Abstract

Organic-rich source rocks are not only crucial for hydrocarbon exploration and production but also serve as valuable archives of past environmental conditions. This study investigates the Upper Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) source rocks present in the Al-Lajoun Basin of central Jordan, to identify geochemical compositional variability corresponding to the paleo-environmental conditions during deposition. To this end, a multifaceted approach using Rock-Eval, SGR, XRD, XRF, ICP-OES, SEM-EDX, and thin-section petrography is utilized to understand bulk organic and inorganic geochemical proxies. Based on the results, the Jordan source rock is characterized as organic-rich, Type IIS kerogen, and thermally immature source rock, representing three distinct cycles of organic matter distribution. Cycle 1 is characterized as organic-rich carbonate mudstones with an average total organic carbon (TOC) content of 17 wt.%. This cycle represents high organic matter productivity, anoxic bottom water conditions, and episodic detrital influx (clays and detrital quartz). Cycle 2 is characterized as silica-rich mudstones to wackestones with an average TOC of 15 wt%. This cycle reflects a shift from carbonate-dominated to silica-dominated biota, likely driven by increased nutrient supply and changing climatic conditions. These conditions resulted in high bioproductivity and highly reducing anoxic/euxinic bottom water conditions during deposition. Cycle 3 represents foraminiferal wackestones to packstones with an average TOC of 12 wt.%. This cycle is characterized by a relatively high detrital sediment input, with comparatively low organic matter productivity and anoxic bottom water conditions. The identified organic and inorganic geochemical variability between these cycles implies changing climatic conditions over the open shelf setting, which in turn implies changes in ocean currents impacting the upwelling system of the Tethys margin. Understanding this relationship between ocean currents, climate, and the geochemical composition is crucial for efficiently exploring and exploiting organic-rich source rocks. A regional correlation of these cycles and their geochemical signatures could provide a powerful tool to trace ocean currents and associated climate change along the Tethys margin during the early Maastrichtian.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Organic-rich mudrocks serve as valuable archives of past environmental conditions and are critical for understanding the controls on organic matter accumulation and preservation. These source rocks deposited in environments that support high biological productivity (driven by factors such as ocean currents, climate, nutrient upwelling, and optimal sunlight) and coincide with low-oxygen bottom water conditions1. Such conditions allow organic matter to settle, accumulate, and later preserved on the seafloor. While marine conditions often facilitate organic matter accumulation, preservation is not limited to marine settings. In lacustrine systems, organic matter accumulation is further influenced by stratification and seasonal variation in oxygen levels2. Similarly, in terrestrial settings, organic matter can be retained in swamp and floodplain deposits where water saturation and rapid burial limit microbial degradation3. The interaction of organic matter with clays and carbonates, also play a crucial role in stabilizing organic material and reducing its susceptibility to microbial degradation4. Insights on the paleoenvironmental and depositional conditions of the organic matter can be gleaned through detailed organic and inorganic geochemical characterization5,6,7,8,9.

The Cretaceous Period stands out for its abundance of organic-rich rocks, partly due to high sea level and the related flooding of vast shelf areas, the occurrence of multiple ocean anoxic events (OEAs), ocean upwelling systems, and high organic-matter production rates10. One good example of organic-rich deposits of late Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) age are the Jordan source rocks (JSR), also known as Jordan Oil shales (JOS). These source rocks are present in the lower part of the Muwaqqar Chalk Marl (MCM) Formation and are amongst the richest source rocks around the globe11,12 (Fig. 1). However, these source rocks are thermally immature and have not produced hydrocarbons on an economic scale13.

The JSR has been the focus of several studies due to its high organic richness, shallow depths, and large areal occurrences across Jordan13,14,15,16,17. Numerous studies have been conducted to characterize these sequences as potential prospects for shale oil retorting16,18,19. Equivalent strata of Maastrichtian to Paleocene age have also been reported in other parts of the Eastern Mediterranean realm and are related to a large-scale upwelling system on the Southern margin of the Neo-Tethys Ocean during the late Cretaceous and early Paleogene time20,21,22,23. Despite variations in organic richness and thermal maturity across the Eastern Mediterranean region, these sequences show similarities in terms of organic and inorganic geochemical composition and hydrocarbon generation potential6,21,24,25. A key depositional control on the formation of source rocks is the interplay between global tectonics and sea-level fluctuations that have resulted in high-order cyclicity and compositional variability26,27,28,29. However, the factors governing these compositional heterogeneities within depositional cycles remain largely unexplored, leaving critical gaps in our understanding of their controls and implications. Consequently, the depositional environment, as well as the vertical and lateral variability in source rock quality, remains poorly constrained, particularly in the case of the JSR.

By integrating organic and inorganic geochemical data from a core covering the entire JSR sequence with detailed petrographic analyses, this study aims to unravel the geochemical cyclicity and compositional heterogeneity within the JSR. The findings provide critical insights into the depositional architecture, paleoenvironmental dynamics, and key controls on organic matter preservation. Beyond its implications for the JSR, this research enhances hydrocarbon exploration and unconventional resource assessment, particularly for similar depositional settings. A refined understanding of geochemical variability in organic-rich mudrocks improves predictive models of source rock quality, organic matter transformation, and hydrocarbon generation potential. Furthermore, the study contributes to the regional correlation of Maastrichtian source rocks, facilitating a more comprehensive framework for geochemical cyclicity and compositional variability across the Eastern Mediterranean.

Geological settings

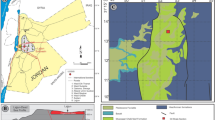

Jordan is located at the north-western margin of the Arabian Plate, which is separated from the African Plate along a left lateral transform fault system and includes areas of Aqaba, the Dead Sea, and the Jordan Rift Valley (Figs. 1a and b). During the Late Cretaceous to the Eocene, Jordan was located on a shallow shelf at the southern margin of the Neo-Tethys Ocean and is represented by two major lithostratigraphic groups, namely, the Ajlun Group and the Belqa Group30 (Fig. 1b). The Ajlun Group is late Albian to early Coniacian in age and comprises lithofacies that are mainly associated with fluvial siliciclastic and marine carbonates and evaporites30. The Belqa Group was deposited during the late Coniacian to early Lutetian time and mostly consists of sandstones, limestones, chalk marl, cherts, phosphorites, coquina limestones, and bituminous marls27,31,32. The Belqa Group comprises the following six formations, from bottom to top they are: Wadi Umm Ghudran (WG), Amman Silicified Limestone (ASL), Al Hisa Phosphorite (AHP), Muwaqqar Chalk Marl (MCM), Umm Rijam Chert (URC), and Wadi Shallala Chalk (WSC). The focus of the present study is on the Maastrichtian-aged Muwaqqar Chalk Marl (MCM) Formation. The MCM Formation is subdivided into three main units. The lower unit of MCM is composed of organic-rich carbonate mudstones, which are also referred as the JSR interval. This organic-rich interval characterizes intense surface water marine algal productivity and deposition under reducing conditions, resulting in significant organic matter preservation33,34. The total organic carbon (TOC) content of this unit can reach up to 25 wt% in places12,17,20. The middle unit of the MCM consists of chalk and bituminous marl. The upper unit of the MCM Formation consists of light yellowish chalk intercalated with black chert beds28,31.

The JSR occurs in the shallow subsurface in central Jordan and outcrops in several surrounding locations (Fig. 1). These source rocks extend beneath approximately 60% of Jordanian territory and rank among the richest organic-rich deposits worldwide35. Despite the immature nature of JSR, it provides a unique opportunity to examine vertical and lateral compositional heterogeneities within an anoxic depositional system, offering critical insights into source rock development and geochemical variability during deposition.

Maps showing (a) the depositional facies of the Arabian plate during the late Cretaceous to early Paleogene36 and (b) the present-day geological map of Jordan with the location of the drilled well (c) A lithostratigraphic column highlighting the JSR interval in the MCM Formation of the Belqa group, which is present in the Al-Lajjun basin of central Jordan30.

