Abstract

Frailty is a common geriatric syndrome that compromises quality of life and worsens health outcomes. The aim was to examine the effect of physical activity on frailty and to explore the potential mediating role of cognitive function. We used data from 11,751 adults aged ≥ 45 years from the 2018 China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). Frailty was measured using a Frailty Index, cognitive function with the MMSE, and physical activity categorized by total MET scores. Logistic regression assessed independent and joint associations. Restricted cubic spline analyses based on MMSE scores were conducted to explore nonlinear relationships and identify a cognition threshold (13 points). Mediation analysis with bootstrapping evaluated the mediating role of cognition, with subgroup analyses by sex, education, and residence. A total of 11,751 participants (mean age 60.46 ± 9.02 years) were included in the analysis, of whom 8.1% were classified as frail. Participants with frailty were older, had lower cognitive scores, shorter sleep duration, lower educational attainment, and were less physically active. Higher levels of physical activity were associated with a lower risk of frailty (OR = 0.30, 95% CI: 0.26–0.36), and each one-point increase in cognitive score was also linked to reduced frailty risk (OR = 0.89, 95% CI: 0.87–0.90). A nonlinear association was identified between cognitive function and frailty, with an inflection point at approximately 13 points on the MMSE-derived cognitive score, below which the risk of frailty increased more sharply. Mediation analysis showed that cognitive function partially mediated the association between physical activity and frailty, with a total effect of − 0.14 (95% CI: −0.16 to − 0.12), a direct effect of − 0.13 (95% CI: −0.15 to − 0.11), and an indirect effect of − 0.01 (95% CI: −0.02 to − 0.01), accounting for 8.37% of the overall association. Cognitive function partially explains how physical activity reduces frailty risk. This mediating pathway differs across population groups. Interventions promoting both physical and cognitive health may help delay frailty and support healthy aging.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Frailty is a geriatric syndrome characterized by reduced physical strength, fatigue, and diminished functional capacity1,2. It reflects a decline in an individual’s ability to adapt to physiological and environmental stressors, leading to significantly higher risks of falls, disability, hospitalization, and mortality3,4,5. Frailty is particularly prevalent among older adults6, with a larger proportion falling into a “pre-frail” state. Emerging evidence suggests that frailty can be prevented, delayed, or even reversed through appropriate interventions, highlighting its considerable potential for modification7. Consequently, mitigating the onset and progression of frailty has become a central issue in global public health and aging research. Currently, the Frailty Index (FI), developed based on the cumulative deficit model, is widely applied in both research and clinical settings and is considered more broadly applicable across older populations than traditional frailty criteria1,8,9.

Extensive research has emphasized the pivotal role of physical activity in the reversibility and modifiability of frailty10. Systematic reviews have shown that regular aerobic and resistance training can significantly improve muscle strength, gait, and overall physical performance in older adults, thereby helping to delay or reverse frailty progression11,12. At the same time, the link between cognitive impairment and frailty has gained increasing attention13. Growing evidence suggests that older adults with cognitive decline are more likely to experience impairments in judgment and execution, leading to disordered lifestyles and reduced physical activity, which in turn accelerate physiological deterioration14,15. Mechanistically, cognitive impairment may contribute to frailty through multiple interconnected biological and behavioral pathways. Cognitive decline has been linked to increased chronic inflammation and dysregulation of neuroendocrine and hormonal systems, which can accelerate physiological vulnerability. In addition, deterioration of the brain–muscle axis—affecting motor planning, coordination, and neuromuscular activation—may directly reduce physical function and increase susceptibility to frailty16.

