Abstract

Although many studies have investigated the differential effects of collaborative pre-task planning (CP), individual pre-task planning (IP), and no pre-task planning (NP) on EFL learners’ writing quality, none has explored such effects under the condition of combining IP with CP and whether such potential effects can be transferred to a new writing task. To bridge this gap, the study assigned 120 Chinese college learners to one of the four groups: CP group, IP group, IPCP group, and NP group. Two argumentative writing tasks were used in this study to collect the required data. To produce task 1, the learners in CP, IP, and IPCP groups were asked to do the relevant planning tasks before writing, while the learners in the NP group were required to write immediately. To explore learning transfer, one week after they produced task 1, the learners in all four groups were required to produce task 2, for which there was no planning time. The results showed that the learners under the CP condition composed writings with higher syntactic complexity than the learners under IP, IPCP, and NP conditions for both two tasks, with no such effects found for other measures of writing quality. Limitations, suggestions for future studies, and implications were discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Task-based language teaching (TBLT), an important field in second language (L2) instruction, has been drawing attention from many researchers. Multiple factors involved in TBLT can affect learners’ L2 task performance, among which the pre-task planning (PTP) factor plays an indispensable role in the improvement of learners’ task performance operationalized as measures of complexity, accuracy, or fluency (CAF). In fact, given the importance of PTP in TBLT, many researchers (e.g., Robinson, 2011; Skehan, 1998; Skehan and Foster, 2001) have regarded PTP as a subcategory of task complexity and contended that manipulating it can promote learners’ language production in terms of CAF measures.

The necessity of exploring PTP-related themes in L2 learning can be demonstrated from both theoretical and pedagogical perspectives. Theoretically, researchers have suggested that L2 learners can benefit from PTP. For example, Kellogg (2008) pointed out that writing is a complex process during which learners consume a large amount of attentional resources to recursively deal with the online planning process, to generate sentences, and to review written texts. Kellogg contended that PTP can be helpful for learners to cope with such a process. Furthermore, Abrams and Byrd (2016) argued that PTP can make linguistic resources and ideas more accessible to learners when writing so that their writing quality is expected to be improved, and such an advantage of PTP can spread throughout different phases of the writing process. In contrast, some researchers have claimed that PTP may not always be beneficial. For instance, Ur (1996) posited that individual differences regarding how to approach a writing task exist in a way that some learners prefer to write immediately and plan during writing, while others prefer to do PTP prior to writing. Similarly, Ortega (1999) pointed out that writing tasks may play a role in determining whether or not PTP is beneficial to learner writing, and the positive effects of PTP emerge when learners are asked to do a challenging task.

Pedagogically, mixed findings were reported with respect to the effects of PTP on learner writing in terms of CAF measures, with studies reporting that PTP exerted positive effects on the measures of learner writing (e.g., Abdi Tabari, 2020), studies reporting that PTP had no impact on learner writing (e.g., Johnson et al., 2012), and studies reporting that PTP had negative effects on learner writing (e.g., Ong and Zhang, 2010). Taken together, these conflicting views and research findings further necessitate the significance of exploring the relationship between PTP and learner writing. In addition, given the constant influence of socio-cultural theory (Vygotsky, 1978) on the L2 writing domain, researchers (e.g., Amiryousefi, 2017; Li and Zhang, 2022; Kang and Lee, 2019) have begun considering the role of collaboration in PTP and investigating whether such planning condition could be superior to other conditions. The results of this strand of studies, as reviewed in the next section, were generally mixed. Moreover, to the best of my knowledge, there has been little research examining the effects of combining collaborative PTP with individual PTP on learner writing and whether such effects can be transferred to new pieces of writing. Thus, this study aimed to address this research gap.

Literature review

This section points out the significance of the study by reviewing studies related to pre-task planning and L2 speaking and writing, collaboration in L2 writing, and individual pre-task planning and collaborative pre-task planning. Then two research questions are raised based on the review.

Pre-task planning regarding L2 speaking and writing

According to Kellogg's (1996) overload hypothesis, the process of doing a task can be viewed as a linear sequence, and PTP may be beneficial for learners to complete the task as providing them with planning time can help reduce their cognitive load consumed when they start the task. Based on this hypothesis, many researchers have extensively examined the effects of PTP on learners’ oral performance. The findings of studies about the measures of fluency and complexity showed that PTP was conducive to the improvement of L2 learners’ oral performance (e.g., Foster and Skehan, 1996; Ortega, 1999; Yuan and Ellis, 2003); however, the studies regarding the measure of accuracy revealed mixed findings, with some reporting positive effects of PTP (e.g., Foster and Skehan, 1996; Tavakoli and Skehan, 2005), while others reporting no significant effects (e.g., Yuan and Ellis, 2003).

In contrast, the effects of PTP on learners’ L2 writing quality have produced a more complicated picture. That is, some studies found that PTP had negative effects on both lexical complexity and fluency measures of learners’ writing (e.g., Ong and Zhang, 2010), while other studies reported positive effects on these two measures (e.g., Abdi Tabari, 2020). For the measure of syntactic complexity, most studies demonstrated positive effects of PTP (e.g., Abdi Tabari, 2021; Abdi Tabari and Wang, 2022; Ellis and Yuan, 2004; Ghavamnia et al., 2013), while some studies indicated no effects (e.g., Johnson, 2011; Rahimi and Zhang, 2018; Rahimpour and Safarie, 2011; Rostamian et al., 2018). The reasons for the mixed findings might be that, according to Ellis (2022), some options involved in the studies were different from each other, such as length of planning time, access to planning notes, use of writing tasks, proficiency level of learners, etc. As a type of individual planning, PTP may have some inherent limitations in improving learners’ writing quality as it does not take into consideration circumstances where learners need to collaborate with each other to optimize their existing linguistic resources so that they can be more likely to achieve better quality.

Collaboration in L2 writing

Since the concept of collaboration was introduced to the L2 writing domain, many researchers have explored its effects on writing quality. There are some potential advantages of collaborative writing that can be echoed by the principles of social constructivism and interaction hypothesis. According to social constructivism, which was proposed by Vygotsky (1978), collaborative writing may be beneficial to student writing in that it can provide students with opportunities to elicit scaffolding from social interaction. Such interaction allows students to co-construct knowledge beyond their individual abilities. Similarly, based on the interaction hypothesis (Long, 1983; Swain, 1985, 1993), collaborative writing may be helpful for student writing since meaning negotiation between students can make it more likely for them to produce writing output with comprehensible language and accurate grammar.

Most studies on collaborative writing were product-oriented with a one-shot design (i.e., learners under either collaborative writing conditions or individual writing conditions were asked to produce one single written text). The results of the one-shot design studies, which compared collaboratively written texts to individually written ones, indicated that the former type of text was more accurate than the latter type (e.g., Fernández Dobao, 2012; McDonough et al., 2018a; Wigglesworth and Storch, 2009), with no such positive effects observed in terms of fluency, complexity, or rubric scores. Moreover, some studies even found that individually-written texts were better than collaborative-written texts in measures of fluency (Fernández Dobao, 2012) and complexity (McDonough et al., 2018b). In addition, the other strand of studies examined whether there was any difference in the texts of posttests written individually between two groups of learners: the group of learners under the experimental condition of collaborative writing intervention and the group of learners under the control condition of individual writing. The results showed that the collaborative writing intervention could help learners individually compose texts with higher rubric scores than the control condition (e.g., Alammar, 2017; Hsu and Lo, 2018; Sagban, 2016).

Despite the potential merits of collaborative writing, such as improving learners’ writing accuracy and rubric scores, cultivating learners’ reflective thinking ability (Storch, 2012), and offering them opportunities to use newly acquired knowledge through scaffolded interaction and co-construction (Hirvela, 1999; Swain and Lapkin, 1998), there are drawbacks as well. For example, one issue with one-shot designs in L2 writing instruction is that it is difficult to ensure each learner under collaborative conditions contributes equally to a collaboratively written text and any positive effects generated from producing such a text can still be sustained in an individually written text. Additionally, learners usually need to spend much time producing a collaboratively written text, which is not realistic to implement in tertiary-level L2 writing classrooms where time is limited (Neumann and McDonough, 2015). During the collaborative review stage, learners can hardly benefit from peer interaction due to the domination of product-oriented characteristics of the stage (Storch, 2005). In this case, pre-task planning with collaboration between learners might be a suitable option for L2 writing learners as it seems to preserve the merits of collaborative writing while addressing its drawbacks.

Individual pre-task planning vs. collaborative pre-task planning

Based on the triadic componential framework proposed by Robinson (2005, 2007), ±planning time, a resource-dispersing variable in the category of task complexity, has been drawing much attention from both L2-speaking researchers (see Johnson and Abdi Tabari, 2022) and L2 writing researchers (see Abdi Tabari, 2022). In contrast, ±few participants, a participation structure variable in the category of task condition of the framework, has been receiving insufficient attention. Though both the variables of ±planning time and ±few participants can be related to pre-task planning, they differ from each other in the number of participants involved in the planning. The variable of ±few participants has been widely operationalized as individual pre-task planning (IP) and collaborative pre-task planning (CP). Several studies have examined whether there were any different effects between the two planning conditions on English as a Foreign Language (EFL) learners’ writing quality (e.g., Ameri-Golestan and Nezakat-Alhossaini, 2017; Amiryousefi, 2017; Li and Zhang, 2022, 2021; Kang and Lee, 2019; McDonough et al., 2018b; McDonough and De Vleeschauwer, 2019), with mixed findings reported. Specifically, Ameri-Golestan and Nezakat-Alhossaini’s (2017) study demonstrated that there was no significant difference between students under the CP condition and students under the IP condition in writing quality of both the posttest and the delayed posttest. Amiryousefi (2017) investigated the effects of teacher-monitored CP, student-led CP, and IP on CAF measures of student writing. The results revealed that each of the three planning conditions had its own benefits as it promoted different dimensions of student writing. Li and Zhang (2021) found that the CP condition, operationalized as small-group student talk, led to higher holistic writing quality and higher improvement in content, organization, vocabulary, and language use than the IP condition; however, this type of positive effect was not found in mechanics.

Similarly, Li and Zhang’s (2022) study demonstrated that students under the CP condition had higher overall quality of argumentation than students under the IP condition, while such an advantage of the CP condition was not found in some dimensions related to argumentation. McDonough et al.’s (2018b) study indicated that students under the CP condition could write more accurate texts that received higher ratings than students under the IP condition. In contrast, McDonough and De Vleeschauwer’s (2019) study showed that IP could help students get higher analytic ratings than CP, whereas CP could help students get higher accuracy than IP. Kang and Lee’s (2019) study revealed that CP was more useful than IP in improving fluency and syntactic complexity of student writing, but not in improving accuracy. Overall, based on interaction hypothesis (Long, 1983) and sociocultural theory (Vygotsky, 1978), CP may be more helpful than IP for the improvement of student writing as collaborative learning activities, such as CP, could help students perform better in tasks imposing high cognitive load than individual learning activities, such as IP (Paas and Sweller, 2012); however, this assumption is not proven in the small number of studies reviewed above since CP was found to be beneficial for only some dimensions of student writing, but not for others. Moreover, there were some studies showing that the possible advantage of CP over IP did not emerge even when complex tasks were involved (e.g., Kang and Lee, 2019). Taken together, the findings of the reviewed studies necessitate further research into the two planning conditions.

Multiple factors may contribute to the inconsistent and, at times, contradictory findings, such as participation structure (i.e., the number of students participating in collaborative planning as a group), student proficiency levels, writing tasks, etc. In addition, since the number of studies examining the effects of CP and IP is relatively small, L2 writing researchers and teachers should be cautious about the results of the studies. More importantly, based on existing research, there has been no study yet exploring the effects of a joint combination of CP and IP on students’ L2 writing quality. Indeed, as Ellis (2022) pointed out, exploring such combination effects can shed more light on the instructional practice of applying planning to L2 writing pedagogy. In addition, some studies (e.g., Kang and Lee, 2019; McDonough et al., 2018a; Xie and Zhu, 2023) examining the effects of CP and IP on student writing only focused on the writing task in which different planning conditions were implemented, without considering the transfer effects of such conditions on a new writing task. According to Long (2015), transfer effects of a task occur when learners’ performance on a certain task can be transferred to other tasks. The instructional value of practicing with a task should be called into question if the transferring effect of the task is not explored (James, 2008). Additionally, according to Kolb’s (1984) Experiential Learning Theory, learners need to deeply conceptualize the task they do and actively experiment with it by doing a new task to optimize what they have learned during the process. For the present study, assigning learners to do the pedagogic writing task may facilitate their understanding of the different planning conditions to make it more likely for them to conceptualize the conditions, and asking them to complete a new writing task may allow them to apply and experiment with what they have learned from the pedagogical task. Therefore, examining the transfer effect of tasks in this study holds practical significance. Taken together, the current study aimed to address the aforementioned research gap by investigating the following research questions:

-

1.

What are the effects of four types of planning conditions, namely CP, IP, IP and CP, and NP on Chinese EFL learners’ L2 writing in terms of complexity, accuracy, and fluency?

-

2.

Is there a difference between the four groups in terms of transferring effects from the pedagogic task to a new task?

Methods

Design

This study adopted a between-group quasi-experimental method design to address the research questions. This design was used because the main purpose of the study was to examine whether students under the four different planning conditions (i.e., CP, IP, IP and CP, NP) perform differently in terms of CAF dimensions of the pedagogic writing task and whether there was any learning transfer from the pedagogic task to a new writing task.

Participants

The participants of this study were 120 EFL freshmen students who enrolled in a College English course at a university located in southwest China. The students met for two sessions per week, with each session lasting 90 min. Based on the English teaching and learning curriculum approved by the university, two teachers holding master's degrees in English applied linguistics taught the students of the four classes using the same teaching materials, with each of them teaching two classes. The students majored in obstetrics, medical examination, health therapy, and stomatology. All students were between 18 and 21 years old and had learned English for almost 9 years. None of them had any experience of studying abroad and living in English-speaking countries.

To ensure all the students’ English proficiency was comparable at the beginning of the study, their scores on English tests in the National College Entrance Exam (NCEE) were collected. All students must take the NCEE in order to be enrolled in universities, and studies have shown that this test can be used to gauge students’ English proficiency (Cheng and Qi, 2006). Based on the scores, their English proficiency was at the B1 level of the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages. A one-way ANOVA was run to examine their English proficiency after collecting the scores of the test. When the study started, the students were preparing for College English Test-Band 4 (CET-4), which is a nationally standardized English test in China. Passing CET-4 can secure the students a university diploma and enhance their competitiveness in job-hunting after graduation. Meanwhile, as pointed out by Erkan and Saban (2011), the students often have difficulty in improving their writing quality when preparing for the CET-4. Thus, they expressed strong motivation to participate in the study in the hope that they could find effective ways of enhancing their writing quality.

Task

The genre of argumentative writing was used as the writing task in this study for two reasons. First, this type of genre is widely adopted in both domestic and international English proficiency tests for Chinese tertiary students (Huang and Zhang, 2020), so it is hoped that asking them to write with the genre could help arouse their learning interest and promote their learning motivation. Second, L2 students’ writing proficiency can be relatively accurately measured through the argumentative writing genre (Teng and Zhang, 2020). To avoid the influence of topic bias on student writing quality, the two writing topics (see Appendix 1) were selected from the database of CET-4 and were familiar to students since they were closely related to their daily lives. Students were offered 30 min to write at least 150 words on each topic. Since there were four groups of students in this study and all of them were under different planning conditions, they were provided different writing task instructions in Chinese prior to doing the pedagogic task based on which group they were in.

Procedure

This study was conducted in EFL freshmen’s regular classes. The students in all groups produced one written text in one session. This study lasted 2 weeks, with four sessions in each week. Thus, this study included eight sessions in total since it asked the students in each of the four groups to produce two texts. After securing the consent of the students and their teachers, the first researcher went into the teachers’ scheduled classes to collect the students’ written texts. The students in this study were divided into four groups according to four different planning conditions: CP, IP, IP and CP, and NP. Each student in the four groups was required to produce two written texts, with one for the pedagogic task and another for the new task. Students in four intact EFL classes were recruited to participate in this study, and each class was randomly assigned one of the four planning conditions. Following previous studies (e.g., Crookes, 1989; Foster and Skehan, 1996; Kang and Lee, 2019), no specific instructions were provided concerning the use of planning time. The students in this study self-selected their partners to collaboratively plan their texts so that the results of the study could be compared to other studies (e.g., Kang and Lee, 2019; McDonough et al., 2018b). Also, in line with previous studies (e.g., Ellis and Yuan, 2004; McDonough et al., 2018b; Ong and Zhang, 2010; Rostamian et al., 2018), the students were given ten minutes of planning time prior to writing.

Specifically, the students under CP condition were asked to plan with their self-selected partners for ten minutes. During that time, they could discuss the writing topic by taking notes, but the notes were taken away to ensure a more precise assessment of their writing quality since they might directly copy language from the notes. The discussions were only allowed within a pair. After the students finished their discussions, they were asked to separate to individually complete their texts on paper in 30 min with no access to dictionaries or other relevant materials. The students under the IP condition undertook a similar process to the students under the CP condition. The only difference was that they did not have a partner. The students under the IPCP condition also had 10 min in total to plan, and the 10 min were evenly distributed between the two conditions, with 5 min for each condition. When the students were doing IPCP in class, the teacher provided clear instructions to ensure that they strictly followed the time allocation and planning sequence of the two planning conditions. It should also be noted that the reason for sequencing the two conditions in this order was to maximize the exploration of the instructional value of the IP condition by excluding any possible intervening effects of the CP condition. After all, the students might be likely to use what they have learned under CP conditions to do IP if they are allowed to do CP first. For the students under NP condition, they were asked to start to write immediately after being presented with the writing topics, and they had 30 min to finish their writing. Moreover, to explore whether there were any transfer effects of the planning conditions to a new writing task, this study asked all the students to complete a second writing task (i.e., a new task) one week after they completed the first task (i.e., a pedagogic task), without any planning time provided.

Measures

In this study, CAF measures were adopted to analyze students’ writing quality. The CAF measures play a crucial role in capturing learners’ performance on a certain task (Norris and Ortega, 2009; Skehan, 1998), and researchers in the L2 writing domain have been using the triad of the measures to gauge students’ writing quality. The complexity measure was categorized into lexical and syntactic complexity dimensions with a variety of metrics because of its multi-faceted nature (Housen et al., 2012). Lexical complexity was gauged from lexical sophistication and diversity, and two metrics were considered in total. The first metric was the logarithmic word frequency (log frequency) of all words (LFAW) in the academic section of the Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA) (Davies, 2008), which was used to reflect lexical sophistication; the second metric was all words hypergeometric distribution diversity (AW HD-D), which was used to reflect lexical diversity. Calculated through the tool for the automatic analysis of lexical sophistication (TAALES) (Kyle et al., 2018), COCA LFAW was chosen because large corpora are often referred to enable researchers to compare the frequency of lexical information in student writing against the frequency of lexical information in corpora (Johnson, 2017). A lower lexical log frequency value indicates higher lexical sophistication (Yoon, 2018; Yoon and Polio, 2017). Calculated through the tool for the automatic analysis of lexical diversity (TAALED) (Kyle et al., 2021), AW HD-D was chosen because it can be more effective to minimize the effect of essay length than many other diversity metrics (Zenker and Kyle, 2021).

This study used Lu’s (2010) L2 syntactic complexity analyzer (L2SCA) to analyze the syntactic complexity of student writing. In line with Norris and Ortega (2009), a total of four indices in the L2SCA were used in this study: 1. the mean length of T-units (MLT), defined as an independent clause together with any dependent clause(s) attached, 2. dependent clause per T-unit (DC/T), 3. the coordinate phrases per clause (CP/C), and 4. complex nominal per clause (CN/C). These four indices were chosen because researchers (e.g., Housen et al., 2012; Johnson, 2017) have clarified the multiple components of syntactic complexity and have pointed out that the assessment of syntactic complexity should incorporate general, subordination, coordination, and phrasal complexity measures. Specifically, in this study, the general complexity measure is referred to as the index of MLT, the subordination measure is referred to as the index of DC/T, the coordination measure is referred to as the index of CP/C, and the phrasal measure is referred to the index of CN/C.

Following previous studies (e.g., Karim and Nassaji, 2020; Vasylets and Marín, 2021), this study used an error ratio to investigate students’ writing accuracy. An error ratio is calculated by all errors in an essay divided by the total number of words, and multiply 100. Following Vasylets and Marín (2021) study, this study took into account the errors of grammar and vocabulary based on Standard English. The errors of capitalization, spelling, and punctuation were not counted (Wigglesworth and Storch, 2009). To ensure inter-rater reliability regarding error coding, the first and the second authors independently hand-coded 10% of the dataset. After obtaining a reliability coefficient above 0.85, the first author hand-coded the remaining data. Finally, fluency was assessed by the total number of words composed by the students within the 30-min time limit.

Results

This section consists of two parts, with the first part reporting the results of the first research question and the second part reporting the results of the second research question.

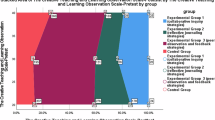

Research question 1

The first research question asked whether different planning conditions of CP, IP, IP and CP and NP had differential effects on the students’ writing quality manipulated as CAF. To answer this question, several one-way ANOVAs were conducted to test if significant differences existed. Table 1 presents the results for CAF measures. In terms of syntactic complexity, significant differences were found among the planning conditions for MLT [F(3, 116) = 11.44, p = 0.000], DC/T [F(3, 116) = 5.56, p = 0.001], CP/C [F(3, 116) = 40.46, p = 0.000], and CN/C [F(3, 116) = 8.97, p = 0.000], respectively. Tukey’s HSDs were used to determine the location of significance between the planning conditions. With regard to MLT, the analysis revealed that the mean length of T-units composed by the students under CP (M = 14.10, SD = 1.83) was longer than the students under IP (M = 13.13, SD = 2.96), the students under IPCP (M = 12.64, SD = 1.95), and the students under NP (M = 11.67, SD = 2.15). For DC/T, the analysis demonstrated that the students under CP wrote more dependent clauses per T-unit (M = 0.53, SD = 0.14) than the students under IP (M = 0.35, SD = 0.20) and the students under NP (M = 0.39, SD = 0.19). Regarding CP/C, the analysis indicated that the students under CP produced more coordinate phrases per clause (M = 0.52, SD = 0.13) than the students under IP (M = 0.23, SD = 0.13), the students under IPCP (M = 0.23, SD = 0.11), and the students under NP (M = 0.20, SD = 0.14). For CN/C, the students under CP composed more complex nominals per clause (M = 1.46, SD = 0.28) than the students under IP (M = 1.18, SD = 0.32), the students under IPCP (M = 1.14, SD = 0.27), and the students under NP (M = 1.09, SD = 0.33).

With respect to lexical complexity, accuracy, and fluency, one-way ANOVAs did not show any significant differences. Specifically, no significant differences were found in the LFAW [F(3, 116) = 0.54, p = 0.656] and AW HD-D [F(3, 116) = 2.47, p = 0.066] of lexical complexity. For LFAW and AW HD-D, the students under CP had a mean value of 2.96 (SD = 0.10) and a mean value of 0.78 (SD = 0.03). The students under IP had a mean value of 2.99 (SD = 0.10) and a mean value of 0.77 (SD = 0.04). The students under IPCP had a mean value of 2.97 (SD = 0.09) and a mean value of 0.78 (SD = 0.04). The students under NP had a mean value of 2.98 (SD = 0.09) and a mean value of 0.76 (SD = 0.03). Also, no significant differences were found in accuracy measured by error ratio [F(3, 116) = 2.34, p = 0.077] and fluency measured by total number of words [F(3, 116) = 1.53, p = 0.212]. For error ratio and total number of words, the students under CP had a mean value of 6.08 (SD = 3.00) and a mean value of 174.37 (SD = 30.09). The students under IP had a mean value of 5.67 (SD = 3.08) and a mean value of 172.47 (SD = 28.54). The students under IPCP had a mean value of 4.88 (SD = 2.50) and a mean value of 164.73 (SD = 21.91). The students under NP had a mean value of 6.72 (SD = 2.38) and a mean value of 162.03 (SD = 24.17).

Research question 2

The second research question explored whether there was any difference between the four groups in terms of transferring effects from the pedagogic writing task (task 1) to the new writing task (task 2). A series of one-way ANOVAs were performed to answer this question. Table 2 presents the results for CAF measures. Similar to the results of the first research question, significant differences were found among the planning conditions in all four indices of syntactic complexity: MLT [F(3, 116) = 12.33, p = 0.000], DC/T [F(3, 116) = 8.41, p = 0.000], CP/C [F(3, 116) = 6.10, p = 0.001], and CN/C [F(3, 116) = 12.52, p = 0.000]. Tukey’s HSDs were conducted to determine the location of significance between the planning conditions. With respect to MLT, the analysis indicated that the mean length of T-units produced by the students under CP (M = 14.86, SD = 3.45) was longer than the students under IP (M = 12.13, SD = 1.88), the students under IPCP (M = 12.34, SD = 2.12), and the students under NP (M = 11.44, SD = 1.31). For DC/T, the analysis revealed that the students under CP wrote more dependent clauses per T-unit (M = 0.64, SD = 0.27) than the students under IP (M = 0.41, SD = 0.18), the students under IPCP (M = 0.43, SD = 0.18), and the students under NP (M = 0.43, SD = 0.20). For CP/C, the analysis showed that the students under CP produced more coordinate phrases per clause (M = 0.31, SD = 0.07) than the students under IP (M = 0.21, SD = 0.12), the students under IPCP (M = 0.21, SD = 0.12), and the students under NP (M = 0.22, SD = 0.11). For CN/C, the students under CP composed more complex nominals per clause (M = 0.94, SD = 0.25) than the students under IP (M = 0.67, SD = 0.14), the students under IPCP (M = 0.69, SD = 0.13), and the students under NP (M = 0.78, SD = 0.22).

With regard to lexical complexity, accuracy, and fluency, one-way ANOVAs did not demonstrate any significant differences. Specifically, no significant differences were found in the LFAW [F(3, 116) = 2.27, p = 0.084] and AW HD-D [F(3, 116) = 2.36, p = 0.075] of lexical complexity. For LFAW and AW HD-D, the students under CP had a mean value of 2.98 (SD = 0.08) and a mean value of 0.80 (SD = 0.03). The students under IP had a mean value of 3.01 (SD = 0.09) and a mean value of 0.78 (SD = 0.03). The students under IPCP had a mean value of 2.98 (SD = 0.07) and a mean value of 0.80 (SD = 0.03). The students under NP had a mean value of 2.96 (SD = 0.09) and a mean value of 0.80 (SD = 0.03). Also, no significant differences were found in accuracy measured by error ratio [F(3, 116) = 1.74, p = 0.163] and fluency measured by total number of words [F(3, 116) = 0.543, p = 0.654]. For error ratio and total number of words, the students under CP had a mean value of 7.45 (SD = 3.17) and a mean value of 163.40 (SD = 30.36). The students under IP had a mean value of 6.84 (SD = 3.51) and a mean value of 166.23 (SD = 22.35). The students under IPCP had a mean value of 6.92 (SD = 2.64) and a mean value of 171.67 (SD = 25.39). The students under NP had a mean value of 5.66 (SD = 3.12) and a mean value of 166.17 (SD = 24.07).

Discussion

Through examining the effects of four planning conditions on students’ writing quality, the findings of the study showed that the students under the CP condition composed writings with higher syntactic complexity than the students under the IP condition for both the pedagogic task and the new task, which was in line with the findings of some former studies (e.g., Kang and Lee, 2019). However, the findings were inconsistent with the studies of McDonough and De Vleeschauwer (2019) and McDonough et al. (2018a, 2018b), whose findings revealed no significant difference between CP and IP in syntactic complexity. The reason for the inconsistency might lie in the difference in text types that entailed different levels of task complexity. Specifically, in the studies conducted by McDonogh and colleagues, the researchers required students to offer solutions to a social problem, which might be viewed as a less complex task. In contrast, the present study asked students to critically analyze a social phenomenon by presenting its benefits and challenges, which might be seen as a more complex task. According to Zhan et al. (2021), Chinese EFL students tend to produce writings of higher syntactic complexity when they do a more complex writing task. Furthermore, the inconsistent findings also revealed that different genres or text types might play a role in the effects of planning conditions. In addition to text types, the other possible explanation about the significant advantage of CP in the syntactic complexity of student writing is the unstructured pre-writing task used in this study. According to some recent studies (e.g., Do, 2023; Ebadijalal and Moradkhani, 2023; Pospelova, 2021), students doing unstructured pre-writing tasks under CP condition usually pay greater attention to writing content with which they can brainstorm ideas for their subsequent writing. With more ideas generated by this way, it is likely for students to use more subordinations to express ideas in texts, leading to higher syntactic complexity (McDonough et al., 2018b).

For lexical complexity, the results of the study were not consistent with the results of Xie and Zhu's (2023) study, in which IP led to higher lexical complexity than CP. The reason might be that in Xie and Zhu’s study students were required to complete a continuation task, which is a less cognitively complex task than the argumentative task in the present study. Although collaboration might make it more likely for students to share their linguistic knowledge to improve lexical complexity, this likelihood could be offset by students’ investment of attentional resources in transactional activities during CP (Kirshcner et al., 2011), particularly when students are doing a less cognitively complex task, such as the one in Xie and Zhu’s study. Furthermore, students in Xie and Zhu’s study could refer to the reading material while they did the continuation task and they were also encouraged to aligned linguistically with the material. In this way, it is possible that students under the IP condition were more likely to focus on the lexical knowledge in the reading material to improve the lexical complexity of their writings than students under the CP condition whose focus on lexical knowledge might be distracted by pair discussions on other aspects of writing, such as content, organization, task management, etc. (McDonough et al., 2018a). Taken together, students under the IP condition in Xie and Zhu’s study composed the continuation task with higher lexical complexity than students under CP condition.

In terms of writing accuracy, the findings of the current study were in line with the findings of McDonough et al. (2018b), Kang and Lee (2019), and Xie and Zhu (2023) in that CP did not lead to higher writing accuracy than other planning conditions, such as IP or NP; however, the findings of the current study differed from the findings of Li and Zhang (2021), McDonough et al. (2018a), and McDonough and De Vleeschauwer (2019), which reported that CP was helpful for students in improving their writing accuracy. Several explanations might be considered to discuss the findings of the present study. First, according to McDonough et al. (2018b), the positive effects of collaboration on accuracy occur only when students collaboratively compose texts rather than when students collaboratively plan for texts prior to composing. In the current study, the students under different planning conditions composed their writings individually, which might offset any potential advantages of CP. For example, the students under the CP condition might have been in a better position to improve their writing accuracy through collaborative processing of linguistic issues; however, asking them to compose their writings individually after planning could have made it more difficult for them to enhance writing accuracy. Second, group size in CP condition might be one reason that accounts for the different findings between the current study and Li and Zhang’s (2021) study. Specifically, in Li and Zhang’s study, they assigned six students as a group, and the group size was larger than the present study in which a group was only composed of two students. It is possible that a group of six students could gather more knowledge from their linguistic repertoire to improve writing accuracy than could a group of two students. Third, the type of pre-writing tasks used in the studies by McDonough et al. (2018a) and McDonough and De Vleeschauwer (2019) as compared to the present study may also contribute to the divergent findings in students’ writing accuracy. In the two studies conducted by McDonough and colleagues, the researchers adopted a structured pre-writing task in which students were provided with a task handout with guiding questions and explicit instructions to help them generate, select, and organize ideas. This type of task may alleviate students’ cognitive load while writing so that they can focus more on the improvement of their writing accuracy.

In contrast, the present study used an unstructured pre-writing task in which students were simply asked to plan the writing task with their partners by taking notes that would be taken away when they started writing. As McDonough et al. (2018a) claimed, a structured pre-writing task may contribute to students’ writing accuracy through exerting a relatively more direct impact on students’ subsequent writing. Similarly, Kim et al. (2022) found that a structured pre-writing task elicited more episodes from students during CP than did an unstructured pre-writing task, and these episodes were found to predict higher task scores assessed across categories such as content, organization, language, and mechanics. Fourth, the focus of student discussion during CP can also play a role in the different findings regarding writing accuracy. According to some studies investigating EFL students’ talk during CP (e.g., Li et al., 2020; Neumann and McDonough, 2015), students discussed writing content most frequently. The current study also found evidence of such frequency after examining the students’ notes taken during CP. Thus, it can be assumed that students under the CP condition in the current study focused their discussion more on the contents of the subsequent writing task, with insufficient discussion on linguistic issues.

For fluency, the results of the study were differential from Kang and Lee’s (2019) and Mohammadi et al. (2023) studies. In Kang and Lee’s study, it was found that students under the CP condition composed writings with greater fluency than students under the IP condition. The reason for the differential findings between Kang and Lee’s study and the current study may be that student participants in their study were 8th graders with limited English proficiency, while student participants in the current study were undergraduates. As posited by Kang and Lee, student participants in their study benefited more from CP with respect to fluency because their limited English proficiency increased the likelihood of collaboration on how to organize their ideas into words. They could, therefore, write more fluently than undergraduate students. In addition, the divergent findings between Mohammadi et al. (2023) study and the current study were mainly due to the differences in the design of prewriting task and the provision of planning time. In their study, Mohammadi et al. provided students under the CP condition with a worksheet for their planning, and the students were asked to list as many ideas as they could on the worksheet within 15 min of planning time. The study also did not specify whether the students were allowed to keep their worksheets during writing. It is possible that, with both the available worksheet and extended planning time, the students in that study can write more fluently. In contrast, the current study provided students with only 10 min to collaboratively plan their writing without any worksheets, which, not surprisingly, led to the finding of an insignificant effect of CP on fluency.

Conclusion

The purpose of this study was to explore the effects of four types of planning conditions (i.e., CP, IP, IPCP, and NP) on EFL learners’ L2 writing quality and to investigate whether planning conditions could influence learning transfer from the pedagogic task to the new task. The results indicated that the learners under CP condition produced writings with higher syntactic complexity than the learners under IP, IPCP, and NP conditions for both tasks. In this section, the limitations of the study are discussed, followed by the implications.

Limitations

This study is not without limitations. First, this study did not investigate whether individual differences such as motivation, self-efficacy, language aptitude might influence the observed advantage of CP across both the pedagogic task and the new task. Future studies should consider using validated instruments (e.g., questionnaires, interviews) to delve into the potential mediating role of individual differences in the effects of planning conditions. Second, this study was only concerned with the planning implementation regarding participatory structure manipulated as individual and collaborative planning. Future studies could explore the relationships between other implementation options and students’ writing quality. Specifically, options worth exploring include time allocation to planning, focus of planning, access to planning notes, guidance for planning, and language use during planning (Ellis, 2022). For example, it might be interesting to explore the potential different effects of guided and unguided planning on student writing and students’ perceptions of the two types of planning tasks. Third, this study did not investigate how students under different planning conditions actually used the planning time and how they perceived the roles of planning conditions in learning transfer from the pedagogic task to the new task. Future studies could address these questions through think-aloud protocols and self-report questionnaires, with the former being used to identify students’ cognitive, emotional, and motivational processes while planning and the latter being used to identify students’ perceptions of planning tasks (Panadero, 2023). Finally, the student participants in this study were Chinese EFL students with intermediate proficiency levels, so researchers and L2 writing teachers should be cautious about generalizing the results of this study to students with other proficiency levels or in different instructional contexts.

Implications

This study failed to observe advantages of CP in the majority of CAF measures except for syntactic complexity. Like any experimental studies in the field, this study has the following implications. First, if students under CP condition are asked to do unstructured pre-writing task, teachers should be involved in the task to provide assistance when necessary. Also, the help should be tailored based on teachers’ observations or judgements of students’ individual differences. With teachers’ involvement and tailored assistance, it is expected that students can benefit more from such task. Second, while implementing CP in L2 writing class, teachers may want to use writing tasks or genres with which students can tack advantage of CP. Referring to Tavakoli and Rezazadeh (2014), an argumentative writing task might impose more cognitive load on learners than a narrative writing task. This is particularly the case during CP stage (Franken and Haslett, 2002) as an argumentative task can elicit high content interactivity that requires student under the CP condition to synthesize much discrete information (Sweller, 1994). In such cases, it was likely for the students to feel concerned or even anxious when doing an argumentative task, which might, in turn, offset any potential advantages of CP. Third, pre-task planning, implemented individually or collaboratively, should be used with caution by writing teachers in EFL context. Students’ acceptance and familiarity with planning should be thoroughly examined prior to applying it to writing instruction. In other words, students may not want to include such planning in their writing process if they are used to online planning. For those who are willing to incorporate it into their writing process, they may need more assistance from teachers as they might lack experience with it.

Data availability

The dataset generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available as supplemental materials. The dataset consists of two Excel forms, with each form related to one writing task. Each form has one column representing the independent variable and eight columns representing eight dependent variables, namely, MLT, DCT, CPC, CNC, LFAW, AWHDD, Accuracy, Fluency.

References

Abdi Tabari M (2020) Differential effects of strategic planning and task structure on L2 writing outcomes. Read Writ Q 36(4):320–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/10573569.2019.1637310

Abdi Tabari M (2022) Investigating the interactions between L2 writing processes and products under different task planning time conditions. J Second Lang Writ 55:100871. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2022.100871

Abdi Tabari M, Wang Y (2022) Assessing linguistic complexity features in L2 writing: understanding effects of topic familiarity and strategic planning within the realm of task readiness. Assess Writ 52:100605. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asw.2022.100605

Abdi Tabari M (2021) Task preparedness and L2 written production: investigating effects of planning modes on L2 learners’ focus of attention and output. J Second Language Writ 52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2021.100814

Abrams ZI, Byrd DR (2016) The effects of pre-task planning on L2 writing: Mind-maping and chronological sequencingin a 1st-year German class. System 63:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2016.08.011

Alammar M (2017) The role of collaborative vs. individual writing in improving essay writing: a case study on Saudi learners. Int J Arts Sci 10(2):653–667

Ameri-Golestan A, Nezakat-Alhossaini M (2017) Long-term effects of collaborative task planning vs. individual task planning on Persian-speaking EFL learners’ writing performance. J Res Appl Linguist 8(1):146–164

Amiryousefi M (2017) The differential effects of collaborative vs. individual prewriting planning on computer-mediated L2 writing: transferability of task-based linguistic skills in focus. Comput Assist Lang Learn 30(8):766–786. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2017.1360361

Cheng L, Qi L (2006) Description and examination of the National Matriculation English Test. Lang Assess Q 3:53–70. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15434311laq0301_4

Crookes G (1989) Planning and interlanguage variation. Stud Second Lang Acquis 11(4):367–383

Davies M (2008) The corpus of contemporary American English (COCA). Available Online at Www.English-Corpora.Org/Coca

Do HM (2023) Pedagogical benefits and practical concerns of writing portfolio assessment: suggestions for teaching L2 writing. TESL-EJ 27(1):1–7

Ebadijalal M, Moradkhani S (2023) Impacts of computer-assisted collaborative writing, collaborative prewriting, and individual writing on EFL learners’ performance and motivation. Comput Assist Language Learn 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2023.2178463

Ellis R (2022) Does planning before writing help? Options for pre-task planning in the teaching of writing. ELT J 76(1):77–87. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccab051

Ellis R, Yuan F (2004) The effects of planning on fluency, complexity, and accuracy in second language narrative writing. Stud Second Lang Acquis 26(1):59–84. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263104026130

Erkan DY, Saban Aİ (2011) Writing performance relative to writing apprehension, self-efficacy in writing, and attitudes towards writing: a correlational study in Turkish tertiary-level EFL. Asian EFL J 13(1):164–192

Fernández Dobao A (2012) Collaborative writing tasks in the L2 classroom: Comparing group, pair, and individual work. J Second Lang Writ 21(1):40–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2011.12.002

Foster P, Skehan P (1996) The influence of planning and task type on second language performance. Stud Second Lang Acquis 18(3):299–323. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263100015047

Franken M, Haslett S (2002) When and why talking can make writing harder. In: Ransdell S, Barbier ML (eds) New directions for research in L2 writing. Kluwer Academic, Dordrecht, The Netherlands, pp. 208–229

Ghavamnia M, Tavakoli M, Esteki M (2013) The effect of pre-task and online planning conditions on complexity, accuracy, and fluency on EFL learners written production. Porta Linguarum (20), 31–43

Hirvela A (1999) Collaborative writing instruction and communities of readers and writers. TESOL J 8(2):7–12

Housen A, Kuiken F, Vedder I (2012) Dimensions of L2 performance and proficiency: Complexity, accuracy and fluency in SLA. John Benjamins

Hsu H, Lo Y (2018) Using wiki-mediated collaboration to foster L2 writing performance. Lang Learn Technol 22(3):103–123. 10125/44659

Huang Y, Zhang LJ (2020) Does a process-genre approach help improve students’ argumentative writing in English as a foreign language? Findings from an intervention study. Read Writ Q 36:339–364. https://doi.org/10.1080/10573569.2019.1649223

James MA (2008) The influence of perceptions of task similarity/difference on learning transfer in second language writing. Writ Commun 25(1):76–103. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741088307309547

Johnson MD (2017) Cognitive task complexity and L2 written syntactic complexity, accuracy, lexical complexity, and fluency: a research synthesis and meta-analysis. J Second Lang Writ 37:13–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2017.06.001

Johnson MD, Abdi Tabari M (2022) Task planning and oral L2 production: a research synthesis and meta-analysis. Appl Linguist 43(6):1143–1164. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amac026

Johnson MD, Mercado L, Acevedo A (2012) The effect of planning sub-processes on L2 writing fluency, grammatical complexity, and lexical complexity. J Second Lang Writ 21:264–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2012.05.011

Johnson MD (2011) Planning in second language writing. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Northern Arizona University

Kang S, Lee J (2019) Are two heads always better than one? The effects of collaborative planning on L2 writing in relation to task complexity. J Second Lang Writ 45:61–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2019.08.001

Karim K, Nassaji H (2020) The revision and transfer effects of direct and indirect comprehensive corrective feedback on ESL students’ writing. Lang Teach Res 24(4):519–539. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168818802469

Kellogg RT (2008) Training writing skills: a cognitive developmental perspective. J Writ Res 1:1–26

Kellogg RT (1996) A model of working memory in writing. In: Levy CM, Ransdell S (eds) The science of writing: theories, methods, individual differences, and applications. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah, NJ, pp. 57–71

Kim Y, Kang S, Nam Y, Skalicky S (2022) Peer interaction, writing proficiency, and the quality of collaborative digital multimodal composing task: comparing guided and unguided planning. System 106:102722. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2022.102722

Kirshcner F, Paas F, Kirshcner AP, Janssen J (2011) Differential effects of problem-solving demands on individual and collaborative learning outcomes. Learn Instr 21:587–599. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2011.01.001

Kolb DA (1984) Experiential learning: experience as the source of learning and development. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ

Kyle K, Crossley S, Berger C (2018) The tool for the automatic analysis of lexical sophistication (TAALES): version 2.0. Behav Res Methods 50:1030–1046. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-017-0924-4

Kyle K, Crossley SA, Jarvis S (2021) Assessing the validity of lexical diversity indices using direct judgments. Lang Assess Q 18(2):154–179. https://doi.org/10.1080/15434303.2020.1844205

Li HH, Zhang LJ (2021) Effects of structured small-group student talk as collaborative prewriting discussions on Chinese university EFL students’ individual writing: a quasi-experimental study. PLoS ONE 16:e0251569. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0251569

Li HH, Zhang LJ (2022) Investigating effects of small-group student talk on the quality of argument in Chinese tertiary English as a foreign language learners’ argumentative writing. Front Psychol 13:868045. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.868045

Li HH, Zhang LJ, Parr JM (2020) Small-group student talk before individual writing in tertiary English writing classrooms in China: nature and insights. Front Psychol 11:570565. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.570565

Long M (2015) Second language acquisition and task-based language teaching. John Wiley & Sons, Malden

Long MH (1983) Native speaker/non-native speaker conversation and the negotiation of comprehensible input. Appl Linguist 4(2):126–141. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/4.2.126

Lu X (2010) Automatic analysis of syntactic complexity in second language writing. Int J Corpus Linguist 15(4):474–496. https://doi.org/10.1075/ijcl.15.4.02lu

McDonough K, De Vleeschauwer J (2019) Comparing the effect of collaborative and individual prewriting on EFL learners’ writing development. J Second Lang Writ 44:123–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2019.04.003

McDonough K, De Vleeschauwer J, Crawford W (2018b) Comparing the quality of collaborative writing, collaborative prewriting, and individual texts in a Thai EFL context. System 74(1):109–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2018.02.010

McDonough K, De Vleeschauwer J, Crawford WJ (2018a) Exploring the benefits of collaborative prewriting in a Thai EFL context. Lang Teach Res 23:685–701. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168818773525

Mohammadi K, Jafarpour A, Alipour J, Hashemian M (2023) The impact of different kinds of collaborative prewriting on EFL learners’ degree of engagement in writing and writing self-efficacy. Read Writ Q 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/10573569.2022.2157783

Neumann H, McDonough K (2015) Exploring student interaction during collaborative prewriting discussions and its relationship to L2 writing. J Second Lang Writ 27:84–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2014.09.009

Norris JM, Ortega L (2009) Towards an organic approach to investigating CAF in instructed SLA: the case of complexity. Appl Linguist 30(4):555–578. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amp044

Ong J, Zhang LJ (2010) Effects of task complexity on the fluency and lexical complexity in EFL students’ argumentative writing. J Second Lang Writ 19(4):218–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2010.10.003

Ortega L (1999) Planning and focus on form in L2 oral performance. Stud Second Lang Acquis 21(1):109–148

Paas F, Sweller J (2012) An evolutionary upgrade of cognitive load theory: using the human motor system and collaboration to support the learning of complex cognitive tasks. Educ Psychol Rev 24:27–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-011-9179-2

Panadero E (2023) Toward a paradigm shift in feedback research: five further steps influenced by self-regulated learning theory. Educ Psychol 58(3):193–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2023.2223642

Pospelova T (2021) The collaborative discussion model: developing writing skills through prewriting discussion. J Lang Educ 7(1):156–170. https://doi.org/10.17323/jle.2021.10748

Rahimi M, Zhang LJ (2018) Effects of task complexity and planning conditions on L2 argumentative writing production. Discourse Process 55(8):726–742. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163853x.2017.1336042

Rahimpour M, Safarie M (2011) The effects of on-line and pre-task planning on descriptive writing of Iranian EFL learners. Int J Engl Linguist 1(2):274–280. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijel.v1n2p274

Robinson P (2005) Cognitive complexity and task sequencing: studies in a componential framework for second language task design. Int Rev Appl Linguist Lang Teach 43(1):1–32. https://doi.org/10.1515/iral.2005.43.1.1

Robinson P (2007) Task complexity, theory of mind, and intentional reasoning: effects on L2 speech production, interaction, uptake and perceptions of task difficulty. Int Rev Appl Linguist Lang Teach 45(3):193–213. https://doi.org/10.1515/iral.2007.009

Robinson P (2011) Second language task complexity, the cognition hypothesis, language learning, and performance. In: Robinson P (ed) Second language task complexity: researching the cognition hypothesis on language learning and performance. John Benjamins, Amsterdam, Netherlands, pp. 3–37

Rostamian M, Fazilatfar AM, Jabbari AA (2018) The effect of planning time on cognitive processes, monitoring behavior, and quality of L2 writing. Lang Teach Res 22(4):418–438. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168817699239

Sagban AA (2016) The effect of collaborative writing activities on Iraqi EFL college students’ performance in writing composition. Basic Education College Magazine for Educational and Humanities Sciences, p. 26

Skehan P (1998) A cognitive approach to language learning. Oxford University Press

Skehan P, Foster P (2001) Cognition and tasks. In: Robinson P (ed) Cognition and second language instruction. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, pp.183–205

Storch N (2005) Collaborative writing: product, process, and students’ reflections. J Second Lang Writ 14:153–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2005.05.002

Storch N (2012). Collaborative writing as a site for L2 learning in face-to-face and online modes. In: Kessler G, Oskoz A, Elola I (eds) Technology across writing contexts and tasks. CALICO, San Marcos, TX, pp. 113–129

Swain M (1993) The output hypothesis: just speaking and writing aren’t enough. Can Mod Lang Rev 50(1):158–164. https://doi.org/10.3138/cmlr.50.1.158

Swain M, Lapkin S (1998) Interaction and second language learning: two adolescent French immersion students working together. Mod Lang J 82(3):320–337. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.15

Swain M (1985) Communicative competence: some roles of comprehensible input and comprehensible output in its development. In: Gass S, Madden C (eds) Input in second language acquisition. Newbury House, pp. 235–256

Sweller J (1994) Cognitive load theory, learning difficulty, and instructional design. Learn Instr 4(4):295–312

Tavakoli M, Rezazadeh M (2014) Individual and collaborative planning conditions: effects on fluency, complexity and accuracy in L2 argumentative writing. Teach Engl 32(4):85–110

Tavakoli P, Skehan P (2005) Strategic planning, task structure and performance testing. In: Ellis R (ed) Planning and task performance in a second language. Benjamins, Amsterdam, pp. 239–277

Teng LS, Zhang LJ (2020) Empowering learners in the second/foreign language classroom: can self-regulated learning strategies-based writing instruction make a difference? J Second Lang Writ 48:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2019.100701

Ur P (1996) A course in language teaching: practice and theory. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Vasylets O, Marín J (2021) The effects of working memory and L2 proficiency on L2 writing. J Second Lang Writ 52:100786. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2020.100786

Vygotsky LS (1978) Mind in society: the development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

Wigglesworth G, Storch N (2009) Pair versus individual writing: effects on fluency, complexity and accuracy. Lang Test 26(3):445–466. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265532209104670

Xie Y, Zhu D (2023) Effects of participatory structure of pre-task planning on EFL learners’ linguistic performance and alignment in the continuation writing task. System 114:103008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2023.103008

Yoon HJ (2018) The development of ESL writing quality and lexical proficiency: suggestions for assessing writing achievement. Lang Assess Q 15(4):387–405. https://doi.org/10.1080/15434303.2018.1536756

Yoon HJ, Polio C (2017) The linguistic development of students of English as a second language in two written genres. Tesol Q 51(2):275–301. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.296

Yuan F, Ellis R (2003) The effects of pre‐task planning and on‐line planning on fluency, complexity and accuracy in L2 monologic oral production. Appl Linguist 24(1):1–27. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/24.1.1

Zenker F, Kyle K (2021) Investigating minimum text lengths for lexical diversity indices. Assess Writ 47:100505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asw.2020.100505

Zhan J, Sun JY, Zhang LJ (2021) Effects of manipulating writing task complexity on learners’ performance in completing vocabulary and syntactic tasks. Language Teach Res https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688211024360

Acknowledgements

This study is supported via funding from Zunyi Medical University project number (FB-2022-2). This study was funded by Zunyi Medical University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The author collected the data, conducted the analysis, and drafted and revised the work. The author agreed to publish the final version of the work and to undertake any responsibilities with regard to it.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Scientific Research Ethics Committee at the School of Foreign Languages, at Zunyi Medical University, Number: 2024-028. The researchers confirm that all research procedures were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations involved in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent

Written consent was obtained from the participants to use their writings for research purposes. The participants signed the following endorsement: ‘I have read and under stood the provided information regarding research purpose and have had the opportunity to ask questions. I understand that my participation is voluntary and that I am free to withdraw at any time, without giving a reason and without cost’.

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fan, N. Effects of collaborative vs. individual pre-task planning on EFL learners’ L2 writing: transferability of writing quality. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 1365 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03758-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03758-z