Abstract

Science funding is vital for driving national innovation and technology development. China’s science funding supports a growing number of researchers, and they form collaboration networks through common project experience. However, existing studies lack focus on the impact of collaboration networks based on common project experience on research output due to data limitations. To address this gap, we analyzed a sample of 43,271 science funding projects approved by the National Natural Science Foundation of China from 2009 to 2014. Collaboration networks were constructed based on principal investigators’ common project experience, and the centrality indicator was used to assess their ability to utilize these networks. Our findings revealed that centrality had a significant positive impact on project papers, citations, and efficiency, thus highlighting the role of such collaboration networks in promoting research output. However, the promotional effect varied; centrality had a stronger impact when investigators had project experience or worked on natural science research but weaker when projects were affiliated with top research institutions or involved foreign team members. These collaboration networks enhanced research output through improved relationships and larger teams. Moreover, they had a more significant impact on promoting English output than Chinese. This paper offers essential insights for optimizing science funding management from the perspectives of project experience, scientific field, institutional level, and international composition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Science funding is of paramount importance for enhancing a country’s competitiveness, technological progress, and economic development (Hu, 2020). In 2022, science funding in China amounted to 32.699 billion Chinese yuan, supporting 51,600 projectsFootnote 1. Similarly, science funding in the US reached 8.601 billion US dollars in the same year, funding 18,900 projectsFootnote 2. These substantial funding amounts and project numbers indicate the significance both China and the United States attach to science funding, as well as the size of the funded research community. Science funding projects are typically carried out in the form of teams, forming common project experience (CPE) when multiple researchers collaborate on the same project. This experience can evolve further into collaboration networks, involving a large number of researchers and ultimately influencing research output. However, unlike co-author relationships, CPE involves greater uncertainty, looser collaboration, a relatively weak foundation, and a more indirect impact on paper output. Given the widespread existence and high uncertainty of CPE, discussing the collaboration network based on it can significantly enhance research output. CPE offers two advantages over co-authorship: (i) in actual research groups, many collaborations among researchers do not always result in co-authored publications. However, daily interactions and discussions significantly contribute to their research outputs, particularly within the same project. In such cases, CPE more accurately captures the essence of collaboration, and (ii) co-authorship networks of PIs may include collaborations that are unrelated to their NSFC projects. Using co-authorship to construct networks may, therefore, overestimate the effect of the PI’s centrality on project outcomes.

Collaboration networks exert a significant impact on research output (Anderson & Richards-Shubik, 2022). As academic research specialization deepens, the demands on researchers’ capabilities continue to grow, making independent research more challenging. Nevertheless, collaboration offers an effective approach to overcoming individual cognitive limitations and bounded rationality (Li et al., 2013). Within collaboration networks, researchers share workloads, expertise, specific skills, equipment, and resources to achieve common goals (Bozeman & Corley, 2004; He et al., 2009). Furthermore, the group norms generated by collaboration networks have supervisory and motivating effects, encouraging researchers to invest more energy in their work (Bozeman et al., 2013; Hoekman et al., 2010). However, collaboration networks can also have negative consequences, as researchers invest considerable time and resources in maintaining connections within the network (Sinnewe et al., 2016). While a consensus view on the impact of collaboration networks on research output has not yet been reached, the proportion of collaboration papers is increasing in reality (Kong et al., 2019). Further in-depth discussions are required to fully understand the impact of collaboration networks on research output.

Social capital theory and resource dependence theory suggest that differences at both the individual and organizational-environmental levels may lead to variations in the impact of collaboration networks on research output (Hillman et al., 2009; Inkpen & Tsang, 2005). First, researchers with specific experience may efficiently utilize networks to find resources and collaborators due to their accumulated expertise and clearer search direction (Dahlander & McFarland, 2013). Second, language and cultural differences between foreign and domestic members, along with spatial distance, may escalate communication costs and weaken the resource-sharing function of the network (Aldieri et al., 2018). Third, natural science research demands more resources compared to social science research, making the resource acquisition function of collaboration networks more crucial in this scientific domain (Benz & Rossier, 2022). Fourth, top research institutions possess abundant resources, and their researchers are also highly capable, leading collaboration networks to provide them with relatively limited assistance (Zong & Zhang, 2019).

Additionally, collaboration networks influence research output through specific mechanisms. On the one hand, collaboration networks can strengthen the relationship bonds between researchers, leading to enhanced trust and reciprocity, reducing collaboration risks and transaction costs, and facilitating knowledge transfer (Liu et al., 2023). On the other hand, collaboration networks can expand the size of research teams, thereby optimizing individual workloads and enhancing team diversity, fostering new ideas (Yuan & Van Knippenberg, 2022). Finally, the impact of collaboration networks on the output of different language types varies. Chinese research institutions put more emphasis on English output in assessment, and English output itself has a broader readership than Chinese (Xu, 2020). However, the existing literature rarely addresses the relationship between collaboration networks and research output from the above perspective, potentially leading to a limited understanding of this relationship. Therefore, this paper addresses the research questions of whether the collaboration network constructed using CPE can enhance research output, the factors influencing the network’s role, and the underlying mechanisms of the collaboration network. This paper analyzes research output at the project level, offering a novel perspective compared to the individual-level focus of previous studies(Anderson & Richards-Shubik, 2022; Li et al., 2013). This distinction expands the research output literature by broadening the analysis scope. Additionally, while some studies have examined the impact of collaboration networks on research output, the direction of this effect remains inconclusive (He et al., 2009; Sinnewe et al., 2016). This paper provides new empirical evidence to resolve this ambiguity, demonstrating that collaboration networks have a significant positive impact on research outputs.

To address the above questions, we conducted the following research. Firstly, we utilized crawler technology to collect data on 43,271 approved projects from the website of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) from 2009 to 2014. We constructed CPE collaboration networks based on whether principal investigators (PIs) have participated in the same project. The PI refers to the individual responsible for managing the funded project. The PI oversees the project’s planning, organization, and implementation, serving as its leader and primary decision-maker. We calculated the network centrality index of the PI based on the network to assess their ability to utilize it for resource and collaborator searches. Secondly, we collected project output data from the Web of Science (WOS) and China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI). We developed three output indicators: the number of project papers, the citations of those papers, and the project data envelopment analysis (DEA) efficiency. This paper extends the applicability of variables from previous studies by incorporating novel data on PIs’ CPE and large-scale bibliometric statistics, validating the robustness of the variables, and providing large-scale empirical evidence for both the collaboration network and research output literature (Hu, 2020; Li et al., 2013). Thirdly, we examined the impact of PI centrality on various project output indicators and further investigated the variation of this effect in relation to project experience, scientific field, institutional level, and international composition, as well as two potential mechanisms: tie strength and team size. This paper emphasizes key characteristics of the NSFC, enabling a detailed examination of how the impact of PI collaboration networks on project research output varies across different conditions, an area that has received less attention in previous studies. Additionally, this analysis provides valuable insights for optimizing fund allocation strategies. Finally, we explored the influence of collaboration networks on research output across different language types.

