Abstract

Women’s financial independence is essential for fostering equality. Despite recent progress in narrowing the gender gap in access to finance, a notable imbalance persists, even in advanced economies. Exploring the roots and persistence of the wealth gap demands a long-term perspective. However, limited access to historical data hampers such investigations. We have assembled a unique dataset encompassing over 34,000 shareholders from Spanish commercial banks (1918-1948) to scrutinize how women capitalized on investment opportunities. Our findings reinforce the theory that women’s involvement in financial markets reflects a deeper, long-term phenomenon linked with institutional evolution and modernization. The data provide evidence that women viewed investment in stocks as a means to attain wellbeing and that they embraced financial risk, guided by profitability. Family networks significantly enhanced women’s portfolios, empowering their financial agency. The paper underscores the significance of accounting for historical and cultural elements in understanding women’s investment practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Despite progress in narrowing the gender gap in finances, imbalance persists, even in advanced economies (Skonieczna and Castellano 2020). Financial literature has drawn attention to the fact that women have fewer investments than men, due to demand-side factors (Roy and Patro 2022). Cultural norms also influence women’s financial exclusion, which might explain why such gaps persist in developed countries despite legal equality (Fonseca and Lord 2020). Stereotypes, and collective attitudes regarding women’s ability to manage finances, directly influence their confidence when performing financial tasks (Tinghög et al. 2021). When studies require participants to assess their own financial knowledge, women tend to rate their own knowledge lower than men (Bucher‐Koenen et al. 2017; Hospido, Iriberri, and Machelett 2024), although other studies also show that women’s performance is not worse than men in similar conditions (Lind et al. 2020). The widespread belief that women are financially less capable than men deprives society of vital opportunities for growth and development (Skonieczna and Castellano, 2020). This assumption is a stark reminder that, at some point in the past, this was unfailingly true: society perceives women as having inferior financial acumen in comparison to men (Baeckström 2024). However, historical research can furnish robust evidence that dispels the notion that women are inherently less capable investors. Exploring historical contexts may help to comprehend the roots of the gender wealth gap and fully grasp its persistence over time. There is a consistent line of research that shows that women did invest in financial assets at the dawn of industrialization, seeking the highest return on their investments. These early female investors were not merely anecdotal as a group, but formed a relative minority of the investor class (Haan 2022; Rutterford 2021).

From a long-term perspective, highlighting the rationality of pioneering women’s financial decisions is significant because female financial choices continue to be scrutinized today, revealing the enduring presence of cultural biases (Baeckström 2024). Evidence from the past can undermine the current gender gap by demonstrating that, contrary to cultural bias about past women’s inability to invest, their decisions were as good as those made by men. They invested rationally and sought high returns on their investments. The previous reflection serves as the foundational question for our research: How did historical events impact women’s involvement in financial markets? In order to test our main question, we base our study on a unique database for three Spanish commercial banks from the first half of 20th century. Our research provides evidence supporting the long-term nature of the feminization of capital, and the increase in the number of women purchasing assets, despite external shocks. It also delves into the characteristics of their investments, establishing a comparison with men in similar circumstances. The analysis shows that both men and women typically entered the financial markets through family connections. Another noteworthy finding is that women made their investment decisions no differently than men, guided by profitability and assuming risk.

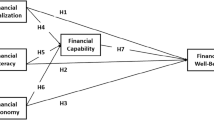

Our research provides a robust quantitative analysis that allows for testing a triad of hypotheses widely supported by the theoretical framework:

-

1.

Hypothesis 1. Female shareholders were part of a historical trend. The proliferation of women shareholders is part of a historical trend, not a temporary phenomenon. Financial assets reflected the spread of financial wealth throughout society, as part of modernization.

-

2.

Hypothesis 2. Family supported female shareholders providing access to shares. Women and men had access to shares alongside their family network. Trusted family members continued to be the ones who introduced other relatives to the purchase of financial assets.

-

3.

Hypothesis 3. Women’s behavior as investors was driven by profitability. An analysis of identical portfolios held by women and men reveals no major differences attributable to risk aversion and that the main motivation to invest in shares was profitability.

Past evidence reminds us that history does not advance continuously in a linear or cumulative manner. Situations considered a novelty today may be echoes of something that occurred in the past but was later forgotten by society. Reclaiming the legacy of female financial actions can be crucial to breaking social stereotypes that devaluate women’s financial actions. In pursuit of this ultimate aim, the structure of the article is as follows. The second section provides a theoretical framework and a review of the literature on female shareholders in a historical perspective, highlighting the connections with financial literature. The third section shows the data and a necessary historical background to contextualize the case study. The next section details the methodology. The fifth section shows the main descriptive results of the paper, tests the hypotheses and discusses the impact in the literature. Questioning on women’s financial decisions today demonstrates the persistence of cultural biases and the ignorance that women have been buying financial assets since their inception. Final remarks conclude the paper.

Review of the literature and theoretical framework

Research on women investors with a historical perspective is intimately related to the theoretical background of women and finance. To provide a state-of-the-art, we have carried out a literature review through the Web of Science (WoS) database, summarized in Supplementary Material I.

From an initial selection of 2331 WoS items, 197 duplicates were eliminated. The total titles for the scrutiny were 2194. Due the limited results of the automatic selection by keywords through titles—“history” and “century”—, we opted for manual reading and screening of all titles. In a few cases we checked the abstract. The final selection was 43 titles. From that total, we excluded three items: two book reviews and a call for an award grant. Therefore, the total number of references to consider was 40 works. These systematic searches in databases have clear limitations, because they can leave relevant works out of the scope of choice: books, and especially early studies that did not have an explicit focus on the existence of women investors, but did draw attention to their existence as shareholders and subscribers to public credit from the outset (Dickson, 1967).

Historical studies make a substantial contribution to the debate on investment behavior in financial markets by providing data and evidence. Supported by previous generalist works, a few British scholars began to theorize that the presence of women investors had been more relevant than conventionally recognized. These studies were published in the 21st century, once the research on women and finances had already been established. The first theoretical contribution was, therefore, to point out the presence of past women investors beyond the anecdotal. Women were active agents in the early financial markets of the nascent capitalism. Very few names have been investigated as examples of female agency and success (Todd 2010; Froide 2016; Freeman, Pearson, and Taylor 2009). Even fewer were those that stood out for their fraudulent activity, such as Sarah Howe and her Ponzi scheme in the late 1870s (Robb 2012). Nevertheless, a number of studies revealed the large numbers of female owners of financial assets that already existed in the 17th century (Clark 1982; Ewen, 2019), and in the 18th century (Carlos, Maguire, and Neal 2008; 2006; Laurence 2006; Redding 2020), as well as their proliferation in the 19th century, when industrialization needed to raise more capital to undertake its developments (Haan 2022; Maltby and Rutterford 2006; Froide 2016; Laurence 2008). The exclusion of women from governance roles and corporate boards, despite being significant shareholders, increased their absence from written documents (Hernández-Nicolás and Martínez Rodríguez 2020). As a result, they were unfortunately erased from history and collective memory, leading to social invisibility (Henry 2018). Apart from the literature available for English-speaking regions, the narratives on women investors are limited, as is the case in Italy (Licini 2011; Fregulia 2015), Argentina (Elena 2022), Germany (Lehmann-Hasemeyer and Neumayer 2022; Rosenhaft 2008), or Spain (Martínez-Rodríguez 2021; Martínez-Rodríguez and Lopez-Gomez 2023; Fynn-Paul 2015).