Samples and methods

To investigate the organic and inorganic geochemical composition and variability of the JSR, a vertical subsurface cored well was drilled in the Al-Lajjun region of central Jordan (Fig. 1b). The well was drilled by MinXperts drilling company in Jordan, funded by King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST), where the recovered core was transported to KAUST with the support of the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources (MEMR), Jordan. The total depth of the well is 72 m, with a top 24-m cutting interval and an underlying 48-m core interval. Bulk organic and inorganic geochemical analyses were performed using Spectral Gamma Ray (SGR), Rock-Eval pyrolysis, X-ray diffraction (XRD), X-ray fluorescence (XRF), and Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectroscopy (ICP-OES) to identify compositions and distributions within the section. Detailed petrographic analyses using thin sections and Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) combined with Energy Dispersive X-ray analysis (EDX) were conducted to understand the variation in lithotypes and to observe the distribution of organic matter in association with the inorganic geochemical components of the section on the micro to nanoscale. The core profile, the analytical methods, and selected sample locations in the drilled well are shown in Fig. 2. The methodology of each of these techniques is discussed in detail below.

Spectral gamma ray (SGR) data

The SGR data was collected at KAUST from the entire core interval (from 24 m to 71 m) at 0.25-m intervals, using an RS-230 gamma-ray spectrometer (Radiation Solution). The detector was calibrated to ensure a proportional relationship between the measured counts and the concentrations of potassium (K; %), uranium (U; ppm), and thorium (Th; ppm), which were converted by the spectrometer into a TGR count signal (SGR-TC). The SGR-TC signal values were subsequently converted to API units using the empirical formula GR (API) = 4Th (ppm) + 8U (ppm) + 16 K (%)37.

Bulk organic geochemical analyses

The bulk organic geochemical analysis on the cored well was performed at KAUST with 1.5-m sample intervals for the initial 20-m depth and at 0.5-m intervals for the remaining core (total 117 samples), using a Rock-Eval 7 S instrument (Vinci Technologies). The experimental approach employed established procedures38,39.The sample locations are shown in Fig. 2. To ensure the reliability and precision of the results, an IFPEN-160 K standard sample was included after every 10 samples, with a duplicate sample taken every 20 samples. The key results obtained from RockEval 7 S include Total Organic Content (TOC in wt%), S1 (free hydrocarbons in mg/grock), S2 (thermally cracked hydrocarbons in mg/grock), S3 (CO2 released in mg/grock), Tmax (thermal maturity parameter in °C), HI (Hydrogen index), OI (Oxygen Index), PI (Production Index), TSorg (Total Organic Sulfur in wt%), TSinorg (Total Inorganic Sulfur in wt%), Total S (Total sulfur in wt%).

The biostratigraphic age, spectral gamma-ray (SGR) profile, and sample locations used for the analysis of the JSR interval in the drilled well40.

Inorganic geochemical (XRD, XRF, and ICP-OES) analysis

Based on the bulk organic geochemical results, a subset of 28 samples was selected to effectively capture the mineralogical and elemental composition of the section (for sample location, see Fig. 2). To analyze the mineralogical composition, a D8 Advance P-XRD instrument (Bruker Technologies) equipped with Cu-Kα radiation (λ = 1.54Å) and a LynxEye detector was used at a current of 40 mA and a voltage 40 kV in the Imaging and Characterization Core Laboratory at KAUST. Homogenized powdered samples with a grain size ranging from 1 to 10 µm were used to identify the primary mineralogical components in the selected samples. The obtained diffractograms were scanned within the 2θ angular range of 5–70°, with a step size of 0.10’’. The diffraction patterns were identified by matching them with the International Centre for Diffraction Data (ICDD) PDF library.

For the major and minor elemental analyses, a wavelength-dispersive S8 TIGER Series 2 XRF spectrometer (Bruker Technologies) was used in the Imaging and Characterization Core Laboratory at KAUST. To enhance the accuracy, the powdered samples were compacted into 34-mm diameter pellets before placing them in the sample holder for analysis. After the analysis, the in-build XRF software was used to calculate the concentation of all the major and minor elements.

For trace element analyses, an ICP-OES equipment (Agilent Technologies) was used at KAUST. Prior to analysis, the samples were digested in HNO3:HCl (3:1) for the carbonate-rich samples, and HNO3:HF (3:0.5) for the silica-rich samples, using Ultrawave-2 (UltraWave) equipment. After complete digestion, the samples were injected into an ICP-OES instrument along with the standards for estimating the trace metals concentration.

Petrographic analysis

For the petrographic analysis, plug samples were taken for thin-section microscopy, and plug samples for SEM-EDX spectroscopy. These samples were selected to represent the significant variations in source rock composition and organic matter distribution in the JSR. The sample locations for the thin section and SEM are shown in Fig. 2. Thin sections were studied under a LEICA DM 750P polarizing light microscope at 2.5x, 4x, and 10x magnification. The petrographic description includes different types of grains, matrix, lamination, interparticle and intraparticle porosity, fractures, and diagenetic features. Based on the macroscale and microscale observations, the thin sections were then classified using the guidelines proposed in the literature41,42.

For SEM analysis, the samples were first polished and coated with titanium to enhance the resolution and quality of the images. The samples were then analyzed via FE-SEM (TESCAN) along with EDS (OXFORD) at KAUST) to obtain high-resolution secondary electron (SE) and backscattered electron (BSE) images and elemental compositions of the samples at various resolutions.

Results and interpretation

Spectral gamma ray distribution (SGR)

The SGR profile is presented, along with the concentration profiles of U, Th, and K, in Fig. 3, whereas the overall data obtained is shown in Supplementary Table 1. The SGR profile is closely tracked by the U concentration, thus suggesting a strong influence of this element on the SGR variation, with Th and K having little or no role (Fig. 3b). A prominent feature of the profile is the very high SGR response at the bottom of the core, specifically between 63 and 72 m depth, which is also reflected in the higher concentration of U. This abnormally high SGR signal is attributed to the presence of phosphorites (which are known to have strong affinity for U) associated with the underlying AHP Formation43. The overlying lower SGR response (from 21 to 63 m depth) corresponds to the JSR interval present in the lower part of the MCM Formation and shows significant variability ranging from 20 to 90 counts.

Bulk organic geochemistry; TOC, TS, and kerogen type

The bulk organic geochemical distribution for the studied well is presented in Fig. 4, with detailed RockEval data provided in Supplementary Table 2. The TOC and associated bulk geochemical properties vary significantly throughout the core. Within the JSR interval (from 24 to 63 m), the TOC values range from 2 wt% to 22 wt%, with an average of 14 wt%. In contrast, the AHP interval (63 to 71 m), shows relatively lower TOC values, ranging from 0.1 wt% to 14 wt%, with an average of 6 wt%. Similarly, the hydrogen index (HI) also varies between the two intervals. The JSR consistently exhibits high HI values with low variability (822–894 mgHC/gTOC), averaging 843 mgHC/gTOC. In comparison, the AHP interval displays relatively lower HI values with greater variability (515–835 mgHC/gTOC), averaging 740 mgHC/gTOC. The oxygen index (OI) further distinguishes the two intervals, with the JSR exhibiting low OI values (14–57 mgCO2/gTOC) with an average of 26 mgCO2/gTOC, whereas the AHP shows a broader OI range (13–298 mgCO2/gTOC) with an average of 50 mgCO2/gTOC. These geochemical trends indicate the presence of high-quality and well-preserved organic matter in JSR, whereas the AHP, despite containing good-quality organic matter, exhibits a lower preservation and higher oxidation compared to AHP, where the organic matter is of good quality but more oxidized.

The SGR and bulk organic geochemical property distributions of JSR highlightning the identified cyclicity with corresponding biostratigraphic ages40 in the drilled well.

The TOC, S2, and sulfur distributions in the drilled well are remarkably similar, as shown in Fig. 5, thus suggesting a strong covariation of organic content, quality, and sulfur content within the JSR. The distribution of these parameters also reveals the presence of three distinctive cycles in the JSR, which are referred to as Cycles 1–3 (Fig. 4). These cycles also show distinct patterns in the SGR but not as prominent as in other geochemical parameters across the JSR interval. Cycle 1 (Cy-1) spans from 49 to 62.5 m depth and has TOC and TS values of 10.55–22.19% and 2.74–4.95%, respectively. Cycle 2 (Cy-2) covers the depth interval of 37–49 m, with TOC and TS ranges of 6.32–19.92% and 1.67–4.98%, respectively. Cycle 3 (Cy-3) extends from 24 to 37 m depth, with TOC and TS ranges of 2.38–17.32% and 0.67–4.35%, respectively.

