Abstract

Does the entry of foreign-invested enterprises (FIEs) enhance host economies’ entrepreneurship? Empirical findings in the literature are far from conclusive because of diverse local conditions. This article investigates the effect of FIEs on local private business creation in China. Using a panel dataset of 31 provinces from 1992 to 2019 and two-way fixed effect models, this study finds that the entry of foreign-invested firms significantly enhances China’s provincial-level entrepreneurship. The effect is robust to various sets of control variables and different measurements of FIEs (either FDI stock or flow). The findings also suggest that the effect of FIEs on local entrepreneurship is lower in the second subperiod (2001–2019) than in the first subperiod (1992–2001). Moreover, the improved legal status of private businesses and better protection of private property, as amended in the Constitution, decrease the role of FIEs in enhancing local entrepreneurship.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Does the entry of foreign-invested enterprises (FIEs)Footnote 1 enhance host economies’ entrepreneurship? Answering this question has both theoretical significance and policy relevance. Many studies in the literature have identified the positive role of foreign direct investment (FDI) and entrepreneurship in improving standards of living (Luo and Yan, 2002; Yao and Wei, 2007; Zhao, 2013; Zhao, 2018). However, relatively few studies have investigated the role of FIEs in local entrepreneurship development. Policymakers in many developing countries and transition economies have recognized the importance of FDI and entrepreneurship in enhancing economic growth. However, they lack a deeper understanding of the interactions between FIEs and local private businesses (Lin, 2022).

The re-emergence of entrepreneurship in China occurred after China initiated its economic transformation in the late 1970s. The first private business license was approved in 1979 in Wenzhou City of East China’s Zhejiang Province. Forty years later, private businesses contributed to more than 60% of the country’s GDP. China started attracting FDI in the late 1970s, and the country has been the largest FDI recipient in the developing world since 1992. Since both local entrepreneurship and FIEs are growing quite rapidly in China, the interaction between them in general and the impact of FIEs on local entrepreneurship in particular are intuiting questions for both scholars and policymakers.

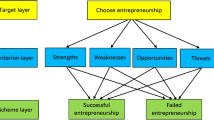

The goal of this study is to empirically identify the overall (or net) effect of FIEs on domestic entrepreneurship in Chinese provinces. This research question is empirical because FIEs may theoretically exert both a positive spillover (or demonstration) effect and a negative competing (or crowding-out) effect on local entrepreneurship. The specific channels through which FIEs may affect local entrepreneurship are presented in Section “Background and mechanisms”. The analysis in this article is intended to offer useful insights to policymakers in other developing countries who aim to improve their economic performance through both FDI and domestic entrepreneurship.

Using a panel dataset of 31 Chinese provinces from 1992 to 2019, we study the effect of FIEs on local entrepreneurship. The outcome variable in our analysis is the number of newly registered private businesses per capita. This is not a perfect measure of entrepreneurship because it does not consider the size of each firm. However, this measure focuses on the creation of new businesses and has been widely used in the literature (e.g., Jian et al. 2021). The key independent variable is the size of foreign business presence in host economies. We use the amount of accumulated FDI (depreciated annually) to measure the presence of FIEs because the impact of FIEs on local businesses is exerted by all existing FIEs, not just by the newly entered ones. Our research design is a typical two-way fixed effects (TWFE) model. Exploiting the advantage of the panel data structure and controlling for time-invariant heterogeneities would alleviate the bias of omitted variables to a great extent. Our main results withstand robustness checks.

Setting this study in the context of China has several advantages. First, there is enough variation in regional FIEs because of the large size of the country. Second, Chinese provinces are relatively homogeneous in other aspects and subject to similar economic and political shocks at the national level (Xu and Yao, 2015). This makes them better comparison groups than countries do in cross-country studies. Third, China represents the trinity of a developing economy, a transition economy, and a fast-growing economy (Zhao, 2018). Both foreign investors and local entrepreneurs play indispensable roles in economic development. Hopefully, policymakers in other developing countries can obtain insights from our analysis and initiate effective policies to strengthen the positive role of FIEs in promoting local entrepreneurship.

Our empirical analysis shows that during the sample period FIEs (measured by the accumulated stock of FDI per capita) significantly enhanced China’s regional entrepreneurship at the provincial level. This result is robust when we control for different sets of variables and use different sample periods. We interpret this result as evidence that the net (overall) effect of FIEs on Chinese local entrepreneurship is positive even though FIEs may theoretically crowd out some local entrepreneurship. For example, as documented by Lin (2022), large multinational companies bought promising Chinese private firms in the early 2000s. We also find that the effect of FIEs on local entrepreneurship is lower in the second subperiod (2001–2019) than in the first subperiod (1992–2021). This finding may suggest that the demonstration effect of FIES diminishes as the gap between foreign and domestic technology and management narrows. Moreover, the interactions between FDI and the constitutional amendment dummies are negative and statistically significant at the 1% level, which suggests that an improved legal environment more favorable to domestic entrepreneurship dwindles the role of FIEs in enhancing local entrepreneurship.

This article adds to the empirical literature concerning the impact of multinational enterprises on the local entrepreneurship of developing countries. In a case study of Macedonia, Apostolov (2017) finds that FDI has a positive influence on reinforcing the creation of new firms and is also likely to influence job seekers to become employed rather than to start their own businesses. The overall impact of foreign investment is positive in the case of Macedonia. For Nigeria, Onwuka and Chigozie (2014) also find a positive relationship between FDI and entrepreneurial development. Our present study adds the case of China to this FDI-entrepreneurship nexus literature.