Importantly, all these works focus not only on unveiling the presence of women, where they previously had been ignored, but on giving meaning to their presence. The dominant literature points to the fact that the progressive feminization of some financial markets was due to institutional changes, which allowed more women, particularly married women, to make investment decisions about their wealth (Rutterford 2021; Rutterford and Maltby 2006; Turner 2009).

Regarding the characterization of female investors, the first attribute noted that women were independent investors. The archival source for these studies used to be asset ownership records, so the proxy to determine women’s agency is whether women buy shares jointly or individually. Autonomy has emerged as the dominant theory, and authors have superimposed on the traditional narrative that women lack on professional networks to access assets jointly as men do, to one linked to gender equity (Fleming et al. 2024a; 2024b), and women independence (Acheson et al. 2021). Family networks have also been an important formula to access and increase personal wealth. Studies have theorized how the family has been the way to allow women to access financial assets (Khan 2022). Laws and customs related to inheritance were pivotal for women’s financial inclusion in Spain (Martínez-Rodríguez and Lopez-Gomez 2023). In Scotland, female investors often operated within familial frameworks and local networks (Acheson and Turner 2011a; Acheson, Campbell, and Turner 2017).

Another attribute crucial in the debate is on risk aversion. It remains as a key topic in the finance literature which has evolved as more scientific evidence has become available (Dash and Mishra 2024). Whereas early seminal articles argued if women were risk-averse (Jianakoplos and Bernasek 1998), more recent research attempts to decipher why such difference persist when evaluating an investment (Charness and Gneezy 2012). Financial literacy, family responsibility, and cultural patterns all contribute to the fact that financial knowledge assumed by women is lower than that assumed by men. Historical studies challenged the notion of passive or ignorant female investors, highlighting strategies that range from conservative to high-risk ventures. To begin with, the paternalism about low financial status was already present in the 18th and 19th centuries, when contemporaries lamented that women would be victims of scams (Robb 2006). Research pointed out that women investors were overrepresented in blue chip and less risky assets (Green et al. 2009; Rutterford et al. 2011). Another important finding was the preference for local investments, which would reduce information asymmetry (Acheson and Turner 2011b; Rutterford, Sotiropoulos, and van Lieshout 2017; Sotiropoulos and Rutterford 2018). Since these women, like many of the men, were upper class, they tended to seek investments that provided them with passive income in an economy where the need for cash was a constant (Acheson, Campbell, and Turner 2015). Scholars also observe the existence of women with diversified portfolios despite volatile conditions, investing in mining (Fleming et al. 2024b), or sailing vessels (Doe 2010). Previous comments analyze the main theoretical axes of research on women investors in a historical perspective, clearly connected with the general literature. Although other questions are relevant, our study will review these three questions based on a particular case.

Framework and data

The context: situation of the Spanish women for the studied period

During the first third of the 20th century, Spain witnessed a process of modernization and social transformation, which favored the increase of female shareholders. The population increased from 18.5 million in 1900 to 23.5 million in 1930. Birth rates declined from 33.8‰ to 28.2‰, while the marriage rate increased to 7.4‰ in 1930. The rise in life expectancy was also notable: from 34.8 years in 1900 to 50 years in 1930 (Otero Carvajal 2017). Urbanization promoted a more independent model of womanhood, depicted in the media as an icon of modernity and change (Otero Carvajal and Rodríguez Martín 2022). Employment opportunities for women increased in areas with diversified, urban economies and high capacity to attract workers, such as Barcelona or Madrid (Hernández-Nicolás and Martínez-Rodríguez 2019; Martínez-Rodríguez 2020). Women began to work as office workers or clerks, breaking away from traditional gender roles and occupying workplaces that integrated women from different social class (Nielfa Cristobal 2022). Education experienced significant advancements during this period, and women accessed to the university starting in 1910. All those changes fostered the blossom of a new educated and professional gender identity, although their presence remained largely symbolic (Montero 2011). Upper middle-class women with qualified jobs and formal education were the fewer. Our women shareholders were, as men shareholders, privileged members of the society trying to allocate their savings and wealth in profitable investment.

During this period, no significant legislative change occurred that could justify the increase in female shareholders. This is a datum to consider because the turning point in share ownership in the British context was the Married Women’s Property Act (1870), which gave married women the right to control personal property (Combs 2005). In Spain women’s rights concerning access to property had been well-established for centuries. Spanish women had—at least on paper—equal access to inheritances from their parents, just like their brothers (Gete-Alonso and Solé Resina 2014). Considering this fact, interpreting the concept of female agency through the individual ownership of shares lacks relevance, as it was the social custom for shares to be registered under the name of their rightful owner.

The data: explanation and description

The archival sources for this paper are the lists of Annual Shareholders’ Meeting of three banks in the first half of the 20th century: Banco de La Coruña (1918-1922), Banco Hispano Americano (1922-1935), and Banco de Irún (1929-1948). (We shorten the names of the banks to Banco Coruña and Banco Irún). Archives are intricate records of history. Raw historical data is not systematically collected, much less processed (Coller, Helms Mills, and Mills 2016). It is part of the researcher’s process to search for it and, if it is found, to select and process it. Scholars have reflected on the contents found in the archives, their randomness and representativeness (Antoniette Burton 2005). This database is the result of an exhaustive archival search aimed to find representative data on women investors. Banks have historically played a crucial role in financial stability and economic growth, which makes the case more relevant (Leventis, Dimitropoulos, and Owusu-Ansah 2013). Additionally, women’s shares in the past offer a relevant narrative to explain the current gender gap in access to finance. Unlike real estate, which offers a visible tangible benefit, the purchase of shares provides returns in the form of dividends and capital appreciation, both of them abstract concepts that are subject to uncertainty.

During the first third of the 20th century in Spain banking system experienced significant growth and expansion (Martín-Aceña 2012). Shares slowly turned into a more-reliable financial instrument that was accessible to upper-class savers (Martínez Soto and Hoyo Aparicio 2018). The nominal value of each share (for each of the banks) was 500 pesetas – approximately 1430 euros in 2025 using the historic standard of livingFootnote 1–. The decision to use these three commercial banks to create a database was based on several criteria. Banco Hispano Americano was one of the leading commercial banks at national level. In 1913, it held the largest bank deposit in the country; in the 1920s and 1930s, it was the leading bank (De Inclán, Serrano García, and Calleja Fernández 2019). The choice of regional bank and local bank was based on the limited archival options. We assembled a database of 34,121 shareholders: 29,631 shareholders from Banco Hispano Americano; 2331 shareholders from Banco Coruña; and 2159 shareholders from Banco Irún.

