Abstract

Teaching a foreign language requires instructors to be knowledgeable about and capable of providing instruction that facilitates their students’ ability to understand, speak, read, and write the new language. However, as established within the literature, there appears to be a disconnect between what should be offered as pronunciation instruction and what takes place in many EFL classrooms. This study, therefore, undertook to identify Saudi university EFL instructors’ perceptions and practices towards pronunciation instruction. The study employed a mixed methods survey research design, combining qualitative and quantitative approaches. Participants included 163 EFL instructors from Saudi universities. The results of the current study showed that while most participants recognized the importance of pronunciation instruction and were confident of their English pronunciation, many also felt that they lacked the training necessary to fully provide instruction and assessment of their students’ English pronunciation. The participants also identified those extraneous factors that affected their ability to provide fulsome pronunciation learning experiences. The study highlights the existing gap between the ideal pronunciation instruction and the current practices in Saudi university EFL classrooms. It emphasizes the need for enhanced training for instructors to improve their ability to deliver effective pronunciation instruction and assessment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

English is spoken as a second language (L2) by just over 1 billion people worldwide (Yadav, 2023), and most of these L2 speakers have been taught by non-native speakers. English is no longer solely tied to its traditional native-speaker communities (such as the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, etc.) but has become a global language with multiple localized adaptations and variations. These variations can differ in pronunciation, vocabulary, grammar, idiomatic expressions, and cultural references. Therefore, pronunciation instruction has undergone an important shift in the literature (Saito and Plonsky, 2019), allowing a more multilingual view. According to Pennington (2021), there is a shift from achieving a complete acquisition that is indistinguishable from a native-speaker to tolerating multiple models for speech influenced by various linguistic backgrounds. Realizing that much of the communication occurs among individuals who speak English as their L2, appropriate goals for pronunciation have been reconsidered (Derwing, 2019; Levis and Zawadzki, 2023). The stress is now on maintaining meaningful communication focusing on intelligibility and comprehensibility rather than native-like pronunciation (Almusharraf, 2021; Saito and Plonsky, 2019). Intelligibility refers to the ability to be understood by others when speaking a language, while comprehensibility is how easy or difficult it is for the listener to understand the speaker’s message (Huensch and Nagle, 2021).

Teaching pronunciation is crucial to language learning and teaching (Derwing, 2019; Kochem, 2022; Murphy, 2017; Nagel et al., 2018; Uchida and Sugimoto, 2020). Pronunciation affects how learners communicate in English and how others perceive them. Poor pronunciation can hinder learners’ ability to be understood and communicate effectively, leading to frustration and a lack of confidence. Those learning to speak a new language seek to perfect their pronunciation of the words they are learning to ensure that others comprehend what is being spoken. Pronunciation refers to how the words of a language are spoken. Developing proper pronunciation requires the consideration of segmental (e.g., consonant and vowel sounds) and suprasegmental (e.g., word stress, sentence stress, intonation, and rhythm) linguistic features.

The phonetic and phonological systems of Arabic and English differ significantly, which contributes to the pronunciation challenges faced by Saudi learners of English as a foreign language (EFL). Arabic has a relatively simple vowel system with only six vowel phonemes, while English has a much more complex vowel system with at least twelve vowel phonemes. Additionally, the Arabic language lacks certain consonant sounds found in English, such as /p/, /v/, and /ʒ/, which can lead to difficulties for Saudi EFL learners when attempting to produce these sounds accurately.

One of the most common pronunciation issues for Saudi EFL learners is the confusion between the voiced bilabial stop /b/ and the voiceless bilabial stop /p/. Due to the absence of the /p/ sound in the Arabic phonemic inventory, Saudi learners often substitute /b/ for /p/, resulting in mispronunciations like “people” being pronounced as “beople.” Similarly, Saudi EFL learners frequently struggle with the distinction between the voiced labiodental fricative /v/ and the voiceless labiodental fricative /f/, often replacing /v/ with the more familiar /f/ sound.

Because accepting and experiencing English diversity would be a realistic view of today’s English instruction (Boonsuk et al., 2023), it is essential to examine whether instructors accept such a view. Pronunciation is prominent in the language curriculum; however, what to include in pronunciation as a curriculum area and the best way to teach it is controversial (Saito and Plonsky, 2019). Furthermore, although L2 pronunciation is an essential skill for effective communication (Munro and Derwing, 2015), there is a dearth of research on pronunciation instruction, especially in relation to L2 teachers’ beliefs and practices regarding such instruction (Tsunemoto et al., 2023). This situation has led researchers to call for more L2 pronunciation studies (Derwing, 2019; Kochem, 2022; Murphy, 2017). Moreover, L2 pronunciation is often missing in teacher training programs (Huensch, 2019a; Murphy, 2017), resulting in a neglect of pronunciation instruction in the EFL classroom (Derwing, 2019). Research has reported that instructors lack the confidence, knowledge, and skills to teach L2 pronunciation (Kochem, 2022; Uchida and Sugimoto, 2020).

By identifying the instructors’ perspectives on pronunciation instruction and their perceived training needs, the study sheds light on the existing gap between the desired and actual practices in EFL classrooms. This research also contributes to the overall understanding of the challenges faced by instructors in providing effective pronunciation instruction. Therefore, research on teacher beliefs about the value of providing instruction to improve students’ pronunciation is merited. In this vein, the following research questions were put forward:

Research Question 1 (RQ1): What are Saudi university EFL teachers’ beliefs about the importance of teaching pronunciation?

Research Question 2 (RQ2): How confident are Saudi university EFL instructors in their English pronunciation?

Research Question 3 (RQ3): How well do Saudi university EFL instructors perceive they have been trained for pronunciation instruction?

Research Question 4 (RQ4): What are the practices Saudi university EFL instructors use for effective pronunciation instruction?

Research Question 5 (RQ5): What factors do Saudi university EFL instructors believe impact effective pronunciation instruction?

Review of the literature

The importance of pronunciation instruction in EFL teaching has been well-established in the literature. Research has consistently highlighted the vital role of pronunciation in enhancing learners’ intelligibility, confidence, motivation, and overall communicative competence (Derwing, 2019; Kochem, 2022; Murphy, 2017; Nagel et al., 2018; Uchida and Sugimoto, 2020). However, the literature suggests a concerning disconnect between the recognized importance of pronunciation instruction and the realities of what takes place in many EFL classrooms. Understanding these underlying issues is crucial for developing strategies to address the pronunciation instruction gap. The present study, therefore, seeks to explore Saudi university EFL instructors’ perceptions and practices regarding pronunciation instruction, to gain insights that can inform more effective approaches to support the development of learners’ pronunciation skills.

