Abstract

Company profiles are increasingly used to construct the corporate brand of Fortune Global 500 Chinese Manufacturing Companies (FG500CMCs). However, the communication of the corporate brand through the company profile is not sufficiently explored. This article explored the discursive strategies that were exploited to construct the desired brand identities of the FG500CMCs. Through the approach of critical genre analysis, it is found that the branding of the FG500CMCs is realized by the strategic organization of rhetorical moves, the purposeful employment of rhetorical devices, and tactical wording. All the obligatory moves identified primarily highlight a set of attributes indicating the strengths, competitiveness, and superiority of the FG500CMCs. This projects the distinctiveness of the brand identities of the companies. The strengths, competitiveness, and superiority are constructed by deploying graduation resources, appropriating numerical resources, adopting high-end and high-tech-related terms, and exploiting endorsement, authentication, and altruism. Besides analyzing the lexico-grammatical features and discursive techniques, this article also investigates how the FG500CMCs’ particular attributes and strengths are covertly conveyed through the strategic organization and distribution of the moves. This provides a more comprehensive explication and thus gives new insights into the body of knowledge on the discursive construction of corporate branding. With grounded elaboration on the tactful use of language and covert arrangement of the moves, this article also sheds light on the content design of the ‘company profile’ for shaping stakeholders’ and the public’s perception of the corporate brand.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A corporate brand is a valuable, strategic, and sustainable resource for a company because it has unique characteristics, including value, rarity, durability, and imperfect imitability (Balmer and Gray, 2003). Although an increasing number of Chinese companies are ranked in the Fortune Global 500, the international community barely recognizes China’s corporate brand. Among all the Chinese companies, only Huawei has been ranked as one of the top global brands by Interbrand in the last five years (Interbrand, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021). The Chinese government presses ahead with developing and strengthening Chinese corporate brands in the 14th national five-year plan, emphasizing increasing the influence and competitiveness of indigenous Chinese brands.

Corporate branding involves enhancing the competitiveness of hard power such as innovation, cutting-edge technologies, a comprehensive industrial structure, and high-performing products; it also requires effective brand communication (Davies et al., 2001; Keller, 2009). The dominant contributor to corporate brand success is a corporate identity that appeals to various stakeholders (Markwick and Fill, 1997; Suvatjis and de Chernatony, 2005; Leitch and Davenport, 2011). Corporate brand identity is built on essential attributes that make a company unique and differentiated (Albert and Whetten, 1985; Dutton et al., 1994). Corporate brand identity stems from the source of the company, whereas the corporate brand image is the entire set of impressions and perceptions stakeholders hold about a particular brand (Kotler, 1988; Herzog, 1963). Strategic communication of corporate brand identities shapes the brand image in the minds of stakeholders (Nandan, 2005). In other words, effective communication can minimize and even eliminate the gap between corporate identity and stakeholders’ perceptions of the brand.

Marketing communication is critical in shaping stakeholders’ knowledge and mindset toward corporate brands (Keller, 2009). In this sense, corporate branding is a communicative activity and, thus, a discursive practice (Lischinsky, 2017). There is growing interest in exploring how corporate brand identities are constructed through corporate websites (e.g., Chen and Eriksson, 2019; Jonsen et al., 2021; Tenca, 2018). By adopting Bhatia’s (2004) genre-analysis approach, this research shows how the Fortune Global 500 Chinese Manufacturing Companies (FG500CMCs) are branded through the strategic organization of rhetorical moves and the exploitation of discursive strategies in company profiles.

Through comprehensive explication of the tactful use of language and covert arrangement of the moves, this article gives new insights into the content design of ‘company profile’ for influencing stakeholders’ and the public’s perception of the corporate brand. As delivering the value and proposition of a company through brand communication to the stakeholders is a critical step to surpassing the competition (Aaker, 1997, 1999; Aaker et al., 2001; Ingenhoff and Fuhrer, 2010; Kotler, 1989), the illumination on the linguistic construction of corporate brand provided by this article could help companies win the increasingly intense competition in the global business context.

Literature review

‘Corporate branding’ can be conceptualized as “a means by which to construct organizations’ distinctive identities” (Balmer and Gray, 2003), which differentiate a company from others in a particular industry. A favorably perceived corporate brand affects tangible and intangible firm value and attracts employees, investors, and consumers (Balmer, 2012).

Regarding approaches and processes for corporate branding, various models are proposed by different scholars (e.g., Harris and de Chernatony, 2001; Hatch and Schults, 2001; Keller, 2009). These scholars unanimously address the essential role of communication in corporate branding. In particular, Keller’s (2001) customer-based brand equity model views corporate branding as a process in which the corporate brand identity is strategically communicated to stakeholders. As identity is viewed as socially constructed in and through discourse and communication (De Fina, 2010a), the commercial concept of corporate brand identity is constructed and communicated through specific discursive processes and practices (Machin and Thornborrow, 2003; Mumby, 2014; Turlow and Aiello, 2007).

There is growing interest in the investigation of the discursive strategies used for the construction of corporate brand identities (e.g., Agozie and Nat, 2022; Cheng and Ho, 2016; Jonsen et al., 2021; Stutzer et al., 2021). A substantial body of research in the field of critical discourse analysis has looked at the linguistic strategies businesses employ in a range of texts and genres to construct their competitive attributes and strengths (e.g., Bondi, 2016; Breeze, 2012; Brei and Böhm, 2014; Fuoli, 2012, 2017; Koller, 2008). Besides, the employment of visual strategies by businesses to influence stakeholders’ perceptions of their corporate brand image has also been studied in some multimodal discourse analysis research. (e.g., Chen and Eriksson, 2019; Koller, 2009; Tenca, 2018). In addition, some other studies adopted a corpus-based discourse analysis approach to investigate the language patterns used to project the intended corporate brand identities (e.g., Liu and Wu, 2015; PAD research group, 2016). These studies have shown that businesses exploit various linguistic and semiotic resources in their public discourse to foster a positive corporate brand image.

In comparison, there are not as many studies that use a genre-analysis approach to explore how language is covertly used to construct a favorable corporate brand identity. Tenca (2018) looked at how multimodal tactics and linguistic markers were used in “About Us” webpages to frame corporate brand image, but the genre’s rhetorical structure was not examined. Kristina and Hashima (2017) explored how consumers’ perceptions of the corporate brand image were shaped by patterns of rhetorical structure and genre-specific language features manifested in the company profile. As Kristina and Hashima (2017) only analyzed two batik company profiles and the discursive construction is affected by Indonesian traditional culture, the findings of the language used for corporate identity construction lack representativeness. Casañ-Pitarch (2015) identified the rhetorical moves of the world’s top banks’ company profiles, which include presentation, history, group members, sponsorship, and awards. However, the description of the rhetorical moves of banks’ profiles cannot be generalized to other industrial areas (Casañ-Pitarch, 2015).

