Abstract

The impact of the digital economy on carbon emissions has become a topic of contention due to the paucity of guiding theoretical and empirical research. This study presents a comprehensive causal mediation model based on an expanded structural equation model. Leveraging extensive big data analysis and data sourced from developing nations, this research aims to elucidate the precise impact of the digital economy on carbon emissions and unravel the underlying mechanism. The findings unequivocally demonstrate the pivotal role played by the digital economy in mitigating carbon emissions. Even after subjecting the conclusions to a battery of robustness and endogeneity tests, their validity remains intact. The mechanism analysis reveals that the digital economy effectively curbs carbon emissions through low-carbon technological innovation and industrial diversification. The disproportionate dominance of digital industrialization is a significant factor contributing to the emergence of the “Digital Economy Paradox”. Consequently, this paper not only introduces a novel analytical perspective that systematically comprehends the carbon impact of the digital economy but also presents fresh empirical evidence that advocates for the transformation and development of a low-carbon economy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

BP’s “2022 World Energy Statistics Review” reveals that the global energy system is currently facing the greatest challenges and uncertainties of the past five decades. The growth rate of global carbon emissions has reached a peak in the last decade, and the alignment between social demand and supply of carbon reduction measures is increasingly misaligned. Our world is currently following an unsustainable trajectory. Hence, the model of sustainable low-carbon economic development has gained unprecedented significance, and there is an urgent need for humanity to expedite the transformation of the production mode (Lin and Jia, 2020).

The digital economy symbolizes the forward trajectory of scientific and industrial advancement, holding great promise for reducing carbon footprints. Nonetheless, there remains an absence of unanimous agreement concerning the precise influence of the digital economy on carbon emissions. Numerous factors have stimulated the digital revolution: declining sensor costs, enhanced data storage capabilities, rapid advancements in advanced analytics, and faster and more affordable data transmission (Hodson, 2018). The growing utilization of digital technology in communication, entertainment, data collection and management, and daily life has resulted in an increased demand for power in computing and data centers. Globally, data centers and networks consume approximately 2% of the world’s total power, and considering the current surge in digital technology, this figure is expected to steadily increase (Hittinger and Jaramillo, 2019). In China alone, data centers consume a staggering 204.5 billion kWh of electricity, accounting for 2.72% and significantly surpassing the global average (IEA, 2020).

Another source of electricity demand is blockchain technology, which employs digital encryption networks to establish distributed ledgers of information (Howson, 2019; World Bank, 2020). This technology necessitates a substantial amount of electricity to track and verify digital transactions. Bitcoin, a digital currency supported by blockchain technology, consumes an annual electricity supply of 45.8 TWh, surpassing the energy consumption of all consumers in Nevada in 2019 (EIA, 2020). Evidence suggests that China’s bitcoin industry is projected to consume 296.59 TWh of energy in 2024, leading to approximately 130.5 million tons of carbon emissions (Jiang et al., 2021). At first glance, the digital economy appears to be closely associated with high carbon emissions. However, is this apparent relationship truly realistic?

Studies have made significant contributions in exploring the impact of the digital economy on carbon emissions. However, a common limitation is the failure to consider the broader role of the digital economy, and it is incorrect to equate the carbon emissions of digital technology with those of the digital economy.

As early as 1999, Jorgenson and Stiroh (1999) highlighted the complementary relationship between the development of the digital industry and non-digital industries. In the context of the digital economy, the scale of the digital economy cannot be solely measured by the value added of the digital industry. According to the White Paper on China’s Digital Economy Development, the digital economy is an economic system based on digital technology, encompassing both digital industrialization and industrial digitalization. Digital industrialization refers to a series of digital industries arising from the development of digital technology, while industrial digitalization empowers traditional industries with digital technology and fosters new industries and models. It drives the transformation and upgrading of traditional industries, facilitates the integration of diverse industries, and has increasingly become a crucial driving force for promoting low-carbon development in the digital economy. Information and communication technology (ICT), data centers, and cloud servers are components of digital industrialization, with industrial digitalization playing a greater role in China. Consequently, previous research failing to consider the technological spillovers of the digital industry to other sectors, the promotion of energy system upgrades, and the adjustment and optimization of economic systems has resulted in the erroneous conclusion that the digital economy leads to increased carbon emissions. Our study focuses not only on the carbon emissions associated with digital industries like blockchain or the direct emissions stemming from information and communication facilities, equipment, and services but also assesses the carbon reduction effects of the digital economy on an entire region at a higher level.

A nuanced exploration unfolds as we delve deeper into the context of developing nations, where regions with higher levels of digital economy development often exhibit elevated carbon emissions, giving rise to the enigmatic “Digital Economy Paradox” However, this phenomenon’s existence does not warrant the blanket assertion that the digital economy inherently fuels carbon emissions, nor does it immediately negate the potential for carbon mitigation within this sector. Rather, it underscores the intricate interplay of multifarious factors influencing this intricate relationship. In a bid to elucidate the intricate relationship between digital economy development and carbon emissions, this study draws upon granular data sourced from regions and counties within developing nations. The endeavor is directed towards the construction of a more comprehensive and systematic logical framework that delineates the mechanisms underlying the interplay of these two pivotal dynamics. Additionally, this research endeavors to demystify the enigmatic “Digital Economy Paradox” by delving into the nuanced factors that potentially disrupt the anticipated carbon mitigation effects within the realm of the digital economy.

This paper introduces several notable innovations. Firstly, while the literature on factors driving carbon emission reduction is comprehensive, the relationship between the digital economy and carbon emissions has not been effectively demonstrated. Our study employs county-level data from China to provide theoretical and empirical evidence of the impact of the digital economy on carbon emissions in transition economies. This serves as a significant addition to the existing literature. Furthermore, the process of digital economy development in countries worldwide commenced relatively recently. This is a key reason why existing research, which only considers the carbon emissions associated with the manufacturing, operation, and processing of digital equipment from the perspective of digital industrialization (Williams, 2011), concludes that the digital economy is “carbon-friendly”. Our paper attempts to examine the carbon impact of the digital economy through the lens of low-carbon technological innovation and industrial diversification. This provides valuable insights for a deeper understanding of the digital economy and offers lessons for promoting the construction of new national competitive advantages. Finally, the scarcity of fundamental data hinders empirical research in the field of emission reduction within the digital economy (Haidt and Allen, 2020; Lang, 2011). To address this, our paper employs big data analysis methods to construct a specific dataset at the district and county levels. By doing so, we mitigate the impact of sample selection bias on the universality and accuracy of conclusions and provide supporting evidence to enhance empirical research in related fields.

Literature review

Direct effect

An increasing body of research has been dedicated to examining the carbon impact of the digital economy, yet a consensus remains elusive. Few doubt that digital technology has brought about fundamental changes to the global economy, society, and the environment. However, given the global consensus on curbing carbon emissions to address climate change, an expanding body of literature has explored the carbon impact of digital technology.

At the micro level, Emmenegger et al. (2006) conducted an LCA to analyze Switzerland’s new mobile communication system, highlighting the substantial carbon emissions generated during transmission in mobile networks. Honée et al. (2012) also conducted case studies to evaluate the carbon footprint of data centers, revealing that more than half of the carbon footprint is attributable to PC devices.

At the meso level, some scholars have identified the considerable carbon footprint of the digital industry. The Global Enabling Sustainability Initiative (GeSI) predicts that the ICT industry’s carbon footprint will reach 1.25 gigatons (Gt) of carbon emissions by 2030, accounting for 1.97% of global emissions (Accenture Strategy, 2015). Malmodin and Lundén (2016) demonstrated that Sweden’s ICT industry’s carbon emissions reached 1.3% of the global level in 2007, with emissions peaking in 2010 due to the widespread use of tablets and smartphones.

