Abstract

Fraud susceptibility is a complex characteristic influenced by a combination of cognitive functioning, loneliness, and impulsivity. Research has shown that individuals with weaker cognitive functioning, higher levels of loneliness, and higher levels of impulsivity are more likely to be victims of fraud. The purpose of this study was to examine the positive relationship between cognitive failure and gullibility and to examine whether loneliness and impulsivity mediate this relationship. A total of 842 valid questionnaires including the Chinese version of Gullibility Scale, the Cognitive Failure Scale, the Simplified Barratt Impulsivity Scale, and the Loneliness Scale were collected from college students. Our results showed that (1) there were significant positive correlations among gullibility, cognitive failure, loneliness, and impulsivity; (2) loneliness and impulsivity played a chain-mediated role between cognitive failure and gullibility.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nowadays we live in a networked society with cloud computing, the problem of college students being cheated has become a serious public social problem (Cross et al. 2018; Shadel and Pak, 2011). For college students, the experience of fraud not only causes irreparable financial loss, but also severe psychological distress (e.g., shame, self-blame, depression, anxiety) (Kircanski et al. 2018; Pratt et al. 2010). Researches have showed that some groups or individuals are more susceptible to fraud, and even some victims are at risk of repeated fraud (Crocker et al. 2017). Gullible and non-gullible people may differ in certain characteristics that make individuals more likely to make wrong decisions or responses when faced with fraudulent information (Rotter, 1967; Yamagishi et al. 1999). This relatively stable trait possessed by gullible individuals is called gullibility (Fischer et al. 2013; Teunisse et al. 2020). In view of the fact that fraud has seriously harmed society as well as the physical and mental health of college students, we considered gullibility as one of the risk factors for college students to be cheated (Forgas and East, 2008; Schwarz and Clore, 1983). Assessing the risk of fraud not only has theoretical significance but also helps the management department to formulate relevant policies to help college students reduce the risk of fraud and improve the ability to prevent fraud.

Studies have found that poor cognitive ability may be linked to poor financial decision-making (Li et al. 2014), meaning that cognition is strongly associated with individuals’ gullibility (Forgas and East, 2008). Cognitive failure is a cognitive-based error in the performance of a simple task that an individual would normally be able to perform competently, resulting in a behavioral fault (Broadbent et al. 1982), such as forgetting something that needs to be done right away. Cognitive failure reflects a disruption of the normal process of cognitive functioning and is a phenomenon resulting from errors in the execution of cognitive functions (Wickens et al. 2008). The main cognitive mechanisms leading to cognitive failure include persistent attention deficit, scattered attention, poor inhibition function, reduced working memory capacity, and executive control failure (Carrigan and Barkus, 2016). This pervasive behavior will cause many adverse effects on people’s learning, work, and physical and mental health (Carrigan and Barkus, 2016). High cognitive functions can help us effectively identify fraudulent information and prevent the occurrence of being defrauded (Stewart et al. 2019). Individuals with poor cognitive functioning may not have the necessary cognitive processing abilities to recognize deception (Acierno et al. 2010), which could explain why some people are repeatedly deceived. Evidence from cognitive neurology suggested that vmPFC-impaired groups are more likely to be gullible with misleading advertisements compared to control groups, implying that damage to brain regions associated with cognitive executive functioning contributes to elevated susceptibility to fraud (Asp et al. 2012). These existing findings confirmed that cognitive factors may play an important role in gullibility. Therefore, the current study chose cognitive failure as the variable to explore the effect of cognitive function on gullibility. Based on previous studies (Forgas and East, 2008; Schwarz and Clore, 1983), we proposed Hypothesis 1: Cognitive failure has a positive predictive effect on gullibility.

