Abstract

Amid a patent boom and increase in patent infringement cases, China is a fast-growing catch-up country in the intellectual property (IP) regime, with arguments on effectiveness and standardization. In 2014, China installed three intellectual property courts (IPCs) in Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou. This reform represents a crucial step in a series of reforms and actions that seek to establish a uniform and standardized judicial IP regime in China. Based on interviews, statistical reports, and an analysis of judicial documents, this study argues that the interpretation and execution of IP law vary across the three locations due to the embeddedness of those courts and their judges in the regions. Indications that the regional setting and presence of international firms affect the efficient proceedings of IP tribunals and courts were found as a result. Given that IP law is the same all over a country, it can be concluded that courts balance national regulation and regional realities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

While the number of patents and infringement cases in China has increased rapidly over the past 40 years, some researchers have argued that China’s intellectual property (IP) protection promotes local protectionism because of imbalances in the IP jurisdiction (PWC 2011). Some researchers see China’s IP protections as inadequate, with inconsistent regional adjudication standards and insufficient enforcement (European Commission 2021). Studies with similar perspectives have argued that issues, such as inconsistent IP regime standards and regional imbalances, affect how foreign companies or investors cooperate with China (Man 2013; Love et al. 2015; Graneris 2019). However, China’s IP regime and patent protection laws only date back to the 1980s, which is approximately 40 years ago. Thus, it is often argued that the Chinese IP regime is still in the developmental stage of finding a balance between the international standards of IP protection and local needs and enforcement practices (Bai et al. 2006). Chinese regulations have increasingly adapted international IP protection positions and implemented new procedures to support their enforcement. Meanwhile, China’s economy shifted from an extended workbench of Western economies to one that competes based on cost advantages and human and intellectual capital (Liu 2020). Thus, Chinese firms are increasingly interested in protecting their intellectual property.

Simultaneously, the country consists of very distinct regions that differ in their human capital composition and economic basis, while the IP law is the same. In this research, we argue that there is a balance between a judicial system and the surrounding socio-economic system and context. Concretely, we argue that the efficiency of organizations that solve IP disputes, such as specialized IP courts or IP chambers, depends on the system’s adjustment to the surrounding regional context of such organizations. In this context, efficiency is associated with the speed and quality of dispute settlement. Thus, attempts to increase efficiency involve improving mechanisms for diversified disputes and refining mechanisms for handling complex and simple cases (Li 2018). These initiatives aim to prevent procedural repetitions, expedite judicial operations, and minimize case delays.

China is an ideal case to study such balances and misbalances because China underwent various reforms of its IP regime, which started with establishing IP protection laws in the 1980s. In general, the development and transformation of such regimes are connected with multiple challenges and problems (Ma 2019). These include a large-scale expansion to form non-exclusive jurisdictions, inconsistent judgment standards, and long litigation durations. Therefore, this study considers the IP regime specialization and regional context to explore the latest adjustment of the IP regime and its fit to the regional context of three different Chinese regions. Concretely, we study the introduction of intellectual property courts (IPCs) in Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou. These are pioneering regions in economic terms and the introduction and execution of various political reforms, such as the IP reform. A high proportion of IP cases are settled in these regions (European Commission 2021).

This paper is organized as follows. In the next section, we present our research framework, followed by a description of the IP reforms in China in part three and our methodology in part four. The following results section presents our findings, and in part six, we summarise our results and discussions.

Research frameworks

Institutions are shaped by their specific contexts (Glückler and Lenz 2016), and identical social activities can manifest differently across the varied regional contexts within a country (Barley 1990). While institutions are typically not seen as organizations, courts are particular cases closely associated with institutions, as defined by Bathelt and Glückler (2014), because they are social solutions for the settlement of legal disputes and sanction misbehavior if the legal expectations are not appropriately faced. Similarly, IP law and judicial reform are important components of IP management (Acemoglu et al. 2001). The formal regulation of IP laws and legal systems undergo continuous reforms. While improvements in the IP regime system positively impact domestic innovation (Huang 2017), not all regulations are effective or can be enforced as equally as expected. There are systematic disparities in legal systems across different regions (Fan et al. 2013).

Individuals and organizations follow existing institutions to engage in social interaction and create new institutions, such as firms’ strategic behavior, which is also impacted by regulations and, in turn, influences regulation (DiMaggio and Powell 1983; Tolbert et al. 2011). Similarly, the organizations of a judicial system adapt to existing institutions and form them. Therefore, examining regulations alone is insufficient for understanding the foundation of social behavior and economic development (Bathelt and Glückler 2014). Judicial activities in China involve diverse actors and judicial organizations, such as the State Intellectual Property Office (SIPO) IP chamber and specialized courts that enforce IP protection law. Research on the Chinese IP regime showed that the context in which Chinese judges operate is marked by deep embeddedness in administrative, political, social, and economic contexts, necessitating a multitude of external factors (Ng and He 2017). Judicial proceedings typically involve actors from different cultural and political backgrounds; thus, courts and judges need to accommodate various interests and priorities (Gillespie 2010; Xu 2020). In this sense, judges and courts have to moderate between the reality in the regional context and general law.

