Abstract

This study aimed to investigate whether global air pollution harms human morals beyond physiological and psychological health. To accomplish this, we conducted an original survey involving over 80,000 individuals across 30 countries, inquiring about their recent perceived unethical behaviors. Through regression analyses, we identified global evidence of a positive correlation between local monthly average concentrations of nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and perceptions of unethical behavior. This finding suggests that air pollution may potentially elicit unethical behavior through a complex response mechanism. It is noteworthy that the impact of air pollution on the inclination to perceive unethical behavior is heterogeneous across categories of unethical behavior and countries. For example, the effects of increasing air pollution concentrations vary even within the same European country: an increase in NO2 concentration in Greece and the Netherlands augments the inclination to perceive fatal unethical behaviors such as murder, terrorism, and suicide, while in Germany, NO2 concentration diminishes the inclination to perceive the same types of unethical behaviors. Overall, the societal costs of air pollution may be even more far-reaching than previously acknowledged, and further research is necessary to unveil the intricate response mechanisms underlying this issue.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In 2019, approximately 6.7 million premature deaths were caused by air pollution, making it the most significant health risk factor compared to other factors such as child and maternal malnutrition, drug and alcohol use, AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria, road injuries, and interpersonal violence (Fuller et al., 2022). Furthermore, Fuller et al. (2022) reported that the number of deaths attributed to air pollution was approximately equivalent to those caused by smoking. Existing epidemiological literature summarizes that both short- and long-term exposure to air pollution contribute to respiratory and cardiovascular diseases (Brunekreef and Holgate, 2002; Seaton et al., 1995). According to Manisalidis et al. (2020), short-term exposure to air pollutants is associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, coughing, shortness of breath, wheezing, asthma, and other respiratory diseases, leading to high hospitalization rates. Long-term effects are closely associated with chronic asthma, pulmonary dysfunction, cardiovascular disease, and cardiovascular mortality. Thus, it is widely recognized in public and ambient health contexts that exposure to air pollution is related to various diseases (Sass et al., 2017).

In addition to these well-established health effects, recent epidemiological literature suggests a potential link between air pollution and mental health (Sass et al., 2017). Previous studies on humans and animals have demonstrated that exposure to air pollution can lead to neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, cerebrovascular disorders, and neurodegenerative pathologies, which could potentially lead to psychiatric disorders such as depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation among humans (Block, Calderón-Garcidueñas, 2009; Sass et al., 2017).

Previous studies have also shown that exposure to air pollution decreases well-being and life satisfaction (Li et al., 2019; Zheng et al., 2019; Yerema and Managi, 2021; Li and Managi, 2022), increases anxiety and discomfort (Power et al., 2015; Sass et al., 2017; Lu et al., 2018), and contributes to mental disorders such as depression, schizophrenia, and autism (Pedersen et al., 2004; Volk et al., 2013; Cho et al., 2014). It has also been reported that air pollution is a significant risk factor for substance abuse, self-harm, and suicide (Yang et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2018; Szyszkowicz et al., 2018; Lu, 2020; Okuyama et al., 2022).

This study explores a novel question: Does air pollution influence human moral perceptions and behavior? While extensive research has demonstrated the detrimental effects of air pollution on physical and mental health, this study aims to extend this understanding into the realm of moral psychology. Several medical and psychological studies served as motivation to test the hypothesis. Studies on mice by Rammal et al. (2008) showed a strong positive correlation between oxidative stress and neuroinflammation with anxiety levels. Kouchaki and Desai (2015), along with Corrigan and Watson (2005), found that anxiety symptoms could elicit unethical behavior in humans, regardless of its violent nature. Li et al. (2017) further demonstrated that exposure to particulate matter significantly increases cortisol levels (the stress hormone) in the body; Lee et al. (2015) reported that cortisol levels decreased after individuals engaged in unethical behavior. The anxiety engendered by air pollution exacerbates the perception of threat and fosters selfish and unethical behavior (Kouchaki and Desai, 2015; Lu et al., 2018).

Building upon this medical and psychological research, this study seeks to contribute to the field by examining how these physical and psychological effects of air pollution may impact moral judgments and behaviors—a relatively unexplored area in environmental health research. Specifically, this study surveyed over 80,000 individuals across 30 countries using a custom-designed online questionnaire to assess their perceptions of unethical behavior across 16 types of experiences. We then analyzed the relationship between these measured individual-level perceptions of unethical behavior and air pollution, specifically monthly average nitrogen dioxide (NO2) concentrations in respondents’ residential areas, while controlling for various personal and regional characteristics. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first multinational demonstration of the impact of air pollution on unethical behavior based on individual-level data, shedding light on the potential for further research to elucidate its underlying mechanisms.

Methodology

Data acquisition

Garcia-Moreno et al., (2006) highlighted that the reported number of incidents of domestic violence considered unethical behavior may be significantly lower than the actual occurrences due to victims’ fear of retaliation from abusers if they file a complaint with the police. Furthermore, individuals may have different perceptions of what constitutes reportable behavior. Aradabiliy et al. (2011) noted that domestic violence may be considered by some as a form of family discipline despite its unethical nature. Therefore, we decided to directly inquire about individuals’ recent unethical behaviors rather than relying on reported crime statistics. Unlike studies based on city-level crime arrest data (Herrnstadt et al., 2021; Lu et al., 2018), our questionnaire-based study allows us to consider three types of unethical behaviors: (1) crimes such as prostitution, rape, child abuse, and domestic violence, which people may be hesitant to disclose; (2) acts such as theft and pilferage, which may not always result in criminal charges; and (3) acts such as racial and gender discrimination, which may not be illegal everywhere but are nonetheless malicious. As a result, our definition of unethical behavior includes a range of malicious acts beyond strictly criminal behavior. This study provides the first multinational evidence that air pollution affects not only criminal behavior but also unethical behavior.

To ensure the representativeness and completeness of the dataset, this study utilized an extensive international survey conducted by Nikkei Research, Inc., covering 89,266 respondents across 30 countries selected based on their work capacity and research budget constraints (Chapman et al., 2019). The surveyed countries included Australia, Brazil, Canada, Chile, China, Colombia, the Czech Republic, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, India, Indonesia, Italy, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, Myanmar, the Netherlands, Philippines, Poland, Romania, Russia, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Thailand, Turkey, the United States, and Vietnam. See Table A1 in the Supplementary Information for sample sizes for each country. It is important to note that samples from Canada, the Czech Republic, Poland, and Romania, which exhibit significantly lower rates of reported unethical behavior, were excluded from the empirical analysis. After filtering out respondents who chose not to answer certain relevant questions (e.g., income, criminal experience), the final sample size for analysis was refined to 48,836.