Negative emotions may lead to poorer decision making due to the fact that people cannot easily recognize deceptive information when they are deceived (George and Dane, 2016). Previous studies on gullibility have mainly focused on the elderly (James et al. 2014; Shao et al. 2019; Spreng et al. 2016), who are at risk of being deceived due to high levels of loneliness (Xing et al. 2020). The results indicated that the loneliness scores of elderly people who had been deceived were significantly higher than those without deceived experience (Beach et al. 2018; Carstensen and Mikels, 2005; Zhou et al. 2021), suggesting that loneliness significantly predicts people’s gullibility. Loneliness refers to an adverse affective experience that arises when an individual perceives that the actual level of interaction experienced in interpersonal relationships does not meet expectations (Weiss, 1975). College students’ performance in interpersonal interactions has gradually declined, ang they have shown more experiences of loneliness, which has seriously affected their mental health (Moeller and Seehuus, 2019; So and Fiori, 2022). People with higher loneliness may have poor social interaction skills, find it difficult to identify the intention of the object they are interacting with, which leads to higher gullibility (Wang et al. 2012). Cognitive functioning affects how people process and manage their emotions (Yates et al. 2013). Individuals with cognitive failure are more likely to have negative emotions, while it is difficult to change such mood through cognitive reappraisal (McRae, 2016). Thus, when people experience cognitive failure, persistent negative states may increase individuals’ loneliness. What’s more, problems such as decreased working memory capacity and inhibitory control deficits, as caused by cognitive failure, can predict people’s loneliness to a certain extent (Windle et al. 2021; Zhong et al. 2017). These evidences suggest that cognitive failure is a risk factor for loneliness.

In addition to loneliness, high impulsivity may lead to high rates of fraud victimization (Holtfreter et al. 2008; Van Wilsem, 2013). Impulsivity is the tendency of individuals to react quickly and without assessment of consequences when faced with internal or external stimuli, often ignoring the potential negative effects on themselves or others (Moeller et al. 2001). Decision making is a complex process that requires people to accurately and adequately identify and process information to make a reasonable decision. Therefore, highly impulsive individuals are more susceptible to deception (Yang et al. 2019). An important characteristic of impulsive individuals is to satisfy their immediate needs while ignoring long-term consequences, so they may underestimate the risks involved when confronted with the temptation of a cheater (Holtfreter et al. 2008). At the same time, impulsive individuals are emotionally vulnerable to pressure exerted by scammers, which in turn impinges on their ability to make rational decisions (Modic and Lea, 2012). Impulsivity is influenced by people’s cognitive control, which means that cognitive failure may increase people’s impulsive behavior (Morean et al. 2014). People with cognitive failure exhibit persistent attention deficit, poor inhibition, and so on. These factors may result in an individual’s inability to effectively maintain attention to important information, making it easier to make impulsive decisions. In summary, this study proposes hypothesis 2: Loneliness and impulsivity mediate the relationship between cognitive failure and gullibility.

To sum up, this study constructed a chain mediation model for the gullibility of college students, aiming to determine the association between cognitive failure and gullibility among college students. Furthermore, we examined the mediating role of loneliness and impulsivity in the relationship between cognitive failure and gullibility using a path analysis. This will help to reveal the mechanism of cognitive failure, loneliness and impulsivity on college students’ gullibility, which in turn will provide insights for effectively reducing the risk of gullibility among college students.

Methods

Participants

Through the online questionnaire survey platform, we distributed questionnaires to college students nationwide, 1205 questionnaires were distributed, and 363 invalid questionnaires that did not pass the two polygraph tests (e.g., You need to choose 5 for this question) or answer regularly (participants answer questions in a fixed pattern in the questionnaire, such as always choosing the same option regardless of the content of the question) were excluded. The final dataset came from 842 questionnaires and were useable for subsequent data analysis, exceeding the ratio of 1:10, with an effective recovery rate of 69.87%. The demographic characteristics of the subjects are presented in Table 1.

There are three possible reasons for the low efficiency of the questionnaire collection: firstly, the online questionnaire format is easily interfered by other information in the mobile phones, which leaded to the lack of seriousness of some of the subjects; secondly, the online questionnaire took a long time, part of the subjects cannot adhere to a high level of concentration; thirdly, part of the subjects may be resistant to the research topic, which may result in a negative response.

