Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most prevalent form of dementia, yet its early detection remains challenging due to the invasiveness, cost, and limited accessibility of current diagnostics. Increasing evidence suggests that retinal changes mirror cerebral pathology in AD, making the eye a promising site for non-invasive biomarker discovery. Here, we present a technique employing a custom-built tri-spectral retinal imaging module, designed to be integrated with existing fundus imaging systems, that captures retinal reflectance across three optimized spectral bands to quantify spectral alterations linked to AD. We validate the system in a case-control study of 38 mild AD patients and 28 age-matched controls, revealing spatially resolved differences in a fundus map derived from the blue-to-green ratiometric channel (p < 0.001). Our analysis identifies specifically the fovea-to-optic disc region as the most discriminative for AD, with an AUC of 0.74. Building on this, we developed a biologically informed machine-learning classification model incorporating spectral, clinical, and demographic data. On an independent validation test, the model achieved an AUC of 0.91, matching or slightly outperforming the most advanced spectral retinal measurements, yet using a simpler, more stable, and cost-effective setup that further facilitates clinical translation. The demonstrated technology, thanks to its non-invasiveness and its integrability with both existing medical technologies and advanced quantitative statistical methods, holds the potential to drive a significant leap forward in the early detection of AD, opening a window for timely intervention and thus profoundly impacting patient care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common cause of dementia, with a rapidly increasing number of cases primarily due to population ageing and growth. There are currently an estimated 50 million cases globally, projected to reach 150 million by 20501. AD is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder in the preclinical stage characterised by increasing misfolded protein fibril accumulation in the central nervous system (CNS)2. Over 20 years before clinical symptoms arise, misfolded amyloid β-protein (Aβ) assemblies begin to accumulate and propagate in distinctive brain areas, followed by the hyperphosphorylation of tau protein, creating paired helical filaments and neurofibrillary tangles3,4. Gradually, the pathological changes lead to a cascade of physiopathological events that ultimately cause cellular dysfunction, neuronal loss and synaptic alterations5. Currently, only limited symptomatic treatments are available worldwide with limited clinical efficacy, globally posing a significant socio-economic burden. Recently, some disease-modifying treatments (DMTs) have been approved for marketing, but not still available in Europe6,7,8. However, the effectiveness of DMTs (especially when compared to the potential side effects) is still a matter of debate, especially because when AD diagnosis is confirmed, the physiopatholoigcal cascade of events is already quite advanced and presumably Aβ clearance may have done little to ameliorate cognitive decline when irreversible vascular damage, gliosis, and neurotoxicity have already impacted the brain9.

The current approved methods for AD diagnosis are the detection of Aβ excess or tauopathy in the brain by positron emission tomography (PET) with specific radio-ligands or their measurement in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) obtained by lumbar puncture10,11,12. The drawbacks of these methods are high operational costs, method invasiveness and low accessibility. Hence, they are not suitable for large-scale population screening13. Thus, in most cases, diagnosis of AD relies on clinical symptom assessments, which are only applicable once symptoms are evident and pathological changes are already widespread. Therefore, although there is an extended preclinical phase providing a long-time window for early and efficient intervention, AD is not diagnosed in this presymptomatic stage. The late diagnosis decreases symptomatic treatment effectiveness and makes pharmaceutical treatment development challenging. Therefore, to cope with AD global burden, there is an urgent need for the development of non-invasive and affordable screening methods for early AD diagnosis.

Recently, the use of blood-based biomarkers (BBM), especially ptau 181 and 21714,15, is emerging as a promising tool for AD biological detection16. However, several challenges hinder their full integration into clinical practice as their levels can be influenced by various factors such as age, ethnicity, genotype, sex, and comorbidities17. As a result, despite significant advancements, BBMs remain an evolving tool that requires further validation and refinement before they can be fully implemented as a primary method for early AD diagnosis18.

Another direction focuses on examining AD hallmarks contained in the human retina. Being an extension of the CNS retina mirrors AD pathological changes in the brain. Clinical and post-mortem studies confirm that Αβ, neurofibrillary tangles are presented in the retina accompanied by other AD hallmarks, such as neuronal degeneration, retinal thinning, vascular abnormalities, and gliosis19,20,21. Since the retina is the only extension of CNS that can be visualised noninvasively in vivo, retina imaging represents a unique opportunity for non-invasive early AD detection and monitoring22,23,24,25,26. The first in vivo imaging of the retina for diagnosing AD was first achieved using transgenic mouse models where amyloid plaques were labelled using curcumin27,28. The proof of concept study on AD human cohort demonstrates the potential of the technique for non-invasive detection of Αβ plaques in the human retina29. Despite these promising findings, curcumin staining faces significant challenges, such as inconsistencies in fluorescence quantification across studies and interference with retinal autofluorescence and cataract-altered lens absorption30,31,32.

Further studies have taken an even less invasive direction when the classification between AD and Heathy Subject (HS) retina was achieved by analysing reflectance images of the retina without any fluorescent staining. It has been shown that the subtle biochemical and structural changes in tissues caused by the progression of AD have specific wavelength-dependent light scattering effects, referred to as the “spectral signature”33,34. This spectral signature was visualised by hyperspectral imaging (HSI), capturing the reflected light across a wide range of wavelengths in each pixel of the image24,35,36. A study on an AD animal model comparing retinal HSI in double transgenic mice (carrying APP and PS1 mutations) and wild-type (WT) mice demonstrated that the spectral signatures in both the brain and retina could differentiate AD mice from WT controls, even at early asymptomatic stages34. Further exploration of HSI’s potential for early AD detection was conducted in vivo using hyperspectral endoscopy in double transgenic AD mice36. The spectral signature of the human retina, measured in vivo, was correlated with cognitive impairment scores from the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), revealing increased retinal optical density with advancing disease33. A similar study on AD patients, diagnosed via neuropsychological tests and PET imaging, showed that AD patients could be distinguished from controls through advanced processing of HSI retinal images24.

Another promising direction in AD screening is the application of artificial intelligence (AI), particularly deep learning, to classical retinal fundus photography. For instance, a deep learning algorithm was developed using 12,132 fundus images across multiple countries, achieving a high accuracy (83.6%) and a robust Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC-ROC) score of 0.9337. Notably, the model was also resistant to interference from common eye diseases like macular degeneration and diabetes. Additionally, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) were applied to multi-modal imaging inputs (e.g., ganglion cell layer thickness maps, optical coherence tomography angiography scans), achieving a sensitivity of 79% and specificity of 83% for AD prediction38. Another study developed a modular deep learning algorithm from UK Biobank data, achieving 82.44% classification accuracy for AD detection using retinal vessel segmentation39. However, the complexity of deep learning models poses interpretability challenges, especially since many AD-related retinal features are not visually apparent to human observers. This “black-box” nature of deep learning hinders clinical acceptance25.