To gain deeper insight into the organic geochemical characteristics of the JSR and AHP intervals in the core, both units were classified using a widely accepted petroleum source rock classification system44. The JSR interval is characterized as an excellent source rock due to its consistently high TOC and HI values (Fig. 5a). Although the AHP interval exhibits slightly lower TOC and HI values compared to JSR, it still qualifies as a good-excellent source rock, indicating its potential for hydrocarbon generation. In terms of thermal maturity, both the JSR and AHP intervals display low Tmax temperatures (< 415 °C) and low production index (PI) values (< 0.05), confirming that these intervals are thermally immature (Fig. 5b). The modified van Krevelen diagram (Fig. 5c) further classifies both JSR and AHP as mixed Type I–II kerogens (highly oil prone), with a strong potential for liquid hydrocarbon generation upon maturation. Additionally, the calculated Sulfur Index (SI) places both intervals within the Type IIS kerogen category (Fig. 5d), suggesting hydrocarbon generation at lower thermal maturity levels compared to typical Type II or Type I kerogens. Interestingly, despite variations in TOC and HI values between the JSR and AHP, the organic matter type and thermal maturity remain relatively uniform. This consistency suggests that the observed geochemical cycles are not driven by changes in organic matter type, quality, or maturation, but rather by depositional conditions controlling their distribution and preservation.

Mineralogical characterization

The mineralogical composition of the JSR interval, as determined through XRD analysis, is predominantly carbonate-rich, with calcite as the primary mineral and occasional occurrences of dolomite. Minor amounts of clay minerals and varying quartz content are also present (Fig. 6). The calcite content varies significantly, ranging from 20 to 80%, while silicates, the second most abundant mineral group, constitute 5–20%, with localized zones reaching up to 56%. These silicate-rich zones are primarily composed of quartz and opal cristobalite-tridymite (CT). The clay content is relatively low, fluctuating between 1% and 6%, with kaolinite being the dominant clay mineral. The phosphate mineral fluorapatite varies considerably, ranging between 2% and 12%. Other minor minerals include gypsum (1–10%), pyrite (1–10%), and sphalerite (1–5%). A comprehensive dataset from the XRD analysis is provided in Supplementary Table 3.

The mineralogical variability across the previously identified geochemical cycles, also reveals distinct patterns. Cycles 1 and 3 are characterized by dominant carbonate mineralogy, averaging around 70%, with relatively low silicate content (10–20%) and minor but variable clay concentrations (< 5%). An anomaly at 58.5 m depth is observed, marked by a slight increase in quartz and clay content and a corresponding decrease in calcite concentrations, coinciding with an abrupt drop in TOC. This shift likely represents a short-lived detrital influx event, potentially linked to episodic sedimentation changes. In contrast, Cycle 2 exhibits a pronounced increase in silicate content (6–56%), primarily due to the presence of opal CT, while carbonate concentrations vary between 20% and 60% and clay remains relatively low (< 4%). The presence of opal CT suggests the recrystallization of biogenic silica (originally in the form of amorphous opal, or opal A) derived from silica-secreting microorganisms, such as diatoms and radiolarians43,45.

Major and minor elemental characterization

The major and minor elemental composition of the studied section, as determined by XRF analysis, aligns well with the observed mineralogical variations. The complete dataset detailing the elemental composition is provided in Supplementary Table 4, while ternary plots (Fig. 7) illustrate the key geochemical trends and variability. The Al₂O₃-CaO-SiO₂ ternary plot (Fig. 7a) reveals a system dominated by high CaO concentrations, reflecting the prevalence of carbonate minerals. However, variations in Al₂O₃ and SiO₂ suggest contributions from clays and quartz. Within the JSR interval, Cycles 3 and most of Cycle 1 follow a mixing trend between carbonate and aluminosilicate detrital inputs. In contrast, Cycle 2 exhibits anomalously high SiO₂, corresponding to the presence of biogenic silica. The CaO-SiO₂-P₂O₅ ternary plot (Fig. 7b) highlights the significant presence of phosphate (up to 10%) in all samples, with a particularly higher concentration in the AHP interval. This enrichment suggests enhanced phosphogenesis, likely influenced by episodic upwelling conditions, high biological productivity, and organic matter degradation during deposition46.

Trace elemental characterization

The trace elemental data acquired for compositional analysis also serve as a proxy for identifying the prominent environmental and depositional conditions during organic matter accumulation. The overall dataset obtained is provided in Supplementary Table 5. Among these, trace elements such as Ni, Cu, Zn, Cr, Cd, Mo, U, and V are often associated with higher TOC and TS sediments and are thought to be primarily controlled by both reduction-oxidation (REDOX) conditions and sequestration by organic matter and sulfur to varying degrees5,47,48,49. Ni and Cu (and to a lesser degree Zn and Cr) often show strong correlations with TOC and TS and are commonly used as proxies for organic matter input and productivity in sediments5,45. Meanwhile, U and V are generally accepted as REDOX indicators and are found to be enriched in low-oxygen (dysoxic and anoxic) settings, while Mo and Cd are also REDOX indicators but are often found to be enriched in sulfidic (euxinic) settings where there is free H2S in the water column as well as in sediment pore spaces50,51. The enrichment factors (EFs) of selected elements in the JSR cycles and AHP Formation, as compared to those of modern upwelling systems, Sapropels, and Cretaceous black shales are shown in Fig. 8. The EF for each metal is calculated by normalizing the total metal to Al and then comparing the metal/Al ratio to that of the average shale to account for the contributions from detrital input5,51. Both the JSR cycles and the AHP are anomalously enriched in P, Zn, Cr, Mo, U, and Cd, and moderately enriched in Ni, Cu, and V. To further assess these key paleoenvironmental conditions, the elemental proxies as EFs are divided into the following 3 categories: (i) organic matter dilution, (ii) paleo-productivity, and (iii) paleo-redox conditions.

A comparison of the enrichment factor (EF) values of the dominant elemental proxies for the JSR and AHP with those of source rocks with different origins. The EF is calculated based on Brumsack (2006) formula52. Any relative enrichment is expressed as EF > 1, while relative depltion by EF < 1.

Detrital influx/dilution

To account for the influence of detrital sediment input, elemental data are commonly normalized to Si, Al, and Ti due to their association with the detrital quartz and aluminosilicate fraction of sediments5,53,54,55.However, Si can also be enriched through the input from siliceous tests of marine algae such as diatoms and radiolarians, thus resulting in an excess non-detrital (biogenic) Si component. This excess is validated by the cross-plots of Ti vs. Al and Ti vs. Si in Fig. 9, which show a strong positive correlation between Ti and Al, but a poorer negative correlation, along with significant deviations from the regression line, for Ti and Si. Thus, both Al and Ti indicate a primary detrital aluminosilicate origin and are valid elements for normalization to derive geochemical proxies.

The variations in major, minor, and trace elements (as wt.% or ppm and as normalized to Al) for the JSR cycles are shown in Fig. 10. Here, the JSR interval shows an overall low Al content (2–8%), with elevated values at the bottom and top of the section. This may suggest a large scale sea-level or climate change, leading to variations in the overall detrital influx into the basin. The detrital dilution is not the only influence on organic matter in sediments. The inputs of biogenic sediments (both siliceous and carbonate) during periods of high productivity can also lead to dilution, thus resulting in lower overall organic matter concentrations56. The relationship between the TOC and inorganic components in the JSR interval can be seen in Fig. 11. The main non-carbonate detrital contribution to the sediment is in the form of clays and detrital quartz, which are shown using Al and Si as proxies (Fig. 11a and b). The combined %Si + Al fraction plotted against %Ca indicates that the dilution of carbonates in the JSR (especially in Cycles 1 and 3) by detrital minerals mostly ranges from around 10–20%. Cycle 2 indicates a significantly lower overall carbonate content, and the dilution is primarily attributed to the addition of biogenic silica to the %Si + Al fraction. The influence of the inorganic components on the organic matter fraction in the JSR interval is shown in the cross-plots between TOC vs. Al and TOC vs. Ca and Si normalized to Al-content in Fig. 11c and d. Here, Cycle 1 exhibits a strong positive correlation between Ca/Al and TOC, but a poor one with Si/Al. This suggests a coupled increase in both carbonate productivity and organic matter concentration, along with a negative effect of siliciclastic dilution on the latter. By contrast, Cycles 2 and 3 show poor correlations between Ca/Al and Si/Al and TOC, thus suggesting that dilution by a siliciclastic detrital fraction cannot simply explain the variation in the amount of organic matter in these cycles.

