Abstract

Because non-pharmaceutical interventions are an essential part of pandemic influenza control planning, the complex impacts of such measures must be clearly and comprehensively understood. Research has examined the health and environmental effects of non-pharmaceutical interventions, but has not yet examined their socio-political effects. Using data from the COVID-19 pandemic period, this article examined the impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions on people’s online participation in China in 2020. Using the difference-in-differences method, it showed that counter-COVID-19 non-pharmaceutical interventions in Chinese cities led to a 0.217 increase in daily messages to City Party Secretaries, which were consistent with findings of an alternative counterfactual estimator and other additional robustness tests. The effects of non-pharmaceutical interventions were larger in cities with better economic conditions, better telecommunication foundations, and better-educated residents. Mechanism analyses implied that the increase in online participation resulted from not only citizens’ increased actual demand for seeking help and expressing thanks but also their active coproduction activities to address the crisis. Overall, this study identified the socio-political effects of counter-pandemic non-pharmaceutical interventions and discussed how these interventions could be optimized.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The worldwide COVID-19 forced many countries to adopt a variety of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to increase social distance and limit individual movement. Such interventions have included curfews, restrictions on travel and transportation, school closures, suspension of recreational or commercial activities, and even full-scale national lockdowns (Anderson et al., 2020; Chinazzi et al., 2020; Soucy et al., 2024; Wells et al., 2020). NPIs have profoundly impacted natural ecosystems and human societies while flattening the COVID-19 curve (Block et al., 2020; Cao et al., 2020). Regional and global data show that counter-COVID-19 NPIs improved air and water quality (Braga et al., 2020; Le et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2020), reduced underwater and seismic noise (Lecocq et al., 2020; Thomson and Barclay, 2020), and delivered significant environmental benefits. The massive stagnation of human activity under COVID-19 has led to a decline in global economy, supply chains, and maritime transport (Guan et al., 2020; March et al., 2021), structural changes in mobile networks (Schlosser et al., 2020), and worsening economic, health, and racial inequalities (Bambra et al., 2020; Goudeau et al., 2021). In general, various effects of these interventions at the macro level have been widely examined and confirmed.

At the micro level, these NPIs have also caused significant shifts in people’s lives. The increase in social distance and self-isolation has affected people’s mental health, personal behavior, and lifestyle patterns, shifting their perception of time, sleep habits (Cellini et al., 2020), dietary interests (Di Renzo et al., 2020; Gligoric et al., 2022), and exercise habits (Hunter et al., 2021). However, these studies have mainly focused on the impacts of NPIs on the behavior and personal lives of individuals. In fact, it is also possible that NPIs can change individuals’ political behaviors, particularly their online participation. When cities are locked down, it is nearly impossible for citizens to apply for public services via offline channels. In such cases, individuals’ interactions with the government are shifted online. While identifying the impacts of counter-COVID-19 NPIs on personal online participation behaviors could increase our understanding of government-citizen relationships, there has been little research on people’s online interactions with governments during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Timely and effective communication and interaction between governments and individuals has proven to be one of the most critical tools in containing the spread of COVID-19 (Haug et al., 2020). Online interaction can provide people in COVID-19 isolation with an almost exclusive channel of information communication exchange, which compensates for the adverse effects of reduced traditional social interaction due to increased physical and social distancing (Goudeau et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2020). For example, interactions with the government and access to authoritative information can alleviate the isolation, insecurity, and anxiety caused by COVID-19 and NPIs implementation, which had serious detrimental effects on individuals’ mental health (Pierce et al., 2020; Rossi et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2022). From an analysis of 8 million helpline calls from 19 countries, Bruelhart et al. (2021) pointed out that pandemic-related issues replaced, rather than exacerbated, underlying anxiety.

The NPIs implemented by governments were very complex. For instance, Chile implemented two sets of separate NPIs to contain the contagion in just two months (Gozzi et al., 2021). The complicated and varying nature of NPIs made it more difficult for citizens to understand them. However, people’s understanding and willingness to comply are critical to the effectiveness of the NPIs (Galasso et al., 2020). Therefore, timely and efficient communication and interaction between individuals and the government is important. Furthermore, for key stakeholders such as managers and healthcare professionals, interaction with the government could improve their understanding and use of safety guidelines and protocols, which could play a crucial role in controlling COVID-19 (Haug et al., 2020).

Beyond health, the COVID-19-induced increase in online interaction between individuals and governments is also of socio-political importance. Individual-government online communication and interaction is a basic form of online participation (Medaglia, 2012). In the digital age, online participation has received widespread attention as an independent mode of political participation different from traditional offline participation (Gibson and Cantijoch, 2013; Oser et al., 2013; Sæbø et al., 2008). Especially for groups such as youth and women who are disadvantaged in the formal participation process, online participation is a more convenient channel (Ruess et al., 2021; Theocharis et al., 2021; Vissers and Stolle, 2014). Existing research on the factors influencing online political participation has focused on two main lines of inquiry. The first is whether factors such as socio-economic status, educational status, and social network ties that influence traditional offline participation are predictive of individuals’ online participation behavior (Valenzuela et al., 2012; Vicente and Novo, 2014). The second line of research has focused on online attributes. Individual digital skills and social media usage, government media use patterns, and the degree of e-government development are core variables of interest in this area (Bonsón et al., 2015; Gil de Zúñiga et al., 2015; Hargittai and Shaw, 2013). Research on individual online participation behavior has been confined to the political science arena and less examined the potential impact of exogenous shocks such as emergencies. COVID-19 opens a window to examine changes in individual online participation patterns in extraordinary circumstances.

This study examined how NPIs implemented to control COVID-19 affected individual–government interactions across China’s cities. We focused on individual online participation behavior in Chinese cities for two reasons. First, China was affected by COVID-19 early and was one of the first to use NPIs (Chen et al., 2020; Kucharski et al., 2020). In 2020, nearly half of Chinese cities implemented NPIs of varying degrees in a top-down manner, providing a rich and appropriate sample for our study. Second, most studies on individual online participation have focused on developed regions, such as Europe and the USA, and less on developing countries (Bonsón et al., 2015; Gil de Zúñiga et al., 2015; Hargittai and Shaw, 2013). The case of China, the world’s largest developing country, can address this research gap. In addition, compared with Western democracies, China’s unique political and cultural context leaves much room for improvement in individual online participation (Zhang and Lin, 2014). Therefore, if NPIs significantly increased online participation by Chinese citizens, the implied social and political effects would be more significant.