In this study, we introduce a novel, custom-engineered tri-spectral retinal imaging module designed to enhance the analytical capabilities of commercial fundus cameras for in vivo retinal imaging. Our module captures retinal reflectance across three optimized spectral regions—blue (< 520 nm), green (520–580 nm), and red (> 600 nm)—to detect spectral signatures associated with AD-related pathological changes in the retina. By targeting these spectral bands, our approach enables the non-invasive detection of subtle biochemical and structural alterations linked to AD progression. The primary objective of this study was to evaluate whether tri-spectral retinal imaging module can discriminate between biomarker-confirmed AD patients and healthy controls. A secondary objective was to assess the diagnostic accuracy of a machine-learning classifier combining spectral, demographic, and clinical features. We validate the methodology in a clinical case-control study, demonstrating its ability to distinguish AD patients from age-matched healthy controls. Using the acquired tri-spectral retinal data, we develop a biologically informed machine learning classifier, further enhancing diagnostic accuracy. Notably, the seamless integration of our compact and cost-effective tri-spectral retinal imaging module with existing commercial fundus cameras highlights its potential for widespread clinical adoption, offering a scalable, accessible, and non-invasive tool for early AD detection and monitoring in routine ophthalmic practice.

Results

Development of a Tri-spectral imaging method for fundus image acquisition

In this study, we developed a tri-spectral retinal imaging module designed for integration with a commercially available fundus imaging system (Fig. 1). The module, consisting of separate cameras, enables the simultaneous acquisition of three retinal images in distinct spectral regions, capturing high-sensitivity and resolution data with a single light flash (Fig. 1a). Fine spectral tuning in the selected regions was achieved through the optimised selection of dichroic mirrors and spectral filters, targeting wavelengths of \(\:{\lambda\:}_{1}<520\) (blue), \(\:{\:\lambda\:}_{2}\in\:\left[520,\:580\right]\) (green) and \(\:{\:\lambda\:}_{3}>600\) (red) (Fig. 1b). Compared to RGB camera, tri-spectral retinal imaging module brings crucial improvements: (i) reducing spectral overlap between channels, (ii) improving signal to noise ratio (SNR), and (iii) enhancing sensitivity (for more detailed information see Supplementary - Quantitative justification for the hardware choice).

After acquisition, spatial misalignment among cameras is corrected for all images (Fig. 1c), and veins are removed (Fig. 1 d), as detailed in the Materials and Methods section.

A sketch visualising the instrumental set-up and the data pre-processing. a The light reflected from the retina of the examined eye enters the tri-spectral retinal imaging module, where the retinal reflection image is separated into three spectral regions, shown at b, with the use of dichroic mirrors and long-pass filters. Finally, each of these three images enters into one of three cameras. After the acquisition, the obtained images are processed: c the camera’s spatial misalignment is corrected with an alignment matrix universal for all images taken by the set-up, d the veins are subtracted from an image, and e all images are transformed so that each image has the same pixel location for major anatomical parts (the centre of the optical disc and the centre of the fovea).

The proposed modular approach helps simplify hyperspectral imaging, reducing costs while facilitating integration with standard ophthalmoscopic examinations. At the same time, it enhances sensitivity at shorter wavelengths, which are particularly relevant for detecting early pathological changes associated with AD33.

Previous studies have shown that different regions of the retina exhibit distinct sensitivities to AD-related pathological changes24. Therefore, images were further aligned to ensure a one-to-one correspondence between pixel locations and specific anatomical regions of the eye, maintaining consistency across all recruited subjects. As described in Material and Methods, this alignment procedure relies on the identification of two easily detectable anatomical points – the center of the retina and the center of the fovea. Using these reference points, a transformation matrix is computed for each image, incorporating translation, rotation, and scaling to ensure consistent pixel alignment across all images (Fig. 1 d).

The effectiveness of the proposed technique in diagnosing AD was tested in a case-control clinical study, where we recruited 28 controls and 38 patients diagnosed with AD using CSF/PET biomarker evidence. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are presented in the Materials and Methods section, along with baseline demographic, clinical, and biochemical parameters (Table S1).

As the typical optical response of the proposed module for healthy (Fig. S1a-c) and pathological subjects (Fig. 2d-f), we obtain the three different channels, namely red, green, and blue. In Fig. 2, the images shown are the result of averaging all images acquired from controls (Fig. 2a) in the three different channels, as well as from pathological subjects (Fig. 2b). This operation is made possible by the previously discussed image alignment, which ensures correspondence between pixel location and anatomical structures.

A qualitative analysis of the average spectral response across the three channels does not reveal evident morphological differences between the two groups, highlighting the need to develop more powerful quantitative algorithms for patient classification. As previously stated, the spectral signature of the retina associated with AD pathological changes is more pronounced at shorter wavelengths33. To emphasize this effect, the average ratio between the blue and green channels (B/G ratio) (Fig. 2c, d) was computed. Comparing the ratiometric images of AD and HS, there is a clearly visible increase in blue channel intensity with respect to the green channel. The most evident modifications appear to be located in the extended macular part of the retina– a key finding that will be further examined in the next section.

Comparison of the optical response captured by the proposed tri-spectral retinal imaging modulefor healthy and pathological subjects. Typical optical response of the proposed tri-spectral retinal imaging modulefor healthy a and pathological b subjects. The images correspond to acquisitions in the red, green, and blue spectral channels. Panels c and d show the average ratiometric images calculated by dividing the blue channel by the green channel for c average heathy subjects and d average pathological subjects.

Ratiometric analysis of fundus imaging reveals nasal region as a promising biomarker for AD in a Case-Control experiment

The described technique was applied to compare the spectral response of a group of AD patients (n = 38) and control subjects (n = 28), aiming to identify potential optical biomarkers for the disease. To achieve this, the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC-ROC) was calculated using B/G ratios measured in all subjects from both groups. AUC-ROC is a widely used statistical measure to assess the performance of diagnostic biomarkers, with values around 0.5 indicating random classification, while significantly higher (or lower) values reflect improved diagnostic performance. In this study, a logistic regression model adjusted for subjects’ age was applied to generate the corresponding ROC curve, as detailed in the materials and methods.

Figure 3a shows the AUC spatial distribution across different regions of the examined fundus. Specifically, the value at each location was calculated by analysing the B/G ratios measured in the corresponding regions of all patients. This was made possible through the image alignment procedure described in Fig. 1e, ensuring consistency between pixel positions across different images and anatomical areas of the eye in various patients. Since the manual identification of anatomical landmarks for alignment introduces operator-based variability, we quantified its variability through repeated assignments of the fovea and optic disc resulting in standard deviations of 20.03 and 10.27 pixels, respectively, as outlined in the Materials and Methods.

To ensure the reliability of the spatial distribution of AUC-ROC values while accounting for the aforementioned error, the aligned retinal spectral images were divided into sub-quadrants of varying sizes: 150 × 150 pixels² (upper level), 50 × 50 pixels² (middle level), and 10 × 10 pixels² (lower level), with the smallest size approximately matching the alignment error. The average intensity within each sub-quadrant was calculated prior to AUC-ROC evaluation to enhance the signal-to-noise ratio and reduce the influence of localized anatomical inconsistencies. Notably, the three maps at different resolutions exhibit similar spatial patterns, consistently highlighting the nasal part of the retina, the bright red color between the fovea and optical disk, followed by the temporal part of the retina, as the most promising anatomical areas for the patient classification. This finding identifies the nasal and temporal regions of the retina as potential candidates as optical diagnostic biomarkers.

