Abstract

As the COVID-19 pandemic recedes and travel resumes, it is important to understand how the influences on inter-city road travel varied across different stages of the pandemic. However, the underlying spatiotemporal heterogeneity in the relationship between the mobility shifts and its determinants at different pandemic stages is unclear. This research divides the pandemic timeline into four distinct stages based on the data from the Chinese Health Care Commission and Amap platform. By using a multiscale geographically and temporally weighted regression model (MGTWR), this paper analyzes how the pandemic factor, road infrastructure, population mobility motivations, and other external factors impact inter-city road travel at different pandemic stages. Our findings reveal a “falling-rising-stabilizing-falling” pattern in the overall volume of inter-city mobility over time. Despite the pandemic depressed the road travel volumes, it did not significantly alter the overall spatial patterns of inter-city mobility. However, Spatiotemporal heterogeneity is found in many influencing relationships. The impacts of COVID-19 cases and road infrastructure vary across stages and cities, while other factors are relatively temporally stable. These insights inform economic recovery and policy transitions in the post-pandemic era.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has been recognized by the United Nations as the most significant challenge to humanity since World War II (OECD, 2020; The Lancet, 2020; WHO, 2020). This global crisis has profoundly impacted both human health and economic development. Due to the virus’s high transmissibility and variability, travel restrictions have been effective in mitigating its spread (Wei et al., 2021). However, these restrictions also reduce travel volumes between cities, thereby affecting inter-city economic exchanges and social connections (Li et al., 2021; Chang et al., 2021a; Charoenwong et al., 2020; Dueñas et al., 2021). As the first country to experience a large-scale outbreak, China—with its unique urban-rural dichotomy and significant annual floating population—implemented stringent control measures, providing a compelling case study for examining the relationship between pandemic management and road travel.

Previous research has shown the necessity of exploring mobility dynamics during various stages of the pandemic, offering crucial insights for post-pandemic economic recovery policies (Sills et al., 2020; Hou et al., 2021; Lai et al., 2020; You, 2022). Big data has provided compelling support for capturing human mobility (Oliver et al., 2020; Snoeijer et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2022). The pandemic’s impact on travel is evident both within and between cities (Borkowski et al., 2021; Beria and Lunkar, 2021; Manzira et al., 2022; Shakibaei et al., 2021). Studies indicate that inter-city virus transmission occurs rapidly in the early stages of an outbreak, while intra-city transmission becomes predominant following the adoption of control policies (Gu et al., 2022; Mu et al., 2020). These differing transmission dynamics require distinct management strategies; reducing intra-city travel primarily mitigates pandemic risk, whereas limiting inter-city travel curbs the spread of the virus and aids in the precise identification of high-risk areas (Chang et al., 2021b). China’s travel restrictions, particularly those targeting inter-city movement, have proven effective in controlling the pandemic (Mu et al., 2020; Kraemer et al., 2020; Yu et al., 2021).

Despite extensive research on the impact of COVID-19 on inter-city travel in China, there remains a gap in understanding how the dynamics of road travel vary across different stages of the pandemic. Factors such as city size, population density, medical infrastructure, and urban governance significantly influence a city’s ability to manage virus transmission (Chen et al., 2021; Chu et al., 2021). Consequently, the pandemic’s effects exhibit considerable spatial and temporal heterogeneity. While previous studies have shown the pandemic’s inhibitory impact on travel (Li et al., 2022), they often fail to capture the spatial and temporal variability of these effects within a homogeneous global framework. Thus, investigating mobility dynamics during the pandemic requires an approach that accounts for this heterogeneity, utilizing comprehensive spatial and temporal data. An additional issue is the lack of focus on road travel in the current relevant study. In China, road transportation serves as the primary mode of inter-city travel. Highways and expressways constitute the predominant infrastructure facilitating long-distance journeys between cities and metropolitan areas (Wang et al., 2020). The changes in road travel deserve special attention, especially during pandemics, when rail and air travel are often affected by irregular temporary control policies (Zhu and Guo, 2021).

In the context of the research gap, we employ data encompassing the entire pandemic period to examine how road travel between Chinese cities has been affected by COVID-19 and other variables. The research questions of this study encompass two main points. First, what are the impacts of COVID-19 case numbers and road infrastructure on inter-city road travel in China? Second, how do these impacts exhibit spatiotemporal variations across different stages of the pandemic? To address these research questions, we initially delineate the phases of the pandemic based on confirmed case data from the Chinese Health and Welfare Commission. Subsequently, Amap platform data is utilized to analyze patterns of inter-city road travel within China. Following this, a multiscale geographically and temporally weighted regression model (MGTWR) is applied to investigate the nuanced spatiotemporal dynamics of these impacts further. The spatial non-stationarity of influencing factors is an important characteristic of geographic elements (Stewart Fotheringham et al., 1996; Fotheringham et al., 2017; Gu et al., 2021; Yu et al., 2020). This model allows us to assess the spatial and temporal heterogeneity of road travel across Chinese cities. We analyze the evolving spatial structure and characteristics of inter-city travel during different pandemic stages, making the statistical inference using the MGTWR model. Our study constructs a comprehensive framework that includes pandemic shock factors, travel motivations, transportation conditions, and city characteristics, providing valuable insights for economic recovery in the post-pandemic era and a deeper understanding of road travel dynamics in China.

Literature review and research framework

Research on COVID-19 and inter-city mobility

The COVID-19 pandemic has profoundly transformed inter-city mobility patterns. Mobility was heavily affected by the pandemic due to the implementation of public health measures, behavioral changes, and economic disruptions. The pandemic’s impact on mobility manifests across multiple dimensions, including the quantity of movement, its structural composition, and its elasticity in response to external shocks (Dueñas et al., 2021; Lee and Eom, 2024; Gibbs et al., 2020). One of the most immediate consequences of the pandemic was a substantial and widespread decrease in human mobility (Echaniz et al., 2021; Ferreira et al., 2022; Iacus et al., 2020). Nationwide lockdowns, curfews, and travel restrictions led to an abrupt decline in inter-city travel during the early phases of the pandemic (Sung et al., 2023; Sasidharan et al., 2020; Ko et al., 2024). Mobility changes also varied across demographic groups, travel modes, and regions (Wei et al., 2021; Hou et al., 2021; Ferreira et al., 2022; Zhu and Tan, 2022). COVID-19 also reshaped the structure of mobility. Travel patterns shifted as individuals adapted to new realities, including remote work, online education, and localized living. Such adaptations led to reduced long-distance travel and increased reliance on local mobility within neighborhoods or nearby regions (Fatmi, 2020). These behavioral shifts underscore the pandemic’s capacity to alter mobility not just quantitatively but also qualitatively over time (Borkowski et al., 2021).