Previous studies have demonstrated an association between cognitive impairment and frailty17. Using data from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS), prior studies have shown that cognitive impairment and lower physical activity are each associated with an increased risk of frailty among older adults18,19. Physical activity has been shown to enhance neuroplasticity, promote cerebral blood flow, and inhibit neuroinflammation, thereby improving cognitive performance and potentially mitigating frailty16,20. While previous studies have largely considered physical activity and cognitive function as independent predictors of frailty, few have formally explored the mechanisms linking these factors. Our study addresses this gap by examining whether cognitive function partially explains how physical activity influences frailty risk, using a large, nationally representative cohort and rigorous mediation analysis. By quantifying the indirect effect of cognitive function, we provide novel evidence that the protective effects of physical activity on frailty are, at least in part, channeled through cognitive pathways. This approach advances prior research by moving beyond simple associations to elucidate potential mechanisms, highlighting the importance of integrating cognitive health considerations into interventions aimed at reducing frailty.

With the rapid aging of the Chinese population21, understanding the determinants of frailty among middle-aged and older adults has become a pressing public health priority. Leveraging data from the 2018 wave of the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS), our study focuses on adults aged 45 years and older, providing a comprehensive and nationally representative perspective. By applying a mediation modeling approach, we aim to elucidate how physical activity may influence frailty risk through cognitive function, offering insights that can inform targeted interventions to promote healthy aging.

Materials and methods

Study sample

This study used publicly available data from the 2018 wave of the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). CHARLS is a nationally representative, large-scale longitudinal survey covering 28 provinces (including autonomous regions and municipalities) across China. It aims to collect comprehensive information on the health, economic status, and social conditions of Chinese adults aged 45 years and older22,23. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Peking University (IRB00001052-13074), and all participants or their proxies provided written informed consent. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations, including the Declaration of Helsinki.

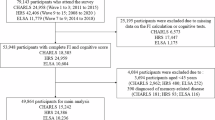

A cross-sectional study design was adopted. To focus on frailty among middle-aged and older adults, individuals aged 45 years and above in the 2018 wave were included. We excluded respondents with missing data on the Frailty Index or cognitive function assessments. Further exclusions were made for missing values in key covariates, including demographic characteristics and health behaviors. After these steps, a total of 11,751 participants were retained for the final analysis (Fig. 1).

Assessment of frailty

Frailty status was assessed using the Frailty Index (FI), based on the cumulative deficit model9. The FI incorporates variables across physical, psychological, and functional domains. Drawing from prior studies and available variables in the CHARLS dataset, we constructed an FI using 35 indicators, including chronic conditions, self-reported health status, functional limitations in daily living, and psychological well-being. Each item was scored as 0 (no deficit), 0.5 (intermediate deficit), or 1 (deficit present). The FI score was calculated by summing the deficits and dividing by the total number of items, resulting in a continuous score ranging from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating greater frailty.

Consistent with widely accepted thresholds, individuals with FI ≥ 0.25 were classified as frail, while those with FI < 0.25 were considered non-frail24. This cut-off has been validated in numerous studies involving older Chinese populations and is effective in identifying frailty status.

Assessment of cognitive function

Cognitive function was measured using items adapted from the Chinese version of the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), covering memory, orientation, attention, calculation, and visuospatial ability25,26. Memory was assessed through immediate and delayed word recall tasks. Mental status was evaluated via questions on temporal orientation (e.g., identifying date), serial subtraction, and figure drawing. The total cognitive score ranged from 0 to 21, with higher scores indicating better cognitive performance.

Assessment of physical activity

Physical activity (PA) levels were assessed via self-reported questionnaire items in CHARLS regarding frequency and duration of various physical activities. Each activity was assigned a metabolic equivalent of task (MET) value based on international standards27. Weekly total MET-minutes were calculated for each participant.

In line with the World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations, participants with total weekly PA ≥ 600 MET-min/week were categorized as having “sufficient physical activity,” while those with < 600 MET-min/week were classified as having “insufficient physical activity”28. This threshold reflects the minimum recommended activity level for maintaining health among middle-aged and older adults.

Covariates

Several demographic and health behavior-related covariates were included in the analysis: age (continuous), sex (male/female), education level (no formal education, primary school, junior high school and above), marital status (living with a spouse: yes/no), place of residence (urban/rural), alcohol consumption (never vs. ever, defined as any lifetime use) and smoking status (never vs. former/current), and average sleep duration (hours per day; treated as a continuous variable).

