Abstract

Clitics are unstressed and unaccented words or particles that are phonetically dependent on adjacent words, accented in nature. They are available in many languages around the world including the Pashto language, which is spoken in Pakistan and Afghanistan. The native Pashto speakers use clitics extensively in their everyday conversation and writings. There are two basic types of clitics in Pashto called: Second Position (2P) clitics and Endoclitics. 2P clitics fall into three different categories: Proclitics, Enclitics (Modal) and Adverbial. Proclitics and enclitics are further grouped into context-free and context-dependent clitics. Endoclitics among all the clitics are the most challenging type of clitics, as their generation faces many restrictions. Clitics play a vital role in text generation systems. In general, these systems must be understandable, coherent, and accurate. In addition to this, Pashto Language is a low resource language lacking corpus, parser, tagger, and semantic analyzer. It also lacks syntactic-morphology interaction. Furthermore, there is no automatic clitic generation tool. These challenges make the generation of Pashto cliticised sentences a more challenging task. To overcome these challenges, the linguistic behavior of Pashto clitics is studied and formalized into rules to support the automatic generation of cliticised text in this paper. In particular, it used nine different clitic generation procedures and produced 80 clitic generation rules. The proposed clitic generation system is developed in Python, which generates cliticised sentences from the semantic representation of the sentences. To evaluate the efficiency of the developed system, a corpus of 256 syntactically annotated sentences was developed and used. It used syntactic pattern matching rules for the identification and generation of clitics at the sentence level. The sentences produced were checked against the correct responses to declare them correct or incorrect. The proposed system successfully developed both types of clitics with an overall accuracy of 89.72%. In particular, it produced Proclitics and Enclitics with an accuracy of 91.75%. However, its efficiency for modal clitics (87.95%) reduced the overall efficiency of 2P clitics to 89.85%. The precision of the endoclitic system developed was 89.47%.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Natural Language Processing (NLP) is a subfield of Artificial Intelligence (AI), which deals with the tasks of automated understanding and generation of human languages by computers (Chowdhary, 2020). The task of Natural Language Understanding (NLU) focuses on the integration and use of different aspects of a language such as phonology, morphology, syntax and semantics, to enable the computer to understand and process texts written in a natural language. The Natural Language Generation (NLG) part converts information in different representations such as graphs, logical representations, and databases, which are computer-understandable and processable, into texts that sound like human language (Dušek et al., 2020). The automatic generation of a natural text remains a challenging task as the generated text must be at least coherent, accurate, and understandable. This research takes the challenge of automatic generation of clitics in Pashto texts, as native Pashto speakers use them extensively in their everyday conversation and writing.

Numerous NLG systems have been developed and applied to solve practical problems. Recent advances in NLG methods include question generation using reinforcement learning (Chung et al., 2024), text generation from given data using neural planning (Puduppully, 2022), application of recurrent convolutional neural networks for text generation (Ji et al., 2023) and automatic text generation using deep learning algorithms (Du et al., 2023). Clitics generation is another well-known application of NLG systems.

Clitics are an essential part of the Pashto language, and its native speakers use them extensively in their daily discourse. A text without clitics is perceived by native speakers as artificial, verbose, and boring. A clitic is a bounded morpheme that has the syntactic characteristic of a word. However, it shows evidence of being phonologically bound to another word called the “host” of the clitic. A clitic cannot bear accent or stress and, therefore, leans on its host (Shafiei and Kazemi, 2020). Pashto clitics have been considered to follow Noun Phrase (NP) reduction process, also called Weak Anaphoric Reduction Process (WARP) (Tegey, 1996). This linguistic phenomenon is unique to Pashto language. In WARP, a clitic moves from left to right as the noun or noun phrase before it is removed. This movement obeys the syntactic rules of the Pashto language. In Pashto, clitics can occur at various positions in sentences, except at the beginning of a sentence. Most Pashto clitics occur at the Second Position (2P) of the clause, that is, in the second position to the right of a clause (Babrakzai, 2007).

Pashto NLG applications require the ability to insert correct clitics in the final form of an input text. This task is incumbent to an automatic clitic generation, which is defined as the process of incorporating clitics into a computer generated natural language text. Similarly, the placement of clitics within Pashto sentences is determined by the interaction between phonology and syntax (Tegey, 1996), which makes it difficult to fully account for clitics at a single linguistic level. Therefore, the design of a Pashto clitic generation system is needed to overcome the quasi-absence of language resources and tools. The basic aim of this research work was to develop algorithms for the generation of clitics of the Pashto language. Based on the above statement, the following objectives were used for this study:

-

1.

To study the contexts of occurrences of clitics in Pashto and other natural languages.

-

2.

To design Pashto clitics generation rules.

-

3.

To evaluate the accuracy of Pashto clitics generation rules.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section “Background and literature review” provides background information for this research, which focuses on several topics that provide the foundation for this study and an overview of clitics in different languages. It also explores relevant literature. Section “Clitics in Pashto” presents the detailed description of the clitics in Pashto. Section “The development of cliticization rules” describes the development of cliticization rules designed, in this work, for the generation of Pashto clitics. It also explores a manually designed corpus used for the evaluation of proposed work. Section “The proposed Pashto clitic generator” presents the proposed rule-based Pashto clitics generator for 2p clitics as well as Endoclitics. Section “Implementation and evaluation” provides the implementation of the proposed system and its evaluation for the corpus considered in this work. This paper provides the conclusion and future directions of this work in Section “Conclusion and future work”.

Background and literature review

This section describes clitics and their role from different aspects of linguistics and presents a brief survey of clitics in different languages across the world. The motivation and objectives of this work are also presented.