Paleoproductivity

The high amounts of organic carbon (10–20%) and its consistently high HI values (800–900 mg HC/gTOC) are strong evidence of high marine algal productivity in the JSR section. In addition, the TOC is closely associated with trace metals such as Ni, Cu, and Zn, which are commonly used as geochemical proxies for productivity57,58,59. It is postulated to be taken up by marine algae and subsequently transported and incorporated into sediments where the organic matter is preserved due to low oxygen conditions50,60.

The JSR interval in Jordan is reported to contain high trace element concentrations20,45,51, as corroborated by this study. The concentration profiles (as ppm metals) show a strong correspondence with the paleo-productivity proxies and the TOC profile (Fig. 10). The trace elements (especially Ni and Cu) exhibit a high degree of correlation with TOC, for the whole section and for each cycle (Fig. 12). The absolute concentrations of Ni, Cu, and Zn are all above typical background shale values, and the strong correlation with the TOC suggests that the bulk of these metals are closely associated with the organic fraction. Small and consistent differences between the cycles suggest that other factors, such as redox or availability of S, as well as varied clastic input, may also have played a minor role.

The presence of significant amounts of P has been previously noted for the JSR on a regional scale. It is indicative of high productivity driven by upwelling in the southern marine platform of the Tethyan margin, and specifically in the Jordan region20,30. While the AHP Formation is noted for its exceptionally high P contents and is designated as a source for phosphorite mining, all the three identified cycles of the JSR interval are also very rich in this element (~ 2–5%), with EF values > 100, and Corg/P ratios (~ 5–23). The P cycle in such settings is complex. Bioavailable P is taken up by primary producers and transported to the sediment-water interface if the organic matter is not oxidized. However, its transport and release from productive surface waters to the sediment-water interface is also controlled by the presence of Mn and Fe oxyhydroxides, which are strongly affected by redox conditions60,61. The elevated EFs and low Corg/P for the JSR in a highly reducing setting is surprising, as anoxia generally promotes dissolution of P-transporting phases and effectively remobilizes P into the water column. Algeo and Ingall62 have demonstrated that detrital P is almost always a very minor component of marine sediments, hence the bulk of the P found in the JSR interval is likely to be authigenic. Possible explanations for the high P contents (especially relative to the TOC) are precipitation as authigenic mineral phases (fluorapatite, authigenic Fe-phosphates) and preservation as fecal pellets and fishbone material. The latter are found in abundance in the AHP Formation and in the JSR observed in SEM images. Consequently, the high amount of P in the JSR section and its mimicking of the TOC profile can be interpreted as indicative of a high productivity setting.

Paleoredox

Molybdenum (Mo), vanadium (V), and uranium (U) serve as established geochemical proxies for reconstructing bottom-water redox conditions during organic matter preservation5,57,59. The distribution profiles of these elements (as metal concentrations) and its normalization to Al content are shown in Fig. 10. Here, all three elements are highly enriched in the JSR interval compared to normal background average shale values (Post-Archean Australian Shale-PAAS)52. In Cycle 1, these proxies exhibit a significant decrease at approximately 58.5 m depth, which coincides with a similar decrease in other geochemical proxies, potentially reflecting a short-lived detrital event. Apart from this episode, highly reducing conditions appear to persist overall in Cycles 1 and 2, with Cycle 2 showing significant enrichments of Mo, along with V and U. Such pronounced Mo enrichment has been associated with highly sulfidic (euxinic) conditions50,63,64,65. Based on the threshold values proposed by Scott and Lyons64 and the EF model proposed by Algeo and Tribovillard66, Cycles 1 and 2 have high Mo concentrations (50–180 ppm), thus suggesting euxinic to periodic euxinic conditions in the water column (Fig. 13). In contrast, Cycle 3 has relatively lower Mo concentrations (23–60 ppm) and is more likely to have had anoxia to periodic euxinia in the water column during deposition of the organic matter.

Plot of U-EF vs. Mo-EF for the three JSR cycles. The diagonal dotted black lines represent the Mo/U molar ratio in seawater (SW)66.

Thin section petrography

Thin section (TS) sections were produced from plugs taken from different depth intervals to showcase significant petrographic heterogeneities starting from the AHP Formation and across the JSR interval, and were numbered consecutively from bottom to top of the section. Thus, TS-01 was taken from a depth of 64.5 m and marks the transition between the underlying AHP Formation and the JSR interval. Based on Dunham’s classification41, this thin section can be categorized as phosphatic packstone to grainstone due to its distinctive texture, which consists mainly of phosphatic peloids, phosphatic ooid grains, fish fragments, foraminifera, and lithoclasts (Fig. 14a). Calcite and apatite are the most common minerals, with poorly sorted grains embedded in a brownish, organic-rich matrix. This thin section shows strong bioturbation is significantly bioturbated and has an estimated TOC of 6.5 wt%.

Thin sections TS-02 and TS-03 were obtained from depths of 55.5 and 50.0 m, having TOC of 18.8 and 19.5 wt%, respectively (Fig. 14b-c). Both thin sections can be classified as organic-rich carbonate mudstones and represent Cycle 1 of the JSR interval. These facies are characterized by a light to dark brown mud matrix containing a relatively low grain fraction (5–15%). The grain assemblage is dominated by well-preserved foraminifera shells, with occasional occurrences of phosphatized bone fragments (up to 5 mm) and bivalve fragments. The dark brown organic matter primarily fills in the fossil chambers, but is also observed as part of the matrix. Notably, no visible porosity or microfractures are observed in either of these two thin sections.

Thin sections TS-04, TS-05, and TS-06 correspond to depths of 46, 43, and 39.5 m, with TOC values ranging from 12.1 wt% to 17.6 wt% respectively, and represent Cycle 2 of the JSR interval (Fig. 14d–f). These thin sections are classified as silica-rich mudstones to wackestones. This categorization reflects a significantly higher grain density (up to 50%) and dominant silicate mineralogy (particularly intragranular Opal CT cement). The primary grain components are well-preserved planktonic and benthic foraminifera with some bivalve fragments. Notably, the chambers of these biogenic grains are partially filled with cement (either quartz or calcite). Organic matter appears as brownish-hued elliptical/lenticular-shaped lenses concentrated within the matrix but also partially or entirely fills the fossil chambers. Similarly to previous TS-01, -02, and − 03, no visible porosity or fractures are observed in TS-04, TS-05, and TS-06.

Thin sections TS-07, TS-08, and TS-09 were retrieved from depths of 35, 30, and 25.5 m, with TOC values of 12, 14.7, and 9.2 wt%, respectively, representing Cycle 3 of the JSR interval (Fig. 14g–i). These thin sections are classified as “Foraminifera wackestone to packstone” and exhibit relatively lower TOC values compared to cycles 1 & 2 of the JSR section. This classification reflects a higher grain density (exceeding 50%), with foraminifera fossils being the dominant grain component. Occasional occurrences of other biogenic grains, such as bivalve fragments and fish remains, are also observed. The biogenic grains are primarily filled with calcite cement. In contrast to cycles 1 & 2, the organic matter distribution is found mostly concentrated in the matrix with minimal occurrences inside the fossil chambers.

Scanning electron microscopy with energy dispersive X-ray (SEM-EDX) analysis

To further highlight the compositional and textural heterogeneity and to understand the distribution of organic matter, a selected sample from each cycle was subjected to a detailed SEM-EDX analysis. The results obtained for a sample from Cycle 1 (depth = 53 m), representing an organic-rich zone with a 19 wt.% TOC content, are presented in Fig. 15. This SEM sample exhibits a heterogeneous composition with distinct biogenic grains and matrix (Fig. 15a and b). The biogenic grains are mainly composed of calcite and phosphate minerals and exhibit well-preserved original structures with only occasional fractures (Fig. 15a). The carbonate-dominated grains also display well-preserved microporosity, which is mostly filled with organic matter. The latter is discernible by a darker grey hue in Fig. 15c and characterized by elevated C and S contents in the EDX results (Fig. 15e). The high-resolution image in Fig. 15d also reveals the presence of organic matter in the matrix, showing an amorphous structure surrounding the grain particles. Besides this, the matrix is dominated by very fine Si-rich and Ca-rich particles (Fig. 15d). Pyrite is also found in pore spaces alongside the organic matter, appearing as small framboidal grains (Fig. 15c, d). Pyrite formation is primarily driven by microbial sulfate reduction (MSR), where sulfate-reducing bacteria convert sulfate into hydrogen sulfide (H₂S), which then reacts with iron to form pyrite (FeS₂)67.