However, such mobility declines were short-lived in many contexts. As the pandemic’s initial shock subsided, inter-city mobility demonstrated remarkable resilience, with gradual recovery patterns emerging in alignment with the relaxation of restrictions and improved public health conditions (Liu et al., 2023; Li et al., 2023; Thombre and Agarwal, 2021). This recovery was uneven across regions, travel modes, and population groups, reflecting varied levels of vulnerability and adaptability (Wang et al., 2022). In addition, the global spread of the COVID-19 pandemic has rendered urban population mobility more susceptible to seasonal climate changes (Shaman and Kohn, 2009), urban population size and density, building density (Dalziel et al., 2018), urban economic level, medical conditions (Gardner et al., 2018), and the confluence of various other factors.

Road travel has historically been one of the most prominent forms of inter-city mobility. Road travel offers flexibility, cost-effectiveness, and connectivity (Yang et al., 2022). In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, road travel played a particularly significant role as other modes of transportation, such as air and rail, faced stricter regulations and operational constraints. For instance, air travel experienced drastic reductions due to international border closures, while rail services were suspended or operated at reduced capacity in many countries (Hotle and Mumbower, 2021). Despite its relative resilience compared to other modes, road travel was not immune to the pandemic’s disruptions. The initial phases of COVID-19 witnessed a sharp decline in road travel as governments imposed lockdowns and stay-at-home orders to curb virus transmission (Borkowski et al., 2021). These measures significantly reduced both commuter and leisure travel, particularly for long-distance trips between cities. However, as restrictions eased, road travel became a relatively more viable and safer option for inter-city mobility compared to other modes (Abdullah et al., 2020).

Numerous studies have established a negative correlation between the number of confirmed cases and inter-city road travel, with mobility declining significantly during periods of heightened case numbers (Li et al., 2021; Ko et al., 2024). This inverse relationship reflects the public’s behavioral response to health risks as well as the implementation of government-imposed restrictions. During the pandemic, road travel trends were closely aligned with the trajectory of confirmed cases. For example, during periods of rising infections, individuals reduced non-essential travel due to fear of exposure or adherence to public health guidelines (Zheng et al., 2021). Conversely, declines in case numbers often coincided with increased mobility, as public confidence improved and restrictions were eased (Fan et al., 2023). It highlights the bidirectional relationship between mobility and virus spread: while decreased travel volume is related to outbreaks, reduced mobility can help contain pandemic transmission. Previous studies have also explored the spatial heterogeneity of the differential impacts of case numbers. Urban areas with higher population densities and greater economic activities experienced more significant mobility reductions compared to rural regions (Ling et al., 2022). Understanding these relationships is crucial for designing targeted interventions that balance public health goals with the need to maintain economic and social connectivity.

Road infrastructure plays a pivotal role in shaping mobility patterns, particularly during crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic (Uddin et al., 2024). Well-developed road networks facilitate connectivity and enable the movement of goods and people, even amid disruptions to other transportation modes (Tang et al., 2022). During the pandemic, road infrastructure emerged as a critical asset, supporting essential activities such as healthcare delivery, supply chain logistics, and emergency services. At the same time, the pandemic underscored the importance of equitable access to road infrastructure. Regions with inadequate road networks faced greater challenges in ensuring the timely delivery of essential goods and services, exacerbating existing disparities (Uddin et al., 2022).

It is noteworthy that inter-city mobility in China is also influenced by the household registration system and traditional holiday travel (Hu et al., 2024). Gu, et al. (2023) proposed a comprehensive ternary influence framework comprising three levels: short-term tourism mobility, long-term migration tendency, and transportation conditions. The framework was used to analyze the stabilization patterns and driving mechanisms of cyclical inter-city mobility in China from 2015 to 2019. Since the global outbreak of COVID-19, the pandemic has directly or indirectly diminished population mobility across cities by influencing industrial development and transport connectivity (Li et al., 2021). The stability of this triadic mechanism’s effect on inter-city mobility warrants further exploration.

Spatiotemporal heterogeneity of the pandemic’s impacts

The impacts of COVID-19 on mobility were not static. Each stage of the pandemic was characterized by distinct waves of infection, the emergence of new virus variants, and varying levels of public health interventions. For instance, the early stages of the pandemic were marked by stringent lockdowns and widespread fear, leading to sharp declines in mobility (Nikiforiadis et al., 2022). In contrast, subsequent stages saw more targeted interventions, such as localized lockdowns and vaccine rollouts, which allowed for partial recovery of mobility (Obeid et al., 2024). The emergence of new variants, such as Delta and Omicron, introduced additional complexities. For example, the Omicron wave, despite causing record case numbers, had a less pronounced impact on mobility compared to earlier waves due to widespread vaccine coverage and reduced severity of illness (Djordjevic et al., 2023).

While the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on inter-city mobility and its spatial heterogeneity has been widely studied, and the temporal progression of the pandemic itself has been extensively explored in the field of public health, research addressing the temporal heterogeneity of factors influencing inter-city mobility remains relatively scarce. In terms of research methodology, traditional global regression fails to capture spatial heterogeneity. In response, geographically weighted regression (GWR) models take spatial non-stationarity into account. Multiscale geographically weighted regression (MGWR) models are the extension of GWR models that can identify multiscale spatial heterogeneity (Fotheringham et al., 2017). However, MGWR is unable to incorporate the time dimension of the panel data. MGTWR solves this problem by simultaneously using spatial and temporal bandwidths for each variable, which can analyze the scale-dependent spatial and temporal heterogeneity of factors influencing intercity mobility (Yu and Fotheringham, 2024).

In response to the existing research gaps, using comprehensive confirmed diagnosis data and Amap mobility data spanning the entire pandemic period, this research provides an in-depth analysis of the dynamic relationships between inter-city road travel and key influencing factors. Specifically, the study emphasizes whether and how confirmed case numbers and road infrastructure impacted road travel across different stages of the pandemic. By adopting a stage-based perspective, this research seeks to uncover the nuanced, stage-dependent effects of these factors, addressing the temporal heterogeneity that has been underexplored in prior studies. The MGTWR model is employed to analyze the spatiotemporal bandwidths of different influencing factors.