Background

The word ‘clitic’ is derived from a classical Greek word which means “inclined; to lean” (Aronoff and Fudeman, 2011). A clitic is a word that cannot have a primary word stress and thus leans on an adjacent word, called the clitic host, which bears the stress. From the developmental and evolutionary perspective of a language, clitics are linguistic elements that are in the developing stages of grammaticalisation. The grammaticalisation process converts non-functional words such as adjectives and verbs into pronouns and auxiliary verbs (Spencer and Luís, 2012). In later stages, these converted words lose their accent and thus become clitics.

Clitics can be divided into three main types on the basis of their positions towards the host. These types are called enclitic, proclitic, and endoclitic. An enclitic is placed at the end of its host, while a proclitic is placed at the beginning of its host. Pashto language has a third type of clitic called endoclitic, which is attached inside its host. (Halpern, 2017) proposed a different classification of clitics by distinguishing simple clitics, special clitics, and bounded words. A simple clitic is a phonologically weak function word such as a preposition, an auxiliary verb, a definite marker, among others, which is phonologically weak. Therefore, it must phonologically adjoin a full (accented) adjacent word. (Spencer and Luís, 2012). A special clitic is defined as “an unaccented bounded form” that “acts as a variant of a stressed free form with the same cognitive meaning and with a similar phonological makeup.” 2p clitics fall into the category of special clitics (Spencer and Luís, 2012). Bounded words are unaccented words, and they always need a host to attach to. An example given by Halpern (2017) is the English possessive “’s”. Spencer and Luis (2012) summarized that “Halpern (2017) typology reveals that the distinction between simple clitics, special clitics and bounded words is largely based on two distinguishing features, namely: the syntactic distribution of clitics and the relationship between the clitic form and its full form.”

There are two most widely used but different views about clitics. The first perspective,supported by Tegey (1996), suggests that phonological and syntactic rules interact with each other to generate clitics. The second perspective, which is based on generative grammar, advocates that generative grammar can be adopted to analyze sentences with clitics without considering the interaction between syntactic and phonological rules (Kaisse, 1981).

Researchers have been studying clitics in different languages around the world. According to Bender (2014), “a clitic is a linguistic element which is syntactically independent but phonologically dependent.” A clitic is a word that syntactically functions as a free morpheme but phonetically appears as a bound morpheme. Syntactically free means that the rules of syntax treat the clitic as an independent word. Therefore, clitics functions above the word level. Moreover, clitics are often written as separate words. Phonologically bound means that the clitic is pronounced as if it is affixed to an adjacent word. However, a clitic is not an affix.

Anderson (2011) gave a theoretical framework for the clitic phenomena by examining existing theories and analyzing clitics in different languages. The author studied different languages including Icelandic, Kashmiri, Breton, Surmiran Rumantsch, English, Tagalog, and Pashto. The clitics were studied at phonology, syntax, and phrasal morphology levels. Properties such as agreement, clitic climbing, and clitic doubling are elucidated for pronominal clitics. According to Crystal (2011), “clitic climbing occurs when a clitic moves from its local domain to a higher constituent” while “clitic doubling occurs when a clitic is used despite the existence of an element with the same meaning and function in the same clause”. Anderson in his work presented in Anderson (2011) briefly mentioned Pashto endoclitics and classified them as phrasal affixes.

Literature review

Clitics occur in many languages and have been extensively studied by linguists with different orientations. This section illustrates the peculiar properties of clitics in some languages around the world.

Clitics in Indo-European languages

"The Indo-European language family covers most of Europe and spreads, with some breaks, through Iran and Central Asia to South Asia" (Aronoff and Rees-Miller, 2020). Languages such as English, Greek, Spanish, Portuguese, Urdu, and Pashto belong to this family. Example (1) presents a few sentences in English that contain the use of morpheme “’s” at various locations.

Example (1):

(a) What’s going on?

(b) The man is in the big house’s room.

(c) He’s teaching Computer Science in the University.

In Example 1(a), the morpheme “’s” is used as the contraction of “is”, whereas, the morpheme “’s” is used to mark possession in Example 1(b). Example 1(c) shows the constituent position of “’s” in the sentence.

The status of a morpheme can lead to a debate as it happens for the English possessive marker -s. The debate is on whether the possessive marker is an affix or a clitic. In English language, the possessive marker -s looks very much like an affix which takes an entire noun phrase as its host rather than any individual word in that phrase. Elements of this kind are sometimes called phrasal affixes (Nevis, 1986). Phrase affixes have most of the properties of normal affixes. Each one of them is always attached to another word. They do not fit into any of the established lexical categories for the language. They tend to empress grammatical (specifically inflected) rather than lexical meaning. However, unlike normal affixes, they are “promiscuous” in their attachments meaning that they may attach to words of approximately any category (Nevis, 1986). Lowe (2016) has proposed using the theory of Lexical Sharing in Lexical Functional Grammar to overcome this problem. 2p clitics occur only in a specific position in a sentence: Either after the first word or after the first phrase. Therefore, these clitics are not sensitive to the POS of the preceding word (Spencer and Luís, 2012).

Traditional Spanish grammar considers two classes of pronouns: stressed pronouns (also called strong pronouns) and unstressed pronouns (also called weak pronouns). The latter are the clitics and they are the only type of clitics in Spanish language unlike other languages such as Pashto, which also has auxiliary and modal clitics. Spanish pronominal clitics are phonologically deficient and cannot be coordinated, modified, or emphasized. They can not appear in isolation, and they do appear only before or after a verb depending on different syntactic and morphological factors.

