Abstract

The aim of this article was to examine changes in trainee translators’ web-based resource use patterns during a four-month English-to-Chinese translation practice course. An analytical framework was employed to statistically examine resource use development, including new and emerging resources. The research design incorporated four repeated measures with a cohort of 19 participants, and data were collected via the simultaneous use of a key logger and a screen recorder in a remote setting. A quality assessment was conducted to investigate the correlation between resource use and the overall quality of the final translation products. Findings indicate a shift in resource preference from dictionaries to knowledge-based resources, with trainee translators focusing on larger contextual issues rather than lexical problems. The quality assessment revealed a slight negative correlation between the translation error scores and the percentage of time allocated to knowledge-based resources. These findings highlight the importance of understanding trainee translators’ shifting resource use and evaluating their resource competence. The implications of the findings for translator training are discussed, and the need to adapt training programs to meet changing resource landscapes emphasized.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In today’ digital era, translators operate in a highly technologized environment (Chan 2023; O’Hagan 2019; Rothwell et al. 2023), enriched by diverse online tools and resources (e.g., Corpas Pastor and Durán-Muñoz 2018) that offer advanced capabilities to facilitate translation processes. The ability to navigate, retrieve, and critically evaluate web-based resources has therefore become a fundamental digital competency, not only in Translation Studies but across various disciplines. For both trainee and professional translators these skills are crucial for acquiring specialized knowledge, phraseology, and terminology across diverse domains, and to enable them to produce high-quality translations effectively and confidently (EMT 2022; Göpferich et al. 2009; PACTE 2011).

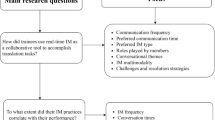

Despite its importance, research on how translators utilize web-based resources, particularly how their resource use evolves over time, remains limited. Understanding these patterns can provide valuable insights into the development of translation competencies and guide the design of targeted training programs. The aim of this study was to address this gap by examining the evolution of trainee translators’ web-based resource use throughout an English-to-Chinese translation practice course. Specifically, the following areas of research were explored:

-

What types of resources do trainee translators use, and how much time is spent on each type?

-

How does their use of these resources change over the course of a semester?

-

What is the relationship between resource use (types and duration) and the quality of translations produced?

The aim of the study is to inform translator training programs, by offering strategies to enhance the ability of trainee translators to engage with web-based resources effectively by an investigation of these questions.

The rapid evolution of translation technologies further underscores the importance of understanding web-based resource use in contemporary translator training. AI-driven tools, such as neural machine translation systems, AI-powered search engines, and generative large language models (LLMs) have significantly reshaped the translation landscape (Hendy et al. 2023; Jiao et al. 2023; Siu 2023; Wang et al. 2023). These technologies, exemplified by tools like ChatGPT, which emerged after the study’s completion, represent a paradigm shift toward conversational AI in translation workflows. While revolutionary, these tools bring unique challenges such as the need to ensure domain-specific accuracy, cultural adaptability, and contextual specificity, which highlights the continued need for critical engagement with traditional web-based resources.

In this evolving technological landscape, the relevance of traditional web searches is however still retained. They offer several complementary advantages, in that they enable translators to tailor their searches, access diverse domain-specific information, and to develop a more granular understanding of complex tasks. These traditional searches address gaps left by AI tools, which may struggle with cultural sensitivity, context-dependent adaptation, and highly specialized terminology. Traditional web searches also foster critical thinking and decision-making which are key competencies for producing high-quality translations.

The importance of this study is emphasized by a focus on the enduring strengths of web-based resource use, even as AI continues to reshape translation workflows. An investigation of how trainee translators engage with these resources over time that will equip future professionals with valuable insights to navigate the complexities of translation in an era of rapid technological advancement.

The structure of the paper is as follows: In Section “The role of resource use in translation”, existing research on web-based resource use is reviewed, including the challenges that are met in categorizing resources and their implications for translation practices. In Section “Methodology”, the study’s methodology is outlined, with details of the research design, participant background, and the tools used for data collection. In Section “Data analysis and discussion”, the results are presented, and the observed trends in resource usage, granular analyses of resource categories, and correlations between resource use and translation quality are discussed. In Section “Conclusion and insights for future training andresearch”, the conclusions are presented with key insights, implications for translator training, and recommendations for future research.

The aim of this study is to contribute to enhancing the digital competencies essential in the modern translation industry by bridging the gap in knowledge on the evolving patterns of resource use among trainee translators.

The role of resource use in translation

The increasingly technologized landscape of modern translation has caused the introduction of an unprecedented variety of web-based resources, designed to enable translators to better access specialized knowledge, terminology, and contextual information critical to producing high-quality translations. As the effective navigation and evaluation of these resources have become cornerstones of digital literacy, research in Translation Studies has been increasingly focussed on the examination of resource use, and diverse resource categorizations tailored to specific translation contexts have been proposed (e.g., Chang 2018; Whyatt et al. 2021; Hvelplund 2023).

The lack of a universal typology underscores the variability inherent in translation tasks, and the resource categorization in this domain reflects the diverse and evolving needs of translation practitioners. For example, Hvelplund (2023) identified institutional tools like the EURAMIS Concordance tool and EUR-Lex repository as dominant resources among European Commission in-house translators. Whyatt et al. (2021) highlighted challenges posed by unequal resource availability across languages, while Chang (2018), from a study on tourist texts emphasized the value of specialized resources like Google Maps for retrieving location-specific details.

Despite these contextual complexities, scholarly efforts to analyse and categorize translation resources persist, driven by the increasing accessibility of web-based resources and ongoing technological advancements. While resource typologies offer valuable frameworks, their applicability is often limited by contextual factors, including, the availability of tools for less commonly spoken languages and translators’ varying levels of expertise.

Challenges in resource categorization

Efforts to classify translation resources typically adopt one of two approaches: one-level or two-level categorizations. Each has distinct strengths and limitations for resource use analysis.

One-level categorizations

One-level frameworks list resources without hierarchical structuring and offer simplicity but often lack depth for comparative analysis. For instance, Daems et al. (2016) consolidated nine resource categories used in Translation from Scratch (TfS) and Machine Translation Post-Editing (MTPE) into four broad types: dictionaries, concordancers, encyclopaedias, and an “other” category, which included resources like news websites, conversion tools, term banks, spelling aids, synonyms, and machine translation tools. While this streamlined framework facilitated analysis, cross-study comparability was difficult.

