Abstract

This study investigates how artificial intelligence (AI) perpetuates gender stereotypes in the accounting profession. Through experiments employing large language models (LLMs), we scrutinize how these models assign gender labels to accounting job titles. Our findings reveal differing tendencies among LLMs, with one favouring male labels, another female labels, and a third showing a balanced approach. Statistical analyses indicate significant disparities in labelling patterns, and job titles classified as male are associated with higher salary ranges, suggesting gender-related bias in economic outcomes. This study reaffirms existing literature on gender stereotypes in LLMs and uncovers specific biases in the accounting context. It underscores the transfer of biases from the physical to the digital realm through LLMs and highlights broader implications across various sectors. We propose raising public awareness as a means to mitigate these biases, advocating for proactive measures over relying solely on human intervention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As per White and White (2006), many individuals have traditionally adhered to the notion that certain jobs are more appropriate or common for men or women due to occupational stereotypes. One of the early research studies that delved in to gender stereotypes related to occupations was carried out by Shinar (1975). This study revealed that college students believed certain professions necessitated masculine attributes, while others called for feminine qualities. These stereotypes have implications beyond mere perceptions, often exerting detrimental influence on individuals’ career decisions and access to opportunities, such as job segregation (Clarke 2020), wage gaps (Arceo-Gomez et al. 2022) and career progression barriers (Tabassum and Nayak 2021).

In the field of accounting, research findings have indicated disparities in the perception of occupational stereotypes. Some studies have suggested that accounting is predominantly considered a male-dominated domain, while others have argued that it is a female-majority profession. For example, White and White (2006) found that people think of accounting as more of a male profession than they openly say, showing a difference between hidden and open views. Similarly, Alev et al. (2010) highlighted significant differences in the stereotypes of male and female accountants in Turkey, a country where the profession is male-dominated. Nabil et al. (2022) further emphasized the influence of patriarchal values and perceptions of the accounting work environment as more suitable for men, contributing to gender stereotyping in accounting education. On the other hand, Kabalski (2022) identified the belief that accounting is a profession for women, complete with specific stereotypes about the qualities required for the job.

This study contributes to the existing body of research on occupational stereotypes in accounting by introducing a novel dimension. Specifically, our research question is: “does AI perpetuates stereotypes within the accounting profession, and if so, in what manner”. To address this question, we have designed experiments which examine how LLMs classify job titles within the accounting profession into different genders. The rationale for the research design, including the selection of job title classifications and the focus on LLMs is explained below.

We have chosen to explore the classification of job titles in this research because job titles encapsulate fundamental aspects of a profession’s identity and expectations. Job titles often serve as the initial point of reference when individuals evaluate potential career choices and they bear cultural and historical connotations that can either reinforce or challenge prevailing occupational stereotypes. By examining how LLMs categorize job titles, our research illuminates the implicit associations that are established between specific roles and gender.

Furthermore, our study specifically concentrates on LLMs rather than conducting experiments based on established LLM-powered AI platforms such as ChatGPT, Microsoft Bing, Google Bard and others. This choice is grounded in the recognition that LLMs serve as the foundational layer of AI language processing and generation. LLMs are trained on extensive datasets, often reflecting societal biases inherent in language usage. Consequently, these models assume a pivotal role in shaping the linguistic and cognitive frameworks that form the basis for decision-making processes within AI systems. By delving into the inner workings of LLMs, our research seeks to attain a deeper understanding of how biases and stereotypes permeate AI systems.

Overall, the rationale behind this research lies in the potential implications for both AI technology and societal perceptions. By examining how various LLMs classify accounting job titles, we can gain valuable insights into the prevalence and variations of gender-related biases within AI systems. Furthermore, this research offers an opportunity to expand our understanding of the evolving landscape of occupational stereotypes and their interaction with recent AI technologies. Ultimately, this study seeks to contribute new knowledge to the fields of gender studies, AI ethics and occupational psychology with the goal of fostering more inclusive and unbiased environments in both the workplace and the realm of AI.

Stereotypes in LLM

Previous studies have indicated that LLMs are not immune to perpetuating gender bias and stereotypes. As per the study conducted by Kotek et al. (2023), LLMs have been shown to exhibit biased assumptions regarding gender roles, particularly in relation to societal perceptions of occupational gender roles. These biases were found to diverge from statistically grounded data provided by the US Bureau of Labor. Furthermore, research by Singh and Ramakrishnan (2024) revealed that LLMs openly discriminate based on gender when ranking individuals. Moreover, Huang et al. (2021) exposed implicit gender biases associated with the portrayal of protagonists in stories generated by GPT-2. These findings indicated that female characters were predominantly characterized based on physical attributes, while their male counterparts were primarily depicted with emphasis on intellectual qualities. Similarly, a study (Lucy and Bamman 2021) discovered analogous gender biases in narratives generated by GPT-3. Additionally, Kaneko et al. (2024) concluded that even in relatively straightforward tasks such as word counting, LLMs can exhibit gender bias.

Several previous research efforts have been dedicated to evaluating and comparing various LLMs with regard to their gender bias. These comparative studies have provided insights into the disparities in how LLMs handle gender-related content. For instance, Wan et al. (2023) compared the performance of ChatGPT and Alpaca and highlighted significant gender biases in the recommendation letters generated by these LLMs. More specifically, the authors observed that LLMs tend to craft letters for women that predominantly emphasize personal qualities, while letters for men tend to focus more on their achievements. In a similar vein, Zhou and Sanfilippo (2023) conducted a comparative analysis between ChatGPT, a US-based LLM and Ernie, a Chinese-based LLM. They reported that individuals using these LLMs had observed gender bias in their responses and their scientific findings confirmed the presence of gender bias in LLM-generated content. Notably, they observed differences between the two LLMs: ChatGPT tended to exhibit implicit gender bias, such as associating men and women with different professional titles while Ernie displayed explicit gender bias by overly promoting women’s prioritization of marriage over career pursuits. Furthermore, Fang et al. (2023) conducted a comparative examination of different LLMs, revealing that the AI-generated content (AIGC) produced by each LLM exhibited substantial gender and racial biases. Their study also highlighted notable discrimination against females and individuals of the Black race within the AIGC generated by these LLMs.