The SEM-EDX results for a sample from Cycle 2 (taken from a depth of 43 m) are shown in Fig. 16. This also corresponds to an organic-rich interval with an 18% TOC content. The biogenic grain type and matrix texture of this sample resembles that of Cycle 1 but with a significant increase in the Si content. This silica enrichment manifests primarily as cement, which is present in the biogenic fossil chambers but also in the surrounding matrix (Fig. 16a). The silica cement is interpreted to be of biogenic origin through the recrystallization of amorphous opaline-silica originating from diatoms and radiolarians68. The biogenic grains are primarily composed of calcite and apatite, with occasional dolomite occurrences and small nodular/framboidal pyrite (Fig. 16a, b). Notably, the organic matter present within the fossil chamber co-occurs with the opal CT cement (Fig. 16a, b), however, it is also present in the matrix (Fig. 16b-d). Furthermore, a high concentration of Zinc sulfide (ZnS) due to elevated Zn and S concentration, is observed alongside organic matter in the fossil chamber (Fig. 16a, b). The presence of ZnS within the fossil chamber represents highly reducing/euxinic bottom water conditions, where hydrogen sulfide (H₂S), in the absence of iron (Fe), reacts with dissolved Zn²⁺, leading to ZnS precipitation69,70. The presence of some clay particles is also observed through elevated Al and K signatures in the SEM-EDX results (Fig. 16b, d,e).

The SEM-EDX analysis of a sample from Cycle 3 is presented in Fig. 17. This sample was retrieved from a depth of 33 m and exhibits a lower TOC content (9%) compared to Cycles 1 and 2. Hence, this sample provides an opportunity to examine the effects of varying organic richness on the organic matter distribution. As with the Cycle 1 sample, the biogenic grains of the Cycle 3 sample are primarily composed of calcite and apatite, albeit with a higher grain density and a greater number of broken shells/fragments (Fig. 17a). Notably, the intraparticle porosity (fossil chambers) that was filled with organic matter in Cycles 1 and 2 is either empty or filled with calcite/dolomite cement in Cycle 3. (Fig. 17a, b). The dolomite mostly occurs as a diagenetic alteration of the calcite grains with a similar grain texture to that of calcite; however, it is also observed as individual rhombohedral crystal grains (Fig. 17b, c). Alongside the dolomite, a higher clay content is revealed by the elevated Al, K, Si, and O concentrations (Fig. 17b, d). The organic matter distribution in this sample is mostly concentrated in the matrix, surrounding the grain particles with an elliptical to sub-elliptical shape and filling in the interparticle pore spaces (Fig. 17d).

Discussion

The geochemical and petrographic data from the Maastrichtian organic-rich carbonate source rocks of the MCM Formation in central Jordan reveal a complex depositional history characterized by cyclic variations in organic matter preservation, mineralogical composition, and redox conditions. These geochemical cycles reflect the dynamic interplay of climatic fluctuations, sea-level changes, and sedimentary processes, which collectively influenced the distribution and quality of organic matter. Key factors governing these geochemical variations, assess their implications for hydrocarbon generation potential, and explore their significance in a broader regional stratigraphic and paleoenvironmental context are discussed in detail.

Depositional setting

Contrary to the common perception of relatively stagnant depositional conditions in deep pelagic settings, the JSR interval is proposed to have been deposited under more dynamic conditions in a shallow shelf environment. This depositional setting was likely influenced by a combination of climatic fluctuations, sea-level changes, and localized sedimentary dynamics that created a highly variable geochemical environment, resulting in extreme geochemical signatures45,71 (Fig. 10). The geochemical proxies in the JSR reflecting such paleodepositional conditions and compared with source rocks of different origins are shown in Fig. 18. The paleoenvironmental reconstitution, supported by elemental geochemical data, suggests that JSR deposition occurred in a highly bio-productive system driven by sustained nutrient upwelling along the southern margin of the Neo-Tethys. This upwelling facilitated high primary productivity, which combined with restricted bottom-water circulation, contributed to organic-rich sediment accumulation under anoxic to euxinic conditions. Similar examples of source rocks with variable but relatively high organic matter and high trace metal enrichments include the siliciclastic Paleozoic black shales72, the siliciclastic Eocene black shale succession from the central Arctic Lomonosov Ridge73, and the carbonate Toarcian black shales of the Posidonia Shale Formation in the Dutch Central Graben74. These formations share key geochemical and mineralogical proxies indicative of deposition under relatively high-energy, nutrient-rich shallow marine conditions.

Age, duration, and characteristics of depositional cycles

The identified JSR cycles can be dated by nannofossil biozones (UC 16b, 17, 18, and 19)40 (Fig. 4). The nannofossil biostratigraphy suggests deposition between 72.2 and 68.8 Ma, with cycle durations of 0.9 to 1.3 Ma and an overall rate of deposition of 12 m/Ma40. The age dating classifies these cycles as third-order depositional sequences, nested within a second-order transgressive phase26,56,75. Each cycle reflects unique variations in organic matter enrichment, mineral assemblages, and depositional dynamics, driven by fluctuations in primary productivity, redox conditions, and sediment supply mechanisms (Fig. 19).

Cycle 1, spanning 1.13 Ma with a thickness of 13.5 m and a sedimentation rate of 13.3 m/Ma, is characterized by high carbonate content and very high TOC levels, classifying it as an organic-rich carbonate mudstone facies. The depositional conditions during this cycle remained relatively stable, with sustained high organic matter productivity and predominantly euxinic bottom waters. A short-lived detrital input event is observed at 58.5 m depth (Figs. 6 and 10), marked by a localized decrease in TOC and an increase in clay content (Fig. 6). The exact cause of this event is uncertain, but potential triggers include a period of storm surges, nearby volcanism, or seismic activity. A unique feature of this cycle is the presence of organic matter/solid bitumen within the fossil chambers (Fig. 15). This suggests pre-expulsion bitumen migration at relatively low temperature, commonly associated with Type-IIS kerogens13. In these rocks, the sulfur-rich organic matter behaves as a semi-mobile phase that can migrate over short distances inside source rocks prior to the incipient oil generation stage76.

Cycle 2 spans 1.31 million years, with a thickness of 11.5 m and a sedimentation rate of 9.2 m/Ma. This cycle corresponds to silica-rich mudstone to wackestone facies. A significant compositional shift is observed in this cycle marked by an increase in Si-content and a corresponding decrease in Ca-content (Figs. 6 and 10). This shift reflects a change in the dominant biota, where silica-secreting organisms, such as diatoms, radiolarians, and sponges produced amorphous silica (Opal-A), which later transformed into Opal-CT during diagenesis77,78. The shift in biota is interpreted to represent an increased nutrient supply favouring the proliferation of siliceous organisms over carbonate-secreting ones54,79. Such biogenic siliceous oozes typically accumulate in nutrient-rich upwelling regions, similar to those found in the equatorial and polar belts, as well as coastal upwelling zones like the North Pacific and Antarctic80. All these regions feature high biogenic productivity and reducing bottom-water conditions. Corresponding elevated concentrations of productivity-related trace metals (Ni, Cu, and Zn), and paleoredox trace metals (i.e. Mo, V and U) are observed (Fig. 10) in Cycle 2. We interpret these changes in upwelling and nutrient supply to be driven by an increase in the vigor of long-shore currents due to a sustained 1 million year-long change in climate and wind patterns.

The co-occurrence of Opal CT and organic matter inside the fossil chambers is another unique feature of this cycle (Fig. 16). This indicates a pre-oil bitumen migration inside the fossil chamber after the dissolution and re-crystallization of opal-A to opal-CT, leading to the simultaneous entrapment of both organic and inorganic components within the fossil chambers.

