Abstract

This study investigates the impact of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) on green innovation performance by analyzing data from China’s A-share listed firms in heavy-polluting industries between 2013 and 2022. We emphasize the moderating role of public attention in shaping the relationship between ESG and corporate green innovation. Key findings include: (1) ESG exhibits a robust positive effect on green innovation, with effect heterogeneity across firm characteristics. (2) Public attention demonstrates a significant inverted U-shaped moderating effect on the ESG–green innovation nexus, where moderate scrutiny enhances innovation but extreme scrutiny diminishes it. (3) Heterogeneity analysis reveals this moderating effect is more pronounced in non-state-owned enterprises, large firms, competitive markets, green patent-holding firms, capital-intensive industries, and growth-stage companies in highly marketized regions. These findings highlight public attention as a dual-edged monitoring mechanism, offering practical implications for fostering synergistic development between ESG adherence and green innovation among heavily polluting firms under “dual carbon goals”. This research also provides empirical insights for policymakers and businesses seeking to advance sustainable innovation in emerging economies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In pursuit of “carbon peak” targets, sustainable development has emerged as a global imperative. Despite rapid economic growth, the overexploitation of natural resources has resulted in severe ecological degradation. China’s 14th Five-Year Plan (2021–2025) prioritizes strengthening corporate environmental governance, accelerating the green transition of development models, and systematically improving environmental quality. As primary consumers of natural resources, enterprises are key actors in reconciling economic growth with ecological preservation. Addressing the tension between profitability and environmental stewardship in heavily polluting industries—and enhancing green innovation performance in this sector—represents a critical challenge for achieving sustainable development (Moriggi, 2020).

Green innovation is a pivotal catalyst for low-carbon transition and sustainable development, while ESG performance serves as a key metric for corporate sustainability (Rajesh, 2020). Rising global emphasis on sustainable practices has fostered consensus that firms must adopt expanded societal responsibilities. Consequently, corporations increasingly prioritize aligning stakeholder interests, fostering long-term resilience, cultivating ethical branding, and transparent ESG disclosure. Although ESG remains an emerging framework in China, it has garnered heightened societal engagement since the nation’s “2060 Carbon Neutrality” pledge was announced at the United Nations General Assembly. This momentum has spurred policy reforms and aligned capital flows toward ESG-aligned initiatives. Notably, robust ESG performance mitigates information asymmetry, attracts innovation-centric investments, and bolsters green innovation outcomes. Critically, institutionalizing synergies between ESG adherence and green innovation is imperative for businesses to achieve environmentally conscious growth.

Public attention, as an external mechanism, enhances corporate transparency by bridging informational gaps between firms and broader society. This heightened transparency enables stakeholders to assess and shape corporate behavior, thereby exerting normative pressures on business practices. Drawing on institutional and stakeholder theory, public environmental concerns—expressed through activism or consumption choices—likely generate targeted pressures on firms to prioritize green innovation within their ESG frameworks, given its dual role in mitigating ecological harm and delivering social value. However, the specific moderating effects of public attention on the ESG-green innovation performance linkage remain underexplored in empirical literature, signaling a critical gap in sustainable development research.

This study synthesizes existing literature to elucidate the dynamics linking ESG, public attention, and corporate green innovation behavior. We analyze the impact of ESG practices on corporate green innovation and demonstrate an inverted U-shaped moderating effect of public attention on this relationship. Heterogeneity analyses are also conducted by categorizing the sample based on firm ownership, size, competition intensity, green patent type, capital intensity, life cycle and regional marketization. Finally, the study concludes with a summary of key findings and recommendations.

This study makes three pivotal contributions to ESG and sustainability literature. First, while prior scholarship predominantly examines ESG’s financial implications (e.g., firm value and investment efficiency), our work bridges this gap by integrating ESG practices and corporate green innovation into a unified analytical framework (Giese et al. 2019). Second, we provide novel insights into how third-party rating agencies incentivize green innovation under China’s “dual-carbon” policy objectives, addressing contextual drivers often overlooked in existing studies (Feng et al. 2021). Third, departing from linear assumptions about public attention’s benefits (Gu et al. 2022), we empirically demonstrate its inverted U-shaped moderating effect on the ESG–green innovation nexus, a nonlinear dynamic critical for balancing corporate accountability and innovation efficacy. Collectively, these findings advance theoretical understanding of ESG heterogeneity’s role in fostering sustainable practices and offer actionable strategies for emerging economies pursuing low-carbon transitions.

Literature review

Existing scholarship on green innovation predominantly examines its driving factors and organizational impacts. External drivers, typically categorized into formal environmental regulations and informal stakeholder-driven institutional pressures, critically shape corporate green innovation outcomes (Zhang & Zhu, 2019; Stucki et al. 2018; Feng et al. 2021). Internal factors, analyzed through governance frameworks, highlight the role of organizational structure, board characteristics, firm size, and executive environmental consciousness in determining green innovation strategies (He & Jiang, 2019). Empirical investigations into the effects of green innovation focus on its dual implications for environmental sustainability and corporate financial performance (Ionescu, 2021; Rehman et al. 2021).

As ESG practices have expanded in scope and adoption, scholarly inquiry has pivoted from debates on theoretical foundations and measurement frameworks (Serafeim & Yoon, 2023; Azar et al. 2021) toward analyzing their multifaceted outcomes. Economically, ESG initiatives have been shown to influence corporate financial performance, enhance investment efficiency (Shanaev & Ghimire, 2022; Avramov et al. 2022), and mitigate operational and market risks (Albuquerque et al. 2019). Concurrently, ESG practices yield measurable environmental governance outcomes, with substantial empirical evidence linking robust ESG adoption to improved environmental performance (Shafique et al. 2021; Elnaboulsi et al. 2018; Montiel et al. 2021). While discrepancies persist due to variations in sample selections and contextual market factors (Albitar et al. 2020), these findings collectively refine theoretical and empirical frameworks for understanding ESG’s organizational and societal roles.