Quinci (2024) presented a detailed one-level categorization of 24 resource types, which included bilingual general dictionaries, institutional websites, and more. This specificity provided insights but hindered comparisons across studies with differing participant profiles or stimuli. Similarly, Wang et al. (2017) focused on 11 resource types (dictionaries, Google search, Google Translate, Wikipedia, and the concordance tool Linguee), with a notable emphasis on dictionaries, and revealed usage differences between junior (N = 7) and senior (N = 6) translators. The study’s small, heterogeneous sample, however, also constrained its broader applicability.

Two-level categorizations

Two-level frameworks comprise hierarchical organization, and group resources into primary categories with further subcategories based on function or characteristics. This structure enables a more nuanced analyses of resource use patterns. For example, Wang (2014) categorized resources into dictionaries, web-based tools, and corpora, further subdividing each category. The findings revealed differences in resource preferences based on expertise levels, with professional translators found to favour search engines, semi-professionals showing a more balanced resource use, and novices tending to rely more heavily on dictionaries.

Gough’s (2016) Resource Type User Typology (RTUT) added a layer of complexity by introducing user profiles like “Dictionary Enthusiast” and “Parallel Text Fan,” along with variables such as research direction and strategy. Chang (2018) also applied a two-level framework to analyse trainee translators’ resource use across seven categories, which included travel websites, online images and online maps, and revealed the tailored use of resources for specific genres.

Studies like Shih’s (2017) investigation into the web search behaviours of refined resource categories by Chinese trainee translators, yielded pedagogical insights into effective resource utilization. A key pedagogical insight from this research is the finding that trainees who effectively utilize a diverse range of resources demonstrated greater proficiency in solving translation challenges.

Similarly, Onishi and Yamada (2020) compared the resource use of students and professionals and uncovered significant differences in their reliance on dictionaries and non-dictionary resources, as summarized in Table 1. The study revealed that while students and professionals allocated similar amounts of time to search engines, their use of dictionaries and non-dictionary resources differed significantly.

Evolution of web-based resource use

The progression of translation technologies has significantly influenced resource use patterns. Early reliance on traditional tools like bilingual dictionaries (Varantola and Atkins 1998) has given way to the integration of web-based resources such as search engines, encyclopaedias, and databases. Earlier studies by Enríquez Raído (2011) and Zheng (2014) illustrate how translator trainees increasingly turn to these tools for their versatility and accessibility.

This early reliance on dictionaries has been consistently observed in studies by Enríquez Raído (2011), Zheng (2014), and Sycz-Opoń (2019), and highlights their perception as a straightforward and accessible tool. As Pastor and Alcina (2010) and Lew (2013) have pointed out, however, effective dictionary use involves significant complexities, such as selecting appropriate terms from often contextless entries, and dictionaries also frequently lack the extended textual information that translators require, which prompts them to seek supplementary resources beyond traditional dictionaries (Varantola and Atkins 1998). As predicted by Varantola and Atkins (1998), the central role of dictionaries has gradually diminished with the rise of alternative resources. Surveys from 2005 and 2012 reported by Hirci (2013) underscore this shift and revealed a growing preference among translation students for tools like Google image search and blogs over traditional dictionaries such as the Oxford Pictorial Dictionary.

As evidenced, the limitations of dictionaries have driven translators to explore supplementary resources, such as search engines, blogs, and visual aids. Search engines, with their vast document collections and broad accessibility, have introduced both opportunities and challenges, particularly in navigating and filtering unreliable or misleading content. This shift has been accompanied by the increasing importance of knowledge-based resources, including encyclopaedias, wikis, and databases, which provide essential contextual information and background knowledge for translation tasks.

More recently, the advent of AI-driven tools, including neural machine translation systems and generative large language models (LLMs), has expanded the resource landscape, and while tools like ChatGPT offer new opportunities for automation and innovation, they also introduce challenges related to reliability, domain-specificity, and ethical concerns. Importantly, the traditional web search remains a vital complement to these technologies, and provides translators with granular, context-dependent information that fosters critical thinking skills essential for high-quality translation.

Despite advancements in categorization frameworks and an expanding range of tools, gaps remain in understanding how resource use evolves over time, particularly among trainee translators. Existing studies often lack evolution perspectives or fail to connect resource use patterns with translation quality outcomes. The aim of this study is therefore to address these gaps and contribute to the development of targeted training strategies by examining these dynamics in the context of an English-to-Chinese translation course,

Methodology

Th e focus of this study is on an analysis of changes in how trainee translators use of web-based resources as a function of time and skill development, across four translation tasks spread throughout a semester of a translation studies course. The study took place within a first-year master’s course in Chinese-English translation at a mainland Chinese university, which was part of a postgraduate program in Chinese translation. All participants had access to Google and Wikipedia. The course spanned 16 weeks, from September to December, and entailed 32 contact hours, broken down into two hours per week.

The aim of the course was to improve the skills of trainee translators in non-literary translation, with a strong emphasis on research capabilities and critical thinking. The curriculum was dedicated to translation-oriented web search, and encompassed topics like online search strategies, the evaluation of online resources, and the analysis of students’ web search pathways. The instructional content included teaching on topics such as effective web searching, assessing online resources, reviewing students’ search behaviours, and included lecturer demonstrations of optimal search processes and outcomes.

It is important to clarify that the course only provided the backdrop for this study, which did not aim to assess the efficacy of the course, and the authors were not involved in the teaching or support activities of the course. The focus of the study was on the identification of changes in web-based resource utilization by trainee translators, independent of how the instruction and content of the course might have influenced the types and usage of these resources.

Research design

A repeated measures design with a single cohort of 19 participants was employed, which encompassed four data collection points (cf., Enríquez Raído and Cai 2023). Participants enroled in the course were recruited on a voluntary basis. Invitation emails were sent, accompanied by a Participant Information Sheet and a Consent Form. Trainee translators interested in participating in the research were requested to reply via email to request additional information.

