Abstract

The government continues to face multiple challenges in increasing female labor force participation (FLFP) among ethnic minorities. While culture is considered a key factor, distinguishing it from other factors like institutions remains difficult. This study uses a spatial regression discontinuity design to address this challenge and analyze the differential impact of culture on FLFP on both sides of the ethnic boundary. The results reveal that the probability of FLFP among ethnic minority women is 33.4 percentage points lower than that of Han women on both sides of the ethnic boundary. This finding remains robust across different bandwidths and model specifications, ruling out the influence of factors such as institutional differences, non-random migration, and “sorting behavior”. Mechanism analysis suggests that culture exerts its effect on both sides of the ethnic Boundary through both labor demand and supply dimensions. The impact is particularly pronounced among women aged 18–29 or over 40, those who are unmarried or married with a spouse, and those in families with two or fewer children. This study holds significant theoretical and practical implications for optimizing employment policies for women in ethnic minority regions from a cultural perspective.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Previous literature has extensively discussed various factors that may influence labor force participation, such as policies (Kluve, 2010), markets (Autor et al. 2013), and public health crises (Thomeer et al. 2023). However, even after accounting for differences in policies, markets, and other institutional factors, we must face the fact that significant differences in labor force participation still exist between countries or regions, as well as between different regions within the same country. This suggests that the explanation of labor force participation differences solely based on institutional and market factors may require further scrutiny. To address this, economists have explored the potential impact of culture on labor force participation in theoretical discussions (Lindbeck and Nyberg, 2006). However, it was not until Eugster et al. (2017) used evidence from Switzerland to analyze the cultural impact on labor force participation that empirical support for the role of cultural differences in explaining observed labor force participation disparities began to emerge.

It is important to note, however, that the situation in Switzerland differs significantly from that in China. The impact of culture on labor force participation in the Chinese context remains largely unknown, especially due to the lack of empirical analyses focusing on ethnic minority women, who face a “double disadvantage” in the labor market (Grönlund and Fairbrother, 2021). One key empirical challenge in examining the cultural impact on labor force participation is the difficulty in isolating cultural factors from institutional ones, as they are often intertwined (Bénabou and Tirole, 2005). Existing research often treats ethnic identity as a proxy for culture (Battu and Zenou, 2009; Nguyen et al. 2020), positing that different ethnic minorities exhibit distinct cultural behaviors (Nguyen et al. 2020). Based on this approach, this paper also regards ethnic minority identity as a proxy for culture. One of the main objectives of this study is to accurately identify the cultural effect on the labor force participation of ethnic minority women, particularly by disentangling cultural influences from institutional factors.

China is a multi-ethnic country officially recognizing 56 ethnic minorities. Shortly after the founding of the People’s Republic of China, the central government established the system of regional ethnic autonomy. This system was developed based on a thorough respect for the history, culture, and characteristics of ethnic minorities, as well as their collective preferences. As a result, 55 ethnic minorities were officially identified, forming the foundation of this essential political institution. These “ethnic Boundary” often coincide with geographical Boundary, and residents on both sides of these borders experience different cultural influences.

To understand how culture influences FLFP, we empirically analyze the labor force participation of women at China’s “ethnic boundaries.” We need to focus on two key aspects: On one hand, within a 11 km range of the ethnic boundary, the proportion of ethnic minority populations increases significantly, from 30% in Han-majority areas to ~50% in ethnic minority areas. On the other hand, although ethnic boundaries overlap with administrative boundaries, theoretically, this may confound the effects of culture and policy. However, the following three factors help us effectively avoid this issue. First, our sample is drawn from within Sichuan Province in China. In the context of the national system of regional ethnic autonomy, residents within the same province are generally subject to similar macro-level policies, such as compulsory education, employment, and social security. This is consistent with existing research, which suggests that preferential policies for ethnic minorities tend to vary across provinces (Huang et al. 2023; Jia and Persson, 2021). Second, even acknowledging that such differences may exist within the same province, by limiting our analysis to a specific distance on both sides of the ethnic boundary (with an optimal bandwidth of 11 km), we can eliminate the potential influence of institutional differences. Third, we conducted placebo tests on samples within the same administrative region (municipal level), further isolating the possible impact of institutional factors and thereby strengthening the external validity and robustness of our findings.

It is important to note that the potential presence of non-random migration and sorting behavior (i.e., higher-educated women are more likely to migrate out of ethnic minority areas, leaving behind women with lower educational attainment) across ethnic boundaries is another challenge that must be addressed in this study. To eliminate these potential confounders, we employed the following strategies: First, we conducted an analysis using samples with lower education levels to ensure that even if such sorting behavior exists, our conclusions remain robust; second, by using optimal bandwidth design, we further mitigated the potential bias caused by such behaviors, ensuring the stability and reliability of our results; third, in our robustness checks, we employed cross-sample predictions to examine the possible impacts of individual background imbalances, and our conclusions remain valid; fourth, by engaging with existing literature and established historical facts, we clarified the exogeneity of the ethnic boundary selection.

In conclusion, through a multidimensional empirical design, this paper successfully addresses key challenges, including the confusion between cultural and institutional effects, non-random migration, and sorting behavior, providing a solid theoretical and empirical foundation for exploring the role of cultural factors in FLFP on both sides of the ethnic boundary.

In the literature, there are two conflicting views on the relationship between ethnic minorities and labor force participation in Western contexts. The first, more common perspective argues that ethnic minorities are disadvantaged in the labor market (Li and Heath, 2018). For instance, Mok and Platt (2020) noted that different Chinese ethnic groups in the UK face varying degrees of racial penalties in the labor market. The second view, in contrast, suggests that there are no significant ethnic differences in labor force participation. Longhi (2020) found no significant ethnic differences in the probability of transitioning from paid employment to labor force participation, and in some cases, ethnic minority differences may even work to their advantage.

Moreover, the use of cross-sectional versus longitudinal data can lead to inconsistent conclusions. As Longhi (2020) pointed out, cross-sectional studies have found that at any given time, the labor force participation probability of most ethnic minority men and women is higher than that of the white British population, and these differences cannot be fully explained by individual characteristics. However, Longhi (2020) studies have found almost no ethnic differences in the probability of transitioning from paid employment to labor force participation, and ethnic minority differences often work to their advantage.

Existing studies have also explored reasons for ethnic minorities’ labor market disadvantages. Some argue that these disadvantages stem from a lack of social capital or access to job information, or differences in job-seeking strategies (Tegegne, 2015). Studies based on this view generally recommend enhancing ethnic minorities’ labor skills (Peijen and Wilthagen, 2023). Other research attributes these disadvantages to racial discrimination. For example, Heath and Di Stasio (2019) suggested that racial discrimination is a major reason for the persistently low labor force participation rates among ethnic minorities. However, these studies primarily focus on ethnic groups differentiated by external characteristics such as skin color. Culture is a key determinant of differences between ethnic groups. Koopmans (2015) argued that labor market disadvantages are due to social and cultural differences, which could be mitigated through cultural assimilation or integration. Beckhusen et al. (2013) also noted a strong correlation between immigrants’ geographic concentration (or residential segregation) and labor market outcomes and cultural integration. Constant and Zimmermann (2008) studied the ethnic self-identity of immigrants in Germany and their identification with mainstream German culture, finding that different types of cultural identity affect labor market outcomes. These findings suggest that analyzing labor force participation from a cultural perspective may provide more practical explanations.

