Abstract

Digital equity is imperative for realizing the Sustainable Development Goals, particularly SDG9 and SDG10. Recent empirical studies indicate that Design for Digital Equity (DDE) is an effective strategy for achieving digital equity. However, before this review, the overall academic landscape of DDE remained obscure, marked by substantial knowledge gaps. This review employs a rigorous bibliometric methodology to analyze 1705 DDE-related publications, aiming to delineate DDE’s research progress and intellectual structure and identify research opportunities. The retrieval strategy was formulated based on the PICo framework, with the process adhering to the PRISMA systematic review framework to ensure transparency and replicability of the research method. CiteSpace was utilized to visually present the analysis results, including co-occurrences of countries, institutions, authors, keywords, emerging trends, clustering, timeline analyses, and dual-map overlays of publications. The results reveal eight significant DDE clusters closely related to user-centered design, assistive technology, digital health, mobile devices, evidence-based practices, and independent living. A comprehensive intellectual structure of DDE was constructed based on the literature and research findings. The current research interest in DDE lies in evidence-based co-design practices, design issues in digital mental health, acceptance and humanization of digital technologies, digital design for visually impaired students, and intergenerational relationships. Future research opportunities are identified in DDE’s emotional, cultural, and fashion aspects; acceptance of multimodal, tangible, and natural interaction technologies; needs and preferences of marginalized groups in developing countries and among minority populations; and broader interdisciplinary research. This study unveils the multi-dimensional and inclusive nature of methodological, technological, and user issues in DDE research. These insights offer valuable guidance for policy-making, educational strategies, and the development of inclusive digital technologies, charting a clear direction for future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Digital equity has emerged as a critical factor in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), especially SDG9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure) and SDG10 (Reduced Inequalities) (United Nations, 2021; UNSD 2023), amidst the rapid evolution of digital technologies. In our increasingly digitalized society, these technologies amplify and transform existing social inequalities while offering numerous benefits, leading to more significant disparities in access and utilization (Grybauskas et al., 2022). This situation highlights the critical need for strategies that promote equitable digital participation, ensuring alignment with the overarching objectives of the SDGs. Digital equity, a multi-faceted issue, involves aspects such as the influence of cultural values on digital access (Yuen et al., 2017), the challenges and opportunities of technology in higher education (Willems et al., 2019), and the vital role of government policies in shaping digital divides (King & Gonzales, 2023), and the impact on healthcare access and delivery (Lawson et al., 2023). Equally important are the socioeconomic factors that intersect with digital equity (Singh, 2017) and the pressing need for accessible digital technologies for disabled individuals (Park et al., 2019). These issues are observed globally, necessitating diverse and inclusive strategies.

Design thinking, in addressing issues of social equality and accessibility, plays an essential role in accessibility (Persson et al., 2015; Dragicevic et al., 2023a); in other words, it serves as a crucial strategy for reducing social inequality. Indeed, design strategies focused on social equality, also known as Equity-Centered Design (Oliveri et al., 2020; Bazzano et al., 2023), are diverse, including universal design (Mace (1985)), Barrier-free design (Cooper et al., 1991), inclusive design (John Clarkson, Coleman (2015)), and Design for All (Bendixen & Benktzon, 2015). Stanford d.school has further developed the Equity-Centered Design Framework based on its design thinking model (Stanford d.school, 2016) to foster empathy and self-awareness among designers in promoting equality. Equity-centered approaches are also a hot topic in academia, especially in areas like education (Firestone et al., 2023) and healthcare (Rodriguez et al., 2023). While these design approaches may have distinct features and positions due to their developmental stages, national and cultural contexts, and the issues they address, Equity-Centered Design consistently plays a vital role in achieving the goal of creating accessible environments and products, making them accessible and usable by individuals with various abilities or backgrounds (Persson et al., 2015).

Equity-centered design initially encompassed various non-digital products, but with the rapid advancement of digitalization, it has become increasingly critical to ensure that digital technologies are accessible and equitable for all users. This can be referred to as Design for Digital Equity (DDE). However, the current landscape reveals a significant gap in comprehensive research focused on Design for Digital Equity (DDE). This gap highlights the need for more focused research and development in this area, where bibliometrics can play a significant role. Through systematic reviews and visualizations, bibliometric analysis can provide insights into this field’s intellectual structure, informing and guiding future research directions in digital equity and design.

Bibliometrics, a term first coined by Pritchard in 1969 (Broadus, 1987), has evolved into an indispensable quantitative tool for analyzing scholarly publications across many research fields. This method, rooted in the statistical analysis of written communication, has significantly enhanced our understanding of academic trends and patterns. Its application spans environmental studies (Wang et al., 2021), economics (Qin et al., 2021), big data (Ahmad et al., 2020), energy (Xiao et al., 2021), medical research (Ismail & Saqr, 2022) and technology acceptance (Wang et al., 2022). By distilling complex publication data into comprehensible trends and patterns, bibliometrics has become a key instrument in shaping our understanding of the academic landscape and guiding future research directions.

In bibliometrics, commonly used tools such as CiteSpace (Chen, 2006), VOSviewer (Van Eck, Waltman (2010)), and HistCite (Garfield, 2009) are integral for advancing co-citation analysis and data visualization. Among these, CiteSpace, developed by Professor Chen (Chen, 2006), is a Java-based tool pivotal in advancing co-citation analysis for data visualization and analysis. Renowned for its integration of burst detection, betweenness centrality, and heterogeneous network analysis, it is essential in identifying research frontiers and tracking trends across various domains. Chen demonstrates the versatility of CiteSpace in various fields, ranging from regenerative medicine to scientific literature, showcasing its proficiency in extracting complex insights from data sets (Chen, 2006). Its structured methodology, encompassing time slicing, thresholding, and more, facilitates comprehensive analysis of co-citations and keywords. This enhances not only the analytical capabilities of CiteSpace but also helps researchers comprehend trends within specific domains. (Chen et al. 2012; Ping et al. 2017). Therefore, CiteSpace is a precious tool in academic research, particularly for disciplines that require in-depth analysis of evolving trends and patterns.

After acknowledging the significance of DDE in the rapidly evolving digital environment, it becomes imperative to explore the academic contours of this field to bridge knowledge gaps, a critical prerequisite for addressing social inequalities within digital technology development. We aim to scrutinize DDE’s research progress and intellectual structure, analyzing a broad spectrum of literature with the aid of bibliometric and CiteSpace methodologies. Accordingly, four research questions (RQs) have been identified to guide this investigation. The detailed research questions are as follows:

RQ1: What are the trends in publications in the DDE field from 1995 to 2023?

RQ2: Who are the main contributors, and what are the collaboration patterns in DDE research?

RQ3: What are the current research hotspots in DDE?

RQ4: What is the intellectual structure and future trajectory of DDE?

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: The Methods section explains our bibliometric approach and data collection for DDE research. The Results section details our findings on publication trends and collaborative networks, addressing RQ1 and RQ2. The Discussion section delves into RQ3 and RQ4, exploring research hotspots and the intellectual structure of DDE. The Conclusion section summarizes our study’s key insights.

Methods

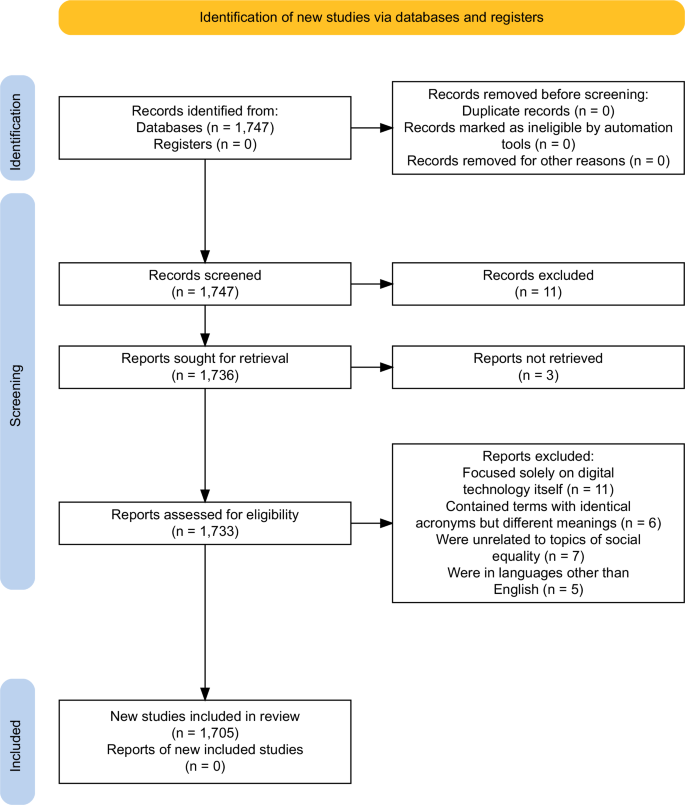

In this article, the systematic review of DDE follows the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines (PRISMA 2023), which are evidence-based reporting guidelines for systematic review reports (Moher et al., 2010). PRISMA was developed to enhance the quality of systematic reviews and enhance the clarity and transparency of research findings (Liberati et al., 2009). To achieve this goal, the research workflow in this study incorporates an online tool based on the R package from PRISMA 2020. This tool enables researchers to rapidly generate flowcharts that adhere to the latest updates in the PRISMA statement, ensuring transparency and reproducibility in the research process. This workflow comprises three major stages: Identification, Screening, and Inclusion, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

Additionally, to obtain high-quality data sources, the Web of Science (referred to as WOS), provided by Clarivate Analytics, was chosen. WOS is typically considered the optimal data source for bibliometric research (van Leeuwen, 2006). The WOS Core Collection comprises over 21,000 peer-reviewed publications spanning 254 subject categories and 1.9 billion cited references, with the earliest records traceable back to 1900 (Clarivate, 2023). To thoroughly explore the research on DDE, this review utilized all databases within the WOS Core Collection as the source for data retrieval.