Following the completion of a background questionnaire (see Section “Background questionnaire”), eligible participants engaged in four translation tasks evenly distributed throughout the semester, to examine changes in their resource use over time. Each session followed a standardized format, comprising a single translation task followed by a retrospective verbal report. Data collection included a web-based screen recorder (ScreenPal) and a key-logger (Inputlog), Before the data collection sessions, the trainee translators were directed to install and familiarize themselves with two software tools, Inputlog and ScreenPal. They were assigned to translate four English texts into Chinese, each approximately 200 words in length. The translations took place during separate sessions held at regular intervals between September 2020 and February 2021 at work environments familiar to the participants, such as a library or at home. During these sessions, screen recording and key logging were performed by the participants themselves, with both software tools running unobtrusively in the background on their computers. No time constraints were placed on the tasks, and participants were provided with full internet access to enable them to freely employ any online or local resources and translation aids, including computer-aided translation (CAT) tools, machine translation, and terminology management tools. Interestingly, the participants used CAT tools, possibly due to the non-technical nature of the texts and their brief length.

After each translation task, the participants were required to verbalize and record the search processes they had employed as per the guidelines provided. Subsequently, they uploaded their screen recordings to the ScreenPal website and sent the Inputlog data file (IDFX-file) and the completed translation (Word file) via email to the specified contact.

Data collection

The data collection phase of this study involved the use of multiple tools to capture diverse types of data. This methodology adheres to the established practices in Translation Process Research (TPR), as supported by Alves (2015) and Halverson (2017). The employed data collection tools, previously piloted by Cai (2023), encompassed the background questionnaire mentioned earlier, source texts for translation, screen recorder, key-logger, and retrospective verbal reports.

Background questionnaire

The aim of the questionnaire was to collect data on the participants’ English proficiency levels, determined through recognized tests such as the Test for English Majors (TEM) Band 8, International English Language Testing System (IELTS), and Test of English as a Foreign Language (TOEFL), or similar examinations. It was also used to assess their translation experience based on the China Accreditation Test for Translators and Interpreters (CATTI) certification and prior translation work.

Source texts

To ensure that the findings could be attributed to changes in resource use rather than differences in the source texts, four comparable texts of similar complexity levels were selected. The complexity of the texts was assessed using Jensen (2009)’s framework, which comprises three indicators of text complexity: readability indices, word frequency, and non-literalness. In turn, the readability index comprises a further six indices: Flesch-Kincaid, Coleman-Liau, Gunning Fog, SMOG, and Flesch Reading Ease. These indices rely on syllable, word, and sentence counts, and employ different formulas for calculation (see Table 2).

To quantify word frequency, two frequency bands from the BNC and COCA corpora were considered. The K1 band comprised the 1000 most frequently used words, an represents the most common words. The K2-K25 band included the 1001–25,000 most common words, denoting less frequently used words. The four texts exhibited a similar distribution of word frequency within these two bands.

The third indicator, non-literalness, was focused on the presence of non-literal expressions in the texts. The total number of non-literal expressions identified were three, two, three, and two, respectively, for the four texts.

To further ensure comparability, the four texts shared the same genre, function, and purpose of translation. Specifically, they were selected from the book review column of the journal Nature, and the task description provided to the participants emphasized translating the texts “for publication purposes” across all four tasks.

Finally, to gauge text difficulty and suitability, two translation trainees with backgrounds similar to the potential participants in the main study translated the four source texts. They rated the difficulty of each text on a scale of one (very easy) to five (very difficult) and identified potential translation problems or “rich points” (Nord 1994). The mean difficulty rating for the four texts was four (SD = 0), which indicates a similar level of difficulty across all texts.

Key-logger and screen recorder

Key-loggers and screen recorders are valuable tools in Writing Process Research (WPR) and Translation Process Research (TPR) for recording writing processes (Saldanha and O’Brien 2014; Van Waes et al. 2012; Wildemuth 2016), and are commonly used alongside other tools such as eye-trackers or screen recorders, either as the primary tool or as a complementary tool.

In this study, Inputlog was selected as the primary data collection tool. This enabled the capture of all interactions between participants and the online resources they consulted. It is unintrusive and behaves in a familiar manner, which does not compromise the ecological validity of the data. Inputlog also records essential information such as the web browser used (e.g., Google Chrome), active URLs (e.g., http://www.google.be), page titles, search queries, and accessed web pages. Another advantage of Inputlog is that participants were already familiar with its word processor (i.e., Word editing window) prior to their participation. This familiarity gave Inputlog an advantage over other logging tools like Translog, which have their own interface with separate source and target language windows. Inputlog can also be used remotely by participants in their usual workplace.

Screen recording has become a standard tool in translation process research due to its comprehensive and non-invasive nature (Angelone and Marín García 2019). It is commonly used for recording all on-screen activities in the translation process and translation-oriented web search research (Enríquez Raído 2011, 2013; Gough 2016; Shih 2017; Chang 2018). Like any research tool, however, screen recorders also have limitations. The fact that they do not provide time-based information, and the transcription of the screen recording is, as noted by Enríquez Raído (2011), the “most arduous, labour-intensive, and time-consuming” phase when analysing the data (p.220). In this study, therefore, a screen recorder was used as a supplementary, rather than a primary, to facilitate direct access through a web browser. It also enabled participants to upload recordings to the platform instead of having to send large video files via email, thus streamlining the data collection process.

Since this study was conducted remotely, i.e., without the physical presence of a researcher, participants were instructed to install and use Inputlog and ScreenPal prior to performing the four translation tasks. To compensate for the absence of a researcher, detailed instructions were provided via email, along with a step-by-step video tutorial. The tutorial comprised an overview of the entire procedure and a demonstration of the two software tools.

Retrospective verbal reports

While key-loggers and screen recorders provide valuable insights into the translation process, they cannot directly capture the thoughts and intentions of the participants. To complement the data collected through these tools, retrospective verbal reports were employed to gain a deeper understanding of the changes in the resource use of the participants.

Retrospective verbal reports also served as a supplementary tool and allowed participants to reflect on their translation process and to provide insights into their decision-making and resource utilization. Verbal reports also helped in interpreting the results, although the focus of this study was not on the mental processes of the participants. For each task, participants followed a structured process to document their information-seeking activities. Specifically, they were instructed to highlight the items in the source text that required information-seeking, after which they categorized each search based on its type, such as expression clarification or background information retrieval. Finally, participants rated the difficulty of each search on a scale from 1 (very simple) to 5 (very challenging) and provided brief explanations for their ratings. This systematic approach provided a detailed record of the information-seeking process, which offered insights into participants’ search behaviours and the challenges they encountered.