Measures

The Chinese version of Gullibility Scale

The Gullibility Scale, created by Teunisse in 2019, consists of 12 items that include two dimensions of persuasion and susceptibility (Teunisse et al. 2020). The Scale uses a seven-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree, 7 = Strongly Agree). The higher scores indicate the higher gullibility. Teunisse’s gullibility scale has been tested on college students and community residents, which showed good reliability and validity. The Cronbach’s α coefficient of the total scale was 0.91, and the Cronbach’s α coefficients of persuasion and sensitivity were 0.87 and 0.86 respectively (Teunisse et al. 2020). In this study, the revised Chinese version of the College Students’ Gullibility Scale was used, including two dimensions of persuasion and sensitivity, with a total of 12 items. Items 2, 9 and 11 of the Chinese versions were reverse scored. In the current study, the Cronbach’s alpha is 0.90.

Cognitive Failures Questionnaire

The Cognitive Failures Questionnaire is a unidimensional structured questionnaire created by Broadbent, which contains three dimensions of attention, memory and action function, with a total of 25 items (Broadbent et al. 1982). The Scale is scored by five points (1 = never, 5 = always). On the premise that the CFQ copyright agency issued a public use statement, Zhou et al. (2016) revised the original scale and formed a Chinese version of the Cognitive failure Questionnaire, which had good reliability and validity. In the current study, the Cronbach’s alpha is 0.93.

Brief Barratt Impulsiveness Scale

The simple Barratt impulsivity scale has 8 items, including two dimensions of self-control and impulsive behavior (Morean et al. 2014). A Likert level 4 score is used (1 = never, 4 = often), and items 1, 4, 5, and 6 are reverse scored, with the higher the total score, the more impulsive. This study was authorized by Morean who is the reviser of the original scale, Luo et al. (2020) revised the Chinese version in 2020, which has good reliability and validity. In the current study, the Cronbach’s alpha is 0.78.

UCLA Loneliness Scale (ULS-8)

The ULS-8 loneliness Questionnaire was revised by Hays and Dimatteo, which consisted of 8 items with a single dimension (Hays and DiMatteo, 1987). The scale uses a four-point Likert scale (1 = never, 4 = often). Items 3 and 6 are reverse scored, and the higher the total score, the stronger the loneliness. Liu and Gu (2012) were authorized to revise the Chinese version of the ULS-8 loneliness Questionnaire among college students. In the current study, the Cronbach’s alpha is 0.86.

Data analysis

We first conducted descriptive analyses of the demographic characteristics among the college students by using SPSS 26.0. Then, Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients were used to evaluate the association between cognitive failure, loneliness, impulsivity and gullibility. Finally, to examine whether loneliness and impulsivity mediated the relationship between cognitive failure and gullibility, we conducted a mediation analysis with the SPSS PROCESS macro, version 3.4 (model 6).

Results

Common method bias or variance

CMB/CMV is a concern because using data tainted with this issue can lead to false correlations and internal consistencies among the studied constructs. To eliminate the common method deviation caused by the questionnaire investigation, the Harman single-factor test was performed. The results of factor analysis found that there were 9 factors with characteristic roots were greater than 1, and the first common factor explained 27.75% (less than 40%) of the total variation (Hosen et al. 2021). Hence, there were no obvious common method biases. However, single factor test is no longer sufficiently persuasive and acceptable. Consequently, the common latent factor (CLF) test was executed, wherein all the items from models with or without CLF were compared to the standardized regression weights, whose differences were less than the 0.20 threshold (Serrano-Archimi et al. 2018). As a whole, the statistical approach reaffirms the procedural approach to establish that CMB/CMV is not a serious concern in this study.

Correlations analysis

Descriptive statistical analysis was used to find out the overall situation of cognitive failure, loneliness, and impulsivity variables of college students. Correlation analysis was used to explore the relationship between college students’ gullibility and cognitive failure, loneliness, and impulsivity. The results showed that college students’ gullibility was significantly correlated with cognitive failure, loneliness, and impulsivity (p < 0.001), and the correlation coefficients were 0.482, 0.397, and 0.437 respectively (see Table 2).