This paper makes the following contributions: first, it utilizes researchers’ CPE to uncover the impact of a more common and uncertain collaboration network on research output in reality. In the context of increasing science funding, CPE is becoming more widespread. However, to the best of our knowledge, due to data limitations, few studies have utilized CPE to construct collaboration networks. This contribution extends the research on collaboration networks (Bozeman & Corley, 2004; He et al., 2009; Hoekman et al., 2010; Kim & Kim, 2020; Sinnewe et al., 2016).

Second, our study discusses the factors that strengthen and weaken the influence of collaboration networks and analyzes the mechanisms of collaboration networks, supplementing the lack of discussions in the existing literature on these aspects (Anderson & Richards-Shubik, 2022; Li et al., 2013). Project experience, scientific field, institutional level, and international composition can either strengthen or weaken the utility of collaboration networks, thereby affecting the assessment of the relationship between collaboration networks and research output. Tie strength and team size are directly affected by the collaboration network, helping us to open the black box of the relationship between the collaboration network and research output. In addition, compared to previous studies, the mechanism analysis in this article reveals two noteworthy findings. On the one hand, in large teams, higher centrality combined with stronger tie strength has a negative effect on project research output, a phenomenon not observed in smaller teams. On the other hand, the positive effect of PI centrality on project research output exhibits a nonlinear relationship with team size. Specifically, in smaller teams, the promotion effect of centrality on project output weakens as team size increases. However, this effect strengthens in larger teams as the team size grows.

Third, previous studies have seldom discussed the differences in the impact of collaboration networks on the output of different language types. This paper finds that English-language articles exhibit relatively higher quality, innovation, and influence. Therefore, the role of PI centrality in promoting research output is stronger for English-language publications. Within the context of China’s ongoing focus on research localization, discussions in this area can offer valuable insights for researchers in balancing the allocation of resources between international and domestic publications (Kwiek, 2020; Leydesdorff et al., 2019; Marginson, 2022; Xu, 2020; Zhang & Guo, 2017). Both international and domestic publications are of paramount importance, and finding a balance between the two is of great significance to the sustainable development of academia.

The rest of this article is structured as follows: Section 2 presents the literature review and research hypothesis. Section 3 describes the data and research methods. Section 4 discusses the impact of CPE collaboration networks on research output. Section 5 presents the heterogeneity analysis. Section 6 delves into mechanism analysis and further study. Section 7 provides the conclusion.

Literature review and hypothesis development

CPE collaboration networks and research output

Collaboration networks formed through different relationships have varying impacts on research output. Collaboration in the form of CPE is widespread, connecting researchers to create large and complex collaboration networks that significantly influence research output (Kardes et al., 2014). Based on CPE, these networks are more elusive and challenging to observe than co-authorship relationships, yet they are prevalent among researchers. The impact of the collaboration network built on the basis of CPE on research output is a more indirect process, operating from project to paper. In contrast, the collaboration network established through co-author relationships exerts a more direct effect on research output, operating from paper to paper (Anderson & Richards-Shubik, 2022). In the case of CPE-based networks, the foundation for collaboration between the two parties is weaker, introducing greater uncertainty regarding the production of papers. However, in networks established through co-author relationships, the two parties have already co-published papers, significantly reducing communication costs and increasing the likelihood of producing new papers. Evidently, the influence of the collaboration network is closely tied to the foundation of its formation. Nevertheless, due to data limitations, current studies predominantly rely on co-author relationships to construct networks (Ji et al., 2022; Krishen et al., 2021). Insufficient research on building collaboration networks based on CPE may lead to incomplete conclusions regarding collaboration networks.

With the increasing specialization of research, collaboration has become a prevalent practice in academia, contributing to forming collaboration networks that enhance research output (Bozeman & Corley, 2004; Katz & Martin, 1997). Collaborating researchers benefit from the overlap of expertise, facilitating skill enhancement. Furthermore, they engage in cross-validation and internal reviews of each other’s work before paper submission (Smith et al., 2021). Collaboration networks foster an environment for enhanced knowledge creation by integrating expertise and technologies from diverse sources. Additionally, the learning experience of acquiring skills and technologies from partners sets the foundation for future research activities, while social networks with partners provide valuable information and research opportunities (He et al., 2009). These networks also offer face-to-face communication opportunities, intensifying and diversifying language or other forms of interaction. Such opportunities facilitate the generation of a shared language, common values, and the transfer of knowledge that may be difficult to express verbally (Filieri et al., 2014; Hoekman et al., 2010).

Collaboration networks enable researchers to efficiently mobilize resources necessary for publications, serving as a basis for new funding and the initiation of further research. Thus, these networks help researchers surpass their cognitive and rational limitations, leading to more influential research outcomes (van Rijnsoever & Hessels, 2011). Within the network, valuable resources such as information and knowledge are exchanged through interactions, and the transfer process is optimized by minimizing redundancy (Li et al., 2013; Xu et al., 2014). Moreover, networks also serve to diminish opportunistic behavior among members by fostering a high level of trust, consequently reducing the monitoring costs associated with collaboration (Nahapiet & Ghoshal, 1998). Group norms within the network, such as exclusion and forgiveness, can influence individual behavior, promoting cooperation and improving research efficiency (Ali & Miller, 2016). Finally, several studies have shown that international collaboration positively influences research output. Researchers engaged in international collaborations tend to achieve significantly higher output levels compared to those without such partnerships (Kwiek, 2020). Furthermore, international collaborations can greatly enhance the impact of articles and help establish global leadership in various research fields (Leydesdorff et al., 2019; Zhang & Guo, 2017).

However, collaboration networks can also impede research output (Liang & Liu, 2018). Identifying and evaluating partners in the early stages, formulating contracts to manage collaboration and distribute expected results, coordinating researchers in the mid-term, monitoring work progress, and evaluating the quality of research results in the later stages are all costs associated with collaboration networks (He et al., 2009; Sinnewe et al., 2016). While the network provides individuals with more connections, it can significantly increase the cost of maintaining these connections. Excessive connections may restrict an individual’s vision and hinder communication with other external organizations (Inkpen & Tsang, 2005). Moreover, the strong group norms and mutual identity generated by collaboration networks may also restrict information openness and communication, potentially leading to collective blindness, which can have serious negative effects (Inkpen & Tsang, 2016). In research collaboration specific to the form of co-authors, costs such as nominal authorship and ghostwriting may be incurred. Furthermore, some researchers adopt these practices to increase their influence but refuse to take responsibility for the published articles (Bozeman et al., 2013). Another common form of research collaboration is inbreeding, which has been found to be linked to lower output and less openness to non-inbred researchers (Horta et al., 2010).

Based on the above analysis, we hypothesized that the CPE collaboration network can enhance research output. On the one hand, it facilitates the flow of resources, such as information and knowledge, among researchers; on the other hand, it fosters a high level of trust and inhibits opportunistic behavior. Although collaboration networks increase the cost of maintaining relationships for researchers, the benefits they offer are substantial. Considering the combined effect of the two, the collaboration network generally has a positive impact. Therefore, we propose hypothesis 1.

H1: CPE collaboration networks will enhance research output.