A growing body of research confirms the extensive impact of public attention on corporate behavior. Heightened public scrutiny compels firms to adopt socially responsible practices, prioritizing improved governance and accountability to avoid reputational harm and legal liabilities (Cheng & Liu, 2018). Empirical studies have thus explored public attention’s role in reshaping brand equity, accelerating industry sustainability transitions, and fostering green innovation (Gu et al. 2022; Zhang & Zhu, 2019; Liu et al. 2019). Findings suggest that stakeholder expectations, amplified by public sentiment, significantly shape corporate strategic priorities. Furthermore, public engagement in environmental governance not only amplifies regulatory pressures but also reduces information asymmetry, thereby incentivizing firms to adopt sustainable practices—though the effectiveness of such influence remains context-dependent (Zhao et al. 2022).

Extensive research confirms that robust ESG commitments demonstrably enhance corporate performance. Aligning with this consensus, scholars have increasingly investigated ESG’s relationship with corporate environmental outcomes. Chouaibi et al. (2022) and Cohen et al. (2020), for instance, analyze ESG scores’ influence on green performance within the UK and German contexts, emphasizing advanced markets with stringent regulatory frameworks. In parallel, studies leveraging data from Chinese listed firms (Lin,2024;Tan & Zhu,2022;Wu et al.,2024) empirically validate ESG’s role in accelerating green innovation. Nonetheless, Williams (2024) critiques the superficiality of ESG adoption, cautioning that enterprises may engage in symbolic green innovation (e.g., greenwashing) without substantive operational shifts, particularly in the absence of standardized metrics. Moreover, the integration of ESG into innovation strategies remains contentious, as industries with high pollution face entrenched technological and financial constraints that may hinder meaningful progress (Cort & Esty, 2020).

Research on the relationship between ESG practices and green performance in heavily polluting industries remains underexplored. Given the prominence of such industries in developing and emerging economies, analyzing the influence of ESG initiatives on green innovation within China—a pivotal case study for such contexts—bears substantial practical significance. Unlike developed nations, where “top-down” regulatory frameworks drive corporate ESG transparency, China’s emerging ESG framework currently lacks comprehensive mandatory disclosure policies. In this “bottom-up” institutional environment, existing research has yet to fully address the pivotal role of public attention in mediating the connection between ESG practices and corporate environmental performance, which is the primary focus of this study.

Theoretical basis and research hypothesis

ESG and corporate green innovation

First, according to signaling theory, high-quality ESG disclosures enable firms to signal their commitment to environmental sustainability and societal responsibility to stakeholders. Such disclosures act as credible indicators of corporate priorities, mitigating information asymmetry in markets and fostering positive stakeholder expectations. By reducing investor uncertainty, ESG transparency positions firms as sustainable development leaders. This signaling transcends mere reputation management; it incentivizes firms to embed environmental governance and green innovation into their strategic frameworks, consequently enhancing green innovation outcomes.

Building on this foundation, transaction cost economics and the resource-based view offer additional insights. ESG disclosure can be interpreted as organizational reputation investments that minimize transaction costs linked to securing external resources. Robust ESG performance diminishes perceived risks among investors and partners, easing access to innovation-critical resources. This aligns with dynamic capabilities theory, as a firm’s ESG profile strengthens internal competencies and absorptive capacity—essential traits for adapting to evolving market demands and regulatory landscapes, thereby sustaining competitive advantage.

Second, based on principal-agent theory, inherent conflicts arise between managers and shareholders within governance structures, particularly in reconciling short-term profitability with long-term investments in innovation. ESG serves as a standardized framework for external stakeholders to assess corporate conduct, thereby mitigating managerial short-termism and fostering governance stability conducive to green innovation investments. Behavioral economics further elucidates this dynamic: ESG transparency addresses cognitive biases among both executives and investors, incentivizing decisions that prioritize sustainable, long-term green innovation over immediate financial returns (Rajesh, 2020).

From the lens of information asymmetry theory, ESG ratings and disclosures reduce informational disparities between firms and external stakeholders. While heavily polluting industries face heightened scrutiny, standardized and verifiable ESG reporting clarifies firms’ genuine environmental and social performance. This transparency functions not only as an external accountability mechanism but also as an internal catalyst, motivating firms to strengthen environmental governance systems and align practices with stakeholder expectations (Broadstock et al. 2020; Pedersen et al. 2021). Consequently, ESG-driven alignment enhances corporate commitments to environmental stewardship and innovation.

Finally, integrating stakeholder theory with institutional theory reveals that ESG practices strengthen firm-stakeholder relationships across actors such as employees, suppliers, consumers, and regulators. By building organizational legitimacy and securing critical resources, these practices reduce financial constraints and foster collaborative innovation (Flammer, 2015). For instance, strategic alliances with supply chain partners mitigate capital limitations (Lins et al. 2017), while environmentally conscious consumers increasingly favor sustainable products (Li et al. 2016). These dynamics enhance firms’ market competitiveness and catalyze the advancement of disruptive green technologies.

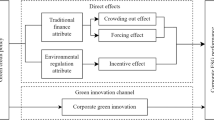

Synthesizing multiple theoretical lenses, we propose an integrated framework wherein ESG drives green innovation through three mechanisms: resource optimization, institutional alignment, and behavioral coordination. From a resource-based perspective, ESG disclosures act as strategic investments in innovation-specific assets, reducing transaction cost risks and lowering capital barriers for R&D projects. Institutionally, ESG compliance aligns firms with environmental norms, minimizing regulatory penalties and legitimizing entry into green innovation networks. Simultaneously, principal-agent theory and behavioral economics illustrate that standardized ESG metrics counter managerial short-termism by aligning executive incentives with long-term stakeholder value through cognitive adjustments. This synthesis underscores ESG’s role beyond superficial signaling—it dynamically reshapes firms’ resource allocation (enhancing dynamic capabilities), governance structures (reducing agency costs), and market strategies (capturing stakeholder preferences).

Accordingly, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1. ESG performance positively influences corporate green innovation.

The “inverted U-shape” moderating impact of public attention

As a reflection of societal environmental preferences, public attention serves as a pivotal informal institutional force influencing corporate behavior. We posit that public attention nonlinearly moderates the relationship between ESG performance and green innovation by amplifying market demand for eco-friendly products and intensifying corporate environmental accountability. Importantly, this moderating effect is not linear but follows an inverted U-shaped trajectory, where moderate levels of public scrutiny enhance green innovation performance, while excessive attention diminishes returns.

First, according to competitive advantage theory, public attention reinforces competitive market dynamics by incentivizing firms that align with societal expectations to achieve greater market differentiation. Heightened public scrutiny of environmental issues leverages collective opinion to pressure enterprises into addressing ecological externalities, thereby reducing socially harmful practices. Enhanced public environmental consciousness drives firms to pursue energy conservation, clean production, and other green innovation objectives (An et al. 2022). This improvement in green innovation performance underscores public environmental awareness as an informal institutional force, compelling strategic adjustments that align corporate goals with societal norms and catalyzing the adoption of sustainable technologies.

Besides, ESG practices often necessitate managerial paradigm shifts in response to public opinion and shifting consumer preferences (Gu et al. 2022). Organizational change theory suggests that external environmental shifts—such as rising stakeholder demands for sustainability—prompt firms to reconfigure governance models by embedding green innovation into core strategic frameworks. Through governance optimization and resource reallocation, firms advance the development and deployment of low-carbon technologies. This adaptive process not only enhances resilience to external disruptions but also serves as a critical mechanism for securing enduring competitive advantage.

Meanwhile, Corporate social responsibility (CSR) theory emphasizes that heightened public scrutiny strengthens corporate awareness of social obligations, prompting companies to adopt proactive measures in addressing environmental challenges. According to CSR principles, businesses must transcend purely economic interests by integrating societal environmental expectations into their strategic decision-making processes. By implementing green innovation practices, firms not only improve their environmental performance but also enhance public recognition and foster trust. This dynamic facilitates a mutually beneficial alignment between corporate image enhancement and environmental governance, achieving dual objectives of sustainable growth and societal accountability.

However, while public attention plays a critical role in promoting corporate accountability, excessive scrutiny may yield unintended consequences. Over-catalyzation of public engagement risks diminishing its positive effects or even triggering adverse outcomes (Wen et al. 2021). Aligned with the market pressure hypothesis, heightened public scrutiny can impose short-term performance demands on managers, incentivizing cost-cutting measures such as reduced innovation investment. Under intense pressure, executives may prioritize superficial crisis management—such as falsified disclosures or symbolic greenwashing—over substantive environmental governance. This is particularly evident in heavily polluting industries, where firms may resort to misleading advertising or performative measures to mitigate reputational risks rather than pursuing meaningful sustainability reforms. In such cases, improvements in ESG disclosure may reflect strategic impression management rather than authentic commitment to green development, as companies prioritize projecting an image of environmental responsibility over implementing resource-efficient practices.

Furthermore, while advancements in technology and management practices drive the evolution of ESG disclosure standards, an overemphasis on quantitative reporting metrics risks compromising the quality of ESG data. This undermines governance efficacy and weakens the role of ESG transparency in fostering green innovation. Excessive public pressure exacerbates this issue: rather than stimulating long-term innovation, it may push managers toward short-termism, redirecting resources from impactful R&D to cosmetic compliance measures. Consequently, when public attention surpasses an optimal threshold, ESG disclosures increasingly serve reputational objectives rather than advancing environmental stewardship, ultimately stifling innovation outcomes.

Based on these insights, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2. Public attention exerts an inverted U-shaped moderating effect on the relationship between ESG initiatives and green innovation. Specifically, moderate public attention enhances this relationship by fostering corporate transparency and accountability, whereas excessive scrutiny weakens it by incentivizing short-term managerial behavior and superficial compliance.

Research objective, methodology and data

Measurement of corporate green innovation (Green)

Green is measured as the natural logarithm of one plus the number of green patent applications filed by a firm in the current period (Chang et al. 2019).

Measurement of ESG

We adopt the Sino-Securities Index (SSI) ESG score as our measure of corporate ESG performance. The SSI ESG score is aligned with international ESG evaluation standards and tailored to fit China’s capital market and enterprises. The SSI ESG evaluation system comprises 16 themes and 44 key indicators across three major categories: environment, society, and corporate governance (Lin et al. 2021). The SSI ESG is a top-down evaluation system that establishes 16 secondary theme indicators under the three primary pillar indicators of environment, society, and corporate governance. These secondary indicators include climate change, resource utilization, environmental pollution, environmental friendliness, environmental management, human capital, product responsibility, supply chain, social contribution, data security and privacy, shareholder rights, governance structure, quality of information disclosure, governance risk, external penalties, and business ethics. Each theme indicator comprises 1–5 tertiary topic indicators, amounting to a total of 44 tertiary topic indicators. Based on this structure, over 300 underlying data indicators are analyzed and consolidated. Scores are first assigned to each tertiary topic indicator, and then combined with weights to calculate secondary theme and primary pillar indicator scores, ultimately producing the overall ESG rating for enterprises. This system has been widely recognized and applied in academic research (Lin et al. 2021).

Measurement of public attention

Public attention indicators were developed based on both domestic and international literature, using residents’ searches on the Baidu search engine for specific keywords (Guo et al. 2020). Our methodology involved conducting keyword searches in Baidu and utilizing Python tools to collect daily search volumes for words such as “pollution”,“carbon” and “PM2.5” across various regions from 2013 to 2022. The aggregated search volumes were then transformed by adding 1 and taking the natural logarithm to create proxy variables for public attention. The selection of daily search volumes for keywords such as “pollution”, “carbon” and “PM2.5” to generate a proxy variable for public attention is based on the following practical considerations and logic: First, “pollution” as the opposite of green and low-carbon development, directly reflects public concern regarding corporate environmental responsibility and green development practices. It serves as a key dimension for assessing whether companies align with green standards. Second, “carbon” is a central issue in China’s carbon emission agenda. The combustion of fossil fuels not only releases carbon dioxide but also produces nitrogen oxides and particulate matter, which are major sources of pollution and closely related to green innovation. Although carbon dioxide itself is not easily perceived by the public, pollution issues associated with it attract significant attention. Lastly, “PM2.5” as a key component of air pollution and smog, directly affects public health and quality of life. Therefore, keywords like “pollution”,“carbon” and “PM2.5” comprehensively capture public concerns about environmental issues, making them highly representative and explanatory.

Control variables

Our model controls for several factors based on the available literature: the age (Age) and size (Size) of the enterprise, its solvency (Lev), profitability (ROA), liquidity (Liq), and equity concentration (Share). The specific measurement methods for control variables are as follows: Firm Age: Measured as the natural logarithm of the current year minus the year of establishment plus one. Firm Size: Represented by the natural logarithm of total assets. Solvency: Measured as the ratio of total liabilities to total assets. Profitability: Measured as the ratio of net profit to total assets. Liquidity: Measured as the ratio of current assets to current liabilities. Equity Concentration: Measured as the sum of the squared shareholding percentages of the top five shareholders with tradable shares.

Data sources

To ensure data validity and rigor, we employed established procedures for data processing based on existing research: (1) Exclusion of observations for firms designated ST or *ST and financial companies; (2) Removal of observations with missing or abnormal data for any variable; (3) Exclusion of observations with an asset-liability ratio exceeding 1; (4) Winsorization at the top and bottom 1% for all variables. This yields a dataset of 2,668 valid panel observations across 300 companies.

Green patent data originate from the State Intellectual Property Office and the WIPO Green Patent List. ESG scores are sourced from the Sino-Securities Index (SSI) ESG database, and public attention metrics are obtained from the Baidu search index. Control variable data are sourced from the CSMAR database, and “China Urban Statistics Yearbook”. Descriptive statistics are shown in Table 1.

Models

To examine the impact of ESG on corporate green innovation performance and the moderating effect of public attention, we establish the following regression models:

Model (1) investigates how environmental, social, and governance (ESG) disclosure affects firms’ green innovation performance. Model (2) examines the linear moderating effect of public attention on the relationship between ESG disclosure and corporate green innovation performance. Finally, Model (3) investigates the “inverted U-shaped” moderating influence of public attention on the relationship between ESG and corporate green innovation performance. All models account for industry and time fixed effects, employing cluster-robust standard errors.

In the above formulae,\({{ESG}}_{{it}}\) represents the ESG index, \({{Green}}_{{it}}\) represents green innovation performance, \({{Public}}_{{it}}\) represents public attention, and \({{Control}}_{{it}}\) denotes control variables. \({{ESG}}_{{it}}\times {{Public}}_{{it}}\) is the interaction term between ESG and public attention. \({\varphi }_{i}\) and \({\varphi }_{t}\) are industry and time fixed effects variables, respectively. \({\varepsilon }_{{it}}\) is the random error term.

Before regression, we conduct a preliminary assessment using Pearson’s correlation coefficient test and the variance inflation factor (VIF) test to mitigate issues of multicollinearity and potential pseudo-regression. Correlation coefficient analysis indicates that none of the correlations between the nine explanatory variables exceed 0.6. The highest correlation, between ROA and Lev is 0.513. VIF analysis reveals that the highest VIF value among all variables is 3.55, well below the threshold of 5, indicating no significant multicollinearity issues. The results are shown in Tables 2 and 3.

Results and discussion

Baseline regression result

Columns (1) and (2) of Table 4 report the effect of ESG on green behavior. In Column (1), the coefficient on ESG is 0.105, significant at the 1% level, indicating that ESG enhances enterprises’ green patent output. In Column (2), after incorporating a series of control variables the coefficient on ESG remains significant at the 1% level, although it is reduced to 0.0695. H1 is therefore verified.

The coefficients on control variables reveal the following. (1) There is a substantial positive association (coefficient = 0.172) between Size and Green, showing that larger firms exhibit higher levels of green innovation and a stronger inclination toward green initiatives. (2) Additionally, both Lev and ROA show positive and significant coefficients in the regression models for green innovation behavior, suggesting that enterprises with higher debt ratios, and greater operating income tend to engage more in green innovation. (3) Conversely, Age and Share display negative and significant coefficients, indicating that older firms and those with higher equity concentration tend to exhibit less innovative behavior.

Columns (3) and (4) of Table 4 report the role of public attention in the relationship between ESG and green innovation. The first-order interaction term, ESGPublic, is used to investigate whether public attention has a linear moderating impact. The regression results reveal that the coefficients on ESG remain positive and significant at the 1% level, but the coefficients on the interaction variable ESGPublic are not significant. This suggests that public attention has no linear moderating effect on the connection between ESG and company environmental innovation. The absence of a linear moderating effect of public attention on the relationship between ESG and corporate environmental innovation may stem from the complexity of its underlying mechanisms, which cannot be fully captured by a simple linear relationship. Moderate public attention can exert appropriate pressure, encouraging green innovation, but excessive attention may lead to short-term behaviors, such as superficial disclosures or perfunctory investments, thereby weakening the long-term motivation for green innovation. Consequently, the moderating effect of public attention is likely to exhibit a nonlinear pattern, such as an inverted U-shaped relationship, rather than a straightforward linear enhancement or reduction.

Columns (5) and (6) of Table 4 investigate the “inverted U-shaped” moderating effect of public attention on the relationship between ESG and company green innovation. Model (3) includes a second-order interaction term, ESGPublic2, to test this effect. The results reveal that the coefficients on the first-order interaction of ESG and public attention are considerably positive and significant at the 5% and 1% levels in Columns (5) and (6), respectively. Importantly, the coefficient on ESGPublic2 is negative and significant at the 1% level in both specifications, indicating that public attention has a large “inverted U-shaped” moderating influence on the relationship between ESG and corporate green innovation. H2 is therefore validated. Based on the previous theoretical analysis, the “inverted U-shaped” moderating effect of public attention on the relationship between ESG and corporate green innovation may stem from its dual impact on firms. Moderate public attention can exert reasonable pressure through market competition rules and public opinion, encouraging firms to increase investment in green innovation to meet environmental expectations and social norms. However, excessive public attention may impose excessive short-term performance pressure on firms, leading them to adopt superficial disclosures or engage in greenwashing, which undermines the positive effects of green innovation. Moreover, an overemphasis on the quantity of ESG disclosures may reduce the quality of information, weakening the effectiveness of ESG governance. Firms must balance short-term pressures and long-term objectives in their operations, as either excessive or insufficient public attention can disrupt this balance, resulting in the “inverted U-shaped” moderating effect.

Robustness tests

Replacement of variables

We conduct robustness tests using alternative variables (Minutolo et al. 2019). First, Columns (1)–(3) of Table 5 present regression results where the independent variable is replaced with firms’ Bloomberg ESG ratings. Second, further robustness tests are conducted by substituting the number of green patent applications with the number of green patents granted, as reported in Columns (4) to (6) of Table 5. Importantly, the results of these robustness tests align consistently with our benchmark results.

Instrumental variable method

We employ a robustness test using two-stage least-squares (2SLS) regression with four different instrumental variables (Xie and Lv, 2022; Dyck et al.,2019; Attig et al.,2016). (1) One lag period for ESG; (2) Area affected by natural disasters; (3) Regional level of charitable giving; (4) ESG fund shareholding. The instrumental variables pass the under-identification test (Anderson canonical correlation LM test), the weak identification test (Cragg-Donald Wald F statistic), and the weak instrumental variable test (Anderson-Rubin Wald test F statistic). The regression results, presented in Table 6 and Table 7, demonstrate that our main findings are robust.

Excluding the effect of macro factors

We add interaction fixed effects of industry*year and province fixed effects to the baseline model, to consider the impact of various macroeconomic factors on the regression. The results, presented in Table 8, are consistent with our main findings.

Restricting the firm fixed effects

To enhance the credibility of the research conclusions, this section replaces industry fixed effects with firm fixed effects in the model specification. The regression results reported in Table 9 demonstrate that the impact of ESG on corporate green innovation, as well as the “inverted U-shaped” moderating effect of public attention, remain statistically significant. This indicates that, although firm fixed effects may lead to the loss of some important firm-level information, the regression results remain consistent with the baseline findings.

Further heterogeneity analyses

Enterprise ownership heterogeneity

To investigate variations in the relationship identified in our core findings, we conduct heterogeneity analyses based on enterprise ownership. The sample is categorized into state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and private enterprises (non-SOEs) based on the classification of controlling shareholders. As shown in Columns (1) and (4) of Table 10, the coefficients on ESG are positive and statistically significantly for both SOEs and non-SOEs. However, the regression coefficient for SOEs is notably larger, suggesting that ESG exerts a stronger influence on green innovation in SOEs. Furthermore, the moderating effect of public attention differs between the two groups: non-SOEs exhibit an inverted U-shaped relationship, whereas SOEs demonstrate a linear moderating effect.

This divergence likely stems from fundamental differences in organizational culture, governance structures, and market environments. Non-SOEs, characterized by market-driven agility and innovation-oriented strategies, are more responsive to shifts in public attention. Initial increases in public scrutiny incentivize non-SOEs to align with societal expectations through green innovation. However, excessive attention may induce short-termism, diverting resources from substantive innovation to symbolic compliance, thereby creating a inverted U-shaped relationship. In contrast, SOEs prioritize stability and long-term strategic alignment with government policies. Bolstered by institutional support and resource advantages, they integrate public attention into existing governance frameworks rather than reacting impulsively to external pressures. Consequently, public attention exerts a steady, linear enhancement on SOEs’ green innovation efforts, as their systemic planning buffers against destabilizing short-term fluctuations.

Enterprise size heterogeneity

Green innovation entails high risks and extended payback periods, posing greater challenges for smaller firms with limited financial and organizational capacity. To examine these disparities, we categorize the sample into large- and small-scale enterprises. As shown in Columns (1) and (4) of Table 11, while ESG practices positively influence green innovation across both groups, the effect is markedly stronger for large enterprises, evidenced by higher coefficient magnitudes and statistical significance. Furthermore, the moderating role of public attention exhibits an inverted U-shaped relationship for large firms, whereas this curvilinear pattern is less pronounced among smaller enterprises.

Differences in resource endowments and institutional capacity are likely to explain this divergence. Large enterprises benefit from robust financial reserves, mature governance frameworks, and economies of scale, enabling them to channel ESG-driven resources into long-term green innovation despite inherent risks. Their systemic capacity to manage extended payback cycles and absorb uncertainties amplifies ESG’s impact. Conversely, small enterprises face structural constraints—limited capital, weaker risk tolerance, and fragmented organizational focus—that restrict their ability to leverage ESG initiatives effectively, even when adopting such practices.

The curvilinear moderating effect of public attention in large enterprises may reflect their heightened visibility and exposure to stakeholder scrutiny. While moderate public engagement incentivizes substantive green innovation to align with societal expectations, excessive scrutiny risks diverting resources toward performative compliance (e.g., symbolic ESG reporting) rather than meaningful technological advancement. Smaller firms, however, operate under reduced public visibility and tighter resource limitations, dampening both the intensity and transformative potential of external pressures. Consequently, public attention exerts a weaker and less dynamic moderating influence on their innovation trajectories.

Market competition intensity heterogeneity

To examine variations in the relationship between ESG and green innovation across competitive environments, we conduct heterogeneity tests using the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) to measure market concentration. As shown in Table 12, ESG practices significantly enhance green innovation in both high-HHI (less competitive) and low-HHI (more competitive) markets. However, the effect is stronger for low-HHI enterprises, with larger coefficient magnitudes. Furthermore, public attention exhibits a positive moderating effect exclusively in low-HHI markets, while demonstrating a negative direct effect on high-HHI firms.

This difference can be attributed to distinct market dynamics. First, monopolistic firms (high-HHI markets) often wield significant market power, enabling price-setting advantages and rent-seeking behaviors that reduce incentives for green innovation. Their entrenched market positions foster complacency, rendering them less responsive to public scrutiny. External scrutiny may even be perceived as a reputational liability, prompting symbolic compliance measures (e.g., superficial ESG disclosures) rather than substantive innovation. Second, firms in competitive markets (low-HHI) face constant pressure to differentiate themselves. Here, ESG-driven green innovation serves dual purposes: mitigating regulatory and pollution-related costs while enhancing stakeholder trust and market share. Competitive environments also amplify firms’ sensitivity to public expectations, incentivizing proactive alignment with societal demands to sustain long-term viability.

Green innovation heterogeneity

To assess variations in green innovation outcomes, we classify green patents into two categories: green invention patents (GIPs) and green utility model patents (GUMPs). As shown in Table 13, ESG practices exert a stronger positive influence on GIPs than on GUMPs. Furthermore, public attention demonstrates a curvilinear (inverted U-shaped) moderating effect exclusively for GIPs, with no significant impact observed on GUMPs.

This divergence stems from the distinct characteristics of the two patent types. GIPs, characterized by technological novelty and disruptive market potential, attract heightened stakeholder attention due to their capacity to redefine industry standards. Moderate public scrutiny incentivizes firms to prioritize GIPs as a strategic response to ESG demands, driving innovation. However, excessive scrutiny may divert resources toward compliance-oriented activities, attenuating returns and producing the observed curvilinear relationship. In contrast, GUMPs typically represent incremental refinements to existing processes, which garner limited market recognition and lack transformative appeal. Consequently, public attention exerts minimal influence on GUMP development, as firms perceive fewer strategic or reputational benefits in allocating scarce resources to such innovations.

Capital intensity heterogeneity

The impact of ESG initiatives and public attention on green innovation may vary across firms with differing levels of capital intensity. To capture this heterogeneity, we measure firm-level capital intensity using the ratio of total assets to operating revenue, reflecting the degree to which firms rely on machinery and equipment in production processes. Firms are categorized into capital-intensive and labor-intensive groups based on median capital intensity for heterogeneity analysis.

As shown in Table 14, the relationships between ESG performance, public attention, and green innovation differ significantly across capital intensity levels. For high capital intensity firms, the regression coefficient for ESG is positive, with public attention exhibiting an inverted U-shaped moderating effect. In contrast, low capital intensity firms demonstrate a statistically insignificant ESG coefficient and a linear moderating effect of public attention. These findings suggest that capital-intensive firms, benefiting from stronger resource endowments and transformation capabilities, more effectively translate ESG practices into green innovation outcomes and are more responsive to bidirectional influences from public concern. Conversely, labor-intensive firms exhibit simpler, linear moderating effects due to their constrained transformation capacities. This empirical evidence highlights significant disparities in intrinsic conditions and response mechanisms between firm types when addressing ESG considerations and external public pressures.

Life cycle heterogeneity

Firms exhibit distinct strategic priorities, innovation incentives, and risk profiles at different stages of their life cycles. This study posits that the influence of ESG initiatives and public attention on green innovation may vary across these stages. To test this proposition, we classify firms into growth, maturity, and decline phases using four criteria: sales revenue growth rate, retained earnings ratio, capital expenditure ratio, and firm age (Dickinson,2011;Anthony and Ramesh,1992; Zhao and Li,2024).

As presented in Table 15, ESG practices consistently enhance green innovation across all life cycle stages. However, the moderating effect of public attention follows an inverted U-shaped pattern exclusively during the growth stage. Growth-phase firms, characterized by organizational flexibility, agile resource allocation, and heightened sensitivity to external pressures, benefit from moderate public attention, which incentivizes ESG adoption and strengthens external oversight. Excessive public scrutiny, however, may trigger overly conservative strategies to mitigate reputational risks or short-term performance demands, stifling long-term green innovation investments and creating the observed inverted U-shaped effect. In contrast, mature firms exhibit rigid decision-making processes due to stabilized structures and business models, while declining firms face resource constraints and restructuring challenges. These factors diminish the dual role of public attention as both an incentive and a risk signal, explaining the absence of a similar curvilinear moderating effect in these phases.

Marketization heterogeneity

The degree of marketization varies significantly across regions where firms operate, with areas of higher marketization exhibiting more advanced economic reforms and superior institutional quality compared to less marketized regions. To assess this heterogeneity, we categorize regions into high- and low-marketization groups using the median value of the regional marketization index. As illustrated in Table 16, the regression coefficients for ESG performance are statistically more significant in high-marketization regions. Furthermore, the inverted U-shaped moderating effect of public attention on ESG outcomes is observed exclusively in these regions.

In highly marketized regions, robust institutional frameworks—characterized by efficient market mechanisms, high transparency, and competitive environments—enhance external monitoring and incentive structures. These conditions enable ESG investments to yield clearer market feedback, amplifying their effectiveness. Public attention further operates within a dual role, serving as both an incentive and a constraint within a moderate range, thereby generating the observed inverted U-shaped effect. Conversely, in low-marketization regions, underdeveloped institutions and fragmented market signals hinder firms’ ability to derive tangible benefits from ESG practices. Institutional deficiencies also weaken the impact of public scrutiny, as inadequate regulatory and market infrastructures restrict the realization of both ESG-driven incentives and public oversight mechanisms.

Conclusion and recommendation

This study examines the impact of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) practices on green innovation within China’s A-share listed firms in heavy-polluting industries, with a focus on the moderating role of public attention. Our analysis reveals three key findings. First, ESG performance exerts a robust positive influence on corporate green innovation. Second, public attention exhibits an inverted U-shaped moderating effect on the ESG–green innovation relationship: moderate levels of public scrutiny strengthen this link, whereas excessive attention triggers short-termism or superficial compliance, ultimately undermining innovation. Third, heterogeneity tests demonstrate that this moderating effect varies significantly across firm ownership structures, sizes, competition intensity, green patent types, capital intensity, life-cycle stages, and regional marketization levels.

Based on these findings, we propose three policy-driven recommendations to advance sustainable development for enterprises, policymakers, and stakeholders.

First, firms in heavy-pollution sectors should integrate structured ESG frameworks into their governance systems to align with sustainability goals. This requires three strategic initiatives: (1) Institutionalize ESG governance. Establish dedicated ESG management offices to oversee disclosures and align ESG metrics with corporate strategy. These offices should design annual sustainability roadmaps featuring measurable targets and monitor progress through quarterly assessments. (2) Enhance stakeholder transparency. Adopt adaptive public engagement strategies, such as monthly sustainability briefings and real-time social media dashboards, to communicate achievements and challenges. (3) Catalyze innovation partnerships. Foster long-term R&D collaborations with academic institutions and cleantech startups to address cost barriers and accelerate sustainable innovation.

Second, policymakers must codify sector-specific ESG standards to harmonize environmental accountability with economic incentives. This entails three critical actions: (1) Legislate sectoral ESG benchmarks. Enforce industry-specific metrics for high-pollution sectors, explicitly tied to green financing eligibility. Such mandates standardize accountability while incentivizing compliance through financial mechanisms. (2) Implement adaptive regulatory tools. Integrate a “Public Attention Index” (PAI) into national ESG platforms to track real-time public sentiment. Thresholds within the PAI should activate tiered interventions—for instance, subsidies for firms under moderate scrutiny and mandatory audits for those exceeding critical thresholds—ensuring proportional regulatory responses. (3) Foster global ESG collaboration. Establish a transnational innovation fund co-financed by China’s Development Bank and multilateral institutions, prioritizing emerging economies. By sharing green technologies and governance models, this initiative enhances transparency and comparability while aligning top-down regulatory frameworks with bottom-up ESG advancements.

Third, firms should tailor strategies to their organizational characteristics to balance public attention and green innovation. Key steps include: (1) Ownership-specific Interventions. State-owned enterprises (SOEs) should leverage their institutional stability by forming cross-sector technology alliances during peak public attention, thereby sharing R&D resources to lower innovation costs. In contrast, non-SOEs should benefit from risk-mitigation instruments to ease liquidity constraints when under heightened public scrutiny. (2) Industry-Lifecycle Adjustments. Capital-intensive firms could adopt carbon-adjusted credit mechanisms, where emission-reduction achievements secure preferential loan terms during moderate public attention phases. Growth-stage enterprises might implement dynamic “public attention–innovation matching funds” with subsidies that increase in proportion to public attention to balance stakeholder pressure with sustainable R&D investment. (3) Regional Marketization Policies. Piloting decentralized “ESG Innovation Zones” could foster local green regulatory frameworks and reinvest carbon market revenues into innovation in developed regions. Meanwhile, less-developed regions should receive redistributive fiscal transfers and institutional training to bolster governance capacity.

This study emphasizes China’s representativeness as a critical case for understanding ESG dynamics in developing and emerging economies. Its distinctive “bottom-up” ESG development trajectory, combined with a supportive policy framework, provides a robust basis for exploring the nonlinear moderating role of public attention. While the analysis centers on China, its insights are relevant to nations with comparable institutional and market conditions. For instance, India’s rapidly expanding heavy industry sector and Brazil’s regulatory gaps in Amazonian industries face analogous challenges in reconciling ESG standards with innovation-driven growth. Two pivotal lessons emerge: (1) Institutionally fragmented economies (e.g., Indonesia, Nigeria) could adopt China’s hybrid “top-down/bottom-up” ESG governance, integrating state-mandated benchmarks with civil society oversight to enhance compliance. (2) Resource-dependent economies (e.g., South Africa, Chile) may align ESG metrics with localized priorities such as water stewardship or circular supply chains, mirroring China’s sector-specific policy adaptations.

Given the marked institutional heterogeneity between emerging and developed economies, our future research will address two critical dimensions. First, broadening the geographic scope of analysis to incorporate cross-national and cross-regional datasets, enabling more comprehensive insights into how ESG practices drive green innovation and how public attention moderates these effects. Second, examining systemic variations across countries—particularly differences in resource endowments, policy frameworks, and market architectures—to identify context-specific pathways for aligning ESG strategies with sustainability objectives. These comparative investigations are essential for formulating tailored ESG strategies that effectively promote green innovation on a global scale.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author (Wenyuan Ma) upon reasonable request.

References

Albitar K, Hussainey K, Kolade N, Gerged AM (2020) ESG disclosure and firm performance before and after IR: the moderating role of governance mechanisms. Int J Acc Inf Manag 28(3):429–444. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJAIM-09-2019-0108

Albuquerque R, Koskinen Y, Zhang C (2019) Corporate social responsibility and firm risk: theory and empirical evidence. Manag Sci 65(10):4451–4469. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2018.3043

An Y, Jin H, Liu Q, Zheng K (2022) Media coverage and agency costs: evidence from listed companies in China. J Int Money Financ 124:102609. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jimonfin.2022.102609

Anthony JH, Ramesh K (1992) Association between Accounting Performance Measures and Stock Prices. J Acc Econ 15(2-3):203–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-4101(92)90018-w

Attig N, Boubakri N, El Ghoul S, Guedhami O (2016) Firm internationalization and corporate social responsibility. J Bus Ethics 134:171–197. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2410-6

Avramov D, Cheng S, Lioui A, Tarelli A (2022) Sustainable investing with ESG rating uncertainty. J Financ Econ1 45(2):642–664. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2021.09.009

Azar J, Duro M, Kadach I, Ormazabal G (2021) The big three and corporate carbon emissions around the world. J Financ Econ 142(2):674–696. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2021.05.007

Broadstock DC, Matousek R, Meyer M, Tzeremes NG (2020) Does corporate social responsibility impact firms’ innovation capacity? The indirect link between environmental and social governance implementation and innovation performance. J Bus Res 119:99–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.07.014

Chang X, Chen Y, Wang SQ, Zhang K, Zhang W (2019) Credit default swaps and corporate innovation. J Financ Econ 134(2):474–500. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2017.12.012

Cheng J, Liu Y (2018) The effects of public attention on the environmental performance of high-polluting firms: based on big data from web search in China. J Clean Prod 186:335–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.03.146

Chouaibi S, Chouaibi J, Rossi M (2022) ESG and corporate financial performance: the mediating role of green innovation: UK common law versus Germany civil law. EuroMed J Bus 17(1):46–71. https://doi.org/10.1108/EMJB-09-2020-0101

Cohen L, Gurun UG, Nguyen QH (2020) The ESG-innovation disconnect: evidence from green patenting. Natl Bur Econ Res. https://doi.org/10.3386/w27990

Cort T, Esty D (2020) ESG standards: looming challenges and pathways forward. Organ Environ 33:119047878. https://doi.org/10.1177/1086026620945342

Dickinson V (2011) Cash Flow Patterns as a Proxy for Firm Life Cycle. Account Rev 86(6):1969–1994. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-10130

Dyck A, Lins KV, Roth L, Wagner HF (2019) Do Institutional Investors Drive Corporate Social Responsibility? International Evidence. J Financ Econ 131(3):693–714. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2018.08.013

Elnaboulsi JC, Daher W, Sağlam Y (2018) On the social value of publicly disclosed information and environmental regulation. Resour Energy Econ 54:1–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reseneeco.2018.05.003

Feng Y, Wang X, Liang Z, Hu S, Xie Y, Wu G (2021) Effects of emission trading system on green total factor productivity in China: empirical evidence from a quasi-natural experiment. J Clean Prod 294(4):126262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.126262

Flammer C (2015) Does product market competition foster corporate social responsibility? Evidence from trade liberalization. Strateg Manag J 36(10):1469–1485. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2307

Giese G, Lee LE, Melas D, Nagy Z, Nishikawa L (2019) Foundations of ESG investing: how ESG affects equity valuation, risk, and performance. J Portf Manag 45(5):69–83. https://doi.org/10.3905/jpm.2019.45.5.069

Gu Y, Ho KC, Xia S, Yan C (2022) Do public environmental concerns promote new energy enterprises’ development? Evidence from a quasi-natural experiment. Energy Econ 109:105967. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2022.105967

Guo M, Kuai Y, Liu X (2020) Stock market response to environmental policies: evidence from heavily polluting firms in China. Econ Model 86:306–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2019.09.028

He XP, Jiang S (2019) Does gender diversity matter for green innovation? Bus Strateg Environ 28(7):1341–1356. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2319

Ionescu L (2021) Corporate environmental performance, climate change mitigation, and green innovation behavior in sustainable finance. Econ Manag Financ Mark 16(3):94–106. https://doi.org/10.22381/emfm16320216

Li S, Jayaraman V, Paulraj A, Shang K (2016) Proactive environmental. strategies and performance: role of green supply chain processes and green product design in the Chinese high-tech industry. Int J Prod Res 54(7):2136–2151. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2015.1111532

Lin Y, Fu X, Fu X (2021) Varieties in state capitalism and corporate. innovation: evidence from an emerging economy. J Corp Financ 67:101919. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2021.101919

Lins K V, Servaes H, Tamayo A (2017) Social capital, trust, and firm performance: The value of corporate social responsibility during the financial crisis. J Financ 72(4):1785–1824. https://doi.org/10.1111/jofi.12505

Liu X, Ji X, Zhang D, Yang J, Wang Y (2019) How public environmental concern affects the sustainable development of Chinese cities: an empirical study using extended DEA models. J Environ Manag 251:109619. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.109619

Lin Z (2024) Does ESG performance indicate corporate economic sustainability? Evidence based on the sustainable growth rate. Borsa Istanb Rev 24(3):485–493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bir.2024.02.010

Minutolo MC, Kristjanpoller WD, Stakeley J (2019) Exploring environmental, social, and governance disclosure effects on the S&P 500 financial performance. Bus Strateg Environ 28(6):1083–1095. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2303

Moriggi A (2020) Exploring enabling resources for place-based social entrepreneurship: a participatory study of Green Care practices in Finland. Sustain Sci 15:437–453. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-019-00738-0

Montiel I, Cuervo-Cazurra A, Park J, Antolín-López R, Husted BW (2021) Implementing the United Nations’ sustainable development goals in international business. J Int Bus Stud 52(5):999–1030. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-021-00445-y

Pedersen LH, Fitzgibbons S, Pomorski L (2021) Responsible investing: the ESG-efficient frontier. J Financ Econ 142(2):572–597. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2020.11.001

Rajesh R (2020) Exploring the sustainability performances of firms using environmental, social, and governance scores. J Clean Prod 247:119600. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.119600

Rehman SU, Kraus S, Shah SA, Khanin D, Mahto RV (2021) Analyzing the relationship between green innovation and environmental performance in large manufacturing firms. Technol Forecast Soc Change 163(2):120481. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120481

Serafeim G, Yoon A (2023) Stock price reactions to ESG news: the role of ESG ratings and disagreement. Rev Acc Stud 28(3):1500–1530. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-022-09675-3

Shafique I, Kalyar MN, Mehwish N (2021) Organizational ambidexterity, green entrepreneurial orientation, and environmental performance in smes context: examining the moderating role of perceived CSR. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag 28(03):446–456. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.2060

Shanaev S, Ghimire B (2022) When ESG meets AAA: the effect of ESG rating changes on stock returns. Financ Res Lett 46:102302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2021.102302

Stucki T, Woerter M, Arvanitis S, Peneder M, Rammer C (2018) How different policy instruments affect green product innovation: a differentiated perspective. Energy Policy 114(3):245–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2017.11.049

Tan Y, Zhu Z (2022) The effect of esg rating events on corporate green innovation in china: the mediating role of financial constraints and managers’ environmental awareness. Technol Soc 68:101906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2022.101906

Wen W, Ke Y, Liu X (2021) Customer concentration and corporate social responsibility performance: evidence from China. Emerg Mark Rev 46:100755. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ememar.2020.100755

Williams J (2024) Greenwashing: appearance, illusion and the future of “green” capitalism. Geogr Compass 18. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12736

Wu L, Yi X, Hu K, Lyulyov O, Pimonenko T (2024) The effect of esg performance on corporate green innovation. Bus Process Manag J (ahead-of-print). https://doi.org/10.1108/BPMJ-04-2023-0237

Xie HJ, Lv X (2022) Responsible Multinational Investment: ESG and Chinese OFDI. Economic Res J 57(03):83–99

Zhang F, Zhu L (2019) Enhancing corporate sustainable development: stakeholder pressures, organizational learning, and green innovation. Bus Strateg Environ 28(6):1012–1026. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2298

Zhao L, Zhang L, Sun J, He P (2022) Can public participation constraints promote green technological innovation of Chinese enterprises? The moderating role of government environmental regulatory enforcement. Technol Forecast Soc Change 174:121198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121198

Zhao QN, Li H (2024) Does ESG Rating Promote Corporate Green Technology Innovation: Micro Evidence From Chinese Listed Companies. South China J Econ 2:116–135. https://doi.org/10.19592/j.cnki.scje.410177

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study design, Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Software, Writing - Original Draft and Revision: Caixia Song; Writing - Review & Editing, Language and Supervision: Wenyuan Ma.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required as the study did not involve human participants.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies involving human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Song, C., Ma, W. ESG and green innovation: nonlinear moderation of public attention. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 667 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05002-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05002-8

This article is cited by

-

The impact of R&D expenditure, capital investment, and green subsidies on green innovation efficiency: evidence from Pakistani manufacturing enterprises

Environment, Development and Sustainability (2026)