Abstract

Resource nationalism has a complex economic, political, and cultural history and reality. The evolution of the supply and demand structure of the global mineral metal market influences it. It is closely linked to the “economic-political” system within resource-rich countries. We analyze the ‘economic-political’ logic of resource nationalist behavior using the two-tier game theory. We examine 261 cases of resource nationalism since 1990 and test the theoretical hypotheses using quantitative techniques. The results show that rising mineral prices are the main trigger for contemporary resource nationalism. However, ideology, institutional quality, social climate, and economic dependence within resource countries play a non-negligible role. Resource wealth dependence in host countries makes it difficult for policymakers to escape national resource interventions. We argue that (1) The global economic trading system imbalance is the root of resource nationalism. (2) Resource nationalism is an endeavor by resource-rich countries to seek entitlements from mineral resource endowments. (3) Resource nationalism is not a zero-sum competition in the national economic trading system. In the face of the potential risks posed by resource nationalism to the global supply of minerals, the relevant interest groups should have sufficient strategic reserves to cope with the possible game of interests.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Resource nationalism is increasingly emerging in resource-rich countries in South America, Africa, and Southeast Asia (Liu et al. 2023; Prior et al. 2012; De Graaff, 2011). Economic growth and technological advances increasingly depend on critical metals such as copper, nickel, cobalt, lithium, and rare earth elements (REEs) (Vivoda, 2023; Ciacci et al. 2020). Geopolitics and geo-economics of critical minerals are becoming increasingly intense and have brought about dramatic volatility and widespread increases in mineral prices (IEA, 2023). Resource rents are again at the center of exchanges between host countries and international resource companies (Ostrowski, 2023).

The tendency of governments in resource-rich countries to intervene in the distribution of resource rents for political and economic gain has remained unbroken for a century (Pryke, 2017; De Graaff, 2011). This variety of tensions between extractive countries and international resource companies has been labeled resource nationalism. As a cyclical phenomenon, the most recent resource nationalism began at the turn of the century with conflicts between international resource companies and resource-rich countries (Amedanou and Laporte, 2024; Ostrowski, 2023). Many studies have attempted to gain perspective on the motives and consequences of resource nationalism from multiple dimensions, including resource power, national self-determination, fiscal dependence, political elections, economic speculation, and corruption (Amedanou and Laporte, 2024; Dou et al. 2023; McNabb, 2023; Laing, 2020; Fontaine et al. 2018; Kaup and Gellert, 2017). However, we still lack an understanding of resource nationalism from a transnational perspective due to resource-rich countries’ heterogeneity of political, economic, cultural, and social structures (Dou et al. 2023; Kaup and Gellert, 2017; Ng’ambi, 2018). The overlap between geopolitical tensions in powerful countries and a strong climate of economic nationalism within resource-rich countries has made the challenges of resource nationalism in the era of ‘high metal density’ increasingly salient (Ali, 2023; Riofrancos, 2023; McNulty and Jowitt, 2022; Nassar et al. 2020). We assembled information from papers (Li and Adachi, 2017), international organizations (IEA, 2022; IEA, 2023), consulting firms (Ernst and Young, 2013), newspapers, and government publications (USGS, 2020) to construct a national-scale dataset on resource nationalism. We hope to uncover some common factors behind resource nationalism through quantitative analyses.

The contrast between lagging economic growth and rich resource endowments has made minerals and energy a frequent weapon of resistance against economic inequality in the global South (Berrios et al. 2011). From the nationalization of resources in the 1960s and 1970s to the metals super-cycle of the first two decades of this century, resource nationalism has recurred and become deeply embedded in the world economic order (Kohl and Farthing, 2012; Kretzschmar et al. 2010). There is a combination of the desire of resource countries to seek economic self-empowerment and economic independence, as well as the aim of using resource rents to support domestic political games (Laing, 2020; Cotula, 2020; Myadar and Jackson, 2019). Whatever the motives for resource nationalism, it is difficult to avoid the fundamental question of whether natural resource wealth can contribute to national economic growth (James and Rivera, 2021). The empirical evidence is overwhelmingly negative, with resource endowments dragging down the economic growth rate in resource countries, i.e., a ‘resource curse’ (van Krevel and Peters, 2024; Savoia and Sen, 2021). Corrupt political institutions, self-serving elites, poor governance capacity, and deteriorating legal and business environments have been used to explain the political economy logic behind this phenomenon (Furstenberg and Moldalieva, 2022; Savoia and Sen, 2021). However, there have been more than 200 recorded national-level resource nationalist actions involving 42 countries since the turn of the century (Appendix, Table A.1). The repetition of resource nationalism has inevitably proved to have lucrative benefits in return (Childs, 2016; Koch and Perreault, 2019) perhaps not in the form of national welfare (Prather, 2024). Policymakers’ interest considerations tend to be more diverse and complex (Myadar and Jackson, 2019). The contradiction between the resource curse and the record of resource nationalism raises the question: what drives resource nationalism? In an era of increasingly scarce political mutual trust and high nationalism among powerful countries (China, the US, and the EU), a proper understanding of this issue is vital to addressing the fragility of global supply chains for critical minerals (Voskoboynik and Andreucci, 2022).

Experiential, historical, and ideological national differences in resource extraction make it challenging to generalize the generic logic of resource nationalism (Kaup and Gellert, 2017; Stevens, 2008). Despite the significant economic speculative overtones of the current wave of resource nationalism, intra-state politics and ideology remain prominent (Kilambo, 2023). It can be argued that resource nationalism is a ‘sub-optimal’ equilibrium between multiple, contradictory, and incommensurable interests of interest actors (Materka, 2011). Despite cyclical changes, resource nationalism has retained its quest to “assert the state’s strategic control over resources for political and economic purposes and to enhance the developmental spillovers of extractive activities” (Marston, 2019; Bremmer and Johnston, 2009). We wish to look beyond national boundary constraints and examine resource nationalism on a global scale. By analyzing the complex relationship between political, economic, and social elements, we analyze the policy logic of resource nationalism. To provide innovative ideas for building a more resilient resource global governance system.

Our contribution is summarized in two aspects. First, we use double game theory to analyze the logic of the “emergence, climax, decline, and reemergence” of resource nationalism in this century. We are more inclined to explore the commonalities among countries and the driving role of economic factors. This perspective is different from the existing analysis of resource nationalism. Second, we construct a new global-scale resource nationalism dataset. We hope to enrich the study of resource nationalism from a data-driven perspective.

We explain the data sources, variable selection, and model construction in Section 3 and analyze the regression results in Section 4. Section 5 discusses the findings in-depth, considering international literature and case studies.

Why resource nationalism happens

There is a growing global need for critical minerals (lithium, cobalt, nickel, copper, etc.) to respond to technological transitions and climate change. Changes in clean energy and transportation electrification have put significant pressure on the supply of critical metals. The imbalance between supply and demand pushed up international mineral prices. Countries with large reserves are being tested on how to respond to the evolution of structural trends in the supply of critical minerals. Resource nationalism is the basis on which the concerns and perspectives of these countries are considered.

Driving forces of resource nationalism

Nation states have a long history of seeking to benefit from the ownership and control of natural resources under their jurisdiction (Ng’ambi, 2018). Since the mid-twentieth century, the world has experienced three waves of resource nationalism. We find an essential role for national ideologies and extractive histories in many studies and reviews (Agneman et al. 2024; Hancock et al. 2018; Rosales, 2018). However, a notable trend is the increased role of economic motives (Laing, 2020). Resource nationalism has been crucial in shifting from “a laissez-faire attitude towards extractive FDI to actively seeking to maximize the contribution of foreign companies to government revenues and economic development” (Paul and Pablo, 2016).

