Abstract

This article investigates the global herding behavior across the housing markets. Using the OECD quarterly data from 1970 to 2022, I find that global herding is contingent on the concurrent interplay between the US price-to-rent regimes and average price changes. Evidence is consistent with the proposed view that global herding is displayed when investors use the pseudo signal flying from the US market for confirmation. I also find that valuation anchors, such as price-to rent and price-to-income, also display correlated behaviors among countries, suggesting the existence of spurious herding as a result of investors’ common responses to changes in fundamental factors. Even after the effects of the fundamental anchors are purged away, evidence on global herding is substantial, suggesting that the global herding behavior is psychological. This article asserts that the global herding behavior is driven by investors’ confirmation bias boosted by coincidence between average price changes and the expectation on the US housing market. The evidence is consistent with the view that investors are overconfident on the noisy public information and the unproven belief concerning the association between the external public signal and ex post house price changes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Despite the non-tradability of housing assets, house prices have remarkably shown a global synchronicity (IMF, 2018). In the recent paper, Alter et al. (2018) confirm the strong correlation in house prices across countries and show that the house price synchronicity is related with global financial conditions, bank integration and business cycle synchronicity. Other studies also point out that US economic cycles and US house prices can be a driver of the comovements in global house prices (Claessens et al. 2011; Yunus, 2015). Thus, the extant studies stress the role of fundamental factors in driving the strong correlations of house prices across countries.Footnote 1 Although cross-country comovements in house prices are explained by the global linkage of fundamentals, however, it is difficult to completely rule out the effect of behavioral biases, such as the trio of herding, overconfidence, and confirmation bias, as a potential culprit of unusual correlations among global housing prices.Footnote 2 Cautiously saying at this preliminary stage, confirmation bias and its resulting global herding could be an underlying suspect of excess correlation among housing markets.

By a simple definition, herding refers to correlated behavior across individuals (Bikhchandani et al. 1992). Herding takes a form of convergent social behavior (Bikhchandani et al. 2024). This can be broadly viewed as the result of the alignment of beliefs or behaviors among individuals. According to information cascades, if investors are pressed by market stress, they may display herding behavior by imitating the actions of those who appear to have expertise like a fashion leader and/or the actions of the majority (Bikhchandani et al. 1992, 1998, 2024). Herding refers to abandoning private information and mimicking the decisions of others without reference to fundamental information. This kind of herding is distinguished from spurious herding (which is passive in nature), which mainly occurs as a result of common responses to changes in fundamental factors (Bikhchandani and Sharma, 2000). Spurious herding may also occur between agents who trade in different countries. By contrast, psychological herding arises when investors feel more safe and secure by following crowds (Devenow and Welch, 1996).Footnote 3 Along the line of this notion, psychological herding is conditional not only on the action of others, but also on investors’ own feeling of the target’s capability to provide a sense of safety and security to investors. Thus, psychological herding may be eclectic in the sense that herding may be related to other biases such as confirmation bias and overconfidence. The first causal chain among the bias trio is grounded on the prediction that confirmation bias causes individuals to display over- or under-confidence (Nickerson, 1998; Just, 2014). The second causal chain is that overconfidence leads individuals to herd (Daniel et al. 1998; Hwang et al. 2021). The integration of two chains reaches a logical argument that confirmation bias drives herding behavior via overconfidence. This implies that overconfidence is a human bias mediating between confirmation bias and herding. This study is motivated by the question of whether and how herding behavior in the housing markets is driven by confirmation bias.

A large body of research has empirically examined the question regarding whether herding behavior is displayed in equity markets. Among others, they include Christie and Huang (1995), Chang et al. (2000), Chiang and Zheng (2010), Galariotis et al. (2015), Bekiros et al. (2017), Chen (2022), Rubesam and Raimundo (2022), Filip and Pochea (2023), and Ferreruela et al. (2024). Herding behavior is also likely to appear in the housing markets, although the law of one price is inherently violated due to the presence of frictions. Housing markets over the world have been inefficient since the markets have various frictions such as high transaction cost, difficulty of short sales, information asymmetry, and illiquidity (Shiller, 2014). Moreover, the housing markets are also characterized by asset heterogeneity and cultural/social characteristics. Such imperfections inherent in the markets inhibit investors from efficient use of information for fair valuation, thereby distorting signals, sprouting various psychological biases such as confirmation bias, overconfidence, and herding. Empirical evidence gets along with the argument that herding behavior is also present in the housing markets. At the micro level, empirical research has shown that herding bias is significantly displayed among institutional investors in REITs (Lantushenko and Nelling, 2017; Freybote and Seagraves, 2017), credit rating agencies in CMBS (An et al. 2020), and residential developers (Ro et al. 2019). At the macro level, empirical studies have also shown that herding behavior is present not only in REITs markets (Zhou and Anderson, 2013; Philippas et al. 2013; Babalos et al. 2015), but also in the direct US housing markets (Ngene et al. 2017; Pollock et al. 2024) and major OECD house markets (Hott, 2012).

Let’s make a brief review of the trio of confirmation bias, overconfidence, and herding. Confirmation bias and overconfidence are among the most widely recognized biases in the psychology literature (Evans, 1989; Nickerson, 1998; Moore and Healy, 2008)Footnote 4. Confirmation bias connotes a human behavior seeking or interpreting of evidence in ways that are partial to existing beliefs, expectations, or a hypothesis in hand (Nickerson, 1998). People with confirmation bias attach too much weight to information that supports positions or views that they are evaluating (Shefrin, 2018), and they show excessive confidence, especially when they should interpret obscure evidence (Einhorn and Hogarth, 1978; Rabin and Schrag, 1999). People favor hypothesis-based filtering using currently-held beliefs (Just, 2014). Moreover, they tend to interpret the statistics of correlation between events in such a way that correlation is overestimated when they have a theory of it (Rabin and Schrag, 1999). Empirical evidence has been consistent with the presence of confirmation bias and its resulting overconfidence (Cipriano and Gruca, 2014; Pouget et al. 2017). Confirmation bias and overconfidence in equity markets have been examined by Friesen et al. (2009) for technical pattern explainable by confirmation bias, Bekiros et al. (2017) for herding induced by overconfidence, Vafaeimehr et al. (2023) for confirmation bias triggered by top IBs, Faia et al. (2024) for evidence of confirmation bias in a survey experiment during the pandemic, Cai et al. (2024) for confirmation bias displayed by sell-side analysts, and Sun et al. (2024) for herding behavior among retail investors influenced by market memory and confirmation bias. Overconfidence bias in housing markets has been examined by Lin et al. (2010) for investor overconfidence in REITs, Hayunga and Lung (2011) for overconfidence under inflation illusion, Eicholtz and Yönder (2015) for CEO overconfidence in the REITs, Hwang et al. (2020) for household’s overconfidence on public information, and Bao and Li (2020) for overconfidence in Asia-Pacific REITs. Confirmation bias in housing markets has been studied by Eriksen et al. (2020) for contract price confirmation bias in appraisals and Lee et al. (2022) for overconfidence and confirmation bias among evaluators. However, relatively a few have addressed the effect of overconfidence on herding or the effect of confirmation bias on herding. To the best of my knowledge, the only exception is Pollock et al. (2024) who examine the relationship between overconfidence and reverse herding.

This review finds four important voids from extant literature, which are required to be developed further. Firstly, most studies have neglected the possibility that herding behavior is combined with other behavioral bias. As noted, it is difficult to find out the research about whether herding is associated with confirmation bias in housing markets. As I suspect, this issue is potentially associated with the question of why herding behavior has revealed asymmetrically between up and down markets or regime-dependent (Zhou and Anderson, 2013; Pollock et al. 2024). This article is intrigued by this question why downside herding in the down market differs from upside one in the up market. Confirmation bias may be an alternative explanation of why downside herding is distinct from upside one.