In contrast, firms that own patents and require judicial means to protect their technology and compete with their competitors adjust to rules and judicial procedures. Local and non-local firms embedded in different regional contexts form diverse informal cultures and regulations, affecting how they interact with the formal IP system (Huang et al. 2017). For example, research on firm commercial law suggests that a company’s context, especially its political or cultural background, plays a role in litigation (Xu 2020). While the Chinese patent law reforms have attempted to meet international standards, foreign companies are more sensitive to changes in formal IP regulations (Branstetter et al. 2006). Furthermore, foreign companies usually benefit from a mature IP legal system in their home countries and more practical knowledge and skills in IP protection. However, they have little understanding of local resources and relationships, making it difficult for them to integrate into the local informal networks and procedures that informally settle disputes. Conversely, a judicial regime that repeatedly addresses foreign firms and their specific legal issue adapts to these requirements by establishing specialized practices.

Our research focuses on variations in the IP judicial-related organizations, such as the Intellectual Property Court, and their regional contexts. We consider the presence of foreign firms and local economic and technological innovation conditions to be the main components of the regional context. Therefore, we employ a research framework that considers the reform of IPCs in 2014 to determine which configurations lead to an efficient balance between an organizational solution of an IP regime and its regional context. Based on existing research and given consideration of regional contextual differences, we end up with our research question:

What are the specific contextual conditions under which intellectual property courts efficiently resolve intellectual property disputes?

Reforms, patent boom, and regional differences

In 1978, Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping advocated for the reform and opening-up policy, along with the ‘Four Modernisations’ of science and technology. Accompanied by increased international trade, these reforms led to a surge in Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) entering the Chinese market. Simultaneously, Chinese firms increased their presence in different international markets. Consequently, local private firms and state-owned enterprises (SOEs) were also restructured, and their intellectual property portfolio developed that needed IP protection.

While China transitioned to a market economy, it underwent continuous reforms in IP regulation. Over the past three decades, China’s IP law system, including the Patent Law, has been amended four times. Before China’s reform and opening up, IP regime models and concepts were not recognized (Ma 2019); there was no genuine patent system, only a reward system for invention and technological improvement (Cui 2010). As a result, the reform and opening-up policies signify the development of China’s IP awareness and governance, confessing achievements in private ownership (Huang 2017).

Although there was a significant gap between the autonomy of Chinese enterprises in the early 1980s and market requirements at the time, the initial stage of development saw a convergence between the need for autonomy and exclusivity provided by patents. After 2001, as competition and cooperation between China and the global economy intensified, reforms of China’s IP laws were undertaken to align with international standards, aiding China’s participation in international trade and cooperation more effectively. During 1993–2013, a specialized IP chamber was established within the Beijing Intermediate People’s Court, followed by similar establishments in Shanghai and Guangdong’s intermediate and higher people’s courts (Ma 2019; Li 2018). China’s Supreme People’s Court also set up chambers in 87 Intermediate People’s Courts and 7 Basic People’s Courts specifically for first-instance patent litigation cases. Although this patent court system initially met China’s needs for handling patent cases, the distribution of first- and second-instance cases was widespread, leading to inconsistencies in trial standards.

However, the surge in patent applications and infringement cases from 2008 to 2019 necessitated a more efficient response to the varied demands. This led to the third and fourth amendments of China’s patent law, which addressed new types of patent disputes. Furthermore, the third and fourth reforms were mainly designed to meet the needs of more companies to protect their patents and the country’s technological innovation strategy (Yang and Yen 2010; Huang et al. 2017).

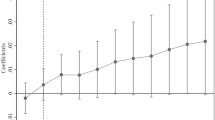

Since the implementation of the Chinese Patent Law in April 1985, the number of patents in China has increased rapidly. The cumulative number of patent applications for inventions, utility models, and designs reached its first million by 2000. From 1990–2019, the number of authorized patents in China rose from 225,880 to 2,591,607 (Fig. 1). Accompanying the increase in patents, the incidence of patent infringement cases also grew. In 2020, the Supreme People’s Court of China received 3470 new IP civil cases and resolved 3260 cases, representing increases of 38.58% and 64.98%, respectively, compared to 2019.