These covariates were selected based on theoretical relevance and previous literature to enhance model accuracy and control for potential confounding. Notably, variables such as chronic disease and self-rated health were not included as covariates, as they were already embedded within the FI. Detailed data collection procedures are available on the official CHARLS website.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 4.3.2; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

First, descriptive statistics were used to present the baseline characteristics of the study population. Continuous variables were expressed as means ± standard deviations (SD) and compared using t-tests or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), while categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages and compared using chi-square tests.

Multivariable logistic regression models were constructed to evaluate the independent associations of physical activity (PA) and cognitive function with frailty. Covariates included age, sex, marital status, education level, place of residence, smoking, and alcohol consumption. To further investigate potential non-linear associations between cognitive function and frailty, restricted cubic spline (RCS) regression models were fitted using the rms package in R, with four knots specified. Non-linear trends were visualized to identify possible threshold effects29.

For the combined effect of cognitive function and PA on frailty, a standard linear regression was used for the continuous frailty index, while a two-piece linear regression model was applied to examine potential threshold effects. Logistic regression models were used for all binary frailty outcomes.

Based on the identified threshold (score of 13), cognitive function was dichotomized into low (< 13) and high (≥ 13) levels. For the joint and interaction analyses, cognitive function was treated as a categorical variable based on this threshold. In contrast, the mediation analysis used the continuous cognitive score to capture the full range of cognitive function in estimating indirect effects. This variable was then combined with PA status to create a four-category joint exposure variable. Using the “low cognition + insufficient PA” group as the reference, we examined joint effects through logistic regression. Interaction between PA and cognitive function was tested by including a multiplicative interaction term (PA × Cognition) in the model, and the significance of the interaction was assessed using the likelihood ratio test.

Mediation analysis was conducted to examine whether cognitive function mediated the association between physical activity and frailty. This analysis was performed using the mediation package in R with 5,000 bias-corrected bootstrap resamples. The total effect, direct effect, and indirect (mediated) effect were estimated, and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported. The proportion mediated was calculated as the ratio of the indirect effect to the total effect, representing the relative contribution of the cognitive pathway30.

To assess the robustness and heterogeneity of the mediation effects, stratified mediation analyses were conducted across key subgroups, including age group, sex, marital status, education level, place of residence, and smoking and drinking status. The total, direct, and indirect effects, as well as the proportion mediated, were reported for each stratum, enabling comparison of mediation strength across subpopulations.

All statistical tests were two-sided, and a P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Descriptive analysis

The final analytic sample consisted of 11,751 participants, with 10,794 (91.9%) classified as non-frail and 957 (8.1%) as frail. Significant between-group differences were observed in age, sleep duration, sex, marital status, education level, residence, physical activity, smoking, and alcohol consumption (all P < 0.05). Detailed distributions of these variables are shown in Table 1.

Participants with frailty were generally older, had lower cognitive function scores, and reported shorter sleep duration compared with those without frailty. Frailty was more prevalent among women than men (60.19% vs. 39.81%). Individuals with frailty were also less likely to be married and more likely to have lower educational attainment. Urban residents showed a slightly higher prevalence of frailty compared with rural residents (61.65% vs. 38.35%). In terms of lifestyle factors, frail participants were less physically active and had lower rates of alcohol consumption. Although the proportion of smokers differed only modestly between groups, non-smokers were more common in the frailty group.

Association between cognitive Function, physical Activity, and frailty

In the unadjusted models, cognitive function was significantly inversely associated with frailty risk. The overall odds ratio (OR) was 0.84 (95% CI: 0.83–0.86, P < 0.001), with similar associations observed across age groups: OR = 0.86 (95% CI: 0.84–0.89, P < 0.001) for participants under 65 years, and OR = 0.85 (95% CI: 0.83–0.88, P < 0.001) for those aged 65 and above. After adjusting for sociodemographic and lifestyle confounders, the inverse association remained robust (overall OR = 0.89, 95% CI: 0.87–0.90, P < 0.001). Stratified results were OR = 0.91 (95% CI: 0.88–0.93, P < 0.001) for < 65 years and OR = 0.87 (95% CI: 0.84–0.89, P < 0.001) for ≥ 65 years.