Beliefs about the importance of pronunciation instruction

Instructors’ beliefs about the efficacy of an instructional strategy can influence its success. In other words, what instructors think will affect the way they teach. Teacher cognition can be defined as the practical mental constructs teachers hold, often implicit and dynamically shaped by their educational and professional experiences (Borg, 2006). These constructs play a significant role in teachers’ decision-making regarding instructional choices, as they are informed by their knowledge, beliefs, and attitudes. Despite scholarly attention being paid to language instructors’ beliefs, experiences, and the relationship between their beliefs and practices, there remains a need for further investigation into teacher cognition of pronunciation instruction (Kochem, 2022; Tsang, 2021; Tsunemoto et al., 2023).

Within an L2 classroom, exploring instructors’ beliefs regarding pronunciation instruction is important for understanding their pronunciation-related instructional practice. Research on instructors’ beliefs about pronunciation instruction has been conducted in several different foreign language areas. Within the EFL classroom, Buss (2016) surveyed teachers at all levels of education in Brazil and found that over 90% of teachers considered the teaching of pronunciation from important to extremely important. Similarly, Uchida and Sugimoto (2020) surveyed junior high school instructors in Japan and found that while 96% of these instructors agreed that pronunciation instruction is important, only 73% believed that such instruction is effective in improving students’ pronunciation. Uchida and Sugimoto’s study also showed that the more confident instructors were in their own pronunciation, the more likely they were to value pronunciation instruction and believe in its effectiveness.

Research on instructors’ beliefs about the importance of pronunciation instruction has also been conducted with respect to other foreign languages. For example, Huensch (2019a) found that, among the French, German, and Spanish instructors she surveyed, 95% indicated that they believed pronunciation instruction is important. On the other hand, the Spanish instructors in the United States surveyed by Nagel et al. (2018) expressed an overall belief in the importance of providing pronunciation instruction that only fell midway between slightly disagree to slightly agree. However, the findings from this study also showed that instructors who had taken courses focusing on pronunciation instruction regarded pronunciation instruction as significantly more important than instructors who had not. Nagle et al. (2020) also found that participants who had received pronunciation training reported a more positive degree of value toward pronunciation instruction than those with little or no training. Notwithstanding this research finding, L2 instructors participating in a study conducted by Tsunemoto et al. (2023) reported that the pronunciation instruction courses they had taken focused more on theory than pedagogy. It is important to note that even though pronunciation-focused courses can help instructors apply knowledge about specific pronunciation teaching techniques to classroom practice, teachers’ beliefs do not necessarily reflect their classroom practice (Burri et al., 2017). For example, Huensch (2019b) reported that even though most of the instructors in her study believed in the importance of pronunciation instruction and were prepared to teach pronunciation, on average, only 15 min per week of their class time was devoted to pronunciation. Similarly, in a study involving in-class observations of Quebec Francophone Grade 6 ESL teachers, Foote et al. (2016) found that pronunciation-related instruction represented only 10% of the language instructional time.

Instructional practices for the improvement of pronunciation

The dominant view among scholars is that the primary objective of EFL pronunciation instruction should be to attain intelligibility rather than striving for native-like proficiency (Tsunemoto et al., 2023). Tsang (2021) reported that research has shown a tendency among instructors to prefer General American (GA) or Received Pronunciation (RP) as the target accent for pronunciation instruction; however, it should be noted that these teachers may not necessarily demand their learners to speak with GA/RP pronunciation.

Alghazo and Zidan (2019) explored EFL university students’ experiences learning English pronunciation from both native and non-native English-speaking teachers, finding that most students still view “nativeness” as the main descriptor of effective teaching, strongly believing native speakers to be the “authority” and source of “correctness,” emblematic of native-speakerism, which can lead to cultural panic and voicelessness for non-native teachers and learners. They conclude with a call to raise awareness of the irrelevance of nativeness to effective teaching and the need to incorporate non-native teachers into L2 pronunciation instruction in EFL contexts.

Studies on teaching and learning L2 pronunciation have shown that attention to pronunciation form, especially with corrective feedback, can improve segmental and suprasegmental pronunciation (Saito and Saito, 2017). Explicit instruction of phonetic and phonological features of the L2 can help learners develop intelligible and comprehensible L2 speech, even if they have a foreign accent (Gordon, 2023). Explicit instruction will also allow learners to recognize the differences between their L1 and L2 speech (Lee et al., 2015). Taking a linguistic or phonology course is insufficient to see how linguistic knowledge relates to teaching; instructors and learners need explicit pronunciation instruction courses to inform their practice (Derwing, 2019).

Lee et al. (2015) conducted a meta-analysis of 86 studies and found that pronunciation instruction significantly impacts students’ pronunciation development; these effects differ depending on the context (e.g., target language, instructional setting, proficiency level) and the teaching methodology used. Previous research has found that pronunciation teaching effectively improves learners’ pronunciation concerning accentedness, intelligibility, comprehensibility, and fluency (Derwing, 2019; Huensch and Nagle, 2021).

Alghazo et al. (2023) investigated the effectiveness of perception-based and production-based pronunciation instruction (PI) on the acquisition of English pronunciation by Jordanian Arabic-speaking learners of English, finding that both types of PI were effective in developing most aspects of L2 pronunciation. Perception-based instruction was more effective in improving segmental, syllabic, and prosodic aspects, while production-based instruction was more effective in improving global and temporal aspects of pronunciation.

Reasons for the lack of effective pronunciation instruction

Where insufficient and inadequate pronunciation instruction exists, it is helpful to determine the reasons for such neglect. Even though instructors often believe L2 pronunciation instruction is essential (Huensch, 2019a; Huensch, 2019b; Nagle et al., 2018), they lack knowledge in teaching pronunciation. Most EFL instructors have formal certification in English language teaching but lack specific training in pronunciation teaching (Huensch, 2019a), which may explain why many instructors are hesitant about pronunciation instruction and question its effectiveness (Kochem, 2022; Murphy, 2017; Nagle et al., 2018; Tsunemoto et al., 2023). Foote et al. (2011) reported that, of the ESL instructors in Canada who participated in their study, only 50% reported receiving training in pronunciation instruction, while Buss (2016) found that 90% of Brazilian EFL teachers participating in her study indicated they would welcome more training.

Furthermore, Foote et al. (2016) examined the practice of three experienced English instructors and noted that they tended to prioritize grammar and vocabulary over pronunciation. Although the study instructors took basic pronunciation training, they did not feel confident enough to teach pronunciation in the classroom. Similarly, Couper (2017) interviewed 19 English teachers to investigate their knowledge and perceptions concerning pronunciation teaching. Couper concluded that most of these teachers were neither trained in pronunciation instruction nor received much education in phonetics and phonology.