In summary, this paper seeks to explore several questions related to the cultural impact on ethnic minority women’s labor force participation: (1) Given the conflicting conclusions in the literature, what is the actual labor force participation situation of ethnic minority groups, especially ethnic minority women who face a “double disadvantage”? (Grönlund and Fairbrother, 2021); (2) How can we address sample selection bias in studies using cross-sectional and longitudinal panel data, and could this bias contribute to the contradictory findings? (3) While Western research focuses on immigrant ethnic minorities and their spatial concentration relative to mainstream populations, which is associated with poor individual outcomes (e.g., labor force participation, education, housing, access to services) (Caldwell et al. 2017), the situation in China is fundamentally different. The spatial concentration of ethnic minorities in China is legally recognized and protected under the system of regional ethnic autonomy. Additionally, many ethnic minority regions in China have historically been inhabited by the same groups, making the current system a continuation of historical traditions. This raises the question of whether there are significant labor force participation differences between ethnic minority women and Han women in China. Existing research has yet to provide adequate answers to these questions.

Therefore, this study utilizes data from the 2015 national 1% population sampling survey in China and applies a spatial regression discontinuity approach, focusing on Chinese women aged 16–65. ①We concentrate on the ethnic boundary, restricting the main regression sample to women within 11 km on either side of the boundary, resulting in a final sample of 2087 women.

Our empirical research yields three main findings: (1) There is a significant difference in FLFP between the two sides of the ethnic boundary: ethnic minority women have a 33.4 percentage point lower FLFP probability compared to Han women. This result remains robust across different bandwidths, functional forms, and when excluding certain samples. (2) Culture influences FLFP on both sides of the ethnic boundary through both labor demand and supply. (3) The cultural effect on FLFP on both sides of the ethnic boundary exhibits heterogeneity. Specifically, this effect is more pronounced among women aged 18–29 or over 40, those who are unmarried or married with a spouse, and those from families with two or fewer children. To enhance the robustness of the study, we excluded potential confounding effects such as institutional factors, non-random migration, or “sorting behavior”, to accurately identify the impact of culture.

Our study contributes to existing literature in at least three keyways. First, it empirically tests the causal effect of culture on the differences in FLFP on both sides of the ethnic boundary. This conclusion, based on the Chinese context, helps to further enrich the existing research on the impact of culture on labor participation among ethnic minority women. Second, by applying the spatial regression discontinuity design to the study of FLFP among ethnic minority women and restricting the analysis to a narrowly defined geographic area, we can more effectively isolate the cultural effect from other potential influences. Third, the use of large-scale official data from China provides detailed information on women’s job-seeking intentions and behaviors, offering a more comprehensive understanding of FLFP among ethnic minority women.

The structure of this paper is as follows: Section “Policy background” discusses the background of China’s system of regional ethnic autonomy. Section “Data and research design” presents the main data and empirical strategy used in the analysis. Section “Empirical results analysis” outlines our primary results, including baseline regressions, discussions on exogeneity, balance tests, robustness checks, and the exclusion of other influencing factors. Section “Mechanisms” provides a mechanism analysis, followed by a heterogeneity analysis in Section “Heterogeneity analysis”. Finally, Section “Conclusion and implications” offers the conclusions, discussion, and prospects for future research.

Policy background

At the First National People’s Congress held in 1954, the system of regional ethnic autonomy was written into the Constitution of the People’s Republic of China (hereinafter referred to as the “Constitution”). Under the premise that “the People’s Republic of China is a unified multi-ethnic state,” the Constitution stipulates that “regional autonomy shall be practiced in areas where ethnic minorities live in concentrated communities.” Since then, the system of regional ethnic autonomy has become a fundamental political institution in China, continuing to the present day. Regional ethnic autonomy refers to a system in which, under the unified leadership of the state, areas inhabited by ethnic minorities establish autonomous organs and exercise the right to self-governance (The State Council of the PRC, 2005). According to the Constitution and related regulations, ethnic autonomous areas are classified into three levels based on the size of the population and area: autonomous regions, autonomous prefectures, and autonomous counties. Autonomous organs in these regions are granted legislative powers, flexible administrative powers, fiscal and economic autonomy, cultural and linguistic autonomy, authority to organize public security forces, and preferential appointments for ethnic minority cadres. Under this system, ethnic minority regions and Han-majority regions share the same overarching institutional framework, both governed under the leadership of the Communist Party of China. At the same time, the Communist Party of China recognizes the unique economic, social, linguistic, cultural, religious, and customary characteristics of ethnic minorities and their regions (Hao, 2024)

Sichuan Province, located in southwestern China, is a large multi-ethnic region with 55 ethnic minority groups. The three major autonomous areas in Sichuan are Ganzi Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Aba Tibetan and Qiang Autonomous Prefecture, and Liangshan Yi Autonomous Prefecture. According to the results of the seventh national census, Sichuan has a population of 6.7884 million ethnic minorities, accounting for 8.11% of the total population of the province. This makes Sichuan a typical area for studying the cultural differences between ethnic minorities and the Han majority. Therefore, selecting Sichuan Province as the research focus is based on its unique ethnic composition and socio-cultural background, which facilitates a better understanding of the mechanisms by which culture influences FLFP on both sides of the ethnic boundary. Figure 1 shows a map of Sichuan Province, China. In the map, the yellow regions represent counties located in ethnic minority areas, and the blue regions represent counties located in Han-majority areas. Together, they form the sample area for this study. For research purposes, we define the overlapping administrative Boundary between ethnic minority and Han-majority areas (indicated by the red line) as the “ethnic boundary” in this paper. In the following sections, we will discuss the differences in FLFP on both sides of the ethnic boundary. Figure 1 shows that the ethnic boundary coincides with administrative Boundary, which requires us to distinguish the effects of institutional factors in our subsequent discussions. Additionally, we note that the sample on both sides of the ethnic boundary shares the same geographical environment, with no natural barriers between them.

The distance from the village where the female samples are located to the ethnic boundary is a key empirical concept in this paper. We construct this distance through the following three steps. First, based on the administrative Boundary of Sichuan, we categorize each village as belonging to either an ethnic minority region or a Han-majority region, determining whether the women in that village are situated in an ethnic minority region or a Han-majority region. Second, we calculate the shortest straight-line distance from a village to the ethnic boundary in kilometers. Finally, we use negative coding for distances of villages in Han-majority regions and positive coding for distances of villages in ethnic minority regions.

Figure 2 shows the proportion of ethnic minority population in villages at varying distances on both sides of the ethnic boundary in the sample database. ② On both sides of the ethnic boundary, the proportion of ethnic minority population is approximately 30% in the Han-majority regions on the left side, while it is around 50% in the ethnic minority regions on the right side. This significant discontinuity reflects the characteristics of the ethnic boundary. Although there are ethnic minority populations on both sides of the boundary, the proportion of ethnic minority populations differs noticeably, indicating a clear delineation effect on both sides of the ethnic boundary.