In addition, physical activity showed a strong protective association with frailty. In the unadjusted model, individuals engaging in physical activity had a substantially lower risk of frailty compared with those without physical activity (overall OR = 0.27, 95% CI: 0.23–0.31, P < 0.001). Similar protective effects were observed across subgroups, with OR = 0.35 (95% CI: 0.27–0.44, P < 0.001) among participants younger than 65 years and OR = 0.27 (95% CI: 0.22–0.33, P < 0.001) among those aged 65 years and older. After adjusting for sociodemographic and lifestyle variables, the association remained robust. The adjusted OR was 0.30 (95% CI: 0.26–0.36, P < 0.001) for the total population, 0.34 (95% CI: 0.26–0.43, P < 0.001) for participants under 65 years, and 0.28 (95% CI: 0.22–0.34, P < 0.001) for those aged 65 and above, indicating a consistent protective effect of physical activity (Table 2).

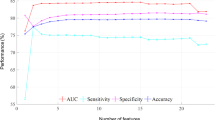

The restricted cubic spline (RCS) analysis further revealed a significant nonlinear association between cognitive function and frailty. Evidence of nonlinearity was observed in the overall sample (P for nonlinearity = 0.004), as well as in both age subgroups (< 65 years: P = 0.011; ≥65 years: P = 0.046). The risk of frailty increased steeply with lower cognitive scores, particularly in the lower range of cognitive performance (Fig. 2).

Joint association and interaction between cognitive Function, physical Activity, and frailty

A two-piece linear regression model (Model 2) was then used to explore potential threshold effects. The results identified a significant inflection point at a cognitive score of 13 (P for likelihood test = 0.001). Below this threshold, each point increase was associated with a 9% reduction in frailty risk (OR = 0.91, 95% CI: 0.88–0.94, P < 0.001), while above the threshold, the reduction increased to 20% (OR = 0.80, 95% CI: 0.72–0.89, P < 0.001), suggesting a stronger protective effect at higher cognitive levels (Table 3).

Based on this threshold, cognitive function was categorized as low (< 13) or high (≥ 13), and a joint variable was constructed combining cognitive level and PA status. Using the “low cognition + inactive” group as the reference (OR = 1.00), logistic regression showed that “low cognition + active” individuals had significantly lower frailty risk (OR = 0.31, 95% CI: 0.25–0.38, P < 0.001). Those with “high cognition + inactive” also showed reduced risk (OR = 0.53, 95% CI: 0.39–0.71, P < 0.001), while the “high cognition + active” group had the lowest risk (OR = 0.16, 95% CI: 0.12–0.20, P < 0.001). These findings indicate that both high cognition and sufficient PA independently reduce frailty risk, and their combination confers the greatest protection (Table 4).

Interaction analysis further explored whether the effect of one factor depended on the level of the other. In unadjusted models, the interaction term (Cognition × PA) was statistically significant (OR = 0.88, 95% CI: 0.87–0.89). However, after adjusting for confounders, the interaction was no longer significant (P = 0.718; OR = 0.99, 95% CI: 0.95–1.04). Despite the lack of a significant interaction in the adjusted model, both cognitive function (OR = 0.91, 95% CI: 0.88–0.94) and PA (OR = 0.49, 95% CI: 0.32–0.76) remained independently associated with lower frailty risk (Table 5).

Mediation analysis of cognitive function in the association between physical activity and frailty

To further explore whether physical activity (PA) reduces frailty risk indirectly through improved cognitive function, a mediation analysis was conducted. This aimed to clarify the potential pathway through which PA influences frailty.

