Abstract

Livestreaming commerce has become a shopping option following the outbreak of COVID-19, and many sellers have adopted livestreaming marketing to increase their sales and market share. Although livestreaming marketing offers many opportunities, sellers face the challenge of identifying an effective product demonstration format to attract more viewers and increase engagement behaviors during livestreaming sessions. Based on social capital and signaling theories, this study evaluates the relationships among social capital acquisition, social endorsement, and consumer engagement constructs across three different livestreaming marketing product demonstration formats. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) multivariate analysis shows that social capital acquisition and endorsement positively affect consumer engagement across all livestreaming formats. A cross-case assessment based on Henseler’s bootstrap-based multigroup analysis reveals that although the preference for the interview livestreaming marketing format is lower, it is more efficient in attracting consumer engagement than the tutorial and behind-the-scenes livestreaming marketing formats. This study is thus the first in the scientific literature to examine consumer engagement’s antecedents across different livestreaming marketing formats.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Traditional offline shopping transactions were interrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns, which caused many sellers to migrate their operations to livestreaming, especially in China (Cohen, 2021). Livestreaming marketing is an emerging electronic commerce (e-commerce) model in which sellers present their products and services using live videos on livestreaming platforms (Chen et al., 2022). Online video streaming typically involves a live product demonstration session hosted by a seller on a social media or marketing platform; it also provides an avenue for clarifying any product ambiguity that the audience (consumers) may have. Livestreaming marketing has increased sales volumes on several e-commerce platforms, especially in China. Taobao, a major player in e-commerce, recorded $6 billion in sales through livestreaming marketing during its 2020 annual Singles-Day Global Shopping Festival (Daedal Research, 2021). Alibaba’s research unit (AliResearch) estimated China’s livestreaming market reached $308 billion (a 384% growth from 2019) in 2022 (Daedal Research, 2021). The subjectively lower prices of goods and services on livestreaming marketing platforms increase consumer engagement (Addo et al., 2021). Sellers can boost their market share and increase their sales by adopting a suitable livestreaming format to promote their products or services (Bous, 2019b). Consumers’ engagement with traditional online shopping platforms is mediated by chatbots that use artificial intelligence to interact and assist users with web services through text (Adam et al., 2020; Cheng and Jiang, 2022). However, these interactions lack the face-to-face elements consumers perceive in brick-and-mortar stores. Livestreaming marketing has increased social presence in e-commerce by introducing real-time reciprocal communication, which has also created a gap between offline and online marketing (Addo et al., 2021).

Studies have examined livestreaming in social media and gaming contexts outside digital marketing (Hilvert-Bruce et al., 2018; Lim et al., 2012; Payne et al., 2017; Wang and Li, 2020). Researchers have also investigated the motivations for consumers’ participation in livestreaming marketing on social media platforms (Addo et al., 2021; Bründl and Hess, 2016; Cai and Wohn, 2019). Some studies have examined the application of livestreaming in business-to-consumer e-commerce from a psychological perspective (Ho and Rajadurai, 2020; Sun et al., 2019; Wongkitrungrueng and Assarut, 2020). Hou et al. (2021) studied firms’ selection of online influencers for livestreaming sessions, which is based on influencers’ characteristics.

However, the livestreaming marketing literature lacks any investigation into the different formats adopted by streamers. Before starting a livestreaming session to sell products, sellers plan their presentation thereof by adopting a suitable livestreaming format that will effectively increase their real-time engagement with consumers (Stewart, 2017). Live product presentation enables consumers to perceive more accurate and rich product information, increasing their perception and providing better diagnostics of product quality (Stewart, 2017; Zhang, 2023). Therefore, investigating the extent of consumer engagement in different live product presentation formats is critical for brands aiming to adopt livestreaming marketing efficiently. According to Bous (2019a), there are three main livestreaming marketing formats: the interview format (sellers invite and interview key opinion leaders about their experience with the focal products), the tutorial format (sellers showcase the applications for their products), and the behind-the-scenes format (sellers introduce the inside story or production process of the focal products to viewers). Based on social capital and signaling theory, this study investigates sellers’ motivations for choosing a livestreaming format for product demonstration. Specifically, we conduct comparative analysis of these three livestreaming formats by examining the varied effects of social capital acquisition and social endorsement on consumer engagement across all three of them.

The study is structured as follows: an outline of the theoretical background is presented in the next section, followed by a description of our research method. We then present our findings and discuss the theoretical and practical implications of the study.

Theoretical background

Social capital theory

Social capital theory elucidates the relationships among social norms, groups, trust, and networks through which individuals’ desired goals are attained (Grootaert et al., 2004). Lacking a unified definition, social capital theory nevertheless primarily focuses on the significance of social ties and benefits (Adler and Kwon, 2002; Kwon and Adler, 2014; Neves and Fonseca, 2015). These concepts are intangible resources, entrenched and procured through specific social structures steered by relational norms of social trust, interaction, and voluntarism (Mathwick et al., 2008). Studies have focused on different determinants of social capital acquisition in the online gaming context and have posited that the gaming community is suitable for social capital acquisition (Bründl and Hess, 2016; Reer and Krämer, 2014; Törhönen et al., 2020). Studies have also proven the importance of social interaction in the livestreaming community, of an inclusive examination of social capital, and of the tendency of such research to yield a deeper understanding of its determining factors (Dux, 2018; Gros et al., 2017; Hilvert-Bruce et al., 2018; Hou et al., 2020). Previous studies have examined the underlying factors of acquiring social capital in the online gaming community (Reer and Krämer, 2014; Trepte et al., 2012). Trepte et al. (2012), from a psychological perspective, specified three factors (physical proximity, social proximity, and familiarity) in social capital formation. Reer and Krämer (2014) included self-disclosure as a salient factor of social capital acquisition. Finally, Küper and Krämer (2021) added parasocial interaction as an underlying factor of social capital acquisition to represent the feeling of interaction and relationship building in livestreaming.