Heterogeneity of collaboration networks

Social capital theory posits that differences at the individual level can influence one’s network position and accumulation of social capital (Inkpen & Tsang, 2005). Researchers with extensive project experience can effectively utilize the network. With sufficient project experience, the researcher can conduct targeted searches for resources within the collaboration network in a more targeted manner. Simultaneously, the researcher can more effectively assess the potential of partners and projects, selecting the most suitable collaborators and projects from the network to minimize transaction costs associated with collaboration. Furthermore, as project experience increases, resources start to accumulate for these senior and highly regarded researchers (Dahlander & McFarland, 2013), expanding their collaboration network and providing them with a wider range of options. Nonetheless, when the researcher lacks sufficient project experience, their ability to identify suitable collaborators and projects remains underdeveloped. Moreover, the multitude of opportunities presented by the collaboration network may consume significant time and energy, disrupting the researcher’s normal research rhythm and hindering output.

The presence of foreign members can elevate the communication cost of the collaboration network. Firstly, language differences increase communication costs and can impact the enthusiasm of members both at home and abroad, hindering the timely exchange of ideas (Aldieri et al., 2018). Secondly, cultural differences make it more challenging to establish cohesive group norms, as members from different cultural backgrounds may have contrasting levels of acceptance toward the same working model. Lastly, spatial distance hinders the seamless integration of foreign members into the team and can even lead to a sense of alienation. Some studies suggest that researchers from countries with lower levels of scientific research may engage in free-riding behavior by leveraging international collaborations to co-publish with researchers from countries with higher research capacities, thereby increasing their publication output (Kim & Kim, 2020). In contrast, when the team consists of domestic members only, communication costs are reduced due to the shared language. Moreover, members sharing the same cultural background tend to have a closer level of acceptance toward the work model, enhancing the likelihood of fostering strong group norms. Additionally, the increased opportunities for face-to-face communication lead to higher team integration among the members.

Resource dependence theory suggests that changes at the organizational and environmental level can impact a team’s access to essential external resources (Hillman et al., 2009). Collaboration networks have varying effects on projects in different scientific fields. Natural sciences typically involve experimentation, necessitating significant resource consumption, including equipment, instruments, materials, and more (Benz & Rossier, 2022). In such cases, the researcher’s collaboration network can assist in resource acquisition and integration. Simultaneously, the research methods and evaluation of results in natural sciences tend to be more objective, and the use of common standards can mitigate debates among researchers regarding correctness or quality, fostering academic exchange. In contrast, social sciences usually do not rely on experimentation, substantially reducing expenses and diminishing the impact of network resource availability. Moreover, social science tends to be more subjective, with diverse research methods and evaluation systems across different institutions, making comparisons of superiority challenging. The connections formed by collaboration networks fail to foster academic exchanges in such cases and can also increase communication costs among researchers.

Researchers’ dependence on the collaboration network can decrease with abundant institutional resources. General research institutions often have limited resources and lack regular activities such as forums, seminars, and lectures. In such cases, the collaboration network offers researchers valuable opportunities to communicate and engage with other researchers in these institutions. The collaboration norms established within the network can enhance communication efficiency and encourage participation from all parties in knowledge exchange (Arregle et al., 2007). Moreover, the sense of identity fostered by the collaboration network can enhance communication opportunities and promote more frequent collaboration (Tsai et al., 2014). However, in top research institutions, abundant research resources and strong researchers make the collaboration network’s assistance relatively limited. Furthermore, the presence of numerous collaborators attracted by the reputation of top research institutions increases the screening cost for the researcher. Selecting an unsuitable collaborator or project can impede their ongoing research progress. Based on the analysis above, we propose Hypothesis 2.1 and Hypothesis 2.2.

H2.1: The promotion effect of the collaboration network on research output is stronger when the researcher has more project experience or when the project pertains to natural science research.

H2.2: The promotion effect of the collaboration network on research output is weaker when the host institution of a project is a top research institution or the project team includes foreign members.

Mechanism of collaboration networks

The degree to which a researcher utilizes collaboration networks directly impacts the strength of their ties in the network. In social networks, the relationships between nodes are typically categorized into weak ties and strong ties based on their strength (Granovetter, 1973). Weak ties are characterized by their short duration, infrequent interactions, and low emotional intimacy. They facilitate access to diverse social circles and enhance the potential for acquiring varied information (Lyu et al., 2019). Conversely, strong ties entail long-term, frequent interactions and high emotional intimacy. They offer opportunities for access and trust among like-minded individuals. Researchers with aligned goals establish connections within a research collaboration network to foster long-term partnerships. Strong ties are associated with dense network clusters, whereas weak ties serve as potential bridges between these clusters. Furthermore, strong ties foster increased trust and reciprocity, thereby mitigating the costs and risks involved in new collaborations. The combination of higher trust and reduced risk in these strong-tie relationships, in turn, facilitates knowledge transfer and creation (Guan et al., 2015; Wang, 2016). While weak ties encourage the collision and generation of novel ideas, scientific research ultimately requires a high level of knowledge intensity. Thus, stable and long-lasting strong ties are more favorable for fostering cooperative development.

Collaboration networks directly influence the size of research project teams. In general, the researcher’s increased connections within the network enhance the possibility of contacting potential collaborators and selecting suitable individuals to join their research team (Yuan & Van Knippenberg, 2022). With an increasing team size, the workload assigned to individual researchers decreases, thereby expediting the output of research results. Moreover, enlarging the team size enhances the diversity of team members’ backgrounds, fostering the generation of new ideas. However, expanding the team size may also present disadvantages, including heightened communication costs for the researcher and the potential for opportunistic behavior among team members. Despite these potential issues, we argue that the internal structure of the researcher-composed team remains relatively flat, which does not significantly elevate the management costs for the researcher. Additionally, opportunistic behavior yields limited benefits to researchers, as they strive to uphold their reputation and are unwilling to include individuals who have not contributed to their articles. Based on the above analysis, we propose Hypothesis 3.

H3: The collaboration network enhances research output by improving the researcher’s tie strength and expanding the project team size.

Analytical framework

This paper presents an analytical framework as depicted in Fig. 1. Firstly, it examines the impact of collaboration networks formed through CPE on research output (hypothesis 1). While collaboration networks may entail transaction costs, they predominantly facilitate resource sharing, leading to an overall positive impact. Secondly, the study delves into the heterogeneity of this impact on research output (hypotheses 2.1 and 2.2). Project experience enhances researchers’ efficiency in utilizing collaboration networks, and there is a heightened demand for resource-sharing functionalities in natural science research. However, the resource-rich top research institutions may diminish the reliance on collaboration networks for resource sharing, and the involvement of foreign members might increase communication costs within the networks. Thirdly, the paper explores how CPE collaboration networks influence research output (hypothesis 3). One key mechanism is the strength of researchers’ ties, and another is the size of project teams.

Data and methodology

NSFC

NSFC was established on February 14, 1986, as a vice-ministerial unit under the Ministry of Science and Technology of China. Its primary role is to manage natural science funding in compliance with the law. The NSFC is responsible for organizing and implementing funding plans, conducting project setting and review, granting project approval, and providing supervision. The NSFC funds scientific research in 9 domains: mathematics and physical science, chemical science, life science, earth science, engineering and material science, information science, management science, health science, and interdisciplinary science. There are 17 types of funding offered by the NSFC, with the general program and youth science fund encompassing the broadest range and receiving the highest amount of funding. As depicted in Fig. 2, the NSFC’s funded projects rose from 40,700 in 2015 to 51,600 in 2022, with the annual funding amount increasing from 21.884 billion Chinese yuan in 2015 to 32.699 billion Chinese yuan in 2022Footnote 3.