Corporate websites are considered a crucial image-building tool for conveying impressions and influencing stakeholders’ and the public’s opinions of organizations (Bravo et al., 2013; Connolly-Ahern and Broadway, 2007; Esrock and Leichty, 2000; Kent et al., 2003; Opoku et al., 2006). ‘Company profile’ is a crucial section of a corporate website that describes ‘who the company is’ and ‘what the company does’ (Lam, 2009). This article uses a genre-analysis approach to explore how the corporate brand identities of the FG500CMCs are discursively constructed in company profiles. Besides analyzing the discursive techniques and lexico-grammatical features used for branding purposes, this article also examines the genre’s organizational structure and move patterns. This gives a more comprehensive explication of the discursive construction of corporate brand identities.

Bhatia (1993) defines genre as a recognizable communicative event characterized by a set of communicative purposes identified and mutually understood by the members of the profession or academic community in which it regularly occurs. It is often highly structured and conventionalized, with constraints on allowable contributions in terms of their intent, positioning, form, and functional value. These constraints, however, are often exploited by the expert members of the discourse community to achieve private intentions within the framework of socially recognized purposes. In this regard, company profiles can be categorized as a genre with its specific communicative purposes, conventional form, and constraints, and the constraints are probably exploited by businesses to achieve organizational purposes.

According to Bhatia’s (2004) approach, genre analysis can be conducted from four perspectives: textual, socio-cognitive, ethnographic, and socio-critical. The textual perspective mainly investigates the rhetorical moves, lexico-grammatical features, textualization, and communicative purposes of discourse. The social-cognitive perspective primarily explores the cognitive strategies employed to achieve conventional communicative purposes and the ‘private’ or organizational purposes. The ethnographic perspective focuses on investigating the informants’ narratives of the production of the genre. The socio-cognitive perspective essentially examines the socio-pragmatic factors that contextualize the construction of the genre.

The discursive construction of a corporate brand is characterized by the predominant use of evaluative language (Morrish and Sauntson, 2013). The appraisal theory proposed by Martin and White (2005) is widely recognized as a reliable approach for analyzing the evaluative language strategies used to portray the strengths and trustworthiness of organizations (Fuoli, 2012). The system of appraisal framework consists of three domains: attitude, engagement, and graduation. Graduation resources are constantly employed in corporate discourse to highlight the strengths and superiors (Suen, 2013).

Graduation concerns with upscaling and downscaling of attitudinal meanings or engagement values (Martin and White, 2005). It can be realized by superlatives, maximization (e.g., complete, a full range of), repetition, metaphor, number (e.g., a few, many), mass (e.g., large, small), and extent (e.g., wide-spread, recent), covering scope in space and time as well as proximity in space and time. Maximizers and superlatives both upscale the evaluative prosody to the highest degree. Repetition is realized by repeating the same lexical item or by assembling lists of terms that are closely related semantically.

Through a genre-analysis approach, this article examines the lexico-grammatical features and discursive techniques and how the FG500CMCs’ distinctive qualities and strengths are subtly communicated through the tactical arrangement and distribution of the moves. This provides a more comprehensive explication and thus gives new insights into the body of knowledge on the discursive construction of corporate branding.

Research methods

The primary research methodology used in this study is qualitative, with a small amount of statistical description to help generalize the genre’s moves and move patterns. Counting is integral to the qualitative analysis process, particularly when identifying patterns in the data and drawing general conclusions from those patterns (Sandelowski, 2001).

Analytical framework

The researchers apply Bhatia’s (2004) multidimensional and multiperspective genre-analysis approach as the macro analytical framework because this approach offers a grounded elaboration of language use in professional settings (Chow, 2017; Cheong, 2013). In order to explore the discursive branding of FG500CMCs, the study is conducted from textual and socio-cognitive perspectives. From the textual perspective, the researchers explore how communication of brand identities is achieved through the organization of rhetorical moves. Regarding the socio-cognitive perspective, they probe into how brand identities are constructed by discursive strategies manifested in company profiles.

Swales (2004) defines a move as a “discoursal or rhetorical unit that performs a coherent communicative function in a written or spoken discourse”. A ‘step’ is a sub-unit of a move to support the function of the move, and a move normally consists of a number of steps (Bhatia, 1993). Moves in the study are determined by identifying the communicative function of a string of text. Based on the frequency of occurrence, moves are classified into three types: obligatory moves, optional moves, and occasional moves (Peacock, 2002; Swales, 1990). However, there are no fixed criteria to distinguish the three types of moves (Swales, 1990).

Data selection

The company profiles of the 2021 Fortune Global 500 Chinese manufacturing companies’ websites are selected as the source of data (FG500CMCs). By referring to Fortune Magazine and ‘Guidelines for Industry Classification of Listed Companies’ (China Securities Regulatory Commission, 2021), the researchers identified 44 FG500CMCs. The 44 companies primarily operate in the appliance industry, telecommunication industry, mineral industry, machinery industry, automobile industry, non-ferrous metal industry, petrochemical industry, textile industry, and pharmaceutical industry. Webzip 7.0 is adopted to collect and save the company profiles of FG500CMCs.

Two significant factors justify the selection of data. First, websites of large and high-revenue companies are more likely to communicate the corporate brand via websites than those of low-revenue companies (Hwang et al., 2003). Secondly, China aspires to build valuable brands in the manufacturing industry and raise its manufacturing power, which is promulgated in ‘Made in China 2025’ by the state council. Therefore, it is optimal to confine company profiles of FG500CMCs as the data to explore the discursive construction of corporate branding.

Methods of analysis

The researchers first compile a corpus of company profiles for the FG500CMCs. Secondly, they go through the company profiles to obtain a ‘big-picture’ understanding of the communicative purposes. Then, multiple readings and reflections of the texts are done to categorize the moves in the genre of ‘company profile.’ Afterward, the researchers identify the steps. They search for any common functional themes represented by diverse text segments that have been identified, especially those in proximity to each other or usually occur in approximately the same location in different company profiles. These functional themes can be grouped together, which reflect the different steps of a particular move type.

Regarding the analysis of the moves and steps, the researchers primarily use linguistic clues to categorize the moves and steps. Meanwhile, Kristina et al.’s model (2017) and Casañ-Pitarch’s (2015) are both used as references for coding texts. The two models can only be used as references because they have limitations and cannot be generalized to represent companies in other industries and cultures. In addition, Biber, Connor, and Upton’s (2007) ‘general steps’ used to conduct move analysis are adopted as a guideline to code the texts and identify the moves and steps. It is presented in Table 1. The identification of a move and its steps is demonstrated in the following example.