This article is also associated with a study by Lu and Tao (2010). They show that the institutional environment, which includes the protection of private property and contract enforcement, is an important determinant of entrepreneurship decisions in China. The inflow of FDI promotes the reform of domestic institutions because local governments must improve their infrastructure, laws and rules to attract more FDI. A greatly improved business environment and institutions (especially a level playing field for all businesses) are conducive to local entrepreneurship development. This point is of particular importance to transition economies such as China.

The FDI-entrepreneurship nexus research is far from complete. More recent studies have shed light on the causal effect of foreign firms on local entrepreneurship. Fang et al. (2020) use a longitudinal dataset of 30 countries and hypothesize that foreign ventures may reduce necessity-driven entrepreneurship by diminishing local unemployment and may increase opportunity-driven entrepreneurship by promoting domestic knowledge stock. This dichotomy of necessity- and opportunity-driven entrepreneurship is prevalent in the literature. We argue, however, that there is sometimes no clear-cut border between them. A person would not start a business if he does not see an “opportunity,” no matter how “necessary” it is for him to do so. He would not start a business either if he does not think it “necessary” to do so, no matter how many “opportunities” he sees. Therefore, it is empirically difficult (if not impossible) to identify which new business is purely necessity-driven and which is opportunity-driven, although theoretically, they are clearly defined.

In summary, compared with recent studies in the literature on this topic, our innovations and possible contributions are as follows. First, we empirically identify a positive effect of foreign-invested firms on local entrepreneurship in the context of China, although theoretically there are various causal mechanisms with the same or opposite signs. Second, we split the entire sample period (1992–2019) into two subperiods, 1992–2001 and 2001–2019, and find that the effect of FIEs on local entrepreneurship is greater in the first subperiod than in the second subperiod. Finally, we take into account the effect of constitutional amendments on entrepreneurship and find that an improved legal environment more favorable to domestic entrepreneurship decreases the role of FIEs in promoting entrepreneurship.

The next section provides some background against which foreign-invested firms interact with local businesses in the case of China and the possible mechanisms through which FIEs affect local entrepreneurship. Section “Econometric specification” discusses the econometric specifications and descriptions of the variables. Section “Data” describes the data sources used in the analysis and presents descriptive statistics and correlation matrix. Section “Regression results” presents the results. Section “Conclusion” concludes.

Background and mechanisms

As early as July 1979, China passed the China-Foreign Equity Joint Ventures Law and began to attract FDI. Four decades later, investors from more than 180 countries and regions invested in China by the end of 2019. Data from the World Investment Report released by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD, 2021) show that China has accumulated FDI worth 2 trillion dollars since the late 1970s. In recent years foreign companies have invested in mainly high-end manufacturing and modern service industries in China. By the end of 2019, ~1 million FIEs had been operating in China. FIEs contributed more than 20% of China’s total industrial output and taxes. China was the largest FDI recipient in the developing world from 1992 to 2019 (UNCTAD, 2021).

Two features stand out regarding FIEs in China. First, FIEs in China have been operating in a stable political and legal environment since the late 1970s. This is especially true since China entered the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001. The interests of FIEs are secured by laws. Three laws regarding FIEs were promulgated by the Chinese government. The China-Foreign Equity Joint Ventures Law, Foreign-Invested Enterprises Law and China-Foreign Cooperative Joint Ventures Law were passed in 1979, 1986 and 1988, respectively. They were revised several times and in 2019 they were merged into one law, i.e., the China Foreign Investment Law of the People’s Republic of China, which took effect as of January 1, 2020. A stable political and legal environment has been one of the important reasons that China has been the largest FDI recipient in the developing world for many years.

The second prominent feature is that previous FIEs in China have exhibited a significant “demonstration effect” on new FIEs. For example, Taicang city in East China’s Jiangsu Province is called the “Hometown of German Enterprises.” As documented by Shi (2022), as early as 1993, the then-CEO of a German car-part company came to China to find a place to invest in. When he happened to find that the redwood along a river in Taicang was very similar to the black forest in his hometown, he decided to settle there and became the first German company in Taicang. Thirty years later, a total of 450 German companies came to Taicang and invested more than 5 billion dollars there. This story is typical. As German companies are concentrated in Taicang City, most Taiwan investors are concentrated in Kunshan City, Jiangsu Province, and more than 50% of the FIEs from Hong Kong are located in Guangdong Province.

Chinese domestic firms typically lagged far behind FIEs in technology, management, marketing, and brand names, especially in the 1980s and 1990s. FDI was the least costly way for China to learn from modern economies. Worker mobility is one of the most important mechanisms through which the technology and knowledge of FIEs diffuse to Chinese domestic businesses (Liu, 2019). Taking the auto industry as an example, joint ventures formed by China and foreign carmakers have trained tens of thousands of technical and management talents in China over the past three decades. Today, many Chinese automobile company founders, managers, and technicians have working experience in FIEs. For example, the CEO and founder of Cherry Auto Company (the largest Chinese car exporter today) had been working in the Chinese-German joint venture FAW-Volkswagen for several years. It is “personal contact that is most relevant in learning” to adopt new technologies and management practices (McCloskey, 2010). The development of FIEs provides this kind of “learning-by-doing” opportunity. Vertical technology spillovers occur through forward and backward linkages. Using Chinese data from 1998 to 2009, Tang et al. (2019) find that FDI exerts a significant innovation spillover effect on Chinese enterprises through backward linkages. Luo (2016) identifies a positive role of FDI in the technological innovation of domestic firms through forward linkages. In this process, vast business opportunities are created for local entrepreneurs. For example, the China-German joint venture Shanghai Volkswagen began to produce its Santana sedans in 1985. In 1987 only 2.7% of the parts were produced in China. This number increased to 70% by 1991 (Liu, 2019).

