Abstract

Amidst global demographic shifts, China’s negative population growth since 2022 underscores the urgent need for population-adaptive public service equilibrium. This study assesses the coupling coordination degrees between population and public service (P-PS CCD) across 1733 Chinese counties for the years 2000, 2010, and 2020, employing the Geographical Detector Model (GDM) to examine influencing factors. The findings reveal consistently low P-PS CCD levels, indicating a delayed response of public service systems to population trends and significant spatial disparities influenced substantially by administrative factors. This research offers valuable insights for countries and regions experiencing or about to experience similar population changes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the drastic changes in global population size and structure, particularly the emergence of population declines in some countries, achieving equilibrium between public service supply and demand has become an increasingly urgent global challenge (Wu et al., 2022). Policymakers and researchers must seek new approaches to ensure the effective provision and equitable distribution of public services. Existing research has primarily focused on how policy innovations address challenges posed by population decline, showing a shift from income-maintenance social policies to proactive social policies aimed at human capital creation, mobilization, and preservation, with Japan and South Korea as notable examples (Lee and Kim, 2022). However, studies on policy implementation from the perspective of local government action within hierarchical organizations remain insufficient. Therefore, this study systematically examines China as a case, providing a unique perspective and valuable case study on how local governments worldwide might address the public service equilibrium crisis triggered by population decline.

China’s challenges in achieving public service equilibrium amid significant demographic changes are distinct from those faced by other countries and regions, including the following:

-

(1)

As one of the most populous countries globally, with over 1.4 billion people, or about 18% of the global population, China presents significant demographic shifts that make it an essential case (Hertog, 2023). China has recently entered a new era of population decline: in 2022, its total population dropped by 8.5 million compared to 2021, with a natural growth rate of −0.60‰Footnote 1, marking the first time in 61 years that China’s natural growth rate has led to a population decrease due to intrinsic population inertia. This trend continued in 2023, with a further reduction of 20.8 million people and a natural growth rate of −1.48‰Footnote 2, signaling a sustained and intensified population decline. The United Nations (2024) projects that from 2024 to 2054, China’s population could decrease by 204 million, followed by Japan and the Russian Federation, with declines of 21 million and 10 million, respectively. The challenges to public service equilibrium brought about by China’s dramatic population changes are distinct from those faced by other countries and regions.

-

(2)

China implemented a strongly government-guided population policy, which contributed to the sharp drop in fertility rates in the 1970s and the more gradual declines in the 1980s and 1990s (Zhang, 2017).

-

(3)

China’s urbanization process, which favors large and medium-sized cities, has resulted in significant population and structural changes in most counties. Since the 1990s, due to rural-to-urban migration, many counties have experienced a decline in permanent residents, compounded by persistently low fertility rates. This has resulted in significant changes in both the population size and structure in most counties. On the other hand, the public service resource allocation based on the dual urban–rural household registration system has created even greater challenges for supply capacity in these counties (Xu et al., 2022).

-

(4)

China is a unitary state where the central government is responsible for policy formulation, while local governments are in charge of implementation, ensuring policies are suited to local conditions (Deng and O’Brien, 2013). Under this vertical accountability framework, local governments act as agents of the central government, primarily aiming to meet the assessment requirements of higher authorities through the achievement of bureaucratic goals. This arrangement limits local governments’ fiscal autonomy, thereby reducing their incentives to improve public services (Eaton and Kostka, 2014). Therefore, local governments play a central role in the public service supply and managing equilibrium in China. Their fiscal capacity and governance efficiency directly impact the quality and accessibility of public services, especially amid demographic changes. For instance, how local governments adapt to issues such as population aging and a shrinking workforce through fiscal adjustments and policy innovations is a key factor in ensuring public service equilibrium.

Thus, in exploring the challenges of global public service equilibrium, China’s case offers valuable insights not only because of its unique population size and structure but also due to its complex hierarchical governance and public service policies. It provides global researchers with valuable experience, particularly in optimizing local government functions and improving public service financial security policies to address the challenges of public service equilibrium.

Public service equilibrium is a fundamental component of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (United Nations, 2015), and governments worldwide have been actively seeking solutions to achieve it. Despite significant progress, current research on public service equilibrium still presents two main limitations. First, existing studies have primarily defined public service equilibrium as the balance of public service levels in a single dimension, focusing mainly on the driving forces of public service equilibrium from the perspective of economic development (Deng et al., 2022). Second, studies that consider population dynamics in relation to public services tend to treat the population merely as a factor influencing the allocation of public service resources. Demographic research explores how public services impact population mobility and urban settlement, covering topics like educational equity for migrant children, public service support for urban integration, housing provision for various migrant types (e.g., rural-to-urban, small-to-large city, and peripheral-to-central migrations), and barriers to elderly access, including those caused by the digital divide (Xu and Wu, 2022; Lu and Lou, 2024; Safarov, 2021).

Regarding research methods, the Gini coefficient (Xu et al., 2022) and Theil index (Li et al., 2023) are primarily used to measure the equilibrium of a single system. Additionally, some scholars focus on constructing spatiotemporal accessibility models for public services using geographic information system (GIS) methods to evaluate the spatial allocation of public service resources, identify spatial disparities, or achieve spatial equilibrium in fields such as education (Zhang et al., 2023), rural healthcare services (Ding et al., 2021), and other related areas.

In summary, existing studies have not adequately addressed the theoretical concept of supply-demand equilibrium between public services and population characteristics (Christensen et al., 2020). Moreover, there is a lack of systematic empirical analysis on how demographic changes impact the balance between public service supply and demand. The exploration of factors driving public service equilibrium has largely focused on economic development (Deng et al., 2022), while overlooking the governance perspective, which is intrinsic to the public nature of services provided by local governments, such as the role of administrative hierarchy (Jia et al., 2021) and fiscal self-sufficiency (Chen et al., 2018).

This study aims to construct a conceptual framework for understanding the supply-demand equilibrium of public services in the context of population dynamics (Fig. 1). By conducting an in-depth analysis of 1733 counties in China for the years 2000, 2010, and 2020, this study employs a Coupling Coordination Degree Model (CCDM) and Geographic Detector Model (GDM)to address three key questions: (1) How can public service equilibrium be measured under population changes? (2) What are the spatial and temporal characteristics of public service equilibrium in China? (3) What factors influence public service equilibrium at the county level?