Another reason instructors may avoid teaching pronunciation is the difficulty in assessment of pronunciation, which also reflects a lack of training. Derwing (2019) pointed out that instructors tend to avoid assessing pronunciation, and because it is not assessed, pronunciation is not given due consideration in L2 teaching. Among the Australian ESL instructors interviewed by MacDonald (2002), none reported “using or having knowledge of a framework which they found helpful for assessment or recording of students’ pronunciation” (p. 7). Further, Kochem (2022) found that participants in an 8-week online pronunciation pedagogy course reported that the only assessment strategy to which they were exposed was “a single, holistically rated construct on language rubrics” (p. 75). The problem these participants had with this single metric for assessing pronunciation was that “they struggled to understand how to rate the many features of pronunciation as a single score” (p. 75).

More importantly, it appears self-evident that if you lack confidence in your ability to demonstrate a particular skill, you are unlikely to provide instruction that will assist others in developing that skill. Such may be the case for instructors who lack confidence in their own pronunciation. Therefore, identifying the level of confidence that instructors have in their pronunciation might provide explanatory power to learning situations where there is little to no pronunciation instruction offered in L2 classrooms. In a study conducted by Uchida and Sugimoto (2020) with Japanese junior high school EFL teachers, 70% of these teachers reported confidence in pronouncing English words. However, in the Uchida and Sugimoto study, only 58% felt confident in their pronunciation of sentences and passages, and 50% were confident in their pronunciation in general.

Additionally, in a study conducted by Macdonald (2002), some instructors were reluctant to monitor students’ pronunciation for fear of backlash, given that some students might consider the criticism of their pronunciation an attack against their identity. Other instructors in this study believed that pronunciation instruction is of secondary importance because substandard pronunciation is acceptable as long as the listener can comprehend what is being said. In contrast, others indicated that they used pronunciation instruction sparingly because they believed that focusing on correcting pronunciation interrupts the development of linguistic fluency.

Finally, the lack of suitable teaching and learning materials and the lack of time to practice pronunciation could lead instructors to pay less attention to L2 pronunciation. Pourhosein Gilakjani and Sabouri (2016) reported that 78% of their participants agreed or strongly agreed that they lacked the necessary materials to provide proper pronunciation instruction and that 92% agreed or strongly agreed that they lacked the computer hardware and software specific for pronunciation instruction. Even when computer software is available, many instructors report it as “heavily segment-focused in nature” (Breitkreutz et al., 2001, p. 58). Part of the problem may be that many EFL instructors lack sufficient facilities to use computer hardware and software that supports pronunciation instruction.

Based on the reviewed literature, a research gap becomes evident concerning the specific beliefs held by EFL instructors in Saudi Arabia regarding the significance of teaching pronunciation. Despite the extensive body of literature exploring beliefs about pronunciation instruction in various contexts, there is limited research conducted within the Saudi Arabian context. Furthermore, while a growing body of research exists on pronunciation instruction practices, there is a lack of investigation into the specific practices employed by Saudi university EFL instructors to facilitate effective pronunciation instruction. Extending the current knowledge base requires further exploration of the instructional practices, techniques, and materials implemented by Saudi university EFL instructors when teaching pronunciation. Additionally, it is essential to consider the underlying reasons that shape their instructional decisions and choices, encompassing aspects such as pedagogical training, professional experiences, perceived learner needs, and cultural considerations.

Investigating the Saudi context is crucial due to its unique cultural and linguistic characteristics, which can influence the beliefs, attitudes, and instructional practices of EFL instructors. Understanding the specific challenges and needs of Saudi learners can inform curriculum development, teacher training programs, and instructional materials tailored to the Saudi context. Investigating pronunciation instruction in the Saudi context not only contributes to the field of English language teaching but also offers insights that can be applicable to other EFL contexts facing similar challenges. Therefore, the present study aims to fill this research gap by examining the beliefs and practices of Saudi university EFL instructors on pronunciation instruction.

Methods

This study employed a mixed methods survey research design. Cross-sectional survey research was a suitable methodological choice for this exploratory research, as the intent was to identify the beliefs and practices of Saudi university EFL instructors concerning pronunciation instruction. The closed items were designed to gather quantitative data that were analyzed statistically, while the open-ended question was intended to provide qualitative data that were analyzed using thematic analysis.

Participants and setting

In this study, a convenience sampling approach was utilized to recruit a diverse pool of EFL instructors. After excluding 23 participants who did not meet the study criteria, the final sample consisted of 163 instructors, all of whom worked in postsecondary institutions within Saudi Arabia, mostly in colleges and universities within Riyadh province. The nationality of the participants was primarily Saudi (81.6%), while the remaining participants represented a range of nationalities including Jordanian, Egyptian, Tunisian, Sudanese, Yemeni, and Syrian. Additional demographic variables of the participants are provided in Table 1. The convenience sampling approach ensured inclusivity and maximized participant numbers, allowing for a comprehensive exploration of the research objectives within the Saudi context.

Instrumentation

The researchers developed a survey based on one developed and used by Nagle et al. (2020), an examination of the literature, and the first author’s experience as a university EFL instructor. This survey was used to gather data on the EFL instructors’ beliefs about, confidence in, and practices related to pronunciation instruction. Six professors of applied linguistics or English as a foreign language reviewed the initial survey for validation. All the reviewers agreed that the survey had face validity and, therefore, reflected the intended purpose of the survey. These reviewers also examined the survey for content validity and suggested several changes to the survey items. The survey was amended to reflect these suggestions, after which four of the six professors reviewed the survey again to calculate content validity indices. The content validity index score for confidence in one’s pronunciation, training, factors affecting teaching pronunciation, and instructors’ practice in teaching English pronunciation was 1.00; the score for beliefs about the importance of pronunciation instruction was 0.96.

A pilot study of the survey was conducted with 10 university EFL instructors. Based on their feedback, one item was removed from the survey, and wording changes were made to some items. The final version of the survey contained seven items related to the participants’ beliefs about the importance of pronunciation instruction, four items related to their confidence in providing pronunciation instruction, three items related to their pronunciation instruction training, and nine items related to factors they believed affected pronunciation teaching. To answer these questions, participants were presented with a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neither disagree nor agree, 4 = agree, 5 = strongly agree). The final set of items queried the participants on their practice regarding pronunciation instruction. These nine items were assessed on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = never, 2 = rarely, 3 = sometimes, 4 = frequently, 5 = always). The survey also included an open-ended question asking participants whether they normally focused on pronunciation in their classes and to explain why or why not. Participants’ answers to the open-ended question were used to assist in explaining some of the quantitative results.