The collected data were analysed both quantitatively and qualitatively. The key-logger and screen recorder provided quantitative data on resource use and participant-related behaviours, while the retrospective verbal reports yielded qualitative insights into the decision-making processes and reasoning behind resource selection. Due to space restrictions and the limited detail provided by the verbal reports compared to initial expectations, the analysis in this article is primarily based on the quantitative results.

Translation quality assessment

The quality of the translations was evaluated using the Multidimensional Quality Metrics (MQM) frameworkFootnote 1 by three experienced raters (details below). The MQM framework was selected for its comprehensive approach, which considers multiple dimensions of translation quality, including accuracy, fluency, terminology, style, design, locale convention, and verity. These dimensions are commonly used in the translation industry for assessing both linguistic and functional aspects of quality. The raters identified and categorized errors across these dimensions, and assigned severity levels classified as critical, major, minor, neutral, and kudos. Each error type was scored using an MQM scorecard, with critical errors were assigned 25 points, major errors 5 points, and minor errors 1 point. To streamline the process, an Excel sheet with drop-down menus allowed raters to easily select error types and severity levels, with scores automatically calculated to ensure consistency and accuracy.

The initial raters were lecturers at a Chinese university, each holding a PhD in Translation Studies and extensive experience in translation quality assessment. To enhance the reliability of these evaluations, a third rater, also a PhD holder in Translation Studies and a lecturer at a Chinese university, independently reviewed the initial assessments. The review by the third increased the validity of the findings and ensured a higher degree of reliability.

The aggregated scores from this rigorous review process were then used for further analysis, as detailed in the following section.

Data analysis and discussion

In this section the changes in resource utilization over the four tasks, for the 19 participants who completed all four translation tasks are examined. The data comprised a total of 76 observations (4 tasks × 19 participants). A “bottom-up” approach was followed where the resources employed were initially identified and subsequently categorized into three main groups, namely dictionaries, search engines, and knowledge-based resources. The findings derived from the preliminary analysis of these overarching categories are presented in Section “Preliminary analysis”. A more detailed analysis is then provided in Section “Granular analysis”, which provides a finer level of granularity, whereby each primary resource category is further subdivided into 22 distinct dictionaries, six different search engines, and five types of knowledge-based resources (as detailed in Sections “Dictionaries”, “Search engines”, and “Knowledge-based resources”, respectively).

Participants’ background information

As mentioned at the beginning of the Methodology section, the participants were recruited from a master’s course in Chinese-English translation at a mainland Chinese university. To gain admission to this program, participants were required to pass a post-graduate entrance exam that included two tests: an English Proficiency Test and an English-Chinese Translation Test. The fact that they had successfully passed these tests indicates that their English and translation proficiency levels were comparable.

Based on the responses to the questionnaire, acceptable English proficiency was set at the grade of TEM 8, IELTS 7, and TOEFL. The TEM 8 is typically considered the most suitable measure of English proficiency in China, usually taken in the fourth year of an English bachelor’s degree. Due to the cancellation of the TEM 8 in 2020 because of Covid-19, however, most participants were unable to take this exam. Only three participants, who had taken the TEM 8 in 2019 and failed the post-graduate entrance exam in their fourth year, provided their TEM 8 results after retaking the entrance exam post-graduation. Six participants took IELTS, with their overall band scores ranging from 7 to 8. Candidates with scores of 7 and 8 are classified on the IELTS website as a “good user” and “very good user” of English respectively.Footnote 2 TOEFL is another test used to measure English proficiency, however none of the participants in this dataset had taken this qualification.

In summary, the participants possessed a comparable level of English proficiency, as evidenced by their TEM 8 and IELTS scores, an intermediate-to-high degree of translation proficiency (as measured by CATTI Levels II and III), and had little or no formal translation work experience, as summarized in Table 3.

Preliminary analysis

To measure shifts in resource use three key metrics were used which included the total time spent on each resource category, the unique resources used, and the percentage of time allocated to each resource type, which were dictionaries, search engines, and knowledge-based resources (Fig. 1). The data revealed that search engines were the most frequently used resource, accounting for 48.1% of the total resource time. On average, participants spent approximately 7 min and 58 s accessing search engines per task. Knowledge-based resources ranked second in terms of usage, constituting 28.8% of the total resource time, with an average time of 5 min and 42 s. Dictionaries were the least utilized resource, comprising only 23.1% of the combined resource types. On average, participants spent approximately 3 min and 22 s per task accessing any type of dictionary.

The figure illustrates the percentage resource usage during the four tasks. It further shows a slight increasing trend in the use of search engines, that rose from 47.05% in Task 1 to 51.11% in Task 4. Conversely, dictionary usage showed a decreasing trend, declining from 30.21% in Task 1 to 21.26% in Task 4. The overall trend for knowledge-based resources was also positive, with usage increasing from 22.63% in Task 1 to 27.58% in Task 4.

From the analysis of the dynamics among the three main types of resources, it is noteworthy that in Task 1, the percentage of dictionary usage exceeded the percentage of knowledge-based resource usage. After Task 2, however, the percentage of dictionary usage consistently fell below the percentage of knowledge-based resource use, and although this disparity lessened in Task 4, the percentage of knowledge-based resource access still exceeded that of dictionary usage.

Regression analysis was subsequently conducted using linear mixed-effects models to examine the observed changes in resource usage. Over the course of the study Three models were constructed to assess whether the observed decreases or increases in resource use were significant and represented true differences in the hypothetical population. The null hypotheses tested various relationships between the translation tasks and the response variables, namely the percentage of time spent on dictionaries, search engines, and knowledge-based resources, respectively. The explanatory variable for all models was the Task ID (T_ID), and the random-effect variable was the Participant ID (P_ID).

Model 1: Regression model for the percentage of time spent on dictionaries

lmerTest::lmer(dictionary_pct ~ T_ID + (1|P_ID), data = websearch)

Model 2: Regression model for the percentage of time spent on search engines

lmerTest::lmer(searchengine_pct ~ T_ID + (1|P_ID), data = websearch)

Model 3: Regression model for the percentage of time spent on knowledge-based resources

lmerTest::lmer(knowledge_pct ~ T_ID + (1|P_ID), data = websearch)

Table 4 summarizes the results of these regression models.