This study adopts all five (physical proximity, social proximity, familiarity, parasocial interaction, and self-disclosure) factors of social capital acquisition in livestreaming marketing to better represent seller significance. Research has confirmed the association of sales promotion with the relationship between sellers and consumers in livestreaming e-commerce (Xu et al., 2022). Sellers integrate consumer participation in interaction and sales relationships by marketing their products through livestreaming (Xu et al., 2022). These relationships are their primary source of social capital, which affects consumers’ trust and engagement with sellers during livestreaming marketing (Nahapiet and Ghoshal, 1998). According to Nahapiet and Ghoshal (1998), social capital subsumes the structural links created by individuals’ social interactions, collective knowledge exchanges, and emotional relationships. This study, therefore, suggests that acquiring social capital embodies the feeling of relationship building to determine social endorsement and consumer engagement in livestreaming marketing. The focal context delineates physical proximity with the live sessions started by sellers to attract viewers interested in their displayed products while fostering bridging and bonding through their availability and accessibility. According to Skoric and Kwan (2011), relationships based in online communities develop strong social ties after a face-to-face meeting. Social proximity refers to a seller’s ability to build an atmosphere that increases viewer participation during livestreaming. High social proximity attracts increased viewer interaction through chat participation (Küper and Krämer, 2021). Familiarity refers to a seller’s ability to enhance interaction frequency by accumulating “regulars” during livestreaming. Regulars are viewers who spend more time in the chatbox of a streaming window and are characterized by their regular participation behaviors during livestreaming sessions (Hamilton et al., 2014); this regular participation promotes trust between these viewers and a seller. Parasocial interaction refers to sellers’ capacity to engage in a two-sided interaction with viewers through interpersonal involvement. Parasocial interaction explains the interpersonal processes and feelings of connectedness via media exposure (Hamilton et al., 2014). Kowert and Daniel (2021) have posited the reconstruction of the parasocial relationship from a one-sided relationship to a one-and-a-half-sided relationship with potential communication reciprocity. However, Scheibe et al. (2016) argued that the interactions between actors and viewers in livestreaming are neither social nor parasocial relationships. Instead, they are interactions located halfway between social and parasocial relationships. This study defines livestreaming-mediated interaction as parasocial interaction characterized by temporal proximity and reciprocity. A parasocial interaction, contrary to a parasocial relationship, is a mutual awareness that can only occur during a livestreaming session (Cummins and Cui, 2014; Dibble et al., 2016). It is a conversational give-and-take that unfolds during livestreaming and becomes increasingly proficient as a seller physically addresses consumers (Dibble et al., 2016). Finally, the self-disclosure factor refers to a seller’s ability to promote rapport among livestream viewers through frequent communication. Several studies have confirmed the association of self-disclosure with bridging and bonding social capital (Burke et al., 2011; Ko and Kuo, 2009; Reer and Krämer, 2014; Valenzuela et al., 2009).

Social endorsement

Signaling theory explains the theoretical background of social endorsement. This theory assumes that physical or behavioral attitudes are signals that exert some sort of influence on the behavior of others (Dunham, 2011; Smith and Harper, 2003). Signals carry an individual’s negative or positive conscious indications (Dunham, 2011), which have varied impacts on others (Fischer and Reuber, 2017). In marketing-related studies, a favorable warranty policy signals an unobserved product quality (Dawar and Sarvary, 1997) and brand credibility (Dunham, 2011). Similarly, branded products signal a higher quality rate than unbranded products (Rao et al., 1999). In online shopping, star ratings indicate the level of product value or perceived risk. A five-star rating indicates high product value, whereas a one-star rating indicates perceived product risk (Mudambi and Schuff, 2010; Zhu and Zhang, 2010). Similarly, positive reviews suggest higher purchase volume and trust in a product (Park et al., 2014).

Online social network users express emotions and display attitudes through interactions with emojis (for instance, likes, love, anger) and by using the features (for example, view, follow, unfollow, comment) available on social networking sites (Dijkmans et al., 2015; Phua and Ahn, 2014). These features and emojis can represent positive and negative attitudes, and brands consider the accumulation of positive attitudes endorsement (Thai and Wang, 2020).

In the context of livestreaming, this study suggests that the “follow” phenomenon on livestreaming commerce platforms represents social endorsement, which may have various effects. Viewers of a livestreaming marketing session can decide to follow a streamer by clicking the “follow” feature on the platform to express their interest in the demonstrated product and to be notified of later live sessions hosted by the same streamer. On social networks, following a brand/seller and clicking the “like” button during an online social interaction are support activities that contribute to brand/seller success. Support activities are expressions of endorsement and indications of support in social groups (Kim, 2020; Thai and Wang, 2020). During livestreaming sessions, new followers are indicated by a pop-up message in the chatbox, which is visible to all viewers and thus serves as an influence cue for other consumers to follow the seller (Addo et al., 2021). Therefore, these new followers of the focal seller become microcelebrities who endorse this seller and act as value cocreators for him or her during livestreaming marketing sessions (Thai and Wang, 2020). Therefore, follower endorsement represents a focal aspect of social endorsement.

The total number of viewers during a livestreaming marketing session is automatically indicated on the livestreaming window; thus, it is visible to all users browsing the livestreaming platform. Users join a session based on their interest in demonstrated products. A high viewership indicates a social consensus regarding the demonstrated product and the endorsed credibility of the seller, signaling perceived value to other users.

Therefore, this study conceptualizes social endorsement as subsuming follower and viewer endorsement based on signaling theory. Follower endorsement refers to the number of followers a seller accumulates during a livestreaming marketing session. Viewer endorsement also refers to the volume of viewers a seller can attract and retain throughout a livestreaming marketing session. Social endorsement reflects the probable value cocreated for endorsed sellers through followership and viewership. This study investigates the signals of consumers’ social endorsement behaviors and the consequences thereof during livestreaming marketing sessions.

Livestreaming marketing formats

The livestreaming ecosystem aims to enhance interactions between buyers and sellers. Buyers (viewers) can ask questions or leave comments. Sellers (livestreaming hosts) can address buyers’ questions and offer comprehensive information about products or services during live sessions. The objective driving sellers’ adoption of livestreaming marketing is to expand their market share by reaching more consumers, promoting two-way interaction, reducing product ambiguity, and increasing consumer participation (Addo et al., 2021). They host livestreaming sessions to interact with existing and potential consumers and demonstrate their products or services. However, sellers must determine which live demonstration format is more suitable to meeting their objectives (Hou et al., 2021). Livestreaming marketing formats refer to the varied ways in which sellers can humanize their products (social capital), invite viewers to be part of their live session (social endorsement), and foster engagement (consumer engagement) (Bous, 2019b). To increase consumer engagement, sellers adopt a livestreaming marketing format with a higher tendency to influence the audience on personal and emotional levels through the accumulation of social endorsement and acquisition of social capital (Bous, 2019b). Some popular formats have emerged, each with its distinct strengths; sellers connect with consumers through interview, tutorial, and behind-the-scenes livestreaming marketing formats (Bous, 2019a).

Interview livestreaming marketing involves a live product demonstration where sellers invite key opinion leaders or critical opinion consumers and interview them about their experience with the focal product(s) (Gillin, 2008). Sellers use interview livestreaming to sell products and services, entertain and educate their audience, or create specific impressions about their products or services. The decision to adopt the interview livestreaming marketing format is motivated by the desire to invite actual consumers into conversations, increase endorsement behaviors, and promote essential consumer engagement (Marshall et al., 2008).

Tutorial livestreaming marketing entails a live presentation of products where a seller demonstrates a product’s application. This livestreaming format shows the audience how to apply the focal product and sometimes offers suggestions for combining it with other products, opening cross-selling opportunities (Anand et al., 2018). Through tutorial livestreaming, sellers show actual products or service applications, causing high effectivity among the audience and increasing consumer engagement through impulse buying (Cong et al., 2021; Mitchell, 2021). This study suggests that a seller’s choice of tutorial livestreaming marketing format depends on his or her ability to acquire social capital, effectively increase followership and viewership (social endorsement) and foster viewers’ positive attitude and engagement.