Example: SAIC Motor

Looking ahead, SAIC Motor will keep pace with technological progress, market evolution, and industry changes while accelerating its innovative development strategy in the fields of electrification, intelligent connectivity, sharing, and globalization. (It will not only strive to improve its performance, but also build an innovation chain to upgrade its business, so as to come out on top in the restructuring global automotive industry. The company also plans to accelerate its business transformation and upgrading, and make great strides towards becoming a world-class auto company with international competitiveness and a strong brand influence).

In the above example, the text segment primarily introduces and brands the companies’ development strategies and aspirations. This is suggested by linguistic clues such as ‘innovative development strategy,’ ‘come out on top in the restructuring global automotive industry,’ and ‘becoming a world-class auto company with international competitiveness and a strong brand influence.’ This is also indicated by the semantic meaning of the string of text. As a move is a “discoursal or rhetorical unit that performs a coherent communicative function in a written or spoken discourse” (Swales, 1990), this text segment as a discoursal unit is identified as a move.

Within the move, the sentence underlined communicates SAIC Motor’s development strategy, which is suggested by the linguistic clues ‘will keep pace with technological progress, market evolution, and industry changes’ and ‘accelerating its innovative development strategy.’ The text in the bracket primarily functions to positively introduce the company’s aspirations, and this is indicated by the linguistic clues ‘so as to come out on top in the restructuring global automotive industry’ and ‘becoming a world-class auto company with international competitiveness and a strong brand influence.’ Therefore, two semantic themes are found in this move, which are in proximity to each other. They reflect the two steps of this move.

The researchers conducted a pilot-coding before segmenting a particular text into moves. Initial analysis was discussed until they reached an agreement on the functional purposes that are being realized by the text segments. This resulted in a protocol of move features and functions for the genre. Then, the researchers independently coded the texts to identify the moves. When there was disagreement between the researchers, they discussed how to resolve the discrepancies. The efficiency of the reliability of coding is 89%. This accounts for the reliability of the analysis of the entire corpus because inter-rater reliability of 80% is already considered satisfactory (Biber et al., 2007). There are two raters for this study, and the inter-rater reliability is calculated by using the following formula:

-

IRR = TA/TR*100

-

IRR: the inter-rater reliability (%)

-

TA: the total number of agreements in the ratings

-

TR: the total number of ratings given by each rater

Moves are normally classified into three types: obligatory moves, optional moves, and occasional moves. However, there are no fixed criteria to distinguish the three types of moves. Previous literature labels moves with high frequency in a genre as obligatory moves (Peacock, 2002; Swales, 1990), while moves with low frequency are labeled as optional moves. Nevertheless, there is no consensus regarding the exact frequencies to distinguish obligatory moves from optional ones (Swales, 2004).

Based on Casañ-Pitarch’s (2005) descriptor, the moves with a frequency in terms of percentage over 50% in “About Us” of banks’ websites are considered obligatory moves; the moves with a frequency between 30 and 50% are considered optional moves; and the moves with a frequency below 30% are considered occasional moves. Considering the variation of moves structure of corporate websites, Casañ-Pitarch’s descriptor is taken as the reference for the pilot study. After a preliminary investigation into the data of the present study, the researcher found that the frequency of the moves in the “company profile” of the FG500CMCs is quite similar to Casañ-Pitarch’s (2015) model. Therefore, his descriptor is adopted. However, to be in tandem with Peacock’s (2002) and Swales’ (1990) recommendation to recognize moves with high frequency in a genre as obligatory moves, 60–100% is adopted for the current study rather than 50–100%, which was used by Casañ-Pitarch’s (2015). In addition, the patterns of moves and steps were also identified and categorized as either cyclical or linear.

In order to analyze the lexico-grammatical features and rhetorical techniques employed for the construction of the corporate brand identities, the researchers repeatedly scanned the texts of the ‘company profile’ to code and scrutinize the language patterns. Martin and White’s (2005) appraisal analysis theory, particularly the graduation subsystem framework, is adopted to explain how the companies’ strengths and superiors are highlighted. In addition, other language resources used for branding purposes are also examined. For example, the size of a company can be measured in a number of ways, including total assets, sales turnover, the number of employees, value-added, and market size (Becker-Blease et al., 2010). It is possible to brand the size of a corporation by utilizing graduation resources like “the largest” and other strategies like using large numbers to denote a large number of total assets or a large number of employees.

Analysis and findings

Moves of company profiles of FG500CMCs

Through a detailed analysis of the 44 company profiles, the researchers identified seven rhetorical moves. The description and frequency of occurrence of the moves are illustrated in Table 2 and Fig. 1, respectively.

In Table 2, seven moves are identified in the corpus of company profiles. While Move 1, Move 2, Move 5, and Move 6 are presented in one general functional-semantic way, Move 3, Move 4, and Move 7 are realized in several steps. It is also found that most of the moves occur in over half of the company profiles; one is repeated in approximately one-third of the company profiles, and the other appears in only several company profiles. The frequency of occurrence of the moves is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Figure 1 shows that five moves are obligatory, one is optional, and the other is occasional. The five obligatory moves are represented by Move 1, Move 3, Move 4, Move 5, and Move 7. Each of the five obligatory moves highlights a respective set of attributes indicating the strengths, competitiveness, and superiority of the companies. This projects the distinctiveness of the corporate brand identities of the FG500CMCs. Move 2 is optional, occurring in 34% of the company profiles. This move contributes to a minor communicative purpose of the company profiles: constructing rapport with the government. Move 6 is occasional, occurring only in 11% of the company profiles. This move constructs the companies as benefactors of the global community. As the primary communicative purposes of a genre are determined by its obligatory moves (Bhatia, 1993, 2004; Swales, 1990), it can be concluded that this genre primarily serves to construct the corporate brand of FG500CMCs discursively.

Move patterns

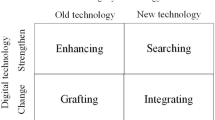

Moves may occur in a flexible pattern, and the patterns of moves are demonstrated in Fig. 2.

NO.: the number of move patterns; Move Pattern: the particular pattern of move organization; No. of company profiles: the number of the company profiles for each move pattern; Percentage: the percentage of the company profiles for each move pattern (the number of the company profiles for each move pattern/44 * 100%); M: Move.

Fig. 2 shows that only four company profiles demonstrate a linear move pattern. In contrast, 40 company profiles manifest cyclical patterns. The cyclical moves are Move 1, Move 3, Move 4, and Move 5. They are repeated in six flexible move patterns. Move 1 and Move 3, respectively, are repeated in 40 and 29 company profiles, and they are the most prominent components in five of the seven move patterns.

Move 1 is used in the company profile to introduce and brand the company briefly. Some content in Move 1 reoccurred in six of the seven patterns. This strategy is not a mere repeat of a similar move but is used to reinforce the companies’ competitive aspects by highlighting and elaborating on the specific content of the move again.