The choice of sub-quadrant size for subsequent analyses was further experimentally investigated in Figure S2. This figure shows the maximum AUC-ROC value in the nasal region at varying pixel side lengths, ranging from 10 to 500 pixels. The data are presented in terms of AUC ± SEM. For all sub-quadrant sizes, the maximum AUC-ROC shows statistically significant values between 72% and > 77%, further confirming the diagnostic potential of the investigated signal in this region. Specifically, the highest AUC-ROC is observed at the smallest sub-quadrant size of 10 pixels, followed by a slight decrease to a constant value of approximately 0.73 for sub-quadrant sizes between 50 and 150 pixels. A further small decrease is observed for larger sub-quadrant sizes.

To ensure the reliability and stability of the signal in the following analyses, we discarded the finest sub-quadrant size, despite its potentially higher AUC-ROC value, as it could be affected by localization errors of the same order as the pixel size. Instead, we selected a sub-quadrant size of 150 pixels, which provides robustness in localizing the region while maintaining a sufficiently high and significant AUC-ROC value. In the 10-pixel AUC map, the best-performing nasal sub-quadrant reaches an AUC-ROC of 0.76, only slightly higher than the 0.74 obtained for the 150-pixel ROI, indicating that landmarking errors of 10–20 pixels have only a limited impact on classification performance. Figure 3b shows the ROC curve at the 150-pixel resolution computed in the nasal part with the highest discriminative power based on the previous analysis (AUC-ROC = 0.74, 95% Confidence Interval (CI): 0.61–0.86). To further assess the impact of landmark variability, we analysed the 3 × 3 neighbourhood of sub-quadrants surrounding the central 150-pixel nasal ROI, corresponding to plausible landmarking errors of of this magnitude. The mean AUC-ROC of the eight adjacent sub-quadrants remained around 0.71, further supporting the robustness of the chosen ROI definition. The present ROC-based analysis, in addition to demonstrating the diagnostic potential of the signal, helps identify the most informative region in terms of discriminative power. A box plot analysis of the identified region, comparing B/G ratios between AD patients and healthy subjects, is shown in Fig. 3c. This analysis reveals a significant increase in the B/G ratio intensity in pathological subjects compared to healthy ones (p < 0.001, left panel). Interestingly, similar results are observed for the B/R ratio, which also appears elevated in AD patients (p < 0.001) (Figure S3c), further emphasizing the potential relevance of detecting an increased blue scattered signal permitted by the instrument design described in Fig. 1.

AUC ROC maps and Significance of B/G variables. a 4 heat maps with various pixel numbers of sub-quadrants (10, 50, and 150), each sub-quadrant colour shows the value of AUC-ROC for B/G ratio. b ROC curve for maximal AUC-ROC for 150px sub-quadrants. c confidence interval for 150px sub-quadrants with the highest AUC-ROC with calculated p < 0.001.

XGBoost model for AD and healthy subject classification

In the previous paragraph, we identified statistically significant differences in the recorded optical response between AD patients and controls, particularly in the B/G and B/R ratios measured in the nasal region (p < 0.001, Fig. 3c and Figure S3c). Beyond statistical significance, this region demonstrated diagnostic potential, as indicated by an AUC-ROC of 0.74 (Fig. 3b), obtained using a conventional logistic model. However, the statistical models used in the previous section rely heavily on linear assumptions and may not fully capture the complex, nonlinear relationships in spectral intensities associated with AD pathology. To address this limitation and enhance classification performance, we applied eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), a machine-learning approach designed to model complex nonlinear patterns while reducing overfitting through regularization and pruning.

As shown in Figure S4, the optical response across different regions of the ocular fundus exhibits strong correlations. To mitigate potential issues related to multicollinearity, we implemented an XGBoost model using the region previously identified as having the highest diagnostic potential, discarding other potentially correlated regions. Additionally, we included channels B, G, and R separately instead of as ratios to exploit XGBoost’s ability to handle nonlinear relationships among variables. Additionally, we incorporated the sum of intensities measured in the blue, green, and red channels, as defined in Fig. 1b, along with demographic variables (age and gender) and clinical data available for both groups (previous eye interventions).

For the development of the model, a total of 138 eyes were analyzed, obtained from 79 patients. Compared to the analyses in Fig. 3, additional subjects were included to allow for model validation on an independent group. In cases where both eyes from the same patient were available and exhibited similar spectral characteristics, only the left eye was selected. The dataset was then split into training (85.5%) and test (14.5%) sets.

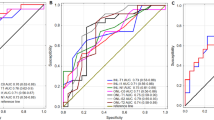

A leave-one-out cross-validation (LOOCV) was employed for training evaluation, yielding an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC-ROC) of 0.83, as shown in Fig. 4a (continuous black line), outperforming the previously discussed linear models. The confusion matrix for this classification is shown in Figure S5a, demonstrating an accuracy of 75.4%, a sensitivity of 82.4%, and a specificity of 66.0%. Despite the relatively low specificity, the high sensitivity and AUC-ROC suggest that the proposed technology is a promising tool for non-invasive patient screening.

In the independent test set, the model achieved an AUC-ROC of 0.91, as reported in Fig. 3a (continuous red line), confirming consistent generalization performance. The confusion matrix for the test set (Figure S5b) reports an accuracy of 85.0%, a sensitivity of 84.6%, and a specificity of 85.7%. The comparison between the two ROC curves, as well as the classification performance parameters, highlights the limited impact of overfitting, with test set metrics even slightly outperforming those of the training set. This discrepancy can be attributed to the limited number of recruited subjects, affecting the stability of performance estimates. The LOOCV AUC (0.83) and the test AUC (0.91) show overlapping confidence intervals (LOOCV 95% CI: [0.75, 0.91]; test: [0.78, 1.00]), indicating that the apparent improvement is compatible with sampling variability and noise in a small independent cohort rather than a true performance increase. Larger datasets will be required to reduce uncertainty and provide more precise estimates of discrimination performance.

To better understand the contribution of each feature to the model’s predictions, we employed SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) analysis. Machine learning models, particularly tree-based methods like XGBoost, can capture complex, nonlinear relationships between variables but often lack interpretability. SHAP provides a unified framework for feature importance by quantifying the impact of each variable on the model’s decision-making process.

Figure 4b presents the mean absolute SHAP values for each feature, ranking them according to their influence on classification. The most influential feature was, as expected, the sum of intensity in the blue spectral region (Blue_SUM), followed by Green_SUM and age. This ranking aligns with previous findings, where pathological changes in the retina associated with AD primarily affected shorter wavelengths. The sum of intensities from specific sub-quadrants (Green_SQ, Red_SUM, Blue_SQ, Red_SQ) also contributed significantly to the classification, though to a lesser extent.