Regression analysis

In order to further investigate the relationship between gullibility and cognitive failure, loneliness, and impulsivity of college students, this study adopted the confirmation method for regression analysis. We conducted multiple regression analysis with cognitive failure, loneliness, and impulsivity as predictor variables, age and gender as control variables, and gullibility as the dependent variable. Table 3 showed that cognitive failure, loneliness, and impulsivity could positively predict gullibility, and the VIF inflation factor was between 1.7–2, indicating that there was no multi-collinearity between variables.

Mediation effect analysis

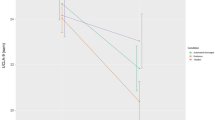

The results of correlation analysis showed that gullibility, cognitive failure, loneliness, and impulsivity were significantly correlated, suggesting that mediation effect test could be conducted. Regression analysis showed that cognitive failure, loneliness, and impulsivity could significantly positively predict gullibility, and mediation analysis could further explore the interaction mechanism among variables. Model 6 of SPSS plug-in PROCESS was used, with cognitive failure as the independent variable, gullibility as the dependent variable, loneliness and impulsivity as intermediate chain variables, gender, age as the control variables. As shown in Tables 4 and 5, analyses of total indirect effects indicated that loneliness and impulsivity served as partial mediating function in the relation between cognitive failure and gullibility. The mediating effect accounted for 43.36% of the total effect. Meanwhile, when tested separately, three mediating paths were significant. The specific paths are presented in Fig. 1. These results supported Hypothesis 1: Cognitive failure can positively predict gullibility, and Hypothesis 2: Loneliness and impulsivity mediate the relationship between cognitive failure and gullibility.

Discussion

This study revealed the internal mechanism of cognitive failure on gullibility among college students; at the same time, we aimed to estimate the mediating effects of loneliness and impulsivity. The results showed that cognitive failure affected gullibility both directly and indirectly via loneliness and impulsivity. Furthermore, loneliness and impulsivity partially mediated the effects of cognitive failure on gullibility. Specifically, cognitive failure was associated with more loneliness, more loneliness positively predicted impulsivity, and increased impulsivity predicted increased gullibility.

The role of cognition on gullibility has been extensively studied by researchers (Grilli et al. 2020; Wright and Marett, 2010), and the current study examined the predictive effect of cognition on gullibility of college students from the perspective of cognitive failure. The results show that, consistent with previous studies, cognitive failure had a positive predictive effect on gullibility of college students, reaffirming that complex, higher-order cognitive functions can actively recognize, resist, or avoid gullible behaviors (Castle et al. 2012; Scheibe et al. 2014). The dual-processing theory of decision-making points out that both heuristic decision based on intuition and analytical decision based on rationality exist in an individual’s decision-making system (Chaiken, 1980). Heuristic decision with higher speed of processing is based on experience and intuition, taking up fewer cognitive resources. In contrast, analytical decision with lower speed of processing relies more on rationality, which consumes more cognitive resources (De Neys, 2006). Individuals with cognitive failure exhibit characteristics such as an inability to allocate attentional resources effectively and poorer executive functioning (Carrigan and Barkus, 2016). In the face of fraudulent information, more attentional resources as well as the mobilization of cognitive resources can help people identify harmful information as much as possible and reduce the risk of being cheated. What’s more, high gullibility is often thought to be associated with low cognitive demand and a highly intuitive cognitive style, resulting in insensitivity to untrustworthy cues (McKnight and Chervany, 2001). Individuals with frequent cognitive failure make decisions based on information and situations provided by scammers often tend to use heuristic decision with fewer cognitive resources. Intuitive thinking reduces college students’ ability to detect scams and increases the likelihood of accepting information uncritically, indicating that more cognitive failure positively predicts greater gullibility.

