Abstract

Corpus-based translation studies (CBTS) have undergone significant evolution, transitioning from descriptive methodologies to theoretical and applied approaches in recent years. However, the analysis of corpus-based research outcomes is crucial, and the absence of a unified framework often leads to less experienced researchers overlooking critical factors. This, in turn, results in varied interpretations of the same data, substantially compromising the objectivity and scientific rigor of the approach. Inspired by House’s (2014) model of translation quality assessment, Berman (2009)’s view on translation criticism, and De Sutter and Lefer (2020)’s multi-methodological, multifactorial, and interdisciplinary approach to CBTS, this study proposes a tripartite empirical-analytical framework to help researchers identify the potential factors influencing translator decision-making: textual characteristics, translator’s personal attributes, and the sociocultural context of the target language. To evaluate its utility, utilizing the mixed-effects logistic regression method, a case study is conducted to examine significant factors conditioning the reporting verb say and its Chinese translations in an English-Chinese parallel corpus of news texts, employing Appraisal Theory as the basis to determine equivalences and non-equivalences between the source language and target language. The case study shows that the framework facilitates a comprehensive analysis of the corpus findings by encompassing diverse perspectives within this scaffold. As digital technology, studies in multimodal discourse, and CBTS continue to intersect, the framework can also incorporate non-linguistic elements and AI translation tools, provided there are explicit criteria for examining translation phenomena. This framework equips researchers with a comprehensive set of perspectives, enabling them to consider as many factors as possible, thus bolstering the objectivity and scientific rigor of CBTS. The combined use of the structured framework and the multivariate analysis technique offers a holistic approach and stands as a critical advancement in CBTS by standardizing the analysis process and mitigate the subjective variability inherent in explaining translation phenomena.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the past three decades, corpus-based translation studies (CBTS) have emerged as a subfield of translation studies due to the demand for scientifically rigorous and replicable methodologies (Zanettin et al., 2015, p. 20). In a series of seminal articles, Mona Baker (1993, 1995, 1999, 2004) sought to incorporate corpus linguistics into translation studies by closely examining the characteristics of translated text, including translator style, the influence of a source language on the lexical patterning of a target language, the effect of text genres and structures, and other related topics. As the discipline has progressed from descriptive CBTS to theoretical and applied CBTS (Laviosa, 2021), a variety of theoretical and conceptual frameworks, methodologies, and corpus tools have become available for conducting diverse research projects (Fantinuoli and Zanettin, 2015; Hu, 2016). Using comparative and parallel corpora, for example, researchers can examine the impact of linguistic and extra-linguistic factors on the production of translated texts (Saldanha and O’Brien, 2013). Studies on topics such as the relationship between translators and linguistic patterns (Baker, 2002) as well as the use of corpus triangulation and advanced quantitative analytical methods to process large amounts of corpus data have increased the scientific rigor and credibility of research in this field (Malamatidou, 2018; Mellinger and Hanson, 2017). The systematic research methods enable scholars to discover subtler aspects of writings that would otherwise remain undetected if the text were merely skimmed, and in particular, the corpus-driven approach to translation studies can provide researchers some new perspectives to discover certain linguistic and textual differences between a source text (ST) and a target text (TT) (Oakes and Ji, 2012). This form of research also generates the raw data and statistics necessary for testing the validity of hypotheses and theoretical statements regarding the nature of translation based on actual practice (Baker, 2004).

Nonetheless, corpus-based research outcomes necessitate interpretation by scholars, yet it is not uncommon for less experienced researchers to miss critical factors, leading to varied interpretations of the same data. This inconsistency, among other challenges, poses a significant barrier to achieving the desired objectivity and scientific rigor in this approach. The core difficulty stems from researchers’ struggles to embrace a wide array of perspectives to thoroughly explain diverse findings. Therefore, this study aims to integrate these varied perspectives into a cohesive empirical-analytical framework. By doing so, it offers a structured and comprehensive approach that equips researchers analyzing corpus results obtained in a bottom-up manner from a top-down angle with an extensive range of interpretive options. To accomplish this objective, two questions need to be answered: (1) What factors should researchers consider in order to explain corpus results as thoroughly and objectively as possible? (2) How can significant factors be effectively identified to analyze results generated by corpus methods? A case study is conducted to demonstrate that the proposed analytical framework can be effectively applied to CBTS in combination with the multivariate analysis technique.

An analytical framework for CBTS

Over recent decades, the extensive body of literature in translation studies, emanating from a wide range of dimensions, has greatly enhanced our understanding of translation as a process, the role of translators, the norms guiding translation, and the criteria for assessing the quality of translations. The spectrum of approaches to translation has broadened to include linguistic theories (Catford, 1965; Koller, 1992), functional approaches (Nida, 1964; Nida and Taber, 1969; Reiss and Vermeer, 1984), manipulative strategies (Hermans, 1985; Lefevere, 1992), cultural perspectives (Even-Zohar, 1978; Bassnett, 1990), deconstructive methodologies (Venuti, 1994; Benjamin, 2000), cognitive insights (Shreve and Angelone, 2010; O’Brien, 2012), studies in multimodal discourse (Borodo, 2015; Kaindl, 2013; O’Sullivan, 2013), and the nascent domain of machine/artificial intelligence (AI) translation (Garcia, 2009; Macken et al., 2020). On the one hand, this diversification within translation studies underscores the field’s dynamic and evolving character; on the other hand, the ongoing fusion of theoretical insights and empirical findings from various sub-disciplines equips scholars with the tools to formulate new research questions and explore novel theoretical-analytical frameworks. This points towards a comprehensive empirical-analytical framework for CBTS that integrates linguistic/symbolic, textual, cultural, cognitive, and technological dimensions.

Grounded in functionalist translation theory and integrating both linguistic and cultural considerations, House’s (2014) model for evaluating translation quality underscores the significance of functional equivalence, register analysis, cultural adaptation, and adherence to the pragmatic norms of the target culture. This model has found application across academic research, translator training, and professional evaluation contexts. However, despite its widespread use, the model has not been without its critics, who have called for further refinement. While aiming for objectivity through detailed analytical criteria, the model also recognizes the inevitable role of the evaluator’s subjective judgment, which can, to some extent, be compensated for by CBTS with its systematic empirical analysis. Moreover, the model’s applicability across a diverse range of text types and translation scenarios warrants additional consideration, especially since the evaluation of certain text genres may transcend these established parameters. For instance, in societies where censorship prevails, political ideologies might overshadow cultural elements as a dominant influence (Wang, 2007). Similarly, when translating literary texts, esthetic values could become a critical factor affecting translator decisions (Hermans, 1985; Lu, 2013; Ma, 2009).

In parallel, Berman (2009) highlights the significant impact of linguistic, literary, cultural, and historical factors on a translator’s thought process, emotions, and actions within the realm of translation criticism. He advocates for a detailed critical methodology that bridges differences between the ST and TT, promoting a constructive criticism aimed at enhancing the quality of translations under scrutiny. In the meantime, Berman places a stronger emphasis on recognizing translators as active agents within the translation process compared to House’s (2014), arguing that understanding a translator’s competence, professional status, working conditions, and identity is essential for effective translation criticism, alongside the specific socio-cultural contexts in which he or she operates.