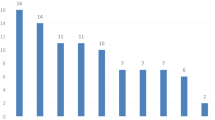

Moreover, people’s courts across China handled 443,326 first-instance civil IP cases. They concluded 442,722 cases during the same period, marking increases of 11.10% and 12.22% over the previous year, according to the China IP White Book (2020). It demonstrates an increasing demand for foreign and Chinese firms to solve and settle IP disputes. To cope with the growing interests of national and international firms in establishing a functioning judicial system that enforces intellectual property law efficiently, China introduced specialized IPCs in 2014 in Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou. Before this reform, IP cases were typically managed by normal courts with different chambers and tribunals (Fig. 2). The so-called ‘Three in One’ IP tribunals have been established and seceded by the mentioned specialized IPCs as an intermediate step. This reform led to a simplified and flattened management of these intellectual property courts, forming a judge-led, personnel-classified, collaborative trial model. For instance, a system of technical investigators was established to create replicable and generalizable reformed trials. To realize interregional jurisdictions, exclusive IP tribunals with interregional jurisdictions were established in different provinces or cities.

Although judicial reforms might be easily planned and documented, their implementation often deviates from such plans. Uneven economic development across regions has resulted in disparities in regime capabilities. IP infringement cases in China predominantly occur in economically developed areas, such as Guangdong, Beijing, Shanghai, Jiangsu, and Zhejiang, and are infrequent in less economically developed regions (OECD 2020). A key issue arises from the disparate judgments on similar cases, primarily attributed to variations in judges’ fact-finding approaches and legal interpretations. In 2016, in China’s four-tier court system, about 224 intermediate courts and 167 basic courts had jurisdiction over intellectual property cases (Supreme People’s Court of China 2017). There are over 5000 intellectual property judges, assistant judges, technical investigators, and court clerks (Supreme People’s Court of China 2017). From 2017 to 2019, the Supreme People’s Court of China approved the establishment of more than 20 specialized intellectual property chambers (European Commission 2021) in 17 provincial-level administrative regions. By 2019, China’s Supreme People’s Court established a specialized intellectual property court to handle second-instance civil and administrative cases. This leads to our first empirical task: reconstructing the organizational setting and regional differences of IP litigation during IP court reform.

Overall, IP cases in China are concentrated in Guangdong, Beijing, Shanghai, Jiangsu, and Zhejiang and rarely occur in peripheral economic regions. For example, Guangdong Province received 44,000 new first-instance IP civil cases in 2016, whereas Gansu Province received only 246 cases in the same year (Ma 2019). Some researchers identify significant differences in the quality of IP legal systems across different regions (Huang et al. 2017). In economically peripheral regions, such as Guizhou, Qinghai, and Yunnan, the effectiveness of IP protection is insufficient, and the enforcement of the legal IP system is relatively weak (Fan et al. 2013). The quality of IP protection is more effective in cities such as Beijing, Shanghai, and the coastal regions (World Bank 2008).

The role of intellectual property courts and specialized judicial systems is closely linked to the specific regional context. Our study focuses on Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou, which are among China’s most economically developed first-tier cities and are embedded within the country’s largest urban clusters: the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei, Yangtze River Delta, and Pearl River Delta regions, respectively. As pioneering areas for intellectual property rights reform in China, these regions host the earliest three IPCs. Despite being highly developed, there are notable differences in regional contexts and urban functions (see Supplementary Appendix 1).

As China’s capital, Beijing is a key political and cultural center, serving as the core for formulating national policies and plans. It is home to many large central SOEs and headquarters of state-owned enterprises, concentrating approximately 71% of these headquarters according to the 2023 directory released by the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC). Shanghai, one of China’s directly controlled municipalities, functions as an international hub for economics, finance, trade, shipping, and technological innovation. It boasts a higher proportion of FDI enterprises, marking its status as an international megacity. Furthermore, international trade is a crucial component of Shanghai’s economic development, with higher export value and more FDI firms, enhancing the city’s international openness and providing opportunities for alignment with international IP standards through international trade integration. The Guangdong province, with Guangzhou at its core, was among the earliest pioneer regions in China’s reform and opening-up policy. Characterized by rapid private economic development, it is also a hub for Chinese original equipment manufacturer (OEM) enterprises, leading other regions in per capita GDP. The private economy’s dominance over FDI and state-owned enterprises grants the region greater flexibility in industrial economic development.

Methods

Data collection

We collected quantitative and qualitative data. The qualitative analysis is based on 11 interviews (Table 1), providing perspectives from IP judges, prosecutors, lawyers, managers of IP service companies, and IP researchers, contributing valuable insights. Interviews were conducted through various methods, including face-to-face interactions, phone calls, and group discussions, with 15–60 min each. These interviews focused on the processes of the IP regime, its impacts, the evolution of judicial and organizational reforms, and the strategies firms employ to handle infringement cases. These empirical conversations offer insights into the complexities of IP regulations, organizations, and institutions, enhancing our understanding of the patterns contributing to developing regional IP regimes and their importance.

Inspired by Zipf et al. (2023), we used judicial document data for a deeper analysis. We get the judgment documentary data of 2010–2020 from China Judgement Online. These documents include information about the trial, such as the court name, address, names of the plaintiff and defendant, judges, process of the judgment, etc. Focusing only on invention infringement cases, we screened all the cases based in China. We used the cases in Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou IPCs’ trials as the primary research objects.