Based on the background of county-level public service provision in the context of China's negative population growth, this paper first constructs an equilibrium framework for population and public services using a coupling coordination model. Subsequently, spatial correlation analysis is employed for spatio-temporal analysis. Finally, a geographical detector model is utilized to conduct an analysis of influencing factors.

Conceptual framework of population-adapted public service equilibrium

Local government governance: public service supply as a response to population demand

The fiscal decentralization theory suggests that local governments, being closer to their citizens, can efficiently deliver public goods compared to a central government (Oates, 2005). The allocation of local public services is only effective when it aligns with the needs of residents within their jurisdiction, facilitating optimal resource allocation and maximizing societal welfare (Musgrave and Peacock, 1958). Tiebout (1956) using the framework of the “voting with feet” theory, established a connection between population and the governance effectiveness of different regions. Individuals express their preferences for local government governance and public service supply through their choice of residence. This theory emphasizes that individual choice behaviors directly and significantly influence the response of local governments to public services. Oates (1969) highlighted in his research that individual migration behavior can be seen as a choice regarding local government taxation and the level of public services, prompting adjustments by local governments in these aspects. Similarly, Roback’s (1982) study suggested that people consider the quality of local public services when choosing a place of residence, which tends to influence the assessment of local governance effectiveness. Thus, the provision of public services influences regional population dynamics, while population dynamics also influence regional public service supply (Dahlberg et al., 2011).

Specifically, changes in population size result in variations in the overall demand for public services, while alterations in population structure generate heterogeneous demands for public services. Within a regional context, the growth and in-migration of the population lead to increased demand for public services, consequently raising the costs and burdens associated with regional public service supply (Ladd, 1992). Trends in population aging and the development of an elderly population create higher demands for essential healthcare and social security (Valkama and Oulasvirta, 2021). Changes in the number of school-age children affect the demand for basic educational facilities and investments. The proportion of different age groups determines the overall population dependency ratio, influencing the societal support burden. This, in turn, affects both financial burdens and the demand for basic public services (Notestein, 1950). Furthermore, groups with higher education levels and skills tend to exhibit a greater demand for the quality of public services. Throughout this process, governments must understand changes in population size and structure and adjust fiscal expenditures to meet public service demands, considering political legitimacy, government functions, and social development. We argue that disparities in the provision of public services by various local governments arise from factors related to local resource endowments, baseline conditions, and development situations, as well as the operation of the entire political system. Administrative systems, including government assessment incentive mechanisms and supervisory accountability mechanisms, contribute to differential behavior among local governments, resulting in variations in public service supply behaviors and structures across regions.

Local public finance: population factors supporting the expenditure capacity of public services

From the perspective of welfare economics theory, labor, as a factor contributing to economic growth, can increase local tax revenue (Heckman, 2006), which provides stronger support for local public finance and enables local governments to better meet the demand for public services (Hanushek and Woessmann, 2012). According to the theory of public choice (Buchanan and Tullock, 1965), demographic factors, especially the level of population education, are considered crucial in influencing local government expenditures on public services. Well-educated populations are more likely to participate in the decision-making process and express higher demands for public services such as education and healthcare. Meeting these demands enables local governments to enhance their capacity to expand public services.

Since the 18th National Congress of the Communist Party of China (CPC), the country has shifted its focus from prioritizing economic development to constructing a “Five-in-One” governance pattern, consisting of economic, political, cultural, social, and ecological civilization construction. The governance concept of sustainable development integrates the three dimensions of economy, environment, and society (Purvis et al., 2019). Moreover, the 20th National Congress Report of the CPC further emphasizes the imperative to “strengthen the equilibrium of public services.” Therefore, the focus of local government governance has extended beyond economic development to also consider the supply of public services, recognizing the population as a crucial factor in the local government’s capacity to provide public service (Zhu, 2017).

In summary, the population system and the public service system are interconnected and mutually influential, with public service equilibrium requiring adaptation in both systems. In the context of fiscal decentralization of public services in China, county-level governments are de facto providers of regional public service resources. On the one hand, in terms of the political legitimacy and functional fulfillment of local government governance, they must respond to the changing demands of the population through the effective supply of public services. On the other hand, in terms of the fiscal capacity of local governments, the size, structure, and quality of the population, while exerting pressure on service provision, also serve as elements supporting local public service resources. This establishes the fundamental conceptual framework of our study (Fig. 2).

Methodology

The coupling coordination degree model (CCDM)

The coupling coordination degree model explores interactive relationships and analyzes coordinated development between two or more systems. The coupling coordination degree is used to measure the extent to which different factors or systems constitute a mutually coordinated benign coupling (Bryan et al., 2018). The formula is as follows:

Where C represents the coupling degree between the population and public service systems, with a value range of [0, 1]. A higher C indicates stronger interaction and coupling. (Fang et al., 2019). The P-PS Coupling Degree (P-PS CD) is categorized into four types (Jiang et al., 2017) (Table 1), based on comprehensive evaluation values of both systems. U1 and U2 represent the scores of the public service and the population system, respectively. T is the comprehensive coordination index (P-PS T), with α = β = 0.5 to reflect the equal importance of both systems (Yin et al., 2015). P-PS T reflects the overall coordination level between the two systems. D is the coupling coordination degree (P-PS CCD), reflecting whether the systems mutually promote or constrain each other. It’s divided into four categories and ten levels (Table 2) based on previous studies (Liao, 1999).

Moran’s I

Moran (1950) introduced the global Moran’s I as a significant indicator for testing spatial correlation among attribute values of neighboring spatial points. By analyzing changes in attribute values of a unit compared to its neighbors, spatial clustering phenomena can be identified. In this study, we employ Moran’s I to detect spatial clustering in P-PS CCD among Chinese counties. After normalization, the Moran’s I value is scaled to the range [−1, 1]. A positive Moran indicates spatial clustering, with higher values indicating a stronger correlation. A Moran’s I of 0 suggests random spatial distribution. The formula is as follows:

Getis‑Ord Gi*

Getis-Ord Gi* is employed to identify statistically significant high (hot spots) and low (cold spots) values in spatial clusters. It measures attributes of similarity and dissimilarity between geographic units and their surroundings. Positive Z scores indicate tighter clustering of high values (hot spots), while negative Z scores indicate tighter clustering of low values (cold spots). In this study, Getis-Ord Gi* is employed to analyze spatial clustering characteristics of P-PS CCD in Chinese counties, illustrating spatiotemporal distribution patterns and evolutionary trajectories of hot spots and cold spots. The formula is as follows:

Geographical detector

The geographic detector model detects spatial heterogeneity and its influencing factors by exploring consistency in spatial distribution patterns between dependent and independent variables. It measures the explanatory power of independent variables on the dependent variable. Independent variables are partitioned using the K-means clustering method in SPSS, and then imported into Geo-Detector software for detection. The formula is as follows (Song et al., 2020):

P-PS CCD is influenced by various factors from economic, social, and administrative dimensions. This study selects indicators including per GDP (X1), urbanization (X2), industrial structure (X3), urban–rural income gap (X4), population density (X5), fiscal self-sufficiency (X6), administrative level (X7), and province (X8) based on existing research (Cheng and Liu, 2023; Liu and He, 2019; Jia et al., 2021).