Cycle 3, spanning 0.91 Ma, has a thickness of 14.5 m and a sedimentation rate of 14.8 m/Ma. This cycle marks a return to carbonate-dominated deposition, with a decline in siliceous biota and a corresponding re-emergence of calcium-secreting organisms. Lower concentrations of productivity and redox proxies (Ni, Cu, Zn, Mo, V, U) corroborate a reduced paleo-productivity and/or organic matter preservation for this cycle (Fig. 10). In this cycle the increase in Al and Ti content indicates a higher detrital input, mostly in the form of clays. This, in combination with a higher density of carbonate grains – mainly benthic foraminifera – suggests an increase in currents and oxygenation and relatively lower TOC preservation compared to the other JSR cycles (Figs. 6 and 10). Unlike the previous cycles, the organic matter in this cycle is mostly dispersed within the matrix, with minimal occurrence inside fossil chambers (Figs. 14 and 17). Instead, these chambers are predominantly filled with calcite cement, suggesting that early carbonate cementation occurred before the organic matter reached pre-bitumen migration temperatures. This could also be attributed to the relatively lower organic sulfur content in this cycle, which may have reduced an early mobility of organic matter within the rock matrix.

Regional correlation and geochemical cyclicity

Overall, the JSR exhibits geochemical characteristics like other late Cretaceous source rocks in the eastern Mediterranean region, with its composition primarily dominated by carbonate minerals, particularly calcite21,22,25,29,81. A key new observation in the JSR is the presence of three distinct geochemical cycles, each characterized by unique variations in organic and inorganic geochemical composition (Figs. 4, 6 and 10). The detailed characterization of the JSR geochemical cycles presents a unique opportunity to develop a high-resolution regional stratigraphic model for Eastern Mediterranean source rocks. Encouraging support for such an effort is provided by the recognition of TOC cycles, which have been documented by Meilijson et al.24 in Maastrichtian organic-rich strata of the Shefela Basin. A regional correlation would significantly enhance the understanding of the late Cretaceous Eastern Mediterranean shelf system, paleo-oceanographic conditions at the southern Tethys margin, source rock distribution in MENA, and hydrocarbon potential across the region.

Impact of compositional heterogeneity in unconventional reservoirs

Understanding the shifts in organic and inorganic geochemical composition is crucial for evaluating the petroleum potential of source rocks, as it directly influences their mechanical, thermal, and geochemical properties17. The cyclic alternation between carbonate- and silica-rich intervals, as observed in the JSR, has significant implications both for conventional and unconventional resource assessment. These variations can indicate preferential reservoir zones (“sweet spots”), guiding well placement and completion strategies. For instance, silica-rich intervals, particularly those cemented by Opal-CT, are generally more brittle than carbonate-cemented equivalents, enhancing the intervals disposition for hydraulic fracturing82. In addition to its mechanical effects, biogenic silica also alters the thermal properties of the source rock17. Compared to carbonate-rich lithologies, silica-rich intervals have higher thermal conductivity, leading to earlier hydrocarbon generation and potential of expulsion via maturation-caused natural fracture systems17. Such information is critical for identifying migration pathways and refining basin modeling predictions. Moreover, understanding the spatial and stratigraphic distribution of such cycles enables improved characterization of unconventional reservoirs, optimizing stimulation techniques and maximizing hydrocarbon recovery from organic-rich source rocks.

Conclusion

This study provides a detailed organic and inorganic geochemical and mineralogical characterization of the Maastrichtian carbonate source rocks in central Jordan, revealing significant compositional heterogeneities linked to depositional cyclicity. The JSR shares key geochemical and paleoenvironmental characteristics with other organic-rich deposits across the Eastern Mediterranean, with its deposition influenced by a major nutrient upwelling system along the southern Tethys margin during the Maastrichtian.

The identification of three distinct geochemical cycles within the JSR highlights variations in organic matter distribution, mineralogical composition, and depositional conditions. Geochemical proxies suggest that shifts in nutrient upwelling intensity and redox conditions played a critical role in organic matter accumulation and preservation. Notably, the transition from carbonate-dominated to silica-dominated biota reflects climatic and oceanographic fluctuations, potentially driven by variations in wind patterns and upwelling dynamics, which altered nutrient availability.

The presence of solid bitumen and Opal-CT within intra-particle fossil chambers provides direct evidence of early silica diagenesis and pre-oil bitumen migration under low thermal maturity conditions. This observation highlights the role of organic-sulfur-rich kerogen in early hydrocarbon mobilization and storage, with implications for unconventional hydrocarbon potential in similar systems. Additionally, variations in detrital influx, as indicated by Al and Ti enrichments in Cycle 3, suggest periodic shifts in terrestrial input that influenced organic matter dilution and preservation.

The recognition of these high-order geochemical cycles in the JSR and their correlation with time-equivalent organic-rich intervals across the southern Tethys margin provide a refined stratigraphic framework for regional palaeoceanographic reconstruction. Integrating these geochemical insights into petroleum system models improves the predictive accuracy of exploration strategies for both conventional and unconventional hydrocarbon resources. In unconventional reservoirs, understanding compositional heterogeneities is critical for optimizing drilling strategies, refining completion techniques, and enhancing hydrocarbon recovery efficiency.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files).

References

McCarthy, K. et al. Basic petroleum geochemistry for source rock evaluation. Oilfield Rev. 23, 32–43 (2011).

Talbot, M. R. & Livingstone, D. A. Hydrogen index and carbon isotopes of lacustrine organic matter as lake level indicators. Palaeogeogr., Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 70, 121–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/0031-0182(89)90084-9 (1989).

Meyers, P. A. & Ishiwatari, R. in In Organic Geochemistry: Principles and Applications. 185–209 (eds Engel, M. H., Stephen, A. & Macko) (Springer US, 1993).

Babakhani, P. et al. Preservation of organic carbon in marine sediments sustained by sorption and transformation processes. Nat. Geosci. 18, 78–83. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-024-01606-y (2025).

Tribovillard, N., Algeo, T. J., Lyons, T. & Riboulleau, A. Trace metals as paleoredox and paleoproductivity proxies: An update. Chem. Geol. 232, 12–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2006.02.012 (2006).

Bou Daher, S., Nader, F. H., Müller, C. & Littke, R. Geochemical and petrographic characterization of Campanian-Lower maastrichtian calcareous petroleum source rocks of Hasbayya, South Lebanon. Mar. Pet. Geol. 64, 304–323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2015.03.009 (2015).

Sajid, Z. et al. Impact of paleosalinity, paleoredox, paleoproductivity/preservation on the organic matter enrichment in black shales from triassic turbidites of semanggol basin, Peninsular Malaysia. Minerals 10, 1–34. https://doi.org/10.3390/min10100915 (2020).

Leushina, E. et al. Upper jurassic–lower cretaceous source rocks in the North of Western Siberia: comprehensive geochemical characterization and reconstruction of paleo-sedimentation conditions. Geosci. (Switzerland). 11 https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences11080320 (2021).

Fathy, D., Baniasad, A., Littke, R. & Sami, M. Tracing the geochemical imprints of maastrichtian black shales in Southern Tethys, Egypt: assessing hydrocarbon source potential and environmental signatures. Int. J. Coal Geol. 283, 104457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coal.2024.104457 (2024).

Jenkyns, H. C. Cretaceous anoxic events: from continents to oceans. J. Geol. Soc. 137, 171–188. https://doi.org/10.1144/gsjgs.137.2.0171 (1980).

Muhaisen Alnawafleh, H. Jordanian oil shales: variability, processing technologies, and utilization options. J. Energy Nat. Resour. 4, 52–52. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.jenr.20150404.11 (2015).

Hakimi, M. H., Abdullah, W. H., Alqudah, M., Makeen, Y. M. & Mustapha, K. A. Organic geochemical and petrographic characteristics of the oil shales in the Lajjun area, central Jordan: origin of organic matter input and preservation conditions. Fuel 181, 34–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2016.04.070 (2016).

Grohmann, S. et al. The deposition of type II-S Jordan oil shale in the context of late cretaceous source rock formation in the Eastern mediterranean realm. Insights from organic and inorganic geochemistry and petrography. Mar. Pet. Geol. 148, 106058–106058. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2022.106058 (2023).