Using a comprehensive dataset at the day-by-city level from January 1 to December 31, 2020, we used a difference-in-differences (DiD) model to quantify the effect of NPIs on individual online participation levels. The DiD model treats cities without NPIs as counterfactuals, mimicking what would happen in the treated cities if NPIs were not implemented. The results of the DiD model and robustness tests indicated that NPIs' implementation significantly increased individuals’ online participation levels. Furthermore, to avoid the many confirmed drawbacks of the DiD model in empirical studies (Blackwell and Glynn, 2018; Imai and Kim, 2019; Sun and Abraham, 2021), we drew on the interactive fixed effects counterfactual estimators (IFEct estimators) proposed by Liu et al. (2020) and validated our findings again. We did the heterogeneity analysis to find that the effects of NPIs were larger in cities with better economic conditions, better telecommunication foundations, and better-educated residents. Besides, we conducted the mechanism analyses to confirm that the increase in online participation resulted from not only citizens’ increased actual demand for seeking help and expressing thanks but also their active coproduction activities to address the crisis. The former implied that governments could use online platforms to collect information on citizens’ demands and increase governments’ responsiveness during crises, while the latter meant citizens also made voluntary efforts to enhance governance quality through online participation (Brudney and England, 1983). Overall, our results further clarify the impact of NPIs implemented in response to large-scale pandemics and provide an essential perspective on how people’s online participation behavior can change in extraordinary situations.

Data and variables

Online participation

We used the number of daily messages received by City Party Secretaries on China’s online political platform, the Local Leadership Message Board (LLMB), to measure the level of individual online participation (Wang et al., 2020; Zheng et al., 2021). We used LLMB data for two reasons. First, the LLMB is China’s first and unique nationwide online political platform supported by the official online media (people.cn) and open to all. Since its inception in 2008, the LLMB has attracted widespread attention (Su and Meng, 2016), and it provides an authoritative vehicle for online participation by Chinese citizens (Teng and Guo, 2022). Second, because it is a nationwide official platform, LLMB data are not controlled by local governments, so they are transparent and can accurately reflect interactions between local governments and individuals across the country in a timely, adequate, and objective manner.

We used a Python crawler to collect 108,981 messages received by City Party Secretaries in 2020 in 323 cities on the LLMB, excluding Hong Kong, Macau, Taiwan, and other cities where all messages in the study area were unavailable. The time span was January 1, 2020, to December 31, 2020. To create the day-by-city-level online participation dataset, we aggregated messages according to when they were posted.

Counter-COVID-19 NPIs

The implementation of NPIs in cities was checked by combining the official websites of each city government, announcements of the city’s Department of Transport, notifications of city bus companies, passenger transport companies, and other news media reports. Most cities had a counter-pandemic policy issued directly by the local municipal government or the provincial government. The extent to which NPIs were implemented varied between cities. Some cities adopted strict NPIs, where residents were forbidden to go out, and all public places were closed. They were effectively under lockdown. Other cities had relatively flexible policies, allowing citizens to move freely within city boundaries.

From our examination of NPIs implementation, we designated a city as implementing strict NPIs if all the following three policies were enforced (Block et al., 2020; He et al., 2020): (1) prohibition of any congregation by residents; (2) restrictions on intercity traffic and individual movement (travel restrictions); and (3) restrictions on intra-city traffic and individual movement. Supplementary Table 1 lists cities that imposed strict NPIs in 2020 and the date that NPIs became operational.

The severity of local COVID-19

The implementation and stringency of NPIs are highly correlated with the severity of the local pandemic, while the current and historical status of a city’s COVID-19 is also likely to influence the level of people’s online participation. Therefore, we added the severity of local COVID-19 as the control variable to our model to accurately measure the impact of NPIs implementation on individual online participation levels. Local COVID-19 severity data included five variables: newly confirmed cases, new deaths, current confirmed cases, cumulative confirmed cases, and cumulative deaths. Combining data from the Sina Real-time COVID-19 Pandemic Data Platform, provincial and city governments’ pandemic information announcements, and the daily pandemic data of provincial and city health commissions, we created a day-by-city-level local COVID-19 severity dataset.

Summary statistics

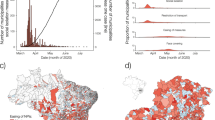

We report summary statistics of online participation and local COVID-19 severity variables for the sample period in Table 1. We also present temporal trends in citizens’ online participation in Fig. 1. The average number of daily messages received by City Party Secretaries for all cities was 0.922, with a standard deviation of 1.897. For the treated cities (cities with NPIs), their City Party Secretaries’ average number of daily messages was 0.932 (standard deviation of 2.145) before the COVID-19 government interventions and 1.074 (standard deviation of 2.172) after they adopted NPIs. We saw an increase in the level of individual online participation in the treated cities after NPIs implementation.

Models

DiD model

We evaluated the impact of counter-COVID-19 interventions on individual online participation using the DiD model (He et al., 2020). We chose this method because it was the most widely used policy evaluation approach based on the counterfactual framework (He et al., 2020; Lin et al., 2021; Zhang, 2019; Zhang and Zhang, 2023; Zhang et al., 2023), which allowed us to control for potential confounding factors related to citizens’ online participation and to estimate the causal effects of NPIs. The model we used is as follows:

where \({Y}_{{it}}\) is the number of messages received by the City Party Secretary of city i on date t, which represents individual online participation in city i on date t. \({{{\rm {NPIs}}}}_{{it}}\) is a dummy variable indicating whether counter-COVID-19 NPIs were implemented in city i on date t and takes the value of 1 if it implemented NPIs and 0 otherwise. \({X}_{{it}}\) represents a vector of controls describing the severity of local COVID-19, including five variables: newly confirmed cases, new deaths, current confirmed cases, cumulative confirmed cases, and cumulative deaths. \({\mu }_{i}\) and \({\pi }_{t}\) indicate city-level and date-level fixed effects, and \({\varepsilon }_{{it}}\) denotes disturbance errors.

After controlling for both city and date fixed effects, \(\beta\) estimates the difference in individual online participation levels between the treated (those with NPIs) and control cities (those without NPIs) before and after the enforcement of COVID-19 government interventions. People’s access to offline interaction was severely restricted in the treated cities. Online participation became effectively the only channel for people to communicate with the government, obtain authoritative information, alleviate their insecurity and anxiety, and resolve practical challenges. Therefore, we expected \(\beta\) to be positive; i.e., NPIs implementation increased people’s online participation.

