Abstract

Thermal neutron detection in neutron scattering science is a challenging endeavour due to a limited number of technologies which are sensitive to these weakly interacting particles. While many improvements to conventional detectors are underway at various facilities, there is a great opportunity to make a leap in performance by combining the spatial resolution benefits of imaging and the temporal resolution and background discrimination of event-driven radiation detectors. This idea has been realized by using a neutron sensitive scintillator read out by a single-photon sensitive camera based on a Timepix3 ASIC. We demonstrate how such data-driven imaging sensors can enable unprecedented performance in neutron reflectometry using the ASTERIX instrument at the Los Alamos Neutron Scattering Center. Several samples were measured with both the new and a conventional \(^3\)He detector systems. The results from this work demonstrate that these imaging based systems can satisfy performance parameters for the future QIKR reflectometer to be built at the Second Target Station at Oak Ridge National Laboratory. Further improvements to the detector are already underway which will allow streamlined and expedited experiments. We demonstrate at least a two order of magnitude increase in detection rate at an acceptable dead time and introduce a new way of tuning the detector efficiency using light collecting optics to accommodate highly intense direct beams which cannot be measured with any current detectors without severe attenuation. This will allow measurements of complete reflectometry profiles and using a single sample measurement combined with fewer direct beam calibration measurements on QIKR and potentially other reflectometers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Neutron reflectometry is a non-destructive technique that enables studies of thin films and structures at interfaces of materials1,2,3. It probes the surface properties of a material. Examples of samples include inorganic materials sputtered on a substrate and biological membranes supported on a surface of a solvent. Neutron reflectometry is widely used at both reactor and spallation neutron sources. At these sources, primary neutrons are produced in nuclear reactions with energies of several MeV and higher. Moderators are used to slow down neutrons to room temperature, or even cryogenic thermal energies, via inelastic scattering on light nuclei. Resulting beams can be collimated and guided in a way that is tailored for a given type of experiment. In reflectometry, the beam is focused and collimated into a spot size of typically 10-20 mm wide and less than 1 mm tall. As it impinges on a surface of a sample at a small angle, the projected footprint extends along the beam direction to optimally cover the surface of the sample.

The reflectivity of a sample is a function of the momentum transfer, Q, from the sample to the reflected neutron. \(Q={4\pi sin(\theta )}/{\lambda }\), where \(\theta\) is the incident angle and \(\lambda\) is the neutron wavelength. Momentum transfer range covers a large dynamic ranges of intensities from total reflection below a critical momentum transfer, dropping many orders of magnitude for greater values of Q. Either a scan in neutron wavelength or in incident angle can be used to map the momentum transfer range. This means that the technique lends itself particularly well to pulsed neutron sources where the time of arrival, or Time-of-Flight (ToF) of detected neutrons provides information on their energy, or, equivalently, wavelength. With a wide enough incident wavelength band, a measurement at a single incident angle can provide a full range of momentum transfer to cover the entire reflectivity profile.

Many different detectors have been used in reflectometry. As in most neutron scattering, \(^3\)He detectors are the most common class. Single \(^3\)He tubes with or without position sensitivity have been used in many cases, including at ASTERIX at Los Alamos Neutron Scattering Center, LANSCE. Multi-wire proportional chambers, MWPCs, such as the detectors from Brookhaven National Laboratory4 used at Liquids Reflectometer and Magnetism Reflectometer at the Spallation Neutron Source, SNS. Other versions of MWPCs are installed at other locations; for instance SuperADAM reflectometer at Institute Laue Langevin, ILL, uses a Denex detector5. The ILL Multi-Tube \(^3\)He technology6 is used at other ILL reflectometers, Figaro and D17, as well as at the PLATYPUS instrument at the OPAL Research Reactor. The ISIS Neutron and Muon Source uses scintillator detectors readout by wavelength-shifting fibers7 on several reflectometers. Finally, the European Spallation Source aims to use a \(^{10}\)B layer Multi-Blade detector8 at its ESTIA an FREIA reflectometers which are under construction. Further technologies have been tested9. This variety of detector technologies highlights the efforts that have been made to improve reflectometer performance. In this paper, we focus on applying an event-based imaging detector to reflectometry which promises a significant leap in counting rate capability—one of the most challenging aspects in neutron reflectometry.

Detector requirements for QIKR

The QIKR instrument under design for the Second Target Station, STS, of the Spallation Neutron Source, SNS, will be just such an instrument10. A cold moderator with a 15 Hz repetition rate will allow measuring neutrons from 2.5 to 14.5 Å at the 20 m source-to-detector distance. Selecting only every other source pulse using a chopper, increases this range to up to 25 Å. Provided a time-resolved detector, reflectivity can be reconstructed for each neutron wavelength in this range from each source pulse. Each following pulse adds further statistics to the measurement. A beam with a high neutron flux will be delivered by the source and instrument neutron guide ensuring that sufficient statistics can be collected in seconds to minutes, allowing observation of time-dependent processes in-situ10. This is in contrast to many existing reflectometers, where multiple angular settings need to be measured in order to obtain one complete reflectivity profile covering the full momentum transfer range of interest. The rate capability of a detector, as well as its time resolution, are thus the key parameters. Additionally, spatial resolution helps us to isolate the specular reflection from off-specular as well as from background by accurately defining the spatial regions of interest corresponding to signal and to background. It can even extend the reflectivity measurement to make the instrument sensitive to variations over the sample area11.

