stroke. Ultimately, integrating VAII into clinical practice could contribute to improved patient outcomes, reduced healthcare burdens, and more effective management strategies for populations at risk of stroke.

Data availability

The dataset(s) supporting the conclusions of this article are available in the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) repository, accessible at http://charls.pku.edu.cn/en. The CHARLS dataset is a publicly available resource, and researchers can request access by following the repository’s application procedures.

References

Feigin, V. L. et al. Global, regional, and national burden of stroke and its risk factors, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Neurol. 20(10), 795–820 (2021).

Ma, Q. et al. Temporal trend and attributable risk factors of stroke burden in China, 1990–2019: An analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Public Health 6(12), e897–e906 (2021).

O’Donnell, M. J. et al. Global and regional effects of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with acute stroke in 32 countries (INTERSTROKE): A case-control study. Lancet 388(10046), 761–775 (2016).

Meschia, J. F. et al. Guidelines for the primary prevention of stroke: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 45(12), 3754–3832 (2014).

Britton, K. A. et al. Body fat distribution, incident cardiovascular disease, cancer, and all-cause mortality. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 62(10), 921–925 (2013).

Schousboe, J. T. et al. Central obesity and visceral adipose tissue are not associated with incident atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease events in older men. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 7(16), e009172 (2018).

Ballin, M. et al. Associations of visceral adipose tissue and skeletal muscle density with incident stroke, myocardial infarction, and all-cause mortality in community-dwelling 70-year-old individuals: A prospective cohort study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 10(9), e020065 (2021).

Malavazos, A. E. et al. Proinflammatory cytokines and cardiac abnormalities in uncomplicated obesity: Relationship with abdominal fat deposition. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 17(4), 294–302 (2007).

Bosello, O. & Zamboni, M. Visceral obesity and metabolic syndrome. Obes. Rev. 1(1), 47–56 (2000).

Després, J.-P. Health consequences of visceral obesity. Ann. Med. 33(8), 534–541 (2001).

Kraaijenhof, J. M. et al. The iterative lipid impact on inflammation in atherosclerosis. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 32(5), 286–292 (2021).

Waksman, R. et al. Targeting inflammation in atherosclerosis: overview, strategy and directions. EuroIntervention 20, 32–44 (2024).

Suh, W. et al. C-reactive protein impairs angiogenic functions and decreases the secretion of arteriogenic chemo-cytokines in human endothelial progenitor cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 321(1), 65–71 (2004).

Hage, F. G. C-reactive protein and hypertension. J. Hum. Hypertens. 28(7), 410–415 (2014).

Ren, Y. et al. Dose-response association between Chinese visceral adiposity index and cardiovascular disease: A national prospective cohort study. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 15, 1284144 (2024).

Cui, C. et al. Association between visceral adiposity index and incident stroke: Data from the China Health and retirement longitudinal study. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 32(5), 1202–1209 (2022).

McCabe, J. J. et al. C-reactive protein, interleukin-6, and vascular recurrence after stroke: An individual participant data meta-analysis. Stroke 54(5), 1289–1299 (2023).

McCabe, J. J. et al. C-reactive protein, interleukin-6, and vascular recurrence according to stroke subtype: An individual participant data meta-analysis. Neurology 102(2), e208016 (2024).

Zhao, Y. et al. Cohort profile: The China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). Int. J. Epidemiol. 43(1), 61–68 (2014).

Yu, J. et al. The visceral adiposity index and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in China: A national cohort analysis. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 38(3), e3507 (2022).

Wang, N. et al. Visceral fat dysfunction is positively associated with hypogonadism in Chinese men. Sci. Rep. 6, 19844 (2016).

Zheng, X. et al. Association between visceral adiposity index and chronic kidney disease: Evidence from the China health and retirement longitudinal study. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 32(6), 1437–1444 (2022).

Chen, J., et al., Predictive value of remnant cholesterol inflammatory index for stroke risk: Evidence from the China health and Retirement Longitudinal study. J. Adv. Res., 2024.

Inker, L. A. et al. New creatinine- and cystatin C-based equations to estimate GFR without race. N Engl. J. Med. 385(19), 1737–1749 (2021).

Wang, X. et al. Joint association of loneliness and traditional risk factor control and incident cardiovascular disease in diabetes patients. Eur. Heart J. 44(28), 2583–2591 (2023).

Huo, R. R. et al. Interacting and joint effects of triglyceride-glucose index (TyG) and body mass index on stroke risk and the mediating role of TyG in middle-aged and older Chinese adults: A nationwide prospective cohort study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 23(1), 30 (2024).

Guzik, A. & Bushnell, C. Stroke epidemiology and risk factor management. Continuum Minneap Minn 23(1), 15–39 (2017).

Ritchie, S. & Connell, J. The link between abdominal obesity, metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 17(4), 319–326 (2007).

Zhou, W. et al. Early warning of ischemic stroke based on atherosclerosis index combined with serum markers. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 107(7), 1956–1964 (2022).

Boehme, A. K., Esenwa, C. & Elkind, M. S. Stroke risk factors, genetics, and prevention. Circ. Res. 120(3), 472–495 (2017).

Della-Morte, D. et al. Genetics of ischemic stroke, stroke-related risk factors, stroke precursors and treatments. Pharmacogenomics 13(5), 595–613 (2012).

Acknowledgements

We thank the China Center for Economic Research, the National School of Development of Peking University for providing the data of CHARLS.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.X. wrote the main manuscript and contributed to the study design. J.Y. and W.H. contributed to the study conception. A.X. contributed to data curation and analysis. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xiao, Q., Xue, A., Huang, W. et al. Evaluating the visceral adiposity inflammatory index for enhanced stroke risk assessment. Sci Rep 15, 14971 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99024-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99024-6