In our study, it was found that cognitive failure may lead to more loneliness among college students, which predicted more gullibility. Unlike the loneliness experienced by older adults, fragmented relationships and less social activities after entering college may make college students more likely to experience loneliness, especially negative loneliness (Peplau and Perlman, 1982). Neural studies have shown that individuals with high loneliness may be associated with deficits in the inhibitory function of the ventral attentional network (VAN) (Cacioppo et al. 2014). At the same time, lonely individuals are often distracted and have difficulty in focusing their attention, which means that high-loneliness individuals are unable to concentrate on the task at hand (Hadlington, 2015). This could be an indication that cognitive failure positively affects loneliness. Moreover, individuals with high loneliness tend to be egotistical and uninformed in their decision-making process. As a result, they often fall victim to deception by being lured into making decisions alone by fraudsters. What’s more, in conjunction with potential victims being unaccompanied, fraudsters may provide them with emotional companionship or emotional accompaniment (Acierno et al. 2010; Lichtenberg et al. 2013). This may further stimulate the potential victim’s impulse to make wrong decisions (Hakim et al. 2021; Vishwanath, 2015). Impulsive individuals lack a prudent thought process when confronted with a scam and make decisions without risk identification.

Based on the impulsive dual-process model, impulsivity is divided into affective impulsivity and cognitive impulsivity (Harden and Tucker-Drob, 2011). On the one hand, People’s emotional impulsivity is strongly driven by emotional factors, which is mainly influenced by the emotional system such as ventral striatum, ventromedial prefrontal cortex (VMPFC). This bottom-up automated processing needs no intentional guidance and less cognitive resources. On the other hand, cognitive impulsivity is modulated by the cognitive control system composed of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (LPFC) and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), which requires a large number of cognitive resources (Cui et al. 2022; McClure and Bickel, 2014). Studies have shown that individuals with high loneliness are prone to negative emotions, and these negative emotions may lead people to be more impulsive in their decision-making process without thinking (Lichtenberg et al. 2013). In other words, the lonelier people have stronger emotional needs, which makes them more impulsive than those with lower loneliness. In addition, individuals with cognitive failure inherently have deficits of cognitive control, which makes it difficult for them to inhibit their inappropriate, hasty impulses (Hadlington, 2015). This suggests that cognitive failure is a factor that affects individual impulsivity. Studies into the gullibility of online scams found that gullibility may be a result of high impulsivity (Chen et al. 2017; Nolte et al. 2021). Individuals with high impulsivity do not have sufficient psychological strength to overcome impulsivity and are more prone to failures of self-control and being more gullible. These evidences supported the mediating role of loneliness and impulsivity between cognitive failure and gullibility among college students, as well as the positive predictive relationship between the variables.

However, there are some limitations to the current study. First, the cross-sectional approach makes it impossible to infer causality. Future longitudinal studies are essential to confirm the predictive role of loneliness and impulsivity in mediating the association between cognitive failure and gullibility among college students. Moreover, we will consider obtaining data from multiple sources, for example, we could use neuroimaging technology to obtain more accurate findings. Second, other confounding factors, such as family situation, social support, and personality factors, were not explored in the current study. Future studies can continue to explore these aspects to provide a new perspective for reducing the gullibility of college students.

Conclusion

In summary, our study found that loneliness and impulsivity had a mediating effect on the relationship between cognitive failure and gullibility. These findings highlight the importance of early intervention among college students with cognitive failure, especially those with high levels of loneliness and impulsivity. Therefore, it is important that universities proactively identify students with cognitive failure and take steps to help support them from an early stage. In this way, it can help lower the gullibility of college students and decrease the range of psychological problems or physical injuries caused by gullibility.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Acierno R, Hernandez MA, Amstadter AB et al. (2010) Prevalence and Correlates of Emotional, Physical, Sexual, and Financial Abuse and Potential Neglect in the United States: The National Elder Mistreatment Study. Am J Public Health 100:292–297. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.163089

Asp E, Manzel K, Koestner B et al (2012) A Neuropsychological Test of Belief and Doubt: Damage to Ventromedial Prefrontal Cortex Increases Credulity for Misleading Advertising. Front Neurosci 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2012.00100

Beach SR, Schulz R, Sneed R (2018) Associations Between Social Support, Social Networks, and Financial Exploitation in Older Adults. J Appl Gerontol 37:990–1011. https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464816642584

Broadbent DE, Cooper PF, FitzGerald P et al. (1982) The Cognitive Failures Questionnaire (CFQ) and its correlates. Br J Clin Psychol 21:1–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8260.1982.tb01421.x