In Spanish, a clitic doubling construction encodes an entity within a clause by attaching a weak pronoun (clitic) to the verb and an independent nominal phrase which is co-referential to this weak pronoun (Belloro, 2007). The Spanish clitic doubling occurs only with direct and indirect objects, and these doubling constructions are grammatically optional. The analysis of clitic doubling in Spanish is problematic as it raises the question whether the clitic or the independent phrase is the argument of the verb. Belloro (2007) suggests that the clitic doubling must depend on the cognitively accessible target-referent sentence. The dialect of Spanish spoken in and around Buenos Aires, Argentina, is known as Rioplatense or River Plate Spanish. Castel (2005) used a microgrammar of River Plate Spanish clitics to address the word-order constraints underlying the combinatory potential of clitics with other clitics and clitics with their governing verbs. Clitics are defined as functor signs that seek arguments (verbs or other clitics) in the forward direction.

Endoclitics are not common as proclitics and enclitics. In addition, their positions differ in different languages. The endoclitics in European Portuguese follow an intermorphemic placement while they follow an intramorphemic placement in Pashto language (Smith, 2013). (Smith, 2013) highlighted that the “intramorphemic placement of clitics is more challenging for linguistic theory, as it could involve a complex interaction of morphology, syntax and phonology, which is impossible to model directly in some (but crucially not all) frameworks.”

Urdu language is an Indo-european language and it belongs to the Indo-Aryan language family branch. Butt and King (2008) analyzed Urdu genitive case marker as a clitic and the ezafe construction as either a phrasal affix or clitic in Urdu language. The authors tried to discover the possibilities for the interaction of phonology, morphology, and syntax to determine lexical and affixal properties of clitics as well as their behavior as an independent syntactic unit. The authors used post-lexical prosodic phonology to cover the properties of clitics and ezafe. They concluded that phrasal affixes and clitics should not be distinguished from each other. However, this point of view has been contradicted as Rgveda clitics have been described, which are obtained from the prosodic movement of clitics between the c-structure and p-structure in Lexical Functional Grammar (Lowe, 2016).

Clitics in Semitic languages

Semitic languages belong to the Afro-Asiatic language family. Arabic is the most widely-spoken North-west Semitic language. It has only proclitics and enclitics and does not have endoclitics like the Pashto language. (Nash and Rouveret, 2002) studied the distinction between enclitics and proclitics in pronominal clitic constructions in Romance and Semitic languages. Their analysis is based on two underlying assumptions: 1) clitics do not take pre-identified positions in a sentence or phrase but use maximum knowledge of categorial structure for placement; and 2) the placement of a clitic is dependent on inflectional properties of the language.

Amharic language belongs to the South Semitic branch (Kramer, 2012). In Amharic, first-person clitic pronouns proceed with a second-person pronoun. Amharic clitic doubling has been argued to be either agreement feature or pronoun-like morphemes that associate with the direct object and attach to the nearest verb. Amharic clitics have been found to occur only to the right of the host verb or noun. The clitics attaching to verbs have prepositional properties, whereas, clitics attaching to nouns are mostly interpreted as possessives (Kaech, 2022).

Clitics in Austronesian languages

The Austronesian language family covers a large set of languages. The western Austronesian languages have been identified to exhibit pronominal clitics. According to (Hemmings, 2016), “clitic phenomena is another means often used to distinguish between Pthe hilippine-type and Indonesian-type.” It was suggested that 2p enclitics are “a key feature of Philippine-type languages while proclitic actors are characteristics of Indonesian-type languages (Hemmings, 2016)".

Tagalog is a western Austronesian language spoken mainly in Philippines. In Tagalog, 2p clitics can occur only in one specific position, that is, immediately after the first accented word of a clause (Spencer and Luís, 2012). However, their occurrence is under some morphological constraints. Monosyllabic pronominals must precede other clitics and non-pronominal clitics must precede disyllabic pronominals. The clitics in Pashto and Tagalog share some similarities in terms of syntax. Discourse clitics combine with sentential clitics (Spencer and Luís, 2012) forming a cluster of clitics in both the languages. (Kaisse, 1981) analyzed clitics in different languages and concluded that, even though, the 2p clitics principle holds for the languages such as TagaLog, there exist languages such as Pashto, in which the position of 2p clitics after an initial is possibly a phrasal constituent.

Clitics in Udi Language

The Udi language belongs to the Northeast Caucasian language family. Like Pashto, the Udi language also has endoclitics. In Udi, the verb carries tens-mood-aspect as a suffix. The verb roots (stems) are classified as simple or complex. Simple stems are monomormphimic. Person markers and some other grammatical morphemes can be inserted in a verbal root (Luís and Spencer, 2005). These person markers and morphemes are considered endoclitics with the following properties (Ganenkov et al., 2011). They:

-

1.

attach to consitutent, which bears the main focus in a sentence.

-

2.

appear inside the monomorphemic verb stem.

-

3.

break the lexical integrity principle. The internal structure is affected by the syntax and the position of clitic.

The review of existing work conducted in this work concludes that current studies focus on issues such as incorporating clitics into existing generative grammars, differentiating clitics and affixes, and theorising the interaction of different linguistics components such as phonology, syntax, morphology, and prosodic structures with respect to clitics. In general, clitics are found to be phonologically bound and follow syntactic rules of distribution similar to words.

Clitics and NLP

The basic steps in any NLP system are tokenization, morphological analysis or generation, POS tagging, and syntactic parsing. Tokenization splits a sequence of language symbols into a list of tokens that includes lexical words. Morphological analysis splits a lexical word into a sequence of morphemes. POS tagging labels each token with its grammatical class. Syntactic parsing analyzes the grammatical structure of sentences.

