Abstract

Existing research on learned helplessness among nursing interns often overlooks group heterogeneity and fails to explore its relationships with the clinical learning environment and self-esteem. A convenience sample of 381 nursing interns completed standardized questionnaires assessing their demographic characteristics, learned helplessness, clinical learning environment, and self-esteem. Latent profile analysis revealed three distinct profiles of learned helplessness among the nursing interns: “Low Helplessness–Low Hopelessness” (n = 127, 33.3%), “High Helplessness–Low Hopelessness” (n = 172, 45.2%), and “High Helplessness–High Hopelessness” (n = 82, 21.5%). Multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that male gender, current pursuit of a bachelor’s degree, and working 4–6 night shifts during the past month were significantly associated with the “High Helplessness–Low Hopelessness” profile (OR = 5.113, 8.796, and 3.207, respectively). Holding an associate degree was significantly associated with the “High Helplessness–High Hopelessness” profile (OR = 7.221). Conversely, positive family relationships and fewer night shifts (0–3) during the past month were significantly associated with the "Low Helplessness–Low Hopelessness" profile (OR = 0.071 and 0.253, respectively). Additionally, a positive work atmosphere, individualized teaching, and high self-esteem were significantly associated with low levels of learned helplessness (OR = 0.850, 0.826, and 0.834, respectively; all p values < 0.05). Given the substantial proportion of interns in the “High Helplessness–Low Hopelessness” group, universities and hospitals should develop targeted educational strategies to effectively reduce learned helplessness among nursing interns.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As populations age across the world, the need for nursing care continues to grow substantially. However, research has indicated that during the period from January 2000 to February 2023, nurse turnover rates worldwide range from 8% to 36.6%, with average rates ranging from 16 to 19% in Asia and 15% in North America, thereby posing a substantial challenge to healthcare systems worldwide1. These attrition levels present health systems with a persistent staffing challenge. Because nursing students represent the profession’s next generation, the quality of their clinical internship experiences strongly shapes their career choices. Therefore, focusing closely on the emotional and psychological well-being of student nurses during clinical training is essential. This will help improve nurse retention, ease worldwide shortages of nursing staff, and support the long-term growth of the nursing profession.

In China, nursing students enrolled in diploma or bachelor’s programmes are required to complete a ten-month clinical internship following two to three years of theoretical education. During this period, they are designated “nursing interns”2. However, the demanding nature of the clinical environment, lack of recognition of acquired skills, and complex interpersonal dynamics during internships often result in negative psychological outcomes such as anxiety, depression, and learned helplessness3. Among these, learned helplessness in nursing interns requires particular attention.

Learned helplessness refers to a psychological state or behaviour characterized by feelings of powerlessness or abandonment of self-improvement that an individual develops when facing trauma, setbacks, and adversity4. Martin Seligman first introduced this concept while studying animal behaviour. In his experiments, Seligman5 saw that when animals encountered negative conditions that they could not escape on a regular basis, they stopped attempting to make any changes. In 1978, Abramson6 showed that this form of helplessness also commonly occurs in humans. If it continues, learned helplessness can severely harm a person’s well-being and may lead them to give up on themselves. People experiencing learned helplessness often feel emotionally numb, sad, or hopeless. Over time, they may develop a negative outlook on life and find less satisfaction in daily activities7. Therefore, it is important to reduce learned helplessness among nursing interns. This would support their mental health and help maintain a stable nursing workforce.

Most studies on learned helplessness among nursing interns have used methods that focus on variables. These studies have usually analyzed total scores from surveys to understand helplessness in a general manner. However, this approach often overlooks the fact that each intern’s experience can be different. Latent profile analysis (LPA)8 offers another approach; it focuses on people rather than variables. LPA helps find hidden groups within a larger population by examining patterns in different continuous measures. A key benefit of LPA is that it can find these subgroups without ignoring the unique differences between individuals. Our research uses LPA to explore the specific features of learned helplessness among nursing interns. We aim to identify critical moments where intervention could be most helpful. The results will provide useful information for providing support that meets different interns’ specific needs.

According to Bandura’s theory of "triadic reciprocal determinism"9, behavioural responses are shaped by the combined influence of external environmental factors and individual factors. We view learned helplessness as a behavioural response, and the clinical learning environment, as an external environment, is a crucial factor that influences this behavioural response. The clinical learning environment—comprising clinical staff, patients, educational opportunities, and learning resources—represents a significant environmental factor that affects nursing students’ learning outcomes and clinical experiences10. Positive clinical learning environments can reduce stress and anxiety among nursing interns while simultaneously enhancing their confidence and cognitive development11. Therefore, we hypothesize that a supportive clinical learning environment is associated with lower levels of learned helplessness among nursing interns, although this relationship awaits further empirical validation. However, current research on the association between different clinical learning environments and the manifestations of learned helplessness among nursing interns remains relatively scarce. Self-esteem, defined as an individual’s stable self-evaluation reflecting their perceptions of competence and self-worth12, is another personal factor that significantly influences learned helplessness. Higher levels of self-esteem are associated with greater adaptability to environmental stressors and reduced susceptibility to learned helplessness13. However, research on the correlation between different levels of self-esteem and distinct manifestation types of learned helplessness among nursing interns remains relatively scarce.