Among the demographic and clinical variables, sex had a marginal impact, while previous eye interventions (PEI) exhibited the lowest SHAP values, indicating a negligible effect on the model’s predictions. This suggests that prior ocular procedures did not introduce significant confounding effects in our dataset, further reinforcing the robustness of our imaging-based approach.

XGBoost classification performance and SHAP-based feature importance. a Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for the XGBoost model trained with leave-one-out cross-validation (black line) and validated on an independent test set (red line). The model achieves AUC of 0.83 (95% CI: 0.75–0.91) for the training set and 0.91 (95% CI: 0.78–1.0). b Mean absolute SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) values ranking each predictor by its contribution to classification (for SHAP directionality and value distributions see Supplementary Figure S12).

Discussion

In this study, we introduced a novel tri-spectral retinal imaging module designed for straightforward integration with commercial fundus cameras, enabling the acquisition of retinal reflectance images across three optimized spectral bands (blue: <520 nm, green: 520–580 nm, and red: >600 nm, Fig. 1). To assess the technique’s diagnostic potential, we conducted a case-control clinical study comparing retinal spectral signatures between biomarker-confirmed AD patients and age-matched healthy individuals. By performing a retinal map, our imaging system enabled us to identify specific fundus regions—particularly the area between the optic disc and the fovea—that exhibit high diagnostic potential. Within these regions, we observed statistically significant differences in spectral response between AD patients and healthy individuals, particularly in the intensity of blue light. These differences were better highlighted by normalizing against the green channel (Blue-to-Green ratio in Fig. 3). Leveraging the diagnostic potential of the selected region, we developed an XGBoost classification model using raw spectral intensities and total reflectance in each channel. The model achieved a high AUC of 0.91, further validating the diagnostic capabilities of our tri-spectral retinal imaging module and confirming the presence of a detectable optical signature of the disease. Further analysis with explainable AI methods revealed that blue spectral intensity was the most influential feature.

The choice to directly target the retina for the development of our tri-spectral retinal imaging module stems from its role as a direct window into the central nervous system21. Retinal alterations have indeed been correlated with cerebral amyloid and tau deposition, as demonstrated in the pioneering studies of Vince and collaborators, who applied HSI to ex vivo postmortem human retinas and transgenic AD models34,36. Their work established that Aβ aggregates increase Rayleigh scattering, primarily affecting the blue spectrum. In a subsequent study on ex vivo human retinas, the spectral signature of Aβ aggregates was found to reduce blue transmission (480–530 nm), whereas pTau enhanced green transmission (520–580 nm)40. In comparison with these findings, the significant increase in reflectance intensity of the Blue/Green ratio observed in the high-sensitivity diagnostic region in Fig. 3c could be the result of an accumulation of aggregated Aβ and pTau forms.

More recently, Hadoux et al. provided a significant step forward in the clinical application of retinal HSI by developing a custom-built system covering a broad wavelength range from 420 nm to 900 nm, with 5 nm spectral resolution. Their study demonstrated that HSI can distinguish individuals with high and low brain Aβ burden, as stratified by PET imaging. Consistently with the patterns observed in Figs. 2 and 3, Hadoux et al. reported that the most pronounced spectral differences between AD patients and controls were found at shorter wavelengths35. Both our results and those from35, strongly suggest that retinal HSI can differentiate individuals based on cerebral Aβ burden. However, given the design of both studies, this conclusion cannot be made definitively, as the observed spectral changes may also reflect other retinal alterations associated with AD pathology. Almost simultaneously to35, Vince et al. confirmed in a second study involving 19 AD patients and 16 age-matched controls that retinal HSI can detect AD at a preclinical stage, further supporting its potential as a noninvasive screening tool33.

Notably, the previously discussed clinical study by Hadoux et al. employed DROP-D, a supervised machine learning approach, to reduce the dimensionality of their multispectral data and enhance group differences35,41. In contrast, we leveraged hardware-based spectral selection rather than data-driven dimensionality reduction, designing our system with three cameras, each targeting finely tuned specific spectral regions identified as diagnostically relevant in previously discussed papers35,36,40. This approach allowed us to optimize sensitivity in the blue range, which is typically acquired with lower efficiency in classical imaging systems42.

A key challenge in clinical research is that many emerging diagnostic methods struggle to transition from laboratory validation to routine medical use due to intrinsic translational barriers43. To actively overcome this limitation, we specifically designed our HSI module to be directly integrated within widely used clinical equipment for fundus examination, a non-invasive routine procedure commonly performed on large population groups44. The previously discussed design, based on three separate cameras capturing different regions of the visible spectrum rather than a conventional spectral measurement, further enhances its translational potential by enabling the acquisition of spectral information with a single light flash, ensuring both superior speed and ease of use compared to similar technologies.

A second key characteristic of our module is its non-invasiveness, which makes it a promising tool to complement established AD diagnostic methods such as structural and functional MRI, PET, and CSF biomarker analysis. While these techniques offer high accuracy, they come with significant drawbacks45. Specifically, CSF biomarker analysis requires invasive lumbar punctures, limiting its feasibility for routine use, while PET and MRI are expensive and not widely accessible. These limitations make them impractical for large-scale screening, particularly in the early stages of AD, when intervention is most effective46.

At variance with these methods, our approach is perfectly suited to stimulate the creation of novel AD screening protocols, not only due to its non-invasiveness but also thanks to its intrinsically label-free nature, which enhances its scalability and facilitates widespread clinical adoption.

An additional key advantage in this direction is the integration of machine learning-based predictive models, which provide the clinician with a direct diagnostic output rather than a spectral parameter requiring further interpretation by specialized personnel.

This characteristic aligns our study with advanced large-scale investigations that have combined conventional fundus photography and deep learning to detect AD-related changes37,38,39. However, the “black-box” nature of deep learning remains a major limitation for its clinical adoption, especially since AD-induced retinal changes are often subtle and not visually apparent25,47. In contrast, we show that replacing an RGB camera with our tri-spectral retinal imaging module enhances short-wavelength acquisition by reducing spectral overlap and improving sensitivity in the blue region of interest, resulting in significant AD vs. HS separation using linear statistics. These findings indicate that spectral design alone can provide an interpretable diagnostic signal without complex models, supporting clinical trust and facilitating clinical translation. Our approach aims to overcome this limitation by combining XGBoost-based classification with explainable AI techniques such as SHAP (Figs. 4, a and b). XGBoost is particularly well suited for this task due to its robustness in low-sample scenarios leveraging techniques such as subsampling, LASSO and Ridge regularization, and pruning to effectively reduce overfitting48,49,50,51,52. Additionally, unlike the linear classification methods used in Fig. 3, XGBoost efficiently captures the inherently nonlinear relationships between spectral intensity responses, providing a more accurate representation of complex spectral patterns. The integration of SHAP further enhances model interpretability by identifying the most relevant features in the classification process and ensuring that the selected spectral parameters align with a well-defined physical rationale53.