For possible clusters of clitics (including four proclitics before the stem while three enclitics after the stem), (Alotaiby et al., 2010) evaluated the impact of including an Arabic clitic tokenizer during the tokenization of a large Arabic corpus containing 600 million words. The authors found that by adding the clitic tokeniser, the lexicon size at the end of the tokenization process was reduced by 24.54%. (Attia, 2007) implemented a clitic guesser for the Arabic language in their Arabic tokenizer. European NLP systems have also been adopted to process Arabic clitics (Grefenstette et al., 2005).

Clitics have been studied for morphological processing. Indonesian cliticized words have been analyzed at the morphological level by (Larasati, 2012). Such a morphological study has been carried out for English language to decide that the English Possessive “’s" is a clitic or it behaves like an affix (Lowe, 2016). (Pineda and Meza, 2005) have developed computational models for parsing and generation of clitics in Spanish language. (Goldstein and Haug, 2016) worked on the generation of Greek clitics, and for this reason they added multiple context-free grammars to c-structure. They performed various experiments and obtained good response. Pronominal clitic parsing for French has been implemented in the multilingual Fips parser. The parser is capable of differentiating between pronominal chains and the absorption of arguments in reflexive reciprocal clitics when these clitics agree with the syntactic subject (Wehrli, 2017). (Groß, 2014) used catena-based dependency morphology to analyze clitics, which is an extension of the catena-based dependency syntax. They used morph catena and hyphenation to analyze the process of cliticization.

The non-existence of automated methods for clitics’ generation in Pashto language motivated us to design clitics’ generation rules and, then, implement them as clitics’ generator using Python language. The main objective is to help develop, ultimately, an NLP application.

Clitics in Pashto

In linguistics literature, clitics are described as morphemes that are neither independent words nor morphological affixes. Syntactically and phonologically, clitics follow the host word to which they are attached. They are grouped into two (2) generic types called 2p clitics and endoclitics, where the former is further sub-grouped as proclitics, enclitic (Modal) and adverbial clitics. Proclitics are prefixed to host postpositions, whereas, enclitics are suffixed to host pronoun, noun, or a prepositional phrase. Proclitics are also called oblique pronominal clitics, which are also called directional verbal clitics when they occur with the verbs only. Examples of such verbs are leegel “to send”, khyel “to show”, and bakhel “to forgive”. Endoclitics are inserted into the root or stem of the host by splitting the root or stem into semantically deficient parts. Table 1 presents the complete list of Pashto clitics.

In general, Pashto clitics occurs in the 2p of a clause or sentence (Babrakzai, 2007). They may also occur in other different positions in sentences except at the beginning of a sentence. According to (Tegey, 1996), “2P clitics appear after the first stress-bearing phrasal constituent in the Pashto clause”. The phrasal host must contain at least one primary accent (Dost, 2005). On the other hand, an endoclitic is inserted inside a word by splitting the word into two separate non-adjacent and semantically vacuous parts. Endoclitics may not be considered morphological inflections as their semantics are not related to the host word in most cases (Din, 2013). (Bögel, 2010) analyzed that endoclitics are subject to prosodic and syntactic constraints. Logically, a clitic is placed after the first item that carries lexical stress in a sentence. Syntactically, endoclitics appear after aspect-caused stressed constituents. Morphologically, endoclitics violate the principle of lexical integrity, which states that syntactic operations may not interfere with the morphology of words (Azizud Din et al., 2012); (Kopris and Davis, 2005).

The development of cliticization rules

This section first introduces the structure of the corpus developed during this work. It then summarizes the clitics replacement options for different parts of speech along with syntactic structures, which provide basis for the generation of cliticization rules. It also enlists procedures for developing different types of cliticization rules.

Corpus design

This work developed a medium-sized corpus due to the nonexistence of such a corpus for the Pashto language. This corpus is carefully, but manually, designed from the existing work presented in Rashtheen (1994); Tegey (1996); Wardak (1990). It consists of 256 sentences, which are selected from a large set of literature. Table 2 provides the distribution of these sentences based on different types of clitics. The sentences selected for cliticization in this work are morpho-syntactically annotated manually as the proposed system requires input in this format. This annotated form considered the morpho-syntactic information such as direct object, subject, strong pronouns and their cases, number, and gender. The sentences in corpus are declarative and they are all encoded using a Prolog like predicate syntax.

Table 3 illustrates example annotated sentences of different types of clitics from the developed corpus.

Developing cliticization rules

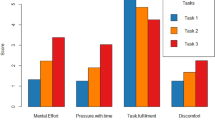

This section presents nine (9) different procedures that are used to design clitic generation rules, which are divided into five groups called: context-free clitics, context-dependent clitics, adverbial clitics, modal clitics and endoclitics, as shown in Fig. 1. Clitic generation task can be defined as the process of inserting a clitic into a sentence in place of a strong pronoun. The placement of clitic in a sentence is determined by the syntactic properties of different parts of a sentence such as verb and subject (Azizud Din et al., 2012). Based on the above mentioned design procedures, a set of eighty (80) different rules are developed for clitics’ generation is this work. These rules are enlisted as in the supplementary file from serial number 0–79. Clitics placements along with the cliticization procedure(s) for different types of clitics are presented in Section “Context-free replacement rules” to “Generating endoclitics” while the design procedures are enlisted in Table 13.

Context-free replacement rules

A context-free replacement rule is applied when a strong pronoun has to be replaced by a 2p clitic. It is called “context-free” as it requires no syntactic constraints along with the grammatical features of strong pronouns. These grammatical features are person (first, second, or third), gender (feminine or masculine) and number (singular or plural). Table 4 provides the relationship, used by the context free replacement rule, between strong pronouns and 2p clitics. The Context-free Procedure for the development of context free replacement rules is numbered as Procedure/Rule 1 and it is presented in first row of Table 13.