Numerous previous studies have examined the underlying causes of gender bias in LLMs. Researchers have investigated the training data, algorithms and fine-tuning processes to identify the origins of biased language generation. Gross (2023) concluded that biases are present because the data used to train LLMs is biased. For instance, LLMs may associate certain occupations with specific genders, such as associating “doctor” with males and “nurse” with females. On the other hand, Dong et al. (2023) suggested that LLMs may exhibit implicit biases towards certain genders even when they are not explicitly trained on biased data. This is because LLMs are trained on large datasets that reflect societal biases and stereotypes. These biases become ingrained in the model through patterns in the data, such as gendered language associations and contextual biases. Zhou and Sanfilippo (2023) found that ChatGPT was more frequently found to carry implicit gender bias whereas explicit gender bias was found in Ernie’s responses. Based on these findings, the researchers reflected on the impact of culture on gender bias and proposed governance recommendations to regulate gender bias in LLMs. Furthermore, Ferrara (2023) argued that eliminating bias from LLMs is a challenging task since the models learn from text data sourced from the Internet, which contains biases deeply rooted in human language and culture. Indeed, AI’s gender bias is a widespread concern influenced by various factors, including insufficient diversity in data and developers, biases among programmers and societal gender prejudices (Nadeem et al. 2020). The overrepresentation of men in AI design has the potential to perpetuate gender stereotypes, highlighting the importance of incorporating diversity and gender theory into machine learning (Leavy, 2018).

Beyond merely identifying the existence and causes of gender bias, previous research had also aimed to summarize the impacts of such bias within content generated by LLMs. This encompasses exploring how biased language affects users, reinforces stereotypes and influences societal perceptions. Singh and Ramakrishnan (2024) summarized gender-related disadvantages in areas such as hiring, lending and education. Paul et al. (2023) expressed concerns regarding various types of biases, including gender bias, racial bias and cultural bias that may be present in responses generated by ChatGPT in consumer-facing applications. Pavlik (2023) concluded that what exacerbates the situation is the lack of accountability concerning content generated by LLMs.

To conclude, previous research has examined gender biases in LLMs, primarily focusing on general gender contexts. However, these studies should not be directly applicable to the specific context of the accounting profession, as highlighted by the specific domain-related elements within this field. The accounting sector is distinguished by its specialized terminology and job titles such as “accountant,” “auditor,” and “controller,” which carry distinct meanings and implications not found in other professions (Ott 2022; Sung et al. 2019). Additionally, the terminology within the accounting profession is constantly evolving (Edwards and Walker 2007; Evans 2010), further distinguishing it from other fields. Directly applying findings from broader LLM gender bias studies to the accounting profession without careful validation may result in inaccurate conclusions, a concern also noted in previous literature (Calderon et al. 2024; Ling et al. 2024; Yao et al. 2023; Zhang et al. 2023). To bridge this gap, our research aims to specifically investigate how LLMs perpetuate gender stereotypes within the accounting profession. While our study focuses on the accounting profession, it is important to note that we do not suggest that this field is the most representative for examining gender stereotypes. However, our research can serve as a valuable reference for future studies in other industries, which may expand upon our findings and reveal different dynamics.

Research design: “Toy Choice” approach

In order to investigate whether AI perpetuates stereotypes within the accounting profession, and if so, in what manner. A “Toy Choice” approach was adopted in this study.

The “Toy Choice” experiment approach has been used in various studies to explore different aspects of children’s behaviour and development. DeLucia (1963) utilized this approach to measure sex-role identification in children. Kurdi (2017) extended this approach to investigate the factors influencing parent toy purchase decisions, identifying six main determinants. Gavrilova et al. (2023) applied the approach to examine the toy preferences of children. In brief, the approach involves observing and analyzing participant’s preferences and selections when presented with a variety of items, such as toys in different types and colours. Researchers often use this experiment to gain insights into gender-based preferences in toy selection and to explore how societal influences may shape these choices.

In this study, we provide a list of accounting job titles to LLMs and let the models to assign gender-related labels to each job title. The selected LLMs and job titles are discussed below.

The selected LLMs

Three LLMs were selected from Hugging Face’s official website (https://huggingface.co) for experiment purpose. Hugging Face is an online community and a key player in the democratization of AI, providing open-source tools that empower anyone to create, train and deploy AI models using open-source code. Various research had been conducted involving the platform. For example, Shen et al. (2023) introduced HuggingGPT, a framework which uses LLMs to connect different AI models and solve complex tasks while Ait et al. (2023) developed HFCommunity, a tool for analyzing the Hugging Face Hub community, which is a popular platform for sharing ML-related projects.

The three selected LLMs from Hugging Face are “facebook/bart-large-mnli” model, “MoritzLaurer/DeBERTa-v3-base-mnli-fever-anli” model and “alexandrainst/scandi-nli-large” model. For simplicity, we refer them as “Model F”, “Model M” and “Model A”, respectively. These models have been used in various research and practical applications to help understand and process human language in different contexts and languages, such as (Gubelmann and Handschuh 2022; Laurer et al. 2024; Rozanova et al. 2023; Yin et al. 2019). They are also the three most downloaded models capable of conducting zero-shot classification as on 8 December 2023. Zero-shot classification is a machine learning approach which can recognize and classify text or items into different classes or categories, even it has never seen these classes or categories before. In total, “Model F” has been downloaded 2.63 million times, “Model M” 6.29 million times and “Model A” 1.23 million times. In contrast, all other models have downloaded in <1 million times, the fourth most frequently downloaded model (NbAiLab/nb-bert-base-mnli) had only 360 thousand downloads. These figures underscore the significant popularity of the above three mentioned models, highlighting their representativeness in the field.

As explained, these three models were tasked to categorize accounting job titles.