The selection of the NSFC as the data source is primarily based on three key considerations. First, natural science funding has extensive coverage and involves numerous researchers. Second, research institutions and researchers highly value natural science funding, and securing funding projects has become a critical criterion for evaluating the research capabilities of institutions and individuals. Third, the funding projects typically have long durations, usually 3–5 years, fostering long-term CPE, which in turn increases the likelihood of real collaborations among researchers.

Sample

We collected three types of data for this study: science fund project data, records of projects in which the project leader has participated, and project paper output data. Initially, we obtained data on 43,271 science funding projects approved by NSFC from 2009 to 2014. This dataset includes information such as funding amount, funding period, number of project members, disciplines, project types, host institution, and other pertinent details. We selected 2009 as the starting year since WOS began labeling papers funded by NSFC in July 2008. The cut-off year was set as 2014 due to the delayed disclosure of project information by NSFC. We found that most of the project information approved in and after 2015 had not been disclosed during the collection process. Subsequently, we obtained records of the projects in which the PI has participated from NSFC, forming the basis for constructing the PI’s CPE collaboration network. The 43,271 projects examined in this study involved 36,706 researchers, collectively participating in 194,039 projects during or before 2014. Lastly, we acquired the paper output data for the projects in both English and Chinese languages from the WOS and CNKI, respectively. We collected 436,772 English articles and 407,285 Chinese articles funded by the 43,271 projects, along with their corresponding citations until 2021.

The final sample consists of 43,271 funding project observations. We winsorized all the continuous variables at the 1% and 99% levels to make sure the sample followed a normal distribution.

Variables

Independent variables

The construction of the CPE collaboration network involves a yearly process. It starts by selecting all PIs from the projects within a specific year and filtering their project participation up to that year. This process results in a researcher-project matrix, with rows representing researcher IDs and columns representing project IDs. A value of 1 is assigned at the intersection of rows and columns if the PI participated in the project; otherwise, it is marked as 0. The researcher-project matrix is then transposed to create a project-researcher matrix. Multiplying this matrix with the researcher-project matrix generates a researcher-researcher matrix, where rows and columns represent researcher IDs, and values at the intersections indicate collaboration counts between researchers. To calculate the independent variable index, all diagonal elements in the researcher-researcher matrix are set to 0. The resulting researcher-researcher matrix is imported into Pajek software for visualization. Figure 3 displays the CPE collaboration network of PIs from 2009 to 2014. Each dot represents a PI, and connections between dots signify their participation in the same project. The dot size reflects the frequency of collaboration with other PIs. The network exhibits increasing node density from 2009 to 2011, indicating a growing number of PIs joining the network. From 2012 to 2014, the node density stabilizes, but the number of larger dots increases, suggesting the emergence of several highly productive researchers during this period. It is important to note that the NSFC project regulations do not restrict PIs from participating in multiple projects simultaneouslyFootnote 4. In the original data for this paper, there are numerous instances of PIs participating in multiple programs within the same year.

This paper aims to explore the influence of collaboration networks formed through researchers’ CPE on the research output of the projects they lead. To achieve this objective, it is necessary to use indicators that can assess individuals’ resource acquisition capacity within the network. The centrality index, derived from social network theory, is well-suited for this purpose as it effectively captures the connections among individuals within the network (Li et al., 2013). Centrality is closely linked to an individual’s potential ability, influence, and reputation. Existing literature commonly employs three types of centrality indicators (Borgatti, 2005; Freeman, 1978):

(i) Degree centrality. It represents the number of connections between a focal node and other nodes in the network. In our context, it directly measures the number of collaborations with other researchers.

Where dp represents the number of direct connections PI p has, n represents the total number of nodes in the network.

(ii) Betweenness centrality. It is defined as the ratio of the number of shortest paths between pairs of nodes that include node p to the total number of shortest paths between pairs of nodes. This measure assigns higher values to researchers who bridge different clusters within the network. It indicates that individuals have more influence if other researchers rely on them to connect with one another.

Where x(p) qr is the shortest path between PI q and PI r on which PI p lies, xqr is the shortest path between PI q and PI r with or without PI p.

(iii) Closeness centrality. It is defined as the inverse of the sum of all shortest distances between a given node and other nodes within the network. In our study, it indicates the proximity of a researcher to all other researchers in the network, whether directly or indirectly. Researchers with a high closeness centrality demonstrate a greater ability to access or acquire resources possessed by others in the network.

Where gpq represents the length of the shortest path between PI p and PI q.

All three measures of centrality hold significance in various contexts, albeit with varying interpretations. Generally, individuals with high centrality possess broader, deeper, more focused, and extensive approaches to acquiring and disseminating information, as well as influencing others. To facilitate comparisons among individuals, we rank the centrality of each individual in each year and assign a percentile value ranging from 1 to 100. Subsequently, we calculate the average of the three percentile values for each individual in each year to determine their annual comprehensive centrality index (Fogel et al., 2021).

Dependent variables

Since papers constitute the primary output of NSFC projects, we employ paper data to construct indicators for evaluating project output (Hu, 2020; Yu et al., 2022). The first indicator, TNum, quantifies the number of papers produced by the project. It reflects the total number of papers funded by the project, sourced from WOS and CNKI. We select these databases for data collection due to their authoritative status in cataloging English and Chinese papers, respectively. Additionally, they include project information for funded papers, facilitating the matching of papers to specific projects.

Given the varying quality of each article, we developed a second output indicator based on the number of citations an article has received. This second indicator, termed TQuo, quantifies the citations accrued by project papers. It denotes the total number of citations garnered by articles funded through the project. Considering that older articles typically accumulate more citations, we adjusted for this by dividing the number of citations of each article by the number of years since its publication (calculated as 2021 minus the publication year, with 2021 being the year in which we collected the citation data). We then averaged these adjusted citation counts and summed them up.

The third indicator, denoted as Vrs, quantifies the efficiency and is computed using DEA (Amara et al., 2020). The calculation of Vrs involves treating a single project as the decision-making unit, with its funding amount, total number of project members, and project duration serving as input indicators, as well as the number of project papers and the total citations of project papers as output indicators. The project’s output-input efficiency value is obtained by calculating the ratio of the weighted output to the weighted input and comparing it with the maximum efficiency value among all projects in the current year. An optimization problem is formulated and solved to obtain a weight matrix used to calculate the project’s DEA efficiency. The DEA efficiency of a project is a relative measure indicating how the project’s output-input ratio relates to the maximum output-input ratio achieved in the given year, thus ranging from 0 to 1. As funding projects typically strive to maximize research outcomes based on a range of inputs (e.g., funds, personnel, and time), this paper adopts an output-oriented DEA model. This article employs the BCC model to calculate DEA efficiency, as the BCC model assumes variable returns to scale. In practice, returns to scale often fluctuate with changes in input levels, making the BCC model a more appropriate choice for evaluating the efficiency of fund projects (Banker et al., 1984).