Context-dependent replacement rules

Table 5 shows the replacement rules used for the generation of syntactically constrained context sensitive clitics. The application of these rules is based on matching the syntactic constraints specified in rules with those syntactic features marked in the annotated sentence (Din et al., 2013). The pronoun is transformed into either a pronominal clitic or an oblique pronominal clitic, when all the conditions given in Conditions column of Table 5 are satisfied. If a condition cannot be met for a given pronoun, then, the default clitic is generated as shown in Table 5 by an absence of conditions.

Context dependent clitics generation is achieved using four different procedures. These procedures are termed as Procedure-2/Rule-2, Procedure-3/Rule-3, Procedure-4/Rule-4, Procedure-5/Rule-5 and they are provided in Table 13 from row 2 to 5 in given order. Procedure-5 is used for the generation of oblique pronominal clitics.

Generating Adverbial clitics

The adverbial clitics in Pashto are  [kho] and

[kho] and  [no]. Clitics

[no]. Clitics  [kho] can be added at the beginning of a sentence, where as

[kho] can be added at the beginning of a sentence, where as  [no] can be added at the end of a sentence. These clitics are different from other clitics as they do not substitute strong pronouns but are, instead, used as focus elements. The use of these adverbial clitics alters the focus of a sentence. Procedure-6/Rule 6 is used to add “kho” and “no” clitics to a sentence and it is given in sixth row of Table 13.

[no] can be added at the end of a sentence. These clitics are different from other clitics as they do not substitute strong pronouns but are, instead, used as focus elements. The use of these adverbial clitics alters the focus of a sentence. Procedure-6/Rule 6 is used to add “kho” and “no” clitics to a sentence and it is given in sixth row of Table 13.

Generating Modal clitics

The modal clitic  [bә] can be inserted into a sentence to mark the obligation and future tense, respectively. These clitics cannot be substituted for a strong pronoun as they are functionally different from pronominal clitics and oblique pronominal clitics. This clitic can be added after the subject or the prepositional phrase of a sentence in present tense. However, it cannot be added in the context of past perfect of irregular verbs. To insert modal “bә” clitic in a sentence, Procedure-7/Rule-7 is used, which inserts “bә” after subject or prepositional phrase if the sentence is in present tense. The logic of Procedure-7 is given in row 7 of Table 13.

[bә] can be inserted into a sentence to mark the obligation and future tense, respectively. These clitics cannot be substituted for a strong pronoun as they are functionally different from pronominal clitics and oblique pronominal clitics. This clitic can be added after the subject or the prepositional phrase of a sentence in present tense. However, it cannot be added in the context of past perfect of irregular verbs. To insert modal “bә” clitic in a sentence, Procedure-7/Rule-7 is used, which inserts “bә” after subject or prepositional phrase if the sentence is in present tense. The logic of Procedure-7 is given in row 7 of Table 13.

Generating Endoclitics

Endoclitic generation rules are treated separately as they are based on the morphological splitting of words. Recall that an endoclitic is a clitic that is attached inside its host. The rules of endoclitic generation are based primarily on the identification and presence of infinitives in sentences (Din et al., 2013). In Pashto language, there are five types of infinitives: (i) infinitives of  , (ii) infinitives of

, (ii) infinitives of  , (iii) infinitives of

, (iii) infinitives of  , (iv) infinitives of

, (iv) infinitives of  and (v) infinitives of

and (v) infinitives of  .

.

Infinitive  has two types. The first type consists of a single word, which cannot be divided into two morphemes, while the second type consists of two separable words. In the bi-morphemic infinitives, often the first morpheme is meaningless. Examples of infinitives having one and two morphemes are shown in Table 6. The last column of the table shows the division of the two word infinitives into separate parts as well as the insertion of a clitic in the middle.

has two types. The first type consists of a single word, which cannot be divided into two morphemes, while the second type consists of two separable words. In the bi-morphemic infinitives, often the first morpheme is meaningless. Examples of infinitives having one and two morphemes are shown in Table 6. The last column of the table shows the division of the two word infinitives into separate parts as well as the insertion of a clitic in the middle.

.

.According to the syntactic conventions of Pashto, when the infinitives end with  and occur with a clitic, the perfective marker

and occur with a clitic, the perfective marker  is placed at the beginning next to the clitic first. Examples of application of this rule are shown in Table 7.

is placed at the beginning next to the clitic first. Examples of application of this rule are shown in Table 7.

Infinitives ending with  are divided into two types. In the first type, the part of the word that is attached to the final syllable

are divided into two types. In the first type, the part of the word that is attached to the final syllable  is semanticless and cannot occur in an isolated form. An example of such a word is

is semanticless and cannot occur in an isolated form. An example of such a word is  , in which the first part is

, in which the first part is  , and has no semantic sense. In the second type of words, the first part has special meaning and can have grammatical role of an adjective or a noun. Examples of these two types of words are shown in Table 8.

, and has no semantic sense. In the second type of words, the first part has special meaning and can have grammatical role of an adjective or a noun. Examples of these two types of words are shown in Table 8.

.

.The words ending with  do not allow endoclitic embedding. These infinitives have two types. In the first type, the first part of the word has no meaning. An example of such a word is

do not allow endoclitic embedding. These infinitives have two types. In the first type, the first part of the word has no meaning. An example of such a word is  . In the second type, the first part is meaningful (adjectives and nouns). Examples of such words include

. In the second type, the first part is meaningful (adjectives and nouns). Examples of such words include  and

and  . Table 9 shows a few more examples of such infinitival words.

. Table 9 shows a few more examples of such infinitival words.

.

.Infinitives ending with the word  (“to do”) have also two types. The first type of infinitive needs an object, while the second type does not need any object. Examples of

(“to do”) have also two types. The first type of infinitive needs an object, while the second type does not need any object. Examples of  are shown in Table 10.

are shown in Table 10.

