Abstract

Despite the growing integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into human society, a significant gap remains in understanding how AI can use its database-driven imagination to enhance urban planning and aesthetics effectively. This study explores ChatGPT-4o’s potential in generating future urban designs by incorporating human evaluations. Using a mixed-methods design, the study identified key indicators for evaluating AI-generated urban design images and then applied Importance-Performance Analysis (IPA) to measure participants’ evaluations of these indicators. Results showed that creativity was the most critical indicator needing improvement, while technological sense received high performance. Surprisingly, indicators like traffic rationality, environmental greening, public space utilization and cultural representation were deemed less important. These findings suggest that participants prefer AI to focus more on bold, imaginative aspects. This study constructs a framework for evaluating AI-generated urban design images and offers valuable insights for improving AI applications in urban planning and image generation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Large language models, equipped with powerful natural language processing capabilities, have demonstrated impressive applications across diverse fields, highlighting their potential as valuable assistive tools (Oermann and Kondziolka, 2023). By transforming text descriptions into visual outputs, these models represent a significant advancement in AI’s capacity to interpret and visualize abstract concepts (Driessen et al. 2024, Jang et al. 2024, Riemer and Peter 2024, Vemprala et al. 2024). Since their inception, large language models have been applied extensively in areas such as education, healthcare, and software development (Xue et al. 2023, Hu et al. 2024, Vemprala et al. 2024). Research shows that large language models can generate illustrative images from text descriptions, aiding human creativity in art and design (Lu et al. 2023). For example, DALL-E, built on a transformer architecture, generates highly detailed images, showcasing AI’s creative potential in design (Ali et al. 2024), while Midjourney enables users to explore imaginative visual scenes (Javan and Mostaghni, 2024). Building on these developments, ChatGPT-4o incorporates multimodal functionality, enabling it to generate images of futuristic urban landscapes from specific text prompts, showcasing unique potential in urban planning and design (Fu, 2024).

ChatGPT-4o’s image generation capability relies on an extensive database and robust computational capacity, enabling it to produce complex future city images from textual instructions. ChatGPT-4o processes large volumes of textual and visual data, with its database covering a broad range of urban design elements (Peng et al. 2023, Caprotti et al. 2024). The high quality of this data directly impacts the model’s ability to generate detailed, accurate images (Driessen et al. 2024). Additionally, supported by deep learning algorithms, ChatGPT-4o’s generation process includes multi-layered language comprehension, image analysis, and cross-modal integration (Wang et al. 2024). Leveraging efficient deep learning algorithms and computational power, ChatGPT-4o rapidly processes and integrates detailed data, converting textual instructions into concrete visualizations of future cities (Cugurullo et al. 2024). This functionality not only enhances creativity in urban planning but also provides visual representations of future cities, supporting human aesthetic evaluation and design feedback.

Although artificial intelligence has made significant strides in technical fields like data analysis and predictive modelling, its potential as a creative tool in urban planning remains underexplored. Current research primarily focuses on AI’s strengths in data processing and efficiency optimization (Oermann and Kondziolka, 2023, Osco et al. 2023, Hu et al. 2024), with limited exploration of its role in creating innovative designs and visualizing future urban landscapes. Specifically, structured methods for evaluating AI-generated city images from a human perspective are lacking. This gap hinders a deeper understanding of AI’s impact on creative design and underscores the need to develop systematic frameworks for analysing and providing feedback on the aesthetic and functional qualities of AI-generated urban designs.

Literature review

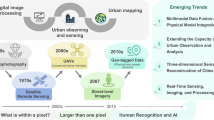

Image generation of ChatGPT

Since its inception, ChatGPT has evolved and improved continuously; however, ongoing research remains essential to address its limitations and to ensure effective application across diverse fields. Initially recognized for its text generation capabilities, ChatGPT lacked image generation functionality at launch (Floridi and Chiriatti, 2020). The latest version, ChatGPT-4o (GPT-4 Omni), introduced image generation, marking a significant advancement in large language models (LLMs) and demonstrating enhanced capabilities across language, vision, audio, and multimodal tasks (Zhu et al. 2024). These models have revolutionized AI-generated art and image creation, sparking public interest and discussions regarding their impact on sectors such as the arts (Oermann and Kondziolka, 2023). Despite these advancements, ChatGPT-4o still encounters challenges in processing complex and ambiguous inputs, particularly within its audio and visual functionalities, underscoring the need for richer feedback to drive continued improvements (Hu et al. 2024).

ChatGPT-4o’s image generation capabilities remain in their early stages, yet they hold vast potential for future development. Beyond technical advancements, models like ChatGPT have generated important discussions about their social impacts, particularly on creativity, originality, and productivity. Researchers note that generative AI promotes creativity by providing new perspectives and facilitating idea generation, serving as a catalyst for concepts users might not develop independently (Jang and Kim, 2024). This aligns with the concept of “parallel art”, in which human-AI collaboration produces unique, co-created works (Guo et al. 2023). Additionally, models like ChatGPT have significantly enhanced productivity by streamlining workflows, lowering cognitive load, and enabling users to focus on higher-level tasks (Kim et al. 2024). In this framework, the creative process becomes a collaborative endeavour, completed through human-AI interaction.

Artificial intelligence and urban planning

Artificial intelligence (AI) is increasingly integrated into urban planning, with transformative potential at various stages of the planning process. The introduction of AI-assisted, AI-augmented, AI-automated, and eventually AI-autonomous planning workflows raises questions about the potential impacts and measures required to effectively incorporate AI into urban and regional planning (Peng et al. 2023). For example, AI promotes sustainable urbanization by optimizing resource use and enhancing quality of life through data analysis and predictive modelling (Al-Raeei, 2024). Additionally, Additionally, Bibri et al. (2024) integrated AI through the GPT-4 large language model and retrieval-augmented generation, facilitating the automatic generation of intuitive cluster descriptions and names. This integration marks the first application of natural language processing in academic studies of geographic demographics.

With the advancement of large language models, generative AIs like ChatGPT now possess powerful natural language processing capabilities and an extensive knowledge base in urban planning, enabling them to create city design outputs based on user prompts (Ali et al. 2024). ChatGPT’s database incorporates extensive expertise in architectural design, regional planning, and sustainable urban development, systematically supporting the generation of content with urban planning depth (Fu, 2024). Recent studies have begun exploring ChatGPT’s applications in urban design assistance, demonstrating its effectiveness in conceptualizing plans and inspiring design ideas (Yu et al. 2024). For instance, ChatGPT has been used to assist in urban design evaluation, offering novel design directions and testing for environmental sustainability (Fu et al. 2024). However, most research to date focuses on ChatGPT’s role in supporting professionals, with limited exploration of its ability to utilize its database and algorithms to generate coherent future city designs in response to prompts from general users. This gap highlights the need for systematic research into whether ChatGPT-generated urban design images accurately reflect its knowledge base breadth and algorithmic responsiveness in meeting non-expert user demands.