Likewise, the same strategy could be found in Move 3, which is repeated in five of the six patterns. As Move 3 functions to brand the companies’ scale, global positioning, and strength, the frequent reoccurrence of this move helps reinforce the companies’ emphasis on competitiveness, superiority, and power concerning their scale, position, status, and strength.

The strategy of repeating a move is not limited to repeating a particular move in a company profile. This study identified the strategy of repeating two moves within a move structure. It is found in 40 company profiles. This strategy could be found in six out of the seven flexible move structures. It is used prominently in move patterns M1-M3-M1-M4-M5-M3-M7, followed by M1-M2-M1-M3-M5-M4-M5 and M1-M3-M1-M4-M3-M5-M7. This analysis shows that the strategy of repeating more than one move is adopted in most company profiles for its synergetic effects and benefits.

Rhetorical strategies employed for construction of corporate brand

Various rhetorical strategies are exploited to realize the communicative purposes of the moves. This is elaborated in the following part.

Move 1: Briefly introducing and branding the companies

This move presents a panorama of the companies. Strategic exploitation of evaluative language is a salient feature of language use in the introduction section of organizations (Wu and Cheong, 2020). The presentation in this move is characterized by the prevalent use of appraisal resources, specifically graduation resources. This projects the most competitive aspects and the most prominent competitiveness of the companies (Fuoli, 2012). It is found that many of the lexical and phrasal resources used in this move have the semantic meaning of graduation resources. Table 3 shows how these resources are used to brand the companies.

Table 3 shows that the companies’ position and influence are intensified by maximizers and superlatives such as ‘leading,’ ‘the first,’ ‘the oldest,’ ‘the earliest.’ Besides, a few companies’ status is reinforced by the use of metaphors manifested by ‘cradle’ and ‘backbone’.

The scale of the companies’ industry and business is strengthened by the use of superlatives such as ‘largest’ as well as lexical resources belonging to the semantic meaning of the “mass” category such as ‘large,’ ‘large-sized,’ ‘super-large,’ ‘extra-large’ and ‘over-sized,’ which is manifested in Table 3.

Repetition is exploited by 20 companies to signal that they have a complete industry system covering a full portfolio of products. This is shown in Example 4. Apart from using repetition, the companies’ product variety is intensified by maximizers such as ‘an entire range of,’ ‘complete,’ ‘all types of,’ and the superlative ‘the most complete,’ which is manifested in Example 2.

The companies’ level of internationalization is highlighted by linguistic resources related to the semantic meaning of extent with respect to distribution in space. Words and phrases such as ‘international,’ ‘global,’ and ‘throughout the word’ connote the companies’ international exposure.

Besides employing the aforementioned graduation resources, lexical and phrasal resources bearing ‘innovation,’ ‘hi-tech,’ and ‘high-end’ connotations are widely used to reinforce the companies’ strengths in cutting-edge technology and innovation. The researchers have identified 26 words and phrases related to this semantic category, which is manifested in Example 8.

Example 8: China North Industries Corporation Limited is the main platform responsible for developing mechanized, digitized and intellectualized equipment for PLA, plays a core role in developing destructive-attack devices for PLA and acts as a major carrier in R&D and manufacture of modernized new-generation army systemic equipment.

The strengths and advantages encapsulated by the aforementioned appraisal resources differentiate the companies from others in their respective fields, thus projecting a high-end corporate brand. These constructed aspects of competitiveness are further elucidated in the following moves by using other rhetorical strategies.

Move 2: Constructing an obedient and close relationship with the government

By searching the National Enterprise Credit Publicity System, the researchers found that nine of the 44 companies are private or joint ventures, while the other 36 are state-owned enterprises. This move occurred in 15 company profiles of state-owned companies, while it never appeared in those of non-state-owned corporations. In this move, the state-owned companies either praise their contribution to the country’s economic development or show appreciation for the government’s support. This is manifested in Example 9.

Example 9 Shougang group

The party and the State have attached great importance to the development of Shougang and dozens of Party and State leaders have visited Shougang for advisory supervision. In February 2019, General Secretary Xi Jingping visited the Shougang Park for inspection and greetings and make important instructions, which injected powerful impetus to the high-quality development of Shougang.

In Example 9, the company shows its recognition and appreciation of the government’s support by stating that Secretary Xi Jingping’s inspection injected powerful impetus into its high-quality development, indicating the company’s obedience and compliance to the government’s directives.

Move 3: Branding the company’s scale, global position and strength

Compared with Move 1, Move 3 is more oriented towards the purpose of branding other than introducing the companies. Four major points are intentionally highlighted in this move: companies’ scale, companies’ positions, companies’ strengths in manufacturing, and companies’ strengths in technology and innovation. These aspects of the companies are branded through the conscious use of linguistic strategies.

Step 1: branding the companies’ scale

In this step, the companies’ scale is magnified by boasting about their number of employees, total assets, sales revenue, global operation, number of subsidiaries or branches, and market size.

The most conspicuous linguistic strategy used is the adoption of numerical terms, which are employed by 36 companies to highlight their scale. As manifested in Examples 10 and 11, cardinal numbers and numerical denominations are employed to signify the companies’ large number of employees, massive amount of assets, revenues, profitability, worldwide distribution of operations and business, and substantial global market share, respectively.

Example 10: China Minmetals

The company had managed RMB 2.16 trillion of assets, including RMB 929.5 billion in total assets.

Example 11: Haier Group:

……, and nearly 240,000 sales networks around the globe, it has gone deep into 160 countries and regions globally, serving more than 1 billion users’ families.

Step 2: branding the companies’ position and status

Endorsement is exploited as a major discursive strategy to reinforce the companies’ position. ‘Fortune Global 500’ (as shown in Example 12) is mentioned by 35 companies. As the “Fortune Global 500’ (FG500) is a prestigious ranking of the world’s strongest and most powerful companies, the mention of the FG500 endorses the companies’ high international position and power.

Ordinal numbers are employed as another linguistic strategy. In Example 12, the ordinals mark the companies’ exact position and indicate the companies’ competitive status among worldwide enterprises.

Example 12: China South Group CO., Ltd

……, ranking NO.1 in national defense industry, listed in the Fortune Global 500 enterprises in the world, ranking 275th position.

Step 3: branding the companies’ strength in research and innovation

The companies’ innovation capability is substantiated by connoting abundant ‘Research and Development’ (R&D) bases and a large amount of investment in R&D, which is realized by the adoption of numbers (Example 13). In addition, companies’ innovative human resources are constructed by lexical and phrasal resources bearing ‘knowledgeable,’ ‘skilled,’ and ‘expertize’ connotations such as ‘academic degree,’ ‘bachelor,’ ‘experts,’ and ‘key talents’ (Example 14).

Example 13: CRRC Corporation Limited

R&D investment was EUR1.408 billion, ranking at 96 among the world’s top 2500R&D investors.