The survey was carefully designed to capture a wide range of sociodemographic variables by randomly selecting respondents to reflect the demographic characteristics of each country in terms of age and sex. To mitigate potential biases in data collection, particularly those arising from Internet-based survey methods, our approach included both online and in-person surveys. Specifically, in certain countries such as Myanmar, we utilized in-person surveys to ensure the representation of underrepresented groups in rural areas and slums. This combination of methods was crucial for capturing diverse perspectives. The survey content underwent rigorous checks for accuracy and cultural relevance and was translated and reviewed by professional translators. The survey was conducted between June 2015 and March 2017 according to the schedule noted in Table A1. To maintain the integrity and quality of the dataset, strict quality control procedures overseen by Nikkei were implemented to ensure that responses accurately reflected the specified sociodemographic categories.

The questionnaire included prompts such as, ‘Please select items that describe what has happened recently in your neighborhood or among the people around you.’ Respondents could select all 21 items that applied to them: theft/stealing, fraud, murder, terrorism, suicide, gang violence/assault, privacy violation by police/military, racial discrimination, gender discrimination, drug trafficking, ownership of gun(s)/rifle(s), abortion, prostitution, pregnancy/delivery by unmarried women, rape, bribing/corruption, child abuse, domestic violence, single parenting, homosexuality, or none of the above. Four items (abortion, pregnancy/delivery by unmarried women, single parenting, and homosexuality) were excluded from the analysis as they do not constitute unethical behaviors. It should be noted here that the term “recently” may have varied in interpretation across individuals. Its use aimed to reduce stress and elicit intuitive responses from the respondents. Following Jessup et al. (2017), our analysis assumed that the term “recently” corresponded to a period of “one month” throughout. While recognizing that this assumption may introduce bias, particularly in questionnaire-based studies, we acknowledge it as a limitation.

Figure A1 in the Supplementary Information illustrates an example question from our survey. This table presents a hypothetical scenario where respondents indicate they have experienced (1) murder, (2) fraud, or (3) gang violence/assault. In this case, respondents are guided to select the corresponding items in the table. Table 1 elucidates the extent of crime exposure among our respondents. This table categorizes the types of criminal activities encountered by participants, specifying the percentage (%) of individuals who reported each experience. The data reveal that theft is the most frequently reported crime, with 39.47% of respondents acknowledging such incidents. Other notable criminal experiences include fraud (12.50%), drug trafficking (12.29%), and murder (6.75%).

In addition to the key question listed above, the questionnaire survey also simultaneously examined the respondents’ sociodemographic variables (address, age, sex, occupation, income, education, religion). These individual-level data were utilized to control for factors that may have influenced the perceptions of unethical behavior. Socioeconomic factors are likely to influence exposure to unethical behavior, as they can shape an individual’s criteria for judging right and wrong and the frequency of exposure to unethical behavior. For example, studies have shown that women tend to be harsher on crime than men, and people become more negative about crime as they age (Borg and Hermann, 2023). In addition, a positive correlation exists between regional income inequality and individuals’ fear of crime (Clément and Piaser, 2021). Furthermore, individuals with higher levels of education are less exposed to violence against women (Sen and Bolsoy, 2017). Additionally, it is widely recognized that certain aspects of religion reduce participation in criminal activity, as indicated by a literature review by Sumter et al. (2018).

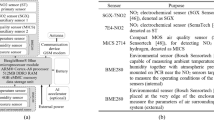

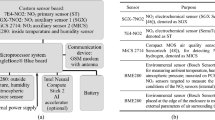

Air pollution data were obtained from measurements of vertical column concentrations of NO2 particles from the surface to the lower troposphere by the Global Ozone Monitoring Experiment (GOME-2) satellite (ESA, EUMETSAT 2000). The GOME-2 satellite measures the vertical column concentrations of NO2 in the troposphere on a daily basis through an optical process and accurately models monthly average NO2 values with a resolution of 80 × 40 km. In our study, the monthly average NO2 concentration data (molecules/cm2) obtained from the GOME-2 satellite were matched to the geographic information (ZIP code) of the survey respondents at the grid level to obtain air pollution concentration data around them. Satellite (rather than surface) observation data were utilized because the sample included several developing countries and regions that lacked adequate air pollution monitoring facilities, and it was necessary to evaluate these countries and regions in the same manner as developed countries (Yerema and Managi. 2021; Vohra et al., 2022).

The choice of NO2 as the primary air pollutant for examination in our study was guided by both practical and scientific considerations. NO2 is a prevalent urban pollutant, often used as a key indicator of air quality due to its significant health impacts and ubiquity in urban environments. This choice was further reinforced by the availability of consistent global satellite data for NO2, which was particularly crucial given our study’s extensive geographical scope, including many developing countries. These regions often lack comprehensive, ground-based monitoring systems for a variety of air pollutants, making satellite-derived NO2 data the most reliable and accessible proxy for assessing air pollution levels across different countries (Yerema and Managi, 2021). While we acknowledge that other pollutants such as SO2 and particulate matter also carry important health and behavioral implications, focusing on NO2 enabled us to conduct a more uniform and globally applicable analysis, essential for understanding the broader implications of air pollution on human moral perceptions and behaviors.

In addition to data on reported unethical behavior and air pollution concentrations, several meteorological variables were included as control variables in the empirical model. Previous studies have indicated that weather conditions (e.g., temperature, humidity, and wind speed) may influence unethical behavior (Baron and Bell, 1976; Rotton and Frey, 1985). In the present study, average wind speed, precipitation, vapor pressure, and monthly minimum and maximum temperatures for the study period in each country, collected at a 4-km resolution from the TerraClimate data set (Abatzoglou et al., 2018), were used as control variables in the model. Additionally, distance to the coast was included as a control variable because of geographic and climatic factors that could affect air quality and pollution patterns, potentially influencing the analysis of the relationship between air pollution and human moral perceptions and behavior. This methodological choice is consistent with established practices in environmental research. Controlling for variations in residential choices and local climates due to proximity to coastlines is a recognized approach, as demonstrated in studies by Banzhaf, Randall (2008), and Kalkuhl and Wenz (2020).