The lists of Spanish shareholders furnished information about the shareholders’ full names, the number of shares they owned, and their place of residence. The ownership of each share corresponded to individuals, groups or entities. We exclusively analyzed the dominant category of individuals. Archival sources did not provide systematic information on marital status. For these Spanish lists, marital status was not as relevant a factor for identifying women as it was for British lists. In Spain, both women and men are identified by two surnames—first the paternal surname, followed by the maternal surname—throughout their lives, which allows us to obtain information on kinship relationships.

The analysis of shareholders in Spanish banks reveals a noteworthy increase in female shareholders. In Banco Coruña (1918-1922), the proportion of women among the bank’s shareholders increased from around 12% in 1918 to over 15% in 1922. The total number of shareholders grew by 3.24 percentage points, the percentage of male shareholders decreased by 7.07 percentage points from 1918 to 1922. This illustrates a changing ownership landscape for the bank. The Banco Hispano Americano (1922-1935) exhibited a significantly higher percentage of female shareholders compared to Banco Coruña. Certainly, there is an issue of scale due to the extensive coverage of a national bank compared with a regional one. Also, Banco Hispano Americano had a distinct urban profile from the 1920s onwards. The extensive network of branches was attributed to the institution’s prestige and financial stability (García Ruiz and Tortella 2007). The proportion of women increased from 36.65% in 1922 to 46.03% in 1935. In contrast, the percentage of men experienced a decline, from 61.11% to 51.79% over the same period.

There was also a notable increase in the percentage of women shareholders in Banco Irún. Despite the challenging circumstances of the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939), and the subsequent post-war era with fewer rights and less freedom for women, the percentage of female shareholders rose from 12.57% in 1929 to 28.36% in 1948, while the percentage of male shareholders fell from 68.86% to 60.45%. Women gained ground among the shareholders, even amidst external shocks and economic uncertainty, indicating a deeper transformation of the economic and social landscape. However, the number of male shareholders in Banco Irún consistently remained at around 60% throughout the analyzed period. This pattern aligns more closely with Banco Coruña than Banco Hispano Americano, where the gender distribution among shareholders was more evenly balanced. Overall, the data reveal a progressive increase in the presence of female shareholders in Spanish banks during the first half of the 20th century (Fig. 1). Supplementary Material II examines structural changes in the shareholding composition over different time periods using kernel density estimation. Supplementary Material III provides further explanation on the data.

Table 1 provides a comprehensive analysis of shareholders. At Banco Coruña, the average percentage of female shareholders during the analyzed period was 13.63%, compared to 72.65% for male shareholders. Banco Hispano Americano (1922–1935) showed a higher female presence, with women comprising 40.15% of shareholders and men 57.58%. Notably, women held 28.53% of shares, significantly more than the 6.14% at Banco Coruña. The feminization of the shareholders in Banco Hispano Americano mirrored the longevity of multigenerational family shareholders in a bank with extensive geographical coverage in Spain. Meanwhile the shareholder figures of Banco Coruña showed a prevalence of women since its foundation.

In Banco Irún, the average percentage of female shareholders was 21.11%. Women held approximately 16.20% of the total shares, surpassing the percentage of Banco Coruña but falling short of Banco Hispano Americano’s figures. Men held around 65.38% of the shares, which was lower than Banco Coruña but higher than Banco Hispano Americano. The data indicates a significant transformation in the shareholder composition of Spanish commercial banks during the analyzed period (1918–1948), marked by the increasing presence of women.

Methodology

The descriptive data indicates the increasing presence of women in commercial banks during the first half of the 20th century in Spain. We applied several econometric techniques to gain a deeper and more robust understanding of the patterns identified in the database. In time series, spectral analysis is a suitable method for distinguishing between the cyclical component and the deterministic or long-term trend within a single variable. This decomposition of a series into short-term and long-term components can be achieved using various approaches; the Hodrick-Prescott (HP) filter is the most well-known.

The HP filter is a mathematical tool used to separate the cyclical component from the trend component in a time series. The HP filter is applied in various areas of economics and finance. Firstly, it helps to identify the phases of business cycles, such as expansions and contractions. Secondly, it assists policymakers in understanding long-term economic trends as separate from short-term fluctuations influenced by policy changes. Lastly, it is used to study trends and cycles in financial data, such as stock prices or interest rates. Our methodology was to adapt the HP filter to identify the trend in the percentage of female shareholders in each of the three banks examined. This allowed us to determine whether the presence of women was merely a result of the favorable economic conditions, or if the trend was solid and persisted even after the civil war and the dictatorship.

The filter decomposes a time series \({y}_{t}\) into two components, a trend component \({\tau }_{t}\), which represents the underlying movement or trend in the data, and a cyclical component \({c}_{t}\), which captures short-term fluctuations or deviations from the trend. The series \({y}_{t}\) is therefore as follows:

The HP filter achieves this decomposition by solving the following minimization problem:

where \({y}_{t}\) is the observed value of the time series at time \({t}\), \({\tau }_{t}\) is the trend component of the time series at time \(t\). In addition, \(\lambda\) is a smoothing parameter that determines the trade-off between the smoothness of the trend and the fit to the data. The first term in Eq. (2) measures how closely the trend component \({\tau }_{t}\) fits the observed data \({y}_{t}\). Minimizing this term ensures that the trend captures the general movement of the data. The rest of the Eq. (2), also called the smoothness penalty term, penalizes large changes in the trend component over time. The parameter \(\lambda\) controls the amount of penalty: higher values of \(\lambda\) result in smoother trends, while lower values allow for more flexibility and potential noise in the trend. The consensus of the literature and empirical evidence for financial data shows that the appropriate parameter value for annual data is 100. This value provides a good balance to maintain the smoothness of the trend while still adjusting to annual fluctuations.

Once the long-term trend in the percentage of female shareholders had been identified, we examined the factors that made it likely for a woman to become a shareholder in one of the three banks. We used the 34,121 records in our dataset and estimated various logit models with the characteristics that increase the likelihood of a woman being a shareholder. We used the following model for all three banks and all periods:

The dependent variable \({{FS}}_{i}\) is a binary variable that equals 1 if the shareholder is a woman and 0 otherwise. \({{NS}}_{i}\) is the number of shares each shareholder owns. \({{kinship}}_{i}\) is a binary variable that equals 1 if the shareholder has a family member in the bank. To determine kinship, we assumed that two or more shareholders were related if they shared the same surname. In Spain, individuals have two surnames: the first one is the first surname of the father, and the second one is the first surname of the mother. We considered two individuals were siblings when both surnames matched. This was a feasible assumption and it has been supported by the literature (Guinnane and Martínez-Rodríguez 2018; Martínez-Rodríguez and Lopez-Gomez 2023). Indeed, there is an underestimation of family ties, since it only considers one type of first-degree relatives. Previous works have already discussed the advantages and disadvantages of horizontal and direct kinship (siblings) as a result of parental inheritance. All models include an intercept, \(\alpha\) and the error term \({\varepsilon }_{i}\).