Data and research design

Data sources

The data for this study primarily comes from the 2015 National 1% Population Sampling Survey. This survey, which covers the entire country and uses municipalities (including districts, leagues, and states) as sub-units, employs a stratified, two-stage, probability-proportional-to-size, and cluster sampling method. It provides a rich sample size and extensive representativeness. The survey includes information at both household and individual levels, covering dimensions such as housing characteristics, individual demographic features, work and migration, and marriage and fertility. It is widely recognized in labor and population economic research. The data related to FLFP offers unique advantages for this study.

As shown in Fig. 1, the study focuses on 14 counties in Sichuan Province, China. Among these, the ethnic minority counties include Jiuzhaigou, Songpan, Wenchuan, Xiaojin, Dechang, Ganluo, Leibo, and Yanyuan; the Han counties include Baoxing, Pingxiang, Pingwu, Hanyuan, Miyu, and Lushan. From these 14 counties, we selected a sample of 13,557 females aged 16–65 from the 2015 National 1% Population Sampling Survey. This sample selection ensures that the cases are comparable.

Additionally, the study uses five-level vector data of Sichuan Province’s administrative divisions as the primary source of geographic information. Using ArcGIS software, various spatial processes were applied, including coordinate system conversion, projection parameter setting, and spatial data overlay analysis. This processing effectively extracted the geographic information needed for the research, ensuring consistency and accuracy.

In this study, “labor participation” is defined to include all production, business, and service activities performed by respondents to earn wages, in-kind rewards, or business income, whether fixed, temporary, or part-time. Any activity aimed at obtaining economic benefits, regardless of whether income is actually earned, is considered “labor participation.” This definition also includes labor performed by family members in their own businesses, such as stalls, shops, or factories, even if no income is generated. This broad definition allows for a more comprehensive understanding of the impact of culture on FLFP, particularly in rural and ethnic minority areas, capturing a wider range of economic activities and providing a thorough perspective on FLFP.

Model construction

Assessing the impact of culture on FLFP on both sides of the ethnic Boundary faces the challenge of endogeneity. For instance, there may be inherent differences between minority and Han women, such as differences in educational attainment. Therefore, a simple comparison of FLFP between minority and Han regions may suffer from reverse causality and omitted variable bias, leading to biased estimates. To address these endogeneity issues, this study employs a spatial regression discontinuity (SRD) design (Ding et al. 2021). As illustrated in Fig. 1, the green-shaded area represents counties in minority regions, and the red-shaded area represents counties in Han regions. The overlapping area of minority and Han administrative regions (indicated by the blue line) constitutes the “ethnic boundary”. We design the study based on the longitude and latitude information of villages where the female samples reside. Women in villages located in minority regions are designated as the treatment group, indicating that they are influenced by minority culture. Conversely, women in villages located in Han regions are designated as the control group, indicating exposure to different cultural influences. By comparing the labor participation rates of women near the ethnic boundary on either side, we aim to identify the cultural impact effects.

Specifically, following the approaches of Dell (2010), He et al. (2020), and Jia et al. (2021), the empirical model constructed in this paper is as follows:

where \({Y}_{ci}\) indicates whether female i in county c participated in labor in 2015; \({{\rm{EthnicMinority}}}_{ci}\) indicates whether county c is a minority region, with a value of 1 if it is a minority region and 0 otherwise, meaning that female samples from minority regions are the treatment group, and female samples from Han regions are the control group; \({\rm {Dis{t}}}_{i}\) is the driving variable, representing the shortest distance from village I to the ethnic boundary, with positive values if the village is in a minority region and negative values if it is in a Han region; we also include the interaction term \({{\rm{EthnicMinority}}}_{ci}\times {\rm {Dis{t}}}_{i}\) to control for the trend of the distance to the ethnic boundary; \({\varepsilon }_{i}\) is the error term.

The coefficient \({\alpha }_{1}\) is the core coefficient of interest in this study, measuring the impact of culture on FLFP on either side of the ethnic boundary. As discussed by Gelman and Imbens (2019), Eq. (1) can be estimated using either non-parametric local linear methods or global polynomial functions. Gelman and Imbens (2019) note that estimates obtained using polynomial function forms are often affected by the degree of the polynomial and may exhibit other undesirable statistical properties. Therefore, following the approach of He et al. (2020) and Jia et al. (2021), this study employs the local linear method for the baseline regression. The bandwidth hhh is the size of the bandwidth for estimation, and this study uses the optimal bandwidth (h = 11 km) chosen by Calonico et al. (2014), which corresponds to a distance of 11 km on either side of the ethnic boundary, for estimation, and then conducts robustness checks using nearby bandwidths.

Empirical results analysis

Baseline regression results

Before presenting the empirical regression results, this paper first illustrates the relationship between the running variable and the outcome variable on both sides of the ethnic boundary. Figure 3 provides the graphical evidence. The horizontal axis in the figure represents the distance, which is the running variable, where the “zero point” marks the ethnic boundary. Samples distributed to the right of the “zero point” (positive distance values) represent women in ethnic minority regions, constituting the treatment group. Conversely, samples to the left of the “zero point” (negative distance values) represent Han women, serving as the control group. The figure shows a noticeable jump in the probability of FLFP on both sides of the ethnic boundary in 2015, indicating that FLFP among ethnic minority women on the right side is significantly lower than that of Han women on the left side. This provides initial evidence of the cultural impact on FLFP on both sides of the ethnic boundary.

Table 1 reports the baseline regression results under a linear functional form with the optimal bandwidth of 11 km. In column 1, no control variables are included, while column 2 adds individual and household controls, and column 3 incorporates controls for county-level factors and the local labor market. The results show that regardless of whether control variables are included, the direction and significance of the estimated coefficients remain unchanged, with only minor variations in magnitude. Considering that FLFP can be influenced by multiple factors such as individual characteristics, household conditions, the local socioeconomic environment, and the analysis. This indicates that within the optimal bandwidth (h = 11 km), the probability of FLFP among ethnic labor market, the results in column 3, which include all control variables, are regarded as the baseline for further minority women on the right side of the ethnic boundary is significantly lower than that of Han women on the left side by 33.4 percentage points. Furthermore, the further the distance from the ethnic boundary, the more pronounced this trend becomes. Since the dependent variable is a binary indicator of whether a woman worked in the past week, the regression coefficient reflects the probability difference in FLFP on both sides of the ethnic boundary. Specifically, the results suggest that cultural factors reduce the probability of FLFP among ethnic minority women by 33.4 percentage points compared to Han women at the boundary.

After obtaining the baseline results, we applied the same methodology and variables to conduct a regression analysis on the male sample, with the results shown in column 4 of Table 1. The findings indicate that the estimated coefficient is not statistically significant, suggesting that current evidence cannot explain differences in male labor force participation on both sides of the ethnic boundary. This observed gender difference underscores the importance of accounting for gender-specific factors when analyzing the cultural impact on FLFP on both sides of the ethnic boundary.