Example 14: Beijing Automative Group Co., Ltd……nearly 4000, of whom have the academic degree or above bachelor, including experts in national, provincial or municipal Key Talents Programs……

Step 4: branding companies’ strength in manufacturing

The companies’ strength in manufacturing is constructed by the use of cardinal numbers, denominators, and gradable resources. Example 15 shows that numbers and denominators are deployed to signify the company’s massive production scale, while the gradable resources represent the company’s top ranking in production capability.

Example 15: Jinchuan Group Co, Ltd

Annually we are capable of producing 200,000 tons of nickel, 1 million tons of copper, 10,000 tons of cobalt, 6000 kg of platinum group metals, 30 tons of gold……

We are the third largest nickel producer, and fourth largest cobalt producer in the world, while our copper production ranks the fourth place, and platinum group metals the first in China.

The analysis shows that the adoption of the aforementioned numerical terms highlights the companies’ scale, status, and strength. Although numbers give a sense of statistical evidence, the numerical terms employed by no means provide a balanced description. A company has a variety of statistical recordings. However, only the numbers highlighting the company’s scale, status, and strength are exploited in this step.

Move 4: Describing and branding the companies’ industries

Step 1: branding the companies’ industries as being transformational, high-tech, high-end and innovative

In this step, 38 companies are promoted as developing high-tech and high-end industries through the strategic use of verbs or nominalized verbs related to the semantic meaning of ‘change for the better.’ The verbs such as ‘transform,’ ‘transformation,’ ‘upgrade,’ ‘restructure,’ ‘restructuring,’ ‘develop,’ ‘development,’ ‘adjust,’ ‘optimize,’ ‘expand,’ and ‘strengthen’ construe the companies’ action to alleviate the industries from the traditional types to high-tech, high-end, and intelligent industries. This is manifested in Example 16.

Example 16: Gree Electric Appliances, Inc. of Zhuhai

…… adjusts and optimizes industrial layout, pushes the upgrade of intelligent manufacturing for high-quality development.

In addition, high-tech and innovation-related terms are employed by 32 companies to construct the high-end and innovative nature of their industries. Terms characterized by Industry 4.0, such as big-data, cloud computation, AI technologies, intelligent connection technologies, innovation-driven, internet of things, artificial intelligence, smart industries, digitization, networking intellectualization, cloudification, intelligent manufacturing, and cloud manufacturing, are widely exploited to construct the companies’ development of high-tech, high-end, and smart industries. This is shown in Example 17.

Example 17: China Aerospace Science and Technology

……, and putting emphasis on new-generation information technology innovation, involving cloud computing, big data, Internet of Things, and artificial intelligence…

Step2: branding the position and status of the companies’ industries

Maximizers and superlatives are employed by 30 companies to construe the companies’ leading position and power in the respective industries. The maximizers are represented by ‘world-class,’ ‘leading,’ ‘No.1,’ ‘world-leading,’ ‘world’s first-class’ and ‘leader’ while the superlatives are represented by ‘the largest,’ ‘the strongest’ and ‘the most powerful’. This is manifested in Example 18.

Example 18: China South Industries Group Co., Ltd.

……, and it is internationally leading in the field of ultra high voltage transformer technology.

Step3: branding the comprehensiveness and independence of the companies’ industries

Multi-nominals are employed by 28 companies to praise the companies’ engagement in each ‘fragmentation’ of the entire global value chain, which is manifested in Example 19. ‘Multi-nominal’ is defined as the particular expression that a sequence of words or phrases belonging to the same grammatical category has some semantic relationship (Bhatia, 1993). This pattern of expression can strengthen the communicative intention by effectively making the statement all-inclusive and precise. The multi-nominal patterns construe the company’s complete industry chain, ranging from R&D, design, manufacture, distribution, to service. This constructs the critical competence, independence, and comprehensiveness of the companies’ industries.

Example 19: Zhejiang Geely Group

Geely Holding Group has transformed into a global innovative technology group engaged in the design, R&D, production, sales, and service of vehicles, powertrains, and key components, as well as mobility services, digital technology, financial services.

Move 5: Describing and branding the companies’ products

The position, quality, variety, and recognition of the company’s products are branded using several discursive strategies. First and foremost, besides directly claiming the products as high-tech, high-end, and high-quality in a few instances, the endorsement is artfully deployed to connote this competitive attribute. Example 20 shows that ‘Hongqi L series has been chosen as the official car for China’s major celebrations and events’ endorses the ‘high-tech,’ ‘high-end,’ and ‘high-quality’ of this brand of products.

Example 20: China Faw Group

Hongqi L series has been chosen as the official car for China’s major celebrations and events, highlighting the charm of oriental luxury sedan.

In addition, reference to the authority’s authentication is deployed as another discursive strategy to construct the premium quality of the products. In Example 21, the exclusive quality of the product is constructed by referring to the authentication of ‘China National Institute of Standardization’ and ‘China Quality Award,’ respectively.

Example 21: Gree Electric Appliances, Inc. of Zhuhai

According to the statistics released by China National Institute of standardization, Gree’s customer satisfaction and loyalty in the past 8 years remained No.1 in the air conditioning industry since 2011. In 2018, Gree won the China Quality Award.

Apart from these, high-tech terms are exploited to construct cutting-edge technology and sophistication in the products. Example 22 shows that the products are associated with ‘high-tech’ terms in the auto industry, such as ‘new energy vehicles,’ ‘intelligent technologies,’ and ‘smart driving,’ which indicate the ‘cutting-edge technology’ and ‘high-end’ of the products.

Example 22: SAIC Motor

…… actively promoting the commercialization of new energy vehicles and connected cars, exploring the research and industrialization of intelligent technologies such as smart driving.

Besides directly claiming that the products have the widest variety, multi-nominals are employed to indicate ‘the full range of products.’ Example 23 shows that multi-nominals are used to list out the products of a particular field. The strategic use of multi-nominals gives credit to the company’s claim.

Example 23: The commercial vehicles (trucks and buses) cover a full range of series including medium-duty, heavy-duty, light-duty, mini trucks and special-purposed versions.

The recognition and popularity of the products are formulated using statistics. This is shown in Example 24. The underlined figures construct a sense of a fact that shows the exact number of countries in which the products are sold. This suggests worldwide recognition of the products.

Example 24: Ansteel Group

The products of Ansteel are sold to more than 60 countries and regions. It has 26 overseas companies and organizations and more than 500 domestic and international customers and partners.

Move 6: Constructing the companies as responsible corporate citizens

This move occurs in five company profiles. The companies unanimously emphasize their philanthropic activities in poverty alleviation, which is one of the appeals of the government. In addition, two of the companies also show their financial support for education. This is manifested in Example 25.

Example 25: Geely Holding Group

In 2016, Geely launched its “Timely Rain” targeted poverty alleviation campaign which has seen Geely invest more than 600 million RMB in poverty alleviation through industrial, educational, employment, and agricultural means, helping lift more than 30,000 families out of poverty in over 20 areas across 10 provinces within China.