The demonstration effect of FIEs also enhances the corporate governance capabilities and management practices of domestic firms. FIEs, especially large multinational companies, already have modern corporate governance systems and practice advanced management norms. Their presence in China provides vast opportunities for local businesses to learn from watching and contacting. The demonstration effect is also embodied in innovation activities. Chen and Zhou (2023) find that a region will have more innovative entrepreneurship entry and growth if it has more FDI innovation activities. The presence of FIEs has accelerated the development of China’s market-supporting institutions and legal system. For example, the promulgation of the China Foreign Cooperative Joint Ventures Law in 1979 was the result of cooperative intentions and efforts between China and Volkswagen, Germany. The promulgations of the Trademark Law in 1982 and the Patent Law in 1984 in China were also intended to meet the demands of FIEs. It is fair to say that FIEs have played an irreplaceable role in the building of China’s market-supporting institutions, including the perfection of legal systems. This must be conducive to the development of China’s local entrepreneurship.

In the case of China, the presence of foreign firms mitigated the socialist ideology against private entrepreneurs and entrepreneurship. As observed by Estrin et al. (2006), the legacy of communism was not conducive to entrepreneurial activity, as reflected by the government policies enacted and social attitudes shaped during the communist period. The Marxist socialist ideology, which favored public ownership and discriminated against private businesses, has been one of the major obstacles to China’s local entrepreneurship development. From the early 1950s to the early 1980s, private entrepreneurship was “virtually eradicated and was a political taboo” (Kshetri, 2007). People were obsessed with the fear of accusations of being “capitalist.” Not until 1999 did the Chinese Constitution endorse private businesses as “an important part of the socialist market economy,” and by then, FIEs had been operating in China for two decades. The beneficial effect of foreign firms on China’s economic development facilitated the shift of the official ideology from a planned economy and public ownership toward a market economy and private entrepreneurship. This point is reflected in China’s constitutional amendments in 1988, 1999, and 2004. After all, foreign firms were also privately owned, and their operations in China did not harm “socialism.” In other words, the successful operations of foreign firms in China and mutually beneficial cooperation between the two sides lowered the ideological barrier to the entry of local private businesses, although private firms have not gained a de facto equal position with state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and FIEs.

Previous studies have argued that FDI may exert both a positive spillover effect and a negative crowding-out effect on domestic entrepreneurship (Meyer, 2004; Kim, 2019; Zhang, 2022; Thompson and Zang, 2023; Zhao, 2023). The negative effect of FDI on local entrepreneurial activities occurs because foreign companies compete for domestic resources that may otherwise be used by domestic firms (Meyer, 2004). Specifically, foreign companies may recruit local management talent with more competitive payments than domestic employers do. Some talent may be tied up as high-salaried employees in foreign-invested firms instead of starting their own businesses. In this sense, the presence of foreign firms increases the opportunity cost for local potential entrepreneurs to undertake entrepreneurial activities (De Backer and Sleuwaegen, 2003). Foreign companies may also deter potential domestic entrants by raising technology barriers (Ayyagari and Kosova, 2010). These arguments are also supported by evidence in the literature. Using panel data from 100 countries during the period 2001–2018, Ha et al (2021) find that a higher level of greenfield investment has a harmful effect on the level of total and opportunity-driven entrepreneurial activities in host economies.

In China, a distinctive mechanism may lower the negative effect of FIEs on local businesses, that is, the close link between local economic performance and political turnover (promotion or demotion). During China’s reforms, the central government granted local leaders “the ultimate authority in allocating economic resources” in their jurisdictions. Local officials compete for FDI because foreign investment promotes local economic growth more effectively. Local economic performance has become “the most important criterion for higher-level officials to evaluate lower-level officials” and thus political turnover (Li and Zhou, 2005). In addition, better economic performance implies more tax revenues under discretion and more rent-seeking opportunities for local government officials (Nie et al. 2013). Therefore, local government officials are sensitive to the relationships between foreign companies and local firms. They are unlikely to allow foreign and domestic firms to crowd out and offset each other, thus harming local economic growth. This political turnover mechanism in China makes the crowding-out effect (substitutability effect) less likely to occur than the positive spillover effect (complementarity effect) in China’s local regions.

The above positive demonstration or spillover effects and negative crowding-out effects work in opposite directions. The net effect of FDI on entrepreneurship in host countries, therefore, cannot be foreseen without data. This study attempts to empirically identify the net effect of FIEs on local entrepreneurship at the provincial level in China and to examine the changes in this effect over time.