Cacioppo S, Capitanio JP, Cacioppo JT (2014) Toward a neurology of loneliness. Psychol Bull 140:1464–1504. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037618

Carrigan N, Barkus E (2016) A systematic review of cognitive failures in daily life: Healthy populations. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 63:29–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.01.010

Carstensen LL, Mikels JA (2005) At the Intersection of Emotion and Cognition: Aging and the Positivity Effect. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 14:117–121. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00348.x

Castle E, Eisenberger NI, Seeman TE et al. (2012) Neural and behavioral bases of age differences in perceptions of trust. Proc Natl Acad Sci 109:20848–20852. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1218518109

Chaiken S (1980) Heuristic versus systematic information processing and the use of source versus message cues in persuasion. J Pers Soc Psychol 39:752–766. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.39.5.752

Chen H, Beaudoin CE, Hong T (2017) Securing online privacy: An empirical test on Internet scam victimization, online privacy concerns, and privacy protection behaviors. Comput Hum Behav 70:291–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.01.003

Crocker R, Webb S, Garner S et al (2017) The Impact of Organised Crime in Local Communities. The Police Foundation London

Cross C, Dragiewicz M, Richards K (2018) Understanding Romance Fraud: Insights From Domestic Violence Research. Br J Criminol 58:1303–1322. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azy005

Cui L, Ye M, Sun L et al. (2022) Common and distinct neural correlates of intertemporal and risky decision-making: Meta-analytical evidence for the dual-system theory. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 141:104851. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2022.104851

De Neys W (2006) Automatic–Heuristic and Executive–Analytic Processing during Reasoning: Chronometric and Dual-Task Considerations. Q J Exp Psychol 59:1070–1100. https://doi.org/10.1080/02724980543000123

Fischer P, Lea SEG, Evans KM (2013) Why do individuals respond to fraudulent scam communications and lose money? The psychological determinants of scam compliance. J Appl Soc Psychol 43:2060–2072. https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12158

Forgas JP, East R (2008) On being happy and gullible: Mood effects on skepticism and the detection of deception. J Exp Soc Psychol 44:1362–1367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2008.04.010

George JM, Dane E (2016) Affect, emotion, and decision making. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 136:47–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2016.06.004

Grilli MD, McVeigh KS, Hakim ZM et al. (2020) Is This Phishing? Older Age Is Associated With Greater Difficulty Discriminating Between Safe and Malicious Emails. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 76:1711–1715. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbaa228

Hadlington LJ (2015) Cognitive failures in daily life: Exploring the link with Internet addiction and problematic mobile phone use. Comput Hum Behav 51:75–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.04.036

Hakim ZM, Ebner NC, Oliveira DS et al. (2021) The Phishing Email Suspicion Test (PEST) a lab-based task for evaluating the cognitive mechanisms of phishing detection. Behav Res Methods 53:1342–1352. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-020-01495-0

Harden KP, Tucker-Drob EM (2011) Individual Differences in the Development of Sensation Seeking and Impulsivity During Adolescence: Further Evidence for a Dual Systems Model. Dev Psychol 47:739–746. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023279

Hays R, DiMatteo MR (1987) A Short-Form Measure of Loneliness. J Pers Assess 51:69–81. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa5101_6

Holtfreter K, Reisig MD, Pratt TC (2008) Low Self-Control, Routine Activities, and Fraud Victimization. Criminology 46:189–220. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.2008.00101.x

Hosen M, Ogbeibu S, Giridharan B et al. (2021) Individual motivation and social media influence on student knowledge sharing and learning performance: Evidence from an emerging economy. Comput Educ 172:104262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2021.104262

James BD, Boyle PA, Bennett DA (2014) Correlates of Susceptibility to Scams in Older Adults Without Dementia. J Elder Abuse Negl 26:107–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/08946566.2013.821809

Kircanski K, Notthoff N, DeLiema M et al. (2018) Emotional Arousal May Increase Susceptibility to Fraud in Older and Younger Adults. Psychol Aging 33:325. https://doi.org/10.1037/pag0000228

Li L, Li A, Hao B et al. (2014) Predicting Active Users’ Personality Based on Micro-Blogging Behaviors. PLoS ONE 9:e84997. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0084997