Move 7: Introducing and branding the companies’ development strategies and aspirations

In this move, the companies’ development strategies and aspirations are positively constructed.

Step 1: introducing and branding the companies’ development strategies

Although different companies communicate distinct development strategies, they frequently share similarities in the use of lexical and phrasal resources. Words such as ‘innovation,’ ‘technology,’ ‘international,’ and ‘sustainable’ are repeatedly used by 28 companies to construe their development strategies. This indicates that the companies share ‘high-tech,’ ‘high-end,’ ‘international,’ and ‘sustainable’ development strategies apart from their distinct strategies. This is manifested in Example 26.

Example 26

SAIC Motor will keep pace with technological progress, market evolution, and industry changes while accelerating its innovative development strategy in the fields of electricity, intelligent networking, sharing, and internationalization.

Step 2: introducing and branding the companies’ aspirations

The companies’ aspirations are communicated as becoming one of the most robust and influential conglomerates. This is mainly realized by using maximizers and superlatives. The maximizers, such as ‘world-class’, ‘world first-class,’ ‘leading,’ and ‘premium,’ are used by 29 companies to construe their aspirations (as shown in Example 27). In a few instances, superlatives are employed to highlight the companies’ aspirations.

Example 27: China Minmetals Corporation

Striving to play the role of a state-owned capital investment company in the field of metals and minerals so as to making unremitting efforts to build a world-class metals and minerals corporation

The companies’ aspirations are constructed ingeniously. The discursive strategy of altruism is exploited to win the international community’s positive perception towards the companies’ aspirations. The companies are constructed as contributors and benefactors to the international community. In Example 28, Huawei is constructed as bringing benefits to organizations and people in all aspects of life. This legitimizes and glorifies the companies’ objectives and aspirations because the aspiration to be a world-class company is justified as taking the lead to benefit humankind rather than as a symbol of wild ambition or a threat to competitors.

Example 28: Huawei

We will drive ubiquitous connectivity and promote equal access to networks, bring cloud and artificial intelligence to all four corners of the earth to provide superior computing power where you need it, when you need it, build digital platforms to help all industries and organizations become more agile, efficient, and dynamic, redefine user experience with AI, making it more personalized for people in all aspects of their life, whether……

The strategic choreography of rhetorical strategies constructs the distinctive attributes of the companies manifested by the moves and steps. These distinctive attributes are leveraged to mark up the companies and propel them to be more prominent than their counterparts. The combination of these sparkling attributes formulates the corporate brand portfolio of FG500CMCs, which resembles a conceptual connector associating the international community’s sense-making of the companies with the constructed positive aspects. The corporate brand portfolio also acts like a symbolic corporate umbrella, shading the companies from attacks and risks in a challenging economic climate.

Discussion

After a grounded analysis of language use in this genre, it is found that the brand identities of the FG500CMCs are projected by intentional organization of moves, tactical exploitation of rhetorical strategies, and strategic use of lexico-grammatical features.

Among the seven moves identified in this genre, Move 6 is an occasional move, Move 1, Move 3, Move 4, Move 5, and Move 7 are obligatory moves. Move 2 is an optional move, which functions to build an obedient and close relationship with the government. This can be accounted for by the fact that most of the FG500CMCs are state-owned enterprises. On the one hand, as a bureaucratic business organization, the company needs to show its obedience to the central government. On the other hand, the company needs to establish rapport with the government to gain official assets and support (Luo et al., 2010).

Each of the five obligatory moves highlights a particular set of attributes indicating the strengths, competitiveness, and superiority of the companies. These brand concepts are constructed by intentionally employing discursive strategies, including deploying graduation resources, appropriating numerical resources, adopting high-end and high-tech-related terms, and exploiting endorsement, authentication, and altruism. With the functions of the obligatory moves and discursive strategies, the brand identities of the FG500CMCs are constructed as large-scale, world-class positions, competitive in manufacturing and innovation, with a leading position in a respective industry, having a complete industry chain with ‘high-tech’ and ‘high-end’ operations, possessing a full range of ‘high-end,’ ‘high-tech,’ and ‘high-quality’ products, with a promising future of world leaders in respective industries, and contributors as well as benefactors of the international community.

While some moves may be realized through two or more different steps, other moves may only be expressed in one general functional-semantic way (Biber et al., 2007). It is found that some steps occur in Move 3, Move 4, and Move 7, while no steps appear in the other four moves. The steps of a move primarily function to achieve the functional theme of the move to which they belong (Swales, 1990). On the one hand, the steps grouped together substantiate the communicative purpose of Move 3, Move 4, and Move 7, respectively. On the other hand, since steps highlight the variability among elements in a move (Bhatia, 1993), the steps underscore the various elements of the positive attributes construed in the three moves: the companies’ scale, status, strength, high-tech, high-end, and high-status industries, innovative, independent, and comprehensive industries, development strategies, and aspirations. These various elements are combined to project the sharp competitive distinctiveness of the brand identities of the FG500CMCs.

As the primary communicative purposes of a genre are determined by its obligatory moves (Bhatia, 1993, 2004; Swales, 1990), this genre primarily serves to construct the corporate brand of the FG500CMCs discursively. This is because each of the five obligatory moves focuses on the projection of the companies’ competence, competitiveness, superiority, and power in a particular aspect. Although Move 2 serves to build a rapport with the government and Move 6 functions to construct the companies as responsible corporate citizens, the low frequency of occurrence of the two moves can only reflect the minor communicative purposes of the FG500CMCs’ company profiles.

The findings of this research show that the FG500CMCs, in particular, underscore the discursive construction of the companies’ competitiveness, superiority, and power. The linguistic features and content of texts are influenced by the socio-economic, political, and cultural context in which they are embedded (Alkaff and McLellan, 2018; Alkaff et al., 2021; Fairclough, 1993; Kress, 2004). The emphasis on the discursive construction of these aspects can be justified by the contextual factors that China has been striving to move up the global value chain (Grimes and Du, 2013), build the most influential global conglomerates (Wübbeke et al., 2016), and improve its economic leadership status globally (Shen and Chan, 2018).

The findings of the constructed brand identities are moderately consistent with Connolly-Ahern and Broadway’s (2007) highlight that competence was the most frequently used impression management strategy on corporate websites of Fortune 500 companies. It also, to some extent, corresponds with Park et al. (2013) finding that ‘superiority,’ ‘admirable,’ ‘competent,’ and ‘futuristic’ are the most frequent fantasy types constructed in ‘About Us’ of Fortune 500 companies’ websites. Distinctive from Connolly-Ahern and Broadway’s (2007), Park et al. (2013) as well as most of the other previous studies, which were conducted through a content analysis within the disciplinary area of management or communication, this study, from a different angle, provides a grounded and insightful discursive analysis.