To address the possibility of endogenous biases, such as increased pollutant emissions from police cars dispatched during criminal events, the monthly planetary boundary layer height (PBLH) was employed as an instrumental variable in the empirical model. PBLH is known to have a negative impact on local air pollution concentrations (Schwartz et al., 2017). As such, a lower boundary layer results in higher local pollution concentrations for the same local emissions, and vice versa (Seinfeld and Pandis 1998). There is no known evidence that PBLH affects people’s unethical behavior. Given these arguments, we justified using PBLH as an instrumental variable in this study. PBLH data with a resolution of 0.5̊ × 0.625̊ collected from NASA (2010) were matched with the locations of survey respondents at the grid level.

Model specifications

Our empirical model was designed to test whether monthly average NO2 concentrations significantly correlated with perceptions of unethical behavior at the corresponding locations, even after controlling for various variables that could contribute to the experience and perception of unethical behavior, such as personal attributes and heterogeneity associated with the residential area. Specifically, a two-stage instrumental variable model was employed with the respondent’s perception of unethical behavior as the dependent variable, the ZIP code-level monthly average NO2 concentration as the independent variable, and the ZIP code-level PBLH as the control variable. The model included ZIP code-level weather-related variables (e.g., monthly average temperature, precipitation, wind speed, and wind direction) and respondents’ socioeconomic variables (e.g., income, sex, age, education, family structure, and religion) as control variables. Various fixed effects related to country, region (e.g., Asia, Europe), first-level administrative district (e.g., state, province), second-level administrative district (e.g., city, town, village), year, and month were also considered (Tanaka and Okamoto, 2021).

To measure respondents’ perceptions of unethical behavior, we employed two types of indicators following the frameworks proposed by Chai et al. (2015) and Melo et al. (2018). The first indicator utilized a relatively straightforward approach by counting the number of unethical behaviors perceived or experienced by respondents in the recent past. We considered a total of 16 unethical behaviors; therefore, the maximum value of this straightforward index was 16, and the minimum value was 0. The second approach was based on item response theory (IRT), which is often used in educational testing to measure potential difficulties. While the straightforward approach assumed equal weights (i.e., equal difficulty) for all 16 unethical behaviors, the IRT-based approach relaxed these assumptions by assigning individual weights based on the perceived difficulty of each unethical behavior. The actual loadings (coefficients) for each unethical behavior were estimated using the IRT binary response model (one-parameter logistic), as presented in Table A2 in the Supplementary Information. Table A5 shows that a large loading coefficient (2.900) was estimated for unethical behaviors with high difficulty (e.g., terrorism), while a small loading coefficient (0.388) was estimated for unethical behaviors with low difficulty (e.g., theft/stealing). These coefficients were multiplied by each unethical behavior as weights and aggregated for each respondent to produce the IRT-based index of perceptions of unethical behavior. It is worth noting that since no significant differences were found between the regression results from the straightforward and IRT-based approaches, the results from the former approach are presented in the Results section due to space limitations. See Table A3 in the Supplementary Information for the estimation results from the IRT-based approach. For a summary of the means and standard deviations for each variable included in the model, see the summary of descriptive statistics in Table 2.

Results

Main result

Table 3 displays the estimated parameters of the main statistical model, presenting the average impact of monthly average NO2 concentration on perceptions of unethical behavior. As indicated by the first column in Table 3, a statistically significant positive correlation was observed between monthly average NO2 concentration and perceptions of unethical behavior at the corresponding location. In other words, as the monthly average NO2 concentration increased, the average perceptions of unethical behavior at the corresponding locations also increased. Unethical behavior, as defined by Jones (1991) and Lu et al. (2018), refers to “behavior that is illegal or morally unacceptable to the larger community.” The unethical behaviors considered in this study included prostitution, rape, child abuse, domestic violence, murder, terrorism, suicide, gender discrimination, racial discrimination, theft/stealing, gang violence/gang assault, privacy violation by police/military, drug trafficking, ownership of guns/rifles, fraud, and bribery/corruption. These unethical behaviors were divided into five groups through factor analysis: fatal (murder, terrorism, and suicide); assault (prostitution, rape, child abuse, and domestic violence); discrimination (gender and racial discrimination); financial (fraud and bribery/corruption); and organized (theft/stealing, gang violence/gang assault, drug trafficking, and ownership of guns/rifles). The estimates in the second and subsequent columns of Table 3 indicate that monthly average NO2 concentrations were significantly positively correlated with fatal, assault, and organized unethical behavior perceptions.

In the following sections, we conduct a detailed comparative analysis, intertwining economic indicators such as gross domestic product (GDP) with environmental metrics, particularly air pollution levels. We hypothesize that individuals in wealthier nations may exhibit increased sensitivity to slight rises in air pollution due to their infrequent exposure to such conditions. Nevertheless, these communities often possess greater resources to mitigate the effects of pollution, including the utilization of air purifiers.

Our study investigates the diverse responses to air pollution, specifically examining its correlation with perceptions of unethical behavior in relation to national NO2 pollution levels. A key aspect of our analysis is the concept of “pollution habituation,” prompting an in-depth examination of how varying exposure levels to environmental pollutants influence societal norms and ethical viewpoints. The following sections will thoroughly assess the varied impacts of air pollution, shedding light on the intricate relationship between environmental conditions and unethical behavior patterns.

Our findings reveal that: (1) Overall, the impact of air pollution on the perception of unethical behavior tends to differ by economic status, indicating a heightened sensitivity to pollution in more economically developed countries. (2) The analysis underscores the diversity in the marginal effects of air pollution on perceptions of unethical behavior across different national pollution levels, offering some evidence for the population’s adaptation to pollution. We will delve into these results in greater detail in the subsequent sections.

Heterogeneous effects on the national economic level

Table 4 illustrates the impact of monthly average NO2 concentration on perceptions of unethical behavior for each economic level category. The parameter estimates listed in each column of Table 4 were derived from a sub-model that included the interaction of three dummy variables (corresponding to percentiles of economic level categories based on GDP per capita) with the main model presented in Table 3 (a list of countries included in each category is presented in Table A5 in the Supplementary Information). The baseline for this analysis was countries with the lowest GDP per capita.