Behind-the-scenes livestreaming marketing is a livestreaming format seller harness when the need to connect with their viewers arises. This format involves a live demonstration of a product’s inside story or production and packaging processes (Bous, 2019a). The format plays to people’s curiosity and provides a rewarding experience for viewers (Chen et al., 2020). It also helps build loyalty and an image among a specifically targeted segment. For example, an ethical fashion retailer might broadcast its sustainable supply chain to environmentally and socially conscious consumers during a livestreaming session. Thus, it increases consumer trust and promotes positive opinions about its products. The marketing goals of sellers during this livestreaming format are to attract more consumers, build confidence, attain consumer loyalty, and increase sales performance (Addo et al., 2021). This study thus evaluates how the behind-the-scenes livestreaming marketing format contributes to consumer engagement through acquired social capital and social endorsement.

Social capital and consumer engagement

Sellers play a vital role in demonstrating products, highlighting aspects and responding to queries from consumers as the central point of communication in a livestreaming marketing session (Hu and Chaudhry, 2020). Sellers and consumers might never actually know each other. However, sellers’ interactive communication strength during livestreaming sessions is the primary link by which they create a virtual relationship with consumers. The social capital that sellers acquire during a livestreaming session is fundamental to consumer trust (Xu et al., 2022). Nahapiet and Ghoshal (1998) have confirmed that social capital with shared functions, frequent interactions, and interdependence has a tendency toward collective development.

As Doorn et al. (2010) have defined it, consumer engagement is a brand-related, behavioral manifestation of consumers beyond mere purchase, resulting from motivational drivers. Consumer engagement in e-commerce has been described as the level of consumer interactions and established connections with the offerings and activities of a firm (Vivek et al., 2012). Zhang and Benyoucef (2016) have reported how several studies on social commerce have investigated the impact of social networking sites on consumer purchase and post-purchase behaviors, which also influences the prepurchase stage of potential consumers.

This study defines consumer engagement as consumers’ observable behaviors (like-click, chats, and click-through purchase) during a livestreaming session. It compares the differences in consumer engagement behaviors caused by acquired social capital during the interview, tutorial, and behind-the-scenes livestreaming formats. In livestreaming marketing, consumers interact with a seller by watching live product demonstrations, chatting among themselves or with the seller, purchasing click-throughs, and like-clicking. The social capital sellers acquire can quickly establish a trusting relationship that initiates consumer interactions (Nusenu et al., 2019; Xu et al., 2022). Based on the above discussions, we hypothesize the following:

H1a: Acquired social capital has a positive influence on consumer engagement.

H1b: The effect of social capital on consumer engagement differs according to livestreaming format.

Social capital and social endorsement

Bourdieu and Wacquant (1992) referred to social capital as the aggregate of actual or virtual resources acquired through durable networks characterized by standardized shared acquaintance and recognition relationships. These relationships present helpful information and new standpoints to network members (Pan et al., 2018). According to Wang et al. (2021), consumers participate in social endorsement due to an embedded social relationship; thus, sellers’ passion for accruing social capital influences their social endorsement within a network.

This study suggests that social capital triggers consumers to participate in social endorsement during livestreaming. Additionally, it compares the variations in their extent of participation in social endorsement, caused by social capital, during the interview, tutorial, and behind-the-scenes livestreaming formats. Previous studies have examined the link between endorsement and sellers’ value on social media (Jun and Yi, 2020; Schouten et al., 2019). Jun and Yi (2020) found that social media endorsements improve brand communication with consumers and promote brand loyalty. Schouten et al. (2019) posited that endorsement characteristics influence consumers’ attitudes toward ads and brands and their purchase intention. Therefore, this study hypothesizes that acquired social capital positively affects social endorsement during livestreaming marketing sessions; however, its influence differs according to the adopted livestreaming marketing format. Thus, we hypothesize the following:

H2a: Acquired social capital has a positive influence on social endorsement.

H2b: The effects of social capital on social endorsement differ according to livestreaming format.

Social endorsement and consumer engagement

According to Duan et al. (2008), people make decisions based on two premises: first, on their knowledge, personal judgments, and preferences; second, on the findings of others. People tend to favor and imitate their social group (Tausch et al., 1982) to maintain social relationships and positive self-concepts (Bond et al., 2016). Studies have confirmed that personal endorsements via observed interactions positively encourage user engagement (Oh et al., 2017; Shao and Ross, 2015; Wallace et al., 2014). A higher volume of positive brand-related consumer reactions improves credibility and creates social consensus (Sundar and Nass, 2001). Therefore, when users observe the volume of viewership and followers of a seller hosting a livestreaming session, they may decide to engage with that seller.

Follower and viewer endorsements reflect shared concerns with and attitudes toward a seller (Swani et al., 2013). Viewing livestreaming marketing sessions and following sellers during these sessions are personal and social endorsements performed by consumers interested in their demonstrated products. These activities affect continuous engagement through increased chats and like-clicks from viewers during live sessions. Thus, livestreaming sessions with high social endorsement foster observable engagement behaviors (such as clicks, click-through purchase, and chats). Consequently, this study posits that an increase in viewers and followers produces stronger signals regarding sellers’ value and product desirability. These signals are more likely to enhance the behaviors of consumers during livestreaming sessions. However, the enhancement of behavioral attitudes caused by social endorsement differs according to adopted demonstration format. Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

H3a: Social endorsement has a positive effect on consumer engagement.

H3b: The effect of social endorsement on consumer engagement differs according to livestreaming format.

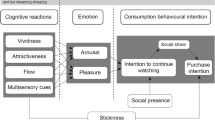

Figure 1 summarizes the hypothesized relationships in each livestreaming marketing format.

Research methodology

Data and sample

The study sample comprised sellers sell products on Amazon Live. We sent a hyperlinked survey questionnaire to these sellers’ email addresses as well as direct social media messages to their accounts, acquiring their usernames from their livestreaming profiles on the e-commerce platform. The aim was to understand these sellers’ attitudes toward consumers, perceptions of consumer engagement, and motives for choosing a particular livestreaming marketing format (Chrysochou, 2017). Before collecting data, we followed approximately 1000 different streamers on Amazon Live and randomly viewed several of their livestreaming sessions. Respondents were required to state their Amazon Live screenname to help us identify those who had responded among the sellers we followed. Data collection lasted approximately four months, from January 2022 to May 2022. The survey questionnaire had two sections: Section A focused on demographic variables, and Section B focused on constructs. Respondents were asked to answer questions on how long they have been using livestreaming marketing (to measure experience), how often they go live (to measure frequency), and what types of products they sell during their livestreaming sessions (to measure product type). We asked respondents to choose the livestreaming format that best described their presence on Amazon Live. In contrast to China, livestreaming remains a novel business model in other parts of the world. Therefore, we added an explanatory note for each format. Participation in the survey was strictly voluntary.