Analytical approach

To test hypothesis 1, we employ the following fixed effect model:

Subscript i represents the project, p stands for the researcher, and t stands for the year the project started. The dependent variable Y includes the number of project papers, citations of project papers, and project DEA efficiency (as defined in 3.3.2). Cen is an independent variable, indicating the centrality of the PI of project i in the current year’s collaboration network (as defined in 3.3.1). Tit represents the professional title of researcher p in year t, with 1 for assistant professor, 2 for associate professor, and 3 for professor. Fund represents the funding amount of project i. Time represents the funding period of project i. WHum represents the team size of project i. Additionally, we controlled for four fixed effects: project start year, discipline type, funding type, and host institution. Controlling for fixed effects related to discipline type can help mitigate the influence of discipline on paper citations. The regressions were performed with cluster-robust standard errors at the host institution level.

To test hypotheses 2.1 and 2.2, we introduce additional adjustment variables:

Adj comprises a set of adjustment variables, including Exper, Natu, Top, and Fore. Exper is a binary variable representing project experience. It takes the value 1 if PI p has previously led an NSFC project before the start year of the current project and 0 otherwise. Natu is a binary variable indicating whether project i belongs to natural science. It takes the value 1 if the project falls under natural science and 0 otherwise. Top is a binary variable representing whether the host institution of project i affiliates with a top institution. It takes the value 1 if the host institution belongs to the 985 Project or the Chinese Academy of Sciences and 0 otherwise. Fore is a binary variable indicating the presence of foreign members in the project team. It takes the value 1 if there are foreign members and 0 otherwise. The definitions of the other variables remain the same as in model (5).

For hypothesis 3, we replaced the dependent variables in the model (5) with the PI’s tie strength (TieStrength) and the team size (WHum). TieStrength is calculated by dividing the number of collaborations the PI engages in during the year by the number of collaborators. A higher ratio indicates a stronger relationship between the PI and others (Liu et al., 2023). WHum represents the total number of members of the project team.

The impact of CPE collaboration networks on research output

Descriptive statistics

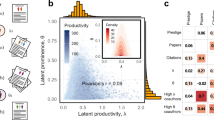

The results presented in Table 1 deviate from previous studies. The average number of project papers (TNum) is 17.170, slightly surpassing the count of 12.830 reported by Hu (2020). This disparity could be attributed to the different periods considered; Hu (2020) covered project approvals in 2010–2011, while this article examines the period of 2009–2014, suggesting an increase in individual project paper outputs over time. The average citations of project papers (TQuo) amount to 328.117, implying that, on average, a single paper funded by the project has received 19.110 citations by 2021 (328.117/17.170). The average value of project DEA efficiency (Vrs) is 22.257, which is lower than the average of 54.265 reported by Amara et al. (2020) for the efficiency of 202 management scholars. While the Vrs values originally ranged from 0 to 1, directly using them in this form would result in coefficients that were too small, making analysis inconvenient. Therefore, we multiplied the Vrs values by 100, making the coefficients easier to interpret without affecting the regression results. The wide range in efficiency may stem from two factors. First, the varying abilities of PIs likely contribute to significant differences in the input-output ratio across projects. Second, inherent differences in input-output efficiency exist between disciplines. For instance, the average output in engineering and materials science is typically much higher than in management-related disciplines. The mean value of Cen is 29.654, signifying a low degree of connection among the PIs in the collaboration network and suggesting a relatively sparse network. Furthermore, the average value of the PI’s professional title is 2.645, indicating that a majority of the PIs hold the title of professor.

Basic estimation

The results in Table 2 demonstrate a significant positive impact of the PI’s centrality on research output, thus verifying Hypothesis 1. In column 1, the coefficient of Cen is statistically significant at the 1% level, suggesting that a 1% increase in the network centrality of the PI leads to a 0.018 increase in the number of project papers. Similarly, in column 2, the coefficient of Cen is statistically significant at the 1% level, indicating that a 1% increase in the centrality of the PI results in a 1.056 times increase in the citations of project papers. Likewise, in column 3, the coefficient of Cen remains statistically significant at the 1% level, suggesting that a 1% increase in the centrality of the PI leads to a 0.027 increase in the DEA efficiency of the project. These findings align with the findings of Li et al. (2013), providing further evidence that collaboration networks play a role in fostering research output. Moreover, they highlight the positive significance of CPE.

The regression results of the control variables indicate a positive relationship between the researcher’s professional title, project funding, funding period, team size, and project output. Specifically, the coefficients of Tit are significantly positive in all three columns, suggesting a positive association between the researcher’s professional title and the project output. These results align with the findings of Amara et al. (2020). Similarly, the coefficients of Fund are significant in columns 1–3, indicating a positive relationship between the amount of project funding and the quantity and quality of produced papers. These findings are consistent with the findings of Hu (2020). Moreover, the coefficient of Time is significantly positive in column 1. It exhibits a near 10% statistical significance in column 2, suggesting a positive correlation between the funding period and the quantity and quality of project output. Likewise, the coefficients of WHum are significantly positive in columns 1–3, indicating a positive relationship between the project team size and the research output.

Robust test

When discussing the impact of collaboration networks on research output, it is crucial to consider the potential presence of uncontrolled variables that may introduce a non-random distribution of the PI’s centrality in the sample. These uncontrolled variables can also influence research output, leading to a self-selection problem in the model. To address this issue, we employ the propensity score matching method (Fan et al., 2022). Firstly, the annual median of the centrality variable is calculated, and a dummy variable called DumyCen is created. The dummy variable takes a value of 1 if the centrality of a sample is greater than the median and 0 otherwise. Secondly, samples with a DumyCen value of 1 are matched with those having a DumyCen value of 0 by year, considering covariates such as the PI’s title, funding amount, funding period, discipline type, project type, and host institution. The matching process utilizes a 1:1 proximity match method. Thirdly, the newly matched samples undergo retesting.

The results in Table 3 demonstrate the robustness of the findings after employing the matching method to process the samples. In column 1, the coefficient of DumyCen is statistically significant at the 1% level, suggesting that researchers with higher centrality produce an average of 1.153 more papers compared to those with lower centrality. Similarly, in column 2, the coefficient of DumyCen is significantly positive at the 1% level, indicating that researchers with higher centrality receive an average of 64.605 more citations than those with lower centrality. Additionally, in column 3, the coefficient of DumyCen remains significantly positive, implying that researchers with higher centrality exhibit an average efficiency that is 1.728 percentage points higher than those with lower centrality.

A comparison of the coefficient of DumyCen in columns 1–3 with the means of TNum, TQuo, and Vrs reveals that the number of project papers, the citations of project papers, and the DEA efficiency for PIs with higher network centrality are 6.72% (1.153/17.170), 19.69% (64.605/328.117), and 7.76% (1.728/22.257) higher, respectively, than those for PIs with lower network centrality. The regression results after propensity score matching are consistent with the basic findings and partially mitigate the endogeneity issue that may arise from self-selection, indicating that the impact of the PI’s network centrality on project research output is robust.