Specifically, in our case, SHAP confirms the relevance of short-wavelength scattering contributions to reflectance measurements, in agreement with previous in vitro and in vivo studies24,33,34,36,40,54. Moreover, it highlights the limited impact of prior eye surgeries on classification outcomes, demonstrating the robustness of our approach against this potential confounding factor. Notably, this same stability of retinal predictors in early AD diagnosis has been consistently observed in both HSI-based and conventional fundus photography studies, an intriguing finding that warrants further investigation. A possible explanation is that, in many cases, prior ocular interventions do not directly affect retinal morphology but rather involve the cornea, lens, or vitreous body. In this regard, a dedicated study on surgical procedures related to internal limiting membrane (ILM) peeling in macular hole and epiretinal membrane cases would be of particular interest, as the removal of this thin basal membrane layer could alter superficial scattering at shorter wavelengths55,56,57,58.

A relevant comparison that warrants consideration is between our approach and optical coherence tomography (OCT), as it represents the gold standard for high-resolution morphological assessment of the retina and has been the focus of extensive research aimed at identifying novel retinal biomarkers for the early diagnosis of AD. In this context, numerous cross-sectional and meta-analytic studies consistently report structural changes in the AD retina—most notably peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) and macular thinning—that often correlate with disease severity and can even precede clinical symptoms21,59,60,61,62,63. In addition, OCT-angiography (OCTA) studies suggest that AD may be associated with reduced vessel density and an enlarged foveal avascular zone21,64,65. However, these findings are not exclusive to AD, as RNFL thinning has also been documented in normal aging and other neurodegenerative or ocular conditions66,67,68,69, and vascular alterations can be influenced by a range of comorbidities65.

Compared to our method, OCT has the advantage of providing tomographic information of the retina across different layers. However, this capability relies on the use of near-infrared radiation, which ensures sufficient tissue penetration. On the other hand, the need to operate at longer wavelengths limits OCT’s ability to detect short-wavelength scattering phenomena potentially associated with amyloid-beta and other early biochemical alterations. In this respect, our method has the concrete potential to be integrated with this established technique, complementing the information obtained from retinal analysis and offering additional sensitivity to incipient retinal changes that may remain undetected using near-infrared imaging alone.

In summary, we demonstrate a tri-spectral retinal imaging modulecapable of detecting distinctive spectral signatures of AD in the retina, particularly in the blue-green range, which is sensitive to biochemical changes such as amyloid-beta aggregation. By integrating with commercial fundus cameras and capturing diagnostically relevant spectral bands in a single flash, our approach combines the rich spectral information of hyperspectral imaging with the simplicity and accessibility of conventional ophthalmic workflows. Additionally, its noninvasive and label-free nature enhances scalability, making it particularly well-suited for large-scale population screening and addressing a crucial unmet need in early-stage AD detection. Furthermore, the adoption of machine learning provides an additional push toward clinical translatability by delivering a direct diagnostic output, while the integration of explainable AI helps clinicians relate spectral findings to potential mechanisms underlying retinal alterations induced by the pathology. Future studies should focus on expanding validation in broader patient cohorts, integrating additional biomarkers, and optimizing workflow efficiency, for instance by incorporating automated approaches for disc and fovea localisation, to further reduce operator-dependent variability and enhance reproducibility in larger-scale studies.

Materials and methods

Study participants

This study was designed as a single-center, biomarker-confirmed case–control study and enrolled two cohorts: a healthy subject (HS) group (n = 28) and an AD group (n = 38), under a clinical trial registered on 24/02/2025 at ClinicalTrials.gov (ID: NCT06841848, https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06841848?term=NCT06841848&rank=1). The HS cohort comprised 15 females (54%) and 13 males (46%), with a mean age of 68 years (SD = 7), and 4 individuals (14%) had documented cataract-related interventions. The AD cohort consisted of 25 females (66%) and 13 males (34%), with a mean age of 70 years (SD = 6), and 11 individuals (29%) had cataract-related interventions. Diagnosis of AD was established either by amyloid positron emission tomography (PET) imaging (8 patients, 21%) or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) B42 analysis (30 patients, 79%). The AD cohort had a mean Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score of 19.50 (SD = 3.04). Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) scores indicated diverse disease severity in the AD group: 12 patients (43%) at CDR 0.5, 14 (50%) at CDR 1, and 2 (7.1%) at CDR 2, corresponding to very mild through moderate dementia. Inclusion criteria were age ≥ 55 years, biomarker confirmation of AD or absence of cognitive impairment (HS), and ability to undergo retinal imaging; exclusion criteria were major ophthalmological or neurological conditions other than cataract.

All participants provided written informed consent before enrollment, adhering to the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the institutional ethical committee at Fondazione Santa Lucia, Rome. No changes to the trial protocol or prespecified outcomes were made after trial commencement. As the study involved only non-invasive retinal fundus imaging, no harms or adverse events were expected or observed. Patients or members of the public were not involved in the design, conduct, or reporting of this study. To ensure compliance with data protection regulations, all patient data were anonymized prior to analysis. The cohort size was determined by feasibility of recruitment within the trial period, and was comparable to prior retinal hyperspectral pilot studies; no interim analyses or stopping rules were planned. De-identified participant data (including age, sex, ocular history, and spectral imaging values) and MATLAB/R analysis code are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Due to privacy and ethical restrictions, raw retinal images cannot be publicly shared but may be provided in anonymized form for academic collaborations.

The exploratory ratiometric analysis (Fig. 3) was conducted on the biomarker-confirmed case–control cohort comprising 38 AD patients and 28 healthy subjects. To avoid within-subject correlation, each subject contributed a single eye, yielding 66 eyes. For the XGBoost classification analysis (Fig. 4), additional subjects were included beyond those in Fig. 3, resulting in a total of 79 patients (42 AD, 37 HS). Both eyes were included, yielding 138 eyes (when both eyes from the same patient exhibited comparable spectral characteristics, only the left eye was retained). The dataset was split into training (85.5%) and test (14.5%) sets at the patient level, ensuring that both eyes from any given subject were assigned to the same set (for more information see table S3).Tri-spectral retinal imaging moduleIn this work, a custom tri-spectral retinal imaging modulewas integrated with the commercially available TOPCON TRC-NW6S Non-Mydriatic Retinal Camera, a digital ophthalmic device routinely used for diagnosing various pathologies of the retina and eyeball (e.g., glaucoma, diabetic retinopathy). By attaching the module in place of the external fixation camera, the functionality and standard operation of the fundus camera remain unchanged, thereby ensuring a practical and scalable solution for clinical applications.

The module is designed to capture retinal images simultaneously in three distinct spectral bands—\(\:{\lambda\:}_{1}<520\) (blue), \(\:{\:\lambda\:}_{2}\in\:\left[520,\:580\right]\)(green) and \(\:{\:\lambda\:}_{3}>600\) (red)—chosen to align with key points in the reflectance spectrum that are potentially relevant to AD. During imaging, light reflected from the retina passes through the internal optics of the fundus camera and emerges above the camera’s final relay lens (magnification of 1.09). The module then diverts this light into three optical paths using dichroic mirrors and long-pass filters, each path directing one spectral range to a dedicated, synchronized camera (Basler ace L acA4096-30 μm, pixel size 3.45 μm × 3.45 μm). The simultaneous acquisition of the three images is achieved by a single light flash, with hardware triggering controlled by custom software.