Based on the above theoretical framework, we hypothesize that individual characteristics (demographic data and self-esteem) and external environmental factors (clinical learning environment) predict learned helplessness among nursing students in clinical practice. Figure 1 represents the hypothetical framework of this study.The present study aims to address three key research questions: (1) What distinct profiles of learned helplessness exist among nursing interns? (2) What characteristics differentiate students across these learned helplessness profiles? (3) Are the clinical learning environment and self-esteem associated with different profiles of learned helplessness among nursing interns?

Methods

Design

This study utilized a cross-sectional design to identify the latent profiles and predictive factors of learned helplessness among nursing interns, thereby establishing a theoretical foundation for developing targeted educational intervention programs.

Setting and participants

Through convenience sampling, nursing students who were receiving clinical training at four Grade III-A hospitals in Henan Province were recruited between January and February 2025. The inclusion criteria were as follows: ① full-time nursing students; ② in the clinical internship phase; and ③ an internship duration of ≥ 6 months. The exclusion criteria were as follows: ① history of mental illness; ② leave of absence or premature termination of internship during the survey period; and ③ participation in similar studies. In accordance with the sample size estimation principle for logistic regression analysis, at least 10 cases per independent variable are required14. Given that this study involved 20 independent variables, and accounting for 10%-20% nonresponse rate, the estimated sample size ranged from 220 to 240 participants. In line with previous research on latent profile analysis, a sample size of at least 300 is recommended15.Ultimately, a total of 381 valid samples were included in this study.

Data collection

The questionnaire was distributed during the clinical practicum of nursing interns via the online platform "Questionnaire Star." Participants were selected from four comprehensive teaching hospitals that have long-term partnerships with our university and typically host a large number of interns. The internship programs and training models of these hospitals are regionally representative. After communication with the educational supervisors in the hospitals’ nursing departments, the teaching coordinators shared the questionnaire’s QR code in relevant WeChat groups for interns. Research team members uniformly explained the study purpose to participants without offering any incentives. The questionnaire was completed during designated teaching sessions or work breaks within the internship schedule. A total of 602 eligible nursing interns were invited, with 414 participating (a response rate of 68.77%). After applying the listwise deletion method for missing data and excluding 33 invalid responses (based on criteria such as a completion time under 120 s, patterned answers, or logical inconsistencies), 381 valid questionnaires were obtained, yielding an effective response rate of 92.02%.

Research instruments

Demographic questionnaire

The demographic questionnaire gathers demographic information such as gender, educational background, family residence, whether one is an only child, and the family’s average income.

Learned helplessness scale (LHS)

The Learned Helplessness Scale developed by Wu Xiaoyan16was used for measurement. This scale consists of two dimensions, namely, helplessness and hopelessness, and has a total of 18 items. All the items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1–5), with total scores ranging from 18 to 90. Higher scores indicate more severe learned helplessness. The overall scale demonstrated excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.930). Subscale reliability was strong for the helplessness factor (Cronbach’s α = 0.924) and acceptable for the hopelessness factor (Cronbach’s α = 0.742). The split-half reliability was 0.901, and the test–retest reliability after four weeks was 0.898. In the current study, the scale’s Cronbach α was 0.928.

Clinical learning environment scale

The Clinical Learning Environment Inventory for Nursing, developed by Zhu Wenxi17, was used to assess six dimensions: interpersonal relationships, work atmosphere, team culture, student engagement, innovation, and individualization (42 items total). Using a 5-point Likert scale (1–5), total scores range from 42 to 210, with higher scores indicating greater student satisfaction with the clinical learning environment. The scale demonstrated excellent reliability (subscale α = 0.871–0.927; total α = 0.931) and good content validity (expert rating = 0.90) . In our study, the total Cronbach α was 0.908.

Self-esteem scale

The Rosenberg18 Self-Esteem Scale, which comprises 10 items and whose Chinese version was revised by Tian Lumei19, was adopted in this study. Responses were recorded on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). Total scores range from 10 to 40, with higher scores indicating greater self-esteem. In this study, the internal consistency of the scale was acceptable (Cronbach’s α = 0.767).