Furthermore, we processed the data and eliminated cases with incomplete information, which helped us to calculate the number of judges, growth rates, verdicts, and attributes of the companies involved in different regions. The Top 50 intellectual property rights cases released by China’s Supreme People’s Court annually are considered to be typical and exemplary cases. We identified the cases in Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou, which are rated as the Top 50 cases from 2010 to 2020, and integrated them into our analysis. We also obtained data related to the regional setting, such as the number of patents in the city, GDP per capita, and proportion of local and FDI firms from the National Bureau of Statistics of China (NBSC) ‘s ‘Statistical Yearbook of Chinese Cities (2010–2020)’ as well as from the statistical yearbooks of the selected cities, and they were used to demonstrate the differences of the regional contexts.

Admitting the challenge of evaluating judicial effectiveness solely through indicators, we acknowledge that achieving efficient justice demands a delicate equilibrium between speed and quality. This balance is especially critical for individuals directly engaged in a specific court case (Voigt 2016). An efficient judiciary refers to utilizing as few judicial resources as possible to achieve as many judicial outcomes as possible. Thus, we used judicial data to construct two dependent variables: the average duration of the judicial process (Y1) and the number of demonstration cases of a region for each year (Y2). Y1 is the average number of trial days for patent infringement cases, and the trial data were drawn from China Judgements Online, which includes trial details of IP infringement cases in China. We calculated the duration of each patent infringement case and the average trial duration. Y2 is the number of China’s Top 50 IP cases from the Supreme People’s Court of China, and the Top 50 cases exhibit exemplary effects.

The statistical metrics include six independent variables that reflect IP specialization (X1), regional firm context (X2 and X3), local economic condition (X4), tech-innovation condition (X5), and information dissemination condition (X6). The variables are mainly gathered from the China City Statistical Yearbook (2011–2020), the China Statistical Yearbook on Science and Technology (2011–2020), and the China National Intellectual Property Administration.

Analytical procedures

We combined the interviewees’ evaluations of IP system reforms with the history of IP reforms in China, focusing primarily on those involved in IP-related work for a long time. They have witnessed the development of IP reform in China from non-existence to existence, from state domination to gradual marketization with the restructuring of enterprises. We focus on how they experience and feel the differences in these reforms and how they perceive the variations in different regional contexts.

These statistics reflect the impact of regulation changes on the growth of court system resources and show how the IPCs balance their regime in specific regional contexts. We used qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) to analyze the judicial documents. This method helps us explore concurrent relationships between conditions and identify different causal paths (Meyer et al. 1993). QCA can identify which conditions or combinations are sufficient or necessary for a particular outcome. It is a set-theoretic method to determine which conditions are sufficient (necessary) to produce a specific result. It provides an alternative to a linear regression analysis (Fainshmidt et al. 2020). QCA combines the advantages of qualitative and quantitative analyses, addressing concerns about the ‘generalizability’ of a qualitative analysis with a small number of cases. It also compensates for the limitations of a large-sample analysis in capturing qualitative variations and analyzing phenomena. Unlike traditional regression methods, QCA uses Boolean algebra, thus avoiding omitted variable bias (Ragin 2009).

A traditional quantitative statistical analysis based on linear causality is connected with shortcomings in providing valid analytical conclusions with limited observations. Furthermore, it is worth noting that the difference between fuzzy-set QCA (fsQCA) and a traditional regression model is that the analysis does not follow a simple logic of how high or low an independent or dependent variable is. Instead, qualitative comparative analyses are designed to construct causal relationships of research questions from small data samples through a continuous dialogue between empirical data and relevant theories, literature, and interview materials (Legewie 2013; Covin et al. 2016; Li et al. 2021).

We used the specific form of fsQCA. A fsQCA typically assumes a spectrum of possible values (Fainshmidt et al. 2020). It encompasses the category and degree of datasets that fit our databases. This approach seeks to unveil the minimum conditions (combinations) leading to specific outcomes in particular situations, proving well-suited for analyzing multiple interrelated causal relationships (Vis 2012). fsQCA requires data calibration, and researchers utilizing their expertise to achieve meaningful calibration have some advantages (Ragin 2009). In this study, we applied fsQCA. When a condition or combination of conditions (X) is sufficient for (Y), the occurrence of influential mode(s) is always accompanied by IP litigation. The sufficiency of a combination of modes for observing IP litigation is demonstrated if membership scores in the proposed combination of modes are consistently less than or equal to membership in the IP litigation.