Because of slight spatial misalignments among the three cameras we perform inter-camera co-registration using a calibration marker target. A custom MATLAB script extracts the spatial correspondences and computes a fixed, instrument-specific alignment matrix (translation and rotation), estimated once from the calibration target and then applied to all retinal acquisitions. This software-based alignment ensures that each pixel location across the three spectral images corresponds to the same retinal position. Ultimately, by merging the three aligned images into a single data matrix, each pixel in the resultant image contains intensity information from all three spectral bands. This setup allows for the extraction of spectral signatures that may be linked to AD pathology, without compromising the TOPCON camera’s original diagnostic capabilities.

Image acquisition and image Pre-Processing

Imaging was conducted using the TOPCON TRC-NW6S camera fitted with developed custom tri-spectral retinal imaging module described above. Each eye was imaged with a single flash, capturing three spectral images (blue, green, and red) simultaneously. Image preprocessing and quantitative analyses were performed by investigators blinded to clinical diagnosis.

Captured images underwent pre-processing to ensure consistency and accuracy in the analysis. Two distinct alignment steps were applied. First, inter-camera co-registration within each capture was achieved by applying the fixed alignment matrix derived from the calibration marker target (as described above), ensuring pixel-wise correspondence across the three spectral channels. Second, inter-subject alignment (cross-patient) was performed to map same anatomical parts in the same pixel coordinates. The transformation matrixwas derived from two anatomical landmarks: the optical disk and the center of the fovea. These reference points were identified manually for each retinal image, and transformation matrices incorporating translation, rotation, and scaling were applied to align all images to a common coordinate system.

To assess the repeatability of the manual landmark identification used for inter-subject alignment,, nine distinct retinal images were each annotated ten times for both the fovea and the optic disc. For each image, we first computed the mean (x, y) coordinate of all ten repeated clicks. Next, we determined the radial distance of each click from its corresponding mean coordinate, reflecting how far each individual annotation deviated from the average position. The standard deviation (SD) of these radial distances was taken as the within-image variability for each landmark. Finally, we averaged these within-image SD values across all nine images, yielding a mean SD of 20.03 pixels for the fovea and 10.27 pixels for the optic disc.

Vein removal was performed to isolate the reflectance spectrum associated with retinal tissue. An automated algorithm based on morphological detection was used to identify and subtract veins from the images. After applying a Frangi vesselness filter70 to highlight elongated vascular structures, images were binarized and regions with area smaller than a threshold were excluded as noise.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using R (v4.4.0) and Matlab (R2023b, MathWorks, Natick, MA). Data visualization was conducted using OriginPro 2022 (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA). The normality of continuous variables was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test and visually inspected with QQ plots (data not shown). Some variables deviated from normality; therefore, results are presented as median and interquartile range (IQR), and comparisons between AD and HS were conducted using the Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical variables, such as sex and history of ocular interventions, were compared using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Tabular comparisons were generated using the gtsummary package in R.

To evaluate the diagnostic performance of the B/G ratio as a potential biomarker for AD, ROC curve analysis was performed, and the area under the ROC curve (AUC-ROC) was computed along with its 95% confidence interval using DeLong’s method. The AUC-ROC was calculated pixel-wise after aligning all images to a common reference frame, ensuring that corresponding pixels across different subjects mapped to the same anatomical region of the eye. This alignment process minimized inter-individual variability and allowed for direct comparisons across all subjects.

To identify the retinal regions with the highest diagnostic potential, a spatially resolved analysis of the AUC-ROC values was performed. Specifically, using Matlab, colormaps were generated to visualize the distribution of AUC-ROC values across different anatomical locations of the eye fundus. The images were divided into sub-quadrants of different pixel sizes, and the AUC-ROC was computed for each region based on the B/G ratios. This approach allowed us to determine the areas with the most discriminative power for AD classification while accounting for potential anatomical variability across subjects. To assess the impact of landmarking variability on the diagnostic ROI, AUC-ROC values obtained at 10-pixel and 150-pixel resolutions were compared, and AUC-ROC was additionally computed within the 3 × 3 neighbourhood of sub-quadrants surrounding the selected 150-pixel ROI.

For classification modelling, we applied XGBoost to distinguish between AD and HS subjects based on spectral data. The dataset was first split into a training set (85.5%) and an external validation set (14.5%), ensuring that performance was evaluated on independent patients. Model hyperparameters were selected via grid search, prioritizing model stability rather than performance maximization. Within the training set, LOOCV was employed to obtain an unbiased estimate of model performance during training. After this evaluation, the final model was trained on the full training set and then applied to the external validation cohort to assess its generalizability.

To ensure a balance between predictive power and generalizability, the model was configured with a logistic regression objective function (binary: logistic), an evaluation metric based on the area under the ROC curve (auc), a learning rate (eta) set to 0.1, and a maximum tree depth (max_depth) of 3. Subsampling techniques were employed, with 80% of the data used per tree (subsample = 0.8) and 80% of the features selected per split (colsample_bytree = 0.8). Regularization parameters included L2 regularization (lambda = 1) and L1 regularization (alpha = 0) to mitigate overfitting.

Feature importance was assessed using SHAP to quantify the contribution of each variable to the classification outcome. Results confirmed that the blue spectral region provided the highest predictive power.

Data availability

De-identified participant data (including age, sex, ocular history, and spectral imaging values) and MATLAB/R analysis code are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Due to privacy and ethical restrictions, raw retinal images cannot be publicly shared but may be provided in anonymized form for academic collaborations.

References

Nichols, E. et al. Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: an analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet Public. Heal. 7, e105–e125. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00249-8 (2022).

Grimaldi, A. et al. Inflammation, neurodegeneration and protein aggregation in the retina as ocular biomarkers for alzheimer’s disease in the 3xTg-AD mouse model. Cell. Death Dis. 9 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-018-0740-5 (2018).

Braak, H. & Braak, E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 82, 239–259 (1991).

Spires-Jones, T. L. & Hyman, B. T. The intersection of amyloid beta and Tau at synapses in alzheimer’s disease. Neuron 82, 756–771 (2014).

Francesco, D. L. & Koch, G. Synaptic impairment: the new battlefield of alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 17, 314–315. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.12189 (2021).

Yiannopoulou, K. G. & Papageorgiou, S. G. Current and future treatments in alzheimer disease: an update. J. Cent. Nerv. Syst. Dis. 12 https://doi.org/10.1177/1179573520907397 (2020).

Boxer, A. L. & Sperling, R. Accelerating alzheimer’s therapeutic development: the past and future of clinical trials. Cell 186, 4757–4772. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2023.09.023 (2023).