Resource nationalism is a complex issue. It is rooted in resource-rich countries’ historical, cultural, political, and economic structural evolution (Pryke, 2017; Kaup and Gellert, 2017). It isn’t easy to generalize the phenomenon in a unified framework. For example, Mongolia’s resource-based economic speculation has a very different logic from the resource governance strategies of the Chavez regime in Venezuela. They may be interpreted differently if viewed as equilibriums struck by various interest groups around the distribution of natural resource wealth. Resource nationalism often involves disputes between the host country and international capital over expropriation, taxation, export, and local content policies (Paul and Pablo, 2016). Policymakers must have good reasons to act when they know they will lose foreign investor confidence. We argue that there is a game rationale for these actions. That is, the government of a resource country creates a homogeneous state with different interest groups at both the international and domestic levels (Arbucias, 2020).

Interest groups around natural resource wealth have multidirectional, contradictory, and incommensurable claims. Groups may find an equilibrium of interests, such as investment in Indigenous communities by international resource companies or establishing local metal processing plants. This game equilibrium can be broken as economic conditions and domestic ideologies change. At this point, resource-nationalist behavior is risky (Fontaine et al. 2019). This is when the government can break the pact and implement resource-nationalist trade/industrial policies (Hellinger, 2016). As a result, we can see that resource nationalism often emerges with high metal and energy prices and subsides when metal and energy markets are depressed (Rosales, 2018; Kaup and Gellert, 2017). Part of this is that rising global resource prices generate excess profits and change the benefit functions of interest groups. Resource country governments want to capture the producer surplus from higher prices (Barlow, 2022). Domestic interest groups, in turn, want to capture the economic dividends of rising global resource prices (Kalyuzhnova and Nygaard, 2009).

On the other hand, the public wealth attributes of natural resources make it difficult to escape from ideological influences. Populism, resource extraction, elections, and corruption are often closely linked (Myadar and Jackson, 2019). Populism as a stimulant of political activity has made resource nationalism a fashionable approach to resource governance (Poncian, 2019). Berrios et al. (2011) used rigorous quantitative analysis to confirm that political leaders from all sides of the ideological spectrum advocate, pursue, or maintain nationalization. Evidence from Bolivia, however, leads to the opposite conclusion, that social movements adopting the main framework of resource nationalism led to an irregular regime change in 2005 (Kohl and Farthing, 2012). When social progress slowed, and social unrest occurred in South Africa, different forms of resource nationalist appeals emerged in society (Lane and Kamp, 2013). This reminds us to look at resource nationalism from a more holistic perspective.

The two-tier game of resource nationalism

The theory of two-tier games was initially used to address the problem of how national leaders can strike a balance between domestic and international games in international negotiations (Putnam, 1988). With the growth of international trade and foreign investment, the two-tier game has been expanded to include international trade, outward investment, and the negotiation of regional integration agreements (Evans et al. 1993). Host governments are faced with balancing attracting foreign investment and capturing resource wealth. Resource nationalism is rooted in the internal ordering of resource rents within countries, but it also faces constraints on foreign investment. Rents can be seen as a form of “ground rent” in classical economics. Host countries and transnational corporations compete for the superior economic benefits of favorable natural conditions (ore grades, natural monopolies). Host countries consider mineral reserves to be “owned” by the State. But they also need foreign investment and technology to help grow their resource sectors (Hancock et al. 2018). At the same time, governments want to keep more resource rents in their countries to fulfill social, economic, and political objectives. The limited nature of resource rents determines the irreconcilability of conflicts at both international and domestic levels. Rational behaviors made by the government of the resource country at one level are often seen as irrational at the other level and may ultimately lead to unfavorable consequences (Kahn, 2013). The crux of the matter lies in the winning set, the set of all international levels that can reach an agreement supported by interest groups at the domestic level (Putnam, 1988).

The game between the host country and the international resource firms

The game between international resource companies and resource-rich countries has been going on for almost a century, and they are both antagonistic and united (Kaup and Gellert, 2017). Multinational mining companies follow the theory of comparative advantage and search for production partners globally to divide labor (Fattouh and Darbouche, 2010). They maximize their company’s profit through capital factor, technology factor, and management factor inputs. For example, minerals are extracted in resource countries such as Africa and South America and purified and smelted in metal processing plants in China. After the 1990s, as natural resources were reopened to international capital, free trade and production rules were built around the Washington Consensus. It includes Europe and the United States as financial R&D consumption centers, China as a production and manufacturing center, and several extensive resource and energy countries as resource goods export centers (Jin and Zhang, 2022).

However, the quest to maximize resource rents in resource countries has been persistent and has risen again with the advent of the ‘resource super-cycle’ (Sarsenbayev, 2011). Despite the demise of expropriation, competition over resource rents remains intense and diverse (Amedanou and Laporte, 2024; Dou et al. 2023). These include resource taxation, royalties, state capital shares, contract renegotiation, mineral export bans, and local content policies (Chen et al. 2024). Resource assertiveness brings resource finance and strengthens regime legitimacy (Laing, 2020; Warburton, 2017; Cawood and Oshokoya, 2013). Host countries face choices between foreign capital, technological needs, and resource wealth in this process. International resource companies must find an equilibrium between resource endowments, production allocation, and rent-seeking costs (De Graaff, 2011). Differences in bargaining power led to heterogeneity in the location of the equilibrium point. For example, Indonesia banned bauxite and nickel exports and promoted metal processing, and Bolivia loosened its lithium nationalization policy. It is difficult to say that an optimal strategy exists due to differences in national extractive histories, cultures, and ideologies.

Domestic games around resource rents

There is a more complex set of games within resource countries. The drivers of resource nationalism are complex and are a combination of economic, political, and social issues (Cawood and Oshokoya, 2013). Resource finance, ideology, social sentiment, and even electoral politics have been used to support analyses of resource nationalism (Osman et al. 2022; Laing, 2020). We attempt to explore the logic of resource nationalism using a political economy framework that integrates political, economic, and social elements (Huber, 2019). Whether it is a representative democracy, an authoritarian government, or an authoritarian government, there is a need to garner political support from the majority group (Pedersen et al. 2019). Resource nationalism as a tactic of industrial and trade policy is consistent with this policy logic (Mommer and Araque, 2002). We can see resource nationalism in trade and industrial protection studies (Grossman and Helpman, 1994).

The complexities of resource nationalism are well understood. From Bolivia, Peru, Vietnam, and Mongolia to Zambia, the role of resource extraction in politics, the spatiality of power and subjectivity, and the global nature of extractive industries have been repeatedly discussed (Frederiksen, 2023). While there is no shortage of comparative analyses between countries, little is known about the national variability in the mix of political, economic, and social factors (Pedersen et al. 2020). The non-linear link between policy equilibrium and the payoff function constituted by communities, workers, elite groups, and ideologies remains a research gap (Nie, 2003). Building gain functions that integrate resource, political, economic, and social elements is challenging in domestic games. We review the research on game strategies for trade and industrial policymaking, significantly the seminal articles in the field of political economy, the theory of Political Contributions by Stephen et al. (1989), the Protection for Sale model by Grossman and Helpman (1994), and the transaction cost model of power delegation by Epstein and O’Halloran (1999) all provide theoretical support for our analysis. That is the acquisition of the equilibrium of the multi-interest group game under resource power.