.

.The clitic placement differs with the aspect. In past imperfective form, the clitic moves to the end of the word, while in past perfective form, the clitic is embedded inside the word. Table 11 shows examples of the placement of clitic in the past imperfect and past perfect tenses.

Infinitives ending with the word  (“to be”) are divided into two types. In the first type, an object is required, while in the second type, no object is required. Examples of such words are shown in Table 12.

(“to be”) are divided into two types. In the first type, an object is required, while in the second type, no object is required. Examples of such words are shown in Table 12.

.

.The clitic may divide the constituents of a compound verb only when it is in perfective aspect to preserve the meaning of the sentence. Endoclitic generation is performed using two procedures: Procedure-8/Rules-8 and Procedure-9/Rule-9. The logic for these procedures is presented correspondingly in row 8 and 9 of Table 13.

The proposed Pashto clitic generator

The rules developed in previous section (Section “Developing cliticization rules”) are used for developing Pashto clitic generator in this section. An overview of different parts of Pashto clitic generator is shown in Fig. 2. It takes a non-clitic morpho-syntactically annotated sentence or a sequence of such sentences as input and, therefore, the clitic generation is considered as a post-generation process. The proposed system produces a Pashto cliticised sentence based on two algorithms: one for 2p Clitics generation (Algorithm 1) while the other for endoclitics (Algorithm 2), as a result. Both algorithms require a set of resources such as a list of clitics, a list of pronouns, syllabification dictionary, and a set of clitics’ generation rules, in order to generate cliticised sentences of one of the two categories.

Figure 3 illustrates the cliticization process of the proposed generator with the help of an example of 2p Clitics. On the left-side of figure is an example of a Pashto sentence that is going to the process of cliticization. This input sentence is a non-clitic sentence. As mentioned earlier, the words in the input sentence need to be annotated with morpho-syntactic information. The sentence is, therefore, shown in morpho-syntactic form. The next step finds a matching cliticization rule against the structure of the sentence. The next stage produces the 2p cliticised form of the sentence. Since the given sentence belongs to 2p Clitics, it has no infinitives and, thus, the 2p Cliticised form is produced as an output of the developed parser instead of its equivalent sentence with Endoclitics.

Algorithm 1 is developed that automatically generates clitic sentences that fall into 2p clitics. It takes the morpho-syntactically annotated form of an input sentence “s” that is assumed to have a strong pronoun. The algorithm explores the rules’ set one by one until it is completely exhausted. It selects a rule with a strong pronoun similar to the one in input ’s’. The algorithm checks the morpho-syntactic constraints of the sentence against the rule, and it is used if all constraints are satisfied. In case of failure, the algorithm moves to next rule. When an applicable rule is found, the strong pronoun is removed from the sentence and a clitic suggested by the rule is introduced at a position specified by the rule. In case, there is no matching rule in the rules’ set, the algorithm produces the input sentence as an output.

This work uses strict morpho-syntactic constraints. Therefore, the proposed clitic generator is unable to use more than one rule against a sentence. In response, the current solution is fully deterministic. The user interface of the proposed 2p clitics’ generator is shown in Fig. 4.

Algorithm 1

Second Position Clitics Generator for Pashto Language.

Require: A syntactically annotated sentence s

Ensure: Producing a cliticised sentence or the actual sentence

//Initializations

RulesTable = Get and Assign all 2P Clitic Generation Rules;

1: while (The RulesTable is not completely exhausted) do

2: Select a Rule (Rule (i));

3: if (Rule (i).StrongPronoun is in statement s) then

4: if (s satisfies all syntactic constraints in Rule (i)) then

5: Remove Rule (i).StrongPronoun from s;

6: Insert Rule (i).Clitic at position specified by Rule (i).Position in s;

7: Return;

8: else

9: Continue;

10: end if

11: else

12: Continue;

13: end if

14: end while

Algorithm 2 presents the pseudocode for generating endoclitics. It works identically to the 2p Clitics generation system presented in algorithm 1 except that it searches for Informative verb (iv) in the input sentence. If an iv is found in the input sentence, then, it is split into two syllables: A and B. If the input sentence has already a clitic (clt), then, the clt is removed from the sentence and inserted between A and B. Otherwise, if the sentence has a strong pronoun, then, the clitic (clt) specified by the rule is inserted between the two syllables A and B, and the strong pronoun is removed from the sentence. For the purpose of finding the syllabification of infinitive verbs, the generator uses only a single dictionary of infinitive verbs that specifies the syllables of verbs and infinitive verbs. A portion of this syllabification dictionary is shown in Fig. 5. The user interface for the proposed Endoclitic generator is provided in Fig. 6.

Algorithm 2

Endo-Clitics’ Generation for Pashto Language.

Require: A syntactically annotated sentence s

Ensure: Producing a cliticised sentence or the actual sentence

//Initializations

RulesTable = Get and Assign all relevant Rules;

1: while (The RulesTable is not completely exhausted) do

2: Select a Rule (Rule (i));

3: if (Rule (i).StrongPronoun is in statement s) then

4: if (s contains infinitive verb (iv)) then

5: Split iv into two syllables A and B having A as a single syllable from syllabification dictionary (given in Fig. 5);

6: if (s has a clitic (clt)) then

7: Remove clt from s;

8: Replace iv in s with A + clt + B;

9: Return;

10: else

11: Remove Rule (i).StrongPronoun from s;

12: Replace it in s with A + Rule (i).clt + B;

13: Return;

14: end if

15: else

16: Continue;

17: end if

18: else

19 Continue;

20: end if

21: end while

Implementation and evaluation

This section explores the implementation platform of the proposed clitics’ generation system and the corpus used for its evaluation. It defines the measure used for the evaluation purposes and then discusses the evaluation results.

The implementation

Python language is used for the implementation of the proposed clitic generator in this work. It is used for its high-level syntax that allows one to manipulate strings and help develop rapid prototypes. It comes with a large set of libraries for text processing tasks such as POS tagging and syntactic parsing.

The Corpus used

This work evaluated the efficiency of the proposed algorithms by using a manually developed medium sized corpus of 256 sentences for Pashto language in this work. The design and structure of this corpus are provided in “Corpus Design”.

Evaluation metric

This work used a single metric called: accuracy to find out the efficiency of the proposed algorithm against different types of clitics. This work calculated the accuracy in percent(%). Accuracy is calculated with the help of Equation (1).

Evaluation and results

During the evaluation, all the 256 Pashto sentences in the selected corpus, in the annotated form presented in Table 3 except the output part, were fed to the Python-based clitic generator through the user interfaces given in Figs. 4 and 6 for 2p clitics and endoclitics correspondingly. The output of the clitic generator against each sentence is, then, compared to the output part of corresponding sentence in the Pashto corpus. If both the generated and expected sentences exactly match each other, the sentence generation is recorded as correct, otherwise, incorrect. The developed system generates the generated sentence along with summary of the rules applied and accuracy and produces in the lower half of the user interface given in Figs. 4 and 6.

The summary of results in terms of accuracy for different categories of clitics, 2p Clitics and Endoclitics in groups as well as overall responses for both categories is presented in Table 14. It shows that 73 out of 83 sentences with modal clitics were cliticised correctly, yielding an accuracy of 87.95%. Proclitics and enclitics gave 91.75% accuracy (as it correctly cliticised 89 out of 97 sentences) while the 89.47% accuracy (as it converted 68 out of 76 sentences correctly) was achieved for endoclitics. The corpus included a total of 180 sentences that fall in 2p clitics, in which 162 were correctly cliticised yielding an accuracy of 89.85%. A total of 230 sentences out of 256 in the considered corpus were correctly cliticised giving an overall accuracy of 89.72%.

The output generated by the 2p Clitics generator and Endoclitic generator given in Fig. 4 and Fig. 6 correspondingly gave a summarized insight. However, the rules used against different cases are not totally visible. Table 15 is produced to provide this missing including total number of sentences processed, the number of rules used to process these sentences and the list of rules used in each case. It shows that Proclitics and Enclitics fired 38 rules while cliticing the 97 sentences. The number of rules increased to 56 when 83 sentences were processed for modal clitics. However, 47 different rules were used to process 76 sentences for Endoclitics.

Conclusion and future work

Conclusion

The study explored the linguistic rules of Pashto clitics and then formalized them for automatic clitic generation. It was learned that very little computational work has been done on various aspects of the Pashto language. Several important tools that are considered helpful in processing the Pashto language are yet to be developed. The most important tools required for processing Pashto general text are a POS tagger and a syntactic parser. Pashto morphology, ambiguity and syntax are some other important areas, which must be researched in detail.

This work proposed a Pashto language clitic generator and implemented it using Python language. The system takes syntactically annotated sentences as input and applies appropriate rules, from the large set of rules developed in this work, for converting strong pronouns into clitics. Besides pronominal, oblique pronominal, modal and adverbial clitics, the developed system successfully demonstrated the generation of endoclitics. It achieved an overall accuracy of 89.72% on a test corpus of 256 sentences developed and used in this work. Individually, it cliticised proclitics and enclitics with an accuracy of 91.75%, modal clitics with an accuracy of 87.95%, and endoclitics with an accuracy of 89.47%. One of the strengths of the proposed clitic generator is post-processing nature making it capable of introducing clitics in the text generated by any method/technique. It, therefore, makes the text generation systems independent of clitic generation. The clitic generation based on post-processing effectively decouples text generation and clitic generation tasks, and thus simplifying the text generator architecture.

Future work

To enhance the performance of the proposed system, there is a strong need to develop resources for the Pashto language that will be identified in the future. These future directions include the:

-

1.

development of a Pashto morphological analyzer.

-

2.

design of a Pashto syntactic parser.

-

3.

increase in size of Pashto annotated corpus.

Data availability

The list of rules, the corpus, and the output of the clitic generator are provided as supplementary files.

References

Alotaiby F, Foda S, Alkharashi I (2010) Clitics in arabic language: a statistical study. In Proceedings 24th Pacific Asia conference on language, information and computation, pp 595–601

Anderson SR (2011) Clitics. The Blackwell companion to phonology, pp 1–17

Aronoff M (2011) Fudeman K What is morphology? Vol 8. John Wiley & Sons

Aronoff M, Rees-Miller J (2020) The handbook of linguistics, vol 460. Wiley Online Library

Attia M (2007) Arabic tokenization system. In Proceedings of the 2007 workshop on computational approaches to semitic languages: common issues and resources, pp 65–72

Azizud Din, Yeo AW, Ranaivo-Malancom B (2012) Pashto endoclitic generation. In Proceedings international conference on computer information science (ICCIS), vol 1, pp 248–252

Babrakzai F (2007) Topics in Pashto syntax. Thesis, University of Hawaii

Belloro VA (2007) Spanish clitic doubling: a study of the syntax-pragmatics interface. State University of New York, Buffalo

Bender EM (2014) Language collage: grammatical description with the lingo grammar matrix. In LREC, pp 2447–2451

Bögel T (2010) Pashto (endo-) clitics in a parallel architecture. In Proceedings 15th international lexical functional grammar conference (LFG10), pp 85–105