Statistical analysis

We used Mplus 8.3 to perform latent profile analysis (LPA) and identify distinct subgroups among nursing interns on the basis of their learned helplessness scores. Model estimation was performed using robust maximum likelihood (MLR), with 1000 random starts and 250 final-stage optimizations to avoid local maxima.Our analysis tested models containing 1 to 5 profiles to determine the optimal number of subgroups. We evaluated model fit using several established indices: the Akaike information criterion (AIC), the Bayesian information criterion (BIC), and the adjusted Bayesian information criterion (aBIC). For all these indices, lower values indicate better model fit20. We also assessed classification accuracy through entropy, in which values range from 0 to 1, and values closer to 1 represent clearer classification. To compare different models, we used the Lo–Mendell–Rubin adjusted likelihood ratio test (LMRT) and the bootstrap likelihood ratio test (BLRT). A statistically significant p value (< 0.05) for these tests suggests that the k-class model provides a better fit than the (k-1)-class model does21. For other statistical analyses, we used SPSS 25.0. We presented categorical variables as frequencies and percentages and analysed them using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test where appropriate. For continuous data that did not follow a normal distribution, we report median values along with the 25th and 75th percentiles and used the Mann–Whitney U test for comparisons. To identify factors associated with subgroup membership, we performed multivariable logistic regression and considered p values less than 0.05 to indicate statistical significance.

Ethical approval

This study was approved and monitored by the institutional review board (approval number: 20230516001). All procedures were conducted in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. We obtained informed consent from all participants. To ensure confidentiality, all the collected data were anonymized and securely stored.

Results

Latent profile analysis of learned helplessness among nursing interns

This study conducted an exploratory latent profile analysis (LPA) using the 18 items of the Learned Helplessness Scale as manifest variables and the robust maximum likelihood (MLR) estimation method to determine the optimal model among 1- to 5-profile solutions.Model selection was based on the following comprehensive criteria: ①classification accuracy: The 2-class model showed high classification accuracy (entropy = 0.993), which was further improved in the 3-class model (entropy = 0.999). The Lo–Mendell–Rubin (LMR) test and bootstrap likelihood ratio test (BLRT) for both the 2-class model and the 3-class model were statistically significant (p < 0.001); however, when comprehensively considered, the 3-class model had a superior entropy value. Moreover, with three profiles, the average probability of belonging to each latent class ranges from 0.997 to 1, all exceeding 0.90, which indicates a high level of classification precision. ②Statistical tests:models with 4 and 5 classes yielded nonsignificant LMR test results (p > 0.05), indicating that these more complex models did not offer a statistically superior fit over the 3-class model. ③Information Criteria: the scree plot, a method analogous to that used in exploratory factor analysis, supported this conclusion. As shown in Fig. 2, the adjusted Bayesian information criterion (aBIC) values decreased and exhibited a clear elbow at the 3-class solution, providing additional justification for selecting three profiles22.④Model Interpretability and Clinical Significance: the 3-profile model yielded clearly interpretable, clinically distinct subgroups. Each profile contained a sufficient sample size and demonstrated adequate theoretical distinctiveness.⑤Robustness of the Model Solution: the robustness of the 3-profile solution was assessed using a bootstrap procedure. Based on 1,000 bootstrap samples, the 95% confidence intervals for all parameter estimates did not include zero, indicating statistically significant and stable estimates.Ultimately, the 3-class model was selected for the latent profile analysis of learned helplessness among nursing interns.The results of this model are presented in Table 1.

Note:AIC, Akaike information criterion; BIC, Bayesian information criterion; aBIC, adjusted Bayesian information criterion; LMR, Lo–Mendell–Rubin test; BLRT, bootstrapped likelihood ratio.

Learned helplessness among nursing interns

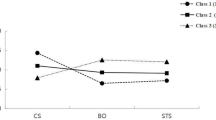

The mean score distributions of the three latent profiles of learned helplessness across the 18 items are presented in Fig. 3. The profiles were named on the basis of their score patterns across these items:

-

C1 (Low Helplessness–Low Hopelessness Group): Comprising 127 participants (33.3%), this group exhibited low scores on both the helplessness and hopelessness items.

-

C2 (High Helplessness–Low Hopelessness Group): With 172 participants (45.2%), this group displayed significantly higher scores for the helplessness items while maintaining low scores for the hopelessness items.

-

C3 (High Helplessness–High Hopelessness Group): Consisting of 82 participants (21.5%), this group had elevated scores for both the helplessness and hopelessness items.

Scores of learned helplessness among nursing interns with different latent profiles

Significant differences were observed across the three latent profiles in terms of both total learned helplessness scores and all subscale scores (all p < 0.05; Table 2).

Univariate analysis of the latent profiles of learned helplessness among nursing interns

A significant association was found between the latent profile membership of learned helplessness and the following variables: gender, educational background, number of night shifts in the past month, relationship with family, scores of the six dimensions of the Clinical Learning Environment Scale, and self-esteem scale scores (P < 0.05; Table 3).