In preparing the data, we first exported all the responses to the questionnaire from Google Docs to Microsoft Excel. We then grouped the survey questions into three categories (cases) according to those who chose the interview, tutorial, or behind-the-scenes format to describe their presence on Amazon Live. Seven hundred and sixty-six responses were received. Respondents provided complete data with no missing values, as they clearly understood the questionnaire instrument. Additionally, a pilot study was conducted with 15 sellers on the livestreaming e-commerce platform to identify missing data sources and perform any necessary adjustments. The pilot study confirmed that the instrument was easy to complete, thereby permitting the beginning of data collection. Among the seven hundred sixty-six responses collected, 37.7%, 34.5%, and 27.8% of sellers used the tutorial, behind-the-scenes, and interview livestreaming format, respectively. Sellers who responded to the questionnaires specialized in the sales of tech products (25.6%), beauty products (20.5%), baby products (9.1%), apparel (34.1%), medical products (3.8%), or other products (6.9%) on Amazon Live. Most respondents had been using livestreaming marketing for 2–3 years (27.9%), and most of them indicated they “go live” to sell products at least once a week (64.2%). Table 1 shows the demographic details of the sample.

Measurement

We evaluated the main variables as first-order reflective constructs with several reflective indicators adapted from previous studies to complement the livestreaming marketing context. The indicators were measured with a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = “strongly disagree” to 7 = “strongly agree.” The employed measurement scales were also adapted from validated scales in previous studies.

Independent variables

Construct measurement items were adapted from published studies and combined with livestreaming marketing characteristics. Sellers’ ability to ensure physical proximity, social proximity, familiarity, parasocial interaction, and self-disclosure during livestreaming sessions (Küper and Krämer, 2021; Lang, 2021) was used to measure the social capital acquisition construct. In livestreaming marketing sessions, the virtual presence of sellers reduces product ambiguity, improves social ties, enables frequent communication tendencies, fosters emotional connectedness, and facilitates a sense of belongingness among viewers.

The measurement items for social endorsement were adapted from Thai and Wang (2020). Prevailing situations in livestreaming marketing show that consumers browsing livestreaming platforms join a live session hosted by a seller to demonstrate their interest in the focal product. A viewer may follow a seller’s account to receive upcoming live session notifications. Viewing and following live sessions send signals of endorsement to sellers and their products. Therefore, this study measures social endorsement with observable behaviors (viewer attraction, viewer retention, viewer exposure time, viewer conversion to follower rate, and follower retention rate) among consumers during livestreaming marketing sessions.

Dependent variable

The item scales for measuring consumer engagement behavior were adapted from Vivek et al. (2014). In livestreaming marketing, viewers’ confidence in sellers (resulting from sellers’ acquired social capital and endorsement) leads to observable behaviors (such as likes, click-through purchase, and chats) (Thai and Wang, 2020). Consumer engagement was measured with increased likes, frequency of like-clicks, chatbox participation rate, frequency of chat participation, and click-through purchase.

Data analysis and results

The research model was evaluated via partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). The SEM method was used because it is a more suitable application for new advances in marketing and has greater statistical power than traditional multiple regression methods (Martínez-López et al., 2013). Studies have confirmed PLS-SEM to be more practical for SEM in applied research, particularly in cases with limited participation and skewed data distribution (Henseler et al., 2009; Malhotra et al., 2010; Wong, 2010). We compared the interview (case 1), tutorial (case 2), and behind-the-scenes (case 3) livestreaming marketing formats using cross-case analysis (Khan and VanWynsberghe, 2008). The rationale for using cross-case analysis was to explore the differences and similarities across livestreaming formats and conduct an in-depth exploration of these formats to develop a comprehensive understanding of the livestreaming marketing phenomenon.

Measurement model

Confirmatory tetrad analysis of the outer model produced at least one tetrad for the independent variables, indicating that the bias-corrected and Bonferroni-adjusted confidence intervals included zero (the tetra is close to zero). Thus, a reflective measurement model was selected (Wong, 2019). We established the reliability and validity of the latent constructs to evaluate the measurement model. All construct indicator loadings exceeded 0.7 with substantial t-statistics values (t-statistics > 1.96, p < 0.05), denoting the adequacy of convergent validity for all indicators (Gefen, 2005). An indicator reliability test was conducted to assess the reliability of constructs and their indicators (with values much larger than the 0.4 minimum acceptable level and close to the 0.7 preferred level). Table 2 presents the results of the factor loadings and indicator reliability.

The results of composite reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE) tests indicate good (exceeding 0.7 and 0.5, respectively) construct reliability (Fornell and Larcker, 1981; Gefen, 2005). We further employed the rho_A coefficient to test the reliability of PLS construct scores; these results show composite reliability via values >0.7 and <1 (Wong, 2019). Table 3 presents the results of the internal consistency assessment.

We adopted the classical approach proposed by Fornell and Larcker (1981) to assess discriminant validity. This approach suggests that the square root values of AVE in each latent variable must be higher than other correlation values among the latent constructs to confirm discriminant validity. As shown in Table 4, the results indicate that the square roots of the AVEs in the latent variable constructs are higher than the correlations between the constructs, thus establishing discriminant validity.

Collinearity assessment

We conducted collinearity assessment to investigate any potential problems and check whether any variable required deletion or merging (Wong, 2019). The scores for the latent variables were inserted in IBM SPSS for regression analysis to obtain the tolerance levels and variance inflation factor (VIF) values (Chin et al., 2003; Hair et al., 2011). According to Hair et al. (2011), threats of collinearity issues do not exist if a VIF is less than 5 (a tolerance level of 0.2 or higher). The independent variables in this study produced VIF values below 5 (the highest being 1.250) with tolerance values above 0.2 (the lowest being 0.800), indicating the absence of collinearity threats. Table 5 displays the results of the collinearity assessment.

Hypothesis testing

To test the hypotheses, we examined coefficients of determination (R2) for the structural model in case 1, case 2, and case 3 to evaluate explained variances in the endogenous latent construct (consumer engagement). The results of the structural model show R2 values of 0.881 (case 1), 0.732 (case 2), and 0.791 (case 3), indicating that the exogenous latent variables (social capital and social endorsement) explain 88.1%, 73.2%, and 79.1% of the variance in consumer engagement in cases 1–3, respectively. We also deduced that social capital explains 68.7% (R2 = 0.687), 59.8% (R2 = 0.598), and 62.9% (R2 = 0.629) of the variance in social endorsement in cases 1–3, respectively.

All proposed paths are substantial, with consistent bootstrapping tests presenting p values < 0.05. Specifically, social capital has a positive effect on consumer engagement in case 1 (c = 0.278, t-statistics = 3.368, p < 0.01; H1a supported), case 2 (c = 0.353, t-statistics = 3.543, p < 0.001; H1a supported), and case 3 (c = 0.202, t-statistics = 2.027, p < 0.05; H1a supported). Social endorsement has a positive effect on consumer engagement in case 1 (β = 0.695, t-statistics = 7.177, p < 0.001; H3a supported), case 2 (β = 0.277, t-statistics = 2.547, p < 0.05; H3a supported), and case 3 (β = 0.578, t-statistics = 5.466, p < 0.001; H3a supported). Social capital positively influences social endorsement in case 1 (a = 0.892, t-statistics = 11.400, p < 0.001; H2a supported), case 2 (a = 0.580, t-statistics = 9.482, p < 0.001; H2a supported), and case 3 (a = 0.399, t-statistics = 4.153, p < 0.001; H2a supported). Social endorsement affects consumer engagement more than social capital in cases 1 and 3.

In contrast, the effect of social capital on consumer engagement is greater (t-statistic = 3.543, p < 0.001) than that of social endorsement (t-statistic = 2.547, p value = 0.0173) in case 2. Using the consistent bootstrapping procedure, we generated t-statistics to test the inner model significance. Specifically, we defined higher subsamples from the original sample as replacements to present bootstrap standard errors and offer approximate t values for testing structural path significance (Hair et al., 2012). With a 5% significance level, the path coefficients for latent variables in the inner model were substantial for all three cases; t-statistics values were greater than 1.96 (the lowest being 2.027 and the highest being 11.400). Table 6 presents these hypothesized structural paths and their significance.

The question that thus emerged was whether the numeric differences between the case-specific path coefficients were statistically sufficient. Table 7 presents the differences (absolute values) in these three comparisons’ path coefficient estimates (case 1 vs. case 2, case 1 vs. case 3, and case 2 vs. case 3) and shows the results of cross-case comparison, based on Henseler’s bootstrap-based multigroup analysis (MGA) (Henseler et al., 2009). The analysis compared each bootstrap coefficient of one case to all the bootstrap coefficients with the same parameters in the other cases (Hair et al., 2011). The results indicate that the path estimate for the relationships between social capital and consumer engagement in case 1 is almost the same as that in case 2 (|diff| = 0.075, p-value = 0.067). Therefore, the difference between case 1 and case 2 concerning the relationship between social capital and consumer engagement is not significant. Additionally, we can assume there is no notable difference between cases 1 and 3 (|diff| = 0.076, p-value = 0.056) regarding the effects of social capital on consumer engagement across the two cases.

Conversely, the p values for the other parameter estimates of all three groups are sufficient; therefore, it can be assumed that the path coefficients for SC → CE (comparison between cases 2 and 3), SC → SE (cases 1–3), and SE → CE (cases 1–3) are different. Table 7 shows the absolute values of these differences and the p values derived from Henseler’s bootstrap-based MGA test.

As shown in Fig. 2, the impacts of social capital and social endorsement on consumer engagement vary substantially across all three cases, supporting H1b, H2b, and H3b. The direct effect of social capital on consumer engagement is more substantial in case 2, followed by cases 1 and 3. The direct impact of social endorsement on consumer engagement is more considerable in case 1, followed by cases 3 and 2. Finally, the direct effect of social capital on social endorsement is more substantial in case 1, followed by cases 2 and 3. Figure 3 illustrates the differences in the expected relational effect of social capital, social endorsement, and consumer engagement across all three cases.

Results

Based on the results, some critical aspects are highlighted in this section. First, this study posits that the motivations for selecting a specific livestreaming marketing format are the same in all three cases. However, the impacts of each format are different. The results show that increasing consumer engagement is the primary goal for format adoption; thus, acquiring social capital and endorsement during livestreaming marketing sessions, irrespective of their format, is the way to achieve this goal. This result aligns with Addo et al. (2021), who argued that consumer engagement is associated with followership in digital marketing.

Second, the results indicate that social capital and social endorsement indicate a higher variance in consumer engagement among sellers who use the interview livestreaming marketing format than those who use the tutorial and behind-the-scenes formats. In contrast to the tutorial and behind-the-scenes formats, sellers gain greater engagement during interview livestreaming marketing sessions by depending only on social capital and endorsement.

The results also show that social capital notably influences consumer engagement in all three cases, confirming the previous, partial results in the literature highlighted above (Hu and Chaudhry, 2020; Lu et al., 2018; Wongkitrungrueng and Assarut, 2020). The direct effects of social endorsement on consumer engagement are more substantial than those of social capital. This result partially aligns with Hou et al. (2021), who posited that while celebrities’ social influence might be desirable, the preference for endorsement reliability is higher. However, the strength of the effect of social capital and social endorsement on consumer engagement depends on the livestreaming marketing format selected by a seller. These results indicate that the impact of social endorsement on consumer engagement is higher for an interview and behind-the-scenes formats and lower for the tutorial format. This shows that amid the tutorial livestreaming marketing format, consumer engagement depends more on the seller’s ability to acquire social capital. This result partially refutes the findings of Hou et al. (2021).

Finally, social capital sufficiently explains the variance in social endorsement across all three cases. This result is similar to that of Xu et al. (2022), who posited that streamers’ professionalism and viewers’ parasocial interactions increase behavioral intentions. Sellers’ ability to acquire social capital, therefore, influences consumers’ social endorsement.

Discussion

This study has investigated sellers’ motivation to select a specific format for their livestreaming session. Specifically, we compared the varying impacts of social capital and social endorsement on consumer engagement in the interview, tutorial, and behind-the-scenes livestreaming marketing formats. Based on the above analysis, most sellers who participated in the study use the tutorial livestreaming marketing format (37.7%), followed by 34.5% who use the behind-the-scenes livestreaming marketing format. The fewest sellers use the interview format (27.8%).

While consumers using traditional online shopping platforms make purchase decisions based on product descriptions, livestreaming marketing consumers make purchase and engagement decisions based on an efficient live presentation of products. Therefore, the choice of livestreaming marketing format is essential, based on the investigated sample in this study. The current trend of livestreaming marketing constitutes a new channel for promoting products, boosting sales performance, and increasing consumer engagement (Hu and Deng, 2021). Previous livestreaming studies have focused on consumers’ purchase intentions (Addo et al., 2021), shopping behaviors (Xu et al., 2020), usage motivations (Cai and Wohn, 2019), and the effects of influencer marketing on sales performance (Hou et al., 2021). Such studies have also investigated intangible resources such as the social capital on entertainment-related and social media livestreaming platforms akin to Twitch and Facebook Live (Kowert and Daniel, 2021; Wongkitrungrueng and Assarut, 2020). Unlike these previous studies, this study has investigated how different livestreaming marketing formats improve practical and observable consumer engagement on a pure e-commerce livestreaming platform. Our results demonstrate that the format a seller chooses for livestreaming marketing matters. An efficient livestreaming marketing format substantially impacts social capital acquisition, social endorsement, and consumer engagement. Hence, this study has yielded several findings that contribute to theory and practice.

Implications for theory

This study contributes substantially to the livestreaming marketing literature. First, it has bridged the gap in the literature regarding the focus of livestreaming marketing research on consumers. That is, this study has evaluated the motivations for livestreaming marketing and identified the key constructs, via social capital theory and signaling theory, from the seller’s (streamer) perspective.

Second, the livestreaming marketing formats adopted by sellers are aspects of livestreaming research that have received little or no attention in previous studies. This study evaluates the varied impacts of social capital and endorsement on consumer engagement across three livestreaming marketing formats. Livestreaming marketing is still a new business model; sellers thus depend enormously on viewership to sell their products. This study has investigated three formats and the effectiveness thereof in increasing viewership and engagement. These focal livestreaming formats (interview, tutorial, and behind-the-scenes) can be explored further, especially as livestreaming marketing has become an essential digital marketing option following the coronavirus outbreak.