The selected job titles

We used the job titles listed in the Association of Chartered Certified Accountants (ACCA) official website for our experiments. The association is one of the largest professional bodies in the world. According to the ACCA’s website, (https://www.accaglobal.com/gb/en/about-us.html) the association has over 252,500 members in 180 countries. In total, we obtained 53 job titles from the official ACCA website on 8 December 2023 (https://jobs.accaglobal.com/cp/role-explorer/).

The findings of the experiments are reported below.

Findings

We conducted our experiment on 8 December 2023, and then we replicated the experiment on 9 December 2023 with another computer to evaluate the consistency of our results. The two computers have different configurations—one is a notebook, and the other is a desktop. However, these configuration differences do not affect the results since both experiments were conducted on the same internet platform, Google Colab. The main distinction lies in the fact that the experiments were carried out on different days. Therefore, specific details regarding the configurations of the two computers are not provided here. Furthermore, in the follow-up experiment (on 9 December 2023), we reordered the labels. This reordering approach aims to provide an additional mechanism to evaluate if the order of labels would affect the results.

We used the 53 job titles from the official ACCA website (https://jobs.accaglobal.com/cp/role-explorer/) and we fed these 53 job titles to each of the three identified LLMs and then we let each of the LLMs to classify each of the job title to a corresponding label (female, male, other and unknown). In addition to “female” and “male”, the category “other” includes non-binary or gender non-conforming identities. The category “unknown” is used when gender information is unavailable or not specified. These categories aim to provide inclusive classification options while acknowledging diverse gender identities and circumstances where gender information may be incomplete or not disclosed.

In the following, we refer to the three LLMs used in our experiment as “Model 1,” “Model 2,” and “Model 3” instead of their real names. This choice is made to maintain anonymity and prevent potential biases associated with specific model brands. It emphasizes that our findings are not model-dependent and can be applicable to a broader category of LLMs.

The results obtained from each model were recorded, indicating the number of job titles classified into each gender category. These counts were organized into a contingency table with rows representing the categories (female, male, other and unknown) and columns representing the models (Model 1, Model 2 and Model 3).

In both the first experiment and follow-up experiment, we obtain the same results, therefore, we conclude the results were consistent and the order of labels did not affect the results.

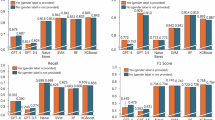

Table 1 shows the summary of the distribution of title classification among LLMs.

As per Table 1, the obtained classification results reveal distinct patterns among three language models (LLMs) tasked with labelling 53 job titles as female, male, other or unknown. Notably, Model 1 demonstrates an inclination towards assigning job titles to the male category with a predominant count of 36 instances while only 16 instances were classified as female. This skew towards male assignments suggests a potential bias or influence within the training data or model architecture that consistently associates certain terms or expressions with male gender.

Conversely, Model 2 exhibits a marked deviation in the opposite direction, displaying a significant predilection for labelling job titles as female. With 43 instances classified as female and only 10 as male. Model 2 reveals a notable imbalance in its gender assignments. This distinct bias towards female classifications may be indicative of inherent biases within the training data or the model’s architecture, which may disproportionately associate certain terms with female gender labels.

Model 3, in comparison, showcases a more balanced distribution between female and male categories, with 22 instances each. However, it introduces a nuanced element by allocating a non-negligible portion (nine instances) to the “other” category. The presence of the “other” category in Model 3 indicates that this model is more inclined to assign job titles to a gender-neutral or ambiguous classification. This nuanced approach may be attributed to a more complex understanding of job titles, potentially reflecting the model’s capacity to recognize and account for titles that do not conform to binary gender norms.

In order to assess whether there is a significant difference among three classification models concerning their results in classifying items into four categories: female, male, other and unknown, the Chi-squared test for independence was employed in this experiment.

For the Chi-squared test, expected counts were computed for each cell in the contingency table. Each cell in the contingency table represents a specific combination of a category and a model. For example, the cell at the intersection of “Model 1” and “Female” represents the observed count of items classified as female by Model 1.

The formula for calculating the expected frequency of a cell in a contingency table is:

where:

Eij = is the expected frequency for the cell in the ith row and jth column.

Rj = is the sum of the observed frequencies in the ith row.

Cj = is the sum of the observed frequencies in the jth column.

N = is the total sample size, which is the sum of all observed frequencies in the contingency table.

To implement the Chi-squared test for independence, Python was utilized within a Google Colab environment. The SciPy library was employed due to its comprehensive statistical functionalities. SciPy was chosen for its reliability and widespread use in scientific computing and statistical analysis. The applications of SciPy have widely been reported in the studies of various fields, such as finance (Vuppalapati et al. 2021), public health (Hu et al. 2021), economic education (Kuroki, 2021), marketing (Singh 2023), etc. Specifically, the “chi2_contingency” function from SciPy’s “stats” module was used in this study to compute the Chi-squared statistic, p value, degrees of freedom and expected counts.

Data preparation was conducted on the dataset in line with established statistical practices. More specifically, we opted to remove the “unknown” category from our analysis of classification results among three distinct models, and we believe this decision is well-founded for several compelling reasons. First, the “unknown” category exhibited zero counts across all models, rendering it devoid of any meaningful information. In statistical analyses, the presence of zero frequencies within a cell of a contingency table can lead to challenges in the interpretation of results and can even compromise the validity of the Chi-square test for independence. Second, our choice to eliminate the “unknown” category serves to simplify the analysis by reducing the degrees of freedom, as advised in the context of this statistical test. Including a category with no variation across models would artificially inflate the degrees of freedom, potentially leading to an overestimation of the significance of results. Therefore, by excluding the “unknown” category, we shift our analytical focus to the relevant classifications of items into “female,” “male,” and “other,” allowing for a more robust assessment of the models’ performance in these specific categories. This approach ensures that our statistical analysis is conducted with greater precision and accuracy, yielding insights that are genuinely indicative of the models’ performance on meaningful classifications.