Discussion on the exogeneity of the running variable

The core assumption of the spatial regression discontinuity (SRD) identification strategy is that the formation of the ethnic boundary is relatively exogenous. In the absence of the ethnic boundary, women on either side of the boundary, when infinitely close to it, would be comparable. Thus, any discontinuous jump in the conditional distribution function of the outcome variable at the “zero point” can be attributed to cultural factors. This is the fundamental rationale behind the SRD identification strategy. To determine whether the ethnic boundary is exogenous, it is necessary to analyze the formation of China’s system of ethnic regional autonomy. This system was established after the founding of the People’s Republic of China. During the process of incorporating the previously independent regional ethnic governance systems into the new state governance framework, the central government paid great attention to the history, circumstances, and sentiments of ethnic minority regions. By adopting local ethnic minority traditions, ceremonies, and other forms, the government sought to minimize conflict between the two sides (Calonico et al. 2014). In other words, the formation of China’s system of ethnic regional autonomy was built on the historical and contemporary realities of ethnic minorities. As a result, the administrative Boundary of the ethnic autonomous regions largely followed historical administrative divisions adjacent to Han regions. Historically, administrative regions in China often used natural features such as mountains and rivers as boundaries (Zhou, 2013). Existing studies also indicate that the current ethnic distribution pattern in China is primarily the result of China’s migration history (Huang et al. 2023). Therefore, the ethnic boundary selected in this study, which refers to the administrative boundary between ethnic minority autonomous areas and adjacent Han regions, can be considered shaped by natural factors rather than human intervention, making it relatively exogenous.

Additionally, most of the ethnic boundaries selected in the sample are not geographical barriers. Although the terrain in Sichuan is relatively complex, especially since the chosen autonomous prefectures are located in high-altitude areas, decades of construction and development have resulted in a highly efficient transportation system within Sichuan Province. This means that the transportation costs within ethnic minority regions and between ethnic minorities and Han populations are similar, given comparable distances. Consequently, the potential impact of transportation difficulties on FLFP can be ruled out.

Of course, based on the above explanation, we cannot entirely rule out the possibility of differences between ethnic minorities and Han regions on either side of the ethnic boundary. To address these potential influences, the subsequent empirical analysis in this paper specifically discusses and controls these factors, thereby mitigating the impact of any differences that might arise from them.

Stationarity analysis

Furthermore, the robustness assumption is also one of the identification assumptions required for the regression discontinuity design (Jia et al. 2021). This means that, aside from the treatment variable, all other variables should exhibit continuity and smooth variation at the cutoff point (the ethnic boundary). Existing research indicates that observed inequalities between different racial groups may be related to characteristics such as demographics (Patias et al. 2023). Therefore, we conduct a robustness check on the series of characteristics of female samples on either side of the ethnic boundary to rule out that the discontinuity effect in the outcome variable is due to discontinuities in other factors. Table 2 reports the sample means for each variable (column 1), the means for ethnic minority women (column 2), the means for Han women (column 3), the significance of differences between the two groups (column 4), and the differences between the two groups within the optimal bandwidth (11 km) on either side of the ethnic boundary (column 5). We find that, within the optimal bandwidth on both sides of the ethnic boundary, only age does not show significant statistical differences. This indicates that there are still imbalances in certain background characteristics between ethnic minorities and Han women on either side of the ethnic boundary. Do these differences contribute to the variation in FLFP on both sides of the ethnic boundary? And could there be unobserved variables influencing this? To further analyze this issue, we undertook the following two approaches.

On the one hand, we plotted the discontinuity graphs for the variables showing significant differences between ethnic minority and Han women within 11 km on either side of the ethnic boundary, as shown in Fig. 4. Overall, these variables exhibit continuity and smooth variation at the cutoff point, which rules out potential impacts from these factors.

Second, we used cross-sample prediction to discuss the overall impact of individual background characteristic imbalances on FLFP differences on both sides of the ethnic boundary. As mentioned earlier, we observed imbalances in background characteristics between ethnic minorities and Han women on either side of the boundary. While we have ruled out potential impacts from these factors, unobserved individual characteristics may still exist and could influence FLFP. Therefore, we first performed a logistic regression on FLFP in Han regions, using individual, family, county, and labor market control variables. We then used the parameters obtained from the Han region regression along with the characteristics of the ethnic minority female sample to predict the labor force participation of women living in ethnic minority regions. Similarly, we predicted the labor force participation of women living in Han regions. The results are shown in Fig. 5.

Figure 5 shows the actual FLFP differences on both sides of the ethnic boundary in the upper graph, while the lower graphs display the predicted labor force participation for Han regions (left) and ethnic minority regions (right). By comparing the actual and predicted results, we can assess the impact of background characteristic imbalances on the labor force participation differences between women on either side of the ethnic boundary. Figure 5 illustrates the average unemployment probabilities on either side of the ethnic boundary (solid line) and the predicted average unemployment probabilities (dashed line). The fitted line for Han women on the left side of the upper graph (around 0.89) is similar to the predicted fitted line for ethnic minority women on the right side of the lower graph (around 0.89). However, the fitted line for ethnic minority women on the right side of the upper graph (around 0.60) is significantly lower than the predicted fitted line for Han women on the left side of the lower graph (around 0.79). This indicates that the discontinuity remains. In summary, the observed differences in female individual characteristics do not effectively explain the labor force participation differences between women on either side of the ethnic boundary. Even when controlling for these background characteristics, the differences in female unemployment probabilities on both sides of the ethnic boundary persist. If unobserved female characteristics follow a similar imbalance pattern as the observed ones, the differences in labor force participation between women on either side of the ethnic boundary would still exist. The stationarity analysis indicates that the differences in individual characteristics of women on both sides of the ethnic boundary cannot effectively explain the variations in FLFP across the boundary. This, to some extent, also rules out the potential impact of non-random migration or “Sorting Behavior.”

Robustness check

Changing bandwidth and functional specifications

Imbens and Lemieux (2008) noted that in regression discontinuity models, the sensitivity of the estimated coefficients is closely related to the choice of bandwidth To validate the robustness of the baseline regression results, we tested other bandwidths close to the optimal bandwidth. Panel A of Table 3 reports the regression results for different bandwidth intervals (h = ±9 to h = ±14 km) under a local linear functional specification, all of which are consistent with the results obtained using the optimal bandwidth in column 3.

We further tested the robustness of the baseline regression results by changing the functional specification. Panel B of Table 3 reports the regression results under a quadratic functional specification. The regression coefficient for the optimal bandwidth in column 3 is −0.4385, which is consistent with the results obtained under the linear functional specification in Panel A. The estimated results for various bandwidth intervals in the remaining columns of Panel B are also significantly negative. This indicates that the regression results remain robust across different functional specifications and bandwidth intervals.

Overall, after changing the bandwidth and functional specification, the magnitudes of the regression coefficients in Table 3 vary slightly, but the direction of the coefficients remains unchanged. This suggests that the baseline regression results of this study are not dependent on the choice of bandwidth and functional specification, demonstrating the robustness of the findings—specifically, that the labor force participation probability of ethnic minority women on the right side of the ethnic boundary is significantly lower than that of Han women. Therefore, all subsequent regression results in this study use local linear regression point estimates and a triangular kernel weighting function.

Excluding certain samples

Firstly, we exclude samples from Han counties with relatively high proportions of ethnic minorities. As the economy and society continue to develop, interactions between Han and minority residents in ethnic boundary areas have become more frequent, leading to situations where some Han areas have a relatively high proportion of minority populations. To eliminate the impact of Han counties with a high proportion of ethnic minorities on the research conclusions, we exclude Pingwu County (where the proportion of ethnic minorities is close to 30%) and its neighboring counties, Jiuzhaigou and Songpan. The results in Column 1 of Table 4 show that after excluding Han counties with high proportions of ethnic minorities, the significant difference in FLFP on both sides of the ethnic boundary remains robust.