Reflectivity curves, such as those that will be presented in the “Results” section of this paper, carry information on the surface structure of the sample. In order to correctly reconstruct reflectivity from the measured reflected neutron beam, the direct beam, which is specific to detector and beam optics settings, has to be accurately measured in addition to the reflected beam. Due to the fact that neutron absorption is a non-constant function of its wavelength, the detection efficiency will likewise vary. In order to accurately measure the wavelength dependence of the incident beam, direct beam measurements are taken, in practice, for each setting of the instrument in each user experiment. These direct beams present the greatest challenge for the detector in terms of rate capability, as the direct beam at its peak is usually several orders of magnitude more intense than the reflected beam at any wavelength. Note that since the detection efficiency is also a function of wavelength, it is necessary to measure the direct beam with the same detector which also measures the reflected beam. Reflected beams, while typically much less challenging, do push the need for fast detectors with low dead time.

Total reflection from a sample occurs for small momentum transfers. For a fixed angle, this is at long wavelengths, where the beam flux is lowest. On the other hand, the peak of the neutron flux occurs close to the shortest wavelength end of the spectrum, and is only weakly reflected by the sample. These two competing effects result only in approximately an order of magnitude variation in rate for a given measurement of reflection from a sample. This is illustrated in Fig. 1. For a direct beam, however, the full intensity at the peak needs to be measured. The strategy for QIKR is to measure all reflected beam with no attenuation. For this, a fast detector with a linear response is needed. The direct beam, which has been modeled to reach 300 MHz in the most intense setting on QIKR, must be measured in another way. Typically, this involves attenuation, which too is unfortunately wavelength dependent. In the “Results” section, we will show that with the new detection method, the detector efficiency can be adjusted instead of reducing the beam flux. Regardless, a detector with rate capabilities exceeding minimum requirements of reflected beams would enhance the performance of the instrument.

Monte Carlo simulation of direct beam and reflected beam from a heavy water sample at QIKR. Reflectivity of heavy water is shown as the dashed green line. Note the total reflection above 12.5 Å. Here, the simulated beam was relatively narrow in order to not over-illuminate the sample at the incident angle of 1 degree, resulting in about a factor 20 lower than the maximum flux on QIKR.

The rate in a full direct beam expected at QIKR cannot be measured with any current detector. This is also the case at other existing reflectometers, such as Liquids Reflectometer at the SNS, where the direct beams have to be measured in a sequence of attenuated measurements while iteratively correcting for the wavelength-dependent attenuation. This consumes considerable time that would otherwise be available for additional samples or experiments. A highly desirable goal is therefore to measure with no need for beam attenuators. We will demonstrate that the detector used in this study has a capability of adjusting detection efficiency in a nearly energy-independent fashion. This can help alleviate the need for attenuated measurements.

LumaCam photon-counting neutron detector

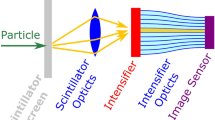

In this work, we have for the first time used a photon-counting imaging detector to measure neutron reflectivity. While this detector technology originates from neutron imaging applications, it has now been enhanced to provide true event-based data. It also benefits from the state-of-the-art background rejection algorithms, which are only possible in an event-driven detector. The detector has been described in a previous publication12. Several tests have been performed demonstrating the advantages of event-based imaging, for instance, in resonance imaging. It has also been demonstrated in neutron diffraction and shown highly promising performance13. Additionally, a detector based on the same principle has been demonstrated in Spin Echo Modulated Small Angle Scattering, SEMSANS14. The detector used in this work was produced by LoskoVision and is referred to as LumaCam, see Fig. 2.

The main components of the detector are listed in Table 1. Several detection settings can be adjusted. The optical lens is focused using a translation stage and the focus ring. A second lens is located at the output of the image intensifier and relays the intensified light to the Timepix3 ASIC. The image intensifier uses dual Micro-Channel Plates, MCPs, in a chevron configuration to amplify the electron signal from the photo cathode at the input and to stimulate emission from a phosphor at the output. The MCP gain can be adjusted to optimally balance efficiency and background rejection. In each neutron event, multiple sensor pixels are activated for each event. As the first stage of the reconstruction algorithm, clusters belonging to individual photons are determined. The position of each photon is calculated using a center-of-mass algorithm. As a second step, photons that were likely emitted as a result of the same neutron capture are identified. At this stage, the characteristic signatures of neutron conversion events can be identified and discriminated from those corresponding to other types of events. An example of this is the discrimination between neutrons and \(\gamma\)-rays relying on well-known pulse-shape discrimination, PSD, methods7,15. The achievable position resolution exceeds the physical sensor pixellation by as much as a factor of 10. The details of the data reconstruction have been published previously12 and will be built upon in forthcoming publications. Here, we restrict the scope to the reflectometry results.