The use of spectral analysis combined with the estimation of logit models, along with descriptive analysis, may provide robust evidence that the feminization of bank shareholding was not a circumstantial phenomenon (Hypothesis 1). This approach may also help us to evaluate family support in accessing these financial assets (Hypothesis 2), and analyze whether the presence of women was merely symbolic or had economic significance (Hypothesis 3).

Results and Discussion

Female shareholders were part of a historical trend

Hypothesis 1: Female shareholders were part of a historical trend

Without repeating the arguments presented in the theoretical framework section, here we provide some additional support to probe Hypothesis 1. For the period 1800-1860 women’s wealth was of great importance to the British state (Green and Owens 2003). Far from being an anecdote, female shareholders became relevant in number, especially in institutions like banks (Newton and Cottrell 2006). They increased from 15% (1870-9) to 45.4% (1930-5) (Rutterford et al. 2011). Previous authors claim that legal changes were crucial for the increase in women shareholders in the United Kingdom during the 19th and early 20th centuries. The Married Women’s Property Acts of 1870 and 1882 granted married women rights over their own property, enabling them to invest directly, while single and widowed women were already able to operate bank accounts, acquire securities, and participate in corporate meetings (Rutterford and Maltby 2006; Green and Owens 2003). These reforms not only provided legal security for women but also created an inclusive investment environment, where their participation continued to grow (Rutterford 2021). During a historical phase when women did not have access to many of the vectors for social advancement available to men, the ownership of shares offered an attractive non-discriminatory dividend. Today, grey literature still praises the advances of women investors as if they were a novelty of modern times, ignoring the fact that there is a historical legacy (Blackrock 2023).

In the Spanish case, there was also a notable increase in the number of female shareholders for the studied period (1918-1948). Interestingly, this phenomenon was not accompanied by an institutional or legal shock that improved women’s rights. Significant milestones during the period, such as the right to vote in 1931, had little impact on the distribution of female shareholders in banks. Similarly, negative changes on women’s agency, such the National Catholicism of the Francoist period, failed to bring substantial changes to women’s investments, and the modest shifts observed in women’s representation closely parallel similar trends among male shareholders. The trend towards an increase in the number of female shareholders is undeniable. We applied the HP filter to identify the trend in the percentage of female shareholders, analyzing each bank individually. The results of the decomposition into cyclical and trend components are presented in Fig. 2a to d. For Banco Irún, we analyzed this variable by separating the sample into two periods: 1929-1935 (pre-Civil War) and 1940-1948 (post-Civil War). Each figure distinguishes three main components: the original series of the percentage of female shareholders (female shareholders), the long-term component (trend), and the cyclical component (cycle).

a Trend and cyclical component of the percentage of women shareholders. Banco Coruña (1918-1922). b Trend and cyclical component of the percentage of women shareholders. Banco Hispano Americano (1922–1935). c Trend and cyclical component of the percentage of women shareholders. Banco Irún (1929–1935). d Trend and cyclical component of the percentage of women shareholders. Banco Irún (1941–1948). Source: Own database. Note: For Fig. 2a to d the X-axis represents years, the main Y-axis shows the cyclical component (deviations of the percentage of women shareholders from the smoothed trend), and the secondary Y-axis displays the smoothed trend of the percentage of women shareholders over time. Both Y-axes are measured in percentages.

The long-term trend shows a constant rise in female shareholders in all three banks, and throughout the whole period. It is noteworthy that, even in adverse contexts – i.e., the Great Depression of 1929 (Fig. 2b and c) and the decade after the Spanish Civil War (Fig. 2d)—women achieved a greater presence in the financial markets. The cyclical component, which captures short-term fluctuations, reveals how specific economic and political events did temporarily affect women’s participation in the financial markets. The evolution of the cyclical term for Banco Hispano Americano differs significantly from the evolution of the series (Fig. 2b), while for the other two banks the cycle mimics the path of the series (Fig. 2a, c and d).

The results of the series decomposition demonstrate that the percentage of female shareholders exhibited a markedly upward long-term deterministic trend, even during the country’s most challenging years. Women’s investment was a persistent trend. These findings support Hypothesis 1 that female shareholding was a historical trend. Financial literature indicates that when more liquid forms of wealth appeared, as part of the contemporary development, women participated in it (Deere and Doss 2006). Even through periods of economic and political turmoil, the inclusion of women in financial markets was driven by fundamental shifts in societal attitudes and economic structures. Research related to the stock market in Spain for a similar period reveals that access to financial assets was not significantly disrupted by transient external factors (Battilossi, Houpt, and Verdickt 2022). Notably, the decline in the percentage of male shareholders during first half of the 20th century further reinforces the argument that financial assets were becoming more widely distributed across gender lines, suggesting a democratization of financial participation, as was predicted for England (Rutterford 2021).

Family empowered female shareholders

Hypothesis 2: Family-supported female shareholders providing access to shares

Who do investors trust when making investment decisions? Financial literature states that experienced investors place their confidence in data and professionals (Sarkar 2017). However, novel investors tend to trust someone within their close circle, often a family member with whom they share common interests and a strong sense of trust. Over one-third of investors rely on their family’s opinion when making investment decisions (Harasheh, Bouteska, and Manita 2024). From a historical perspective, the influence of family networks has been considered a prominent factor in explaining women’s inclusion in financial markets. Family played a pivotal role in American women’s investment decisions during the early industrialization period (Khan 2022). These personal networks reduced perceptions of risk, facilitating the mobilization of capital in ventures. For England, historical studies challenge the stereotype that women relied solely on male advisors for investment decisions, presenting evidence of cases where they took on the role of advisors to family members and acquaintances (Froide 2016). For Spain, a high number of shareholders had familial ties. Figure 3a to c demonstrate that kinship is particularly significant for Banco Irún and Banco Hispano Americano. These two banks consistently show more than 30% of shareholders related by kinship during most of the analyzed period, with Banco Hispano Americano reaching up to 40%. In contrast, Banco Coruña exhibited a percentage of 3.62% for women, while for male shareholders the percentage was 4.85%. For the smaller banks, Irún and Coruña, Fig. 3a demonstrates a trend with an increasing percentage of both male and female shareholders with familial ties within the bank. For women, Fig. 3b shows a similar upward pattern, with Banco Hispano Americano maintaining higher levels compared to the smaller banks. Figure 3c indicates that family support was also significant for men in the newer and smaller banks, but it was less relevant in Banco Hispano Americano.

a Percentage of shareholders related by kinship. Both women and men (1918–1948). b. Percentage of shareholders related by kinship. Female shareholders (1918–1948). c Percentage of shareholders related by kinship. Male shareholders (1918–1948). Source: Own database. Note: For Figs. 3a to c), we define kinship based on shareholders’ last names. If two shareholders share both last names, they are considered to have a kinship relationship, meaning they are family. For further details, see Section 2, Eq. (3).