As shown in Table 6, cognitive function significantly mediated the association between physical activity (PA) and frailty. The estimated indirect effect was − 0.01 (95% CI: −0.02 to − 0.01; P < 0.001), accounting for 8.37% of the total effect. The direct effect of PA on frailty remained significant at − 0.13 (95% CI: −0.15 to − 0.11; P < 0.001), explaining 91.63% of the total effect. Overall, the total effect of PA on frailty was − 0.14 (95% CI: −0.16 to − 0.12; P < 0.001), indicating that PA reduces frailty risk through both direct and indirect pathways (see Fig. 3).

Subgroup analyses

To assess the robustness and heterogeneity of the mediation effect across different populations, stratified mediation analyses were performed based on key sociodemographic characteristics, including age, gender, marital status, education level, residence type, smoking, and alcohol use.

Results showed that the total and direct effects of PA on frailty remained significant in all subgroups, and the mediating effect of cognitive function was also consistently observed. However, the proportion mediated varied across subgroups. Notably, the mediation effect was relatively stronger among women, individuals with higher education levels, and urban residents, suggesting population-specific differences in the cognitive pathway linking PA and frailty (Table 7).

Discussion

This study, based on nationally representative data from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS), calculated a frailty index and systematically examined the associations of physical activity and cognitive function with frailty, further exploring the mediating role of cognitive function in this relationship.The results demonstrated that higher levels of PA and better cognitive performance were significantly associated with a reduced risk of frailty. Moreover, cognitive function partially mediated the effect of PA on frailty, highlighting that the protective effects of PA may operate not only directly but also indirectly through cognitive pathways. This finding advances prior research by moving beyond independent associations to clarify a potential mechanism, emphasizing the importance of integrating cognitive health in interventions aimed at frailty prevention.

First, we observed a significant inverse relationship between PA and frailty, which is consistent with findings from numerous studies both in China and globally31. For instance, studies on older adults in Japan have shown that regular PA can substantially reduce frailty risk32,33. Similarly, Trevisan et al. found that older adults engaging in moderate to vigorous PA had a significantly lower prevalence of frailty than sedentary individuals, suggesting that physical activity plays an important role in preventing frailty and slowing its progression34. By adjusting for sociodemographic and behavioral covariates, our study further confirmed the independent protective effect of PA against frailty, underscoring its fundamental role in frailty prevention.

Second, we found a nonlinear association between cognitive function and frailty, with a threshold effect around a cognitive score of 12–13. This suggests that improvements in cognitive function are associated with a reduction in frailty risk, with individuals having higher baseline cognitive scores experiencing a stronger protective effect. This finding expands on previous research linking cognitive impairment—particularly executive dysfunction and memory decline—to increased frailty risk20,35,36,37. The use of restricted cubic spline (RCS) models to characterize the nonlinear association adds novelty and methodological rigor to this study.

The joint analysis showed that PA and cognitive function each independently and complementarily contributed to frailty prevention. Individuals with both high cognitive function and sufficient PA had the lowest risk of frailty. This finding is consistent with the “body–brain interaction” theory, which conceptualizes frailty as a multidomain phenotype in which cognitive and physical functions influence and reinforce one another through shared biological pathways, such as chronic inflammation, endocrine and hormonal dysregulation, vascular pathology, and degeneration of the neuromuscular axis. Maintaining cognitive resilience and preserving physiological reserves may therefore act synergistically to delay functional decline17. Our findings provide empirical evidence supporting the applicability of this theory in the Chinese older adult population. Evidence from the LIFE randomized clinical trial further supports this perspective, as a 24-month structured, moderate-intensity physical activity intervention significantly reduced the incidence of major mobility disability among older adults at risk. Although the trial primarily targeted physical outcomes, its results underscore the capacity of sustained physical activity to enhance physiological reserve and slow functional deterioration, providing additional empirical support for the synergistic interplay between cognitive and physical health in mitigating frailty38.