Importance-performance analysis

Importance-Performance Analysis (IPA) is a visual decision-making tool using a two-dimensional grid to compare the importance and performance of various attributes, prioritizing specific indicators for improvement (Aicher et al. 2023). In the tourism industry, IPA plots visitors’ pre-trip expectations, post-trip satisfaction, and the importance of each attribute on a grid to guide tour design decisions (Duke and Persia, 1996). In higher education, IPA enhances teaching quality by visually representing which teaching attributes are most important to students and how well instructors perform on these attributes, thus guiding course design and improvement (Cladera, 2021). In public transportation, IPA assesses customer satisfaction by identifying gaps between the importance and performance of service attributes (Esmailpour et al. 2020). These examples illustrate that IPA applies across various fields, systematically identifying and addressing specific indicators to improve overall quality and user satisfaction.

The traditional IPA method plots average importance and performance results of attributes on a chart (Fig. 1a), classifying them into four quadrants: Quadrant 1: “Concentrate Here”, Quadrant 2: “Keep Up the Good Work”, Quadrant 3: “Low Priority”, and Quadrant 4: “Possible Overkill” (Martilla and James, 1977). IPA typically uses an X-Y coordinate graph centred on a scale to display results, with quadrant interpretations in Table 1. The X-axis represents “Performance” (PE), with better performance further right. The Y-axis represents “Importance” (IM), with higher importance higher up the axis (Rašovská et al. 2021). The coordinate plane is divided into four quadrants by horizontal and vertical lines, explaining the relationship between importance and performance. Once attributes are mapped to their quadrants, managers can adjust strategies to balance importance and performance (Boley et al. 2017, Cao et al. 2024).

While centreing the crosshairs on the median of the scale may seem the most transparent way to position the quadrants (Oh, 2001), most attributes usually fall into the “keep up the good work” quadrant because respondents tend to give high ratings for both performance and importance (Phadermrod et al. 2019). This clustering diminishes the value of discussing relative strengths and weaknesses of attributes (Boley et al. 2017). To address clustering and ensure a more dispersed distribution of attributes across the quadrants, we adopted a data-centred approach by positioning the crosshairs at the mean values of the measured importance and performance items (Bekar et al. 2023). This method effectively resolves data clustering, ensuring attributes are more evenly distributed among the quadrants (Bi et al. 2019, Cao et al. 2024).

To enhance the interpretive power of IPA results, a 45-degree upward diagonal line can differentiate areas where performance exceeds importance (PE > IM) from areas where performance falls below importance (PE < IM) (Cladera, 2021, Fan, 2022). This 45-degree diagonal line, known as the Iso-Diagonal Line (Fig. 1b), indicates that all points on this line have equal improvement priority (IM = PE). In the Expectation-Confirmation Paradigm (Oliver, 1980, Miao et al. 2022) and User Experience Design, this implies that participant satisfaction with an attribute is based on the difference between their expectations and performance evaluation of that attribute. Using this line allows gap analysis. If an attribute is above this line (IM > PE), it indicates performance evaluation is lower than expectations, leading to negative disconfirmation, suggesting participants may be dissatisfied. Conversely, if an attribute falls below this line (PE > IM), it indicates performance evaluation exceeds expectations, leading to positive disconfirmation, suggesting participants are likely to be satisfied (Nunkoo et al. 2020).

The present study

This study is grounded in User Experience Design (UXD), which emphasizes active user involvement to better understand user needs and tasks, thereby enhancing the product’s overall usability and practicality (Mao et al. 2005). This approach, known as User-Centred Design (UCD), is widely acknowledged as an industry best practice (Bullinger et al. 2010). A core principle of UXD is the inclusion of all stakeholders in the design process, a concept grounded in systems theory and participatory design (Chan et al. 2020). Additionally, the concept of service design, closely related to UXD, emphasizes co-creation and a human-centred approach. Incorporating interactive feedback mechanisms can enhance user engagement and foster value co-creation, making the design process more engaging and emotionally appealing to users (Martín-Peña et al. 2024).

ChatGPT-4o is recognized for its efficiency in handling multimodal tasks, including image generation, editing, and image-based dialogue. With simple text prompts, users can perform complex image operations. Wu et al. (2023a) developed a multimodal system that generates images from user text prompts, offering a more natural mode of human-computer interaction. This system enables users to communicate with the model using natural language without needing specialized image processing skills, highlighting its practical potential and frequent citation in studies (Ray, 2023, Liu et al. 2024, Wang et al. 2024). Since its inception, ChatGPT-4o’s database has continuously evolved through global user interactions; however, limited research has examined its autonomous imaginative capability as enabled by its large model algorithm. Existing studies suggest that LLMs serve as intuitive tools for general users, regardless of their technical expertise (Jang and Kim, 2024). Based on this, the present study grants ChatGPT-4o full autonomy in image generation, offering only thematic instructions with no additional creative intervention.

User Experience Design (UXD) and ChatGPT-4o intersect in innovative ways, enhancing iterative applications for designing and analysing human-computer interactions. Through rapid engineering and an advanced function library, ChatGPT-4o adapts to diverse robotic tasks and simulators, enabling users to interact with robots through natural language instructions and thereby enhancing overall user experience (Vemprala et al. 2024). Moreover, ChatGPT-4o’s core technologies—large-scale language models, contextual learning, and reinforcement learning from human feedback—enable it to excel in language comprehension and generation tasks (Wu et al. 2023b). Within Cyber-Physical-Social Systems (CPSS), ChatGPT-4o employs a data-driven analytical approach, treating complex systems as a black box and focusing on the input-output relationships. This approach aids in understanding and enhancing user experience by analysing large datasets and identifying patterns without needing to examine the system’s internal complexities (Xue et al. 2023). This foundation underpins the present study, where subjective user feedback data effectively informs ChatGPT’s ongoing improvements.

Methods

This study uses a mixed-methods research design (Ivankova et al. 2006), integrating qualitative focus group discussions with quantitative public surveys to explore the application of ChatGPT-4o in future city planning. The qualitative phase involved expert focus groups identifying key indicators for evaluating urban design images generated by ChatGPT. Subsequently, a public survey assessed residents’ perceptions of these indicators using Importance-Performance Analysis (IPA). This methodology provides a comprehensive framework for understanding the strengths and weaknesses of AI-generated urban designs, highlighting areas for improvement. The complete framework of the study is shown in Fig. 2.

All activities during this research ensured the systematic nature of the research and adherence to ethical standards. This included precise recruitment of potential subjects, rigorous screening to select suitable individuals, and subsequent data collection. This process ensured strict compliance with ethical review requirements and maintained the quality and validity.

Participant

The focus group respondents were experts from four key universities in China, specializing in urban planning and art & design. To ensure the sample’s representativeness and relevance, we used purposive sampling techniques. Four selection criteria were set: (1) at least five years of professional experience in their field; (2) involvement as a principal investigator or participant in provincial or higher-level projects within the last five years; (3) publication of at least three high-quality papers in international journals within the past five years; (4) willingness to participate in online discussions for the focus group. Invitation emails were sent to 26 experts using publicly available information from university websites. The emails included a study overview and an informed consent form. Ultimately, nine experts responded positively and signed the consent forms. The experts’ basic information is presented in Table 2.