As per Table 2, the results of the Chi-squared test indicated a significant difference in the distributions of gender classifications among the three models (p < 0.01). Cramer’s V effect size measure (0.3055) suggests a moderate to strong association between the classification models and the assigned categories. This finding underscores the significance of the choice of model in influencing classification outcomes.

Cross-model consistency in gender classifications

Despite the significant differences in gender distributions among the three models, a noteworthy observation emerges from the analysis of specific job titles. Ten out of the 53 job titles were consistently classified into the same gender category by all three models. The identified patterns are delineated into two distinct groups:

Female Group 1: Financial Analyst, Finance Analyst, Internal Audit Manager, Audit Manager, Assistant Management Accountant, Assistant Accountant.

Male Group 2: Financial Accountant, Head of Finance, Chief Financial Officer, Senior Internal Auditor.

In comparing the two identified groups of job title classifications—Female Group 1 and Male Group 2, distinct patterns and implications emerge.

For Group 1, it primarily consists of roles related to financial analysis, internal audit and assistant-level positions. The group involves tasks such as financial analysis, audit management and support functions.

For Group 2, it comprises higher level finance positions with more strategic and leadership responsibilities. The group includes roles such as financial accounting, departmental leadership (Head of Finance) and top executive leadership (CFO). These roles likely involve more strategic planning, decision-making and overall financial management for the organization.

In comparison, Group 1 (female) seems to represent roles that are more entry to mid-level, more operational and specialized, whereas Group 2 (male) includes higher level roles with greater responsibilities for financial strategy and leadership within an organization.

Furthermore, an extended analysis of the job titles includes a summary of the salary ranges for each category presented in Table 3. By examining the classification results, it becomes evident that certain job titles consistently classified as male (Group 2) by all three LLMs are characterized by higher salary ranges. The minimum, maximum and average salaries for Group 2 (male) markedly surpass those of Group 1 (female), with the average salary in Group 2 being 1.74 times higher than in Group 1. All job roles in Group 1 (females) have lower salary than job roles in Group 2 (male) except the Audit Manager role. These salary differentials align with and echo the seniority differences previously identified between the two classified groups.

An independent samples t-test was carried out to investigate if there was a significant difference in average salaries between two distinct groups using Python’s “scipy.stats” package. Group 1, consisting of six samples, had an average salary of £46,458.33, whereas Group 2, which included four samples, had an average salary of £80,812.5. The results yielded a t-statistic of −1.056 × 1016 and an extremely low p value of ~1.45 × 10−79. Given a significance level of 0.05, the null hypothesis was rejected, indicating a significant disparity in average salaries, reflecting salary differences between male and female finance professionals.

To conclude the findings above, the variation in classification results reveals the different understanding of matching job titles to gender across LLMs. In this regard, the composition of the trained dataset plays a pivotal role in this variation, as it can perpetuate historical gender imbalances associated with specific job roles, impacting the language models’ predictions. Additionally, the impact of country-specific differences is significant, with gender representation in the workforce varying widely between countries and regions as per Del Baldo et al. (2019). For example, a report (AFECA and FEE 2017) shows the landscape of female representation in the European accountancy profession paints a diverse picture across 24 nations, from 15% in Switzerland to 78% in Romania.

The findings echo the previous studies about gender pay gap in accounting sector. Previous study documented that in Japan, only 5% of women, compared to 18% of men, were senior managers. At the highest levels of management, there were no female partners (Stedham et al. 2006). The UK figure indicated that the overall median pay gap is higher than the national figure—far more men than women are employed in senior positions within accountancy firms, although there is no such imbalance at the more junior levels (ICAEW Insights 2021). Male accounting partners earn $110,000 more than their female counterparts, according to a remuneration survey of chartered accountants (Bennett 2022). The survey conducted by Twum (2013) found that none of the sample selected was in the top hierarchy of their respective jobs in Ghana. Deery (2022) reported that with women only holding 32.5% of management positions in Australian accounting firms. In USA, women hold 43% of the partnership positions at firms employing 2–10 CPAs, and 39% at firms with 11–20 CPAs (Drew 2015). The study conducted by Vidwans and Cohen (2020) with a focus on Big Four firms and in academia in New Zealand revealed that there is a gender pay gap in the accounting profession, with female accountants earning 71% of what their male counterparts earn and women are underrepresented in the highest levels of the accounting profession, making up only 22% of partners in Certified Public Accounting firms.

It is worth mentioning that previous studies have recommended adjusting for potential influencing factors when applying LLMs. For instance, (Gorodnichenko et al. 2023) noted that although pre-trained BERT models can interpret texts as positive or negative, researchers should include additional steps to account for these influencing factors. In this regard, a practical approach is to incorporate intermediate layers to enhance the accuracy of classification outcomes.

In our study, factors such as salary and status can be considered as potential influences on the classification of genders assigned to job titles within the accounting profession. However, after thorough consideration, we opted not to employ the strategy of adding intermediate layers in our experiments. The primary reason for this decision was that the models used in our research were advanced zero-shot classification LLMs, unlike BERT which does not belong to this category (Wang et al. 2022). Zero-shot classification in LLMs refers to the model’s ability to categorize text into predefined categories without any prior examples or training specific to those categories (Gera et al. 2022; Puri and Catanzaro 2019). According to previous studies (Halder et al. 2020; Wang et al. 2023) zero-shot classification models can be effectively utilized directly without the need for intermediate layers. These models possess sophisticated attention mechanisms and deep layers that adeptly capture complex data patterns (He et al. 2021; Lewis et al. 2019). Conversely, the introduction of additional layers might lead to overfitting, causing the model to become overly specialized to the training data and diminishing its generalization capabilities (Gera et al. 2022; Wang et al. 2023). In brief, our decision not to integrate intermediate layers was informed by the capabilities and inherent characteristics of zero-shot classification models, which align closely with our research context. Future research could explore model architectures, including additional intermediate layers to investigate how LLMs perpetuate gender stereotypes.