It should be noted that more light detected in the sensor does not necessarily equate to a better performance. Excessively raising the MCP gain degrades the response of the intensifier and makes it less linear with incoming photon rate. Additionally, more light leads to more Timepix3 pixels triggered for every neutron, and since the maximum throughput of the readout is currently limited to 80 million hits per second16, minimizing the number of photons to the smallest number that still enables pulse shape discrimination is desirable. The highest neutron rate can be achieved by reducing the average number of photons detected to just 1 per neutron. Operating at such a low gain effectively sets a very high threshold which can reject majority of background. While this comes at a cost to detection efficiency, such a trade-off may be reasonable when the full flux is beyond the detector capability in either setting. A low efficiency setting with high throughput may allow more counts to be collected than in a high-efficiency low-throughput setting. Note, however, that pulse shape discrimination methods cannot be applied when single photons are interpreted as neutrons. There is also an impact on detector resolution as no centroiding can be performed if only one photon is available. Therefore the use of such settings must be carefully considered depending on the measurement situation.

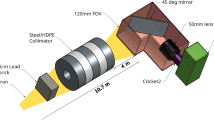

Using a short telephoto lens with an 85 mm focal length, the field of view was set to 55 × 55 \(\hbox {mm}^2\). This is sufficient for measuring specular reflectivity from modestly-sized samples; however, a larger field of view would be necessary to capture off-specular phenomena. A field of view of 110 × 110 \(\hbox {mm}^2\) can be achieved by switching to a 50 mm lens and translating the camera about 30 mm back. Field of view can be tailored to specific experiments by adjusting the optical arrangement. A 120 × 120 \(\hbox {mm}^2\) \(\hbox {ZnS:}^6\)LiF scintillator with thickness of 200 \(\upmu\)m was used. Since the shortest wavelength at ASTERIX was 4 Å, this thickness offered sufficient efficiency, while limiting the depth of interaction of neutron and thus reducing the spread of light collection efficiency, due to the spread in light emission and the opaque nature of the scintillator.

The data is streamed from the Timepix3 ASIC via an FPGA to a 10Gb/s fiberoptic network and stored on a computer solid state drive. The analysis software runs in parallel to perform clustering and determine neutron events from the pixel data produced by the ASIC. This can be seen as semi real time processing and has a benefit of buffering the data helping to handle temporary rate peaks—both rapid, such as the intensity maxima in the neutron ToF frame, as well as slow, such as runs at different intensities. Raw data can be retained for further online analysis and algorithm development, which is still ongoing. There are developments that will enhance clustering as well as potentially move a portion of the computation into an FPGA in order to accommodate increases of rate capability which will be discussed later in this paper.

Methods

The reflectometry performance of the new detector was evaluated at the ASTERIX reflectometer at LUJAN Center at Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL). The beamline is equipped with an ORDELA 1202N 1-D position-sensitive \(^3\)He detector17,18. The detector is filled with a mixture of \(^3\)He and \(\hbox {CF}_4\) with a partial pressure of 3.6 mbar of \(^3\)He. For the measurements with the LumaCam, the \(^3\)He detector was uninstalled and the LumaCam was set up in its position, see Fig. 3. The final sample-to-detector distance was measured as a difference to the known \(^3\)He detector distance. The detector arm moved the LumaCam in the same arch, centered on the sample position, where the \(^3\)He detector normally moves, making the measurements directly comparable.

Samples of a 140 nm nickel film and 46 nm iridium film on quartz substrates as well as a sample of bare quartz were placed on the sample table and remained in the same positions throughout the experiment. The table could be positioned to place any of the samples in beam or to move them out of the beam entirely. The position and the intensity of the reflection from each sample measured by the LumaCam were used to align each sample with the beam as well as to determine an angle correction for each sample. The openings of the beam shaping slits were adjusted to illuminate each sample as fully as possible without over-illumination. This resulted in approximately 2.5 times larger beam in case of the Ni sample, since it had a larger surface area than the other two samples, which were of the same size.

A set of 5 incident angles was chosen for Ni and 4 angles for Ir and quartz in such a way that would fully cover the Q range with substantial overlap between the angles. The largest angles ensured that the range would extend into features at large Q, which become unresolvable due to vanishing statistics.

Table 2 shows the specific angles used, slit openings and measurement durations. Each direct beam measurement was repeated using a smaller optical aperture of F4—with 8 times lower light transmission than the F1.4 aperture used in the rest of the measurements. Smaller optical aperture allowed for reconstruction using the direct beam because of less dead time as described in the “Results” section below. After the LumaCam measurements were finished, the \(^3\)He detector was reinstalled, and measurement series was repeated. An exception was the direct beam, since it was known from previous experience with ASTERIX that a reliable direct beam measurement cannot be made for any but the smallest beam collimations. Therefore, only one data set was taken of the direct beam with the \(^3\)He detector using vertical slit opening equal to that used for the smallest incident angle. The horizontal slit opening was further reduced by half in order to avoid detector dead time. This data set was used to normalize all of the \(^3\)He measurements. For each measurement, counts from a beam monitor were collected, and the total charge of the proton beam on the spallation target was recorded. This information was used to normalize the measurements. It should be noted that from previous experience on ASTERIX, it was known that the beam profile is sufficiently homogeneous, so that the beam wavelength spectrum is essentially independent on the slit opening. This allows for accurate reconstruction of the beam spectrum using a much smaller slit opening than openings used for reflectivity. Such an assumption does not hold true in general, and, in particular, will be false on instruments where supermirror guides are used to transport the neutron beam.