Consistency ‘indicates how closely a perfect subset relation is approximated’ (Ragin 2009). For sufficiency, consistency was calculated as (Ragin 2006):

Where Yi represents effective IP litigation, Xi represents the conditions for effective IP litigation, and is a binary condition. In particular, effective IP litigation consists of two Y-variables: ‘Short trial duration (Y1)’ is calculated by average trial days, and ‘Demonstrating (Y2)’ involves selecting cases from the top 50, specifically focusing on first-instance cases.

Considering the years before the establishment of the IPC (=0), years after the establishment of the IPC (=1), and the time lag from the establishment of the IPC to the trial of cases, assignment 1 started in 2016 since China’s IPC was established at the end of 2014. X2 represents firms affected by government institutions and demonstrates the share of local firms with state assets from 2012 to 2019. X3 represents the firms affected by foreign institutions, as illustrated in the share of FDI enterprises. X4 to X6 denote the local base condition, in which X4 indicates the economic condition illustrated by regional GDP/capita, and X5 indicates the technology innovation condition illustrated by the number of patents.

Given the fact that the majority of our variables are continuous, we transformed them into categories to make them applicable to a set analysis, which forms the basis of fsQCA. For all continuous variables, we created four classes that distinguish between lower and higher values (see Table 2). Our results show how the different categories affect a dependent variable. For example, a moderate variable value can be part of a solution that reduces the average trial duration, while higher or lower values and categories do not affect this issue.

Results

Embedding in specific regional settings

Establishing a specialized IPC aims to enhance the professionalism of litigation proceedings and promote consistency across regional processes. Despite this, the number of cases accepted by the different IPCs varies across the different regions. Before the IPC reform in 2014, Shanghai and Beijing Intermediate Courts saw a higher volume of intellectual property cases. These numbers increased until 2018. However, the strongest increase is observed in Guangzhou. Previously, intellectual property cases in Guangzhou were distributed among intermediate courts in various cities. With the establishment of the Guangzhou IPC, cases from Guangzhou Province (excluding Shenzhen) were centralized under its jurisdiction, leading to a rapid increase in case numbers (Fig. 3). Thus, the IPC serves an inter-regional centralizing function, streamlining the handling of intellectual property cases.

A comparison between Figs. 3 and 4 shows that the number of cases and judges has been increasing since the establishment of the IPCs in 2014 in China and the three regions being studied. Specifically, Beijing and Guangzhou showed a significantly stronger increase, whereas the growth in Shanghai mirrored the general trend observed across China. This indicates that the IPCs have intensified their investment in judicial resources to cope with the growing number of cases and facilitate quicker processing of these cases.

Case settlements

Our comparison of the two periods, 2013–2015 and 2016–2020, reveals regional differences in decision-making trends within the IPCs. We chose these periods for two reasons: i) data availability and ii) because traditional IP chambers additional IP chambers have handled the majority of cases from 2013–2015 have handled the majority of cases from 2013–2015, while after 2016, the majority of IP cases were dealt with by the new IPCs. Although the IPCs were installed in 2014, they have been only responsible for new cases. s, which are still negotiating ongoing cases.

We observed an increase in the proportion of cases withdrawn across the three IPCs, particularly in Beijing and Guangzhou (Table 3). Before 2014, Beijing exhibited a notably high rate (71%) of case rejections, which often resulted from insufficient evidence provided by the plaintiff or patent invalidation, among other reasons.

The change in case of withdrawal proportions in the latter period indicates that IPCs have effectively facilitated case settlements. The settlement has become a preferred method for resolving IP cases, with court mediation enabling firms to reduce litigation costs and reach agreements that protect their interests.

Lawsuit withdrawals often signify that the plaintiff and defendant have reached an out-of-court settlement during the litigation process. This could be because the plaintiff recognized the insufficiency of their evidence, or they identified a potential flaw in their patent that might risk its invalidation. It also becomes apparent that proportionally speaking, court rulings, dismissals of lawsuits, and withdrawals of lawsuits were implemented with varying frequency at different court locations. However, this variation has significantly balanced out after 2016 and might indicate a convergence of the IP courts following the reform in 2014.

In our interviews, we learned that IPCs proactively heighten IP protection awareness and improve companies’ competencies in managing patent-related infringement cases. Firms are becoming adept at thoroughly assessing and evaluating their IP positions, considering possible challenges, and strategizing accordingly. Our field research supports this view, particularly highlighted by the Shanghai IPC initiative, dubbed the ‘Judge Studio.’ This team actively engages with the community by visiting science and technology parks, free-trade zones, and other industry clusters to conduct research, deliver lectures, and promote awareness of IP laws and pertinent issues. In 2018, the ‘Judge Studio’ conducted over 30 activities, reaching out to more than 2000 enterprises. Such initiatives empower firms to enhance their understanding of IP protection and gain valuable practical experience managing IP-related matters.

Composition of main actors in the lawsuit

Despite attempts to streamline IP litigation processes by implementing specialized IP courts, regional differences still exist and affect the composition of plaintiffs and defendants in intellectual property cases.

