Abstract

Anxiety sensitivity refers to an individual’s belief that anxiety symptoms adversely affect physical, cognitive, and social appraisals, thereby exacerbating the fear of these symptoms. The Anxiety Sensitivity Index-3 (ASI-3) has been widely used to measure anxiety sensitivity. To provide researchers with more flexibility in selecting scale lengths, this study developed two shortened versions of the ASI-3 via item response theory analysis: one containing 12 items and the other containing six items. Given the overall good quality of the original scale, this study primarily achieved scale shortening by retaining items that could provide a substantial amount of item information, namely, items of high measurement precision. Compared to the original scale, the two shortened versions demonstrate good reliability while maintaining the same three-dimensional latent structure, robust inter-construct relationships, and highly correlated latent traits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Anxiety sensitivity refers to an individual’s belief that anxiety symptoms adversely affect physical, cognitive, and social appraisals, thereby exacerbating the fear of these symptoms (Reiss 1991; Wang et al. 2014). Unlike anxiety traits, which focus on the severity of an individual’s anxiety symptoms, anxiety sensitivity pertains to an individual’s fear or misunderstanding of anxiety symptoms, potentially intensifying their anxiety experience and amplifying their anxiety responses (Naragon-Gainey 2010). Anxiety sensitivity is considered a personality trait that remains stable over time but has been shown to decrease with targeted interventions (Smits et al. 2008). Objective and accurate measurement using a high-quality instrument is a necessary prerequisite for implementing such interventions.

Existing instruments for measuring anxiety sensitivity mainly include the Anxiety Sensitivity Index (ASI; Reiss et al. 1986), the ASI-Revised (Taylor and Cox 1998), and the ASI-3 (Taylor et al. 2007), among others. Different studies have found that the ASI and ASI-Revised have unstable latent structures (Taylor 1999; Zvolensky et al. 2003). In contrast, the ASI-3 demonstrates good reliability and a stable latent structure compared to the ASI and ASI-Revised (Kemper et al. 2012). It has been widely utilized in multinational studies involving college student populations and patients with anxiety disorders (Haas et al. 2019; McLeish et al. 2023; Stevens et al. 2021).

As research questions grow increasingly complex, studies are less frequently relying on single scales alone, with multiple scales being used simultaneously to explore relationships between anxiety sensitivity and other psychological constructs (Viana et al. 2018; Yazar and Meterelliyoz 2021). In such cases, short yet reliable versions of scales have garnered increased attention from researchers. Typically, without significantly compromising reliability, shortened scales can reduce response time, increase response rates, and enhance the efficiency of data collection (Ziegler et al. 2014; Zsido et al. 2020).

Currently, a limited number of studies have developed a short version of the ASI-3 and investigated its psychometric properties in various clinical samples (Clark et al. 2024; Zvolensky et al. 2018), underscoring the practical need for a shortened version of the ASI-3. Two primary reasons prompted the development of a new shortened scale of the ASI-3. Firstly, existing shortened scales derived from clinical samples may not be suitable for use in studies involving normal samples, such as college students (e.g., Haas et al. 2019; McLeish et al. 2023), posing challenges in studying the relationship between anxiety sensitivity and other constructs in a non-clinical setting. Secondly, previous efforts to develop shortened scales have exhibited methodological shortcomings, including but not limited to employing ambiguous statistical analyses based on classical test theory and factor analysis. Recently, the necessity of employing modern statistical techniques, such as item response theory (IRT; Embretson and Reise, 2013), to examine the psychometric properties of scales has become increasingly apparent (Sharp et al. 2022; Zsido et al. 2020).

One of the significant advantages of Item Response Theory (IRT) over classical test theory is its capability to estimate item-level measurement precision, also known as item-level reliability. Employing IRT to shorten existing scales presents the opportunity to retain more informative items, specifically those with high reliability, thereby ensuring the overall scale’s reliability while enhancing efficiency (Zsido et al. 2020). Additionally, unlike classical test theory and factor analysis, which assume a linear relationship between latent traits (constructs) and observed behavior, IRT posits a non-linear relationship between the two, which is more reflective of reality.