Survey participants were selected from four cities in different provinces of China: Wuhan, Jinan, Guangzhou, and Chengdu. Through the alumni platform of the authors’ affiliated universities, we contacted community leaders willing to help reach various neighbourhood WeChat groups in each city. Random sampling was conducted within these groups. A total of 640 questionnaires were distributed, and 427 valid responses were collected. The demographic statistics of the survey respondents are shown in Table 3. The gender distribution was relatively balanced, with 202 male and 225 female participants, reflecting a gender-balanced sample. The age structure of the sample spanned multiple age groups, indicating diversity. The sample revealed a wide range of educational backgrounds. The highest number of participants, 112, had an Undergraduate level of education.

Stimulation

To explore ChatGPT-4o’s ability to autonomously envision future urban landscapes, we designed an AI-driven image generation process that allowed the model to create futuristic images of Beijing without any predefined constraints. This approach enabled a more precise analysis of how ChatGPT-4o utilizes its internal dataset and computational algorithms to interpret the future of an existing city. As the capital of China, Beijing features a highly recognizable urban landscape, ensuring that individuals have a foundational impression of the city. This makes it an ideal test case for assessing AI-generated future urban designs.

Given that ChatGPT-4o currently restricts image generation to one image per request, we employed a multi-stage independent generation method. Each image was generated separately to ensure that prior outputs did not influence subsequent results. To eliminate potential memory effects, we explicitly instructed ChatGPT-4o to disregard previous interactions and treat each request as an independent task. Multiple pre-trials were conducted to refine and optimize the prompt, ensuring that it effectively guided ChatGPT-4o to generate images aligned with our research objectives. Additionally, we referenced validated methodologies from previous studies to ensure the prompt’s effectiveness (Vemprala et al. 2024).

To mitigate any underlying model biases that may be influenced by session-based training updates, the following standardized prompt was issued across eight independent ChatGPT-4o accounts:

“Please generate an image of Beijing in the future using your internal knowledge, dataset, and algorithms. Do not reference any prior conversations or memory. Create a unique vision of the city’s future as imagined by your model.”

The ChatGPT-4o account holders acted as evaluators of the generated images. After each image was generated, the account holders reviewed the output for any homogenization patterns or significant errors, such as inconsistencies with fundamental urban planning principles (e.g., road collisions, image distortions, or incoherence). Evaluation was conducted following predefined exclusion criteria based on established urban planning principles (Lowe, 2018, Haghani et al. 2023, Oktay, 2023). If such errors were detected, the image was discarded, and a new image was generated. To encourage diversity without introducing human bias, evaluators were instructed to use minimal refinement prompts:

“Please generate another image of Beijing in the future, depicting a different perspective within the city. Ensure that this vision presents a distinct viewpoint while still being an autonomous creation based on your internal knowledge and dataset.”

The evaluators continued generating images until all 10 images in each set were reviewed. This refined prompt aimed to capture diverse urban depictions of future Beijing while still allowing ChatGPT-4o to autonomously create imaginative urban designs. Ultimately, the AI-generated dataset comprised 80 images across 8 sets.

To ensure randomness and representativeness in the experiment, one set of images was randomly selected from the eight generated sets for analysis. To eliminate potential order effects, the 10 images were presented in a randomized sequence within the questionnaire. This procedure ensured the randomness of image selection and the scientific validity of the results. The final sampled image set is shown in Fig. 3.

Instrument

In the initial phase of this study, we used focus groups to identify specific criteria for evaluating future urban planning images. A focus group is a qualitative research method that collects participants’ views and feedback through group discussions (Morgan, 1996). This technique is well-suited for exploring emerging fields, allowing an in-depth understanding of participants’ genuine thoughts and feelings (Rabiee, 2004). Due to geographical constraints and scheduling considerations, our focus group discussions were conducted online. Each participant signed an informed consent form before the discussion, indicating their understanding and agreement to participate. The first author served as the moderator, guiding the two-hour discussions to ensure each participant could freely express their thoughts. The moderator used a semi-structured interview guide to maintain an organized flow and deeply explore topics. Special attention was given to question wording to ensure they were precise and inclusive, encouraging participants to freely express diverse viewpoints (Nyumba et al. 2018).

In the second phase, we developed an IPA questionnaire based on the focus group data analysis results (Boley et al. 2017) for data collection. The questionnaire design adhered to informed consent principles, ensuring participants were fully aware of the study’s content and purpose before completing it. The questionnaire was divided into three main sections, with a total of 19 items, to comprehensively collect participants’ basic information and their subjective evaluations of each criterion. Specifically, the first part of the questionnaire showed ten randomly arranged ChatGPT-generated images, followed by questions on basic participant information: gender, age, and educational background. The third part, consisting of 16 items, measured the indicators deemed feasible by experts and was presented in a randomized order.

A pilot study was conducted with 54 residents participating in the survey. The reliability analysis showed a Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.835, indicating good reliability. Additionally, the KMO value was 0.855, and the significance of Bartlett’s test of sphericity was 0.000 < 0.01, demonstrating good data validity (Aharonovich et al. 2017). Based on the preliminary survey results, we discussed ambiguous statements with professional professors and made minor revisions to the questionnaire to ensure more reliable statistical results in subsequent data collection.

Data collection procedure

To ensure effective and reliable data collection, we designed two consecutive focus group meetings and implemented rigorous steps for smooth conduct. In the first meeting, after all respondents entered the online meeting room, the moderator introduced the participants and stated the discussion topic. Subsequently, each respondent, in random order, shared their views on future urban planning designs and was asked to identify the specific criteria they understood. This phase lasted 80 min. During the 20-min break, the moderator summarized the criteria collected during the first phase.

In the second meeting, respondents re-entered the online meeting room. The moderator asked the art and design experts to evaluate whether these criteria could be identified in the images based on their expertise and to explain their reasoning. Following this, urban planning experts discussed the screening results and the reasons provided, ultimately reaching a consensus. The moderator meticulously documented the entire process. After the meeting, the recorded content was transcribed and sent to the respondents via email for proofreading and confirmation, ensuring data accuracy and completeness.

After completing the qualitative data analysis and designing the questionnaire, we began collecting data. First, we contacted the heads of the residents’ committees in four targeted communities. Through communication, we gained their support, ensuring they understood the research purpose and process. Based on transparency and mutual trust, we agreed to pay each committee head 50 CNY for assisting with the study. This compensation acknowledged their time and effort and facilitated the smooth progress of the research.

With the community heads’ assistance, we provided potential participants with detailed information about the research purpose, significance, and their role, ensuring each participant signed an informed consent form after fully understanding the study. This process ensured respect for participants’ rights and adherence to informed consent principles, upholding ethical standards. To increase participation rates and respect participants’ time and contributions, we offered each participant 3 CNY for completing the questionnaire. This compensation mechanism improved the response rate, ensuring the quality and representativeness of the collected data.