Cummings, J. et al. Anti-Amyloid monoclonal antibodies for the treatment of alzheimer’s disease. BioDrugs 38, 5–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40259-023-00633-2 (2024).

Haass, C. & Selkoe, D. If amyloid drives alzheimer disease, why have anti-amyloid therapies not yet slowed cognitive decline? PLoS Biol. 20, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3001694 (2022).

Marcus, C., Mena, E. & Subramaniam, R. M. Brain PET in the diagnosis of alzheimer’s disease. Clin. Nucl. Med. 39, e413. https://doi.org/10.1097/RLU.0000000000000547 (2014).

Hampel, H. et al. State-of-the-art of lumbar puncture and its place in the journey of patients with alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 18, 159–177 (2022).

Thientunyakit, T. et al. Relationships between amyloid levels, glucose metabolism, morphologic changes in the brain and clinical status of patients with alzheimer’s disease. Ann. Nucl. Med. 34, 337–348. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12149-020-01453-y (2020).

Weller, J. & Budson, A. Current Understanding of alzheimer’s disease diagnosis and treatment. F1000Research 7 https://doi.org/10.12688/F1000RESEARCH.14506.1 (2018).

Antonioni, A. et al. Blood phosphorylated Tau181 reliably differentiates amyloid-positive from amyloid-negative subjects in the alzheimer’s disease continuum: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Alzheimer’s Dement. Diagnosis Assess. Dis. Monit. 17, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/dad2.70068 (2025).

Antonioni, A. et al. Blood phosphorylated Tau217 distinguishes amyloid – positive from amyloid – negative subjects in the alzheimer ’ s disease continuum. A systematic review and meta – analysis. J. Neurol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-025-12996-3 (2025).

Teunissen, C. E. et al. Blood-based biomarkers for alzheimer’s disease: towards clinical implementation. Lancet Neurol. 21, 66–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(21)00361-6 (2022).

Hunter, T. R., Santos, L. E., Tovar-Moll, F. & De Felice, F. G. Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers and their current use in clinical research and practice. Mol. Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-024-02709-z (2024).

Antonioni, A., Raho, E. M. & Di Lorenzo, F. Is blood pTau a reliable indicator of the CSF status? A narrative review. Neurol. Sci. 45, 2471–2487. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-023-07258-x (2024).

Mirzaei, N. et al. Alzheimer’s retinopathy: seeing disease in the eyes. Front. Neurosci. 14 https://doi.org/10.3389/FNINS.2020.00921 (2020).

Grimaldi, A. et al. Neuroinflammatory Processes, A1 astrocyte activation and protein aggregation in the retina of alzheimer’s disease Patients, possible biomarkers for early diagnosis. Front. Neurosci. 13 https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2019.00925 (2019).

Gaire, B. P. et al. Alzheimer’s disease pathophysiology in the retina. Prog Retin Eye Res. 101, 101273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.preteyeres.2024.101273 (2024).

Guo, L. Alzheimer’s disease and retinal neurodegeneration. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 999, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.2174/1567209197155452050 (2009).

Gupta, V. B. et al. Retinal changes in alzheimer’s disease— integrated prospects of imaging, functional and molecular advances. Prog Retin Eye Res. 82, 100899 (2021).

Hadoux, X. et al. Non-invasive in vivo hyperspectral imaging of the retina for potential biomarker use in alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Commun. 10 https://doi.org/10.1038/S41467-019-12242-1 (2019).

Chan, V. T. T. et al. Value proposition of retinal imaging in alzheimer’s disease screening: A review of eight evolving trends. Prog Retin Eye Res. 103 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.preteyeres.2024.101290 (2024).

Koronyo, Y., Salumbides, B. C., Black, K. L. & Koronyo-Hamaoui, M. Alzheimer’s disease in the retina: imaging retinal Aβ plaques for early diagnosis and therapy assessment. Neurodegener Dis. 10, 285–293. https://doi.org/10.1159/000335154 (2012).

Koronyo-Hamaoui, M. et al. Identification of amyloid plaques in retinas from alzheimer’s patients and noninvasive in vivo optical imaging of retinal plaques in a mouse model. Neuroimage 54 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.06.020 (2011).

Garcia-Alloza, M. et al. Curcumin labels amyloid pathology in vivo, disrupts existing plaques, and partially restores distorted neurites in an alzheimer mouse model. J. Neurochem. 102, 1095–1104. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04613.x (2007).

Koronyo, Y. et al. Retinal amyloid pathology and proof-of-concept imaging trial in Alzheimer’s disease. JCI Insight. 2 https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI.INSIGHT.93621 (2017).

den Haan, J. et al. loid-proven AD cases compared to controls. Alzheimer’s Dement. Diagnosis Assess. Dis. Monit. 14, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1002/dad2.12347 (2022).

Kessel, L. et al. Age-related changes in the transmission properties of the human lens and their relevance to circadian entrainment. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 36, 308–312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrs.2009.08.035 (2010).

Tang, M. Y. et al. Imaging amyloid and Tau in the retina: current research and future directions. J. Neuro-Ophthalmology. 43, 168–179. https://doi.org/10.1097/WNO.0000000000001786 (2023).

More, S. S. et al. In Vivo Assessment of Retinal Biomarkers by Hyperspectral Imaging: Early Detection of Alzheimer’s Disease. (2019). https://doi.org/10.1021/acschemneuro.9b00331

More, S. S. & Vince, R. Hyperspectral imaging signatures detect amyloidopathy in alzheimers mouse retina well before onset of cognitive decline. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 6, 306–315. https://doi.org/10.1021/CN500242Z/SUPPL_FILE/CN500242Z_SI_001.PDF (2015).

Saeed, A., Hadoux, X. & van Wijngaarden, P. Hyperspectral retinal imaging biomarkers of ocular and systemic diseases. Eye 1–6. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-024-03135-9

More, S. S., Beach, J. M. & Vince, R. Early detection of amyloidopathy in alzheimer’s mice by hyperspectral endoscopy. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 57, 3231–3238. https://doi.org/10.1167/IOVS.15-17406 (2016).

Cheung, C. Y. et al. A deep learning model for detection of alzheimer’s disease based on retinal photographs: a retrospective, multicentre case-control study. Lancet Digit. Heal. 4, e806–e815. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2589-7500(22)00169-8 (2022).

Wisely, C. E. et al. Convolutional neural network to identify symptomatic alzheimer’s disease using multimodal retinal imaging. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 106, 388–395. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjophthalmol-2020-317659 (2022).

Tian, J. et al. Modular machine learning for alzheimer’s disease classification from retinal vasculature. Sci. Rep. 11, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-80312-2 (2021).

Du, X. et al. Label-Free Hyperspectral Imaging and Deep-Learning Prediction of Retinal Amyloid β-Protein and Phosphorylated Tau. 2022 IEEE Photonics Conf IPC 2022 - Proc 1–23. (2022). https://doi.org/10.1109/IPC53466.2022.9975636

Hadoux, X., Rutledge, D. N., Rabatel, G. & Roger, J. M. DROP-D: dimension reduction by orthogonal projection for discrimination. Chemom Intell. Lab. Syst. 146, 221–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemolab.2015.05.021 (2015).