To test whether kinship relationships foster the presence of women in banks, we employ logit models. In these models, the dependent variable (being a woman) is binary, taking the value 1 if the shareholder is female, and 0 otherwise. The explanatory variables include the number of shares owned and the kinship ties. Table 2 shows that, for Banco Coruña and Banco Hispano Americano, a higher number of shares is associated with a lower probability of being a female shareholder across all years analyzed. In the case of Banco Irún, this negative relationship is only significant in the late 1940s. Regarding kinship, its effect on female shareholding is significant and positive for Banco Coruña and Banco Hispano Americano, suggesting that women were more likely to appear as shareholders when linked to other shareholders through family ties. However, for Banco Irún, kinship does not exhibit a statistically significant effect in either period. This lack of significance might indicate a lagged rather than a contemporary family effect, which could be further examined through cross-correlation analysis between the percentage of female shareholders and the percentage of total shareholders related by kinship. Supplementary IV provides logit regression for each bank each year.

Cross-correlation measures the relationship between two time series at different lags. It helps to identify whether one time series has a lagged effect on another. Figure 4 presents the results of this analysis, separated into pre- and post-Civil War periods to determine whether this delayed relationship changes across these periods. Figure 4a and b show the results, confirming that the relationship between the percentage of family-related shareholders and the increase in female shareholders is indeed lagged.

a Cross-correlation between lags and leads of the percentage of female shareholders and the percentage of shareholders related by kinship: Banco Irún (1929–1935). b Cross-correlation between lags and leads of the percentage of female shareholders and the percentage of shareholders related by kinship: Banco Irún (1941–1948). Source: Own database. Note: In the cross-correlation figures, the X-axis represents the lags and leads (time periods forward or backward), while the Y-axis shows the correlation between the two variables for each lag or lead. The correlation value ranges from -1 to 1, indicating the strength of the relationship between the variables at each time point.

The cross-correlation between the percentage of female shareholders and the percentage of male and female shareholders with kinship relationships is positive and significant (passing above the black line set at \(\pm 0.8\)), whereas before it was not. This result may be explained by the time required to formalize the incorporation of new shareholders on the list following the receipt of an inheritance. Therefore, it can be inferred that family support remained crucial for the inclusion of women in the banks’ shareholding. Whether contemporaneous or lagged, all banks show a positive and significant relationship between family support and the presence of female shareholders.

The multiple dimensions of Hypothesis 2 demonstrate that family networks played a crucial role in enabling women to become shareholders, connecting with financial theory and other historical evidence. Our analysis shows clearly that the impact of family support may have varied significantly between institutions and over time. Considering our restrictive definition of family in the analysis, which only considers siblings, it is plausible that shareholders had other familial connections that our model has not detected, particularly those involving marriages and second-degree kinship. A more realistic definition of family may include both spouses holding shares and those widows who became shareholders after inheriting shares from their late husbands. The absence of this information prevents a systematic analysis of the marital status of women.

Women investors sought profit

Hypothesis 3: Women’s behavior as investors was driven by profitability

Purchasing financial products entails making decisions based on incomplete information, while assuming varying degrees of risk. As discussed in the state of the art, a vast body of current research—grounded in demographic profiles, surveys, and laboratory studies—aims to identify the degrees of risk aversion exhibited by men and women in various circumstances. The foundations of this literature were established by seminal papers that scientifically addressed the belief that women’s financial decisions were more risk-averse than men’s (Schubert et al. 1999; Jianakoplos and Bernasek 1998). To test Hypothesis 3, we compare men and women with identical portfolios to assess whether conclusions can be drawn about their investment decisions. We argue that if men held a particular portfolio—defined by the number of shares—guided by the rational decision to seek economic returns, women would do so as well. The portfolios for comparison had a maximum number of shares of 20, because in the banks of Irun and Coruña, no woman had a larger portfolio (in Banco Hispano Americano, women did have portfolios equivalent to those of the largest male shareholders, exceeding 1000).

Having 20 shares, an investment of 10,000 pesetas, was a more than respectable amount at that time—approximately 28,600 euros in 2025 using the historic standard of livingFootnote 2–In the case of feminized professions (school teachers and office workers), purchasing a single bank share represented between 12% and 20% of a person’s annual salary (Gaceta de Madrid 1925b; 1930a; 1924). Additionally, having a portfolio of around 20 shares implies more than three years of work for these individuals. In contrast, in more male-dominated professions, such as military general or full professor, purchasing one or even 20 shares represented a relatively lower value compared to their income, but still required a significant effort (Sabaté, Espuelas, and Herranz-Loncán 2022).

Table 3 pays attention to these portfolios with less than 20 shares. We assumed that the ownership of just a single share may have a symbolic value, guided by social prestige. It was only in Banco Coruña that there were more women than men in this position. In Banco Irún, no women held a single share, while 3.87% of the men did.

In Banco Coruña, a higher percentage of men owned fewer than 5 shares compared to women (27.34% for men vs. 6.29% for women). A similar pattern was observed for Banco Irún (12.38% for men vs. 4.30% for women). Conversely, Banco Hispano Americano exhibited almost no gender bias in this category (8.08% for men vs. 7.15% for women). For the tranche with fewer than 10 shares, Banco Coruña and Banco Irún reflected a gender bias that was not present in Banco Hispano Americano. The performance of portfolios with fewer than 20 shares varied: at Banco Coruña, the gender gap was very significant (53.37% for men vs. 11.37% for women), whereas at Banco Irún, the gender gap favored women (28.13% for women vs. 13.71% for men). In summary, women owning 1 to 5 shares did not constitute a significant percentage, whereas there was a greater presence of those holding at least 10. Women invested focusing on benefits, not on symbolic or social value.

Table 4 shows the variation in the percentage of small female shareholders (relative to the total number of female shareholders). The variation indicates the number of women holding fewer than 20 shares increased during all analyzed periods except for (1929-1933). Data from Banco Irún (1929-1933) relates to the early years of the bank and also to a dismal economic situation caused by the economic downturn of 1929. The percentage of women with fewer than 20 shares in the banks of Coruña and Hispano Americano grew at an average annual rate of 0.82% and 0.14%, respectively. In the post-war years, data from Banco Irún show that women with less than 20 shares continued to grow at an approximate average annual rate of 2.5%. The reading is less optimistic in the tranches with fewer shares. The percentage of women with fewer than 5 shares grew at a negative average rage, except for the period 1940 a 1948. For the female shareholders with less than 10 shares, there was a positive growth rate for the main part of the period (1922-1935, 1940-1948).

The variation growth rate for shareholders was positive for shareholders with fewer than 20 shares, but this was not the case for the groups with fewer than 5 or 10 shares. The outcome suggests that women with more extensive portfolios perceive a more favorable risk-reward relationship, maintaining or increasing their investments. Women with fewer than 20 shares, compared to the group with fewer to 10 or fewer than 5 shares, were more adventurous in diversification, and resilient to economic and market changes.