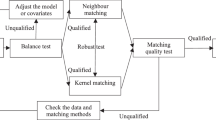

Econometric specification

Model

Our baseline specification is the following fixed effects model:

where \({\mathrm{ln}}({{entrepreneurship}}_{{it}})\) is the dependent variable (i.e., the log number of newly registered private firms) for province \(i\) in year t. \({d}_{i}\) is a provincial fixed effect: it represents the time-invariant individual effects that may affect provincial entrepreneurship. \({\lambda }_{t}\) is the time fixed effect. \({u}_{{it}}\) are idiosyncratic shocks. Controls represent independent variables other than FDI. The parameter we are interested in is \(\beta\). Table 1 reports the definitions and measurements of the variables used in the regression analysis.

Variables

Entrepreneurs are individuals who create new businesses (Hebert and Link, 1989). Therefore, we use the number of newly established private firms per 10,000 people to measure entrepreneurship in a province in this study. This measure is widely used in the literature. For example, Jimenez et al. (2020) use “newly registered firms” to measure entrepreneurship in a cross-country study of the impact of educational levels on entrepreneurship. Zhao (2018), however, used the urban nonpublic sector employment share to measure “business creation entrepreneurship” in a study of the impact of entrepreneurship on economic growth during China’s economic transition. However, private employment growth is not equivalent to business creation; it also means business expansion. We admit that there is not a perfect and universally accepted measure for entrepreneurship. Our measure in this study suffers from the shortcoming of failing to distinguish the industries of the new firms or their size.

The entry of foreign firms is measured by the amount of accumulated FDI per capita. Because capital depreciates over time, we choose a 5% annual depreciation rate, which is usually adopted in the literature (Li et al., 2009; Zhao, 2013). It may seem arbitrary to choose a 5% rate, but when we change the depreciation rate from 0 to 10%, the coefficient and significance of FDI do not change much. Moreover, we use FDI per capita to consider the various population sizes of different provinces. For example, the population of Guangdong is ~35 times that of Tibet.

More formally, FDI stock is calculated as follows:

Here, \({K}_{{it}}\) and \({K}_{i,t-1}\) are the FDI stocks in province \(i\) and in years t and t-1, respectively. \({I}_{{it}}\) is the FDI flow in province \(i\) and year t. \({\rm{\delta }}\) is the annual deprecation rate, which we set as 5%. After we calculate \({K}_{{it}}\) for every province and every year, we then convert them into Chinese currency yuan (CNY) according to each year’s average exchange rate between the U.S. dollar and Chinese yuan, and then deflate them by the CPIs of China with 1980 as the base year. We use the Chinese CPI as the deflator because we are examining the effect of FDI on Chinese domestic entrepreneurship and foreign capital can only be spent in China after it is converted into Chinese currency. Notably, FDI can be used to purchase equipment overseas. In the literature, some authors use U.S. CPI to deflate FDI just because FDI is measured in U.S. dollars in official statistics (Yao and Wei, 2007; Zhao, 2013). We also tested this deflator as a robustness test and found that the results remained basically unchanged. We then divide these constant price FDI stocks by each province’s population in each year to convert them into “constant price FDI stocks per capita,” which is the key independent variable in our regressions.

We choose FDI stock per capita rather than FDI flow per capita as the key independent variable because all existing FIEs affect local businesses and potential entrepreneurs, not just entrants. Even so, we use FDI flow as an alternative in our robustness check. The estimate is significant at the 1% level as well, although it is smaller in magnitude.

We also include different combinations of control variables in Eq. (1). We include two demographic variables, the elderly dependency ratio (elderly) and the birth rate (birth), to control for the effect of demography on entrepreneurship because they may both have an impact on entrepreneurship decisions. As argued by Liang et al. (2018), entrepreneurship is a matter of young people, and too many older people in a society may slow entrepreneurship. China’s society is aging. From 1992 to 2019, China’s elderly dependency ratio increased from 9.3 to 17.8%. The birth rate may affect current entrepreneurship decisions. First, having more children may push parents to start businesses to earn more money to support a larger family. Second, parents with babies may find that time is more flexible in running a business than in choosing a salaried job. They can take care of babies at the same time as they can run a shop. Over our sample period, China’s birth rate decreased from 18.2‰ to 10.5‰.

The government is an indispensable part of an economy’s institutional environment. We include government expenditures as a share of GDP (govt/gdp) to capture the role of government, as used by many studies in the literature (Friedman, 1980; Zhao, 2018); it also serves as an indicator of macroeconomic stability (Easterly and Rebelo, 1993). We then control for fixed asset investment divided by GDP (invest/gdp) to capture the capital accumulation rate of a province.

In the control variables set, we also include human capital, infrastructure, and financial services. They are all relevant to entrepreneurial decisions. We use the number of students enrolled in college per 10,000 people (education) to proxy for an economy’s human capital level. This measure has been widely used in the literature (Yao and Wei, 2007; Zhao, 2013). Lu and Tao (2010) argue that human capital is a determinant of entrepreneurship development.

We use the road mileage per 10,000 square kilometers of land (road) to measure a region’s level of infrastructure. The infrastructure is a public good. Local governments have advertised their high-quality infrastructure to attract FDI. An improved infrastructure should be conducive to local entrepreneurship.

We use loans divided by GDP to measure the level of financial services provided by local financial institutions. Entrepreneurs are usually liquidity constrained (Zhang, 2000); thus, financial support is supposed to be an impetus to local entrepreneurship development.