At the macro level, Moyer and Hughes (2012) suggested that digital technology has a limited inhibitory effect on carbon emissions. While some studies have shown an inverted U-shaped relationship between digital technology and carbon emissions, the turning point in developing countries is higher than in developed countries (Higón et al., 2017). Shabani and Shahnazi (2019) investigated the relationship between energy consumption in the Iranian economic sector and the digital industry, revealing that the digital industry has a significant promoting effect on carbon emissions. Belkhir and Elmeligi (2018) evaluated the global carbon footprint of the digital industry, highlighting that its contribution to greenhouse gases will increase from 1.6% in 2017 to 14% in 2040.

These pieces of evidence may lead to the misconception that the digital economy promotes carbon emissions. This misconception stems from overlooking a crucial premise: the digital economy is not synonymous with the digital industry. The aforementioned scholars primarily focused on the direct impact of the digital industry on carbon emissions, neglecting the penetration of the digital industry into other sectors. Lange et al. (2020) noted that there is heterogeneity in the impact of digital industrialization and industrial digitalization on carbon emissions. On one hand, the production of digital devices increases electricity and energy consumption. On the other hand, digitalization can drive the transition to renewable energy sources, thereby reducing energy consumption. Importantly, the reduction in energy consumption far outweighs the direct energy consumption of digital devices. Bieser and Hilty (2018) emphasized that the impact of the digital economy on carbon emissions extends beyond changes in carbon emissions resulting from large-scale digital industry production. The development of the digital industry has reshaped the patterns of economic production and consumption, leading to changes in carbon emissions. Consequently, when calculating the scale of the digital economy, some scholars consider not only investments in the digital industry but also the spillover effects of the digital industry on other sectors. When assessing the scale of China’s digital economy, the CAICT (2020) divides it into two components: digital industrialization and industrial digitalization. Jorgenson and Stiroh (1999) differentiate the digital economy into its production and application segments, with production representing the digital industry and application denoting the integration of the digital industry into other sectors.

In summary, the digital industry itself contributes to significant carbon emissions (Nguyen et al., 2020). However, when comprehensively considering digital industrialization and industrial digitalization, the digital economy has the potential to mitigate carbon emissions. Thus, this paper presents Hypothesis 1: The digital economy can reduce carbon emissions.

Indirect effects

Low-carbon technological innovation

Under the wave of digitalization, the digital economy can facilitate the transformation of new products, novel business forms, and innovative economic models. Furthermore, it can pave the way for new avenues of development and provide feasible opportunities for the effective advancement of innovation activities across all industries. The rapid economic growth witnessed in China over the past few decades has primarily been accompanied by substantial energy consumption and pollution emissions. This is primarily attributed to the preference for a production mode that relies on the large-scale allocation of factor resources. By integrating innovation resources, the digital economy overcomes the constraints imposed by the traditional economy’s supply of production factors on innovation. It fosters the upgrading of the industrial structure and diminishes industries’ dependence on energy inputs, thereby resulting in reduced carbon emissions. The widespread adoption of big data and the Internet contributes significantly to improving enterprises’ efficiency in information collection and integration. The development of the new generation of information technology industry drives the concentration of innovative elements, such as high-level talent, high-tech enterprises, and research and development (R&D) capital.

The digital economy industry, exemplified by sectors like artificial intelligence, blockchain, and the Internet of Things, predominantly invests in knowledge and technology. It is characterized by cost-effective diffusion, escalating marginal returns, and economies of scale. These distinctive features expedite its integration with traditional industries, thereby optimizing their product structure and quality, enhancing operational efficiency, fostering low-carbon technological innovation, and facilitating structural transformation and upgrading, consequently leading to reduced carbon emissions.

Consequently, this paper puts forth Hypothesis 2: The digital economy can diminish carbon emissions by enhancing low-carbon technological innovation.

Industrial diversification

The application of digital technology initially creates a virtual space for gathering, enabling openness, sharing, penetration, and diffusion (Cui et al., 2021; Tranos et al., 2021). Further advancements in digital technology facilitate the formation of industry clusters characterized by strong interconnections or minor typological differences in spatial patterns. According to the theory of industrial agglomeration (Ning et al., 2016), when regional industries gather and enhance information transmission and technology exchange, spillover effects in terms of knowledge and technology arise, leading to reduced input costs and enhanced production efficiency. The profit growth and technology sharing resulting from industrial agglomeration allow enterprises to allocate more resources towards emission reduction and encourage the exchange of emission-reducing technologies among peers. The digital economy transcends geographical boundaries and maximizes the integration of diverse resources (Alam and Murad, 2020). Once the agglomeration level of manufacturing enterprises empowered by digital technology reaches a certain threshold, it effectively resolves the contradiction between supply and demand in social production and mitigates spatial constraints on economic activities (Ren et al., 2021). Agglomeration generates economies of scale, enhancing resource utilization efficiency and curbing excessive consumption of tangible resources in traditional industrial production (Lange et al., 2020), ultimately resulting in significant emission reductions.

Moreover, digital technology not only facilitates the geographical agglomeration of enterprises but also strengthens the connections among different industries. With the progress of digital technology, emerging digital industries driven by ICT innovation have emerged, including electronic information manufacturing, telecommunications, software and information technology services, and the internet industry. These industries have witnessed substantial growth in scale, continuously updating and iterating. Additionally, the linkages between industries lacking technical and economic cooperation are reinforced. For instance, the application of Internet of Things technology in the logistics industry enables the collection of service data that was previously difficult to quantify, thereby facilitating real-time infrastructure operation monitoring and previously challenging process adjustments. This improves the service efficiency and quality of infrastructure while fostering closer ties between the logistics and service industries due to the introduction of digital technology. As a result, industrial scale and interconnectivity are expanded, leading to reduced energy waste (Prajogo and Olhager, 2012). Furthermore, the utilization of intelligent agricultural machinery in the agricultural sector not only drives the demand for mechanical equipment manufacturing but also enhances land planting efficiency and reduces carbon emissions in agricultural production (Arouna et al., 2021). In summary, the digital economy stimulates technology sharing among similar industries, fosters industrial clusters, strengthens inter-industry linkages, and generates scale effects, ultimately contributing to carbon emission reduction.

Therefore, this paper proposes Hypothesis 3: The digital economy can reduce carbon emissions, with industrial diversification playing a mediating role.

In conclusion, the digital economy reduces carbon emissions through improvements in low-carbon technological innovation and industrial diversification. However, this assertion necessitates further empirical testing to provide detailed evidence.

Digital industrialization

In the continuum of the foregoing discourse, the digital economy delineates a composite spectrum comprising digital industrialization and industrial digitization. The former encapsulates the strategic deployment of digital technologies across heterogeneous sectors, thereby propelling the orchestrated digitalization and cognitive maturation of industrial domains. This catalytic process orchestrates the metamorphosis and contemporization of conventional industrial pursuits, with a strategic compass oriented towards the amplification of production efficiency, the strategic orchestration of resource endowments, and the augmentation of value-addition within industrial realms. Nevertheless, a salient caveat emerges as the veritable relationship between digital industrialization and profligate carbon emissions does not subscribe to a preordained linear orthodoxy. Paradoxically, an assertive viewpoint espouses that the adoption of digital industrialization is implicitly concomitant with augmented energy imperatives, a dynamic that begets resonating rebound effects culminating in consequential ecological ramifications (Jin and Yu, 2022).