Conclusions

Past societies denied women the role of cultural mediators in the transmission of financial information and the negotiation of financial agreements on same level as men (Bolufer, Guinot-Ferri, and Blutrach 2024). Nevertheless, the reality was that the economy accepted investments without any reservations related to gender. Women’s financial legacy is a social value that must be reclaimed, highlighting the active involvement of women in finance, and by extension, in the economy.

Historical cases of women as holders of financial assets provide a significant incentive for further consideration. This paper illustrates, with a study case, how a country with a less prominent tradition as a champion of modernization can still be compared to Great Britain in explaining the modernization of women’s capital. Compared to some of the existing literature on the same topic, the primary strength of this paper lies in its quantitative approach and robustness of the results linked with a broader theory. The research is based on a database of 34,000 observations, encompassing three representative banks of the Spanish banking system, with capital divided into shares. The results section of the paper is built around three hypotheses that connect the historical case with three relevant questions of finance theory: the presence of women shareholders beyond anecdote; the role of family networks; and the pursuit of profitability as a proxy that breaks with the dominant social conception that women are risk-averse. The formulation of these hypotheses results from a detailed literature review.

Our results confirm the thesis that women capital and investment were not just anecdotal but relevant for the economy. Data analysis reveals a consistent and significant increase in female shareholding within Spanish commercial banks during the first half of the 20th century. This trend is characterized by a sustained upward trajectory over time, indicating a structural shift of female participation in the modernization of financial markets. The rise in female involvement persisted despite periods of instability, underscoring its foundation in profound societal and economic changes, as part of a historical trend. This legacy attests to the fact that women have been agents of change, and their memory must be vindicated in today’s financial world. A second result demonstrates that familial structures provided significant support in enabling women to participate actively in financial markets. Today, these strategies can be an effective recommendation for developing countries, to enhance the degree of female financial activity and agency. Our data also provides information that the family is also supportive to men in starting out in financial investments. This result applies to balance the gender stereotypes in terms of investments.

The next issue relates to the nature of the investment: to improve the profitability of an investment, a certain degree of risk and uncertainly is undeniable. Putting their wealth to work showed that women exhibited a rational behavior that sought benefits, as in the case of men. Comparing the same portfolios, both women and men assessed risk and maximized their investment holdings (number of shares) to obtain profitability. Historical legacy serves as an effective tool to bridge the financial gap that hinders economic and social growth and development. Aspects discussed in the paper link the historical analysis to key concepts in financial literature, such as female agency and family networks enabling access to financial assets. Our results may contribute to broadening and improving the international debate on how women invest and whether their investment behavior differs, or not, from that of men.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author. E-mail: susanamartinezr@um.es.

Notes

Average value as reported by ‘Measuring Worth’ for the year 1918.

https://www.measuringworth.com/calculators/spaincompare/relativevalue.php (accessed 11 January 2025).

Average value as reported by ‘Measuring Worth’ for the year 1918.

https://www.measuringworth.com/calculators/spaincompare/relativevalue.php (accessed 10 January 2025).

References

Acheson GG, Campbell G, Gallagher Á, Turner JD (2021) Independent Women: Investing in British Railways, 1870–1922. Econ Hist Rev 74(2):471–495. https://doi.org/10.1111/EHR.12968

Acheson GG, Campbell G, Turner JD (2015) Active Controllers or Wealthy Rentiers? Large Shareholders in Victorian Public Companies. Bus Hist Rev 89(4):661–691. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007680515001026

— (2017) Who Financed the Expansion of the Equity Market? Shareholder Clienteles in Victorian Britain. Business History 59(4): 607–637. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2016.1250744

Acheson GG, Turner JD (2011a) Investor Behaviour in a Nascent Capital Market: Scottish Bank Shareholders in the Nineteenth Century. Econ Hist Rev 64(1):188–213. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0289.2010.00524.x

— (2011b) Shareholder Liability, Risk Aversion, and Investment Returns in Nineteenth-Century British Banking. In Men, Women, and Money. Oxford University Press, p 207–227

Baeckström Y (2024) Gender and Finance. London, Routledge

Battilossi S, Houpt SO, Verdickt G (2022) Scuttle for Shelter: Flight-to-Safety and Political Uncertainty during the Spanish Second Republic. Eur Rev Econ Hist 26(3):423–447. https://doi.org/10.1093/ereh/heab022

Blackrock (2023) Lifting Global Growth by Investing in Women, Blackrock. https://www.blackrock.com/corporate/literature/whitepaper/lifting-global-growth-by-investing-in-women.pdf

Bolufer M, Guinot-Ferri L, Blutrach C (2024) Gender and Cultural Mediation in the Long Eighteenth Century. In M Bolufer, L Guinot-Ferri, C Blutrach (eds). New Transculturalisms, Cham: Springer International Publishing, p 1400–1800

Bucher‐Koenen T, Lusardi A, Alessie R, van Rooij M (2017) How Financially Literate Are Women? An Overview and New Insights. J Consum Aff 51(2):255–283. https://doi.org/10.1111/joca.12121

Burton A (2005) Archives Stories: Facts, Fictions, and the Writing of History. In A Burton (ed), Durham, Duke University Press, p 1–24

Carlos AM, Maguire K, Neal L (2006) Financial Acumen, Women Speculators, and the Royal African Company during the South Sea Bubble. Account, Bus Financ Hist 16(2):219–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585200600756241

— (2008) A Knavish People…’: London Jewry and the Stock Market during the South Sea Bubble. Business History 50(6): 728–748. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076790802420039

Charness G, Gneezy U (2012) Strong Evidence for Gender Differences in Risk Taking. J Econ Behav Organ 83(1):50–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JEBO.2011.06.007

Clark A (1982) Working Life of Women in the Seventeenth Century. Reprint. O. London, Routledge & Kegan Paul

Coller KE, Helms Mills J, Mills AJ (2016) The British Airways Heritage Collection: An Ethnographic ‘History. Bus Hist 58(4):547–570. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2015.1105218

Combs MB (2005) A Measure of Legal Independence: The 1870 Married Women’s Property Act and the Portfolio Allocations of British Wives. J Econ History. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022050705000392

Dash P, Mishra SK (2024) Investment Intentions and Financial Decisions of Women Investors: A Bibliometric Analysis for Future Research. Glob Bus Financ Rev 29(6):114–128. https://doi.org/10.17549/gbfr.2024.29.6.114

Deere CD, Doss CR (2006) The Gender Asset Gap: What Do We Know and Why Does It Matter? Femin Econ 12(1–2):1–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/13545700500508056

Dickson PGM (1967) The Financial Revolution in England: A Study in the Development of Public Credit, 1688-1756. London, MacMillan

De Inclán M, Serrano García E, Calleja Fernández A (2019) Guía de Archivos Históricos de La Banca En España. Serie: Pub. Madrid, Banco de España Eurosistema

Doe H (2010) Waiting for Her Ship to Come in? The Female Investor in Nineteenth‐century Sailing Vessels. Econ Hist Rev 63(1):85–106. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0289.2009.00496.x