Importantly, the mediation analysis revealed that cognitive function partially mediated the effect of PA on frailty, accounting for 8.37% of the total effect. Although the proportion was modest, the indirect effect was statistically significant, suggesting that PA may promote cognitive health via mechanisms such as enhanced neuroplasticity, improved cerebral blood flow, and modulation of neuroinflammation39,40, thereby indirectly reducing frailty risk. These results contribute to the growing literature on the brain–body axis41,42,43 and highlight the potential of integrated interventions targeting both cognitive and physical domains in frailty prevention.

Furthermore, stratified mediation analyses revealed heterogeneity in the indirect effect across subpopulations. The mediating role of cognition was more pronounced among women, individuals with higher educational attainment, and urban residents—patterns consistent with prior research showing that women and those with greater educational resources tend to have higher health literacy, stronger engagement in cognitively stimulating activities, and greater access to health-promoting environments, all of which support cognitive resilience and healthier aging44,45,46. These findings suggest the need for tailored intervention strategies that account for population-specific characteristics to improve frailty outcomes more precisely.

From a practical perspective, our findings support the use of integrated physical activity programs that combine physical and cognitive stimulation for frailty prevention. Mind–body exercises such as Tai Chi and dual-task training (e.g., walking combined with simple cognitive tasks) may be particularly suitable for older adults, as they simultaneously engage motor and cognitive functions. These approaches align with our mediation findings, suggesting that targeting both physical activity and cognitive function may enhance the effectiveness of frailty prevention strategies.

Despite the strengths of this study, including a large nationally representative sample and rigorous analytic approach, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the cross-sectional design precludes causal inference. Future studies using longitudinal data are needed to validate the causal pathways. Second, cognitive function was assessed using a simplified instrument, which may not fully capture the complexity of cognitive status. Third, this study focused on a binary classification of frailty (frail vs. non-frail) and did not separately classify pre-frail individuals, which represents a limitation and may have provided additional insights into the progression of frailty. Lastly, although key sociodemographic and behavioral variables were adjusted for, unmeasured factors such as nutritional status, depressive symptoms, social support, and chronic inflammatory conditions may still confound the observed associations. Moreover, this study did not examine whether physical activity might itself mediate the association between cognitive function and frailty, an alternative pathway that could be explored in future research.

Conclusion

This study provides robust evidence for a significant inverse association between physical activity and frailty and identifies cognitive function as a partial mediator in this relationship. The findings suggest that PA not only directly reduces the risk of frailty but may also exert an indirect protective effect by enhancing cognitive function, supporting the hypothesized “PA–Cognition–Frailty” pathway. Dual-targeted interventions that promote both physical and cognitive health may offer an effective strategy to delay frailty and foster healthy aging. Future research and policy efforts should consider integrating cognitive and physical health promotion into comprehensive aging strategies to better address the challenges of rapid population aging.

Data availability

The data used in this study are publicly available from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) repository: http://charls.pku.edu.cn/en. All data are de-identified and can be accessed upon request through the official website.

Abbreviations

- CHARLS:

-

China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study

- FI:

-

Frailty Index

- PA:

-

Physical Activity

- RCS:

-

Restricted Cubic Spline

- OR:

-

odd ratio

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- P:

-

P-value

- MET:

-

Metabolic Equivalent of Task

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Fried, L. P. et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J. Gerontol. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 56, M146–M156 (2001).

Collard, R. M., Boter, H., Schoevers, R. A. & Oude Voshaar, R. C. Prevalence of frailty in community-dwelling older persons: A systematic review. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 60 (8), 1487–1492 (2012).

Chen, S. et al. Physical frailty and risk of needing Long-Term care in Community-Dwelling older adults: A 6-Year prospective study in Japan. J. Nutr. Health Aging. 23, 856–861 (2019).

Clegg, A., Young, J., Iliffe, S., Rikkert, M. O. & Rockwood, K. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet 381 (9868), 752–762 (2013).

Kojima, G. Frailty as a predictor of future falls among Community-Dwelling older people: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 16, 1027–1033 (2015).