The results of Model 1 confirm a significant decrease in the percentage of time spent on dictionary consultation in Task 2, Task 3, and Task 4 (p = 0.031, p < 0.001, p = 0.011). These observations align with previous studies conducted by Chang (2018) and Paradowska (2020) in similar longitudinal and intervention settings, respectively. Chang (2018) revealed a progressive decline in dictionary usage over three tasks, while Paradowska (2020) demonstrated a statistically significant decrease after a four-month intervention. Similar trends have also been observed in previous literature, where higher levels of expertise were associated with reduced reliance on dictionaries, as demonstrated by Wang (2014) and Onishi and Yamada (2020), who compared students and professionals.

While there is a noticeable trend towards reduced reliance on dictionaries, further investigation is needed to assess the actual effectiveness of dictionaries in translation and the implications of their diminished use. Livbjerg and Mees (2003) empirically demonstrated the limited impact of dictionaries on translation quality, which underscores the need for a more nuanced assessment of dictionary effectiveness. Research findings, including from studies by Enríquez Raído (2011), Wang (2014), and Sycz-Opoń (2019), have however consistently indicated a tendency among students to over-rely on dictionaries.

In the present study, to attribute improved resource utilization solely to decreased dictionary use would be premature, nonetheless, it is reasonable to infer that as trainee translators advanced in their course, they possibly developed greater confidence in their language and translation skills. This advancement may have led them to recognize the limitations of dictionaries, which resulted in a reduction in their usage, thus there is a direct link between these observations and instructional influence would therefore require evidence beyond the scope of this research.

Unlike Model 1, Model 2 yielded non-significant results (p = 0.465, p = 0.476, p = 0.286), indicating that participants allocated a comparable proportion of their time to using search engines. In contrast to the consistent findings regarding dictionary usage reported in previous literature, the results related to search engine usage revealed a slightly more diverse pattern. For instance, in the longitudinal study, by Paradowska (2020), although descriptive findings suggested an increase in the percentage of time spent on search engines, inferential analysis did not detect significant changes. Similarly, in the study conducted by Onishi and Yamada (2020), both students and professionals dedicated a similar percentage of their time to search engine usage (32.13% for students and 32.18% for professionals) when translating a 62-word text. A slight increase in the frequency of search engine use was however observed in Chang (2018) a longitudinal study, which encompassed a one-year postgraduate translation course in the UK. Notably, inferential analyses were not conducted by Chang due to the limited number of participants.

With respect to the percentage of time allocated to knowledge-based resources during the four translation tasks, Model 3 shows that, compared to Task 1, the subsequent three tasks exhibited an upward trend, with statistical significance observed for the increases in Task 2 and Task 3 (p = 0.012, p = 0.023). If these findings are compared with those of Onishi and Yamada (2020), students in their study allocated 36.9% of their time to non-dictionary resources, while professionals allocated 56.43%. Despite existing terminological variations exist, the scope of non-dictionary resources in Onishi and Yamada (2020) aligns with the present study, representing resources other than search engines and dictionaries.

The increasing use of knowledge-based resources suggests that participants attached greater importance to information obtained from these sources, such as background information, rather than solely relying on superficial lexical information. This shift highlights importance of exposing trainees to a broad range of knowledge-based resources early in their training. It also emphasizes the strategies employed by trainee translators and underscores the significance of accessing comprehensive, contextually relevant information to support the translation process effectively.

Granular analysis

Dictionaries

The changes in dictionary use across the four translation tasks were further investigated by categorizing dictionaries into 22 different types, as shown in Table 5. The grouping is based on the number of tasks in which the dictionaries were used (i.e., in all four tasks, in three tasks, in two tasks, or in only one task), and was aimed at providing a representative indication of the changes in dictionary usage over the four tasks.

The first group consisted of eight dictionaries that were used in all four tasks, including Oulu, Youdao, Merriam-Webster, Jinshan, Baidu MT used as a dictionary,Footnote 3 Bing, and Cambridge. Among these, the most frequently used dictionary, Oulu, experienced a significant decrease in time spent from Task 1 to Task 4. Lingoes, the only dictionary showing an increasing trend, stood out due to its integration of various online dictionaries and encyclopaedias, that offered participants a convenient platform to access a broader range of resources. The evolution of dictionaries renders traditional categorizations such as bilingual or monolingual increasingly inapplicable, as most dictionaries now integrate features from both types.

The second group included Google MT, which was also used as a dictionary in three tasks. The third group comprised Youdao MT, DeepL, and Sogou MT, which were used as dictionaries in two of the tasks. The remaining ten dictionaries were only used in one of the four tasks, with a clear downward trend observed upon closer inspection.

Notably, the time spent using machine translation engines as dictionaries decreased across the four tasks. This decline was evident in Baidu MT, Google MT, Youdao MT, DeepL, and Sogou MT. The use of machine translation engines for instant dictionary lookups might seem less ideal or unprofessional, however its use has been observed in other studies, such as Gough (2016), Shih (2019), and Quinci (2024), possibly due to its easy accessibility, speed, or convenience. The decrease in the use of machine translation engines as dictionaries suggests either a decrease in the overall number of participants’ lexical information needs or a change in these lexical needs, with participants now requiring more comprehensive and deeper lexical information, such as background context. As one participant highlighted in the retrospective verbal report for Task 3, translating the term “evo-devo perspective” was problematic for machine translation engines, possibly due to the abbreviation “evo-devo” (which is short for evolution and development). As a result, the participant needed to consult additional resources, such as search engines, to find an appropriate translation.

Overall, the use of dictionaries diminished sequentially over the four tasks, identifying the evolving search strategies employed by participants and the need for comprehensive investigation into the impact of different dictionary types on translation outcomes.

Search engines

The breakdown of time spent on search engines per task was analysed, and different patterns of search engine use identified. Comparisons were made among six search engines used consistently across the four tasks by the 19 participants. Table 6 presents the mean duration for each search engine usage in each task.

It is important to note that when search engines displayed dictionary entries directly, without the participant having to visit the dictionary’s website, these instances were categorized as “search engines” and not “dictionaries.” This decision is based on two factors: 1) The URL, remained that of the search engine even when displaying dictionary entries; 2) As explained, mainly for reasons of ecological validity, eye-tracking analysis was not used in this study. Consequently, determining whether participants viewed or read the dictionary entries would be speculative.