Elena E (2022) Spinsters, Gamblers, and Friedrich Engels: The Social Worlds of Money and Expansionism in Argentina, 1860s–1900s. Hispanic Am Historical Rev 102(1):61–94. https://doi.org/10.1215/00182168-9497200

Ewen M (2019) Women investors and the Virginia Company in the Early seventeenth Century. Hist J 62(4):853–874. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0018246X19000037

Fleming G, Liu Zhangxin(Frank), Merrett D, Ville S (2024) Gender(Ed) Equity: The Growth of Female Shareholding in Australia, 1857–1937 Asia‐Pac Econ Hist Rev 64(3):291–314. https://doi.org/10.1111/aehr.12300

— (2024b) No Gold‐diggers Here: Women Investors in Colonial Australian Mining. Econ History Rev. https://doi.org/10.1111/ehr.13388

Fonseca R, Lord S (2020) Canadian Gender Gap in Financial Literacy: Confidence Matters. Hacienda Pública Española/Rev Public Econ 235(4):153–182

Freeman M, Pearson R, Taylor J (2009) Between Madam Bubble and Kitty Lorimer: Women Investors in British and Irish Stock Companies In A Laurence, J Maltby, J Rutterford (eds) Women and Their Money, 1700-1950: Essays on Women and Finance, London, Routledge, p 95–114

Fregulia JM (2015) Stories Worth Telling: Women as Business Owners and Investors in Early Modern Milan. Early Mod Women: Interdiscip J 10(1):122–130

Froide AM (2016) Silent Partners: Women as Public Investors during Britain’s Financial Revolution, 1690-1750. Oxford University Press

Fynn-Paul J (2015) Occupation, Family, and Inheritance in Fourteenth-Century Barcelona: A Socio-Economic Profile of One of Europe’s Earliest Investing Publics. Eur Hist Q 45(3):417–445. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265691415585975

Gaceta de Madrid (1924) Real Orden de 21 de Marzo de 1924 Por La Que Se Convoca Para Proveer Mediante Oposición Dos Plazas de Auxiliares de Administración de Primera Clase, Dotadas Con El Haber Nacional de 2500 Pesetas

— (1925b) Real Orden de 4 de Junio de 1925 Por La Que Nombra Profesora Numeraria de La Escuela Normal de Maestras a Doña Pilar Escribano Iglesias

— (1930a) Real Orden de 21 de Septiembre de 1930 Por La Que Se Convocan Para Proveer Mediante Oposición Plazas de Maestros y Maestras

García Ruiz JL, Tortella G (2007) How Strategy Determines Structure: The Organizational History of the Banco Hispano Americano and the Banco Central (1900-1992). Entreprises et Societes 48:29–42

Gete-Alonso MaríadelCarmen, Solé Resina J (2014) Mujer y Patrimonio (El Largo Peregrinaje Del Siglo de Las Luces a La Actualidad). Anuario de Derecho Civ 67(3):765–894

Green DR, Owens A (2003) Gentlewomanly Capitalism? Spinsters, Widows, and Wealth Holding in England and Wales, c. 1800–1860. Economic Hist Rev 56(3):510–536. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0289.2003.00260.x

Green DR, Owens A, Maltby J, Rutterford J (2009) Lives in the Balance? Gender, Age and Assets in Late-Nineteenth-Century England and Wales. Continuity Change 24(2):307–335. https://doi.org/10.1017/S026841600900719X

Guinnane TW, Martínez-Rodríguez S (2018) Instructions Not Included: Spain’s Sociedad de Responsabilidad Limitada, 1919–1936. Eur Rev Economic Hist 22(4):462–482. https://doi.org/10.1093/ereh/hey006

Haan SC (2022) Corporate Governance and the Feminization of Capital. Stanf Law Rev 74(3):515–602. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3740608

Harasheh M, Bouteska A, Manita R (2024) Investors’ Preferences for Sustainable Investments: Evidence from the U.S. Using an Experimental Approach. Econ Lett 234(January):111428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2023.111428

Henry N (2018) Women Investors in Fact. In Women, Literature and Finance in Victorian Britain. Cham: Springer International Publishing, p 29–51

Hernández Nicolás CM, Martínez Rodríguez S (2019) Guardando Un Legado, Acunando Un Futuro. Viuda En Las Sociedades Mercantiles En El Cambio de Siglo (1886-1919). Rev de Historia Ind 28(77):93–117. https://doi.org/10.1344/rhi.v28i77.28663

Hernández-Nicolás CM, Martínez-Rodríguez S (2020) Mirror, Bridge or Stone? Female Owners of Firms in Spain During the Second Half of the Long Nineteenth Century 337–360. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-33412-3_14

Hospido L, Iriberri N, Machelett M (2024) Gender Gaps in Financial Literacy: A Multi-Arm RCT to Break the Response Bias in Surveys. Documentos de Trabajo Del Banco de España, Madrid, p 2401

Jianakoplos NA, Bernasek A (1998) Are Women More Risk Averse? Econ Inq 36(4):620–630. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-7295.1998.tb01740.x

Khan BZ (2022) Related Investing: Family Networks, Gender, and Shareholding in Antebellum New England Corporations. Bus Hist Rev 96(3):487–524. https://doi.org/10.1017/S000768052200071X

Laurence A (2006) Women Investors, ‘That Nasty South Sea Affair’ and the Rage to Speculate in Early Eighteenth-Century England. Account, Bus Financ Hist 16(2):245–264. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585200600756274

— (2008) Women, Banks and the Securities Market in the Early Eighteenth Century England. In A Laurence, J Maltby, J Rutterford. Women and Their Money, 1700-1950: Essays on Women and Finance, London, Routledge

Lehmann-Hasemeyer S, Neumayer A (2022) The Limits of Control: Corporate Ownership and Control of German Joint-Stock Firms, 1869–1945. Financ Hist Rev 29(2):152–197. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0968565022000075

Leventis S, Dimitropoulos P, Owusu-Ansah S (2013) Corporate Governance and Accounting Conservatism: Evidence from the Banking Industry. Corp Gov: Int Rev 21(3):264–286. https://doi.org/10.1111/corg.12015

Licini S (2011) Assessing Female Wealth in Nineteenth Century Milan, Italy. Account Hist 16(1):35–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/1032373210389591

Lind T, Ahmed A, Skagerlund K, Strömbäck C, Västfjäll D, Tinghög G (2020) Competence, Confidence, and Gender: The Role of Objective and Subjective Financial Knowledge in Household Finance. J Fam Econ Issues 41(4):626–638. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-020-09678-9

Maltby J, Rutterford J (2006) She Possessed Her Own Fortune’: Women Investors from the Late Nineteenth Century to the Early Twentieth Century. Bus Hist 48(2):220–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076790600576818

Martín-Aceña P (2012) The Spanish Banking System from 1900 to 1975 In The Spanish Financial System: Growth and Development since 1900, London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, p 99–144