Overall, the impact of air pollution on the perception of unethical behavior appeared to vary across economic levels, suggesting that individuals in countries with higher economic status may be more sensitive to pollution. The first column of Table 4 indicates that the monthly average concentration of NO2 had a significant positive effect on the perception of unethical behavior for countries at the baseline and first and third percentile GDP per capita. Additionally, this column highlights that the marginal effects of increasing the monthly average concentration of NO2 on perceptions of unethical behavior were particularly pronounced in the wealthiest countries.

Furthermore, the second and subsequent columns of Table 4 demonstrate a significant positive correlation between monthly average NO2 concentration and perceptions of unethical behavior in wealthy countries. Perceptions related to fatal, assault, and organized unethical behaviors showed significant positive correlations with monthly average NO2 concentration, consistent with the main model findings (Table 1). Additionally, discrimination and financial unethical behaviors, which did not yield significant results in the main model, exhibited significant positive correlations with monthly average NO2 concentration in relatively wealthier countries (Table 4, columns 4 and 5).

Heterogeneous effects on national pollution level

We investigated the heterogeneity of the effects of air pollution on perceptions of unethical behavior based on national pollution levels to provide further evidence of pollution habituation. Table 5 illustrates the effect of monthly average NO2 concentrations on perceptions of unethical behavior for each category of national pollution levels. The parameter estimates in each column of Table 5 result from estimation with a sub-model that includes a cross-term with a dummy variable based on national pollution levels (total annual pollution by NO2) from the main model presented in Table 1 (A list of countries included in each category is presented in Table A5 in the Supplementary Information). The baseline in this case comprises countries with the lowest total annual NO2 pollution.

Overall, the results underscore the heterogeneity of the marginal effects of air pollution on perceptions of unethical behavior across national pollution levels, with partial evidence suggesting pollution habituation within the population. The first column of Table 5 illustrates that the influence of monthly average NO2 concentration on respondents’ perceptions of unethical behavior at their corresponding location was significantly positive at the baseline (representing the cleanest countries) and for categories with national annual pollution in the second and third percentiles. The effect of increasing monthly average NO2 concentration on perceptions of unethical behavior was particularly pronounced at the baseline and for the second percentile of national annual pollution (Table 5, column 1). Conversely, a negative correlation (albeit non-statistically significant) between air pollution and perceptions of unethical behavior was observed in the first percentile for national annual pollution. This suggests that people in countries with elevated pollution levels may have developed a degree of tolerance, leading to a diminished effect of pollution on their perceptions of unethical behavior.

In the second and subsequent columns of Table 5, consistent with the main model findings (Table 1), statistically significant positive correlations were observed between monthly average NO2 concentrations and perceptions of fatal, assault, and organized unethical behaviors. In addition, statistically significant positive effects were observed in the baseline categories for financial unethical behavior (Table 5, column 5), for which no significant effects were identified in the main model (Table 3). However, for discriminatory unethical behavior (Table 5, column 4), similar to the main model (Table 3), no statistically significant relationship was found for any pollution category. Notably, for the first percentile of national annual pollution, the monthly average NO2 concentration was negatively correlated with all types of perceptions of unethical behavior, although not statistically significant.

Heterogeneous effects on specific countries

The relationship between air pollution and perceptions of unethical behavior may vary significantly by country. Table 6 presents the country-specific effects of monthly average NO2 concentration on perceptions of unethical behavior. The estimates in Table 6 were derived from country-specific sub-models that maintained the specifications of the main model (Table 3) while only sampling respondents from individual countries. In Table 6, the values of the estimated parameters are denoted by positive and negative symbols, and the statistical significance of each parameter is indicated by the color depth of the corresponding cell. The darker the cell, the higher the statistical significance of the estimates.

The first column of Table 6 illustrates the overall impact of monthly average NO2 concentration on perceptions of unethical behavior at the corresponding locations. According to this column, a significant positive correlation was observed between monthly average NO2 concentration and the tendency of respondents in Brazil, France, Spain, and Turkey to perceive unethical behavior. In essence, a marginal increase in the monthly average NO2 concentration in these countries led to an average increase in the perception of unethical behavior.

The second and subsequent columns in Table 6 show the impact of monthly average NO2 concentration on perceptions of five different types of unethical behavior. It is noteworthy that in some countries (Brazil, China, Germany, Hungary, Indonesia, Myanmar, Russia, and the United States), a significant negative correlation was observed between monthly average NO2 concentration and the tendency to perceive specific unethical behavior. Therefore, a slight increase in monthly average NO2 concentration in these countries led to a decrease (on average) in the tendency to perceive specific unethical behavior. Additionally, it should be noted that the impact of monthly average NO2 concentration on perceptions of unethical behavior was not consistent across specific regions or types of unethical behavior. For example, a slight increase in monthly average NO2 concentration in Greece and the Netherlands led to an increase (on average) in the tendency to perceive fatal unethical behavior, while Germany, another European country, exhibited the opposite trend with a decrease in the tendency to perceive the same unethical behavior.

Discussion and implications

In this section, we discuss potential mechanisms for the positive correlation between NO2 concentrations and perceptions of unethical behavior identified in this study. First, NO2 exposure could induce anxiety symptoms, which can stimulate unethical behavior (Kouchaki and Desai, 2015; Corrigan and Watson, 2005). Mehta et al. (2015) and Lin et al. (2017) demonstrated that exposure to NO2 can lead to anxiety and stress disorders. Additionally, there is a known association between mental illness and unethical behavior, particularly violent behavior (Corrigan and Watson, 2005). Exposure to NO2 can increase susceptibility to psychiatric disorders such as depression, schizophrenia, and substance abuse, thereby contributing to unethical behavior (Cho et al., 2014; Pedersen et al., 2004; Szyszkowicz et al., 2018). Swanson, and Holzer (1992) found that individuals suffering from psychiatric disorders (e.g., schizophrenia) and substance abuse disorders exhibit a four- and ten-fold increase in violent behavior, respectively, compared to those without these disorders. Corrigan and Watson (2005) also found that individuals diagnosed with anxiety disorders or depression are three to four times more likely than those without such disorders to engage in violent behavior, while those with bipolar disorder or drug or alcohol abuse are eight times more likely.