Zhu, A., Yan, L., Wu, C. & Ji, J. S. Residential greenness and frailty among older adults: A longitudinal cohort in China. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 21 (6), 759–65e2 (2020).

Lorenzo-López, L. et al. Nutritional determinants of frailty in older adults: A systematic review. BMC Geriatr. 17 (1), 108 (2017).

Rockwood, K., Hogan, D. B. & MacKnight, C. Conceptualisation and measurement of frailty in elderly people. Drugs Aging. 17 (4), 295–302 (2000).

Rockwood, K. et al. A brief clinical instrument to classify frailty in elderly people. Lancet 353 (9148), 205–206 (1999).

van Abellan, G. et al. The I.A.N.A task force on frailty assessment of older people in clinical practice. J. Nutr. Health Aging. 12 (1), 29–37 (2008).

Dent, E., Kowal, P. & Hoogendijk, E. O. Frailty measurement in research and clinical practice: A review. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 31, 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2016.03.007 (2016).

Dent, E., Kowal, P. & Hoogendijk, E. O. Frailty measurement in research and clinical practice: a review. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 31, 3–10 (2016).

Canevelli, M., Cesari, M. & van Kan, G. A. Frailty and cognitive decline: how do they relate. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care. 18 (1), 43–50 (2015).

Fitten, L. J. Thinking about cognitive frailty. J. Prev. Alzheimers Dis. 2 (1), 7–10 (2015).

Solfrizzi, V. et al. Reversible cognitive Frailty, Dementia, and All-Cause mortality. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 18 (1), 89e1–89e8 (2017).

Feng, L. et al. Physical frailty, cognitive impairment, and the risk of neurocognitive disorder in the Singapore longitudinal ageing studies. J. Gerontol. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 72 (3), 369–375 (2017).

Kelaiditi, E. et al. Cognitive frailty: rational and definition from an (I.A.N.A./I.A.G.G.) international consensus group. J. Nutr. Health Aging. 17 (9), 726–734 (2013).

Liu, Z., Han, L., Gahbauer, E. A., Allore, H. G. & Gill, T. M. Cognitive frailty and adverse health outcomes among older adults: evidence from the China health and retirement longitudinal study. Aging (Albany NY). 13 (18), 21988–22003 (2021).

Zhang, Y. et al. Associations between activity participation and frailty among older adults: evidence from the China health and retirement longitudinal study. Front. Public. Health. 12, 1298457 (2024).

Panza, F. et al. Cognitive frailty: a systematic review of epidemiological and Neurobiological evidence of an age-related clinical condition. Rejuvenation Res. 18 (5), 389–412 (2015).

Man, W., Wang, S. & Yang, H. Exploring the spatial-temporal distribution and evolution of population aging and social-economic indicators in China. BMC Public. Health. 21 (1), 966 (2021).

Zeng, Y. Towards deeper research and better policy for healthy aging: using the unique data of Chinese longitudinal healthy longevity survey. China Econ. J. 5 (2–3), 131–149 (2012).

Yi, Z., Vaupel, J. W., Xu, Z., Zhang, C. & Li, Y. The Healthy Longevity Survey and the Active Life Expectancy of the Oldest Old in China. Population: An English Selection. 13(1):95–116. (2001).

Hoover, M., Rotermann, M., Sanmartin, C. & Bernier, J. Validation of an index to estimate the prevalence of frailty among community-dwelling seniors. Health Rep. 24, 10–17 (2013).

Luo, Y., Pan, X. & Zhang, Z. Productive activities and cognitive decline among older adults in china: evidence from the China health and retirement longitudinal study. Soc. Sci. Med. 229, 96–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.09.052 (2019).

Ma, C., Li, M. & Wu, C. Cognitive function trajectories and factors among Chinese older adults with subjective memory decline: CHARLS longitudinal study results (2011–2018). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 19, 16707. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416707 (2022).