The results showed that Google Search remained stable throughout the four tasks, ranging from 1 h 15 min to 1 h 44 min. Baidu Search displayed a downward trend with some fluctuations, starting at 45 min 59 s in Task 1 and decreasing to 22 min 36 s in Task 4. Bing Search initially had a duration of 29 min 18 s in Task 1, followed by a significant decrease of 18 min 8 s in Task 2, however, it rebounded slightly in Task 4, reaching 17 min 12 s after an increase of 13 min 38 s.

The New Tab search engine, which served as the start page for web browsers and indicated the participants’ initial search, remained stable across the four tasks, ranging from 5 min 36 s to 9 min 55 s. 360 Search and Sogou Search (developed by Chinese companies) were however only used sporadically compared to the other search engines, reflecting their limited usage by participants.

These findings indicate the participants’ search engine preferences and usage patterns across different tasks. Google and Baidu emerged as the two most consistently used search engines in this study, which aligns with previous findings (Shih 2017) that also explored English and Chinese language combinations. Notably, the time spent on Google Search remained relatively stable across the four tasks, whereas Baidu Search and Bing Search experienced a decrease. This trend supports the findings of Wang (2014), namely, that professional translators with the same language pair tend to rely more on Google Search, Baidu Search, or Bing Search than other search engines. One participant’s retrospective report noted their preference for Google over Bing citing Google’s richer content and its ability to provide information that is often unavailable in Chinese search engines like Baidu.

These findings further illustrate the impact of different search engines on search results, an often-overlooked aspect in translation studies. This may stem from the dominance of a single search engine in certain languages, such as Google’s 97.85% usage in Polish (Paradowska 2020). In China, however, Baidu represented the majority of usages with 84.27% in 2020, followed by Bing (6.73%), Sogou (3.05%), and Google (2.51%), while others like Haosou and Shenma collectively accounted for only 3.44%. The lower utilization of Google can be attributed to its limited accessibility in China, where a VPN is required. In the present study, all participants had access to Google Search, resulting in this engine being the most frequently used search engine at 61.8%, while Baidu accounted for 20.9%. These findings underscore the unique nature of translation-oriented resource use on the web and emphasize the importance of contextualizing web search studies within the field of translation studies.

Knowledge-based resources

Five distinct categories of knowledge-based resources were identified across the four tasks: academic documents, concordancers and corpora, encyclopaedias, discussion forums, and other web pages. Academic documents encompassed resources such as Google Scholar, Baidu Scholar, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), academic web pages (e.g., library pages), and parallel texts (e.g., formal reports) in PDF file format. Concordancers and corpora included Linguee, British National Corpus (BNC), Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA), and English-Corpora (a collection of online corpora).Footnote 4 Encyclopaedias consisted of Wikipedia, Baidu Baike, and Sogou Baike. Discussion forums encompassed Questia, Zhihu, Douban, Baidu Zhidao, and Sci-Hub. The category “other web pages” comprised all remaining web pages not included in the above types of knowledge-based resources. For instance, the most frequently accessed “other web page” was the Amazon webpage, which provided information about books for which book reviews were assigned for translation.

Table 7 offers detailed data on the time spent on specific resources per knowledge-based resource category, broken down by task. Table 8 then presents an overview of the usage patterns of the five types of knowledge-based resources across all four tasks.

In Table 8, in Task 1, participants consulted academic documents on average for 4 min and 36 s, with a steady increase in consultation time observed in Task 2, Task 3, and Task 4, peaking at 21 min and 59 s in Task 3. The average time spent on concordancers and corpora was 5 min and 7 s in Task 1, which increased to 20 min and 43 s in Task 2 and 17 min and 42 s in Task 3. In Task 4, the time spent on concordancers and corpora decreased to 6 min and 4 s, but still showed an increase of 57 s compared to Task 1. Meanwhile, the time allocated to encyclopaedias increased from 4 min and 57 s in Task 1 to 12 min and 6 s in Task 4, with the longest duration observed in Task 3 (15 min and 9 s). Participants spent 4 min and 42 s on average accessing discussion forums in Task 1, which reached a maximum of 11 min and 53 s in Task 2. The time spent on discussion forums slightly decreased in Task 3 and Task 4, amounting to 8 min and 22 s and 8 min and 26 s, respectively.

Across the resources of academic documents, concordancers and corpora, encyclopaedias, and discussion forums, a positive trend was observed, peaking at Task 2 or Task 3, and declining in Task 4. In Task 4, the average time spent on each type of knowledge-based resource was longer compared to Task 1. In contrast, the use of “other web pages” showed a negative trend. As mentioned, “other web pages” predominantly encompassed general content with a simple design compared to other knowledge-based resources. It is possible that participants relied less on “simple and general” sources and gravitated towards more specialized or authoritative resources to obtain in-depth information.

Translation quality assessment

The Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.53 (p < 0.05) between the two raters indicates a statistically significant moderate agreement (Akbari and Segers 2017). The analysis found a weak negative correlation (rs = −0.028, p < 0.05) between the quality assessments and the time spent using knowledge-based resources, implying that more time spent on these resources tends to correlate with lower error scores in translations. The correlation between translation quality and the time spent on dictionaries and search engines was, however, not statistically significant, with p-values of 0.20 and 0.45, respectively.

These results hint at a potential link between the use of resources and the quality of translation outputs, and particularly highlight the role of knowledge-based resources. This finding emphasizes the need for further investigation into how different resources affect translation quality and supports the call for ongoing research in resource utilization within Translation Studies.

Overall, the findings are consistent with previous research in the field of translation-oriented information-seeking on the web. Enríquez Raído (2011, 2013) was amongst the first to conduct a web search study, where students predominantly relied on dictionaries for information searching in Task 1, while in Task 2, the use of diverse information sources increased, influenced by factors such as text difficulty and web search strategies. Similarly, Chang (2018) observed a gradual shift from dictionary-based resources to other resources across four tasks of similar difficulty levels conducted over one year. Paradowska (2020) also confirmed a significant decrease in reliance on dictionaries, a non-significant increase in search engine usage, and an increase in the use of other resources, although no inferential analysis was conducted to support these observations. Additionally, Onishi and Yamada (2020) examined resource usage differences between students and professionals and found that the divergence primarily existed in the percentage of dictionary and non-dictionary resource usage, with students relying more on dictionaries and professionals relying more on non-dictionary resources.