More recently, De Sutter and Lefer (2020) have highlighted the absence of a comprehensive explanatory framework for researchers’ focus on a set of rigid and dogmatic translation universals, which fail to provide accurate and reliable explanations of translational phenomena observed in corpus studies. They argued that CBTS should not limit itself to low-level linguistic differences between translated and non-translated texts, nor should it remain isolated from other disciplines. Instead, CBTS should incorporate theoretical and methodological advancements from related fields such as cognitive linguistics, contrastive linguistics, psycholinguistics, and sociolinguistics. Translation, as an inherently multidimensional linguistic activity, is simultaneously influenced by sociocultural, technological, and cognitive factors. Therefore, they proposed a multi-methodological, multivariate, and interdisciplinary approach to CBTS research. Prior to this new agenda, two empirical studies examining multiple factors influencing the presence or omission of the complementizer that in translated and non-translated texts partially demonstrate the effectiveness of this new approach (Kruger and De Sutter, 2018; Kruger, 2019). These factors include discourse-functional and cognitive elements as well as register (e.g., academic writing, creative writing, and reportage).

House’s model of translation quality assessment, Berman’s views on translation criticism, and De Sutter and Lefer (2020)’s multi-methodological, multifactorial, and interdisciplinary approach to CBTS are relevant to this study, addressing the myriad factors influencing translator choices. Drawing inspiration from their insights into translation theory and practice, a three-dimensional analytical framework emerges, focusing on three key variables: the text (the material being translated), the translator (the individual performing the translation), and the target-language society (the broad contexts of the translated text).

As illustrated in Fig. 1, the text dimension of the framework is divided into two main components: linguistic features and textual features. Linguistic features encompass a range of elements that contribute to the structure and meaning of a text. These include phonological, morphological, lexical, syntactical, pragmatic, and discourse features. Here, pragmatic features involve the use of language in context, including implicature, speech acts, and politeness strategies, while discourse features are related to the use of coherence and cohesion devices like conjunctions, reference words, ellipsis, and discourse markers. On the other hand, textual features refer to the distinctive stylistic and structural elements that shape the presentation of a text. These include the layout and organization, such as paragraphing, headings, bullet points, and the incorporation of graphical elements like images and charts. The degree of similarity between the ST and TT significantly influences the translation approach. A higher resemblance often leads to a preference for literal translation, aiming for equivalence in word choice, paragraph structure, and overall text organization. Understanding the text dimension is CBTS as it involves deconstructing the ST and TT to identify linguistic patterns and assess lexical and/or semiotic equivalence. This process helps determine the presence of non-equivalences, which may occur when the ST and TT lack corresponding lexical patterns and textual characteristics.

The complex process of interpreting meaning, context, cultural nuances, and stylistic elements, and then re-creating them in another language is inevitably greatly influenced by the translator’s personal characteristics and background (Venuti, 1994). Idiolect refers to the unique set of linguistic features, vocabulary, and patterns of usage that each individual has. This personal dialect influences how translators understand texts and choose to express ideas in the target language (Saldanha, 2011). For instance, a translator with a rich vocabulary in certain areas may find more nuanced or precise terms in translations involving those areas. Conversely, a gap in their linguistic repertoire could lead to less accurate or more generic translations in unfamiliar domains. Furthermore, the translator’s cultural origins, education, social environment, and experiences, which shapes his or her understanding of cultural references, social norms, historical context, idioms, and humor (Mastropierro, 2018). A translator with a deep understanding of both the source and target cultures is better equipped to find equivalents that carry the same meaning or effect. And the translator’s sense of beauty, style, and artistic merit influences their choices in translating texts, especially literary works (Winters, 2008). Their personal taste affects how they interpret and prioritize such elements as tone, rhythm, flow, and imagery.

The target language society dimension encompasses reader characteristics (Nord, 1997), prevailing societal ideologies (Schäffner, 2010), and collective esthetic values (Bassnett, 2014). Within this analytical framework, ideology is conceptualized similarly to a worldview, influencing perceptions of reality through shared mental constructs, beliefs, opinions, attitudes, and evaluations prevalent among specific communities within a society (Reisigl and Wodak, 2009, p. 88). The importance of understanding the TT readers is underscored by their significant influence on translation strategies; translators need to ensure the target audience can effectively understand and resonate with the TT’s conveyed messages (Bassnett Trivedi, 1998; Tymoczko, 2007). It’s a common practice to adapt translated works to make them more ‘appropriate’—ensuring they are understood and accepted by the target society. Techniques such as annotation, rewriting, and the omission of specific statements often support this adaptation process (e.g., Li et al., 2011; Ping and Wang, 2024). Furthermore, in societies where censorship is prevalent, publishers or commissioners typically instruct translators to make certain adjustments, like avoiding sensitive terms or omitting contentious content (Bennett, 2016). Translators might also engage in self-censorship, cautiously avoiding content that could provoke the society’s censorship mechanisms (Wang, 2007).

Among these three dimensions, the translator’s role is crucial in managing the interplay of these factors because translators make key decisions on handling linguistic and textual challenges and determine to what extent STs are adapted to suit target readers, as well as the dominant ideologies and esthetic values of the target-language society (a process known as localization). However, in most cases, it is impossible for researchers to directly interview the translator despite their efforts to accurately discern the cognitive processes underlying a translator’s decision-making. Therefore, researchers have to analyze the outputs produced by corpus tools, primarily at linguistic and textual levels, and then identify why specific translation phenomena related to linguistic and textual features occur. For example, are they mainly caused by non-equivalent expressions in the target language, the individual translator’s personal style of language, or censorship in the target-language society? It is noteworthy that without interviewing the translator, some of the factors are actually difficult to precisely determine on certain occasions (as revealed in our case study in the following section). In this situation, we have to leave them behind.

To apply this framework to an empirical analysis of corpus results, we can generally follow these steps: (1) formulate hypotheses or research questions, such as examining explicitation in literary versus technical translations; (2) establish two parallel datasets, the literary and technical ST and TT corpora; (3) identify linguistic patterns of explicitation by comparing the STs and TTs; (4) determine the factors contributing to these instances of explicitation according to the three-dimensional framework; (5) use multifactorial methods to investigate which factors significantly influence this specific translation phenomenon in these TTs; and (6) organize findings systematically and summarize key insights. By carrying out these steps, this analytical framework promises to offer researchers valuable guidance for delving deeper into the analysis and understanding of results. It would also be useful to examine various factors influencing the translation of particular linguistic patterns (as exemplified in our case study), translation norms such as simplification and explication (as exemplified in the above application procedure), and translation phenomena like ideological shifts (by identifying shifts in meaning, omissions, or additions in translated texts first).

Meanwhile, it is important to note that CBTS is more user-friendly for researchers to identify specific linguistic patterns (e.g., the word say in our case study) than translation phenomena such as explicitation and ideological shifts, as the latter two involve different linguistic patterns. Additionally, determining the factors contributing to linguistic patterns and translation phenomena is time-consuming. Therefore, we should consider the size of the data under investigation when designing a project. A dataset that is too large may be impractical, while a small one cannot produce credible results.

A case study

Data and methods

To demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed analytical framework in the context of CBTS, the case study begins with an emphasis on data collection, focusing on news texts—a genre renowned for its popularity. Recognizing that news discourse is often ideologically and socially constructed, as highlighted by van Dijk (2009, p. 195), the study underscores that news translation transcends simple linguistic conversion. It embodies a complex, multidimensional practice encompassing cultural exchange, informed decision-making, economic development, social cohesion, and effective crisis management globally. To concretely showcase the analytical framework’s applicability, this case study selects news texts and their translated versions from The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal as illustrative examples. In news texts, the use of reporting verbs is considered a typical discourse strategy employed by journalistic authors in order to demonstrate neutrality and objectivity by attributing opinions and values conveyed in source quotations (Bednarek and Caple, 2012; Bell, 1991; Reah, 2002; Semino and Short,2004; van Dijk, 1988). In addition, reporting verbs represent one of the most important lexico-grammatical patterns for analyzing ideological positioning in news discourse (Bednarek, 2006; White, 2006), as they reveal the extent to which journalists share the opinions and attitudes of their news sources. Given the functions of reporting verbs in meaning construction, this case study aims to explore how ST-to-TT equivalences, and non-equivalences may be influenced by factors related to the text, translator, and target language society by examining the reporting verb say and identify the factors significantly affecting these equivalences and non-equivalences.