The assumption underlying the validity of the DiD model is that in the absence of these interventions, the treated and control groups would not show significant differences in the time-varying trends of individuals’ online participation levels. In other words, the trends in the number of messages from the two city groups should be parallel during the pre-treatment period. Thus, we used an event study design (Jacobson and LaLonde, 1993) to determine the comparability between treated and control cities. The model is shown below (He et al., 2020; Lin et al., 2021):

where \({{{\rm {NPIs}}}}_{{it},k}\) is a vector of dummy variables denoting NPIs implementation status at each timepoint. The variable for m = −1 is not in Eq. (2) because the day immediately prior to an intervention is the reference group. Thus, \({\beta }^{k}\) indicates the policy effects relative to the day immediately before an intervention (k = −1) at k days after policy implementation. Supposing that the treated and control groups are paralleled, there should be no systematic difference in civic online participation levels between these two groups before the policy was implemented (k ≤ −2); i.e., \({\beta }^{k}\) should not be significant when k ≤ −2. After the counter-pandemic policy was implemented (k ≥ 0), the difference between the levels of civic network participation of the two groups would gradually become more pronounced, so \({\beta }^{k}\) should progressively become greater than 0 when k ≥ 0.

IFEct estimator

To avoid the many confirmed drawbacks of the DiD model in empirical studies, we re-estimated the policy effect on online civic engagement using the following model (Liu et al., 2020):

Following Liu et al. (2020), the treated cities L and the control cities N were divided according to \({{NPIs}}_{{it}}\), which means that \(N=\{(i,t)| {{NPIs}}_{{it}}=0\}\) and \(L=\{(i,t)| i\in {\rm T},{{NPIs}}_{{it}}=1\}\). \({Y}_{{it}}(1)\) is the number of LLMB messages in the policy intervention state, and \({Y}_{{it}}(0)\) is the number of messages in the non-intervention state. \(f\left({X}_{{it}}\right)\) is the parametric function of the control variables (\({X}_{{it}}\)), which represents the potential impact of observable control factors on the level of individual online participation. \(h\left({U}_{{it}}\right)\) is the parametric function of the unobservable attributes (\({U}_{{it}}\)), including city-level and date-level fixed effects, and heterogeneous effects of time trends.

According to the illustration of Liu et al. (2020), this method involved the following estimation strategy: First, for all control cities, there exists \({Y}_{{it}}\left(0\right)=f({X}_{{it}})+h({U}_{{it}})+{\varepsilon }_{{it}}\). Therefore, the data from the control group is used in Eq. (3) to obtain \(\hat{f}\) and \(\hat{h}\). Second, we use \(\hat{f}\) and \(\hat{h}\) to estimate the counterfactual outcome \(\hat{{Y}_{{it}}}(0)\) of each treated city. Third, for each treated city, we use the difference between its observed outcome \({Y}_{{it}}\) and its counterfactual outcome \(\hat{{Y}_{{it}}}(0)\) to estimate the treatment effect. Fourth, we average the treatment effects for each treated city to obtain the average policy effect.

Results

Impacts of counter-COVID-19 NPIs on online participation

Following Eq. (1), we identified the change in online participation in cities with NPIs relative to cities without NPIs. We found that the implementation of counter-COVID-19 NPIs did increase citizens’ online participation (Table 2). Specifically, compared with cities without NPIs, the number of daily LLMB messages received by City Party Secretaries in the treated cities increased by 0.166 when controlling for local COVID-19 severity variables, city-fixed effects, and date-fixed effects (Model 2), representing about 18 percent of the average number of daily messages received by City Party Secretaries (0.932, Table 1) in 323 Chinese cities in 2020. Furthermore, the results of Model 4 indicated that the treatment effect of NPIs remained robust when we used the logarithm of messages as the dependent variable.

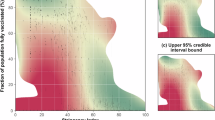

Using an event study approach, we investigated the validity of the parallel trend assumption by estimating the trend in the level of people’s online participation in these two groups before and after NPIs. Figure 2 plots our findings. Comparing the level of online participation between these two groups in Fig. 2, there was no significant difference between these two groups in the number of messages received by the City Party Secretaries when \(-3\le k\le -2\), validating the parallel trend assumption. However, this parallel trend was violated after the introduction of NPIs (\(k > 1\)), and the difference between the two groups became increasingly significant with a positive coefficient after NPIs. Moreover, the gap between treated and control groups before NPIs declined gradually, while their gap after NPIs rose gradually over time, further indicating that NPIs increased people’s online participation.

Although the DiD model has been widely used to assess policy effects, researchers have shown that the two-way fixed effects model that it is based on has shortcomings that can lead to biased causal inferences (Blackwell and Glynn, 2018; Imai and Kim, 2019). The parallel trend assumption of the DiD model relies on parametric assumptions, which could also produce potentially misleading results (Sun and Abraham, 2021). In addition, each city’s policies were implemented and removed at different times. This complex situation of policy change could constrain the validity of two-way fixed effects model in policy evaluation. Therefore, we used the IFEct estimator to accurately evaluate the impact of counter-COVID-19 government interventions on citizens’ online participation by constructing counterfactuals for the treated cities using data from the control cities. This approach provides more robust causal inferences than traditional models in cases when heterogeneous treatment effects and unobserved time-varying confounders exist (Liu et al., 2020).

Intuitively, it makes sense to use only the data from the control cities to construct the counterfactuals for the treated cities if there is no systematic difference in online civic participation between these two groups in the absence of policy intervention. Therefore, we first used a placebo test to demonstrate the feasibility of this method. Specifically, we used samples from one week before NPIs implementation in two placebo tests: the equivalence test (TOST) and the difference-in-means test (t-test). The TOST test assumes that the average treatment effect over this period is well beyond the equivalence range, and the t-test assumes that the average treatment effect is close to 0. If the null hypothesis of the TOST test is rejected and the null hypothesis of the t-test is accepted, the treated and control cities had similar levels of citizen online participation in the week prior to NPIs implementation, and the IFEct estimator is valid. Table 3 presents the placebo test results. Using one week prior to NPIs implementation in the treated cities as our research period, the p-value (0.000) of the TOST test was less than 0.05, while the p-value (0.177) of the t-test was >0.1. The results indicated no systematic difference in online civic participation between these two groups in the absence of policy intervention, demonstrating the validity of our IFEct estimator.