Two potential reasons may explain the outcomes of this study. First, trainee translators possibly recognized the importance of non-lexical, domain-specific information, which dictionaries often lack. Given that the source texts in this study were scientific book reviews, participants needed to seek out alternative sources, like knowledge-based resources, to access the necessary data. These resources tend to offer a wider array of information than dictionaries, presenting opportunities for more comprehensive research. It should be noted that the appropriateness of a resource is, however, context dependent. As pointed out, there is no universally “correct way of obtaining certain types of information,” but effective translation search tasks usually require a broader and more varied approach to resource utilization, as supported by research by Enríquez Raído (2013), Wang (2014), Shih (2019), Gough (2016), and Chang (2018). Secondly, focused training on web-based information seeking could have improved the trainee translators’ skills in evaluating the reliability of different sources and enabled them to find more appropriate solutions. A more detailed investigation into why participants chose specific resources could not only validate these explanations but also offer valuable insights for future studies on resource use in Translation Studies. Lastly, it is important to acknowledge that other factors, such as participants’ inherent translation skill development may also have influenced this. Future research should consider these, and other, factors to provide a comprehensive understanding of the dynamics at play.

Conclusion and insights for future training and research

The aim of this study was to examine the change in the web-based resource usage of trainee translators over a four-month translation practice course involving English and Chinese. The findings found a significant shift from reliance on dictionaries to a broader and more diverse use of knowledge-based resources, which reflects a transition from addressing lexical problems to tackling contextual and domain-specific challenges. The Trainees also increasingly accessed specialized resources like academic documents and encyclopaedias and dedicated more time to exploring background or domain-specific information rather than simply seeking word equivalents. These insights offer valuable guidance for translation trainers to refine instructional strategies and enhance resource competence among trainee translators.

The study findings underscore the importance of integrating advanced information literacy training tailored to the unique needs of translators. Generic university-level information literacy courses, often led by librarians, do not address the specific requirements of translation practice. By incorporating instruction on advanced search techniques, query optimization, and resource identification early in translator education programs, educators can equip trainees with the skills needed to navigate and critically evaluate the evolving landscape of online resources. This foundation is essential for fostering efficient and effective translation problem-solving skills.

From a methodological perspective, the use of key-logging tool proved instrumental in reducing researcher workload and enabling the analysis of larger participant cohorts. This approach could serve as a model for future research exploring the relationship between training activities and the development of resource utilization patterns. The study’s limited sample size, however, highlights the need for larger-scale studies to enhance the robustness and generalizability of findings. Small-scale studies, while offering valuable initial insights, should be complemented by broader investigations to confirm trends and identify variations across diverse contexts.

Future research should address key gaps, including larger longitudinal studies to assess whether changes in resource usage are sustained over time, cross-cultural ad cross-lingual comparisons of resource preferences, and field-specific analyses (e.g., legal, medical, technical translation). Experimental designs with control and experimental groups could also help isolate the impact of tailored training interventions and provide deeper insights into the effectiveness of specialized resource instruction. In addition, the exploration of the relationship between resource usage and translation efficiency could offer a more comprehensive understanding of how web-based tools influence translation quality and speed.

These findings remain relevant, although this study predates the widespread adoption of AI technologies and LLMs. The dynamic nature of web-based resource usage emphasizes the enduring principles of information-seeking behaviour, such as the need for critical evaluation and contextual understanding, however, the emergence of AI and LLMs has introduced new opportunities and challenges for translators, which underpins the importance of updating translator education to include AI literacy. Future studies should therefore examine how AI tools interact with traditional web-based resources and explore the integration of AI-driven technologies into training programs.

In conclusion, these findings provide a valuable foundation for understanding the evolving resource usage patterns of trainee translators and offers actionable insights for improving translator education. Educators can therefore prepare future professionals to effectively utilize both traditional and AI-enhanced resources by tailoring training to the specific needs of translators and embracing the changing technological landscape. This research therefore sets the stage for further investigation into the intersection of web-based resources, translation technologies, and translator training, to ensure that education programs remain responsive to the demands of an ever-evolving field.

Data availability

The data set is accessible through the Humanities and Social Sciences Communications Dataverse repository via: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/TENRW8.

Notes

If participants entered only phrases into the machine translation engine, it was regarded as using the engine as a dictionary. However, if participants entered an entire text into a machine translation engine, it was not regarded as a resource but rather as a translation mode.

References

Akbari A, Segers W (2017) Translation evaluation methods and the end-product: which one paves the way for a more reliable and objective assessment? SKASE J Transl Interpretation 11(1):2–24

Alves F (2015) Translation process research at the interface. In Psycholinguistic and Cognitive Inquiries into Translation and Interpreting, pp. 17–40

Angelone E (2019) Process-oriented assessment of problems and errors in translation: Expanding horizons through screen recording. In Quality assurance and assessment practices in translation and interpreting, IGI Global, Hershey PA, USA, pp. 179–198

Cai Y (2023) Online Resource Use and Query Behaviour of English-to-Chinese Trainee Translators: A Statistical Analysis. PhD thesis. University of Auckland

Chan SW (2023) Routledge encyclopedia of translation technology. Taylor & Francis Group

Chang L (2018) A Longitudinal Study on the Formation of Chinese Students’ Translation Competence: with a particular focus on metacognitive reflection and web searching. PhD thesis. University College London

Corpas Pastor G, Durán-Muñoz I (eds) (2018) Trends in e-tools and resources for translators and interpreters. Brill, Leiden and Boston

Daems J, Carl M, Vandepitte S, Hartsuiker R, Macken L (2016) The Effectiveness of Consulting External Resources During Translation and Post-editing of General Text Types. In New Directions in Empirical Translation Process Research, pp. 111–133. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-20358-4_6

Enríquez Raído V (2011) Investigating the web search behaviours of translation students. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Universitat Ramon Llull, https://www.tdx.cat/bitstream/handle/10803/21793/Enriquez_PhD_Thesis_Final.pdf

Enríquez Raído V (2013) Translation and Web Searching. Routledge

Enríquez Raído V, Cai Y (2023) Changes in Web Search Query Behaviour of English-to-Chinese Translation Trainees. Ampersand, 11, 100137