To our knowledge, no study has utilized IRT analysis to refine the ASI-3 and subsequently employed this additional information to create a shortened version comprising only items with the most desirable properties. Therefore, the primary aim of this study was to develop shortened ASI-3 scales that maintain robust psychometric properties. To achieve this objective, IRT analysis was conducted to identify and retain the most optimal items.

Methods

Participants

By adopting convenience sampling, we obtained data from 1216 Chinese participants, of whom 453 (37.3%) were male and 763 (62.7%) were female, aged between 16 and 23 years (M = 19.14, SD = 0.977). All participants were freshmen and sophomores, not clinical samples. For this study, participants were randomly divided into two equal-sized sub-samples: the development sample (N = 608) and the validation sample (N = 608). The development sample was utilized to create the shortened scale, while the validation sample was employed to assess the psychometric properties of the shortened scale. Table 1 presents a brief descriptive statistical of the dataset.

Instruments

Anxiety Sensitivity Index-3 (ASI-3)

The ASI-3 is an 18-item self-report instrument designed to assess three dimensions of anxiety sensitivity: physical concern (e.g., “When my stomach is upset, I worry that I might be seriously ill.”), cognitive concern (e.g., “It scares me when I am unable to keep my mind on a task.”), and social concern (e.g., “I worry that other people will notice my anxiety.”). Each dimension comprises six items scored on a 5-point scale, ranging from 0 (“I agree very little”) to 4 (“I agree very much”). The total score reflects the individual’s level of anxiety sensitivity, with higher scores indicating greater sensitivity to anxiety. The internal consistency of the scale has been assessed across different countries, with Cronbach’s α coefficients for each sub-scale falling within acceptable limits (Fergus et al. 2017).

In this study, we utilized the Chinese version of the ASI-3 (Wang et al. 2014), which underwent translation without any item deletions, only incorporating suitable embellishments to align with the Chinese cultural context. The total score and scores for each respective sub-scale of the Chinese ASI-3 demonstrated robust internal consistency (total score: α = 0.95, physical sub-scale: α = 0.90, cognitive sub-scale: α = 0.90, social sub-scale: α = 0.84). Online Appendix C presents the percentage of participants for each option in all items.

Instruments used for convergent validity

An essential aspect of developing a shortened version of any scale is to replicate the established pattern of relationships with other constructs observed in the original scale (Chiesi et al. 2018; Smith et al. 2000). In this study, two instruments were employed to validate the robustness of relationships between anxiety sensitivity and negative emotions (Kashdan 2007; Kashdan and Collins 2010), as well as between anxiety sensitivity and depressive traits (Naragon-Gainey 2010).

First, the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) is a 20-item measure consisting of two dimensions (positive and negative emotions) assessed on a 5-point scale. The PANAS has demonstrated good internal consistency (total score: α = 0.82, positive emotion sub-scale: α = 0.85, negative emotion sub-scale: α = 0.83) (Huang et al. 2003). In this study, we utilized the sub-scale for negative emotions, which exhibited good internal consistency reliability (α = 0.87). Second, the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) is a 9-item measure with two dimensions (affective and somatic symptoms) rated on a 4-point scale. The internal consistency reliability of the PHQ-9 in this study was also good (α = 0.83).

Analysis

Development of shortened scales

The short version of the original ASI-3 was developed based on the results of the IRT analysis. In this study, the mirt package (Chalmers 2012) in R software was utilized to conduct various aspects of IRT analysis, including model-data fit testing, item fit testing, detection of differential item functioning (DIF), estimation of item parameters, and calculation of item information. It is important to note that, in addition to confirming the latent structure of the scale through model-data fit testing, each analysis result can provide suggestions for item deletion, which will be comprehensively considered in determining the final items to be removed. This part of the analysis was conducted using the development sample.