Butt M, King TH (2008) Urdu ezafe and the morphology-syntax interface. In Proceedings of LFG08 conference. CSLI Publications, Stanford

Castel VM (2005) River plate spanish clitic packages: an openccg account of order constraints, pp 43–70

Chowdhary K (2020) Natural language processing. Fundamentals of artificial intelligence, pp 603–649

Chung H-L, Chan Y-H, Fan Y-C (2024) Handover qg: question generation by decoder fusion and reinforcement learning. IEEE/ACM Transactions on Audio, Speech, and Language Processing

Crystal DA (2011) dictionary of linguistics and phonetics, vol 30, John Wiley & Sons

Din A (2013) Cliticization and endoclitics generation of Pashto language. In Proceedings of the 4th workshop on South and Southeast Asian natural language processing, pp 77–82

Din A, Malancon BR, Yeo A (2013) Algorithm for the cliticization of context dependent pronouns in Pashto language. In Proceedings 4th international conference on computing and informatics. ICOCI, pp 28–30

Dost AA (2005) domain-based approach to 2p clitics in Pashto

Du H, Xing W, Pei B (2023) Automatic text generation using deep learning: providing large-scale support for online learning communities. Interact Learn Environ 31:5021–5036

Dušek O, Novikova J, Rieser V (2020) Evaluating the state-of-the-art of end-to-end natural language generation: the e2e nlg challenge. Comput Speech Lang 59:123–156

Ganenkov D, Lander Y, Maisak T (2011) The ordering of ‘endoclitics’ and the structure of verbal roots in niž udi

Goldstein DM, Haug DTT (2016) Second-position clitics and the syntax-phonology interface: the case of ancient greek. In Proceedings of the joint conference on head-driven phrase structure grammar and lexical functional grammar, Center for the Study of Language and Information, pp 297–317

Grefenstette G, Semmar N, Elkateb-Gara F (2005) Modifying a natural language processing system for european languages to treat arabic in information processing and information retrieval applications. In Proceedings of the ACL workshop on computational approaches to semitic languages, pp 31–38

Groß T (2014) Clitics in dependency morphology. Depend Linguist 229:252

Halpern AL (2017) Clitics. The handbook of morphology, pp 101–122

Hemmings C (2016)The Kelabit language: Austronesian voice and syntactic typology. Thesis, SOAS University of London

Ji Z et al. (2023) Survey of hallucination in natural language generation. ACM Comput Surv 55:1–38

Kaech LS (2022) Word stress and phrasal intonation in addis ababa amharic. University of California, Los Angeles

Kaisse EM (1981) Separating phonology from syntax: a reanalysis of Pashto cliticization. J Linguist 17:197–208

Kopris CA, Davis AR (2005) Endoclitics in Pashto: implications for lexical integrity. In Proceedings 5th mediterranean morphology meeting, pp 15–18

Kramer R (2012) Differentiating agreement and doubled clitics: object markers in amharic. In Proceedings 41st annual conference on African linguistics: African languages in contact, pp 60–70

Larasati SD (2012) Identic corpus: morphologically enriched indonesian-english parallel corpus. In LREC, pp 902–906

Lowe JJ (2016) English possessive’s: clitic and affix. Nat Lang Linguist Theory 34:157–195

Luís AR, Spencer A (2005) Udi clitics: a generalized paradigm function morphology approach. Essex Res Rep Linguist 48:35–47

Nash L, Rouveret A (2002) Cliticization as unselective attract. Catalan J Linguist 1:157–199

Nevis JA (1986) Finnish particle clitics and general clitic theory. Thesis, Ohio State University. Department of Linguistics

Pineda LA, Meza IV (2005) A computational model of the spanish clitic system. In Proceedings international conference on intelligent text processing and computational linguistics. Springer, pp 73–82

Puduppully RS (2022) Data-to-text generation with neural planning. The University of Edinburgh

Rashtheen S (1994) Pashto grammar. University Book Agency, Peshawar, Pakistan

Shafiei S, Kazemi F (2020) Persian clitics in virtual networks. Theory Pract Lang Stud 10:1299–1304

Smith PW (2013) On the cross-linguistic rarity of endoclisis. In annual meeting of the Berkeley linguistics Society, vol 39, pp 227–244

Spencer A, Luís AR (2012) Clitics: an introduction. Cambridge University Press

Tegey H, Robson B (1996) A reference grammar of Pashto. Center for Applied Linguistics, Washington

Wardak GW (1990) Pushto shūd (Pashto teacher). A guide to learn Pushto language. Pak-German Bas-Ed, Peshawar, Pakistan

Wehrli E (2017) Parsing language-specific constructions: the case of french pronominal clitics, pp 465–475

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (RS-2025-00554526), the Culture, Sports and Tourism R&D Program through the Korea Creative Content Agency grant funded by the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism in 2023 (Project Name: Cultural Technology Specialist Training and Project for Metaverse Game, Project Number: RS-2023-00227648), and the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (grant number: HI22C1651).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Aziz Ud Din developed the corpus, cliticization rules, and clitic generation system, performed experiments, prepared initial tables and figures. Ihsan Rabbi developed the cliticization rules, performed experiments, prepared the initial draft, improved figures and tables, and approved the final draft. Umar Farooq developed the rules generation procedures and algorithms, evaluated the proposed system, analyzed the results, and prepared the final draft. Jawad Khan performed experiments, analyzed the results, and approved the final draft. Younhyun Jung designed the experiments, prepared the initial draft, and approved the final draft.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain activities involving human participation.

Informed Consent

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Din, A.U., Rabbi, I., Farooq, U. et al. The development and evaluation of an automatic clitic generator for Pashto language. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 491 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04516-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04516-5