Endogeneity

FDI could be endogenous because of both omitted variable bias and reverse causality. Too many factors affect entrepreneurship. In China, changes in the institutional environment are particularly relevant to entrepreneurship decisions. For example, local governments have made great efforts to upgrade local infrastructure and business environments to attract foreign investment. However, this move is also conducive to local private entrepreneurship development. To alleviate such omitted variable bias, we attempt to control for variables related to the institutional environment, especially the role of government in the regression equation. In the robustness tests, we use the provincial marketization index and national constitutional amendments to control for institutional variables influencing both FDI and local entrepreneurship.

China began attracting FDI in the late 1970s, but China’s local private enterprises were not officially registered until the late 1980s. In the 1980s China’s private businesses were mainly household proprietorships (getihu). They had barely any influence on foreign-invested firms. The ties between Chinese and foreign firms were rather weak in the 1980s (Liu, 2019). The massive privatization of domestic SOEs and the flourishing of local private enterprises did not occur in China until the mid-1990s (Qian, 2000). Foreign companies came to invest in China in the first two to three decades because of China’s enormous market (potential), cheap labor, and preference policies, including tax breaks, not because of China’s well-developed entrepreneurial businesses. Over the last decade, FIEs have come to China, mainly because China has a large market size, a complete modern industrial system, adequate industrial workers and generous policy dividends (Zhang, 2024).

Moreover, local private enterprises in developing countries usually lag behind their foreign counterparts in terms of both technology and management expertise (Todo et al., 2009; Ge and Chen, 2008). China is not an exception. Since the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, China has implemented approximately thirty years of public ownership and a planned economy as an agrarian and closed economy. Most people were ignorant of the outside world, especially the modern market economy and business practices. This wide gap can be attributed to the fact that on average, the profit margins and salary levels of FIEs are greater than those of Chinese domestic firms (Liu, 2019). It should be much easier for domestic businesses and potential entrepreneurs to learn from FIES than to compete against them. Knowledge spillover is more likely to occur from foreign businesses to domestic businesses. Local potential entrepreneurial decisions, however, are more likely to be affected by the establishment of foreign companies in their neighborhoods. For example, many German companies came to invest in Taicang city of Jiangsu Province because of East China’s enormous market demand for their products (Shi, 2022). As a result, local entrepreneurs established their own businesses to supply parts and components to these German firms. However, we cannot completely rule out reverse causality. With the development of China’s local businesses, newly entered FIEs may choose more entrepreneurial regions with more developed private businesses to facilitate mutual cooperation. In future research, we expect to find a reliable instrumental variable for FIEs to better address this endogeneity issue.

Data

We collected most of the data from the China Statistical Yearbooks (various years) and Statistical Yearbooks of 31 provinces in China (relevant years). These yearbooks are published by the National Bureau of Statistics and provincial statistical bureaus of China. Statistical yearbooks are among the most authoritative sources of data in China. The data on new businesses registered every year in each province are from CnOpenData.Footnote 2 Table 2 presents summary statistics of the variables used in the regression analysis, including the number of observations, mean, standard deviation, maximum, and minimum of each variable. Table 3 is a correlation matrix.

Table 2 shows that in the period of 1992–2019, entrepreneurship, measured by the number of newly established private firms per 10,000 people, varies widely across provinces and over time. The most vibrant entrepreneurship (201 new businesses per 10,000 people) appeared in Fujian Province in 2018, whereas the lowest level occurred in Guizhou Province in 1992, with only 0.24 new private businesses registered per 10,000 people. FDI also varies widely across China. Tianjin has used an accumulated FDI stock per capita of more than $3000, while in some western provinces this figure was less than $10. The large variation in FDI is critical for us to identify how it is correlated with entrepreneurship. Other explanatory variables are also reported in Table 2, and they also exhibit large variations. The intertemporal changes in the outcome variable and key independent variable at the national level are presented in Fig. 1. Table 3 presents the correlation matrix of the variables and shows that there is no serious multicollinearity between the variables.

Regression results

This section presents the baseline empirical results and robustness checks. The main outcome of interest is newly established private firms. We focus on the association between foreign-invested firms and local private business creation. The dependent variable is the log number of newly registered private firms per 10,000 people. Both Tables 4 and 5 show the results produced by the estimation of Eq. (1).

Basic results

We first divide the entire sample period from 1992–2019 into two subperiods, 1992–2001 and 2002–2019. We choose 1992 as the starting year because both FDI and domestic private businesses in China were very limited throughout the 1980s. FDI was even absent in many provinces in the 1980s. Early FDI in China was mainly concentrated in coastal Guangdong and Fujian provinces, which are close to Hong Kong and Taiwan.Footnote 3 China’s private enterprises were not officially registered until 1989.Footnote 4 In early 1992, Deng Xiaoping toured South China and made several famous remarks, which signaled that China would continue its reform and opening-up policy rather than return to the previously planned and closed economy. Deng’s remarks mattered because the 1980s witnessed several twists and turns in government policy toward private entrepreneurship and foreign investment, which aroused doubts and suspicions at home and abroad about China’s future policy.Footnote 5 We set 2001 as the end year of the first subperiod because China entered the WTO in December of that year. Access to the WTO matters because, as argued by Kshetri (2007), China is required to protect property rights and private entrepreneurship if the country intends to gain legitimacy from international organizations such as the WTO.

Table 4 reports the regression results for both subsamples. To allow for heterogeneity and autocorrelation, we estimate all the models with Driscoll-Kraay standard errors, which are robust to very general forms of cross-sectional and temporal dependence when the time dimension becomes large (Driscoll and Kraay, 1998).