Model-data fit testing

Since the ASI-3 employs a 5-point scale with three dimensions, three commonly used multidimensional IRT models were used to analyze the data: the multidimensional graded response model (MGRM; Muraki and Carlson 1993), the multidimensional generalized partial credit model (MGPCM; Yao and Schwarz 2006), and the multidimensional nominal response model (MNRM; Takane and de Leeuw 1987). The number of dimensions was set to three. The relative model-data fit indices—Akaike information criterion (AIC; Akaike 1981), Bayesian information criterion (BIC; Schwarz 1978), and sample size adjusted BIC (SABIC; Sclove, 1987)—were computed for optimal model selection. Models with smaller AIC, BIC, and SABIC values fit the data better. Three absolute model-data fit indices—root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), and comparative fit index (CFI)—were utilized to assess the fit of the MGRM to the data. Typically, values of RMSEA < 0.08, TLI > 0.95, and CFI > 0.95 indicate a good fit of the model to the data (Browne and Cudeck 1992; Hu and Bentler 1999).

Item deletion via item fit testing

In IRT, the fit of each item to the data can be assessed, which is crucial for item quality monitoring and scale reduction purposes. In this study, the S-χ2 index was employed to evaluate the degree of item fit by comparing whether there is a significant difference between the model-predicted response and the observed response to an item. Items were considered for reduction if they significantly deviated from the expected fit to the data (p < 0.001) (Flens et al. 2017).

Item deletion via DIF detection

DIF occurs when participants from different groups (e.g., gender and ethnicity) with comparable abilities have different probabilities of responding to an item correctly on a multi-item scale, which can compromise the fairness and validity of the measurement. Previous studies have shown that females score significantly higher than males on anxiety sensitivity (Jurin et al. 2012). In this study, McFadden’s pseudo-R² statistic was employed to detect DIF for each item with respect to gender grouping. The lordif package in R (Choi et al. 2011), which uses a flexible iterative hybrid ordinal logistic regression framework, was used for this examination. A value of R2 > 0.02 indicates the presence of DIF in the item and warrants consideration for reduction (Choi et al. 2011; Crane et al. 2006).

Item deletion via item parameter estimation

IRT models enable items to relate differentially to latent traits through item discrimination and step-difficulty parameters. Within a specific sub-dimension, the discrimination parameter reflects an item’s capacity to differentiate between participants with varying levels of the latent trait; a higher discrimination parameter indicates better discriminatory ability of an item. Typically, items with low discrimination (less than 1) may be considered for reduction (Zickar et al. 2002). In addition, the step-difficulty parameters of each item should be evenly distributed across the participants’ ability levels to allow for better differentiation between individuals with varying abilities (Chiesi et al. 2018).

Item deletion via item information

Using the estimated item parameters, IRT models provide the amount of information provided by each item (aggregating all items’ information yields the test information of the scale), which reflects the measurement precision offered by the item across different levels of latent traits. For a given participant, higher information provided by an item corresponds to higher measurement precision. When considering item deletion, there is a tendency to retain informative items that provide high levels of information for participants across a wide range of latent traits.

Building on previous studies (Huang et al. 2017; Liu et al. 2022), this study considered methods for shortening the scale, focusing on item information from two perspectives. First, we shortened each sub-scale of the original ASI-3 by selecting items that offered above-average information. Assuming equal measurement precision for each item in a 6-item sub-scale, each item should provide 16.7% of the total information of the sub-scale (i.e., 100% divided by 6 items). Hence, scale shortening was achieved by removing items with below-average measurement precision. Second, to provide researchers with more flexibility in selecting scale lengths, the original ASI-3 was further condensed by selecting the most informative items that, collectively, retained at least 30% of the total information of each sub-scale. In other words, for each sub-scale, we retained items with the highest percentages of information until the sum of item information equaled or exceeded 30%.

Exploring the psychometric properties of shortened scales

To investigate the psychometric properties of the shortened scales, we computed internal consistency reliability and assessed validity evidence, including latent structure-based validity and convergent validity. This portion of the analysis was conducted using the validation sample.