Sakhrieh, A. & Hamdan, M. in Global Conference on Power Control and Optimization, Dubai, UAE, 1–3 June 2011 A.

Fathy, D. et al. Geochemical characterization of upper cretaceous organic-rich deposits: Insights from the Azraq basin in Jordan. J. Asian Earth Sci. 276, 106365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jseaes.2024.106365 (2024).

Alnawafleh, H., Tarawneh, K., Siavalas, G., Christanis, K. & Iordanidis, A. Geochemistry and organic petrography of Jordanian Sultani oil shale. Open. J. Geol. 06, 1209–1220. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojg.2016.610089 (2016).

Usman, M., Grohmann, S., Abu-Mahfouz, I. S., Vahrenkamp, V. & Littke, R. Effects of geochemical compositional heterogeneities on hydrocarbon expulsion and thermal maturation: an analog study of maastrichtian source rocks from Jordan. Int. J. Coal Geol. 294, 104587–104587. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coal.2024.104587 (2024).

Ibrahim, K. M., Aljurf, S., Rahman, H. A. & Gülamber, C. Exploration and evaluation of oil shale resources from attarat area, central Jordan. IMCET 2019 - Proceedings of the 26th International Mining Congress and Exhibition of Turkey, 1116–1128 (2019).

El-rub, Z. A., Kujawa, J. & Albarahmieh, E. & Al-rifai, N (High Throughput Screening and Characterization, 2019).

Abed, A. M., Arouri, K. R. & Boreham, C. J. Source rock potential of the phosphorite-bituminous chalk-marl sequence in Jordan. Mar. Pet. Geol. 22, 413–425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2004.12.004 (2005).

Bou Daher, S., Nader, F. H., Strauss, H. & Littke, R. Depositional environment and source-rock characterisation of organic-matter rich upper santonian - upper Campanian carbonates, Northern Lebanon. J. Pet. Geol. 37, 5–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpg.12566 (2014).

Yang, R., Wang, Y. & Cao, J. Cretaceous source rocks and associated oil and gas resources in the world and China: A review. Pet. Sci. 11, 331–345. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12182-014-0348-z (2014).

Rosenberg, Y. O., Reznik, I. J., Vinegar, H. J., Feinstein, S. & Bartov, Y. Comparing natural and artificial thermal maturation of a type II-S source rock, late cretaceous, Israel. Mar. Pet. Geol. 124, 104773–104773. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2020.104773 (2021).

Meilijson, A. et al. Chronostratigraphy of the upper cretaceous high productivity sequence of the Southern Tethys, Israel. Cretac. Res. 50, 187–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cretres.2014.04.006 (2014).

Grohmann, S. et al. Source rock characterization of mesozoic to cenozoic organic matter rich marls and shales of the Eratosthenes seamount, Eastern mediterranean sea. Oil Gas Sci. Technol. 73 https://doi.org/10.2516/ogst/2018036 (2018).

Vail, P. R., Audemard, F., Bowman, S. A., Eisner, P. N. & Perez-Cruz, C. in Cycles Events Stratigraphy 617–659 (1991).

Ali Hussein, M., Alqudah, M., Blessenohl, M., Podlaha, O. G. & Mutterlose, J. Depositional environment of late cretaceous to eocene organic-rich marls from Jordan. GeoArabia 20, 191–210 (2015).

Alqudah, M., Ali Hussein, M., van den Boorn, S., Podlaha, O. G. & Mutterlose, J. Biostratigraphy and depositional setting of Maastrichtian - Eocene oil shales from Jordan. Mar. Pet. Geol. 60, 87–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2014.07.025 (2015).

Fathy, D. et al. Maastrichtian anoxia and its influence on organic matter and trace metal patterns in the Southern Tethys realm of Egypt during greenhouse variability. ACS Omega. 8, 19603–19612. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.3c01096 (2023).

Powell, J. H. & Moh’d, B. K. Evolution of cretaceous to eocene alluvial and carbonate platform sequences in central and South Jordan. GeoArabia 16, 29–82 (2011).

Powell, J. Stratigraphy and Sedimentation of the Phanerozoic Rocks in Central and South Jordan; Part B, Kurnub, Ajlun and Belqa Groups. Natural Resources Authority, Amman, Geological Mapping Division Bulletin, 11A (1989).

Beik, I., Gómez, V. G., Podlaha, O. G. & Mutterlose, J. Microfacies and depositional environment of late cretaceous to early paleocene oil shales from Jordan. Arab. J. Geosci. 10 https://doi.org/10.1007/s12517-017-3118-6 (2017).

Abed, A. M. & Amireh, B. S. Petrography and geochemistry of some Jordanian oil shales from North Jordan. J. Pet. Geol. 5, 261–274. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-5457.1983.tb00571.x (1983).

Hakimi, M. H., Abdullah, W. H., Alqudah, M., Makeen, Y. M. & Mustapha, K. A. Reducing marine and warm climate conditions during the late cretaceous, and their influence on organic matter enrichment in the oil shale deposits of North Jordan. Int. J. Coal Geol. 165, 173–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coal.2016.08.015 (2016).

Ibrahim, K. M. & Jaber, J. O. Geochemistry and environmental impacts of retorted oil shale from Jordan. Environ. Geol. 52, 979–984. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00254-006-0540-6 (2007).

Ziegler, M. A. Late permian to holocene paleofacies evolution of the Arabian plate and its hydrocarbon occurrences. GeoArabia 6, 445–504 (2001).

Luthi, S. M. Geological Well Logs (Springer, 2001).

Behar, F., Beaumont, V., De, B. & Penteado, H. L. Rock-Eval 6 technology: Performances and developments. Oil Gas Sci. Technol. 56, 111–134. https://doi.org/10.2516/ogst:2001013 (2001).

Carvajal-Ortiz, H., Gentzis, T. & Ostadhassan, M. Sulfur differentiation in Organic-Rich shales and carbonates via Open-System programmed pyrolysis and oxidation: insights into fluid souring and H2S production in the Bakken shale, united States. Energy Fuels. 35, 12030–12044. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.energyfuels.1c01562 (2021).

Messaoud, J. H. et al. Chronostratigraphy of the mixed upper cretaceous deposits at the Northern margin of the Arabian plate (Jordan). Newsl. Stratigr. https://doi.org/10.1127/nos/2025/0858 (2025).

Dunham, R. J. Classification of Carbonate Rocks According to Depositional Textures. Classification of Carbonate Rocks–A Symposium, 108–121 (1962).

Lazar, O. R., Bohacs, K. M., Macquaker, J. H. S., Schieber, J. & Demko, T. M. Capturing key attributes of fine-grained sedimentary rocks in outcrops, cores, and thin sections: Nomenclature and description guidelines. J. Sediment. Res. 85, 230–246. https://doi.org/10.2110/jsr.2015.11 (2015).

Pufahl, P. K., Grimm, K. A., Abed, A. M. & Sadaqah, R. M. Y. Upper Cretaceous (Campanian) phosphorites in Jordan: Implications for the formation of a south Tethyan phosphorite giant. Vol. 161 (2003).

Peters, K. E., Walters, C. C. & Moldowan, J. M. The Biomarker GuideVol. 58 (Cambridge University Press, 2004).

Sokol, E. V. et al. Calcareous sediments of the Muwaqqar chalk marl formation, Jordan: Mineralogical and geochemical evidences for Zn and cd enrichment. Gondwana Res. 46, 204–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gr.2017.03.008 (2017).

Filippelli, G. M. Phosphate rock formation and marine phosphorus geochemistry: the deep time perspective. Chemosphere 84, 759–766. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2011.02.019 (2011).

Little, S. H., Vance, D., Lyons, T. W. & McManus, J. Controls on trace metal authigenic enrichment in reducing sediments: Insights from modern oxygen-deficient settings. Am. J. Sci. 315, 77–119. https://doi.org/10.2475/02.2015.01 (2015).

Scholz, F., Siebert, C., Dale, A. W. & Frank, M. Intense molybdenum accumulation in sediments underneath a nitrogenous water column and implications for the reconstruction of paleo-redox conditions based on molybdenum isotopes. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 213, 400–417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2017.06.048 (2017).