In consonance with the escalating arc of our reliance on the digital episteme and its corollary service modules, the commensurate escalation of energy requisites to underpin the operability of these pervasive establishments augments conspicuously. Empirical corroboration attests to the fact that the proportionate quantum of greenhouse gas emissions ushered by the digital industrialization enclave surmounts 3.2% of the aggregate global greenhouse gas inventory, thus articulating a corollary electricity utilization metric of 3.9%. Concomitant with the ascendancy of cloud computing and the proliferation of data centers, the energy appetite has surged with alacrity from a nominal tally of 62.3 billion kilowatt-hours in the annus mirabilis of 1964 to a vertiginous crescendo of 200.7 billion kilowatt-hours in the penultimate calendar year of 2020. Concomitantly, the trajectory presages a sustained continuum, poised at a threshold of consistent annual escalation encompassing a notable 9% (Sadorsky, 2012).

Notwithstanding, an alternate polemic conveys a contrasting thesis, wherein digital industrialization potentially presages the recalibration of economic growth parameters, and by extension, unshackles ecological deterioration (Amri et al., 2019). In this intricate dialectic, a novel ontological axiom is promulgated, postulating the segregation of the digital economy into discrete taxonomies: digital industrialization and industrial digitization (Zhang and Du, 2023). In this heuristic exegesis, it is deduced that the latter embodies the dominant architectonics furnishing a resolute mandate for the mitigation of carbon emissions. Thus, within this theoretical construct, notwithstanding the ascendant echelons of digital economic ascendancy in certain loci, should the compositional tenor be inextricably tethered to digital industrialization, the consequential ecological footprint resonates in the affirmative. This trend emerges from the counterpoise engendered by the incipient curtailment of carbon emissions vis-à-vis industrial digitization, which, regrettably, manifests as an insubstantial bulwark against the carbon emissions proffered by the digital industrialization cohort. Ergo, the emergent discord transgresses the initial envisagement of the digital economy’s prognosticative capacity to attenuate carbon emissions, thereby engendering the enigma epitomized by the “Digital Economy Paradox.”

Therefore, this paper proposes Hypothesis 4: Digital industrialization may impede the carbon emission mitigation efforts of the digital economy.

Research methods

Data sources

The data sources of this paper include the following:

Firstly, scientific data were utilized to obtain information regarding carbon emissions and terrestrial vegetation carbon sequestration in 2735 counties across China. Secondly, the measurement of the digital economy relied on government work reports from various cities. Thirdly, data on the digital financial inclusion index were sourced from the Digital Finance Center of Peking University, China. Fourthly, low-carbon technological innovation data were retrieved from the IncoPat database. Lastly, control variable data were derived from the “China County Statistical Yearbook”. Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics of the data. After excluding any missing values, this study compiled a total of 19,766 observations, including unbalanced panel data on 1579 districts and counties spanning from 2004 to 2017, encompassing 30 provinces, municipalities, and autonomous regions.

Variables

Explained variable (CO2)

Based on data availability, the majority of studies are limited to obtaining carbon dioxide data only at the national, provincial, and municipal levels, lacking support for more granular micro-level data. However, advancements in satellite data have provided robust support for calculating carbon emission data at the district and county levels (Chen et al., 2022). In this study, we followed the approach of Chen et al. (2020a), which standardized the scale of satellite imagery from the Defense Meteorological Satellite Program/Operational Linescan System (DMSP/OLS) and National Polar-Orbiting Partnership/Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (NPP/VIIRS) to acquire consistent and continuous nighttime light data. To address the issue of pseudoregression, a unit root test was employed to validate the relationship between provincial carbon emissions and nighttime light data. Additionally, training was conducted to fit the data, and county-level carbon emissions and carbon sequestration data were obtained using a top-down weighted average strategy. Due to significant disparities in value between the two sets of nighttime light data, originating from different sensors, an artificial neural network was utilized to calculate the relationship between these two datasets, resulting in improved fitting accuracy.

Core explanatory variables (Digital)

The digital economy is a relatively abstract concept, posing challenges in identifying precise indicators for its measurement in practical terms. The essence of measuring the digital economy lies in capturing its core aspects. The narrow definition of the digital economy encompasses the emergence of digital core industries driven by digital technology, whereas the broader definition encompasses the overall impact of digital technology on the economic system as a whole. Therefore, the extent of digital technology adoption serves as a tangible manifestation of digital economy development. Cloud computing, artificial intelligence, big data, the Internet of Things, and blockchain technology collectively form the foundational elements of digital technology.

Previous studies have predominantly employed extensive data text analysis methodologies, quantifying the frequency of terms related to digitization in government work reports to gauge the progression of the digital economy (Chen et al., 2012; McAfee and Brynjolfsson, 2012; Farboodi et al., 2019; Smutradontri and Gadavanij, 2020)Footnote 1. However, this approach may engender multifaceted criticisms. Firstly, the frequency analysis of terms within government work reports may not directly mirror policy execution. While an abundance of digital-centric lexicon may feature in these reports, it predominantly serves as a manifestation of governmental policies, without aptly reflecting the tangible outcomes of policy implementation in practice. The effectiveness of policy enactment is predisposed to myriad factors, including local governmental capacity, resource allocation, and balance of interests. Subsequently, the contents of government reports could be influenced by factors such as political propaganda. Government work reports often serve as platforms for public dissemination of governmental endeavors, and thus, the presence of political underpinnings cannot be discounted. Against the backdrop of political exigencies, governmental emphasis on the significance of digital economic development may not necessarily correlate with factual circumstances, introducing discrepancies between the narrative presented and actual realities. Moreover, government work reports merely represent a facet of governmental endeavors, thereby possibly falling short of comprehensive coverage of the myriad dimensions underpinning digital economic growth. The trajectory of digital economy development encompasses a spectrum of dimensions, including industrial innovation, technological applications, and human resource cultivation, which government work reports might not comprehensively encompass. Consequently, employing term frequency analysis in government work reports to quantify the advancement of the digital economy necessitates judicious consideration. A holistic assessment of the digital economy mandates amalgamation of supplementary datasets and information for a comprehensive evaluation. Substantiating this premise, this study opts to measure the extent of digital economy development by appraising the quantum of digital patents within regional core digital industries. Recognizing the core of the digital economy to reside in digital technologies, digital patents aptly showcase the proficiency and resources a region commands in digital technology research and application.

Mediating variables

Low-carbon technological innovation (Li)

This study utilized the IncoPat database to quantify the number of patents from the output perspective. This database comprises over 100 million patent records from 112 countries and organizations worldwide, offering comprehensive data with frequent updates. Specifically, we extracted a total of 945,078 patent records from 250,456 Chinese companies spanning the years 2010 to 2017. These records included publication numbers, publication dates, application numbers, applicants, application dates, applicant countries, and patent types classified according to the International Patent Classification (IPC). Based on the location of the applicants in districts and counties, we analyzed the number of patents across 2659 regions in China during the aforementioned period.

Building upon this foundation, we proceeded to calculate the level of low-carbon technological innovation (Li) in the districts and counties. Extensive research has been conducted on green technology patents. The cooperative patent classification (category Y02), jointly issued by the European Patent Office and the U.S. Patent Office, defines green technology or applications as those that mitigate or adapt to climate change (Ghisetti and Quatraro, 2017). Many scholars have adopted this approach (Chen et al., 2020b). However, accurately identifying patents related to low-carbon technologies remains challenging using this definition of green technological innovation. Therefore, this study introduces a refined distinction to more precisely identify the number of patents associated with low-carbon technologies across different enterprises. Specifically, we refer to the Green Inventory of the International Patent Classification published by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) in 2010, which categorizes green patents into seven groups: transportation, waste management, energy conservation, alternative energy production, administrative regulation or design, agriculture or forestry, and nuclear power generation.