Lichtenberg PA, Stickney L, Paulson D (2013) Is Psychological Vulnerability Related to the Experience of Fraud in Older Adults? Clin Gerontol 36:132–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317115.2012.749323

Liu Y, Gu CH (2012) Revision of Loneliness Questionnaire for college students (uls-8). Shandong High Educ 29:40–44

Luo T, Chen MY, Ouyang FY et al. (2020) Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the simplified Barratt impulsivity scale. Chin J Clin Psychol 28:1199–1201+1280. https://doi.org/10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2020.06.025

McClure SM, Bickel WK (2014) A dual‐systems perspective on addiction: contributions from neuroimaging and cognitive training. Ann. N Y Acad Sci 1327:62–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.12561

McKnight DH, Chervany NL (2001) What Trust Means in E-Commerce Customer Relationships: An Interdisciplinary Conceptual Typology. Int J Electron Commer 6:35–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/10864415.2001.11044235

McRae K (2016) Cognitive emotion regulation: a review of theory and scientific findings. Curr Opin Behav Sci Neuroscience of education 10:119–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2016.06.004

Modic D, Lea SEG (2012) How Neurotic are Scam Victims, Really? The Big Five and Internet Scams. SSRN Electron J https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2448130

Moeller FG, Barratt ES, Dougherty DM et al. (2001) Psychiatric Aspects of Impulsivity. Am J Psychiatry 158:1783–1793. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.158.11.1783

Moeller RW, Seehuus M (2019) Loneliness as a mediator for college students’ social skills and experiences of depression and anxiety. J Adolesc 73:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.03.006

Morean ME, DeMartini KS, Leeman RF et al. (2014) Psychometrically improved, abbreviated versions of three classic measures of impulsivity and self-control. Psychol Assess 26:1003–1020. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000003

Nolte J, Hanoch Y, Wood S et al. (2021) Susceptibility to COVID-19 Scams: The Roles of Age, Individual Difference Measures, and Scam-Related Perceptions. Front Psychol 12:789883. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.789883

Peplau LA, Perlman D (1982) Loneliness: A source book of current theory, research, and therapy

Pratt TC, Holtfreter K, Reisig MD (2010) Routine Online Activity and Internet Fraud Targeting: Extending the Generality of Routine Activity Theory. J Res Crime Delinquency 47:267–296. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022427810365903

Rotter JB (1967) A new scale for the measurement of interpersonal trust. J Pers 35:651–665. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1967.tb01454.x

Scheibe S, Notthoff N, Menkin J et al. (2014) Forewarning Reduces Fraud Susceptibility in Vulnerable Consumers. Basic Appl Soc Psychol 36:272–279. https://doi.org/10.1080/01973533.2014.903844

Schwarz N, Clore GL (1983) Mood, Misattribution, and Judgments of Weil-Being: Informative and Directive Functions of Affective States. J Pers Soc Psychol 45:213–523. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.45.3.513

Serrano-Archimi C, Reynaud E, Yasin HM et al. (2018) How Perceived Corporate Social Responsibility Affects Employee Cynicism: The Mediating Role of Organizational Trust. J Bus Ethics 151:907–921. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-3882-6

Shadel D, Pak K (2011) AARP Foundation national fraud victim study. AARP, Washington, DC

Shao J, Zhang Q, Ren Y et al. (2019) Why are older adults victims of fraud? Current knowledge and prospects regarding older adults’ vulnerability to fraud. J Elder Abuse Negl 31:225–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/08946566.2019.1625842

So C, Fiori K (2022) Attachment anxiety and loneliness during the first-year of college: Self-esteem and social support as mediators. Personal Individ Differ 187:111405. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.111405

Spreng RN, Karlawish J, Marson DC (2016) Cognitive, social, and neural determinants of diminished decision-making and financial exploitation risk in aging and dementia: A review and new model. J Elder Abuse Negl 28:320–344. https://doi.org/10.1080/08946566.2016.1237918

Stewart SLK, Wright C, Atherton C (2019) Deception Detection and Truth Detection Are Dependent on Different Cognitive and Emotional Traits: An Investigation of Emotional Intelligence, Theory of Mind, and Attention. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 45:794–807. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167218796795