Establishment of an index system

Refer to the studies by Li et al. (2020), Xu et al. (2022), and Yang et al. (2021), from the three dimensions of Population Size, Population Structure, and Population Quality, the changes in the population system of Chinese counties were measured using seven indicators. The public services provided by Chinese county-level governments mainly include Public Education, Public Health, and Social Security. The changes in the county-level public service system in China were measured using four indicators. The entropy methodFootnote 3 was used to calculate the comprehensive scores of the population and public service systems for Chinese counties in the years 2000, 2010, and 2020 (Table 3).

Data source

In this study, the research unit is the county-level administrative division in China. As per the statistical table released by the China Administrative Divisions Information Query Platform on December 31, 2020, there are 2844 such administrative units.

Due to data completeness, population census years of 2000, 2010, and 2020 were chosen as research time nodes. Population data were sourced from the respective national population censuses, totaling 8885 samples. Public service system indicators were mainly from the “China County Statistical Yearbook” spanning 2000–2021, supplemented by statistical bulletins and yearbooks. Missing data were interpolated using panel data. After excluding counties with missing data, 6705 samples remained. Using 2020 administrative divisions as a reference, population and public service system samples were matched, resulting in 5541 samples. Due to administrative adjustments like mergers and district conversions, some units were excluded, leaving 1733 valid units across 28 provinces annually (Appendix 1-1Footnote 4). In total, 5199 samples were obtained over three years (Table 4).

Results

General characteristics of population system and public service system

Based on the Population and Public Service Index System detailed in Table 3, Comprehensive Scores for population and public service systems were calculated for 1,733 Chinese counties in 2000, 2010, and 2020 (Fig. 3). Key findings are as follows: (1) overall, the development level of the P system and PS system in Chinese counties is relatively low and exhibits a fluctuating trend over time. Among them, public health and population size show a decreasing trend, population structure exhibits a decreasing trend, social security shows an increasing–decreasing trend, and Public Education and Population Quality show a decreasing-increasing trend. (2) From 2000 to 2010, the decline in P system scores is primarily due to decreased population quality. The decrease in PS system scores is attributed to simultaneous declines in Public Education and Public Health, with a slight increase in Social Security. (3) Between 2010 and 2020, significant increases in comprehensive scores for both P and PS systems are observed, driven by improvements in Public Education and Social Security for both systems, along with Population Quality enhancements for the PS system. Overall, the PS system consistently lags behind the P system’s development throughout the study period.

A higher comprehensive score signifies a higher level of performance for the indicator. Among them, Public Education, Public Health, and Social Security are indicators of the public service system (PS), while Population Size, Population Structure, and Population Quality are indicators of the population system (PS).

Spatio-temporal characteristics of P-PS CCD

Based on the constructed P-PS CCDM, the mean scores of P-PS CD, P-PS T, and P-PS CCD were calculated for 1,733 county units in China across 2000, 2010, and 2020 (Fig. 4). Key findings are summarized as follows: (1) P-PS CD remains in a state of High Coupling, showing stability over time with three-year averages ranging from 0.953 to 0.956. Although slightly lower in 2000 compared to 2010 and 2020, it indicates strong mutual interaction and influence between P and PS systems. (2) P-PS T values are consistently moderate, with averages ranging from 0.13 to 0.152. Slightly lower in 2010 compared to 2000 and 2020, it suggests a relatively low level of comprehensive coordination between P and PS systems. (3) P-PS CCD indicates Slightly Unbalanced Development, with three-year averages ranging from 0.342 to 0.374. Temporal trajectory aligns with P-PS CD and P-PS T, showing a slight decrease in 2010 compared to 2000 and 2020. (4) I throughout 2000, 2010, and 2020, Chinese counties exhibit high correlation but poor coordination between P and PS systems, resulting in a consistently imbalanced state of P-PS CCD.

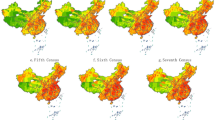

Further analyzing the distribution of P-PS CCD in 1733 county units in China for 2000, 2010, and 2020 (Figs. 5 and 6), the following observations emerge: (1) spatially, P-PS CCD follows a “Southeast high, Northwest low” trend, referencing the Hu Huanyong Line (China population comparison line). Counties in coordination states (dark-colored blocks) are concentrated to the east of the line, where population density is high, while counties in disorder states (light-colored blocks) span westward, particularly in the intermediate zone. (2) In 2000, 71.26% of counties scored between 0.3 and 0.5 on P-PS CCD, with the majority indicating Mild disorder in the (0.3, 0.4] range, accounting for 45.18%. (3) In 2010, 74.84% of counties scored between 0.2 and 0.4 on P-PS CCD, with the largest share still in the (0.3, 0.4] range, indicating Mild disorder at 43.45%. Notably, the (0.2, 0.3] range, indicating Moderate disorder, saw a significant increase, rising from 19.04% in 2000 to 31.39% in 2010, an increase of 214 county units. (4) In 2020, P-PS CCD scores ranged from 0.2 to 0.5. Compared to 2010, there was a slight reduction in counties in a state of disorder, particularly in those with scores indicating Moderate disorder or below, decreasing by approximately 12 percentage points. Counties in a coordinated state increased by 2.14 percentage points. (5) Noteworthy instances include one county (0.06%, Xinghua County under Taizhou City, Jiangsu Province) reaching an Intermediate coordination state with a P-PS CCD score of 0.73 in 2000. However, no counties reached this state in 2010 and 2020. Conversely, in 2020, there was an increase of one county (0.06%, Zanda County under Ali Region, Xizang) with an extremely disordered P-PS CCD score of 0.09, indicating an Extreme disorder state compared to 2000 and 2010.