With the assistance of Tengyuan Cui, an engineer from Shanghai Tmxmall Information Technology Co. Ltd. (https://www.tmxmall.com), news texts by The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal are randomly selected from their English and Chinese websites (https://www.nytimes.com/; https://cn.nytimes.com/; https://www.wsj.com; https://cn.wsj.com) by utilizing the Heartsome Tmx.editor, a translation memory bank and terminology database maintenance tool developed by the company. The content on the Chinese websites of the two news outlets is tailored for a highly educated, high-income, and internationally-minded Chinese audience, with the goal of providing them with top-notch coverage of global current events, business, and culture, including both translated versions of English-language news articles from their English-language websites and original articles written by local Chinese authors and columnists exclusively for the Chinese website. After obtaining parallel corpus comprising 328,919 sentence pairs from 18,754 news texts, the search function of the Heartsome Tmx.editor is used to locate instances of the reporting verb say and its grammatical forms (says, said, and saying), resulting in a total of 64,307 sentence pairs. Then, each sentence containing any of these terms is examined to eliminate instances that do not function as reporting verbs, such as let’s say and say yes or no.

After the manual examination, 62,407 sentence pairs are obtained and labeled with their corresponding “Article ID” (i.e., source article). Then we begin to consider the factors may influence the translator’s decision. Since translator details (e.g., nationality, educational background, esthetic type, age, gender, etc.) are unavailable, we do not consider them here, but we do consider variability arising from different source articles. Additionally, we carefully read these sentence pairs in both English and Chinese and find no content that might be removed in response to China’s online censorship. Therefore, in this context, our focus is on textual factors, namely tense, sentence length, subject, and attitude. Chinese lacks a tense system like English (Wheatley, 2014), although there are particles that can be added immediately after verbs to express the aspect of the action. Thus, we attempt to observe whether tenses in the original English sentences may affect the ST-to-TT equivalence and non-equivalence here. The factor of sentence length is used to examine whether the sentence containing the reporting verb say in the ST is broken into two or more sentences, merges with any other clauses, or remains unchanged in the TT. The factor of subject is utilized to observe whether the subject of the reporting verb in the ST is the same as that in the TT. The factor of attitude involves ideological elements, focusing on whether the TT remains neutral or becomes positive or negative. When the translated verb is neutral, it signifies no change in attitudinal stance. The four factors are labeled manually for each sentence in the corpus in terms of their respective levels, as shown below:

-

Tense: Present simple; Present perfect; Past simple; Past perfect; Future simple; Gerund and present participle

-

Sentence length: Splitting; Combining; No change;

-

Subject: Change; No change;

-

Attitude: Positive; Negative; Neutral.

The third step involves identifying categories of Chinese translations of the reporting verb say and determining ST-to-TT equivalences and non-equivalences. To enhance the credibility and validity of this case study, the Appraisal framework (Martin, 2000) is employed as the basis for the criteria and methods used to clarify ST-to-TT equivalences and non-equivalences. This choice is made because the reporting verb say can be classified within the subsystem of engagement in the Appraisal framework. The reasons for using the Appraisal framework as the basis for criteria, as well as how to formulate and apply these criteria to identify ST-to-TT equivalences or non-equivalences, are detailed in the following subsection, as this process is significant yet complex.

Subsequently, following the studies by Kruger and De Sutter (2018), Kotze (2019), and De Sutter and Lefer (2020), using the generalized linear mixed-effects model, a multivariate analysis is conducted to help identify significant factors. It is necessary because each source article may correspond to several sentences, thus introducing variability across an article. This approach allows us to ascertain whether ST-to-TT equivalences and non-equivalences are influenced by the aforementioned factors, while also accounting for the random effect of different articles.

ST-to-TT equivalences and non-equivalences: reporting verbs as appraisal resources

Transformations of appraisal resources are considered crucial factors in the translator decision-making (Munday, 2012a). Appraisal is one of the most fundamental semantic resources for constructing interpersonal meaning in discourse (Martin, 2000) because it allows speakers of a given language to express personal opinions, adopt positions, and negotiate solidarity. Typically, an appraisal system consists of the subsystems of attitude, engagement, and graduation. Attitude involves a person’s feelings, including emotional responses and evaluations of behaviors and objects. The concept of engagement pertains to the origin of attitudes and the interaction of voices inside and outside the text (i.e., with an actual or imagined audience). Graduation involves the grading of phenomena that amplify feelings and distort classifications (Martin and White, 2005, pp. 34–35).

While systemic functional linguists who study the relationship between language and its functions in social settings are keenly interested in how appraisal resources are used in various types of texts to express the attitudes of text producers (e.g., Breeze, 2017; Wang and Zhang, 2014), a large number of translation studies are concerned with the deviation of evaluative connotations in the TT and the resulting differences in attitudes between the ST and TT. For instance, Arjani (2012) examines explicit attitude markers in translations of 100 dissertation abstracts in the social and natural sciences and finds that omitting these markers resulted in the loss of evaluative connotations in the translated abstracts. Munday (2017) analyzes three types of appraisal resources in President Trump’s inaugural address, and six Spanish translations of the address, and reveals that shifts in engagement resources—specifically, shifts in counter-expectation indicators and pronouns—have the greatest impact on positioning.

In addition to investigating how deviations in evaluative meaning occur, some researchers have focused on identifying the underlying causes. By comparing the Spanish translations of President Obama’s speeches with the originals, Munday (2012b) discovers that graduation resources are more variable than attitude resources. He observes that the lowered graduation requirements for the TT are contingent on the translator’s proficiency, sensitivity, and comprehension of the ST. Zhang (2013) analyzes the translation of attitude resources in news headlines that briefly describe four international events, demonstrating the heavy mediation and re-contextualization of the news headline texts due to the imbedding of the transeditor’s knowledge and values, which may sometimes reveal the stance of a news agency.

Several studies have been conducted in accordance with the paradigm of critical discourse analysis (CDA), with an emphasis on the role of ideology in translator selection. Chen (2011) concludes, after analyzing engagement resources in 26 commentaries on the Economic Cooperation Framework Agreement published by the Liber Times and Taipei Times, that translators may shift intersubjective positioning in order to promote solidarity, which corresponds to the pro-independence ideology of the Taipei Times and the ideological implications of news translators as media practitioners. To uncover nuanced ideological differences in positioning, Pan (2015) analyzes evaluation resources in reports on the issue of human rights in China published by foreign newspapers and by Reference News, an official Chinese newspaper that translates foreign reports for Chinese audiences.

Through the lens of evaluation resources, these studies have deepened our understanding of the subjectivity and intervention of translators. Because of the time and effort required to add tags to a large-size text corpus, the qualitative analytical approach has been adopted in many of these studies by identifying shifts in attitudes or ideologies, observing how variation occurs, and discussing one or two possible causes of variation within a small corpus of texts that address a particular sociopolitical issue (Liu et al., 2022). By contrast, after the descriptive statistical analysis of ST-to-TT equivalences and non-equivalences in this subsection, we utilize mixed-effects logistic regression to explore the relatively large dataset collected for this case study. As mentioned in the previous subsection, this approach aids in identifying the factors that significantly influence translation outcomes, which are detailed in the subsequent subsection.