Foreign capital and technical support, resource financial dependence, economic patronage, extractive history, and ideology are deeply embedded in host country resource decisions (Wang et al. 2011). The boundaries between the extractive economy and extractive politics are blurring, and the fusion of market and resource power is becoming more apparent (Click and Weiner, 2010). Instruments such as expropriation and confiscation have gradually been replaced by policies such as resource taxation, equity allocation, and local content (Lange and Kinyondo, 2016). We are in the era of the new resource economy. The economic value accompanying critical metals accumulates rapidly downstream in industries, such as lithium, cobalt, nickel, and rare earth in electric vehicles, clean energy, and high-tech industries. On the other hand, critical metal reserves are highly concentrated in a few countries and need more technological substitution. This brings about national economic speculative sentiments and enhances the social climate of industrial self-reliance and economic autonomy (Cotula, 2020; Poncian, 2019). Politicians are also happy to follow this trend (Kohl and Farthing, 2012). Sentiments of national resource intervention in host countries often remain positively associated with national economic and especially fiscal dependence on mineral endowments (Cawood and Oshokoya, 2013). Weak governance systems, the absence of the rule of law, and political instability exacerbate this interventionist sentiment (Ganbold and Ali, 2017). The state’s ruling group has incentives to seek more significant economic gains, social benefits, and political dividends through new games. We constructed a schematic diagram of a two-tier game of resource nationalism and elucidated its intrinsic mechanism of action (Fig. 1). Based on the above analyses, we formulate three hypotheses:

-

1.

The global price increase of resource goods is the main trigger of contemporary resource nationalism.

-

2.

The domestic political game is the intrinsic driving factor of resource nationalism policy generation.

-

3.

The cause of resource nationalism is the dependence of resource countries’ economies on mineral resource wealth.

The light gray A- and A+ represent the gaming of domestic interest groups. The dark-colored A represents the optimal equilibrium of the domestic game. The dark-colored B represents the equilibrium of the international interest group’s game. The game’s equilibrium for dark-colored B relies on the game of rents around extractive industries on the right.

Materials and methods

Design of model

Resource nationalism is seen as fueling volatility in global mining markets. And increased uncertainty about the resilience of global supply chains for critical metals. It is essential to analyze and quantify the role of domestic and foreign political and economic factors that influence the emergence of resource nationalism policies to establish an early warning mechanism for mineral resource supply. Considering the specificity of the explanatory variable “whether resource nationalist policies are introduced in the resource countries,” to obtain a credible causal inference analysis, we adopt the Binary Choice Model (BCM) to examine the intrinsic reasons for the emergence of resource nationalist policies. We analyze which elements, and under what circumstances, motivate resource governments to deviate from the principles of free trade and market economy. Precisely, we will determine whether a country has a resource nationalism policy (\({{RN}}_{{it}}\)) each year, with \({{RN}}_{{it}}\) = 1 if the policy is in place, and \({{RN}}_{{it}}\) = 0 otherwise. The manifestations of resource nationalism policies include government restriction of foreign capital to invest in the country’s resource sector; government restriction/prohibition of foreign capital from smelting/processing locally; and government ban on the exportation of raw ores; The government’s direct government involvement and control of resource exploration and development practices explicitly stated in the mining law; the government’s requirement of a certain percentage of national employees; and the government’s increase of income/profit tax on foreign investment in the resource industry.

The basic model setup is a binary choice Logit regression on panel data by maximum likelihood estimation, and Eqs. (1)–(4) demonstrate the exact construction process:

Where \({\beta }_{m}\) represents the coefficients of the influencing elements, \({x}_{m}\) is the political and economic elements and the characteristic vectors that influence the introduction of resource nationalism policies, and e and u represent the error terms. The literature review shows that resource nationalism is cyclical and often accompanied by global resource goods price increases. However, the volatility of resource commodity market prices is only a causative factor for the occurrence of resource nationalism policies, and the key driving force still lies in the political group game within the resource countries. Political groups wish to strengthen their bargaining power by capturing the producer surplus of resource price increases. Therefore, the article focuses on the drivers of resource nationalist policies arising from the political situation in resource countries. Based on the theoretical analysis in Section 2, the article further explores how the international resource goods market induces the emergence of resource nationalism through the political game in the resource countries, under the premise of base regression. Equation (5) demonstrates the logic of our study.

Among them, \({P{rice}}_{{it}}\) is the international resource price index, \({{Polite}}_{{it}}\) represents the domestic political game form, and \({Z}_{{it}}\) is some control variables. \({P{rice}}_{{it}}* {{Polite}}_{{it}}\) is the core explanatory variable of the article. The price increase of resource goods is global, not targeting a specific country. In this case, some countries appear to have a resource nationalism policy, which indicates that changing their domestic political situation changes the benefit function of the interested parties and forms a new game equilibrium state. Therefore, we should focus on how resource prices drive the domestic political game and ultimately lead to policymaking.

Data

Data sources

Resource nationalism has a long and extensive history of development. In recent years, as the threat of resource nationalism to global capital activities has intensified, several consulting firms have created resource nationalism threat indices to serve global investment activities. However, resource nationalism events have not yet been tracked and documented globally by a standardized dataset. We follow the methodology of Li and Adachi (2017) and investigate the data for countries that have had at least one year of natural resource rents of no less than 5% of GDP from 2000–2019. In this context, natural resource rents are the sum of rents from crude oil, coal, natural gas, and mineral production, excluding forest rents. Definitions and statistics on oil, coal, gas, and mineral rents are taken from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators database (WDI).

Currently, no database consistently tracks and documents resource nationalism policies, and events globally. We gather records of global resource nationalist policies and events from multiple data sources. 1) Mineral Information from the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). The Minerals Yearbook (Volume III-Regional Reports: International), published by the USGS, provides statistical data on mineral commodities by country. Each report includes government policies and programs, environmental issues, trade and production data, industry structure and ownership, commodity sector development, infrastructure, and a summary outlook, 2) We also collected reports from several industry associations, including the International Council on Mining and Metals (ICMM), The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), 3) Academic papers provided some information. We consolidated this information. Appendix A provides the recorded information on these events. National economic, political, and social data were obtained from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators (WDI) database. Since some data needed to be included, we supplemented them using data from Our World in Data (https://ourworldindata.org/). Both databases provide data interfaces (APIs) in the R language. The globalization index is from KOF Swiss Economic Institute (Gygli et al. 2019).

Construction of the Resource Nationalism Incident Dataset

The construction of the resource nationalism event dataset is a prerequisite for quantitative analysis and a big challenge in the thesis research. First, the scope of resource nationalism events should be clearly defined. Based on the analysis of academic papers, business company reports and industry association reports, we define the resource nationalism events from 35 aspects in six dimensions (Hickey et al. 2020; Ostensson, 2019; Blunt and Sainkhuu, 2015; Table 1). Resource nationalist behavior was considered to have occurred in this country during the current year if an incident from Table 1 appeared in the text. These events covered everything from the most draconian expropriation of mining assets without compensation to minor tax hikes or demands for community social responsibility. The primary data was obtained from the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) Minerals Yearbook (Volume III-Regional Reports: International), with data obtained by extraction from the text. Based on the above criteria, we identified 83 countries as the primary trackers of resource nationalism and collated 1494 texts from which 261 resource nationalism events were recorded.