Data analysis

This study employed template analysis for the focus group interview data (Brooks et al. 2015, Cao et al. 2025). During discussions in both meetings, each expert provided specific criteria after sharing their views. In the second meeting, all participants discussed these criteria in depth and reached a consensus. During the focus group discussions, the moderator and experts processed the information provided by the respondents in real-time. After the discussions, the moderator and experts immediately summarized and presented preliminary results (i.e., the template). This immediate feedback helped validate and confirm participants’ viewpoints, ensuring the accuracy and completeness of the data (Cohen et al. 2006). In the post-transcription analysis phase, each author meticulously reviewed the original meeting content and compared the qualitative data with the preliminary template (King, 2012). This comparative analysis found no new criteria beyond the preliminary template, suggesting data saturation and determining the final number of criteria. The entire analysis process was meticulously documented and presented in a written report to ensure research transparency and result reliability.

To accurately explore residents’ attitudes, we used statistical methods for data analysis. In the pilot survey phase, we used SPSS to conduct reliability and validity tests on the questionnaire content. Subsequently, we used Importance-Performance Analysis (IPA) to investigate the data for each criterion. We adopted a hybrid crosshair placement method, combining mean-centred crosshairs and a 45° diagonal line approach. This involved superimposing a 45° upward diagonal line (y = x) on the traditional median-centred axes to distinguish areas where performance exceeds importance (PE > IM) from areas where performance falls below importance (PE < IM) (Deng and Pierskalla, 2018). Although the discussion results were analysed based on both the data-centred regions and the satisfaction intervals defined by the Iso-Diagonal Line, all three auxiliary lines (median-centred, mean-centred, and Iso-Diagonal Line) were visible on each IPA chart. This visibility demonstrated decisions based on the placement of the crosshairs. Compared to a single method, this hybrid approach provided richer and more nuanced findings. Through the aforementioned data analysis methods, we comprehensively examined the residents’ subjective evaluations of ChatGPT-generated images.

Results

Non-identifiable indicators

During the focus group discussion, although the five indicators—social harmony, economic feasibility, residential comfort, cultural representation, and functionality—were considered important factors in future urban planning and design, experts in the arts recommended their exclusion. After hearing the rationale, urban planning experts also agreed. The excluded indicators and their reasons are presented in Table 4.

Identifiable Indicators

Based on focus group discussions and comprehensive data analysis, no new feasible indicators were identified (Fig. 4). The following eight indicators—creativity, traffic rationality, design coherence, environmental greening, public space utilization, technological sense, visual quality, and cultural representation—were recognized as identifiable in the stimulus images and received unanimous support from all experts.

Creativity is regarded as a key element in future city design, embodying imagination. In this study, creativity specifically refers to the originality and innovation of AI-generated urban concepts, rather than variations among individual images. Creativity embodies novelty and serves as the driving force that distinguishes future cities from current designs, propelling urban development. The degree to which a future city image demonstrates unique, innovative features is essential in assessing its creativity. “A creatively designed city image should spark curiosity and imagination in viewers, allowing them to see the limitless possibilities of future cities” (IP 3). Participants unanimously supported this perspective, agreeing that innovation and uniqueness are core evaluation criteria. Creativity is evident not only in grand architectural structures and urban layouts but also in innovative applications of public art, green spaces, and infrastructure.

Rational transportation system design is fundamental to the functioning of future cities. “A well-designed transportation system can effectively alleviate traffic congestion and improve travel efficiency. Showcasing the transportation system through images allows one to intuitively see the rationality and convenience of urban traffic planning” (IP 7). Transportation system design directly impacts citizens’ quality of life, as effective planning reduces commute times and enhances travel comfort and efficiency. “An efficient transportation system is not only the lifeblood of city operations but also crucial to the quality of life for every citizen. Optimizing traffic design can significantly improve the travel experience of citizens” (IP 4). As future cities confront the challenges of high population density and urban expansion, effective transportation planning is essential to support sustainable development and ensure traffic safety.

The importance of design coherence lies in its ability to foster a harmonious urban environment through consistent visual language and design elements. Experts agreed that evaluating design coherence depends on the degree to which urban planning elements in the images are consistent and coordinated, forming a cohesive whole. Design coherence enhances not only the aesthetic appeal of a city but also the systematic and coordinated nature of the planning process. “Design unity can convey a sense of harmony, making people feel the integrity and coherence of the city” (IP 4). This cohesive design style is reflected in architecture, street layouts, and public space planning, which not only elevates the city’s visual appeal but also strengthens residents’ sense of belonging and identity.

Environmental greening focuses on whether urban design emphasizes environmental protection and sustainable development, with the rational distribution of greenery as its core element. Experts believe that future cities must prioritize environmental protection and sustainable development. “Environmental greening is not only a component of urban aesthetics but also a necessary condition for achieving sustainable development” (IP 2). The expert explained, “Through images showcasing green layouts, one can intuitively see the city’s efforts in environmental protection and green space distribution” (IP 6). Greening enhances the city’s aesthetic appeal and positively impacts the psychological and physical health of urban residents. A sustainable environment can significantly improve the city’s climate, creating a more liveable environment.

Experts discussed the multifaceted role of rational public space utilization in urban life. The design of public spaces like parks and squares is assessed based on whether they provide good recreational venues for citizens. Experts believe rational use of public spaces can enhance residents’ quality of life. “By showcasing public space designs in images, one can observe the planning and utilization of public resources in the city” (IP 2). Experts also pointed out that public spaces in future cities should have diverse functions to meet the needs of different groups.

Technological integration involves both individual technological elements and the overall intelligent layout and system integration. Experts agreed that the presence and advancement of technological elements in images (such as smart transportation and intelligent buildings) directly reflect the city’s technological level and potential for future development. “Technological integration is a hallmark of future cities and a key measure of a city’s ability to sustain development in the future” (IP 1). Experts also discussed how technological integration can be communicated through images. Advanced building materials, innovative architectural structures, and efficient energy management systems effectively showcase technological integration and can be visually represented in images, enhancing viewers’ perception of the high-tech level of future cities.

Experts agreed that when geographic location is specified in AI-generated images, cultural representation should be considered an independent evaluation criterion, especially as AI continues to integrate cultural elements into image generation. Initially, some experts questioned whether AI-generated images could effectively convey cultural elements, arguing that cultural identity is typically expressed through historical narratives, traditions, and local contexts—features that might be difficult to capture in static images. However, others pointed out that architectural styles, iconic landmarks, and urban aesthetics serve as powerful visual representations of a city’s cultural identity. A urban design expert stated, “Once a specific city is defined, visual elements such as architectural forms and spatial layouts can strongly convey the essence of its culture” (IP 5). In agreement, an art scholar added, “Culture is not static—it evolves over time. Even when depicting future cityscapes, AI-generated images should reflect cultural continuity” (IP 7). Through discussion, the experts reached a consensus that although AI-generated images may not capture all dimensions of cultural characteristics, cultural representation remains a recognizable and assessable visual attribute in urban imagery.