The first three columns of Table 4 show that FDI had a positive effect on China’s domestic entrepreneurship from 1992 to 2001, and the effect was statistically significant at the 1% level. In Model (3), for example, if the accumulated FDI stock per capita increases by 1%, local entrepreneurship, measured by the number of newly established private firms, will increase by 0.21%.

We perform the same regressions for the second subsample, 2002–2019. The results also show that FIEs have exerted a positive effect on domestic private business creation. All the estimated coefficients are significant at the 1% level. The estimated coefficients are smaller in the second subsample than in the first subsample. This difference suggests that in the second subsample, intertemporal macroeconomic policies may have played a larger role in domestic entrepreneurship development than in the first subperiod or because the technology gap between domestic and foreign firms is narrower in the second subperiod, which reduces the spillover effect and possibly enlarges the crowding-out effect.

Robustness checks

In this subsection, we perform several sensitivity tests. We first combine the two subsamples into one that covers 31 provinces from 1992 to 2019. As argued by Djankov et al. (2002), other institutional factors, such as “economic liberalization and national governance quality,” play important roles in the creation of private enterprises. In addition, China’s domestic entrepreneurship has been discriminated against by both ideology and policies since the initiation of the planned economy in the 1950s (Lu and Tao, 2010). Unsurprisingly, entrepreneurship development in China has been heavily influenced by government policies since the 1980s, especially policies on the legal status of private enterprises and property rights. Kshetri (2007) also reported that the evolution of entrepreneurship-friendly institutions has influenced China’s entrepreneurship. China amended its Constitution in 1999, which recognized for the first time that “the nonpublic sectors, including individual and private businesses, is an important component of the socialist market economy” and that “the state protects their legal rights and interests.” Till then the official ideology toward private ownership became friendly (Qian, 2000).

The insecurity of private property rights hinders entrepreneurship (Djankov et al., 2006). Entrepreneurs’ concerns about the prospects of their property are important determinants of entrepreneurial decisions, especially in China, where private entrepreneurs lack legal protection (Yang, 2002). The constitutional amendment in 2004 also declared for the first time that “the legal private property of citizens will not be infringed upon,” and “the state protects the private property rights and inheritance of the citizens according to the law.” This 2004 amendment to the Constitution has been widely recognized as “one of the most significant changes” in the development of the private sector since 1978, as the protection of private property was officially endorsed by the Party and government. In China, constitutional amendments also embody changes in official ideology.

As a sensitivity test, we include the dummies for the two constitutional amendments in the regression equation to capture the role of the legal environment in entrepreneurial decisions. The role of regulatory quality in business venturing is also stressed in the literature, such as Polemis and Stengos (2020). Feng (2021) uses China’s provincial-level panel data and finds that institutional quality has a positive effect on nurturing business entrepreneurship. We perform TWFE estimations in Model (7), where constitutional amendment dummies are included. The results of Model (7) still show a robust and significant effect of FDI on local entrepreneurship. The two constitutional amendment dummies have positive and significant effects on local entrepreneurship. Both coefficients are positive and significant at the 1% level. The coefficient of the 2004 amendment is greater than that of the 1999 amendment. One reason is that the 2004 amendment coefficient is the additive effect of both amendments. Another possible reason is that the 2004 amendment focused particularly on the protection of private property, whereas the 1999 amendment was focused on an upgrade of private businesses’ legal status in general. Entrepreneurs are supposed to be more sensitive to the security of their private property than to the status upgrading of private ownership.

We then interact our key independent variable, log(fdi_stock_pc), with each of the two constitutional amendment dummies, and report the results in Model (8). The coefficient of FDI stock per capita still has a positive effect on local entrepreneurship, and the coefficient is significant at the 1% level. The coefficients of the two interaction terms both show significant and negative effects at the 1% level, which implies that compared with the years before the constitutional amendments, the effect of FDI stock on local entrepreneurship is lower after the amendments (the constitution amendments dummies are dropped because of multicollinearity). For example, the estimate in Model (8) suggests that before any constitutional amendment, local entrepreneurship will increase by 0.24% if local FDI stock per capita increases by 1%. After the 2004 constitutional amendment, local entrepreneurship increased by 0.15% (0.24–0.09 = 0.15) if the local FDI stock per capita increased by 1%. The evidence confirms that constitutional amendments decreased the role of FIEs in enhancing local business creation.

As the third step of the robustness check, we use per capita FDI flow rather than stock as the key independent variable. Then we perform fixed effects estimations in models (9) and (10) where years are controlled for. The coefficients of per capita FDI flow also have a positive and significant effect on local private business creation, although the estimates are smaller in magnitude. Local entrepreneurship will increase by ~0.09% if the FDI flow per capita increases by 1%.

Some of the other independent variables also have significant effects on local entrepreneurship. In all 10 models, the ratio of fixed asset investment to GDP (invest/gdp) has positive and significant effects. We argue that fixed investment improves local investment conditions, especially infrastructure. The coefficients of the elderly dependence ratio (elderly) are also positive and significant in all the models. This result may seem counterintuitive but makes sense because elderly people in China usually help take care of their grandchildren for their sons or daughters after they retire rather than being idle. In this context, China is very different from Western countries because of different traditions and cultures. Therefore, it is not surprising that a greater proportion of elderly people offer helping hands to young people rather than hindering China’s entrepreneurship. The birth rate (birth) does not have a stable or certain effect on entrepreneurship. College student enrollment as a share of the population (education) has a positive and significant effect on entrepreneurship in all 10 models except models (2) and (3). This implies that higher education development has a positive effect on entrepreneurship, as more businesses need a growing well-educated labor force.