Multivariate logistic regression analysis of latent profiles of learned helplessness among nursing interns

Multivariate logistic regression was performed using the three learned helplessness latent profiles as the dependent variable and all statistically significant predictors (p < 0.05) from univariate analyses as independent variables. The coding scheme was as follows: gender (male = 1, female = 0), educational background (junior college = 1, undergraduate = 2, postgraduate = 3), night shifts in the past month (0–3 = 1, 4–6 = 2, 7–9 = 3), and family relationships (good = 1, fair = 2, poor = 3). Scores from both the Clinical Learning Environment Inventory (CLEI) and the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES) were included in the analysis as continuous variables. The results revealed that gender, educational background, number of night shifts in the past month, relationship with family members, work atmosphere in the clinical learning environment, the “Individualization” dimension, and self-esteem were potential predictors of learned helplessness among student nurses (P < 0.05), as shown in Table 4.

Discussion

Latent profile characteristics of learned helplessness among nursing interns

Our analysis identified a three-profile model as the optimal solution, indicating heterogeneity in learned helplessness among nursing interns. The profiles were labelled as follows: C1: "Low Helplessness–Low Hopelessness"; C2: "High Helplessness–Low Hopelessness"; and C3: "High Helplessness–High Hopelessness." Profile C1 ("Low Helplessness–Low Hopelessness"), comprising 33.3% of the sample, showed low scores on both helplessness and hopelessness. This profile suggests strong psychological adaptability, potentially associated with positive personal traits, robust social support, and confidence in one’s nursing career23. Profile C2 ("High Helplessness–Low Hopelessness") was the largest group at 45.2%. These interns reported high helplessness but relatively low hopelessness, indicating significant difficulties in adapting to the clinical environment without developing a pervasive sense of despair about their future. Profile C3 ("High Helplessness–High Hopelessness") accounted for 21.5% of the interns. This group exhibited high scores for both helplessness and hopelessness, indicating more pronounced psychological distress. Their feelings of helplessness appear to have generalized into long-term negative expectations for their careers, which may coincide with a risk of depression. We recommend that educators identify these distinct profiles early to implement targeted interventions. For the C1 group, we can use their positive attitude to influence other students24. To help them grow, we should assign them more difficult tasks and guide them to plan their future careers. For the C2 group, the focus should be on building a solid foundation of confidence. In future research, we can use repeated skill practices in simulated environments25, encourage them to write reflection diaries, and ensure that they receive supportive feedback from teachers26. The C3 group needs the most support. In future research, we should consider moving them away from highly stressful areas such as the emergency room. Techniques such as mindfulness training27 and narrative therapy28can help interns in this group calm their minds, change their negative thoughts, and reduce their feelings of being helpless and hopeless.

Factors predicting the three learned helplessness profiles among nursing interns

Gender

The results of this study revealed that male gender was a significant predictor of membership in the “High Helplessness–Low Hopelessness” group (OR = 5.113, P < 0.05). To understand this finding, we need to consider social norms and workforce demographics in China. Among more than 4 million registered nurses nationwide, men comprise less than 3% of the total29. Influenced by traditional views, nursing is widely seen as a job for women. This can lead to gender stereotypes against male nurses, sometimes casting doubt on their masculinity or personal identity30. Furthermore, during rotations in departments such as paediatrics or gynaecology, male interns often face distrust from patients and families. Some female patients, for example, may question their skills or feel uncomfortable due to privacy concerns31. Another relevant factor is that male nursing students may show less interest in daily tasks they find repetitive or not sufficiently challenging32. These issues can make it more difficult for them to build professional confidence and have a positive view of their career33, which increases feelings of helplessness during clinical training. At the same time, studies also highlight the particular strengths that male nurses bring. They often have better physical stamina, certain personality advantages, good teamwork ability, and potential in research and management roles. There is also growing demand for male nurses in high-intensity areas such as the Emergency Department, ICU, operating rooms, and urology wards, where their physical and mental resilience, as well as their biological characteristics, are considered beneficial34. Male interns in these environments typically report more positive experiences. Nursing educators in hospitals should prioritize the assignment of male nursing students to departments with diverse gender needs. Moreover, they should strengthen role model incentives and enhance male nursing students’ professional identity by publicizing the deeds of outstanding male nurses, thereby alleviating their clinical helplessness.

Educational background

The results of this study revealed that having an associate’s degree was a significant predictor of membership in the “High Helplessness–High Hopelessness” group (OR = 7.221, P < 0.05), whereas holding a bachelor’s degree was a significant predictor of membership in the “High Helplessness-Low Hopelessness” group (OR = 8.796, P = 0.02). These findings are consistent with the research results of Zheng Yanfei35, which may be related to curriculum design, educational stratification, and employment pressure. Bachelor’s degree programs include three years of theoretical study, emphasizing the development of critical thinking and clinical decision-making skills, which contribute to students’ strong clinical readiness. These competencies help students maintain psychological resilience under pressure and mitigate feelings of hopelessness.In contrast, associate degree programs consist of two years of theoretical learning, with a greater focus on skills training. Graduates of such programs may be more susceptible to feelings of helplessness in complex clinical environments36. Second, educational stratification in the nursing field is directly reflected in academic background preferences during recruitment. Surveys have shown that 76.79% of medical institutions prioritize recruiting candidates with a bachelor’s degree or above, and 38.40% of tertiary hospitals prefer employees with a master’s degree37. This places nursing interns with an associate’s degree at a distinct disadvantage in the job market. Future research could explore ways to reduce students’ sense of helplessness by improving curriculum quality and practical training38, establishing a diversified employment information service platform to promptly push information about emerging professional positions such as clinical research coordinators39 and elderly care workers40, and building an “academic upgrading” development channel41.