The visual quality of urban planning designs in the images was intensely debated among the experts. Initially, opinions diverged regarding visual quality and design unity, with some experts arguing that visual aesthetics are inherently linked to design unity. However, art design experts offered a different perspective, suggesting that diversity and richness in design could equally enhance visual aesthetics. “Visual quality is not solely about design unity; diversity and richness can also bring a unique beauty”, noted one art expert. “Therefore, we should consider visual quality as a separate criterion” (IP 8). Eventually, the urban planning experts agreed to treat visual quality as an independent indicator. Visual quality directly affects people’s first impressions and overall perception of a city. “High-quality visual design can enhance the city’s beauty, making people feel visually pleased and satisfied” (IP 8). Visual quality involves aesthetic considerations of architecture and landscape design and the comprehensive use of colours, materials, and lighting effects, making it an especially important criterion.

Results of importance-performance analysis

Table 5 provides descriptive statistics offering a comprehensive overview of the performance (PE) and importance (IM) scores for the eight indicators (A1 to A8). The table includes the mean scores for PE and IM, their respective rankings, the mean deviation between PE and IM, and the corresponding t-values and p-values for each attribute. The performance of A6 (Technological Sense) was rated the best (PE = 3.67), while A1 (Creativity) was considered the most important (IM = 3.79).

Based on the descriptive statistical results, we constructed an IPA matrix. As shown in Fig. 5, A1 (Creativity) is in Quadrant 1, while A6 (Technological Sense) and A7 (Visual Quality) are in Quadrant 2. A2 (Traffic Rationality), A4 (Environmental Greening), A5 (Public Space Utilization), and A8 (Cultural Representation) are in Quadrant 3, while A3 (Design Coherence) is in Quadrant 4. According to the Iso-Diagonal Line, A1 (Creativity) is perceived by residents as more important than its performance (IM > PE), indicating a need for improvement in this area. This suggests that residents are dissatisfied with A1. The other indicators are below this line (IM < PE), indicating their performance meets or exceeds their importance.

Discussion

In the focus group phase, we identified eight indicators that can be recognized in images and four that are challenging to identify. While social harmony, economic feasibility, residential comfort, cultural representation, and functionality were considered difficult to capture in images, these indicators nonetheless reflect experts’ visions and expectations for future urban planning design (Winkler, 2012, Li et al. 2020). Although hard to depict through static images, these indicators remain significant for overall future urban planning, highlighting the complexity and multifaceted nature of creating sustainable, liveable, and culturally rich urban environments (Mao et al. 2020). This discussion underscores the need for continued innovation in urban evaluation techniques to adequately capture the dimensions of future urban planning. Such advancements would ensure a comprehensive understanding and representation of elements that contribute to effective and forward-thinking urban design.

Among the eight indicators identifiable in images, experts emphasized that creativity is key to future urban design, while traffic rationality and environmental greening are also highly valued. Galdini and De Nardis (2023) highlighted the role of creative and innovative design in fostering vibrant, sustainable urban environments. Our findings support the view that creativity differentiates future cityscapes from existing ones and signifies urban development and progress (Lee and Chung, 2024). Furthermore, urban residents often express dissatisfaction with existing traffic conditions and green spaces (Benoliel et al. 2021). Car-centric urban planning has left little room for alternative transportation methods like walking and cycling, hindering sustainable urban living. Additionally, the lack of accessible green spaces has led to 76% of residents feeling dissatisfied with urban greenery availability (Psara et al. 2023). These discussions remind planners that addressing these aspects can enhance residents’ quality of life and contribute to a more sustainable urban environment.

The importance of public space utilization and technological integration in future urban planning cannot be overstated, as they enhance inclusivity and efficiency. Contemporary urban landscapes face challenges like the fragmentation and commercialization of public spaces, where these areas are often controlled and privatized. This leads to tensions between different usage practices and movements advocating alternative models of public space utilization (Mela, 2014). In the future, rational use of public spaces can foster more social interactions among citizens, creating friendly environments and enhancing neighbourhood inclusivity to meet diverse community needs (Lau et al. 2021). Additionally, technological advancements are transformative for urban planning, enhancing city services, productivity, and cost-effectiveness (Kumar et al. 2024). However, our study focuses more on the public’s imagination regarding new and unknown technologies, a relatively underexplored discussion in current urban planning research. Anticipating future technologies and their social impacts is crucial for technology assessment and responsible research and innovation. Engaging stakeholders and the public in this process is valuable for understanding and addressing their concerns and expectations (Decker et al. 2017).

Design Coherence and Visual Quality are key issues in the current aesthetic domain, related to urban planning. Our findings on design coherence align with Caliskan and Mashhoodi (2017), who advocate for the visual organization and legibility of urban spaces. Our study extends this view, suggesting that a cohesive design language enhances a city’s visual appeal and navigability. However, experts in art and design pointed out that visual quality is not solely related to uniformity; factors like diversity, uniqueness, and typicality can also lead to varying degrees of aesthetic appreciation (Blijlevens et al. 2017). A cohesive design language ensures various city components work together seamlessly, promoting order and ease of movement. Strategically incorporating diverse and unique elements can prevent visual monotony and enhance the overall aesthetic richness of the urban environment (Salama, 2017).

Based on the IPA results from the public survey, residents provided varying perspectives on different evaluation indicators of the ChatGPT-generated images. A1 (Creativity) was deemed most important as it drives the creation of well-planned communities and inclusive public spaces, shaping interactions among various stakeholders such as citizens, businesses, and the state, fundamentally influencing the planning process (Vidyarthi, 2022). In the quadrant division, A1 was the only indicator in Quadrant 1, indicating that it requires significant investment for improvement. Its position above the Iso-Diagonal Line suggests that ChatGPT’s creativity does not currently meet the satisfaction levels of most respondents, highlighting a gap in the AI’s innovative capabilities. A6 (Technological Sense) received high performance recognition from participants, likely because ChatGPT has absorbed vast amounts of open information through interactions with global users. This extensive knowledge base within the language model allows it to make intelligent predictions about the future (Guo et al. 2023). Both A6 and A7 (Visual Quality) were recognized as crucial and core aspects of ChatGPT’s future urban planning creations, suggesting that these indicators should be maintained and further enhanced.

Surprisingly, A2 (Traffic Rationality), A4 (Environmental Greening), A5 (Public Space Utilization) and A8 (Cultural Representation) were in Quadrant 3. These indicators were generally not deemed important by participants and did not perform well, indicating that they are not core areas for ChatGPT to focus on in future urban planning designs. This could be because participants expect ChatGPT-4o, as the latest version of an intelligent system, to emphasize other, more imaginative indicators. This aspect may require further exploration in future studies. Notably, A3 (Design Coherence) was in Quadrant 4. Although participants did not consider this aspect particularly important, ChatGPT performed well in this area, possibly achieving unexpected visual coherence. Additionally, all indicators from A2 to A8 were below the Iso-Diagonal Line. This demonstrates that even underappreciated design elements can significantly enhance the overall visual quality of urban design images and resident satisfaction through innovative applications and diverse presentations. The performance of these indicators suggests that while ChatGPT has shown potential, there is room for improvement. The insights gained from this analysis provide a concrete reference for further developing and refining ChatGPT’s capabilities in urban planning.