Secondly, we exclude samples from non-working-age individuals. Since the labor participation defined in this study includes domestic work and other activities, the sample initially consists of women aged 16–65. However, considering China’s retirement age regulation for women at 55, we exclude non-working-age samples by selecting only women aged 16–55 for testing to reduce the impact of retirees. The results in Column 2 of Table 4 show that after excluding non-working-age samples, the significant difference in FLFP on both sides of the ethnic boundary remains robust.

Placebo test: excluding institutional effects

Lonati et al. (2024) argue that while cultural theories are clear, the empirical reality is far more complex. The issue is that groups exhibiting different cultural characteristics may also differ in non-cultural characteristics, such as ecological environments (North, 1991), institutional environments (Manski, 1993), and demographic factors (North, 1991). Therefore, when relying on observational data, it is not possible to determine whether cultural factors or some related, unobserved factors are causing the behavioral differences at the group level (LaVeist et al. 2023). Our study addresses the issues of ecological and randomness differences by using a spatial discontinuity regression model and resolves demographic characteristic differences through stability tests and cross-sample predictions. For the impact of institutional environments, we use placebo tests with samples from the same administrative regions to enhance the robustness of the baseline regression conclusions.

As previously mentioned, the ethnic boundary selected in our study overlaps with administrative divisions. This means that the differences in labor participation rates between ethnic minorities and Han women at the ethnic boundary may also be attributed to differences in institutional settings across regions. Specifically, ethnic minority counties and Han counties might be governed by different cities or autonomous prefectures, and thus subject to varying city-level policies. Therefore, selecting samples on both sides of the ethnic Boundary within the same administrative division is crucial for accurately identifying the cultural effects on both sides of the ethnic boundary. If significant differences in FLFP persist on both sides of the ethnic boundary within the same administrative division, it indicates that institutional factors do not play a significant role. Fortunately, we can find samples that meet these conditions in Leshan and Mianyang in China: Ebian Yi Autonomous County, Mabian Yi Autonomous County, Muchuan County in Leshan, Beichuan Qiang Autonomous County, and Pingwu County in Mianyang. Through data processing, we obtained the placebo test results shown in column 3 of Table 4. The results indicate that, within the same institutional level, significant differences in FLFP rates on both sides of the ethnic boundary still exist, similar to the baseline results (with variations in values but unchanged direction and significance). This suggests that in our current discussion, institutional factors are not the primary determinant of FLFP on both sides of the ethnic boundary, nor are they the driving force behind the differences in labor participation rates at the boundary.

In fact, the baseline regression results (column 4 of Table 1) indicate that culture has a significant effect on FLFP on both sides of the ethnic boundary, but no significant impact on males. This suggests that the observed differences are indeed due to cultural effects rather than institutional influences. If institutional factors were driving the differences in FLFP on both sides of the ethnic boundary, they should also significantly affect male labor participation rates at the boundary. This is because if the impact were due to the ethnic regional autonomy system, all residents on both sides of the ethnic boundary should experience similar differences, rather than showing gender-specific disparities. Cultural gender norms, as hegemonic “rules of the game,” influence behavior, performance, and evaluation of individuals differently based on gender (Grönlund and Fairbrother, 2021). From this perspective, it can be concluded that the institutional factors do not significantly affect FLFP on both sides of the ethnic boundary, allowing for a precise identification of the cultural impact in this process.

However, it is important to clarify that our discussion focuses on the situation within different regions (cities/autonomous prefectures) within the same province, specifically within a certain range on either side of the ethnic boundary. Thus, while in the context of our current discussion, institutions are not the driving factor behind the differences in FLFP on both sides of the ethnic boundary, it is still possible that institutions could influence FLFP between minority and Han regions overall. However, this is beyond the scope of the current discussion.

Excluding the potential impact of non-random migration or “sorting behavior”

The SRD method requires a strong exogeneity of the cutoff point, meaning that the running variable cannot be manipulated by the study subjects. However, it is possible that residents migrate non-randomly on both sides of the ethnic boundary. More importantly, minority women might migrate based on their ability levels: those with higher abilities might move to Han areas seeking better job opportunities, while those with lower abilities remain in minority areas. Such “sorting behavior” could severely violate the core assumptions of the SRD method and compromise the robustness of the conclusions.

Based on existing studies, we calculated the optimal bandwidth of 11 km, focusing on areas within 11 km on both sides of the ethnic boundary. Given the small economic and social differences over such a short distance, even if some higher-ability minority women consider migration, they are more likely to move to more economically developed areas rather than migrate to nearby Han areas within 11 km of the ethnic boundary. From this perspective, a more likely scenario is that minority women who continue to live near the ethnic boundary may have relatively lower educational attainment due to potential non-random migration or “sorting behavior.” If we compare only the less-educated women on both sides of the boundary and find significant results, it would suggest that possible migration or “sorting behavior” does not affect the robustness of our conclusions.

To this end, we divided the sample into two groups based on education level: high and low educational attainment. The results are presented in columns 1 and 2 of Table 5 (column 3 shows the baseline regression results for comparison). The results indicate that for less-educated women, the differences in labor force participation rates between women on both sides of the ethnic boundary persist, suggesting that potential non-random migration and “sorting behavior” do not compromise the robustness of our conclusions.

In fact, Table 5 also shows that the cultural impact on the FLFP on both sides of the ethnic boundary is independent of their educational attainment. Since educational attainment somewhat represents women’s “abilities,” this further supports the notion that potential non-random migration or “sorting behavior” does not affect the robustness of the study’s conclusions.

Mechanisms

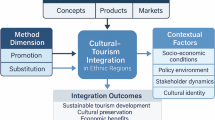

The benchmark regression result and robustness checks above indicate that the labor participation probability of ethnic minority women on both sides of the ethnic boundary is significantly lower than that of Han women. So, how does culture create the ethnic boundary effect on FLFP? There are two main dimensions affecting labor participation: labor demand and labor supply (Bhalotra and Fernández, 2024). From the perspective of labor demand, if the demand for female labor in ethnic minority areas is lower than in Han areas, then the labor participation probability of ethnic minority women would be lower. From the perspective of labor supply, if the labor supply from ethnic minority women is lower, their labor participation probability would also be lower. It is important to note that the definition of “labor participation” in this study not only includes traditional external employment but also encompasses all forms of income-generating activities within the household or in agricultural labor. This broad definition of labor participation allows us to gain a more comprehensive understanding of how culture affects the labor participation differences between women on either side of the ethnic boundary. Therefore, this section will explore the reasons why ethnic minority women near the ethnic boundary have lower labor participation probabilities from both the demand and supply dimensions, as illustrated in Fig. 6.

At the level of labor demand, culture can influence the career choices of ethnic minority women (Arifeen and Syed, 2024). If ethnic minority cultures tend to favor careers that are more aligned with family responsibilities, and if the local labor market has a lower demand for such careers, this could reduce the willingness of local women to participate in the labor market, ultimately decreasing their labor participation probability. At the level of labor supply, the family is a primary organization for social reproduction, including but not limited to labor participation (Arifeen and Syed, 2024). Relatively conservative cultures, such as those of ethnic minorities, emphasize that women should invest more energy in household responsibilities (Tosun, 2022). This can reinforce the psychological tendency for women to focus on family care rather than external employment, thereby weakening their motivation to prepare for and engage in labor participation. In this situation, ethnic minority women might spend more time on household care, thereby reducing their labor participation. We use the sample database to test these mechanisms.