Variable selection and descriptive statistics

We use a dummy variable, \({{RN}}_{{it}}\), to measure whether a country has introduced a resource nationalism policy, and the definition of a resource nationalism event has been given above. We analyze the theoretical logic behind the emergence of resource nationalism in the section 2. After referring to domestic and international research reviews and case studies, we select core explanatory variables and control variables from three dimensions. (1) Resource goods price index. Much literature and reports from consulting organizations indicate that high global prices of resource goods trigger resource nationalism policies. The article’s theoretical analysis also confirms this assertion’s logic and mechanism. From 1990 onwards, resource nationalism events are mainly targeted at mineral resources; we use the metal.price index to measure the trend of global resource prices. (2) Host country politics. We refer to the research of Wilson (2015) and Li and Adachi (2017) and select the rule of law (ROL), government efficiency (GE), Political Tendency of the Ruling Party (Right or Left), democratization (Polity) in the world governance indicators (Kohl and Farthing, 2012). Meanwhile, Right-wing (Ideology_left) for parties defined as conservative, Christian democratic, or right-wing. Left-wing (Ideology_right) for parties defined as communist, socialist, social democratic, or left-wing. (3) Economic situation of host countries. The dependence of national economies on natural resource wealth is also an essential trigger for resource nationalist policies. The article considers firstly, the economic situation of the resource countries, including the real GDP growth rate (rgdp) and the national income level (NI); and secondly, the dependence of the national economy on natural resource wealth, including natural resource rents (other than forest rents) as a percentage of GDP (RRT) and exports of petroleum, ores, and metals as a percentage of merchandise exports (MEOX). Descriptive statistics for the variables are shown in Table 2.

Result

Base regression

Rising global resource prices as the main trigger of resource nationalist policies

We explain the theoretical logic of resource nationalism events in Section 2. According to the track records of international organizations and research institutes, the increase in global resource prices is an essential trigger for the emergence of economic nationalist behaviors. The quantitative analysis incorporates the global metal price index as a core explanatory variable. It analyzes how metal price volatility affects resource nationalist behavioral decisions in resource countries. Model 1 in Table 3 shows that global metal price growth significantly increases the probability of resource country economic nationalist behavior. We control for economic, political, and trade-related variables in the regression to ensure the robustness of the regression results. The metal price index is derived from the World Bank Commodity Price Data, with 2010 prices set as the base (100; the base of the price index is adjusted to 1). According to the regression results of Model 1, every one percentage point increase in the global metal price index will increase the probability of resource nationalist behavior by 4.39%.

We compare our findings with peer studies with peer studies, showing that the findings align with logical expectations (Obaya, 2021). This suggests a potential producer surplus arising from the increase in global prices of resource goods. Governments of resource countries tend to go about writing this additional dividend of natural resource wealth through administrative and fiscal means. Emerging economies, represented by China, India, and Brazil, have risen rapidly in a relatively stable international economic and trade situation. They have driven strong demand for international metal raw material markets. The global metal price index showed a sustained upward trend in this context. Many resource-exporting governments have intervened in resource extraction and trade in the metal raw materials market supply and demand situation. Our findings show that the first ten years of this century were a high incidence of resource nationalism. Mutual corroboration of theoretical derivation, quantitative analysis, and case studies. It confirms the hypothesis that “the global price increase of resource products is the main trigger of resource nationalism policies.”

Domestic political gaming as an intrinsic driving factor for the generation of resource nationalism policies

We are interested in the role of host politics in resource nationalism. Although the global price increase of resources induced the economic nationalist behavior of resource countries, the internal logic of policy implementation is the political game within the resource countries. Increases in resource prices bring additional monetary benefits that change the benefit function of political groups within resource countries. After controlling for economic and trade factors, we analyze the mechanisms inherent in the domestic political situation that acted to generate the resource nationalism event. The article explores the impact of domestic political formations in resource countries on resource industry and trade policymaking regarding party political, ideological leanings, party turnover, and national governance normalization. Model 2 in Table 3 demonstrates how the three elements affect the probability of resource nationalism events. The results show that there is a greater likelihood that left-wing parties will implement resource nationalism policies compared to right-wing parties and centrists. Reviewing the governance tendencies of left-wing political parties globally, left-wing parties’ economic and political aspirations are more biased towards state intervention than right-wing and centrist parties. There is consistency between the quantitative analysis results and the theory’s logical derivation.

We argue that resource nationalist policies are a product of political games within resource countries. The party rotation/election period is often the most intense period of the game. Some political groups usually propose radical economic initiatives to win the game, such as nationalization, higher profit taxes, and increased employment. We analyze whether party rotation increases the probability of resource nationalism events. The results in Table 3 show that the year following an event of party rotation is the peak year for resource nationalist events. To improve the robustness of the analysis, the paper introduces another more direct indicator, “whether the ruling party has nationalist characteristics” (exact), and the results show that the rule of those parties with significant nationalist characteristics does not increase the probability of resource nationalist events. This result, side by side, confirms our reasoning in the theoretical part of section 2. That is, political parties’ political initiatives are more for political games and are initiatives to increase the game chips of the party.

We also focus on the impact of the normalization of state governance in the host country on the incidence of resource nationalism. The article chooses the effects of two indicators: government legalization and management efficiency. Table 3 shows that government legalization reduces resource nationalist behavior, but government efficiency promotes related events. Governments with a high degree of legalization are more inclined to comply with international economic contracts. At the same time, their domestic tax laws, business laws, and employment policy revisions face a more standardized and rigorous process. In these countries, a more cautious approach to changing prior legal, industrial, and trade policies in the face of additional economic dividends from rising resource prices is more likely.

In contrast, host governments with high levels of governmental efficiency will focus more on capitalizing on the dividends of their mineral wealth. They will use more flexible industrial and trade policies to maximize the economic development opportunities offered by mineral resource endowments. Therefore, when faced with the continued high international mineral market, they are more inclined to adopt a resource nationalism policy.

Resource nationalism policy is the reason for the national economy’s mineral wealth dependence

The sustainable growth of the scale and quality of the national economy is the common goal modern countries pursue. Resource nationalism policies often face criticism and opposition from international organizations, transnational corporations, investment institutions, and countries downstream of the industrial chain. These criticisms also affect the credibility of the governments of resource countries. However, the governments of these countries are still happy to face criticism from the outside world. The reason is that these countries have much more to gain from economic nationalist policies than they lose politically from criticism. A vital premise, however, is that the economic systems of these countries are deeply dependent on natural resource industries (McNabb, 2023). We use natural resource rents (RRT) and their quadratic measures of how resource dependence affects the probability of an event. The results in Table 3 show that reliance on natural resource rents (excluding forest rents) increases the likelihood of resource nationalist policies in resource countries. This confirms hypothesis three, “Resource nationalist policies arise because of the dependence of the national economy of the resource country on natural resource wealth,” and that the selective benefits of implementing resource nationalism in the game at the international level have outweighed its potential adverse effects.

On the other hand, we analyze the impact of national economic growth on the likelihood of the event. Considering that the decision-making is based on the economic performance of the previous period, we use the first-order lag of the country’s real economic growth rate (rgdp). The results in Table 3 show that economic growth in resource countries promotes resource nationalist policies. This finding is consistent with the logic of the theoretical analysis of the article, which is that resource nationalism is not an emergency tool to save the national economy from recession. Instead, it is an act designed to generate excess profits from the national market for resource goods. The results of this analysis further support Hypothesis 3, which is proposed in this article. Because the economic system of resource countries is closely linked to the natural resource industry, the contraction of the global market for resource goods often leads to economic stagnation in resource countries. If an incident of resource nationalism occurs at this time, it will only accelerate the withdrawal of foreign investment and further deteriorate the economic and political situation within the resource country, which is not in line with the needs of the political game within the resource country. Therefore, resource nationalism can only occur in a scenario of excess profits in the global industrial system.