Teunisse AK, Case TI, Fitness J et al. (2020) I Should Have Known Better: Development of a Self-Report Measure of Gullibility. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 46:408–423. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167219858641

Van Wilsem J (2013) “Bought it, but Never Got it” Assessing Risk Factors for Online Consumer Fraud Victimization. Eur Sociol Rev 29:168–178. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcr053

Vishwanath A (2015) Examining the Distinct Antecedents of E-Mail Habits and its Influence on the Outcomes of a Phishing Attack. J Comput-Mediat Commun 20:570–584. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12126

Wang J, Zhu R, Shiv B (2012) The Lonely Consumer: Loner or Conformer? J Consum Res 38:1116–1128. https://doi.org/10.1086/661552

Weiss R (1975) Loneliness: The experience of emotional and social isolation. MIT press

Wickens CM, Toplak ME, Wiesenthal DL (2008) Cognitive failures as predictors of driving errors, lapses, and violations. Accid Anal Prev 40:1223–1233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2008.01.006

Windle G, Hoare Z, Woods B et al. (2021) A longitudinal exploration of mental health resilience, cognitive impairment and loneliness. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 36:1020–1028. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.5504

Wright R, Marett K (2010) The Influence of Experiential and Dispositional Factors in Phishing: An Empirical Investigation of the Deceived. J Manag Inf Syst 27:273–303. https://doi.org/10.2753/MIS0742-1222270111

Xing T, Sun F, Wang K et al. (2020) Vulnerability to fraud among Chinese older adults: do personality traits and loneliness matter? J Elder Abuse Negl 32:46–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/08946566.2020.1731042

Yamagishi T, Kikuchi M, Kosugi M (1999) Trust, Gullibility, and Social Intelligence. Asian J Soc Psychol 2:145–161. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-839X.00030

Yang H, Shao JJ, Zhang QH et al. (2019) Mediating Role of Security and Perceived Control on the Relationship between Fear of Aging and Older Adults’ Vulnerability to Fraud. Chin J Clin Psychol 27:1036–1040. https://doi.org/10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2019.05.037

Yates JA, Clare L, Woods RT (2013) Mild cognitive impairment and mood: a systematic review. Rev Clin Gerontol 23:317–356. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959259813000129

Zhong BL, Chen SL, Tu X et al. (2017) Loneliness and Cognitive Function in Older Adults: Findings From the Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey. J Gerontol Ser B-Psychol Sci Soc Sci 72:120–128. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbw037

Zhou W, Mou Z, Hong Z et al. (2021) Gaining or losing wisdom: Developmental trends in theory of mind in old age. Curr Psychol 40:4673–4683. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00394-8

Zhou Y, Chen JZ, Liu Y et al. (2016) Validity and Reliability of the Cognitive Failures Questionnaire in Chinese College Students. Chin. J Clin Psychol 24:438–443. https://doi.org/10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2016.03.013

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Chongqing Social Science Planning and Cultivation Project (2020PY61) and General Project of Chongqing Natural Science Foundation (CSTB2024NSCQ-MSX1101).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xue Du was responsible for validation, supervision, and writing—review and editing the draft. Jian Liang and Xue Du were responsible for the formal analysis and writing of the original draft preparation. Jian Liang was responsible for the investigation of the study. Xiaoyi Chen was responsible for data curation. Xue Du was responsible for the conceptualization and resources. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article includes human participants, and the study has been reported and approved by the Ethic Committee for Scientific Research School of Educational Sciences, Chongqing Normal University on 15th May 2021. Approve number is CNU-PSY-202105-089. Data collections were performed following the guidelines and regulations of the Declaration of Helsinki (2013).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants. The anonymity of the participants was always guaranteed, and the information obtained was kept in total confidentiality and used only for research purposes. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants on December 13, 2022.

Consent for publication

Consent for publication was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Du, X., Liang, J. & Chen, X. The relationship between cognitive failure and gullibility: loneliness and impulsivity as chain mediators. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1435 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04855-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04855-3