The greater the research output of a project, the more likely it is to attract collaborators to work with the PI, thereby increasing the PI’s centrality and potentially leading to a reverse causality issue. While the centrality measure of the PI in this study is based on the collaboration network data from the year prior to the publication year of the project’s paper, which helps mitigate the reverse causality concern to some extent, we further apply the instrumental variable method to address this issue more robustly (Yu et al., 2022). The instrumental variables must meet the requirements of correlation and exclusivity. Accordingly, this study selects the average host institution centrality (IvCen) as the instrumental variable. The mean centrality value exhibits a strong correlation with the centrality of the PI. Moreover, it primarily impacts research output through the pathway influencing PI centrality, thus fulfilling the exclusivity condition.

The findings in Table 4 demonstrate the robustness of the results after retesting with the instrumental variable method. The Kleibergen-Paap F value of 145.505 exceeds the 10% critical value (16.38) suggested by Stock-Yogo, indicating a minimal concern regarding weak instrumental variables. The coefficients of Cen in columns 1–3 are all significantly positive at the 1% level, suggesting that using the average centrality of the host institution as an instrumental variable for the PI’s network centrality confirms the robustness of its role in promoting research output. Moreover, the coefficients of Cen are similar to those in Table 2, suggesting that the basic regression results are less influenced by the reverse causality issue. The R2 in Table 4 is significantly lower than in Table 2. which can be attributed to the fact that the instrumental variable is at the host institution level, where variability is considerably lower than at the PI level, leading to a significant reduction in their explanatory power for the research output indicators.

Heterogeneity discussion of CPE collaboration networks

Social capital theory posits that individual factors, such as the PI’s experience and team members’ backgrounds, influence their position within the CPE network and the accumulation of social capital (Inkpen & Tsang, 2005). Resource dependence theory suggests that organizational and environmental factors, such as the project’s scientific field and the level of the host institution, impact the team’s access to necessary external resources (Hillman et al., 2009). Therefore, analyzing the effect of the PI’s centrality in the CPE network on research output from both individual and organizational perspectives allows for a better understanding of how centrality yields heterogeneous effects in different contexts.

Individual factors

The first individual level factor influencing heterogeneity is the PI’s project experience. Researchers with more experience in a specific field are also more efficient at resource search and allocation. In a CPE collaboration network, experienced researchers benefit in two ways: their familiarity with project management reduces time spent on non-research tasks; their prior leadership experience enables quicker resource identification and collaborator selection. Furthermore, the experience can lead to a Matthew effect, concentrating resources on these researchers and expanding their collaboration network (Hu, 2020). We introduce the Exper variable to examine how project experience influences the relationship between collaboration network centrality and research output. If PI p of project i has previously led an NSFC project before year t, the Exper variable is set to 1; otherwise, it is set to 0.

The results in Table 5 indicate that the impact of CPE collaboration networks on research output is stronger for researchers with prior project experience. In column 1, the coefficients for the cross-product term (Cen*Expert) and Cen are significantly positive, suggesting that an increase in the centrality of experienced researchers leads to a greater rise in the number of project papers compared to those without prior project experience. In column 2, a similar positive effect is observed, with experienced researchers showing a stronger increase in project paper citations as their network centrality rises. Column 3 confirms that project experience enhances the impact of researcher network centrality on project efficiency.

The team’s international composition is the second individual level factor contributing to heterogeneity. Foreign team members bring differences in language, culture, and cognitive approaches, which may affect collaboration network effectiveness. While NSFC projects primarily comprise domestic members, including foreign members can increase communication costs and hinder information flow due to language barriers (Aldieri et al., 2018). Cultural differences may also impede integration and the development of positive group norms. In contrast, teams with more domestic members benefit from enhanced communication efficiency, better transfer of tacit knowledge, and smoother integration and alignment in group norms. To examine how team international composition influences the relationship between collaboration networks and research output, we introduce a binary variable, Fore, which equals 1 if the team includes foreign members and 0 otherwise.

The results in Table 6 show that the presence of foreign members in the team reduces the positive impact of CPE collaboration networks on research output. In column 1, the positive coefficient of Cen and the negative coefficient for the interaction term between Cen and Fore indicate that an increase in centrality leads to fewer project papers when foreign members are included in the team. In column 3, the significantly positive coefficient of Cen and the negative interaction term imply that the positive impact of centrality on research output is nearly neutralized when the team includes foreign members.

Organizational and environmental factors

The project’s scientific field is the first organizational and environmental factor contributing to heterogeneity. Natural and social sciences research differs significantly regarding resource requirements and evaluation criteria. Natural science research often involves high-cost resources, such as expensive instruments and large quantities of consumables (Benz & Rossier, 2022), making the resource-sharing effect of collaboration networks particularly important. These networks enable researchers to share costly equipment, improving resource efficiency. Additionally, natural science achievements are evaluated more objectively, facilitating smoother knowledge exchange. In contrast, social science research requires fewer resources, and the resource-sharing effect is less pronounced. Moreover, the more diverse evaluation criteria in social sciences can lead to debates, hindering communication efficiency and research progress. We construct a dummy variable, Natu, to examine how the scientific field influences the relationship between collaboration networks and research output. When project i is a chemistry project, it takes the value of 1, representing natural sciences. When project i is an economics and management project, it takes the value of 0, representing social sciences.

The results in Table 7 show that CPE collaboration networks have a stronger impact on research output in natural science projects. In column 1, the positive coefficients of Cen and the interaction term Cen*Expert indicate that the effect of PI centrality on the number of project papers is more pronounced in natural science projects than in social science projects. In column 2, a similar pattern is observed for project citations, with centrality having a greater impact on natural science projects. Column 3 confirms that PI centrality more significantly promotes project efficiency in natural science projects.

The second organizational and environmental factor contributing to heterogeneity analyzed in this paper is the level of the host institution. Institutions differ significantly in research resources and researchers’ capabilities. In China, top-tier institutions like 985 projectFootnote 5 universities and the Chinese Academy of SciencesFootnote 6 receive substantial government funding and have more stringent recruitment standards, resulting in researchers with higher qualifications and stronger research capabilities (Zong & Zhang, 2019). As a result, researchers in these institutions have less need to search for resources or build collaboration networks, as their institutions already provide ample resources. In contrast, researchers in general institutions, facing resource constraints and lower capabilities, rely more on collaboration networks to access resources and connect with proficient collaborators. These networks’ collaboration norms and sense of identity also motivate researchers to invest more in their scientific work. To examine the impact of institutional level on the relationship between collaboration networks and research output, we introduce the Top variable, assigning a value of 1 when the project’s host institution belongs to 985 project universities or the Chinese Academy of Sciences and 0 otherwise.

The results in Table 8 show that CPE collaboration networks have a weaker impact on research output in top institutions. In column 1, the positive coefficient of Cen and the negative coefficient of the interaction term between Cen and Top suggest that PI centrality has a weaker effect on project papers in top institutions compared to general institutions. In column 3, the positive effect of PI centrality on project efficiency is weaker in top institutions, as indicated by the negative interaction term between Cen and Top.