To delve deeper into the disorder characteristics of the P and PS systems, scatter plots were generated for 1,733 county units in China across 2000, 2010, and 2020. The x-axis represents the score difference between the PS system and P system (PS-P SD), while the y-axis illustrates the P-PS CCD (Fig. 7): (1) In 2000, Chinese counties were concentrated in the PS-P SD range [−0.1, 0.1] and P-PS CCD range [0.2, 0.5], indicating a disordered state where the public service system lagged behind the population system. (2) In 2010, county distribution became more concentrated, particularly in the lower P-PS CCD range [0.2, 0.4]. Counties where the PS system lagged behind the P system increased by 51 compared to 2000. (3) In 2020, county distribution showed a dispersed pattern. Counties with high P-PS CCD [0.5, 0.7] and high PS-P SD difference [−0.6, 0.7], as well as counties with low P-PS CCD [0.1, 0.2] and low PS-P SD difference [0.1, 0.2], both increased. This suggests widening gaps in P-PS CCD between counties and further lag of the public service system in some areas. (4) Further analysis of the CCD between the population subsystem and the public service subsystem (Table 5) revealed that the CCD between the Population Structure (PS) subsystem and the Public Education (PE) and Public Health (PH) subsystems was significantly higher than other subsystems, remaining stable within the range (0.4, 0.6). (5) Changes in Population structure impacted county-level public service equilibrium, particularly evident in pressures from decreasing children population and surging aging population on adjustment of public service supply. CCD between the Children Population (CP) subsystem and Public Education (PE) subsystem averaged 0.407, 0.335, and 0.383 in 2000, 2010, and 2020 respectively, indicating a mild disorder state. AP-PH CCD averaged 0.432, 0.308, and 0.280 in the three years, showing a continuous decline and reaching a moderate disorder state in 2020. This suggests the lagging responsiveness of China’s county-level public services to changes in the aging population.

The coupling interaction between the public service system and the population system is a dynamic process. Accurately analyzing changes in coupling coordination over time reflects the interactive patterns of these systems at different periods. Comparing variations in P-PS CCD over two time intervals formed at three-time points (Fig. 8), we observe the following trends: (1) between 2000 and 2010, the P-PS CCD in China’s counties exhibited an overall declining trend nationwide. Counties experiencing Seriously Unbalanced Development Stages increased by 224 compared to 2000, mainly in North China, Northeast, and East China (Appendix 1–2). Counties in the Slightly Unbalanced Development Stage decreased by 153, mainly in North China and Northwest. Counties in a Barely Balanced Development Stage decreased by 71, mainly in East China, Central China, and Northeast. (2) Between 2010 and 2020, the overall P-PS CCD trend in China’s counties showed an upward trajectory, particularly in eastern regions, driven by enhanced public service levels. Counties experiencing Seriously Unbalanced Development Stages decreased by 206 compared to 2010, primarily in Southwest and North China. Counties in the Slightly Unbalanced Development Stage increased by 169, mainly in North China, Southwest, and Northwest. Counties in the Barely Balanced Development Stage increased by 37 compared to 2010.

In general, the P-PS CCD in Chinese counties during the years 2000, 2010, and 2020 was predominantly characterized by a Slightly and Seriously Unbalanced Development Stage, with fewer counties in a Barely Balanced Development Stage and none in a Superior balanced development Stage, indicating a disorder where the public service system lags behind the population system. Temporally, P-PS CCD declined from 2000 to 2010, followed by a slight improvement from 2010 to 2020. Spatially, significant differences were observed across Chinese counties, with a gradual decrease in P-PS CCD from eastern coastal to central and southern counties, then to northwestern counties, reflecting the “Southeast high, Northwest low” pattern along the Hu Huanyong Line.

Spatiotemporal correlation evolution

In the years 2000, 2010, and 2020, Moran’s I analysis confirmed significant spatial autocorrelation in P-PS CCD across Chinese counties, with coefficients falling within the [0.61, 0.66] range, indicating a clustered pattern (Table 6). Subsequent analysis using the Getis-Ord Gi* index classified China’s county-level P-PS CCD into various categories based on confidence levels of 99%, 95%, and 90%. The following observations were made (Fig. 9): (1) in 2000, there were 118 significantly cold spots in the P-PS CCD, (6.81%) mainly in western, southwestern, and northwestern regions, and 101 significantly hot spots (5.83%) mainly in eastern and central regions. (2) In 2010, 108 significantly cold spots (6.23%) were mainly in western, northwestern, southwestern, and northern regions, while 110 significantly hot spots (6.35%) were primarily in eastern and central regions. (3) In 2020, 112 significantly cold spots (6.35%) were mainly in western regions, with an increase in the northern region, while 110 significantly hot spots (6.46%) were mainly in eastern and central regions, with a decrease in the eastern region. (4) Regionally, significant hot spots decreased in the eastern region and increased in the southwestern region. Conversely, significantly cold spots increased in the northern region and decreased in the southwestern region.

Overall, significantly cold spots were mainly in northwestern, southwestern, and northern regions, while significantly hot spots were mainly in eastern, southwestern, and central regions, with other regions exhibiting a random distribution pattern. Spatially, there was a gradual evolution from significantly hot spots to random distribution areas from east to central regions, and a transition from random distribution areas to significantly high cold spots from central to western regions. Temporally, significantly cold spots spread from western to northeastern counties, while significantly hot spots diffused from eastern counties to central and southwestern counties.

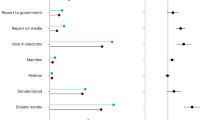

Analysis of influencing factors on the P-PS CCD

A geographical detector model was constructed to examine the influence of economic, social, and administrative factors on P-PS CCD. Results indicate that population density (X5), province (X8), fiscal self-sufficiency (X6), administrative level (X7), and urban–rural income gap (X4) are the primary influencing factors, ranked by impact. Their q-values range from 0.079 to 0.663, with population density (X5), province (X8), and administrative level (X7) showing stable influence. Fiscal self-sufficiency (X6) exhibits a “V”-shaped trend, initially decreasing then increasing, with its strongest impact observed in 2000. The urban–rural income gap (X4) initially strengthens in influence and then slightly diminishes over time. Per GDP (X1) and urbanization (X2) have minor impacts, while industrial structure (X3) shows no significant impact (Table 7).