Labor demand dimension

This section primarily explores the cultural impact mechanism from the perspective of the labor market. Although the database lacks direct data on labor markets and industrial structure, we have found that insufficient demand for female labor in the local labor market reduces local women’s willingness to participate in the labor force. Therefore, we can analyze the local labor market’s demand for female labor by examining the willingness of women to participate in the labor force.

Willingness to participate in the labor force refers to an individual’s initiative and inclination to seek employment or engage in work. In this analysis, we measure this willingness by surveying women’s attitudes and expectations regarding labor participation. As shown in column 1 of Table 6, the regression coefficient is negative and significant. This indicates that, on both sides of the ethnic boundary, minority women exhibit lower labor force participation intentions compared to Han women. The possible reason lies in the influence of traditional minority cultures on women’s labor participation, which expects women to take on more familial roles. Preliminary field research found that in minority cultures, women are often assigned greater family responsibilities (such as child-rearing and household chores), whereas, in Han culture, the division of family roles has become more flexible with modernization, leading to relatively higher labor market participation intentions among women. This difference in family role division, on the one hand, increases the time cost of family responsibilities for minority women, reducing their likelihood of labor market participation; on the other hand, it reinforces social norms emphasizing women’s roles within the family, further diminishing their career aspirations. This is consistent with the findings of Grönlund and Fairbrother (2021), who argue that culture affects women’s employment outcomes by reinforcing their roles within the family. Clearly, the lower labor participation willingness among minority women partially reflects the lower market demand for minority female labor in the local labor market, which in turn reduces their overall labor participation probability.

We further seek to understand why minority cultures lower the local labor market’s demand for female labor. The results in columns 2–4 of Table 6 indicate that, on either side of the ethnic boundary, minority women are less likely than Han women to be engaged in agricultural production and the hospitality industry, with no significant difference in sales occupations (Autor et al. 2013). A possible reason is that agricultural production and food service jobs are often perceived as requiring higher physical strength or greater public involvement, and these roles are typically viewed as male-dominated. Minority cultures tend to encourage women to choose occupations that are more compatible with family responsibilities and even avoid fields culturally considered male-dominated. Given that agriculture and tourism are dominant industries in Sichuan’s minority regions, this economic characteristic further reduces the local market’s demand for female labor, which likely lowers the labor participation willingness of minority women.

The mechanism by which culture influences the labor demand for minority women can be explained as follows: Minority cultures expect women to favor occupations that align with family responsibilities and avoid male-dominated roles. In Sichuan’s minority regions, the economic development characteristics offer fewer job opportunities that meet these cultural expectations for women, which reduces the labor participation willingness of minority women. This, to some extent, reflects a lower demand for minority women’s labor in the local labor market, thereby decreasing their labor participation probability.

Labor supply dimension

This section primarily examines the cultural influence mechanism from the perspective of female behavior. Specifically, we attempt to investigate whether minority women exit the labor market more due to family caregiving and what reasons contribute to this behavior. This may reflect the impact of culture on the strength of gender and family beliefs.

First, we examine whether minority cultures lead women to exit the labor market more due to family caregiving. The database includes a survey on reasons for not working, with one option being “not working due to family caregiving.” We generated a binary variable indicating a value of 1 if the reason for not working was family caregiving. The regression results, shown in column 5 of Table 6, indicate a positive and significant coefficient. This suggests that on both sides of the ethnic boundary, minority women are more likely to exit the labor market due to family caregiving. The likely reason is that minority cultures have more defined traditional gender roles, with women typically expected to assume greater family responsibilities. This cultural view may lead women to prioritize family responsibilities over career choices, thereby exiting the labor market. This finding is consistent with existing research, which suggests that minority cultures lead women to focus more on family, thereby reducing labor market participation (Grönlund and Fairbrother, 2021).

To further understand why minority women are more likely to exit the labor market due to family caregiving, we analyzed the level of labor market preparation among women on either side of the ethnic boundary. The regression results shown in column 6 of Table 6 indicate a negative and significant coefficient. This suggests that on both sides of the ethnic boundary, minority women have lower levels of labor market preparation. The possible reason is that minority cultures emphasize family caregiving for women over employment, which may lead minority women to lack information about career development or perceive limited opportunities for career advancement. This psychological inadequacy might reduce their competitiveness in the labor market or even lead them to voluntarily opt out of labor market participation.

The mechanism through which culture affects minority women’s labor supply can be explained as follows: Culture shapes women’s roles and behavioral choices within the family, reinforcing traditional gender roles and family responsibilities. This cultural framework psychologically diminishes minority women’s preparation for labor market participation, making them more inclined to prioritize family responsibilities. As a result, they are more likely to exit the labor market due to family obligations, further reducing their labor market participation probability.

In summary, minority culture affects women’s labor market participation through both labor demand and supply channels. On the demand side, minority culture encourages women to choose jobs that align with family responsibilities and avoid male-dominated fields. As local economic development provides fewer such jobs, the demand for minority women’s labor in the market decreases, thereby affecting their labor participation probability. On the supply side, minority culture shapes women’s roles within the family, reinforcing traditional gender roles and family responsibilities. This cultural influence psychologically reduces their labor market preparation, making them more likely to exit the labor market due to family obligations, thereby diminishing their likelihood of labor market participation.

Heterogeneity analysis

A further question is: Which groups of women are more affected by culture in terms of FLFP on either side of the ethnic boundary? Answering this question can provide more substantial evidence for the mechanism analysis presented earlier. When discussing FLFP, it is essential to consider factors such as age, educational attainment, marital status, and number of children. Since we have already examined educational attainment, this study conducts a heterogeneity analysis from the perspectives of age, marital status, and childbearing.

Considering that childbirth may lead to differentiated labor force participation among women, we classified women into three age groups based on their reproductive status: 18–29 years (peak childbearing age), 30–39 years (likely to have preschool or school-age children), and 40 years and above (reduced childbearing activity). The regression results in Table 7 show that the coefficients for the 18–29 and 40+ age groups are both significant, indicating that culture has a greater impact on FLFP on both sides of the ethnic boundary for women in these age ranges. However, the coefficient for the 30–39 age group is not statistically significant, suggesting that the current evidence does not sufficiently support the idea that culture influences FLFP for women in this age group. Therefore, cultural effects are more pronounced among women aged 18–29 and 40 years and above, while the impact on those aged 30–39 remains unclear and may require further research for deeper exploration.

Marital status is a crucial factor influencing FLFP, as women in different marital situations face varying levels of family responsibilities and social support when entering the labor market. We classified women into three categories based on their marital status: unmarried, married with a spouse, and divorced or widowed. The regression results in Table 7 show that the coefficients for the unmarried and married with a spouse group are both significant, indicating that culture has a greater impact on FLFP on both sides of the ethnic boundary for women in these marital statuses. However, the coefficient for the divorced or widowed group is not statistically significant, suggesting that the current evidence does not sufficiently support the idea that culture influences FLFP for women in this group. Therefore, cultural effects are more pronounced among unmarried and married women with spouses.