In summary, the results of all 10 models in Tables 4 and 5 show that the entry of foreign firms exerts a net positive impact on China’s local entrepreneurship. This significant and positive effect is robust to different estimation techniques and combinations of control variables. This result is consistent with some of the studies in the literature, which find that larger inflows of FDI have a positive impact on entrepreneurial activities (e.g., Ayyagari and Kosova, 2010; Jimenez et al., 2020; Zhao, 2023).

Conclusion

In the context of China’s provincial economies, we find that the presence of foreign-invested firms enhances local entrepreneurship. Using TWFE models as the main estimation strategy, we show that accumulated FDI per capita considerably increased the creation of private businesses. Our findings are robust when we change the sets of control variables as well as sample periods. This article contributes to the growing literature devoted to the study of entrepreneurship in general and the study of the impact of foreign-invested firms on domestic entrepreneurship in particular. We also find that the positive effect of FIEs on local entrepreneurship is lower in the second sample period, 2001–2019, than in the first period, 1992–2001. Moreover, compared with years before the constitutional amendments, which are favorable to local entrepreneurship, the positive effect of FIEs on local entrepreneurship after the amendments is lower, as shown by the significant negative coefficient of the interaction terms between FDI and the amendment dummies.

Two questions are not fully answered by this article and require future studies. First, although we have argued that FIEs came to China mainly because of cheap labor and the enormous market, we cannot rule out the possibility that they prefer more entrepreneurial regions when choosing locations. This reverse causality concern should be better solved by using a valid instrumental variable for FIEs. Second, the question of how the role of FIEs has changed in China over time has not been fully answered. Although we partly answer this question in this article, the interactions between FIEs and domestic enterprises need further exploration.

Data availability

To view and download the reproduction dataset and codes for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.25989406.v1.

Notes

According to Chinese statistics, there are three types of “foreign firms” or “foreign-invested enterprises”: China-foreign equity joint ventures, China-foreign cooperative joint ventures, and wholly foreign-owned enterprises. FDI refers to the foreign capital flows in all three types of foreign firms.

Refer to www.cnopendata.com.

Hong Kong is composed of three parts, Hong Kong Island, the Kowloon Peninsula and the New Territories. Hong Kong Island and Kowloon Peninsula became British colonies in 1842 and 1860, respectively. Then, in 1898, the U.K. “leased” the New Territories for 99 years from the Qing Dynasty government. China resumed its sovereignty over the entire Hong Kong in 1997. Macau became a Portugal colony in 1887 and China resumed its sovereignty over Macau in 1999. Taiwan was a Japanese colony from 1895 to 1995. However, Taiwan is not under the control of the mainland Chinese government. According to Chinese statistics, investments from Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan are considered “foreign” capital.

The constitutional amendment in 1988 stipulated for the first time that private enterprises could exist and develop in the fields allowed by the law.

For example, in 1982, the Chinese central government issued a circular on cracking down criminal activities in economic areas, and then, the Wenzhou city government in East China’s Zhejiang Province arrested the eight most famous entrepreneurs in Wenzhou in the name of “speculation crime.” Then, in 1983 and 1984, campaigns against “spiritual pollution” were launched, and a campaign against “bourgeois liberalization” was launched in 1987, both of which demanded a crackdown on private businesses in the name of “rectifying the market” or “attacking speculation.” See Li et al. (2009).

References

Apostolov M (2017) The impact of FDI on the performance and entrepreneurship of domestic firms. J Int Entrep 15:390–415

Ayyagari M, Kosova R (2010) Does FDI facilitate domestic entry? Evidence from the Czech Republic. Rev Int Econ 18(1):14–29

Chen J, Zhou Z (2023) The effects of FDI on innovative entrepreneurship: a regional-level study. Technol Forecast Soc Change 186:122159

De Backer K, Sleuwaegen L (2003) Does foreign direct investment crow out domestic entrepreneurship? Rev Ind Organ 22(1):67–84

Djankov S, La Porta R, Lopez-de-Silanes F (2002) The regulation of entry. Q J Econ 117(1):1–37

Djankov S, Qian Y, Roland G, Zhuravskaya E (2006) Who are China’s entrepreneurs? Am Econ Rev Pap Proc 96(2):348–352

Driscoll J, Kraay A (1998) Consistent covariance matrix estimation with spatially dependent panel data. Rev Econ Stat 80:549–560

Easterly W, Rebelo S (1993) Fiscal policy and economic growth: an empirical investigation. J Monet Econ 32(3):417–458

Estrin S, Meyer K, Bytchkova M (2006) Entrepreneurship in transition economies. In: Casson M (ed) The Oxford Handbook of Entrepreneurship. Oxford University Press, Oxford, p 603–723

Fang H, Chrisman J, Memili E, Wang M (2020) Foreign venture presence and domestic entrepreneurship: a macro level study J Int Financ Mark Inst Money 68:101240

Feng W (2021) How can entrepreneurship be fostered? Evidence from provincial-level panel data in China. Growth Change 52(3):1509–1534