Although the effects of interpersonal interactions on livestreaming platforms are not new topics in the literature, the approach to these interactions (parasocial relationship) has been characterized by permanent proximity and potential, reciprocal communication (Kowert and Daniel, 2021). This study has re-examined the effect of interpersonal interaction (parasocial interaction) on a livestreaming e-commerce platform characterized by temporal proximity and reciprocity. Therefore, this study shows that the intangible resources entrenched in and procured through specific temporal social structures during livestreaming marketing sessions trigger consumer engagement.

Finally, the results show that consumer engagement in e-commerce livestreaming goes beyond purchase intention, word-of-mouth, or product review intention. The above research supports the practical and observable utility of consumer engagement dimensions (likes, frequency of like-clicks, chatbox participation rate, frequency of chat participation, and click-through purchase) on e-commerce livestreaming platforms.

Implications for practice

Consumers are arguably more engaged in audio-visual stimuli than ever. Amid the adoption of livestreaming marketing, sellers should leverage the outcomes of this study to select a livestreaming marketing format that best suits their products. This study indicates that attracting greater engagement is vital for livestreaming marketing adoption. Therefore, sellers should invest in livestreaming formats with the potential to increase social capital, boost social endorsement, and increase consumer engagement.

This study indicates that properly understanding how to acquire social capital positively affects consumers’ viewership and followership behaviors during livestreaming sessions. However, some formats are more effective than others in attracting viewership and fostering followership behaviors. Sellers should therefore leverage the outcomes of this study to improve their acquisition of social capital by adopting more compelling livestreaming formats.

Limitations and future research

Although substantial variance is explained in terms of the endogenous latent variables (social endorsement and consumer engagement) via the exogenous latent variables (social capital and social endorsement), other factors could also affect consumer engagement. For example, the gender of the seller (streamer) and the product type could affect consumer engagement. Future research should evaluate the effects of these factors on consumer engagement in the livestreaming marketing context. Moreover, given our reliance on data from a single e-commerce livestreaming platform (Amazon Live), the generalizability of the findings may be limited. A follow-up study should consider applying the model in this study to other e-commerce livestreaming platforms, for instance, Facebook Live or Instagram Live.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Adam M, Wessel M, Alexander B (2020) AI-based chatbots in customer service and their effects on user compliance. Electron Mark 35:427–445

Addo PC, Fang J, Asare AO, Kulbo NB (2021) Customer engagement and purchase intention in live-streaming digital marketing platforms. Serv Ind J 41(11–12):767–786. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2021.1905798

Adler PS, Kwon S-W (2002) Social capital: prospects for a new concept. Acad Manag Rev 27(1):40. https://doi.org/10.2307/4134367

Anand A, Dutta S, Mukherjee P (2018) Influencer marketing with fake followers. Ssrn 0–44. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3306088

Bond RM, Settle JE, Fariss CJ, Jones JJ, Fowler JH (2016) Social endorsement cues and political participation. Political Commun 34(2):261–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2016.1226223

Bourdieu P, Wacquant JDL (1992) An invitation to reflexive sociology. The University of Chicago Press

Bous V (2019a) Take your viewers behind the scenes. Restream. https://restream.io/blog/take-your-audiences-behind-the-scenes-why-and-how-to-do-it/

Bous V (2019b) Live stream interviews and Q&A sessions. Restream. https://restream.io/blog/how-to-broadcast-interviews-and-q-as-online/

Bründl S, Hess T (2016) Why do users broadcast? Examining individual motives and social capital on social live streaming platforms. PACIS 332. https://aisel.aisnet.org/pacis2016/332

Burke M, Kraut R, Marlow C (2011) Social capital on Facebook: differentiating uses and users. In: Conference on human factors in computing systems—proceedings, Association for Computing Machinery, pp. 571–580

Cai J, Wohn DY (2019) Live streaming commerce: uses and gratifications approach to understanding consumers’ motivations. In: Proceedings of the annual Hawaii international conference on system sciences. Association of Information Systems, pp. 2548–2557

Chen WK, Chen CW, Silalahi ADK (2022) Understanding consumers’ purchase intention and gift-giving in live streaming commerce: findings from SEM and fsQCA. Emerg Sci J 6(3):460–481. https://doi.org/10.28991/ESJ-2022-06-03-03

Chen Y-J, Gallego G, Gao P, Li Y (2020) Position auctions with endogenous product information: why live-streaming advertising is thriving. SSRN Electron J. https://doi.org/10.2139/SSRN.3685012

Cheng Y, Jiang H (2022) Customer–brand relationship in the era of artificial intelligence: understanding the role of chatbot marketing efforts. J Product Brand Manag 31(2):252–264. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-05-2020-2907

Chin WW, Marcelin BL, Newsted PR (2003) A partial least squares latent variable modeling approach for measuring interaction effects: results from a Monte Carlo simulation study and an electronic-mail emotion/adoption study. Inf Syst Res 14(2). https://doi.org/10.1287/ISRE.14.2.189.16018

Chrysochou P (2017) Consumer behavior research methods. In: Consumer perception of product risks and benefits. Springer International Publishing, pp. 409–428

Cohen J (2021) For the next big ecommerce trend, look down and east. The Hustle. https://thehustle.co/for-the-next-big-ecommerce-trend-look-down-and-east/

Cong Z, Liu J, Manchanda P (2021) The role of “live” in livestreaming markets: evidence using orthogonal random forest. SSRN Electron J. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3878605

Cummins RG, Cui B (2014) Reconceptualizing address in television programming: the effect of address and affective empathy on viewer experience of parasocial interaction. J Commun 64(4):723–742. https://doi.org/10.1111/JCOM.12076

Daedal Research (2021) China live streaming E-commerce market: size & forecast with impact analysis of COVID-19. Research and Markets. https://www.researchandmarkets.com/reports/5304822/china-live-streaming-e-commerce-market-size-and

Dawar N, Sarvary M (1997) The signaling impact of low introductory price on perceived quality and trial. Mark Lett 8(3):251–259. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007963128115

Dibble JL, Hartmann T, Rosaen SF (2016) Parasocial interaction and parasocial relationship: conceptual clarification and a critical assessment of measures. Hum Commun Res 42(1):21–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/hcre.12063

Dijkmans C, Kerkhof P, Beukeboom CJ (2015) A stage to engage: social media use and corporate reputation. Tour Manag 47:58–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.09.005

Doorn vanJ, Lemon KN, Mittal V, Nass S, Pick D, Pirner P, Verhoef PC (2010) Customer engagement behavior—theoretical foundations and research directions. J Service Res 13(3):253–266. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670510375599

Duan W, Gu B, Whinston AB (2008) Do online reviews matter?—An empirical investigation of panel data. Decision Support Syst 45(4):1007–1016. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.DSS.2008.04.001

Dunham B (2011) The role for signaling theory and receiver psychology in marketing. Evol Psychol Bus Sci 225–256. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-92784-6_9