Night shift frequency

The results of this study revealed that working 4–6 night shifts during the past month was a significant predictor of membership in the “High Helplessness–Low Hopelessness” group (OR = 3.207, P < 0.05), whereas working 0–3 night shifts during the past month was a significant predictor of membership in the “Low Helplessness–Low Hopelessness” group (OR = 0.253, P < 0.05). These findings are consistent with the research results of Dobrowolska et al42. Night shift work can disrupt the body’s circadian rhythm, resulting in physical fatigue, sleep disturbances, and gastrointestinal issues, with effects potentially more pronounced for female interns43. Additionally, students often report that night shifts involve a greater proportion of non-nursing tasks, with hospitals typically staffed with fewer nurses, thereby limiting access to adequate guidance and supervision44. Studies have shown that compared with day-shift workers, nursing students on night shifts report lower job satisfaction, significantly higher levels of fatigue, and poorer clinical learning outcomes45. Therefore, it is recommended that hospital educators implement flexible scheduling, fully considering the adaptability and experience of interns, standardize the clinical preceptorship system, and clarify the responsibilities of preceptors during night shifts.

Relationship with family

The results of this study revealed that having a good relationship with family members was a significant predictor of membership in the "Low Helplessness–Low Hopelessness" group (OR = 0.071, P < 0.05). Since 2000, the pace of urban life has intensified, and many parents, preoccupied with work, have less time for meaningful communication with their children46. A lack of robust family support can lead to negative self-perceptions among young adults, manifesting as issues with self-esteem and depressive symptoms47. When faced with clinical setbacks, these individuals are more likely to attribute failures to personal inability rather than situational factors, reinforcing feelings of helplessness48. Conversely, strong family support provides a sense of security and belonging, helping mitigate fatigue and burnout49. It also serves as a source of positive reinforcement, enhancing self-efficacy and bolstering confidence to overcome professional challenges50. Future research can investigate the benefits of a "school–hospital–family collaborative" psychological support mechanism and regular family function assessments51. Additionally, a digital family support platform can be developed52 to provide online family communication skills training courses and online psychological counselling services.

Self-esteem

The results of this study revealed that high self-esteem was a significant predictor of membership in the "Low Helplessness–Low Hopelessness" group (OR = 0.834, P < 0.05), which is consistent with the findings of Wu Shudan53. Nursing students with low self-esteem may adopt self-esteem protection defence mechanisms54 to avoid others’ evaluations of their low ability and protect their own self-esteem. They may refrain from making efforts or attempting tasks, manifesting behaviours such as discouragement, giving up, and even becoming demoralized entirely, thereby increasing their sense of helplessness55. Therefore, when conducting psychological counselling courses, nursing educators should focus on teaching social skills and communication techniques to nursing students56. In addition, they can design physical activities that include emotional development exercises57 to help nursing interns maintain a relatively high level of self-esteem, thereby effectively reducing their learned helplessness.

Clinical learning environment

Compared with the "High Helplessness–High Hopelessness" group and the "High Helplessness–Low Hopelessness" group, nursing interns who experienced a positive work atmosphere and individualized teaching were more likely to be classified into the "Low Helplessness–Low Hopelessness" group (OR = 0.850, p < 0.001; OR = 0.826, p < 0.001). These findings are consistent with the research of Taewha et al58. Studies have indicated59 that a positive work atmosphere is a prerequisite for nursing students’ learning outcomes (such as knowledge and skills), confidence development, and job satisfaction and may increase their willingness to work as nurses in the future. Individualized guidance can provide targeted support for nursing students’ unique knowledge gaps, skill deficiencies, and psychological needs60. Therefore, hospitals and educators should strengthen clinical teaching management, create a positive and inclusive learning atmosphere61, increase effective feedback from preceptors62, and implement individualized teaching plans63to reduce the sense of helplessness among nursing interns.