Procedures

The survey was sent through Google Forms to EFL instructors at the three highest-ranking universities in Riyadh. Some of those instructors forwarded the survey to EFL professors in other universities across Saudi Arabia. Those instructors interested in participating in this research were asked to complete the survey online and submit it through an attached link. Informed consent to participate in the research was indicated by a participant’s willingness to complete and submit the survey.

Data analysis

All seven items related to the participants’ belief about the importance of pronunciation instruction were aggregated to produce a mean score. As a measure of internal consistency for this construct, Cronbach’s alpha value for these seven items was 0.75. Likewise, all four items related to the participants’ confidence in their English pronunciation were aggregated to produce a mean score. Cronbach’s alpha for these four items was 0.74. However, concerning the participants’ belief in the quality of training they received for pronunciation instruction, a mean score was determined for each of the three questions. Descriptive statistics are also reported for each question related to the frequency of different types of strategies used in teaching pronunciation and the impact of numerous factors on pronunciation instruction.

An item on the survey required participants to indicate the level of pronunciation training they had received. The options for this item were as follows: (a) I did not attend any teaching methods courses; (b) I attended a teaching methods course without information on teaching pronunciation; (c) I attended methods coursework with basic information on pronunciation, such as core concepts in phonology and articulatory phonetics, some reference to theory, and/or basic pedagogical issues; (d) I attended a teaching methods coursework with more advanced information on pronunciation, including exposure to empirical research and/or concrete lesson-planning focused on facilitating pronunciation development through specific techniques and activities; (e) I attended a pronunciation teaching course with basic information on teaching pronunciation; and (f) I attended a pronunciation teaching course with advanced information on teaching pronunciation. The six options were collapsed into three groups as illustrated in Table 2. With these groups in mind, a one-way ANOVA was conducted to determine the impact of the participants’ level of pronunciation instruction training on their beliefs about the importance of pronunciation instruction, their confidence in their English pronunciation, and for each of the three questions related to their belief in the quality of training received for pronunciation instruction. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS, version 28.

Regarding the open-ended question, thematic analysis was employed to analyze the qualitative data. The process involved systematically identifying and analyzing patterns, codes, and themes to extract meaningful insights relevant to the research question. To ensure rigor and interrater reliability, the researcher, in collaboration with a Ph.D. instructor specialized in Education, independently read and analyzed the qualitative data. Through a systematic approach, the researcher and the Ph.D. instructor identified codes and themes based on the content of the responses, following established principles of thematic analysis. This involved identifying recurring patterns, extracting key concepts, and organizing the data into meaningful thematic categories. To assess the agreement between the two independent analyses, an interrater reliability score was calculated using established measures such as the Pearson correlation coefficient. The resulting score of 0.95 indicated a high level of agreement between the researcher and the Ph.D. instructor in their interpretations of the qualitative data, strengthening the reliability of the thematic analysis process.

Findings

The findings from this study are organized according to the order of the research questions that have been posed and subsequently supplemented by a thematic analysis of the open-ended responses. Thus, these findings will describe the participants’ beliefs about the importance of pronunciation instruction, their confidence in their English pronunciation, their beliefs in the quality of training received for pronunciation instruction, the practices they use for pronunciation instruction, and their beliefs about the factors that affect the provision of pronunciation instruction. In the following sections, where comparisons based on the level of pronunciation training are made, NoTraining represents no pronunciation training, MethodCourse+Pronounciation represents a methods course with pronunciation training included, and PronCourseOnly represents a separate course on pronunciation instruction (see Table 2).

Belief about the importance of pronunciation instruction

To address RQ1, participants were queried regarding their beliefs about the importance of pronunciation instruction. The mean belief score of all participants was 3.46 (SD = 0.50). The score is halfway between neither disagree nor agree (3) and agree (4) and leans more toward agreement than disagreement. The mean score from each group, based on their level of pronunciation instruction, is 3.45 (SD = 0.47) for NoTraining, 3.43 (SD = 0.42) for MethodCourse+Pronounciation, and 3.50 (SD = 0.61) for PronCourseOnly. A one-way ANOVA demonstrated no statistically significant difference among the three groups regarding their belief in the importance of providing pronunciation instruction, F(2160) = 0.232, p = 0.79, η2 = 0.003.

Concerning specific survey items related to the belief about the importance of pronunciation instruction, participants agreed most strongly that students need to be provided with explicit pronunciation instruction (M = 4.00, SD = 0.99), effective communication requires correct pronunciation, not native-like pronunciation (M = 3.91, SD = 1.17), and students should be provided with different pronunciation varieties of English (M = 3.84, SD = 1.10). Participants also somewhat agreed that learners’ pronunciation issues that do not interfere with communication are lesser priorities for teachers to address (M = 3.42, SD = 1.14).

Confidence in one’s English pronunciation

To address RQ2, participants were queried about their confidence in their English pronunciation. The mean confidence score of all participants is 3.64 (SD = 0.86). The mean score from each group, based on their level of pronunciation instruction, is 3.37 (SD = 0.92) for NoTraining, 3.77 (SD = 0.71) for MethodCourse+Pronounciation, and 3.92 (SD = 0.80) for PronCourseOnly. These results show that all groups indicated they were confident in their English pronunciation. A one-way ANOVA found a statistically significant difference among the three groups regarding their confidence in their English pronunciation, F(2160) = 6.946, p = 0.001, η2 = 0.080. Tukey post hoc test results reveal that the NoTraining participants scored significantly less than the MethodCourse+Pronounciation and PronCourseOnly participants. However, there was no difference in confidence scores between the MethodCourse+Pronounciation and PronCourseOnly participants.

Belief in the sufficiency of training received for pronunciation instruction

To address RQ3, participants were queried about the sufficiency of training they had received for pronunciation instruction. The three items related to this construct were considered separately to answer this research question. The first item asked participants to indicate their level of agreement with the statement I do not have enough background knowledge in teaching English pronunciation. The mean score of all participants for this question is 2.51 (SD = 1.23), with 97 out of 163 (60%) disagreeing or strongly disagreeing with this statement. The mean score from each group, based on their level of pronunciation instruction, is 2.94 (SD = 1.34) for NoTraining, 2.33 (SD = 1.12) for MethodCourse+Pronounciation, and 2.02 (SD = 0.92) for PronCourseOnly. These results show that all groups disagreed with the item, suggesting they believed they had sufficient background knowledge to teach English pronunciation. A one-way ANOVA found a statistically significant difference among the three groups regarding their belief in the level of their background knowledge for teaching English pronunciation, F(2160) = 9.23, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.191. The Tukey post hoc test results reveal that the NoTraining participants believed their background knowledge was less sufficient than did either the MethodCourse+Pronounciation or PronCourseOnly participants. The post hoc testing also shows no significant difference between the MethodCourse+Pronounciation and PronCourseOnly participants regarding their beliefs about their level of background knowledge.

The second item asked participants to indicate their level of agreement with the statement I need training in teaching pronunciation. The mean score of all participants for this question is 3.27 (SD = 1.24), with 81 out of 163 (50%) agreeing or strongly agreeing with this statement. The mean score from each group, based on their level of pronunciation instruction, is 3.39 (SD = 1.30) for NoTraining, 3.25 (SD = 1.12) for MethodCourse+Pronounciation, and 3.11 (SD = 1.27) for PronCourseOnly. These results show that all groups agreed with the item, which suggests they believed they needed more training to teach English pronunciation. A one-way ANOVA found no statistically significant difference among the three groups regarding their belief in the need for training for teaching English pronunciation, F(2,160) = 0.68, p = 0.51, η2 = 0.047.

The third item asked participants to indicate their level of agreement with the statement I need training in assessing pronunciation. The mean score of all participants for this question is 3.35 (SD = 1.25), with 91 out of 163 (56%) agreeing or strongly agreeing with this statement. The mean score from each group, based on their level of pronunciation instruction, is 3.47 (SD = 1.25) for NoTraining, 3.37 (SD = 1.20) for MethodCourse+Pronounciation, and 3.13 (SD = 1.31) for PronCourseOnly. These results show that all groups agreed with the item, which suggests they believed they needed more training to assess English pronunciation. A one-way ANOVA found no statistically significant difference among the three groups regarding their belief in the need for training for assessing English pronunciation, F(2160) = 1.02, p = 0.36, η2 = 0.057.

Practices for effective pronunciation instruction

To address RQ4, the survey contained 10 items asking participants about the nature of their pronunciation instruction. Each item required an answer on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = never, 2 = rarely, 3 = sometimes, 4 = frequently, 5 = always). The results for each question are listed in Table 3.

The findings listed in Table 3 suggest that a majority of the participants used all these practices either sometimes, frequently, or always. For example, 63.2% of the participants reported that they sometimes, frequently, or always provided informative and detailed feedback on their students’ pronunciation. A further examination of these findings for some of these practices indicates that more participants reported never or rarely (40.5%) using the strategies of mouth shape, sagittal section diagrams, audio, or videos for developing pronunciation than did those who used these practices frequently or always (28.2%). Similarly, more participants reported teaching rhythm, stress, and intonation never or rarely (39.9%) than frequently or always (31.9%). However, more participants reported frequently or always as the frequency of use when integrating pronunciation into their instruction (42.9%) compared to never or rarely (18.4%). More participants reported using technology to teach pronunciation frequently or always (44.7%) than those who reported using it never or rarely (31.9%). Finally, many participants reported familiarizing their students with different pronunciation learning strategies frequently or always (42.9%) compared to those who never or rarely did so (25.1%). In comparison, the number of participants who reported explaining the difference between specific sounds in English and Arabic frequently or always (39.3%) exceeded those who reported never or rarely (30.1%) using this practice.

Factors affecting teaching pronunciation

To address RQ5, the survey posed nine items regarding the factors that might impact pronunciation teaching. These nine items were answered on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neither disagree nor agree, 4 = agree, 5 = strongly agree). The results for each question are listed in Table 4.

A synopsis of the results displayed in Table 4 provides evidence that 60.8% of the participants agreed or strongly agreed that there was insufficient time allotted in their course syllabus for teaching English pronunciation, 55.8% agreed or strongly agreed that teaching proper pronunciation requires more instructional time than can be allotted within a course, 55.8% agreed or strongly agreed that the number of students enrolled in their courses hampers their ability to provide sufficient pronunciation instruction, 60.1% agreed or strongly agreed that the technology provided for pronunciation instruction is inadequate, 57.1% agreed or strongly agreed that the students’ passive role in the educative process limits their ability to facilitate productive pronunciation instruction, 57.1% agreed or strongly agreed that providing good pronunciation instruction is difficult due to their students’ low English proficiency level, 55.3% agreed or strongly agreed that their heavy teaching workload did not allow them time to focus on pronunciation instruction, 60.1% agreed or strongly agreed that they believed that their students were made to feel uncomfortable when pronunciation errors were corrected, and 53.3% agreed or strongly agreed that they did not have the resources necessary to provide good pronunciation instruction.

Thematic analysis of the open-ended responses

The qualitative analysis revealed that instructors held varying perspectives on the importance of pronunciation instruction in English language classes. Many instructors (as Participants 2, 9, 11, 13, 14, 19, 22, 28, 32, 35, 36, 40, 41, 43, 49, 152, 156, 157, 158, 159, 161) considered pronunciation as a crucial component of effective communication and prioritized it in their teaching. Other instructors emphasized that incorrect pronunciation can lead to misunderstandings and miscommunications (as Participants 29, 43, 106, 112, 125, 155). They recognized the importance of teaching students to pronounce words accurately to ensure clear and confident expression in English. For example, Participant 29 highlighted how incorrect pronunciation can completely change the meanings of words, underscoring the importance of correct pronunciation for effective communication. Additionally, Participant 82 emphasized the need for students to learn correct pronunciation when introduced to new vocabulary items, as pronunciation plays a vital role in conveying the intended meaning of words. Furthermore, some instructors (as Participants 36, 53, 123) even aimed to help students achieve native-like fluency in English through pronunciation instruction.

Regarding instructional approaches, there are different strategies employed by instructors. Some instructors (as Participants 12, 26, 156, 159, 161) addressed pronunciation when they encountered common mispronunciations among their students. This targeted approach focused on specific pronunciation challenges to provide guidance and correction where needed. Other instructors (as Participants 2, 9, 11, 13, 14, 19, 22, 28, 29, 32, 35, 36, 40, 41, 43, 49, 126, 131, 149) integrated pronunciation as a regular part of their instruction, often as part of a broader emphasis on integrated language skills. For example, participants like Participant 9 mentioned the integration of pronunciation with other language skills. They emphasize a holistic approach to language instruction, incorporating pronunciation alongside other aspects such as vocabulary, grammar, and listening. As Participant 13 explained, “I focus on more than one language skill in my English classes, including pronunciation.” This highlights the belief that pronunciation should be taught in conjunction with other language skills to develop well-rounded language proficiency.

However, it is important to note that not all instructors gave equal weight to pronunciation in their instruction. Some instructors (as Participants 1, 3, 7, 8, 15, 16, 17, 21, 23, 24, 25, 26, 31, 34, 37, 38, 39, 42, 45, 47, 50) did not prioritize pronunciation as much, citing reasons the nature of their course (as Participants 1, 7, 8, 15, 16, 17, 21, 23, 24, 25, 45, 47, 88, 96, 134, 148), lack of time (as Participants 22, 50, 83, 93, 114, 153) not having sufficient knowledge (as Participants 98, 109) or focusing on other skills such as grammar or writing (as Participants 26, 31, 34, 39, 41, 58, 151, 153, 160, 162). Others noted that teaching pronunciation could be an extra load on the students (as Participant 118), and students might feel self-conscious or offended when corrected on their pronunciation (as Participants 8, 41, 90, 147).

Furthermore, certain instructors recognize the presence of diverse English language varieties and demonstrate respect for students’ accents. They assert that learners bear the responsibility of enhancing their pronunciation skills, which can be effectively facilitated through exposure to diverse media and the utilization of various technological resources beyond the confines of the classroom (as Participants 18,153, 162). Other instructors (as Participants 57, 151, 153, 160, 162) acknowledged the importance of pronunciation but recognized that it may not always be feasible to prioritize it in their instruction. Factors such as students’ English proficiency levels or competing instructional objectives influenced their decision.

In summary, while many instructors recognize the importance of pronunciation instruction, their perspectives, approaches, and priorities vary. Some prioritize pronunciation as an integral part of effective communication, while others may not give it equal emphasis due to various factors. The strategies employed range from targeted instruction to integration with other language skills. Understanding these variations provides insights into the complexities of pronunciation instruction in English language classes.

Discussion

This study examined Saudi university EFL instructors’ beliefs about the importance of pronunciation instruction, their confidence in their English pronunciation, the sufficiency of pronunciation instruction training they had received, the practices they used for effective pronunciation instruction, and the factors that affected their teaching of pronunciation.

The findings showed that, overall, the participants agreed with the idea that pronunciation instruction is an integral part of the pedagogy within an L2 course. The results show no statistically significant difference among participant groups based on their level of training about their beliefs of the importance of pronunciation instruction. In contrast, Nagle et al. (2018) found that the participants in their study who had received more training in pronunciation instruction believed more strongly regarding its importance. The difference in this result between these two studies may be an effect of the geographic location where each takes place. It is possible that Nagle et al.‘s American university-based instructors, especially those who lacked sufficient EFL training, are less concerned with the importance of proper pronunciation than might be instructors in expanding circle countries, such as Saudi Arabia. Given that English has become an international language (Boonsuk et al., 2023), it is likely that most Saudi instructors place greater importance on English pronunciation because they realize how it can enhance many personal and professional opportunities (e.g., global communication, career opportunities, travel, cultural appreciation, and personal satisfaction).

The results in this study also showed that participants believed most strongly in helping students to develop correct pronunciation, but not necessarily native-like pronunciation. Similarly, Buss (2016) and Huensch (2019a) found that most of the participants in their studies believed that the primary goal of pronunciation instruction was to improve intelligibility rather than trying to eliminate a foreign accent. It is important to note here that while it is true that some learners may wish to eliminate their foreign accents to sound more like native speakers, this is not always necessary or even possible (Almusharraf, 2021). Trying to eliminate a foreign accent can be a difficult and unrealistic goal, especially for adult learners who may have already developed speech habits that are difficult to change (Almusharraf, 2021).

Results from the current study also suggest that those participants without pronunciation instruction training were less confident in their pronunciation than those who had received training either as part of a methods course or within a course focusing on pronunciation instruction. This result is in line with previous research reporting that having specific training or courses in pronunciation improves one’s confidence in pronunciation (Kochem, 2022; Murphy, 2017; Nagle et al., 2018; Tsunemoto et al., 2023; Uchida and Sugimoto, 2020). Some EFL instructors may feel self-conscious or embarrassed about their pronunciation skills, which can impact their confidence in teaching pronunciation to their students. They may hesitate to correct their students’ pronunciation because they are unaware of the common pronunciation errors made by learners or may not know how to provide accurate and constructive feedback. Instructors may also worry that their students will notice their pronunciation errors or that they will not be able to model correct pronunciation.

Furthermore, as might be expected, those participants with no pronunciation instruction training were not as confident in their background knowledge as those who had received training in a methods course or within a specific pronunciation course. Notwithstanding participants’ confidence in their background, 50 and 56% felt they needed additional training in teaching and assessing pronunciation, respectively. Similarly, Huensch (2019a) found that, among the participants in her study, while 73% were confident in their ability to provide pronunciation instruction, 67% believed they needed further training. Likewise, among the participants in Buss’s (2016) study, 90% indicated they would welcome more training. Further, if training is to be provided, it must offer pronunciation assessment strategies that are robust and valid measures of pronunciation quality. However, such training may not be the norm (Derwing, 2019; Kochem, 2022). As was noted earlier, a majority of the participants in the current study agreed or strongly agreed that they needed training in assessing pronunciation.

Most participants indicated that they regularly used several practices available for teaching pronunciation. Interestingly, the strategies that more participants reported using frequently or always are general strategies that do not necessarily indicate a deep understanding of the sounds of English and the rules that govern their use as the integration of pronunciation within instruction, the use of technology, the application of various pronunciation learning strategies. However, certain practices based on knowledge of areas of linguistics that deal with the sounds of language and their usage, including the use of mouth shape, sagittal section diagrams, audios, and videos and instruction involving rhythm, stress, and intonation (suprasegmentals), were used rarely or never by a 40.5 and 39.9% of the participants, respectively. Huensch (2019b) similarly found that, on average, her participants spent only 12% of their pronunciation-focused instruction on suprasegmentals. By contrast, Buss (2016) found that, on average, her participants utilized 40% of their pronunciation-instructional time to focus on suprasegmentals. Without a solid understanding of English phonetics and phonology, EFL instructors may struggle with helping students improve their pronunciation. It is important to note that a single linguistic or phonology course may not be sufficient to prepare instructors to teach pronunciation. Derwing (2019) suggested providing ongoing explicit pronunciation instruction courses to inform instructors’ practice about teaching pronunciation.

Concerning the integration of pronunciation within FL instruction, Buss (2016) determined that 78.4% of her participants frequently or always undertook integration. The difference between the percentages in the Buss study and the current study may be explained by the fact that, within the interviews that Buss conducted, many of the participants included implicit pronunciation instruction, as well as that explicitly provided, as evidence of integration. In general, the responses to the question about whether the participants normally focus on pronunciation instruction suggest that while there is not necessarily a one-size-fits-all approach to teaching pronunciation in English classes, most instructors in the current study recognized its importance and tried to incorporate it into some way into their instruction depending on various factors such as course goals, student needs, and individual teaching style.

Many participants indicated several factors that negatively affected their ability to provide sufficient pronunciation instruction. These factors included a concern about students’ negative reaction to corrective feedback. Similar to Huensch’s (2019b) and MacDonald’s (2002) findings, over 60% of the participants in the current study were concerned that their students would be made to feel uncomfortable when their pronunciation errors were corrected. Furthermore, another factor that was reported is the lack of focus on pronunciation teaching within the curricula they use. Likewise, previous research specified that the curricula contained very few expectations dedicated explicitly to teaching pronunciation; instead, most of the expectations focused on grammar and lexis (MacDonald, 2002; Pourhosein Gilakjani and Sabouri, 2016).

Moreover, another factor that influenced participants’ ability to undertake pronunciation instruction was the lack of sufficient technology and other resources focusing on pronunciation development. Pourhosein Gilakjani and Sabouri (2016) made a similar discovery; however, it is fortunate that instructors still report such excuses with all the innovative technological developments. With smartphones and mobile devices available for almost all students, instructors can use these devices to access various media and technologies that can be used to supplement classroom instruction, such as online pronunciation guides, mobile apps, and language learning software.

Finally, some participants in the study reported that one of the limiting factors affecting their teaching of pronunciation was the lack of student interest in learning English. According to Gardner (2001), students’ attitude regarding learning a new language influences their success. Participants in the current study also reported that the low level of English proficiency exhibited by incoming students made teaching pronunciation difficult. Instructors within EFL classrooms where students’ level of English proficiency is lower than expected may have to allot more time to acquire proper grammar and lexis, which would lessen the time available for teaching pronunciation.

Implications

The main practical contribution of the study is that it offers evidence that instructors need deeper knowledge in understanding English phonetics and phonology; that is, what speech sounds are and how they are produced, perceived, and represented in language. They also need to be aware of the different approaches to teaching pronunciation and be able to choose the most appropriate approach for their learners’ needs and abilities. Attaining this knowledge may involve taking specialized courses or workshops, attending conferences or webinars, and staying up to date with current research and best practices in teaching pronunciation.

Even though all participants in this study indicated they were confident in their English pronunciation, the NoTraining group scored significantly less than the MethodCourse+Pronounciation and PronCourseOnly participants. Therefore, building EFL instructors’ confidence in their ability to provide effective pronunciation instruction is important, especially among those early in their teaching careers. The most effective way to accomplish confidence-building is through sufficient exposure to the practices of pronunciation instruction during teacher training, courses, and workshops. For example, Echelberger et al. (2018) found that during teacher training using a study circle model, the participants in their study significantly improved in confidence in “their ability to apply research to practice, diagnose issues affecting intelligibility and prioritizing features for instruction, and integrate systematic pronunciation instruction into their ESL classroom lessons and routines” (p. 221).

Instructors also need to be able to provide feedback to learners on their pronunciation. Those incapable of offering effective feedback may be reluctant to correct students’ mistakes and inadvertently reinforce incorrect pronunciation patterns. Therefore, it is crucial to establish well-defined pedagogical priorities for integrating pronunciation activities and rubrics for assessment. Instructors need to be able to access, understand, and correctly apply the assessment frameworks created to identify pronunciation mistakes.

Foreign language instructors must also be comfortable using technology, which can serve as an effective tool for helping learners improve their pronunciation. While almost 70% of the participants in this study reported using technology for teaching pronunciation, 60% reported that the unavailability of technology made it difficult for them to provide pronunciation instruction. Therefore, increasing the availability of technology-enhanced resources for teaching pronunciation in EFL classrooms, and encouraging instructors to make greater use of the available technology, may hold potential benefits for supporting the development of learners’ pronunciation skills. Podcasting, computer-mediated communication, mobile application apps, and multimedia materials are types of technology that might be considered using both high variability phonetic training and low variability phonetic training to improve learners’ perception and production of non-native speech sounds (Almusharraf et al., 2024).

Conclusions

In conclusion, this research makes significant theoretical contributions by providing empirical evidence on university EFL instructors’ beliefs, practices, and influencing factors related to pronunciation instruction. The findings highlight the importance of pronunciation instruction and instructors’ confidence in their own pronunciation skills, while also revealing an evident gap in their training in teaching and assessing pronunciation. The study further explored instructors’ instructional practices and the factors that influenced their decision-making regarding pronunciation instruction. Overall, this research underscores the need for enhanced training and professional development opportunities for Saudi university EFL instructors to improve their ability to deliver effective pronunciation instruction and assessment. Moreover, it highlights the importance of addressing the existing gap between the ideal pronunciation instruction and the current practices in EFL classrooms. By shedding light on these issues, this study contributes to the ongoing discourse on language pedagogy and has the potential to inform policy and practice in Saudi Arabian higher education institutions. These theoretical insights can be generalized to contribute to our understanding of the role of pronunciation instruction in EFL contexts and can inform the development of effective teacher training programs and instructional approaches to enhance pronunciation acquisition among learners.

There are a couple of limitations to the research within the current study. First, although this study’s results are consistent with findings from other studies from different contexts (e.g., Kochem, 2022; Murphy, 2017; Nagle et al., 2018; Tsunemoto et al., 2023; Uchida and Sugimoto, 2020), the study’s sample of Saudi EFL instructors may not be representative enough to generalize the data. Second, the findings from this study rely on self-report data. Self-reporting threatens the validity of research findings because participants may not give an accurate account of reality due to recall bias or social desirability bias. However, this study’s social desirability bias should be considered less problematic because the participants were anonymous. Future research involving classroom observations could add to the knowledge of EFL instructors’ beliefs and practices about pronunciation instruction.

The study highlights the instructors’ confidence in their English pronunciation skills and their perceived lack of training to effectively teach and assess pronunciation. This aspect raises questions about the influence of instructors’ self-perception and identity on their teaching practices. Exploring the relationship between instructors’ identities, language proficiency, and instructional approaches can provide valuable insights into the complex dynamics of language teaching and learning. Finally, there is still a great need for more research investigating how technology can promote pronunciation. It is necessary for future research to explore the mediating role that computer technologies and mobile devices play in advancing L2 pronunciation.

Data availability

Available as supplementary material.