According to Martin and White (2005, pp. 99–100), the subsystem of engagement follows a cline from monogloss to heterogloss and reveals the author’s level of interpersonal involvement (Martin and White, 2005, pp. 99–100). Heteroglossias invoke or permit dialogic alternatives, whereas monoglossias (i.e., unmitigated or categorical assertions) neither recognize nor consider alternative positions. In Fig. 2, it can be noted that reporting verbs may occur anywhere along the monogloss–heterogloss cline (Martin and White, 2005, p. 134; Munday, 2017, p. 87). This cline serves not only as the theoretical foundation for the case study, but also as an instrument for determining the equivalence or non-equivalence of reporting verbs in a ST and its translation. According to Mellinger and Hanson (2017, 2022), meaningful statistical analysis in empirical translation research requires accurate and valid measurements.

Figure 2 shows the categories of reporting verbs based on dialogical space for alternative positions. The greater the separation between the category and categorical assertions, the greater will be the category’s heteroglossia. On the monogloss–heterogloss cline, endorsements such as show, demonstrate, and prove are dialogically contractive, distancing attributions such as claim and allege are dialogically expansive, and acknowledging attributions such as say, believe, and describe fall somewhere in the middle. When endorsing formulations, propositions attributed to external sources are interpreted as correct, valid, undeniable, or otherwise maximally justifiable by the text’s internal authorial voice, thus closing the space for dialogic alternatives (Martin and White, 2005, p. 126). In contrast, authorial voices can be presented as aligned or misaligned with propositions or as neutral or disinterested when acknowledging or opposing formulations. In particular, distancing attributions represent authorial voices that explicitly decline to assume responsibility for propositions, thereby maximizing the available space for dialogic alternatives (Martin and White, 2005, pp. 113–114).

Hyland (2004, p. 28) suggests two classification methods for reporting verbs that are useful for determining whether or not equivalences exist between the ST and TT (Munday, 2017). One classification method divides rhetorical functions into research acts (e.g., demonstrate and observe), cognition acts (e.g., consider and think), and discourse acts (e.g., say and discuss). The second method involves the evaluative potential of the source, categorizing the related functions as factual (e.g., acknowledge and establish), counter-factual (e.g., exaggerate and neglect), and non-factual. The non-factual function may report on the source’s stance or position as positive (e.g., advocate and argue), neutral (e.g., say and remark), tentative (e.g., believe and hypothesize), or negative (e.g., attack and object).

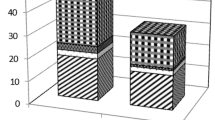

According to the preceding classifications, it is evident that the reporting verb say belongs to the category of acknowledging attributions, as it denotes a discourse act that introduces a proposition which the source considers neutral. In this case study, the taxonomy in Fig. 2 is used to determine whether the ST and TT are equivalent. Based on this taxonomy, the 62,407 sentence pairs are divided into four categories (see Table 1): bare assertions, endorsements, acknowledging attributions, and distancing attributions. The diversity of bare assertions is particularly intriguing. In Chinese translations, when the subject of say and the subject of the propositions, which take the form of statements, are identical, say is frequently omitted. Consequently, the TT propositions are transformed into categorical assertions. In Table 2, the translations of endorsements, acknowledging attributions, and distancing attributions into Chinese words are presented in detail and English glosses are added to the Chinese characters.

A reporting verb in the ST and its translation in the TT are equivalent from the perspective of the monogloss–heterogloss cline if they are of the same type. Any alterations in type, such as from acknowledging attributions in the ST to endorsements in the TT, are regarded as a non-equivalence between the ST and TT. On the basis of this premise, Table 1 shows that 78.78% (49,167 instances) of the total 62,407 instances include acknowledging attributions, indicating that the translator generally adhered to the principle of fidelity. A non-equivalence between the ST and TT is found in 13,240 instances (21.22% of the total), including bare assertions (5664 instances, 9.08%), endorsements (6469 instances, 10.37%), and distancing attributions (1107 instances, 1.77%).

Following this, to enhance our understanding of how ST-to-TT equivalences or non-equivalences are achieved through these categories, we randomly select one example from each category. Additionally, we aim to provide explanations for the choice of the Chinese counterparts, utilizing the three levels of factors discussed in the previous section. Here, we strive to consider factors beyond those labeled in the corpus, particularly those related to the individual translator (by “guessing” their nationality, educational background, etc.). Analyzing these instances may enhance our understanding of certain minor factors relevant to the entire corpus but significant for the individual news story, thereby deepening our insights into the complexities of translation phenomena.

Bare assertions

It is surprising to learn that 5,664 instances (9.08%) of say are omitted from the Chinese translations. As previously stated, our comprehensive examination of the sentence pairs reveals that the subject of the proposition is its source.

Example 1:

Rebekah Jean Duthie, who lives in Queensland, Australia, and works for the Australian Red Cross, says she regularly gathers with friends for “coloring circles” at cafes and in one another’s homes.

Translation: 家(home)住(live)昆士兰(Queensland)的(auxiliary after a modifier)瑞贝卡·简·达西(Rebekah Jean Duthie) 在(in)澳大利亚(Australia)红十字会(Red Cross)工作(work)。她(she)定期(regularly)和(with)朋友(friends)在(in)咖啡馆(cafe)或(or) 彼此(one another)的(auxiliary after a modifier)家(home)一起(together)玩(play)“转圈(circles)涂色(coloring)”。

By omitting the reporting verb says in Example 1, the original proposition (she regularly gathers with friends for “coloring circles” at cafes and in one another’s residences) and its source (Rebekah Jean Duthie) are transformed into a bare, categorical statement without the use of an external source. This transition from a heteroglossic to a monoglossic formulation demonstrates the shift in narrative perspective from Rebekah Jean Duthie (the original source) to the unknown journalistic author. This adjustment might indicate the translator’s trust in the accuracy of this statement. By making this choice, the translator presumes that the journalist has verified the truth of this claim, possibly stemming from a belief in the principles of journalistic professionalism. Furthermore, this alteration enhances the conciseness of the translated version. Notably, the single sentence in the ST is divided into two in the TT here. Thus, stylistic conciseness facilitates earlier processing for the reader.

Endorsements

In bare assertions, the TT indicates no source other than the hidden journalistic authorial voice. In contrast, an endorsing formulation includes both a source for the proposition and the journalistic author’s voice, which is also embedded. Moreover, the journalist implies that the assertion linked to an external source is accurate or credible. The following is an example:

Example 2:

In a report to be published on Monday, and that has been provided in advance to The New York Times, Kaspersky Lab says the scope of the attack on more than 100 banks and other financial institutions in 30 nations could make it one of the largest bank thefts ever, and one conducted without usual signs of a robbery.