Since the seven patents above cover a wide range of innovation, the following three types of patents are extracted for this article:

-

(1)

Those with a primary classification of alternative energy production or energy conservation;

-

(2)

Those with a secondary classification of waste management for waste disposal patents; and

-

(3)

Those with a secondary classification of administrative regulation or design for carbon/emissions trading patents, which are used to measure the low-carbon technological innovation of enterprises.

Industrial diversification (Div)

In this paper, industrial diversification is used to measure the size of a region, and the following model is constructed by drawing on the measurement method of the Herfindahl–Hirschman index (Dharfizi et al., 2020):

In the formula above, sijt represents the proportion of the employment of industry j of city i in year t in the total employment of the region, and Divit represents industrial diversification. The larger the value is, the more types of industries in the region, the larger the scale, and the more balanced the development.

Control variables

Drawing on previous research (Aichele and Felbermayr, 2012; Best et al., 2020; Chang et al., 2019), this paper selected the following control variables at the county level:

-

(1)

Although the total carbon emissions of large cities are relatively high, a larger urban area also means greater economic agglomeration, and the formation of economies of scale will help reduce carbon emissions (Cheng et al., 2022). Thus, the administrative area (Area) was chosen as a control variable.

-

(2)

In recent years, China has vigorously promoted agricultural modernization and mechanization, and the synergistic effect on carbon emission reduction has initially emerged (Li et al., 2023). Therefore, the total power of agricultural machinery (Machine) was chosen as a control variable.

-

(3)

More population means more consumption, which inevitably increases carbon emissions (Yan and Huang, 2022). Thus, the registered population (Popu) was chosen as a control variable.

-

(4)

It has become an indisputable fact that developing countries respond to climate change by adjusting their industrial structure (Wang et al., 2020). Hence, the value added of the primary industry (Str) was chosen as a control variable.

-

(5)

Fiscal policy not only provides incentives for ecological protection but also strengthens restrictions on unfriendly development models (Zhang et al., 2021a). Thus, the general public budget expenditure (Budget) was chosen as a control variable.

-

(6)

Evidence suggests that the majority of carbon emissions come from manufacturing rather than personal emissions (Tu et al., 2019). Therefore, the number of industrial enterprises above a designated size (Industry) was chosen as a control variable.

Causal mediation model

In recent years, the goal of mediation analysis has garnered significant attention from economists and policymakers. Structural equation modeling (SEM) has been extensively employed in numerous studies (Alacevich and Zejcirovic, 2020; Baron and Kenny, 1986; Hanewald et al., 2021), with tens of thousands of articles utilizing this method as of 2009. SEM has made a profound impact on social science research, yet researchers have seldom considered its potential pitfalls (Zhao et al., 2010). Notably, structural equation models encounter substantial endogeneity issues, and relying solely on traditional exogeneity assumptions is insufficient to determine the causal mechanism (Celli, 2022). When mediating variables and explanatory variables interact, the estimates of average effects become biased. Since the average effect estimate disregards critical information regarding direct and indirect effects, it fails to provide a comprehensive explanation of the causal mechanism underlying the total effect (Rijnhart et al., 2021). Building upon the research of Alan et al. (2018), this study establishes a causal mediation model to discern the mediating effect of low-carbon technological innovation and industrial diversification. Specifically, the causal mediation model employs a quasi-Bayesian Monte Carlo approximation, a computer simulation-based method that allows for the inclusion of various linear, nonlinear, or even nonparametric estimation models within the framework. The model is based on the counterfactual framework to calculate the average causal mediation effect (ACME) and the average direct effect (ADE) to achieve causal inference between continuous or discrete variables, mediating variables and outcome variables. If we try to judge the impact of event A on event B, we should not only observe the impact of event A on event B but also observe the situation of event B without event A. In fact, as long as event A occurs, we cannot observe the situation of event B without event A. By using the counterfactual framework, we can not only solve the problem of selective bias but also avoid the need to make assumptions about the functional form of parameters and ensure more flexible identification steps to obtain the true causal mechanism (Nguyen et al., 2020). The model is as followsFootnote 2:

The subscripts i and t represent the district and year, respectively, and CO2 is the explained variable of this paper, that is, the carbon emissions of districts and counties. Digital is the core explanatory variable, which is represented by the development level of the digital economy of the city where the district and county are located. X represents the set of control variables that affect carbon emissions and changes in i and t. μi and μt represent individual and year fixed effects, respectively, which are used to control for individual factors that affect carbon emissions but do not change over time and time factors that do not change with individuals, respectively. ε represents the random error term.

Learning from Imai et al. (2010), this paper adopts an estimation method based on quasi-Bayesian Monte Carlo approximation. The main steps are as follows: First, Eqs. (3) and (4) are fitted to simulate the latent value of the mediating variable based on the sampling distribution of the model parameters. Second, the potential outcome is simulated based on the simulated value of the mediating variable. Finally, the causal mediating effect is calculated. The effective estimate of ACME is φ1χ2, and that of ADE is χ1.

Results

The impact of the digital economy on carbon emissions

Table 2 presents the estimation results of Eqs. (2)–(4). Regression (1) demonstrates the impact of the digital economy on carbon emissions, with the coefficient of Digital showing significant negative effects at the 1% level, confirming the direct influence of the digital economy on carbon emissions.

All control variables chosen in this study exhibit significance, further affirming the robustness of the model. Notably, the estimated coefficient of Area is positive, indicating that larger administrative areas generally promote carbon emissions. Typically, higher administrative areas correspond to lower population density. Numerous studies have revealed a negative correlation between population density and carbon emissions (Wang et al., 2022), with per capita emissions in low-density regions being 2–2.5 times higher than those in high-density areas (Grazi et al., 2008). Moreover, research has shown that carbon emissions in urban areas with high population density are 23% lower than those in rural areas (Fremstad et al., 2018; Yi et al., 2021). Hence, the findings of this paper align with previous literature.

The estimated coefficient of Machine is negative, suggesting that the total power of agricultural machinery can restrain carbon emissions. Some studies indicate that large-scale operators are more inclined to adopt advanced agricultural technology, which, despite increased power consumption, mitigates the negative impact of agricultural practices on the ecological environment (Ren et al., 2019). Moreover, cases demonstrate that the carbon emissions per unit area of large farms utilizing high-power agricultural machinery in Iran are significantly lower than those of small-scale farms (Rakotovao et al., 2017).

The estimated coefficient of Popu is positive. It is evident that a larger population corresponds to higher electricity consumption, inevitably leading to increased carbon emissions. Furthermore, the coefficient of “Str” is positive, signifying that value added in the primary industry stimulates carbon emissions. In China, adjusting the industrial structure is one approach to reducing carbon emissions. The primary industry predominantly consists of energy-intensive sectors and constitutes a major contributor to carbon emissions (Zhu et al., 2021).

The estimated coefficient of Budget is negative, suggesting that general public budget expenditure can restrain carbon emissions. In most Chinese district and county governments, economic and environmental performance are key assessment criteria. However, in the face of fiscal deficits, officials still prioritize local economic development, and China’s rapid economic growth over the decades has come at the expense of environmental pollution (Zhao and Mattauch, 2022). Governments with more substantial financial budgets are more inclined to invest in environmental development (Li et al., 2017) to fulfill superior-level government environmental assessment requirements, resulting in lower carbon emissions.