Friedman M (1980) Free to choose: a personal statement. Avon Books, NY, USA

Ge Y, Chen Y (2008) Foreign ownership and productivity of joint ventures. Econ Dev Cultural Change 56(4):895–920

Ha TS, Chu VT, Nguyen MTT, Nguyen DHT, Nguyen, ANT (2021) The impact of greenfield investment on domestic entrepreneurship. J Innov Entrep. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13731-021-00164-6

Hebert R, Link A (1989) In search of the meaning of entrepreneurship. Small Bus Econ 1:39–49

Jian J, Fan X, Zhao S, Zhou D (2021) Business creation, innovation, and economic growth: evidence from China’s economic transition. Econ Model 96:371–378

Jimenez A, Palmero-Camara C, Jimenez-Eguizábal JA (2020) The impact of educational levels on formal and informal entrepreneurship. BRQ Bus Res Q 18(3). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brq.2015.02.002

Kim J (2019) Does foreign direct investment matter to domestic entrepreneurship? The mediating role of strategic alliances. Glob Econ Rev 48(3):303–319

Kshetri N (2007) Institutional changes affecting entrepreneurship in China. J Dev Entrep 12(4):415–432

Li H, Li X, Yao X, Zhang H, Zhang J (2009) Examining the impact of business entrepreneurship and innovation entrepreneurship on economic growth in China. Econ Res J 10:99–108

Li H, Zhou L (2005) Political turnover and economic performance: The incentive role of personnel control in China. J Public Econ 89:1743–1762

Liang J, Wang H, Lazear E (2018) Demographics and entrepreneurship. J Polit Econ 126(S1):140–196

Lin Y (2022) The collections of a gardner: record of communications at the laboratory class of new structural economics. Peking University Press, Beijing, China

Liu J (2019) New China’s utilization of foreign capital in 70 years: Process, effect and major experience. Manag World 11:19–37

Lu J, Tao Z (2010) Determinants of entrepreneurial activities in China. J Bus Ventur 25:261–273

Luo J (2016) FDI forward linkage and technical innovation: does host country R&D expenditure matter? Int Trade Issues 6:3–14

Luo Y, Yan J (2002) International direct investment and China’s modernization. Beijing: China Financial & Economic Publishing House, China

McCloskey D (2010) Bourgeois dignity: why economics can’t explain the modern world. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, USA

Meyer K (2004) Perspectives on multinational enterprises in emerging economies. J Int Bus Stud 35(4):259–276

Nie H, Jiang M, Wang X (2013) The impact of political cycle: Evidence from coalmine accidents in China. J Comp Econ 41(4):995–1011

Onwuka B, Chigozie M (2014) Foreign direct investment and entrepreneurial development in Nigeria (1990-2013). Res J Entrep 2(8):1–17

Polemis ML, Stengos T (2020) The impact of regulatory quality on business venturing: a semiparametric approach. Econ Anal Policy 67:29–36

Qian Y (2000) The process of China’s market transition 1978-1998: the evolutionary, historical, and comparative perspectives. J Inst Theor Econ 156(1):151–171

Shi X (2022) German firms in China: Buyers previously, sellers now. Southern Weekend. https://www.infzm.com/contents/238936

Tang Y, Yu F, Li B (2019) The effects of FDI on firms’ innovation. Wuhan Univ J 72(1):104–120

Thompson P, Zang W (2023) The relationship between foreign direct investment and domestic entrepreneurship: The impact and scale of investment in China. Growth Change 54(3):694–735

Todo Y, Zhang W, Zhou L (2009) Knowledge spillovers from FDI in China: the role of educated labor in multinational enterprises. J Asian Econ 20:626–639

UNCTAD (2021) World Investment Report. United Nations Publications, New York

Xu Y, Yao Y (2015) Informal institutions, collective action, and public investment in rural China. Am Polit Sci Rev 109(2):371–390

Yao S, Wei K (2007) Economic growth in the presence of FDI: the perspective of newly industrializing economies. J Comp Econ 35(1):211–234

Yang K (2002) Double entrepreneurship in China’s economic reform: an analytical framework. J Polit Mil Sociol 30(1):134–147

Zhang C (2022) Foreign-firm experience and entrepreneurial choice in China. J Int Trade Econ Dev 31(4):537–552

Zhang M (2024) Deep integration and embracing the world. Guangming Daily

Zhang W (2000) Why are entrepreneurs liquidity constrained? Ann Econ Financ 1(1):165–188

Zhao S (2013) Privatization, FDI inflows and economic growth: Evidence from China’s provinces, 1978-2008. Appl Econ 45(15):2127–2139

Zhao S(2018) Entrepreneurship and economic growth during China’s economic transformation Seoul J Econ 31(3):307–331

Zhao S (2023) The impact of foreign direct investment on local entrepreneurship: blessing or curse? Asia-Pacific. J Account Econ 30(5):1137–1149

Acknowledgements

The author acknowledges the financial support from the Faculty Research Grant of Macau University of Science and Technology (Grant number is FRG-23-049-MSB). The opinions, findings, and conclusions reported in this article are those of the author and are in no way meant to represent the opinions, views, or policies of any organization.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Shiyong Zhao conceptualized the idea, designed the study, analyzed the data, and wrote and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required as the study did not involve human participants.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, S. Foreign business presence and local entrepreneurship development: evidence from China. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 1224 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03732-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03732-9