Resource nationalism is driven by “politico-economic” interactions

We analyze the theoretical mechanisms inherent in the emergence of resource nationalism and confirm, through quantitative analysis, the three basic assumptions made in the theoretical analysis in section 2. Politics and economy are two sides of the same coin, and there is a complex “politics-economy” connection and role behind the occurrence of resource nationalism. Therefore, based on the regression of the basic model, we further examine how the mechanism of economic operation and the mechanism of political game within the resource country interact. How this “political-economic” interaction triggers the emergence of resource nationalism through the game between interest groups. Table 4 illustrates the politico-economic mechanisms of resource nationalism. We interact a political party’s ruling philosophy with the change of the ruling party and the government’s administrative efficiency, respectively. Model 4 in Table 4 shows that left-wing parties are more inclined to introduce resource nationalism policies than right-wing parties when faced with a general election. This is also in line with the consistent political advocacy of left-wing parties. In addition, Model 5 shows that in an efficient government system, left-wing parties tend to act accordingly. In the face of the economic dividend brought about by the global increase in the price of resource goods, the political interest groups hope to strengthen the power of their parties by changing the distribution (Stroebel and van Benthem, 2013). In world political and economic history, left-wing economic beliefs have ranged from Keynesian economics and the welfare state to industrial democracy and social markets to nationalizing the economy and central planning. Left-wing groups advocate decisive government intervention in the economy and uphold the idea that the government should be directly involved in the day-to-day operations of the economy.

We also analyze how the economic philosophy of political groups drives their political behavior. Models 6 and 7 in Table 4 show that when faced with economic dividends from natural resource endowments, left-wing political groups tend to intervene in allocating resources through the government (van der Ploeg, 2023). However, when faced with national economic growth, left-wing and right-wing groups resort to resource nationalism. This suggests that political groups may briefly break away from party philosophy to gain game advantage in a political game driven by economic interests. The analysis of the “political-economic” mechanism (Interaction of political and economic elements) in the policy-making process of resource nationalism within the Ministry of Resources further supports the three hypotheses proposed in section 2. While political ideology guides national policymaking, the underlying economic drivers still shape the national policy process.

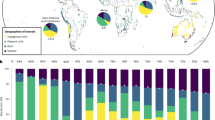

Heterogeneity in the distribution of resource nationalist events

The distribution of resource nationalism incidents is spatially and temporally uneven. According to the analysis of the mechanism of resource nationalism above, the heterogeneity of this distribution has some intrinsic correlation with the level of national development and the distribution of resource endowment. Based on the analysis of the theoretical assumptions and the inherent mechanism of “politics-economics,” we further examine the heterogeneity of the distribution of events constituted by the level of national development and geographic location. Based on the results of the quantitative analysis in the previous section, we calculate the probability of the occurrence of resource nationalism events in each country in each year and summarize the results according to the level of national development and geographic distribution, as shown in Fig. 2. The results show that countries with low national economic levels have more policy impulses to implement resource nationalism strategies than countries with high income. In addition, as the global demand for critical metals grows, the probability of resource nationalism strategies in low-income countries that dominate the supply chain for critical metals shows a significant upward trend.

Legend for A: yellow line for high-income countries, red line for low-income countries, green line for lower-middle-income countries, and blue line for upper-middle-income countries; legend for B: yellow line for Southeast Asian countries, red line for sub-Saharan countries, green line for Middle East & North Africa countries, and blue for Latin American & Colombian countries.

Geographically, Southeast Asia, South America, and Africa are areas of high incidence of resource nationalism (González et al. 2023). These regions are critical bulk minerals and critical metals producers and dominate the global market. These regions have a long record of government intervention in the functioning of the market economy due to the homogenization of economic structures, lagging economic development, and opaque government governance systems. With the structural changes in the global supply and demand pattern of mineral resources, the probability of resource nationalism in these regions remains at a high international level.

We further analyzed the effect of the type of natural resource on the probability of an incident of resource nationalism. Based on the resource endowment of each country, we examined the role of metallic minerals on resource nationalism. The results show that the type of metallic minerals does not bring about variability in the probability of resource nationalism. As shown in Fig. 3. A, the trend of probabilities for the five types of metallic minerals remains consistent. However, there is a more significant increase in the probability of clean energy metals, such as the rise in the likelihood of lithium, cobalt, and copper after 2008. However, when we turn to energy versus non-energy minerals, we can see an increase in the probability of non-energy minerals occurring. This difference was rapidly widened in the 2000–2012 metals Supercycle.

In addition, Figs. 2 and 3 demonstrate the evolutionary characteristics of the heat of resource nationalist events. We can see that resource nationalism events are somewhat consistent with the growth of the global economy, with a solid speculative character. Figures 2 and 3 show the probability of resource nationalism events falling off a cliff during the global economic recession caused by the financial crisis of 2008. During the global economic rebound after the financial crisis, a new wave of resource nationalism emerged with the help of the international metal market Supercycle. And after 2012, as the worldwide metal price trend retreated, the heat of resource nationalism then decreased. With the change in the structure of metal demand, some new features emerged in terms of spatial distribution.

Robust test

Change dataset

We propose an intrinsic mechanism of action for the generation of resource nationalism events, and to verify the robustness of the results of the article’s model fit, this section employs a change in the dataset to test the robustness of the results.

As noted earlier, the dataset contains countries where natural resource rents (excluding forest rents) account for more than 5% of GDP. A subset of these countries has not yet recorded incidents of resource nationalism. We intend to explore why, under the same conditions, a subset of resource countries have experienced economic nationalist behavior. To improve the robustness of the analysis of the results, we exclude from the dataset those countries that still need to record an incident. The results, as shown in Table 5, show that the significance of the main variables remains unchanged. At the same time, the variable execnat (whether the ruling party is characterized by nationalism) remains insignificant, suggesting that resource nationalist policy itself is an economically driven decision-making behavior.

Using machine learning to identify key factors influencing the occurrence of resource nationalism events

Machine learning has become an essential tool in econometrics research due to its excellent performance in prediction and classification studies (Valente, 2022). Not only can machine learning methods be combined with traditional econometric methods for causal inference to optimize their performance, but they can also be “data-driven” to consider a wide range of models systematically and comprehensively, which can lead to compelling counterfactual inference by improving predictive effectiveness (Chen, 2021). The explanatory variables in this paper are binary data, which are well-suited for machine learning applications. We use a machine learning approach to identify the key elements that influence the occurrence of resource nationalism events. The main variables used in machine learning are cross-sectional and time series data. When generating a machine learning model, it is standard procedure for records in the data to be assigned to modeling groups. Usually, the model randomly groups the data into training, testing, and validation groups. In this case, random means that every record in the dataset has an equal chance of being assigned to one of the three groups. When used for panel data analysis, leaving this out would result in the training, testing, and validation groups needing to be more independent, as the same country can be placed in all three groups simultaneously. This paper references Shad Griffin by processing the data to ensure that the training, testing, and validation groups are independentFootnote 1. By placing entities rather than records into the training, testing, and validation groups, independence between the groups can be ensured. We used XGBoost to analyze the significance of the impact of each variable on the target variable. Figure 4 shows that the metal price index, government efficiency, and real economic growth rate remain highly influential. On the contrary, right-wing parties remain less influential than left-wing parties. The machine learning results further confirm the robustness of the conclusions.

Metal.price: Metal Price Indexes; ROL: Rule of Law in World Governance Indicators; GE: Government Efficiency in World Governance Indicators; RRT: Natural resource rents as percent of GDP; lag(rgdp,1): Lagged period of real GDP growth (%); Ideology_left: Ruling party as a left-wing party; Ideology_right: The ruling party is a right-wing party; lag(ideology_c, -1): Lagged period of Change in ruling party; Polity: Democratization Index, NI National income level.