Discussion

In summary, our experiments present three key findings. First, we observed marked differences in how the three selected language models approach gender labelling in accounting job titles: one model shows a preference for male labels, another for female and the third demonstrated a balanced approach incorporating gender-neutral options. Second, the Chi-squared test results point to a significant disparity in these labelling patterns. Finally, our analysis reveals that job titles consistently classified as male by all models are associated with higher salary ranges, indicating a potential bias in gender-related economic outcomes.

We argue that the labelling patterns observed in our experiment are inherently interconnected with the datasets utilized during the training of LLMs. The datasets employed for LLM training are drawn from a wide array of public sources, such as books and social media content, effectively encapsulating the language, attitudes and prevailing social norms of the era in which they were compiled. Consequently, our study not only reaffirms the presence of gender stereotypes within LLMs as previously documented in the existing literature but also uncovers gender stereotypes embedded within these models within the specific context of the accounting profession. Furthermore, this study sheds lights on the transition of gender stereotypes from the physical world to the digital realm through LLMs.

This argument underscores the significant impact of cultural and social factors on language models. LLMs, being exposed to vast amounts of text from the internet tend to reflect the linguistic patterns and implicit biases inherent in the data. The differences in gender label distribution among LLMs likely echo societal and cultural stereotypes within accounting profession, raising questions about the role these models play in perpetuating or amplifying such biases.

Furthermore, our concern goes beyond the mere presence of gender stereotypes in LLMs within the accounting occupation context. It encompasses a broader concern regarding the potential ramifications of these stereotypes related to occupations in LLMs, extending from the accounting sector to various other sectors.

More specifically, the broader concern is particularly relevant in areas like hiring and recruitment, where LLMs could play a significant role. Our research has revealed that various LLMs exhibit distinct gender biases. For example, one LLM shows a preference for male candidates, another for females, while a third displays a more balanced approach. Furthermore, a previous study (An et al. 2024), which analyzed a different LLM (GPT), also found that the LLM tends to favour female candidates. This variability among LLMs, combined with their complex and sometimes unpredictable behaviour, could lead to unexpected outcomes in practical applications.

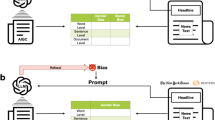

Of course, it can be argued that many LLM-based AI systems, such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT, have attempted to reduce gender bias through various measures. However, the stereotypes embedded in LLMs are difficult to eliminate completely. In this regard, we would like to share two conversations between ChatGPT and us as illustrative examples.

Conversations with ChatGPT

On 1:10 p.m., 15 December 2023, as per Fig. 1, we asked ChatGPT a question: “John and Mary are working together on a project. Please guess who is the accountant and who is the engineer.”

In the conversation, ChatGPT initially provided a neutral answer and explained that it cannot accurately determine which one of them. However, when we follow-up to request ChatGPT to make a guess as per Fig. 2, ChatGPT suggested that John is the engineer, and Mary is the accountant—although a disclaimer provided to state it is just a random guess.

It could be because of random guess, or it could be because of the order of the names we provided. We therefore asked the same question, on 1:17 p.m., 15 December 2023, but changed the order of John and Mary as below.

In the third conversation (Fig. 3), same as before, ChatGPT initially provided a neutral answer and explained that it cannot accurately determine which one of them. However, when we followed up to request ChatGPT to make a guess (Fig. 4). Again, ChatGPT suggested that John is the engineer, and Mary is the accountant, the answer further provide some interesting hints stating this is a common stereotype.

In both conversations, ChatGPT initially provided a neutral response, explaining that it cannot accurately determine between the two options. However, it then proceeded to provide answers that aligned with common stereotypes. These conversations serve as examples demonstrating how stereotypes are ingrained in ChatGPT through its language model. However, it is only an example. We do not know how depth and what extend this stereotype would affect AI-powered solutions through LLMs.

In fact, as LLMs continue to gain prominence in the realm of AI, there is a concern that these models might perpetuate and reinforce gender stereotypes ingrained in their training data. If LLMs consistently associate certain genders with specific roles or traits, they can inadvertently bolster societal prejudices. This has direct implications for education, career choices and opportunities, potentially hindering progress towards the achievement of gender equality.

Moreover, as AI-driven decision-making systems powered by LLMs become increasingly integral to sectors such as finance, management, human resources and criminal justice, the biases inherent in these models can lead to systemic discrimination. Biased AI algorithms can result in unfair lending practices, biased recruitment and promotion, discriminatory sentencing and more. Thus, amplifying existing societal inequalities.

The situation could be further deteriorated when introducing “data augmentation” or “synthetic data generation.” These two terms refer to using AIGC to train AI and this is a common practice in various fields. In fact, using AIGC to train AI models can exacerbate the bandwagon effect on gender bias in several ways.

Given AI models are often trained on large datasets that reflect existing societal biases including gender stereotypes, when AIGC is used as training data, it can inadvertently reinforce these stereotypes. For example, if AI-generated text or images exhibit gender stereotypes or discriminatory language, the AI model may learn and perpetuate these stereotypes, leading to a bandwagon effect where the AI reinforces and amplifies the existing gender stereotypes found in society. In fact, the bandwagon effect can occur when organizations blindly follow the trend of using AIGC without critically evaluating the quality and ethics of the data. When companies and developers use AIGC to train their AI models because it is a common practice, they may not pay sufficient attention to the potential biases within the data. This can lead to a cascading effect, where more and more AI systems adopt and amplify the same gender biases, exacerbating the problem.

The potential solutions and further concern

Undoubtedly, there is a pressing need to eradicate occupational gender bias and stereotypes. In literature and in practice, a range of efforts have been made to address gender bias in AI. Nadeem et al. (2022) proposed a theoretical framework that incorporating technological, organizational and societal approaches to address this issue. Feldman and Peake (2021) provide a comprehensive review of gender bias in machine learning applications, discussing various bias mitigation algorithms and proposing an end-to-end bias mitigation framework.