The main results showed that people’s online participation increased significantly after a city-enforced counter-COVID-19 NPIs (Table 4). We found that the treated cities had 0.743 more actual messages than the counterfactual estimates constructed using data from the control cities when we controlled for the local COVID-19 severity variables, city fixed effects, date fixed effects, and a time-varying confounder in Model 6. Furthermore, the results were not significantly different from the policy effects estimated using the DiD model, suggesting that our main findings were reliable.

Additional robustness tests analyses

Additional analyses were conducted to verify the robustness of results above. First, we used a placebo test of the DiD model (La Ferrara et al., 2012; Song et al., 2019) to avoid potential influences of unobservable omitted variables. We used a randomly generated treated group to estimate the fake treatment effect and repeated this process 1000 times. We found that the 1000 fake coefficients followed a normal distribution around 0 (see Fig. 3). This implied that the significant treatment effect of the NPIs was not accidental, and this result supported the validity of our findings.

Second, to exclude the potential interference of extreme values on our findings, the core dependent variable of the number of LLMB messages received by City Party Secretaries was again winsorized at the 1% and 5% levels. We rerun the DiD models, and all results were similar (Table 5), again validating our findings on the policy effect of counter-pandemic NPIs.

Third, the timing of policy interventions across all treated cities (Supplementary Table 1) showed that most treated cities implemented and then dropped their NPIs in the first six months of 2020, while only a few cities implemented NPIs in the latter half of 2020. Therefore, we used data from the first wave of the pandemic in 2020 (January 1, 2020 to May 31, 2020) to again estimate the policy effects (Wang et al., 2022). The new results reconfirmed the impact of NPIs for the first round of COVID-19 on people’s online participation (Models 11 and 12 of Table 6).

Fourth, to re-examine the robustness of our findings, we assessed the policy effects in depth using a sample covering the period prior to the Spring Festival (January 1, 2020 to January 24, 2020). Before the Spring Festival, only several cities in and around Wuhan had adopted NPIs, and others had not taken measures to curb the COVID-19 pandemic. This approach provides us with a “cleaner” control group to analyze the effect of counter-COVID-19 NPIs. The results were again similar and are shown in Models 13 and 14 of Table 6. Additionally, we excluded the 2020 Spring Festival period from our sample to avoid the potential impact of this holiday on citizens’ online participation. The results of these analyses supported the robustness of our main findings (Models 15 and 16 of Table 6).

Fifth, although NPIs that severely restrict population movement and social distance can play important roles in containing the spread of COVID-19 (Anderson et al., 2020; Block et al., 2020), their significant negative economic and social impacts cannot be ignored (Bonaccorsi et al., 2020; Guan et al., 2020). Actually, many governments adopted tiered restrictions on human activities based on COVID-19 situations to avoid the challenges of blindly applying strict restrictions in a post-lockdown world (Manica et al., 2021). During infectious disease outbreaks, partial restrictions on population movements are more common forms of control than strict measures such as full-scale national lockdowns. Therefore, analysis of these interventions is more valuable (Bell et al., 2006). Even in China, where COVID-19 control has been significant, strict NPIs have been very short-lived, and more relaxed interventions have been more common. Therefore, we relaxed the definition of government intervention to re-assess the policy impact of relaxed counter-COVID-19 NPIs.

Specifically, we defined a city as implementing relaxed NPIs if the following two indicators were enforced: (1) prohibition of social gatherings and (2) restrictions on intercity traffic and individual movement (travel restrictions). In contrast to strict interventions, in this setting, people can move freely within their city. The results (Models 17 and 18 in Table 7) indicated that these relaxed policies also contributed to increased levels of individual online participation and that this policy effect was more significant than in our baseline regressions. This result could be attributed to the gradual implementation of government interventions. At the beginning of the pandemic, most cities only restricted the movement of people from a few cities with severe outbreaks (e.g., Wuhan). As the pandemic spread across the country, the government began to take stricter measures, such as restricting interprovincial and intercity transport and individual movement. Ultimately, the government adopted severely restrictive measures such as city lockdowns. Thus, the implementation of relaxed NPIs in the early stages of the pandemic reduced the impact of later, stricter interventions on citizens’ online participation levels.

Sixth, within this policy framework, we also considered mayors’ LLMB messages. In China, the City Party Secretary, as the highest leader of the Chinese Communist Party at the city level, plays a pivotal role in the municipal governance process (Ru and Zou, 2022). On the LLMB, the number of messages received by mayors (59,716) was much smaller than the number of messages received by City Party Secretaries (108,981). However, as the critical administrative head of local government, mayors should still be taken seriously. Therefore, we used the sum of LLMB messages received by City Party Secretaries and mayors as a new dependent variable to further evaluate the impact of NPIs on citizens’ online participation. The regression results (Models 19 and 20 Table 7) showed that these interventions increased the number of messages received by both City Party Secretaries and mayors, again confirming their positive impact on online civic engagement. We compared the messages to City Party Secretaries and mayors and found that they were highly correlated. Supplementary Tables 2-1 and 2-2 implied there were nearly no differences between the distribution of messages received by City Party Secretaries and mayors.

Heterogeneity analysis

We tested whether the treatment effect of NPIs varied among cities with different characteristics. Specifically, we tested whether the effects were heterogeneous across cities with (1) different economic conditions, (2) different telecommunication foundations, and (3) different educational levels of residents. GDP per capita was the proxy for economic conditions, and we calculated it by dividing GDP by the total population; The telecommunication foundation was measured as the ratio of total mobile phone subscribers to the total population; The educational level of residents was estimated as the ratio of resident population with a college degree to the total resident population. These city-level statistics were taken from the 2020 China City Statistical Yearbook, the 2020 National Economic and Social Development Statistical Communiqué of cities, and the Seventh National Population Census Report of cities. We used the mean value of each variable to divide all cities into two groups. For example, if a city’s GDP per capita was over the mean value of GDP per capita of all cities, we defined this city as one with a high economic condition. Then, we rerun models using each subsample (see Table 8).