Martínez Soto ÁP, Hoyo Aparicio A (2018) El Ahorro Minorista de La Banca Privada Española, 1900-1935. Revista de Historia Industrial 28 (75 SE-Artículos)

Martínez-Rodríguez S (2020) Mistresses of Company Capital: Female Partners in Multi-Owner Firms, Spain (1886–1936). Bus Hist 62(8):1373–1394. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2018.1551364

— (2021) Female Shareholders of Private Spanish Banks (1920–1948). A First Approach. Quaderni Storici 61(1): 37–60. https://doi.org/10.1408/101555

Martínez-Rodríguez S, Lopez-Gomez L (2023) Gender Differential and Financial Inclusion: Women Shareholders of Banco Hispano Americano in Spain (1922–35). Femin Econ 29(3):225–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2023.2213709

Montero M (2011) First Steps towards Equality: Spanish Women in Higher Education (1910–1936). Int J Iber Stud 24(1):17–33. https://doi.org/10.1386/ijis.24.1.17_1

Newton L, Cottrell PL (2006) Female Investors in the First English and Welsh Commercial Joint-Stock Banks. Account, Bus Financ Hist 16(2):315–340. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585200600756316

Nielfa Cristobal G (2022) La Larga Marcha de Las Mujeres Hacia Las Oficinas. In LE Otero Carvajal and N Rodríguez Martín, La Mujer Moderna. Sociedad Urbana y Transformación Social En España, 1900-1936, Madrid, La Catarata, p 126–145

Otero Carvajal LE (2017) La Sociedad Urbana y La Irrupción de La Modernidad En España, 1900-1936. Cuad de Historia Contemp ánea 38(Especial):255–283. https://doi.org/10.5209/CHCO.53678

Otero Carvajal LE, Rodríguez Martín N (2022) La Mujer Moderna. Sociedad Urbana y Transformación Social En España, 1900-1936. Madrid, La Catarata

Pons MÁ (2012) The Main Reforms of the Spanish Financial System. In The Spanish Financial System Growth and Development Since 1900. London, p 71–98

Popp A, Fellman S (2017) Writing Business History: Creating Narratives. Bus Hist 59(8):1242–1260. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2016.1250742

Redding S (2020) African Women Farmers in the Eastern Cape of South Africa, 1875–1930: State Policies and Spiritual Vulnerabilities. 433–453. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-33412-3_18

Robb G (2006) Women and White-Collar Crime. Br J Criminol 46(6):1058–1072. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azl069

— (2012) Depicting a Female Fraud: Sarah Howe and the Boston Women’s Bank. Nineteenth-Century Contexts 34(5): 445–459. https://doi.org/10.1080/08905495.2012.738086

Rosenhaft E (2008) “Women Investors and Financial Knowledge in Eighteenth-Century Germany.” In A Laurence, J Maltby, J Rutterford (eds), Women and Their Money 1700–1950. Essays on Women and Finance. London, Routledge & Kegan Paul, p 59–71

Roy P, Patro B (2022) Financial Inclusion of Women and Gender Gap in Access to Finance: A Systematic Literature Review. Vis: J Bus Perspect 26(3):282–299. https://doi.org/10.1177/09722629221104205

Rutterford J (2021) The Forgotten Investors: Women Investors in England and Wales 1870 to 1935. Quaderni Storici. 1:13–35. https://doi.org/10.1408/101554

Rutterford J, Green DR, Maltby J, Owens A (2011) Who Comprised the Nation of Shareholders? Gender and Investment in Great Britain, c. 1870–1935. 64(1):157–187. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1468-0289.2010.00539.x

Rutterford J, Maltby J (2006) The Widow, the Clergyman and the Reckless’: 1 Women Investors in England, 1830-1914. Femin Econ 12(1–2):111–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/13545700500508288

— (2007) The Nesting Instinct’: Women and Investment Risk in a Historical Context. Account History 12(3): 305–327. https://doi.org/10.1177/1032373207079035

Rutterford J, Sotiropoulos DP, van Lieshout C (2017) Individual Investors and Local Bias in the UK, 1870–1935. Econ Hist Rev 70(4):1291–1320. https://doi.org/10.1111/ehr.12482

Sabaté O, Espuelas S, Herranz-Loncán A (2022) Military Wages and Coups D´état in Spain (1850–1915): The Use of Public Spending as a Coup-Proofing Strategy. Rev de Historia Econ ómica / J Iber Lat Am Econ Hist 40(2):205–241. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0212610920000270

Sarkar AK (2017) Analysis of Individual Investors Behaviour of Stock Market. Int J Trend Sci Res Dev ume-1(Issue-5):922–931. https://doi.org/10.31142/ijtsrd2394

Schubert R, Brown M, Gysler M, Brachinger HW (1999) Financial Decision-Making: Are Women Really More Risk Averse? Am Econ Rev 89(2):381–385. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.89.2.381

Skonieczna A, Castellano L (2020) Gender Smart Financing. Investing In and With Women: Opportunities for Europe. Discussion Paper, p 129

Sotiropoulos DP, Rutterford J (2018) Individual Investors and Portfolio Diversification in Late Victorian Britain: How Diversified Were Victorian Financial Portfolios? J Econ Hist 78(2):435–471. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022050718000207

Tinghög G, Ahmed A, Barrafrem K, Lind T, Skagerlund K, Västfjäll D (2021) Gender Differences in Financial Literacy: The Role of Stereotype Threat. J Econ Behav Organ 192(December):405–416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2021.10.015

Todd BJ (2010) Property and a Woman’s Place in Restoration London. Women’s Hist Rev 19(2):181–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/09612021003633895

Turner JD (2009) Wider Share Ownership?: Investors in English and Welsh Bank Shares in the Nineteenth Century. Econ Hist Rev 62(SUPPL.1):167–192. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1468-0289.2009.00477.X

Acknowledgements

This publication was supported by: the Region of Murcia (Spain) through the Regional Program for the Promotion of Scientific and Technical Research of Excellence (Action Plan 2022) of the Seneca Foundation—Science and Technology Agency of the Region of Murcia under the grant [Project 21947/PI/22]; the European Union-Next Generation EU under the grant ‘Aid for requalification in the Spanish University System’ Visiting fellow at IDEGA-University of Santiago de Compostela (academic year 2023–2024); Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities [PID2023-149319NB-I00]; the Project I+D+i PID2023-149319NB-I00 FINCH-Firms, Investors and Uncertainty in History, funded by MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033/.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Susana Martínez-Rodríguez contributed to the conceptualization of the study, data curation, formal analysis, writing of all versions, and funding acquisition. Laura Lopez-Gomez contributed to the conceptualization of the study, data curation, formal analysis, and writing of all versions.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

was not required as the study did not involve human participants.

Informed consent

was not obtained since the study does not involve human participants or their data.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Martínez-Rodríguez, S., Lopez-Gomez, L. How did historical trends impact women’s involvement in financial markets? Evidence from women shareholders in Spain (1918-1948). Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 595 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04828-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04828-6