Search strategy

Developing a rational and effective search strategy is crucial for systematic reviews (Cooper et al., 2018), typically necessitating a structured framework to guide the process (Sayers, 2008). This approach ensures comprehensive and relevant literature coverage. To comprehensively and accurately assess the current state and development of “Design for Digital Equity,” this paper employs the PICo (participants, phenomena of interest, and context) model as its search strategy, a framework typically used for identifying research questions in systematic reviews (Stern et al., 2014). While the PICo framework is predominantly utilized within clinical settings for systematic reviews, its structured approach to formulating research questions and search strategies is equally applicable across many disciplines beyond the clinical environment. This adaptability makes it a suitable choice for exploring the multi-faceted aspects of digital equity in a non-clinical context (Nishikawa-Pacher, 2022).

This review, structured around the PICo framework, sets three key concepts (search term groups): Participants (P): any potential digital users; Phenomena of Interest (I): equity-centered design; Context (Co): digital equity. To explore the development and trends of DDE comprehensively, various forms of search terms are included in each PICo element. The determination of search terms is a two-stage process. In the first stage, core terms of critical concepts like equity-centered design, digital equity, and Design for Digital Equity, along with their synonyms, different spellings, and acronyms, are included in the list of candidate search terms. Wildcards (*) are used to expand the search range to ensure the inclusion of all variants and derivatives of critical terms, thus enhancing the thoroughness and depth of the search. However, studies have indicated the challenge of identifying semantically unrelated terms relevant to the research (Chen, 2018). To address this issue, the second phase of developing the search strategy involves reading domain-specific literature reviews using these core terms. This literature-based discovery (LBD) approach can identify hidden, previously unknown relationships, finding significant connections between different kinds of literature (Kastrin & Hristovski, 2021). The candidate word list is then reviewed, refined, or expanded by domain experts. Finally, a search string (Table 1) is constructed with all search terms under each search term group linked by the Boolean OR (this term or that term), and the Boolean links each group AND (this group of terms and that group of terms).

Inclusion criteria

Following the PRISMA process (Fig. 1), literature in the identification phase was filtered using automated tools based on publication data attributes such as titles, subjects, and full texts or specific criteria like publication names, publication time ranges, and types of publication sources. Given the necessity for a systematic and extensive exploration of DDE research, this review employed an advanced search using “ALL” instead of “topic” or “Title” in the search string to ensure a broader inclusion of results. No limitations were set on other attributes of the literature. The literature search was conducted on December 5, 2023, resulting in 1747 publications exported in Excel for further screening.

During the literature screening phase, the authors reviewed titles and abstracts, excluding 11 publications unrelated to DDE research. Three papers were inaccessible in the full-text acquisition phase. The remaining 1729 publications were then subjected to full-text review based on the following inclusion and exclusion criteria. Eventually, 1705 papers meeting the criteria were imported into CiteSpace for analysis.

Papers were included in this review if they met the following criteria:

-

They encompassed all three elements of PICo: stakeholders or target users of DDE, design relevance, and digitalization aspects.

-

They had transparent research methodologies, whether empirical or review studies employing qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods.

-

They were written in English.

Papers were excluded if they:

-

Focused solely on digital technology, unrelated to design, human, and social factors.

-

Contained terms with identical acronyms but different meanings, e.g., ICT stands for Inflammation of connective tissue in medicine.

-

Were unrelated to topics of social equality.

-

Were in languages other than English.

Data analysis

To comprehensively address Research Question 1: “What are the publication trends in the DDE field from 1995 to 2023?” this study utilized CiteSpace to generate annual trend line graphs for descriptive analysis. This analysis revealed the annual development trends within the DDE research field and identified vital research nodes and significant breakthroughs by analyzing the citation frequency of literature across different years. Utilizing the burst detection feature in CiteSpace, key research papers and themes were further identified, marking periods of significant increases in research activity. For Research Question 2: “Who are the main contributors to DDE research, and what are their collaboration patterns?” nodes for countries, institutions, cited authors, cited publications, and keywords were set up in CiteSpace for network analysis. Our complex network diagrams illustrate the collaboration relationships between different researchers and institutions, where the size of the nodes indicates the number of publications by each entity, and the thickness and color of the lines represent the strength and frequency of collaborations.

Additionally, critical scholars and publications that act as bridges within the DDE research network were identified through centrality analysis. In the keyword analysis, the focus was on co-occurrence, trend development, and clustering. Current research hotspots were revealed using the LSI algorithm in CiteSpace for cluster analysis, demonstrating how these hotspots have evolved over time through timeline techniques. A dual-map overlay analysis was used to reveal citation relationships between different disciplines, showcasing the interdisciplinary nature of DDE research. In the visual displays of CiteSpace, the visual attributes of nodes and links were meticulously designed to express the complex logical relationships within the data intuitively. The size of nodes typically reflects the publication volume or citation frequency of entities such as authors, institutions, countries, or keywords, with larger nodes indicating highly active or influential research focal points. The change in node color often represents the progress of research over time, with gradients from dark to light colors indicating the evolution from historical to current research. Whether solid or dashed, the outline of nodes differentiates mainstream research areas from marginal or emerging fields. The thickness and color of the lines reflect the strength of collaborations or frequency of citations, aiding in the identification of close collaborations or frequent citations. These design elements not only enhance the information hierarchy of the diagrams but also improve the usability and accuracy for users exploring and analyzing the data, effectively supporting researchers in understanding the structure and dynamics of the academic field. The subsequent research results section provides detailed descriptions for each visual element.

Results

The first section of the Results primarily addresses RQ1: “What are the trends in publications in the DDE field from 1995 to 2023?” The subsequent sections collectively address RQ2: “Who are the main contributors, and what are the collaboration patterns in DDE research?”

Analysis of Publication Trends

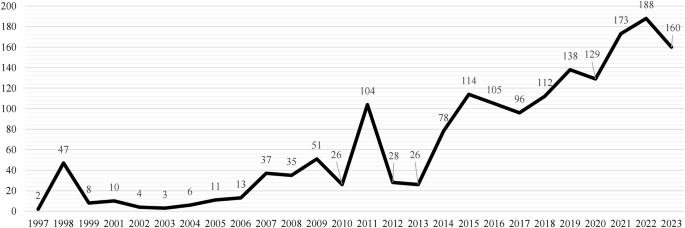

Figure 2, extracted from the WOS citation analysis report, delineates the progression of annual scholarly publications within the Design for Digital Equity field. This trend analysis resonates with de Solla Price’s model of scientific growth (Price 1963), beginning with a slow and steady phase before transitioning into a period of more rapid expansion. Notably, a pronounced spike in publications was observed following 2020, characterized by the global COVID-19 pandemic. This uptick indicates an acute scholarly response to the pandemic, likely propelled by the heightened need for digital equity solutions as the world adapted to unprecedented reliance on digital technologies for communication, work, and education amidst widespread lockdowns and social distancing measures. The graph presents a clear visualization of this scholarly reaction, with the peak in 2021 marking the zenith of research output, followed by a slight retraction, which may suggest a period of consolidation or a pivot towards new research frontiers in the post-pandemic era.

Visual analysis by countries or regions

Table 2 presents an illustrative overview of the diverse global contributions to research on “Design for Digital Equity,” including a breakdown of the number of publications, centrality, and the initial year of engagement for each participating country. The United States stands preeminent with 366 publications, affirming its central role in the domain since the mid-1990s. Despite fewer publications, the United Kingdom boasts the highest centrality, signaling its research as notably influential within the academic network since the late 1990s. Since China entered the DDE research arena in 2011, its publications have had explosive growth, reflecting rapid ascension and integration into the field. Furthermore, the extensive volume of publications from Canada and the notable centrality of Spain underscores their substantial and influential research endeavors. The table also recognizes the contributions from countries such as Germany, Italy, and Australia, each infusing unique strengths and perspectives into the evolution of DDE research.

Figure 3, crafted within CiteSpace, delineates the collaborative contours of global research in Design for Digital Equity (DDE). Literature data are input with ‘country’ as the node type and annual segmentation for time slicing, employing the ‘Cosine’ algorithm to gauge the strength of links and the ‘g-index’ (K = 25) for selection criteria. The visualization employs a color gradient to denote the years of publication, with the proximity of nodes and the thickness of the interconnecting links articulating the intensity and frequency of collaborative efforts among nations. For instance, the close-knit ties between the United States, Germany, and France underscore a robust tripartite research collaboration within the DDE domain. The size of the nodes corresponds directly to the proportion of DDE publications contributed by each country. Larger nodes, such as those representing the USA and Germany, suggest more publications, indicating significant research activity and influence within the field. Purple nodes, such as those representing England and Canada, signal a strong centrality within the network, suggesting these countries contribute significantly and play a pivotal role in disseminating research findings throughout the network. The intertwining links of varying thickness reveal the nuanced interplay of collaboration: dense webs around European countries, for instance, underscore a rich tradition of continental cooperation, while transatlantic links point to ongoing exchanges between North American and European researchers. Moreover, the appearance of vibrant links extending toward Asian countries such as China and South Korea reflects the expanding scope of DDE research to encompass a truly global perspective, integrating diverse methodologies and insights as the research community tackles the universal challenges of digital equity.