References

Almusharraf A (2021) Learners' confidence, attitudes, and practice towards learning pronunciation. Int J Appl Linguist 32:126–141. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijal.12408

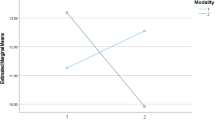

Almusharraf A, Aljasser A, Mahdi HS, Al-Nofaie H, Ghobain E (2024) Exploring the effects of modality and variability on EFL learners’ pronunciation of English diphthongs: a student perspective on HVPT implementation. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11(1):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02632-2

Alghazo S, Jarrah M, Al Salem MN (2023) The efficacy of the type of instruction on second language pronunciation acquisition. Front Educ 8:1182285. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.1182285

Alghazo S, Zidan M (2019) Native-speakerism and professional teacher identity in L2 pronunciation instruction. Indonesian J Appl Linguist 9:241–251. https://doi.org/10.17509/ijal.v9i1.12873

Boonsuk Y, Wasoh F, Waelateh B (2023) Whose English should be talked and taught? Views from international English teachers in Thai higher education. Lang Teach Re. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688231152194

Borg S (2006) Teacher cognition and language education: research and practice. Continuum, London, England

Breitkreutz J, Derwing TM, Rossiter MJ (2001) Pronunciation teaching practices in Canada. TESL Canada journal 51-61. https://doi.org/10.18806/tesl.v19i1.919

Burri M, Baker A, Chen H (2017) I feel like having a nervous breakdown’: pre-service and in-service teachers’ developing beliefs and knowledge about pronunciation instruction. J Second Lang Pronunciation 3(1):109–135. https://doi.org/10.1075/jslp.3.1.05bur

Buss L (2016) Beliefs and practices of Brazilian EFL teachers regarding pronunciation. Lang Teach Res 29(5):619–637. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168815574145

Couper G (2017) Teacher cognition of pronunciation teaching: Teachers’ concerns and issues. TESOL Q 51(4):820–843. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.354

Derwing TM (2019) Utopian goals for pronunciation research revisited. In: Levis J, C Nagle C, Todey E (eds.), Proceedings of the 10th annual pronunciation in second language learning and teaching conference. Iowa State University. pp. 27−35. https://www.iastatedigitalpress.com/psllt/article/id/15363/

Echelberger A, McCurdy SG, Parrish B (2018) Using a study circle model to improve teacher confidence and proficiency in delivering pronunciation instruction in the classroom. CATESOL J. 30(1):213–230. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1174199.pdf

Foote JA, Holtby AK, Derwing TM (2011) Survey of the teaching of pronunciation on adult ESL programs in Canada, 2010. TESL Can J 29(1):1–22. https://doi.org/10.18806/tesl.v29i1.1086

Foote JA, Trofimovich P, Collins L, Urzúa FS (2016) Pronunciation teaching practices in communicative second language classes. Lang Learn J 44(2):181–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/09571736.2013.784345

Gardner RC (2001) Integrative motivation and second language acquisition. In: Dornyei Z & Schmidt R (eds.), Motivation and second language acquisition. Second Language Teaching & Curriculum Center, University of Hawaii. pp. 1–19

Gordon J (2023) Implementing explicit pronunciation instruction: the case of a nonnative English-speaking teacher. Lang Teach Res 27(3):718–745. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168820941991

Huensch A (2019a) Pronunciation in foreign language classrooms: instructors’ training, classroom practices, and beliefs. Lang Teach Res 23(6):745–764. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168818767182

Huensch A (2019b) The pronunciation teaching practices of university-level graduate teaching assistants of French and Spanish introductory language courses. Foreign Lang Ann 52(1):13–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12372

Huensch A, Nagle C (2021) The effect of speaker proficiency on intelligibility, comprehensibility, and accentedness in L2 Spanish: a conceptual replication and extension of Munro and Derwing (1995a). Lang Learn 71(3):626–668. https://doi.org/10.1111/lang.12451

Kochem T (2022) Second language teacher cognition development in an online L2 pronunciation pedagogy course: a quasi-experimental study [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Iowa State University

Lee J, Jang J, Plonsky L (2015) The effectiveness of second language pronunciation instruction: a meta-analysis. Appl Linguist 36(3):345–366. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amu040

Levis JM, Zawadzki Z (2023) New directions in pronunciation research: Previous research as primary data. J Second Lang Pronunciation. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1075/jslp.22049.lev

Macdonald S (2002) Pronunciation—views and practices of reluctant teachers. Prospect 17(3):3–18. https://search.informit.org/doi/abs/10.3316/aeipt.124108

Munro MJ, Derwing TM (2015) Pronunciation fundamentals: evidence-based perspectives for L2 teaching and research. John Benjamins

Murphy JM (2017) Teacher training in the teaching of pronunciation 1. In: Kang O, Thomson RI, Murphy JM (eds.) The Routledge handbook of contemporary English pronunciation. Routledge. pp. 298−319

Nagle C, Sachs R, Zárate-Sández G (2018) Exploring the intersection between teachers’ beliefs and research findings in pronunciation instruction. Mod Lang J 102(3):512–532. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12493

Nagle C, Sachs R, Zárate-Sández G (2020) Spanish teachers’ beliefs on the usefulness of pronunciation knowledge, skills, and activities and their confidence in implementing them. Lang Teach Res 27(3):491–517. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168820957037

Pennington MC (2021) Teaching pronunciation: The state of the art 2021. RELC Journal 52(1):3-21. https://doi.org/10.1177/00336882211002283

Pourhosein Gilakjani A, Sabouri N (2016) Why is English pronunciation ignored by EFL teachers in their classes? Int J Engl Linguist 6(6):195–208. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijel.v6n6p195

Saito K, Plonsky L (2019) Effects of second language pronunciation teaching revisited: A proposed measurement framework and meta‐analysis. Lang Learn 69(3):652–708. https://doi.org/10.1111/lang.12345

Saito Y, Saito K (2017) Differential effects of instruction on the development of second language comprehensibility, word stress, rhythm, and intonation: The case of inexperienced Japanese EFL learners. Lang Teach Res 21(5):589–608. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168816643111

Tsang A (2021) EFL listening, pronunciation, and teachers’ accents in the present era: An investigation into pre- and in-service teachers’ cognition. Lang Teach Res. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688211051981

Tsunemoto A, Trofimovich P, Kennedy S (2023) Pre-service teachers’ beliefs about second language pronunciation teaching, their experience, and speech assessments. Lang Teach Res 27(1):115–136. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168820937273

Uchida Y, Sugimoto J (2020) Non‐native English teachers’ confidence in their own pronunciation and attitudes towards teaching: a questionnaire survey in Japan. Int J Appl Linguist 30(1):19–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijal.12253

Yadav A (2023, January 10) English language statistics. Lemon Grad

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AA is the sole author of this work. She was responsible for all aspects of this research project, including the initial conceptualization and planning, literature review, data collection and analysis, writing the original draft, and reviewing and editing the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The research methodology employed in this study was reviewed and approved in accordance with the institutional review board (IRB) policies and procedures of Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU). The IRB approval number (70785) was granted on September 10, 2022.

Informed consent

Prior to data collection, informed consent was obtained from all participants. Each individual was provided with information regarding the purpose of the study, their rights as participants (including the right to withdraw at any point), and the measures taken to protect their personal data. Participants gave their consent to participate voluntarily.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Almusharraf, A. Pronunciation instruction in the context of world English: exploring university EFL instructors’ perceptions and practices. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 847 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03365-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03365-y