Foreign companies, particularly those from Japan and Germany, who are acting as plaintiffs, prefer filing lawsuits in Shanghai (15.2%), although they have the choice to pick up another court. In contrast, Chinese firms, when they are plaintiffs, tend to opt for Beijing for their legal actions (Table 4).

Shanghai stands out due to its significantly higher levels of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) and export volumes compared to other first-tier cities. Furthermore, Shanghai serves as a testing zone for new policies. Even before establishing the IPC, Shanghai had a pre-existing proficiency in managing complex cases. According to our interviews, the city’s international context provides judges with greater opportunities to accumulate professional knowledge, equipping them to handle the intricacies of cases involving foreign entities and complex legal issues. This background contributes to Shanghai’s capacity to adapt to and implement international standards, making it a preferred location for litigation by foreign companies seeking expertise and efficiently resolving their legal disputes.

Making efficient decisions

Given the regional differences that seem to affect the work of IP courts, we use fsQCA to study if the changing regional settings and the presence of IP courts in a region affect the efficiency of an IP regime in settling IP disputes. We draw on judicial documents of cases negotiated before and after the IP court reform. Furthermore, given the different time points of such cases, the situation of each region and context has changed over time. These variations allow for an analysis of necessary and supporting conditions.

A necessary condition must exist to cause an outcome, but its existence does not necessarily lead to the occurrence of the outcome (i.e., short trial duration and good trial demonstration). We used a consistency threshold of 0.9 as a criterion for judging necessity. Table 2a, b in the Appendix present the results of our necessity analysis for effective litigation (short duration and demonstration). The results demonstrate that no single condition was necessary to solve an IP litigation process efficiently. Therefore, discussing how these multiple conditions are concurrently combined is particularly important.

Table 5 reports the fsQCA configurations, providing a systematic overview of IP regime modes. Each column in Table 5 represents one solution (a configuration, combination, or group of conditions associated with a specific outcome). Consistency is a solution’s critical criterion, calculated as the proportion of cases with the expected outcome of the overall cases with that combination of conditions. In our case, there are two solutions for the short duration (solution consistency is 0.94) and two solutions for demonstration (solution consistency is 0.93). All the solutions meet the consistency criterion 0.75 (Ragin 2009; Li and Bathelt 2021). The four solutions demonstrate how the various conditions work together to realize effective litigation in IP infringement cases.

Short duration solution

The primary mode of short duration is called IPC Interaction (C1 and C2). In this context, there are two similar solutions in which IP courts and FDI companies are identified as core conditions, proving that establishing IPCs and an international, regional setting of FDI firms affect the speed of the regional decision-making process. Economic development is the second solution’s supportive condition (C1). This condition supports regions or stages with limited experience in handling IP infringements.

Despite the nationwide implementation of the same patent law in China, the application standards vary across regions at different developmental stages. Courts or judges in ‘pioneering’ regions often set precedents for judgments, which, subconsciously, may influence the adjudication process in other areas. Furthermore, the volume of IP cases handled by courts in less economically developed regions is relatively low, leading to a deficiency in experience among judges and IP personnel. Foreign firms are also more likely to establish themselves in economically prosperous regions, where courts and judges consequently gain new litigation experiences and knowledge. As the following quote illustrates, this disparity influences the expertise and specialization of judges and judicial staff, which are crucial factors for establishing model cases.

Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou are the first independent intellectual property courts. There are also many high-quality cases because these cases play an important role in setting rules and guiding the industry. The courts are based on good quality cases, not just the number of cases. If you adjudicate 10000 cases, there are only 10 good cases, which differs from 20 good cases if you decide on 1000 cases. (Interview, Judge#3, November 15, 2021)

China’s specialized intellectual property courts operate under a collaborative team model comprising judges, executors, and technicians. For instance, the Shanghai IPC has appointed 13 technical investigators and nine experts holding higher professional titles. The involvement of zed IP personnel with diverse professional roles throughout the process also shortens the duration of proceedings. Notably, the merger of IP technology expert databases between the Shanghai High Court and IPC in 2018 established a mechanism for sharing databases, expediting the identification of technical facts in infringement cases.

For instance, the IPC employs an advanced judgment approach to address complex technological cases expeditiously. Under this method, if certain facts and requests have been heard, the judge may issue a preliminary judgment on specific aspects of the case. This pre-emptive action prevents infringements during litigation, facilitates the determination of compensation, streamlines the litigation process, and reduces its duration. Consequently, IP regulations are progressively becoming more specialized, with regulations and regional institutions mutually reinforcing each other.