Reliability

First, internal consistency reliability was computed for both the shortened and original scales. Due to the potential bias of Cronbach’s α coefficient in tests with few items (Ziegler et al. 2014), both Cronbach’s α coefficient and McDonald’s ω coefficient were calculated (Wang et al. 2023).

Second, the test information was computed for both the shortened and original scales. Across the entire range of latent traits of interest (e.g., −5 to 5 on the logit scale), a higher amount of test information corresponds to a higher degree of measurement precision (i.e., reliability). The test information curve facilitates comparison of the range of latent traits measured by the shortened and original scales; if the curves of the shortened scale and the original scale cover a similar range of latent traits, it indicates that the shortened scale does not miss the range of applicability of the measurement but may exhibit decreased precision.

Validity

First, evidence of latent structure-based validity was established by verifying that the shortened scales maintain the three-dimensional latent structure of the original scale. Data were analyzed separately for the two shortened scales and the original scale using the MGRM. A good fit of the model to the data indicates that the scale data encompass the three-dimensional latent structure.

Second, convergent validity was assessed by computing the correlation between the latent trait estimates of the dimensions of the shortened and original scales, derived using the MGRM. Typically, a correlation exceeding 0.85 between two variables suggests they measure the same construct (Kenny 1979).

Third, convergent validity was further established by assessing the consistency of the shortened scale in relation to the pattern of relationships between the construct measured by the original scale and other constructs. If the correlation coefficients between the scores of the shortened scale and the scores of the other constructs closely resemble those of the original scale, it suggests that the shortened scale did not alter the construct measured by the original scale.

Results

Results of scale shortening

Table 2 presents the model-data fit indices. First, the MGPCM and MGRM exhibited good fits to the data according to the absolute model-data fit indices, confirming the three-dimensional latent structure of the ASI-3. Second, all three relative model-data fit indices tend to select the MGRM as the best-fitting model. Therefore, subsequent analyses were conducted based on the MGRM.

Table 3 presents the results of item parameters, item fit testing, DIF detection, and item information for the original 18 items. Firstly, the results of item fit testing (S-χ2) indicated that all items fit the data well, thus no item deletion was warranted based on this index. Secondly, the results of DIF detection (R2) revealed that all items met the local independence assumption except for item 1 (‘It is important for me not to appear nervous’), suggesting that item 1 could be considered for deletion according to this index. Thirdly, the results of item parameter estimations indicated that the discrimination parameter exceeded 1 for all items except item 1, further suggesting item 1 as a candidate for deletion based on this index. Fourthly, the item step-difficulty parameters for all items were monotonically increasing and evenly spaced, covering the main areas of values on the logit scale. In summary, due to the generally high quality of the original scale (with only one item of low quality), effective scale shortening through removal of low-quality items alone was not feasible. Therefore, we turned to utilizing item information to streamline the scale.

Item information curves of all items in the original scales were displayed in Online Appendix A. We initially shortened each sub-scale of the original ASI-3 by selecting items that provided above-average information (i.e., 16.7%). For the physical sub-scale, items 7, 8, 12, and 15 were retained; for the social sub-scale, items 6, 9, 11, and 13 were retained; and for the cognitive sub-scale, items 10, 14, 16, and 18 were retained. This yielded a 12-item shortened ASI-3 (referred to as SASI-12). Additionally, we further shortened each sub-scale by selecting the most informative items, ensuring that they collectively retained at least 30% of the total information of each sub-scale. For the physical sub-scale, items 7 and 8 were retained, as they offered 43.7% of the information for this sub-scale; for the social sub-scale, items 9 and 13 were retained, providing 52.6% of the information for this sub-scale; and for the cognitive sub-scale, items 14 and 18 were retained, offering 46.5% of the information for this sub-scale. This resulted in a 6-item shortened ASI-3 (referred to as SASI-6).

Overall, we developed two short versions of the ASI-3: the SASI-12 and SASI-6. Specific items of the two shortened scales can be found in the Online Appendix B.