However, these approaches often involve using human judgement to correct or to eliminate the stereotype. However, human judgement itself can be subjective and biased. Evaluators or annotators may have their own unconscious biases that could affect their assessments and interventions. This can lead to inconsistencies and subjectivity in identifying and mitigating bias. In some cases, human intervention may unintentionally amplify bias rather than mitigating it—if human annotators are asked to manually adjust predictions to achieve “fairness”, they may inadvertently reinforce stereotypes or introduce new biases. As per Sun et al. (2020), bias in the dataset can lead to an increase in inequality in a model’s predictions.

Public awareness as a better solution

Therefore, we argue that establishing a more robust public awareness is a better choice than using human judgement as intervention to mitigate gender stereotypes.

From the standpoint of mitigating gender stereotypes, one may analogize public awareness to our biological immune system. Just as public awareness shields us from harmful pathogens, an informed and vigilant populace can assume a pivotal role in recognizing and rectifying biases within these intricate systems.

In fact, increased public awareness leads to greater scrutiny and accountability and it can also foster a culture of responsibility. Moreover, when people are more knowledgeable about the issue, they are better equipped to have meaningful conversations about gender bias in LLMs. These discussions can lead to a deeper understanding of the complexities of LLMs and how LLMs intersect with social issues like gender bias. Furthermore, a well-informed public can contribute valuable insights and perspectives that enhance the diversity of training data. Diverse input is crucial for the development of more balanced and equitable models. By engaging a broader cross-section of society in the development and training of language models, LLMs can better represent and serve the needs of all users, regardless of gender.

It is worth to mention that achieving diversity is not easy because of the public exclusion issue. We emphasize that LLMs represent the collective voice of a specific group of individuals contributing to the vast real-world text data. However, it is essential to acknowledge the presence of minority groups and individuals whose voices remain unheard or inaccessible, including those who lack of internet access, are non-English speakers in a predominantly English-dominated internet ecosystem and people who struggle to articulate their thoughts effectively. Additionally, the fear of social isolation and cyberbullying, coupled with emotional factors like fear and anger can deter certain people from participating in online conversations. This dynamic can lead to a situation where a select few dominate discussions on social media while others hesitate to voice their opinions, ultimately diminishing the diversity of perspectives and discourse on gender-related and many other issues.

Conclusion

In recent years, the integration of LLMs into various applications has significantly impacted the field of AI. These models, with their immense linguistic capabilities, have found applications in diverse sectors, including the accounting industry. By addressing the research question: “does AI perpetuates stereotypes within the accounting profession, and if so, in what manner”, this research sheds light on the gender bias present in LLMs, specifically in their classification of job titles within the accounting domain.

Stereotypes, if present, can contribute to reinforcing existing gender bias, affecting hiring decisions, career progression and overall workplace dynamics. Identifying and understanding these stereotypes is essential for fostering a fair and inclusive working environment, especially as organizations increasingly rely on AI systems for hiring and decision-making processes.

Although previous research has extensively documented different aspects of gender biases in LLMs, most of relevant studies focus on studying gender context. Their findings cannot fully apply to the specific accounting field. The key contributions of our study lie in its empirical investigation of how LLMs handle gender labelling, the statistical validation of observed patterns and the implications of these patterns on economic outcomes.

In brief, our research reveals two significant insights. First, language models (LLMs) exhibit biases in assigning gender to accounting job titles, reflecting underlying biases in their training data. This phenomenon underscores how AI can perpetuate stereotypes by reinforcing traditional gender associations in professional roles. Secondly, these gendered labels are linked to salary discrepancies, highlighting a broader issue of gender bias affecting career opportunities within accounting. These insights reaffirm the existing literature on gender stereotypes in AI while uncovering specific biases within the accounting context.

Given these findings, our study provides valuable contributions for educators, policymakers and industry leaders. For educators, it highlights the need to incorporate discussions on AI and gender biases within accounting curricula, fostering critical awareness among future professionals. Policymakers can use these insights to develop regulations ensuring unbiased AI deployment, promoting fairness and equality in the workplace. For industry leaders, the study underscores the importance of implementing transparent AI practices and proactive measures to mitigate bias, fostering an inclusive corporate culture.

The findings of this research hold multifaceted implications for both the AI and accounting communities. First and foremost, the identification and elucidation of gender stereotypes in LLMs contribute to ongoing discussions surrounding the ethical development and deployment of AI technologies. The accounting industry, being a critical player in global economic ecosystems can benefit from a more nuanced understanding of the potential stereotypes that might inadvertently be ingrained in the systems it adopts.

Furthermore, this research contributes to the broader conversation on diversity and inclusion within the workplace. By scrutinizing the gender classifications made by LLMs, the study highlighted areas where bias might emerge and subsequently influence professional dynamics. The implications extend beyond the immediate context of job title classifications, reaching into broader considerations of workplace culture, employee satisfaction and societal expectations.

Moreover, the study can serve as a foundational exploration into the potential biases of widely used LLMs, offering insights that can inform future research and guide the development of more ethical and unbiased AI applications within the accounting domain.

Data availability

The data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

AFECA, FEE (2017) Gender diversity in the European accountancy profession. An AFECA study with the support of FEE. https://accountancyeurope.eu/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Afeca_Gender-Diversity-in-the-European-Accountancy-Profession.pdf. Accessed 7 Feb 2024

Ait A, Izquierdo JLC, Cabot J (2023) HFCommunity: a tool to analyze the Hugging Face Hub community. In: 2023 IEEE international conference on software analysis, evolution and reengineering (SANER), pp 728–732

Alev K, Gonca G, Ece EA, Yasemin ZK (2010) Gender stereotyping in the accounting profession in Turkey. J Mod Account Audit 6(4):15–25

An J, Huang D, Lin C, Tai M (2024) Measuring gender and racial biases in large language models. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2403.15281

Arceo-Gomez EO, Campos-Vazquez RM, Badillo RY, Lopez-Araiza S (2022) Gender stereotypes in job advertisements: what do they imply for the gender salary gap? J Labor Res 43:65–102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12122-022-09331-4