EMT (2022) EMT Competence Framework 2022. Retrieved 15 January from https://commission.europa.eu/system/files/2022-11/emt_competence_fwk_2022_en.pdf

Gough J (2016) The patterns of interaction between professional translators and online resources. PhD thesis. University of Surrey

Göpferich S (2009) Towards a model of translation competence and its acquisition: the longitudinal study TransComp. In Göpferich S, Arnt, LJ, Mees, I M (eds), Behind the mind: Methods, models and results in translation process research. Samfundslitteratur, pp. 11–37

Halverson SL (2017) Multimethod approaches. In Schwieter, JW, Ferreira A (eds) The handbook of translation and cognition. Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 195–212

Hendy A, Abdelrehim M, Sharaf A, Raunak V, Gabr M, Matsushita H, Kim YJ, Afify M, Awadalla HH (2023) How Good Are GPT Models at Machine Translation? A Comprehensive Evaluation. arXiv, https://arxiv.org/abs/2302.09210

Hirci N (2013) Changing Trends in the Use of Translation Resources: The Case of Trainee Translators in Slovenia. ELOPE: Engl Lang Overseas Perspect Enquiries 10(2):149–165

Hvelplund KT (2023) Institutional translation and the translation process Cognitive resources, digital resources, and translator training. In Svoboda T, Biel Ł, Sosoni V (eds) Institutional Translator Training

Jensen KTH (2009) Indicators of Text Complexity. Copenhagen Studies in Languages 37:61–80

Jiao W, Wang W, Huang JT, Wang X, Tu Z (2023) Is ChatGPT a good translator? A preliminary study. arXiv, https://arxiv.org/abs/2301.08745

Lew R (2013) Online dictionary skills. Proceedings of eLex

Livbjerg I, Mees IM (2003) Patterns of dictionary use in non-domain-specific translation. In: F Alves (ed) Triangulating Translation: Perspectives in process oriented research. John Benjamins Publishing Company, London and New York

Nord C (1994) Translation as a process of linguistic and cultural adaptation. In: Dollerup C, Lindegaard A (eds) Teaching Translation and Interpreting 2: Insights, aims and visions. John Benjamins Publishing Company, London and New York

O’Hagan M (ed) (2019) The Routledge handbook of translation and technology. Taylor & Francis, London and New York

Onishi N, Yamada M (2020) Why translator competence in information searching matters: An empirical investigation into differences in searching behaviour between professionals and novice translators. Invit Interpreting Transl Stud 22:1–23

PACTE (2011) Results of the validation of the PACTE translation competence model. In: C Alvstad, A Hild, & E Tiselius (eds) Methods and strategies of process research: Integrative approaches in translation studies. John Benjamins Publishing, London and New York, pp. 317–343

Paradowska U (2020) Developing information competence in translator training – a mixed-method longitudinal study. PhD thesis, University of Adam Mickiewicz

Pastor V, Alcina A (2010) Search Techniques in Electronic Dictionaries: A Classification for Translators. Int J Lexicogr 23(3):307–354. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijl/ecq015

Quinci C (2024) The impact of machine translation on the development of info-mining and thematic competences in legal translation trainees: a focus on time and external resources. Interpreter Translator Train 18(2):290–312

Rothwell A, Moorkens J, Fernández-Parra M, Drugan J, Austermuehl F (2023) Translation tools and technologies. Routledge

Saldanha G, O’Brien S (2014) Research methodologies in translation studies. Routledge

Shih CY (2017) Web search for translation: an exploratory study on six Chinese trainee translators’ behaviour. Asia Pac Transl Intercultural Stud 4(1):50–66

Shih CY (2019) A quest for web search optimisation: An evidence-based approach to trainee translators’ behaviour. Perspectives 27(6):908–923

Siu SC (2023) ChatGPT and GPT-4 for professional translators: Exploring the potential of large language models in translation. Available at SSRN https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4448091

Sycz-Opoń J (2019) Information-seeking behaviour of translation students at the University of Silesia during legal translation – an empirical investigation. Interpreter Translator Train 13(2):152–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750399x.2019.1565076

Varantola K (1998) Translators and their Use of Dictionaries: User Needs and User Habits. In Atkins BTS (ed), Using Dictionaries Studies of Dictionary Use by Language Learners and Translators. Max Niemeyer Verlag

Van Waes L, Leijten M, Wengelin Ǻ, Lindgren E (2012) Logging tools to study digital writing processes. In: Past, present, and future contributions of cognitive writing research to cognitive psychology. Psychology Press, London and New York, pp. 507–533

Wang VX, Lim L (2017) How do translators use web resources Evidence from the performance of English–Chinese translators. In Kenny D (ed) Human Issues in Translation Technology. Routledge, London and New York

Wang L, Lyu C, Ji T, Zhang Z, Yu D, Shi S, Tu Z (2023) Document-level Machine Translation with Large Language Models. arXiv, https://arxiv.org/abs/2304.02210

Wang Y (2014) An Empirical Study of Chinese Translators’ Search Behaviour in Chinese-To-English Translation. PhD thesis. Shanghai International Studies University

Whyatt B, Witczak O, Tomczak E (2021) Information behaviour in bidirectional translators: focus on online resources. The Interpreter and Translator Trainer, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750399x.2020.1856023

Wildemuth BM (ed) (2016) Applications of social research methods to questions in information and library science. Bloomsbury Publishing, USA, Santa Barbara, California

Zheng B (2014) The role of consultation sources revisited: An empirical study of English–Chinese translation. Perspectives 22(1):113–135

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank the first author’s co-supervisors, Professor Changshuan Li from Beijing Foreign Studies University for his support with data collection, and Dr. Thomas Yee from the University of Auckland for his expertise in statistical analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yuxing Cai conceived the original idea, carried out the experiment and wrote the manuscript. Vanessa Enríquez Raído contributed substantially to the revising of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study has been granted ethical approval by the University of Auckland Human Participants Ethics Committee (UAHPEC) under the approval reference number 022125.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cai, Y., Enríquez Raído, V. Development of web-based resource usage patterns among English-to-Chinese trainee translators. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 301 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04642-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04642-0

This article is cited by

-

Student translators’ web-based vs. GenAI-based information-seeking behavior in translation process: A comparative study

Education and Information Technologies (2025)