Approximately half a day was needed to measure each of these samples. An instrument with much higher flux and the ability to measure the entire range in a single setting, such as QIKR, would offer transformative capability to this type of neutron scattering science.

Data from the LumaCam were acquired using the Serval software19; raw data were saved for all measurements. As an indication, approximately 1 GB of raw data were produced per day of using the LumaCam on ASTERIX. Note that this number will scale with the beam flux. The raw data files contain pixel hits including any pixels that had signal over threshold regardless of spatial and temporal distribution. In addition to pixel hits, time zero, \(T_0\), signals coincident with the source pulse were recorded as special events. Software, written specifically for the LumaCam and first used in12 was running in parallel to reduce the data to neutron hits and generate time-dependent images. Two data processing steps were used. The first finds clusters of typically 3-10 pixel hits within a narrow time window and identifies them as single photon hits (recall that the image intensifier produces up to a million photons for each primary scintillation photon, resulting in a cluster of pixel hits of varying intensity). The second step searches for photons that were emitted from a single neutron capture in the scintillator. Typically, for the \(\hbox {ZnS:}^6\)LiF scintillator used, a search radius of 3 to 4 Timepix pixels and a time window up to 0.5 ms were used. Events with at least 3 photons were defined as neutrons, while those with 1 or 2 photons were rejected, as these are likely to be gamma rays and scintillator afterglow. An additional pulse shape discrimination feature was enabled to reject events shorter than 5 \(\upmu\)s as gamma rays, using the pulse shape discrimination feature of \(\hbox {ZnS:}^6\)LiF22,23. Finally, image stacks were generated for each complete run. An example of such an image is shown in Fig. 4. The ToF is determined as the time since the last \(T_0\) event, resulting in a spectrum such as in the right panel of the figure. Once raw data processing methods are fully developed, raw data storage, which includes every pixel activation, would be unnecessary. It will be sufficient to store only the list-mode neutron data with reconstructed positions and time-of-flight of each detected neutron.

Results

The bulk of the analysis was performed on the Ni sample due to larger statistics and prominent features throughout the Q range. Regions of interest were defined capturing the reflection, such as shown in Fig. 4. Background regions were selected above and below the reflection and subtracted from the reflected data. Measurements at different incident angles contribute a section of the full Q range. Each one is normalized using the direct beam measured at the same beam setting with the sample out of the beam and the detector at 0-degree position. This operation compensates for any detection efficiency variations with \(\lambda\). The measured spectra and normalization are shown in Fig. 5. Plotting each data set in Q scale yields a reflectivity profile shown in Fig. 6, where data from the \(^3\)He detector is shown for comparison. Data from the two detectors are offset in the figure for visibility, however, both qualitatively show the same features. The calculated curve using the parameters deduced from fitting the data is overlaid with the data. The data at shorter wavelength has poorer resolution than at the longer wavelength. This is an effect that is not related to detector performance, but rather to the resolution of the emission and travel times of neutrons of varying wavelength from the moderator. Figure 7 shows the data and fits from the third (1.23 degree) and fourth (3.43 degree) angle fits only. The variation of the instrument resolution with wavelength was taken into account while modeling the reflectivity. We see that the fringes are more smeared out in the large-Q (small \(\lambda\)) side of the 1.23-degree curve than in the low-Q (large \(\lambda\)) side of the 3.43-degree curve. Since such datasets with different resolutions cannot be directly combined, data were fitted for each range separately. This is visible in the two fitted curves in Fig. 7. The parameters for the fit were deduced from each LumaCam and \(^3\)He detector. These are presented in Table 3. We see that both detectors produced the same fits to within statistical uncertainty. The data presented in this section used a normalization by a small direct beam for both detectors in order to minimize the effects of detector saturation.

Data in the Ni reflectivity measurement at 5 incident angles. Top: reflected beams. Middle: direct beams. Bottom: reflected to direct beam ratio. Here, the T0 position has been adjusted so that the time frame begins at T0 (i.e. fastest neutron are on the left, slowest on the right). Note the rate units, 1/mC/s, chosen to facilitate scaling each measurement by the total proton charge on target.

Ni reflectivity data using only angles 3 and 4 measured by the LumaCam and the \(^3\)He detector. The overlap of the datasets from these angles shows the difference in resolution for low- and high-Q parts of the spectra. The low-Q part of the fourth angle measurement shows sharper fringes, while the fringes on the high-Q side of the third measurement are more smeared out. Reflectivity value has been multiplied by \(q^4\) in order to amplify the details.

Light collection efficiency and rate capability

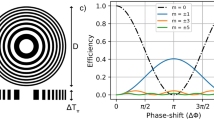

The ability to select the lens aperture and thus change the amount of light that the detector collects is a unique feature of the LumaCam. To be clear, this is the same type of an aperture that a photographer adjusts on a system camera by turning an aperture ring on their lens or by adjusting a setting in the camera menu. In the LumaCam, typically a fully manual lens is used. Focus, aperture and focal length (in case of a zoom lens) can be adjusted on the lens while the camera enclosure is open. The adjustments can potentially be automated if flexibility from one measurement to another is desired.