In factor interaction detection, X3 was excluded due to its insignificant impact on P-PS CCD in Chinese counties. Additionally, X4 was not included in the interaction detection for the three years due to sample size differences. Furthermore, missing data for the X2 indicator in 2000 led to its exclusion from factor detection for that year. The results, shown in Table 8, indicate that for 2000, 2010, and 2020, the joint action of any two factors yielded q-values greater than individual factor actions. Interactions between factors showed either bi-factor enhancement or non-linear enhancement, indicating increased explanatory power for P-PS CCD spatial differentiation. Combining results for the three years, population density (X5) interaction with other factors significantly increased explanatory power, particularly with self-sufficiency (X6) and province (X8), resulting in indices exceeding 0.9, signifying strong impact on P-PS CCD spatial differentiation in Chinese counties.

Over the three years, the primary influencing factors for P-PS CCD in Chinese counties, ranked by impact, were population density, provincial affiliation, fiscal self-sufficiency, and administrative level. The industrial structure had no significant impact. Per capita GDP had a significant effect only in 2000. The urbanization rate had a weak effect, decreasing in intensity from 2010 to 2020. Among social factors, the impact of the urban–rural income gap fluctuated, while population density’s impact remained stable above 0.62. Fiscal self-sufficiency, administrative level, and provincial affiliation strongly influenced P-PS CCD spatial differentiation within administrative and social factors.

Discussion

The equilibrium of public services is a critical component of regional sustainable development. Previous research has primarily focused on the spatial equilibrium of public service levels from an economic development perspective and has overlooked the supply-demand equilibrium of public services interacting with population dynamics from the perspective of local governments. Our study reconceptualizes the equilibrium between public service supply and demand, and explores the application and empirical tests of fiscal decentralization theory and “voting with feet” theory in the context of public service equilibrium at the county level in China. Through in-depth analysis, we found that while fiscal decentralization theory anticipates that local governments would provide more efficient and equitable public services by being closer to the people, in reality, due to China’s political centralization (Jia et al. 2021) and performance assessment mechanisms primarily focused on GDP growth (Zhou, 2016), the initiative of local governments in improving public service supply is constrained (Wu et al., 2020). This finding indicates the need for further exploration of the applicability of existing theories under specific political-economic contexts. Additionally, our data analysis revealed that population aging and migration significantly impact public service demand, echoing the “voting with feet” theory, suggesting that dissatisfaction with public service quality may be expressed through migration.

This study offers innovations in three key areas:

First, it introduced a novel theoretical framework designed to address public service equilibrium in the face of demographic shifts, filling a gap in existing theories that primarily focus on a single public service system. Samuelson (1954) described the government’s public service function as the provision of public goods and services that meet public demand efficiently and effectively, highlighting that public service equilibrium involves the coupling and coordination of the public service supply subsystem and the population demand subsystem. As China enters an era of negative population growth, characterized by a declining proportion of the working-age population and a rapidly increasing elderly population, the burden of dependency has significantly intensified, leading to structural changes in public service demand. Based on this new context, we developed a conceptual framework for public service equilibrium that adapts to population changes, enabling a better assessment of the current state of public service supply-demand balance, identifying disparities, and addressing the challenges of achieving equilibrium amidst dynamic population shifts.

Second, we utilized a novel methodology, integrating quantitative and qualitative analyses using the geographic detector model (GDM) and the population-public service coupling coordination degree model (P-PS CCDM). Building on the notion that public service equilibrium involves the coupling and coordination of two subsystems, this research overcomes the limitations of previous methodologies that measured only a single system. We constructed the P-PS CCDM to explore the interactive relationships between the two subsystems and analyze their coordinated development. Furthermore, within the context of China’s vertically accountable public service supply system (Lu and Xue, 2011), county governments act as both identifiers of local public service demand and implementers of policies set by higher authorities. This multifaceted interaction affects their ability to improve equilibrium. By employing the GDM, we measured the explanatory power of independent variables on dependent variables and explored the interactions of multiple factors affecting public services.

Third, this research actively examines the complex relationships among local governance structures, fiscal policies, and public service equilibrium, offering actionable policy recommendations that contribute directly to enhancing public service supply and achieving equilibrium at the county level.

Since the implementation of the tax-sharing reform in China in 1994, the supply of public services at the county level has been governed by a framework of central-local decentralization, adhering to the principles of vertical accountability within bureaucratic organizations (Tan, 2014). This principle emphasizes that local governments must advance their initiatives in alignment with the policy goals set by the central government and are subject to assessment by central authorities (Li and Weible, 2021). Theoretically, fiscal decentralization should incentivize local governments to increase their financial investment in public service provision, thereby improving the efficiency and quality of services (Barro, 1991). However, China’s fiscal decentralization is characterized by significant political centralization (Blanchard and Shleifer, 2001). The evaluation systems focused on rigid indicators such as GDP growth effectively encourage county governments to engage in horizontal competition for economic development (Zhou, 2006), which in turn weakens their motivation to respond to local public service needs and leads to crowding-out effects in expenditures on education, health, and social welfare (Jin et al., 2005). This results in a disbalance between county-level public service systems and population systems, where public service systems lag behind demographic changes. Moreover, the Chinese central government introduced a policy of balanced intergovernmental fiscal transfers in 1995, aimed at enhancing regional equity in public services by compensating for disparities in capacity. However, the factors used to allocate transfer payments imply an inverse relationship between the scale of general transfer payments and the level of economic development, which may negatively impact local economic growth and reduce the capacity of local governments to provide public services (Yin and Zhu, 2012). Consequently, the equilibrium of public services in China continues to exhibit a pattern of higher levels in the southeast and lower levels in the northwest, with well-balanced counties clustering in the southern regions and poorly balanced counties concentrated in the west. Subsequently, in 2006, the Sixth Plenary Session of the 16th Central Committee of the CPC explicitly proposed the goal of “building a service-oriented government and strengthening social management and public service functions.” Addressing the shortcomings in public services and promoting the equalization of public services become key tasks for governments at all levels. The central government gradually increased assessment indicators related to people’s livelihoods, such as environmental protection, education, and poverty alleviation, thereby encouraging local governments to focus on the development of public services. Since the 18th National Congress, China has vigorously advanced the fight against poverty, implemented rural revitalization strategies, and promoted urban–rural integration to achieve the goal of equalizing public services between urban and rural areas. The report of the 20th National Congress continued to emphasize the importance of “enhancing the balance and accessibility of public services.” After a prolonged period of top-down reform of the public service supply side, the level of public services in China has significantly improved, which is a major reason for the slight improvement in public service balance at the county level between 2010 and 2020.