Translation: 卡巴斯基(Kaspersky)实验室(lab)将(will)定于(schedule)周一(Monday)公布(publish)的(auxiliary after a modifier) 报告(report)预先(in advance)提供(provide)给(to)了(auxiliary indicating a past action)《纽约时报》(The New York Times) 。 报告(report)显示(show), 这场(this)针对(for)30 个(quantifier)国家(nation)逾(over)100 家(quantifier)银行(bank)和(and) 金融(financial)机构(insititution)的(auxiliary after a modifier)攻击(attack)行动(action), 可能(perhaps)是(be)有史以来(in history) 规模(scale)最大(largest)的(auxiliary after a modifier)银行(bank)盗窃(theft)案(case)之一(one of), 而且(additionally)是(be) 在(in) 没有(no)常见 的(commonly seen) 抢劫(robbery)迹象(trace)下(below)发生(happen)的(auxiliary after a modifie) 。

In Example 2, the source of the proposition (the scope of the attack on more than 100 banks and other financial institutions in 30 nations could make it one of the largest bank thefts ever—and one conducted without the usual signs of robbery) is Kaspersky Lab in the ST, but its source is modified to create the report (报告) published by Kaspersky Lab in the TT. Consequently, the acknowledging attribution says becomes an endorsement 显示 (show), thus imbedding the journalistic author’s voice and implying that the proposition is justified. The shift from the acknowledging attribution says to the endorsement 显示 (show) suggests the translator has less room for dialogic alternatives and has more faith in the Kaspersky Lab report than in the original journalist.

Despite the identification of several minor differences between the ST and TT, it remains challenging to ascertain whether the translator made these choices intentionally. A translator lacking expertise in evaluation systems may not be aware of these distinctions. The transliterated term 卡巴斯基实验室 (Kaspersky Lab) is notably longer than the simple term 报告 (report). Considering the fact that the majority of Chinese words are typically bi-syllabic, opting for the coined four-character term 卡巴斯基 (Kaspersky) could potentially overwhelm Chinese readers cognitively. This could lead the translator to ultimately choose the shorter and more reader-friendly two-character term 报告 (report). (Kaspersky Lab is a global leader in cybersecurity solutions and services for businesses and consumers, protecting the world’s businesses, critical infrastructure, governments, and consumers.) What’s more, similar to Example 1, the single sentence in the ST is also divided into two in the TT. Thus, it is likely that the subject shifting and sentence splitting are also a result of the translator’s intent to facilitate easier processing of information by the reader.

Acknowledging attributions

As previously stated, the ST and TT are presumed to be equivalent when the acknowledging attribution say is translated into Chinese as an acknowledging attribution within the sub-system of engagement of the Appraisal framework. However, subtle distinctions between them still can be detected. Example 3 demonstrates the translation of two instances of say into two acknowledging attributions written in Chinese.

Example 3:

But most retailers say Google is the most important source of online shoppers, and some say they cannot afford to pay to list all their products.

Translation: 但是(but), 多数(most)零售商(retailer)都(all)认为(believe), 谷歌(Google)是(be)网络(online)客户(shopper) 最(most)重要的(important)来源(source)。也(also)有些(some)人(people)说(say), 他们(they)承担(afford)不起(not) 把(marker for a direct object)自己(one's own)所有的(all)产品(product)都(all) 罗列(list)出来(out)的(auxiliary after a modifier)费用(expense)。

In Example 3, the first instance of say is transformed into an act of cognition 认为 (think) and the second instance is rendered as a discourse act 说 (say). The use of two distinct expressions in the TT likely reflects the translator’s preference for lexical richness and linguistic beauty in the co-text. However, we do not include lexical richness as a variable in this case study as we find such examples to be infrequent upon examining all instances.

Distancing attributions

In comparison to acknowledging attributions, distancing attributions are more dialogically expansive, thereby creating more room for dialogical alternatives. The following is an example of one such instance:

Example 4:

In a speech here and a written letter of proposals for reform, Cameron called on fellow European leaders to grant him a series of concessions to help persuade wavering Britons to remain in a bloc that critics say has become a vast bureaucracy impinging on their national sovereignty and way of life.

Translation: 他(he)呼吁(call on)欧洲(Europe)其他(other)领导人(leader)对(for)他(him)做出(do) 一些(some)让步(concession), 从而(so that)帮助(help)他(him)说服(persuade)犹豫不决的(wavering) 英国人(Briton)留(remain)在(in)欧盟(EU)。批评者(critics)指责(criticize) 欧盟(EU)已经(already)变成(become)一(one)个(quantifier) 庞大的(large)官僚(bureaucracy)体系(system), 损害(harm)了(auxiliary indicating a past action) 英国(UK)主权(sovereignty)和(and)生活(life)方式(style)。

Example 4 is an excerpt from a news item related to the politically charged issue of Brexit. The translated word 指责 (criticize) does not indicate the journalist author’s voice; instead, it accentuates the negative attitudes of the source (i.e., the critics) towards the proposition (a bloc has become a vast bureaucracy impinging on their national sovereignty and way of life) in the TT, thereby emphasizing the conflicts between critics, the British government, and the European Union (EU). This perspective on international events such as Brexit aligns with the prevailing ideologies of Chinese society (Xinhua News Agency, 2020). The translator or editor may have prioritized readership or profits when deciding to cater to the intended audience. Furthermore, it is also likely that the translator of the text in Example 4 is a Chinese individual educated in China who has unconsciously adopted the worldview of dominant Chinese blocs. Since it is impossible to identify the specific translator, such changes are categorized under the “Attitudinal change” variable at the textual level.

Factors conditioning ST-to-TT equivalences and non-equivalences

After examining the examples of various categories of appraisal resources transformed in the TT and the potential reasons behind the translator’s choices, this subsection aims to explore the factors that significantly influence equivalences and non-equivalences between the ST and TT. Consequently, a logistic mixed model is fitted with equivalences (acknowledging attributions) and non-equivalences (including bare assertions, endorsements, and distancing attributions) as the binary dependent variable. The independent variables include manually labeled “Tense,” “Sentence length,” “Subject,” and “Attitude,” as presented in the “Data and Methods” subsection.

As some levels of “Tense” and “Sentence length” are disproportionately infrequent (e.g., only 370 cases of future simple compared with 35,286 cases of present simple), these infrequent levels are combined into broader categories (e.g., “Others”) to mitigate potential problems caused by data imbalance. In addition, to account for the possible effect of individual articles, the “Article ID” is incorporated as a random factor. Prior to modeling, the data is split into training and testing sets (70% training, 30% testing), with the training set used for fitting models and the test set reserved for assessing the performance of the final model. The modeling procedure is performed with R (R Core Team, 2023).

The results indicate that the full model, which includes all the independent variables and the random factor, fails to converge. We note that the “Attitudinal change” variable in the dataset exhibits a severe imbalance, with 62,385 out of 62,398 observations classified as “Neutral,” while only 11 instances fall into the “Negative” category and 2 into the “Positive” category. This extreme imbalance is likely to significantly diminish the statistical power of the model, as the small number of “Negative” and “Positive” observations provides insufficient information to reliably estimate their effects. After removing “Attitudinal change” which suffers from a severe data imbalance, the final model with the remaining three independent variables (“Tense,” “Sentence length,” and “Subject”) and the “Article ID” as the random factor exhibits that the coefficients for all the independent variables are significant (p < 0.01).

Further statistical evaluation of the final model indicates that the final model achieves a statistically significant improvement in fit compared to the null model, which is the baseline model that assumes translation equivalency does not depend on any of the independent variables (p < 0.001). The classification accuracy of the final model is 0.8766, meaning that ~87.66% of the predictions made by the model are correct. Nevertheless, the model exhibits a high sensitivity (0.9959) but a lower specificity (0.4334), suggesting that while the model is very good at correctly identifying equivalence cases, it is less adept at identifying non-equivalence cases. This is likely to be due to the extreme imbalance of equivalence (49,166 instances) vs. non-equivalence (13,241 instances) in the dataset. Additionally, the C Index of 0.7342 manifests fairly good predictive performance of the final model. The VIF values, all close to 1, suggest minimal multicollinearity among the predictors, indicating that the independent variables are not highly correlated and appropriate for inclusion in the model.