Secondly, existing studies neglected the question of whether herding behavior is detected in fundamental anchors other than returns. In this regard, it is worth noting the statement by Christie and Huang (1995) that “failure to detect herd behavior may reflect the tendency of herds to form around indicators other than the average consensus of all participants.” The most popular indicators for valuation in the housing market are the ratios of price-to-rent (PTR) and price-to-income (PTI). PTR is the ratio of house prices to annualized rent, which is used to assess whether owning houses is cheaper relative to rent. PTI is the ratio of house prices to disposable income per capita, which is used to measure the affordability of housing at a given income level. Two indicators are in practice widely used in relative valuation. The ratio PER is perceived to be a quantitative (valuation) anchor for stock investment (Shiller, 2000). Likewise, PTR is viewed as a valuation anchor for housing investment. According to expectation theory, PTR is informative of whether current house price is fairly valued relative to rent. PTI is indicative of whether current house price is properly valued relative to current income. Accordingly, PTR and PTI are construed as the valuation indicators of the extent of economic fundamentals that are reflected in house prices. Since herding in valuation anchors may arise from the convergence in fundamentals between countries, convergent behaviors in PTR and PTI among countries is interpretable as evidence of spurious herding, according to the notion of Bikhchandani and Sharma (2000). For exact inference on psychological herding, therefore, the spurious portion should be controlled away.

Thirdly, the majority of studies have focused on the analysis of herding behavior based on ex-post states of up and down, which are unrelated to expectations. Thus, it is desirable to divide the partition of state space based on an indicator that reflect investors’ expectations on the prospect of housing markets. From a theoretical viewpoint, PTR is construed as a proxy that can reflect market expectation in housing markets. The indicator reflects investors’ expectation or perception about future changes in rents. Under the existence of transaction costs, investors may hold divergent expectation on the pricing status of housing markets, depending on whether investment benefits exceed transaction cost or not. Thus, herding behavior should be differentiated according to the regimes in which investors are located, more specifically, according to whether benefits exceed transaction costs or not. Note that cascade theory also considers costs as a factor of herding by stating that cascades can form instantly when individuals have to pay a fixed cost to obtain private signals (Bikhchandani, et al. 1998). Mapping the theoretical equation of PTR to the historical data, one can identify the threshold point of expectation change and partition price regimes before and after the break. The partitioning of state-space can help us precisely assess the regime-dependent herding behavior.

Fourthly, extant studies have analyzed herding behavior within an individual country’s housing market, but not in the global setting. In particular, little is known about whether global herding occurs across housing markets and whether it is entirely psychological or not. The subprime mortgage crisis and subsequent global financial crisis can be a showcase that shocks in the US housing market rapidly spill over to the rest of world. As indicated by Shiller (2008), the ultimate cause of the global financial crisis might be the psychology of the real estate bubble. Thus, it is essential to analyze the nature of global herding across housing markets, particularly from a psychological viewpoint. Furthermore, it is necessary to answer the question why the US market is viewed as the pied piper who attracts herds in the global housing market. The pied piper is usually described as a figure who attracts people with weird (‘pied’) wears and noisy sounds of “pipe” (Christie and Huang, 1995). Herding behavior could be invited by public impression or something special on a leader. A public signal flying from the US may play a role as an attractor of herds.

By filling the gaps, this article contributes to herding literature. The major objective is to make novel inference on the global herding driven by confirmation bias. This study proposes a descriptive model in which psychological herds are driven by the pseudo-signal from a neighbor country (say, a leader) for confirmation. The proposed model is distinct from Daniel et al. (1998), claiming that due to biased self-attribution an investor’s confidence grows when public information is aligned with his private information. In contrast, the present study assumes the presence of investors susceptible to confirmation bias, who hold a vague belief that the leader’s (over- or under-valued) market status is transplanted to their own markets. In this model, investors are concerned about whether average price changes coincide with the public information of the expectation on the US market. Exposed to market stress, they exercise the option to herd (imitate others) when average price changes are confirmed by a pseudo-signal drawn from expectation of leader’s price regime. On obtaining confirmation, investors are overconfident and dare to mimic the behavior of the US market. However, when average price changes are not confirmed by the expectation on the US market, investors are underconfident and their intention to mimic is discouraged. Hence, herding behavior heavily depends on whether there is the match between average price changes and the condition of the US market as the pied piper. The better qualified the pied piper is, the more actively others may follow him. This scenario helps rationalize why herding is asymmetric between up and down markets.

This article employs the quarterly nominal housing market data for 38 OECD member countries from the first quarter of 1970 to the fourth quarter of 2022. By using the estimated US PTR regimes, the analysis presents novel evidence that global herding across housing markets is highly conditional on the interplays between US PTR regimes and up/down markets. The empirical results are consistent with the proposition that herding behavior across housing markets is driven by confirmation bias boosted by coincidence between average price changes and the expectation on the US housing market. Even after the effects of fundamental anchors are purged away, evidence is substantial, strongly suggesting that psychological herding is present across housing markets. Upside herding occurs when there is a match between overall price rise and the lower US PTR regime (i.e., when average price rise coincides with the regime where US house price is too low relative to rent). Downside herding arises when there is a coincidence between overall price drop and the upper US PTR regime (i.e., when average price drop occurs in the regime where US house price is too high relative to rent). This study also finds that spurious fundamental herding emerges when there is a mismatch between overall price changes and the US PTR regimes.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows. The second section explains the test models and presents the global herding hypotheses under confirmation. The third section presents the theoretical implication of price-to-rent ratio and the Hansen-Seo (2002) approach to identifying the expected PTR regimes in the housing markets. The fourth section explains the sample data and the results of preliminary analyses based on the estimated US PTR regimes. The fifth section discusses empirical results. The article concludes in the sixth section.

Models and hypotheses

Approach to detecting the presence of herding behavior

The most popular approach to detecting herd behaviors is the models by Christie and Huang (1995) (CH in shorthand) and Chang et al. (2000) (CCK in shorthand). The essential feature underlying the models is that average dispersion from the market diminishes and reaches the lowest level in extreme markets, as individual returns herd around the market. Thus, the models presume that the target and the driver of herding is the market average return and the market volatility, respectively. In order to detect herding under market stress, regression analyses are applied to CSAD (cross-sectional absolute deviation) or CSSD (cross-sectional standard deviation) in returns. As a threshold of extreme markets, Christie and Huang (1995) suggest the tails of 1%, 5%, and 10% over the probability distribution of market returns. Such choice of criteria is simple but deemed to be arbitrary.

To avoid the arbitrary definition of extreme markets, Chang et al. (2000) suggest an alternative quadratic model such that herding is detected in the dynamic relationship between CSAD and market returns. From the viewpoint of asset pricing theory, the CCK model has a theoretical virtue in the sense that herding is assumed to be driven by \({r}_{m}^{2}\) as an approximate proxy of market volatility. According to the CCK model, CSAD should be a quadratic function of market returns, a parabola that is open downward. Thus, herding is absent when CSAD reaches the peak at the market return, solving its first order condition of the function, where average dispersion across returns attains a maximum. In contrast, the degree of herding increases as return dispersions (CSAD) decrease with a decrease in market return in the lower range at the vertex of a parabola or return dispersions decrease with an increase in market return in the upper range at the vertex of a parabola. Herding is existent at extremes in which CSAD becomes zero. Thus, the presence of herding in the CCK model depends on whether the coefficient of the second-order term (approximate volatility) is negative in the polynomial regression. This implies that in the CCK model squared market return (approximate volatility) is regarded to be the essential driver of herding.

Decomposition of CSAD into domestic and global components

Under the assumption that investors herd around the global market, a simple application of the triangular inequality helps decompose CSAD into two components. To show the decomposition, the time indicator t is suppressed in subscripts for tractability. There are \({p}_{j}\) domestic sectoral markets in country j, q country market indices, and 1 global market index in the world. Denote \({r}_{i}^{j}\), \({r}_{d}^{j}\), \({r}_{g}\), \({p}_{j}\), and q as return on sector i in country j, domestic market return in country j, global market return, the number of housing sectors in country j, and the number of countries, respectively. The cross-sectional absolute deviation of sectoral housing returns in the domestic market, pivotal to global market return g, is defined as follows.

Using the triangular inequality, the upper bound of the CSAD measure is decomposed into two constituents: domestic and global one. Thus, for country j, one obtains the right-hand side expression with two separate measures of deviation.

Summing over all countries, the inequality (2) is generalized to the equation with non-negative δ:

The upper bound of the RHS is written as: \(CSAD=CSA{D}_{d}+CSA{D}_{g}={\sum }_{j=1}^{q}CSA{D}_{d}^{j}+CSA{D}_{g}\). The notations are defined as below.

\(CSA{D}_{d}^{j}={p}_{j}^{-1}{\sum }_{i=1}^{{p}_{j}}|{r}_{i}^{j}-{r}_{d}^{j}|\) represents the domestic dispersion measure for country j.

\(CSA{D}_{d}={({\sum }_{j=1}^{q}{p}_{j}q)}^{-1}{\sum }_{j=1}^{q}{\sum }_{i=1}^{{p}_{j}}|{r}_{i}^{j}-{r}_{d}^{j}|\) represents the aggregate domestic dispersion measure for all countries. \(CSA{D}_{g}={q}^{-1}{\sum }_{j=1}^{q}|{r}_{d}^{j}-{r}_{g}|\) represents the global dispersion measure.

The upper bound of \(CSA{D}^{j}\) for country j at time t is written as \(CSA{D}_{t}^{j}=CSA{D}_{dt}^{j}+A{D}_{gt}^{j}\), where \(A{D}_{gt}^{j}=|{r}_{dt}^{j}-{r}_{gt}|\) represents the absolute deviation of country j’s market return from the global market return. The majority of empirical papers has analyzed herding behavior in housing markets based on CSADd in a particular country (Zhou and Anderson, 2013; Ngene et al. 2017; Pollock et al. 2024). Therefore, instead of CSADd, the present study pays close attention to CSADg for the analysis of global herding behavior across countries.Footnote 5

Empirical models

The test model adopted by this study is the modified version of CCK and Chiang and Zeng (2010) (CZ in shorthand) (2010). Based on the framework of CZ, who consider the impact of the US market, the empirical model in this study contains two drivers of herding: the average market volatility \({r}_{g}^{2}\) and the US market volatility \({r}_{US}^{2}\). As usual, CSAD denotes the cross-sectional average deviation between individual market returns and average market returns. CSADPTR and CSADPTI represent the cross-sectional average distances in PTR and PTI between individual countries and average markets, respectively.

The present study examines state-dependent herding behavior by defining states according to the rationale as follows. First, herding behavior is classified into downside and upside herding (Bikhchandani et al. 1998). Second, herding is differentiated between down and up markets (Zhou and Anderson, 2013; Philippas et al. 2013; Babalos et al. 2015). Third, the US market is the leader (pied piper) in global housing markets (Claessens et al. 2011; Yunus, 2015). Fourth, the US housing market status is partitioned into the lower PTR regime and the upper PTR regime. In accordance with the rationales, conditioning variables are operationally defined as follows. A dummy variable Dd takes 1 if average house price changes in a global market are less than or equal to zero, and Du takes 1 elsewhere. An indicator A1 takes 1 if the US PTR is less than or equal to a threshold φ, and A2 is set to 1, otherwise. A threshold φ can be interpreted as implicit transaction cost. The threshold is conceivable as a reference point before and after which investors shift the long-run expectation about the US market. The dummy A1 denotes the lower US PTR regime in which the US house price is too low relative to rent, implying it is undervalued. The dummy A2 indicates the upper US PTR regime in which the US house price is too high relative to rent, implying it is overvalued. Put together, the set of states is expressed as S = {Dd, Du, A1, A2}. In the similar spirit with CCK and CZ, the baseline models are specified as follows.

In the models, the Greek letters and e represent the parameters and the error terms in the regression, respectively. The matched interactions (confirmed matching) are an underlying cause of confirmation bias. Thus, in order to know if confirmation bias is displayed by investors, one should check the significance of interactions such as \({D}_{d}{A}_{2}\), \({D}_{u}{A}_{1}\), \({D}_{d}{A}_{1}\) and \({D}_{u}{A}_{2}\). The interaction \({D}_{d}{A}_{2}\) (\({D}_{u}{A}_{1}\)) represents the state at which investors expect the US market to fall (rise) and average markets fall (rise). The interactions point to a match between expectations on US market and overall price change. By contrast, the interaction \({D}_{d}{A}_{1}\) (\({D}_{u}{A}_{2}\)) indicates the state where investors expect the US market to rise (drop) but average markets fall (rise). This interaction indicates a mismatch between expectation on the US price and overall price change. Note that the mismatch (unconfirmed matching) does not entail confirmation bias. Therefore, in order to know if herding is driven by confirmation bias or not, it is necessary to augment the model with interactions between price changes and US PTR regimes. \({D}_{d}{A}_{2}\) and \({D}_{u}{A}_{1}\) is the matched interaction between overall price change and expectation on the US market. \({D}_{d}{A}_{1}\) and \({D}_{u}{A}_{2}\) are the mismatch of signals between overall price change and expectation on the US market. By allowing interactions, the main model is formulated as follows.

In line with CZ, the above specification implicitly assumes that global herding is driven by (1) average market volatility and (2) the US market volatility. If herding is driven by average market volatility, negative signs are expected in parameters γg, γgd, γgu, γgd1, γgd2, γgu1, and γgu2. If the driver of herding is the US market volatility, the negative signs are predicted in the parameters γusd, γusu, γus1, γus2, γus,d1, γus,d2, γus,u1, and γus,u2.

By using \(CSA{D}_{PTR}={q}^{-1}{\sum }_{j=1}^{q}|PT{R}_{d}^{j}-PT{R}_{g}|\) and \(CSA{D}_{PTI}={q}^{-1}{\sum }_{j=1}^{q}|PT{I}_{d}^{j}-PT{I}_{g}|\), it is also possible to test the presence of spurious herding in fundamentals. Note that PTR and PTI is a valuation indicators that reflect fundamentals. In order to test if country returns herd directly around the US market (i.e., the US is the target of herding), \(UCSA{D}_{g}={q}^{-1}{\sum }_{j=1}^{q}|{r}_{d}^{j}-{r}_{us}|\) is used as a dependent variable. Likewise, the dispersion measures \(UCSA{D}_{PTR}={q}^{-1}{\sum }_{j=1}^{q}|PT{R}_{d}^{j}-PT{R}_{us}|\) and \(UCSA{D}_{PTI}={q}^{-1}{\sum }_{j=1}^{q}|PT{I}_{d}^{j}-PT{I}_{US}|\) are used to test whether individual countries display spurious herding behavior in fundamentals around the US market.

Conceptual framework and global herding hypotheses under confirmation bias

The idea that housing markets exhibit global herding subject to particular biases accords with the notion of ‘contagion of ideas’, ‘contagion of market psychology’, ‘social contagion of thinking’ and ‘information cascade by social learning’ (Shiller, 2008; Bayer et al. 2021; Bikhchandani et al. 2024).Footnote 6 Devenow and Welch (1996) maintain that psychological herding arises when investors feel more safe and secure by following crowds. This claim opens the possibility that herding is influenced by other mental bias, such as confirmation bias. Einhorn and Hogarth (1978) urge that people are prone to search for confirming evidence, not disconfirming evidence. When people encounter confirming evidence, they might feel more safe and more secure by following crowd. As explained in the previous section, the bias trio of confirmation-overconfidence-herding is linked sequentially. Using self-attribution bias, Daniel et al. (1998) show that investors become overconfident when private information is confirmed by arrival of public information. In the present study, I do not make distinction between public and private information. Instead, I argue that investors are overconfident when average price changes are confirmed by the pricing status of a market leader.Footnote 7

Let me explain in detail how the process of herding works in the housing market under the following assumptions: (1) investors recognize the US housing market as the leader; (2) they use an error correction filter \((w)\) to assess the status of the US market;Footnote 8 (3) they hold the belief that US house price changes are transmitted to their own markets. Herding takes place as follows. Shocks disturb the market. Overall prices change abruptly. Prior to acting, investors use an error correction filter to assess whether the US market is over-priced or under-priced. If overall price changes are confirmed (matched) by US market status, they are overconfident and overreact on the match of signals. Ultimately, they display herding behavior toward the US market by mimicking the pattern of buy or sell by US investors. On the contrary, if overall price changes are unconfirmed by the US market status, investors are underconfident and underreact on the mismatch of signals. In the case of mismatch, they are likely to act in a passive way, only to the extent that fundamentals justify the convergence among markets, thereby displaying spurious herding behavior. Therefore, only when overall price changes are in conformity with US market condition, investors are susceptible to confirmation bias and they come to display herding behavior.Footnote 9

Herding behavior may be downside or upside. Suppose that average housing markets go down when the current price of the leader market is expected to be too high (overvalued). By such coincidence, investors believe that overall price down is confirmed by the leader market. Then, they are afraid that the US market’s decline is spilled over to their own markets. Subject to confirmation bias, they are highly confident on the matched signals. They overreact and follow the leader’s behavior on the sell-side. This results in downside herding. On the contrary, suppose average markets rise when the current price of a leader market is expected to be too low (undervalued). Investors are overconfident on the match of signals when they believe overall price rise is confirmed by the undervalued US market. Susceptible to confirmation bias, they would readily follow the trading behaviors of the leader market on the buy-side. This results in upside herding. In order to explain the causal chains in a clearer fashion, this study uses the notation \(\Delta p\) for average price change, \({w}_{us}\) for error correction in the US market, and \(\varphi\) for a threshold in the US market. The US market is in the overvalued regime where \({w}_{us} \,>\, \varphi\), while it is in the undervalued regime where \({w}_{us} \,<\, \varphi\). Downside herding takes the process: \((\Delta p \,<\, 0,\,{w}_{us} \,>\, \varphi )\) → a match of signals → confirmation bias → overconfidence on bust → overreaction to down-market → information cascades by social learning → downside herding across countries. By contrast, upside herding takes the process: \((\Delta p \,>\, 0,\,{w}_{us} \,<\, \varphi )\) → a match of signals → confirmation bias → overconfidence on boom → overreaction to up-market → information cascades by social learning → upside herding across countries. On the contrary, note that the combinations \((\Delta p \,<\, 0,\,{w}_{us} \,<\, \varphi )\) and \((\Delta p \,>\, 0,\,{w}_{us} \,>\, \varphi )\) do not entail herding behavior due to a mismatch of signals. Specifically, the process of mismatch proceeds as follows: \((\Delta p \,<\, 0,\,{w}_{us} \,<\, \varphi )\) and \((\Delta p \,>\, 0,\,{w}_{us} \,>\, \varphi )\) → a mismatch of signals → no confirmation bias → under-confidence → underreaction → no information cascades by social learning → no herding across countries.

Let us formulate the hypotheses. The subscripts ‘a’, ‘b’, and ‘s’ are used to indicate downside herding, upside herding, and spurious herding, respectively. Subscripts ‘1’ and ‘2’ are used to denote herding driven by average market and the US market volatility, respectively. Superscript ‘*’ is used to indicate that herding behavior occurs toward the US market. In Eq. (7), I specify the drivers and the targets of herding and distinguish between upside herding (a) and downside herding (b). Then, the major hypotheses are established as follows.

H1 (target: average market, driver: average market volatility): (a) Downside global herding occurs around the average market, driven by the average market volatility, when US market price is expected to be too high (\({\gamma }_{gd2} \,<\, 0\)). (b) Upside global herding occurs around the average market, driven by the average market volatility, when US market price is expected to be too low (\({\gamma }_{gu1} \,<\, 0\)).

H2 (target: average market, driver: US market volatility): (a) Downside global herding occurs around the average market, driven by the US market volatility, when US market price is expected to be too high (\({\gamma }_{us,d2} \,<\, 0\)). (b) Upside global herding occurs around the average market, driven by the US market volatility, when US market price is expected to be too low (\({\gamma }_{us,u1} \,<\, 0\)).

H1* (target: US market, driver: average market volatility): (a) Downside global herding occurs around the US market, driven by the average market volatility, when US market price is expected to be too high (\({\gamma }_{gd2} \,<\, 0\)). (b) Upside global herding occurs around the US market, driven by the average market volatility, when US market price is expected to be too low (\({\gamma }_{gu1} \,<\, 0\)).

H2* (target: US market, driver: US market volatility): (a) Downside global herding occurs around the US market, driven by the US market volatility, when US market price is expected to be too high (\({\gamma }_{us,d2} \,<\, 0\)). (b) Upside global herding occurs around the US market, driven by the US market volatility, when US market price is expected to be too low (\({\gamma }_{us,u1} \,<\, 0\)).

The case of mismatch may occur when price changes are not confirmed by current US price regimes. Two cases of mismatch are possible: (1) the average market is down while the US market is expected to be undervalued; (2) the average market is up when the US market is expected to be overvalued. In both cases, confirmation bias is not combined with herding due to a disparity between expectation (belief) and reality. Due to the lack of confirmation by the US market status, investors are less susceptible to confirmation bias, are less confident (or underconfident), and display less herding behavior. Then, instead of following others, investors are likely to act rather rationally by keeping pace with the speed of convergence in fundamentals. In case that fundamental anchors diverge largely between markets, investors behave passively in such a way that anchors are aligned with those in US or average market. Thus, convergence in fundamental anchors is likely to occur within the limits of investors’ rationality, linkages in fundamentals, and inter-market barriers. The adjustment in fundamentals can entail seemingly global herding in fundamental anchors. This is spurious herding driven by common fundamentals (Bikhchandani and Sharma, 2000). Using the subscript s for spurious herding, the spurious herding hypothesis is set up as follows.

H3s (Convergence in valuation indicators toward the market average): if there is a mismatch between average house price changes and US price regimes, PTR and PTI adjust to be aligned with the market averages of the anchors, resulting in spurious global herding toward average markets. H*3s (Convergence in valuation indicators toward the US market): if there is a mismatch between average price changes and US price regimes, PTR and PTI adjust to be aligned with those of the US market, resulting in spurious global herding toward the US market.

Identifying expectation regimes

PTR as the long-run expectation of future growth of rents

In this section, I delineate the theoretical notion of PTR as an indicator of market expectation on future fundamentals. The rational expectations present value model asserts that house prices are the same as expected future rents discounted to the present.Footnote 10 Then, the following relationship is expected to hold between house prices (Pt), rent (Rt), assuming constant discount rate (ρ).

where E denotes the expectation operator. Consider a base-case where owner investors earn an infinite stream of constant rent Rt. Since \({\rho }^{-1}{R}_{t}\) is the present value of the base-case, subtracting \({\rho }^{-1}{R}_{t}\) from both sides of (8) obtains: \({P}_{t}-{\rho }^{-1}{R}_{t}={E}_{t}[{\sum }_{i=1}^{\infty }{(1+\rho )}^{-i}{R}_{t+i}]-{\sum }_{i=1}^{\infty }{(1+\rho )}^{-i}{R}_{t}\). Rearranging the terms in the right-hand side, one ends up with the following.

where \(\Delta {R}_{t+i}={R}_{t+i}-{R}_{t}\) for i = 1 to infinity.

This equation clearly states that the difference between house prices and rent reflects the rational forecasts of the future growths of rent as the underlying fundamental. If theory is valid, there should exist a long-run equilibrium relationship between house prices and rent. The right-hand side is stationary if house prices and rent are stationary in differences. Then, the left-hand side should also be stationary. Accordingly, Eq. (9) implies that house prices and rent are cointegrated in the sense of Engle and Granger (1987).

Hansen-Seo approach to the division of regimes

The prior section shows that PTR (or log PTR) is an indicator that contains the market’s expectation on the future growth of rents in the housing markets. Thus, the cointegration relationship is expected to exist between log house price and log rent. A caveat is that the relationship is nonlinear due to the presence of transaction cost. Unless gains exceed the costs of transaction, investors are not enticed to exploit the opportunity. Adjustments may occur differently according to whether gains exceed transaction costs (a threshold) or not. Non-linear adjustment occurs around a threshold (representing transaction cost) reflected in the PTR. In order to estimate the threshold in the PTR, I apply the Hansen and Seo approach (2002) to a 2-regime threshold vector error correction model (TVECM). Consider a vector \({y}_{t}=({p}_{t},{r}_{t}){\prime}\) where pt = log (Pt), rt = log (Rt), respectively. Let yt be a 2-dimensional I(1) series cointegrated with a vector β = (1, −b)′ and \({w}_{t}(\beta )=\beta {\prime} {y}_{t}={p}_{t}-b{r}_{t}\). The model without a threshold is described as the standard VECM of order k + 1 as follows.

where ϕ is a 2 × 1 vector of adjustment coefficients; \({{\rm A}}_{i}\) is the matrix of short-run coefficients at lag i; α is a (2 × 1) vector of intercepts; \({\varepsilon }_{t}\) is a 2 × 1 vector of i.i.d. errors.

Under alternative hypothesis, Hansen and Seo (2002) consider a TVECM with two regimes divided around a threshold φ.

where φ denotes the threshold parameter; \({\phi }_{j}\) is a 2 × 1 vector of adjustment coefficients in regime j with \({\phi }_{j}=({\phi }_{\Delta p,j},\,{\phi }_{\Delta r,j})^{\prime}\), j = 1, 2; \({{\rm A}}_{ji}\) is the (2 × 2) regime specific matrix of short-run coefficients at lag i in regime j with \({{\rm A}}_{ji}=({\alpha }_{\Delta p,j,i},\,{\alpha }_{\Delta r,j,i})^{\prime}\); \({\varepsilon }_{jt}\) is a 2 × 1 vector of i.i.d. errors in regime j with \({\varepsilon }_{jt}=({\varepsilon }_{\Delta p,j,t},\,{\varepsilon }_{\Delta r,j,t})^{\prime}\); \({\alpha }_{j}\) refers to a (2 × 1) vector of intercepts in regime j with \({\alpha }_{j}=({\alpha }_{\Delta p,j},\,{\alpha }_{\Delta r,j})^{\prime}\).

SupLM is the Lagrange multiplier statistic to test the linear VECM against the TVECM with two regimes. The test looks for the optimal value of LM statistic that is maximized over the permissible range of φ.

where φL and φU represent the lower and the upper bound of φ in the search region such that φL is the π0 percentile of wt-1 and φU is the 1-π0 percentile of error correction wt-1. Since the SupLM statistic has a non-standard asymptotic distribution due to the presence of nuisance parameters, the bootstrap technique is used to calculate p-values for the statistic.

Data and preliminary analysis

Data description

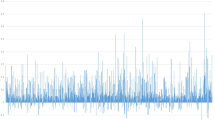

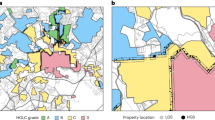

In order to secure the sample from a homogenous group which are economically tied, this study employs the quarterly nominal housing data for OECD countries. The data covering from the beginning of 1970 to the end of 2022 is retrieved from the database at the OECD site. The sample includes housing rent prices indices, nominal house prices indices, and ratios of price to rent and price to income. The series includes the OECD average index and 38 member-country indices. Price to income ratio is the nominal house price index divided by the nominal disposable income per head and can be considered as a measure of affordability. Price to rent ratio is the nominal house price index divided by the housing rent price index and can be considered as a measure of the profitability of house ownership. Price to income and price to rent ratios are all available with base year 2015. All the indices are seasonally adjusted. Seasonal adjustments are made with the X11 algorithm if unadjusted in original sources. All the analyses are conducted with the natural-log transformed series. The US regimes are estimated using overall house price index and overall rent index. Returns are estimated in percent with differenced log series multiplied by 100. All the dispersion measures are computed on available basis. Accordingly, global dispersion measures in returns at time t are computed in percent with \(CSA{D}_{gt}={q}_{t}^{-1}{\sum }_{j=1}^{{q}_{t}}|{r}_{dt}^{j}-{r}_{gt}|\) and \(UCSA{D}_{gt}={q}_{t}^{-1}{\sum }_{j=1}^{{q}_{t}}|{r}_{dt}^{j}-{r}_{ust}|\). In a similar way, dispersion measures in PTR and PTI are also measured, but not in percent.

Identification of US PTR regimes and sample statistics

Two-regime threshold VECM (TVECM) is estimated according to the procedure of Hansen and Seo (2002). Estimation results are reported in Table 1. For consistency with the notion of PTR, b is restricted to be 1.0 in cointegrating regression. At conventional significance level, SupLM statistic 28.02 can reject the traditional VECMs significantly in favor of TVECM, assuring that the system of house price and rent displays non-linear dynamics. The US PTR is divided in two regimes around the threshold of 0.005936. Approximately 57.8% and 42.2% of observations fall into the lower and the upper regime, respectively. The US housing market mean-reverts only in the upper regime of PTR, where p-r > 0.005936, that is, the difference between price and rent is above the threshold. In contrast, subsequent adjustment seldom occurs in the lower PTR regime (that is, when the gap between p and r is less than the threshold estimate). This evidence is approximately consistent with the view that the nonlinear adjustment may take place due to the presence of transaction costs.

Table 2 reports descriptive statistics including the number of observations (N), mean, maximum, and minimum in the lower and upper US PTR regimes. Mean returns are higher in the upper US PTR regime than the lower US PTR regime. The same is true in squared return which is an approximate volatility. CSAD in return is also higher in the upper US PTR regime. In contrast, CSAD in PTR and PTI display an inverse distributional pattern against returns. This opposite pattern may suggest that PTR and PTI are adjusted in a fashion different from adjustment in return, which may be the partial symptom of the existence of spurious herding. Lastly, it appears that the patterns for UCSADs are almost the same as for CSADs.

Empirical results

Evidence on global herding from the baseline models

Table 3 exhibits the estimation results of the baseline models ruling out interaction between US regimes and average price changes. Specification (1) is on the same foot with the original CCK model. According to the CZ model, specification (2) is augmented with the approximate volatility of US market and the down/up dummies for average market returns. Specification (3) is the modified version of (2), augmented with the dummies of US price regimes instead of down- and up-market dummies. The heteroscedastic-autocorrelation-consistent (HAC) standard errors are reported to adjust autocorrelation and heteroscedasticity in residuals. Herding behavior is present if the coefficient of the second-order term is significantly negative. Evidence in favor of herding is not detected in specification (1). The rejection may arise due to omitted variable problems in the regression. This conjecture is somehow ascertained in the extended model including US variable, market condition dummy and interaction terms. Note that herding turns out to be significant in (2) and (3). As expected, the estimation of (2) finds that global herding is driven by both average market and the US volatility, except when the overall market is at up-state. The estimation results of (3) show that global herding is driven by the US market volatility. US-driven global herding is stronger when investors are in the lower US PTR regime.

Chi-square tests are conducted to check the collective significance of volatility variables as a driver of herding. The tests show that average market volatility and US market volatility are significant in specifications (2) and (3). F tests are conducted to check if herding is asymmetric. The tests also demonstrate that herding is asymmetric not only between up and down market, but also between the lower and the upper US PTR regimes. Even in the global setting, it appears that herding behavior is more conspicuous in the down-market. This evidence corroborates with the finding by Zhou and Anderson (2013) on US REITs and by Babalos et al. (2015) on US direct house markets.Footnote 11

Global herding explained and unexplained by fundamental anchors

In this section I discuss the estimation results from the main models with interactions between up/down markets and the US PTR regimes. In order to check if confirmation bias drives global herding, a close attention should be paid to the interplays between the US PTR regimes and average price changes. Table 4 reports the estimation results together with robustness tests. In relation to global herding driven by confirmation bias, the major hypotheses are expressed as follows. H1a:\({\gamma }_{gd2} \,<\, 0\). H1b:\({\gamma }_{gu1} \,<\, 0\). H2a: \({\gamma }_{us,d2} \,<\, 0\). H2b: \({\gamma }_{us,u1} \,<\, 0\). H3s:\({\gamma }_{gd1} \,<\, 0\), \({\gamma }_{gu2} \,<\, 0\), \({\gamma }_{us,d1} \,<\, 0\), \({\gamma }_{us,u2} \,<\, 0\)). In Table 4, variables and parameters of an interest are in boldface to indicate that they are directly associated with the main hypotheses of global herding. The hypotheses other than H3s are for the presence of psychological herding. The hypothesis H3s is for the presence of spurious herding. Let’s take a look at specification (1) where CSAD of return is the dependent variable. The hypotheses accepted at conventional significance levels are three-fold: H1a:\({\gamma }_{gd2} \,<\, 0\), H2a:\({\gamma }_{us,d2} \,<\, 0\), and H2b:\({\gamma }_{us,u1} \,<\, 0\). This evidence strongly supports that global herding is driven by confirmation when there is coincidence between average price changes and the US PTR regimes. Downside herding marked with subscript “a” is significant in two cases (H1a and H2a). Upside herding marked with subscript ‘b’ is significant only in H2b. Thus, upside herding is driven only by the US market volatility. This evidence hints that global herding in boom is mostly driven by the US market volatility. The rejection of the hypothesis H1b indicates that there is no upside herding driven by average market volatility. However, the test shows that upside herding is driven by the US market volatility (H2b). The significant negativity of \({\gamma }_{gd1}\) is contradictory to expectation. The negative coefficient is an unexpected result since it corresponds to the case of mismatch between the US PTR regimes and overall price changes. Such contradictory result might arise due to spurious herding in fundamental factors. Thus, it is too hasty to discount the hypothesis that herding requires the match between US regimes and price changes. For precise inference, it is necessary to filter out the part of spurious herding arising from fundamental factors.

By using CSADPTR and CSADPTI as a dependent variable, it is possible to assess the degree of spurious herding. The estimation results are reported in (2) and (3) of Table 4. Overall evidence does not differ between PTR and PTI. Coefficients \({\gamma }_{gd1}\) and \({\gamma }_{us,u2}\) are all significantly negative in PTR and PTI anchors, suggesting that global housing markets display spurious herding behavior. As expected, the spurious herding in fundamental anchors occurs at a mismatch between US PTR regimes and average price changes. It appears that herding in fundamental anchors occurs at a mismatch of signals when average price drop coincides with the lower US PTR regime and when average price rise encounters the upper US PTR regime. Overall, the results are highly consistent with the spurious herding hypothesis H3s:\({\gamma }_{gd1} \,<\, 0\), \({\gamma }_{us,d1} \,<\, 0\), \({\gamma }_{us,u2} \,<\, 0\), indicating that fundamental anchors converge into average when the US market signal is unmatched with average price changes. At the mismatch of signals, investors tend to behave rather rationally, since then they are not subject to confirmation bias.

In order to clean out the portion of spurious herding, two steps are taken. First, CSAD of returns is regressed on CSADPTR and CSADPTI, and then the series of residuals are generated as the net portion of CSAD in return unexplained by PTR and PTI.

Second, the models are re-estimated with the net CSAD. The estimation results are presented in (4) of Table 4. It is worth noting that the spurious herding behavior disappears when the effects of PTR and PTI anchors are controlled. Using the net CSAD as a dependent variable, the hypotheses H1a, H2a and H2b are accepted. The test results are highly consistent with the main argument that herding behavior is displayed at a match between average price changes and US price regimes. Downside herding is significantly driven by both the average market volatility and the US market volatility when there is a match between average price change and US price signal. That is, if average price decline is confirmed by the overvalued US regime, investors are subject to confirmation bias, they are overconfident on the bust (price drop), and they act on the sell-side following US investors. The test results support the logical chain of downside herding.

On the other hand, the upside herding is driven by the US market volatility only (H2b). This upside herding occurs if the undervalued US regime coincides with average price rise. At the coincidence, investors, subject to confirmation bias, are overconfident on the signal and act on the buy-side. The ultimate result is the upside herding. This upside herding, driven by the US market volatility only, indicates that investors herd on the buy-side toward the US market more actively when they are in the lower US PTR regime. By contrast, the rejection of H1b indicates that there is no upside herding driven by the average market volatility. The upside herding is driven only by the US market volatility. In addition, I find weakly negative coefficient of herding \({\gamma }_{us,u2}\), although average price rise encounters the upper US PTR regime (i.e., a mismatch of signals). I conjecture that such weakly contradictory result suggests that PTR and PTI may be a noisy proxy of fundamental factors.

Chi-square tests are conducted to check the collective significance of herding drivers in the models. The test results show that average market and the US volatility are all significant as a driver of global herding. In order to assess the impact of great shocks, the robustness tests are conducted for the significance of the Covid-19 period from 2020.1Q to 2022.4Q (66 observations) and the GFC crisis period from 2017.3Q to 2018:4Q (5 observations).Footnote 12 The predictive Chow tests are employed to check the stability of the models against two crises. The tests are useful when the hold-back sample is small. The test employs the F test statistic for the significance of the full sample model against the reduced sample model.Footnote 13 The test shows that the main results are not significantly influenced by the periods of two crises. This evidence corroborates the earlier finding that herding behavior in housing markets was not influenced by the global financial crisis (Philippas et al. 2013; Pollock et al. 2024).

Does global herding occur directly around the US?

In this section, I evaluate the possibility that housing markets herd directly around the US market. For the purpose, UCSAD is employed as a dependent variable in the regression.

Table 5 shows the estimation results of herding behavior around the US market. The results are displayed in the table according to dependent variables such as UCSAD in return, UCSADPTR, UCSADPTI, and net UCSAD. Panel A of Table 5 displays the estimation results from the whole sample, without exclusion of the global financial crisis (GFC) and the Covid-19 periods. The final column in Panel A of Table 5 shows that the hypotheses H*1a (\({\gamma }_{gd2} \,<\, 0\)) and H*2b (\({\gamma }_{us,u1} \,<\, 0\)) are significant, respectively. The test result tells that psychological herding behavior is driven by the US market volatility when average price changes are confirmed by US market status (i.e., when there is at a match). Downside herding behavior is driven by average market volatility when average price drop occurs in the upper US PTR regime. In contrast, upside herding is driven by the US market volatility when average price rise takes place in the lower US PTR regime. All the pieces of evidence are well aligned with the hypothesis that confirmation bias drives herding. Empirical results, almost consistent between Tables 4 and 5, strengthen the argument that the US housing market is the global leader.

The Chow tests are conducted to see whether the crisis periods affect the inferences. The tests show that the results based on UCSAD in return and net UCSAD are all influenced by the Covid-19 period, but not by the GFC period. Thus, the models are re-estimated after discarding the observations corresponding to the Covid-19 crisis. The estimation results in Panel B of Table 5 demonstrate that the hypotheses H2a*(\({\gamma }_{us,d2} \,<\, 0\)) and H2b*(\({\gamma }_{us,u1} \,<\, 0\)) are not rejected even when the crisis period is dropped out of the sample, assuring the robustness of results.

In a nutshell, empirical analyses draw out four points. First, downside herding occurs at a match when average price drop is confirmed by the upper US PTR regime. Second, upside herding occurs at a match when average price rise is confirmed by the lower US PTR regime. Third, spurious herding (i.e., herding in PTR and PTI) occurs at a mismatch when average price drop (rise) is not confirmed by the upper (lower) US PTR regime. Fourth, confirmation bias among investors plays a significant role in driving global herding in the housing markets.Footnote 14

Conclusion

This article investigates the global herding behavior in the housing markets. Using the OECD quarterly data from 1970 to 2022, this study finds that housing markets display the global herding behavior contingent on the contemporaneous interactions between the US price-to-rent regimes and average price changes. Evidence is highly consistent with the proposed view that global herding is displayed when investors use a pseudo signal flying from the US market for confirmation. The empirical results also suggest that herding behavior across housing markets is driven by confirmation bias, boosted by coincidence between average price changes and expectation on the US housing market. Even after the effects of fundamental anchors are purged away, evidence is substantial, suggesting that global herding across housing markets is mainly attributed to psychological reasons.

This study finds robust evidence of both downside and upside herding across housing markets. Downside herding implies that it occurs when average price drop is matched with overvalued US market. Herding arises through a sequential chain of confirmation-overconfidence-herding. As investors predict that the US market is overvalued, they feel afraid that the bust of the US market spreads over the world. If the expectation of US price-down overlaps with overall price-down in the global housing market, investors are more susceptible to confirmation bias. Once they feel average price changes were already confirmed by the US market status, they are overconfident on the coincident signal and overreact. Being overconfident in the negative signal, investors trade on the sell-side in such a way to mimic the behaviors of US investors. The consequence is global downside herding. In addition, I also find the evidence for upside herding when the undervalued US regime coincides with average price rise. Such coincidence also exposes investors to confirmation bias, since they think average price rise is already confirmed (endorsed) by the US market prospect. They become overconfident on the positive signal of overall price rise and overreact on the buy-side. This process leads them to display upside herding toward the US market. Conclusively, confirmation bias among investors plays a significant role in driving global herding in the housing markets.

This article draws four implications from empirical analyses. First, the presence of global herding may attenuate the effect of the interest rate policy aiming to tame the housing market. The interest rate policy has been known to be an effective tool to tame the housing market (Martin et al. 2022). In addition, the adjustment of DTI (debt-to-income) and LTV (loan-to-value) is often adopted to stabilize the housing markets. However, the evidence in this article suggests that under the existence of global herding the effectiveness of such policies in the housing markets may be limited since the origin of herding is beyond the national boundary and it is psychologically driven.

Second, an early warning system as a way of debiasing may be implemented in order to provide early signals (Park and Ryu, 2021; Compen et al. 2022). In order to devise such a debiasing system, the essential task is to measure the degree of herding and set the tolerable limit at which intervention starts. The present study assesses the degree of global herding with the negative coefficients \({\gamma }_{g,d2}\) and \({\gamma }_{us,d2}\) for downside herding, together with \({\gamma }_{g,u1}\) and \({\gamma }_{us,u1}\) for upside herding. By exploiting the coefficients, it is possible to set the limit of herding required for intervention.Footnote 15

Third, nudges are often recommended to debias behavioral errors (Thaler and Sunstein, 2008). Nudge implies a form of weak intervention for helping people to avoid psychological pitfalls and make better decisions (Shefrin, 2018). The purposeful design of decision frames (called choice architect) may facilitate effective decision-making. The understanding of confirmation bias underlying the global herding across housing markets can help choice architects devise ways to provide feedback to decision-makers such that they themselves are cognizant of their biases.

Fourth, social media can be employed to debias dysfunctional effects by conveying the right signal to investors (Frijns and Huynh, 2018). A false belief is formed from an unproven vague hypothesis with which investors have taken for granted a long time. Social networks, from mouth-to-mouth networks to online social media, play an important role in the spread of information (Bikhchandani et al. 2024). In reality, social contagion is substantial among nearby households (Bayer et al. (2021). A quick propagation of false belief would hurt the function of markets. In order to mitigate the negative effects of human biases, the parties of interest should convey the right signal and the proven information to the public through effective media such as social networks and others.

The limitation and future direction of this study are as follows. First, the empirical findings may be explained alternatively using the club convergence theory. The theory claims that countries in the same club are likely to converge in income level, growth rate, cultural norms, and political systems. The sample for this study is drawn from OECD club member countries who seek to coordinate economic policies for common economic goals with each other (Apergis et al. 2012). From the viewpoint of the club convergence theory, global herding might be a natural result. Thus, although housing market fundamentals are controlled away, it is difficult to assure that global herding is driven purely by psychological reason. One way of evading this problem is to secure the sample as large as possible such that it includes non-OECD countries including China.Footnote 16 Second, PTR and PTI might be an imperfect proxy for fundamentals in housing markets if the indicators do not fully reflect housing market fundamentals or they are also influenced by psychological biases. Thus, by looking for alternatives, it may be necessary to complement the indicators as the proxy for housing market fundamentals. In particular, the present study presumes that the US PTR regimes play a crucial role in capturing investors’ expectation about a leader market. However, there may exist other significant regimes including monetary regimes (Tsai, 2013) and PTI regimes. Thus, it is also deemed worthwhile to analyze the global herding behavior based on the alternative regimes. The extension into the directions is left for future research.

Data availability

The quarterly data for the period from 1970.1Q to 2022.4Q are publicly available at the URL https://data.oecd.org/. OECD (2022), housing prices (indicator). https://doi.org/10.1787/63008438-en. The data include house price index, rent index, price-to-rent index, and price-to-income index for 1 overall OECD and 38 member-countries.

Notes

Approximately 25% of variations in global house price synchronicity are explained by fundamental factors such as business cycle, bank integration, and global liquidity. See R2 reported in Alter et al. (2018).

A number of articles have shown that housing markets are affected by various behavioral biases including herding and confirmation biases. See Singh et al. (2023).

Herding may be among the most basic human instincts. From a crow’s-eye view in the air, Yi (1934) portrays a herding behavior of individuals who keep running blindly along the street one after another, as if scared.

Overconfidence arises when: one overestimates his ability; one places himself into the better-than-average; one is too confident on the precision of one’s prediction (Moore and Healy, 2008).

This view is consistent with Shiller (2008), who emphasizes the role of psychological factors and herd behavior in volatile markets. Shiller contends that the most important single element in understanding the boom is the social contagion of boom thinking, mediated by the common observation of rapidly rising prices. He emphasizes the effects of social interactions in the real estate bubble.

Due to status quo bias, people are always sticky to change the currently-held belief or actions. This is why confirmation is required to make them change in belief or action. People, who are obstinate in nature, always wish to get confirmation from influential leaders or a ‘pied-piper’ before taking actions. They seek a confirmatory signal from the leader’s action that is consistent with their current thoughts or observations they cannot explain why. Once confirmed, they are excited and tend to be more confident and overreact on signals. This is why overconfident people display herding behavior.

The ec model describes concisely how the market restores the deviation from the long-run equilibrium level. Under transaction cost, the model is used to classify under- or over-priced regimes (Hansen and Seo, 2002).

Based on the positive sign of herding coefficient, Pollock et al. (2024) claim that adverse herding is prevalent in the US housing markets. Borrowing the notion of reverse herding, I also observe the behavior in DuA1, DuA2, and DdA1 from my study. The first case occurs when the domestic price increase is confirmed by the US underpriced regime, while the other cases are when the domestic price change is not confirmed by the US price regimes.

Ferreruela and Mallor (2021) check the robustness of herding against the GFC and the Covid-19 periods.

The Chow test statistic: F= {(sums of squared residuals from whole sample - sums of squared residuals from reduced sample)/(the number of hold-back observations)}/{(sums of squared residuals from whole sample divided by the number of degrees of freedom)}. The number of hold-back sample is 66 for the Covid-19 pandemic and 5 for the GFC.

In order to check the robustness, I analyzed cross herding behavior based on CSADd for a particular battery of countries. Using the monthly real housing market data of the US and Korea, I find that domestic herding in Korea is more significantly influenced by the US PTR regimes than its own PTR regimes. Herding in Korea is significant when house price rise in Korea is matched with the lower US PTR regime. The result is also consistent with the view that cross herding is coupled with confirmation bias. Details are available upon request.

Rolling sample regression may be used to update herding coefficients. A warning signal may be issued when the coefficients fall beyond two standard errors from expected value. In order to manage downside market risk (fear sentiment), the maximum tolerable level of herding may be set at the left-tail such that \(({\gamma }_{g,d2}+{\gamma }_{us,d2})\le -2{\hat{\sigma }}_{d},\) where \({\hat{\sigma }}_{d}\) denotes standard error of the sum of estimates of coefficients of downside herding. Similarly, in order to manage upside market risk (greed sentiment), the maximum tolerable level of upside herding can be chosen such that \(({\gamma }_{g,u1}+{\gamma }_{us,u1})\le -2{\hat{\sigma }}_{u}\).

According to Savills World Research (2016), China accounts for 21% of all commercial and residential value $145.5 trillion and the US does for the other 21% (source: Savills blog at www.savills.com).

References

Alter A, Jane D, Seneviratne D (2018) House price synchronicity, banking integration, and global financial conditions, IMF Working Pap WP/18/250

An X, Cordell L, Nichols JB (2020) Reputation, information, and herding in credit ratings: evidence from CMBS. J Real Estate Financ Econ 61:476–504

Andrews DWS (1993) Tests for parameter instability and structural change with unknown change point. Econometrica 61(4):821–856

Apergis N, Christou C, Miller S (2012) Convergence patterns in financial development: evidence from club convergence. Empir Econ 43:1011–1040

Babalos V, Balcilar M, Gupta R (2015) Herding behavior in real estate markets: novel evidence from a Markov-switching model. J Behav Exp Financ 8:40–43

Bao HXH, Li SH (2020) Investor overconfidence and trading activity in the Asia Pacific REIT markets. J Risk Financ Manag 13(10):232

Bayer P, Kyle M, Roberts JW (2021) Speculative fever: Investor contagion in the housing bubble. Am Econ Rev 111:609–651

Bekiros S, Jlassi M, Lucey B, Naoui K, Uddin GS (2017) Herding behavior, market sentiment and volatility: Will the bubble resume? Nor Am J Econ Financ 42:107–131

Bikhchandani S, Hirshleifer D, Welch I (1992) A theory of fads, fashion, custom, and cultural change as information cascade. J Political Econ 100:992–1026

Bikhchandani S, Hirshleifer D, Welch I (1998) Learning from the behavior of others: conformity, fads, and informational cascades. J Econ Perspec 12(3):151–170

Bikhchandani S, Sharma S (2000) Herd behavior in financial markets. IMF Staff Pap 47(3):279–310

Bikhchandani S, Hirshleifer D, Tamuz O, Welch I (2024) Information cascades and social learning. J Econ Lit 62(3):1040–1093

Cai H, Yao T, Zhang X (2024) Confirmation bias in analysts’ response to consensus forecasts. J Behav Financ 25(3):334–355

Campbell JY, Lo W, Mackinlay C (1997) The econometrics of financial market. Princeton, NJ