Improvements in regional public service equilibrium under the fiscal decentralization framework face various obstacles. Studies analyzing post-decentralization public service equilibrium in Ghana advocate for strengthened vertical accountability to prevent capture by local elites (Dick-Sagoe, 2020). Investigations in Indonesia suggest that the key lies in increasing discretionary powers to incentivize proactive behavior by local governments (Lewis, 2023). Meanwhile, the UK actively attempts to upgrade the policy agenda for public service equilibrium to enhance decision-making efficiency (Fransham et al., 2023). However, the design of public service policies primarily occurs at the highest levels of central government, with local governments mainly responsible for policy implementation and subject to stringent vertical accountability performance assessments (Li and Weible, 2021). Within this central-local governance framework, the equilibrium of public services at the county level in China is primarily hindered by significant disparities in fiscal capacities among county governments and a lack of sufficient vertical incentives.

Nevertheless, with the transformation of China’s central government’s “Five-in-One” strategy, reforms for public service equilibrium continue to progress. Governments at all levels are actively exploring ways to address the inefficiency of fiscal resources. Under the framework of new public management (NPM), efforts are made to encourage social organizations’ participation in public service supply through government procurement of public services (Feuchtwang, 2023), collaborations with private capital (Lapuente and Van de Walle, 2020), and advocacy for citizen cooperative production supply (Allen et al., 2020). However, these initiatives face resource constraints and moral dilemmas, similar to the high turnover rate of elderly care professionals in Finland, which is also present in China (Ring et al., 2024). As population aging advances rapidly, the contradiction between the shortage of human resources in China’s public services and the dramatic increase in demand will become more pronounced. Exploring new approaches to address this pressing issue is imperative.

Moreover, there are active endeavors to empower local governments with digital technology for the identification of public service demands and precision provision (Liu and Qi, 2022). Indeed, China is actively promoting smart community elderly care services (Chen et al., 2023), akin to electronic medical policies in Italy, Finland, and Sweden, which provide health assessments and care for the elderly (Valokivi et al., 2023). However, these efforts also face challenges such as the digital divide and increased administrative burdens (Christensen et al., 2020). Addressing these issues requires further tracking and in-depth research.

Finding and policy implications

In this study, we collected population and public service data from 1733 counties in China for the years 2000, 2010, and 2020, and constructed P-PS CCDM, spatial autocorrelation, and geographical detector models to investigate the spatiotemporal patterns and driving factors of P-PS CCD in Chinese counties. The study addressed the characteristics and influencing factors of public service county equilibrium under population changes, yielding the following conclusions:

-

(1)

Overall poor equilibrium: during the study period, the P-PS CCD in most counties was mainly at a mild or severe imbalance stage, with a few counties reaching a barely balanced stage and none achieving an optimal equilibrium. The primary cause of this imbalance was the lag in public service systems relative to population systems, especially under the pressure of a declining young population and a rapidly increasing elderly population, indicating challenges in addressing population aging.

-

(2)

Improving temporal trends: from 2000 to 2010, the P-PS CCD showed a declining trend, but there was a slight improvement from 2010 to 2020, attributed to the enhancement of county-level public service standards.

-

(3)

Significant spatial differences: the spatial distribution pattern of P-PS CCD across Chinese counties displayed a general trend of “higher in the east, lower in the northwest,” with significant clustering and stable spatial disparities. Coldspot areas were mainly located in the western regions, with an expanding trend towards northeastern counties. The proportion of coldspot areas initially decreased and then increased, with a notable rise in the number of coldspot counties in northern regions. Conversely, hotspot areas were consistently distributed in central and southern China, with a continuous increase in proportion, while the eastern counties, despite being the most numerous, showed a declining trend.

-

(4)

The significant impact of administrative factors: administrative factors were the main drivers affecting P-PS CCD during the study period, with substantial disparities in equilibrium across counties of different administrative levels and provinces. The combined effects of these two factors had a stronger influence on the spatial differentiation of P-PS CCD.

-

(5)

Notable interaction effects of social factors: among social factors, the impact of the urban–rural income gap fluctuated, while the influence of population density remained above 0.62 throughout. The interaction of population density with fiscal self-sufficiency and provincial affiliation had a significant impact on equilibrium differences across counties, indicating the scale effect of resource allocation in the context of public service supply.

-

(6)

Fiscal self-sufficiency as the key economic factor: fiscal self-sufficiency showed a significant impact on county-level equilibrium differences, following a “V” shaped trend—initially declining and then rising. Industrial structure did not exhibit a significant effect, while per capita GDP only had a significant impact in the year 2000. The influence of the urbanization rate was relatively weak and declined in intensity from 2010 to 2020.

Therefore, it is evident that China’s top-down “one-size-fits-all” public service supply policy makes it challenging for local governments to respond promptly to the “differentiated” public service needs arising from population changes at the county level, hindering the improvement of public service equilibrium. Therefore, (1) while continuing to improve the public service capacities of local governments in central and western regions through policies such as transfer payments and targeted support, performance evaluation indicators for public services that are accessible to urban and rural residents should be supplemented to address the policy implementation deviations resulting from vertical accountability; (2) the drastic changes in population size, structure, and quality at the county level have heightened the heterogeneous demand and scale pressure for public services. Social forces should be encouraged to supplement the supply of public service resources, increasing flexibility in responding to public service demand; and (3) the poor public service equilibrium in central and western counties, marked by both insufficient quantity and structural deficiencies, faces issues such as the care of elderly in relatively poor families under the trend of rural population outflow and the rising cost of family education under the development concept of “education-driven urban development.” These issues of public services equity require urgent and targeted policy responses.

Limitations and research outlook

The dataset used in this study comprises cross-sectional data from the years 2000, 2010, and 2020, rather than time-series data spanning consecutive years. As a result, it is not suitable for effectively predicting the trends in public service equilibrium in Chinese county-level areas under future significant population changes. Additionally, it cannot straightforwardly address the variations in public service equilibrium among different types of counties in China (e.g., population shrinking county, population stable county, and population expanding county). Future research could utilize continuous time-series data to enable more detailed analyses by category.

In terms of local government actions to balance public service supply and demand, two directions for future exploration are as follows:

Achieving public service equilibrium requires precise identification of needs. Future research could explore the adoption of digital technologies and the innovation processes of public services within the governance contexts of China and other developing countries. This may enhance our understanding of how institutional environments influence the balance between technology and public services.

Realizing public service equilibrium depends on strengthening local governance capabilities. Future studies could investigate a conceptual framework for local government governance capacity that explains public service equilibrium, focusing on pathways for capacity improvement under different governance structures. For instance, this could involve cultivating social organizations to supply public services and guiding rural self-organized mutual assistance for elderly care to enhance county-level local governments’ resource integration capabilities. Additionally, horizontal competition could incentivize learning and innovation to improve county-level government allocation capabilities. These efforts would deepen our understanding of local government actions in the context of public service equilibrium.

Data availability

The raw data are protected and are not available due to data privacy. The processed data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Notes

Data source: “Statistical Bulletin of the People’s Republic of China on National Economic and Social Development 2022” http://www.stats.gov.cn/xxgk/sifb/zxfb2020/202302/t20230228 1919001.html

Data source: “Official Website of the National Bureau of Statistics of China” https://www.stats.gov.cn/xxgk/jd/sjjd2020/202401/t20240118_1946711.html

The entropy method is an objective evaluation approach that determines objective weights based on the variability of indicators. For a certain indicator, if the entropy is smaller, it indicates a greater degree of variation in the indicator values, providing more information and playing a more significant role in the comprehensive evaluation, thus having a larger weight (Liu et al., 2022).

See Appendix 1 for relevant place names and locations later in this paper.

References

Allen B et al. (2020) Does citizen coproduction lead to better urban services in smart cities projects? An empirical study on e-participation in a mobile big data platform. Gov Inf Q 37(1):101412. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2019.101412

Blanchard O, Shleifer A (2001) Federalism with and without political centralization: China versus Russia. IMF staff Pap 48(Suppl 1):171–179. https://doi.org/10.2307/4621694

Bryan BA et al. (2018) China’s response to a national land-system sustainability emergency. Nature 559:193–204. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0280-2

Buchanan JM, Tullock G (1965) The calculus of consent: logical foundations of constitutional democracy, vol 100. University of Michigan press, Michigan

Chen H, Zhang Y, Wang L (2023) A study on the quality evaluation index system of smart home care for older adults in the community—based on Delphi and AHP. BMC Public Health 23:411. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15262-1

Chen T et al. (2018) Inter-provincial inequality of public health services in China: the perspective of local officials’ behavior. Int J Equity Health 17(1):1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-018-0827-8

Cheng K, Liu S (2023) Does urbanization promote the urban–rural equalization of basic public services? Evidence from prefectural cities in China. Appl Econ. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2023.2206625

Christensen J et al. (2020) Human capital and administrative burden: the role of cognitive resources in citizen‐state interactions. Public Adm Rev 80(1):127–136. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13134

Christensen T, Yamamoto K, Aoyagi S (2020) Trust in local government: service satisfaction, culture, and demography. Adm Soc 52(8):1268–1296. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095399719897392

Dahlberg M, Eklöf M, Fredriksson P, Jofre-Monseny J (2011) Estimating preferences for local public services using migration data. Urban Stud 49(2):319–336. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098011400769

Deng X et al. (2022) A review of the balance of regional development in China from the perspective of development geography. J Geogr Sci 32(1):3–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11442-021-1930-0

Deng Y, O’Brien K (2013) Relational repression in China: using social ties to demobilize protesters. China Q 215(215):533–552

Dick-Sagoe C (2020) Decentralization for improving the provision of public services in developing countries: a critical review. Cogent Econ Financ 8(1):1804036. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2020.1804036

Ding L, Zhang N, Mao Y (2021) Addressing the maldistribution of health resources in Sichuan Province, China: a county-level analysis. PLoS One 16(4):e0250526. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0250526

Eaton S, Kostka G (2014) Authoritarian environmentalism undermined? Local leaders’ time horizons and environmental policy implementation in China. China Q 218:359–380

Fang CL, Cui XG, Liang LW (2019) Theory of coupling circle between urbanization and ecological environment and coupler regulation. J Geogr 74(12):2529–2546

Feuchtwang S (2023) Care as critique of care: public services, social security and ritual responsiveness. China Q 254:354–365. https://doi.org/10.1017/S030574102300036X

Fransham M et al. (2023) Level best? The levelling up agenda and UK regional inequality. Regional Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2022.2159356

Hanushek EA, Woessmann L (2012) Do better schools lead to more growth? Cognitive skills, economic outcomes, and causation. J Econ growth 17:267–321. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10887-012-9081-x

Heckman JJ (2006) Skill formation and the economics of investing in disadvantaged children. Science 312(5782):1900–1902. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-6684-5614-9.ch007

Hertog S, Gerland P, Wilmoth J (2023) India overtakes China as the world’s most populous country, United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs POLICY BRIEF. NO15304: 1–5. https://doi.org/10.18356/27081990-153

Jia J, Liang X, Ma G (2021) Political hierarchy and regional economic development: evidence from a spatial discontinuity in China. J Public Econ 194:104352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104352

Jiang L, Bai L, Wu YM (2017) Coupling and coordinating degrees of provincial economy, resources and environment in China. J Nat Resour 32(5):788–799. https://doi.org/10.11849/zrzyxb.20160512

Jin H, Qian Y, Weingast BR (2005) Regional decentralization and fiscal incentives: federalism, Chinese style. J Public Econ 89(9-10):1719–1742. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2004.11.008

Ladd HF (1992) Population growth, density and the costs of providing public services. Urban Stud 29(2):273–295. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420989220080321

Lapuente V, Van de Walle S (2020) The effects of new public management on the quality of public services. Governance 33(3):461–475. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12502

Lee S, Kim Y (2022) Politics of social investment in post-industrial South Korea. In: Garritzmann JL, Silja H, Palier B (eds) The world politics of social investment: volume II: the politics of varying social investment strategies. Oxford University Press, pp 303–326

Lewis BD (2023) Indonesia’s new fiscal decentralization law: a critical assessment. Bull Indones Econ Stud 59(1):1–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/00074918.2023.2180838

Li L et al. (2023) Equity analysis of public service delivery among regions from temporal and spatial perspectives. Regional Stud 57(5):935–945. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2022.2110228

Li W, Weible C (2021) China’s policy processes and the advocacy coalition framework. Policy Stud J 49(3):703–730. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12369

Li Z et al. (2020) Public services equalization in urbanizing China: indicators, spatiotemporal dynamics and implications on regional economic disparities. Soc Indic Res 152:1–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-020-02405-9