The patent infringement case between the XXX cleaning system of France and XXX Co., Ltd. is the first case in which “advance judgment” has been implemented in Shanghai IPC. [……] The plaintiff and the defendant have a great dispute over whether the alleged infringing product falls into the protection scope of patent-related claims, which determine the amount of compensation… The IPC will decide on this issue first, which will be conducive to the subsequent determination and can help shorten the trial duration. (XXX IPC, First case of advanced trial, 2019)

Demonstration solution

It is demonstrable that judged cases are an important way for judicial personnel to obtain knowledge and orientation for their judgments. Such knowledge enables judicial personnel to consider constant changes in law interpretation and is complementary to statutory law. Therefore, former judged cases are often used as an informal demonstration reference. Every year, China’s Supreme People’s Court selects 50 court decisions that landmark critical law interpretations and informally set judicial standards for complex intellectual property cases. Demonstration cases usually have greater social attention/influence and solve new problems that have not been solved before.

We found two solutions for judicial demonstration. The distinction lies in the first solution, termed Local Diffusion (C3). Here, the core condition is the national context. These regions mainly handle local cases and use these experiences as showcases. This solution operates within an imbalanced judicial context, primarily observed in regions or stages without IPCs. International experience can also serve as an auxiliary condition to assist in forming demonstration effects.

Another solution is IPC Insertion (C4). This is a scenario for a region or phase with an IPC. This solution involves an international context with the presence of FDI companies. In these regions, regional judicial personnel accrue more international knowledge from foreign-involved cases. Simultaneously, these cases serve as advanced demonstration cases, which helps the IP regime form more unified standards.

Conclusion and discussion

China’s IP regime has been constantly reformed, with one of the most recent being the introduction of specialized IP courts in 2014. Although IP law is statutory within a national legal system, its interpretation and enforcement can vary across different regions of the country. Existing research on the European Patent Court and its judicial processes from a geographical perspective (Zipf et al. 2023) inspires this research. The studied reform of the Chinese judicial IP regime is one example of many cases where IP jurisdiction has been reorganized to face new socio-economic developments. This study emphasized the balance between the IP regime, its local implementation, and the surrounding regional socio-economic context.

Concretely, we demonstrated that the introduction of IP courts was driven by the intention to streamline IP litigation and enhance judicial efficiency. This process went hand in hand with China’s economic transformation, which led to an economy that competes based on cost advantages and human and intellectual capital (Liu 2020). Our reconstruction of the IPC reform shows that while there are indications for convergence in jurisprudence, some differences remain due to the regional context of the IP courts. The presence of foreign firms in a region and their higher involvement in IP cases affect the efficiency of IP tribunals and courts. Our analysis shows that IPCs do have an impact on improving judgment efficiency. Especially in international and regional contexts, they enhance the efficiency of the judicial system. The underlying processes provide more resources (judges) and centralize competencies to the specialized IP courts. However, the former experience of the regional judicial regime, for example, also affects the abilities of the newly installed IP courts in dealing with international firms. The case of Shanghai especially illustrates this issue.

Our insights are constrained by limited data availability, particularly the absence of firm-specific data for each litigation case. Thus, we did not answer which concrete factors affect the efficiency of a litigation process. Instead, using data on a court’s regional settings, we measured which contextual settings lead to efficient litigation combined with a specialized regional IP court. Therefore, we also call for further in-depth qualitative research to explore the mechanisms through which these factors may affect the IP litigation process.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to data and privacy protection issues, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Acemoglu D, Johnson S, Robinson JA (2001) The colonial origins of comparative development: An empirical investigation. Am Economic Rev 91(5):1369–1401

Bai JB, Wang PJ, Cheng H (2006) What multinational companies need to know about patent invalidation and patent litigation in China. Northwest J Technol Intellect Prop 5:449

Barley SR (1990) The alignment of technology and structure through roles and networks. Administrative Sci Q 35(1):61–103

Bathelt H, Glückler J (2014) Institutional change in economic geography. Prog Hum Geogr 38(3):340–363

Branstetter LG, Fisman R, Foley CF (2006) Do stronger intellectual property rights increase international technology transfer? Empirical evidence from US firm-level panel data. Q J Econ 121(1):321–349

CNIPA (2020). Status of China’s Intellectual Property Protection in 2020. Beijing: China IP White Book, pp4

Covin JG, Eggers F, Kraus S, Cheng CF, Chang ML (2016) Marketing-related resources and radical innovativeness in family and non-family firms: A configurational approach. J Bus Res 69(12):5620–5627

Cui XS (2010) From “imported” to “self-born”: the birth and development of China’s patent law. Sci Technol Prog Countermeasures 15:46–49. (in Chinese)

DiMaggio PJ, Powell WW (1983) The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. Am Sociological Rev 48(2):147–160

European Commission (2021) Report on the protection and enforcement of intellectual property rights in third countries. https://euipo.europa.eu/ohimportal/en/web/observatory/-/news/report-on-the-protection-and-enforcement-of-intellectual-property-rights-in-third-countries

Fainshmidt S, Witt MA, Aguilera RV, Verbeke A (2020) The contributions of qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) to international business research. J Int Bus Stud 51:455–466