Research framework

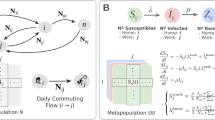

We have established a research framework to analyze the changes in inter-city mobility during different stages of the pandemic (Fig. 1). We first divide the COVID-19 pandemic into several stages and then establish models to explore the influencing factors. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, inter-city road travel dynamics were influenced by a complex interplay of factors, including the pandemic factor, road infrastructure, population mobility motivations, and other external factors.

Analysis framework for inter-city mobility of road travel. This figure describes the analysis framework for inter-city mobility of road travel, which aims to explore the temporal variation, spatial variation, and spatio-temporal heterogeneity of inter-city mobility, with a specific process that includes three major parts: COVID-19 stage division, model exploration, and analysis of influence mechanisms.

Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been significant variation in the number of confirmed cases and the probability of disease occurrence across different Chinese cities, profoundly impacting initial mobility patterns. The implementation of travel restrictions, quarantine measures, and health certification requirements further complicated inter-city travel, leading to a sharp decline in mobility during peak outbreak periods. It is, therefore, essential to investigate how the evolving COVID-19 situation has influenced inter-city mobility dynamics across various pandemic stages (Li et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2022; Ko et al., 2024; Fan et al., 2023).

Road infrastructure and connectivity of cities also play a crucial role in facilitating and shaping inter-city road travel. Areas with more developed road networks and better accessibility to major arterial roads and expressways generally exhibit higher degrees of inter-city road travel. In addition, well-maintained functioning highways can reduce travel time and further encourage more intercity mobility (Tang et al., 2022; Uddin et al., 2022).

In the Chinese context, inter-city mobility is driven by two primary motivations: tourism-driven factor and migration-driven factor. Tourism mobility, encompassing both leisure and business travel, typically involves high-frequency, short-duration inter-regional travel characterized by fluidity and flexibility (Gu et al., 2023; Lin et al., 2020). Conversely, migration tendencies, such as seeking stable employment or pursuing cross-city educational opportunities, represent more prolonged inter-city mobility trends. A significant portion of this migrant population engages in circular, round-trip travel between their destination and origin cities, particularly during major holidays like the Spring Festival, exhibiting a high degree of stability (Gu et al., 2023).

Additionally, the research framework incorporates the influence of other city-specific characteristics, such as population size, economic development level, air quality, land area, and fiscal policies, as these factors can exert varying degrees of influence on migrant populations and their mobility preferences, leading to spatial heterogeneity in observed patterns. For example, large cities with higher levels of economic development tend to attract more migrants because of better job opportunities and amenities (Simini et al., 2012, 2021; Zhao et al., 2023; Yu et al., 2024); while cities with poor air conditions and limited space for urban development may discourage long-term settlement (Cui et al., 2019; Rodrigues et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2020; Tsuboi et al., 2022). Fiscal policies, such as transportation or housing subsidies, can also shape mobility patterns by making certain cities more attractive to migrants (Martin et al., 2012).

The framework aims to elucidate the complex spatial and temporal heterogeneity in inter-city road travel patterns across different pandemic stages, accounting for the multifaceted factors that shape these dynamics.

Methods

Research data and variable design

The source of the inter-city road travel data is the actual migration index of the cities, which is published daily by Amap, China’s leading road navigation system. Since the original index is a floating-point value, we multiplied each city index by 3600 to obtain an integer, ensuring the minimum difference between each index is 1. Subsequently, the data was adjusted according to the ratio of monthly active users across different years to eliminate the error caused by the difference in the number of users, thus allowing for a comparison of the flow volume across stages. Following the data comparison, we observed that the corrected migration index aligned with the number of monthly active users of Amap, showing the same magnitude of variation. Consequently, the corrected migration index could serve as an approximation for the actual number of road trips. The migration indices for each city were aggregated to determine the inflow volume and outflow volume, and subsequently summed to calculate the total road mobility volume for each city. The cartogram map method, wherein the geometries of regions are distorted proportionally to their numeric values, was employed to analyze the regional variability characteristics in inter-city road travel across each stage.

The pandemic data were obtained from the number of COVID-19 cases released daily by the national and local health commissions, spanning from 2020/01/20 to 2022/12/06. These pandemic data were then matched with the mobility data to yield a dataset comprising 345 cities for spatial analysis. The data sources for other variables are listed in Table 1. Due to the lack of statistical data in some cities, a final sample comprising 291 cities was aggregated and utilized for analysis.

Drawing from existing literature (Gu et al., 2023) and the research framework described in the supplementary materials, we employed the number of daily new COVID-19 cases (CASE) to delineate the pandemic status, the density of expressways (DEW) to delineate the road infrastructure of cities, the number of 5A scenic spots (TOUR) and the difference between resident and registered population (FLOW) in each city to signify short-term tourism mobility and long-term migration tendency, respectively. The city’s resident population (POP), per capita GDP (GDP), air quality index (AQI), population density (DENS), and fiscal expenditure to fiscal revenue ratio (FISCAL) represented various external factors, including population size, economic level, environmental quality, land space, and fiscal policy of the city. The variables are presented in Table 1. The variance inflation factors (VIFs) of each variable in the four stages were below 3, signifying the absence of multicollinearity among the selected factors.

Pandemic stage division

We categorized the study period into four stages based on the tendency of daily COVID-19 confirmed cases in China (Table 2), each characterized by distinct pandemic dynamics and responses.

STAGE 1 (First Wave) spanned from January 20 to April 28, 2020, with the outbreak centered in Wuhan, Hubei Province. During this period, Hubei enforced city lockdowns and traffic regulations, significantly impacting mobility across all cities nationwide due to the COVID-19 virus, leading to a cumulative total of 82,118 cases.

STAGE 2 (Under Control) began on April 29, 2020, marking a phase where the spread of the local pandemic centered in Wuhan was effectively halted. Restrictions on leaving Hubei were lifted, and with no new pneumonia cases reported in Wuhan hospitals, most parts of the city resumed normal operations as they were before the outbreak. Apart from major cities like Beijing, Tianjin, and Shanghai, other regions experienced minimal large-scale outbreaks, resulting in a decrease in nationwide COVID-19 cases to 6,750 during this stage.

STAGE 3 (Delta) started on May 21, 2021, when the first case of infection with the Delta variant was identified in mainland China. The Zero-COVID policy still persisted. This period was marked by sporadic outbreaks in typical cities, including Jilin, Changchun, Shanghai, Beijing, and Tianjin. The nationwide number of COVID-19 cases was 6,654, showing no significant increase compared to STAGE 2 (Under Control).