Liao ZB (1999) Quantitative evaluation of coordinated development of environment and economy and its classification system—the case of pearl river delta city cluster. Trop Geogr 02:76–82

Liu D, Qi X (2022) Smart governance: the era requirements and realization path of the modernization of the basic government governance ability. Procedia Comput Sci 199:674–680. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2022.01.083

Liu H, He Q (2019) The effect of basic public service on urban–rural income inequality: a sys-GMM approach. Econ Res Ekonom Istraž 32(1):3205–3223. https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2019.1661005

Liu HY et al. (2022) Research progress of entropy method in water resources and water environment evaluation. J Glaciology and Geocryology 44(1):299–306. https://doi.org/10.7522/j.issn.1000-0240.2021.0131

Lu M, Lou S (2024) New exploration of institutional reform for urban–rural integrated development in China from the perspective of spatial pattern. Econ Geogr 44(9):22–27. https://doi.org/10.15957/j.cnki.jjdl.2024.09.003

Lu Y, Xue C (2011) The power of the purse and budgetary accountability: experiences from subnational governments in China. Public Adm Dev 31(5):351–362

Moran PAP (1950) Notes on continuous stochastic phenomena. Biometrika 37(1/2):17–23. https://doi.org/10.1093/biomet/37.1-2.17

Musgrave RA, Peacock AT (1958) Classics in the theory of public finance. MARTIN’S PRESS, New York

Notestein FW (1950) The population of the world in the year 2000. J Am Stat Assoc 45(251):335–345. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/01621459.1950.10501128

Oates WE (1969) The effects of property taxes and local public spending on property values: an empirical study of tax capitalization and the Tiebout hypothesis. J Political Econ 77(6):957–971. https://doi.org/10.1086/259584

Oates WE (2005) Toward a second-generation theory of fiscal federalism. Int Tax Public Financ 12:349–373. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-005-1619-9

Purvis B, Mao Y, Robinson D (2019) Three pillars of sustainability: in search of conceptual origins. Sustain Sci 14:681–695. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-018-0627-5

Ring M, Ristolainen H, Tiilikainen E (2024) From restricted resources to ethical burden—former home care workers’ reasons for leaving their jobs. J Appl Gerontol. https://doi.org/10.1177/07334648241231404

Roback J (1982) Wages, rents, and the quality of life. J Political Econ 90(6):1257–1278. https://doi.org/10.1086/261120

Robert JB (1991) Economic Growth in a Cross Section of Countries. The Q J Econ 106(2):407–443. https://doi.org/10.2307/2937943

Safarov N (2021) Personal experiences of digital public services access and use: older migrants’ digital choices. Technol Soc 66:101627. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2021.101627

Samuelson PA (1954) The pure theory of public expenditure. The review of economics and statistics, vol 36. MIT Press, pp 387–389

Song Y, Wang J, Ge Y, Xu C (2020) An optimal parameters-based geographical detector model enhances geographic characteristics of explanatory variables for spatial heterogeneity analysis: cases with different types of spatial data. GIScience Remote Sens 57(5):593–610. https://doi.org/10.1080/15481603.2020.1760434

Tan X (2014) Constructing a performance-based accountability system for the Chinese Government. J Public Aff 14(2):154–163

Tiebout CM (1956) A pure theory of local expenditures. J Political Econ 64(5):416–424. https://doi.org/10.1086/257839

United Nations (2015) Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3923923?v=pdf

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2024) World population prospects 2024: summary of results. UN DESA/POP/

Valkama P, Oulasvirta L (2021) How Finland copes with an ageing population: adjusting structures and equalising the financial capabilities of local governments. Local Gov Stud 47(3):429–452. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2021.1877664

Valokivi H et al. (2023) Digital ageing in Europe: a comparative analysis of Italian, Finnish and Swedish national policies on eHealth. Ageing Soc 43(4):835–856. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X21000945

Wu H et al. (2020) Environmental decentralization, local government competition, and regional green development: evidence from China. Sci Total Environ 708:135085. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.135085

Wu X et al. (2022) Low fertility spread in China: a blended adaptation and diffusion explanation. Popul Space Place 28(6):e2555. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.2555

Xu D, Wu X (2022) Separate and unequal: hukou, school segregation, and educational inequality in urban China. Chin Sociol Rev 54(5):433–457. https://doi.org/10.1080/21620555.2021.2019007

Xu R et al. (2022) Inequality of public facilities between urban and rural areas and its driving factors in ten cities of China. Sci Rep 12(1):13244. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-17569-2

Yang C, Zhang Y, Zhang H (2021) Equity in basic education and socioeconomic development. Manag World 37(10):152–166. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-17569-2

Yin H, Zhu H (2012) Research on county-level fiscal expenditure bias towards productive activities. Soc Sci China 33(01):127–147

Yin P, Liu JS, Chen C (2015) The coordination development of four modernizations in Jilin province since the revival of Northeast China. Sci Geogr Sin 35(9):1101–1108. https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:130598455

Zhang J (2017) The evolution of China’s one-child policy and its effects on family outcomes. J Econ Perspect 31(1):141–160

Zhang N, Nike Z, Ming G (2023) The financial foundation, spatial equity, and practical logic of basic public service allocation in county towns in the new era of China. Chin Rural Econ 82:2–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2022.103905

Zhou KZ (2006) Innovation, imitation, and new product performance: the case of China. Ind Mark Manag 35(3):394–402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2005.10.006

Zhou L (2016) The administrative subcontract: significance, relevance and implications for intergovernmental relations in China. Chin J Sociol 2(1):34–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/2057150X15622376

Zhu X (2017) Inter-regional diffusion of policy innovation in China: a comparative case study. Asian J Political Sci 25(3):266–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/02185377.2017.1339619

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Social Science Fund of China (grant number 23BZZ062) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 42301280).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

These authors contributed equally to this work: Li Xiaomei was instrumental in conceptualizing the research question, designing the overall methodology, and writing. She brought invaluable insights into the theoretical framework and literature review. Zhu Jing specialized in statistical analysis and writing. Wang Ziming, together with Zhu Jing, specialized in advanced statistical analysis and modeling. Wan Jiangjun, who guided the initial framing of the study, synthesized the findings, and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required as the study did not involve human participants.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, X., Zhu, J., Wan, J. et al. Equilibrium in adversity: balancing public service supply and demand during population decline. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 1760 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04311-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04311-8