Campbell JY, Shiller RJ (1987) Cointegration and tests of present value models. J Political Econ 95(5):1062–1088

Chang EC, Cheng JW, Khorona A (2000) An examination of herd behavior in equity markets: an international perspective. J Bank Financ 24(10):1651–1679

Chen T (2022) A cross‐country study on informed herding. Int J Financ Econ 27(4):4336–4349

Chiang TC, Zheng D (2010) An empirical analysis of herd behavior in global stock markets. J Bank Financ 34(8):1911–1921

Chiang TC, Li J, Tan L, Nelling E (2013) Dynamic herding behavior in Pacific-Basin markets: evidence and implications. Multinatl Financ J 17(3/4):165–200

Christie WG, Huang RD (1995) Following the pied piper: do individual returns herd around the market? Financ Anal J 51(4):31–37

Cipriano M, Gruca S (2014) The power of priors: how confirmation bias impacts market prices. J Predict Mark 8(3):34–56

Claessens S, Kose MA, Terrones ME (2011) Financial cycles: what? how? when? IMF Work Pap 11/76. IMF, Washington DC

Compen B, Pitthan F, Schelfhout W, Witte KD (2022) How to elicit and cease herding behaviour? On the effectiveness of a warning message as a debiasing decision support system. Decis Sup Sys 152:113652

Daniel K, Hirshleifer D, Subrahmanyam A (1998) Investor psychology and security market under- and over-reactions. J Financ 5(6):1839–1886

Devenow A, Welch I (1996) Rational herding in financial economics. Eur Econ Rev 40(3-5):603–615

Eicholtz P, Yönder E (2015) CEO overconfidence, REIT investment activity and performance. Real Estate Econ 43(1):139–162

Einhorn HJ, Hogarth R (1978) Confidence in judgement: persistence in the illusion of validity. Psychol Rev 85(5):395–416

Engle RF, Granger CWJ (1987) Co-integration and error correction: representation, estimation, and testing. Econometrica 55:251–276

Eriksen MD, Fout HB, Palim M, Rosenblatt E (2020) Contract price confirmation bias: evidence from repeat appraisals. J Real Estate Financ Econ 60:77–98

Evans J (1989) Bias in human reasoning: cases and consequences. Erlbaum, NJ

Faia E, Fuster A, Pezone V, Zafar B (2024) Biases in information selection and processing: survey evidence from the pandemic. Rev Econ Stat 106(3):829–847

Ferreruela S, Kallinterakis V, Mallor T (2024) Cross-market herding: do ‘herds’ herd with each other? J Behav Financ 25(2):208–228

Ferreruela S, Mallor T (2021) Herding in the bad times: the 2008 and COVID-19 crises. Nor Am J Econ Financ 58:101531

Filip AM, Pochea MM (2023) Intentional and spurious herding behavior: a sentiment driven analysis. J Behav Exp Financ 38:100810

Freybote J, Seagraves PA (2017) Heterogeneous investor sentiment and institutional real estate investments. Real Estate Econ 45(1):154–176

Friesen GC, Weller PA, Dunham LM (2009) Price trends and patterns in technical analysis: a theoretical and empirical examination. J Bank Financ 33(6):1089–1100

Frijns B, Huynh T (2018) Herding in analysts’ recommendations: the role of media. J Bank Financ 91:1–18

Galariotis EC, Rong W, Spyrou SI (2015) Herding on fundamental information: a comparative study. J Bank Financ 50:589–598

Hansen BE, Seo B (2002) Testing for two-regime threshold cointegration in vector error-correction models. J Econ 110(2):293–318

Hayunga DK, Lung PP (2011) Explaining asset mispricing using the resale option and inflation illusion. Real Estate Econ 39(2):313–344

Hott C (2012) The influence of herding behaviour in housing markets. J Eur Real Estate Res 5(3):177–198

Hwang S, Cho Y, Shin J (2020) The impact of UK household overconfidence in public information on house prices. J Prop Res 7(4):360–389

Hwang S, Rubesam A, Salmon M (2021) Beta herding through overconfidence: a behavioral explanation of the low-beta anomaly. J Int Money Financ 111:102318

IMF (2018) Hose price synchronization: what role for financial factors? Glob Financ Stab Rep. IMF, Washington DC

Just D (2014) Introduction to Behavioral Economics. John Wiley & Sons, NJ

Lantushenko V, Nelling E (2017) Institutional property-type herding in real estate investment trusts. J Real Estate Financ Econ 54(4):459–481

Lee CC, Lee HY, Yeh WC, Yu Z (2022) The impacts of task complexity, overconfidence, confirmation bias, customer influence, and anchoring on variations in real estate valuations. Int J Strateg Prop Manag 26(2):141–155

Lin CY, Rahman H, Yung K (2010) Investor overconfidence in REIT stock trading. J Real Estate Portf Manag 16(1):39–57

Martin C, Schmitt N, Westerhoff F (2022) Housing markets, expectation formation and interest rates. Macroecon Dyn 26(2):491–532

Moore DA, Healy PJ (2008) The trouble with overconfidence. Psychol Rev 115(2):502–517

Ngene GM, Sohn DP, Hassan MK (2017) Time-varying and spatial herding behavior in the US housing market: evidence from direct housing prices. J Real Estate Financ Econ 54:482–514

Nickerson RS (1998) Confirmation bias: a ubiquitous phenomenon in many guises. Rev Gen Psychol 2:175–220

Park D, Ryu D (2021) A machine learning-based early warning system for the housing and stock markets. IEEE Access 9:85566–85572

Philippas N, Economou F, Babalos V, Kostakis A (2013) Herding behavior in REITs: novel tests and the role of financial crisis. Int Rev Financ Anal 29:166–174

Pollock M, Mori M, Wu Y (2024) Herding and reverse herding in US housing markets: new evidence from a metropolitan-level analysis. Reg Stud 58(11):2099–2114

Pouget S, Sauvaguat J, Villeneuve S (2017) A mind is a terrible thing to change: confirmatory bias in financial markets. Rev Financ Stud 30(6):2066–2109

Rabin M, Schrag JL (1999) First impressions matter: a model of confirmatory bias. Q J Econ 114:37–82

Ro SH, Gallimore P, Clements S, Fan GZ (2019) Herding behavior among residential developers. J Real Estate Financ Econ 59:272–294

Rubesam R, Raimundo GS (2022) Covid-19 and herding in global equity markets. J Behav Exp Financ 35:100672

Shefrin H (2018) Behavioral Corporate Finance. McGraw-Hill Education, NY

Shiller RJ (2000) Irrational Exuberance. Princeton, NJ

Shiller RJ (2008) The subprime solution: How today’s global financial crisis happened, and what to do about it. Princeton, NJ

Shiller RJ (2014) Speculative asset prices. Am Econ Rev 104(6):1486–1517

Singh A, Kumar S, Goel U, Johri A (2023) Behavioural biases in real estate investment: a literature review and future research agenda. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10:846

Sun X, Li T, Zhu H, Zhu J (2024) Market memory, advance reaction, and retail investor herding. Pac -Basin Financ J 8:102251

Thaler R, Sunstein CR (2008) Nudge. Yale University Press, NY

Tsai I-C (2013) The asymmetric effects of monetary policy on housing prices: a viewpoint of housing price rigidity. Econ Model 31:405–413

Vafaeimehr A, Schulmerich M, Paterlini S (2023) Top investment banks, confirmation bias, and the market pricing of forecast revisions. Int Rev Financ Anal 88:102574

Yi S (1934) Crow’s eye view. Chosun Central Daily, 24 July 1934. In: Choi DM(ed) Yi Sang: Selected Works (trans: Jung J). 2020. Wave Books, Seattle. 5-6

Yunus N (2015) Trends and convergence in global housing markets. J Int Financ Mark Inst Money 36:100–112

Zhou J, Anderson RI (2013) An empirical investigation of herding behavior in the U.S. REIT market. J Real Estate Financ Econ 47:83–108

Acknowledgements

This article was inspired by the first poem of the series titled “Crow’s Eye View” written by Yi Sang, a surrealist poet in the early 20th century. The author is grateful to Kyong Kyo Lee, a professor emeritus of poetry at Myongji College, for thought-provoking dialogs about Yi’s works. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by the author.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by the author.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

You, T. Confirmation bias and herding behavior across the housing markets. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 708 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05021-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record: