Abstract

The high concentration of fluoride in the soil can serve as a pathway for this element to enter the body through food products. The purpose of this research was to investigate the fluoride concentrations in drinking water sources, regional soil, and cultivated vegetables (tomatoes, cucumbers, onions, and potatoes), as well as to assess the relationship between fluoride concentration in drinking water and fluoride content in food products. Additionally, the study aimed to evaluate the risk of exposure using a Monte Carlo simulation in Hamadan. This cross-sectional analytical study was conducted in 2021 in Hamadan. To assess water fluoride levels in different villages, 26 wells were selected. After evaluating the fluoride concentrations, two areas with water fluoride levels above the standard were identified, along with two areas with fluoride levels below the standard. From these four agricultural sites, three soil samples were collected from each location, resulting in a total of 24 soil samples. For each site, three samples of cultivated vegetables (tomatoes, cucumbers, onions, and potatoes) were also collected, yielding a total of 92 samples from areas with both high and low water fluoride concentrations. Fluoride analysis in drinking water was performed using the SPADNS method, while the fluoride content in vegetables was measured with a standard ion-selective electrode method. The results indicated that the average fluoride concentrations in the high-fluoride area for drinking water, tomatoes, onions, cucumbers, and soil were as follows: 3.5 ± 0.5 mg/L, 2.38 ± 0.15 mg/kg, 1.89 mg/kg, 0.39 ± 0.05 mg/kg, and 110.5 ± 0.03 mg/kg, respectively. In contrast, the average concentrations in the low-fluoride area were 0.3 ± 0.1 mg/L for drinking water, 11.0 ± 0.009 mg/kg for tomatoes, 1.29 ± 0.5 mg/kg for onions, 98.05 ± 0.02 mg/kg for cucumbers, and 1.6 ± 0.02 mg/kg for soil. A direct relationship was observed between the fluoride concentration in water and the amounts found in tomatoes, cucumbers, and onions. The estimated total dietary fluoride intake for children during summer and spring was 120.6 and 145.6 µg/kg/day, respectively. For adults, these values were 99.2 and 112 µg/kg/day. This study indicated that drinking water was the primary source of dietary fluoride intake in the study area. Furthermore, the hazard quotient (HQ) values for both adults and children were found to be greater than 1, confirming a potential health risk of fluorosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Fluoride is a natural element found in the Earth’s crust and is classified as one of the trace elements essential for humans and animals. It is present in soil, rock, water, and the biological chains of plants and animals. As a halogen, fluoride is the most electronegative ion in the periodic Tables 1,2.

Fluoride plays a crucial role in the human diet, with primary dietary sources including drinking water, processed foods made with fluoridated water, tea, certain vegetables, fruits, dental products, and seafood3,4. However, fluoride levels in groundwater can also be elevated due to human activities. For instance, phosphate fertilizers, pesticides, fumigants, herbicides, and insecticides often contain fluoride as an impurity5,6.

The main source of fluoride entering the hydrological system is volcanic activity, which contributes to the formation of fissures and the chemical weathering of volcanic rocks. The geochemistry of fluoride has been extensively studied, revealing that fluoride uptake is strongly dependent on pH7. Weathering of basalts has increased sodium ion concentrations and pH levels, leading to the release of fluoride from aquifers. The movement of fluoride in soils is complex, with key factors influencing its levels in soil solutions, including clay minerals, calcium and phosphorus concentrations, pH, and iron (Fe) and aluminum (Al) oxides. Clay and phosphorite can significantly slow the movement of fluoride in soil. Additionally, the solubility and leaching of aluminum in soil increase with higher fluoride content8,9.

Awareness of the environmental issues related to fluoride in drinking water has grown, particularly due to its association with skeletal abnormalities and dental fluorosis10,11. However, the complications and risks associated with high fluoride levels far outweigh its benefits, which include potential bone complications, cancer risk, kidney damage, thyroid dysfunction, and brain impairment12,13. Fluoride concentrations in drinking water sources (such as wells and springs) can vary significantly based on the type of source, season, and treatment processes14. For example, fluoride concentration has an inverse relationship with temperature; according to WHO standards, the maximum acceptable level of fluoride in drinking water is 1.5 mg/L at temperatures between 8 and 12 degrees Celsius, and 0.7 mg/L at temperatures between 25 and 30 degrees Celsius15,16. Studies have shown that the people of countries such as Algeria17, Turkey18, China19, Jordan20, India21, and Iran22 have suffered from fluorosis due to the consumption of fluoride-rich substances23. Over the past few decades, the number of harmful environmental agents has increased significantly, exposing humans to a wide range of pollutants and harmful chemical, physical, and biological agents in various environments24.

Human health risk assessment is a scientific process aimed at identifying and estimating the potential effects of chemical, physical, microbiological, or psychological agents on specific human populations under defined conditions and over specific time periods. This process involves four steps: hazard or risk factor identification, dose-response or dose-effect relationships, exposure assessment, and risk characterization2,25.

Given the location of Hamadan city, the extensive agricultural lands, the excessive use of chemical fertilizers—particularly nitrogen and phosphate fertilizers—and the pollution from various sources in the Hamadan plain, along with the heavy reliance on groundwater for public and agricultural purposes, there is a concerning negative balance and a continuous decline in water levels. This situation has rendered the Hamadan plain one of the most critical areas in Iran. Therefore, investigating the contamination of groundwater and soil with fluoride is both important and necessary.

This study aimed to investigate the relationship between fluoride concentration in drinking water and fluoride content in food products. In addition, this study is the first to evaluate fluoride migration in the soil-water-food chain in Hamadan. Monte Carlo simulation for health risk assessment was used to explain the health effects of fluoride on local residents due to fluoride exposure through drinking water and major food items, including vegetables. Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate fluoride concentrations in drinking water sources, the soil of the region, and cultivated vegetables (tomatoes, cucumbers, onions, and potatoes).

Materials and methods

Characteristics of the studied area

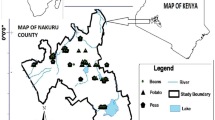

Hamadan province (34.7982°N, 48.5146°E) comprises nine counties, with Hamadan County being the most populated. The city of Hamadan, located in the central region of the province, covers an area of 4,084 square kilometers, accounting for 21% of the province’s total area. With a population of 651,821, Hamadan city represents 37% of the province’s population and includes 118 villages. Set against the backdrop of Mount Alvand, the city stands at an altitude of 1,741 m above sea level and is considered one of the coldest cities in Iran.

The climate of Hamadan is diverse, with significant variations in weather conditions, including temperature extremes and rainfall throughout the seasons. In the cold mountainous areas, the average annual snowfall ranges from 155 to 245 mm, with temperatures dropping to as low as -30 °C. The average annual temperature in Hamadan is 11.3 °C, with recorded temperatures reaching highs of 40 °C and lows of -32.8 °C. The average annual rainfall in Hamadan is reported to be 317.7 mm.

The groundwater table in this region is primarily replenished by rainfall and numerous streams originating from the slopes of Alvand Mountain. Most drinking water sources in the villages of Hamadan are derived from groundwater and wells26.

The most notable igneous feature of the region is the Alvand plutonic massif, which is surrounded by metamorphic rocks exhibiting varying degrees of metamorphism. The metamorphic rocks in Hamadan can be classified into three groups: migmatites, Hembri metamorphic rocks, and regional metamorphic rocks27.

The necessity of this research, titled “Investigation of Fluoride Concentration in Soil, Drinking Water, and Their Relation with Fluoride in Tomato, Cucumber, Potato, and Onion in Hamadan,” was carried out in 2021. Figure 1 illustrates the geographical location of the study area.

Sampling method and measurement of fluoride concentration

In Hamadan city, there are 40 rural wells, from which 26 water samples were collected. Sampling was conducted during both wet and dry seasons. All sampling and data analysis procedures adhered to the standard methods for water and wastewater testing28.

Water samples were collected using 1000 mL polyethylene bottles and transported to the water and wastewater laboratory under standard conditions, ensuring an appropriate temperature of less than 8 °C. Fluoride analysis was performed using the SPADNS method and a calibrated spectrophotometer (HACH Chemical Company, DR-2000s, USA)29. A fluoride stock solution of 1000 mg/L was prepared and stored at 4 °C. Various concentrations of working standard solutions, ranging from 0.1 to 10.0 mg/L, were created by accurately diluting an intermediate standard solution (50 mg/L) with deionized water.

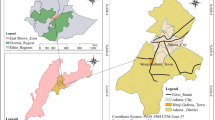

After determining the fluoride concentrations in drinking water, one village with a fluoride concentration above the standard and another with a concentration below the standard were selected from the studied villages (Fig. 2). It was found that wells No. 15 and 16 had fluoride concentrations of 4 mg/L, while wells No. 5 and 23 recorded concentrations of 0.4 mg/L. Therefore, wells No. 15 and 16 were identified as high-fluoride areas, and wells No. 5 and 23 as low-fluoride areas. Subsequently, soil, potato, tomato, cucumber, and onion samples were collected from these two regions.

Number of samples of soil and cultivated vegetables (tomatoes, cucumbers, onions and potatoes)

To investigate the fluoride content of water in different villages in the region, 20 wells were selected for evaluation. Based on the concentration analysis, two wells were identified as having fluoride concentrations above the standard level, while two others were identified as having fluoride levels below the standard.

From the four selected agricultural sites in the high-fluoride areas, three soil samples were collected from each site, resulting in a total of 12 soil samples. Additionally, from each site, three cultivated vegetable samples (tomatoes, cucumbers, onions, and potatoes) were collected, yielding a total of 12 vegetable samples from the high-fluoride areas.

Similarly, from the four selected agricultural sites in the low-fluoride areas, three soil samples were taken from each site, totaling another 12 soil samples. Three cultivated vegetable samples of each type were collected from these sites as well, resulting in an additional 12 vegetable samples from the low-fluoride areas.

In summary, the study comprised 12 soil samples and 48 vegetable samples from areas with high fluoride concentrations, as well as 12 soil samples and 48 vegetable samples from areas with low fluoride concentrations.

The method of sampling and measuring the concentration of fluoride in plant foods

The fluoride concentration in the samples was measured using the potentiometric method with a fluoride ion-selective electrode (F-ISE) as the working electrode and a silver/silver chloride reference electrode (Metrohm, model 744, Switzerland, pH/ion meter benchtop electrochemical instrument)29. The fluoride concentration was determined by measuring the potential difference across an interface designed to respond specifically to fluoride ions. Values for fluoride concentration in the sample solutions were recorded by matching the potential of the samples against a calibration curve constructed from a series of fluoride working standard solutions.

All samples were analyzed in the laboratory of the Water Safety Research Center (WSRC) under the Deputy of Food and Drug in the Ministry of Health and Medical Education. The pH of the sample solutions was also adjusted and measured using a digital Metrohm pH meter (744, Switzerland) equipped with a combined glass/calomel electrode.

Validation of the F-ISE results was performed through experiments utilizing reference standard solutions and by spiking known amounts of fluoride into the sample matrix. The accuracy of the F-ISE was evaluated through recovery tests. Recoveries of fluoride from agricultural samples spiked at three different concentrations (1.0, 5.0, and 10.0 mg/L) showed excellent accuracy, with recovery percentages ranging from 95.6 to 103.7% and relative standard deviations (RSDs) of less than 3.8%.

Intra-day and inter-day precision were calculated as RSDs (%; n = 3). The precision for the inter-day evaluation of fluoride standard solutions at 1.0 mg/L, 5.0 mg/L, and 10.0 mg/L were 3.8%, 3.3%, and 2.8%, respectively. Intra-day experiments yielded precision values of 3.2%, 2.7%, and 2.2%, indicating appropriate precision and accuracy for the analysis of fluoride in the studied samples.

Sampling and measurement of fluoride concentration in soil

In this study, 12 soil samples were collected from a depth of 0–35 cm from villages with water fluoride concentrations above the standard, while 6 soil samples were taken from villages with fluoride concentrations below the standard. After air drying, the soil samples were crushed and passed through a 2 mm sieve.

To determine the concentration of fluoride soluble in water, 20 g of each soil sample was weighed, and 50 cc of cyanide water was added. The samples were shaken for 10 min. Following shaking, the samples were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 25 min, and the clear supernatant was filtered using Whatman 42 filter paper30. The concentration of fluoride in the soil samples was subsequently analyzed using ion exchange chromatography (Metrohm, Switzerland)31.

Risk assessment of fluoride using the USEPA index method

Non-carcinogenic fluoride risk assessment involves evaluating health risks associated with fluoride exposure as determined by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). This assessment utilizes a metric known as the Target Hazard Quotient (THQ), which estimates the non-carcinogenic effects of fluoride. The THQ is calculated by comparing the concentration of fluoride in the environment to a standard value known as the Oral Reference Dose (RfD).

Health risk assessment was conducted by estimating the exposure doses of fluoride resulting from the consumption of drinking water and vegetables. The Estimated Daily Intake (EDI) of fluoride was calculated using the following equation (Eq. 1, 2):

In Eq. 1, C is the mean concentration of fluoride in drinking water and food consumed during the exposure time, used to determine the level of chemicals in the sanitary drinking water. IR is the amount of drinking water and food consumed (L/d and g/d), which is directly related to the individual’s exposure to contaminants. ED is the duration of exposure (70 years for adults and 10 years for children), BW is the average body weight (70 kg for adults and 32 kg for children), and AT is the average exposure time to non-carcinogenic effects (in years/365 days).

The input values used in exposure calculations and risk assessment are presented in Table 1.

after determining the EDI and the value of reference dose (RfD), the rate of non-carcinogenic risk for fluoride was calculated based on Eq. 22. The sum of Hazard Quotient (HQ) is the risk of non-carcinogenic substances, EDI is the mean daily dose (mg/kg-day), and RFD is the reference dose (mg/kg/day). The RfD for fluoride is 0.06 mg/kg-d2.

The risk index or HI is obtained from the sum of THQ (Eq. 3).

According to the above information, if HI < 1 means that the use of water and food has an adverse effect on the consumer, and if HI > 1 means safe conditions for the consumer32.

Carcinogenicity risk assessment by Monte Carlo simulation method

Unlike deterministic methods, the Monte Carlo method focuses on the occurrence of probable events over time, relying on probability distributions rather than a singular, realistic view of how processes will unfold. This approach utilizes a sequence of random numbers in both the time and space domains, combined with input data to assess the feasibility of potential events.

When calculating health risks for a population exposed to one or more potential risk factors, using a single point estimate can lead to interference, errors, and ultimately uncertainty in the results. To minimize this uncertainty, this study employs the Monte Carlo simulation method. Instead of representing a variable with a single value, this method uses a range of values associated with that variable. The calculations are repeated numerous times, and the results are presented to the user with varying degrees of confidence, ranging from 1 to 99%.

Data analysis

After collecting the information, the data were entered into software for analysis. Descriptive statistics were generated using frequency tables along with indices of central tendency and dispersion, including the mean, standard deviation, and variance. The normality of the data was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test.

Correlations were evaluated with Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients. Comparisons of values between two groups or several independent groups were conducted using the independent t-test and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), along with their non-parametric equivalents, the Mann-Whitney test and the Kruskal-Wallis test. To assess the impact of covariates on a quantitative response, multiple linear regression was employed. For evaluating the effects of covariates on binary and multiclass responses, binary logistic regression and polynomial (ordinal) logistic regression were utilized.

Preparation of Spatial distribution map of elements

To prepare a zoning map of element concentrations in the studied area, version 3.9 of ArcGIS software was utilized. An information bank was created using the results from the concentration readings of the elements. Following this, spatial distribution maps for each element were generated based on the weighted interpolation method known as Inverse Distance Weighted (IDW). Finally, the necessary analyses were conducted on the resulting hysteresis map.

Results

Fluoride distribution map in Hamadan rural drinking water sources

As illustrated in Fig. 2, the distribution of fluoride in drinking water sources during the cold (A1) and dry (B1) seasons was analyzed from the 40 rural wells in Hamedan County, of which 26 water samples were collected. In the cold season, the highest fluoride concentration measured was 3.8 mg/L, while the lowest concentration recorded was 0.3 mg/L. In the dry season, the highest fluoride concentration increased to 4 mg/L, with the same minimum concentration of 0.3 mg/L observed.

Among the villages studied, water sources were identified with fluoride concentrations exceeding the standard limit, as well as one or two sources with concentrations below the standard limit. Subsequently, soil and samples of potatoes, tomatoes, cucumbers, and onions were collected from areas where the fluoride concentration of their water sources was above the standard limit and from those below it.

Fluoride distribution map in drinking water sources, soil, food products

Table 2 presents the average fluoride concentrations and the coefficient of variation (CV) in water, soil, and food products within the region. The table indicates that the average fluoride concentrations in soil, tomatoes, onions, and cucumbers from areas with high water fluoride levels were 110.5 ± 0.03 mg/kg, 2.38 ± 0.15 mg/kg, 1.89 ± 0.02 mg/kg, and 0.39 ± 0.05 mg/kg, respectively.

In areas with high fluoride concentrations in water, the highest fluoride concentration of 4 mg/L was detected in groundwater samples, while the lowest concentration of 0.3 mg/L was found in cucumber samples. Conversely, in regions where water fluoride levels were low, the highest concentration was 0.5 mg/L in groundwater samples, with the same minimum concentration of 0.5 mg/L observed in cucumber samples. Across both high and low fluoride water areas, the highest dispersion was observed in water, whereas the lowest dispersion occurred in soil.

Figure 3(A) illustrates the distribution of fluoride in drinking water sources, identifying two sources that exceed the standard limit for fluoride concentration and two sources that fall below this limit. Figure 3(B) depicts the fluoride distribution in soil samples, while Fig. 3(C) shows the fluoride distribution in cultivated tomato samples. Figure 3(D) presents the fluoride distribution in cucumber samples, Fig. 3(E) displays the fluoride distribution in cultivated onion samples, and Fig. 3(F) illustrates the fluoride distribution in potato samples. The findings of this study indicate that the highest fluoride concentration in water was 4 mg/L, and the lowest was 0.3 mg/L. According to Iranian Standard 1053, the maximum allowable fluoride concentration for drinking water is 3 mg/L22.

Findings on the correlation of fluoride variables in water, vegetables and soil

Table 3 presents the correlation coefficients between variables in drinking water, food products, and soil within regions of high and low fluoride concentration. Spearman’s correlation coefficient revealed a significant direct relationship between fluoride concentration in soil and water (P = 0.021, R = 0.58), indicating that an increase in fluoride concentration in soil is associated with an increase in fluoride concentration in water. A significant direct relationship was also observed between water fluoride concentrations and fluoride levels in tomatoes (P = 0.004, R = 0.58), potatoes (P = 0.021, R = 0.58), onions (P = 0.001, R = 0.6), and cucumbers (P = 0.001, R = 0.8). This indicates that as fluoride concentration in water increases, the fluoride concentrations in tomatoes, potatoes, cucumbers, and onions also rise. Notably, the strength of the relationship between fluoride concentration in cucumbers and water was greater than that between water and other produce (tomatoes, potatoes, and onions). Additionally, the results indicated a direct and significant relationship between soil fluoride levels and the fluoride concentrations in tomatoes (R = 0.48), potatoes (R = 0.63), cucumbers (R = 0.4), and onions (R = 0.5).

Health risk assessment of fluoride in in water, vegetables and soil

Table 4 shows the fluoride concentration and fluoride exposure dose in food samples in areas with water fluoride concentrations above and below the standard for two age groups of children and adults. Based on these data, Water with 4 mg/L and Cucumber with 0.28 µg/kg had the highest and lowest fluoride concentrations and consequently EDI levels in vegetables, respectively. EDI through water and vegetable intake was higher in children than in adults.

Table 5 shows the total fluoride exposure dose and its HQ index. As mentioned earlier, the reference dose for fluoride exposure in this study was considered to be 60 µg/kg/day.

Evaluation of hazard generation risk by Monte Carlo simulation method

Risk simulations with high data repetition are commonly employed to address uncertainty in risk assessment and to calculate the cumulative probability of total risks across different age groups and exposure routes. In this study, the Monte Carlo simulation method was utilized due to the significant impact of influential parameters on the dispersion risk index34. The results of the Monte Carlo simulation, shown in Fig. 4, indicate that in areas where fluoride concentration reached 4 mg/L, the average Hazard Index (HI) for the child age group was 3.57, while for the adult age group, it was 2.37. These values indicate a risk for both children and adults. The 95th percentile values for the two groups were found to be 5.56 for children and 3.54 for adults. Conversely, in areas with a fluoride concentration of 0.3 mg/L, the mean HI for children and adults were 0.65 and 0.44, respectively.

Sensitivity analysis was conducted to identify the parameters that most significantly influence the output values of the non-carcinogenic risk model. The results for both age groups (children and adults) are presented in Fig. 5. The sensitivity analysis reveals that fluoride concentration has the most substantial positive effect on non-carcinogenic risk in both age groups, highlighting the need for careful monitoring and management of water quality changes.

Discussion

In this study, 26 samples of drinking water from wells in the region were analyzed to measure fluoride concentration during the dry and cold seasons of 2021. As shown in Fig. 2, the highest fluoride concentration in drinking water was found to be 4 mg/L, while the lowest was 0.3 mg/L. Approximately 88% of the water samples analyzed in the cold season and 80.7% of those analyzed in the dry season exceeded the WHO guideline standard level of 1.5 mg/L. Additionally, the average fluoride concentration in drinking water during the dry season (1.3 mg/L) was lower than that in the cold season (1.6 mg/L). The higher average fluoride levels in water sources during the cold season compared to the dry season may be attributed to increased water extraction from underground sources during the dry season, consistent with the findings of Keshavarz et al.32. It is crucial to focus on maintaining fluoride levels within the maximum and minimum standards to protect dental health. This variation may result from water interacting with minerals in rocks and soil that come into contact with groundwater35.

The studies conducted by Chakrabarty et al. in Assam, India, Bergamo et al. in Maringá, Brazil, and Yousefi et al. in the villages of Azerbaijan province reported fluoride levels within the standard range set by the World Health Organization, aligning with the results of this study36,37,38.

Table 2 presents the average concentration of fluoride in water, soil, and food products from the region. The table indicates that the average fluoride concentration in water is 3.8 mg/L, in soil is 110.5 mg/kg, and in tomatoes, onions, cucumbers, and potatoes from areas with high water fluoride levels is 2.38, 1.89, 0.39, and 1.9 µg/kg, respectively. In contrast, the average fluoride concentration in water from areas with low fluoride levels is 0.3 mg/L, in soil is 98.05 mg/kg, and in tomatoes, onions, cucumbers, and potatoes is 2.11, 1.29, 0.29, and 1.5 µg/kg, respectively. The results indicate that the average fluoride concentrations in soil and in tomatoes, onions, cucumbers, and potatoes from areas with high water fluoride levels are greater than those from areas with low fluoride levels.

In the study by Nagaraju et al., the lowest total soil fluoride concentration (6.7 mg/kg) was observed39, while Li et al. reported the highest total soil fluoride concentration in Gansu Province (542 mg/kg)40. Keshavarz et al. found fluoride concentrations in tomatoes, onions, and potatoes to be 1250, 1100, and 1330 µg/kg, respectively, which is consistent with the present study41.

The one-sample T-test indicated a significant relationship between the average fluoride levels in water and soil (Table 3). ANOVA revealed a significant difference between fluoride levels in water and soil, with higher average fluoride levels in tomatoes, cucumbers, potatoes, and onions from areas with high fluoride compared to those from low fluoride areas. The elevated fluoride concentrations in water samples and food products suggest that fluoride is absorbed by plants, likely due to the alkaline pH of the soil42.

Figure 3 illustrates the distribution of fluoride in drinking water sources, soil, tomatoes, cucumbers, potatoes, and onions. According to Table 4, the estimated daily intake (EDI) of fluoride through the consumption of water and food products was higher in children than in adults. Table 5 presents HQ values for fluoride in two age groups, indicating that HQ is more frequently reported in children than in adults. Moreover, in areas with high fluoride levels in drinking water, HQ was reported to be 13 times higher than in areas with low fluoride levels.

This study aligns with Keshavarz et al.‘s findings that HQ is higher in summer than in spring in Isfahan32, while Jha et al. reported that HQ due to the consumption of fluoridated vegetables and grains in children was 1.3743. A study conducted by Asgari et al. on fluoride risk assessment in groundwater sources showed HQ values of 0.36 for children and 0.29 for adults2. Additionally, Keshavarz et al. reported HQ values of 2.4 and 1.9 for children and adults, respectively, based on the consumption of water and vegetables32. Piyal et al. (2017) concluded that the combined effect of rice, legumes, and vegetables on the estimated cumulative daily intake (EDI) of fluoride for the study population ranged from 9.5 to 16%44. The present study is consistent with Ghosh’s findings45.

The Monte Carlo simulation results in Fig. 4 indicate that in areas with a fluoride concentration of 4 mg/L, HI in children was higher than in adults, suggesting risk in both groups. In areas with a fluoride concentration of 0.3 mg/L, the average HI for both children and adults was below 1. The sensitivity analysis in Fig. 5 demonstrates that fluoride concentration has the most significant positive effect on non-carcinogenic risk for both age groups, while BW has a negative effect.

This study showed a direct relationship between water fluoride levels and the fluoride content in tomatoes, cucumbers, and onions. The high fluoride concentrations in water and food are likely to result in significant fluoride absorption by residents, particularly children, in areas with high fluoride levels. Given the elevated fluoride concentrations in soil and plants, there is a substantial risk of transferring fluoride into the food chain.

The results indicate that fluoride concentrations for both age groups have a pronounced positive effect on non-carcinogenic risk, with body weight being the second most influential parameter in risk assessment. Moreover, the consumption of fluoride-containing water and food may increase health risks. Monte Carlo simulation results indicated that fluoride concentration in water significantly impacts non-carcinogenic risk. The calculated HQ values for fluoride in water were higher than those for food products, with HQ values being 13 times greater in areas with higher fluoride concentrations compared to areas with 0.3 mg/L fluoride content.

The sensitivity analysis revealed that fluoride concentration in both age groups has the greatest positive effect on non-carcinogenic risk. Therefore, health policymakers should avoid adding fluoride to water sources where concentrations exceed the standard, as dietary fluoride absorption is compensatory. There remains considerable confusion regarding the consumption of fluoridated water within the scientific community.

Despite the comprehensive nature of the investigation into fluoride concentrations in drinking water, soil, and food products in the rural areas of Hamedan, several limitations impacted the study’s findings and conclusions.

-

1.

Geographic Scope: The study focused exclusively on specific rural areas in Hamedan, which may not represent the fluoride concentration levels in urban regions or other rural areas in Iran. Therefore, the results might not be generalizable to other locations with different environmental or geological conditions.

-

2.

Sampling Size and Selection: While 26 wells and multiple vegetable samples were analyzed, the selection of sample sites was limited to accessible areas. This may have introduced sampling bias, as regions with extreme fluoride levels might have been overlooked due to logistical challenges or accessibility issues.

-

3.

Temporal Factor: The data was collected at a single point in time during the year 2021, which may not account for seasonal variations in fluoride levels. Fluoride concentrations in water, soil, and crops can fluctuate due to factors such as rainfall, agricultural practices, and seasonal crop cycles. A longitudinal study would provide a more comprehensive understanding of these variations.

-

4.

Methodological Constraints: Although the SPADNS method and standard ion-selective electrode method were employed for fluoride analysis, certain inherent limitations exist in these methods. For instance, matrix effects and interferences from other ions in the samples could potentially affect accuracy and precision.

-

5.

Health Risk Assessment: The Monte Carlo simulation, while a robust tool for risk assessment, is dependent on the quality and accuracy of the input data. The assumptions made during simulations related to exposure rates, dietary habits, and variability may not fully encapsulate the behaviors of the populations in the study areas.

-

6.

Lack of Long-term Health Data: While the study provided insights into potential health risks associated with fluoride exposure, it did not incorporate comprehensive health data from the population, making it difficult to correlate fluoride exposure levels with specific health outcomes, such as fluorosis incidence.

Conclusion

The findings of this study showed that the average fluoride concentration in areas with high fluoride levels was as follows: drinking water 3.5 ± 0.5 mg/L, and in tomatoes, onions, cucumbers and soil 2.38 ± 0.15 mg/kg, 1.89 ± 0.3 mg/kg and 110.5 ± 0.03 mg/kg respectively. In contrast, the area with low fluoride levels showed a concentration of 0.3 ± 0.1 mg/L in water and for tomatoes, onions, cucumbers and soil, the values were 11.0 ± 0.009 mg/kg, 1.29 ± 0.5 mg/kg, 0.05 ± 0.5 mg/kg, 0.05 ± 0.5 mg/kg and 98.05 ± 0.1 mg/kg respectively. 0.02 mg/kg. A direct relationship was observed between the fluoride content in water and the levels in tomatoes, cucumbers and onions. Based on the results obtained from the high fluoride concentration in soil and plants, the possibility of transferring this element to the food chain is very high. Due to excessive fluoride consumption, drinking water was the main source of fluoride intake in the study area. Therefore, to reduce non-communicable diseases, it is recommended to consume drinking water with low fluoride content. Or, for the defluoridation of drinking water, methods such as activated alumina and membrane filtration (reverse osmosis and electrodialysis) are suggested. In addition, people are advised to use foods containing calcium and vitamin C to reduce the risk of fluorosis, and children are advised to avoid using toothpastes and mouthwashes containing fluoride. It is suggested that the effect of fluoride concentration in drinking water on pathogenic factors (anemia during pregnancy, low birth weight, neurological problems, chronic cognitive impairment and dementia, thyroid hormone metabolism disorders, and infertility problems) be investigated based on the available information in two regions with low and high fluoride, the rural region of Hamadan.

Data availability

Data are available upon reasonable request from corresponding author.

References

Rohani, R. et al. Assessment of sodium silicofluoride as a fluoride source in drinking water systems. Iran. J. Chem. Chem. Eng. 2022(Articles in Press).

Asgari, G. et al. Monitoring and health risk assessment of fluoride in drinking water in Babol, Mazandaran Province, Iran. Desalination Water Treat. 165, 141–147 (2019).

Ghosh, G. & Mukhopadhyay, D. K. Human health hazards due to arsenic and fluoride contamination in drinking water and food chain. Groundwater development and management: issues and challenges in South Asia. :351 – 69. (2019).

Kabir, H., Gupta, A. K. & Tripathy, S. Fluoride and human health: Systematic appraisal of sources, exposures, metabolism, and toxicity. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50 (11), 1116–1193 (2020).

Malago, J., Makoba, E. & Muzuka AJaJOWS Engineering. Fluoride levels in surface and groundwater in Africa: a review. ;3(1):1–17. (2017).

Amouei, A. et al. fluoride concentration in potable groundwater in rural areas of khaf city, razavi khorasan province, northeastern iran (brief report). (2012).

Vithanage, M. & Bhattacharya, P. J. E. C. L. Fluoride in the environment: sources, distribution and defluoridation. ;13:131 – 47. (2015).

Shahab, S. et al. Effects of fluoride ion toxicity on animals, plants, and soil health: a review. ;50(4):393–408. (2017).

Ghale Askari, S. et al. Evaluation of heavy metal concentrations in black tea and infusions in Neyshabur City and estimating health risk to consumers. ;102(19):7928–7937. (2022).

Yousefi, M. et al. Distribution of fluoride contamination in drinking water resources and health risk assessment using geographic information system, Northwest Iran. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 107, 104408 (2019).

Srivastava, S. & Flora, S. J. C. E. H. R. Fluoride in drinking water and skeletal fluorosis: a review of the global impact. ;7:140-6. (2020).

Srivastava, S. & Flora, S. Fluoride in drinking water and skeletal fluorosis: a review of the global impact. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 7, 140–146 (2020).

Solanki, Y. S., Agarwal, M., Gupta, A., Gupta, S. & Shukla, P. Fluoride occurrences, health problems, detection, and remediation methods for drinking water: A comprehensive review. Sci. Total Environ. 807, 150601 (2022).

Onipe, T., Edokpayi, J. N. & Odiyo, J. O. A review on the potential sources and health implications of fluoride in groundwater of Sub-Saharan Africa. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part. A. 55 (9), 1078–1093 (2020).

Islam, M. S. & Mostafa, M. Meta-analysis and risk assessment of fluoride contamination in groundwater. Water Environ. Res. 93 (8), 1194–1216 (2021).

Adeyeye, O. A., Xiao, C., Zhang, Z., Yawe, A. S. & Liang, X. Groundwater fluoride chemistry and health risk assessment of multi-aquifers in Jilin Qianan, Northeastern China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 211, 111926 (2021).

Kerdoun, M. A. et al. Fluoride concentrations in drinking water and health risk assessment in the South of Algeria. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 128, 105086 (2022).

Yazıcı Karabulut, B., Derin, P., Demir Yetiş, A. & Yeşilnacar, M. İ. R. Health risk assessment in an area of dental fluorosis disease from high fluoride drinking water: a case study from southeastern Türkiye. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 34 (5), 2299–2314 (2024).

Yuan, L. et al. Health risk in children to fluoride exposure in a typical endemic fluorosis area on loess plateau, North China, in the last decade. Chemosphere 243, 125451 (2020).

Al Warawreh, A. M. et al. Prevalence of dental fluorosis among Southern Jordanian population. Int. J. Dent. 2020 (1), 8890004 (2020).

Kumar, S. et al. Dental fluorosis and associated risk factors in early adolescents in India. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health. 32 (4), 20170200 (2020).

Keramati, H. et al. Fluoride in Iranian drinking water resources: a systematic review, meta-analysis and non-carcinogenic risk assessment. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 188, 261–273 (2019).

Mridha, D. et al. Fluoride exposure and its potential health risk assessment in drinking water and staple food in the population from fluoride endemic regions of Bihar, India. Groundw. Sustainable Dev. 13, 100558 (2021).

Fallahzadeh, R. A. et al. Spatial distribution variation and probabilistic risk assessment of exposure to chromium in ground water supplies; a case study in the East of Iran. ;115:260–266. (2018).

Faraji, H. et al. Correlation between fluoride in drinking water and its levels in breast milk in Golestan Province. North. Iran. 43 (12), 1664 (2014).

Karampour, M., Halabian, A., Hosseini, A. & Mosapoor, M. J. T. Comparing the performance of fuzzy operators in the object-based image analysis and support vector machine kernel functions for the snow cover Estimation in Alvand mountain. Climatology A. 155 (3), 1729–1737 (2024).

Sepahi, A. A detailed study of morphology and chemistry of garnet crystals with suggestion of new subdivisions: data from pelitic schists, hornfelses and aplites of hamedan region, Iran. (2007).

Apha, A. Wef. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater Twenty (firsted) (Washington DC, USA). (2005).

Kitazume, T. & Yamazaki, T. Experimental Methods in Organic Fluorine Chemistry (Routledge, 2019).

Franzaring, J., Hrenn, H., Schumm, C., Klumpp, A. & Fangmeier, A. Environmental monitoring of fluoride emissions using precipitation, dust, plant and soil samples. Environ. Pollut. 144 (1), 158–165 (2006).

Lou, C. et al. Detection of trace fluoride in serum and urine by online membrane-based distillation coupled with ion chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A. 1500, 145–152 (2017).

Keshavarz, S., Ebrahimi, A. & Nikaeen, M. Fluoride exposure and its health risk assessment in drinking water and staple food in the population of Dayyer, Iran, in 2013. J. Educ. Health Promotion. 4 (1), 72 (2015).

Bazeli, J. et al. Health risk assessment techniques to evaluate non-carcinogenic human health risk due to fluoride, nitrite and nitrate using Monte Carlo simulation and sensitivity analysis in groundwater of Khaf County, Iran. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 102 (8), 1793–1813 (2022).

Ali, S. et al. Spatial analysis and probabilistic risk assessment of exposure to fluoride in drinking water using GIS and Monte Carlo simulation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. :1–10. (2022).

Mukherjee, I. & Singh, U. K. Groundwater fluoride contamination, probable release, and containment mechanisms: a review on Indian context. Environ. Geochem. Health. 40 (6), 2259–2301 (2018).

Chakrabarty, S. & Sarma, H. P. Fluoride, iron and nitrate contaminated drinking water in Kamrup district, Assam, India. Archives Appl. Sci. Res. 3 (4), 186–192 (2011).

Bergamo, E. T. P., Barbana, M., Terada, R. S. S., Cury, J. A. & Fujimaki, M. Fluoride concentrations in the water of Maringá, Brazil, considering the benefit/risk balance of caries and fluorosis. Brazilian Oral Res. 29, 1–6 (2015).

Yousefi, M., Mohammadi, A. A., Yaseri, M. & Mahvi, A. H. Epidemiology of drinking water fluoride and its contribution to fertility, infertility, and abortion: an ecological study in West Azerbaijan Province, Poldasht County, Iran. Fluoride 50 (3), 343–353 (2017).

Nagaraju, A., Thejaswi, A. & Aitkenhead-Peterson, J. J. J. O. T. G. S. O. I. Fluoride and heavy metal accumulation by vegetation in the fluoride affected area of Talupula, Anantapur district. Andhra Pradesh. 89, 27–32 (2017).

Li, Y. et al. Accumulation, interaction and fractionation of fluoride and cadmium in Sierozem and oilseed rape (Brassica Napus L.) in Northwest China. ;127:457–468. (2018).

Keshavarz, S., Ebrahimi, A., Nikaeen, M. J. J. O. E. & Promotion, H. Fluoride exposure and its health risk assessment in drinking water and staple food in the population of Dayyer, Iran, in 2013. ;4(1):72. (2015).

Battaleb-Looie, S., Moore, F., Malde, M. & Jacks, G. Fluoride in groundwater, dates and wheat: Estimated exposure dose in the population of Bushehr. Iran. J. Food Composition Anal. 29 (2), 94–99 (2013).

Jha, S., Nayak, A. & Sharma, Y. Site specific toxicological risk from fluoride exposure through ingestion of vegetables and cereal crops in Unnao district, Uttar Pradesh, India. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 74 (4), 940–946 (2011).

Bhattacharya, P. et al. Assessment of potential health risk of fluoride consumption through rice, pulses, and vegetables in addition to consumption of fluoride-contaminated drinking water of West Bengal, India. ;24:20300-14. (2017).

Ghosh, G., Mukhopadhyay, D. K. J. G. D., Issues, M. & Asia, C. I. S. Human health hazards due to arsenic and fluoride contamination in drinking water and food chain. :351 – 69. (2019).

Acknowledgements

This research was conducted with funding from the vice chancellery for research and technology at the Hamadan University of Medical Sciences (Grant No: 980217862).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.S., H.F., M.S.: conceptualization, supervision, software, methodology. H.F, A.S., B.A.: writing-review and editing. A.M., K.E.,N.K.: writing-original draft, data curation. H.F., M.S., A.S, K.E,.: investigation, visualization.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hamadan university of medical sciences. (Code No: IR.UMSHA.REC. 1398.019).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Asgari, G., salari, M., Seidmohammadi, A. et al. Investigation and risk assessment of fluoride concentration in drinking water, soil and food products in Hamedan rural areas. Sci Rep 15, 18458 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99462-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99462-2