First, we found that the treatment effect of NPIs was statistically significant in cities with better economic conditions (0.467, p < 0.05; 0.327, p < 0.05; 0.115, p < 0.05; 0.102, p < 0.05), while the effect of NPIs was not significant in cities with worse economic conditions (0.040, p > 0.1; −0.028, p > 0.1; 0.017, p > 0.1; 0.005, p > 0.1). This result supports the argument that NPIs may be more disruptive to normal functioning in developed economies with more active economic activities (Bonaccorsi et al., 2020; Gozzi et al., 2021), which may lead to a higher level of citizens’ online participation. In addition, it is consistent with the conclusions that rapid economic development can drive citizens’ participation (Paik, 2012).

Second, the results confirmed that NPIs had larger influences in cities with better telecommunication foundations (0.294 > 0.134; 0.144 > 0.005; 0.072 > 0.037; 0.055 > 0.013). The reasons were two-fold. On the one hand, the better telecommunication foundation implied a higher rate of subscription to electronic communication equipment, providing a stronger basis for citizens’ online participation. On the other hand, higher assimilation of electronic communication equipment implied residents’ higher digital skills and more frequent internet usage, which could also drive citizens’ online participation (Gil de Zúñiga et al., 2015; Hargittai and Shaw, 2013).

Finally, we found that the effect was more significant in cities with more well-educated residents. Treating socio-political participation as an activity with costs, the resource theory emphasizes that people with more resources (e.g., higher socio-economic status and better education background) are more likely to engage in participation (Marien et al., 2010; Vicente and Novo, 2014). The reinforcement effect argued that the internet would reinforce offline participation activism (Nam 2012), and socio-economically advantaged and well-educated persons were also highly active in online participation (Krueger, 2006; Lee and Kim, 2018). Thus, our findings were in accordance with the reinforcement hypotheses in participation research.

Mechanism analysis

Mechanism analysis was conducted to explore why citizens engaged in online participation under NPIs. According to the regulation of the LLMB, citizens had to categorize their messages into one of the following five types: seeking help, consulting, providing suggestions, expressing thanks, and complaining. Different message types reflect different citizens’ demands, and the distribution of different types of messages could shed light on why NPIs boost citizens’ online participation. We argued that two mechanisms could explain the NPIs’ impact on online participation: inconvenience in daily life and coproduction behaviors in response to the crisis. On the one hand, if citizens engaged in participation because of the inconvenience in daily life, we expected citizens would submit more messages in the following three categories: seeking help, consulting, and expressing thanks. On the other hand, citizens’ coproduction behaviors indicate individuals’ voluntary efforts to enhance service and governance quality (Brudney and England, 1983). Messages of providing suggestions and complaining could be figured as citizens’ inputs into governance, and thus, we expected citizens would submit more messages in these two categories if they engaged in coproduction behaviors in response to the crisis.

Table 9 reported the results of the impacts of NPIs on each type of message. First, the coefficients of NPIs on messages of seeking help were significantly positive (0.126, p < 0.05; 0.094, p < 0.1), which means citizens tended to seek help from the government more frequently after the implementation of NPIs. Besides, the coefficients of NPIs on messages of expressing thanks were also positive and significant (0.006, p < 0.05; 0.006, p < 0.05), implying citizens tended to express more thanks to the government during the implementation of NPIs. According to the results, we can make the following inferences: the inconvenience caused by NPIs drove citizens to seek help from the government, while the government’s help for citizens also made citizens grateful. Thus, citizen’s increased actual demand boosted their online participation. This also implies that online platforms improved governments’ capacity to understand citizens’ needs and increased their responsiveness to citizens’ demands during crises.

Second, NPIs led to a significant increase in messages providing suggestions, supporting the second mechanism of promoting coproduction behaviors. Compared with control cities, the number of messages to provide suggestions in the treated cities significantly increased by 0.053 pieces when local COVID-19 severity variables, city-level and date-level fixed effects were controlled. This result suggests that citizens tended to engage in coproduction behaviors by providing suggestions, contributing to an overall increase in online participation. Previous research has shown that governance issues that directly affect people’s lives increase their engagement (Bonsón et al., 2015). Because COVID-19 and the implementation of NPIs affected citizens’ lives directly, citizens provided suggestions for government leaders to help them deal with the crisis.

In addition, the LLMB also divided the topics of messages into more than ten fields: transportation, healthcare, administration, security, travel, construction, environment, education, finance, employment, company, agriculture, entertainment, and others. After text analysis of the messages, we found significant differences in the content of LLMB messages at different stages. Briefly speaking, there were significant increases in messages in the fields of transportation, healthcare, and administration in the stages of NPIs (see Supplementary Table 3). This change suggested that the challenges posed by restrictions on individual movement and the reduction of activities became a major concern during this period. Besides, because messages of administration emerged, citizens also became more concerned about governance. Thus, these trends were also in accordance with the two mechanisms discussed above (see Fig. 4).

Discussion and conclusion

Summary

NPIs designed to reduce person-to-person contact have long played an essential role in pandemic influenza planning (Bell et al., 2006). Their contribution to controlling the pandemic is widely recognized (Cauchemez et al., 2008; Markel et al., 2007). However, the socio-economic challenges of these population-level interventions and their profound effects on people’s lifestyles must be considered. A full and clear understanding of the complex effects of NPIs is essential to enable policymakers to effectively respond to ongoing pandemics and better prepare for future outbreaks.

The 2020 worldwide COVID-19 provides a useful case study in this regard. Using a comprehensive dataset at the day-by-city level in 2020, we quantified the impact of counter-COVID-19 NPIs on people’s online participation. We found that NPIs substantially increased individual online participation, a critical form of government–public interaction. Online participation can help people relieve their psychological stress, solve practical dilemmas, and improve their policy understanding and compliance, all of which are crucial to preventing and controlling pandemics. Moreover, we found that the impact of NPIs on online participation was greater in cities with better economic conditions, better telecommunication foundations, and higher education levels of residents. These findings highlighted the important role of the resources, telecommunication infrastructure, and citizens’ digital skills in promoting online participation.

This study also shed light on why the NPIs could increase citizens’ online participation. The differential effects of NPIs on different types of messages implied two possible mechanisms. First, the mechanism analysis showed that messages of seeking help and expressing thanks increased significantly. This meant increased actual demand was the key reason for increased online participation, which implied that the implementation of NPIs disrupted the citizens’ normal travel and caused inconvenience in people’s lives. The frequent online government-citizen interactions also supported governments’ strong online responsiveness to citizens’ demands during crises in China. Second, we found that citizens were also actively involved in crisis governance, particularly through providing suggestions. This meant the NPIs also made citizens aware of the severity of the crisis and stimulated them to work with the government to deal with the crisis. Thus, it is important to encourage the coproduction behaviors of citizens in response to future crises.