Typically, in a radiation detector, the maximum fraction of the primary signal should be collected. Any subsequent amplification stage would be chosen to obtain an output signal at a level suitable for the data acquisition system. The situation is different in a photon-counting detector. As each photon is detected individually, additional photons cost more in terms of data throughput of the sensor. ZnS:Ag:\(^6\)LiF emits up to 160,000 photons per neutron (75,000 in ZnO:Zn). Photons are emitted isotropically and from a range of depths in the scintillator. Considering the distance to the lens and the dimensions of its front element, we expect to collect about 1.5% of all photons while the aperture is fully open (F1.4 for the 85 mm lens used)—potentially up to 2400 photons. This number will be greatly reduced due to imperfect transmission of the optics (unknown magnitude), quantum efficiency of the photo cathode of the image intensifier (0.25), non-uniform energy deposition within the scintillator grains, as well as attenuation due to the self-absorption in the scintillator. Post-intensifier, further photons may be lost due to the variations of brightness of the intensified light and other losses. In practice, we could see neutron events containing up to about 50 photons. Events with more light are rare and are likely to be pile up of multiple neutrons.

The Timepix3 ASIC detects not just single photons, but bursts of light from the phosphor of the image intensifier. The manufacturer of the intensifier specifies photon gain of up to 800,000, which can be reduced by lowering the MCP voltage if needed. This burst triggers a cluster of several Timepix pixels. We use the cluster information to define photon interaction position with sub-pixel resolution. A typical number of pixels in a cluster is approximately 5; on the order of 10 photons on average are detected per neutron event, meaning that a typical neutron event can cause 50 pixel hits. Therefore, the system has to deal with a pixel rate that is 50 times greater than the already-challenging neutron rate. It is therefore beneficial to reduce the light collection and the image intensifier gain to the minimum value that still gives a good efficiency. It may even be beneficial to restrict the light collection beyond that. This can be done by using a smaller aperture (referred to as F-stop in photography) of the lens. Consider a neutron rate where the detector is saturated due to pile-up, resulting in inability to separate neutrons from each other. This causes serious performance degradation, which has a ToF, and thus wavelength, dependence (see Fig. 1), resulting in spectral distortion. On the other hand, by limiting the amount of light, we can select only the peaks of the brightest events affecting all parts of the spectrum equally, regardless of the instantaneous rate. Severe pile-up and afterglow may still conspire to cause overlap of some events, but the effect is expected to be be far less frequent.

It should be noted that there is an effect that can cause a minor non-linearity in the ratio of spectra from a small and a large aperture. Incoming neutrons of varied wavelength will have a slightly different average depth of interaction in the scintillator. Longer wavelengths will absorb closer to the front of the scintillator and shorter wavelengths will penetrate deeper. The latter ones will thus have an increased apparent light yield due to the proximity to the observed face of the scintillator. This effect can be minimized using a thin scintillator. A thin 200 \(\upmu\)m scintillator was used in this work. Its expected neutron absorption probability is 49% at 4 Å and 81% at 10 Å.

To test reduced light collection, the direct beam measurements were repeated using an aperture of F4. In the language of photography, this has the effect of reducing light by 3 F-stops, i.e. by a factor of 8. This setting was compared to the maximum aperture of the lens of F1.4. Note that all reflected beams were collected using only F1.4 data. Only the much more intense direct beams are compared at the reduced aperture. Figure 8 shows the effect of saturation. The drop in the counts between 4 and 5 Å is visible in the Ni4 and Ni5 F1.4 measurements. The effect is strongest for the most intense direct beams with the widest slit openings. Taking a ratio between the F1.4 and F4 reveals that the effect is present over at least half of the wavelength range. This is caused by pile-up effects which are more severe in the F1.4 data.

Left: Direct beam spectra measured at F1.4 and F4. The spectra have been re-scaled for ease of comparison. The insert magnifies the peak flux region showing the drop in the F1.4 measurement at the peak of the flux for angles 4 and 5 (the two most intense settings). Right: Ratio of direct beam measurements taken at F1.4 and F4. Ni 1 through Ni 5 refer to the 5 direct beam settings corresponding to the 5 incident angles used with the Ni sample. Where Ni 1 is the smallest angle and the least intense direct beam.

The fact that a measurement at a smaller aperture reduces efficiency in a controlled way gives us a way to obtain spectral shape of the true neutron beam while avoiding saturation effects. The effects of wavelength-dependent attenuation when using neutron absorbers is thereby avoided. Figure 9 compares the reflectivity profiles where the normalization was performed using the direct beam measurements at F1.4 vs. F4, while keeping the reflected data from the F1.4 setting with maximum detection efficiency. The direct beams have been re-scaled in such a way that compensates for the reduced efficiency at F4, preserving the spectral shape.

Reflectivity reconstruction comparing results using direct beams measured at F1.4 and F4. The top dataset uses normalization by the second most intense direct beam instead of using each of the respective direct beam setting in a manner similar to the \(^3\)He data, where an even lower setting of the direct beam is used for normalizing each reflection. Reflectivity value has been multiplied by \(q^4\) in order to amplify the details.

Figure 9 compares four reflectivity reconstruction methods. Reflectivity for each is plotted offset by a factor of 10 for visibility. From top to bottom, the datasets are:

-

LumaCam reconstruction using the direct beam in angle 2 setting to normalize each of the 5 reflected beams.

-

LumaCam reconstruction using direct beams measured with F1.4 from each angular setting to normalize each corresponding reflection.