Limitations

In this study, convenience sampling was used to recruit nursing interns from 4 tertiary grade A general hospitals. This approach may lead to a certain degree of selection bias and limit the generalizability of the results. Multicentre studies with large sample sizes should be conducted in the future to further validate the findings. Furthermore, this study adopted a cross-sectional design, and the causal relationship between self-esteem and learned helplessness could not be determined. Moreover, some potentially important confounding variables—such as stress levels, mental health status, and sleep quality—were not measured or controlled for in this study, which may have a certain impact on the interpretation of the results.In addition, data collection in this study was conducted at a single time point at the end of the internship, which might have introduced confounding variables such as employment pressure.To address these limitations, we plan to conduct a longitudinal follow-up study in the future to depict the trajectory and dynamic changes in learned helplessness throughout the entire internship period, thereby revealing its key influencing factors and causal mechanisms more accurately.

Conclusion

This study identified three distinct profiles of learned helplessness among nursing interns: "Low Helplessness–Low Hopelessness," "High Helplessness–Low Hopelessness," and "High Helplessness–High Hopelessness." Gender, educational background, number of night shifts, relationship with family members, self-esteem, work atmosphere, and individualized teaching are predictors of the latent profiles of learned helplessness among nursing interns. These findings emphasize the need for tailored educational and support strategies from both academic institutions and hospitals designed to address the specific needs of each profile to effectively mitigate feelings of learned helplessness.

Data availability

The data supporting the conclusions of this study will be provided from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Ren, H. et al. Global prevalence of nurse turnover rates: A meta-analysis of 21 studies from 14 countries. J. Nurs. Manag. 2024, 5063998. https://doi.org/10.1155/2024/5063998 (2024).

Jiang, H. et al. Professional calling among nursing students: A latent profile analysis. BMC Nurs. 22, 299. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-023-01470-y (2023).

Zhang, Y. et al. Career aspiration and influencing factors study of intern nursing students: A latent profile analysis. Nurse Educ. Today https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2024.106546 (2025).

Scherer, K. R. Learned helplessness revisited: Biased evaluation of goals and action potential are major risk factors for emotional disturbance. Cogn. Emot. 36, 1021–1026. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2022.2141002 (2022).

Seligman, M. E. & Maier, S. F. Failure to escape traumatic shock. J. Exp. Psychol. 74, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0024514 (1967).

Abramson, L. Y., Seligman, M. E. & Teasdale, J. D. Learned helplessness in humans: Critique and reformulation. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 87, 49–74 (1978).

He, H. Students’ Learned Helplessness and Teachers’ Care in EFL Classrooms. Front. Psychol. 12, 806587 (2021).

Sinha, P., Calfee, C. S. & Delucchi, K. L. Practitioner’s Guide to Latent Class Analysis: Methodological Considerations and Common Pitfalls. Crit Care Med 49, e63–e79. https://doi.org/10.1097/ccm.0000000000004710 (2021).

Bandura, A. Social cognitive theory: an agentic perspective. Annu Rev Psychol 52, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1 (2001).

Panda, S. et al. Challenges faced by student nurses and midwives in clinical learning environment - A systematic review and meta-synthesis. Nurse Educ. Today https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2021.104875 (2021).

Alkubati, S. A. et al. The mediating effect of belongingness on the relationship between perceived stress and clinical learning environment and supervision among nursing internship students. BMC Nurs. 24, 577. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-025-03222-6 (2025).

Joy, G. V. et al. Nurses’ self-esteem, self-compassion and psychological resilience during COVID-19 pandemic. Nurs. Open 10, 4404–4412. https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.1682 (2023).

Liu, Y., Yang, C. & Zou, G. Self-esteem, job insecurity, and psychological distress among chinese nurses. BMC Nurs. 20, 141. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-021-00665-5 (2021).

Peduzzi, P., Concato, J., Kemper, E., Holford, T. R. & Feinstein, A. R. A simulation study of the number of events per variable in logistic regression analysis. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 49, 1373–1379. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0895-4356(96)00236-3 (1996).

Nylund-Gibson, K. et al. Ten frequently asked questions about latent transition analysis. Psychol Methods 28, 284–300. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000486 (2023).

Wu, X., Zeng, H. & Ma, S. Development of Learned Helplessness Scale and Its Relationship with Personality. J. Sun Yat-Sen Univ. 30, 357–361 (2008).

Zhu, W. The development and test of the clinical learning environment scale for nursing.Master’s thesis, China Medical University, (2005).

Rosenberg, F. R., Rosenberg, M. & McCord. Self-esteem and delinquency. J Youth Adolesc 7, 279–294 (1978).

Lumei, T. Shortcoming and Merits of Chinese Version of Rosenberg (1965) Self-Esteem Scale. Psychol. Explor. 26, 88–91 (2006).

Vrieze, S. I. Model selection and psychological theory: a discussion of the differences between the Akaike information criterion (AIC) and the Bayesian information criterion (BIC). Psychol Methods 17, 228–243. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027127 (2012).

MacLean, E. & Dendukuri, N. Latent class analysis and the need for clear reporting of methods. Clin. Infectious Dis. 73, e2285–e2286. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa1131 (2021).

Petras, H. & Masyn, K. General Growth Mixture Analysis with Antecedents and Consequences of Change (Springer, 2010).

Shaw, S. C. K. Hopelessness, helplessness and resilience: The importance of safeguarding our trainees’ mental wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nurse Educ. Pract. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2020.102780 (2020).

Bahar, A., Kocacal, E. & Maras, G. B. Impact of the peer education model on nursing students’ anxiety and psychomotor skill performance: A quasi-experimental study. Niger J. Clin. Pract. 25, 677–682. https://doi.org/10.4103/njcp.njcp_1905_21 (2022).

Li, J. et al. Effects of Simulation-Based Deliberate Practice on Nursing Students’ Communication, Empathy, and Self-Efficacy. J. Nurs. Educ. 58, 681–689. https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20191120-02 (2019).

Cardoso, M. D., Dias, P. L. M., da Rocha Cunha, M. L., Mohallem, A. & Dutra, L. A. How is feedback perceived by brazilian students and faculty from a nursing school?. Nurse Educ. Pract. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2024.104057 (2024).

Van der Riet, P., Levett-Jones, T. & Aquino-Russell, C. The effectiveness of mindfulness meditation for nurses and nursing students: An integrated literature review. Nurse Educ. Today 65, 201–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2018.03.018 (2018).

Aloufi, M. A., Jarden, R. J., Gerdtz, M. F. & Kapp, S. Reducing stress, anxiety and depression in undergraduate nursing students: Systematic review. Nurse Educ. Today https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2021.104877 (2021).

Wu, C. et al. Career identity and career success among Chinese male nurses: The mediating role of work engagement. J. Nurs. Manag. 30, 3350–3359. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.13782 (2022).

Chen, Y., Zhang, Y. & Jin, R. Professional Identity of Male Nursing Students in 3-Year Colleges and Junior Male Nurses in China. Am. J. Mens. Health https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988320936583 (2020).

Vatandost, S., Oshvandi, K., Ahmadi, F. & Cheraghi, F. The challenges of male nurses in the care of female patients in Iran. Inter. Nurs. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1111/inr.12582 (2020).

Appiah, S., Appiah, E. O. & Lamptey, V. N. L. Experiences and motivations of male nurses in a tertiary hospital in ghana. SAGE Open Nurs. https://doi.org/10.1177/23779608211044598 (2021).

Shin, S.-Y. & Lim, E.-J. Clinical work and life of mid-career male nurses: A qualitative study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18, 6224. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18126224 (2021).

Mao, A. et al. Factors influencing recruitment and retention of male nurses in macau and mainland China: A collaborative, qualitative study. BMC Nurs. 19, 104. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-020-00497-9 (2020).

Zheng, Y. A study on undergraduate’s helplessness, achievement motivation and their relationship in sports learning. Master’s thesis, Fujian Normal University, (2019).

Wang, X. & Li, H. Correlation analysis between employment pressure and career decision-making self-efficacy of nursing undergraduate students. Occup. Health 40, 2265–2270. https://doi.org/10.13329/j.cnki.zyyjk.2024.0449 (2024).

Zhang, W., Yi, S., Xia, X. & Luo, X. The Cultivation of Higher Vocational Nursing Personnel Based on Industry Demand. Health Voc. Educ. 41, 11–15. https://doi.org/10.20037/j.issn.1671-1246.2023.16.04 (2023).

Ramos-Ramos, A. et al. Academic and Employment Preferences of Nursing Students at the University of Las Palmas of Gran Canaria: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nurs. Rep. 14, 3328–3345. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14040241 (2024).

Fisher, E. et al. Finding the right candidate: Developing hiring guidelines for screening applicants for clinical research coordinator positions. J. Clin. Transl. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1017/cts.2021.853 (2022).

Travers, J. L., Teitelman, A. M., Jenkins, K. A. & Castle, N. G. Exploring social-based discrimination among nursing home certified nursing assistants. Nurs. Inq. https://doi.org/10.1111/nin.12315 (2020).

Downey, K. M. & Asselin, M. E. Accelerated Master’s Programs in Nursing for Non-Nurses: An Integrative Review of Students’ and Faculty’s Perceptions. J. Prof. Nurs. 31, 215–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.profnurs.2014.10.002 (2015).

Dobrowolska, B. et al. Exploring the meaning of night shift placement in nursing education: A european multicentre qualitative study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103687 (2020).

Panwar, A., Bagla, R. K., Mohan, M. & Rathore, B. B. Influence of shift work on sleep quality and circadian patterns of heart rate variability among nurses. J. Family Med. Primary Care 13, 3345–3349. https://doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_158_24 (2024).

Rivera, L. & White, A. Exploring clinical innovation: Nursing students’ night-shift experience. J. Nurs. Educ. 61, 345–347 (2022).

Bahramirad, F., Heshmatifar, N. & Rad, M. Students’ perception of problems and benefits of night shift nursing internship: A qualitative study. J. Educ. Health Promotion 9, 287. https://doi.org/10.4103/jehp.jehp_227_20 (2020).