Discussion

Resource nationalism is not zero-sum competition in the national economic trading system

International trading businesses and resource companies often view resource nationalism as a threat to the global trading system. They perceive resource country governments as interfering with the normal functioning of the market economy and, by extension, harming the economic interests of business firms (Blunt and Sainkhuu, 2015). Through modeling arguments and empirical analysis, we confirm that resource nationalism is a game between resource countries and international resource companies over excess profits. Resource nationalism typically leads to the loss of some of the interests of multinational resource companies. Still, it ensures the average return of international capital investment under repeated games’ constraints. Under the global economic system, non-market behavior’s blow to average profitability in any country leads to the outflow of foreign capital (Rosales, 2018). Therefore, analyzing the consequences of implementing resource-nationalist policies should be a win-win situation. These non-market interventions undermine resource companies’ ability to profit from high global prices of resource goods. However, both sides still split the excess profits; only the proportion of the distribution has changed to some extent.

Our analysis suggests that international resource companies should take more proactive initiatives to deal with the non-market tactics employed by resource country governments (Lane and Kamp, 2013). Resource nationalists exacerbate the investment risks of international resource companies. In the face of potential resource nationalist behavior in resource countries, international resource companies should have enough strategic reserves to deal with possible interest games. Although the behavior of resource country governments is not in line with national free trade norms, a strategic equilibrium can still be reached through the game of interests. Resource nationalism after 2000 is more of a soft constraint, mainly through taxation and national shareholding, to fight for benefits, which provides more room for negotiation between the two sides of the game.

Resource nationalism is an effort by resource countries to seek interests from natural resource endowments

The analysis above confirms that the overdependence of the national economic system on natural resource wealth increases the probability that resource countries will introduce resource nationalism policies. While resource nationalism discourages foreign investment to some extent, these policies supplement the gaming gains of some domestic political groups. Resource nationalism can be seen as resource countries’ efforts to seek equity from mineral resource endowments (Cawood and Oshokoya, 2013). Such economic initiatives weaken international free trade norms to a certain extent, but they also increase the level of profitability for resource countries to a certain extent. Under the theory of comparative advantage, capital is allocated globally for production. Resource countries have assumed only the essential mineral supply production function due to capital, technology, and high-quality labor scarcity. Although the extraction and processing of mineral resources have, to a certain extent, promoted the economic development and social progress of resource countries, they have also brought about many social development problems and ecological and environmental problems (Aramendia et al. 2023; Gershenson et al. 2023). In the face of potential value-added benefits in metal manufacturing, there is a strong tendency for resource-rich countries to take control of the more profitable parts of the metal chain (Wilson, 2015). The rise of emerging economies and the new technological revolution have contributed significantly to the prosperity of the global mineral market. However, they have also stimulated long-standing economic nationalist tendencies within resource countries (Jacob and Pedersen, 2018). Resource country governments hope to break the existing global production pattern through administrative initiatives and increase the economic dividend of mineral wealth by keeping more high-value-added industrial segments in their countries. Resource countries’ initial intention to maximize their natural resource endowments is worthy of recognition. However, their approach poses a significant risk to international mineral capital (Hickey et al. 2020). It exacerbates the risks of the global mineral supply chain to a certain extent.

The imbalance of the global economic and trade system is the reason for resource nationalism

Developed countries such as Europe and the United States occupy the top of the global value chain through capital, technology, and international rules. China is also increasingly and steadily controlling the core of metal manufacturing. In contrast, many resource countries in Asia, Africa, and Latin America supply large quantities of cheap minerals at environmental and social costs. The economic systems of the resource countries are highly dependent on the extraction and processing of mineral resources, while their industrial chains have long been languishing at the low end of the chain. Under the dual role of economic dependence and industrial self-improvement, once the international market for resource products is in turmoil, resource nationalist behavior often occurs within the resource countries. Resource nationalism is ostensibly the non-market interventionist behavior of resource countries and their undermining of international trade norms. Still, they resist the unfair global economic and trading system.

A notable example is the massive environmental conflict in the Global South over extractive industries (Altamirano Rayo et al. 2024; Voskoboynik and Andreucci, 2022). “Resource nationalism” has been used by advocates of neoliberalism and open markets as a pejorative label to mute public discontent. The stigmatizing assertion somehow diminishes the concern about the rationality of resource nationalism (Cawood and Oshokoya, 2013).

Conclusion

We see increased power and sentiment of national resource interventions (IEA, 2023). Contingencies, geopolitics, and ideological conflicts, along with resource nationalism, constitute the current global supply challenges for critical metals. Both domestic and foreign influences influence the emergence of resource nationalism. We analyze the theoretical logic behind the emergence and development of resource nationalism using the theory of the “two-tier game” and propose three hypotheses for this article: (1) the global price increase of resource commodities is the main trigger for contemporary resource nationalist policies. (2) the domestic political game is the intrinsic driver of resource nationalist policies. (3) The reason for the emergence of resource nationalism lies in the dependence of resource countries’ economies on mineral resource wealth.

Based on the theoretical analysis, we comprehensively examine the resource nationalist behaviors of global resource countries since 1990 in combination with the long-term tracking reports of the United States Geological Survey (USGS). Using the occurrence of resource nationalism events as the dependent variable, we explore and analyze how the international resource market and the economic, social, and political environments of resource countries affect the probability of events. To improve the robustness of the empirical analysis, we creatively introduce a machine-learning algorithm to confirm the robustness of the results based on traditional robustness tests. We argue that the imbalance of the global economic and trade system is the reason for resource nationalism, and resource nationalism is the effort of resource countries to seek interests from mineral resource endowment; resource nationalism is not a zero-sum competition in the national economic and trade system. In the face of the potential risks posed by resource nationalism to the investment of multinational mining companies, the relevant interest groups should have sufficient strategic reserves to cope with the possible game of interests.

Data availability

The data and code have been provided in the appendix.

Notes

“Assigning Panel Data to Training, Testing and Validation Groups for Machine Learning Models” https://towardsdatascience.com/assigning-panel-data-to-training-testing-and-validation-groups-for-machine-learning-models-7017350ab86e.

References

Agneman G, Henriks S, Bäck H, Renström E (2024) On the nexus between material and ideological determinants of climate policy support. Ecol Econ 219:108119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2024.108119

Ali SH (2023) The US should get serious about mining critical minerals for clean energy. Nature 615:563–563. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-023-00790-y

Altamirano Rayo G, Mosinger ES, Thaler KM (2024) Statebuilding and indigenous rights implementation: Political incentives, social movement pressure, and autonomy policy in Central America. World Dev 175:106468. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2023.106468

Amedanou I, Laporte B (2024) Is the conventional wisdom on resource taxation correct? Mining evidence from African countries’ tax legislations. World Dev 176:106517. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2023.106517

Aramendia E, Brockway PE, Taylor PG, Norman J (2023) Global energy consumption of the mineral mining industry: Exploring the historical perspective and future pathways to 2060. Glob Environ Change 83:102745. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2023.102745

Arbucias D (2020) Resource nationalism and asymmetric bargaining power: a study of government-MNC strife in Venezuela and Tanzania. Cambridge Review of International Affairs. https://doi.org/10.1080/09557571.2020.1843404

Barlow A (2022) Piping away development: the material evolution of resource nationalism in Mtwara, Tanzania. J South Afr Stud. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057070.2022.2028486