Table 3 presents the likelihood (indicated by “Odds Ratios”) of the “Non-equivalence” translation of the reporting verb say (compared with the reference level “Equivalence”), as influenced by the three factors including “Tense,” “Sentence length,” and “Subject.” In addition, the impacts of the three factors are visualized in the effect plots, as shown in Fig. 3, Fig. 4, and Fig. 5. In these figures, effect plots of “Tense,” “Sentence change,’ and “Subject shifting,” showing how their different levels (x-axis) lead to changes in the predicted probability of “Non-equivalence” (y-axis). The red lines indicate the boundaries of the 95% confidence interval. This model explains 52% of the variation in the data, as shown by both the marginal and conditional R2 values.

Hence, the results from Table 3 and Fig. 2 can be described in more detail as follows:

-

Tense: Compared to the reference level “Present simple,” using other tenses (labeled “Others,” including “Future simple,” “Gerund and present participle,” “Past perfect,” and “Present perfect”) increases the probability of non-equivalence by 1.26 times, while using “Past simple” increases the probability of Non-equivalence by 1.13 times. In other words, in instances where tenses other than “Present simple” are used in the ST, the translator is more likely to favor non-equivalence in the Chinese translation of the reporting verb say.

-

Sentence length: When there is a change in sentence structure (compared to the reference level “No change”), the odds of non-equivalence rise significantly by 15.05 times. In other words, in the instances of “Combining” and “Splitting”, the translator is more likely to favor non-equivalence in translating the reporting verb say. (Furthermore, we investigate the occurrences of “Combining” and “Splitting,” revealing that there are only six instances of “Combining”, which does not constitute a significant portion compared to the number of the instances of “Splitting”).

-

Subject: If the subject of the verb say shifts (compared to the reference level “No change”), the odds of non-equivalence increase dramatically, by 57.78 times. In other words, when there is a subject shift, non-equivalence is more likely to occur in the translation of the reporting verb say.

Summary

The descriptive statistics of frequency data indicates that, according to the criteria developed from appraisal systems, the equivalence between the ST and TT for the reporting verb say is not achieved in approximately one-fifth of cases. This suggests that deviations from the principle of fidelity are not prevalent. In general, the Chinese character equivalents of the reporting verb say accurately convey its original meaning from a linguistic perspective.

With regard to the factors affecting ST-to-TT equivalences and non-equivalences, the results obtained from the generalized linear mixed-effects model demonstrate that sentence length, and subject are three main factors conditioning equivalences and non-equivalences at the textual level. Specifically, the translator tends to choose words that are not equivalent with the ST when the reporting verb say is not in the present simple tense in the ST, when the sentence containing this verb is divided into two or more in the TT, or when the subject of this verb changes in the TT.

It is unfortunate that we cannot get access to translator details, but very possibly, these three factors are connected to the translator’s understanding of journalist practices and news writing. Conciseness and legibility are considered crucial for news texts, given the limited space in periodicals and the audience’s receptiveness. For example, on the one hand, the omission of the original sources in 5,664 instances (as shown in Example 1) may suggest that translators trust the journalistic standards of professionalism, leading them to assume that information from original sources has been verified by journalists. On the other hand, readability is prioritized over strict fidelity by choosing to exclude original sources and transforming quotations into simple assertions, and shifting the perspective from the ST to the journalistic author in the TT. This is also the case with Example 2 when the translator opts for the two-character word 报告 (report) rather than the complex, unfamiliar term 卡巴斯基实验室 (Kaspersky Lab) in the TT as the subject of the reporting verb. In the meantime, the long sentence is split into two in the TT.

Furthermore, Example 4 illustrates how translators may consciously or unconsciously cater to dominant ideologies prevalent in the target society. These ideologies may arise from the translator’s socio-cultural background or their willingness to align with the beliefs or values of the target society. As discussed earlier, the Chinese translation of the reporting verb 指责 (criticize) in Example 4 conveys the negative stance of the source and emphasizes the conflicts between pro-Brexit and anti-Brexit factions. This portrayal of Western nations aligns with the prevailing ideologies of Chinese audiences, shedding light on how translators adapt their work to the political ideologies of Chinese contexts.

It is also noteworthy that specific modifications in translation projects are necessitated by the demands of patrons or by the censorship prevailing within a particular society—this includes the ideologies endorsed by patrons or the mandates of censorship institutions although we do not find any examples in our dataset. A study conducted by Wu and Zhang (2015) highlights that, in order to engage Chinese online readers and successfully navigate the censorship protocols when translating English news headlines concerning the South China Sea disputes, translators are inclined to adopt strategies like substitution, omission, and alterations in modalities and actors. These tactics are aimed at harmonizing with divergent ideologies, thereby ensuring that the translated content aligns with the expectations and regulations of the target context.

Discussion and conclusion

The intricacies of the translator’s decision-making process are underscored by the complex interplay of various influencing factors previously delineated. The challenge of prioritizing one factor over another can inadvertently lead to the oversight of crucial aspects during the evaluation of corpus results. However, the application of the three-dimensional analytical framework in this case study has proven instrumental with the combined use of the mixed-effects logistic regression method, enabling researchers to conduct a comparatively comprehensive assessment of results by recognizing the multifaceted influences on translation decisions in news texts. This would also be useful to examine various factors influencing the translation of particular linguistic patterns (as exemplified in our case study), translation norms such as simplification and explication (as exemplified in the application procedure in the second section), and translation phenomena like ideological shifts (by identifying shifts in meaning, omissions, or additions in translated texts first).

In other scenarios, the employment of other sophisticated statistical methods apart from mixed-effects logistic regression may illuminate the translator’s choices within specific research contexts. For example, quantitative linguistic tools are utilized to analyze and compare stylistic nuances between three translations of Tagore’s gnomic verses by different translators at distant times (Liu and Fang, 2017). While noting the presence of stylistic differences between versions with regard to high-frequency thematic words, typical linguistic patterns, and lexical richness they contend that variations in style are the result of both the translator’s educational background and adherence to translation standards. Should the analytical framework developed in this study be adopted, it is possible to broaden the scope of the analysis from merely linguistic, textual dimensions and the broad socio-cultural contexts to encompass an examination of the individual idiolect and personal esthetic values of the translators, and the shift of collective esthetic values within the society of the target language over time.

It’s important to acknowledge that the primary factors influencing the translation process can vary significantly from one genre to another. For instance, given the stylistic nuances and distinct communicative objectives of different genres, a translator’s individual linguistic flair and esthetic inclinations are likely to exert a more significant influence on the translation of literary works. In contrast, the translation of political texts might be more profoundly shaped by the translator’s socio-cultural context and the dominant ideologies of the society using the target language. This nuanced understanding underscores the importance of considering genre-specific factors in the analysis and interpretation of translation practices, which is a limitation of our case study as it does not encompass several genres of data.

What needs to be equally noted is that within the realm of CBTS it is imperative to establish standards for identifying specific translation phenomena—ranging from simplification, normalization, and conventionalization of source language and textual patterns, to the adoption of domestication and alienation strategies, and the manifestation of “translationese” across various linguistic levels. The monogloss–heterogloss continuum, formulated through the Appraisal framework in this article’s case study, exemplifies this need. Only by accurately identifying these and other translation phenomena in parallel corpora can researchers engage in a meaningful discussion about the underlying reasons for a translator’s selection of diction, tone, methods, etc.