Fairclough (1993) states that professional practices are discursively shaped and enacted. How the desired brand identities of the FG500CMCs are discursively constructed manifests the companies’ professional practice of corporate branding. In other words, the professional practice of corporate branding also requires linguistic strategies. Therefore, the investigation into the discursive construction of corporate brand identities provides a set of tangible linguistic directives and guidance on corporate branding.

Conclusion

This article explores how the corporate brand identities of the FG500CMCs are discursively constructed through company profiles on corporate websites. It is found that the company profiles primarily function to discursively construct the corporate brand identities of the FG500CMCs, apart from introducing the companies. The discursive branding of the companies is realized through the strategic organization of moves, purposeful employment of discursive strategies, and effective use of lexico-grammatical features.

Besides analyzing the lexico-grammatical features and discursive strategies, this article also investigates how the FG500CMCs’ particular attributes and strengths are covertly conveyed through the strategic organization and distribution of the moves. This provides a more comprehensive explication and thus gives new insights into the body of knowledge on the discursive construction of corporate branding. Through grounded elaboration on the tactful use of language and covert arrangement of the moves, this article also sheds light on the content design of ‘company profile’ for shaping stakeholders’ and the public’s perception of the corporate brand.

Further studies in this regard can use interviews and surveys to elicit insiders’ narratives on the procedures of the construction of company profiles for corporate branding, which will give another comprehensive perspective on understanding the discursive construction of corporate brands. In addition, as visual resources also play a crucial role in portraying organizations’ brand images (Cheng and Suen, 2014), future studies are expected to explore how multimodal strategies are exploited in the construction of the desired corporate brand identities.

Data availability

All data analyzed in this study are retrieved from the official websites of Fortune Global 500 Chinese manufacturing companies (FG500CMCs), which are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The FG500CMCs are listed out in the supplementary file. The websites of the companies are disclosed to the public, and any person can access the corporate webpages of the FG500CMCs

References

Aaker JL (1997) Dimensions of brand personality. J Mark Res 34(3):347–356

Aaker JL (1999) The malleable self: the role of self expression in persuasion. J Mark Res 36(1):45–57

Aaker JL, Benet-Martinez V, Garolera J (2001) Consumption symbols as carriers of culture: a study of Japanese and Spanish brand personality constructs. J Pers Soc Psychol 81(3):492–508

Agozie DQ, Nat M (2022) Do communication content functions drive engagement among interest group audiences? An analysis of organizational communication on Twitter. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 9:467

Alkaff SNH, McLellan J (2018) ‘Stranger in the dark’: a comparative analysis of the reporting of rape cases against minors in Malay and English newspapers in Brunei and Malaysia. Gema Online J. Lang. Stud 18(3):17–34

Alkaff SNH, McLellan J, Noorashid N (2021) A comparative media discourse investigation of hard news texts in English and Malay language newspapers in Brunei: the role of culture and language. In: Hannah MY, David D (eds) Engaging modern Brunei. Springer, Singapore, pp. 21–33

Bravo R, De Chernatony L, Matute J et al. (2013) Projecting banks’ identities through corporate websites: A comparative analysis of Spain and the United Kingdom. J Brand Manag 20(7):533–557

Albert S, Whetten D (1985) Organizational identity. Res Organ Behav 7:263–295

Balmer JM, Gray ER (2003) Corporate Brands: what are they? What of them? Eur J Mark 37(7/8):972–997

Balmer JM (2012) Corporate brand management imperatives: custodianship, credibility, and calibration. Calif Manage Rev 54:6–33

Becker-Blease JR, Kaen FR, Etebari A et al. (2010) Employees, firm size and profitability of US manufacturing industries. Invest Manag Financial Innov 7(2):7–23

Bhatia VK (1993) Analysing genre: language use in professional settings. Longman, London

Bhatia VK (2004) Worlds of written discourse: a genre-based view. Continnum International, London

Biber D, Connor U, Upton T (2007) Discourse on the move: Using corpus analysis to describe discourse structure. John Benjamins Publishing

Bondi M (2016) The future in reports: prediction, commitment and legitimization in corporate social responsibility. Pragmat. Soc 7(1):57–81

Breeze R (2012) Legitimation in corporate discourse: oil corporations after Deepwater Horizon. Discourse Soc 23(1):3–18

Brei V, Böhm S (2014) ‘1L= 10L for Africa’: corporate social responsibility and the transformation of bottled water into a ‘consumer activist’commodity. Discourse Soc 25(1):3–31

Casañ-Pitarch R (2015) The genre ‘about us’: a case study of banks’ corporate webpages. Int J Lang Stud 9(2):69–96

Chen A, Eriksson G (2019) The making of healthy and moral snacks: a multimodal critical discourse analysis of corporate storytelling. Discourse Context Media 32:100347. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcm.2019.100347

Cheng W, Suen AO (2014) Multimodal analysis of hotel homepages: a comparison of hotel websites across different star categories. Asian ESP J 10(1):5–33

Cheng W, Ho J (2016) A corpus study of bank financial analyst reports: Semantic fields and metaphors. Int J Bus Commun 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/2329488415572790

Cheong, C. Y. M. (2013). A multi-dimensional genre analysis of tourism homepages and web-mediated advertorials. Dissertation, Universiti Malaya

Chow UT (2017) A genre-based study of unlabelled advertorials and advertisements on products related to cardiovascular diseases. Dissertation, Universiti Malaya

Connolly-Ahern C, Broadway SC (2007) The importance of appearing competent: An analysis of corporate impression management strategies on the World Wide Web. Public Relat Rev 33(3):343–345

Davies G, Chun R, da Silva RV et al. (2001) The personification metaphor as a measurement approach for corporate reputation. Corp Reput Rev 4(2):113–127

De Fina A (2010a) Discourse and identity. In: Van Dijk TA (ed.) Discourse Studies: A Multidisciplinary Introduction. SAGE, London, pp. 263–282

Dutton JE, Dukerich JM, Harquail CV (1994) Organizational images and member identification. Admin Sci Quart 39(2):239–263

Esrock SL, Leichty GB (2000) Organization of corporate web pages: publics and functions. Public Relat Rev 26(3):327–344

Fairclough N (1993) Critical discourse analysis and the marketization of public discourse: the universities. Discourse Soc 4(2):133–168

Fuoli M (2012) Assessing social responsibility: a quantitative analysis of appraisal in BP’s and IKEA’s social reports. Discourse Commun 6(1):55–81

Fuoli M (2017) Building a trustworthy corporate identity: a corpus-based analysis of stance in annual and corporate social responsibility reports. Appl Linguist 39(6):846–885

Grimes S, Du D (2013) Foreign and indigenous innovation in China: Some evidence from Shanghai. Eur Plan Stud 21(9):1357–1373

Harris F, deChernatony L (2001) Corporate branding and corporate brand performance. Eur J Marketing 35(3/4):441–456

Hatch MJ, Schults M (2001) Are the strategic stars aligned for your corporate brand? Harv Bus Rev 79(2):128–134

Herzog H (1963) Behavioral science concepts for analyzing the consumer. In: Bliss P (Ed) Marketing and the Behavioral Sciences. Allyn and Bacon Inc, Boston, p 76–86

Hwang JS, McMillan SJ, Lee G (2003) Corporate web sites as advertising: an analysis of function, audience and message strategy. J Interact Mark 3(2):10–23

Ingenhoff D, Fuhrer T (2010) Positioning and differentiation by using brand personality attributes: Do mission and vision statements contribute to building a unique corporate identity? Corp Commun 15(1):83–101

Interbrand (2017). Best Global Brands Report 2017. Best Global Brands-2017 (Interbrand) | Ranking the Brands Accessed 16 Feb 2022

Interbrand (2018). Best Global Brands Report 2018. Best Global Brands-2018 (Interbrand) | Ranking the Brands Accessed 16 Feb 2022

Interbrand (2019). Best Global Brands Report 2019. Best Global Brands-2019 (Interbrand) | Ranking the Brands Accessed 16 Feb 2022

Interbrand (2020). Best Global Brands Report 2020. Best Global Brands-2020 (Interbrand) | Ranking the Brands Accessed 16 Feb 2022

Interbrand (2021). Best Global Brands Report 2021. Best Global Brands-2021 (Interbrand) | Ranking the Brands Accessed 16 Feb 2022

Jonsen K, Point S, Kelan EK et al. (2021) Diversity and inclusion branding: a five-country comparison of corporate websites. Int J Hum Resour Manag 32(3):616–649. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2018.1496125

Keller KL (2001) Building customer-based brand equity: A blueprint for creating strong brands. J Market Manag 10:15–19

Keller KL (2009) Building strong brands in a modern marketing communications environment. J. Mark. Commun 15(2):139–155

Kent M, Taylor M, White W (2003) The relationship between web site design and organization responsiveness to stakeholders. Public Relat Rev 29:63–77

Koller V (2008) Corporate brands as socio-cognitive representations. In: Kristiansen G, Dirven R (ed.) Cognitive Sociolinguistics: language variation, cultural models, social systems. Mouton de Gruyter, Berlin, pp. 389–418

Koller V (2009) Brand images: Multimodal metaphor in corporate branding messages. In: Forceville and Urios-Aparisi (eds). Multimodal Metaphor. Mouton de Gruyter, Berlin, pp. 45–71

Kotler P (1988) Marketing management: analysis, planning and control. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ

Kotler P (1989) From mass marketing to mass customization. Plann Rev 17(5):10–47

Kress G (2004) Socio-linguistic development and the mature language user: Different voices for different occasions. In: Language and Learning. Routledge. pp. 143–158

Kristina D, Hashima N, Hariharan H (2017) A genre analysis of promotional texts in an Indonesian batik industry. Indones J Appl Linguistics 7(2):425–435

Lam C (2009) The essence of ‘About Us’ page with 12 captivating showcases. www.onextrapixel.com. Accessed 21 Nov 2021

Leitch S, Davenport S (2011) Corporate identity as an enabler and constraint on the pursuit of corporate objectives. Eur J Marketing 45(9):1501–1520

Liu M, Wu D (2015) Discursive construction of corporate identity on the web: a glocalization perspective. Intercult Commun Stud 24(1):50–65

Lischinsky A (2017) Critical discourse studies and branding. In: Flowerdew J, Richardson JE (eds.) The Routledge handbook of critical discourse studies. Routledge, London and New York, pp. 549–552

Luo Y, Xue Q, Han B (2010) How emerging market governments promote outward FDI: Experience from China. J World Bus 45(1):68–79

Machin D, Thornborrow J (2003) Branding and discourse: the case of Cosmopolitan. Discourse Soc 14(4):453–471

Markwick N, Fill C (1997) Towards a framework for managing corporate identity. Eur J Marketing 31(5/6):396–409

Martin JR, White PRR (2005) Language of evaluation: appraisal in English. Palgrave Macmillan, New York

Morrish L, Sauntson H (2013) ‘Business-facing motors for economic development’: an APPRAISAL analysis of visions and values in the marketised UK university. Crit Discourse Stud 10(1):61–80

Mumby DK (2014) Organizing beyond organization: branding, discourse, and communicative capitalism. Keynote paper presented to the 11th International Conference on Organization Discourse. University of Cardiff, Cardiff

Nandan S (2005) An exploration of the brand identity–brand image linkage: a communications perspective. J Brand Manag 12(4):264–278

Opoku R, Abratt R, Pitt L (2006) Communicating brand personality: are the websites doing the talking for the top South African business schools? J Brand Manag 14(1):20–39

PAD Research Group (2016) Not so ‘innocent’after all? Exploring corporate identity construction online. Discourse Commun 10(3):291–313

Park J, Lee H, Hong H (2013) The analysis of self-presentation of fortune 500 corporations in corporate web sites. Bus Soc 55(5):706–737

Peacock M (2002) Communicative moves in the discussion section of research articles. System 30(4):479–497

Sandelowski M (2001) Real qualitative researchers do notcount: the use of numbers in qualitative research. Res Nurs Health 24:230–240

Shen S, Chan W (2018) A comparative study of the Belt and Road Initiative and the Marshall plan. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 4(1):1–11

Stutzer R, Rinscheid A, Oliveira TD et al. (2021) Black coal, thin ice: the discursive legitimisation of Australian coal in the age of climate change. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 8(1):1–9

Suen OY (2013) Hotel websites as corporate communication. Dissertation, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University

Suvatjis JY, de Chernatony L (2005) Corporate identity modelling: A review and presentation of a new multi-dimensional model. J Market Manag 21(7/8):809–834

Swales JM (1990) Genre analysis-English in academic and research settings. Cambridge University Press

Swales JM (2004) Research genres: Explorations and applications. Cambridge University Press

Tenca E (2018) Remediating corporate communication through the web: the case of About Us sections in companies’ global websites. Esp Today 6(1):84–106

Wübbeke J, Meissner M, Zenglei MJ et al. (2016) Made in China 2025. Mercator Institute for China Studies. Papers on China, 2. https://merics.org/en/report/made-china-2025

Wu YQ, Cheong CYM (2020) An appraisal analysis of the introduction section of Chinese Universities’ websites. JLC 7(2):645–669

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

1. DL has conceived the presented idea. She has collected data, performed data analysis, and drafted the manuscript. She has done the major and minor revisions. 2. UT’cC has been involved in data analysis and done a section of major revision.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

No informed consent for this paper was needed. This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, D., Chow, U.T. Discursive strategies in the branding of Fortune Global 500 Chinese manufacturing companies. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10, 347 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01849-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01849-x