Lu, Y., Zhang, R. & Du, H. Family Structure, Family Instability, and Child Psychological Well-Being in the Context of Migration: Evidence From Sequence Analysis in China. Child Dev. 92, e416–e438. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13496 (2021).

Caravaca-Sánchez, F., Aizpurua, E. & Stephenson, A. Substance Use, Family Functionality, and Mental Health among College Students in Spain. Soc. Work Public Health 36, 221–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/19371918.2020.1869134 (2021).

Li, R. et al. The influence of family function on occupational attitude of Chinese nursing students in the probation period: The moderation effect of social support. J. Korean Acad. Nurs. 51, 746. https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.21103 (2021).

An, J., Zhu, X., Shi, Z. & An, J. A serial mediating effect of perceived family support on psychological well-being. BMC Public Health 24, 940. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-18476-z (2024).

Hu, L., He, W. & Zhou, L. Association Between Family Support and Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy in a Cross-Sectional Study. Nurs. Open https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.70210 (2025).

Caño González, A. & Rodríguez-Naranjo, C. The McMaster Family Assessment Device (FAD) dimensions involved in the prediction of adolescent depressive symptoms and their mediating role in regard to socioeconomic status. Fam Process 63, 414–427, https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12867 (2024).

Van Doorn, M. et al. The Effects of a Digital, Transdiagnostic, Clinically and Peer-Moderated Treatment Platform for Young People With Emerging Mental Health Complaints: Repeated Measures Within-Subjects Study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth https://doi.org/10.2196/50636 (2023).

Wu, S. Learned helplessness in the college students’ physical education learning effects on physical self-esteem. Master’s thesis, Zhejiang Normal University, (2016).

Witkowski, T. & Stiensmeier-Pelster, J. Performance deficits following failure: Learned helplessness or self-esteem protection. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 37, 59271. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8309.1998.tb01157.x (1998).

Charbonnier, E. et al. The Effect of Intervention Approaches of Emotion Regulation and Learning Strategies on Students’ Learning and Mental Health. Inquiry https://doi.org/10.1177/00469580231159962 (2023).

Dugué, M., Sirost, O. & Dosseville, F. A literature review of emotional intelligence and nursing education. Nurse Educ. Pract. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2021.103124 (2021).

Wang, K., Li, Y., Zhang, T. & Luo, J. The Relationship among College Students’ Physical Exercise, Self-Efficacy, Emotional Intelligence, and Subjective Well-Being. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811596 (2022).

Lee, T. et al. Personal factors and clinical learning environment as predictors of nursing students’ readiness for practice: A structural equation modeling analysis. Asian Nurs. Res. 17, 44–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anr.2023.01.003 (2023).

Ying, W. et al. The mediating role of professional commitment between the clinical learning environment and learning engagement of nursing students in clinical practice: a cross-sectional study. Nurse Educ. Today https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2022.105677 (2023).

Cusanza, S. A., Speroni, K. G., Curran, C. A. & Azizi, D. Effect of individualized learning plans on nurse learning outcomes and risk mitigation. J. Healthcare Risk Manag. J. Am. Soc. Healthcare Risk Manag. 40, 17–29. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhrm.21442 (2021).

Dursun Ergezen, F., Akcan, A. & Kol, E. Nursing students’ expectations, satisfaction, and perceptions regarding clinical learning environment: A cross-sectional, profile study from turkey. Nurse Educ. Pract. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2022.103333 (2022).

Javadi, A. & Keshmiri, F. Surgical Nursing Students’ Perception of Feedback in Clinical Education: A Mixed-method Study. Educ Health (Abingdon) 36, 131–134. https://doi.org/10.4103/efh.efh_55_23 (2023).

Lim, S. et al. Peer mentoring programs for nursing students: A mixed methods systematic review. Nurse Educ. Today https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2022.105577 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thank everyone in the research team and all nursing students who participated in the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XiaoxiaoLi and ChaoranChen designed the study. YihanLiu,andYanyanJiao were responsible for data collection. QinqinLiu and Lili Jia participated in data analysis. Xiaoxiao Li prepared the first draft. ChaoranChen and ZhongqiangGuo were responsible for manuscript revision. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

This study has been approved by the Institutional Review Board of Henan Key Laboratory of Psychology and Behavior ( number: 20230516001) and is conducted in strict accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Before the implementation of the study, all participants were fully informed of the research purpose, and detailed explanations were provided on key points such as data confidentiality, anonymity protection measures, and the fact that this study does not collect personal identity information. The study was officially initiated only after obtaining the informed consent of all included subjects, so as to ensure that all collected data are used solely for research purposes.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, X., Jiao, Y., Liu, Q. et al. Latent profile analysis and predictive factors of learned helplessness among nursing students in clinical practice. Sci Rep 16, 5354 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-37867-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-37867-3