-

As above but using direct beams measured at F4.

-

\(^3\)He data using the smallest direct beam setting to normalize data from each angular setting.

We can observe that the first and third LumaCam dataset corresponds closer to the model than the second just above \(Q=0.1\). Recall that the second dataset, the direct beam data from the fourth angle setting is used. As we have seen in Fig. 8, this dataset suffers from saturation and thus deviation from linearity. On the other hand, the first and third datasets use direct beam measurements with no visible saturation. In the first case, the direct beam from a small direct beam setting and in the second case, a large beam, but measured at a lower efficiency using F4 aperture. A smaller level of deviation can be seen also above \(Q=0.15\) in the 1st and 3rd LumaCam data curves as well as in the He3 detector, 4th curve. However, in this region, all data sets behave less predictably, due to the rapidly diminishing signal statistics in the reflected data for these large Q values. The comparison is therefore focused on the Q range between 0.1 and 0.15 Å\(^{-1}\).

It is clear that in ASTERIX, it is indeed not necessary to measure direct beams for each intensity, since the spectral shape remains the same regardless of the collimation. Therefore, the lowest beam setting used allows adequate normalization for each incident angle and beam collimation. Using the F4 measurements, we have performed the analysis of the LumaCam data in such a way that we do not rely on this convenient property of the beam. On other reflectometers, such as Liquids Reflectometer and Magnetism Reflectometer at SNS, of future QIKR at STS10, this simplification would not be possible.

The maximum instantaneous rates measured can be found at the peak of the direct beam, see Fig. 5. Since the maximum instantaneous rate reached \(2 \times 10^4 \,\)n mC\(^{-1}\, \textrm{s} ^{-1}\), and the total beam charge was 44 mC, the detector reached 880 kHz. Considering the 1.23 degree curve, which shows negligible deviation from linear behaviour with rate and reaches \(2 \times 10^3 \,\)n mC\(^{-1}\, \textrm{s} ^{-1}\), we know a rate of 88 kHz can be used with the current version of the system with no special corrections for pile-up at F1.4. Using the F4 setting, the peak instantaneous rate was 250 kHz at the fourth angle setting. Considering the arguments above, this rate can reliably be used. The direct beam F4 measurement at the 5th angle setting reached 500 kHz, however, it is more difficult to make a definitive conclusion about the linearity based on the quality of the reconstructed reflectivity because it is limited by low statistics of the reflected beam.

As mentioned in the introduction, other new detector technologies are being developed for reflectometry, primarily with the goal of improving counting rate capability over more conventional approaches. The other notable new technologies are scintillator wavelength-shifting fibre, WLSF, detectors developed at ISIS Muon and Neutron Source7 and the Multi-Blade, MB, detector developed at the European Spallation Source8. A comparison of rate performance is complicated by the differences in detection physics and in readout architecture of these three technologies. The WLSF detectors are primarily limited by the afterglow of the scintillator within the area of a readout element (pixel or strip). The MB is a gas detector and is mainly limited by charge transport. In the LumaCam, the current through the MCP of the image intensifier and the readout throughput of the Timepix3 ASIC set limitations. Both of these are still being worked on and are expected to increase by at least an order of magnitude. Indicative rate values for the WLSF detector on INTER are 450 cps per \(\hbox {mm}^2\) or 16 kcps per fibre channel and 2 Mcps globally7. The MB has been shown to handle up to 13 kcps per \(\hbox {mm}^2\), or 300 kcps per cassette locally and 2 Mcps globally24. The three technologies further differ in readiness level. WLSF detectors are already installed on the INTER and OffSpec reflectometers at ISIS, following the experience from many other instruments at that facility. The MB has been in development for reflectometry for several years, and is now installed at AMOR at PSI24. LumaCam has been used extensively for imaging, however, this work is the first demonstration of its viability for reflectometry. Performance of these detectors in a real instrument will be different and not easily described by a singular rate capability characteristic. This paper demonstrates that an extreme rate capability may not even be necessary in the case of the LumaCam as an elegant solution involving an adapted efficiency may be used to handle rate maxima. Further, due to the physical difference between the technologies outlined above, the limitations will scale differently with detector area, pixel area and pixel number. We hope to be able to perform a comprehensive side-by-side comparison on a reflectometer in a future study, demonstrating real-world advantages of the respective technologies.

Prompt pulse handling

The so-called prompt pulse is a significant source of background at spallation neutron sources20,21. The impact of the GeV proton beam on the spallation target produces particles with energies up to the primary proton energy. While the best effort is made to moderate as many neutrons as possible and shield the rest, some fast neutrons do make it to the instrument end stations. In detector data, the prompt pulse manifests itself as a rapid spike in counts at T0 with a roughly exponential falling edge. A thermal neutron detector can be sensitive to several components of the prompt pulse: fast neutrons converting in the detector, fast neutrons generating gamma-rays at the end-station, fast neutrons moderating on various materials at the instrument end-station and becoming thermal, which in turn trigger the detector. The latter component involves slowed down neutrons and is therefore responsible for the gradual fall-off of the prompt pulse. The exact blend of these effect is difficult to determine. An analysis of the prompt pulse is further complicated by its time-focused nature which causes severe pile-up effects making individual interactions difficult to distinguish. The magnitude of the prompt pulse was large at ASTERIX. This instrument does not have features present at more modern reflectometers that help mitigate the direct radiation from the target. The SNS reflectometers, as well as future QIKR have curved guides which steer useful neutrons out of the line-of-sight of the target. Other instruments employ a T0 chopper which uses a massive rotating absorber to block high-energy particles at T0 and for a short time after. The measurement at ASTERIX, therefore, represents unusually challenging prompt pulse conditions for a neutron detector.