Biswas, S. et al. Which color channel is better for diagnosing retinal diseases automatically in color. Fundus Photographs? Life. 12, 1–38. https://doi.org/10.3390/life12070973 (2022).

Enderle, D. & Noerholm, M. Are extracellular vesicles ready for the clinical laboratory? LaboratoriumsMedizin 46, 273–282 (2022).

Wong, T. Y. et al. Retinal microvascular abnormalities and their relationship with hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and mortality. Surv. Ophthalmol. 46, 59–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0039-6257(01)00234-X (2001).

Jack, C. R. et al. NIA-AA research framework: toward a biological definition of alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 14, 535–562. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2018.02.018 (2018).

Chételat, G. et al. Amyloid-PET and 18F-FDG-PET in the diagnostic investigation of alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. Lancet Neurol. 19, 951–962. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30314-8 (2020).

Chaitanuwong, P. et al. Potential ocular biomarkers for early detection of alzheimer’s disease and their roles in artificial intelligence studies. Neurol. Ther. 12, 1517–1532. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-023-00526-0 (2023).

Zelli, V. et al. Classification of tumor types using XGBoost machine learning model: a vector space transformation of genomic alterations. J. Transl Med. 21, 836 (2023).

Li, Q. et al. XGBoost-based and tumor-immune characterized gene signature for the prediction of metastatic status in breast cancer. J. Transl Med. 20, 177 (2022).

Yi, F. et al. XGBoost-SHAP-based interpretable diagnostic framework for alzheimer’s disease. BMC Med. Inf. Decis. Mak. 23, 137 (2023).

Chen, T. & Guestrin, C. Xgboost: A scalable tree boosting system. In: Proceedings of the 22nd acm sigkdd international conference on knowledge discovery and data mining. pp 785–794 (2016).

Carnazzo, V. et al. Exploratory study of extracellular matrix biomarkers for non-invasive liver fibrosis staging: A machine learning approach with XGBoost and explainable AI. Clin. Biochem. 135, 110861 (2025).

Lundberg, S. M. & Lee, S. I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017-Decem, 4766–4775 (2017).

Salajková, Z. et al. Optical signature of retinal Tau fibrillation. Sci. Rep. 15, 7792. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92565-w (2025).

Peynshaert, K. et al. Morphology and composition of the inner limiting membrane: Species-Specific variations and relevance toward drug delivery research. Curr. Eye Res. 44, 465–475. https://doi.org/10.1080/02713683.2019.1565890 (2019).

Vielmuth, F. et al. Biomechanical properties of the internal limiting membrane after intravitreal ocriplasmin treatment. Ophthalmologica 235, 233–240. https://doi.org/10.1159/000444508 (2016).

Mazzini, A. et al. A time-dependent study of nano-mechanical and ultrastructural properties of internal limiting membrane under ocriplasmin treatment. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 110:Art Number. 103853 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmbbm.2020.103853 (2020).

Ciasca, G. et al. Nanomechanical mapping helps explain differences in outcomes of eye microsurgery: A comparative study of macular pathologies. PLoS One. 14, e0220571. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0220571 (2019).

Coppola, G. et al. Optical coherence tomography in alzheimer’s disease: A meta-analysis. PLoS One. 10, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0134750 (2015).

den Haan, J., Verbraak, F. D., Visser, P. J. & Bouwman, F. H. Retinal thickness in alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Alzheimer’s Dement. Diagnosis Assess. Dis. Monit. 6, 162–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dadm.2016.12.014 (2017).

Chan, V. T. T. et al. Spectral-Domain OCT measurements in alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review and Meta-analysis. Ophthalmology 126, 497–510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2018.08.009 (2019).

Noah, A. M., Almghairbi, D. & Moppett, I. K. Optical coherence tomography in mild cognitive impairment – Systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 196, 106036. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clineuro.2020.106036 (2020).

Ashraf, G. et al. Retinal imaging biomarkers of alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies using brain amyloid beta status for case definition. Alzheimer’s Dement. Diagnosis Assess. Dis. Monit. 15, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1002/dad2.12421 (2023).

Jiang, H. et al. Retinal microvascular alterations as the biomarkers for alzheimer disease: are we there yet? J. Neuro-Ophthalmology. 41, 251–260. https://doi.org/10.1097/WNO.0000000000001140 (2021).

Shi, H. et al. Retinal vasculopathy in alzheimer’s disease. Front. Neurosci. 15, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2021.731614 (2021).

Balestrini, S. et al. Retinal nerve fibre layer thinning is associated with drug resistance in epilepsy. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 87, 396–401. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2015-310521 (2016).

Garcia-Martin, E. et al. Fibromyalgia is correlated with retinal nerve fiber layer thinning. PLoS One. 11 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0161574 (2016).

Lee, J. S. et al. Risk factors associated with progressive nerve fiber layer thinning in open-angle glaucoma with mean intraocular pressure below 15 mmhg. Sci. Rep. 9, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-56387-x (2019).

Woo, K. A. et al. Peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer thinning in patients with progressive supranuclear palsy. J. Neurol. 269, 3216–3225. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-021-10936-5 (2022).

Frangi, A. F., Niessen, W. J., Vincken, K. L. & Viergever, M. A. Multiscale Vessel Enhancement Filtering pp 130–137 (In: Springer, 1998).

Acknowledgements

The authors declare no competing financial or non-financial interests related to this work.

Funding

This work was supported by MUR PRIN 2022 (CUP: 2022CFP7RF, to M.L.). This research was also funded by the D-Tails-IIT Joint Lab, GR is supported by Project “National Center for Gene Therapy and Drugs based on RNA Technology” (CN00000041) financed by NextGenerationEU PNRR MUR— M4C2—Action 1.4-Call “Potenziamento strutture di ricerca e creazione di “campioni nazionali di R\&S” (CUP J33C22001130001)”. The research leading to these results was also supported by European Research Council through its Synergy grant program, project ASTRA (grant agreement No. 855923) and by European Innovation Council through its Pathfinder Open Program, project ivBM-4PAP (grant agreement No. 101098989). The authors acknowledge the support of the Italian Fund for Applied Sciences (FISA), project "ROAD- Retina Observation for Alzheimer Diagnostic", funded by the Italian Ministry of University and Research (MUR), under Call No. 1233 of 01/08/2023.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: ZS, ML, VR, GR Methodology: ZS, MLInvestigation: ZS, GC, MsGVisualization: ZSFunding acquisition: GR, VRProject administration: ZSSupervision: ZS, MLWriting – original draft: ZS, GCWriting – review & editing: FDL, RR, ML, MsG, MgG, JZ, YZ.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Salajková, Z., Ciasca, G., Di Lorenzo, F. et al. Non-invasive screening of alzheimer’s disease via label-free tri-spectral retinal imaging. Sci Rep 16, 5083 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-35383-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-35383-y