Mechanism analysis and further studies

Tie strength

Within the network, nodes form both strong and weak ties. Nodes with strong ties exhibit higher interaction frequency and engage in more profound collaborations. Additionally, strong ties foster trust and reciprocity, which mitigate the risks and costs associated with new collaborations, thereby facilitating the exchange and interaction of knowledge (Liu et al., 2023). On the other hand, weak ties offer greater collaboration diversification, serving as bridges that connect diverse groups within the network and foster the integration of different fields (Lyu et al., 2019). While weak ties may facilitate the cross-pollination of ideas across fields, they encounter challenges during actual implementation. Scientific research demands a high knowledge density and requires frequent discussions and communication during collaborations. Therefore, strong ties play a crucial role and significantly contribute to the development of subsequent projects. To investigate the impact of tie strength on research output within collaboration networks, we computed the tie strength of PI p in year t. Specifically, we determine the tie strength by dividing the number of collaborations the PI engages in with others in the year by the total number of individuals the PI collaborates with. A higher ratio indicates a stronger relationship between the PI and others. We introduced the following model to test the mediating effect of tie strength as a mediating variable.

The results in Table 9 indicate that PI centrality influences the number of project papers and project output efficiency through tie strength. In column 1, the coefficient of Cen is significantly positive, suggesting that PI centrality has a significant positive effect on tie strength. In columns 2–4, TieStrength is added as an independent variable. The coefficients of PI centrality remain significantly positive but are reduced compared to the baseline regression results in Table 2. However, the coefficient of TieStrength is significantly positive only in columns 2 and 4, and only these columns pass the Sobel test, indicating that tie strength mediates the relationship between PI centrality and the number of project papers and project output efficiency. However, it does not mediate the relationship between PI centrality and the citations of project papers, which could be because citations rely more on factors such as the paper’s innovation, cutting-edge research, and the attention drawn to the research topic, which may not be directly related to tie strength.

We hypothesized that the effect of tie strength on the relationship between PI centrality and project output varies significantly with team size. In large teams, PIs with high tie strength and centrality often take on more communication and coordination tasks, leading other members to become overly dependent on the leader. This dependence can stifle the independence and innovation of team members, ultimately reducing the team’s overall innovation capacity. Additionally, PIs with high tie strength and centrality typically serve as information hubs in larger teams. They are more susceptible to information overload, which can heighten the risk of conflicts during decision-making, exacerbate differences in opinion, and create communication barriers. These factors collectively lead to research output falling short of expectations. To test this inference, we divided the sample into larger and smaller groups based on team size and introduced an empirical model with an interaction term between centrality and tie strength to conduct group testing. When the size of the project team exceeds the annual median, it is classified into the larger team group. Otherwise, it is categorized into the smaller team group.

The results in Table 10 show that when team size is large, the interaction between PI tie strength and PI centrality negatively impacts research output, consistent with our inference. In column 1, the interaction term (Cen*TieStrength) coefficient is significantly negative, while it is not significant in column 2. The p value of the coefficient difference test between groups is 0.010, indicating that the coefficient difference is significant. Therefore, columns 1 and 2 suggest that when team size is large, higher tie strength interacting with centrality may negatively affect the number of project papers. The coefficient of the interaction term in column 3 is significantly negative at the 10% level, whereas it is not significant in column 4. The p value of the coefficient difference test between groups is 0.080, indicating that the coefficient difference is significant. Thus, columns 3 and 4 indicate that when team size is large, higher tie strength interacting with centrality may have a negative impact on the citations of project papers. In column 5, the coefficient of the interaction term is significantly negative, while it is not significant in column 6. The p value of the coefficient difference test between groups is 0.000, confirming that the coefficient difference is significant. Therefore, columns 5 and 6 demonstrate that higher tie strength and centrality may negatively affect project output efficiency when team size is large.

Team size

The collaboration network is closely tied to the size of the project team. In general, researchers with higher centrality have greater access to collaborations, increasing the likelihood of selecting suitable partners (Yuan & Van Knippenberg, 2022). Increasing team size can further alleviate individual workloads and expedite research output. Additionally, the continuous inclusion of new members can enhance the diversity of team members’ backgrounds, thereby facilitating the exploration of new research directions. However, the increase in team size also brings disadvantages, including increased management complexity and the potential for exacerbated free-riding behavior among some members. Nevertheless, scientific research teams typically have a relatively flat organizational structure, and the associated increase in management complexity resulting from an expanded team size is relatively minimal. Furthermore, once an article is published, it becomes a lifelong accomplishment for the researcher. Due to reputational considerations, most researchers handle instances of free-riding behavior by others with care. To investigate the impact of collaboration networks on research output through team size, we consider the number of project members as the dependent variable. It should be noted here that the issue of reverse causality between PI centrality and team size is relatively minor. On the one hand, when PIs can engage in multiple projects within the same year, their network centrality is less influenced by team size. On the other hand, when constructing the collaboration network for each year, we incorporate not only each PI’s project experience from the current year but also their experience from previous years, which further mitigates the impact of team size on the collaboration network. We introduced the following model to test the mediating effect of team size as a mediating variable.

The results in Table 11 demonstrate that PI centrality influences research output through team size. The coefficient of Cen in column 1 is significantly positive at the 1% level, indicating that as PI centrality increases, team size also increases. When team size is added to the model as an independent variable, the coefficients of Cen in columns 2–4 remain significantly positive. However, compared to the centrality coefficients in Table 2, they are reduced. Additionally, the coefficients of WHum in columns 2–4 are all significantly positive, and each passes the Sobel test. These results indicate that team size mediates the relationship between PI centrality and the number of project papers, citations, and project output efficiency.

We propose the hypothesis that the impact of PI centrality on research output changes nonlinearly as team size expands. When the team size is small, increasing the team size weakens the impact of PI centrality on research output. This is because, with a smaller team, the PI can easily manage the team’s overall dynamics, coordinate tasks, and foster innovation. However, as the team expands, the complexity of communication and management increases, making it difficult for the PI to effectively oversee all members, which diminishes the utility of PI centrality. Once the team reaches a certain critical size, structural and managerial changes may occur. For instance, the team might be reorganized into smaller sub-teams with clearer task allocation and role division. This allows the PI to focus on key decisions while delegating the management of routine tasks. In this scenario, the hierarchical structure enhances management and innovation, leading to a recovery, or even an increase, in the utility of PI centrality as the team continues to grow. To verify this hypothesis, we construct the following model.

WHumSqu represents the quadratic term of WHum, and the definitions of other variables remain consistent with the baseline model. If the coefficient of β3 is negative and significant, and the coefficient of β5 is positive and significant, then the hypothesis is supported.

The results of Table 12 demonstrate that PI centrality’s effect on the number of project papers and project output efficiency follows a nonlinear pattern as team size expands. In column 1, the coefficient of the interaction term between Cen and WHum is significantly negative, while the coefficient of the interaction term between Cen and WHumSqu is significantly positive. These results support the hypothesis, indicating that when the team size is small, increasing the number of team members weakens the positive effect of PI centrality on the number of project papers. Conversely, as the team size becomes larger, the increase in team members strengthens the positive effect of PI centrality on the number of project papers.