Dux J (2018) Social live-streaming: Twitch.TV and uses and gratification theory social network analysis. In: International conference on computer science, engineering and applications. Academy and Industry Research Collaboration Center (AIRCC), pp. 47–61

Fischer E, Reuber R (2017) The good, the bad, and the unfamiliar: the challenges of reputation formation facing new firms. Entrep Theory Pract 31(1):53–75. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1540-6520.2007.00163.X

Fornell C, Larcker DF (1981) Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark Res 18(1):39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

Gefen D (2005) A practical guide to factorial validity using PLS-Graph: tutorial and annotated example. Commun Assoc Inf Syst 16(5):91–109. Article

Gillin P (2008) New media, new influencers and implications for the public relations profession. J New Commun Res 2(2). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/267304283_New_Media_New_Influencers_and_Implications_for_the_Public_Relations_Profession

Grootaert C, Narayan D, Nyhan Jones V, Woolcock M (2004) Measuring social capital: an integrated questionnaire. The World Bank

Gros D, Wanner B, Hackenholt A, Zawadzki P, Knautz K (2017) World of streaming. Motivation and gratification on Twitch. Lect Notes Comput Sci 10282:44–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-58559-8_5

Hair JF, Sarstedt M, Ringle CM, Mena JA (2011) An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. J Acad Mark Sci 40(3):414–433. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11747-011-0261-6

Hair JF, Sarstedt M, Ringle CM, Mena JA (2012) An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. J Acad Mark Sci 40(3):414–433. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-011-0261-6

Hamilton WA, Garretson O, Kerne A (2014) Streaming on Twitch: fostering participatory communities of play within live mixed media. In: SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing systems. Association for Computing Machinery, pp. 1315–1324

Henseler J, Ringle CM, Sinkovics RR (2009) The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. Adv Int Mark 20:277–319. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1474-7979(2009)0000020014/FULL/XML

Hilvert-Bruce Z, Neill JT, Sjöblom M, Hamari J (2018) Social motivations of live-streaming viewer engagement on Twitch. Comput Hum Behav 84(1):58–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CHB.2018.02.013

Ho R, Rajadurai KGG (2020) Live streaming meets online shopping in the connected world. In: Strategies and tools for managing connected consumers. IGI Global; Ho, Ree C. pp. 130–142

Hou F, Guan Z, Li B, Chong AYL (2020) Factors influencing people’s continuous watching intention and consumption intention in live streaming: evidence from China. Internet Res 30(1):141–163. https://doi.org/10.1108/INTR-04-2018-0177/FULL/XML

Hou J, Shen H, Xu F (2021) A model of livestream selling with online influencers. SSRN Electron J https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3896924

Hu M, Chaudhry SS (2020) Enhancing consumer engagement in e-commerce live streaming via relational bonds. Internet Res 30(3):1019–1041. https://doi.org/10.1108/INTR-03-2019-0082

Hu X, Deng Z (2021) Research on the relationship of E-commerce livestreaming and sales performance of manufacturers—an empirical study of tmall transaction information system Converter (4):310–319. https://doi.org/10.17762/converter.182

Jun S, Yi J (2020) What makes followers loyal? The role of influencer interactivity in building influencer brand equity. J Product Brand Manag 29(6):803–814. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-02-2019-2280/FULL/XML

Khan S, VanWynsberghe R (2008) View of cultivating the under-mined: cross-case analysis as knowledge mobilization. Forum 9(1):34, https://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/334/729

Kim RY (2020) The value of followers on social media. IEEE Eng Manag Rev 48(2):173–183. https://doi.org/10.1109/EMR.2020.2979973

Ko HC, Kuo FY (2009) Can blogging enhance subjective well-being through self-disclosure? Cyberpsychol Behav 12(1):75–79. https://doi.org/10.1089/CPB.2008.016

Kowert R, Daniel E (2021) The one-and-a-half sided parasocial relationship: The curious case of live streaming. Comput Hum Behav Rep 4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chbr.2021.100150

Küper A, Krämer NC (2021) Influencing factors for building social capital on live streaming websites. Entertain Comput 39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.entcom.2021.100444

Kwon SW, Adler PS (2014) Social capital: maturation of a field of research. Acad Manag 39(4):412–422. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2014.0210

Lang LD (2021) Social capital in e-commerce era: toward a deeper knowledge of its conceptualization and empirical measurement in agribusiness. South Asian J Bus Stud https://doi.org/10.1108/SAJBS-09-2021-0337

Lim S, Cha SY, Park C, Lee I, Kim J (2012) Getting closer and experiencing together: antecedents and consequences of psychological distance in social media-enhanced real-time streaming video. Comput Hum Behav 28(4):1365–1378. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CHB.2012.02.022

Lu Z, Xia H, Heo S, Wigdor D (2018) You watch, you give, and you engage: a study of live streaming practices in China. In: Conference on human factors in computing systems, 2018 April. Association for Computing Machinery, pp. 1–13

Malhotra N, Hwang H, Kim Y, Tomiuk MA, Hong S (2010) A comparative study on parameter recovery of three approaches to structural equation modeling. J Mark Res 47:699–712. https://www.academia.edu/25444712/A_comparative_study_on_parameter_recovery_of_three_approaches_to_structural_equation_modeling

Marshall R, Na W, State G, Deuskar S (2008) Endorsement theory: how consumers relate to celebrity models. J Advert Res 48(4):564–572. https://doi.org/10.2501/S0021849908080550

Martínez-López FJ, Gázquez-Abad JC, Sousa CMP (2013) Structural equation modelling in marketing and business research: critical issues and practical recommendations. Eur J Mark 47(1):115–152. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090561311285484/FULL/XML

Mathwick C, Wiertz C, De Ruyter K (2008) Social capital production in a virtual P3 community. J Consum Res 34(6):832–849. https://doi.org/10.1086/523291

Mitchell M (2021) Free ad(vice): internet influencers and disclosure regulation. RAND J Econ 52(1):3–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/1756-2171.12359

Mudambi SM, Schuff D (2010) What makes a helpful online review? A study of customer reviews on amazon.com. MIS Q 34(1):185–200. https://doi.org/10.2307/20721420

Nahapiet J, Ghoshal S (1998) Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage. Acad Manag Rev 23(2):242–266. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.1998.533225

Neves BB, Fonseca JRS (2015) Latent class models in action: bridging social capital & Internet usage. Soc Sci Res 50:15–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SSRESEARCH.2014.11.002

Nusenu AA, Xiao W, Opata CN, Darko D (2019) DEMATEL technique to assess social capital dimensions on consumer engagement effect on co-creation. Open J Bus Manag 7(2):597–615. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojbm.2019.72041

Oh C, Roumani Y, Nwankpa JK, Hu HF (2017) Beyond likes and tweets: consumer engagement behavior and movie box office in social media. Inf Manag 54(1):25–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2016.03.004

Pan X, Hou L, Liu K, Niu H (2018) Do reviews from friends and the crowd affect online consumer posting behaviour differently. Electron Commer Res Appl 29:102–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ELERAP.2018.01.007