Furthermore, physical discomfort caused by NO2 exposure may also incite unethical behavior. Air pollution can lead to irritation of the eyes, throat, and nose, as well as olfactory abnormalities (Chen et al., 2007); this discomfort may increase aggression and prompt unethical behavior (Rotton and White, 1996). Psychological studies by Rotton et al. (1978, 1979) and Rotton (1983) demonstrated that physical discomfort from odors, a component of air pollution, diminishes participants’ cognitive abilities and interpersonal attractiveness while increasing frustration and aggression. An indoor experiment by Rotton et al. (1979) confirmed that participants experiencing discomfort from pollution tended to administer stronger electric shocks to their peers on average than did other participants. Similar results have been observed in studies involving cigarette smoke (Jones and Bogat, 1978; Zillman et al., 1981).

Colored air pollutants, such as NO2, may also visually stimulate individuals (Lu, 2020), potentially influencing unethical behavior as a result of the obscured visibility caused by NO2 smog (Lu et al., 2018). Psychological studies conducted by Zhong et al. (2010) indicate that people are more likely to act dishonestly or selfishly in the dark, as darkness may create a sense of illusory anonymity. Similarly, Doleac and Sanders (2015) confirmed that ambient light reduces criminal behavior. Additionally, visual environmental disturbances due to air pollution may induce social and moral disturbances (Lu et al., 2018). The well-known “broken window theory” argues that public wrongdoing and degradation, such as broken windows and graffiti, can lead to an increase in serious crime (Wilson and Kelling, 1982). Indeed, according to a field experiment by Keizer et al. (2008), individuals who observe others violating social norms and rules are more likely to violate other norms and rules. Similarly, a psychological experiment by Gino et al. (2009) found that when unethical behavior is committed by members of the same group, it is more likely to be transmitted to other members. The disorder in urban neighborhoods caused by NO2 smog may have led to the spread of disorder through such psychological mechanisms.

While there are mechanisms that may account for the positive correlation between air pollution and perceived propensity for unethical behavior, mechanisms that support a negative correlation should also be noted. For instance, extremely high levels of air pollution may reduce aggression in individuals (Baron and Bell, 1976; Rotton et al., 1979; Rotton and White, 1996). Baron and Bell (1976) and Rotton and White (1996) proposed that moderate levels of stimulation can increase aggression, whereas extremely high levels of stimulation can elicit escape and withdrawal behaviors in individuals, consequently decreasing aggression. In the aforementioned psychological study by Rotton et al. (1979), participants exposed to moderately unpleasant odors exhibited strong aggression, while those exposed to odorless air or extremely unpleasant odors did not exhibit such strong aggression.

High concentrations of air pollution can alter people’s habitual behavior, thereby impacting the frequency of unethical behavior. Bresnahan et al. (1997) and Wen et al., (2009) demonstrated that individuals tended to engage in avoidance behavior, specifically refraining from going out on days when air pollution was severe and warnings were issued. This change in behavior could serve as the driving force behind both the increase and decrease in individuals’ encounters with unethical behavior. For example, increased time spent indoors because of pollution may increase the risk of encountering roommate conflicts, such as domestic violence and child abuse, and suicide due to loneliness and vitamin D deficiency (Anglin et al., 2013). However, a reduction in time spent outdoors also lowers the risk of encountering unethical behavior in outdoor settings, such as terrorism and theft. Additionally, the temporary reduction of the urban population due to pollution could create an ideal environment for individuals motivated by unethical behavior, given the absence of outdoor observers. However, such a phenomenon could simultaneously act as a disincentive for their unethical behavior to succeed, as there may not be suitable targets available.

This study confirms that individuals in locations with higher air pollution concentrations tend to perceive and experience more unethical behavior, and vice versa. Consequently, air pollution may incur even greater social costs than those directly attributable to health risks by inducing individual unethical behaviors. As such, it is important to reevaluate the additional social costs resulting from unethical behaviors and rebuild our social system to accurately reflect the costs of air pollution, based on a renewed recognition of its risks. Specifically, environmental regulatory guidelines developed solely based on the health risks of air pollution (e.g., WHO, 2006) and environmental taxation systems that fail to internalize the additional external costs of unethical conduct induced by air pollution are typical examples of existing social systems that need modification. For instance, new pollution guidelines based on criteria for the occurrence of unethical behavior could be developed and applied to alert citizens to prevent them from encountering unethical behavior and reduce extra social spending in response to unethical behavior.

The results also indicate that the impact of air pollution on perceptions of unethical behavior was heterogeneous, depending on the type of unethical behavior, national economic and pollution levels, and the country itself. The finding that increased air pollution in some countries had a negative impact on certain unethical behaviors (i.e., contributing to a decrease in unethical behavior) is crucial from a policymaking perspective. This is because, contrary to our general conclusion, air pollution could have unintended social benefits in such countries. In essence, mitigating air pollution in such countries and regions could inadvertently increase unethical behavior, which policymakers need to consider before implementing air pollution mitigation measures. Specifically, countries and regions where such phenomena are experienced need to implement air pollution mitigation policies while considering the potential increase in unethical (particularly criminal) behavior.

The current findings offer significant insights for policymaking in public health, urban planning, and environmental regulation. This study identified a positive correlation between air pollution, specifically NO2, and the perception of unethical behavior, suggesting that the social costs of air pollution extend beyond the traditionally recognized physical and mental health impacts, in line with previous research (Xue et al., 2019; Antonsen et al., 2020). Accordingly, we propose several key policy implications across diverse sectors.

Firstly, in public health, our findings support the integration of air quality considerations into broader health strategies. Policymakers are encouraged to prioritize reducing air pollution, not only to address health issues but also to mitigate social and behavioral concerns. This could entail implementing stricter emissions regulations, encouraging cleaner transportation options, and enhancing public awareness regarding the wide-ranging impacts of air pollution. In addition, facilitating an eco-surplus culture among urban residents can improve their willingness to pay for nature conservation (Nguyen, Jones 2022; Vuong, 2021; 2023).