Conclusion

This study explored the application of ChatGPT-4o in future urban planning by identifying and evaluating key indicators through focus groups and public surveys. Eight indicators - creativity, traffic rationality, design coherence, environmental greening, public space utilization, technological sense, visual quality and cultural representation - were analysed to assess their performance and importance as perceived by residents. The IPA results highlighted creativity as the most important indicator needing improvement, while technological sense was highly appreciated. Despite some indicators being less prioritized, the potential for enhancing the overall visual quality of urban design images through innovative approaches was evident.

This study serves as a foundational step toward harnessing AI’s potential to address the complex and multifaceted challenges of future city development. It makes a significant contribution to urban planning and AI by demonstrating how advanced AI models, such as ChatGPT-4o, can generate and evaluate futuristic city designs. The study explores AI’s creative potential in urban visualization and highlights its ability to interact with human-centred evaluation frameworks. Using a robust mixed-methods approach that combines qualitative insights from expert focus groups with quantitative data from public surveys, this research offers a nuanced understanding of residents’ preferences, expectations, and priorities in urban design. Additionally, the methodology introduced in this study is scalable and replicable, enabling its application to other AI tools and contexts and advancing the discourse on sustainable, human-centred city planning.

Although we tried to minimize bias and maximize applicability when designing this study, there are still some limitations. First, relying on static images restricts the ability to capture dynamic interactions and evolving relationships, such as those associated with social harmony and functionality. These indicators often demand longitudinal or interactive assessments, which static representations cannot adequately capture. Additionally, although the focus group comprised experts from diverse fields, their shared cultural and regional background in China may have influenced their perspectives on selecting evaluation indicators. Furthermore, this study exclusively focused on ChatGPT-4o, an advanced language model, as the basis for generating and evaluating urban design images. While this choice allowed a detailed examination of a single model’s capabilities, it represents just one approach to AI-driven urban visualization. This study standardized the AI-generated image process, but some human intervention was unavoidable. Despite minimizing researcher influence through consistent prompts and limited iterations, subjective decisions—such as selecting final images and identifying generation errors (e.g., distortions, unrealistic layouts)—still required human judgement.

As an initial exploration, this study offers valuable directions for future in-depth research. Future studies could investigate integrating dynamic simulations or virtual reality environments to better capture the complexities of urban planning. To address potential biases, future research should involve experts from more diverse cultural and regional backgrounds. This approach would enhance indicator selection and ensure a more globally representative framework for evaluating AI-generated urban designs. Additionally, future research could compare the outputs and performance of various generative AI models, such as Midjourney and DALL-E, to highlight differences in design coherence, cultural adaptability, and creative depth. The limitation of Human intervention suggests that future studies could explore more automated or objective methods for evaluating AI-generated content, such as using computational metrics or larger-scale crowd evaluations.

Data availability

The data for this study are publicly available on the Github website - https://github.com/Zeno5577/ChatGPT-image-IPA.git.

References

Abalo J, Varela J, Manzano V (2007) Importance values for Importance-Performance Analysis: A formula for spreading out values derived from preference rankings. Journal of Business Research 60:115–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2006.10.009

Aharonovich E, Shmulewitz D, Wall MM, Grant BF, Hasin DS (2017) Self-reported cognitive scales in a US national survey: reliability, validity, and preliminary evidence for associations with alcohol and drug use. Addiction 112:2132–2143. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13911

Aicher TJ, Heere B, Odio MA, Ferguson JM (2023) Looking beyond performance: understanding service quality through the importance-performance analysis. Sport Management Review 26:448–470

Ali R, Tang OY, Connolly ID, Abdulrazeq HF, Mirza FN, Lim RK, Johnston BR, Groff MW, Williamson T, Svokos K et al. (2024) Demographic representation in 3 leading artificial intelligence text-to-image generators. JAMA Surgery 159:87–95. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2023.5695

Al-Raeei M (2024) The smart future for sustainable development: Artificial intelligence solutions for sustainable urbanization. Sustainable Development. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.3131

Bekar İ, Kutlu I, Ergün R (2023) Importance performance analysis for sustainability of reused historical building: Mardin Sabanci City Museum and art gallery. Open House International 49:550–573. https://doi.org/10.1108/OHI-04-2023-0080

Benoliel MA, Manso M, Ferreira PD, Silva CM, Cruz CO (2021) “Greening” and comfort conditions in transport infrastructure systems: Understanding users’ preferences. Building and Environment 195:107759. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2021.107759

Bi J-W, Liu Y, Fan Z-P, Zhang J (2019) Wisdom of crowds: Conducting importance-performance analysis (IPA) through online reviews. Tourism Management 70:460–478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2018.09.010

Bibri SE, Huang J, Jagatheesaperumal SK, Krogstie J (2024) The synergistic interplay of artificial intelligence and digital twin in environmentally planning sustainable smart cities: a comprehensive systematic review. Environmental Science and Ecotechnology: 100433

Blijlevens J, Thurgood C, Hekkert P, Chen L-L, Leder H, Whitfield TWA (2017) The Aesthetic Pleasure in Design Scale: The development of a scale to measure aesthetic pleasure for designed artifacts. Psychology of Aesthetics Creativity and the Arts 11:86–98. https://doi.org/10.1037/aca0000098

Boley BB, McGehee NG, Tom Hammett AL (2017) Importance-performance analysis (IPA) of sustainable tourism initiatives: The resident perspective. Tourism Management 58:66–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.10.002

Brooks J, McCluskey S, Turley E, King N (2015) The utility of template analysis in qualitative psychology research. Qualitative Research in Psychology 12:202–222. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2014.955224

Bullinger H-J, Bauer W, Wenzel G, Blach R (2010) Towards user centred design (UCD) in architecture based on immersive virtual environments. Computers in Industry 61:372–379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compind.2009.12.003

Caliskan O, Mashhoodi B (2017) Urban coherence: A morphological definition. Urban Morphology 21:123–141. https://doi.org/10.51347/jum.v21i2.4065

Cao Z, Mustafa M, Mohd Isa MH (2024) Balancing priorities: An importance-performance analysis of architectural heritage protection in China’s historical cities. Frontiers of Architectural Research. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foar.2024.11.001

Cao Z, Huang L, Mao Y, Mustafa M, Mohd Isa MH (2025) Navigating complexity in sustainable conservation: A multi-criteria decision making of architectural heritage in urbanizing China. Journal of Building Engineering 102:111906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2025.111906

Caprotti F, Cugurullo F, Cook M, Karvonen A, Marvin S, McGuirk P, Valdez A-M (2024) Why does urban Artificial Intelligence (AI) matter for urban studies? Developing research directions in urban AI research. Urban Geography 45:883–894. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2024.2329401

Chan KY, Kwong C, Wongthongtham P, Jiang H, Fung CK, Abu-Salih B, Liu Z, Wong T, Jain P (2020) Affective design using machine learning: a survey and its prospect of conjoining big data. International Journal of Computer Integrated Manufacturing 33:645–669. https://doi.org/10.1080/0951192X.2018.1526412

Cladera M (2021) An application of importance-performance analysis to students’ evaluation of teaching. Educational Assessment Evaluation and Accountability 33:701–715. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11092-020-09338-4