STAGE 4 (Omicron) commenced on December 16, 2021, coinciding with the identification of the first locally acquired infection of the Omicron variant, and concluded on December 6, 2022. This stage saw China convening a session of the Political Bureau of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China, which announced the “New Ten Rules” for optimizing pandemic control measures the next day. The zero-COVID policy has been adjusted to a dynamic zero-COVID one. Characterized by the highly increased transmissibility but greatly reduced mortality rate of the virus, this stage had a notably higher probability of outbreaks in major cities, culminating in a total of 242,047 COVID-19 cases.

The MGTWR model

We utilized the MGTWR model to explore the spatiotemporal heterogeneity of how inter-city mobility was affected at different pandemic stages. MGTWR is a panel data extension of Geographically Weighted Regression (MGWR) and a multiscale heterogeneous extension of classic panel data models. It analyzes panel data by incorporating both geographic and temporal weights into the regression model, allowing for the identification of localized and time-specific patterns that may be overlooked by traditional regression techniques.

The MGTWR method assigns different weights to the spatial and temporal dimensions of the data, with the aim of capturing the varying influences of geographic and temporal factors on the dependent variable. It borrows data from both space and time by using covariate-specific spatial bandwidths and temporal bandwidths, which serve as indicators of spatial and temporal scale, respectively. This approach is particularly useful for analyzing complex, dynamic systems that exhibit spatial and temporal heterogeneity, as it can provide valuable insights into the underlying processes driving the observed patterns and trends. An MGTWR model can be formulated as:

where for location \(i\in \{\mathrm{1,2},\ldots ,n\}\) in time period \(t\in \{\mathrm{1,2},\ldots ,T\}\), \({y}_{{it}}\) is the response variable, \({x}_{{ijt}}\) is the jth predictor variable in time period \(t,j\in \{1,2,\ldots ,k\}\), \({\beta }_{{itj},{{bw}}_{j}}\) is the parameter for location i in time period t, \({{bw}}_{j}\) in \({\beta }_{{itj},{{bw}}_{j}}\) indicates the spatiotemporal bandwidth vector (\({{bw}}_{j}^{S}\), \({{bw}}_{j}^{T}\)) used for the calibration of the jth conditional relationship. \({{bw}}_{j}^{S}\) denotes the spatial bandwidth for the jth covariate, \({{bw}}_{j}^{T}\) is the temporal bandwidth for the jth covariate, and \({\varepsilon }_{{it}}\) is the error term.

The MGTWR model was calibrated using the back-fitting algorithm, an iterative procedure employed in statistical modeling and machine learning to estimate the parameters of a model. The algorithm involves iteratively updating the estimates of model parameters, typically by focusing on one parameter at a time while holding others fixed. In this study, we innovatively estimate the optimal bandwidth of the MGTWR model. In this study, we employs the method proposed by Yu and Fotheringham (2024) to estimate MGTWR. The specific details of the model are provided in the supplementary materials.

Results

Mobility pattern changes at different pandemic stages

Despite the varying impacts of the pandemic across different stages, the overall spatial structure of inter-city road travel in China remained relatively stable (Fig. 2). The primary hubs of inter-city mobility consistently centered around the three major mega city regions: the Yangtze River Delta, the Pearl River Delta, and the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region. These megacity regions, alongside key provincial capitals and central cities in the mid-western provinces, maintained significant volumes of daily inter-city road travel throughout all stages of the pandemic. Conversely, most other cities exhibited comparatively weaker inter-city mobility patterns. This stability underscores the resilience of China’s core urban networks, which continued to dominate the nation’s road travel landscape even amid the pandemic’s disruptions.

a–e Layered color visualization, f–j Cartogram map visualization. This figure describes the spatial characteristics of daily inter-city mobility of road travel in various cities in China at different stages, while the Cartogram maps are used to show the distorted characteristics of inter-city mobility in each city to demonstrate the differential relationship of inter-city mobility.

The pandemic’s impact on inter-city road travel was heterogeneous across cities of different sizes (Supplementary Table S1). Megacities experienced the most substantial declines in road travel, reflecting their higher susceptibility to pandemic-related disruptions due to greater population densities and economic activities. Small cities also faced significant reductions in inter-city mobility, albeit to a lesser extent. In contrast, medium-sized cities demonstrated relatively smaller declines in road travel, indicating a more resilient response to the pandemic. This differential impact highlights the varying degrees of vulnerability and adaptability among cities, shaped by their unique demographic and economic profiles.

The temporal analysis revealed that STAGE 1 and STAGE 4 exerted the most pronounced effects on inter-city road travel, each characterized by distinct patterns of mobility disruption (Fig. 3). During STAGE 1, the initial outbreak centered in Wuhan led to stringent lockdowns and widespread travel restrictions, resulting in a significant nationwide decline in road travel. Inter-city mobility experienced a drastic decline, especially in Wuhan and other cities within Hubei Province. STAGE 4, marked by the emergence of the Omicron variant and subsequent policy adjustments, also saw substantial reductions in mobility, particularly in the Yangtze River Delta and Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei regions. In contrast, STAGE 2 and STAGE 3 exhibited relatively moderate impacts, with some regions even experiencing increases in road travel as restrictions eased and local outbreaks were effectively managed. These temporal variations underscore the dynamic and evolving nature of the pandemic’s influence on-road travel.

Spatiotemporal heterogeneity in the influences of cases and road infrastructure

We employed the MGTWR model to analyze how different factors influence inter-city road travel, emphasizing their spatiotemporal heterogeneity. The model exhibited better performance than the OLS model and the MGWR model (Supplementary Table S2). Our findings reveal significant variations in the impact of the factors across different pandemic stages. Among them, COVID-19 status (CASE) and road infrastructure (DEW) exhibited markedly different effects at different stages.

The negative impact of COVID-19 status on inter-city road travel exhibited distinct variations across the four pandemic stages (Fig. 4). During STAGE 1, the most substantial inhibitory effects were concentrated around Hubei Province and the southeastern coastal provinces, with Guangdong and Guangxi experiencing the strongest restrictions. This stage, characterized by the initial outbreak, saw severe travel limitations due to stringent lockdown measures. In contrast, STAGE 2 witnessed a significant decrease in confirmed cases, resulting in negligible impacts on inter-city road travel, reflecting a period of recovery as restrictions were eased. STAGE 3 marked a narrowing of the impact scope to the Pearl River Delta and surrounding areas, as well as Tianjin and its neighboring cities. Although the geographical scope of the impact diminished, the localized effects were more intense, indicating concentrated outbreaks that severely disrupted travel. By STAGE 4, the influence of COVID-19 status was primarily along the eastern seaboard, excluding the core area of the Yangtze River Delta. The Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei urban agglomeration and its peripheries experienced the strongest inhibitory effects due to heightened transmission risks and stringent containment policies. These observations indicate that, although the pandemic constitutes a nationwide event, its impact on mobility is spatially more confined to limited areas where outbreaks are prominent. As governments develop more targeted strategies and populations adapt to pandemic conditions, the spatial extent of the pandemic’s influence on mobility has noticeably diminished. Specifically, during STAGE 3 and STAGE 4, the negative impacts associated with the pandemic were restricted to smaller geographic areas compared to STAGE 1, highlighting the effectiveness of localized containment measures and adaptive behaviors.

a–d COVID-19 status, represented by the number of daily new COVID-19 cases (CASE), (e–h) Road infrastructure, represented by the density of expressways (DEW). This figure describes the results of MGTWR models, which show the spatial heterogeneity of the impact of COVID-19 status and road infrastructure on inter-city mobility of road travel in China at different stages.

The influence of road infrastructure on inter-city road travel also exhibited notable stage-specific changes. During the severe pandemic conditions of STAGE 1 and STAGE 4, the impact of transportation conditions was predominantly concentrated within Guangdong Province, with diminishing effects outward. This is attributable to Guangdong’s extensive urban scale and comprehensive transportation networks, which facilitate inter-city travel despite restrictive measures. Conversely, during the relatively mild pandemic phases of STAGE 2 and STAGE 3, the influence of road infrastructure extended across most regions of China. Enhanced road networks promoted greater mobility, especially in areas with robust transportation infrastructure. The stage-specific variations in road density further reveal that as the pandemic progressed into its middle and later phases, the role of transportation infrastructure in facilitating mobility became increasingly pivotal. Particularly during the relatively stable and normalized management periods of STAGE 2 and STAGE 3, both the magnitude and spatial extent of these effects became more pronounced. This underscores previous scholarly assertions regarding the critical function of transportation infrastructure in safeguarding the flow of people and goods during pandemics (Uddin et al., 2024; Tang et al., 2022; Uddin et al., 2022). It also highlights how well-developed infrastructures can mitigate the adverse effects of such global health crises by ensuring continued mobility even under restrictive conditions.

Other influencing factors

In addition to the impacts of COVID-19 status and road infrastructure on inter-city road travel, our analysis identified several other influential factors (Supplementary Figs. S1–S3). The difference was that the spatial heterogeneity exhibited by the influential role of these factors at different stages did not change significantly. These factors included tourism-driven factor (TOUR), migration-driven factor (FLOW), and various city characteristic variables such as population size (POP), economic levels (GDP), air quality index (AQI), population density (DENS), and fiscal policy (FISCAL).

Tourism-driven factors and migration-driven factors have been seen as key factors related to inter-city mobility (Lao et al., 2022; Shen, 2015). Their influence on inter-city road travel demonstrated stable spatial patterns across different stages of the pandemic. TOUR notably impacted the three major megacity regions. Specifically, TOUR exerted a positive effect on road travel in the Yangtze River Delta and Pearl River Delta, indicating a strong attraction for short-term travel in these economically vibrant regions. Conversely, TOUR negatively impacted road travel in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region and its surroundings, suggesting different dynamics at play, potentially due to stricter travel restrictions or less tourism appeal.

For migration tendency, which is represented by FLOW, the primary influence was observed in central and southern China, with Guangdong Province emerging as the most significantly impacted region. Guangdong’s robust economic development attracted long-term migrants from neighboring cities, while its influence diminished with increasing distance. This pattern underscored Guangdong’s role as a magnet for regional migration, driven by its economic opportunities.

The impact of various city characteristic factors on inter-city road travel revealed significant spatial heterogeneity, which remained generally stable across pandemic stages. Population and economic size have been widely used in gravity models to predict travel volumes (Zhao et al., 2023). POP positively affected inter-city road travel nationwide, with the most substantial effects observed in North China and South China. GDP predominantly had negative impacts on road travel in and around Guangdong Province. This counterintuitive finding may be attributed to the region’s higher susceptibility to COVID-19 disruptions, which more profoundly affected economically developed areas.

The differential impact of AQI suggested that economically developed regions were more sensitive to environmental quality. As evidenced by our findings in the Pearl River Delta, poor air quality has been identified as a factor that potentially restricts travel willingness, which is consistent with previous studies (Rodrigues et al., 2021). However, contrasting results were observed in the Yangtze River Delta, which exhibited an opposite trend. This discrepancy can be attributed to the Yangtze River Delta’s characteristics as a densely populated region with more developed heavy industries. In this area, the deterioration of air quality is often associated with high-intensity economic activities. Such economically vibrant conditions may correlate with increased inter-city mobility, as the impetus for economic engagement and the necessity for business travel remain significant despite environmental challenges. Population density has been seen as a significant factor related to pandemics (Dalziel et al., 2018; Hazarie et al., 2021). DENS inhibited road travel in the densely populated southeastern coastal region but facilitated it in the less populated western inland areas, which reflected the limited land availability in eastern China and the relatively sparse population in the west, influencing travel patterns accordingly. The pronounced effects of FISCAL in larger city regions indicated that fiscal measures were more influential in regions with significant urban and economic activities.

Variation characteristics of scale effects

The MGTWR analysis demonstrated significant spatial heterogeneity in the factors affecting inter-city road travel. As can be seen in Fig. 5, the spatial bandwidths of all variables were less than 100, indicating that their effects stabilized within a range of 100 cities. This suggested that the spatial influence of these variables did not extend beyond this range, underscoring the importance of regional contexts. The spatial bandwidths for both CASE and DEW were 84. This corresponded to the number of cities in several adjacent provinces, reflecting that these factors primarily influenced neighboring provinces. The spatial clustering of COVID-19 impacts and transportation networks reinforced the interconnectedness of provinces during the pandemic. The spatial bandwidth for other variables was 29. This bandwidth aligned with the number of cities within one to two provinces, indicating that their effects were more localized. These variables tended to stabilize within provincial boundaries, reflecting localized impacts on-road travel.

The temporal bandwidths of variables were categorized into three scales, indicating the duration over which their impacts remained stable. Both CASE and DEW had a temporal bandwidth of 1, suggesting their impacts on road travel were stable over a single stage. This highlighted the immediate and fluctuating nature of pandemic-related influences and transportation conditions on travel patterns. POP exhibited a temporal bandwidth of 2, indicating stability over two stages. This reflected the enduring influence of population concentration on road travel dynamics. The temporal bandwidths for GDP, AQI, DENS, and FISCAL were all 3, demonstrating that their effects remained consistent across all pandemic stages. These variables exhibited long-term stability in their influence on road travel, regardless of the pandemic’s progression.

An inverse relationship was observed between the spatial and temporal bandwidths of the influencing factors. Variables with higher spatial heterogeneity tended to have more immediate and variable impacts, resulting in smaller temporal bandwidths. Conversely, variables with lower spatial heterogeneity exhibited more stable impacts across longer temporal scales.

Conclusion and discussion

This study provides a comprehensive examination of the spatial and temporal heterogeneity of inter-city road travel in China during different stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. Our findings reveal nuanced insights that extend beyond the scope of previous macroscopic studies (Kraemer et al., 2020; Li et al., 2022; Gibbs et al., 2020). By employing the MGTWR model, we uncover the dynamic and non-stationary impacts of road infrastructure and COVID-19 status on inter-city road travel, thus advancing the analytical framework for understanding travel dynamics over multiple periods.

Our findings indicate that inter-city road travel patterns mirrored the phased nature of the COVID-19 pandemic, manifesting as a falling-rising-stabilizing-falling trajectory. During STAGE 1 (First Wave), at the onset of the outbreak, national mobility significantly decreased, particularly around Wuhan and several populous megacity regions, aligning with prior studies on pandemic-induced mobility reductions (Sung et al., 2023; Sasidharan et al., 2020; Ko et al., 2024). Following stringent travel restrictions, mobility rebounded sharply in STAGE 2 (Under Control), surpassing pre-pandemic levels as control measures proved effective. In STAGE 3 (Delta), despite the emergence of new variants, China’s containment strategies maintained stability in mobility. However, during STAGE 4 (Omicron), existing control measures struggled to contain the rapid viral spread, necessitating stricter local interventions and consequently leading to another decline in mobility.

A pivotal discovery of our study is that the negative impact of pandemic cases on inter-city road travel exhibits both temporal stage-specific variations and spatial regional differences. Previous research has often overlooked the significance of temporal heterogeneity when examining spatial disparities (Gu et al., 2023). Specifically, during periods dominated by the Delta variant, characterized by higher virulence but lower transmissibility compared to the Omicron variant, the adverse effects were more pronounced yet spatially confined; conversely, despite large-scale outbreaks of the Omicron variant being concentrated in a few cities like Shanghai, its impact on mobility extended over a broader geographic area. This dual spatiotemporal non-stationarity not only applies to the effects of COVID-19 but also suggests similar characteristics may be observed in future public health emergencies affecting mobility.

Another key finding is the stage-specific influence of road infrastructure on inter-city road travel during the pandemic. Unlike the pandemic cases, while the magnitude of influence varied across stages, the spatial pattern of road infrastructure’s facilitative role remained relatively consistent, with greater prominence observed in South China. The stage-specific differences primarily manifested as more pronounced effects during relatively stable and controllable pandemic periods.

Furthermore, we identified an inverse relationship between spatial and temporal bandwidths, which constitutes a novel contribution to the application of the MGTWR method. Prior studies have not adequately analyzed the relationship between these two bandwidths. Specifically, we found that factors with broader spatial impacts, such as COVID-19 cases and expressway density, tend to exhibit shorter temporal durations.

The observed spatiotemporal non-stationary nature of these impacts necessitates a more nuanced approach to policy and planning, as one-size-fits-all measures are unlikely to be effective across diverse regions and time periods (Thombre and Agarwal, 2021; Wang et al., 2022). Specifically, the stage-specific influences of the pandemic we observed suggest that comprehensive containment measures can effectively confine the restrictions on inter-city mobility to relatively limited geographic areas. Consequently, it is advisable to avoid imposing overly stringent travel restrictions in unaffected regions, instead aiming to minimize and precisely target the geographical scope and time length of such interventions. This observation corroborates the success of China’s strategy in delineating risk zones for targeted travel restrictions (Cheng et al., 2023). Furthermore, given our findings on the broader facilitative role of road infrastructure on mobility during the intermediate stages of the pandemic, we recommend enhancing the planning, construction, and maintenance of road infrastructure. Our study highlights that in economically vibrant South China, road infrastructure plays a particularly crucial role, suggesting that road investment should prioritize economically active areas rather than enforcing absolute spatial equality.

Despite the robust findings, this study faces several limitations that warrant further investigation. Inconsistencies in pandemic data reporting, such as underreporting of cases in some regions of China, could lead to an underestimation of the pandemic’s true impact. Asymptomatic infected individuals and some self-tested positive cases are not counted as confirmed cases, so the total number of confirmed cases may underestimate the actual figure, particularly during STAGE 4, when viral virulence is significantly heightened. Future research should address these limitations by incorporating more comprehensive data and conducting robustness checks. Moreover, extending the study period beyond December 2022 to include the post-pandemic phase would enhance our understanding of the long-term effects of lifted travel restrictions.

Data availability

The data generated during this study are described in the supplementary materials for this paper. The dependent variables can be directly obtained from the official statistical yearbooks of China described in this paper or provided by the authors upon request. The authors confirm that no individual privacy information is included.

References

Abdullah M, Dias C, Muley D, Shahin M (2020) Exploring the impacts of COVID-19 on travel behavior and mode preferences. Transp Res Interdiscip Perspect 8:100255

Beria P, Lunkar V (2021) Presence and mobility of the population during the first wave of Covid-19 outbreak and lockdown in Italy. Sustain Cities Soc 65:102616

Borkowski P, Jażdżewska-Gutta M, Szmelter-Jarosz A (2021) Lockdowned: everyday mobility changes in response to COVID-19. J Transp Geogr 90:102906

Chang M-C et al. (2021b) Variation in human mobility and its impact on the risk of future COVID-19 outbreaks in Taiwan. BMC Public Health 21:226

Chang S et al. (2021a) Mobility network models of COVID-19 explain inequities and inform reopening. Nature 589:82–87

Charoenwong B, Kwan A, Pursiainen V (2020) Social connections with COVID-19–affected areas increase compliance with mobility restrictions. Sci Adv 6:eabc3054

Chen J, Guo X, Pan H, Zhong S (2021) What determines city’s resilience against epidemic outbreak: evidence from China’s COVID-19 experience. Sustain Cities Soc 70:102892

Cheng ZJ et al. (2023) Public health measures and the control of COVID-19 in China. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 64:1–16

Chu Z, Cheng M, Song M (2021) What determines urban resilience against COVID-19: City size or governance capacity? Sustain Cities Soc 75:103304

Cui C et al. (2019) Escaping from pollution: the effect of air quality on inter-city population mobility in China. Environ Res Lett 14:124025

Dalziel BD et al. (2018) Urbanization and humidity shape the intensity of influenza epidemics in U.S. cities. Science 362:75–79

Djordjevic M, Markovic S, Salom I, Djordjevic M (2023) Understanding risk factors of a new variant outburst through global analysis of Omicron transmissibility. Environ Res 216:114446

Dueñas M, Campi M, Olmos LE (2021) Changes in mobility and socioeconomic conditions during the COVID-19 outbreak. Hum Soc Sci Commun 8:101

Echaniz E et al. (2021) Behavioural changes in transport and future repercussions of the COVID-19 outbreak in Spain. Transp Policy 111:38–52

Fan X, Lu J, Qiu M, Xiao X (2023) Changes in travel behaviors and intentions during the COVID-19 pandemic and recovery period: a case study of China. J Outdoor Recreat Tour 41:100522

Fatmi MR (2020) COVID-19 impact on urban mobility. J Urban Manag 9:270–275

Ferreira S et al. (2022) Travel mode preferences among German commuters over the course of COVID-19 pandemic. Transp Policy 126:55–64

Fotheringham AS, Yang W, Kang W (2017) Multiscale Geographically Weighted Regression (MGWR). Ann Am Assoc Geogr 107:1247–1265

Gardner LM, Bóta A, Gangavarapu K, Kraemer MUG, Grubaugh ND (2018) Inferring the risk factors behind the geographical spread and transmission of Zika in the Americas. PLOS Negl Trop Dis 12:e0006194

Gibbs H et al. (2020) Changing travel patterns in China during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. Nat Commun 11:5012

Gu H, Shen J, Chu J (2023) Understanding intercity mobility patterns in rapidly urbanizing China, 2015–2019: evidence from Longitudinal Poisson Gravity Modeling. Ann Am Assoc Geogr 113:307–330

Gu H, Yu H, Sachdeva M, Liu Y (2021) Analyzing the distribution of researchers in China: an approach using multiscale geographically weighted regression. Growth Change 52:443–459

Gu L et al. (2022) Understanding the spatial diffusion dynamics of the COVID-19 pandemic in the city system in China. Soc Sci Med 302:114988

Hazarie S, Soriano-Paños D, Arenas A, Gómez-Gardeñes J, Ghoshal G (2021) Interplay between population density and mobility in determining the spread of epidemics in cities. Commun Phys 4:191

Hotle S, Mumbower S (2021) The impact of COVID-19 on domestic U.S. air travel operations and commercial airport service. Transp Res Interdiscip Perspect 9:100277

Hou X et al. (2021) Intracounty modeling of COVID-19 infection with human mobility: assessing spatial heterogeneity with business traffic, age, and race. Proc Natl Acad Sci 118:e2020524118

Hu H, Shen J, Gu H, Zhang J (2024) Identifying the spatio-temporal dynamics of mega city region range and hinterland: a perspective of inter-city flows. Comput Environ Urban Syst 112:102146

Iacus SM et al. (2020) Human mobility and COVID-19 initial dynamics. Nonlinear Dyn 101:1901–1919

Ko E, Lee S, Jang K, Kim S (2024) Changes in inter-city car travel behavior over the course of a year during the COVID-19 pandemic: a decision tree approach. Cities 146:104758

Kraemer MUG et al. (2020) The effect of human mobility and control measures on the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Science 368:493–497

Lai S et al. (2020) Effect of non-pharmaceutical interventions to contain COVID-19 in China. Nature 585:410–413

Lao X et al. (2022) Comparing intercity mobility patterns among different holidays in China: a big data analysis. Appl Spat Anal Policy 15:993–1020

Lee K-S, Eom JK (2024) Systematic literature review on impacts of COVID-19 pandemic and corresponding measures on mobility. Transportation 51:1907–1961

Li T, Cui L, Wang J (2022) New equilibrium? Dynamics of intercity mobility in China during COVID-19 pandemic period. J Transp Geogr 105:103478

Li T, Wang J, Huang J, Yang W, Chen Z (2021) Exploring the dynamic impacts of COVID-19 on intercity travel in China. J Transp Geogr 95:103153

Li Z, Wei Z, Zhang Y, Kong X, Ma C (2023) Applying an interpretable machine learning framework to study mobility inequity in the recovery phase of COVID-19 pandemic. Travel Behav Soc 33:100621

Lin Y-X, Lin B-S, Chen M-H, Su C-H (2020) 5A tourist attractions and China’s regional tourism growth. Asia Pac J Tour Res 25:524–540

Ling L, Qian X, Guo S, Ukkusuri SV (2022) Spatiotemporal impacts of human activities and socio-demographics during the COVID-19 outbreak in the US. BMC Public Health 22:1466

Liu X et al. (2023) Quantifying COVID-19 recovery process from a human mobility perspective: an intra-city study in Wuhan. Cities 132:104104

Manzira CK, Charly A, Caulfield B (2022) Assessing the impact of mobility on the incidence of COVID-19 in Dublin City. Sustain Cities Soc 80:103770

Martin A, Suhrcke M, Ogilvie D (2012) Financial incentives to promote active travel: an evidence review and economic framework. Am J Prev Med 43:e45–e57

Mu X, Yeh AG-O, Zhang X (2020) The interplay of spatial spread of COVID-19 and human mobility in the urban system of China during the Chinese New Year. Environ Plan B Urban Anal City Sci 48:1955–1971

Nikiforiadis A et al. (2022) Exploring mobility pattern changes between before, during and after COVID-19 lockdown periods for young adults. Cities 125:103662

Obeid H et al (2024) Early pandemic behaviors and the role of vaccines in reversing pandemic mobility trends: evidence from a US panel. Transp Res Record, 03611981241249924