Lastly, the estimated coefficient of Industry is positive, indicating that the number of large-scale industrial enterprises promotes carbon emissions. Since 2017, the Chinese government has transitioned from a high-speed development model to one focused on high-quality development. This shift is driven by the recognition that pursuing industrial scale without considering industrial quality leads to adverse consequences, including significant environmental pollution issues (Tu et al., 2019). Consequently, one of the Chinese government’s future objectives is gradually phasing out highly polluting, high-emission, and high-output industrial enterprises while introducing high-tech enterprises with advanced technology and low pollution levels (Zhang et al., 2021b).

Robustness checks

Firstly, the objective of this paper is to validate whether the advancement of a high digital economy corresponds to reduced carbon emissions. In the realm of natural science, it is possible to establish a more dependable control group by creating an experimental environment and discerning causal relationships through comparisons between the experimental and control groups. Adhering to this notion, it is necessary to establish two identical sets of experimental and control groups. The experimental group would possess a high digital economy, while the control group would have a low digital economy. The ensuing changes in carbon emissions between the two groups can then be observed. However, finding perfectly matched control and experimental groups in all aspects proves challenging. Therefore, this paper employs propensity score matching. Specifically, districts and counties characterized by a high digital economy are designated as the experimental group, while those with a low digital economy form the control group. Utilizing the aforementioned control variables, a logit model is employed to assign scores to the two groups. Based on these scores, the experimental and control groups are paired using the K-nearest neighbor caliper radius matching method. In this instance, K is set at 4, and the caliper is set at 0.01. Consequently, the closest individual from the four candidates displaying a score difference of 1% is selected for one-to-four matching. Following the matching process, the experimental and control groups exhibit striking similarity, except for the digital economy variable. Finally, the difference in carbon emissions between the treatment and control groups is calculated, providing evidence that the high digital economy group demonstrates lower carbon emission levels.

Second, based on the previous discussion, this study unifies the satellite image scales of the DMSP/OLS and NPP/VIIRS from 1997 to 2017 and calculates the carbon sequestration (CO2seq) of terrestrial vegetation in 2735 counties in China. This variable is used to replace the previous CO2 variable for regression.

Third, this paper draws on the county-level Digital Financial Inclusion Index (Dfiic) issued by the Digital Finance Center of Peking University, China. In the data, there were 1754 counties in 2014, 1754 counties in 2015, 2791 counties in 2016, 2786 counties in 2017, 2802 counties in 2018, 2848 counties in 2019, and 2850 counties in 2020. Digital financial inclusion is calculated based on 33 indicators. We use this index to replace the digital economy level in the regression model.

In summary, the results are shown in Table 3, and the coefficients of the core explanatory variables are still significantly negative at the 1% level. Thus, the conclusions above are robust.

Endogeneity test

Endogeneity poses a crucial concern that warrants attention in this paper. While carbon dioxide, as an energy source, may not directly impact other economic behaviors, carbon emissions are frequently associated with regional economic activities. A higher carbon emission intensity signifies a greater level of economic development, which subsequently influences the adoption of the digital economy. Conversely, higher carbon emission intensity also signifies a more advanced state of the manufacturing industry, and the remarkable enhancements in manufacturing productivity are intertwined with the rapid progress of the digital economy. Simultaneously, the digital economy and the advancement of manufacturing industry technology are intricately linked. A causal endogenous relationship exists between the digital economy and manufacturing industry productivity.

To address the endogeneity issue in the carbon emissions and digital economy relationship, we employ the instrumental variable method. Considering the historical development of China’s digital economy, its origins can be traced back to the establishment of fixed telephone lines. Regions with a high level of digital economy may also exhibit high penetration rates of fixed telephone lines. Furthermore, prior to the widespread adoption of fixed telephone lines, information exchange primarily relied on the postal system, which was responsible for setting up fixed telephone lines. The distribution of post offices directly influenced the deployment of fixed telephone lines during the early stages. Regions with a greater number of post offices and fixed telephone lines often possess a more favorable foundation for digital economy development. A direct positive correlation exists between these factors and the digital economy, while their connection with carbon emissions is not significant. Therefore, the two prerequisites for instrumental variables are met.

Accordingly, this paper selects the number of fixed telephone lines per 100 people and the number of post offices per million people in 1984 as instrumental variables. However, considering that the use of one-year data as an instrumental variable will cause problems such that it will be difficult for the fixed effect model to carry out measurements, the number of fixed telephone lines per 100 people (Fixtele) and the number of post offices per million people (Post) in 1984 are multiplied by the number of Internet users per year as the instrumental variables of the digital economy. Regressions (1)–(4) of Table 4 report the regression results after using the two instrumental variables. In regression (1) and regression (3), the first-stage estimation results show that the coefficients of the instrumental variables are all significantly positive at the 1% level, which satisfies one of the preconditions for the instrumental variables, that is, being related to the digital economy. In regression (2) and regression (4), the second-stage estimation results show that the regression coefficient of the digital economy is still significantly negative at a level of at least 1%. Therefore, after excluding the endogeneity problem, the conclusions above are still valid.

Test of the mediating effect

In elucidating the operative mechanisms linking the digital economy with carbon emissions, an initial step involves estimating a causal mediation model. This research employs a quasi-Bayesian approach to approximate parameter uncertainty, with the count of simulation iterations set at 1000. The computational results derived from this model are presented in Eqs. (3) and (4). The results from Regressions (2)–(3) presented in Table 2 delineate the influence exerted by the digital economy on low-carbon technology innovation and industrial diversification. The coefficient estimates for Digital pertaining to both Li and Div exhibit significant positivity at a level of a minimum 1%, substantiating the hypothesis that the digital economy effectively augments all three mediating variables. Results from Regressions (4)–(5) encapsulate the outcomes following the incorporation of the digital economy and the two mediating variables. It is noteworthy that in these regressions, the coefficients for Digital, Li, and Div continue to display significant negativity at the 1% level, inferring that a larger mediating variable corresponds to a reduction in carbon emissions. The outcomes of the causal mediation model provide valuable insights into the potential channels through which the digital economy influences carbon emissions, a topic which is delved into further in subsequent sections of this paper.

Moreover, this study calculates the ACME, ADE, and Average Treatment Effects (ATE) by employing the coefficient product of the causal mediation model. The tabulated results are displayed in Table 5. For columns (1)–(2), the outcome variables are CO2, and the mediating variables comprise Li and Div. The ACME of the digital economy’s effect on carbon emissions via low-carbon technology innovation stands at −0.007, and its corresponding 95% confidence interval surpasses 0, attesting to the presence of a mediation effect. The ADE and ATE are −0.938 and −0.945, respectively, with confidence intervals exceeding 0, thus establishing that the proportion of the mediation effect is 0.031. In a similar vein, the other two mediation effects are confirmed, respectively, thereby underscoring the significance of the two mediation pathways.