Ainsworth, B. E. et al. 2011 compendium of physical activities: A second update of codes and MET values. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 43 (8), 1575–1581. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e31821ece12 (2011).

World Health Organization. Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health (World Health Organization, 2010).

Harrell, F. E. Regression Modeling Strategies: with Applications To Linear Models, Logistic Regression, and Survival Analysis (Springer, 2015).

Hayes, A. F. Introduction To Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach (Guilford Press, 2018).

Tolley, A. P. L., Ramsey, K. A., Rojer, A. G. M., Reijnierse, E. M. & Maier, A. B. Objectively measured physical activity is associated with frailty in community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 137, 218–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.04.009 (2021).

Lee, Y. S. et al. Association between objective physical activity and frailty transition in community-dwelling prefrail Japanese older adults. J. Nutr. Health Aging. 29 (4), 100519 (2025).

Yuki, A. et al. Daily physical activity predicts frailty development among community-dwelling older Japanese adults. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 20 (8), 1032–1036. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2019.01.001 (2019).

Trevisan, C. et al. Factors influencing transitions between frailty States in elderly adults: the progetto Veneto anziani longitudinal study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 65 (1), 179–184. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14515 (2017).

Vella Azzopardi, R. et al. Gerontopole Brussels study group. Increasing use of cognitive measures in the operational definition of frailty. Ageing Res. Rev. 43, 10–16 (2018).

Buchman, A. S. et al. Frailty is associated with incident alzheimer’s disease and cognitive decline in the elderly. Psychosom. Med. 69 (5), 483–489. https://doi.org/10.1097/psy.0b013e318068de1d (2007).

Boyle, P. A. et al. Physical frailty is associated with incident mild cognitive impairment in Community-Based older persons. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 58 (2), 248–255. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02671.x (2010).

Pahor, M. et al. Effect of structured physical activity on prevention of major mobility disability in older adults: the LIFE study randomized clinical trial. JAMA 311 (23), 2387–2396 (2014).

Gates, N. et al. The effect of exercise training on cognitive function in older adults with mild cognitive impairment: A Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 21(11), 930–940 (2013).

Bishop, N. A., Lu, T. & Yankner, B. A. Neural mechanisms of ageing and cognitive decline. Nature 464 (7288), 529–535. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature08983 (2010).

Bolt, T. B. et al. Widespread neural and autonomic system synchrony across the brain-body axis. BioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.01.19.524818 (2023).

Ma, L., Wang, H. B. & Hashimoto, K. The vagus nerve: an old but new player in brain–body communication. Brain Behav. Immun. 124, 28–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2024.11.023 (2025).

Jin, H. et al. A body–brain circuit that regulates body inflammatory responses. Nature 630, 695–703. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07469-y (2024).

Luo, Y., Pan, X. & Zhang, Z. Productive activities and cognitive decline among older adults in china: evidence from CHARLS. Soc. Sci. Med. 229, 96–105 (2019).

Marengoni, A. et al. Sex-specific patterns in the association between Multimorbidity and physical function decline in older adults. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 30 (7), 643–651 (2018).

Zhang, Z., Gu, D. & Hayward, M. D. Early life influences on cognitive impairment among older Chinese adults: urban-rural differences. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 65B (1), S13–S29 (2010).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the CHARLS research team for providing access to the data and acknowledge all participants of the survey. We are also grateful for the support of our colleagues and institutions involved in this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

1 J.T. conceived and designed the study. J.T. organized the database, performed the statistical analysis and wrote the manuscript. J.T. and H.W. confirmed the accuracy of the written language. J.T. and H.W. revised the manuscript. All authors edited, revised, and certified the final version of this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The CHARLS study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Peking University (IRB00001052-11015). All participants provided written informed consent prior to the survey. This secondary analysis was based on publicly available, de-identified data and did not involve any additional ethical risks.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tang, J., Wang, H. The mediating role of cognitive function in the association between physical activity and frailty risk. Sci Rep 16, 4764 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-35088-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-35088-2