Visual analysis by institutions

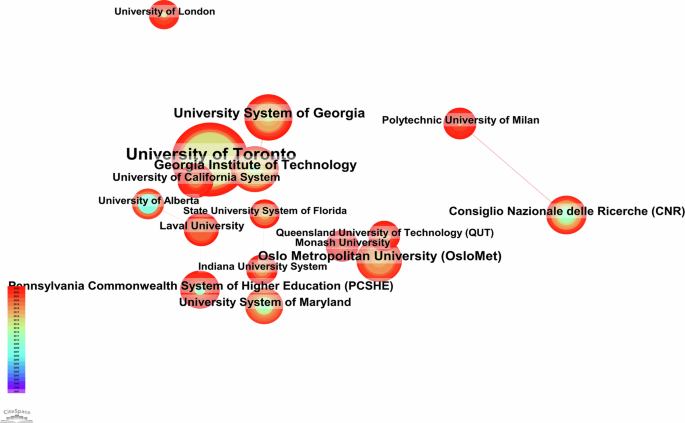

Table 3 presents a quantified synopsis of institutional research productivity and centrality within the Design for Digital Equity field. The University of Toronto emerges as the most prolific contributor, with 64 publications and a centrality score of 0.06, indicating a significant impact on the field since 2008. The University System of Georgia and the Georgia Institute of Technology, each with 27 and 25 publications, respectively, registering a centrality of 0.01 since 2006, denoting their sustained scholarly activity over time. The Oslo Metropolitan University, with 23 publications and a centrality of 0.02 since 2016, and the Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche, with 17 publications since 2009, highlight the diverse international engagement in DDE research. The table also notes the early contributions of the Pennsylvania Commonwealth System of Higher Education, with 17 publications since 2004, although its centrality remains at 0.01. Institutions such as Laval University, Monash University, and the Polytechnic University of Milan show emergent centrality in the field, with recent increases in scholarly output, as indicated by their respective publication counts of 13, 12, and 12 since 2019, 2020, and 2018. This data evidences a dynamic and growing research domain characterized by historical depth and contemporary expansion.

Figure 4 displays a network map highlighting the collaborative landscape among institutions in the field of DDE. The University of Toronto commands a central node with a substantial size, indicating its leading volume of research output. The University of Alberta and CNR exhibit nodes colored to represent earlier works in the field, establishing their roles as foundational contributors. Inter-institutional links, albeit pleasing, are observable, suggesting research collaborations. Nodes such as the University of London and the Polytechnic University of Milan, while smaller, are nonetheless integral, denoting their active engagement in DDE research. The color coding of nodes corresponds to publication years, with warmer colors indicating more recent research, providing a temporal dimension to the map. This network visualization is an empirical tool to assess the scope and scale of institutional contributions and collaborations in DDE research.

Analysis by publications

Table 4 delineates the pivotal academic publications contributing to the field, as evidenced by citation count, centrality, and publication year, offering a longitudinal perspective of influence and relevance. ‘Lecture Notes in Computer Science’ leads the discourse with 354 citations and the highest centrality of 0.10 since 2004, indicating its foundational and central role over nearly two decades. This is followed by the ‘Journal of Medical Internet Research,’ with 216 citations since 2013 and centrality of 0.05, evidencing a robust impact in a shorter timeframe. The relationship between citation count and centrality reveals a pattern of influential cores within the field. Publications with higher citation counts generally exhibit greater centrality, suggesting that they are reference points within the academic network and instrumental in shaping the digital equity narrative. The thematic diversity of the publications—from technology-focused to health-oriented publications like ‘Computers in Human Behavior’ and ‘Disability and Rehabilitation’—reflects the interdisciplinary nature of research in digital equity, encompassing a range of issues from technological access to health disparities. ‘CoDesign,’ despite its lower position with 101 citations since 2016 and centrality of 0.01, represents the burgeoning interest in participatory design practices within the field. Its presence underscores the evolving recognition of collaborative design processes as essential to achieving digital equity, particularly in the later years where user-centered design principles are increasingly deemed critical for inclusivity in digital environments.

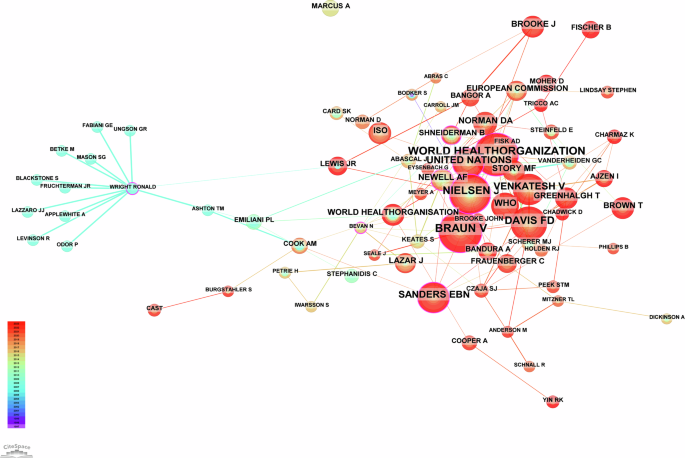

Visual analysis by authors

Table 5 enumerates the most influential authors in the domain of DDE research, ranked by citation count and centrality within the academic network from the year of their first cited work. The table is led by Braun V., with a citation count of 103 and a centrality of 0.13 since 2015, indicating a strong influence in the recent scholarly conversation on DDE. Close behind, the World Health Organization (WHO), with 97 citations and a centrality of 0.10 since 2012, and Nielsen J., with an impressive centrality of 0.32 and 89 citations since 1999, denote long-standing and significant contributions to the field. The high centrality scores, remarkably Nielsen’s, suggest these authors’ works are central nodes in the network of citations, acting as crucial reference points for subsequent research. Further down the list, authors such as Davis F.D. and Venkatesh V. are notable for their scholarly impact, with citation counts of 74 and 59, respectively, and corresponding centrality measures that reflect their substantial roles in shaping DDE discourse. The table also recognizes the contributions of authoritative entities like the United Nations and the World Health Organization, reflecting digital equity research’s global and policy-oriented dimensions. The presence of ISO in the table, with a citation count of 25 since 2015, underscores the importance of standardization in the digital equity landscape. The diversity in authors and entities—from individual researchers to global organizations—highlights the multi-faceted nature of research in DDE, encompassing technical, social, and policy-related studies.

Figure 5 illustrates the collaborative network between cited authors in the DDE study. The left side of the network map is characterized by authors with cooler-colored nodes, indicating earlier contributions to digital equity research. Among these, Wright Ronald stands out with a significantly large node and a purple outline, highlighting his seminal role and the exceptional citation burst in his work. Cool colors suggest these authors laid the groundwork for subsequent research, with their foundational ideas and theories continuing to be pivotal in the field. Transitioning across the network to the right, a gradual shift to warmer node colors is observed, representing more recent contributions to the field. Here, the nodes increase in size, notably for authors such as Braun V. and the WHO, indicating a high volume of publications and a more contemporary impact on the field. The links between these recent large nodes and the earlier contributors, such as Wright Ronald, illustrate a scholarly lineage and intellectual progression within the research community. The authors with purple outlines on the right side of the map indicate recent citation bursts, signifying that their work has quickly become influential in the academic discourse of digital equity research. These bursts are likely a response to the evolution of digital technologies and the emerging challenges of equality within the digital space.

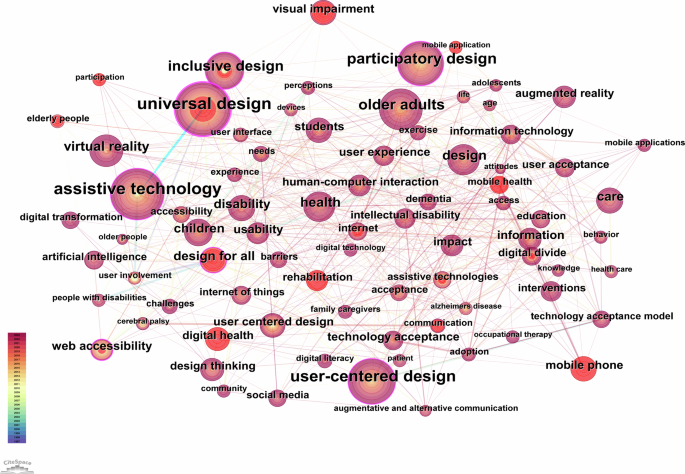

Visual analysis by keywords

The concurrent keywords reflect the research hotspots in the field of DDE. Table 6 presents the top 30 keywords with the highest frequency and centrality, while Fig. 6 shows the co-occurrence network of these keywords. Within the purview of Fig. 6, the visualization elucidates the developmental trajectory of pivotal terms in the digital equity research domain. The nodes corresponding to ‘universal design,’ ‘assistive technology,’ and ‘user-centered design’ are characterized by lighter centers within their larger structures, signifying an established presence and a maturation over time within scholarly research. The robust, blue-hued link connecting ‘universal design’ and ‘assistive technology’ underscores these foundational concepts’ strong and historical interrelation. The nodes encircled by purple outlines, such as ‘universal design,’ ‘inclusive design,’ and ‘participatory design,’ denote a high degree of centrality. This indicates their role as critical junctions within the research network, reflecting a widespread citation across diverse studies and underscoring their integral position within the thematic constellation of the field. Of particular note are the nodes with red cores, such as ‘design for all,’ ‘digital health,’ ‘visual impairment,’ ‘mobile phone,’ and ‘digital divide.’ These nodes signal emergent focal points of research, indicating recent academic interest and citation frequency surges. Such bursts are emblematic of the field’s dynamic nature, pointing to evolving hotspots of scholarly investigation. For instance, the red core of ‘digital health’ suggests an intensifying dialogue around integrating digital technology in health-related contexts, a pertinent issue in modern discourse.