Test of the digital economy paradox

While research has demonstrated the potential of the digital economy to reduce carbon emissions, an intriguing phenomenon persists—a conundrum we shall refer to as the “Digital Economy Paradox.” Curiously, regions characterized by elevated levels of digital economic prowess often exhibit concurrent high levels of carbon emissions. This paradox challenges the anticipated carbon mitigation benefits of robust digital economic development. In pursuit of empirical validation, the designed variable—digital industrialization—will be scrutinized to determine if its presence accentuates or attenuates the inhibitory effect of the digital economy on carbon emissions. Such analysis holds the potential to unravel the intricate dynamics underpinning the observed “Digital Economy Paradox,” providing a more nuanced understanding of how digital industrialization may potentially counteract the carbon mitigation intent embedded within the digital economy. This paper employs the summation of software business revenue and industrial value-added to gauge the magnitude of digital industrialization and introduces the variable (Din). When the magnitude exceeds the mean, Din is assigned a value of 1; conversely, it takes on a value of 0. Table 6 presents the results of the moderation effect analysis. In this table, Din_Digital signifies the interaction term between digital industrialization and the digital economy. It is discernible that the coefficient estimate for Digital remains significantly negative. However, the coefficient estimate for the interaction term is significantly positive. This finding suggests that digital industrialization exerts a dampening effect on the carbon mitigation capacity of the digital economy. Specifically, when the prevalence of digital industrialization is higher, the inhibitory effect of the digital economy on carbon emissions diminishes. This signifies that such an effect is obscured or mitigated by the pronounced prominence of digital industrialization within the digital economic landscape.

Discussion

The implications of our discoveries extend to the discourse surrounding the digital economy and carbon emissions. The digital economy can be fractionated into two segments: the digital industry and the traditional industry imbued with digital technology. The academic landscape heretofore has failed to duly recognize the distinction between the digital industry and the digital economy. Should the carbon emissions from the digital industry be utilized as a proxy for those of the digital economy, it would invariably precipitate measurement inaccuracies. Digital technology is fundamentally predicated on electricity, and burgeoning digital industries such as cloud computing and data centers necessitate increasingly energy-intensive infrastructure for their development and operations. Emblematic digital industries, typified by information services, constitute approximately 10% of global electricity generation (Yang et al., 2022). This voluminous electricity consumption intensifies the usage of coal, thereby instigating substantial carbon emissions (Salahuddin and Alam, 2015). However, it does not equate to the notion that the digital economy is inherently incompatible with carbon emissions reduction. Drawing upon the insights of Jorgenson and Stiroh (1999), our study reveals that when one considers both the digital industry and other sectors that have been enhanced by the digital industry, the net effect is a decrease in carbon emissions. Bieser and Hilty (2018) likewise posited that the evolution of the digital industry has transformed industrial production methodologies. Consequently, the reduction in carbon emissions achieved by non-digital industries will surpass that of the digital industry.

The rationale behind this is rooted in the applicability of digital technology in traditional industries. On one hand, the permeation of digital technology facilitates the translocation of production factors from offset sectors to efficient ones, which enhances resource allocation efficiency, subsequently ameliorating energy utilization efficiency and reducing carbon emissions. On the other hand, the digital economy actualizes cross-industry emissions reduction through digital technology spillovers, representing a significant conduit for digital technology to assist traditional industries in emissions reduction. Notably, the advent of smart home systems, eco-friendly hospitality establishments, and remote office systems has curtailed carbon emissions in utilities such as water supply and heating (Yadegaridehkordi et al., 2021). The integration of sensors and chips into conventional machinery, combined with the support of 5 G technology, allows enterprises to control each machine’s operation optimally and expeditiously at any given time, maintaining it in an ideal state and diminishing energy consumption (Xu and Li, 2019). This exemplifies a successful incorporation of industrial internet technology into traditional industries. Information technology significantly attenuates the carbon emission intensity of the logistics industry and curbs energy wastage during transit through strategies such as route optimization, transportation capacity allocation, and the Internet of Things (Prajogo and Olhager, 2012). When digital technology permeates the agricultural sector, it also proves beneficial in carbon emissions reduction. All these are attributable to the suppressive effect of digital technology on the carbon emissions of traditional industries (Walzberg et al., 2020), which will counterbalance the carbon emissions increment of the digital industry, ultimately inducing a decrease in the aggregate carbon emissions of the digital economy. This elucidates why prior research may have concluded that the digital economy does not contribute to carbon emissions reduction (Zhou et al., 2019).

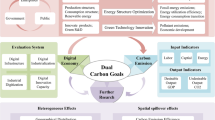

Drawing upon the aforementioned results, this paper conceptualizes a theoretical framework outlining the impact of the digital economy on carbon emissions, as depicted in Fig. 1. Specifically, concerning the direct effects, carbon emissions associated with digital technology as a fulcrum encompass both the digital industry and traditional sectors enhanced by digital technology. The coefficient delineating the impact of the digital economy on carbon emissions registers at −0.123, demonstrating a significant inhibitory influence. Pertaining to indirect effects, initially, the digital economy, distinguished by technology spillovers, propels the advancement of industrial structure, thereby steering the development of comprehensive technological innovation within a region. Low-carbon technological innovation exerts the most immediate impact on carbon emissions, with its coefficient estimated at −0.277, implying a notable inhibitory effect. Secondly, the digital economy fosters the diversified development of regional industries through the phenomena of information transmission and industrial agglomeration, culminating in a scale effect. The coefficient is estimated at 0.022, indicating an apparent stimulatory effect. Furthermore, the escalation of the industrial scale promotes inter-industry technology sharing across disparate regions, ameliorates resource allocation among analogous industries, minimizes unnecessary energy consumption, and subsequently mitigates carbon emissions.

Essentially, this occurrence underscores the nuanced role of digital industrialization in obscuring the carbon mitigation potential inherent to the digital economy. The deceptive impression that the digital economy engenders high carbon emissions is, in actuality, a manifestation of digital industrialization overshadowing the carbon reduction efficacy of the digital economy. The coefficient of this effect is estimated to be approximately 0.033. This approach not only enhances the scholarly comprehension of this paradox but also informs policy interventions that can guide regions towards harnessing the full potential of the digital economy while effectively managing its carbon emissions impact. Several factors contribute to this perplexing scenario. Firstly, the accelerated growth of the digital economy can inadvertently lead to increased energy consumption for powering data centers, electronic devices, and communication networks. Despite the efficiency gains offered by digitalization, the sheer scale of digital infrastructure deployment can result in elevated energy demands, ultimately translating to higher carbon emissions. Secondly, the transformation of traditional industries into digitally-integrated systems might entail energy-intensive processes and resource allocation, offsetting potential carbon reductions achieved through digitalization. This could be particularly pronounced in regions that prioritize rapid digital industrialization without concurrently addressing energy efficiency measures.

It is prudent to acknowledge that the research presented herein is not without its limitations. One can reasonably postulate that the evolution of the digital economy will yield a myriad of nascent industries, extending beyond the current confines of the digital industry and traditional industries that employ digital technology. Thus, in forthcoming research, this paper aims to delve deeper into the carbon reduction potential of the digital economy, shifting the lens towards a more granular perspective of individual industries or entities.

Conclusion and policy implications

Deciphering strategies to actualize a world with diminished carbon emissions has seized the attention of nations globally (Acemoglu et al., 2016). In the quest to reduce carbon emissions, the role of the digital economy has been not only overlooked but also misapprehended. Our research conducts a comprehensive examination of the direct and indirect impacts of the digital economy on carbon emissions, providing fresh insights into the pathways and mechanisms through which the digital economy reduces carbon emissions. Employing data spanning from 2004 to 2017, which encompasses 1579 districts and counties in China, this study formulates a comprehensive logical framework elucidating the interplay between the digital economy and carbon emissions. The findings reveal that the evolution of the digital economy can indeed facilitate the reduction of carbon emissions. Thus, in terms of data coordination, governmental entities ought to harness the digital economy to establish a more sophisticated data collection and oversight system to enhance the quality of environmental supervision. Further, our mechanistic analysis underscores that the influence of the digital economy on carbon emissions is significantly tethered to factors such as low-carbon technological innovation and industrial diversification, with various tests substantiating its causal impact. Ultimately, our research elucidated that digital industrialization possesses the potential to obscure the inhibitory impact of the digital economy on carbon emissions.