Bennett T (2022) Gender pay gap gets worse as accountants rise to partner. In: Chartered Accountants Worldwide. https://charteredaccountantsworldwide.com/gender-pay-gap-gets-worse-accountants-rise-partner/. Accessed 18 Dec 2023

Calderon N, Porat N, Ben-David E, Chapanin A, Gekhman Z, Oved N, Shalumov V, Reichart R (2024) Measuring the robustness of NLP models to domain shifts. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2306.00168

Clarke HM (2020) Gender stereotypes and gender-typed work. In: Zimmermann KF (ed) Handbook of labor, human resources and population economics. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp 1–23

Deery F (2022) Why accounting adds up for women. https://www.accountantsdaily.com.au/business/17051-why-accounting-adds-up-for-women. Accessed 18 Dec 2023

Del Baldo M, Tiron-Tudor A, Faragalla WA (2019) Women’s role in the accounting profession: a comparative study between Italy and Romania. Adm Sci 9:2. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci9010002

DeLucia LA (1963) The toy preference test: a measure of sex-role identification. Child Dev 34:107–117. https://doi.org/10.2307/1126831

Dong X, Wang Y, Yu PS, Caverlee J (2023) Probing explicit and implicit gender bias through LLM conditional text generation. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2309.09825

Drew J (2015) Women see far more partnership gains with small firms than with large ones. J Account https://www.journalofaccountancy.com/news/2015/nov/cpa-partnership-gains-for-women-201513396.html. Accessed 18 Dec 2023

Edwards JR, Walker SP (2007) Accountants in late 19th century Britain: a spatial, demographic and occupational profile. Account Bus Res 37(1):63–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/00014788.2007.9730060

Evans L (2010) Observations on the changing language of accounting. Account Hist 15(4):439–462. https://doi.org/10.1177/1032373210373619

Fang X, Che S, Mao M, et al. (2023) Bias of AI-generated content: an examination of news produced by large language models. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2309.09825

Feldman T, Peake A (2021) End-to-end bias mitigation: removing gender bias in deep learning. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2104.02532

Ferrara E (2023) Should ChatGPT be biased? Challenges and risks of bias in large language models. First Monday. https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v28i11.13346

Gavrilova MN, Sukhikh VL, Veresov NN (2023) Toy preferences among 3-to-4-year-old children: the impact of socio-demographic factors and developmental characteristics. Psychol Russ 16:72–84. https://doi.org/10.11621/pir.2023.0206

Gera A, Halfon A, Shnarch E, Perlitz Y, Ein-Dor L, Slonim N (2022) Zero-shot text classification with self-training. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2210.17541

Gorodnichenko Y, Pham T, Talavera O (2023) The voice of Monetary Policy. Am Econ Rev 113(2):548–584. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20220129

Gross N (2023) What ChatGPT tells us about gender: a cautionary tale about performativity and gender biases in AI. Soc Sci 12:435. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12080435

Gubelmann R, Handschuh S (2022) Uncovering more shallow heuristics: probing the natural language inference capacities of transformer-based pre-trained language models using syllogistic patterns. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2201.07614

Halder K, Akbik A, Krapac J, Vollgraf R (2020) Task-aware representation of sentences for generic text classification. In Scott D, Bel N, Zong C (eds) Proceedings of the 28th international conference on computational linguistics. International Committee on Computational Linguistics. pp 3202–3213. https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/2020.coling-main.285

He P, Liu X, Gao J, Chen W (2021) DeBERTa: Decoding-enhanced BERT with disentangled attention. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2006.03654

Hu C, Hu Y, He Z, et al. (2021) Analysis of epidemic data based on SciPy. In: 2021 international conference on intelligent computing, automation and applications (ICAA). pp 510–513

Huang T, Brahman F, Shwartz V, Chaturvedi S (2021) Uncovering implicit gender bias in narratives through commonsense inference. arXiv. http://arxiv.org/abs/2109.06437

ICAEW Insights (2021) Gender Pay Gap and the accountancy profession: time for a rethink? https://www.icaew.com/insights/viewpoints-on-the-news/2021/oct-2021/gender-pay-gap-and-the-accountancy-profession-time-for-a-rethink. Accessed 18 Dec 2023

Kabalski P (2022) Gender accounting stereotypes in the highly feminised accounting profession. The case of Poland. Zesz Teoretyczne Rachun 46(1):157–184. https://doi.org/10.5604/01.3001.0015.7993

Kaneko M, Bollegala D, Okazaki N, Baldwin T (2024) Evaluating gender bias in large language models via chain-of-thought prompting. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2401.15585

Kotek H, Dockum R, Sun D (2023) Gender bias and stereotypes in large language models. In: Proceedings of the ACM collective intelligence conference. Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, pp 12–24

Kurdi BA (2017) Investigating the factors influencing parent toy purchase decisions: reasoning and consequences. Int Bus Res 10:104. https://doi.org/10.5539/ibr.v10n4p104

Kuroki M (2021) Using Python and Google Colab to teach undergraduate microeconomic theory. Int Rev Econ Educ 38:100225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iree.2021.100225

Laurer M, Atteveldt W, van, Casas A, Welbers K (2024) Less annotating, more classifying: addressing the data scarcity issue of supervised machine learning with deep transfer learning and BERT-NLI. Polit Anal 32:84–100. https://doi.org/10.1017/pan.2023.20

Leavy S (2018) Gender bias in artificial intelligence: the need for diversity and gender theory in machine learning. In: Proceedings of the 1st international workshop on gender equality in software engineering. Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, pp 14–16

Lewis M, Liu Y, Goyal N, Ghazvininejad M, Mohamed A, Levy O, Stoyanov V, Zettlemoyer L (2019) BART: denoising sequence-to-sequence pre-training for natural language generation, translation, and comprehension. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1910.13461

Ling C, Zhao X, Lu J, Deng C, Zheng C, Wang J, Chowdhury T, Li Y, Cui H, Zhang X, Zhao T, Panalkar A, Mehta D, Pasquali S, Cheng W, Wang H, Liu Y, Chen Z, Chen H, … Zhao L (2024) Domain specialization as the key to make large language models disruptive: a comprehensive survey. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2305.18703