A part of the prompt pulse can be seen in the ToF spectrum in Fig. 4, right panel. The last bin (500) of the spectrum and the first few bins are off the scale in the figure. The fall off of the prompt pulse can be seen in bins 3 to 20. The prompt pulse appears to start at the end of the time frame because the T0 signal takes slightly longer to propagate through the electronics than the flight time of the high-energy particles from the target to the detector. Taking advantage of the 2-D position sensitivity of the LumaCam, it was possible to trace the effect of the prompt pulse to a roughly circular spot around the beam axis. It is visible in the image when measuring the reflection at a small angle, or when measuring the direct beam. This halo is only present during the few time bins, less than 1 ms corresponding to T0 and shortly after. Figure 10 shows an example image of the beam during and after the prompt pulse.

The presence of the prompt pulse makes the coincident range of data unusable. This is true in any detector that could be used. Note the gap in the data between 9 and 10 Å in Fig. 5. In the present setup, the prompt pulse was somewhat exacerbated since only minimal shielding could be mounted around the LumaCam, compared to the \(^3\)He detector which was encased in approximately 15 cm of borated high-density polyethylene—an efficient absorber of both fast and thermal neutrons. An additional effect that somewhat prolonged the prompt pulse in the LumaCam is the afterglow of the \(\hbox {ZnS:Ag/}^6\)LiF, since delayed photons that follow the bright flash during T0, are often numerous enough to be misidentified as neutron events. This latter effect is expected to improve significantly with a faster scintillator, such as \(\hbox {ZnO:Zn/}^6\)LiF22,23.

The discussion of the full range of background effects, including gamma sensitivity, will be a subject of a dedicated publication.

Future outlook and conclusion

The present experiment at ASTERIX demonstrated that the new LumaCam detector significantly improves on the current reflectometry detectors. Nevertheless, it is far from its maximum potential. Further improvements are planned in several aspects. On the immediate time scale, tests are planned with the new \(\hbox {ZnO:Zn/}^6\)LiF scintillator. This scintillator resembles \(\hbox {ZnS:Ag/}^6\)LiF used presently, however, its light output is somewhat lower, while the afterglow is significantly shorter22,23. This will greatly reduce the chance of event clusters merging as well as reduce the overall pixel hit rate in the Timepix sensor. Further improvements can be made in the image intensifier sensitive area by using a larger MCP. The optics system will be improved to transport light more efficiently from the intensifier phosphor to the ASIC, thus reducing the required MCP gain. With such improvements, we expect a considerable reduction in the MCP dead time. On a longer time scale, the Timepix4 ASIC25, which is already in development, will deliver more than an extra order of magnitude in count rate as well as increase the sensor area and pixel count by a factor of 3.5. While the pixel dimensions of Timepix4 remain unchanged at 55 \(\upmu\)m, projecting an image onto a larger sensor will help alleviate local saturation. With a combination of these enhancements, a count rate of around 10 MHz can be anticipated—an unprecedented capability for a detector with this area, pixel size and, importantly, cost.

The detector technology used in the LumaCam can easily be adapted to accommodate various neutron scattering instruments. Fields of view from \(7 \times 7\) \(\hbox {mm}^2\) to \(200 \times 100\) \(\hbox {mm}^2\) have already been tested in various studies (manuscripts are currently in preparation). These include diffraction, imaging, spin-echo and, now, reflectometry. It is likely that with a suitable modification, small angle neutron scattering, SANS, can also be accommodated, possibly using tiled arrays of similar detectors. Reflectometry has been a class of neutron scattering instruments where a compromise between quality of data and measurement statistics had to be struck. The present results applying the LumaCam to reflectometry suggest that this trade-off will become far more favourable at QIKR and other instruments.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Penfold, J. & Thomas, R. K. The application of the specular reflection of neutrons to the study of surfaces and interfaces. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2, 1369. https://doi.org/10.1088/0953-8984/2/6/001 (1990).

Parratt, L. G. Surface studies of solids by total reflection of X-rays. Phys. Rev. 95, 359–369 (1954).

Tolan, M. & Press, W. X-ray and Neutron Reflectivity (Universitat Kiel, Institut fir Experimentelle Angewandte Physik, 1998).

Boie, R. A. et al. Two-dimensional high precision thermal neutron detector. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. 200, 533–545 (1982).

Kampmann, R. et al. Design and performance of a two-dimensional multi-wire neutron detector with a sensitive area of 50 × 50 \(\text{ cm}^2\) and a spatial resolution of 2 × 2 \(\text{ mm}^2\). Phys. B Condens. Matter 350(1–3), 845–848 (2004).

Marchal, J. et al. First measurements with the new 3He-filled Monoblock Aluminium Multitube neutron detector developed at the ILL for ANSTO PLATYPUS reflectometer. J. Neutron Res. 23, 53–67. https://doi.org/10.3233/JNR-200179 (2021).