This investigation is intrinsically linked to the high-quality development associated with the digital economy era and furnishes several policy implications. Firstly, in spite of the considerable carbon emissions attributed to the digital economy sector itself, this industry has notably amplified its energy utilization efficiency. The implementation of the “National Computing Network to Synergize East and West” Project is a compelling testimony to how the digital economy enhances inter-regional energy allocation efficiency, propels the judicious redistribution of resources, and diminishes the overarching carbon emission levels. Governmental bodies should expedite the digital transformation of traditional industries and the erection of infrastructures, initiate grand schemes to establish substantial data centers, and set up numerous data repositories in Western China, ensuring they are effectively interconnected with those in Eastern China. It is suggested that a dynamic and differentiated digital economy strategy be adopted. Taking into account the variation in resource endowments across different regions, it would be prudent to calibrate the rate of digital economic development in each region. This will allow the digital economy to serve as a technical prop to efficaciously mitigate disparities in regional development.

Data availability

Due to confidentiality agreements and sensitive information in the dataset, the author is unable to publicly share the full data. Supplementary material is provided.

Notes

Note: See section 1 in the Appendices for specific steps.

Note: See section 2 in the Appendices for specific steps.

References

Accenture Strategy (2015) #SMARTer2030ss ICT solutions for the 21st century challenges. Global e-Sustainability Initiative (GeSI), Brussels

Acemoglu D, Akcigit U, Hanley D, Kerr W (2016) Transition to clean technology. J Political Econ 124(1):52–104

Aichele R, Felbermayr G (2012) Kyoto and the carbon footprint of nations. J Environ Econ Manag 63(3):336–354

Alacevich C, Zejcirovic D (2020) Does violence against civilians depress voter turnout? Evidence from Bosnia and Herzegovina. J Comp Econ 48(4):841–865

Alam MM, Murad MW (2020) The impacts of economic growth, trade openness and technological progress on renewable energy use in organization for economic co-operation and development countries. Renew Energy 145:382–390

Alan S, Ertac S, Mumcu I (2018) Gender stereotypes in the classroom and effects on achievement. Rev Econ Stat 100(5):876–890

Amri F, Zaied YB, Lahouel BB (2019) ICT, total factor productivity, and carbon dioxide emissions in Tunisia. Technol Forecast Soc Chang 146:212–217

Arouna A, Michler JD, Yergo WG, Saito K (2021) One size fits all? Experimental evidence on the digital delivery of personalized extension advice in Nigeria. Am J Agric Econ 103(2):596–619

Baron RM, Kenny DA (1986) The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol 51(6):1173–1182

Belkhir L, Elmeligi A (2018) Assessing ICT global emissions footprint: trends to 2040 & recommendations. J Clean Prod 177:448–463

Best R, Burke PJ, Jotzo F (2020) Carbon pricing efficacy: cross-country evidence. Environ Resour Econ 77(1):69–94

Bieser J, Hilty L (2018) Indirect effects of the digital transformation on environmental sustainability: methodological challenges in assessing the greenhouse gas abatement potential of ICT. In: ICT4S 2018 5th international conference on information and communication technology for sustainability. EPIC Series in Computing, Toronto, ON, p 68–81

CAICT (2020) White paper on China’s digital economy development. China Academy of Telecommunication Research of MIIT (CAICT), China

Celli V (2022) Causal mediation analysis in economics: objectives, assumptions, models. J Econ Surv 36(1):214–234

Chang CP, Dong M, Sui B, Chu Y (2019) Driving forces of global carbon emissions: from time- and spatial-dynamic perspectives. Econ Model 77:70–80

Chen H, Chiang RHL, Storey VC (2012) Business intelligence and analytics: from big data to big impact. MIS Q 36(4):1165–1188

Chen J, Gao M, Cheng S, Hou W, Song M, Liu X, Liu Y, Shan Y (2020a) County-level CO2 emissions and sequestration in China during 1997–2017. Sci Data 7(1):391

Chen J, Gao M, Cheng S, Xu Y, Song M, Liu Y, Hou W, Wang S (2022) Evaluation and drivers of global low-carbon economies based on satellite data. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 9(1):153

Chen S, Shi A, Wang X (2020b) Carbon emission curbing effects and influencing mechanisms of China’s emission trading scheme: the mediating roles of technique effect, composition effect and allocation effect. J Clean Prod 264:121700

Cheng L, Mi Z, Sudmant A, Coffman DM (2022) Bigger cities better climate? Results from an analysis of urban areas in China. Energy Econ 107:105872

Cui L, Hou Y, Liu Y, Zhang L (2021) Text mining to explore the influencing factors of sharing economy driven digital platforms to promote social and economic development. Inf Technol Dev 27(4):779–801

Dharfizi ADH, Ghani ABA, Islam R (2020) Evaluating Malaysia’s fuel diversification strategies 1981–2016. Energy Policy 137:111083

EIA (2020) Annual electric power industry report. Form EIA-861 detailed data files, early release data for 2019. https://www.eia.gov/electricity/data/eia861/

Emmenegger MF, Frischknecht R, Stutz M, Guggisberg M, Witschi R, Otto T (2006) Life cycle assessment of the mobile communication system UMTS: towards eco-efficient systems (12 pp). Int J Life Cycle Assess 11(4):265–276

Farboodi M, Mihet R, Philippon T, Veldkamp L (2019) Big data and firm dynamics. AEA Pap Proc 109:38–42

Fremstad A, Underwood A, Zahran S (2018) The environmental impact of sharing: household and urban economies in CO2 emissions. Ecol Econ 145:137–147

Ghisetti C, Quatraro F (2017) Green technologies and environmental productivity: a cross-sectoral analysis of direct and indirect effects in Italian regions. Ecol Econ 132:1–13

Grazi F, Van Den Bergh JCJM, Van Ommeren JN (2008) An empirical analysis of urban form, transport, and global warming. Energy J 29(4):97–122

Haidt J, Allen N (2020) Scrutinizing the effects of digital technology on mental health. Nature 578(7794):226–227

Hanewald K, Jia R, Liu Z (2021) Why is inequality higher among the old? Evidence from China. China Econ Rev 66:101592

Higón DA, Gholami R, Shirazi F (2017) ICT and environmental sustainability: a global perspective. Telemat Inform 34(4):85–95

Hittinger E, Jaramillo P (2019) Internet of things: energy boon or bane? Science 364(6438):326–328

Hodson R (2018) Digital revolution. Nature 563(7733):S131

Honée C, Hedin D, St-Laurent J, Fröling M (2012) Environmental performance of data centres—A case study of the Swedish national insurance administration. In: 2012 electronics goes green 2012+. IEEE, Berlin, Germany, p 1–6

Howson P (2019) Tackling climate change with blockchain. Nat Clim Change 9(9):644–645

IEA (2020) Energy technology perspectives 2020. OECD Publishing, Paris

Imai K, Keele L, Yamamoto T (2010) Identification, inference and sensitivity analysis for causal mediation effects. Stat Sci 25(1):51–71

Jiang S, Li Y, Lu Q, Hong Y, Guan D, Xiong Y, Wang S (2021) Policy assessments for the carbon emission flows and sustainability of Bitcoin blockchain operation in China. Nat Commun 12(1):1938

Jin X, Yu W (2022) Information and communication technology and carbon emissions in China: The rebound effect of energy intensive industry. Sustain Prod Consump 32:731–742

Jorgenson DW, Stiroh KJ (1999) Information technology and growth. Am Econ Rev 89(2):109–115