Berrios R, Marak A, Morgenstern S (2011) Explaining hydrocarbon nationalization in Latin America: Economics and political ideology. Rev Int Political Econ 18:673–697

Blunt P, Sainkhuu G (2015) Serendipity and stealth, resistance and retribution: Policy development in the Mongolian mining sector. Prog Dev Stud 15:371–385. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464993415592763

Bremmer I, Johnston R (2009) The rise and fall of resource nationalism. Survival 51:149–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/00396330902860884

Cawood F, Oshokoya O (2013) Considerations for the resource nationalism debate: a plausible way forward for mining taxation in South Africa. J South Afr Inst Min Metall 113:53–59

Cawood FT, Oshokoya OP (2013) Resource nationalism in the South African mineral sector: Sanity through stability. J South Afr Inst Min Metall 113:45–52

Chen JM (2021) An introduction to machine learning for panel data. Int Adv Econ Res 27:1–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11294-021-09815-6

Chen W, Wang P, Meng F, Pehlken A, Wang Q-C, Chen W-Q (2024) Reshaping heavy rare earth supply chains amidst China’s stringent environmental regulations. Fundamental Research. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fmre.2023.11.019

Childs J (2016) Geography and resource nationalism: A critical review and reframing. Extract Ind Soc 3:539–546. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2016.02.006

Ciacci L, Fishman T, Elshkaki A, Graedel TE, Vassura I, Passarini F (2020) Exploring future copper demand, recycling and associated greenhouse gas emissions in the EU-28. Glob Environ Change 63:102093. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2020.102093

Click RW, Weiner RJ (2010) Resource nationalism meets the market: Political risk and the value of petroleum reserves. J Int Bus Stud 41:783–803. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2009.90

Cotula L (2020) (Dis)integration in global resource governance: extractivism, human rights, and investment treaties. J Int Econ Law 23:431–454. https://doi.org/10.1093/jiel/jgaa003

De Graaff N (2011) A global energy network? The expansion and integration of non-triad national oil companies. Glob Netw 11:262–283. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0374.2011.00320.x

Dou S, Xu D, Zhu Y, Keenan R (2023) Critical mineral sustainable supply: Challenges and governance. Futures 146:103101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2023.103101

Epstein D, O’Halloran S (1999) Delegating Powers: A Transaction Cost Politics Approach to Policy Making under Separate Powers, Political Economy of Institutions and Decisions. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511609312

Ernst & Young (2013) Business risks facing mining and metals 2013–2014 (No. ER007). Global Mining & Metals Center, London: UK

Evans PB, Jacobson HK, Putnam RD (1993) Double-Edged Diplomacy: International Bargaining and Domestic Politics, 1st ed. University of California Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/jj.2711566

Fattouh B, Darbouche H (2010) North African oil and foreign investment in changing market conditions. Energy Policy 38:1119–1129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2009.10.064

Fontaine G, Fuentes J, Narvaez I (2019) Policy mixes against oil dependence: Resource nationalism, layering and contradictions in Ecuador’s energy transition. Energy Res Soc Sci 47:56–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2018.08.013

Fontaine G, Narvaez I, Velasco S (2018) Explaining a policy paradigm shift: a comparison of resource nationalism in Bolivia and Peru. J Comp Policy Anal 20:142–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/13876988.2016.1272234

Frederiksen T (2023) Subjectivity and space on extractive frontiers: Materiality, accumulation and politics. Geoforum 103915. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2023.103915

Furstenberg S, Moldalieva J (2022) Critical reflection on the extractive industries transparency initiative in Kyrgyzstan. World Dev 154:105880. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2022.105880

Ganbold M, Ali S (2017) The peril and promise of resource nationalism: A case analysis of Mongolia’s mining development. Resour Policy 53:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2017.05.006

Gershenson C, Jin O, Haas J, Desmond M (2023) Fracking evictions: Housing instability in a fossil fuel boomtown. Soc Nat Resour 0:1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2023.2286640

González A, Sánchez F, Castillo E, (2023) The nationalization of the large-scale copper mines in Chile: successful investment or financial failure? Miner Econ. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13563-023-00412-z

Grossman GM, Helpman E (1994) Endogenous innovation in the theory of growth. J Econ Perspect 8:23–44. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.8.1.23

Grossman GM, Helpman E (1994) Protection for sale. Am Econ Rev 84:833–850

Gygli S, Haelg F, Potrafke N, Sturm J-E (2019) The KOF Globalisation Index – revisited. Rev Int Organ 14:543–574. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-019-09344-2

Hancock L, Ralph N, Ali S (2018) Bolivia’s lithium frontier: Can public private partnerships deliver a minerals boom for sustainable development? J Clean Prod 178:551–560. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.12.264

Hellinger D (2016) Resource nationalism and the Bolivarian revolution in Venezuela, in: The Political Economy of Natural Resources and Development. Routledge

Hickey S, Abdulai A, Izama A, Mohan G (2020) Responding to the commodity boom with varieties of resource nationalism: a political economy explanation for the different routes taken by Africa’s new oil producers. Extract Ind 7:1246–1256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2020.06.021

Huber M (2019) Resource geography II: What makes resources political? Prog Hum Geogr 43:553–564. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132518768604

IEA (2022) Critical Minerals Policy Tracker, IEA (International Energy Agency), https://www.iea.org/reports/critical-minerals-policy-tracker

IEA (2023) Critical Minerals Market Review 2023. https://www.iea.org/reports/critical-minerals-market-review-2023

Jacob T, Pedersen RH (2018) New resource nationalism? Continuity and change in Tanzania’s extractive industries. Extract Ind Soc 5:287–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2018.02.001

James A, Rivera NM (2021) Oil, politics, and “Corrupt Bastards.” J Environ Econ Manag 102599. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeem.2021.102599

Jin B, Zhang Q (Eds.) (2022) The New Trend of Global Industrial Division of Labor and China’s Responses, Research Series on the Chinese Dream and China’s Development Path. Springer Nature, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-5674-4

Kahn M (2013) Natural resources, nationalism, and nationalization. J South Afr Inst Min Metall 113:03–09

Kalyuzhnova Y, Nygaard C (2009) Resource nationalism and credit growth in FSU countries. Energy Policy 37:4700–4710. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2009.06.024

Kaup BZ, Gellert PK (2017) Cycles of resource nationalism: Hegemonic struggle and the incorporation of Bolivia and Indonesia. Int J Comp Sociol 58:275–303. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020715217714298

Kilambo SR (2023) Black peoples’ control of South Africa’s mining industry in the post-apartheid South Africa. Extract Ind Soc 14:101267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2023.101267

Koch N, Perreault T (2019) Resource nationalism. Prog Hum Geogr 43:611–631. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132518781497

Kohl B, Farthing L (2012) Material constraints to popular imaginaries: The extractive economy and resource nationalism in Bolivia. Polit Geogr 31:225–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2012.03.002

Kretzschmar G, Kirchner A, Sharifzyanova L (2010) Resource nationalism - limits to foreign direct investment. Energy J 31:27–52

Laing AF (2020) Re-producing territory: Between resource nationalism and indigenous self-determination in Bolivia. Geoforum 108:28–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.11.015

Lane A, Kamp R (2013) Navigating above-the-ground risk in the platinum sector. J South Afr Inst Min Metall 113:163–170

Lange S, Kinyondo A (2016) Resource nationalism and local content in Tanzania: Experiences from mining and consequences for the petroleum sector. Extract Ind Soc 3:1095–1104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2016.09.006

Li W, Adachi T (2017) Quantitative estimation of resource nationalism by binary choice logit model for panel data. Resour Policy 53:247–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2017.07.002