Secondly, regarding urban planning, our research highlights the necessity of designing cities to minimize exposure to air pollution. Supporting literature indicates that urban air pollution, typically higher than rural levels, can lead to mental distress in urban populations (Bakolis et al., 2021; Glaeser et al., 2016). Following recommendations by Khreis et al., (2023) and Yoo et al., (2023), strategies such as congestion charging, developing urban green spaces, enhancing public transit systems, and promoting policies that reduce reliance on private vehicles are crucial. Such measures are instrumental in reducing NO2 levels, which can positively affect social behaviors and enhance urban well-being.

Additionally, our global evidence pinpoints specific countries particularly vulnerable to the impact of air pollution on unethical behaviors. This insight underscores the need for targeted interventions in areas with high NO2 concentrations. Community-level initiatives aimed at promoting ethical behavior and social cohesion are vital, especially in heavily polluted urban areas. In conclusion, our study advocates for comprehensive policy measures and thoughtful urban planning to address air pollution. Such initiatives promise not only health benefits but are also crucial in cultivating a more ethically conscious and socially cohesive society.

Although the present study reveals important findings, several limitations highlight the need for further research. First, the effect of air pollution on unethical behavior identified in our empirical model may be underestimated due to the possibility that not all respondents reported their actual perceived unethical behaviors. We acknowledge such limitations as a common problem of a questionnaire-based approach. Nevertheless, our survey offers significant advantages in recognizing and considering illegal unethical behavior (e.g., racism, gender discrimination, etc.), too sensitive to disclose (e.g., prostitution, rape, child abuse, domestic violence, etc.), or not treated as a criminal case because of the small amount of damage (e.g., larceny, theft, etc.). The bias of underreporting must be compensated for through future research using psychological experiments in a laboratory setting.

Another limitation of our study is our inability to consider air pollutants other than NO2 (e.g., SO2 and PM) due to data limitations. We utilized satellite observations of NO2 as a proxy for air pollution because our sample included many countries and regions, particularly developing countries, lacking sufficient monitoring facilities for air pollutants (Yerema and Managi, 2021). Differences in air pollutants are important, and we anticipate that the potential mechanisms influencing unethical behavior may vary depending on the type of pollutant. For example, related studies (Herrnstadt et al., 2021; Jones, 2022) also suggest that air pollution may affect serotonin levels in the brain, potentially leading to unethical behavior. Serotonin, a neurotransmitter, plays an important role in emotion regulation during social decision-making (Crockett et al., 2008). Although previous research has examined the correlation between serotonin depletion and impulsive aggression (Krakowski, 2003; Duke et al., 2013; Cunha-Bang and Knudsen, 2021), our literature review found no evidence that NO2 decreases brain serotonin levels. Therefore, it is unlikely that NO2 increases unethical behavior through a serotonin-related mechanism. Further studies should examine and compare multiple air pollutants with different properties.

Finally, our study did not identify statistically significant correlations between air pollution and certain unethical behaviors in some countries, especially those with limited sample sizes. It should be noted, however, that this result does not imply an absence of association between air pollution and unethical behaviors in such countries. In general, more localized studies focusing on specific unethical behaviors, air pollutants, countries, or regions should be conducted in the future to better understand the complex mechanisms between air pollution and unethical behavior. The results of this study can underscore the importance of such complementary research endeavors.

Data availability

Because of privacy concerns, the datasets created and/or examined for this project are not accessible to the general public. Making the entire data set publicly accessible may violate both the study’s ethical approval and the participants’ pledge of privacy when they consented to participate. Upon reasonable request, the data can be obtained from its corresponding author.

References

Abatzoglou J, Dobrowski S, Parks S et al. (2018) TerraClimate, a high-resolution global dataset of monthly climate and climatic water balance from 1958–2015. Sci Data 5:170191. https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2017.191

Anglin RES, Samaan Z, Walter SD, McDonald SD (2013) Vitamin D deficiency and depression in adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry 202:100–107. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.111.106666

Antonsen S et al. (2020) Exposure to air pollution during childhood and risk of developing schizophrenia: a national cohort study. Lancet Planet Health 4:e64–e73

Ardabily HE, Moghadam ZB, Salsali M, Ramezanzadeh F, Nedjat S (2011) Prevalence and risk factors for domestic violence against infertile women in an Iranian setting. Int J Gynecol Obstet 112:15–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2010.07.030

Bakolis I et al. (2021) Mental health consequences of urban air pollution: prospective population-based longitudinal survey. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 56:1587–1599

Banzhaf HS, Randall PW (2008) Do people vote with their feet? An empirical test of tiebout. Am Econ Rev 98:843–863

Baron RA, Bell PA (1976) Aggression and heat: The influence of ambient temperature, negative affect, and a cooling drink on physical aggression. J Person Soc Psychol 33:245–255. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.33.3.245

Block ML, Calderón-Garcidueñas L (2009) Air pollution: mechanisms of neuroinflammation and CNS disease. Trends Neurosci 32:506–516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tins.2009.05.009

Borg I, Hermann D (2023) Attitudes toward crime(s) and their relations to gender, age, and personal values. Curr Opin Behav Sci 4:100111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crbeha.2023.100111

Bresnahan BW, Dickie M, Gerking S (1997) Averting behavior and unban air pollution. Land Econ 73:340–357. https://doi.org/10.2307/3147172

Brunekreef B, Holgate ST (2002) Air pollution and health. Lancet 360:1233–1242. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11274-8

Chai A, Bradley G, Lo A, Reser J (2015) What time to adapt? The role of discretionary time in sustaining the climate change value–action gap. Ecol Econ 116:95–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2015.04.013

Chapman A, Fujii H, Managi S (2019) Multinational life satisfaction, perceived inequality and energy affordability. Nat Sustain 2:508–514. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-019-0303-5

Chen T-M, Gokhale J, Shofer S, Kuschner WG (2007) Outdoor air pollution: nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide, and carbon monoxide health effects. Am J Med Sci 333:249–256. https://doi.org/10.1097/MAJ.0b013e31803b900f

Cho J, Choi YJ, Suh M, Sohn J, Kim H, Cho SK, Ha KH, Kim C, Shin DC (2014) Air pollution as a risk factor for depressive episode in patients with cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, or asthma. J Affect Disord 157:45–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.01.002

Clément M, Piaser L (2021) Do inequalities predict fear of crime? Empirical evidence from Mexico. World Dev 140:105354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105354

Corrigan PW, Watson AC (2005) Findings from the National Comorbidity Survey on the frequency of violent behavior in individuals with psychiatric disorders. Psychiatry Res 136:153–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2005.06.005