OECD (2020) AI-powered COVID-19 watch, https://oecd.ai/covid

Oliver N et al. (2020) Mobile phone data for informing public health actions across the COVID-19 pandemic life cycle. Sci Adv 6:eabc0764

Rodrigues V et al. (2021) How important is air quality in travel decision-making? J Outdoor Recreat Tour 35:100380

Sasidharan M, Singh A, Torbaghan ME, Parlikad AK (2020) A vulnerability-based approach to human-mobility reduction for countering COVID-19 transmission in London while considering local air quality. Sci Total Environ 741:140515

Shakibaei S, de Jong GC, Alpkökin P, Rashidi TH (2021) Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on travel behavior in Istanbul: a panel data analysis. Sustain cities Soc 65:102619

Shaman J, Kohn M (2009) Absolute humidity modulates influenza survival, transmission, and seasonality. Proc Natl Acad Sci 106:3243–3248

Shen J (2015) Explaining interregional migration changes in China, 1985–2000, using a decomposition approach. Reg Stud 49:1176–1192

Sills J et al. (2020) Aggregated mobility data could help fight COVID-19. Science 368:145–146

Simini F, Barlacchi G, Luca M, Pappalardo L (2021) A Deep Gravity model for mobility flows generation. Nat Commun 12:6576

Simini F, González MC, Maritan A, Barabási A-L (2012) A universal model for mobility and migration patterns. Nature 484:96–100

Snoeijer BT, Burger M, Sun S, Dobson RJB, Folarin AA (2021) Measuring the effect of Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions (NPIs) on mobility during the COVID-19 pandemic using global mobility data. npj Digit Med 4:81

Stewart Fotheringham A, Charlton M, Brunsdon C (1996) The geography of parameter space: an investigation of spatial non-stationarity. Int J Geogr Inf Syst 10:605–627

Sung H, Dabrundashvili N, Baek S (2023) Mode-specific impacts of social distancing measures on the intra- and inter-urban mobility of public transit in Seoul during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustain Cities Soc 98:104842

Tang J, Lin H, Fan X, Yu X, Lu Q (2022) A topology-based evaluation of resilience on urban road networks against epidemic spread: implications for COVID-19 responses. Front Public Health 10

The Lancet (2020) COVID-19: learning from experience. Lancet 395:1011

Thombre A, Agarwal A (2021) A paradigm shift in urban mobility: policy insights from travel before and after COVID-19 to seize the opportunity. Transp Policy 110:335–353

Tsuboi K, Fujiwara N, Itoh R (2022) Influence of trip distance and population density on intra-city mobility patterns in Tokyo during COVID-19 pandemic. PLOS ONE 17:e0276741

Uddin S et al. (2024) Road networks and socio-demographic factors to explore COVID-19 infection during its different waves. Sci Rep 14:1551

Uddin S, Khan A, Lu H, Zhou F, Karim S (2022) Suburban road networks to explore COVID-19 vulnerability and severity. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19

Wang J, Du D, Huang J (2020) Inter-city connections in China: high-speed train vs. inter-city coach. J Transp Geogr 82:102619

Wang J, Huang J, Yang H, Levinson D (2022) Resilience and recovery of public transport use during COVID-19. npj Urban Sustain 2:18

Wei Y et al. (2021) Spread of COVID-19 in China: analysis from a city-based epidemic and mobility model. Cities 110:103010

WHO (2020) WHO Collection for Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) outbreak, https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019

Yang W, Chen Q, Yang J (2022) Factors affecting travel mode choice between high-speed railway and road passenger transport—evidence from China. Sustainability 14:15745

You G (2022) The disturbance of urban mobility in the context of COVID-19 pandemic. Cities 128:103821

Yu H et al. (2020) Inference in multiscale geographically weighted regression. Geogr Anal 52:87–106

Yu H, Fotheringham AS (2024) On the calibration of multiscale geographically and temporally weighted regression models. Int J Geogr Inf Sci 1–20

Yu H, Li J, Bardin S, Gu H, Fan C (2021) Spatiotemporal dynamic of COVID-19 diffusion in China: a dynamic spatial autoregressive model analysis. ISPRS Int J Geo-Inf 10

Yu W et al. (2024) Spatiotemporal dynamics and determining factors of intercity mobility: a comparison between holidays and non-holidays in China. Cities 153:105306

Zhang W et al. (2022) Structural changes in intercity mobility networks of China during the COVID-19 outbreak: a weighted stochastic block modeling analysis. Comput Environ Urban Syst 96:101846

Zhang W, Chong Z, Li X, Nie G (2020) Spatial patterns and determinant factors of population flow networks in China: analysis on Tencent Location Big Data. Cities 99:102640

Zhao P, Hu H, Zeng L, Chen J, Ye X (2023) Revisiting the gravity laws of inter-city mobility in megacity regions. Sci China Earth Sci 66:271–281

Zheng D, Luo Q, Ritchie BW (2021) Afraid to travel after COVID-19? Self-protection, coping and resilience against pandemic ‘travel fear’. Tour Manag 83:104261

Zhu P, Guo Y (2021) The role of high-speed rail and air travel in the spread of COVID-19 in China. Travel Med Infect Dis 42:102097

Zhu P, Tan X (2022) Evaluating the effectiveness of Hong Kong’s border restriction policy in reducing COVID-19 infections. BMC Public Health 22:803

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 42301278), the Humanities and Social Sciences Youth Foundation of Ministry of Education of China (No. 23YJC790032), the Young Elite Scientists Sponsorship Program by CAST (No. 2023-2025QNRC001), and the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy (No. PO-661).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Hengyu Gu: conceptualization, data acquisition, methodology, formal analysis, visualization, writing-original draft. Yuhao Lin: writing-original draft. Haoyu Hu: visualization, validation, writing-original draft. Hanchen Yu: methodology, software, writing-review & editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gu, H., Lin, Y., Hu, H. et al. COVID-19 pandemic and road infrastructure exerted stage-dependent spatiotemporal influences on inter-city road travel in China. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 705 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05018-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05018-0

This article is cited by

-

Urban Fire Risk Evaluation Integrating Image Features with Interpretable Machine Learning Models

Applied Spatial Analysis and Policy (2025)

-

Effect of Working Patterns on Spatial Variation in Outdoor Leisure Activity of Fixed-Location Workers: A Case Study of Nanjing, China

Applied Spatial Analysis and Policy (2025)