Comparing the trends in online participation levels between the treated and control groups, we found that citizens’ online participation peaked approximately three weeks after the interventions were implemented (see Fig. 1). Previous studies of hotline calls have shown that calls peaked approximately six weeks after the COVID-19 wave (Brülhart et al., 2021). Similarly, our results suggest that people’s tolerance of NPIs has a time threshold, in this case about three weeks. If the implementation of interventions exceeds this threshold, the ensuing adverse effects of the policy, such as life difficulties and psychological stress, become more pronounced. Moreover, NPIs have shown a marginal trend of diminishing policy benefits in pandemic control (Hatchett et al., 2007). Hence, to avoid the harmful effects of long-term restrictions on population mobility and social distancing, the timing of strict NPIs implementation should be controlled. Governments should adjust their interventions promptly according to changes in the epidemiological situation.

Policy implications

Our finding that the NPIs led to greater online participation is also of socio-political importance. First, it demonstrates the critical influence of exogenous shocks on citizens’ online participation behavior, demonstrating that such participation is not only driven by factors such as ability and resources (Hargittai and Shaw, 2013; Valenzuela et al., 2012) but also by real needs. This is also supported by evidence from Western Europe (Bonsón et al., 2015). Second, although online participation has been identified as separate from offline participation (Gibson and Cantijoch, 2013; Oser et al., 2013), the relationship between these two forms needs to be further explored. Our conclusions demonstrate that online and offline participation are not necessarily mutually exclusive but rather symbiotic and complementary (Rodríguez-Estrada et al., 2020; Shah et al., 2005). Online participation can provide an additional channel when offline participation is limited, so governments should further develop online participation opportunities and construct better e-government systems to meet people’s needs in extraordinary situations such as pandemic control.

Finally, the composition of participation behaviors should be more important than the overall participation levels, and local governments should stimulate citizens’ coproduction behavior, one type of participation behavior, in response to future crises. Existing crisis management research has primarily assessed governments’ crisis response behaviors and their effects from a top-down perspective (Cheng et al., 2020; Christensen and Lægreid, 2020), but they neglect citizens’ bottom-up reactions to different government crisis interventions. Though some studies have highlighted the critical role of citizens in crisis governance, they mainly emphasize their compliance or noncompliance behaviors as policy followers, such as adhering to social distance policies and wearing face masks (Bargain and Aminjonov, 2020; Betsch et al., 2020). However, our findings inspire that citizens can play more active roles in crisis governance by providing suggestions or engaging in coproduction behaviors in the future.

Future directions

We offer the following four potential directions for future research. First, due to data availability and wide coverage of the platform, we used LLMB data to quantify the impacts of NPIs on citizen’s online participation. Though the LLMB is one of the most important platforms, there are other online platforms for government-citizen interaction, such as Weibo, WeChat, local government websites, and 12345 hotlines. Future research could expand data sources and use alternative data to enrich the measurement of citizen’s online participation. Second, online participation differs between people with different characteristics (Vicente and Novo, 2014). Barriers to information, internet accessibility issues, and different political interests mean that disadvantaged groups such as the elderly are at risk of being overlooked in our analysis. Hence, individual-level data could be added to clarify the distribution of policy benefits across populations with different demographic characteristics. Third, our results showed that NPIs changed people’s online participation behavior, but it is difficult to determine whether this change will be sustained or was only temporary. If the latter is the case, network engagement could return to its original level once all interventions have been removed. However, China has continued to implement interventions over the past three years, making it difficult to obtain a “clean” set of data to examine. Depending on government actions and the trajectory of the pandemic, such data could become available later, and future research could then examine this question. Finally, it focused on the effects of counter-COVID-19 interventions on online participation levels. Future research could delve into the nature (for instance, content expressions and affective tendencies) of that participation.

Data availability

NPIs data were collected from the websites of provincial/city health commissions and city governments through authors’ manual coding, which was available in the supplementary information file. The authors also wrote a Python crawler program to crawl online participation data and local COVID-19 severity data from relevant authorities, including the Local Leadership Message Board (https://liuyan.people.com.cn/index) and Sina Real-time COVID-19 Pandemic Data Platform (https://news.sina.cn/zt_d/yiqing0121).

References

Anderson SC, Edwards AM, Yerlanov M et al. (2020) Quantifying the impact of COVID-19 control measures using a Bayesian model of physical distancing. PLoS Comput Biol 16:e1008274. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1008274

Bambra C, Riordan R, Ford J et al. (2020) The COVID-19 pandemic and health inequalities. J Epidemiol Commun Health 74(11):964–968. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2020-214401

Bargain O, Aminjonov U (2020) Trust and compliance to public health policies in times of COVID-19. J Public Econ 192:104316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104316

Bell D, Nicoll A, Fukuda K et al. (2006) Nonpharmaceutical interventions for pandemic influenza, national and community measures. Emerg Infect Dis 12(1):88–94

Betsch C, Korn L, Sprengholz P et al. (2020) Social and behavioral consequences of mask policies during the COVID-19 pandemic. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117(36):21851–21853. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2011674117

Blackwell M, Glynn AN (2018) How to make causal inferences with time-series cross-sectional data under selection on observables. Am Political Sci Rev 112(4):1067–1082. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055418000357

Block P, Hoffman M, Raabe IJ et al. (2020) Social network-based distancing strategies to flatten the COVID-19 curve in a post-lockdown world. Nat Hum Behav 4(6):588–596. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-0898-6

Bonaccorsi G, Pierri F, Cinelli M et al. (2020) Economic and social consequences of human mobility restrictions under COVID-19. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117(27):15530–15535. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2007658117

Bonsón E, Royo S, Ratkai M (2015) Citizens’ engagement on local governments’ Facebook sites. An empirical analysis: the impact of different media and content types in Western Europe. Gov Inf Q 32(1):52–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2014.11.001

Braga F, Scarpa GM, Brando VE et al. (2020) COVID-19 lockdown measures reveal human impact on water transparency in the Venice Lagoon. Sci Total Environ 736:139612. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139612

Brudney JL, England RE (1983) Toward a definition of the coproduction concept. Public Adm Rev 43:59–65

Bruelhart M, Klotzbuecher V, Lalive R et al. (2021) Mental health concerns during the COVID-19 pandemic as revealed by helpline calls. Nature 600(7887):121–126. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-04099-6