The number of children is an important factor influencing FLFP, as women in families with different numbers of children face varying levels of family responsibilities and time constraints when participating in the labor market. We categorized households into three groups based on the number of children: no children or one child, two children, and three or more children. The regression results in Table 7 show that the coefficients for the no children/one child group and the two children group are both significant, indicating that culture has a greater impact on FLFP on both sides of the ethnic boundary for women in these family structures. However, the coefficient for the group with three or more children is not statistically significant, suggesting that the current evidence does not sufficiently support the idea that culture influences FLFP for women in this group. Therefore, cultural effects are more pronounced among women in families with no children or one child, as well as those with two children.

Conclusion and implications

This study, from a micro-level perspective of women, leverages the unique historical and institutional context of the “ethnic boundary” between China’s ethnic minorities and the Han majority. By utilizing diverse economic and geographic data and employing a spatial regression discontinuity model, it empirically analyzes the impact of culture on FLFP on both sides of the ethnic boundary. The findings demonstrate that culture is a key factor driving FLFP differences on either side of the ethnic boundary, contributing significantly to the existing body of research on the cultural influences on women’s labor participation.

The study reveals the following findings: (1) The baseline regression results indicate that on both sides of the ethnic boundary, the probability of FLFP among ethnic minority women is significantly lower than that of Han women. This difference reaches 33.4 percentage points at the optimal bandwidth (h = 11 km). This conclusion remains robust across different bandwidths and model specifications, and placebo tests rule out potential confounding effects from factors such as institutional settings and educational attainment. (2) Mechanism analysis shows that ethnic minority culture influences FLFP through both labor demand and supply dimensions. On the one hand, minority culture encourages women to choose occupations that align with family responsibilities and avoid male-dominated fields. However, the mismatch between local economic development and cultural expectations for women’s roles lowers their FLFP. On the other hand, minority culture reinforces traditional gender roles and family obligations, psychologically reducing women’s readiness to participate in the labor force and making them more likely to exit the labor market to care for their families. (3) Heterogeneity analysis reveals that the cultural effect on both sides of the ethnic boundary is more pronounced among women aged 18–29 or over 40, those who are unmarried or married with a spouse, and those from families with two or fewer children. This suggests that the diverse and complex influence of culture varies across different age groups and family structures. It should be noted that the conclusions of this study primarily apply to minority communities near the ethnic boundary, where traditional cultural influences are stronger. The impact of culture on FLFP is particularly significant in these areas. Therefore, the policy recommendations of this paper are more applicable to such regions and should not be readily generalized to other areas with weaker cultural influences.

Considering that cultural transformation is a long-term and complex process, overly aggressive cultural policies may exacerbate social tensions and conflicts. Therefore, while respecting cultural traditions, we propose the following flexible measures to improve the social environment for minority women’s labor force participation. (1) Strengthen vocational training and employment support for ethnic minority women. Based on the economic characteristics of areas on both sides of the ethnic boundary, vocational training programs aligned with the local economic structure should be developed, such as agricultural production skills, handicraft making, or service industry skills training, to enhance minority women’s job readiness and market competitiveness. (2) Promote gender equality through cultural education and awareness. Incorporating ethnic minority cultural customs, gender equality concepts should be promoted through community activities and traditional festivals to foster cultural transformation. At the same time, targeted educational programs should be implemented to help women and families better understand and accept the concept of modern gender division of labor. (3) Optimize labor market policies to increase demand for female labor. On both sides of the ethnic boundary, the government should encourage businesses to offer flexible positions (such as part-time or remote work) to reduce the limitations of family responsibilities on FLFP. At the same time, special funds could be established to support FLFP or assist in community economic development, providing more employment opportunities that cater to the needs of women.

However, this study has certain limitations. First, due to data constraints and analytical limitations, it was not possible to conduct a more detailed balance analysis of labor market conditions and labor demand. Future research should aim to improve data coverage to achieve more precise analysis and conclusions. In addition, given the limitation to data from Sichuan, future research will consider expanding this method and framework to other provinces with ethnic boundary, especially in western regions such as Yunnan and Gansu, to further verify whether the conclusions and mechanisms of this study are universally applicable across regions. Second, while some studies use ethnicity as a proxy for culture, it is important to acknowledge that ethnicity and culture often overlap with concepts such as religion. Future research could further explore the distinction between religion and culture and analyze the specific impact of religious factors on the labor force participation of ethnic minority women, providing a more comprehensive understanding of cultural factors. Third, due to data limitations, this study only addresses the differences in FLFP within a certain range on either side of the ethnic boundary. Future research could further explore the generalizability of this impact.

Numbered endnotes

①According to China’s current regulations on retirement age, the appropriate selection should be women aged 16–55. However, considering that the sample database used in this study defines labor participation in a broad sense, encompassing not only traditional external work but also all forms of income-generating activities within the household or in agricultural labor, we have determined the age range for this group to be 16–65. Of course, to account for the impact of age on work itself, we excluded the non-working age group in the robustness tests, and the results remained stable.

②For the noise points present in the figure (or similar figures discussed in this paper), we conducted the following tests: (1) Standardized residual analysis: The absolute values are <3 and no significant outliers were found, indicating that these points do not have a significant impact on the fit of the regression model. (2) Heteroscedasticity test (Breusch–Pagan): We performed a heteroscedasticity test, and the residual variance p-value was 0.0583, which means we cannot reject the null hypothesis, suggesting that the residual variance is homoscedastic and there is no heteroscedasticity issue. Therefore, the influence of the noise points on model fitting is limited, further confirming the reliability of the regression model. (3) From a theoretical perspective, the noise points may reflect the diversity of the sample data rather than the abnormality of the data. (4) We also tested the robustness by changing the bandwidth and function specifications, removing some samples with potential high leverage, conducting placebo tests, and excluding non-random migration or “sorting behavior” effects. The results remained significant. This further suggests that the noise points did not significantly affect the robustness of the conclusions.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Strawberry Research Network but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under licence for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of Strawberry Research Network (https://www.caomeikeyan.com).

References

Arifeen SR, Syed J (2024) Social reproduction and gender beliefs of ethnic minority women. Gend Work Organ 31(4):1230–1249

Autor DH, Dorn D, Hanson GH (2013) The China syndrome: local labor market effects of import competition in the United States. Am Econ Rev 103(6):2121–2168. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.103.6.2121

Battu H, Zenou Y (2009) Oppositional identities and employment for ethnic minorities: evidence from England. IZA Discussion Paper No. 4517. Institute of Labor Economics (IZA)

Beckhusen J, Florax RJGM, de Thomas G, Poot J, Waldorf B (2013) Living and working in ethnic enclaves: English Language proficiency of immigrants in US metropolitan areas. Pap Reg Sci 92(2):305–329. https://doi.org/10.1111/pirs.12023

Bénabou R, Tirole J (2005) Belief in a just world and redistributive politics. Q J Econ 121:699–746. https://doi.org/10.3386/w11208

Bhalotra S, Fernández M (2024) The rise in women’s labor-force participation in Mexico—supply vs. demand factors. World Bank Econ Rev 38(2):319–350. https://doi.org/10.1093/wber/lhad025