Psychometric properties of shortened scales

Table 4 presents the internal consistency reliabilities of the two shortened scales and the original scale. Firstly, not only was there no obvious decrease in the reliability of the SASI-12 compared to the ASI-3, but there was also a slight improvement in the Physical sub-scale. This may be the result of deleting some items with relatively low measurement precision. Secondly, as the number of items further decreases, the reliability of both the SASI-6 and its sub-scales showed a slight decline.

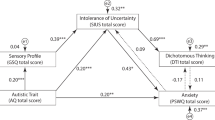

Figure 1 displays the test information curve of the two shortened scales and the original scale (item information curves of all items in the two shortened and the original scales were displayed in Online Appendix A). The curves cover a similar range of latent traits, indicating that the two shortened scales do not miss the range of applicability of the measurement but rather exhibit decreased precision.

Table 5 presents the model-data fit of the two shortened scales and the original scale. The results indicate that the two shortened scales maintain the same three-dimensional latent structure as the original scale, and that the results of the model-based analysis accurately reflect the underlying patterns embedded in the data.

Table 6 presents the correlations between latent trait (i.e., anxiety sensitivity) estimates of sub-dimensions of the two shortened scales and the original scale. The correlation coefficients were sufficiently high to provide evidence that the two shortened scales measure the same latent trait as the original scale.

Table 7 presents the correlations between the raw scores of the two shortened scales and the original scale, as well as those of the other two scales. A comparison revealed that the two shortened scales essentially maintain the pattern of relationships with other constructs observed in the original scale.

Conclusion and discussion

To provide researchers with greater flexibility in selecting scale lengths, this study utilized IRT analysis to develop two shortened scales of the ASI-3: SASI-12 and SASI-6, comprising 12 and six high-quality informative items, respectively. Given the overall good quality of the original scale, the primary approach to scale shortening involved retaining items that offered substantial item information (i.e., items with high measurement precision). In comparison to the original scale, the two shortened scales maintain good reliability while preserving the same three-dimensional latent structure, robust inter-construct relationships, and highly correlated latent trait.

In practice, we recommend that researchers select between the two shortened scales based on their specific needs: if the aim is to reduce test time while maintaining measurement precision, we recommend using SASI-12. Conversely, if the goal is to minimize test time while ensuring a feasible level of measurement precision, SASI-6 is the preferred option.

Anxiety sensitivity has a prospective predictive role in the onset of anxiety disorders. The development of the short version of the ASI-3 can help individuals quickly and accurately understand their level of anxiety sensitivity, providing a reference for the diagnosis of anxiety and facilitating the timely adoption of relevant alleviation measures. Understanding one’s anxiety sensitivity is particularly beneficial for individuals with mild anxiety, as they might overlook anxiety-related measurements. A concise and reliable scale can reduce the time and burden of assessment, making these individuals more willing to participate in evaluations, thereby increasing compliance. This allows for a quicker understanding of their anxiety sensitivity levels, enabling them to take effective measures for alleviation.

Despite yielding promising results, this study has several limitations. Firstly, the sample of participants was conveniently selected from a single college in China, potentially impacting the ecological validity of the developed shortened scales. In the future, cross-sample or cross-cultural studies could be pursued to further validate the validity of the SASI-12 and SASI-6. Secondly, unlike existing studies conducted on clinical samples (e.g., Clark et al. 2024; Zvolensky et al. 2018), while this study aimed to develop shortened scales of ASI-3 based on non-clinical samples, future research could explore the psychometric properties of the two shortened scales developed in this study within clinical samples.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Akaike H (1981) Likelihood of a model and information criteria. J Econom 16(1):3–14

Browne MW, Cudeck R (1992) Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociological Methods Res 21(2):230–258

Chalmers RP (2012) mirt: A multidimensional item response theory package for the R environment. J Stat Softw, 48:1–29

Chiesi F, Morsanyi K, Donati MA, Primi C (2018) Applying item response theory to develop a shortened version of the need for cognition scale. Adv Cogn Psychol 14(3):75–86

Choi SW, Gibbons LE, Crane PK (2011) Lordif: An R package for detecting differential item functioning using iterative hybrid ordinal logistic regression/item response theory and Monte Carlo simulations. J Stat Softw 39(8):1–30

Clark HL, Dixon LJ, Ramachandran S, Leukel P, Lee AA (2024) Psychometric properties of the short scale anxiety sensitivity index among adults with chronic respiratory disease. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 31:186–196

Crane PK, Gibbons LE, Jolley L, van Belle G (2006) Differential item functioning analysis with ordinal logistic regression techniques: DIFdetect and difwithpar. Med Care, 44(11):S115–S123

Embretson SE, Reise SP (2013) Item response theory. Psychology Press, New York

Fergus TA, Kelley LP, Griggs JO (2017) Examining the ethnoracial invariance of a bifactor model of anxiety sensitivity and the incremental validity of the physical domain-specific factor in a primary-care patient sample. Psychological Assess 29(10):1290–1295

Flens G, Smits N, Terwee CB, Dekker J, Huijbrechts I, de Beurs E (2017) Development of a computer adaptive test for depression based on the Dutch-Flemish version of the PROMIS item bank. Evaluation Health Prof 40(1):79–105

Haas AR, Forkus SR, Contractor AA, Weiss NH (2019) Posttraumatic symptomatology and alcohol misuse among black college students: examining the influence of anxiety sensitivity. J Dual Diagnosis 15(1):25–35

Hu LT, Bentler PM (1999) Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model A Multidiscip J 6(1):1–55

Huang L, Yang Y, Li Z (2003) Applicability of the Positive and Negative Affect Scale in Chinese. Chin Ment Health J 17(1):54–56

Huang YH, Lee J, Chen Z, Perry M, Cheung JH, Wang M (2017) An item-response theory approach to safety climate measurement: the Liberty Mutual Safety Climate Short Scales. Accid Anal Prev 103:96–104

Jurin T, Jokic-Begic N, Korajlija AL (2012) Factor structure and psychometric properties of the anxiety sensitivity index in a sample of Croatian adults. Assessment 19(1):31–41

Kashdan TB (2007) Social anxiety spectrum and diminished positive experiences: theoretical synthesis and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 27(3):348–365

Kashdan TB, Collins RL (2010) Social anxiety and the experience of positive emotion and anger in everyday life: an ecological momentary assessment approach. Anxiety Stress Coping 23(3):259–272

Kemper CJ, Lutz J, Bähr T, Rüddel H, Hock M (2012) Construct validity of the anxiety sensitivity index-3 in clinical samples. Assessment 19(1):89–100

Kenny DA (1979) Correlation and causality. Wiley, New York

Liu DT, Phillips KM, Speth MM, Besser G, Mueller CA, Sedaghat AR (2022) Exploring possibilities for shortening the 22-item Sino-Nasal Outcome Test (SNOT-22) using item response theory. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol 12(2):191–199. FebruaryIn

McLeish AC, Hartson KR, Walker KL, Hart JL (2023) Associations between sleep disturbance, physical activity, and anxiety sensitivity among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Health Med 28(9):2512–2525

Muraki E, Carlson JE (1993) Full-information factor analysis for polytomous item responses. Paper Presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Atlanta

Naragon-Gainey K (2010) Meta-analysis of the relations of anxiety sensitivity to the depressive and anxiety disorders. Psychological Bull 136(1):128–150

Reiss S (1991) Expectancy model of fear, anxiety, and panic. Clin Psychol Rev 11(2):141–153

Reiss S, Peterson RA, Gursky DM, McNally RJ (1986) Anxiety sensitivity, anxiety frequency and the prediction of fearfulness. Behav Res Ther 24(1):1–8

Schwarz G (1978) Estimating the dimension of a model. Ann Stat 461–464

Sclove SL (1987) Application of model-selection criteria to some problems in multivariate analysis. Psychometrika 52:333–343

Sharp C, Steinberg L, McLaren V, Weir S, Ha C, Fonagy P (2022) Refinement of the reflective function questionnaire for youth (RFQY) scale B using item response theory. Assessment 29(6):1204–1215

Smith GT, McCarthy DM, Anderson KG (2000) On the sins of short-form development. Psychological Assess 12(1):102–111

Smits JA, Berry AC, Tart CD, Powers MB (2008) The efficacy of cognitive-behavioral interventions for reducing anxiety sensitivity: A meta-analytic review. Behav Res Ther 46(9):1047–1054

Stevens ES, Behar E, Siev J (2021) The roles of disgust sensitivity and anxiety sensitivity in attentional bias in dental anxiety. J Anxiety Disord 83:102450

Takane Y, de Leeuw J (1987) On the relationship between item response theory and factor analysis of discretized variables. Psychometrika 52:393–408

Taylor S (1999) Anxiety sensitivity: Theory, research, and treatment of the fear of anxiety. Erlbaum, Mahwah, NJ

Taylor S, Cox BJ (1998) An expanded anxiety sensitivity index: evidence for a hierarchic structure in a clinical sample. J Anxiety Disord 12(5):463–483

Taylor S, Zvolensky MJ, Cox BJ, Deacon B, Heimberg RG, Ledley DR et al. (2007) Robust dimensions of anxiety sensitivity: development and initial validation of the anxiety sensitivity index-3. Psychological Assess 19(2):176–188

Viana AG, Woodward EC, Hanna AE, Raines EM, Alfano CA, Zvolensky MJ (2018) The moderating role of anxiety sensitivity in the co-occurrence of anxiety and depression symptoms among clinically anxious children. J Exp Psychopathol 9(3):2043808718791049

Wang L, Liu WT, Zhu XZ, Wang YP, Li LY, Yang YL, Ryder AG (2014) Validity and reliability of the Chinese Version of the Anxiety Sensitivity Index-3 in healthy adult women. Chin Ment Health J 28(10):767–771

Wang X, Cai Y, Tu D (2023) The application of item response theory in developing and validating a shortened version of the Rotterdam Emotional Intelligence Scale. Curr Psychol 42(26):22949–22964

Yao L, Schwarz RD (2006) A multidimensional partial credit model with associated item and test statistics: An application to mixed-format tests. Appl Psychological Meas 30(6):469–492

Yazar MS, Meterelliyoz KŞ (2021) Anxiety Sensitivity and Its Relation to Anxiety in Multiple Sclerosis. Psychiatry Clin Psychopharmacol 31(4):434–441

Zickar MJ, Russell SS, Smith CS, Bohle P, Tilley AJ (2002) Evaluating two morningness scales with item response theory. Personal Individ Differences 33(1):11–24

Ziegler M, Kemper CJ, Kruyen P (2014) Short scales-five misunderstandings and ways to overcome them. J Individ Differences 35(4):185–189

Zsido AN, Teleki SA, Csokasi K, Rozsa S, Bandi SA (2020) Development of the short version of the spielberger state—trait anxiety inventory. Psychiatry Res 291:113223

Zvolensky MJ, Arrindell WA, Taylor S, Bouvard M, Cox BJ, Stewart SH, Eifert GH (2003) Anxiety sensitivity in six countries. Behav Res Ther 41(7):841–859

Zvolensky MJ, Garey L, Fergus TA, Gallagher MW, Viana AG, Shepherd JM, Schmidt NB (2018) Refinement of anxiety sensitivity measurement: The short scale anxiety sensitivity index (SSASI). Psychiatry Res 269:549–557

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yikun Luo: Writing-original draft, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Qipeng Chen: Formal analysis. Jianyong Chen: Data acquisition, Writing-review & editing. Peida Zhan: Supervision, Writing-review & editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The ethical approval was acquired from the Ethics Committee of Zhejiang Normal University (ZSRT2024173).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Luo, Y., Chen, Q., Chen, J. et al. Development and validation of two shortened anxiety sensitive index-3 scales based on item response theory. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 1078 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03615-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03615-z