Algeo, T. J. & Liu, J. A re-assessment of elemental proxies for paleoredox analysis. Chem. Geol. 540, 119549–119549. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2020.119549 (2020).

Tribovillard, N., Algeo, T. J., Baudin, F. & Riboulleau, A. Analysis of marine environmental conditions based on molybdenum-uranium covariation-Applications to mesozoic paleoceanography. Chem. Geol. 324–325, 46–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2011.09.009 (2012).

Fleurance, S., Cuney, M., Malartre, F. & Reyx, J. Origin of the extreme polymetallic enrichment (Cd, Cr, Mo, Ni, U, V, Zn) of the late Cretaceous-Early tertiary Belqa group, central Jordan. Palaeogeogr., Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 369, 201–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2012.10.020 (2013).

Brumsack, H. J. The trace metal content of recent organic carbon-rich sediments: implications for cretaceous black shale formation. Palaeogeogr., Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 232, 344–361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2005.05.011 (2006).

Brumsack, H. J. Geochemistry of recent TOC-rich sediments from the Gulf of California and the black sea. Geol. Rundsch. 78, 851–882. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01829327 (1989).

Calvert, S. E. & Pedersen, T. F. Geochemistry of recent oxic and anoxic marine sediments: Implications for the geological record. Mar. Geol. 113, 67–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/0025-3227(93)90150-T (1993).

Morford, J. L. & Emerson, S. The geochemistry of redox sensitive trace metals in sediments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 63, 1735–1750. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-7037(99)00126-X (1999).

Van Buchem, F. S. P., Huc, A. Y., Pradier, B. & Stefani, M. M. in Deposition Organic-Carbon-Rich Sediments: Models 191–223 (2005).

Sageman, B. B. et al. A Tale of shales: The relative roles of production, decomposition, and Dilution in the accumulation of organic-rich strata, Middle-Upper devonian, Appalachian basin. Chem. Geol. 195, 229–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0009-2541(02)00397-2 (2003).

Scholz, F. Identifying oxygen minimum zone-type biogeochemical cycling in Earth history using inorganic geochemical proxies. Earth Sci. Rev. 184, 29–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2018.08.002 (2018).

Sajid, Z., Ismail, M. S., Tsegab, H., Hanif, T. & Ahmed, N. Paleoproductivity / Preservation on the organic matter enrichment in black shales from triassic turbidites. Minerals 10 (2020).

Boning, P. et al. Geochemistry of Peruvian near-surface sediments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 68, 4429–4451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2004.04.027 (2004).

Mort, H. P. et al. Phosphorus and the roles of productivity and nutrient recycling during oceanic anoxic event 2. Geology 35, 483–486. https://doi.org/10.1130/G23475A.1 (2007).

Algeo, T. J. & Ingall, E. Sedimentary Corg:P ratios, paleocean ventilation, and phanerozoic atmospheric pO2. Palaeogeogr., Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 256, 130–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2007.02.029 (2007).

Emerson, S. R. & Huested, S. S. Ocean anoxia and the concentrations of molybdenum and vanadium in seawater. Mar. Chem. 34, 177–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-4203(91)90002-E (1991).

Scott, C. & Lyons, T. W. Contrasting molybdenum cycling and isotopic properties in euxinic versus non-euxinic sediments and sedimentary rocks: refining the paleoproxies. Chem. Geol. 324–325, 19–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2012.05.012 (2012).

Bennett, W. W. & Canfield, D. E. Redox-sensitive trace metals as paleoredox proxies: A review and analysis of data from modern sediments. Earth Sci. Rev. 204, 103175–103175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2020.103175 (2020).

Algeo, T. J. & Tribovillard, N. Environmental analysis of paleoceanographic systems based on molybdenum-uranium covariation. Chem. Geol. 268, 211–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2009.09.001 (2009).

Cai, C. et al. Enigmatic super-heavy pyrite formation: novel mechanistic insights from the aftermath of the sturtian snowball Earth. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 334, 65–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2022.07.026 (2022).

Huggett, J., Hooker, J. N. & Cartwright, J. Very early diagenesis in a calcareous, organic-rich mudrock from Jordan. Arab. J. Geosci. 10 https://doi.org/10.1007/s12517-017-3038-5 (2017).

Sáez, R., Moreno, C., González, F. & Almodóvar, G. R. Black shales and massive sulfide deposits: Causal or casual relationships? Insights from Rammelsberg, tharsis, and Draa Sfar. Miner. Deposita. 46, 585–614. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00126-010-0311-x (2011).

Cai, C. et al. N biogeochemical processes in the redox-stratified early cambrian Yangtze ocean. J. Geol. Soc. 172, 390–406. https://doi.org/10.1144/jgs2014-054 (2015). Marine C.

März, C. et al. Repeated enrichment of trace metals and organic carbon on an eocene high-energy shelf caused by anoxia and reworking. Geology 44, 1011–1014. https://doi.org/10.1130/G38412.1 (2016).

Ofili, S. et al. Geochemical Reconstruction of the Provenance, Tectonic Setting and Paleoweathering of Lower Paleozoic Black Shales from Northern Europe. Minerals 12, (2022). https://doi.org/10.3390/min12050602

März, C., Vogt, C., Schnetger, B. & Brumsack, H. J. Geochemistry and mineralogy of Eocene-Oligocene sediments of IODP hole 302-M0002A. PANGEA https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.786428 (2011).

Brumsack, H. J. Inorganic geochemistry of the German ‘posidonia shale’: palaeoenvironmental consequences. Geol. Soc. Lond. Special Publications. 58, 353–362. https://doi.org/10.1144/GSL.SP.1991.058.01.22 (1991).

Farouk, S., Ahmad, F., Mousa, D. & Simmons, M. Sequence stratigraphic context and organic geochemistry of palaeogene oil shales, Jordan. Mar. Pet. Geol. 77, 1297–1308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2016.08.022 (2016).

Curiale, J. A. Origin of solid bitumens, with emphasis on biological marker results. Org. Geochem. 10, 559–580. https://doi.org/10.1016/0146-6380(86)90054-9 (1986).

Longfei, L. et al. Petroleum Geology & Experiment Early diagenesis characteristics of biogenic opal and its influence on porosity and pore network evolution of siliceous shale. (2020).

Schieber, J., Krinsley, D. & Riciputi, L. Diagenetic origin quartz silt in mudstones and implications for silica cycling. Nature 406, 981–985. https://doi.org/10.1038/35023143 (2000).

Calvert, S. E. & Pedersen, T. F. in Developments in Marine Geology Vol. 1 (eds Claude Hillaire–Marcel & Anne De Vernal) 567–644, Elsevier, (2007).

Rothwell, R. G. In Reference Module in Earth Systems and Environmental Sciences (Elsevier, 2016).

Marlow, B. L., Kendall, C. C. G. & Yose, L. A. Petroleum Syst. Tethyan Regionhttps://doi.org/10.1306/13431883M1063630 (2014).

Iakusheva, R., Abu-Mahfouz, I., Usman, M., Finkbeiner, T. & Vahrenkamp, V. in 85th EAGE Annual Conference & Exhibition (including the Workshop Programme). 1–5 (European Association of Geoscientists & Engineers).

Acknowledgements

The authors express their sincere gratitude to the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources (MEMR) and Karak International Oil (KIO), Jordan, for providing the core samples and granting the necessary approvals for this research. We also extend our appreciation to the members of KAUST-CARESS team for their valuable support in data analysis and manuscript revision. Additionally, we would like to thank Jihede Haj Messaoud (KAUST) for his help with the nannofossil and age-dating results. Finally, we thank the editor and anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback and insightful comments, which have greatly enhanced the quality of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Muhammad Usman: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Maria Ardila-Sanchez: Investigation, Methodology, Data curation, Validation. Erdem Idiz: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Validation, Data curation, Visualization, Conceptualization. Israa S. Abu-Mahfouz: Writing – review & editing, Resources. Frans van Buchem: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Validation, Data curation, Methodology. Volker Vahrenkamp: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Resources, Conceptualization.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Usman, M., Ardila-Sanchez, M., Idiz, E. et al. Organic and inorganic geochemical cyclicity of a Maastrichtian oceanic open-shelf carbonate source rock. Sci Rep 15, 15993 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99832-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99832-w