Lang T (2011) Advancing global health research through digital technology and sharing data. Science 331(6018):714–717

Lange S, Pohl J, Santarius T (2020) Digitalization and energy consumption. Does ICT reduce energy demand? Ecol Econ 176:106760

Li J, Gao M, Luo E, Wang J, Zhang X (2023) Does rural energy poverty alleviation really reduce agricultural carbon emissions? The case of China. Energy Econ 119:106576

Li Y, Shi X, Su B (2017) Economic, social and environmental impacts of fuel subsidies: a revisit of Malaysia. Energy Policy 110:51–61

Lin B, Jia Z (2020) Supply control vs. demand control: why is resource tax more effective than carbon tax in reducing emissions? Humanit Soc Sci Commun 7(1):74

Malmodin J, Lundén D (2016) The energy and carbon footprint of the ICT and E&M sector in Sweden 1990–2015 and beyond. In: Proceedings of ICT for sustainability 2016. Atlantis Press, Amsterdam, p 209–218

McAfee A, Brynjolfsson E (2012) Strategy & competition big data: the management revolution. Harv Bus Rev 90(10):60–68

Moyer JD, Hughes BB (2012) ICTs: do they contribute to increased carbon emissions? Technol Forecast Soc Change 79(5):919–931

Nguyen TT, Pham TAT, Tram HTX (2020) Role of information and communication technologies and innovation in driving carbon emissions and economic growth in selected G-20 countries. J Environ Manag 261:110162

Ning L, Wang F, Li J (2016) Urban innovation, regional externalities of foreign direct investment and industrial agglomeration: evidence from Chinese cities. Res Policy 45(4):830–843

Prajogo D, Olhager J (2012) Supply chain integration and performance: the effects of long-term relationships, information technology and sharing, and logistics integration. Int J Prod Econ 135(1):514–522

Rakotovao NH, Razafimbelo TM, Rakotosamimanana S, Randrianasolo Z, Randriamalala JR, Albrecht A (2017) Carbon footprint of smallholder farms in Central Madagascar: the integration of agroecological practices. J Clean Prod 140:1165–1175

Ren C, Liu S, Van Grinsven H, Reis S, Jin S, Liu H, Gu B (2019) The impact of farm size on agricultural sustainability. J Clean Prod 220:357–367

Ren S, Hao Y, Xu L, Wu H, Ba N (2021) Digitalization and energy: how does internet development affect China’s energy consumption? Energy Econ 98:105220

Rijnhart JJM, Valente MJ, MacKinnon DP, Twisk JWR, Heymans MW (2021) The use of traditional and causal estimators for mediation models with a binary outcome and exposure-mediator interaction. Struct Equ Model 28(3):345–355

Sadorsky P (2012) Information communication technology and electricity consumption in emerging economies. Energy Policy 48:130–136

Salahuddin M, Alam K (2015) Internet usage, electricity consumption and economic growth in Australia: a time series evidence. Telemat. Inform 32(4):862–878

Shabani ZD, Shahnazi R (2019) Energy consumption, carbon dioxide emissions, information and communications technology, and gross domestic product in Iranian economic sectors: a panel causality analysis. Energy 169:1064–1078

Smutradontri P, Gadavanij S (2020) Fandom and identity construction: an analysis of Thai fans’ engagement with Twitter. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 7(1):177

Tranos E, Kitsos T, Ortega-Argilés R (2021) Digital economy in the UK: regional productivity effects of early adoption. Reg Stud 55(12):1924–1938

Tu Z, Hu T, Shen R (2019) Evaluating public participation impact on environmental protection and ecological efficiency in China: evidence from PITI disclosure. China Econ Rev 55:111–123

Walzberg J, Dandres T, Merveille N, Cheriet M, Samson R (2020) Should we fear the rebound effect in smart homes? Renew Sustain Energy Rev 125:109798

Wang F, Sun X, Reiner DM, Wu M (2020) Changing trends of the elasticity of China’s carbon emission intensity to industry structure and energy efficiency. Energy Econ 86:104679

Wang J, Dong K, Dong X, Taghizadeh-Hesary F (2022) Assessing the digital economy and its carbon-mitigation effects: the case of China. Energy Econ 113:106198

Williams E (2011) Environmental effects of information and communications technologies. Nature 479(7373):354–358

World Bank (2020) State and trends of carbon pricing 2020. World Bank, Washington, DC

Xu X, Li J (2019) The influence of 5G mobile communication technology on the development of industry and commerce. Stud Dialectics Nat 35(8):119–123

Yadegaridehkordi E, Nilashi M, Nasir MHNBM, Momtazi S, Samad S, Supriyanto E, Ghabban F (2021) Customers segmentation in eco-friendly hotels using multi-criteria and machine learning techniques. Technol Soc 65:101528

Yan Y, Huang J (2022) The role of population agglomeration played in China’s carbon intensity: a city-level analysis. Energy Econ 114:106276

Yang Z, Gao W, Han Q, Qi L, Cui Y, Chen Y (2022) Digitalization and carbon emissions: how does digital city construction affect China’s carbon emission reduction? Sustain Cities Soc 87:104201

Yi Y, Wang Y, Li Y, Qi J (2021) Impact of urban density on carbon emissions in China. Appl Econ 53(53):6153–6165

Zhang HG, Cao T, Li H, Xu T (2021a) Dynamic measurement of news-driven information friction in China’s carbon market: theory and evidence. Energy Econ 95:104994

Zhang J, Zhang N, Bai S (2021b) Assessing the carbon emission changing for sustainability and high-quality economic development. Environ Technol Innov 22:101464

Zhang Y, Du M (2023) Greening through digitalisation? Evidence from cities in China. Reg Stud 1–15. In Press. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2023.2215824

Zhao J, Mattauch L (2022) When standards have better distributional consequences than carbon taxes. J Environ Econ Manag 116:102747

Zhao X, Lynch JG, Chen Q (2010) Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: myths and truths about mediation analysis. J Consum Res 37(2):197–206

Zhou X, Zhou D, Wang Q, Su B (2019) How information and communication technology drives carbon emissions: a sector-level analysis for China. Energy Econ 81:380–392

Zhu R, Zhao R, Sun J, Xiao L, Jiao S, Chuai X, Zhang L, Yang Q (2021) Temporospatial pattern of carbon emission efficiency of China’s energy-intensive industries and its policy implications. J Clean Prod 286:125507

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Major Program of National Fund of Philosophy and Social Science of China (CN) (grant number 18ZDA040).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HW: methodology, investigation, writing-original draft preparation. GY: conceptualization, supervision, funding acquisition, validation. ZY: data curation, software, visualization, writing-reviewing and editing, project administration.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, H., Yang, G. & Yue, Z. Breaking through ingrained beliefs: revisiting the impact of the digital economy on carbon emissions. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10, 609 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02126-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02126-7

This article is cited by

-

The Influence of Digitalization on Greenhouse Gas Emissions in European Union. The Analysis of Mediating Effect of Renewable Energy Consumption

Journal of the Knowledge Economy (2025)

-

China’s pathway to agricultural decarbonization: dissecting the nexus between rural digitalization and agricultural carbon emission efficiency

Environment, Development and Sustainability (2025)

-

What policies do the clean energy transition and green innovation tracks dictate for the MENA region’s sustainable development goals?

Clean Technologies and Environmental Policy (2025)

-

Digitalization and Climate Change Spillover Effects on Saudi Digital Economy Sustainable Economic Growth

Fudan Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences (2025)

-

Translational strategies to uncover the etiology of congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract

Pediatric Nephrology (2025)