Cohen DJ, Leviton LC, Isaacson N, Tallia AF, Crabtree BF (2006) Online diaries for qualitative evaluation: gaining real-time insights. American Journal of Evaluation 27:163–184. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098214006288448

Cugurullo F, Caprotti F, Cook M, Karvonen A, McGuirk P, Marvin S (2024) The rise of AI urbanism in post-smart cities: A critical commentary on urban artificial intelligence. Urban Studies 61:1168–1182. https://doi.org/10.1177/00420980231203386

Decker M, Weinberger N, Krings B-J, Hirsch J (2017) Imagined technology futures in demand-oriented technology assessment. Journal of Responsible Innovation 4:177–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/23299460.2017.1360720

Deng J, Pierskalla CD (2018) Linking Importance–Performance Analysis, Satisfaction, and Loyalty: A Study of Savannah, GA. Sustainability 10:704. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10030704

Driessen T, Dodou D, Bazilinskyy P, De Winter J (2024) Putting ChatGPT vision (GPT-4V) to the test: risk perception in traffic images. Royal Society Open Science 11:231676. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.231676

Duke CR, Persia MA (1996) Performance-importance analysis of escorted tour evaluations. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing 5:207–223. https://doi.org/10.1300/J073v05n03_03

Esmailpour J, Aghabayk K, Vajari MA, De Gruyter C (2020) Importance–Performance Analysis (IPA) of bus service attributes: A case study in a developing country. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 142:129–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2020.10.020

Fan S-C (2022) An importance–performance analysis (IPA) of teachers’ core competencies for implementing maker education in primary and secondary schools. International Journal of Technology and Design Education 32:943–969. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10798-020-09633-7

Feng M, Mangan J, Wong C, Xu M, Lalwani C (2014) Investigating the different approaches to importance–performance analysis. The Service Industries Journal 34:1021–1041. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2014.915949

Floridi L, Chiriatti M (2020) GPT-3: Its nature, scope, limits, and consequences. Minds and Machines 30:681–694. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11023-020-09548-1

Fu X (2024) Natural Language Processing in Urban Planning: A Research Agenda. Journal of Planning Literature: 08854122241229571. https://doi.org/10.1177/08854122241229571

Fu X, Wang R, Li C (2024) Can ChatGPT evaluate plans? Journal of the American Planning Association 90:525–536. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2023.2271893

Galdini R, De Nardis S (2023) Urban informality and users-led social innovation: Challenges and opportunities for the future human centred city. Futures 150:103170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2023.103170

Guo C, Lu Y, Dou Y, Wang F-Y (2023) Can ChatGPT boost artistic creation: the need of imaginative intelligence for parallel art. IEEE/CAA Journal of Automatica Sinica 10:835–838. https://doi.org/10.1109/JAS.2023.123555

Haghani M, Sabri S, De Gruyter C, Ardeshiri A, Shahhoseini Z, Sanchez TW, Acuto M (2023) The landscape and evolution of urban planning science. Cities 136:104261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2023.104261

Hu M, Qian J, Pan S, Li Y, Qiu RL, Yang X (2024) Advancing medical imaging with language models: featuring a spotlight on ChatGPT. Physics in Medicine & Biology 69:10TR01. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6560/ad387d

Ivankova NV, Creswell JW, Stick SL (2006) Using mixed-methods sequential explanatory design: from theory to practice. Field Methods 18:3–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X05282260

Jang KM, Kim J (2024) Multimodal Large Language Models as Built Environment Auditing Tools. The Professional Geographer: 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/00330124.2024.2404894

Jang KM, Chen J, Kang Y, Kim J, Lee J, Duarte F, Ratti C (2024) Place identity: a generative AI’s perspective. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 11:1–16. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03645-7

Javan R, Mostaghni N (2024) AI-powered Hyperrealism: Next step in cinematic rendering? Radiology 310:e231971. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.231971

Kim K, Cho K, Jang R, Kyung S, Lee S, Ham S, Choi E, Hong G-S, Kim N (2024) Updated primer on generative artificial intelligence and large language models in medical imaging for medical professionals. Korean Journal of Radiology 25:224. https://doi.org/10.3348/kjr.2023.0818

King N (2012) Doing template analysis. Qualitative Organizational Research: Core Methods and Current Challenges 426:426–450. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526435620.n24

Kumar V, Gunner S, Pregnolato M, Tully P, Georgalas N, Oikonomou G, Karatzas S, Tryfonas T (2024) Sense (and) the city: From Internet of Things sensors and open data platforms to urban observatories. IET Smart Cities. https://doi.org/10.1049/smc2.12081

Lau BPL, Ng BKK, Yuen C, Tunçer B, Chong KH (2021) The study of urban residential’s public space activeness using space-centric approach. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 8:11503–11513. https://doi.org/10.1109/JIOT.2021.3051343

Lee BC, Chung J (Jae) (2024) An empirical investigation of the impact of ChatGPT on creativity. Nature Human Behaviour: 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-024-01953-1

Li J, Wang Y, Ni Z, Chen S, Xia B (2020) An integrated strategy to improve the microclimate regulation of green-blue-grey infrastructures in specific urban forms. Journal of Cleaner Production 271:122555. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122555

Liu H, Li C, Wu Q, Lee YJ (2024) Visual instruction tuning. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 36

Lowe M (2018) Embedding health considerations in urban planning. Planning Theory & Practice 19:623–627. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2018.1496979

Lu Y, Guo C, Dou Y, Dai X, Wang F-Y (2023) Could ChatGPT Imagine: Content control for artistic painting generation via large language models. Journal of Intelligent & Robotic Systems 109:39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10846-023-01956-6

Mao J-Y, Vredenburg K, Smith PW, Carey T (2005) The state of user-centered design practice. Communications of the ACM 48:105–109. https://doi.org/10.1145/1047671.1047677

Mao Q, Wang L, Guo Q, Li Y, Liu M, Xu G (2020) Evaluating cultural ecosystem services of urban residential green spaces from the perspective of residents’ satisfaction with green space. Frontiers in Public Health 8:226. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.00226

Martilla JA, James JC (1977) Importance-Performance Analysis. Journal of Marketing January: 77–79. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224297704100112

Martín-Peña ML, García-Magro C, Sánchez-López JM (2024) Service design through the emotional mechanics of gamification and value co-creation: a user experience analysis. Behaviour & Information Technology 43:486–506. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2023.2177823

Mela A (2014) Urban public space between fragmentation, control and conflict. City, Territory and Architecture 1:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40410-014-0015-0

Miao F, Kozlenkova IV, Wang H, Xie T, Palmatier RW (2022) An emerging theory of Avatar Marketing. Journal of Marketing 86:67–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022242921996646

Morgan DL (1996) Focus Groups. Annual Review of Sociology 22:129–152. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.22.1.129

Nunkoo R, Teeroovengadum V, Ringle CM, Sunnassee V (2020) Service quality and customer satisfaction: The moderating effects of hotel star rating. International Journal of Hospitality Management 91:102414. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2019.102414

Oermann EK, Kondziolka D (2023) On chatbots and generative artificial intelligence. Neurosurgery 92:665–666