Crockett MJ, Clark L, Tabibnia G, Lieberman MD, Robbins TW (2008) Serotonin modulates behavioral reactions to unfairness. Science 320:1739. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1155577

Cunha-Bang SD, Knudsen GM (2021) The modulatory role of serotonin on human impulsive aggression. Biol Psychiatry 90:447–457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2021.05.016

Doleac JL, Sanders NJ (2015) Under the Cover of darkness: how ambient light influences criminal activity. Rev Econ Stat 97:1093–1103. https://doi.org/10.1162/REST_a_00547

Duke AA, Bègue L, Bell R, Eisenlohr-Moul T (2013) Revisiting the serotonin–aggression relation in humans: A meta-analysis. Psychol Bull 139:1148–1172. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031544

ESA, EUMETSAT, 2000. Global Ozone monitoring experiment–2 data. accessed 1.7.21. https://www.eumetsat.int/gome-2

Fuller R, Landrigan PJ, Balakrishnan K, Bathan G, Bose-O’Reilly S, Brauer M, Caravanos J, Chiles T, Cohen A, Corra L, Cropper M, Ferraro G, Hanna J, Hanrahan D, Hu H, Hunter D, Janata G, Kupka R, Lanphear B, Lichtveld M, Martin K, Mustapha A, Sanchez-Triana E, Sandilya K, Schaefli L, Shaw J, Seddon J, Suk W, María Téllez-Rojo M, Yan C (2022) Pollution and health: a progress update. Lancet Planet Health 6:e535–e547. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(22)00090-0

Garcia-Moreno C, Jansen HAFM, Ellsberg M, Heise L, Watts CH (2006) Prevalence of intimate partner violence: findings from the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence. Lancet 368:1260–1269. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69523-8

Gino F, Ayal S, Ariely D (2009) Contagion and differentiation in unethical behavior: the effect of one bad apple on the barrel. Psychol Sci 20:393–398. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02306.x

Glaeser EL, Gottlieb JD, Ziv O (2016) Unhappy cities. J Labor Econ 34:S129–S182

Herrnstadt E, Heyes A, Muehlegger E, Saberian S (2021) Air pollution and criminal activity: microgeographic evidence from Chicago. Am Econ J: Appl Econ 13:70–100. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.20190091

Jessup RL, Osborne RH, Beauchamp A et al. (2017) Health literacy of recently hospitalised patients: a cross-sectional survey using the Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ). BMC Health Serv Res 17:52. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1973-6

Jones BA (2022) Dust storms and violent crime. J Environ Econ Manag 111:102590. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeem.2021.102590

Jones JW, Bogat GA (1978) Air pollution and human aggression. Psychol Rep. 43:721–722. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1978.43.3.721

Kalkuhl M, Wenz L (2020) The impact of climate conditions on economic production. evidence from a global panel of regions. J Environ Econ Manag 103:102360

Keizer K, Lindenberg S, Steg L (2008) The spreading of disorder. Science 322:1681–1685. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1161405

Khreis H et al. (2023) Urban policy interventions to reduce traffic-related emissions and air pollution: A systematic evidence map. Environ Int 172:107805

Kouchaki M, Desai SD (2015) Anxious, threatened, and also unethical: How anxiety makes individuals feel threatened and commit unethical acts. J Appl Psychol 100:360–375. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037796

Krakowski M (2003) Violence and serotonin: Influence of impulse control, affect regulation, and social functioning. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 15:294–305. https://doi.org/10.1176/jnp.15.3.294

Lee JJ, Gino F, Jin ES, Rice LK, Josephs RA (2015) Hormones and ethics: Understanding the biological basis of unethical conduct. J Exp Psychol: Gen 144:891–897. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000099

Li C, Managi S (2022) Spatial variability of the relationship between air pollution and well-being. Sustain Cities Soc 76:103447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2021.103447

Li H, Cai J, Chen R, Zhao Z, Ying Z, Wang L, Chen J, Hao K, Kinney PL, Chen H et al. (2017) Particulate matter exposure and stress hormone levels: a randomized, double-blind, crossover trial of air purification. Circulation 136:618–627. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.026796

Li Y, Guan D, Yu Y et al. (2019) A psychophysical measurement on subjective well-being and air pollution. Nat Commun 10:5473. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-13459-w

Lin Y, Zhou L, Xu J, Luo Z, Kan H, Zhang J, Yan C, Zhang J (2017) The impacts of air pollution on maternal stress during pregnancy. Sci Rep. 7:40956. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep40956

Liu W, Sun H, Zhang X, Chen Q, Xu Y, Chen X, Ding Z (2018) Air pollution associated with non-suicidal self-injury in Chinese adolescent students: a cross-sectional study. Chemosphere 209:944–949. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.06.168

Lu JG (2020) Air pollution: A systematic review of its psychological, economic, and social effects. Curr Opin Psychol 32:52–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2019.06.024

Lu JG, Lee JJ, Gino F, Galinsky AD (2018) Polluted morality: air pollution predicts criminal activity and unethical behavior. Psychol Sci 29:340–355. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797617735807

Manisalidis I, Stavropoulou E, Stavropoulos A, Bezirtzoglou E (2020) Environmental and health impacts of air pollution: a review. Front Public Health 8:14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.00014

Mehta AJ, Kubzansky LD, Coull BA et al. (2015) Associations between air pollution and perceived stress: the Veterans Administration Normative Aging Study. Environ Health 14:10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-069X-14-10

Melo PC, Ge J, Craig T, Brewer MJ, Thronicker I (2018) Does work-life balance affect pro-environmental behaviour? Evidence for the UK using longitudinal microdata. Ecol Econ 145:170–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2017.09.006

NASA, 2010. MERRA-2 accessed 1.7.21. https://gmao.gsfc.nasa.gov/reanalysis/MERRA-2/

Nguyen MH, Jones TE (2022) Building eco-surplus culture among urban residents as a novel strategy to improve finance for conservation in protected areas. Hum Soc Sci Commun 9:426, https://www.nature.com/articles/s41599-022-01441-9

Okuyama A, Yoo S, Managi S (2022) Children mirror adults for the worse: evidence of suicide rates due to air pollution and unemployment. BMC Public Health 22:1614. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-14013-y