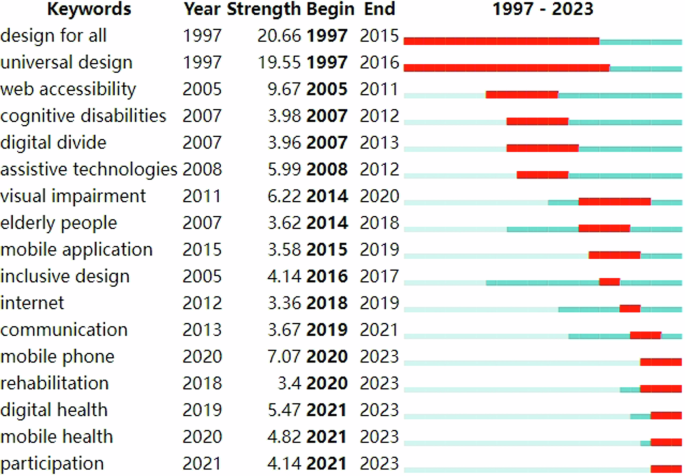

Building upon the highlighted red-core nodes denoting keyword bursts in Figs. 6, 7, “Top 17 Keywords with the Strongest Citation Bursts in DDE,” offers a quantified analysis of such emergent trends. This figure tabulates the keywords that have experienced the most significant surges in academic citations within the field of DDE from 1997 to 2023. Keywords such as ‘design for all’ and ‘universal design’ anchor the list, showcasing their foundational bursts starting from 1997, with ‘design for all’ maintaining a high citation strength of 20.66 until 2015 and ‘universal design’ demonstrating enduring relevance through 2016. This signifies the long-standing and evolving discourse surrounding these concepts. In contrast, terms like ‘mobile phone,’ ‘digital health,’ and ‘participation’ represent the newest fronts in DDE research, with citation bursts emerging as late as 2020 and 2021, reflecting the rapid ascent of these topics in the recent scholarly landscape. The strength of these bursts, particularly the 7.07 for ‘mobile phone,’ suggests a burgeoning field of study responsive to technological advancements and societal shifts. The bar graph component of the figure visually represents the duration of each burst, with red bars marking the start and end years. The length and position of these bars corroborate the temporal analysis, mapping the lifecycle of each keyword’s impact.

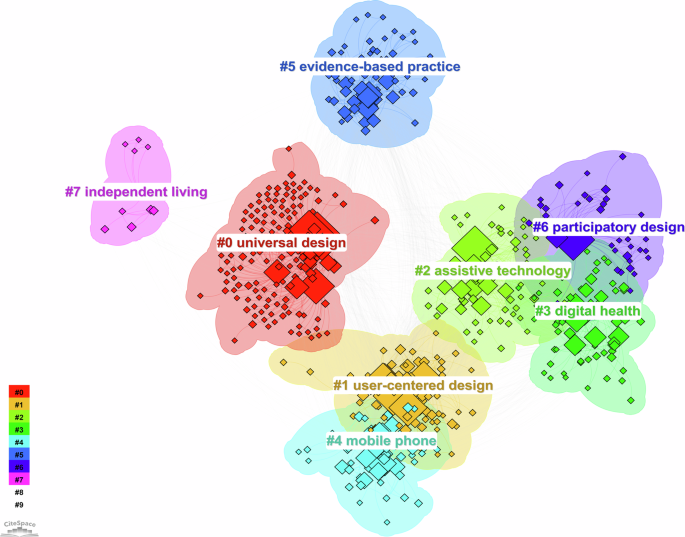

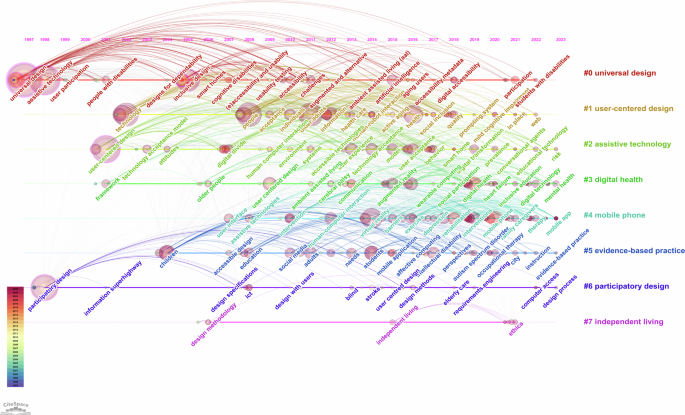

The authors have conducted a keyword clustering analysis on the data presented in Fig. 6, aiming to discern the interrelationships between keywords and delineate structured knowledge domains within the field of DDE. Utilizing the Latent Semantic Indexing (LSI) algorithm to derive the labeling of clusters, they have effectively crystallized seven distinct clusters in DDE research, as depicted in Fig. 8. The cluster represented in red, labeled ‘#0 universal design,’ signifies a group of closely related concepts that have been pivotal in discussions on making design accessible to all users. This cluster’s central placement within the figure suggests its foundational role in DDE. Adjacent to this, in a lighter shade of orange, is the ‘#1 user-centered design’ cluster, indicating a slightly different but related set of terms emphasizing the importance of designing with the end-user’s needs and experiences in mind. The ‘#2 assistive technology’ cluster, shown in yellow, groups terms around technologies designed to aid individuals with disabilities, signifying its specialized yet crucial role in promoting digital equity. Notably, the #3 digital health cluster in green and the #4 mobile phone cluster in turquoise highlight the intersection of digital technology with health and mobile communication, illustrating the field’s expansion into these dynamic research areas. The ‘#6 participatory design’ cluster in purple and ‘#7 independent living’ cluster in pink emphasize collaboration in design processes and the empowerment of individuals to live independently, respectively.

In addition, the timeline function in CiteSpace was used to present the seven clusters in Fig. 8 and the core keywords they contain (the threshold for Label was set to 6) annually, as shown in Fig. 9. The timeline graph delves deeper into the clusters’ developmental stages and interconnections of keywords. In the #0 universal design cluster, the term ‘universal design’ dates back to 1997, alongside ‘assistive technology,’ ‘user participation,’ and ‘PWDs,’ which together marked the inception phase of DDE research within the universal design cluster, where the focus was on creating accessible environments and products for the broadest possible audience. With the advancement of digital technologies, terms like ‘artificial intelligence’ in 2015, ‘digital accessibility’ in 2018, and the more recent ‘students with disabilities’ have emerged as new topics within this cluster. Along with #0 universal design, the #6 participatory design cluster has a similarly lengthy history, with terms like ‘computer access’ and ‘design process’ highlighting the significance of digital design within this cluster. Moreover, within this timeline network, many terms are attributed to specific populations, such as ‘PWDs,’ ‘children,’ ‘aging users,’ ‘adults,’ ‘students,’ ‘blind people,’ ‘stroke patients,’ ‘family caregivers,’ ‘persons with mild cognitive impairments,’ ‘active aging,’ and ‘students with disabilities,’ revealing the user groups that DDE research needs to pay special attention to, mainly the recent focus on ‘mild cognitive impairments’ and ‘students with disabilities,’ which reflect emerging issues. Then, the particularly dense links in the graph hint at the correlations between keywords; for instance, ‘children’ and ‘affective computing’ within the #6 participatory design cluster are strongly related, and the latest terms ‘education’ and ‘autism spectrum disorder occupational therapy’ are strongly related, revealing specific issues within the important topic of education in DDE research. Other nodes with dense links include ‘digital divide,’ ‘user acceptance,’ ‘social participation,’ ‘interventions,’ ‘social inclusion,’ and ‘design for independence,’ reflecting the issues that have received scholarly attention in social sciences. Finally, on the digital technology front, ‘smart home’ emerged in 2006, followed by the terms ‘digital divide’ and ‘user interface’ in the same year. The emergence of ‘VR’ in 2014, ‘AR’ in 2016, and ‘wearable computing’ in 2017 also explain the digital technology focal points worth attention in DDE research.

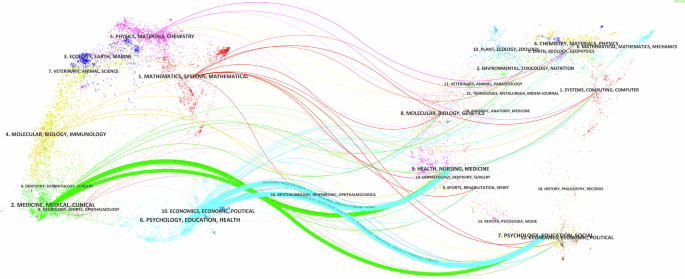

Dual-map overlays analysis of publications clusters

The double map overlay functionality of CiteSpace has been utilized to present a panoramic visualization of the knowledge base in DDE research (Fig. 10). This technique maps the citation dynamics between clusters of cited and cited publications, revealing the field’s interdisciplinary nature and scholarly communication. The left side of the figure depicts clusters of citing publications, showcasing newer disciplinary domains within DDE research. In contrast, the right side represents clusters of cited publications, reflecting the research foundations of DDE studies. Different colored dots within each cluster indicate the distribution of publications in that cluster. Notably, the arcs spanning the visualization illustrate the citation relationships between publications, with the thickness of the arcs corresponding to the citation volume. These citation trajectories from citing to cited clusters demonstrate the knowledge transfer and intellectual lineage of current DDE research within and across disciplinary boundaries. Notably, the Z-score algorithm converged on those arcs with stronger associations, yielding thicker arcs in green and blue. This indicates that the foundation of DDE research stems from two main disciplinary areas, namely ‘5.

Health, nursing, medicine’ and ‘7. psychology, education, and social on the right side of the figure. Publications from ‘2. MEDICINE, MEDICAL, CLINICAL’ and ‘10. ECONOMICS, ECONOMIC POLITICAL,’ and ‘6. On the left side, PSYCHOLOGY, EDUCATION, and health cite these two disciplinary areas extensively. In other words, the knowledge frontier of DDE research is concentrated in medicine and psychology, and their knowledge bases are also in the domains of health and psychology. However, there is a bidirectional cross-disciplinary citation relationship between the two areas—additionally, the red arcs from the ‘1. MATHEMATICS, SYSTEMS, MATHEMATICAL’ publications cluster showcase another facet of the knowledge frontier in DDE research, as they cite multiple clusters on the right side, forming a divergent structure, which confirms that some of the frontiers of MATHEMATICS in DDE research are based on a broader range of disciplines. The different network structures macroscopically reveal the overall developmental pattern of DDE research.

Discussion

Hotspots and emerging trends

To answer RQ3, based on the research findings, the literature was re-engaged to reveal the research hotspots and emerging trends of DDE. These hotspots and trends are primarily concentrated in the following areas:

Embracing co-design and practical implementation in inclusive and universal design research

Research in inclusive and universal design increasingly emphasizes co-design with stakeholders, reflecting significant growth in publication (Table 4 on Co-design). In the digital context, transitioning from theory to practice in equity-centered design calls for enhanced adaptability and feasibility of traditional design theories. This shift requires a pragmatic and progressive approach, aligning with recent research (Zhang et al., 2023). Furthermore, the evidence-based practices in DDE (Cluster #6) are integral to this dimension, guiding the pragmatic application of design theories.

Focusing on digital mental health and urban-rural inequalities

In DDE, critical issues like the digital divide and mental health are central concerns. The focus on digital and mobile health, highlighted in Fig. 9, shows a shift towards using technology to improve user engagement and address health challenges. As highlighted by Cosco (Cosco et al., 2021), mental health has emerged as a crucial focus in DDE, underscoring the need for designs that support psychological well-being. Additionally, ageism (Mannheim et al., 2023) and stereotypes (Nicosia et al., 2022) influence technology design in DDE, pointing to societal challenges that need addressing for more inclusive digital solutions. Patten’s (Patten et al., 2022) focus on smoking cessation in rural communities indicates a growing emphasis on reducing health disparities, ensuring that digital health advancements are inclusive and far-reaching. These trends in DDE highlight the importance of a holistic approach that considers technological, societal, and health-related factors.

Integration of empathetic, contextualized, and non-visual digital technologies

In the realm of DDE, the technology dimension showcases a range of emerging trends and research hotspots characterized by advancements in immersive technologies, assistive devices, and interactive systems. Technologies like VR (Bortkiewicz et al., 2023) and AR (Creed et al., 2023) are revolutionizing user experiences, offering enhanced empathy and engagement while raising new challenges. The growth in mobile phone usage (Cluster #4) and the development of 3D-printed individualized assistive devices (IADs) (Lamontagne et al., 2023) reflect an increasing emphasis on personalization and catering to diverse user needs. Tangible interfaces (Aguiar et al., 2023) and haptic recognition systems (Lu et al., 2023) make digital interactions more intuitive. The integration of cognitive assistive technology (Roberts et al., 2023) and brain-computer interfaces (BCI) (Padfield et al., 2023) is opening new avenues for user interaction, particularly for those with cognitive or physical limitations. The exploration of Social Assistive Robots (SAR) (Kaplan et al., 2024) and the application of IoT (Almukadi, 2023) illustrate a move towards socially aware and interconnected digital ecosystems, while voice recognition technologies (Berner & Alves, 2023) are enhancing accessibility. Edge computing (Walczak et al., 2023) represents a shift towards decentralized and user-oriented solutions.

For intergenerational relationships, students with disabilities and the visually impaired

The concurrent digitization trends and rapid global aging closely resemble the growth curve of DDE publications, as shown in Fig. 2. The concept of active aging, championed by WHO (World Health Organization 2002), exerts a substantial impact. This effect is evident across multiple indicators, including a significant number of DDE papers published in the journal GERONTOLOGIST (109 articles), the prominent node of “elderly people” in keyword co-occurrence, and the notable mention of “elderly people” in keyword analysis (strength=3.62). Moreover, in 2011, China, the country with the largest elderly population globally, contributed 73 articles related to DDE (Table 2), further emphasizing the growing demand for future DDE research focusing on the elderly. Within DDE studies on the elderly, intergenerational relationships (Li & Cao, 2023) represent an emerging area of research. Additionally, two other emerging trends are centered on the educational and visually impaired populations. The term ‘students with disabilities’ in Fig. 9 illustrates this trend. This is reflected in the focus on inclusive digital education (Lazou & Tsinakos, 2023) and the digital health needs of the visually impaired (Yeong et al., 2021), highlighting the expanding scope of user-centric DDE research.

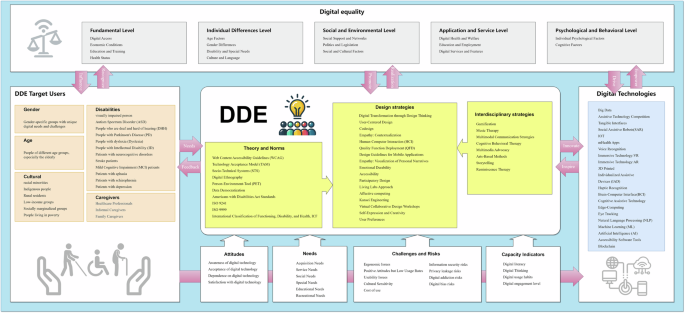

The intellectual structure of DDE

Previous studies have dissected DDE through various disciplinary lenses, often yielding isolated empirical findings. However, a comprehensive synthesis that contemplates the intricate interplay among DDE constructs has yet to be conspicuously absent. To fill this gap and answer RQ4, an intellectual structure that encapsulates the entirety of DDE was developed, amalgamating user demographics, design strategies, interdisciplinary approaches, and the overarching societal implications. This holistic structure, depicted in Fig. 11, The DDE structure elucidates the multi-faceted approach required to achieve digital equity, integrating diverse user needs with tailored design strategies and bridging technological innovation with interdisciplinary methodologies. Its core function is to guide the creation of inclusive digital environments that are accessible, engaging, and responsive to the varied demands of a broad user spectrum.

At the core of discussions surrounding digital equity lies the extensively examined and articulated issue of the digital divide, a well-documented challenge that scholars have explored (Gallegos-Rejas et al., 2023). This is illustrated in the concentric circles of the red core within the keyword contribution analysis, as depicted in Fig. 6. It reflects the persistent digital access and literacy gaps that disproportionately affect marginalized groups. This divide extends beyond mere connectivity to encompass the nuances of social engagement (Almukadi, 2023), where the ability to participate meaningfully in digital spaces becomes a marker of societal inclusion. As noted by (Bochicchio et al., 2023; Jetha et al., 2023), employment is a domain where digital inequities manifest, creating barriers to employment inclusion. Similarly, feelings of loneliness, social isolation (Chung et al., 2023), and deficits in social skills (Estival et al., 2023) are exacerbated in the digital realm, where interactions often require different competencies. These social dimensions of DDE underscore the need for a more empathetic and user-informed approach to technology design, one that can cater to the nuanced needs of diverse populations, including medication reminders and telehealth solutions (Gallegos-Rejas et al., 2023) while minimizing cognitive load (Gomez-Hernandez et al., 2023) and advancing digital health equity (Ha et al., 2023).

The critical element of the DDE intellectual structure is the design strategy, as evidenced by the two categories #0 generic design and #6 participatory design, which contain the most prominent nodes in the keyword clustering in Part IV of this paper. Digital transformation through design thinking (Oliveira et al., 2024), user-centered design (Stawarz et al., 2023), and the co-design of 3D printed assistive technologies (Aflatoony et al., 2023; Benz et al., 2023; Ghorayeb et al., 2023) reflect the trend towards personalized and participatory design processes. Empathy emerges as a recurrent theme, both in contextualizing user experiences (Bortkiewicz et al., 2023) and in visualizing personal narratives (Gui et al., 2023), reinforcing the need for emotional durability (Huang et al., 2023) and accessible design (Jonsson et al., 2023). These approaches are not merely theoretical but are grounded in the pragmatics of participatory design (Kinnula et al., 2023), the living labs approach (Layton et al., 2023), and virtual collaborative design workshops (Peters et al., 2023), all of which facilitate the co-creation of solutions that resonate with the lived experiences of users.

One of the significant distinctions between DDE and traditional fairness-centered design lies in technical specifications. Supporting these strategies are fundamental theories and standards such as the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) (Jonsson et al., 2023), the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) (Alvarez-Melgarejo et al., 2023), and socio-technical systems (STS) (Govers & van Amelsvoort, 2023), which provide the ethical and methodological framework for DDE initiatives. Additionally, digital ethnography (Joshi et al., 2023) and the Person-Environment-Tool (PET) framework (Jarl, Lundqvist 2020) offer valuable perspectives to analyze and design for the intricate interplay of human, technological, and environmental interactions.

Another noteworthy discovery highlighted by the previously mentioned findings is the rich interdisciplinary approach within the field of DDE. This interdisciplinary nature, exemplified by the integration of diverse knowledge domains, is evident in publications analysis of DDE (Table 4) and is visually demonstrated through the overlay of disciplinary citation networks (Fig. 10). Strategies such as gamification (Aguiar et al., 2023), music therapy (Chen & Norgaard, 2023), and multimodal communication strategies (Given et al., 2023) underline the synergistic potential of integrating diverse knowledge domains to foster more inclusive digital environments. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (Kayser et al., 2023), multimedia advocacy (Watts et al., 2023), arts-based methods (Miller & Zelenko, 2022), storytelling (Ostrowski et al., 2021), and reminiscence therapy (Unbehaun et al., 2021) are not merely adjuncts but integral components that enhance the relevance and efficacy of DDE interventions.

Equally important, the relationship between the target users of DDE and digital technologies needs to be focused on as a design strategy. This includes attitudes, needs, challenges, risks, and capacity indicators. Positive outlooks envision digital transformation as a new norm post-pandemic for individuals with disabilities (Aydemir-Döke et al., 2023), while others display varied sentiments (Bally et al., 2023) or even hostile attitudes, as seen in the challenges of visually impaired with online shopping (Cohen et al., 2023). These attitudes interplay with ‘Needs’ that span essential areas, from service to recreational, highlighting the importance of ‘Capacity Indicators’ like digital literacy and digital thinking (Govers & van Amelsvoort, 2023) to bridge these gaps. The ‘Challenges and Risks’ associated with DDE, such as the adverse impacts of apps in medical contexts (Babbage et al., 2023) and ergonomic issues due to immersive technologies (Creed et al., 2023), present barriers that need to be mitigated to foster a conducive environment for digital engagement. Despite a generally positive attitude toward digital transformation, the low usage rates (Dale et al., 2023), usability concerns (Davoody et al., 2023), cultural differences in thinking, and the need for a humanizing digital transformation (Dragicevic et al., 2023b) underscore the complexity of achieving digital equity. The widespread resistance and abandonment of rehabilitative technologies (Mitchell et al., 2023) further emphasize the need for DDE strategies that are culturally sensitive and user-friendly.

Going deeper, the arrows signify dynamic interrelationships among various components within the DDE intellectual structure. “Needs” drive the design and application of “Digital Technologies,” which in turn inspire “Innovative” solutions and approaches. Feedback from these innovations influences “Attitudes,” which, along with “Needs,” can pose “Challenges and Risks,” thereby shaping the “Capacity Indicators” that gauge proficiency in navigating the digital landscape. This cyclical interplay ensures that the DDE framework is not static but an evolving guide responsive to the changing landscape of digital equity.

future research direction

In the process of identifying research gaps and future directions, innovative research opportunities were determined from the results of temporal attributes in the visual, intellectual graph:

Emotional, cultural, and aesthetic factors in human-centered design: Universal Design (UD) and Design for All (DFA) will remain central themes in DDE. However, affective computing and user preferences must be explored (Alves et al., 2020). Beyond functional needs, experiential demands such as aesthetics, self-expression, and creativity, often overlooked in accessibility guidelines, are gaining recognition (Recupero et al., 2021). The concept of inclusive fashion (Oliveira & Okimoto, 2022) underscores the need to address multi-faceted user requirements, including fashion needs, cultural sensitivity, and diversity.

Digital technology adoption and improving digital literacy: The adoption of multimodal and multisensory interactions is gaining increased attention, with a growing focus on voice, tangible, and natural interaction technologies, alongside research into technology acceptance, aligning with the findings (Li et al., 2023). Exploring these interactive methods is crucial for enhancing user engagement and experience. However, there is a notable gap in research on the acceptance of many cutting-edge digital technologies. Additionally, investigating how design strategies can enhance digital literacy represents a valuable study area.

Expanding the Geographic and Cultural Scope: Literature indicates that the situation of DDE in developing countries (Abbas et al., 2014; Nahar et al., 2015) warrants in-depth exploration. Current literature and the distribution of research institutions show a significant gap in DDE research in these regions, especially in rural areas (as seen in Tables 2 and 3 and Figs. 3 and 4). Most research and literature is concentrated in developed countries, with insufficient focus on developing nations. Conversely, within developed countries, research on DDE concerning minority groups (Pham et al., 2022) and affluent Indigenous populations (Henson et al., 2023) is almost nonexistent. This situation reveals a critical research gap: even in economically advanced nations, the needs and preferences of marginalized groups are often overlooked. These groups may face unique challenges and needs, which should be explored or understood in mainstream research.

Multi-disciplinary Research in Digital Equity Design: While publication analysis (Table 4) and knowledge domain flow (Fig. 10) reveal the interdisciplinary nature of DDE, the current body of research predominantly focuses on computer science, medical and health sciences, sociology, and design. This review underscores the necessity of expanding research efforts across a broader spectrum of disciplines to address the diverse needs inherent in DDE adequately. For instance, the fusion of art, psychology, and computer technology could lead to research topics such as “Digital Equity Design Guidelines for Remote Art Therapy.” Similarly, the amalgamation of education, computer science, design, and management studies might explore subjects like “Integrating XR in Inclusive Educational Service Design: Technological Acceptance among Special Needs Students.” These potential research areas not only extend the scope of DDE but also emphasize the importance of a holistic and multi-faceted approach to developing inclusive and accessible digital solutions.

Practical implication

This study conducted an in-depth bibliometric and visualization analysis of the Digital Equity Design (DDE) field, revealing key findings on publication trends, significant contributors and collaboration patterns, key clusters, research hotspots, and intellectual structures. These insights directly affect policy-making, interdisciplinary collaboration, design optimization, and educational resource allocation. Analysis of publication trends provides policymakers with data to support digital inclusivity policies, particularly in education and health services, ensuring fair access to new technologies for all social groups, especially marginalized ones. The analysis of significant contributors and collaboration patterns highlights the role of interdisciplinary cooperation in developing innovative solutions, which is crucial for organizations and businesses designing products for specific groups, such as the disabled and elderly, in promoting active aging policies. Identifying key clusters and research hotspots guides the focus of future technological developments, enhancing the social adaptability and market competitiveness of designs. The construction of intellectual structures showcases the critical dimensions of user experience within DDE and the internal logic between various elements, providing a foundation for promoting deeper user involvement and more precise responses to needs in design research and practice, particularly in developing solutions and assessing their effectiveness to ensure that design outcomes truly reflect and meet end-user expectations and actual use scenarios.

Limitations

Nevertheless, this systematic review is subject to certain limitations. Firstly, the data sourced exclusively from the WOS is a constraint, as specific functionalities like dual-map overlays are uniquely tailored for WOS bibliometric data. Future studies could expand the scope by exploring DDE research in databases such as Scopus, Google Scholar, and grey literature. Additionally, while a comprehensive search string for DDE was employed, the results were influenced by the search timing and the subscription range of different research institutions to the database. Moreover, the possibility of relevant terms existing beyond the search string cannot be discounted. Secondly, despite adhering to the PRISMA guidelines for literature acquisition and screening, subjectivity may have influenced the authors during the inclusion and exclusion process, particularly while reviewing abstracts and full texts to select publications. Furthermore, the reliance solely on CiteSpace as the bibliometric tool introduces another limitation. The research findings are contingent on the features and algorithms of the current version of CiteSpace (6.2.r6 advanced). Future research could incorporate additional or newer versions of bibliometric tools to provide a more comprehensive analysis.

Conclusion

This systematic review aims to delineate the academic landscape of DDE by exploring its known and unknown aspects, including research progress, intellectual structure, research hotspots and trends, and future research recommendations. Before this review, these facets could have been clearer. To address these questions, a structured retrieval strategy set by PICo and a PRISMA process yielded 1705 publications, which were analyzed using CiteSpace for publication trends, geographic distribution of research collaborations, core publications, keyword co-occurrence, emergence, clustering, timelines, and dual-map overlays of publication disciplines. These visual presentations propose a DDE intellectual structure, although the literature data is focused on the WOS database. This framework could serve as a guide for future research to address these crucial issues. The DDE intellectual structure integrates research literature, particularly eight thematic clusters. It not only displays the overall intellectual structure of DDE on a macro level but also reveals the intrinsic logic between various elements. Most notably, as pointed out at the beginning of this review, digital equity, as a critical factor in achieving sustainable development goals, requires human-centered design thinking. An in-depth discussion of the research findings reveals that the development of DDE is characterized by a multi-dimensional approach, encompassing a wide range of societal, technological, and user-specific issues. Furthermore, emerging trends indicate that the future trajectory of DDE will be more diverse and inclusive, targeting a broad spectrum of user needs and societal challenges. Another significant aspect of this review is the proposition of four specific directions for future research, guiding researchers dedicated to related disciplines.

Data availability

The datasets generated or analyzed during the current study are available in the Dataverse repository: https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/S5XXFB.

References

Abbas A, Hussain M, Iqbal M, Arshad S, Rasool S, Shafiq M, Ali W, Yaqub N (2014) Barriers and reforms for promoting ICTs in rural areas of Pakistan. In: Marcus A (ed), pp 391–399

Aflatoony L, Lee SJ, Sanford J (2023) Collective making: Co-designing 3D printed assistive technologies with occupational therapists, designers, and end-users. Assist Technol 35:153–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400435.2021.1983070

Aguiar LR, Rodríguez FJ, Aguilar JR, Plascencia VN, Mendoza LM, Valdez JR, Pech JR, am Leon, Ortiz LE (2023) Implementing gamification for blind and autistic people with tangible interfaces, extended reality, and universal design for learning: two case studies. Appl. Sci.-Basel 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13053159

Ahmad I, Ahmed G, Shah SAA, Ahmed E (2020) A decade of big data literature: analysis of trends in light of bibliometrics. J Supercomput 76:3555–3571. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11227-018-2714-x

Almukadi W (2023) Smart scarf: An IOT-based solution for emotion recognition. Eng Technol Appl Sci Res 13:10870–10874. https://doi.org/10.48084/etasr.5952

Alvarez-Melgarejo M, Pedraza-Avella AC, Torres-Barreto ML (2023) Acceptance assessment of the software MOTIVATIC WEB by university educators. Int J Learn Technol 18:344–363. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJLT.2023.134585

Alves T, Natálio J, Henriques-Calado J, Gama S (2020) Incorporating personality in user interface design: A review. Personality and Individual Differences 155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.109709

Aydemir-Döke D, Owenz M, Spencer B (2023) Being a disabled woman in a global pandemic: A focus group study in the United States and policy recommendations. Disability & Society. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2023.2225207

Babbage, Drown J, van Solkema M, Armstrong J, Levack W, Kayes N (2023) Inpatient trial of a tablet app for communicating brain injury rehabilitation goals. Disabil. Rehabil.-Assist. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1080/17483107.2023.2167009

Bally EL, Cheng DM, van Grieken A, Sanz MF, Zanutto O, Carroll A, Darley A, Roozenbeek B, Dippel DW, Raat H (2023) Patients’ Perspectives Regarding Digital Health Technology to Support Self-management and Improve Integrated Stroke Care: Qualitative Interview Study. J Med Internet Res 25. https://doi.org/10.2196/42556

Bazzano AN, Noel L-A, Patel T, Dominique CC, Haywood C, Moore S, Mantsios A, Davis PA (2023) Improving the engagement of underrepresented people in health research through equity-centered design thinking: qualitative study and process evaluation for the development of the grounding health research in design toolkit. JMIR Form Res 7:e43101. https://doi.org/10.2196/43101

Bendixen K, Benktzon M (2015) Design for all in Scandinavia – A strong concept. Appl Erg 46:248–257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apergo.2013.03.004

Benz C, Scott-Jeffs W, Revitt J, Brabon C, Fermanis C, Hawkes M, Keane C, Dyke R, Cooper S, Locantro M, Welsh M, Norman R, Hendrie D, Robinson S (2023) Co-designing a telepractice journey map with disability customers and clinicians: Partnering with users to understand challenges from their perspective. Health Expect. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.13919

Berner K, Alves (2023) A scoping review of the literature using speech recognition technologies by individuals with disabilities in multiple contexts. Disabil Rehabil -Assist Technol 18:1139–1145. https://doi.org/10.1080/17483107.2021.1986583

Bochicchio V, Lopez A, Hase A, Albrecht J, Costa B, Deville A, Hensbergen R, Sirfouq J, Mezzalira S (2023) The psychological empowerment of adaptive competencies in individuals with Intellectual Disability: Literature-based rationale and guidelines for best training practices. Life Span Disabil 26:129–157. https://doi.org/10.57643/lsadj.2023.26.1_06

Bortkiewicz A, Józwiak Z, Laska-Lesniewicz A (2023) Ageing and its consequences - the use of virtual reality (vr) as a tool to visualize the problems of elderly. Med Pr 74:159–170. https://doi.org/10.13075/mp.5893.01406

Broadus RN (1987) Toward a definition of “bibliometrics. Scientometrics 12:373–379. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02016680

Chen C (2006) CiteSpace II: Detecting and visualizing emerging trends and transient patterns in scientific literature. J Am Soc Inf Sci 57:359–377. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.20317

Chen C (2018) Eugene Garfield’s scholarly impact: a scientometric review. Scientometrics 114:489–516. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-017-2594-5

Chen C, Hu Z, Liu S, Tseng H (2012) Emerging trends in regenerative medicine: a scientometric analysis in CiteSpace. Expert Opin Biol Ther 12:593–608. https://doi.org/10.1517/14712598.2012.674507

Chen YA, Norgaard M (2023) Important findings of a technology-assisted in-home music-based intervention for individuals with stroke: a small feasibility study. Disabil. Rehabil.-Assist. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1080/17483107.2023.2274397

Chung JE, Gendron T, Winship J, Wood RE, Mansion N, Parsons P, Demiris G (2023) Smart Speaker and ICT Use in Relationship With Social Connectedness During the Pandemic: Loneliness and Social Isolation Found in Older Adults in Low-Income Housing. Gerontologist. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnad145

Clarivate (2023) Web of Science Core Collection - Clarivate. https://clarivate.com/products/scientific-and-academic-research/research-discovery-and-workflow-solutions/webofscience-platform/web-of-science-core-collection/. Accessed December 14, 2023

Cohen AH, Fresneda JE, Anderson RE (2023) How inaccessible retail websites affect blind and low vision consumers: their perceptions and responses. J Serv Theory Pract 33:329–351. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSTP-08-2021-0167

Cooper C, Booth A, Varley-Campbell J, Britten N, Garside R (2018) Defining the process to literature searching in systematic reviews: a literature review of guidance and supporting studies. BMC Med Res Methodol 18:85. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0545-3

Cooper BA, Cohen U, Hasselkus BR (1991) Barrier-free design: a review and critique of the occupational therapy perspective. Am J Occup Ther 45:344–350. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.45.4.344

Cosco TD, Fortuna K, Wister A, Riadi I, Wagner K, Sixsmith A (2021) COVID-19, Social Isolation, and Mental Health Among Older Adults: A Digital Catch-22. J Med Internet Res 23. https://doi.org/10.2196/21864

Creed C, Al-Kalbani M, Theil A, Sarcar S, Williams I (2023) Inclusive AR/VR: accessibility barriers for immersive technologies. Univ Access Inf Soc. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10209-023-00969-0

Dale J, Nanton V, Day T, Apenteng P, Bernstein CJ, Smith GG, Strong P, Procter R (2023) Uptake and use of care companion, a web-based information resource for supporting informal carers of older people: mixed methods study. JMIR Aging 6. https://doi.org/10.2196/41185

Davoody N, Eghdam A, Koch S, Hägglund M (2023) Evaluation of an electronic care and rehabilitation planning tool with stroke survivors with Aphasia: Usability study. JMIR Human Factors 10. https://doi.org/10.2196/43861

Dragicevic N, Vladova G, Ullrich A (2023a) Design thinking capabilities in the digital world: A bibliometric analysis of emerging trends. Front Educ 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.1012478

Dragicevic N, Hernaus T, Lee RW (2023b) Service innovation in Hong Kong organizations: Enablers and challenges to design thinking practices. Creat Innov Manag 32:198–214. https://doi.org/10.1111/caim.12555

Estival S, Demulier V, Renaud J, Martin JC (2023) Training work-related social skills in adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder using a tablet-based intervention. Human-Comput Interact. https://doi.org/10.1080/07370024.2023.2242344

Firestone AR, Cruz RA, Massey D (2023) Developing an equity-centered practice: teacher study groups in the preservice context. J Teach Educ 74:343–358. https://doi.org/10.1177/00224871231180536

Gallegos-Rejas VM, Thomas EE, Kelly JT, Smith AC (2023) A multi-stakeholder approach is needed to reduce the digital divide and encourage equitable access to telehealth. J Telemed Telecare 29:73–78. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357633X221107995

Garfield E (2009) From the science of science to Scientometrics visualizing the history of science with HistCite software. J Informetr 3:173–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2009.03.009

Ghorayeb A, Comber R, Gooberman-Hill R (2023) Development of a smart home interface with older adults: multi-method co-design study. JMIR Aging 6. https://doi.org/10.2196/44439

Given F, Allan M, Mccarthy S, Hemsley B (2023) Digital health autonomy for people with communication or swallowing disability and the sustainable development goal 10 of reducing inequalities and goal 3 of good health and well-being. Int J Speech-Lang Pathol 25:72–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549507.2022.2092212

Gomez-Hernandez M, Ferre X, Moral C, Villalba-Mora E (2023) Design guidelines of mobile apps for older adults: systematic review and thematic analysis. JMIR Mhealth and Uhealth 11. https://doi.org/10.2196/43186

Govers M, van Amelsvoort P (2023) A theoretical essay on socio-technical systems design thinking in the era of digital transformation. Gio-Gr -Interakt -Organ -Z Fuer Angew Org Psychol 54:27–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11612-023-00675-8

Grybauskas A, Stefanini A, Ghobakhloo M (2022) Social sustainability in the age of digitalization: A systematic literature Review on the social implications of industry 4.0. Technol Soc 70:101997. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2022.101997

Gui F, Yang JY, Wu QL, Liu Y, Zhou J, An N (2023) Enhancing caregiver empowerment through the story mosaic system: human-centered design approach for visualizing older adult life stories. JMIR Aging 6. https://doi.org/10.2196/50037

Ha S, Ho SH, Bae YH, Lee M, Kim JH, Lee J (2023) Digital health equity and tailored health care service for people with disability: user-centered design and usability study. J Med Internet Res 25. https://doi.org/10.2196/50029

Henson C, Chapman F, Cert G, Shepherd G, Carlson B, Rambaldini B, Gwynne K (2023) How older indigenous women living in high-income countries use digital health technology: systematic review. J Med Internet Res 25. https://doi.org/10.2196/41984

Huang XY, Kettley S, Lycouris S, Yao Y (2023) Autobiographical design for emotional durability through digital transformable fashion and textiles. Sustainability 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054451

Ismail II, Saqr M (2022) A quantitative synthesis of eight decades of global multiple sclerosis research using bibliometrics. Front Neurol 13:845539. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2022.845539

Jarl G, Lundqvist LO (2020) An alternative perspective on assistive technology: The person-environment-tool (PET) model. Assist Technol 32:47–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400435.2018.1467514

Jetha A, Bonaccio S, Shamaee A, Banks CG, Bültmann U, Smith PM, Tompa E, Tucker LB, Norman C, Gignac MA (2023) Divided in a digital economy: Understanding disability employment inequities stemming from the application of advanced workplace technologies. SSM-Qual Res Health 3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmqr.2023.100293

John Clarkson P, Coleman R (2015) History of inclusive design in the UK. Appl Erg 46(Pt B):235–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apergo.2013.03.002

Jonsson M, Johansson S, Hussain D, Gulliksen J, Gustavsson C (2023) Development and evaluation of ehealth services regarding accessibility: scoping literature review. J Med Internet Res 25. https://doi.org/10.2196/45118

Joshi D, Panagiotou A, Bisht M, Udalagama U, Schindler A (2023) Digital Ethnography? Our experiences in the use of sensemaker for understanding gendered climate vulnerabilities amongst marginalized Agrarian communities. Sustainability 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097196

Kaplan A, Barkan-Slater S, Zlotnik Y, Levy-Tzedek S (2024) Robotic technology for Parkinson’s disease: Needs, attitudes, and concerns of individuals with Parkinson’s disease and their family members. A focus group study. Int J Human-Comput Stud 181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2023.103148

Kastrin A, Hristovski D (2021) Scientometric analysis and knowledge mapping of literature-based discovery (1986–2020). Scientometrics 126:1415–1451. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-020-03811-z

Kayser J, Wang X, Wu ZK, Dimoji A, Xiang XL (2023) Layperson-facilitated internet-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy for homebound older adults with depression: protocol for a randomized controlled trial. JMIR Res Protocols 12. https://doi.org/10.2196/44210

King J, Gonzales AL (2023) The influence of digital divide frames on legislative passage and partisan sponsorship: A content analysis of digital equity legislation in the US from 1990 to 2020. Telecommun Policy 47:102573. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.telpol.2023.102573

Kinnula M, Iivari N, Kuure L, Molin-Juustila T (2023) Educational Participatory Design in the Crossroads of Histories and Practices - Aiming for digital transformation in language pedagogy. Comput Support Coop Work- J Collab Comput Work Pract. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10606-023-09473-8

Lamontagne ME, Pellichero A, Tostain V, Routhier F, Flamand V, Campeau-Lecours A, Gherardini F, Thébaud M, Coignard P, Allègre W (2023) The REHAB-LAB model for individualized assistive device co-creation and production. Assist Technol. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400435.2023.2229880

Lawson McLean A, Lawson McLean AC (2023) Exploring the digital divide: Implications for teleoncology implementation. Patient Educ Couns 115:107939. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2023.107939

Layton N, Harper K, Martinez K, Berrick N, Naseri C (2023) Co-creating an assistive technology peer-support community: learnings from AT Chat. Disabil Rehabil -Assist Technol 18:603–609. https://doi.org/10.1080/17483107.2021.1897694

Lazou C, Tsinakos A (2023) Critical Immersive-triggered literacy as a key component for inclusive digital education. Educ Sci 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13070696

Li G, Li D, Tang T (2023) Bibliometric review of design for digital inclusion. Sustainability 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151410962

Li C, Cao M (2023) Designing for intergenerational communication among older adults: A systematic inquiry in old residential communities of China’s Yangtze River Delta. Systems 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems11110528

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D (2009) The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med 6:e1000100. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100

Lu JY, Liu Y, Lv TX, Meng L (2023) An emotional-aware mobile terminal accessibility-assisted recommendation system for the elderly based on haptic recognition. International J Hum–Comput Interact. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2023.2266793

Mace R (1985) Universal design: barrier-free environments for everyone. Design West 33:147–152

Mannheim I, Wouters EJ, Köttl H, van Boekel LC, Brankaert R, van Zaalen Y (2023) Ageism in the discourse and practice of designing digital technology for older persons: a scoping review. Gerontologist 63:1188–1200. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnac144

Miller E, Zelenko O (2022) The Caregiving Journey: Arts-based methods as tools for participatory co-design of health technologies. Social Sci-Basel 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11090396

Mitchell J, Shirota C, Clanchy K (2023) Factors that influence the adoption of rehabilitation technologies: a multi-disciplinary qualitative exploration. J NeuroEng Rehabil 20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12984-023-01194-9

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG (2010) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg 8:336–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.007

Nahar L, Jaafar A, Ahamed E, Kaish A (2015) Design of a Braille learning application for visually impaired students in Bangladesh. Assist Technol 27:172–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400435.2015.1011758

Nicosia J, Aschenbrenner AJ, Adams SL, Tahan M, Stout SH, Wilks H, Balls-Berry JE, Morris JC, Hassenstab J (2022) Bridging the technological divide: stigmas and challenges with technology in digital brain health studies of older adults. Front Digit Health 4. https://doi.org/10.3389/fdgth.2022.880055

Nishikawa-Pacher A (2022) Research questions with PICO: A universal mnemonic. Publications 10:21. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications10030021

Oliveira M, Zancul E, Salerno MS (2024) Capability building for digital transformation through design thinking. Technol Forecast Soc Change 198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2023.122947

de Oliveira RD, Okimoto M (2022) Fashion-related assistive technologies for visually impaired people: a systematic review. Dobras:183–205

Oliveri ME, Nastal J, Slomp D (2020) Reflections on Equity‐Centered Design. ETS Research Report Series 2020:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1002/ets2.12307

Ostrowski AK, Harrington CN, Breazeal C, Park HW (2021). Personal narratives in technology design: the value of sharing older adults’ stories in the design of social robots. Front Robot AI 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/frobt.2021.716581

Padfield N, Anastasi AA, Camilleri T, Fabri S, Bugeja M, Camilleri K (2023). BCI-controlled wheelchairs: end-users’ perceptions, needs, and expectations, an interview-based study. Disabil. Rehabil.-Assist. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1080/17483107.2023.2211602

Park K, So H-J, Cha H (2019) Digital equity and accessible MOOCs: Accessibility evaluations of mobile MOOCs for learners with visual impairments. AJET 35:48–63. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.5521

Patten C, Brockman T, Kelpin S, Sinicrope P, Boehmer K, St Sauver J, Lampman M, Sharma P, Reinicke N, Huang M, McCoy R, Allen S, Pritchett J, Esterov D, Kamath C, Decker P, Petersen C, Cheville A (2022) Interventions for Increasing Digital Equity and Access (IDEA) among rural patients who smoke: Study protocol for a pragmatic randomized pilot trial. Contemp Clin Trials 119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2022.106838

Persson H, Åhman H, Yngling AA, Gulliksen J (2015) Universal design, inclusive design, accessible design, design for all: different concepts—one goal? On the concept of accessibility—historical, methodological and philosophical aspects. Univ Access Inf Soc 14:505–526. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10209-014-0358-z

Peters D, Sadek M, Ahmadpour N (2023) Collaborative workshops at scale: a method for non-facilitated virtual collaborative design workshops. Int J Hum–Comput Interact. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2023.2247589

Pham Q, El-Dassouki N, Lohani R, Jebanesan A, Young K (2022) The future of virtual care for older ethnic adults beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. J Med Internet Res 24. https://doi.org/10.2196/29876

Ping Q, He J, Chen C (2017) How many ways to use CiteSpace? A study of user interactive events over 14 months. Assoc Info Sci Tech 68:1234–1256. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.23770

Price DDS (1963) Science since Babylon. Philos Sci 30:93–94