Mauri, G. et al. Enhanced position resolution for ZnS:Ag/6 LiF wavelength shifting fibre thermal neutron detectors. NIMA 1039, 167052. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.13109933 (2022).

Mauri, G. et al. The Multi-Blade Boron-10-based neutron detector performance using a focusing reflectometer. JINST 15, P03010 (2020).

Chong, S.-A. et al. The development of a 6Li-based pixelated neutron detector for neutron reflectometry at the Spallation Neutron Source. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 1039, 167052. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2022.167052 (2022).

Ankner, J. F. et al. Cinematic reflectometry using QIKR, the quite intense kinetics reflectometer. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 94, 013302. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0122279 (2023).

Aoki, H. et al. Neutron Reflectometry Tomography for Imaging and Depth Structure Analysis of Thin Films with In-Plane Inhomogeneity. Langmuir 37, 196–203. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.langmuir.0c02744 (2021).

Losko, A. S. et al. New perspectives for neutron imaging through advanced event-mode data acquisition. Sci. Rep. 11, 21360. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-00822-5 (2021).

Jäger, T. T. et al. Demonstration of neutron time-of-flight diffraction with an event-mode imaging detector. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 57(4), 1107–1114 (2024).

Funama, F. et al. Scintillator-based Timepix3 detector for neutron spin-echo techniques using intensity modulation. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 95, 033304 (2024).

Sykora, G. J. et al. Gamma sensitivity of a ZnS:Ag(6-LiF) wavelength shifting fiber neutron detector in mixed neutron-gamma fields. IEEE NSS/MIC (2012).

Frojdh, E. et al. Timepix3: First measurements and characterization of a hybrid-pixel detector working in event driven mode. JINST 10, C01039. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-0221/10/01/C01039 (2015).

Dubey, M. et al. SPEAR-ToF neutron reflectometer at the Los Alamos Neutron Science Center. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 126, 110. https://doi.org/10.1140/epjp/i2011-11110-1 (2011).

Kopp, M. K. et al. New gas mixture improves performance of 3He neutron counters. NIMA 201, 395–401 (1982).

Amsterdam Scientific Instruments, ASI. https://amscins.com/

DiJulio, D. D. et al. Characterization of the radiation background at the Spallation Neutron Source. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 746(1), 12033 (2016).

Cherkashyna, N. et al. Overcoming high energy backgrounds at pulsed spallation sources. arXiv:1501.02364 (2015).

Sykora, G. J., Schooneveld, E. M. & Rhodes, N. J. ZnO:Zn/\(^6\)LiF, scintillator—A low afterglow alternative to ZnS:Ag/\(^6\)LiF for thermal neutron detection. NIMA 833, 75–82 (2018).

Mann, S. E. et al. Position sensitive ZnO:Zn neutron detector—A high count rate alternative to ZnS:Ag scintillation detectors. NIMA 1057, 168716 (2023).

Piscitelli, F. et al. Multi-blade detector with VMM3a-ASIC-based readout: Installation and commissioning at the reflectometer Amor at PSI. JINST 19, P05010 (2024).

Llopart, X. et al. Timepix4, a large area pixel detector readout chip which can be tiled on 4 sides providing sub-200 ps timestamp binning. JINST 17, C01044. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-0221/17/01/C01044 (2022).

Acknowledgements

Notice: This manuscript has been authored by UT-Battelle, LLC, under contract DE-AC05-00OR22725 with the US Department of Energy (DOE). The US government retains and the publisher, by accepting the article for publication, acknowledges that the US government retains a nonexclusive, paid-up, irrevocable, worldwide license to publish or reproduce the published form of this manuscript, or allow others to do so, for US government purposes. DOE will provide public access to these results of federally sponsored research in accordance with the DOE Public Access Plan (https://www.energy.gov/doe-public-access-plan). This work was performed, in part, at the Los Alamos Neutron Science Center (LANSCE), a NNSA User Facility operated for the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) by Los Alamos National Laboratory (Contract 89233218CNA000001). Research presented in this paper was supported by the Laboratory Directed Research and Development program of LANL under project number 20230592ER, the BMBF in the framework of the research project 05K22WO5. This research used resources of the Spallation Neutron Source, High-Flux Isotope Reactor and Second Target Station Project at ORNL. ORNL is managed by UT-Battelle LLC for DOE’s Office of Science, the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.K. conceived the experiments, A.K., J.F.A., E.W., M.L., and A.M.L. conducted the experiments and analysed the results. A.S.L. and A.W. built the detector and wrote the data acquisition software. A.K., A.M.L., A.W., A.S.L., G.J.S., S.C.V., and T.H. developed methods of neutron detection used. A.M.L., S.C.V., and E.W. operated the instrument. A.K. wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

A.S. Losko is the director of LoskoVision GmbH and A. Wolfertz receives a salary as an employee of LoskoVision GmbH. LoskoVision GmbH is a startup that offers detector solutions using technologies described in this work. All other authors report no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Khaplanov, A., Ankner, J.F., Hirsh, T.Y. et al. Advances in detection for neutron reflectometry with time-resolved imaging detectors. Sci Rep 15, 25014 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99927-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99927-4