Oh H (2001) Revisiting importance–performance analysis. Tourism Management 22:617–627. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(01)00036-X

Oktay D (2023) Influences of urban design on perceived social attributes and quality of life: a comparative study in two English neighbourhoods. URBAN DESIGN International 28:304–319. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41289-023-00218-z

Oliver RL (1980) A cognitive model of the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction decisions. Journal of Marketing Research 17:460–469. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378001700405

O.Nyumba T, Wilson K, Derrick CJ, Mukherjee N (2018) The use of focus group discussion methodology: Insights from two decades of application in conservation. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 9:20–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.12860

Osco LP, de Lemos EL, Gonçalves WN, Ramos APM, Marcato Junior J (2023) The potential of visual ChatGPT for remote sensing. Remote Sensing 15:3232. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs15133232

Peng Z-R, Lu K-F, Liu Y, Zhai W (2023) The Pathway of Urban Planning AI: From Planning Support to Plan-Making. Journal of Planning Education and Research: 0739456X231180568. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X231180568

Phadermrod B, Crowder RM, Wills GB (2019) Importance-performance analysis based SWOT analysis. International Journal of Information Management 44:194–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2016.03.009

Psara O, Fonseca F, Nisiforou O, Ramos R (2023) Evaluation of urban sustainability based on transportation and green spaces: the case of Limassol, Cyprus. Sustainability 15:10563. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151310563

Rabiee F (2004) Focus-group interview and data analysis. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 63:655–660. https://doi.org/10.1079/PNS2004399

Rašovská I, Kubickova M, Ryglová K (2021) Importance–performance analysis approach to destination management. Tourism Economics 27:777–794. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354816620903913

Ray PP (2023) ChatGPT: A comprehensive review on background, applications, key challenges, bias, ethics, limitations and future scope. Internet of Things and Cyber-Physical Systems 3:121–154

Riemer K, Peter S (2024) Conceptualizing generative AI as style engines: Application archetypes and implications. International Journal of Information Management 79:102824. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2024.102824

Salama AM (2017) Plurality and diversity in architectural and urban research. ArchNet-IJAR: International Journal of Architectural Research 11:1–5. https://doi.org/10.26687/archnet-ijar.v11i2.1280

Sever I (2015) Importance-performance analysis: A valid management tool? Tourism Management 48:43–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.10.022

Vemprala SH, Bonatti R, Bucker A, Kapoor A (2024) Chatgpt for robotics: Design principles and model abilities. IEEE Access. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3387941

Vidyarthi S (2022) The urban planning imagination: Nicholas Phelps. Journal of the American Planning Association 88:444–444. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2022.2070405

Wang W, Chen Z, Chen X, Wu J, Zhu X, Zeng G, Luo P, Lu T, Zhou J, Qiao Y, others (2024) Visionllm: Large language model is also an open-ended decoder for vision-centric tasks. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 36

Winkler T (2012) Between economic efficacy and social justice: Exposing the ethico-politics of planning. Cities 29:166–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2011.11.014

Wu C, Yin S, Qi W, Wang X, Tang Z, Duan N (2023a) Visual chatgpt: Talking, drawing and editing with visual foundation models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.04671. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2303.04671

Wu T, He S, Liu J, Sun S, Liu K, Han Q-L, Tang Y (2023b) A brief overview of ChatGPT: The history, status quo and potential future development. IEEE/CAA Journal of Automatica Sinica 10:1122–1136. https://doi.org/10.1109/JAS.2023.123618

Xue X, Yu X, Wang F-Y (2023) ChatGPT chats on computational experiments: From interactive intelligence to imaginative intelligence for design of artificial societies and optimization of foundational models. IEEE/CAA Journal of Automatica Sinica 10:1357–1360. https://doi.org/10.1109/JAS.2023.123585

Yu S, Yang Y, Li J, Guo K, Wang Z, Liu Y (2024) Exploring low-carbon and sustainable urban transformation design using ChatGPT and artificial bee colony algorithm. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 11:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02765-4

Zhu N, Zhang N, Shao Q, Cheng K, Wu H (2024) OpenAI’s GPT-4o in surgical oncology: revolutionary advances in generative artificial intelligence. European Journal of Cancer. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2024.114132

Acknowledgements

We thank all the research participants for their efforts and thank Prof. Wan Yunqing for providing academic support during the research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z. Cao conceptualized the study and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Z. Cao and Y. Mao prepared Figs. 1–5. Y. Mao contributed to data collection and data presentation. Z. Cao completed subsequent revisions of the manuscript. M. Mustafa and M. H. Mohd Isa supplied relevant literature for writing the manuscript, equally contributed to supervision, and assisted with proofreading and formatting the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics

According to Article 32 of the Measures for Ethical Review of Life Sciences and Medical Research Involving Humans, issued by the National Health Commission of China on February 18, 2023, research that does not cause harm to the human body, does not involve sensitive personal in-formation, or does not involve commercial interests can be exempted from ethical review. This study would not cause any mental injury to the participants, have any negative social impact, or affect the participants’ subsequent behaviours. In the procedure, the study recruited experts and residents over the age of 18, and the relevant vulnerable groups were strictly excluded from the sampling process. Therefore, in accordance with the regulations (Article 32 of Measures for Ethical Review of Life Sciences and Medical Research Involving Humans of China), this study falls under the category of “exempt from ethical review”. The study received an ethical exemption from the School of Art and Design, Wuhan University of Science and Technology. Application number: No. 10020250153SX. Nevertheless, as researchers, we felt that it was necessary to protect participants’ safety, privacy, and confidentiality. All research procedures were conducted following the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki and its revised version in 2024.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained in writing from all participants involved in this study. For the expert focus group participants, consent was collected via electronically signed informed consent forms prior to the interviews. The forms were distributed by the first author via email and returned with signatures. Consent was obtained by the research team from nine urban planning and design experts affiliated with four universities in China. The consent form explained the purpose of the research, the voluntary nature of participation, the procedure of the interviews, and their right to withdraw at any time. It also explicitly requested permission to record, analyze, and publish anonymized excerpts from the discussions. For the questionnaire respondents, informed consent was obtained through a written consent form presented at the beginning of the online survey. Before beginning the questionnaire, all respondents were required to read and agree to a digital consent statement to proceed. This statement clarified the purpose of the study, assured participants of their anonymity and confidentiality, and explained how the data would be stored and used. It also confirmed that participation was voluntary, and that respondents could exit the questionnaire at any point without penalty. The scope of consent covered participation in the study, use of anonymized data for academic analysis, and inclusion of aggregated findings in publications and presentations. This study did not involve any vulnerable populations such as minors, refugees, or patients. All participants were competent adults who voluntarily provided informed consent in accordance with ethical guidelines.

AI disclosure

The study used ChatGPT 4o in the experimental stimulus generation phase, and some of the images are displayed in Fig. 3 of this study. In addition, no other AI software was used for the other parts of the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cao, Z., Mao, Y., Mustafa, M. et al. Future cities imagined by ChatGPT-4o: human evaluation using importance-performance analysis. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 630 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04941-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04941-6