Fan JP, Gillan SL, Yu X (2013) Innovation or imitation? The role of intellectual property rights protections. J Multinatl Financial Manag 23(3):208–234

Gillespie T (2010) The politics of ‘platforms. N Media Soc 12(3):347–364

Glückler J, Lenz R (2016) How institutions moderate the effectiveness of regional policy: A framework and research agenda. Investigations Regionals-Journal. Regional Res 36:255–277

Graneris A (2019) Protection of design patents in China and comparison with European Union law: How foreign companies can protect their design patents in China. Beijing Law Rev 10(1):212–238

Huang C (2017) Recent development of the intellectual property rights system in China and challenges ahead. Manag Organ Rev 13(1):39–48

Huang KGL, Geng X, Wang H (2017) Institutional regime shift in intellectual property rights and innovation strategies of firms in China. Organ Sci 28(2):355–377

Legewie N (2013) An introduction to applied data analysis with qualitative comparative analysis. Forum Qual Soz Forsch/Forum: Qual Soc Res 14(3):1–45

Li P, Bathelt H (2021) Spatial knowledge strategies: an analysis of international investments using fuzzy set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA). Economic Geogr 97(4):366–389

Li MD (2018) Several issues on the construction of China’s intellectual property court system. Intellect Prop 2018(03):14–26. (in Chinese)

Liu X (2020) Structural changes and economic growth in China over the past 40 years of reform and opening-up. China Political Econ 3(1):19–38

Love BJ, Helmers C, Eberhardt M (2015) Patent litigation in China: Protecting rights or the local economy. Vanderbilt J Entertain Technol Law 18:713

Ma YD (2019) The construction of intellectual property court system under the evolution of intellectual property judicial modernization. Application Law 000(003):39–50. in Chinese

Man YN (2013) Intellectual property law and competition law in China-Analysis of the current framework and comparison with the EU approach. Indonesian State Law Rev 1:28

Meyer AD, Tsui AS, Hinings CR (1993) Configurational approaches to organizational analysis. Acad Manag J 36(6):1175–1195

Ng KH, He X (2017) Embedded courts: Judicial decision-making in China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 1–190

OECD (2020) OECD Economic Surveys China. https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2022/03/oecd-economic-surveys-china-2022_29d035e3/b0e499cf-en.pdf

PWC (2011) China strategy: refining yours could open up doors, Price Waterhouse Coopers LLp, 6. http://www.pwc.com/us/en/private-companyservices/publications/assets/gyb-63-china-strategies.pdf

Ragin CC (2006) Set relations in social research: Evaluating their consistency and coverage. Political Anal 14(3):291–310

Ragin CC (2009) Redesigning social inquiry: Fuzzy sets and beyond. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, p. 13–124

Supreme People’s Court of China (2017) Outline of judicial protection of intellectual property rights in China (2016-2020). http://www.law-lib.com/law/law_view.asp?id=566119

Tolbert PS, David RJ, Sine WD (2011) Studying choice and change: The intersection of institutional theory and entrepreneurship research. Organ Sci 22(5):1332–1344

Vis B (2012) The comparative advantages of fsQCA and regression analysis for moderately large-N analyses. Sociological Methods Res 41(1):168–198

Voigt S (2016) Determinants of judicial efficiency: a survey. Eur J Law Econ 42(12):13–27. 183(in Chinese)

World Bank (2008) Doing Business in China 2008. Social Science Academic Press, Beijing. https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/783261468020349761/doing-business-in-china-2008

Xu J (2020) The role of corporate political connections in commercial lawsuits: Evidence from Chinese courts. Comp Political Stud 53(14):2321–2358

Yang W, Yen Y (2010) The dragon gets new IP claws: The latest amendments to the Chinese patent law. IPO Articles and Reports

Zipf M, Glückler J, Khuchua T, Lazega E, Lachapelle F, Hoffmann J (2023) The judicial geography of patent litigation in Germany: Implications for the institutionalization of the European Unified Patent Court. Soc Sci 12(5):311

Acknowledgements

Many thanks are given to Prof. Dr. Johannes Glückler from LMU Munich, Prof. Dr. Robert Panitz from the University of Koblenz, Prof. Dr. Gang Zeng from East China Normal University, and all the reviewers for their constructive comments.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [42130510, 42101175 & 42271197]; Shanghai Planning Office of Philosophy and Social Science [grant number 2023BCK006].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Dr. Lin Zou: Conception and design of the research, data analysis, and interpretation, literature review, interpretation of results, writing original draft, optimization of manuscript; Prof. Dr. Yiwen Zhu contributes to conception and design of the research, interviews collection and interpretation, funding acquisition, review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required as the article did not involve human participants or animal experiments performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zou, L., Zhu, Y. What mode is conducive to an effective regional IP regime? Evidence from intellectual property courts in China. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 1638 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04156-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04156-1