Liu S-L, Fan H-R, Liu X, Meng J, Butcher AR, Yann L, Yang K-F, Li X-C (2023) Global rare earth elements projects: New developments and supply chains. Ore Geol Rev 157:105428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oregeorev.2023.105428

Marston A (2019) Strata of the state: Resource nationalism and vertical territory in Bolivia. Polit Geog 74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2019.102040

Materka E (2011) End of transition? Expropriation, resource nationalism, fuzzy research, and corruption of environmental institutions in the making of the shale gas revolution in Northern Poland. Debatte: J Contemp Cent East Eur 19:599–631. https://doi.org/10.1080/0965156X.2012.681919

McNabb K (2023) Fiscal dependence on extractive revenues: Measurement and concepts. Resour Policy 86:104129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2023.104129

McNulty BA, Jowitt SM (2022) Byproduct critical metal supply and demand and implications for the energy transition: A case study of tellurium supply and CdTe PV demand. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 168:112838. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2022.112838

Mommer B, Araque AR (2002) Global Oil and the Nation State

Myadar O, Jackson S (2019) Contradictions of populism and resource extraction: Examining the intersection of resource nationalism and accumulation by dispossession in Mongolia. Ann Am Assoc Geogr 109:361–370. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2018.1500233

Nassar NT, Brainard J, Gulley A, Manley R, Matos G, Lederer G, Bird LR, Pineault D, Alonso E, Gambogi J, Fortier SM (2020) Evaluating the mineral commodity supply risk of the U.S. manufacturing sector. Sci Adv 6:eaay8647. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aay8647

Ng’ambi SP (2018) Mineral Taxation and Resource Nationalism in Zambia (SSRN Scholarly Paper No. 3246208). Social Science Research Network, Rochester, NY. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3246208

Nie M (2003) Drivers of natural resource-based political conflict. Policy Sci 36:307–341. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:OLIC.0000017484.35981.b6

Obaya M, (2021) The evolution of resource nationalism: The case of Bolivian lithium. Extract Ind Soc 8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2021.100932

Osman A, Owusu MT, Anu SK, Essandoh S, Aboansi J, Abdullai D (2022) Ban on artisanal mining in Ghana: Assessment of wellbeing, party affiliation and voting pattern of miners in Daboase, Western Region. Resour Policy 79:103023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2022.103023

Ostensson O (2019) Promoting downstream processing: resource nationalism or industrial policy? Miner Econ 32:205–212. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13563-019-00170-x

Ostrowski W (2023) The twilight of resource nationalism: From cyclicality to singularity? Resour Policy 83:103599. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2023.103599

Paul AH, Pablo H (2016) The Political Economy of Natural Resources and Development: From Neoliberalism to Resource Nationalism. Routledge

Pedersen R, Jacob T, Bofin P (2020) From moderate to radical resource nationalism in the boom era: Pockets of effectiveness under stress in “new oil” Tanzania. Extract Ind Soc- Int J 7:1211–1218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2020.03.014

Pedersen R, Mutagwaba W, Jonsson J, Schoneveld G, Jacob T, Chacha M, Weng X, Njau M (2019) Mining-sector dynamics in an era of resurgent resource nationalism: Changing relations between large-scale mining and artisanal and small-scale mining in Tanzania. Resour Policy 62:339–346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2019.04.009

Poncian J (2019) Galvanising political support through resource nationalism: A case of Tanzania’s 2017 extractive sector reforms. Politic Geogr 69:77–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2018.12.013

Prather L (2024) Ideology at the water’s edge: explaining variation in public support for foreign aid. World Dev 176:106472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2023.106472

Prior T, Giurco D, Mudd G, Mason L, Behrisch J (2012) Resource depletion, peak minerals and the implications for sustainable resource management. Glob Environ Change Glob Transform, Soc Metab Dyn socio-Environ Confl 22:577–587. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.08.009

Pryke S (2017) Explaining resource nationalism. Glob Policy 8:474–482. https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.12503

Putnam RD (1988) Diplomacy and domestic politics: the logic of two-level games. Int Organ 42:427–460. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818300027697

Riofrancos T (2023) The Security–Sustainability Nexus: Lithium onshoring in the Global North. Glob Environ Polit 23:20–41. https://doi.org/10.1162/glep_a_00668

Rosales A (2018) Pursuing foreign investment for nationalist goals: Venezuela’s hybrid resource nationalism. Bus Polit 20:438–464. https://doi.org/10.1017/bap.2018.6

Sarsenbayev K (2011) Kazakhstan petroleum industry 2008-2010: trends of resource nationalism policy? J World Energy Law Bus 4:369–379. https://doi.org/10.1093/jwelb/jwr017

Savoia A, Sen K (2021) The political economy of the resource curse: A development perspective. Annu Rev Resour Econ 13:203–223. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-resource-100820-092612

Stephen PM, William AB, Leslie Y (1989) Black Hole Tariffs and Endogenous Policy Theory: Political Economy in General Equilibrium. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Stevens P (2008) National oil companies and international oil companies in the Middle East: Under the shadow of government and the resource nationalism cycle. J World Energy Law Bus 1:5–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/jwelb/jwn004

Stroebel J, van Benthem A (2013) Resource extraction contracts under threat of expropriation: theory and evidence. Rev Econ Stat 95:1622–1639. https://doi.org/10.1162/REST_a_00333

USGS (2020) International geoscience collaboration to support critical mineral discovery (USGS Numbered Series No. 2020–3035), International geoscience collaboration to support critical mineral discovery, Fact Sheet. U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, VA. https://doi.org/10.3133/fs20203035

Valente, M (2022) Policy evaluation of waste pricing programs using heterogeneous causal effect estimation. J Environ Econ Manag 102755. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeem.2022.102755

van der Ploeg, F (2023) Benefits of rent sharing in dynamic resource games. Dyn Games Appl 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13235-023-00528-5

van Krevel C, Peters M (2024) How natural resource rents, exports, and government resource revenues determine Genuine Savings: Causal evidence from oil, gas, and coal. World Dev 181:106657. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2024.106657

Vivoda V (2023) Friend-shoring and critical minerals: Exploring the role of the Minerals Security Partnership. Energy Res Soc Sci 100:103085. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2023.103085

Voskoboynik DM, Andreucci D (2022) Greening extractivism: Environmental discourses and resource governance in the ‘Lithium Triangle. Environ Plan E: Nat Space 5:787–809. https://doi.org/10.1177/25148486211006345

Wang X, Kunwang L, Shenxiang H (2011) How trade policy is made: a model of endogenous protection including political contributions, campaign support and delegation of power. J World Econ 34:107–126

Warburton E (2017) Resource nationalism in Indonesia: Ownership structures and sectoral variation in mining and palm oil. J East Asian Stud 17:284–311. https://doi.org/10.1017/jea.2017.13

Wilson JD (2015) Understanding resource nationalism: economic dynamics and political institutions. Contemp Polit 21:399–416. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569775.2015.1013293

Acknowledgements

This study is supported by the Major Program of the National Fund of Philosophy and Social Science of China (21&ZD106).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed conceptually, formally, and in the original draft. Deyi Xu: Theory analysis; supervision; writing—review and editing. Shiquan Dou: conceptualization; formal analysis; methodology; writing—original draft preparation. Yongguang Zhu: supervision; writing—review and editing, validation; conceptualization. Jinhua Cheng: grammatical revision, theoretical analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Not obtained –because the research does not involve human participants or their data.

Informed consent

Not obtained –because the research does not involve human participants or their data.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions