Abstract

Perfectionism has gained increasing attention from researchers due to its significant impact on work and non-work outcomes. However, it remains unclear whether the influence of perfectionism on teams is positive or negative. Our research provides clarity on the group effects of leader other-oriented perfectionism. Drawing from the literature on perfectionism and approach-avoidance emotivation theory, we investigate the influence processes (e.g., team affective tones and team performance motivations) and boundary conditions (e.g., team trait resilience) of leader perfectionism on team prosocial behavior and team cheating behavior. Data collected from 152 leaders and 699 employees reveals that leader other-oriented perfectionism positively influences team energy tone, which subsequently enhances team performance approach motivation and facilitates team prosocial behavior. Additionally, leader other-oriented perfectionism positively impacts team anxious tone, which subsequently promotes team performance avoidance motivation and facilitates team cheating behavior. Moreover, team trait resilience strengthens the former chain of processes while weakening the latter. These results shed light on the complex dynamics between leader other-oriented perfectionism, team affective tone, motivation, and ethical behaviors, highlighting the significance of team trait resilience as a boundary condition in these relationships. Theoretical and practical implications are provided.

Similar content being viewed by others

“Perfection is not just about demanding the best from others; it’ s about inspiring them to reach their full potential.”

—Colin Powell

The fierce external competition and the turbulent market environment require employees to constantly do their work to the extreme. Leaders assumes the role of ensuring the extent to which an employee has demonstrated optimal performance and exerted their utmost effort in their work. Thus, leaders in contemporary business context increasingly tend to hold their subordinates to excessively high standards and engage in relentless pursuit of excellence (i.e., leader other-oriented perfectionism) (Xu et al., 2022). For example, Steve Jobs, the late CEO of Apple Inc., was known for his demanding perfectionism and his drive for asking employees to create products that were both aesthetically pleasing and perfectly technologically innovative (Newport, 2019). Similarly, Jeff Bezos, the founder and former CEO of Amazon, was famous for his insistence on high standards for employees and his relentless pursuit of customer satisfaction (Mejia, 2018).

To date, leader other-oriented perfectionism has been mainly conceptualized at the intrapersonal and interpersonal level, focusing on its implications for leaders themselves and their followers. Studies have primarily examined its leader-centered effects, like increased managerial control by exception and reduced transformational leadership (Otto et al., 2021), as well as follower-centered outcomes, such as well-being (Cîrșmari et al., 2023) and creativity (Xu et al., 2022). However, this emphasis limits our understanding of its broader implications. Given the rising prevalence of teamwork in modern organizations (Chen and Kanfer, 2024; Mathieu et al., 2019), neglecting the potential for other-oriented perfectionism to manifest via leaders’ behavior and affect team processes and outcomes is a substantial oversight. This omission could lead to underestimating both the pros and cons of such perfectionism on critical teams’ outcomes. Thus, we should scrutinize the underlying theoretical mechanisms and boundaries between leader other-oriented perfectionism and team-level outcomes, which will advance the literature and provide practical insights for enhancing team management practices in perfectionistic settings.

Recognizing the crucial role of ethical behaviors in team settings for enhancing team performance, maintaining a positive reputation, and ensuring stakeholder well-being (Kish-Gephart et al., 2010; Lemoine et al., 2019), we aim to theorize and investigate leader other-oriented perfectionism as a catalyst for collective ethical actions within teams and its contextual boundaries. Specifically, we focus on two critical team collective ethical actions: team prosocial behavior — actions by team members intended to benefit others or the team as a whole (Zettler, 2022), and team cheating behavior, which involves dishonest or unethical actions taken by team members to gain an unfair advantage (Hillebrandt and Barclay, 2020).

By integrating the literature on perfectionism (Hewitt and Flett, 1991; Xu et al., 2022) and the approach-avoidance emotivation theory (Beall and Tracy, 2017; Roseman, 2008), we clarify how and when leader other-oriented perfectionism influences collective ethical actions within teams. The literature on perfectionism indicates that leader other-oriented perfectionism is inherently paradoxical. On the one hand, it motivates team members to strive for optimal achievements and acquire excellent outcomes via setting extremely high goals (Xu et al., 2022). On the other hand, it creates a harsh and toxic work environment with minimal margin for errors and heightened scrutiny (Hewitt and Flett, 1991). Paradoxical phenomena, like leader other-oriented perfectionism, can lead to ambivalent effects such as emotional ambivalence (Putnam et al., 2016). Thus, we posit that leader other-oriented perfectionism may result in ambivalent team dynamics and outcomes due to such paradoxical nature: although it requires others to achieve the supreme team outcomes, it may unintentionally undermine the desirable results for the team.

Specifically, leader other-oriented perfectionism may paradoxically influence team collective ethical actions via the sequential mediation of team affective tones and team motivational states. The approach-avoidance emotivation theory elucidates environmental stimuli may impact people’s actions through triggering emotional responses that activate specific motivational states (Beall and Tracy, 2017; Roseman, 2008). Meanwhile, emotions with different valences shape whether individuals pursue desired outcomes (i.e., approach motivation) or avoid undesired states (i.e., avoidance motivation) (Roseman, 2008). Therefore, we argue that leader other-oriented perfectionism may simultaneously evoke both team energy tone and team anxious tone, and through these ambivalent affective tones, lead to paradoxical team outcomes: collective prosocial behavior driven by team approach motivation due to team energy tone, and collective cheating behavior driven by team avoidance motivation due to team anxious tone.

Another pertinent question is how to navigate the paradoxical impacts of leader other-oriented perfectionism. The approach-avoidance emotivation theory posits that people’s characteristics can alter their emotional responses to environmental stimuli (Beall and Tracy, 2017; Roseman, 2008). Thus, identifying a team’s collective characteristics is significant in understanding how teams navigate the paradoxical effects of leader other-oriented perfectionism. One such collective traits is team resilience, or a collective tendency to endure or recover from difficult, demanding, and challenging situations (Stoverink et al., 2020). Resilience has garnered growing attention from scholars and practitioners for its crucial role in enabling teams to conquer adversity and sustain effectiveness (Chen and Kanfer, 2024; Mathieu et al., 2019).

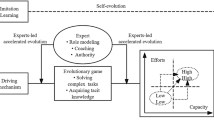

Teams with higher resilience are better at managing stress, adapting to changes, and maintaining high efficacy even under extreme pressure, while teams with lower resilience struggle due to limited resources and poor adaptability to external pressures (Alliger et al., 2015; Meneghel et al., 2016; Salanova et al., 2012). Given these features, team resilience may serve as a critical balance-tipping moderator, amplifying the beneficial outcomes while mitigating the detrimental ones. Therefore, we posit that team resilience enhances the positive influence of leader other-oriented perfectionism on team energy tone. Conversely, it mitigates the positive influence of leader other-oriented perfectionism on team anxious tone. Our theoretical model as shown in Fig. 1.

Our research makes several contributions. First, the research broadens the understanding of how leader perfectionism affects teams. Previous studies have primarily focused on the leader-centered effects and follower-centered outcomes of leader other-oriented perfectionism. Our study broadens the understanding of its influence by investigating its effects on team-level outcomes, addressing Ocampo et al.’s (2020) call for more research on how the behaviors of perfectionist leaders influence team outcomes. We identify the paradoxical nature of leader other-oriented perfectionism, revealing its potential for both constructive and destructive effects at the team level, which contributes valuable insights to the existing literature on the consequences of leader other-oriented perfectionism.

Second, our research introduces the emotivational perspective to investigate how leader other-oriented perfectionism impacts team outcomes. Despite previous studies have mainly focused on the cognitive effects of leader perfectionism (e.g., Xu et al., 2022), the role of emotions has been neglected, leaving the factors shaping group-level emotions poorly understood (e.g., Rodell and Judge, 2009). Our study addresses this issue by integrating these significant research trends with new theoretical perspectives. By adopting the approach-avoidance emotivation theory, we explore the elicitations and impacts of team emotions, thereby deepening our understanding of these emotional dynamics.

Third, our study responds to calls for investigating the determinants of team ethical/unethical behaviors. The previous research on the antecedents of such behaviors has primarily focused on team characteristics (e.g., Pearsall and Ellis, 2011), leadership styles (e.g., Kuenzi et al., 2020; Mayer et al., 2009; Mayer et al., 2012), team cognition and motivation (e.g., Chen et al., 2020; Hu and Liden, 2015), while neglecting the impact of leaders’ traits on team ethical/unethical behaviors. Although ethical/unethical behaviors in organizations have received widespread attention from researchers, research often focuses on individuals and is rarely analyzed at the team level (Pearsall and Ellis, 2011). By exploring the impact of leader perfectionism on team outcomes, we hope to shed light on the motivators that drive team ethical/unethical behaviors and provide insights for future research in this area.

Fourth, this study will expand the research on team trait resilience to further clarify the constructive role that team resilience plays in a perfection-demanding work environment. While much research has examined the effects of individual trait resilience under challenging situations (e.g., Mitchell et al., 2019), less is known about how team trait resilience may influence team processes and outcomes. Research on team trait resilience is still in its early stages (Stoverink et al., 2020). Recently, there has been a growing body of research on team resilience that sheds light on the phenomenon of teams achieving success despite encountering substantial adversity (Lawrence and Maitlis, 2012; Stephens et al., 2013; Stuart and Moore, 2017). In this research, we theorize trait resilience as a team-level construct to explore the interactive effect of leader other-oriented perfectionism and team trait resilience on team affective tones, motivations, and behaviors. This will provide insights into how to mitigate the dysfunctional effects of leaders’ demands for perfection while amplifying the constructive impacts of such demands.

Theoretical Grounding and Hypothesis Development

Leader Other-Oriented Perfectionism and Team Affective Tones

Other-oriented perfectionism, similar to tendencies like humor, humility, and narcissism (Cooper et al., 2018; Resick et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2017), is an individual trait (Shoss et al., 2015; Xu et al., 2022) that manifests in specific behaviors toward others (Pincus and Ansell, 2003; Xu et al., 2022). In the leadership context, other-oriented perfectionism can be exhibited by actions toward their followers, such as imposing excessively high standards far beyond what is realistic (Shoss et al., 2015), making biased and excessively critical assessments (Hewitt and Flett, 1991; Shoss et al., 2015; Stoeber, 2015, 2018), and requiring flawless results without any errors and mistakes towards their followers (Xu et al., 2022). Different from transactional leadership, which involves discerning the needs of their subordinates and reciprocating with rewards corresponding to their effort and performance levels (Bycio et al., 1995), leader other-oriented perfectionism focuses on setting optimal task objectives for followers without considering their individual needs.

Leader other-oriented perfectionism exhibits a paradox for their followers. Paradox involves the simultaneous existence of contradictory yet interrelated aspects (Schad et al., 2016). Individuals encounter a paradox when they face aspects that seem reasonable individually but contradictory when occurring together. On the one hand, other-oriented perfectionist leaders create a challenging work requirement that can motivate employees to achieve superior outcomes. These leaders are deeply committed to the success of the team. They set high standards, expecting employees to fully utilize their potential and capabilities, and ensure excellent quality in their work (Stoeber and Corr, 2015; Xu et al., 2022). These standards often exceed regular job requirements, demanding excellence in all aspects. This high benchmark inherently challenges employees, pushing them to continuously strive to meet or even surpass these expectations (LePine et al., 2016).

On the other hand, leader other-oriented perfectionism creates an extreme and rigid work atmosphere as it permits very little space for error or defects in order to achieve the best work results. These leaders often have zero tolerance for mistakes and closely scrutinize every detail of their employees’ work (Smith et al., 2017). Any deviation from the high standards set by the leaders is likely to be pointed out and criticized. This zero-tolerance expectation from leader leaves no room for trial and error, forcing employees to be overly cautious about every aspect of their tasks (Hewitt and Flett, 1991). Consequently, this relentless demand for perfection shapes strict and rigorous work environment for employees.

The literature on paradox suggests that paradoxical social situations can induce emotional ambivalence, subsequently influencing psychological states and behaviors (Putnam et al., 2016). Similarly, leadership research shows that the same supervisor can simultaneously evoke both positive and negative affect in subordinates (Nifadkar et al., 2012). In line with the logic, leadership behavior with a paradoxical nature shapes ambivalent team affective tones. Team affective tone refers to a consistent or homogeneous affective response within a group (George, 1990). This phenomenon occurs at the group level because it relies on the consistency of affect among its members (George, 1990). In teams, affect can aggregate to form a collective affective tone. Within a team, members’ emotions can be subtly and consciously contagious to one another (Barsade, 2002; Hatfield et al., 1994). This emotional contagion processes cause team members to gradually align emotionally while working together, shaping the formation of the team’s collective affective tone (Barsade, 2002; Bartel and Saavedra, 2000).

We propose that leader other-oriented perfectionism can lead to ambivalent affective tones at the team level due to the paradoxical nature of such leaders. Specifically, we posit that such leaders can simultaneously trigger both a team energy tone and a team anxious tone. Team energy tone is characterized by energetic, mentally refreshed, and enthusiastic collective affective experiences (Menges et al., 2017). Leaders’ demanding perfection from followers can increase team energy levels because when leaders set high expectations for work outcomes, it creates a sense of challenge and pushes the team to strive for excellence, thus leaders’ pursuit of perfection can fuel a sense of determination and drive in followers, inspiring team members to be more enthusiastic and energized to meet those standards at work. In line with the logic, previous study also found that when individuals perceive tasks as challenging, they are more likely to mobilize their energies to accomplish them (Tomaka et al., 1993).

Meanwhile, leaders can also evoke negative emotional experiences among team members (Nifadkar et al., 2012; Peng et al., 2019; Yu and Duffy, 2021). The demand for perfection from leaders can elicit anxious tone among team members, which represents a collective emotional experience characterized by feelings of being anxious, apprehensive, worried, and nervous (Brooks and Schweitzer, 2011; Kouchaki and Desai, 2015). Leaders who exhibit other-oriented perfectionism often establish elevated performance objectives and display a heightened level of scrutiny when evaluating the quality of team members’ work, allowing minimal margin for their errors, thus the high expectations for perfection can instill a worry of making mistakes or falling short of the desired standards (Hewitt and Flett, 1991; Smith et al., 2017). Team members may feel overwhelmed by the constant need to meet unrealistic standards and worry about the consequences of not meeting these expectations, such as criticism or negative consequences, resulting in increased team anxiety levels. Thus, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1a: Leader other-oriented perfectionism is positively related to team energy tone.

Hypothesis 1b: Leader other-oriented perfectionism is positively related to team anxious tone.

The Indirect Effect of Team Affective Tone on Team Outcomes

Literature on emotional contagion suggests that team collective affects generated by emotional contagion processes can influence team outcomes through affecting team emergent states and processes (Barsade, 2002). For example, positive emotional contagion can heighten team positive affect, thereby fostering increased cooperation and reduced conflict among team members (Barsade, 2002). This positive affect spreads goodwill within the group, leading to more desirable team emergent states and constructive behaviors (George and Brief, 1992). Conversely, negative emotional contagion reinforces team negative affect, exacerbating team dynamics (Barsade, 2002).

Consistent with the broader understanding of emotional contagion in team contexts, approach-avoidance emotivation theory (Beall and Tracy, 2017; Roseman, 2008) explains how emotional states triggered by environmental stimuli can drive human behaviors by shaping motivational systems. This theory identifies emotion and motivation as the two fundamental psychological elements driving human behaviors. Motivation is defined as the internal force propelling an individual’s behaviors toward a specific goal (Kleinginna and Kleinginna, 1981). For example, hunger drives an individual to seek food (Feather, 1982). Similarly, the need for achievement drives an individual to pursue success and recognition (Atkinson, 1964).

Emotions can impact motivation and take precedence over it in certain situations. For instance, when individuals experience fear, their exploratory motivation and achievement efforts may decrease (Fanselow and Lester, 1988). Similarly, when individuals are hopeful, they become more optimistic, motivated to plan for the future, and proactive in seeking opportunities (Roseman, 2008). This theory posits that emotions can trigger specific motivational behaviors through motivational states. Pleasure, for example, can increase eating and social motivation, while fear can trigger avoidance intentions (Frijda, 1986; Lazarus, 1991). Isen (2000) further underlines these positive emotions, such as happiness, can enhance individuals’ sensitivity to potential rewards, thus triggering more exploratory and participatory behaviors. These studies show that emotions can modulate the strength and direction of motivation and directly trigger behaviors. Therefore, emotion is an immediate response to environmental changes and a significant predecessor to motivation, capable of influencing or generating it.

Furthermore, the theory underscores the general distinctions between two types of motivation — approach motivation and avoidance motivation, and two types of emotions — positive and negative (Roseman, 2008). These distinctions are essential for understanding how individuals prioritize their actions in different conditions and predicting behavioral outcomes. Specifically, approach motivation involves seeking positive states or rewards, while avoidance motivation focuses on avoiding adverse conditions or penalties (Elliot, 1999). Similarly, positive emotions such as joy and love typically lead to engaging behaviors. In contrast, negative emotions like fear and sadness are more likely to result in defensive or avoidant behaviors.

Based on the rationale of approach-avoidance emotivation theory, we propose that team affective tones triggered by leader other-oriented perfectionism will impact team collective actions via team-level motivation. Particularly, we posit that team energy tone triggered by leader other-oriented perfectionism will lead to team prosocial behavior via team performance approach motivation. Team performance approach motivation is the collective drive that propels a team towards achieving shared goals, reflecting the shared perceptions among team members regarding the approach motivation towards performance (Elliot, 1999). The high level of team energy tone creates a sense of excitement and productivity-oriented motivation among team members (Chi et al., 2011; Wu and Wang, 2015). Team energy tone fosters a shared dedication to stimulating the team’s motivation to approach performance-related goals, as members are driven to contribute their utmost efforts, mutual help, and social support to achieve better team performance. Further, a strong team performance approach motivation cultivates a sense of shared identity and collective goals among team members, reinforcing team cohesion, encouraging collective efforts to achieve team objectives and overcome setbacks (Greer, 2012). As a result, team members are more likely to take actions that benefit the team’s overall performance under such cohesive states (Beal et al., 2003; Mathieu et al., 2015). This improvement in team prosocial behavior will occur as team members acknowledge that supporting and assisting each other contributes to the team’s success and helps everyone achieve their performance goals.

Meanwhile, team anxious tone stemmed from leader other-oriented perfectionism will result in team cheating behavior through team performance avoidance motivation. Team performance avoidance motivation represents the collective intent among team members to avoid failures, errors, and adverse outcomes in their performance (Elliot, 1999). Team anxious tone creates a sense of unease and caution within the team, leading to a tendency to avoid potential risks and negative outcomes (Cheng and McCarthy, 2018). This cautious approach influences decision-making and task execution, as team members prioritize preventing mistakes or failure over actively striving to achieve performance goals. The increase in team anxious tone further enhances team performance avoidance motivation, making members more concerned with avoiding errors and negative evaluations than with excelling in their performance. This heightened apprehension about unfavorable consequences may induce a greater inclination to partake in unethical behaviors (Kouchaki and Desai, 2015) as a means of sidestepping potential repercussions or adverse evaluations. Additionally, the desire to safeguard oneself from perceived risks or penalties can overshadow ethical considerations. Excessive levels of performance avoidance motivation can lead to a narrow focus on immediate gains and short-term results. This limited attention may prompt team members to engage in cheating behaviors that offer swift advantages or shortcuts to meet performance targets, disregarding the long-term consequences or ethical implications involved. Thus, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 2a: Leader other-oriented perfectionism is positively related to team prosocial behavior through the serial mediation of team energy tone and team performance approach motivation.

Hypothesis 2b: Leader other-oriented perfectionism is positively related to team cheating behavior through the serial mediation of team anxious tone and team performance avoidance motivation.

The Interactive Effect of Leader Other-Oriented Perfectionism and Team Trait Resilience on Team Affective Tone

Trait resilience encompasses the inherent ability of individuals to proficiently adjust and confront stress, grief, difficulty, or challenging circumstances (Block and Kremen, 1996; Smith et al., 2008). Resilience empowers individuals to manage stressful encounters constructively (Block and Kremen, 1996), shielding them from fixating on the negative aspects of stressors (Charney, 2004). Researchers and practitioners increasingly recognize resilience is a valuable resource that enables individuals to effectively navigate the constant challenges and stressful situations encountered in organizational life (Chen and Kanfer, 2024; Mathieu et al., 2019). If people have higher resilience, they will be better equipped to handle stress and recover from adverse situations (Waugh et al., 2011), because resilience leads to positive psychological states such as increased optimistic thinking (Kumpfer, 1999), induced challenge appraisal (Mitchell et al., 2019), and favorable work attitudes (Youssef and Luthans, 2007), which substantiates the significance of resilience as a valuable resource.

Personality traits can aggregate to the team level to form a collective team personality composition (LePine et al., 2011), which aligns with the additive model of construct composition (Chan, 1998), indicating that team-level personality is the result of adding up individual personalities, irrespective of the variations among individuals (Chiu et al., 2016). Based on previous operationalization about team personality compositions (Barrick et al., 1998; Bradley et al., 2013; Chiu et al., 2016), our research conceptualizes team resilience as the average trait resilience of team members, reflecting a collective tendency to endure or recover from difficult, demanding, and challenging situations. When a team possesses higher resilience, it demonstrates greater adaptability and resourcefulness in dealing with adversity and overcoming obstacles (Stoverink et al., 2020).

We propose that stronger team resilience strengthens the positive impact of leader other-oriented perfectionism on the team energy tone. Specifically, in a more resilient team, members are better equipped to handle and endure the high standards and strict requirements set by their perfectionist leaders, viewing these demands as inspiring challenges rather than burdens. The leader’s pursuit of perfectionism in team outcomes does not overwhelm a highly resilient team, as the team’s ability to effectively mobilize and acquire resources in challenging situations allows them to manage these strict standards. Instead, such requirements may invigorate the team members, enhancing their collective energy tone. Thus, a higher level of team resilience amplifies the positive relationship between leader other-oriented perfectionism and the team energy tone.

Meanwhile, when team resilience is higher, the positive relationship between leader other-oriented perfectionism and the team anxious tone diminishes. Higher-resilience teams benefit from stronger psychological regulation and interpersonal support systems (Stoverink et al., 2020; Troy et al., 2023), allowing them to better manage and mitigate negative emergent states induced by leaders’ strict requirements. Although a leader’s perfectionist demands may still create some psychological tensions, a resilient team can keep this influence at controllable levels through collective mutual support and effective stress management, preventing it from escalating into serious anxiety. Therefore, in highly resilient teams, the positive relationship between leader other-oriented perfectionism and team anxious tone is weakened.

On the other hand, compared to teams with higher resilience, when team resilience is lower, the teams’ limited resources and adaptive capacity hinder their ability to cope with the strict requirements from a perfectionist leader. This constraint weakens the positive relationship between the leader other-oriented perfectionism and team energy tone. Lower-resilience teams are more likely to feel stressed and hypervigilant by the high standards and strict expectations imposed by perfectionist leaders, perceiving these demands as overwhelming burdens rather than as inspiring challenges. In such cases, the fear of failing to meet the leader’s supreme expectations can drain the team’s energy levels. As a result, in teams with lower resilience, the positive relationship between leader other-oriented perfectionism and the team energy tone is less pronounced.

Similarly, the positive relationship between leader other-oriented perfectionism and team anxious tone intensifies in teams with lower resilience compared to those with higher resilience. Teams with lower resilience often lack sufficient psychological support and resources to manage stress effectively (Stoverink et al., 2020; Troy et al., 2023), which can exacerbate team anxious tone when faced with the perfectionist demands from their leader. In such a high-pressure environment, teams with lower resilience may become increasingly anxious about making mistakes or failing to meet expectations, leading to heightened collective anxiety. Therefore, in teams with lower resilience, the positive relationship between leader other-oriented perfectionism and the team anxious tone becomes stronger. Based on the above reasoning, we posit the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 3a: Team trait resilience moderates the positive relationship between leader other-oriented perfectionism and team energy tone, such that the relationship will be strengthened when team trait resilience is higher rather than lower.

Hypothesis 3b: Team trait resilience moderates the positive relationship between leader other-oriented perfectionism and team anxious tone, such that the relationship will be weakened when team trait resilience is higher rather than lower.

Integrating the moderating effects and chain mediation effects, we propose the following hypotheses of moderated mediation.

Hypothesis 4a: The serial mediation relationship between leader other-oriented perfectionism and team prosocial behavior (via team energy tone and team performance approach motivation) is stronger when team trait resilience is higher rather than lower.

Hypothesis 4b: The serial mediation relationship between leader other-oriented perfectionism and team cheating behavior (via team anxious tone and team performance avoidance motivation) is weaker when team trait resilience is higher rather than lower.

Method

Sample and Procedure

We collected data from a new energy company in China that specializes in battery products, energy storage systems, and integrated smart power solutions. We are committed to safeguarding the anonymity and confidentiality of the participants involved in this research. The human resources department helped us collect the data. When the paper and pencil survey was provided to the subjects, the subjects were informed it was voluntary. The entire sample collection was divided into four time points.

A total of 764 employees and 163 leaders participated in the field questionnaire. At Time 1, leaders rated their other-oriented perfectionism, demographic information, and control variables. Meanwhile, employees assessed their trait resilience and demographic information. At Time 2 (one month after Time 1), employees rated their team energy tone and team anxious tone. At Time 3 (one month after Time 2), employees rated their team performance approach motivation and team performance avoidance motivation. At Time 4 (one month after Time 3), employees rated their team prosocial behavior and team cheating behavior. In the end, 699 employees (a response rate of 91%) and 152 leaders (a response rate of 93%) provided complete responses. Among the final 699 employees, 66% were women, averaging 38.12 years-old (SD = 11.40), 49.36% had at least a vocational degree, and the average years of organizational tenure was 9.91 (SD = 7.18). Among the final 152 leaders, 72% were men, averaging 48.10 years-old (SD = 6.40), 61.18% had at least a bachelor degree, and the average years of organizational tenure was 15.02 (SD = 6.87).

Measures

If there were no special instructions, all items were measured on a seven-point Likert scale with a range from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 7 (“strongly agree”).

Leader other-oriented perfectionism

One 5-item scale from Hewitt and Flett (1991) was used to assess leader other-oriented perfectionism. Items were “I have high expectations for the people who are important to me,” “I have very high standards for those around me,” “If I ask someone to do something, I expect it to be done flawlessly,” “I can’t be bothered with people who won’t strive to better themselves,” and “The people who matter to me should never let me down.” The value of Cronbach’s α for the scale was 0.85.

Team trait resilience

Team trait resilience was measured with a 6-item scale from Smith et al. (2008). Items were “I tend to bounce back quickly after hard times,” “I don’t have a hard time making it through stressful events,” “It does not take me long to recover from a stressful event,” “It is easy for me to snap back when something bad happens,” “I usually come through difficult times with little trouble,” and “I tend to take a short time to get over set-backs in my life.” The scale had a Cronbach’s α value of 0.91. According to satisfactory interrater agreement (mean Rwg(j) = 0.90, median Rwg(j) = 0.92) and intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC1 = 0.63, F = 8.69, p < 0.001; ICC2 = 0.88) (Bliese, 2000; James et al., 1984), the responses provided by employees were aggregated to the team level.

Team energy tone

To measure team energy tone, we employed a 4-item scale from Menges et al. (2017). Team members indicated the extent to which members of their team experienced each following emotion “Energetic,” “Mentally refreshed,” “Enthusiastic,” and “Satisfied” in the past month at work. The scale ranged from 1 = “not at all” to 7 = “very much”. The scale’s Cronbach’s α was 0.85. The responses from employees were aggregated to the team level based on the satisfactory criteria of interrater agreement (mean Rwg(j) = 0.91, median Rwg(j) = 0.93) and intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC1 = 0.50, F = 5.54, p < 0.001; ICC2 = 0.82) (Bliese, 2000; James et al., 1984).

Team anxious tone

We used a 4-item scale from Brooks and Schweitzer (2011) to measure team anxious tone. Team members indicated the extent to which members of their team experienced each following emotion “Anxious,” “Apprehensive,” “Worried,” and “Nervous” in the past month at work. The scale ranges from 1 = “not at all” to 7 = “very much”. The scale’s Cronbach’s α was 0.88. The responses provided by employees were aggregated to the team level based on the satisfactory criteria of interrater agreement (mean Rwg(j) = 0.91, median Rwg(j) = 0.92) and intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC1 = 0.66, F = 10.00, p < 0.001; ICC2 = 0.90) (Bliese, 2000; James et al., 1984).

Team performance approach motivation

One 5-item scale adapted from Ferris et al. (2013) to assess team performance approach motivation, which was originally developed by Johnson and Chang (2008). Items were “Our goal at work is to fulfill our potential to the fullest in team performance,” “We are focused on successful experiences that would occur in team performance,” “In general, we tend to think about positive aspects of team performance,” “We see team performance as a way for us to fulfill our hopes, wishes, and aspirations,” and “We think about the positive outcomes that team performance can bring us.” The scale’s Cronbach’s α was 0.90. The responses provided by employees were aggregated to the group level based on the satisfactory criteria of interrater agreement (mean Rwg(j) = 0.91, median Rwg(j) = 0.93) and intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC1 = 0.67, F = 10.22, p < 0.001; ICC2 = 0.90) (Bliese, 2000; James et al., 1984).

Team performance avoidance motivation

One 4-item scale adapted from Ferris et al. (2013) to assess team performance avoidance motivation, which was originally developed by Johnson and Chang (2008). Items were “We are focused on failure experiences that would occur in team performance,” “We are fearful about failing to prevent negative team performance outcomes,” “In general, we tend to think about negative aspects of team performance,” and “We think about the negative outcomes associated with performing bad.” The Cronbach’s α was .83 for this scale. The responses provided by employees were aggregated to the team level based on the satisfactory criteria of interrater agreement (mean Rwg(j) = 0.91, median Rwg(j) = 0.93) and intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC1 = 0.51, F = 5.81, p < 0.001; ICC2 = 0.83) (Bliese, 2000; James et al., 1984).

Team prosocial behavior

Team prosocial behavior was assessed by employees with a 6-item scale from Smith et al. (1983). The scale ranges from 1 = “never” to 7 = “always”. Sample items were “Helps others who have been absent,” and “Volunteers for things that are not required.” The Cronbach’s α was 0.86 for this scale. The responses provided by employees were aggregated to the team level based on the satisfactory criteria of interrater agreement (mean Rwg(j) = 0.83, median Rwg(j) = 0.90) and intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC1 = 0.53, F = 6.11, p < 0.001; ICC2 = 0.84) (Bliese, 2000; James et al., 1984).

Team cheating behavior

Team cheating behavior was assessed by employees with a 7-item scale from Mitchell et al. (2018). The scale ranges from 1 = “never” to 7 = “always”. Sample items were “Made up work activity to look better,” and “Exaggerated work hours to look more productive.” The Cronbach’s α was 0.84 for this scale. The responses provided by employees were aggregated to the team level based on the satisfactory criteria of interrater agreement (mean Rwg(j) = 0.93, median Rwg(j) = 0.95) and intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC1 = 0.73, F = 13.49, p < 0.001; ICC2 = 0.93) (Bliese, 2000; James et al., 1984).

Control variable

Team size and tenure as the team leader were controlled in accordance with previous research on group research (Hu and Liden, 2015). Team size has been shown to affect members’ attitudes (Choi, 2007) and team processes (Richter et al., 2006). In addition, the tenure as the team leader reflects the duration of leadership (Chiu et al., 2016), which may affect team effectiveness (Sieweke and Zhao, 2015).

Analytic Strategy

First, as the variables were collected from both leader evaluations and employee evaluations, we conduct a series of multi-level confirmatory factor analyses to examine the discriminant validity among the variables. Then, we use SPSS software to perform descriptive statistical analysis of the variables, including means, standard deviations, correlation coefficients, and reliability coefficients. To further test our research hypotheses, since all the variables in this study are at the team level, we employ Mplus 7 software to conduct single-level path analysis. Specifically, to test the mediation effect and moderated mediation effect, we construct an overall mediation effect model and an overall moderated mediation effect model, respectively. The confidence intervals for the mediation effect and moderated mediation effect are estimated using 20,000 bootstrap resampling iterations in R software.

Results

CFA

The discriminative validity of the scale was tested by performing a multilevel confirmatory factor analysis (e.g., Liu et al., 2015) on the variables, which were provided by the leader and employees, including leader other-oriented perfectionism, team trait resilience, team energy tone, team anxious tone, team performance approach motivation, team performance avoidance motivation, team prosocial behavior, and team cheating behavior. The results indicated that the model fits of the 8-factor model exhibit goodness (χ2[578] = 725.10, RMSEA = 0.02, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.99) and were notably superior to other competing models, such as the 2-factor model, which combines variables at two different levels into one factor each (χ2[599] = 10558.42, RMSEA = 0.15, CFI = 0.18, TLI = 0.12). These findings indicate the presence of favorable discriminative validity within these variables.

Descriptive statistics

The Table 1 displays the means, standard deviations, correlation coefficients, and reliabilities for the variables.

Hypotheses testing

In Table 2A and B, two models for our hypothesis testing are presented, with Model 1 in Table 2A representing the mediating effects (overall model fits: χ2 = 0.27, df = 2, RMSEA = 0.00, CFI = 1.00, SRMR = 0.01), and Model 2 in Table 2B representing the moderated mediating effects (overall model fits: χ2 = 0.01, df = 2, RMSEA = 0.00, CFI = 1.00, SRMR = 0.00). Regarding Hypotheses 1a and 1b, the results in Table 2A indicated that leader other-oriented perfectionism is positively related to team energy tone (γ = 0.24, SE = 0.05, p < 0.001, Model 1), and leader other-oriented perfectionism is positively related to team anxious tone (γ = 0.24, SE = 0.07, p < 0.01, Model 1), supporting Hypotheses 1a and 1b.

Furthermore, team energy tone is positively related to team performance approach motivation (γ = 0.30, SE = 0.10, p < 0.01, Model 1), and team performance approach motivation is positively related to team prosocial behavior (γ = 0.21, SE = 0.09, p < 0.05, Model 1). The results in Table 3 showed that team energy tone and team performance approach motivation serially mediate the relationship between leader other-oriented perfectionism and team prosocial behavior (indirect effect = 0.02, SE = 0.01, 95% CI = [0.002, 0.036]). Hence, Hypothesis 2a was supported. Besides, team anxious tone is positively related to team performance avoidance motivation (γ = 0.19, SE = 0.06, p < 0.01, Model 1), and team performance avoidance motivation is positively related to team cheating behavior (γ = 0.52, SE = 0.09, p < 0.001, Model 1). The results in Table 3 showed that team anxious tone and team performance avoidance motivation serially mediate the relationship between leader other-oriented perfectionism and team cheating behavior (indirect effect = 0.02, SE = 0.01, 95% CI = [0.006, 0.051]). Hence, Hypothesis 2b was supported.

In addition, to test the moderating effect, as shown in Table 2B, we found the interaction of leader other-oriented perfectionism and team trait resilience was positively related to team energy tone (γ = 0.13, SE = 0.06, p < 0.05, Model 2). Then we applied Aiken and West’s (1991) method of probing this interaction by plotting +/– 1 SD around the mean. As evidenced in Fig. 2, the positive significance of the relationship between leader other-oriented perfectionism and team energy tone was found to be stronger under high team trait resilience condition (γ = 0.38, SE = 0.08, p < 0.001) than under low team trait resilience condition (γ = 0.16, SE = 0.06, p < 0.05). There was a significant difference between these two conditions (γ = 0.22, SE = 0.10, p < 0.05). As a result, Hypothesis 3a was supported. Furthermore, based on the results presented in Table 2B, we discovered the interaction of leader other-oriented perfectionism and team trait resilience was negatively related to team anxious tone (γ = –0.20, SE = 0.07, p < 0.01, Model 2). As depicted in Fig. 3, the relationship between leader other-oriented perfectionism and team anxious tone was observed to be more positively significant under low team trait resilience condition (γ = 0.36, SE = 0.09, p < 0.001) than under high team trait resilience condition (γ = 0.02, SE = 0.11, n.s.). There was a significant difference between these two conditions (γ = –0.34, SE = 0.13, p < 0.01). Therefore, Hypothesis 3b was supported.

At last, in the examination of moderated mediation effects, as illustrated in Table 3, the results indicated that team trait resilience moderates the serial indirect impact of leader other-oriented perfectionism on team prosocial behavior (indirect effectdiff = 0.01, SE = 0.01, 95% CI = [0.001, 0.037]) through team energy tone and team performance approach motivation, and team trait resilience moderates the serial indirect effect of leader other-oriented perfectionism on team cheating behavior (indirect effectdiff = –0.03, SE = 0.02, 95% CI = [–0.070, –0.003]) through team anxious tone and team performance avoidance motivation, supporting Hypotheses 4a and 4b.

Supplementary Analysis

In this study, leaders were also invited to assess team prosocial behavior and cheating behavior. Therefore, we conducted supplementary analyses of mediation effects and moderated mediation effects to enhance the robustness of the study’s conclusions. The results showed that team energy tone and team performance approach motivation serially mediate the relationship between leader other-oriented perfectionism and leader-rated team prosocial behavior (indirect effect = 0.02, SE = 0.01, 95% CI = [0.006, 0.050]). Hence, Hypothesis 2a was still supported. Besides, the results showed that team anxious tone and team performance avoidance motivation serially mediate the relationship between leader other-oriented perfectionism and leader-rated team cheating behavior (indirect effect = 0.02, SE = 0.01, 95% CI = [0.005, 0.050]). Hence, Hypothesis 2b was still supported. Furthermore, in the examination of moderated mediation effects, the results indicated that team trait resilience moderates the serial indirect effect of leader other-oriented perfectionism on leader-rated team prosocial behavior (indirect effectdiff = 0.02, SE = 0.01, 95% CI = [0.002, 0.053]) through team energy tone and team performance approach motivation, and team trait resilience moderates the serial indirect effect of leader other-oriented perfectionism on leader-rated team cheating behavior (indirect effectdiff = –0.03, SE = 0.02, 95% CI = [–0.069, –0.003]) through team anxious tone and team performance avoidance motivation, still supporting Hypotheses 4a and 4b. The results of hypothesis testing from both leader evaluations and self-evaluations of the dependent variables support the hypotheses of this study, further demonstrating the robustness of our research conclusions.

Discussion

Main Findings

According to the literature on perfectionism (Hewitt and Flett, 1991; Xu et al., 2022) and the approach-avoidance emotivation theory (Beall and Tracy, 2017; Roseman, 2008), we examined the theoretical mechanisms and the boundaries of the impact of leader other-oriented perfectionism on team prosocial and cheating behavior. Specifically, with full responses from 152 leaders and 699 employees, this study reveals significant findings regarding the impact of leader other-oriented perfectionism on team dynamics and behaviors. In particular, leader other-oriented perfectionism is positively associated with both team energy tone and team anxious tone. Moreover, it promotes team prosocial behavior through a sequential mediation pathway involving team energy tone and team performance approach motivation. At the same time, it predicts team cheating behavior via team anxious tone and team performance avoidance motivation. Importantly, team trait resilience moderates these relationships: higher team trait resilience strengthens the positive association between leader other-oriented perfectionism and team energy tone, weakens its association with team anxious tone, and amplifies the serial mediation effects on team prosocial behavior while attenuating those on cheating behavior. These findings underscore the interactive influence of leader perfectionism and team resilience on team dynamics and ethical behaviors within organizational settings.

Theoretical Implications

This research makes four significant theoretical contributions. First, our research enriches the literature about the impact of leader other-oriented perfectionism on team outcomes. Previous studies have primarily focused on the effects of leader other-oriented perfectionism on leader themselves, such as reduced transformational leadership (Otto et al., 2021), and follower-centered outcomes, such as follower creativity (Xu et al., 2022). However, few studies have examined the impact of leader other-oriented perfectionism on important team outcomes. Responding to Ocampo et al.’s (2020) call for more research on the team-level effects of perfectionism, we explore how leader other-oriented perfectionism influences collective ethical actions within teams. This expands our understanding of both the positive and negative aspects of such perfectionism on teams and its potential to drive significant team outcomes. Particularly, we draw on the literature on perfectionism (Hewitt and Flett, 1991; Xu et al., 2022) and approach-avoidance emotivation theory (Beall and Tracy, 2017; Roseman, 2008) to argue that leader other-oriented perfectionism can trigger paradoxical team outcomes through ambivalent team affective tone and team motivational states. Therefore, we advance the literature on perfectionism by linking leader other-oriented perfectionism to team-level behaviors and by scrutinizing the underlying theoretical mechanisms and boundaries.

Second, we introduce the emotivation perspective to explain the impact of leader other-oriented perfectionism on team outcomes. Previous studies on leader perfectionism mainly focused on the cognitive states of subordinates stimulated by these leaders, such as change of employee creativity (Xu et al., 2022), while often ignoring key emotional mechanisms. While studies of individual-level emotion are very common (e.g., Nifadkar et al., 2012), the factors shaping group-based emotion remain largely unknown (Cole et al., 2008; Porat et al., 2016). Our study integrates these meaningful research trends and clarifies the impact of leader other-oriented perfectionism on team outcomes from a collective emotional perspective, extending beyond the previous theoretical framework on leader perfectionism. Additionally, previous studies mainly used goal-setting theory (e.g., Hrabluik et al., 2012; Van Yperen et al., 2011), conservation of resources theory (e.g., Deuling and Burns, 2017; Flaxman et al., 2012), transactional model of stress and coping (Dunkley et al., 2014), and self-regulation theory (e.g., Xu et al., 2022) to examine the influence of other-oriented perfectionism. However, we integrate the literature on perfectionism (Hewitt and Flett, 1991; Xu et al., 2022) and approach-avoidance emotivation theory (Beall and Tracy, 2017; Roseman, 2008), which goes beyond existing theoretical perspectives on leader perfectionism, providing valuable insights into its theoretical implications for team dynamics.

Third, our study responded to the call for more research on determinants of team unethical behavior. Although unethical behavior has been seen as individual or collective phenomenon, compared with individual-level research, more empirical exploration is needed at the collective level (Kuenzi et al., 2020; Mayer et al., 2009; Pearsall and Ellis, 2011). Immoral decisions contributing to organizational downfall were always made and performed collectively at different levels in the organization (Anand et al., 2004; Kulik et al., 2008; Robinson and O’Leary-Kelly, 1998), and it is very necessary to clarify the motivators of misconducts from a team-level perspective (Brown and Treviño, 2006; Chen et al., 2020; Pearsall and Ellis, 2011). On the basis of this valuable direction, our study extends the research on leadership antecedents of unethical behaviors (Ambrose et al., 2013) by identifying critical but underexplored leader personality traits (Mayer et al., 2012).

Fourth, this study aims to broaden the understanding of team trait resilience in work environments that demand perfection. Research on resilience mostly focuses on individual-level resilience, with less attention given to resilience at the team level (Stoverink et al., 2020). This study may expand the understanding of team-level resilience. Although a few scholars have delved into the positive outcomes it brings to teams (Meneghel et al. 2016; Meneghel et al., 2016; Salanova et al., 2012), the impact of team trait resilience on team processes and outcomes remains underexamined. Research on team resilience has revealed that teams with these characteristics can achieve success even when confronted with considerable challenges (Lawrence and Maitlis, 2012; Stoverink et al., 2020; Stuart and Moore, 2017). Our research examines the interactive influence of leader other-oriented perfectionism and team trait resilience on team affective tones, motivations, and behaviors, offering valuable insights for navigating the paradoxical consequences of leaders’ excessive pursuit of perfection.

Practical Implications

Our research findings offer valuable practical contributions. First, leaders need to deeply recognize that other-oriented perfectionism can have a double-edged impact on crucial team outcomes. On one hand, other-oriented perfectionist leaders can enhance team energy and approach motivation, leading to prosocial behavior. On the other hand, their zero-tolerance for mistakes and strict scrutiny can induce anxiety and avoidance motivation, resulting in unethical team behaviors. To avoid these pitfalls for teams, leaders should set reasonable and achievable goals for their teams. Meanwhile, they should adopt a positive mindset, recognizing that mistakes, errors, and failures in team work can serve as stepping stones toward excellence and high-level performance (Park et al., 2022).

Second, other-oriented perfectionist leaders should actively manage team anxiety and establish clear ethical standards to prevent the team from succumbing to stress and unethical temptations due to extreme demands. To mitigate these risks, leaders need to show genuine concern for their team members, monitor their work progress, and provide sufficient task-related and social support. Additionally, organizations should closely monitor the affective tone of teams and implement stress management programs to alleviate anxiety. Organizing ethical training programs can also be beneficial, helping employees understand the importance of maintaining ethical standards and integrity. These initiatives can help buffer the negative impacts of leader other-oriented perfectionism on the team.

Third, organizations should recognize the crucial role of team resilience in overcoming adversity, such as working under an other-oriented perfectionist leader, and in continuously creating value even in stressful situations. Meanwhile, they should take initiatives to build and strengthen team resilience. By focusing on resilience, organizations can enhance their ability to navigate obstacles and challenges and ensure sustainable competitive advantages.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

First, although our study examined two types of emotions including energy and anxiety, it is possible that there are other types of emotions that can be affected by leader perfectionism, such as the highly activated negative emotion—anger (Russell, 1980). When leaders ask employees to do things too perfectly, they may think that the leaders intentionally embarrass them, or make employees feel that they can’t achieve the requirements of the leaders, so they have strong negative emotions, and thus become hostile to the managers. Future research could explore more types of positive and negative emotions to deepen our understanding of the impact of leader perfectionism on group emotions.

Second, future research needs to explore more team processes to better understand the impact of perfectionism on teams, such as team cohesion (Casey-Campbell and Martens, 2009). Team cohesion is another potential explanatory mechanism that can enhance overall team performance (Beal et al., 2003), but it also has the potential to foster collective unethical behavior, such as mutual support and assistance in unethical acts within the team, which warrants further exploration in future research.

Additionally, the study was conducted in a specific organizational context and culture, and therefore the findings may not be generalizable to other settings. Our sample was drawn only from an Asian company, limiting the generalizability of our findings. Future research should examine the relationship between leader perfectionism and team emotions using longitudinal designs and larger, more diverse samples. Future research could be conducted in different organizational contexts and cultures to examine the generalizability of the current findings.

Finally, although we controlled for the team size and tenure as the team leader, we did not include many control variables, such as general positive and negative emotions, team prosocial motivation, team cohesion. Prior studies have shown that team prosocial motivation (Hu and Liden, 2015) and team cohesion influence team effectiveness (Grossman et al., 2022). Future research could consider adding these variables to rule out their effects. Additionally, future research could explore more boundary conditions. For example, high levels of team self-efficacy could enhance team confidence in coping with stress by fostering a positive outlook and a can-do attitude (Durham et al., 1997; Goncalo et al., 2010). This helps teams better manage stress and adversity, potentially buffering the negative effects of perfectionism and amplifying its positive effects.

Conclusion

Drawing from the literature on perfectionism and the approach-avoidance emotivation theory, this study examined how leader other-oriented perfectionism influences team ethical/unethical behaviors, as well as its boundary conditions. The results showed that leader other-oriented perfectionism positively affected team energy tone, leading to increased approach motivation and prosocial behavior. However, it was also associated with team anxious tone, which increased avoidance motivation and cheating behavior. Notably, team resilience strengthened the positive effect and weakened the negative effect of leader perfectionism, underscoring its role in balancing the paradoxical impacts of such leadership.

Data availability

We have reported our sampling plan and all measures of the study, and complied with the methodological checklist of the Humanities & Social Sciences Communications. However, to uphold the promised confidentiality and anonymity to the participants, the original data is not available.

References

Aiken LS, West SG (1991) Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage

Alliger GM, Cerasoli CP, Tannenbaum SI, Vessey WB (2015) Team resilience: How teams flourish under pressure. Organ Dyn 44(3):176–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2015.05.003

Ambrose ML, Schminke M, Mayer DM (2013) Trickle-down effects of supervisor perceptions of interactional justice: A moderated mediation approach. J Appl Psychol 98(4):678–689. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032080

Anand V, Ashforth BE, Joshi M (2004) Business as usual: The acceptance and perpetuation of corruption in organizations. Acad Manag Perspect 18(2):39–53. https://doi.org/10.5465/ame.2004.13837437

Atkinson, JW (1964) An introduction to achievement motivation. Princeton, NJ: Van Nostrad

Barrick MR, Stewart GL, Neubert MJ, Mount MK (1998) Relating member ability and personality to work-team processes and team effectiveness. J Appl Psychol 83(3):377–391. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.83.3.377

Barsade SG (2002) The ripple effects: Emotional contagion and its influence on group behavior. Adm Sci Q 47(4):644–675. https://doi.org/10.2307/3094912

Bartel CA, Saavedra R (2000) The collective construction of work group moods. Adm Sci Q 45(2):197–231. https://doi.org/10.2307/2667070

Beal DJ, Cohen RR, Burke MJ, McLendon CL (2003) Cohesion and performance in groups: A meta-analytic clarification of construct relations. J Appl Psychol 88(6):989–1004. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.6.989

Beall AT, Tracy JL (2017) Emotivational psychology: How distinct emotions facilitate fundamental motives. Soc Personal Psychol Compass 11(2):1–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12303

Bliese PD (2000) Within-group agreement, non-independence, and reliability: Implications for data aggregation and analysis. In: Klein KJ, Kozlowski SWJ (eds) Multilevel theory, research, and methods in organizations: Foundations, extensions, and new directions. San Francisco, Jossey-Bass, p 349–381

Block J, Kremen AM (1996) IQ and ego-resiliency: Conceptual and empirical connections and separateness. J Pers Soc Psychol 70(2):349–361. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.70.2.349

Bradley BH, Klotz AC, Postlethwaite BE, Brown KG (2013) Ready to rumble: How team personality composition and task conflict interact to improve performance. J Appl Psychol 98(2):385–392. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029845

Brooks AW, Schweitzer ME (2011) Can Nervous Nelly negotiate? How anxiety causes negotiators to make low first offers, exit early, and earn less profit. Organ Behav Hum Dec 115(1):43–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2011.01.008

Brown ME, Treviño LK (2006) Socialized charismatic leadership, values congruence, and deviance in work groups. J Appl Psychol 91(4):954–962. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.4.954

Bycio P, Hackett RD, Allen JS (1995) Further assessments of Bass’s (1985) conceptualization of transactional and transformational leadership. J Appl Psychol 80(4):468–478. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.80.4.468

Casey-Campbell M, Martens ML (2009) Sticking it all together: A critical assessment of the group cohesion–performance literature. Int J Manag Rev 11(2):223–246. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2008.00239.x

Chan D (1998) Functional relations among constructs in the same content domain at different levels of analysis: A typology of composition models. J Appl Psychol 83(2):234–246. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.83.2.234

Charney DS (2004) Psychobiological mechanisms of resilience and vulnerability: Implications for successful adaptation to extreme stress. Am J Psychiat 161(2):195–216. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.161.2.195

Chen A, Treviño LK, Humphrey SE (2020) Ethical champions, emotions, framing, and team ethical decision making. J Appl Psychol 105(3):245–273. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000437

Chen G, Kanfer R (2024) The future of motivation in and of teams. Annu Rev Organ Psychol Organ Behav 11(1):93–112. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-111821-031621

Cheng BH, McCarthy JM (2018) Understanding the dark and bright sides of anxiety: A theory of workplace anxiety. J Appl Psychol 103(5):537–560. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000266

Chi NW, Chung YY, Tsai WC (2011) How do happy leaders enhance team success? The mediating roles of transformational leadership, group affective tone, and team processes. J Appl Soc Psychol 41(6):1421–1454. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2011.00767.x

Chiu CYC, Owens BP, Tesluk PE (2016) Initiating and utilizing shared leadership in teams: The role of leader humility, team proactive personality, and team performance capability J Appl Psychol 101(12):1705–1720. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000159

Choi JN (2007) Change-oriented organizational citizenship behavior: Effects of work environment characteristics and intervening psychological processes. J Organ Behav 28(4):467–484. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.433

Cîrșmari MI, Rus CL, Trif SR, Fodor OC (2023) The leader’s other-oriented perfectionism, followers’ job stress and workplace well-being in the context of multiple team membership: The moderator role of pressure to be performant. Cogn Brain Behav 27(2):145–171. https://doi.org/10.24193/cbb.2023.27.07

Cole MS, Walter F, Bruch H (2008) Affective mechanisms linking dysfunctional behavior to performance in work teams: A moderated mediation study. J Appl Psychol 93(5):945–958. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.93.5.945

Cooper CD, Kong DT, Crossley CD (2018) Leader humor as an interpersonal resource: Integrating three theoretical perspectives. Acad Manag J 61(2):769–796. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2014.0358

Deuling JK, Burns L (2017) Perfectionism and work-family conflict: Self-esteem and self-efficacy as mediator. Pers Indiv Differ 116:326–330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.05.013

Dunkley DM, Ma D, Lee IA, Preacher KJ, Zuroff DC (2014) Advancing complex explanatory conceptualizations of daily negative and positive affect: Trigger and maintenance coping action patterns. J Couns Psychol 61(1):93–109. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034673

Durham CC, Knight D, Locke EA (1997) Effects of leader role, team-set goal difficulty, efficacy, and tactics on team effectiveness. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 72(2):203–231. https://doi.org/10.1006/obhd.1997.2739

Elliot AJ (1999) Approach and avoidance motivation and achievement goals. Educ Psychol 34(3):169–189. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep3403_3

Fanselow MS, Lester LS, Helmstetter FJ (1988) Changes in feeding and foraging patterns as an antipredator defensive strategy: A laboratory simulation using aversive stimulation in a closed economy. J Exp Anal Behav 50(3):361–374. https://doi.org/10.1901/jeab.1988.50-361

Feather NT (1982) Expectations and actions: Expectancy-value models in psychology. Routledge, London

Ferris DL, Johnson RE, Rosen CC, Djurdjevic E, Chang CHD, Tan JA (2013) When is success not satisfying? Integrating regulatory focus and approach/avoidance motivation theories to explain the relation between core self-evaluation and job satisfaction. J Appl Psychol 98(2):342–353. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029776

Flaxman PE, Ménard J, Bond FW, Kinman G (2012) Academics’ experiences of a respite from work: Effects of self-critical perfectionism and perseverative cognition on postrespite well-being. J Appl Psychol 97(4):854–865. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028055

Frijda NH (1986) The emotions. Cambridge University Press, New York

George JM (1990) Personality, affect, and behavior in groups. J Appl Psychol 75(2):107–116. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.75.2.107

George JM, Brief AP (1992) Feeling good-doing good: A conceptual analysis of the mood at work-organizational spontaneity relationship. Psychol Bull 112(2):310–329. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.112.2.310

Goncalo JA, Polman E, Maslach C (2010) Can confidence come too soon? Collective efficacy, conflict and group performance over time. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 113(1):13–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2010.05.001

Greer LL (2012) Group cohesion: Then and now. Small Group Re 43(6):655–661. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046496412461532

Grossman R, Nolan K, Rosch Z, Mazer D, Salas E (2022) The team cohesion-performance relationship: A meta-analysis exploring measurement approaches and the changing team landscape. Organ Psychol Rev 12(2):181–238. https://doi.org/10.1177/20413866211041157

Hatfield, E, Cacioppo, JT, Rapson, RL (1994) Emotional Contagion. Cambridge University Press, New York

Hewitt PL, Flett GL (1991) Perfectionism in the self and social contexts: Conceptualization, assessment, and association with psychopathology. J Pers Soc Psychol 60(3):456–470. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.60.3.456

Hillebrandt A, Barclay LJ (2020) How cheating undermines the perceived value of justice in the workplace: The mediating effect of shame. J Appl Psychol 105(10):1164–1180. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000485

Hrabluik C, Latham GP, McCarthy JM (2012) Does goal setting have a dark side? The relationship between perfectionism and maximum versus typical employee performance. Int Public Manag J 15(1):5–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/10967494.2012.684010

Hu J, Liden RC (2015) Making a difference in the teamwork: Linking team prosocial motivation to team processes and effectiveness. Acad Manag J 58(4):1102–1127. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2012.1142

Isen, AM (2000) Positive affect and decision making. In: Lewis M, Haviland-Jones J (eds) Handbook of emotions, 2nd ed. Guilford, New York, p 417–435

James LR, Demaree RG, Wolf G (1984) Estimating within-group interrater reliability with and without response bias. J Appl Psychol 69(1):85–98. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.69.1.85

Johnson, RE, Chang, CH (2008) Development and validation of a work-based regulatory focus scale. Paper presented at the 23rd Annual Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology Conference, San Francisco, CA

Kish-Gephart JJ, Harrison DA, Treviño LK (2010) Bad apples, bad cases, and bad barrels: Meta-analytic evidence about sources of unethical decisions at work. J Appl Psychol 95(1):1–31. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017103

Kleinginna PR, Kleinginna AM (1981) A categorized list of motivation definitions, with a suggestion for a consensual definition. Motiv Emot 5(3):263–291. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00993889

Kouchaki M, Desai SD (2015) Anxious, threatened, and also unethical: How anxiety makes individuals feel threatened and commit unethical acts. J Appl Psychol 100(2):360–375. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037796

Kuenzi M, Mayer DM, Greenbaum RL (2020) Creating an ethical organizational environment: The relationship between ethical leadership, ethical organizational climate, and unethical behavior. Pers Psychol 73(1):43–71. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12356

Kulik BW, O’ Fallon MJ, Salimath MS (2008) Do competitive environments lead to the rise and spread of unethical behavior? Parallels from Enron. J Bus Ethics 83(4):703–723. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-007-9659-y

Kumpfer, KL (1999) Factors and processes contributing to resilience: The resilience framework. In: Glantz MD, Johnson JL (eds) Resilience and development: Positive life adaptations. Kluwer Academic/Plenum, New York, p 179–224

Lawrence TB, Maitlis S (2012) Care and possibility: Enacting an ethic of care through narrative practice. Acad Manag Rev 37(4):641–663. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2010.0466

Lazarus, RS (1991) Emotion and adaptation. Oxford University Press, New York

Lemoine GJ, Hartnell C, Leroy H (2019) Taking stock of moral approaches to leadership: An integrative review of ethical, authentic, and servant leadership. Acad Manag Ann 13(1):148–187. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2016.0121

LePine JA, Buckman BR, Crawford ER, Methot JR (2011) A review of research on personality in teams: Accounting for pathways spanning levels of theory and analysis. Hum Resour Manag R 21(4):311–330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2010.10.004

LePine MA, Zhang Y, Crawford ER, Rich BL (2016) Turning their pain to gain: Charismatic leader influence on follower stress appraisal and job performance. Acad Manag J 59(3):1036–1059. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2013.0778

Liu S, Wang M, Bamberger P, Shi J, Bacharach SB (2015) The dark side of socialization: A longitudinal investigation of newcomer alcohol use. Acad Manag J 58(2):334–355. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2013.0239

Mathieu JE, Gallagher PT, Domingo MA, Klock EA (2019) Embracing complexity: Reviewing the past decade of team effectiveness research. Annu Rev Organ Psychol Organ Behav 6:17–46. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-012218-015106

Mathieu JE, Kukenberger MR, D’Innocenzo L, Reilly G (2015) Modeling reciprocal team cohesion–performance relationships, as impacted by shared leadership and members’ competence. J Appl Psychol 100(3):713–734. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038898

Mayer DM, Aquino K, Greenbaum RL, Kuenzi M (2012) Who displays ethical leadership, and why does it matter? An examination of antecedents and consequences of ethical leadership. Acad Manag J 55(1):151–171. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2008.0276

Mayer DM, Kuenzi M, Greenbaum R, Bardes M, Salvador RB (2009) How low does ethical leadership flow? Test of a trickle-down model. Organ Behav Hum Dec 108(1):1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2008.04.002

Mejia Z (2018) The surprising reason Jeff Bezos loves bad reviews from ‘divinely discontent’ Amazon customers. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2018/04/19/why-jeff-bezos-loves-bad-reviews-from-discontent-amazon-customers.html. Accessed 19 Apr 2018

Meneghel I, Martínez IM, Salanova M (2016) Job-related antecedents of team resilience and improved team performance. Pers Rev 45(3):505–522. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-04-2014-0094

Meneghel I, Salanova M, Martínez IM (2016) Feeling good makes us stronger: How team resilience mediates the effect of positive emotions on team performance. J Happiness Stud 17(1):239–255. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-014-9592-6

Menges JI, Tussing DV, Wihler A, Grant AM (2017) When job performance is all relative: How family motivation energizes effort and compensates for intrinsic motivation. Acad Manag J 60(2):695–719. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2014.0898

Mitchell MS, Baer MD, Ambrose ML, Folger R, Palmer NF (2018) Cheating under pressure: A self-protection model of workplace cheating behavior. J Appl Psychol 103(1):54–73. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000254

Mitchell MS, Greenbaum RL, Vogel RM, Mawritz MB, Keating DJ (2019) Can you handle the pressure? The effect of performance pressure on stress appraisals, self-regulation, and behavior. Acad Manag J 62(2):531–552. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2016.0646

Newport C (2019) Steve Jobs never wanted us to use our iphones like this. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/01/25/opinion/sunday/steve-jobs-never-wanted-us-to-use-our-iphones-like-this.html. Accessed 25 January 2019

Nifadkar S, Tsui AS, Ashforth BE (2012) The way you make me feel and behave: Supervisor-triggered newcomer affect and approach-avoidance behavior. Acad Manag J 55(5):1146–1168. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.0133

Ocampo ACG, Wang L, Kiazad K, Restubog SLD, Ashkanasy NM (2020) The relentless pursuit of perfectionism: A review of perfectionism in the workplace and an agenda for future research. J Organ Behav 41(2):144–168. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2400

Otto K, Geibel HV, Kleszewski E (2021) Perfect leader, perfect leadership?” Linking leaders’ perfectionism to monitoring, transformational, and servant leadership behavior. Front Psychol 12:657394. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.657394

Park B, Lehman DW, Ramanujam R (2022) Driven to distraction: The unintended consequences of organizational learning from failure caused by human error. Organ Sci 34(1):283–302. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2022.1573

Pearsall MJ, Ellis APJ (2011) Thick as thieves: The effects of ethical orientation and psychological safety on unethical team behavior. J Appl Psychol 96(2):401–411. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021503

Peng ACM, Schaubroeck J, Chong S, Li Y (2019) Discrete emotions linking abusive supervision to employee intention and behavior. Pers Psychol 72(3):393–419. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12310

Pincus AL, Ansell EB (2003) Interpersonal theory of personality. In: Millon T, Lerner MJ (eds) Handbook of psychology: Personality and social psychology. John Wiley and Sons, New York, p 209–229

Porat R, Halperin E, Tamir M (2016) What we want is what we get: Group-based emotional preferences and conflict resolution. J Pers Soc Psychol 110(2):167–190. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspa0000043

Putnam LL, Fairhurst GT, Banghart S (2016) Contradictions, dialectics, and paradoxes in organizations: A constitutive approach. Acad Manag Ann 10(1):65–171. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520.2016.1162421

Resick CJ, Whitman DS, Weingarden SM, Hiller NJ (2009) The bright-side and the dark-side of CEO personality: Examining core self-evaluations, narcissism, transformational leadership, and strategic influence. J Appl Psychol 94(6):1365–1381. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016238

Richter AW, West MA, Van Dick R, Dawson JF (2006) Boundary spanners’ identification, intergroup contact, and effective intergroup relations. Acad Manag J 49(6):1252–1269. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMJ.2006.23478720

Robinson SL, O’ Leary-Kelly AM (1998) Monkey see, monkey do: The influence of work groups on the antisocial behavior of employees. Acad Manag J 41(6):658–672. https://doi.org/10.2307/256963

Rodell JB, Judge TA (2009) Can “good” stressors spark “bad” behaviors? The mediating role of emotions in links of challenge and hindrance stressors with citizenship and counterproductive behaviors. J Appl Psychol 94(6):1438–1451. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016752

Roseman IJ (2008) Motivations and emotivations: Approach, avoidance, and other tendencies in motivated and emotional behavior. In: Elliot AJ (ed) Handbook of approach and avoidance motivation. Psychology Press, New York, p 343–366

Russell JA (1980) A circumplex model of affect. J Pers Soc Psychol 39(6):1161–1178. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0077714

Salanova M, Llorens S, Cifre E, Martínez IM (2012) We need a hero! Toward a validation of the HEalthy and Resilient Organization (HERO) Model. Group Organ Manag 37(6):785–822. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601112470405

Schad J, Lewis MW, Raisch S, Smith WK (2016) Paradox research in management science: Looking back to move forward. Acad Manag Ann 10(1):5–64. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520.2016.1162422

Shoss MK, Callison K, Witt LA (2015) The effects of other‐oriented perfectionism and conscientiousness on helping at work. Appl Psychol -Int Rev 64(1):233–251. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12039

Sieweke J, Zhao B (2015) The impact of team familiarity and team leader experience on team coordination errors: A panel analysis of professional basketball teams. J Organ Behav 36(3):382–402. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1993

Smith BW, Dalen J, Wiggins K, Tooley E, Christopher P, Bernard J (2008) The brief resilience scale: Assessing the ability to bounce back. Int J Behav Med 15(3):194–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705500802222972