In addition, this framework can be adeptly applied to analyze findings from CBTS that delve into multimodal translations (e.g., Kress, 2020; Mus, 2021) or collaborative endeavors between human translators and artificial intelligence (AI) systems (e.g., Brône and Oben, 2015; O’Thomas, 2017), provided there are clear and well-defined criteria for examining the specific translation phenomena in question. This broadening of scope highlights the critical need to integrate these diverse elements into our holistic understanding of translation processes. It responds to calls from some scholars for a critical reevaluation and expansion of our conceptual frameworks of translation to encompass both human and AI translators (Carl, 2022; Mihalache, 2021; Zheng et al., 2023). Thus, the introduction of this analytical framework is both timely and in step with rapid advancements in multimodality research and digital technologies. It acknowledges the increasing complexity of translation practices and the evolving landscape of translation studies. By establishing a structured empirical-analytical paradigm that bridges empirical data with theoretical analysis, this approach signifies a notable progression in the field of CBTS. It standardizes the interpretation process and mitigates the subjective variability that often muddles the explication of translation phenomena.

Data availability

Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to the author.

References

Arjani S (2012) Attitudinal markers in translations of dissertation abstracts in social and natural sciences. Unpublished master’s thesis, Allameh Tabataba’i University, Tehran, Iran

Baker M (1993) Corpus linguistics and translation studies: implications and applications. In: Baker M, Francis G, Tognini-Bonelli E (eds) Text and technology: in honour of John Sinclair. John Benjamins, Amsterdam, pp 233–250

Baker M (1995) Corpora in translation studies: an overview and some suggestions for future research. Target 7(2):223–243. https://doi.org/10.1075/target.7.2.03bak

Baker M (1999) The role of corpora in investigating the linguistic behaviour of professional translators. Int J Corpus Linguist 4(2):281–298. https://doi.org/10.1075/ijcl.4.2.05bak

Baker M (2002) Corpus-based studies within the larger context of translation studies. Genes Rev Sci Do ISAI 2:7–16. https://www.alc.manchester.ac.uk/ctis/research/themes/corpus-based-translation-studies/

Baker M (2004) A corpus-based view of similarity and difference in translation. Int J Corpus Linguist 9(2):167–193. https://doi.org/10.1075/ijcl.9.2.02bak

Bassnett S (1990) Translation, history and culture. Pinter Publishers, London

Bassnett S, Trivedi H (1998) Introduction. In: Bassnett S, Trivedi H (eds.) Postcolonial Translation: Theory and Practice. Routledge, London and New York, pp. 1–18

Bassnett S (2014) Translation. Routledge, London

Bednarek M (2006) Evaluation in Media Discourse: Analysis of a Newspaper Corpus. Continuum, London

Bednarek M, Caple H (2012) News discourse. Continuum, London

Benjamin W (2000) The task of the translator. In: Venuti L (ed) The translation studies reader. Routledge, London, pp 15–24

Bennett K (2016) Censorship, indirect translations and non-translation: the (fateful) adventures of Czech literature in 20th-century Portugal. Translator 22(1):120–122. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.1218.5686

Bell A (1991) The language of news media. Blackwell, Oxford

Berman A (2009) Toward a translation criticism: John Donne. Massardier-Kenne F (ed. and trans.). Kent State University Press, Kent

Borodo M (2015) Multimodality, translation and comics. Perspectives 23(1):22–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2013.876057

Breeze R (2017) Tired of nice people? An appraisal-based approach to Trump’s dichotomies. Cult, Leng Y Represent 18:7–25. https://www.e-revistes.uji.es/index.php/clr/article/view/2714

Brône G, Oben B (2015) InSight Interaction: a multimodal and multifocal dialogue corpus. Lang Resour Eval 49:195–214. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10579-014-9283-2

Carl M (2022) An enactivist-posthumanist perspective on the translation process. In: Halverson SL, García ÁM (eds) Contesting epistemologies in cognitive translation and interpreting studies. Routledge, New York, pp 176–189

Catford C (1965) A linguistic theory of translation. Oxford University Press, New York

Chen Y (2011) The ideological construction of solidarity in translated newspaper commentaries: context model and intersubjective positioning. Discourse Soc 22(6):693–722. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926511411695

De Sutter G, Lefer M-A (2020) On the need for a new research agenda for corpus-based translation studies: a multi-methodological, multifactorial and interdisciplinary approach. Perspectives 28(1):1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2019.1611891

Even-Zohar I (1978) Papers in historical poetics. Porter Institute for Poetics and Semiotics, Tel Aviv

Fantinuoli C, Zanettin F (2015) Creating and using multilingual corpora in translation studies. In: Fantinuoli C, Zanettin F (eds) New directions in corpus-based translation studies. Language Science Press, Berlin, pp 1–11

Garcia I (2009) Beyond translation memory: computers and the professional translator. J Spec Transl 12:199–214. https://jostrans.soap2.ch/issue20/art_osullivan.php

Hermans T (1985) The manipulation of literature (Routledge Revivals): studies in literary translation. Croom Helm Ltd, Kent

House J (2014) Translation quality assessment: past and present. In: House J (ed.), Translation: a multidisciplinary approach. Palgrave Macmillan, London, pp. 241–264

Hu K (2016) Introducing corpus-based translation studies. Springer, Berlin

Hyland K (2004) Disciplinary discourses: social interactions in academic writing. University of Michigan Press, Michigan

Kaindl K (2013) Multimodality and translation. In Millán C, Bartrina F (eds.) The Routledge handbook of translation studies. Routledge, London, pp. 257-269

Koller W (1992) Einführung in die Übersetzungswissenschaft. Quelle & Meyer, Heidelberg

Kotze H (2019) Converging what and how to find why: an outlook on empirical translation studies. In: Vandevoorde L, Daems J, Defrancq B (eds.) New empirical perspectives on translation and interpreting. Routledge, New York, pp. 331–370

Kress G (2020) Transposing meaning: translation in a multimodal semiotic landscape. In: Boria M, Carreres Á, Noriega-Sánchez M, Tomalin M (eds.) Translation and multimodality: beyond words. Routledge, London, pp. 24–48

Kruger H, De Sutter G (2018) Alternations in contact and non-contact varieties: reconceptualising that -omission in translated and non-translated English using the MuPDAR approach. Transl Cogn Behav 1(2):251–290. https://doi.org/10.1075/tcb.00011.kru

Kruger H (2019) That again: a multivariate analysis of the factors conditioning syntactic explicitness in translated English. Across Lang Cult 20(1):1–33. https://doi.org/10.1556/084.001

Laviosa S (2021) Corpus-based translation studies: theory, findings, applications. Brill Academic Publishers, Leiden

Lefevere A (1992) Translation, rewriting and the manipulation of literary fame. Routledge, London

Li D, Zhang C, Liu K (2011) Translation style and ideology: a corpus-assisted analysis of two English translations of Hongloumeng. Lit Linguist Comput 26(2):153–166. https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqr001

Liu H, Fang Y (2017) The principle of faithfulness and stylistic variation in poetry translation: a case study of three translated Stray Birds. J Zhejiang Univ (Humanit Soc Sci) 47(4):89–103. https://doi.org/10.3785/j.issn.1008-942X.CN33-6000/C.2016.09.091

Liu QY, Ang LH, Waheed M, Kasim ZM (2022) Appraisal theory in translation studies—a systematic literature review. Pertanika J Soc Sci Humanit 30(4):1589–1605. https://doi.org/10.47836/pjssh.30.4.07

Lu S (2013) Aesthetic values in literary translation: Zhang’s versus Dong’s version of David Copperfield in Chinese. Across Lang Cult 14(1):99–121. https://doi.org/10.1556/Acr.14.2013.1.5

Ma HJ (2009) On representing aesthetic values of literary work in literary translation. Meta 54(4):653–668. https://doi.org/10.7202/038897ar

Macken L, Prou D, Tezcan A (2020) Quantifying the effect of machine translation in a high-quality human translation production process. Informatics 7(2):12. https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics7020012

Malamatidou S (2018) Corpus triangulation: combining data and methods in corpus-based translation studies. Routledge, London

Martin JR (2000) Beyond exchange: appraisal systems in English. In: Hunston S, Thompson G (eds) Evaluation in text: authorial stance and the construction of discourse. Oxford University Press, New York, pp 142–175

Martin JR, White PRR (2005) The language of evaluation: appraisal in English. Palgrave Macmillan, New York

Mastropierro L (2018) Corpus stylistics in heart of darkness and its Italian translation. Bloomsbury, London

Mellinger CD, Hanson TA (2017) Quantitative research methods in translation and interpreting studies. Routledge, London

Mellinger CD, Hanson TA (2022) Research Data. In: Zanettin F, Rundle C (eds.) The Routledge handbook of translation and methodology. Routledge, London, pp 307–323

Mihalache I (2021) Human and non-human crossover: Translators partnering with digital tools. In Desjardins R, Larsonneur C, Lacour P (eds.) When translation goes digital: case studies and critical reflections. Palgrave Macmillan, New York, pp 19–43

Munday J (2017) Engagement and graduation resources as markers of translator/interpreter positioning. In: Munday J, Zhang M (eds) Discourse analysis in translation studies. John Benjamins, Amsterdam, pp 83–98. https://doi.org/10.1075/bct.94.05mun

Munday J (2012a) Evaluation in translation: critical points of translator decision-making. Routledge, London

Munday J (2012b) New directions in discourse analysis for translation: a study of decision-making in crowdsourced subtitles of Obama’s 2012 State of the Union speech. Lang Intercult Commun 12(4):321–334. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2012.722099

Mus F (2021) Translation and plurisemiotic practices: a brief history. J Spec Transl 35:2–14. https://www.jostrans.org/issue35/art_mus.php

Nida EA (1964) Toward a science of translating. Brill Academic Publishers, Leiden

Nida EA, Taber CR (1969) The theory and practice of translation. Brill Academic Publishers, Leiden

Nord C (1997) Translating as a purposeful activity: functionalist approaches explained. St Jerome Publishing, Manchester

Oakes M, Ji M (2012) Quantitative methods in corpus-based translation studies: a practical guide to descriptive translation research. John Benjamins, Amsterdam

O’Brien S (2012) Cognitive explorations of translation. Bloomsbury Publish, London

O’Sullivan C (2013) Multimodality as challenge and resource for translation. J Spec Transl 20:2–14. https://jostrans.soap2.ch/issue20/art_osullivan.php

O’Thomas M (2017) Humanum ex machina: translation in the post-global, posthuman world. Target 29(2):284–300. https://doi.org/10.1075/target.29.2.05oth

Pan L (2015) Ideological positioning in news translation: a case study of evaluative resources in reports on China. Target 27(2):215–237. https://doi.org/10.1075/target.27.2.03pan

Ping Y, Wang K (2024) Unveiling ideological shifts in news trans-editing: a critical narrative analysis of English and Chinese narratives on the 2014 Hong Kong protests. Journal of Language and Politics. https://doi.org/10.1075/jlp.22114.pin

R Core Team. 2023. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna

Reah D (2002) The language of newspapers. Routledge, London

Reisigl J, Wodak R (2009) The discourse-historical approach (DHA). In Reisigl J, Wodak R (eds.) Methods of critical discourse analysis. Sage, London, pp 87–121

Reiss K, Vermeer HJ (1984) General foundations of translation theory. Niemeyer, Tubingen

Saldanha G (2011) Translator style: methodological considerations. Translator 17(1):25–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/13556509.2011.10799478

Saldanha G, O’Brien S (2013) Research methodologies in translation studies. Routledge, London and New York

Schäffner C (2010) Cross-cultural translation and conflicting ideologies. In: Muñoz-Calvo M, Buessa-Gómez C (eds) Translation and cultural identity: selected essays on translation and cross-cultural communication. Cambridge Scholars, Cambridge, pp 107–128

Semino E, Short M (2004) Corpus Stylistics: Speech, writing and thought presentation in a corpus of English writing. Routledge, London

Shreve GM, Angelone E (2010) Translation and cognition. John Benjamins, Amsterdam, Philadelphia

Tymoczko M (2007) Enlarging translation, empowering translators. St. Jerome, London

van Dijk TA (1988) News as discourse. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale, New Jersy

van Dijk TA (2009) News, discourse, and ideology. In: Wahl-Jorgensen K, Hanitzsche T (eds.) The handbook of journalism studies. Routledge, New York, pp 191–204

Venuti L (1994) The translator’s invisibility: a history of translation. Routledge, London

Wang G (2007) Evaluation in translation of political news discourse: a news report on the Diaoyu Islands Dispute in The Washington Post and its translation in Reference News. Foreign Lang Educ 38(3):34–39. https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTotal-TEAC201703009.htm

Wang Z, Zhang Q (2014) How disputes are reconciled in a Chinese courtroom setting: from an appraisal perspective. Semiotica 201:281–298. https://doi.org/10.1515/sem-2014-0020

Wheatley JK (2014) Chinese verbs & essentials of grammar. McGraw Hill, New York

White PR (2006) Evaluative semantics and ideological positioning in journalistic discourse – a new framework for analysis. In: Lassen I (ed) Mediating ideology in text and image: ten critical studies. John Benjamins, Amsterdam, pp 37–69

Winters M (2008) F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Die Schönen und Verdammten: a corpus-based study of speech-act report verbs as a feature of translators’ style. Meta 52(3):248–258. https://doi.org/10.1080/10228190408566215

Wu G, Zhang H (2015) Translating political ideology: A case study of the Chinese translations of the English news headlines concerning South China Sea disputes on the website of www.ftchinese.com. Babel 61(3):394–410. https://doi.org/10.1075/babel.61.3.05gua

Xinhua News Agency (2020) UK publishes controversial Brexit bill amid growing anger from Brussels. http://en.people.cn/n3/2020/0910/c90000-9758836.html

Zanettin F, Saldanha G, Harding SA (2015) Sketching landscapes in translation studies: a bibliographic study. Perspectives 23(2):161–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2015.1010551

Zhang M (2013) Stance and mediation in transediting news headlines as paratexts. Perspectives 21(3):396–411. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2012.691101

Zheng B, Yu J, Zhang B, Shen C (2023) Re-conceptualizing translation and translators in the digital age: YouTube comment translation on China’s Bilibili. Transl Stud 16(2):297–316. https://doi.org/10.1080/14781700.2023.2205423

Acknowledgements

We express our heartfelt gratitude to Dr. Fu Chen (Shanghai Normal University) for his assistance with the multifactorial analysis of this study. This work was supported by the Major Project of the National Social Science Fund of China under Grant 20&ZD140 and the Shanghai Social Science Planning Project (General Project) under Grant 2020BYY003.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Guofeng Wang was responsible for the research design, and both Guofeng Wang and Yihang Xin contributed to the methodology, data collection, analysis, and writing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, G., Xin, Y. An analytical framework for corpus-based translation studies. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 1709 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04250-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04250-4