Lucy L, Bamman D (2021) Gender and representation bias in GPT-3 generated stories. In: Akoury N, Brahman F, Chaturvedi S, et al. (eds) Proceedings of the third workshop on narrative understanding. Association for Computational Linguistics, Virtual, pp 48–55

Nabil B, Srouji A, Abu Zer A (2022) Gender stereotyping in accounting education, why few female students choose accounting. J Educ Bus 97:542–554. https://doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2021.2005512

Nadeem A, Abedin B, Marjanovic O (2020) Gender bias in AI: a review of contributing factors and mitigating strategies. ACIS 2020 Proceedings https://aisel.aisnet.org/acis2020/27

Nadeem A, Marjanovic O, Abedin B (2022) Gender bias in AI-based decision-making systems: a systematic literature review. Australas J Inf Syst 26. https://doi.org/10.3127/ajis.v26i0.3835

Ott C (2022) The professional identity of accountants – an empirical analysis of job advertisements. Account Audit Account J 36(3):965–1001. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-08-2021-5389

Paul J, Ueno A, Dennis C (2023) ChatGPT and consumers: benefits, pitfalls and future research agenda. Int J Consum Stud 47:1213–1225. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12928

Pavlik JV (2023) Collaborating with ChatGPT: considering the implications of generative artificial intelligence for journalism and media education. J Mass Commun Educ 78:84–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/10776958221149577

Puri R, Catanzaro B (2019) Zero-shot text classification with generative language models. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1912.10165

Rozanova J, Valentino M, Freitas A (2023) Estimating the causal effects of natural logic features in neural NLI models. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2305.08572

Shen Y, Song K, Tan X, et al. (2023) HuggingGPT: solving AI tasks with ChatGPT and its friends in hugging face. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2303.17580

Shinar EH (1975) Sexual stereotypes of occupations. J Vocat Behav 7:99–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/0001-8791(75)90037-8

Singh AK (2023) Applications of the Internet of Things and machine learning using Python in digital marketing. In: Global applications of the Internet of Things in digital marketing. IGI Global, pp 213–232

Singh S, Ramakrishnan N (2024) Is ChatGPT biased? A review. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/9xkbu

Stedham Y, Yamamura JH, Satoh M (2006) Gender and salary: a study of accountants in Japan. Asia Pac J Hum Resour 44:46–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/1038411106061507

Sun W, Nasraoui O, Shafto P (2020) Evolution and impact of bias in human and machine learning algorithm interaction. PLoS ONE 15:e0235502. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0235502

Sung A, Leong K, Sironi P, O’Reilly T, McMillan A (2019) An exploratory study of the FinTech (Financial Technology) education and retraining in UK. J Work Appl Manag 11(2):187–198. https://doi.org/10.1108/JWAM-06-2019-0020. Scopus

Tabassum N, Nayak BS (2021) Gender stereotypes and their impact on women’s career progressions from a managerial perspective. IIM Kozhikode Soc Manag Rev 10:192–208. https://doi.org/10.1177/2277975220975513

Twum E (2013) The accounting profession and the female gender in Ghana. Account Finance Res 2. https://doi.org/10.5430/afr.v2n1p54

Vidwans M, Cohen DA (2020) Women in accounting: Revolution, where art thou? Acc. Hist. 25:89–108. https://doi.org/10.1177/1032373219873686

Vuppalapati C, Ilapakurti A, Vissapragada S, et al. (2021) Application of Machine Learning and Government Finance Statistics for macroeconomic signal mining to analyze recessionary trends and score policy effectiveness. In: 2021 IEEE international conference on big data (big data). pp 3274–3283

Wan Y, Pu G, Sun J, et al. (2023) “Kelly is a Warm Person, Joseph is a Role Model”: Gender biases in LLM-generated reference letters. arVix. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2310.09219

Wang Y, Wang W, Chen Q, Huang K, Nguyen A, De S (2022) Generalised zero-shot learning for entailment-based text classification with external knowledge. In: 2022 IEEE international conference on smart computing (SMARTCOMP), pp 19–25. https://doi.org/10.1109/SMARTCOMP55677.2022.00018

Wang Z, Pang Y, Lin Y (2023) Large language models are zero-shot text classifiers. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2312.01044

White MJ, White GB (2006) Implicit and explicit occupational gender stereotypes. Sex Roles 55:259–266. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-006-9078-z

Yao J, Xu W, Lian J, Wang X, Yi X, Xie X (2023) Knowledge plugins: enhancing large language models for domain-specific recommendations. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2311.10779

Yin W, Hay J, Roth D (2019) Benchmarking zero-shot text classification: datasets, evaluation and entailment approach. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1909.00161

Zhang W, Liu H, Du Y, Zhu C, Song Y, Zhu H, Wu Z (2023) Bridging the information gap between domain-specific model and general LLM for personalized recommendation. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2311.03778

Zhou KZ, Sanfilippo MR (2023) Public perceptions of gender bias in large language models: cases of ChatGPT and ernie. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2309.09120

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the University of Chester, UK under the QR fund (Ref: QR767).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Both authors contributed equally. They were involved in every aspect of the study, including the conception and design of the experiments, data collection and analysis and manuscript preparation. Both authors had read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This research followed the ethical principles, rules and regulations of the Ethical Committee of the University of Chester, UK. Ethical approval from the university is not required as this study utilized data generated by large language models (LLMs) and did not involve human participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Leong, K., Sung, A. Gender stereotypes in artificial intelligence within the accounting profession using large language models. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 1141 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03660-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03660-8

This article is cited by

-

Gender Mainstreaming Strategy and the Artificial Intelligence Act: Public Policies for Convergence

Digital Society (2025)

-

Introducing AIRSim: An Innovative AI-Driven Feedback Generation Tool for Supporting Student Learning

Technology, Knowledge and Learning (2025)