Park DH, Lee J, Han I (2014) The effect of on-line consumer reviews on consumer purchasing intention: the moderating role of involvement. Int J Electron Commer 11(4):125–148. https://doi.org/10.2753/JEC1086-4415110405

Payne K, Keith MJ, Schuetzler RM, Giboney JS (2017) Examining the learning effects of live streaming video game instruction over Twitch. Comput Hum Behav 77:95–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CHB.2017.08.029

Phua J, Ahn SJ (2014) Explicating the ‘like’ on Facebook brand pages: The effect of intensity of Facebook use, number of overall ‘likes’, and number of friends’ ‘likes’ on consumers’ brand outcomes. J Mark Commun 22(5):544–559. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527266.2014.941000

Rao AR, Qu L, Ruekert RW (1999) Signaling unobservable product quality through a brand ally. J Mark Res 36(2):258–268. https://doi.org/10.2307/3152097

Reer F, Krämer NC (2014) Underlying factors of social capital acquisition in the context of online-gaming: comparing world of warcraft and counter-strike. Comput Hum Behav 36:179–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.03.057

Scheibe K, Fietkiewicz KJ, Stock WG (2016) Information behavior on social live streaming services. J Inf Sci Theory Pract 4(2):6–20. https://doi.org/10.1633/JISTAP.2016.4.2.1

Schouten AP, Janssen L, Verspaget M (2019) Celebrity vs. Influencer endorsements in advertising: the role of identification, credibility, and Product-Endorser fit. Int J Advert 39(2):258–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2019.1634898

Shao W, Ross M (2015) Testing a conceptual model of Facebook brand page communities. J Res Interact Mark 9(3):239–258. https://doi.org/10.1108/JRIM-05-2014-0027/FULL/XML

Skoric MM, Kwan GCE (2011) Platforms for mediated sociability and online social capital: the role of Facebook and massively multiplayer online games. Asian J Commun 21(5):467–484. https://doi.org/10.1080/01292986.2011.587014

Smith MJ, Harper D (2003) Animal signals (Issue 1). Oxford University Press

Stewart P (2017) The live-streaming handbook: how to create live video for social media on your phone and desktop. In: The live-streaming handbook, 1st edn. Routledge

Sun Y, Shao X, Li X, Guo Y, Nie K (2019) How live streaming influences purchase intentions in social commerce: an IT affordance perspective. Electron Commer Res Appl 37:100886. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.elerap.2019.100886

Sundar SS, Nass C (2001) Conceptualizing sources in online news. J Commun 51(1):52–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1460-2466.2001.TB02872.X

Swani K, Milne G, Brown BP (2013) Spreading the word through likes on Facebook: evaluating the message strategy effectiveness of Fortune 500 companies. J Res Interact Mark 7(4):269–294. https://doi.org/10.1108/JRIM-05-2013-0026/FULL/XML

Tausch N, Schmid K, Hewstone M (1982) Social psychology of intergroup relations. Annu Rev 33:1–39. https://doi.org/10.1146/ANNUREV.PS.33.020182.000245

Thai TDH, Wang T(2020) Investigating the effect of social endorsement on customer brand relationships by using statistical analysis and fuzzy set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA) Comput Hum Behav 113:106499. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106499

Törhönen M, Sjöblom M, Hassan L, Hamari J (2020) Fame and fortune, or just fun? A study on why people create content on video platforms. Internet Res 30(1):165–190. https://doi.org/10.1108/INTR-06-2018-0270/FULL/PDF

Trepte S, Reinecke L, Juechems K (2012) The social side of gaming: how playing online computer games creates online and offline social support. Comput Hum Behav 28(3):832–839. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2011.12.003

Valenzuela S, Park N, Kee KF (2009) Is there social capital in a social network site?: Facebook use and college students’ life satisfaction, trust, and participation. 1. J Comput-Mediat Commun 14(4):875–901. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1083-6101.2009.01474.X

Vivek SD, Beatty SE, Dalela V, Morgan RM (2014) A generalized multidimensional scale for measuring customer engagement. J Mark Theory Pract 22(4):401–420. https://doi.org/10.2753/MTP1069-6679220404

Vivek SD, Beatty SE, Morgan RM (2012) Customer engagement: exploring customer relationships beyond purchase. J Mark Theory Pract 20(2):122–146. https://doi.org/10.2753/MTP1069-6679200201

Wallace E, Buil I, De Chernatony L, Buil I (2014) Consumer engagement with self-expressive brands: brand love and WOM outcomes. J Product Brand Manag 23(1):33–42. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-06-2013-0326

Wang M, Li D (2020) What motivates audience comments on live streaming platforms? PLoS ONE 15(4):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0231255

Wang T, Thai TDH, Ly PTM, Chi TP (2021) Turning social endorsement into brand passion. J Bus Res 126:429–439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.01.011

Wong KK-K (2010) Handling small survey sample size and skewed dataset with partial least square path modeling. Marketing Research and Intelligence Association, pp. 20–23

Wong KK-K (2019) Mastering partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) with SmartPLS in 38 h. iUniverse

Wongkitrungrueng A, Assarut N (2020) The role of live streaming in building consumer trust and engagement with social commerce sellers. J Bus Res 117:543–556. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.08.032

Xu P, Cui BJ, Lyu B (2022) Influence of streamer’s social capital on purchase intention in live streaming e-commerce. Front Psychol 12:1–13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.748172

Xu X, Wu J-H, Li Q (2020) What drives consumer shopping behavior in live streaming commerce. J Electron Commer Res 21(3):114–167

Zhang KZK, Benyoucef M (2016) Consumer behavior in social commerce: a literature review. Decision Support Syst 86:95–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.DSS.2016.04.001

Zhang N (2023) Product presentation in the live-streaming context: The effect of consumer perceived product value and time pressure on consumer’s purchase intention. Front Psychol 14:296. https://doi.org/10.3389/FPSYG.2023.1124675/BIBTEX

Zhu F, Zhang X(Michael)(2010) Impact of online consumer reviews on sales: the moderating role of product and consumer characteristics J Mark 74(2):133–148. https://doi.org/10.1509/JM.74.2.133

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors made significant contribution to the study. IOA: Responsible for the conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing of the original draft and acquisition of funding. YJ: Took part in the investigation, and was responsible for the administration of the research, supervision, and acquisition of funding. XL: Took part in the validation and formal analysis of the data as well as reviewing and editing the original manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human subjects performed by any of the authors as the data gathered for the article were questionnaire responses willingly completed by sellers on Amazon Live concerning streaming format adoption (without providing any personal or private information). Therefore, ethical approval is not applicable in this case.

Informed consent

Questionnaires for soliciting data for this article were sent as a link through the emails and social media messaging of sellers on Amazon Live. These sellers were not required to provide personal or private information in their responses. Therefore, there are no human subjects in this article, and informed consent is not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Asante, I.O., Jiang, Y. & Luo, X. Does it matter how I stream? Comparative analysis of livestreaming marketing formats on Amazon Live. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10, 403 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01860-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01860-2