Caldwell JT, Ford CL, Wallace SP, Wang MC, Takahashi LM (2017) Racial and ethnic residential segregation and access to health care in rural areas. Health Place 43:104–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2016.11.015

Calonico S, Cattaneo MD, Titiunik R (2014) Robust nonparametric confidence intervals for regression-discontinuity designs: robust nonparametric confidence intervals. Econometrica 82(6):2295–2326. https://doi.org/10.3982/ECTA11757

Constant A, Zimmermann KF (2008) Measuring ethnic identity and its impact on economic behavior. J Eur Econ Assoc 6:424–433

Dell M (2010) The persistent effects of Peru’s mining Mita. Econometrica 78(6):1863–1903

Ding H, Chen Y, Yu M, Zhong J, Hu R, Chen X, Wang C, Xie K, Eggleston K (2021) The effects of chronic disease management in primary health care: evidence from rural China. J Health Econ 80:102539. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2021.102539

Eugster B, Lalive R, Steinhauer A, Zweimüller J (2017) Culture, work attitudes, and job search: evidence from the Swiss language border. J Eur Econ Assoc 15(5):1056–1100. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeea/jvw024

Gelman A, Imbens G (2019) Why high-order polynomials should not be used in regression discontinuity designs. J Bus Econ Stat 37(3):447–456. https://doi.org/10.1080/07350015.2017.1366909

Grönlund A, Fairbrother M (2021) No escape from tradition? Source country culture and gendered employment patterns among immigrants in Sweden. Int J Sociol 52(1):49–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207659.2021.1978192

Hao S (2024) Regional ethnic autonomy: a great innovation in the construction of the sociallist system with Chinese characteristics—commemorating the 40th anniversary of the promulgation ofthe law on regional ethnic autonomy Thinking 50(5):1–13

He G, Wang S, Zhang B (2020) Watering down environmental regulation in China. Q J Econ 135(4):2135–2185

Heath AF, Di Stasio V (2019) Racial discrimination in Britain, 1969–2017: a meta‐analysis of field experiments on racial discrimination in the British labour market. Br J Sociol 70(5):1774–1798. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-4446.12676

Huang W, Pan Y, Zhou Y (2023) One-child policy, marriage distortion, and welfare Loss. Rev Econ Stat 1–47. https://doi.org/10.1162/rest_a_01332

Imbens GW, Lemieux T (2008) Regression discontinuity designs: a guide to practice. J Econ 142(2):615–635. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2007.05.001

Jia J, Liang X, Ma G (2021) Political hierarchy and regional economic development: Evidence from a spatial discontinuity in China. J Public Econ 194:104352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104352

Jia R, Persson T (2021) Choosing ethnicity: the interplay between individual and social motives. J Eur Econ Assoc 19(2):1203–1248. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeea/jvaa026

Kluve J (2010) The effectiveness of European active labor market programs. Labour Econ 17(6):904–918. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2010.02.004

Koopmans R (2015) Does assimilation work? Sociocultural determinants of labour market participation of European Muslims. J Ethn Migr Stud 2(42):197–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2015.1082903

LaVeist TA, Pérez-Stable EJ, Richard P, Anderson A, Isaac LA, Santiago R, Okoh C, Breen N, Farhat T, Assenov A, Gaskin DJ (2023) The economic burden of racial, ethnic, and educational health inequities in the US. JAMA 329(19):1682. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2023.5965

Li Y, Heath A (2018) Persisting disadvantages: a study of labour market dynamics of ethnic unemployment and earnings in the UK (2009–2015). J Ethn Migr Stud 46(5):857–878. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1539241

Lindbeck A, Nyberg S (2006) Raising children to work hard: altruism, work norms, and social insurance*. Q J Econ 121(4):1473–1503. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/121.4.1473

Lonati S, Lalive R, Efferson C (2024) Identifying culture as cause: challenges and opportunities. Evol Hum Sci 6:e9. https://doi.org/10.1017/ehs.2023.35

Longhi S (2020) A longitudinal analysis of ethnic unemployment differentials in the UK. J Ethn Migr Stud 46(5):879–892. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1539254

Manski CF (1993) Identification of Endogenous Social Effects: The Reflection Problem. Rev Econ Stud| Oxf Acad Rev Econ Stud 60(3):531–542

Mok TM, Platt L (2020) All look the same? Diversity of labour market outcomes of Chinese ethnic group populations in the UK. J Ethn Migr Stud 46(1):87–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1524291

Nguyen TT, Tran T, Nguyen LMT, Pham TV, Nguyen TPT, Pham HT (2020) Influence of ethnic culture in choosing the learning type of ethnic minorities: evidence from Northwest of Vietnam. Cogent Soc Sci 6(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2020.1753487

North DC (1991) Institutions. J Econ Perspect 5(1):97–112. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.5.1.97

Patias N, Rowe F, Arribas-Bel D (2023) Local urban attributes defining ethnically segregated areas across English cities: a multilevel approach. Cities 132:103967. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2022.103967

Peijen R, Wilthagen T (2023) Tackling ethnic minority disadvantage: the differential impact of short-term and long-term-oriented strategies on subsequent job matches and sustainable employment. Soc Policy Soc 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474746422000756

Tegegne MA (2015) Immigrants’ social capital and labor market performance: the effect of social ties on earnings and occupational prestige. Soc Sci Q 96(5):1396–1410

The State Council of the PRC (2005) regional ethnic autonomy. https://www.gov.cn/guoqing/2005-09/13/content_2582468.htm. Accessed 29 Sept 2024

Thomeer MB, Moody MD, Yahirun J (2023) Racial and ethnic disparities in mental health and mental health care during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities 10(2):961–976. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-022-01284-9

Tosun S (2022) Perception of fairness in household labor division: the effect of gender values, relationship dynamics, and culture. Society 59(4):426–440. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12115-022-00661-8

Zhou Z (2013) Sixteen lectures on the political geography of Chinese history. Zhonghua Book Company, Beijing

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Rui Zhou: Conceptualization, methodology, writing—original draft preparation. Xinyue Yu, Tao Wang, and Hao Feng: Data curation and methodology. Shaoyang Zhao: Supervision, writing—reviewing and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This research does not involve ethical issues that require approval from an Institutional Review Board (IRB). The study is based on a survey conducted among participants without collecting sensitive personal data or performing any interventions that would necessitate ethical oversight. The research adhered to standard academic practices, including ensuring the anonymity and confidentiality of respondents, in compliance with applicable guidelines and regulations. We confirm that the study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in [e.g., the Declaration of Helsinki or relevant local/national regulations, if applicable]. If needed, we are prepared to provide additional information or documentation clarifying the ethical considerations of this study.

Informed consent

This study is based on secondary data from the 2015 national 1% population sampling survey, a large-scale, representative survey conducted by the National Bureau of Statistics of China. As the data were collected and anonymized by the official survey organizers prior to our access, no additional interventions or interactions with participants were conducted as part of this study. Therefore, informed consent from participants for this specific research was not applicable. We confirm that the use of this data adheres to all relevant guidelines and regulations, and the anonymity and confidentiality of the participants were strictly maintained throughout our analysis.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, R., Yu, X., Wang, T. et al. Does culture influence female labor force participation of ethnic minorities? Evidence from a large-scale survey on both sides of the ethnic boundary in China. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 457 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04678-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04678-2