When the team size is small, the negative effect of expanding the team may be due to increased management complexity or member laziness. In terms of management complexity, a larger team requires more communication and coordination, which may slow down information exchange and complicate decision-making. These challenges could ultimately hinder the execution efficiency and responsiveness of the project. Disagreements and conflicts between team members may also occur more frequently and become harder to manage, requiring more time and resources for resolution. On the member laziness side, individual contributions may become less visible as the team grows, weakening members’ sense of responsibility and reducing work enthusiasm and productivity. Additionally, team members may rely more on others, diminishing personal initiative and work efficiency.

In column 2, the coefficient of the interaction term between Cen and WHum is negative but not significant. In contrast, the coefficient of the interaction term between Cen and WHumSqu is significantly positive. These results do not provide strong evidence that team expansion significantly impacts the relationship between PI centrality and project paper citations. In column 3, the coefficient of the interaction term between Cen and WHum is significantly negative, while the coefficient of the interaction term between Cen and WHumSqu is significantly positive. These results suggest that as team size grows, the effect of PI centrality on project output efficiency follows a nonlinear trajectory.

The following strategies can be considered to address the issues of increased management complexity and member laziness that may arise as team size expands: (i) improving communication efficiency is crucial. Clear communication mechanisms and tools should be implemented to ensure the timely transmission and feedback of information. For instance, project management software and regular team meetings, when used effectively, can assist in tracking progress and resolving issues. Team members should be encouraged to share knowledge and information actively. Internal training sessions or workshops can also be organized to enhance communication skills and overall team efficiency. (ii) Optimizing the decision-making process is essential. Decision-making responsibilities should be streamlined by reducing unnecessary approval steps and enhancing decision-making efficiency. For example, creating a decision-making group or assigning a representative responsible for decisions can contribute to reducing hierarchical complexity. A transparent decision-making process, in which team members understand the rationale and basis for decisions, will likely to foster trust and support within the team.

(iii) Minimizing team conflicts is crucial. A clear conflict resolution process should be established, and training should be provided to enhance team members’ conflict management skills. Conflicts should be addressed promptly to prevent negative impacts on teamwork. When conducted consistently, regular team-building activities and periodic feedback sessions can strengthen collaboration, increase trust among members, and reduce potential friction. (iv) Enhancing team responsibility is essential. Each team member’s roles and responsibilities should be clearly defined to ensure that the importance of their contributions is understood. Such clarity fosters a sense of personal accountability and encourages active participation. Additionally, effective incentives, including performance evaluations and reward systems, should be implemented to motivate team members to maintain enthusiasm and commitment to their tasks.

Different language output

The impact of CPE collaboration networks on research output may vary depending on the language type of the output. The articles funded by the NSFC project are predominantly in English and Chinese. To foster academic exchanges with foreign countries, research institutions often prioritize and incentivize the publication of English articles through bonuses and promotion assessments (Xu, 2020). This phenomenon may motivate researchers to increase their publication of English articles after acquiring resources through collaboration networks. Additionally, English articles have a broader readership, potentially resulting in higher citation rates. Moreover, Chinese researchers face challenges in publishing Chinese articles due to academic inbreeding, as it can be difficult to publish articles without connections to journal editors or other influential individuals. However, the situation is different for Chinese researchers when publishing English articles. On the one hand, they have access to a wider range of English journals. On the other hand, the competition for publication is more equitable since individuals have fewer connections with foreign journals. In conclusion, the influence of collaboration networks on English research output is expected to be more pronounced. We have comprehensively analyzed why PI centrality’s effect on project output is stronger for English papers. This analysis is structured around two key dimensions: research quality and innovation and research influence.

English journals often have stricter editorial and review processes, higher language standards, and more rigorous evaluation criteria, which can result in superior quality and innovation in English papers. The publication of such high-quality or innovative English articles enables researchers to establish broader international collaboration networks, enrich their research perspectives, and gain easier access to global research resources, ultimately enhancing their research output. We analyzed the number of SCI and SSCI papers published within each project to test this inference. These two databases include prominent journals worldwide, predominantly English-language publications. Based on whether the number of SCI and SSCI papers published by a project exceeds the median for all projects in a given year, we categorized the sample into two groups: one with higher quality and innovation and the other with lower quality and innovation.

The results of Table 13 demonstrate that PI centrality has a stronger positive impact on project research output in the group with higher quality and innovation, suggesting that English publications enhance the positive effect of PI centrality on research output through higher quality and stronger innovation. Columns 1 and 2 present the effects of PI centrality on the number of project papers grouped by quality and innovation. The coefficients of Cen are significantly positive across both groups, consistent with the primary findings of this study. However, the coefficient of Cen in Column 1 is larger than in Column 2, with a p value of 0.030 for the inter-group coefficient difference test, indicating that PI centrality has a stronger positive effect on the number of project papers in projects with more high-quality and innovative English articles. Columns 3 and 4 report the grouped regression results on the effect of PI centrality on the citations of project papers. The coefficient of Cen in Column 3 is greater than in Column 4, and the p value of the inter-group coefficient difference test is 0.000. These results indicate that PI centrality has a stronger positive effect on the citations of project papers in projects containing more high-quality and innovative English articles. Finally, Columns 5 and 6 show that the positive impact of PI centrality on project output efficiency is also stronger in projects with more high-quality and innovative English publications.

As the dominant language in international academic exchanges, English offers several advantages over other languages, such as greater international visibility, stronger academic influence, enhanced resource integration, and a more pronounced reputational effect for its publications. When PI centrality is high, the collaboration network of the PI can better capitalize on these advantages, thereby amplifying the influence of English papers. These enhanced opportunities for dissemination and higher citation rates strengthen the role of centrality in driving project output. To verify this inference, we calculated the average number of English and Chinese papers per project, which were 11.381 and 8.677, respectively, indicating that NSFC projects clearly prefer publishing in English. Then, the average citations per project were examined. English papers received an average of 290.711 citations compared to 101.806 for Chinese papers, demonstrating that English publications garner more citations and thus contribute more to personal academic influence.

Finally, we utilized the output language structure of a project to measure the influence of English output. The output language structure is measured by the proportion of English output of a project, calculated as the ratio of the average citations of the project’s English papers to the average citations of its Chinese papers. If a project’s proportion of English output exceeds the annual median, it is classified as having a high proportion of English output; otherwise, it is classified as having a low proportion of English output.

The results in Table 14 show that the positive impact of PI centrality on project output is stronger when the proportion of English output in the project is higher. Columns 1 and 2 present the group test results for the impact of PI centrality on the number of project papers. The coefficient of centrality (Cen) is significantly positive in both groups, consistent with the basic regression results of this study. From an economic perspective, the coefficient for the group with a higher proportion of English output is greater than that for the group with a lower proportion. The inter-group coefficient difference test shows that the p value for the difference in Cen between columns 1 and 2 is 0.080, which is significant at the 10% level. Thus, the impact of centrality on the number of project papers is stronger in the group with a higher proportion of English output. English-language outputs have greater dissemination potential and more citation opportunities. By leveraging this advantage, PIs can further enhance their influence within the collaboration network, consolidate more resources, and increase the number of project papers.