Cao S, Gan Y, Wang C et al. (2020) Post-lockdown SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid screening in nearly ten million residents of Wuhan, China. Nat Commun 11(1):5917. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-19802-w

Cauchemez S, Valleron AJ, Boëlle PY et al. (2008) Estimating the impact of school closure on influenza transmission from Sentinel data. Nature 452(7188):750–754. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature06732

Cellini N, Canale N, Mioni G et al. (2020) Changes in sleep pattern, sense of time and digital media use during COVID-19 lockdown in Italy. J Sleep Res 29(4):e13074. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsr.13074

Chen S, Yang J, Yang W et al. (2020) COVID-19 control in China during mass population movements at New Year. Lancet 395(10226):764–766. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30421-9

Cheng YD, Yu J, Shen Y et al. (2020) Coproducing responses to COVID-19 with community-based organizations: Lessons from Zhejiang Province, China. Public Adm Rev 80(5):866–873. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13244

Chinazzi M, Davis JT, Ajelli M et al. (2020) The effect of travel restrictions on the spread of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak. Science 368(6489):395–400. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aba9757

Christensen T, Lægreid P (2020) Balancing governance capacity and legitimacy: how the Norwegian government handled the COVID-19 crisis as a high performer. Public Adm Rev 80(5):774–779. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13241

Di Renzo L, Gualtieri P, Pivari F et al. (2020) Eating habits and lifestyle changes during COVID-19 lockdown: an Italian survey. J Transl Med 18(1):229. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-020-02399-5

Galasso V, Pons V, Profeta P et al. (2020) Gender differences in COVID-19 attitudes and behavior: panel evidence from eight countries. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117(44):27285–27291. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2012520117

Gibson R, Cantijoch M (2013) Conceptualizing and measuring participation in the age of the internet: is online political engagement really different to offline? J Polit 75(3):701–716. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381613000431

Gil de Zúñiga H, Garcia-Perdomo V, McGregor SC (2015) What is second screening? Exploring motivations of second screen use and its effect on online political participation. J Commun 65(5):793–815. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12174

Gligoric K, Chiolero A, Kiciman E et al. (2022) Population-scale dietary interests during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nat Commun 13(1):1073. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-28498-z

Goudeau S, Sanrey C, Stanczak A et al. (2021) Why lockdown and distance learning during the COVID-19 pandemic are likely to increase the social class achievement gap. Nat Hum Behav 5(10):1273–1281. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01212-7

Gozzi N, Tizzoni M, Chinazzi M et al. (2021) Estimating the effect of social inequalities on the mitigation of COVID-19 across communities in Santiago de Chile. Nat Commun 12(1):2429. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-22601-6

Guan D, Wang D, Hallegatte S et al. (2020) Global supply-chain effects of COVID-19 control measures. Nat Hum Behav 4(6):577–587. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-0896-8

He G, Pan Y, Tanaka T (2020) The short-term impacts of COVID-19 lockdown on urban air pollution in China. Nat Sustain 3(12):1005–1011. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-020-0581-y

Hargittai E, Shaw A (2013) Digitally savvy citizenship: the role of internet skills and engagement in young adults’ political participation around the 2008 presidential election. J Broadcast Electron 57(2):115–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2013.787079

Hatchett RJ, Mecher CE, Lipsitch M (2007) Public health interventions and epidemic intensity during the 1918 influenza pandemic. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104(18):7582–7587. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0610941104

Haug N, Geyrhofer L, Londei A et al. (2020) Ranking the effectiveness of worldwide COVID-19 government interventions. Nat Hum Behav 4(12):1303–1312. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-01009-0

Hunter RF, Garcia L, de Sa TH et al. (2021) Effect of COVID-19 response policies on walking behavior in US cities. Nat Commun 12(1):3652. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-23937-9

Imai K, Kim IS (2019) When should we use unit fixed effects regression models for causal inference with longitudinal data? Am J Polit Sci 63(2):467–490. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12417

Jacobson LS, LaLonde RJ (1993) Earnings losses of displaced workers. Am Econ Rev 83(4):685–709

Krueger BS (2006) A comparison of conventional and internet political mobilization. Am Polit Res 34(6):759–776. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532673X06290911

Kucharski AJ, Russell TW, Diamond C et al. (2020) Early dynamics of transmission and control of COVID-19: a mathematical modelling study. Lancet Infect Dis 20(5):553–558. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30144-4

La Ferrara E, Chong A, Duryea S (2012) Soap operas and fertility: evidence from Brazil. Am Econ J-Appl Econ 4(4):1–31. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.4.4.1

Lee J, Kim S (2018) Citizens’ e-participation on agenda setting in local governance: do individual social capital and e-participation management matter? Public Manag Rev 20(6):873–895. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2017.1340507

Le T, Wang Y, Liu L et al. (2020) Unexpected air pollution with marked emission reductions during the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Science 369(6504):702–706. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abb7431

Lecocq T, Hicks SP, Van Noten K et al. (2020) Global quieting of high-frequency seismic noise due to COVID-19 pandemic lockdown measures. Science 369(6509):1338–1343. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abd2438

Liu L, Wang Y, Xu Y (2020) A practical guide to counterfactual estimators for causal inference with time-series cross-sectional data. Am J Polit Sci 68(1):160–176. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3555463

Lin Y, Qin Y, Wu J et al. (2021) Impact of high-speed rail on road traffic and greenhouse gas emissions. Nat Clim Chang 11(11):952–957. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-021-01190-8

Liu Z, Ciais P, Deng Z et al. (2020) Near-real-time monitoring of global CO2 emissions reveals the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. Nat Commun 11(1):5172. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-18922-7

March D, Metcalfe K, Tintore J et al. (2021) Tracking the global reduction of marine traffic during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nat Commun 12(1):2415. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-22423-6

Marien S, Hooghe M, Quintelier E (2010) Inequalities in non-institutionalised forms of political participation: a multi-level analysis of 25 countries. Polit Stud-Lond 58(1):187–213. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2009.00801.x

Markel H, Lipman HB, Navarro JA et al. (2007) Nonpharmaceutical interventions implemented by US cities during the 1918-1919 influenza pandemic. J Am Med Assoc 298(6):644–654. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.298.6.644

Manica M, Guzzetta G, Riccardo F et al. (2021) Impact of tiered restrictions on human activities and the epidemiology of the second wave of COVID-19 in Italy. Nat Commun 12(1):4570. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-24832-z

Medaglia R (2012) Eparticipation research: Moving characterization forward (2006–2011). Gov Inf Q 29(3):346–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2012.02.010

Nam T (2012) Dual effects of the internet on political activism: Reinforcing and mobilizing. 29(1):S90–S97 Gov Inform Q 29(1):S90–S97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2011.08.010

Oser J, Hooghe M, Marien S (2013) Is online participation distinct from offline participation? A latent class analysis of participation types and their stratification. Polit Res Q 66(1):91–101. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912912436695

Paik W (2012) Economic development and mass political participation in contemporary China: determinants of provincial petition (Xinfang) activism 1994–2002. Int Polit Sci Rev 33(1):99–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512111409528

Pierce M, Hope H, Ford T et al. (2020) Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal probability sample survey of the UK population. Lancet Psychiatry 7(10):883–892. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30308-4

Rodríguez-Estrada A, Muñiz C, Echeverría M (2020) Relationship between online and offline political participation in sub-national campaigns. Cuad Info-Santiago 46:1–23. https://doi.org/10.7764/cdi.46.1712

Rossi R, Socci V, Talevi D et al. (2020) COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown measures impact on mental health among the general population in Italy. Front Psychiatry 11:790. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00790

Ru H, Zou K (2022) How do individual politicians affect privatization? Evidence from China. Rev Financ 26(3):637–672. https://doi.org/10.1093/rof/rfab030

Ruess C, Hoffmann CP, Boulianne S et al. (2021) Online political participation: the evolution of a concept. Inf Commun Soc 26(8):1495–1512. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2021.2013919

Sæbø Ø, Rose J, Skiftenes Flak L (2008) The shape of eParticipation: characterizing an emerging research area. Gov Inf Q 25(3):400–428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2007.04.007

Schlosser F, Maier BF, Jack O et al. (2020) COVID-19 lockdown induces disease-mitigating structural changes in mobility networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117(52):32883–32890. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2012326117

Shah DV, Cho J, Eveland WP et al. (2005) Information and expression in a digital age: modeling internet effects on civic participation. Commun Res 32(5):531–565. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650205279209

Song H, Sun Y, Chen D (2019) Assessment for the effect of government air pollution control policy: empirical evidence from low-carbon city construction in China. J Manag World 35(06):95-108+195. https://doi.org/10.19744/j.cnki.11-1235/f.2019.0082. (in Chinese)

Soucy JPR, Sturrock SL, Berry I et al. (2024) Public transit mobility as a leading indicator of COVID-19 transmission in 40 cities during the first wave of the pandemic. PeerJ 12:e17455. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.17455

Su Z, Meng T (2016) Selective responsiveness: online public demands and government responsiveness in authoritarian China. Soc Sci Res 59:52–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2016.04.017

Sun L, Abraham S (2021) Estimating dynamic treatment effects in event studies with heterogeneous treatment effects. J Econ 225(2):175–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2020.09.006

Teng Y, Guo C (2022) What determines the level of responsiveness of local governments? – Based on fuzzy sets qualitative comparative analysis. J Xi'an Jiao Tong Univ (Soc Sci) 42(06):150–159. https://doi.org/10.15896/j.xjtuskxb.202206016. (in Chinese)

Theocharis Y, de Moor J, van Deth JW (2021) Digitally networked participation and lifestyle politics as new modes of political participation. Policy Internet 13(1):30–53. https://doi.org/10.1002/poi3.231

Thomson DJM, Barclay DR (2020) Real-time observations of the impact of COVID-19 on underwater noise. J Acoust Soc Am 147(5):3390–3396. https://doi.org/10.1121/10.0001271

Valenzuela S, Kim Y, Gil de Zuniga H (2012) Social networks that matter: exploring the role of political discussion for online political participation. Int J Public Opin Res 24(2):163–184. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/edr037

Vicente MR, Novo A (2014) An empirical analysis of e-participation. The role of social networks and e-government over citizens’ online engagement. Gov Inf Q 31(3):379–387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2013.12.006

Vissers S, Stolle D (2014) The Internet and new modes of political participation: online versus offline participation. Inf Commun Soc 17(8):937–955. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2013.867356

Wang J, Fan Y, Palacios J et al. (2022) Global evidence of expressed sentiment alterations during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nat Hum Behav 6(3):349–358. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-022-01312-y

Wang X, Liu Z, Ma L (2020) Can the target responsibility system improve government responsiveness?—An analysis based on affordable housing policy. J Public Adm 13(5):2-22+204. (in Chinese)

Wells CR, Sah P, Moghadas SM et al. (2020) Impact of international travel and border control measures on the global spread of the novel 2019 coronavirus outbreak. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117(13):7504–7509. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2002616117

Zhang P (2019) Do energy intensity targets matter for wind energy development? Identifying their heterogeneous effects in Chinese provinces with different wind resources. Renew Energy 139:968–975. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2019.03.007

Zhang P, Zhou DP, Guo JH (2023) Policy complementary or policy crowding-out? Effects of cross-instrumental policy mix on green innovation in China. Technol Forecast Soc 192:122530. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2023.122530

Zhang SX, Wang Y, Rauch A et al. (2020) Unprecedented disruption of lives and work: Health, distress and life satisfaction of working adults in China one month into the COVID-19 outbreak. Psychiatry Res 288:112958. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112958

Zhang X, Lin WY (2014) Political participation in an unlikely place: How individuals engage in politics through social networking sites in China. Int J Commun-US 8:21–42

Zhang ZY, Zhang P (2023) The long-term impact of natural disasters on human capital: evidence from the 1975 Zhumadian flood. Int J Disaster Risk Re 91:103671. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2023.103671

Zheng S, Lan Y, Li F (2021) The interactive logic of online public opinion and government response—based on the data analysis of the “Leadership Message Board” during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Public Manag 18(3):24-37+169. https://doi.org/10.16149/j.cnki.23-1523.20210311.002. (in Chinese)

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Shanghai Education Development Foundation and Shanghai Municipal Education Commission under Grant [number 19CG13].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Pan Zhang: Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, visualization, writing—original draft preparation, writing—reviewing and editing, supervision; Zhouling Bai: Data curation, formal analysis, visualization, software, writing—original draft preparation, writing—reviewing and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, P., Bai, Z. Leaving messages as coproduction: impact of government COVID-19 non-pharmaceutical interventions on citizens’ online participation in China. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 875 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03376-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03376-9