Pedersen CB, Raaschou-Nielsen O, Hertel O, Mortensen PB (2004) Air pollution from traffic and schizophrenia risk. Schizophr Res 66:83–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0920-9964(03)00062-8

Power MC, Kioumourtzoglou M, Hart JE, Okereke OI, Laden F, Weisskopf MG et al. (2015) The relation between past exposure to fine particulate air pollution and prevalent anxiety: observational cohort study. BMJ 350:h1111. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h1111

Rammal H, Bouayed J, Younos C, Soulimani R (2008) Evidence that oxidative stress is linked to anxiety-related behaviour in mice. Brain, Behav, Immun 22:1156–1159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2008.06.005

Rotton J (1983) Affective and cognitive consequences of malodorous pollution. Bas Appl Soc Psychol 4:171–191. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15324834basp0402_5

Rotton J, Barry T, Frey J, Soler E (1978) Air pollution and interpersonal attraction. J Appl Soc Psychol 8:57–71. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1978.tb00765.x

Rotton J, Frey J, Barry T, Milligan M, Fitzpatrick M (1979) The air pollution experience and physical aggression. J Appl Soc Psychol 9:379–412. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1979.tb02714.x

Rotton J, White SM (1996) Air pollution, the sick building syndrome, and social behavior. Environ Int 22:53–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-4120(95)00102-6

Rotton J, Frey J (1985) Air pollution, weather, and violent crimes: Concomitant time-series analysis of archival data. J Pers Soc Psychol 49:1207–1220. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.49.5.1207

Sass V, Kravitz-Wirtz N, Karceski SM, Hajat A, Crowder K, Takeuchi D (2017) The effects of air pollution on individual psychological distress. Health Place 48:72–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2017.09.006

Schwartz J, Bind MA, Koutrakis P (2017) Estimating causal effects of local air pollution on daily deaths: effect of low levels. Environ Health Perspect 125:23–29. https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP232

Seaton A, Godden D, MacNee W, Donaldson K (1995) Particulate air pollution and acute health effects. Lancet 345:176–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(95)90173-6

Seinfeld JH, Pandis SN (1998) Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics: From Air Pollution to Climate Change. John Wiley & Sons, New York

Sen S, Bolsoy N (2017) Violence against women: prevalence and risk factors in Turkish sample. BMC Women’s Health 17:100. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-017-0454-3

Sumter M, Wood F, Whitaker I, Berger-Hill D (2018) Religion and crime studies: assessing what has been learned. Religion 9:193. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9060193

Swanson J, Holzer CE (1992) Violence and psychiatric disorder in the community: evidence from the epidemiologic catchment area surveys. Hosp Commun Psychiatry 42:954–955. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.41.7.761

Szyszkowicz M, Thomson EM, Colman I, Rowe BH (2018) Ambient air pollution exposure and emergency department visits for substance abuse. PLoS One 13:e0199826. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0199826

Tanaka T, Okamoto S (2021) Increase in suicide following an initial decline during the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan. Nat Hum Behav 5:229–238. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-01042-z

Volk HE, Lurmann F, Penfold B, Hertz-Picciotto I, McConnell R (2013) Traffic-related air pollution, particulate matter, and autism. Arch Gen Psychiatry 70:71–77. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.266

Vuong, Q-H (2023). “Mindsponge theory,” De Gruyter

Vuong QH (2021) The semiconducting principle of monetary and environmental values exchange. Econ Bus Lett 10:284–290. https://doi.org/10.17811/ebl.10.3.2021.284-290

Wen XJ, Balluz L, Mokdad A (2009) Association between media alerts of air quality index and change of outdoor activity among adult asthma in six states, BRFSS, 2005. J Commun Health 34:40–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-008-9126-4

Wilson JQ, Kelling G (1982) Broken windows: the police and neighborhood safety. Atlantic 127:29–38

World Health Organization, WHO Air Quality Guidelines for Particulate. Matter, Ozone, Nitrogen Dioxide and Sulfur Dioxide - Global Update 2005, World Health Organization, Geneva., (2006). https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/78638/E90038.pdf

Xue T et al. (2019) Declines in mental health associated with air pollution and temperature variability in China. Nat Commun 10:2165

Yang AC, Tsai SJ, Huang NE (2011) Decomposing the association of completed suicide with air pollution, weather, and unemployment data at different time scales. J Affect Disord 129:275–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2010.08.010

Yerema CT, Managi S (2021) The multinational and heterogeneous burden of air pollution on well-being. J Clean Prod 318:128530. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.128530

Yoo S et al. (2023) Economic and air pollution disparities: Insights from transportation infrastructure expansion. Transp Res Part D: Transp Environ 125:103981

Zheng S, Wang J, Sun C et al. (2019) Air pollution lowers Chinese urbanites’ expressed happiness on social media. Nat Hum Behav 3:237–243. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-018-0521-2

Zhong C-B, Bohns VK, Gino F (2010) Good lamps are the best police: darkness increases dishonesty and self-interested behavior. Psychol Sci 21:311–314. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797609360754

Zillman D, Baron RA, Tamborini R (1981) Social costs of smoking: Effects of tobacco smoke on hostile behavior. J Appl Soc Psychol 11:548–561. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1981.tb00842.x

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.N: Conceptualization, methodology, writing (original draft, review, and editing); S.Y: Methodology, formal analysis, writing (review and editing); S.K: Methodology, writing (editing); S.M: Resources and supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The original cross-sectional survey, carried out by Nikkei Research Company between 2015 and 2017, received formal approval from Kyushu University’s legal and ethics review board. Data collection was compliant with legal and ethical standards, and participants provided informed consent. All procedures adhered to the relevant guidelines and regulations set by Kyushu University.

Informed consent

The data collection rigorously adhered to ethical standards, following established social science methodologies. Before initiating the survey, data collectors received extensive training on ethical considerations. Each respondent provided informed consent, fully understanding that their information would be treated with utmost confidentiality and used exclusively for research purposes. They were informed that personal details, including names, would be anonymized in all research outcomes. Additionally, we emphasized that participation was entirely voluntary, and respondents could raise queries or choose to discontinue the interview at any time.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nakaishi, T., Yoo, S., Kagawa, S. et al. Impact of air pollution on human morality: A multinational perspective. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 991 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03186-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03186-z